The Effectiveness of DFID’s Engagement with the Asian Development Bank

Executive Summary

The Independent Commission for Aid Impact (ICAI) is the independent body responsible for scrutinising UK aid. We focus on maximising the effectiveness of the UK aid budget for intended beneficiaries and on delivering value for money for UK taxpayers. We carry out independent reviews of aid programmes and of issues affecting the delivery of UK aid. We publish transparent, impartial and objective reports to provide evidence and clear recommendations to support UK Government decision-making and to strengthen the accountability of the aid programme. Our reports are written to be accessible to a general readership and we use a simple ‘traffic light’ system to report our judgement on each programme or topic we review.

Green: The programme meets all or almost all of the criteria for effectiveness and value for money and is performing strongly. Very few or no improvements are needed.

Green-Amber: The programme meets most of the criteria for effectiveness and value for money and is performing well. Some improvements should be made.

Amber-Red: The programme meets some of the criteria for effectiveness and value for money but is not performing well. Significant improvements should be made.

Red: The programme meets few of the criteria for effectiveness and value for money. It is performing poorly. Immediate and major changes need to be made.

This review considers the effectiveness of DFID’s engagement with the Asian Development Bank (ADB) and its influence on the Bank’s activities. ADB is one of several multilateral banks that DFID works with to reduce poverty. ADB’s core skills are in delivering large-scale infrastructure projects in middle-income countries, complementing DFID’s focus on the poorest through governance, growth, health and education.

DFID provides financing to ADB in three ways:

- it has invested $113 million and committed to a further $53 million, making it a 2% shareholder;

- over the past five years, DFID contributed £175 million to the Asian Development Fund (ADF), which provides concessional financing to low-income countries; and

- over the past five years, DFID has also contributed £229 million to co-financed projects and trust funds, where ADB is the delivery agent.

Overall

Assessment: Green-Amber

As a shareholder, the UK has a positive influence on ADB’s strategy, policy and internal reform – these are yet to result, however, in ADB achieving its own impact targets. Through the replenishment of the ADF, DFID has promoted a continuing focus on inclusive growth, gender, climate change and operational effectiveness. In order to improve ADB’s delivery of outcomes, DFID needs to influence the Bank to improve project management and real-time monitoring.

As a co-financier, DFID engages effectively with ADB to develop country strategies and co-ordinate amongst donors. DFID should, however, provide greater support to ADB during implementation to improve the performance of co-financed projects, particularly in areas where ADB has less expertise.

Our review is more critical than the Multilateral Aid Review’s (MAR’s) conclusions in respect of ADB, largely reflecting our greater concentration on project delivery.

Objectives

Assessment: Green-Amber

DFID is an effective minority shareholder. It sets clear objectives for its relationship with ADB and uses ADF replenishments to reform the Bank and focus on results. As a co-financier of projects with ADB, DFID has sometimes been overambitious and shown insufficient evidence of taking political risks into account in project design. A greater focus on design is particularly important when partnering with ADB on issues where it has less expertise in-country, for example, in education or health.

Delivery

Assessment: Amber-Red

As a shareholder, DFID’s assurance of ADB processes provides confidence that financing is spent well and as intended – including a clear policy on anti-corruption. DFID has made significant progress in supporting ADB internal reform but it is too early to see the effects of this on impact. As a co-financier, DFID does not always give sufficient attention to managing projects in-country. In complex environments, project design requires close monitoring and flexibility.

Impact

Assessment: Green-Amber

DFID’s support for ADB is delivering benefits for the poor. DFID should now focus on actions that will help ADB to meet its development outcome targets. Co-financed projects are delivering results and the leverage of working with other donors improves value for money; these projects, however, are not fully delivering their planned outcomes.

Learning

Assessment: Green-Amber

DFID used its experience of working with ADB to set its strategy for the latest ADF replenishment. As a co-financier, DFID learns from its delivery experience with ADB, using this in its approach to future projects. Better real-time monitoring and evaluation could improve programme delivery.

Recommendations

Recommendation 1: Where DFID is co-financing projects with ADB, it should be clear about the relative contributions of each partner, strengthen its initial risk assessment and resource accordingly and improve its real-time monitoring and evaluation.

Recommendation 2: As a shareholder, DFID should concentrate its influence on improving the impact of ADB and ADF projects, in particular by strengthening project design, implementation and independent evaluation.

Recommendation 3: Ad hoc discussions between DFID country offices, DFID headquarters and the UK representative in ADB headquarters should be formalised in quarterly strategic reviews for the five DFID focus countries where ADB activity is significant.

Recommendation 4: DFID needs to ensure that it always has the right information to make choices about when and how to work with ADB. If DFID wishes to use the MAR for this purpose, then future MARs should consider the capabilities of multilateral agencies on the ground across a range of countries, capabilities and project types.

1 Introduction

What does ADB do?

1.1 The Asian Development Bank (ADB) is one of several multilateral development banks with which the Department for International Development (DFID) works to reduce poverty.

1.2 Recognising performance issues in the mid 2000’s, ADB’s management has worked successfully to reform the Bank, including the development of a new strategy (Strategy 2020). Under this, its vision is of ‘an Asia and Pacific region free of poverty’ and its mission is to help countries to reduce poverty and improve living conditions and quality of life.1 To deliver this vision, ADB offers a range of services to governments and private sector partners. It finances loan projects, as well as providing technical assistance, grants, guarantees and equity investments.

1.3 ADB is owned by 67 governments.2 It has two main lending instruments: Ordinary Capital Resources (OCR) and the Asian Development Fund (ADF).

Ordinary Capital Resources

1.4 OCR loans are offered at near-market rates to 24 middle-income countries. They are funded through paid-in capital from shareholders, repayments of previous loans and borrowing in international capital markets. Returns from this lending allow ADB to support financing to its low-income member countries from its own resources.3

The Asian Development Fund

1.5 The ADF offers highly subsidised loans and grants to low-income and lower-middle-income countries.4 The level of financing is provided to countries based on specific criteria, including the extent of poverty, whether a country is conflict-affected and past project performance. ADF funding is provided alongside that of other donors (including DFID) for co-financed projects.

