Tackling fraud in UK aid through multilateral organisations

Executive summary

The UK considers the multilateral system to be vital to its interests and to tackling global challenges such as climate change and global health crises. Historically, more than half of the UK’s official development assistance (ODA) budget is channelled through multilateral organisations, such as the United Nations and World Bank. Each organisation has its own mandate and governance arrangements, which are collectively negotiated and agreed upon by its members. Funding to multilateral organisations is typically subject to a single audit principle, where only one designated body can conduct audits. The single audit principle is designed to avoid the cost and burden of multiple donors conducting audits and evaluations of multilateral organisations but therefore also limits individual donors’ access to review the effectiveness of counter-fraud systems.

This rapid review looks at how the UK’s Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO) ensures the effective management of fraud risks in its core funding to multilateral organisations. It assesses the extent to which the UK identifies, assesses and monitors multilateral organisations’ fraud risk management frameworks to ensure they have systems, including processes, governance structures, resources and incentives, in place to manage fraud risks in the UK’s ODA expenditure. It examines how effective the UK is at working with multilateral organisations and other donors to strengthen fraud risk management in multilateral organisations. Finally, it considers how the UK captures, applies and shares its learning on fraud risk management internally and externally. This rapid review, which is not scored, builds on the Tackling fraud in UK aid review conducted by the Independent Commission for Aid Impact (ICAI) in 2021, which assessed how effectively UK government departments tackle fraud in UK aid, focusing on the UK’s bilateral aid expenditure.

Relevance: To what extent does the UK identify, assess and monitor multilateral organisations’ fraud risk management frameworks to ensure they have systems, including processes, governance structures, resources and incentives in place to manage fraud risks in the UK’s ODA expenditure?

FCDO has appropriate processes in place to identify, assess and monitor multilateral organisations’ fraud risk management frameworks. FCDO conducts Central Assurance Assessments (CAAs) approximately every three years, which are a key tool in identifying and assessing fraud and wider governance risks. Fraud and governance aspects of these CAAs are generally completed to a high standard.

The main weakness we identified is that fraud risk is managed on an organisation-by-organisation basis without oversight of risks across the whole multilateral portfolio. For example, there is no systematic quality assurance or peer review process for CAAs or monitoring plans within FCDO. This results in a fragmented approach to identifying and managing key fraud risks. A portfolio approach could better focus resources and effort on managing overall risk to FCDO and maximising the positive impact on multilateral governance.

FCDO does not assess and monitor the fraud risk management of ODA funding through the European Commission in the same way as with other multilateral organisations. Historically, this was because of the UK’s oversight and governance role within the European Union. Since the UK exited the EU in January 2020, as with all residual funding to the EU, the UK-EU Withdrawal Agreement governs the residual aid commitment. However, the European Commission was the largest recipient of UK ODA funding in 2020 and it is expected to remain one of the largest until at least 2027, and FCDO’s last assessment, in 2016, found Commission fraud risk management to be weak. FCDO guidance states that due diligence of external partners should be renewed every three years.

Effectiveness: How effective is the UK at working with multilateral organisations and other donors to strengthen fraud risk management in multilateral organisations?

Multilateral organisations see the UK as a leading voice in promoting good counter-fraud practices. The UK has worked collaboratively with multilateral organisations to help them meaningfully improve their systems, but multilateral organisations also see the UK as administratively burdensome. Since reducing its aid budget and contributions to some multilateral organisations, the UK has seen some pushback on its demands for access and information beyond formal agreements. FCDO’s devolved approach to fraud risk management means multilateral organisations are treated differently depending on the UK’s leverage and the multilateral’s openness to UK influence, rather than relative to their risks.

There are good examples of where the UK has successfully collaborated with like-minded donors to improve counter-fraud practices in multilaterals and, in the case of joint CAAs with Australia, for example, to reduce the burden of multiple assessments and increase sharing of due diligence information between donors. However, this kind of collaboration between donors on due diligence is rare, and we heard from multilateral organisations that counter-fraud and governance issues are becoming less of a priority for some leading donors.

FCDO’s EU development team no longer has bilateral meetings on audits, evaluations, or fraud and anti- corruption issues with its counterparts since the UK’s departure from the EU. This lack of engagement with the European Commission is concerning because it is one of the largest and most influential development actors and among the most closely aligned to the UK on counter-fraud issues.

Learning: How does the UK capture, apply and share its learning on fraud risk management internally and externally?

FCDO teams that manage multilateral organisations gain significant insights about the specific multilateral organisation they are working with through their day-to-day engagement and especially through secondments of staff to the organisations. Multilaterals, too, have learned from the expertise and intelligence provided by FCDO, which has led to significant improvements in their systems and processes. However, there is no coordination within FCDO of secondee learning which, combined with the lack of quality assurance and peer review processes across the multilateral portfolio, means potentially valuable lessons about how to best help and influence multilaterals to improve their counter-fraud systems, processes and practices are not being shared across Multilateral Teams or more widely across FCDO.

Recommendations

Recommendation 1:

FCDO should establish a risk-based portfolio approach to managing governance risks across funding to all multilateral organisations.

Recommendation 2:

FCDO should continue to build stronger coalitions with like-minded donors to maintain counter-fraud and good governance as a top priority for multilateral organisations.

Recommendation 3:

FCDO should renew and document its assessment of the European Commission’s ODA fraud risk management, in line with its processes for all multilateral organisations it funds.

Introduction

This rapid review looks at how the UK’s Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO) ensures the effective management of fraud risks in its core funding to multilateral organisations. As a rapid review, it intends to provide timely, evidence-based conclusions and recommendations but does not examine the evidence in sufficient depth to allow for scoring.

Multilateral organisations are formed between three or more nations to work on issues relevant to each of them. At the global level, these include the United Nations (UN), World Trade Organisation and World Bank. Multilateral organisations are primarily funded by their members. Each has its own mandate and governance, collectively negotiated and agreed upon by its members. Funding to multilateral organisations that address humanitarian and international development issues is official development assistance (ODA).

The UK government considers the multilateral system to be “vital to the UK and global interests” and has committed to seeking multilateral solutions to global challenges such as climate change and global health crises. In 2016, following its decision to leave the EU, the UK government stated that working towards a “truly transparent, efficient” multilateral system was a key part of its ongoing contribution to multilateralism. The UK government reiterated its “deep commitment” to multilateralism, to strengthening multilateral organisations and to playing a leading international role in multilateral governance in its 2021 Integrated review of security, defence, development and foreign policy.

More than half of the UK’s ODA is channelled through multilateral organisations. Most of this funding is channelled through core contributions, which means the UK has not specified how the multilateral organisation should use the ODA (see Box 1). Such funding is typically subject to a single audit principle, where only one designated body can conduct audits. With the UN, for example, the United Nations Board of Auditors is the designated external auditor for all UN entities, funds and programmes. The single audit principle is designed to avoid the cost and burden of multiple donors conducting audits and evaluations of multilateral organisations but this limits the UK’s access to review the effectiveness of counter-fraud systems.

This rapid review focuses on how FCDO manages fraud risk in its core contributions to multilateral organisations, which are subject to the single audit principle. It looks at how effectively FCDO uses mechanisms and relationships to tackle fraud, rather than seeking to access or assess multilateral organisations’ own systems and data. The review builds upon the 2021 Independent Commission for Aid Impact (ICAI) rapid review on Tackling fraud in UK aid which assessed the effectiveness of counter-fraud measures across UK government departments that spend ODA, focused on bilateral funding.