1.6 The ADF is replenished by its donors every four years. For 2009-12, the replenishment (ADF X) was $11.3 billion.5 ADB and its donors have recently agreed an ADF XI replenishment of $12.4 billion, to start in 2013, of which 62.5% will come from the Bank’s own resources.6

The majority of ADB lending is to middle-income countries for infrastructure projects

1.7 Over the five years 2007-11, ADB disbursed $45.7 billion.7 In 2011, ADB approved operations totalling $21.7 billion. This included: OCR loans ($10.6 billion), ADF loans and grants ($2.6 billion) and co-financing (which rose to $7.7 billion in 2011 from $0.5 billion in 2007).8 Donors make more limited use of ADB for trust funds than is the case with the World Bank.

1.8 In 2011, the major borrowing countries were Bangladesh, India, China, Vietnam, Pakistan and Uzbekistan (together accounting for 70%).9 The majority of ADB financing (60%) was for transport and energy projects; only 4.3% of loans in 2011 were for education and 0.2% for health and social protection combined.10

DFID contributes to ADB through three channels

1.9 ADB’s work is important to DFID’s mission. Nearly three-quarters of the world’s poor (72%) live in Asia, including in its middle-income countries.11 Moreover, DFID’s own bilateral aid programme has eight focus countries within the ADB region. Together these countries accounted for 42% of ADB’s loan approvals in 2011 ($5.1 billion), concentrated in India, Bangladesh and Pakistan.12

1.10 The UK has three key relationships with ADB, shown in Figure 1.

- Shareholder

- 2% shareholder

- Loans to middle-income countries

UK Contribution: $113m paid-in capital, further $53m committed

- ADF Contributor

- Contribution every four years

- Loans/grants to low-income and lower-middle-income countries

UK Contribution: ADF X (2009-12): £116m ($233m)

ADF XI (2013-16): £200m ($315m) - Co-financier

- ADB as agent

- 11 projects plus technical assistance

- Bilateral aid

UK Activity: $489m active projects + $21m technical assistance

1.11 Over the last five financial years (2006-07 to 2010-11), DFID contributed £404 million to ADB. Over 40% of this (£175 million) went into the ADF and the remainder into co-financed projects (£155 million) and trust funds (£74 million). See Figure A1 in the Annex.14

1.12 ADB uses a common governance approach, policies and processes, to manage the Bank and to design and implement projects, whether OCR or ADF funded. Given this, where we refer to the shareholder relationship in the remainder of this report but do not state that we are referring specifically to OCR or ADF, the commentary applies to both.

DFID as a minority shareholder

1.13 The UK Government is a minority (2%) shareholder in ADB. It has subscribed paid-in capital of $166 million ($113 paid in to date and an agreement to provide a further $53 million by 2014).15 The UK is also committed to provide a further $3.16 billion of ‘callable capital’ in the unlikely event of large-scale default by ADB’s borrowers.16 The UK’s (and other shareholders’) paid-in capital, with financial assurance provided by the callable capital, makes ADB a Triple A-rated borrower (see Figure A1 in the Annex).

1.14 The ADB Board has 12 executive directors (EDs). Three represent single countries (Japan, the US and China). The remaining EDs represent multi-country constituencies. The UK has one representative in ADB headquarters and shares a constituency with four other countries (Germany, Austria, Luxembourg and Turkey). Roles within the constituency rotate in a four-year cycle. In this cycle, Germany is ED for three years out of the four; the UK is Adviser to the ED for one year, Alternate ED (the deputy ED) for two years and ED for one year.17

1.15 The UK does not currently hold an executive director or deputy position in its constituency. As a result, it is not directly represented on any of the six Board committees18 but attends and engages extensively with the Human Resources Committee. From July 2012, the UK will hold the deputy position for the next two years and will sit on the Human Resources Committee.

DFID as a contributor to the ADF

1.16 Managed by the ADB Board, the ADF is replenished every four years from fresh donor contributions and from ADB itself (e.g. from interest and repayments of capital).

1.17 DFID makes a proportionately larger contribution to the ADF compared to its shareholding, consistent with DFID’s focus on low-income countries. The UK committed £116 million ($233 million) to ADF X (5.07% of total burden-shared donor contributions). The UK will commit £200 million ($315 million) to ADF XI, or 5.4% of total burden-shared donor contributions (subject to final confirmation).19 The 72% increase in sterling terms demonstrates UK support for the poorest countries in Asia. It also demonstrates commitment to the ADF, following a ‘strong’ assessment in DFID’s Multilateral Aid Review (MAR).20

1.18 DFID’s relationship with ADB as a shareholder and as a contributor to the ADF is managed by the International Financial Institutions Department (IFID), which works through the UK representative at ADB headquarters. Together, they manage policy and strategy towards the Bank (including ADF allocations and outcomes), as well as the relationship with the ADB Board and inputs to ADF replenishments.

DFID as a co-financier

1.19 DFID has multiple relationships with ADB at country level and through regional collaboration where the Bank is a delivery agent for DFID-funded aid projects. These co-financed projects are managed by country offices, which work with their local ADB counterparts through the regional chain of command in DFID.

1.20 Overall, DFID co-finances a low proportion of ADB’s co-financed projects21 and its contributions centre around a few projects and countries. For example, in March 2012, DFID had 11 active development projects being co-financed with ADB, valued at $489 million (of which 89% of the value was in Bangladesh). There were another 19 active technical assistance projects with a total value of $21 million. See Figures A2 and A3 in the Annex.

1.21 DFID is also providing finance alongside ADB for two innovative, climate-related projects: the Climate Public Private Partnership (CP3, described in Figure 4 on page 9) and India Solar Guarantees.22 The UK commitment to these projects is $90 million and $10 million respectively.

1.22 Co-financed projects use a range of governance arrangements. In the case of DFID-funded trust funds, ADF and OCR projects, ADB is the agent for DFID and ADB management processes are used. In the case of parallel financing, where both DFID and ADB are contributing to a project as development partners, different governance arrangements will be agreed on a case-by-case basis.

1.23 DFID provides co-financing in three ways:

- allocating money to specific projects with ADB, which ADB manages for DFID; for example, the Bangladesh Urban Primary Health Care programme (UPHC);

- providing financing for trust funds, where funds are managed by ADB through independent arrangements; for example, the Afghanistan Infrastructure Trust Fund;23 and

- providing financing alongside ADB to a single programme but ADB does not manage DFID funds; for example, phase 3 of the Bangladesh Primary Education Development Programme (PEDP).

1.24 For project details, see Figure A2 in the Annex.

ADB has tackled mid-2000s performance issues

1.25 In the mid-2000s, some donors assessed ADB as underachieving. For example, DFID attached conditions to its contribution to the ADF X replenishment in 2007. DFID initially judged that key conditions, linked to internal reform, had not been met. In 2010, DFID decided that the conditions had been met and the conditional contribution was therefore made.

1.26 Strategy 202024 was agreed in 2008 as a response to ADB’s performance problems and to continuing concerns about the need for inclusive growth in the Asia–Pacific region. The strategy focusses on inclusive and environmentally sustainable growth in the region, to which end it proposed as a target for policy that 80% of lending should be in infrastructure, environment (including climate change), regional co-operation and integration, financial sector development and education. It also agreed a target of 50% of ADB annual operations in private sector development and private sector operations by 2020.

Independent reviews suggest areas for further improvement

1.27 There have been three independent reviews of ADB published since 2010. Our own review builds on these by looking specifically at the relationship between DFID and the Bank, at both strategic and operational levels, including where projects are being co-financed.

1.28 DFID’s MAR, published in March 2011, specifically considered the ADF (which shares management processes with ADB). It assessed 43 organisations and funds at a high level; in considering ADF, the review team visited four countries in Asia but did not consider individual projects.25

1.29 The MAR assessed the ADF as being ‘strong’ on both its contribution to UK development objectives and its organisational approaches. It stated that the ‘ADF plays a critical role contributing to international and UK development objectives. It has a clear strategic vision which supports a focus on results. Performance could be improved by ensuring that its projects have a greater impact on the poorest communities and on addressing the needs of girls.’ The main weaknesses identified by the MAR are summarised in Figure 2.

- ‘sometimes limited collaboration with other donors’;

- ‘limited role in health and activities directly addressing Millennium Development Goals’;

- ‘good policy and evaluations on gender equality but limited evidence of impact’;

- ‘no evidence of emphasis on securing cost-effectiveness in the design of development projects’;

- ‘weaknesses in HR [human resource] policies and practices are being tackled but more needs to be done’; and

- ‘very limited in-country re-allocation possible’.

1.30 DFID is a member of the Multilateral Organisation Performance Assessment Network (MOPAN), which carried out a review of ADB in 2010.27 The review recognised that ADB has been implementing reforms to improve its effectiveness. It noted that ADB had achieved progress in ‘making transparent and predictable aid allocation decisions, presenting information on performance and in monitoring external results’. The report also noted that donors in-country were generally less positive about ADB’s organisational effectiveness than donors at headquarters or client governments.

1.31 The Australian equivalent of DFID, AusAID, published its own assessment of multilateral organisations in 2012 which was positive about ADB. As a result, AusAID, like DFID, has significantly increased its commitment to ADF XI.28

Methodology

1.32 The purpose of our review was to assess the effectiveness of DFID’s engagement with ADB in order to maximise impact for the intended beneficiaries and value for money for the UK taxpayer. Although this review is not a direct assessment of ADB’s own performance, we did review the impact of ADB/DFID co-financed projects.

1.33 The review considered:

- the ways of working between DFID, ADB and other agencies, including recipient governments, at country level;

- the information which DFID receives and the assurances that it seeks about the cost-effectiveness and impact of ADB activities;

- the use made by DFID of work by ADB’s Independent Evaluation Department (IED);

- the approach adopted to co-financing, including with the private sector; and

- 13 co-financed projects.

1.34 In our approach, we considered how DFID works:

- with ADB as a shareholder;

- as a contributor to the ADF; and

- as a co-financier of projects where ADB is the delivery agent.

1.35 We held over 40 meetings with DFID, ADB, non-governmental organisations (NGOs) and other stakeholders. Our review of 13 co-financed projects included a detailed review of two health and education projects in Bangladesh, representing 70% of current, active co-financed projects with ADB. The Annex provides more details of the methodology and summarises the sampled projects (Figure A4).

2 Findings

Objectives

Assessment: Green-Amber

2.1 This section assesses how effectively DFID sets its objectives for ADB. In particular, it looks at how DFID:

- provides input to ADB and ADF strategy-setting;

- provides input to ADB’s country-planning processes;

- considers opportunities for working with ADB in developing its own country plans; and

- ensures that objectives for co-financed projects and the link between inputs and impact are relevant and realistic.

DFID has clear shareholder objectives for ADB

2.2 DFID and ADB are both working to reduce poverty but there is a fundamental difference in their approaches. ADB mainly lends to infrastructure projects in middle-income countries. By contrast, DFID mainly provides grants to low-income countries for economic growth, governance, health and education projects.29

2.3 There are areas of common interest, however:

- infrastructure is crucial to the development of Asia’s poorest countries. In this way, ADB complements DFID’s poverty reduction objectives; and

- ADB lending is important for the poorest countries. Part of net income generated from ADB operations, for example from infrastructure projects in middle-income countries, is transferred to the ADF. This funds loans and grants to the poorest countries in the region. For example, in ADF X (2009-12), 62.5% of the total replenishment was funded by repayments from existing borrowers.

2.4 The main high-level engagement between ADB and DFID is the negotiation to replenish funding of the ADF, which takes place every four years. There are also periodic calls for additional share capital for ADB, most recently in 2009.

2.5 We found that DFID’s negotiating strategy for the recent ADF XI replenishment was directly linked to the conclusions of its own MAR review and to wider UK priorities. These included:

- a measurable results framework in support of the replenishment;

- progress with internal reform of the Bank; and

- progress with issues concerning support for Afghanistan and Burma and the treatment of arrears.

2.6 The UK appears to have been successful in its negotiating strategy, in that the outcomes of the ADF XI replenishment reflected all of the UK objectives bar one. For example, donors agreed to continue the exceptional post-conflict premium for Afghanistan and to delay the phase-out period until 2018. Further discussions will be held on the eligibility of Burma to join the ADF, subject to further progress on political reform. Limited progress was made on the treatment of arrears, in the face of considerable opposition.