The review covers the period since the 2016 Multilateral development review, conducted by the former Department for International Development (DFID), which was merged with the Foreign and Commonwealth Office (FCO) in 2021 to form FCDO. The Multilateral development review assessed the strategic alignment and organisational strength of each multilateral organisation that received more than £1 million of UK ODA and informed how DFID, and subsequently FCDO, engages with multilateral organisations, including on fraud risk management and wider fiduciary risk and governance issues. Former DFID and FCO systems, structures and strategies were being integrated during this review. We did not set out to comprehensively assess the impact of this integration but sought to assess the effect of changes on priorities and relationships in relation to fraud risk management, and to identify future opportunities for FCDO in this area.

Box 1: UK ODA by delivery channel

“There are two main delivery channels for ODA: bilateral and multilateral.

Bilateral ODA is earmarked spend, ie the donor has specified how the ODA is spent – this is usually ODA going to specific countries or programmes. There are two types of bilateral ODA:

- Bilateral through multilateral: this is earmarked ODA spent through multilateral organisations. For example, to support the World Food Programme’s (WFP) emergency operations in Yemen.

- Other bilateral: this is earmarked ODA spent directly by governments or through delivery partners such as non-governmental and civil society organisations (NGOs, CSOs), research institutions and universities. For example, delivering family planning services across Malawi through an NGO.

Core multilateral ODA is unearmarked funding from national governments to multilateral organisations, which is pooled with other donors’ funding and dispersed as part of the core budget of the multilateral organisation. For example, the UK’s contribution to the World Bank International Development Association.”

This review focuses on core multilateral ODA, although it considers bilateral through multilateral funding where this relates to overall relationships and fraud risk management.

Table 1: Our review questions

| Review criteria |

|---|

| 1. Relevance: To what extent does the UK identify, assess and monitor multilateral organisations’ fraud risk management frameworks to ensure they have systems including processes, governance structures, resources and incentives in place to manage fraud risks in the UK’s official development assistance expenditure? |

| 2. Effectiveness: How effective is the UK at working with multilateral organisations and other donors to strengthen fraud risk management in multilateral organisations? |

| 3. Learning: How does the UK capture, apply and share its learning on fraud risk management internally and externally? |

Methodology

Our methodology for this rapid review comprised of the following components:

Annotated bibliography: A brief update to the annotated bibliography for the 2021 Tackling fraud in UK aid, including summaries of literature relating to fraud risk management in multilateral organisations.

Document review: Review of documentation relating to the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office’s (FCDO) management and monitoring of multilateral organisations focusing on unearmarked, core funding. This included due diligence assessment documentation, tools and guidance used by FCDO staff to help with decision-making. It also included documentation relating to monitoring and processes followed for suspected fraud.

Case studies: A more detailed look at six multilateral organisations, including due diligence, assessments and analysis held by FCDO. Our selection of multilateral organisations for case studies considered the strategic importance of the organisation to the UK according to FCDO, the level of funding it receives from the UK, and findings of the Multilateral development review and subsequent assessments. We also aimed to cover different types of multilateral organisation. Using these considerations, we selected the following multilateral organisations to be the subject of more detailed case studies:

- European Commission

- Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance

- United Nations Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR)

- United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA)

- World Bank

- World Health Organisation (WHO).

We looked at how FCDO sets out to address weaknesses and the effectiveness of its efforts. We analysed reported fraud data and reviewed key FCDO documentation relating to each of these six organisations. This focused on core funding but considered non-core, earmarked funding in relation to FCDO’s overall ability to manage fraud risks with multilateral organisations.

Stakeholder interviews: Interviews with FCDO’s Multilateral Effectiveness Team and stakeholders with relationship management and counter-fraud responsibilities in FCDO, multilateral organisations and other key donors to understand the use of tools, policies and processes in practice; how the UK works within the global community; and different perspectives throughout the delivery chain. To encourage openness in our discussions, and because we did not set out to assess multilateral organisations themselves, we have maintained the anonymity of respondents and organisations except where this was required as context for our findings and recommendations relating to UK ODA allocated to the European Commission.

The 2006 Fraud Act describes fraud as making a false representation, failing to disclose relevant information, or the abuse of position to make financial gain or misappropriate assets. While technically fraud requires intentional deceit or abuse of power, for this review, we took a broad interpretation of fraud, including bribery, theft and other corrupt acts involving UK aid. This is consistent with our approach in the 2021 Tackling fraud in UK aid review.

Box 2: Limitations to the methodology

- This review does not seek to follow up on the recommendations in previous ICAI reviews.

- This review is not an audit, nor is it intended as an update to the former DFID’s 2016 Multilateral development review.

- This review does not attempt to assess the multilateral organisations themselves. Our objective is to review how effectively the UK assesses, monitors and influences multilateral organisations to manage fraud risks.

- While we examined how FCDO assesses and contributes to the effectiveness of multilateral organisations’ counter-fraud measures, we did not verify the application of those measures in practice.

- This review did not seek to identify new fraud cases or quantify fraud levels in UK aid or multilateral organisations. No new cases of fraud were brought to our attention during this review.

- We originally planned to visit up to two multilateral hubs in Europe to conduct in-person interviews. This was not practical due to work-from-home policies in multilateral organisations and travel restrictions caused by the COVID-19 pandemic. We therefore conducted our work remotely.

Background

Fraud is a hidden crime. It is a deliberate and illegal act which results in funds or assets being diverted from their intended purpose. While finding fraud can be difficult, three key factors can affect the likelihood of fraud being committed, known as the ‘fraud triangle’:

- opportunity, such as weak controls or too much trust

- motivation, such as for financial gain or pressure to meet targets

- rationalisation, such as feeling undervalued or that “everyone else is doing it”.

Global losses due to fraud are estimated to be between 3% and 10% of gross domestic product (GDP). The Independent Commission for Aid Impact’s (ICAI) 2021 review on Tackling fraud in UK aid reported that most UK government departments, including the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office’s (FCDO) predecessor departments, the Department for International Development (DFID) and the Foreign and Commonwealth Office (FCO), identify less than 0.1% of expenditure lost to fraud. The review also noted similar, low levels of detected fraud reported by other major official development assistance (ODA) donors such as the US, for example, and by multilateral organisations such as United Nations (UN) agencies.

ICAI’s 2021 review recognised the challenges of uncovering fraud in UK aid and made recommendations for how ODA-spending government departments can reduce barriers for reporting fraud concerns, and improve data collection and intelligence sharing across departments to more effectively manage fraud risks (see Box 3). It focused on bilateral funding through grants and contracts to non-governmental organisations and companies, where government departments have significant access to documentation, systems and data to conduct due diligence and investigate concerns.

Box 3: Further context on ICAI’s previous work focusing on counter-fraud

This report builds on ICAI’s previous work relating to counter-fraud including its 2011 review DFID’s approach to anti-corruption; its 2015 review How DFID works with multilateral agencies to achieve impact; the 2016 review DFID’s approach to managing fiduciary risk in conflict-affected environments; and the 2021 rapid review Tackling fraud in UK aid. The latter two particularly highlighted the importance of robust systems and processes to effectively manage the risk of fraud and corruption in the aid programme.

Following our recommendations in the 2021 rapid review, FCDO partially agreed to our recommendation for “a centralised ODA counter-fraud function to ensure good practice and consistency of the ODA counter- fraud response and share intelligence across all ODA spend”. FCDO decided against establishing a central ODA counter-fraud function within the government’s Counter Fraud Centre of Expertise hosted in the Cabinet Office. However, it agreed that FCDO would “lead on creating an ODA counter-fraud forum” and strengthening fraud governance “to facilitate the sharing of good practice and to increase consistency of approach for counter-fraud activity across ODA-spending departments.”