2.7 There is also a clear link between key MAR findings and the final draft of the ADF XI Results Framework (due to be submitted for approval by the end of 2012). Figure 3 on page 8 shows how the planned ADF XI outcomes reflect MAR findings.30

DFID uses its minority shareholding effectively to influence ADB objectives

2.8 DFID has limited resources to carry out its shareholder role in the Bank. It has 2.2 full-time-equivalent staff of whom one is a full-time representative at ADB headquarters and the others are in IFID, which leads the relationship with ADB. The UK uses this minority position well and senior management in ADB commented positively on the UK’s contributions to influencing the Bank’s policies and performance.

| MAR findings31 | ADF XI outcomes32 |

|---|---|

| Need for ADB to focus on poverty impact | ADF XI is clearly focussed on outcomes and targets, specifically poverty outcomes. This includes over 2.6 million children benefiting from school improvement programmes or direct support. Much greater focus in ADF projects on the inclusiveness of growth and its direct effect on poverty. |

| Need for cost-effectiveness in programme design | The ADF Results Framework contains new measures related to cost-effectiveness in project design and delivery. These include outsourcing where cost-efficient, improving institutional procurement and continuing ADF's organisational review of individual departments to improve efficiency. |

| Insufficient gender focus | The ADF XI Results Framework will be disaggregated by gender. Gender is a key element in 60% of the indicative projects to be financed through ADF XI; this compares to 45% of ADF approvals in 2010.33 |

2.9 In promoting policy change, the UK works closely with other country representatives to build support for its position. For example, it is an active member of ‘Europe Plus’, an informal grouping of the European states, Turkey and Canada. Europe Plus represents around 22% of ADB’s shareholding and is larger than any single constituency, which gives it considerable influence.34 This group meets weekly to discuss matters of common interest and, where possible, to issue joint statements.

2.10 The UK also works effectively within its constituency, drawing on a range of expertise to inform its policy positions.

DFID has concentrated on internal ADB process improvement in recent years

2.11 A focus of the UK representative over recent years has been to improve the quality of ADB’s internal management processes, to make them fit to deliver development outcomes. This has brought about progress. The majority of targets in operational and organisational effectiveness are being met or are on target. One example of successful improvement is the strengthening of the independent evaluation function, through the development of improved processes, the appointment of a new head (in 2011) and the launching of a change programme.

2.12 Progress has been slower in other areas of reform because of opposition from key shareholders. For example, ensuring that senior appointments are merit based and splitting the human resources function from finance. In both of these areas, DFID is closely engaged with the Board HR Committee because of the importance it attaches to human resources reform. It should continue to push for change as strongly as a minority shareholder can.

2.13 Progress on internal reforms is well advanced. The UK should now increase its focus on ensuring that reforms are improving project impact. Specifically, this will include the need to ensure that projects are closely monitored, with monitoring actions being implemented. As a shareholder, DFID recognises the need for this and some progress is being made. The ADF XI replenishment, for example, focussed on expected development outcomes.35

As co-financier, DFID works closely with ADB in-country but needs to manage the risks better

2.14 In the development of its country operational plans, DFID identifies local priorities and potential partners, including ADB, but there is no evidence that it is fully examining potential partners’ strengths and weaknesses.

2.15 Our review is more critical than the MAR’s conclusions in respect of ADB, largely reflecting our greater concentration on project delivery. The MAR considers an organisation’s behaviours and values, as well as the fit with UK aid priorities but focusses less on the operational effectiveness of delivery on the ground. As a consequence, it cannot provide assurance on this for individual DFID offices. For any future MAR to be used to inform DFID on where and how to work with ADB, it should consider the capabilities of multilateral agencies on the ground across a range of countries, capabilities and project types.

2.16 DFID has an opportunity at country level to be involved in developing the ADB Country Partnership Strategy and three-year, rolling pipeline of programmes. In some cases, DFID and ADB have gone further, for example, in the development of a tripartite strategy for Bihar state (India), also with the World Bank.

2.17 Whilst Strategy 202036 prioritises education, the dominance of infrastructure in ADB’s portfolio makes it ideal as a complementary partner for DFID, rather than as a joint development partner in the social sectors. ADB can justifiably lead where infrastructure is a major part of the requirement; for example, building schools to support others’ education programmes that are working to improve institutional performance and learning outcomes.

2.18 In several previous programmes, DFID has co-financed with ADB outside of its traditional infrastructure focus. There may be good reasons for this, for example, existing relationships with government. In Bangladesh, DFID co-financed the second phase of the primary education project with ADB because the Government of Bangladesh wanted ADB to lead the education sector programme as a trusted partner.

2.19 Once decisions have been made about sector leadership, DFID is then faced with a decision of working with the selected leader or not working collaboratively in the sector, risking the loss of the benefits of a co-ordinated donor approach. While DFID Bangladesh almost certainly acted correctly in continuing to act collaboratively in the case of the Bangladesh education sector, it should have recognised the additional risks of partnering with a lead donor that was working beyond its core competence and resourced accordingly. This is discussed further in the Delivery section below.

2.20 There is some recent evidence that DFID is more carefully considering ADB’s strengths and weaknesses in its decisions on partnering. For example, DFID will not be partnering with ADB beyond the second phase of its Making Markets Work for the Poor activities in Vietnam. DFID is also considering its partnering options for continuing its support to urban primary health care in Bangladesh, basing this decision on an independent study.

2.21 Equally, DFID is increasing its involvement with ADB in climate change (e.g. the Climate Public Private Partnership in Asia and the urban climate change resilience partnership). This is a strong fit with ADB’s expertise, as these projects involve raising private sector finance and developing infrastructure (see Figure 4).

The UK Government has provided, from DFID and the Department for Energy and Climate Change (DECC), an anchor investment of £60 million plus technical assistance. The project will run for ten years and the government should receive a commercial return that will be re-invested into an ADB trust fund.

The CP3 Asia fund sits alongside a global climate public–private partnership, managed by the International Finance Corporation, that DFID and DECC are also supporting.

2.22 In addition, DFID Bangladesh agreed to ‘further strengthen staff skills for effective management of programme partners and programme delivery’ in response to the ICAI review on DFID’s climate change programme in Bangladesh.38

2.23 There is evidence that DFID is using its minority shareholding successfully to influence ADB and leverage ADB’s financing and expertise. For example, in India, DFID is providing $21.5 million to support ADB due diligence and design work for projects in the eight poorest states. This is encouraging ADB to become more heavily engaged in these states and loan approvals have increased from $870 million in 2008 to a projected $1.3 billion in 2011.39

Objectives in co-financed projects can be weak

2.24 The evidence on the way in which DFID sets objectives for specific co-financed projects is mixed. One of the key findings of our assessment of 13 DFID/ADB co-financed projects was that some designs were weak. In these cases design was overambitious and took insufficient account of the political context. For example:

- in Bangladesh, the executing agency for the post-literacy and continuing education project was closed by the government within the first year of the project; and

- the Punjab Devolved Social Services Project in Pakistan suffered from wavering government commitment to devolution to local agencies.

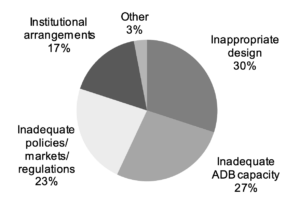

2.25 These findings are consistent with ADB findings on the reasons for project failure (see Figure 5 on page 12).

2.26 There are clear signs of DFID addressing these issues in project design for co-financed projects. A new DFID project design format was introduced in 2011, which requires a very clear description of how the project will achieve its objectives and the evidence which supports the underlying logic.

2.27 The business case for phase 3 of the Primary Education Development Programme (PEDP) in Bangladesh is in this format and describes the project objectives and how they will be measured. It also sets out clearly how the project inputs are expected to lead to its impact and the evidence underpinning the project design.

2.28 The key point, though, is that in the difficult environments in which ADB and DFID operate, even the best programme designs will be subject to external factors which affect their relevance and chances of success. Given this, effective design should not be a one-off event that happens at the outset of a project but rather a process – a project plan that needs to be measured against and adapted. These aspects of design are discussed in the Delivery section below.

Delivery

Assessment: Amber-Red

2.29 This section examines how DFID engages with ADB to ensure that delivery of its funding, whether through or alongside the Bank, is effective. Specifically, we examine how effectively DFID:

- as a shareholder, assures itself of ADB oversight of OCR- and ADF-financed projects;

- as a co-financier, ensures appropriate governance and oversight mechanisms for ADB and DFID co-financed projects; and

- engages in the project management cycle (including detailed project design, implementation and monitoring).

DFID relies on key ADB processes for its oversight of the Bank

2.30 DFID’s oversight of ADB is appropriate for a minority shareholder and a provider of a relatively low proportion of ADF contributions; DFID does not try to micromanage Bank management. Instead, through ADB reporting to the Board,40 as well as a range of discussions between the UK representative and key ADB staff, the UK assures itself of ADB’s management processes.

2.31 The UK representative circulates relevant board papers widely in DFID for comment, providing officials an opportunity to comment and influence debate. Discussions, however, between DFID country offices, the UK representative and DFID centrally around ADB policies and forthcoming projects are largely ad hoc and responsive. Given that scope for influencing by the time a project reaches the Board is limited, this is not optimal.

2.32 The internal audit function of the Bank has been subject to three external, independent reviews since 2009. These are the European Commission’s Four Pillars Assessment, MOPAN and an external Quality Assurance Review conducted by the Institute of Internal Auditors. ADB has also been assessed by its own external auditor (Deloitte & Touche). Weaknesses identified in these reviews have been addressed through a programme implemented by the Auditor General. The Bank’s Auditor General has full and unrestricted access to information and records, reporting through the President to a suitably constituted Audit Committee. On this basis and in line with the view of DFID Internal Audit, ADB appears to have appropriate financial and operational controls to manage fiduciary and other risks and achieve development objectives.

2.33 ADB is implementing a clear policy on anti-corruption that we are satisfied is appropriate and effective. The head of the Office of Anti-Corruption and Integrity (OAI) reports to the President and through the President to the Audit Committee of the Board of Directors. ADB’s anti-corruption policies are formalised in a set of Integrity Principles and Guidelines,41 which have been jointly endorsed across the multilateral development banks. Staff receive mandatory training on how to identify suspicious transactions and the channels for reporting these. There is a project integrity checklist which identifies ‘red flags’ and OAI advises in these cases. ADB maintains an updated list of over 800 individuals and organisations that are barred from any activity financed, administered or supported by ADB. 211 complaints were received in 2011, 53% from ADB staff. The main limit on the effectiveness of this function is that, whilst OAI can refer cases to national authorities, it has no mandate to prosecute individuals in recipient countries because of sovereign legal issues.42

2.34 The project management processes within ADB are formally set out and contain a range of requirements to minimise the risk that funds are misused. These include annual external audits of programmes and regular project reviews (which take place at least annually, jointly with other donors for co-financed projects). Detailed project and policy information is available on ADB’s website, which allows the public and NGOs to scrutinise ADB’s actions and hold it to account.

2.35 ADB’s evaluation function is largely independent. The head of IED reports to ADB’s Board of Directors through the Development Effectiveness Committee. There are several operational details that marginally reduce the full independence of IED. These include the need to get overseas travel approved and limits on the ability to use external consultants.

2.36 Responding to a range of criticisms of the effects of earlier projects on the poor,43 ADB has developed a clear accountability mechanism. This ensures that the effects of programming on all those affected are fully considered during design and particularly that those negatively affected by its programmes are identified, consulted and adequately compensated. ADB screens and reviews all projects for potential negative impacts related to the environment, involuntary resettlement and indigenous peoples.

2.37 ADB has a results framework, providing annually updated performance information on both ADB and the ADF. This provides performance management information that DFID uses to inform its engagement with ADB, including ADF replenishment negotiations.

2.38 Overall, these processes provide assurance that DFID financing is spent well and as intended and that any negative effects of ADB projects on the vulnerable are mitigated. Material issues in any of these areas will be identified by the relevant board committee and reported to the Board. DFID, through its representative, can influence these discussions, for example, its involvement in the appointment of a new head of IED.