FCDO agreed with our recommendations t o review and streamline reporting systems and procedures and strengthen training for delivery partners, to increase independent oversight of ODA outsourcing and to invest in collecting and analysing more data and trends. We will assess how well the government has responded to these recommendations during our annual follow-up process.

Funding through multilateral organisations is different. Multilateral organisations receive funding from multiple governments and sometimes also from non-governmental donors, such as private foundations or the public. To avoid the cost and burden of each donor requiring audits and evaluations of multilateral organisations, such processes are typically centralised with limited access permitted to individual donors to conduct their own assessments under the single audit principle. While donors can access audit reports and other information published by multilateral organisations, this principle prevents donors from performing their own checks. There are exceptions; for example, the European Commission has negotiated the right to undertake verifications with the UN. UN agencies must give Commission representatives access to aid delivery locations and UN and partner offices, and provide sufficient evidence to “ensure transparency and accuracy in the accounts and to guard against the misuse of funds and fraud.” The UK does not have this right but seeks additional information to help ensure effective spend of UK aid by multilateral organisations and to work towards its objective of strengthening multilateral governance.

Although multilateral organisations’ centrally-managed audits and evaluations can provide some assurance that the UK’s core contributions are properly managed, these are determined according to the organisations’ own consideration of what is material and therefore may not be aligned to the UK’s consideration of what is material. In addition, the UK has identified weaknesses in several multilateral organisations’ accountability systems, which warrant efforts to gain additional assurances that UK funds are being properly spent. As we discuss later in the report, the UK has accessed information to help it manage and address fraud risks in certain cases.

The UK’s Multilateral development review and fraud risk

In 2016, DFID assessed the strategic alignment with UK priorities and organisational strengths of 38 multilateral organisations in its Multilateral development review. Unlike the 2011 Multilateral aid review, the 2016 review included new questions on fraud, risk and transparency, including: “does the agency promote risk management and assurance in its corporate governance”; “does the agency prevent, detect and take sanctions against fraud and corruption”; and “is the agency accountable to partner governments or clients and beneficiaries through all of its work”.

Based on information provided by the multilateral organisations, the Multilateral development review concluded that “all agencies have systems in place to detect and combat fraud, with multilateral development banks having some of the best developed.” It notes, however, that often “there was not enough evidence of how well systems function in practice.”

The Multilateral development review informs how the UK engages with multilateral organisations to strengthen their performance and accountability and set expectations about the UK’s “zero-tolerance approach to fraud and corruption”. The review states that “[a]cross all multilaterals, the UK will push for improved transparency, better value for money and greater accountability […] setting out more requirements for multilateral agencies, including new openness about management and administration budgets”. Furthermore, it stated that the UK “will work closely with partners who share our vision of a multilateral system that is even faster, more effective and more efficient”.

UK aid through multilateral organisations

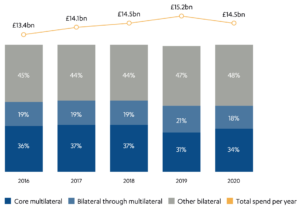

More than half of UK ODA is channelled through multilateral organisations. As explained in Box 1, FCDO categorises ODA funding to multilateral organisations as either “bilateral through multilaterals” or “core multilateral” ODA. Figure 1 shows UK ODA to multilateral organisations by delivery channel. Table 2 shows the top 20 multilateral recipients of UK ODA in 2020, by spend.

Figure 1: Total UK ODA by main delivery channel from 2016 to 2020

Source: Statistics on international development: Final UK aid spend 2020, FCDO, September 2021, p. 15, link

Table 2: Top 20 multilateral recipients of UK core funding in 2020

| Rank | Multilateral | Amount of UK ODA | Proportion of total ODA spent through multilaterals |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | European Commission, share of spend from UK official development assistance (ODA) | £1,149m | 23.2% |

| 2 | International Development Association, World Bank | £920m | 18.6% |

| 3 | Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria | £476m | 9.6% |

| 4 | Green Climate Fund | £450m | 9.1% |

| 5 | European Development Fund, European Commission | £368m | 7.4% |

| 6 | Poverty Reduction and Growth Trust, International Monetary Fund (IMF) | £255m | 5.2% |

| 7 | Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance | £200m | 4% |

| 8 | African Development Fund | £176m | 3.6% |

| 9 | International Finance Facility for Immunisation | £129m | 2.6% |

| 10 | Central Emergency Response Fund (CERF) | £66m | 1.3% |

| 11 | United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) | £55m | 1.1% |

| 12 | United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) | £48m | 1% |

| 13 | United Nations | £48m | 1% |

| 14 | International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (IBRD) | £45m | 0.9% |

| 15 | United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East (UNWRA) | £43m | 0.9% |

| 16 | World Food Programme (WFP | £40m | 0.8% |

| 17 | Special Climate Change Fund, Global Environment Facility (GEF) | £38m | 0.8% |

| 18 | United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) | £35m | 0.7% |

| 19 | Department of Peace Operations (DPO), United Nations | £35m | 0.7% |

| 20 | International Drug Purchase Facility (UNITAID) | £33m | 0.7% |

The UK’s ODA spending target is linked to gross national income (GNI). A reduction in the UK’s GNI due to COVID-19 impacted the 2020 ODA spend compared to forecasts, resulting in a £1.3 billion in-year reduction in aid spending. As noted in ICAI’s review of the Management of the 0.7% ODA spending target in 2020, the 2020 aid reductions affected bilateral spending more severely than multilateral spending. This was in part due to mechanisms that enable the timing of multilateral payments to be adjusted to meet spending targets within the year without practical impact.

In 2021, the UK government reduced the aid spending target from 0.7% to 0.5% of GNI. This reduced the UK’s aid spend by 25%, from £14.5 billion in 202040 to £10.9 billion in 2021. In contrast to the 2020 volatility in GNI, the reduction from 0.7% to 0.5% in GNI will have longer-term implications that therefore cannot be managed by adjusting the timing of payments. FCDO is yet to publish details of its 2021 expenditure, including the impact of funding reductions on individual multilateral organisations.

Multilateral Effectiveness Team and the three lines of fraud defence

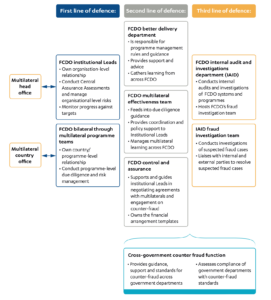

As outlined in ICAI’s April 2021 review on Tackling fraud in UK aid, FCDO operates three lines of defence against fraud, which also applies to core multilateral funding (see Figure 2).

The first line of defence is responsible for day-to-day risk management of each multilateral organisation including due diligence and ongoing monitoring. Regarding core funding to multilateral organisations, a dedicated Institutional Lead manages the relationship with each organisation and is responsible for the first line of defence, often supported by a dedicated Multilateral Team as with our case study organisations. Programme teams in country offices, which manage some bilateral through multilateral funding and have local relationships with multilateral organisations, are also an important source of intelligence for the Institutional Lead and form part of the first line of defence.

The second line of defence comprises the Better Delivery Department, which provides rules, guidance and support to the first line across the whole of FCDO, and Control and Assurance, which provides support and guidance in negotiating agreements with multilaterals, and engagement on counter-fraud. Unique to multilateral organisations, FCDO also has a separate Multilateral Effectiveness Team to support the second line of defence, responsible for overarching coordination, policy, data and guidance on multilateral ODA. The Multilateral Effectiveness Team provides programme and policy support across all Multilateral Teams but does not have any sign-off or quality assurance role nor does it cover fraud risk or governance issues. Figure 2 shows its role.

The third line of defence is FCDO’s Internal Audit and Investigations Directorate including its Fraud Investigation Team, which conducts investigations of suspected fraud. Fraud detected or suspected by the first or second line of defence should be reported to the counter-fraud section to investigate. The cross-government Counter Fraud Function in the Cabinet Office provides additional second- and third-line support. It provides support and guidance to build counter fraud capacity in government departments. It also sets standards for all government departments to follow and assesses their compliance with these standards annually.

Figure 2: The three lines of fraud defence in multilateral funding

Programme management rules and guidance

Prior to June 2021, the key documents setting out FCDO’s fraud risk management (which also applies to Multilateral Teams) were the Smart Rules for legacy DFID programmes, focused on ODA, and the Policy Portfolio Framework, for legacy FCO. The Smart Rules set out key risk management responsibilities and designated Senior Responsible Officers (SROs) as having responsibility for the design, delivery, closure and archiving of programmes, including the first line of defence against fraud. In June 2021, FCDO’s Programme Operating Framework (PrOF) replaced the Smart Rules and the Policy Portfolio Framework. PrOF follows the same three lines of defence approach but designates Programme Responsible Officers (PROs) as the first line of defence, since they handle the day-to-day delivery of programmes including the effective management of risks.

As in the Smart Rules, PrOF advises that “the management of fraud and fiduciary risk is a collective responsibility of all FCDO officials and partners. Everyone is responsible for the sound management of public resources, whether working on policy, programme delivery or other resources”. The SRO role, meanwhile, is accountable for a programme or project meeting its strategic objectives. The SRO and PRO are roles which can be attributed to the same person. In the application of both the Smart Rules and PrOF within Multilateral Teams, Institutional Leads have overall risk management responsibility for their multilateral organisations. Due to the timing of this review, most documentation we reviewed was prepared before PrOF was introduced.

Findings

Relevance: To what extent does the UK identify, assess and monitor multilateral organisations’ fraud risk management frameworks to ensure they have systems, including processes, governance structures, resources and incentives in place to manage fraud risks in the UK’s ODA expenditure?

FCDO has appropriate processes in place to identify, assess and monitor multilateral organisations’ fraud risk management frameworks

Rather than prescriptive standards, the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO) bases its approach to official development assistance (ODA) risk management, including fraud risk management, on principles and a small set of mandatory rules supported by non-mandatory guidance. FCDO has adopted the principles-based approach in the former Department for International Development’s (DFID) Smart Rules in its Programme Operating Framework (PrOF) and accompanying guidance, originally developed by DFID’s Better Delivery Department to support first line roles. This approach, used across all FCDO ODA programming, is appropriate for multilateral organisations that vary significantly in terms of their mandates, level of transparency, scale, risk profiles, complexity and governance structures, and where FCDO’s contribution to, influence on and role in the governance of multilateral organisations also vary significantly. A principles-based approach enables staff in the first line of defence to tailor their approaches to the multilateral organisation and FCDO’s relationship with it.

Institutional Leads identify, assess and manage risks for each multilateral organisation (see Figure 2 above). FCDO’s guidance on due diligence – which is of particular importance for identifying, assessing and planning how to manage and monitor fraud risks with partner organisations – outlines five pillars to be considered when assessing risk in delivery partners:

- governance and internal controls – including culture, whistleblowing and counter-fraud and aid diversion

- ability to deliver – including staff competencies and programme risk management

- financial stability – including procurement, financial risk management and segregation of duties

- downstream delivery – including downstream due diligence and counter-aid diversion

- safeguarding – including policies, grievance procedures and governance.

FCDO due diligence guidance includes an additional annex with brief guidance and a list of indicative questions to be considered by Institutional Leads when conducting due diligence on multilateral organisations. The multilateral annex questions, like all FCDO guidance, are not mandatory; it is up to Institutional Leads to determine the scope and methodology of due diligence on a case-by-case basis. Similarly, there are no specified red flags in the guidance where FCDO does not proceed with funding; this decision belongs to the Institutional Lead.

Where FCDO provides core funding to multilateral organisations, it undertakes a type of due diligence called a Central Assurance Assessment (CAA), as explained in the guidance annex (see Box 4). The guidance annex notes that “[c]ore contributions are made directly to multilaterals to deliver objectives in line with their core mandate”. It is unearmarked and “FCDO does not have direct control over how and where funds are spent”. FCDO can, however, use its “influence in multilateral boards where donors collectively agreed the main objectives on which core funding will be spent” to help to ensure that funds are “implemented in accordance with the governance, operational and oversight arrangements of the multilaterals”.

The annex states that “CAAs are repeated every three years” and that they “require significant staff resources both in terms of time and appropriate skill set”. It also states that CAAs should be conducted “in close cooperation with the multilateral partner”.

Box 4: Excerpt from FCDO’s guidance on Central Assurance Assessments

“Core funding is managed by an Institutional Lead who is responsible for the FCDO’s overarching relationship with that multilateral and manages the programme in accordance with FCDO’s programme framework and rules. When FCDO provides core funding to a multilateral organisation, due diligence of that organisation is undertaken by the Institutional Lead through a Central Assurance Assessment (CAA). Broadly speaking, a CAA is a periodic assessment of the capabilities and risks of working through a multilateral partner, to ensure they are fit and proper to work with HMG [Her Majesty’s Government].

“The aim of a CAA is to provide an overall judgement of the risks related to working with that organisation, underpinned by assurances that it has an appropriate governance structure, that central policies, controls and processes of sufficient quality are in place, that these are well communicated across the organisation and its delivery partners and are operating effectively in practice, that it can effectively monitor, evaluate and improve its processes and delivery, and that suspicions or allegations of fraud, bribery, corruption or SEAH [sexual exploitation and harassment] are identified, communicated and dealt with appropriately.”

There is no Central Assurance Assessment for the European Commission

The European Commission is the executive branch of the EU and includes the EU’s humanitarian and development aid bodies through which most UK ODA managed by the EU is channelled. FCDO’s EU development team informed us that the UK’s core ODA contributions to the EU were exempt from ODA due diligence processes, including CAAs, because the UK was a member state and therefore legally part of the oversight and governance of the EU’s budget. This included a UK governance and oversight role in programme committees and the European Court of Audits, the EU Anti-Fraud Office (OLAF), the EU Council and the EU Parliament. The European Commission was, however, included in DFID’s 2016 Multilateral development review, which assessed the fraud risk management of both the Commission’s humanitarian and development aid bodies as ‘weak’. This high-level summary of the EU in the Multilateral development review does not identify the reasons for this score or measures to address weaknesses. FCDO’s EU Institutional Lead considers the Multilateral development review is still a fair reflection of the Commission’s monitoring, evaluations, audit, fraud and anti-corruption structures and processes.

Following the UK’s exit from the EU in January 2020, the UK-EU Withdrawal Agreement governs the UK’s programme relationship with the Commission. The UK no longer has its former oversight and governance roles, although it remains an observer of the European Development Fund – with access to the same financial and operational reporting as EU member states – and as a full member of the EU Trust Fund for Africa and the Facility for Refugees in Turkey. The UK previously regularly seconded staff to the Commission, providing further insight and understanding of systems; access it no longer has. For most UK ODA channelled through the Commission, therefore, the UK now relies on publicly available documents produced by the EU, such as annual reports from the Court of Auditors and OLAF. These are managed by a designated UK Desk within the Commission, responsible for bilateral relationships on development aid, in the same way as the Commission engages with other non-EU members such as the US and Canada.