Current oversight of major co-financed projects by DFID appears insufficient

Weaknesses in implementation

2.39 Accountability for co-financed projects with ADB is the same as for bilateral projects. DFID is fully accountable for ensuring that these funds are well spent and that they achieve development impact.

2.40 In several of the projects that we examined, there were weaknesses in programme implementation. In particular, the poor design discussed in the Objectives section made it unlikely that those projects would deliver as expected, unless modified.

2.41 We accept that these are complex environments in which to deliver; some project risks are likely to materialise and assumptions may change. That said, in several of the projects there was evidence of DFID not doing enough to deal with projects going off track. An example of this is the Bangladesh Primary Education programme (phase 2). The World Bank carried out a Post Completion Review after the end of the programme and once all of the funds had been disbursed.44 This review identified weak design as limiting the results of the programme. The project was approved in 2004 but ‘the pace of implementation was weak up to the mid-term review’ in 2007. In this case, DFID relied too heavily on the government as the executing agency and ADB as the lead donor to ensure that recommendations agreed in joint review missions were actually implemented. Better real-time monitoring and closer engagement by DFID would have allowed the design flaws to have been acted on earlier.

2.42 The issues that we found in the sample projects were consistent with ADB’s own assessment of the reasons why projects fail to deliver (see Figure 5). Over the period 2009-11, ADB rated 68% of its ADB and 67% of its ADF sovereign operations as ‘successful’.45 80% of project failures were due to weak design, inadequate ADB capacity and inadequate policies, markets or regulations.

2.43 Issues with design and implementation are particularly relevant where ADB has less sector expertise, for example, in education and health. There may be good reasons to partner with ADB or accept their leadership in these sectors. Where this is the case, however, DFID must fully consider the risks and resource implications of working with ADB where ADB is working beyond its core expertise. For example:

- the Devolved Social Services in Punjab programme, where there was government reluctance and delays in devolving responsibility to local agencies; and

- the Vietnam Making Markets Work for the Poor programme, which faced delayed implementation and procurement following design changes.

2.44 In other areas, ADB appears strongly placed as a partner, for example in climate change and private sector financing. The experience to date on the CP3 project has been positive, with ADB working closely with DFID and DECC. DFID has, however, struggled to make available sufficient suitable staff resource during design.

Case studies of co-financed projects in Bangladesh raised important issues about DFID’s oversight

Projects are delivering positive outputs but are less successful in delivering development outcomes

2.45 As part of this review, we considered in detail two DFID/ADB co-financed projects in Bangladesh.47 These were the PEDP and the Urban Primary Health Care programme (UPHC). Figure 6 summarises the purpose, inputs and results of the two projects.

2.46 Both projects are moving into another phase. On the PEDP, the DFID business case has been approved for joint co-financing with nine donors, including ADB; there is no lead donor. On the UPHC, DFID is currently considering the most appropriate approach for a follow-on phase. A lack of donor resources limits DFID’s ability to monitor implementation and act on findings.

2.47 While these projects were achieving results, the evidence suggests that there was scope to deliver more. For example, a senior Government of Bangladesh official stated that DFID was perceived to trust ADB and the government (as executing agency) too much during implementation. In addition, it was clear that implementation resources were stretched across all donors. One donor stated that in the PEDP phase 2 consortium, ‘we are all hoping that everybody isn’t doing the same as us’ – implying that donors were relying on each other on the basis of hope, rather than taking their own responsibility on the basis of evidence.48

| Factor | UPHC Phase 2 | PEDP Phase 2 |

|---|---|---|

| Purpose | Delivering health care to urban poor and women | Improving access and quality in primary education |

| Timing | 2005-12 | 2004-12 |

| DFID contribution | $25 million grant | $150 million grant |

| Total financing | $90 million | $1.82 billion |

| Results achieved | 35.8 million treatments provided to 9 million patients 7.3 million children immunised 78% of users female (>60% target) 38% of users poor (>30% target) | 45,000 new and 430,000 serving teachers trained (on target) Net enrolments rose from 87.5% (2005) to 95.6% (2010) (target of 90% exceeded) |

| Evaluation | DFID, independent evaluation: 'moderately did not meet expectations'; concerns around service quality and financial sustainability. | World Bank Project Completion Report: weak design with insufficient focus on difficult policy issues. Weak implementation at least until mid-term review. |

2.48 The table shows that the two projects have been able to deliver and even exceed a number of the outputs specified in the original design. They have, however, been less successful in delivering their intended development outcomes. This reflects the outcomes being inherently more difficult to achieve because, in these cases, they require long-term institutional and policy change.

2.49 The relative lack of resources to monitor the programmes closely fed through into the evaluations. For example, the PEDP phase 2 Project Completion Review by the World Bank found weaknesses in design and implementation.

Resources in DFID Bangladesh are spread thinly

2.50 Across donors, more staff with more experience could improve DFID’s ability to monitor implementation and act on findings. DFID Bangladesh is potentially strongly resourced to support implementation in these projects. Overall, it has 45 programme staff in-country – compared to 23 in ADB.50

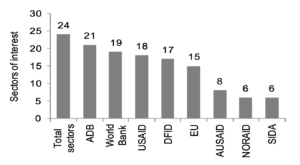

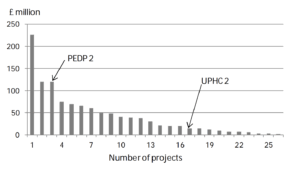

2.51 Figures 7 and 8 show how DFID Bangladesh is spread across projects and sectors.

2.52 Figure 7 shows that DFID is spread thinly across sectors. The donor co-ordination process for Bangladesh has identified 24 sectors and sub-sectors of potential donor interest. DFID has a stated interest in 17 of these.

2.53 Figure 8 shows that DFID staff are spread across 26 active projects. Of these projects, the largest three account for 41% of the total operational portfolio value; the smallest ten projects account for only 7% of the portfolio value. While smaller projects may be transformational, they can be as administratively costly as larger projects.

2.54 The result of this broad spread of interest is that DFID has relatively light staffing for large projects. DFID Bangladesh estimates that it currently has one full-time-equivalent member of staff for its implementation of phase 3 of the PEDP, which has a complex results-based funding model (DFID contribution $190 million). It also estimates that it has a 0.5 full-time-equivalent member of staff for the UPHC (DFID contribution $25 million).