Treasury provides annual reports on the UK’s contribution to the EU budget. This includes references to financial management and fraud, including reviews of:

- The European Court of Auditors’ annual report, that holds the Commission and member states to account for their management of the EU budget.

- The Commission’s annual ‘Fight Against Fraud’ report, which details the actions taken by the Commission and member states to counter fraud affecting EU funds.

- The European Anti-Fraud Office (OLAF) annual report, which summaries the activities of the Office during the preceding year.

Treasury’s reporting includes the UK’s ODA contribution to the EU in its scope but at a much higher level than other Multilateral Teams which assess fraud risk based on their team’s budget.

FCDO informed us that, through the EU development team and the UK mission in Brussels, it monitors ODA-related information published by the Commission about changes in both policy and programme delivery, including reports on counter-fraud and governance. The EU development team stated it has not identified any significant changes since the UK’s exit from the EU. FCDO currently has no plans to put in place a CAA for the Commission, despite it expected to be among the largest multilateral recipients

of UK aid until at least 2027, as the UK-EU Withdrawal Agreement governs existing funding.56 The EU development team noted that, should new ODA funding be made to the Commission, the usual FCDO due diligence and fiduciary risk management procedures would apply. Similarly, FCDO informed us that if it becomes aware of major changes in the EU’s fraud management structures and processes, this would be assessed from a due diligence and fiduciary risk perspective, and its risk register updated accordingly.

Central Assurance Assessments are generally completed to a good standard but there is no systematic quality assurance process

Regarding fraud and governance, CAAs for our case study organisations were completed to a good standard in line with the former DFID due diligence guidance at the time, although there was some variation in quality. For example, some assessments were more strategic, focusing on the most important issues including a prioritised list of areas for follow up. Others provided comprehensive coverage of the issues but did not prioritise them or provide clear follow-up actions. Table 3 shows an overview of the CAAs for the five case study multilateral organisations where they had been undertaken. In the five CAAs for our case study organisations, ratings were given against the pillars set out in the due diligence guidance. All these CAAs considered fraud risk and other relevant risk management and governance issues related to fraud risk management. In line with the guidance, CAAs included input from staff in the relevant multilateral organisation.

Although the reports were documented as being written by FCDO staff, CAAs are fact checked by, and final versions shared with, multilateral organisations. This means they are written knowing that they will be shared with the organisation. This enables Institutional Leads to use the CAAs as a tool to work towards change that can be tailored to each multilateral, but makes them less comparable with each other and more difficult to aggregate to gain a view across the whole multilateral portfolio.

Our lighter review of CAAs for a wider range of multilateral organisations showed that fraud and broader governance were always considered, although in varying depth. The names or roles of those completing the CAA are not always provided but, where given, there is wide variation in the seniority of staff, ranging from junior staff to the head of Internal Audit. More senior staff approved those CAAs completed by junior staff.

For the case study organisations, the composition of CAA teams also varied. Some were documented as being conducted by staff within the Multilateral Team and others drew on expertise from elsewhere in the department. FCDO informed us it expects all CAAs to include input from expertise from outside the Multilateral Team, such as from commercial or finance teams, even if this is not documented, albeit to varying degrees. From the documentation reviewed, the level of governance or counter-fraud expertise involved in the CAAs is unclear, although some teams included financial expertise such as from DFID’s Internal Audit Department. One of the CAAs had been quality assured by another Institutional Lead. We consider this to be good practice, but it is not a stated FCDO requirement and there is no standard quality assurance or process for peer review by another Institutional Lead in place for CAAs, or other aspects of multilateral risk management, such as monitoring plans.

The due diligence guidance provides some explanation of what sort of evidence is expected or considered good practice, albeit there are no set rules. There is an appreciation of different levels of assurance that can be obtained, ranging from confirming the existence of policies to testing their embeddedness, but the five CAAs that we reviewed focused more on system design than effectiveness. While FCDO does not have a right to assess the effectiveness of fraud systems, it could seek evidence of how the multilateral organisation determines this. We did not see any good examples of this in our sample.

Table 3: Overview of Central Assurance Assessments for five case study multilateral organisations

| Organisation Case Study 1 | Organisation Case Study | Organisation Case Study 3 | Organisation Case Study 4 | Organisation Case Study 5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Review date | September 2020 | January 2020 | November 2017 | May 2020 | November 2018 |

| Overall rating | Severe | Moderate | Major | Major | Minor |

| Governance and internal control | Severe (average)* | Moderate | Major | Major | Moderate (average)* |

| Ability to deliver | Major(average)* | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate (average)* |

| Financial stability | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate | Minor (average)* |

| Downstream partners | Major (average)* | Major | Moderate | Major | Minor (average)* |

| Completed by | Two programme managers and deputy head internal audit | Internal Audit Department; quality assured by the Institutional Lead for another multilateral | Head of corporate assurance | Head of strategic and thematic assurance and an internal auditor | Adviser in the Multilateral Team |

| FCDO definition for due diligence of partner, including multilateral organisations: Minor: Findings that do not pose unacceptable negative fiduciary and/or reputational risk to DFID/FCDO but which the Partner may wish to consider. Moderate: Findings that do not pose unacceptable negative fiduciary and/or reputational risk to DFID/FCDO but which would be advisable for the Partner to address to improve their systems, processes or procedures. Major: Weaknesses that pose unacceptable negative fiduciary and/or reputational risk to DFID/FCDO but where mitigating actions could be put in place to suitably reduce the risk to acceptable levels. Severe: Weaknesses that pose unacceptable negative fiduciary and/or reputational risk to DFID/FCDO and where necessary mitigating actions are either not possible or highly challenging for the Partner to implement. | |||||

*Where CAA authors chose to rate individual findings under each pillar, therefore producing multiple ratings, we have calculated the average rating overall.

Two out of five of the CAAs were older than three years. Work to update these two CAAs was ongoing but, although the three-year period is guidance and not a rule, we would expect to see more timely updated assessments, especially where major concerns have been previously identified and given the significant changes in risks and risk management capability due to COVID-19. With responsibility devolved to Institutional Teams, it is up to them to decide when to update CAAs.

Our review of CAAs found it is not uncommon for multilateral organisations to receive a ‘major’ or higher rating under one or more of the pillars, or to receive this as an overall rating. This is the second highest risk level in the due diligence guidance and signifies that FCDO has identified weaknesses that pose an unacceptable negative fiduciary or reputational risk to them. However, it is not clear from the documentation what action it took to address concerns. Institutional Leads told us that funding is not conditional on these ratings. Instead, they appear to be used to communicate FCDO’s concerns with the multilateral organisation and as a leverage for action. We noted that FCDO made stronger recommendations where the UK had confidence that changes could be achieved, and made lighter recommendations where this was considered more challenging, although, as our sample was small, this may not always be the case. Combined with the lack of peer review and fact checking of CAAs by multilateral organisations, there is a potential risk that findings and recommendations could be too heavily influenced by the relationship with the multilateral organisation rather than based purely on the risk posed to UK aid.