2.55 There is an opportunity in Bangladesh for DFID to provide leadership in areas where it has strong expertise, most notably in education and health. To provide the resources for leadership in these areas, DFID Bangladesh could consider narrowing its focus, by supporting fewer, larger projects in fewer sectors.

ADB is more centralised than DFID, leading to delays

2.56 In our case study projects, including in Bangladesh, the need for referral to ADB headquarters in Manila was cited as a cause of delays in decisions and project delivery.

2.57 The different levels of decentralisation of ADB and DFID also affect how they interact with each other and their ability to deliver effectively on the ground. DFID is decentralised with authority at country level; country heads of office are able to approve new projects with a value of up to £20 million (larger or innovative projects are referred to the centre for approval). By contrast, ADB is much more centralised with authority in its headquarters. This means that project-related decisions are referred to headquarters, causing delay. In future, when it is co-financing major projects with ADB, DFID should require that the Bank provide local resourcing with the seniority and delegated authority to make decisions about operational issues.

NGOs in Bangladesh are broadly positive about their working relationships with ADB and DFID

2.58 We spoke to five NGOs in Bangladesh, including three with an education and health focus, about their experience of working with DFID and ADB. Several of these organisations were also recipients of DFID funding and, as a result, might have been less willing to criticise.

2.59 NGO representatives in the education and health sectors were positive about the extent to which they were engaged by DFID and ADB. Another NGO commented, however, on specific cases in which those negatively affected by ADB projects had not been engaged in programme design decisions.

2.60 An NGO service provider to the UPHC had not always received payment on time. This had taken some time to resolve and ‘every conversation ends with “We will ask Manila”‘.

2.61 A major NGO, which works closely with DFID, was positive about its interaction with DFID but was not very aware of DFID’s work with ADB in education or health. There is clearly a need for DFID to encourage greater information-sharing and dialogue. This is particularly the case given DFID’s role as a co-financier in education and health and given the need for a joint public and NGO approach in these sectors in Bangladesh.

Government of Bangladesh officials are positive about their working relationships with DFID and ADB

2.62 Senior Bangladeshi government officials were positive about DFID’s engagement in Bangladesh. In particular, they appreciated the quality of their engagement with DFID staff. They also welcomed DFID’s willingness to align its programmes with the Government of Bangladesh five-year development plan and the key role that DFID had played in encouraging donor co-ordination.

2.63 Senior officials also welcomed the innovative approach to linking payments to performance through the use of disbursement-linked indicators being adopted by donors, including DFID, in phase 3 of the PEDP.

2.64 Officials expressed some concern about the reliability of DFID financing; this had also been reported by ADB related to a project in Nepal. In the PEDP phase 2 case, funding had been reduced by £13 million in response to a failure to meet programme targets and as part of a wider DFID Bangladesh country prioritisation process. This reflects well on DFID’s willingness to take tough decisions in response to programme targets not being met. There is a need for clear communication with partner governments about these difficult decisions.

Impact

Assessment: Green-Amber

2.65 This section considers how DFID ensures delivery of development outcomes through projects supported by ADB core funding or DFID co-financing. In accordance with our mandate,53 our assessment of ADF projects was based on secondary sources, primarily ADB and DFID reporting.

DFID’s core contributions to ADB and the ADF are delivering impact

2.66 DFID’s subscribed paid-in capital to ADB is currently $166 million. In 2011, the Bank disbursed $7.72 billion of loans from its Ordinary Capital Resources. ADB estimates that this led to 24 million children benefiting from school improvement programmes and 2.2 million households gaining a clean water supply. As a 2% shareholder, DFID’s imputed share of this lending is around $150 million and so it can claim a similar share of these results.

2.67 Between 2005 and 2011, ADF estimates that it provided 19 million children with access to quality education and 2 million households with a clean water supply. DFID’s contribution to the ADF over the period 2005-11 was 2.2% of total ADF financing and so it can claim a similar share of these results.54 It should be noted, however, that this is a relatively weak measure of impact requiring an assumption of direct causality from DFID support. In practice, DFID is one of many donors (30 in ADF X) and projects also include financing from recipient governments.

As shareholder, DFID should focus on supporting ADB to improve its outcomes

2.68 ADB’s Development Effectiveness Review for 2010 shows that ADB is falling short of some of its own ambitious outcome targets.55

2.69 The key results from this review are set out in Figure 9. These are consistent with ADB having completed the early stages of a reform programme. For example, it is reforming its project design processes and the time taken to process a loan is on target (at 16 months, very similar to the World Bank). Improvements are also taking place in quality of design and in project performance during implementation.

2.70 We would, however, expect it to take several years before seeing progress on improving the outcomes of projects. Projects have an average life of around five years. Given this, projects completed in 2008 would have been approved by the Board in 2003 and may have started design as early as 2000.

2.71 This is consistent with a conclusion in the Delivery section of this review – that DFID has been successful in promoting process reforms. Looking forward, however, the focus of DFID’s influence in ADB, whether as a shareholder or co-financier, should now shift to implementation and to strengthening the link between improved processes and poverty outcomes.

ADB is taking steps to introduce a results culture

2.72 ADB has led the way amongst multilateral development banks in monitoring and publishing results through a corporate scorecard and an annual development effectiveness review. While there are some issues about the extent to which ADB is meeting its outcome targets, the fact that it has clearly articulated and published targets is good. MOPAN, in a survey in 2010, was positive about ADB’s achievements in managing for results. It did, however, recognise the need to strengthen its monitoring and reporting of outcomes for recipient countries (see Figure 10 on page 17).

2.73 ADB is using its Results Framework to create a more results-based culture. Results Framework targets are being cascaded down through the organisation, so that individual members of staff can directly link their job objectives to the Bank’s broader objectives and Results Framework achievements.