Monitoring of fraud risks is matched to risks identified in CAAs but relies on reporting by multilaterals

We found CAAs provide a useful basis for subsequent monitoring, which is also the responsibility of Institutional Teams. FCDO’s monitoring of fraud risks, however, is heavily reliant on self-reporting by the multilateral organisation. This includes public reports, internal reports available to FCDO as a donor or where it has a governance role, and sometimes bespoke reporting negotiated by FCDO. In most cases, this approach is appropriate and related to risks. In one case study, however, FCDO had previously set targets for the Multilateral Team to report decreasing levels of fraud. This is problematic as fraud is a hidden crime and finding and reporting it are key to addressing it. The Multilateral Team subsequently realised that such an approach was inappropriate and no longer have this target, but it was in place for three years. Had a counter-fraud specialist reviewed the monitoring plan, it is likely this issue would have been avoided.

The Multilateral Effectiveness Team does not have an oversight role and there is no overarching view of fraud risks across all multilateral organisations

The Multilateral Effectiveness Team provides input into FCDO due diligence guidance managed by the Better Delivery Department as it relates to multilateral organisations. The team does not have any oversight, quality assurance or coordination role in relation to individual due diligence assessments or risk management plans (managed by Institutional Leads) or of fraud cases (managed by Internal Audit).

The Multilateral Effectiveness Team is part of FCDO’s Delivery Directorate and comprises five full-time equivalent (FTE) staff: a team leader, three FTE policy advisors and a policy officer. During our review, the team was reduced from 5.6 to 5 FTE and only two FTE policy advisors were in post. Of the five FTE roles in the Multilateral Effectiveness Team, none have fraud or governance expertise, and none are members of the Cabinet Office-led cross-government Counter Fraud Function, discussed in ICAI’s 2021 review. As it stands, the team’s role does not include responsibility for fraud risk management. Instead, in the examples we saw where Multilateral Teams required counter-fraud or governance expertise, they relied on experience within their own teams or drew on expertise from Internal Audit.

We saw evidence that Multilateral Teams review relevant reports from external sources as part of their due diligence and risk monitoring, in particular the Multilateral Organisation Performance Assessment Network (MOPAN) – a group of 19 national donors including the UK that conducts joint assessments of multilateral organisations on behalf of its members.

FCDO’s Fraud Investigation Team had managed suspected fraud cases

FCDO’s Fraud Investigation Team deals with all reported suspected fraud cases including those relating to multilateral organisations. Since 2016, 23 suspected fraud cases related to our case studies were reported to FCDO’s Fraud Investigation Team. The team had tracked and closed each case according to their processes. In 22 cases, FCDO/DFID relied primarily on the multilateral organisation’s investigation and noted that measures had been put in place for identified weaknesses. In the remaining case, FCDO could confirm that it had lost no UK funds using its own records and closed the case. In seven cases, FCDO identified a total of £532,230 worth of losses relating to UK aid funding. FCDO recovered the losses, but in common with the findings in ICAI’s 2021 review, they were typically reimbursed by the multilateral organisation and not always recovered from the fraudster, meaning there is still a loss in the aid system overall.

As noted in ICAI’s 2021 review, the Fraud Investigation Team is primarily reactive. While the Fraud Investigation Team will respond to requests for specific help, it gives priority to its core reactive mandate of case management and investigations. The team informed us that, at present, it has insufficient capacity to support proactive counter-fraud work across multilateral organisations but that it would consider future requests.

Conclusion on relevance

FCDO has appropriate processes in place to identify, assess and monitor multilateral organisation’s fraud risk management frameworks. These are good quality and are coherent but lack mechanisms to ensure their consistent application. As with FCDO’s wider risk management processes, processes are based on guidance and principles that can be tailored to each multilateral organisation, rather than prescriptive standards. CAAs are a key tool in identifying and assessing fraud and wider governance risks and informing monitoring of risks. Fraud and governance aspects of CAAs are generally completed to a high standard but are reliant on multilateral input and written knowing they will be shared with the multilateral organisations as a formal record of FCDO’s assessment.

The main weakness we identified is that there is no portfolio oversight across multilateral organisations, quality assurance or peer review of CAAs, negotiation of access to data or monitoring plans. As such, there is a fragmented, organisation-by-organisation approach to identifying and managing key fraud risks rather than a portfolio approach which could better focus resources and effort on managing overall risk to FCDO and maximising the positive impact on multilateral governance.

No CAA was ever undertaken for the European Commission. FCDO informed us that the UK’s contributions to EU development programming were exempt from the usual FCDO due diligence processes, with the UK relying instead on its role as an EU member in both the governance of aid and its delivery through secondments. Information provided publicly by the Commission is sufficient to track expenditure and for basic oversight of fraud risks. Combined with the UK’s prior knowledge of Commission systems, this could provide some confidence that fraud risks are appropriately controlled at present. However, funding to the Commission is expected to continue until 2029 and as time increases from when the UK was a member, there is the potential for the risk profile to change over this time period. We examine this in the following section.

Effectiveness: How effective is the UK at working with multilateral organisations and other donors to strengthen fraud risk management in multilateral organisations?

Multilateral organisations see the UK as being among the leading donors pushing for strong counter-fraud measures

FCDO officials and their counterparts at multilateral organisations agreed the UK has been one of the leading donors pushing multilateral organisations to do more to reduce fraud risks. It is also seen to have strong expertise. We saw examples of where FCDO/DFID had drawn on counter-fraud and governance expertise from across the department including Internal Audit Department, Better Delivery Department, Multilateral Effectiveness Team and overseas missions, as well as its wider networks to help manage FCDO fraud risks and to support improvements of multilateral fraud risk management in their delivery chains.

DFID had done a lot of work on fiduciary risk in country that we were able to piggy-back on. They had their own intelligence but were also able to get partners to share information with us that they wouldn’t normally share.

Multilateral stakeholder

FCDO has also consistently pushed for greater access to information than is strictly permitted under its core funding agreements with multilateral organisations, and has sought to influence systems and reporting of information relating to fraud risk to increase transparency in general and to assist the UK in managing risks in UK aid. Multilateral organisations noted some mixed messages about FCDO’s risk appetite and what it means by ‘zero tolerance to fraud risk’, consistent with findings in our previous report, and the examples we saw of some targets that risk disincentivising finding fraud, discussed in paragraph 4.17. Overall, however, multilateral organisations and other donors saw FCDO as having a strong and consistent focus on this area.

FCDO’s demands were welcomed by some multilateral organisations and seen as a burden by others. Two of the case study organisations credited the UK’s efforts with playing an instrumental role in leading to meaningful improvements in counter-fraud measures and wider improvements in governance within the organisations. These areas of improvement related to issues identified in CAAs which, in these cases, were among the tools used to help push for improvements. A third multilateral noted that, while burdensome, FCDO had helped it to manage risk better but that “the UK is very hands-on compared to other donors”.

Two of the multilateral organisations, however, felt that while FCDO demands had merit, they were ultimately more of a burden or distraction. One stated that “the UK is the most risk averse donor, bar none, especially fiduciary and reputational risk.” The other commented that the “amount of oversight requested by the UK is far in excess of that requested from other donors”.

The best results for both FCDO and the multilateral organisation occurred where the multilateral was open to support from FCDO to help address weaknesses identified through the CAA process. This requires FCDO to allocate resource, particularly expertise, which provides a significant learning opportunity for both FCDO and the multilateral as discussed in paragraphs 4.45 to 4.47. For example, FCDO was preparing risk registers collaboratively with one partner, and supported another to make improvements to its fraud risk management system.

One of the multilateral stakeholders, referring to the related issues of financial and safeguarding integrity, noted that “donors seem to be taking integrity off the top of [their] priority lists” and that FCDO, too, “is not seen as being as focused on integrity as DFID was before”. Despite being critical of the demands made by FCDO, the stakeholder requested that the UK continue to push issues of integrity and counter- fraud as a key priority at the international level, as this would provide support to those within multilateral organisations pushing for improvements.

Budget reductions may have affected FCDO’s leverage to influence multilateral organisations’ risk management systems

While some multilateral organisations are culturally more open to FCDO’s support in strengthening systems, FCDO’s leverage relates strongly to the level of funding it provides to that multilateral compared to others. Reductions in UK ODA spending targets from 0.7% to 0.5% of GNI in 2021 are expected to impact allocations to at least some multilateral organisations, although FCDO has still not finalised its spending decisions because of the reductions. Although FCDO has not yet finalised its new funding levels, FCDO and multilateral staff told us they expect initial reductions to be mainly in committed “bilateral through multilateral” funding rather than core funding. Two of our case study multilateral organisations already had significantly reduced funding.

The UK remains a valued partner in terms of thinking and principles, but after funding cuts it will be harder to push for things [… just] because FCDO have said they want it. It will be more of a negotiation going forward […]

Multilateral stakeholder

People underestimate the significance of the drop from a top three donor to the next tier in terms of influence.

Multilateral stakeholder

Organisations with unexpected reductions in funding are likely to wish to highlight the potential disadvantages to the UK and it remains to be seen what the impact of this is on the UK’s leverage in practice. FCDO’s Fraud Investigation Team noted, however, that they were seeing greater resistance from multilateral organisations in providing information and assurances in relation to fraud risks since the budget was reduced. As a result, FCDO showed us evidence it has had to reduce the amount of information requested, especially for country-level information, and use less demanding wording in its requests due to complaints by multilateral organisations.

Reductions in funding may increase fraud risk in some areas

Significant or unexpected changes in circumstances can affect the likelihood of fraud being committed (see paragraph 3.1). One of our case study organisations described substantial reductions to previously committed funding as “the most catastrophic donor event in [its] history” which had caused a lot of tension internally. While its organisational counter-fraud personnel and systems are not expected to be affected, it explained that “there is an increased fraud risk at the country level” within its aid delivery chain due to failing to meet local government expectations and creating gaps in local mechanisms that will no longer be overseen by the multilateral organisation. While this does not pose a direct fraud risk to UK aid, it increases fraud risk in these countries.

Deciding how to implement budget reductions is difficult and involves many considerations, of which fraud risk is only one. FCDO’s Fraud Investigation Team is aware of the heightened fraud risk due to reductions across the ODA budget and informed us it was working on how to manage it, although not directly with the Institutional Teams.

Despite being the UK’s biggest multilateral ODA recipient, FCDO is not actively engaging with the European Commission on fraud risk management

FCDO’s EU development team has not actively engaged with the Commission on fraud risk management since late 2018 due to the UK-EU exit negotiations. As noted above, the UK’s withdrawal from the EU means it no longer has a governance role in how EU funds are spent. In addition, the UK no longer has secondees in EU institutions, and the EU development team itself has been reduced from 20 FTE staff to 7. Substantial legacy commitments remain, however. In each of 2020 and 2021, approximately £1.5 billion of UK aid was spent through the EU, the largest UK aid allocation to any multilateral by far, and a further £3 billion of ODA is expected to be spent through the Commission between 2022 and 2029. Based on current FCDO estimates, the Commission will remain in the top 10 core multilateral recipients of UK ODA until at least 2027.

Previously, DFID’s EU development team engaged regularly with the European Commission on programme issues such as fraud and corruption, using the recommendations from the 2016 Multilateral development review and earlier assessments. During the UK-EU exit negotiations, there was a reduction in formal and informal bilateral meetings on operational issues, including audits, fraud and evaluations, as of late 2018. As a major member state and leading development actor, the UK had significant leverage to influence approaches to fraud risk management, which it no longer has. From mid-2019 to the UK’s withdrawal from the EU on 31 January 2020, FCDO needed formal approval from the former Department for Exiting the European Union to participate in formal EU committee meetings such as the European Development Fund and trust funds.

FCDO collaborates effectively with like-minded donors, but not with the European Commission

FCDO collaborates with other donors to help work towards positive change in fraud risk management and wider governance through formal and informal channels on a range of topics, including fraud. We saw examples of FCDO and other donors sharing information when they found out about suspected fraud from multilateral organisations and working together to lobby for change through donor groups, such as the G12+ Group of the 16 top humanitarian donors. Outside of our sample case studies, we noted FCDO working with other donors to address concerns about a multilateral organisation whose audit function had not grown with the organisation, and another organisation with weak systems and capacity that has made improvements as a result. Other major donors also told us that FCDO is respected and listened to in this field.

A further example of effective collaboration is the UK working with Australia to undertake joint CAAs of four multilateral organisations. As ICAI has previously noted, donors find it difficult to share due diligence information resulting in duplication of effort.60 This is an important step towards reducing the audit burden in a way that meets all donors’ requirements, and better sharing of due diligence between donors.

As well as spending substantial amounts of UK ODA, the European Commission is also a large and influential development actor and among the most aligned with the UK on issues of fiduciary risk management. It is therefore an important partner in pushing for strengthening multilateral fraud risk management, transparency and broader governance. Although FCDO’s EU development team is no longer having bilateral meetings on audits, evaluations, fraud and anti-corruption issues with its counterparts, there are some examples of collaboration between the UK and the Commission as donors that could be built upon. For example, the UK Mission in Geneva’s Humanitarian Counsellor and the Commission’s Directorate-General for European Civil Protection and Humanitarian Aid Operations (ECHO) collaborate with other like-minded donors, such as the US, to push for common objectives, including around governance and risk management, with humanitarian multilateral organisations. FCDO’s EU development team noted that it will need to build a new relationship with the Commission which is likely to involve engaging with other non-member donors such as the US and Canada on common objectives. The EU Institutional Lead asserted that any future bilateral collaboration on fraud and fiduciary risks would need to be led by FCDO policy lead on those issues and the Commission counterpart (such as OLAF and the Court of Auditors), rather than be the responsibility of the EU development team which would provide support and lesson learning.

FCDO is changing its main ODA record management system

During our review, FCDO’s ODA record management system, Vault, was locked down due to system security concerns, making key documents inaccessible. FCDO manages fraud cases on a separate system so these were not directly affected. However, FCDO staff could not access key documents needed to manage risks with partners, such as agreements with multilateral organisations, and struggled to provide all the information we requested. FCDO partially resolved this during our review, enabling access to some read-only documents which FCDO could then share with us.

Vault enabled easy access to most files across the whole of the former DFID, including to some contractors. Following the merger, FCDO has transitioned to Microsoft Teams, which restricts access to anyone outside a specified team from accessing records unless actively permitted by an authorised individual. This reduces the risk of misuse of data but also has potentially negative implications for knowledge sharing, investigations and transparency, which will need to be managed.

Conclusion on effectiveness

Multilateral organisations see the UK as a leading voice in promoting good counter-fraud practices. The UK has worked collaboratively with multilateral organisations to help them meaningfully improve their systems, but they also see the UK as administratively burdensome. Since reducing its aid budget, the UK has seen some pushback on its demands for access and information beyond formal agreements. The devolved approach to fraud risk management means multilateral organisations are treated differently depending on the UK’s leverage and the multilateral’s openness to UK influence, rather than relative to their risks.

There are good examples of where the UK has successfully collaborated with like-minded donors to improve counter-fraud practices in multilateral organisations and, in the case of joint CAAs with Australia, to reduce the burden of multiple assessments and increase sharing of due diligence information between donors. However, from the point of view of managing fraud risks in global aid, its lack of engagement with the European Commission is concerning because it is one of the largest and most influential aid agencies and is also closely aligned with the UK on the importance of counter-fraud issues.

Learning: How does the UK capture, apply and share its learning on fraud risk management internally and externally?

Secondments of FCDO staff have delivered significant value to multilateral organisations but FCDO has not effectively captured and used learning

FCDO has provided expertise to multilateral organisations through secondments (and other appointments such as to a multilateral organisation’s finance and audit committee), to help them address counter-fraud and wider governance issues (see Box 5 and Box 6 for examples). As explained below, these have proven to be excellent value for money, both in learning for the secondee and benefit to the multilateral. They have led to some important improvements within multilateral organisations and helped to address more serious concerns identified in CAAs.

[Secondments from FCDO have been] very helpful – the UK tries to identify colleagues with specific technical expertise.

Multilateral stakeholder

The best examples of secondments being used to help strengthen multilateral organisations’ fraud management systems and governance that we saw were when the multilateral and FCDO team had previously built trust and worked together to determine who and what the support would look like. In the secondments relating to our case studies, the selection processes were competitive within FCDO and the multilateral was involved. Even with one multilateral facing what it described as “catastrophic” reductions in funding from FCDO, it continued to welcome and recognise the value of an FCDO secondee. This suggests secondments could help the UK maintain influence and contribute to strengthening systems in multilateral organisations, even where it may have less financial leverage.

Box 5: Example of a DFID/FCDO secondee to a multilateral organisation

In its due diligence of one of the case study multilateral organisations, DFID/FCDO identified weaknesses in the organisation’s procurement and supply chains that exposed its funding to significant fraud risk. The multilateral organisation acknowledged that it needed support and expertise in this area – specifically assurance at the end of the aid delivery chain – and that it lacked the capability to drive the necessary change.

DFID/FCDO and the multilateral organisation agreed to appoint a secondee with expertise in this area. The secondee told us that being embedded in the organisation and building strong relationships allowed them to gain deeper insights into the complexities of the supply chains, which included multiple in-country actors, more so than a regular due diligence assessment of the multilateral organisation would have afforded DFID/FCDO.

Over time, they identified that upskilling of staff across this chain would significantly strengthen visibility and accountability. DFID therefore, in partnership with the organisation and other stakeholders, provided webinars and seminars to train in-country stakeholders on spot checks and assurance processes. The multilateral organisation also piloted a corporate-wide initiative on strengthening its supply chains with support from DFID/FCDO. This pilot, according to FCDO staff, yielded positive results and the organisation has now formed a department specialising in assurance at the end of the aid delivery chain.

Box 6: Example of a strategic FCDO appointment to a multilateral organisation

FCDO can sometimes appoint UK staff to the boards of the multilateral organisations it funds. FCDO appointed a senior member of its audit team to the finance and audit committee of one of the multilateral organisations selected for this review, a move which was positively reviewed by both FCDO staff and their counterparts within the multilateral.

The FCDO appointee told us that this was a highly strategic way of supporting and influencing multilateral management of fraud risk, and that the multilateral organisation welcomed their knowledge and support, which the organisation confirmed. The appointee drew from their expertise to provide specific recommendations for how to improve internal audits and manage the complex exposure to risk the multilateral organisation faced. They saw significant improvements during their tenure.

In turn, the multilateral organisation told us they welcomed FCDO’s expertise and could leverage FCDO’s in-country presence, benefitting from FCDO’s relationships with local partners and its ‘ears on the ground’. Staff noted FCDO had adapted its stance on risk during this time from one of passing risk down the supply chain, with a zero-tolerance approach, to a more constructive position of sharing risk as a partner and tackling it across the chain.

There are three main ways in which FCDO can learn through secondments: sharing of lessons from the secondee to their own FCDO team to strengthen its broader understanding of that organisation; sharing of lessons among secondees working with other multilateral organisations to support their work; and, capturing and applying lessons to help FCDO and other government departments engage more effectively with multilateral organisations individually and collectively.

There is, however, no network linking secondees or mechanism to capture and share learning beyond the teams and multilateral organisations involved. Beyond the technical subject, a key opportunity to learn more widely within FCDO about the internal politics of multilateral organisations, the perspectives and pressures faced by multilateral staff and how to most effectively influence them is being lost. Although multilateral organisations have differences, there is untapped potential for significant learning across FCDO rather than just within individual teams.

Where FCDO counter-fraud and governance expertise has been drawn upon to support multilateral organisations it has been very effective, but this is relatively rare, with most secondments focused on programmatic support. Furthermore, as these individuals are drawn from various parts of FCDO and there is no coordination of secondee learning, so learning is even more fragmented.

Networking and learning on fraud with the European Commission is not happening

As noted above, the Commission is both among the most influential donors and most aligned with UK priorities in its focus on counter-fraud issues and therefore both parties are missing out on potentially valuable learning opportunities. As the UK and European Commission develop a new working relationship following the UK’s exit from the EU, the previous high levels of engagement and learning around fraud by FCDO’s EU team have stopped. FCDO’s EU team has reduced from 20 to 7 and is expected to be reduced further as funding diminishes. The team does not have the objective to engage and share learning with the Commission on fraud in the way that other Multilateral Teams do. The Institutional Lead considered this role to be more appropriate within a central team responsible for policy engagement on fraud risk management with the right capacity and networks to take forward lesson learning with the Commission and other donors, rather than within the EU development team itself. As such, lesson learning engagement on fraud with the Commission is not owned by any team within FCDO. There is no objective to do this within the EU team, counter-fraud team or Multilateral Effectiveness Team, and there is no plan to develop it.

The lack of peer review is a missed opportunity

As noted in paragraph 4.13, there is no quality assurance of CAAs or monitoring plans, and the Multilateral Effectiveness Team does not have counter-fraud expertise. While the Multilateral Effectiveness Team does not have the capacity or capability to manage a quality assurance process, peer reviews of CAAs and monitoring plans would help to ensure high quality, improve consistency and facilitate learning across Multilateral Teams. Without this, the opportunity to learn across Multilateral Teams and FCDO more widely is being lost.

We saw examples of where UK overseas missions had shared important information with Institutional Leads and multilateral organisations themselves to help flag fraud concerns and manage fraud risks. With one of our case study organisations, this included intelligence that has led to funding being put on hold while investigating issues and making changes. Two of the multilateral organisations consulted for this review, however, expressed frustration that UK overseas missions were not always joined up with the Multilateral Teams, resulting in duplicated requests or disproportionate focus on lower-risk areas. While this review did not look at country-level due diligence for bilateral funding to multilateral organisations, peer review and more centralised information requests also have the potential to reduce the risk of duplication or unduly onerous or disproportionate information requests.

The Cabinet Office-led Counter Fraud Function, in its oversight and support of fraud risk management across government departments, does not specifically look at fraud risk across FCDO’s multilateral portfolio, assessing compliance only at the departmental level. In our previous report, we outlined the lack of linkage between counter-fraud expertise in FCDO and the Counter Fraud Function. This is also the case with Institutional Leads, meaning learning at the multilateral level may not be captured within the Counter Fraud Function.

Conclusion on learning