2.74 DFID uses its position as a shareholder to monitor ADB performance through the Board. The UK has been a positive voice within the Bank on the results agenda and has contributed to the progress over recent years.

| Indicator | Year | ADB | ADF | Target | ADB Status57 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Completed sovereign operations: % successful | 2009-11 | 68% | 67% | 80% | Red |

| Completed technical assistance projects: % successful | 2009-11 | 78% | 76% | 80% | Amber |

| Quality at entry of sovereign projects:58 % satisfactory | 2010 | 89% | 94% | 85% | Green |

| Project performance during implementation: % satisfactory | 2010 | 75% | not avail-able | 80% | Amber |

| Average sovereign operations processing time: (months)59 | 2010 | 16 | 16 | 16 | Green |

Co-financed projects are delivering impact

2.75 It is clear that DFID funding, alongside that of other donors, has delivered some strong outputs. The data on results from the two case study projects in Bangladesh are shown in Figure 6 on page 13. 7.3 million children have been immunised as a result of phase 2 of the UPHC. Net primary school enrolments in Bangladesh rose from 87.5% to 95.6% as a result of the second phase of the PEDP. It should be noted, however, that this is also attributable to financing from other donors and the recipient government.

2.76 In addition, we visited three health facilities that are financed under the UPHC and a public school supported under phase 2 of the PEDP. These interventions are making a difference for the poorest in Bangladesh, in an extremely difficult operating environment (see Figure 11).

More impact could be achieved, particularly if delivery issues are addressed

2.77 This review assessed a sample of 13 DFID and ADB co-financed projects. The Delivery section of this report highlighted a range of issues in project design and delivery. These weaknesses feed into less-than-expected impact. For example, a review of the Devolved Social Services Programme in Punjab shows an ambitious design and a project which was only ‘partly successful’ in delivering its outcomes.61 DFID’s review of the second phase of the UPHC in Bangladesh found that it ‘moderately did not meet expectations’.62 Key impact findings for DFID/ADB co-financed projects are summarised in Figure A4 in the Annex.

Urban Primary Health Care

At the clinics, medical staff were available and treating patients. In discussions, patients said that health staff were generally available. Medical staff said that required medicines were available at central clinics and patients said that generally medicines were available at local clinics. The physical environment of the health centre was extremely basic.

Primary Education Development

At the school, all teaching posts were filled with qualified staff, books were available and enrolment and completion rates were high. It was not possible to assess learning quality.

Learning

Assessment: Green-Amber

2.78 This section examines the extent to which DFID:

- supports ADB in learning from its core and co-financed projects during their delivery and uses this information to improve project design;

- draws lessons from ADB core and co-financed projects for new projects and policies; and

- supports ADB in using independent evaluation to improve the strategy, design and delivery of core and co-financed projects.

As a shareholder, DFID can be confident in ADB’s internal independent evaluation function

2.79 Independent evaluation is a crucial element of the drive to improving results in ADB. IED is independent and reports directly to the Board through the Development Effectiveness Committee (DEC), the main forum where the work plan is agreed and all IED reports are reviewed. The evaluation function is also relatively well resourced compared to other multilateral banks.64

2.80 IED is highly transparent. Key reports and findings are published immediately on completion to the ADB website.

2.81 The UK is represented on DEC through the constituency Executive Director. This channel is used by the UK to review and shape the work programme and to respond to key reports.

2.82 IED’s reporting structure provides a strong degree of independence. Recent independent reviews of progress are broadly positive. For example, a MOPAN study of organisational effectiveness rated ADB’s independent evaluation function as ‘very strong’ in carrying out evaluations of ADB projects and programmes and communicating with the Board about evaluation activities conducted.65 An Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development–Development Assistance Committee review in 2010 was, however, critical of the extent to which monitoring of projects during implementation was carried out.66

2.83 There is also evidence that DFID among others is having some impact on increasing the importance attached to gender, through greater focus when setting targets and measuring results. A third of all studies in IED’s 2009-11 work plan related to gender.67

DFID is adapting its approach to partnering with ADB

2.84 DFID appears to be adapting its approach to partnering with ADB. There is evidence of increasing engagement in areas where ADB is experienced and well resourced; for example, in climate change, where the challenges include raising and structuring private sector finance and developing infrastructure. There is also evidence of reducing engagement in areas where ADB is less able to provide leadership. One example of this is the decision to work as a parallel co-financier rather than under ADB leadership for phase 3 of the PEDP in Bangladesh. Another example is the decision not to partner with ADB in continuing Making Markets Work for the Poor activity in Vietnam.

More real-time evaluation would improve project impact

2.85 Evaluation of programmes at the end of their life is critical for learning lessons. During the lifetime of a project, real-time evaluation is key to improving effectiveness and value for money so that, if required, projects can be adjusted prior to all of the money being spent. There is evidence of insufficient attention to this in some ADB programmes.

2.86 For example, at the end of 2011, the World Bank published its Project Completion Review of the ADB-led Bangladesh PEDP Phase 2. This found that the ‘quality at entry’ of the project (i.e. its design) was weak.68 This was after the end of the project and the disbursement of all funding. While there was a range of earlier reviews, they did not trigger sufficient improvements in project implementation. Acting on the results of earlier reviews would have improved both the design during implementation and the eventual effectiveness of the project.

2.87 DFID should encourage ADB to carry out more real-time monitoring and evaluation of projects during implementation, covering core funded ADB and ADF projects, as well as co-financed projects. DFID should also encourage ADB to make full use of IED’s electronic system for monitoring evaluation action points. Recommendations from IED evaluation studies are entered into the Management Action Records System, progress is recorded and self-evaluated by operations departments periodically and the results are validated and published annually by IED.69

2.88 DFID should also consider the scope for encouraging ADB to ensure that evaluation results are used to improve performance. This is consistent with the ADB DEC view that the Bank needs to bring more evidence of results into project and policy design. There is some evidence that this is currently insufficient. For example, IED is currently carrying out an evaluation of social protection work in ADB. The Bank, however, is due to publish its new social protection policy before these findings are available.

2.89 IFID monitors the performance of individual ADB projects on an exception basis and DFID country offices will flag major issues with co-financed projects or concerns about proposed projects. The UK representative gets involved when DFID country offices need support to address issues with ADB. For example, in one of the co-financed projects that we reviewed, a discussion by the UK representative with ADB staff triggered an immediate visit by an ADB director to the country concerned and action was taken to improve project performance. In another country, the identification of an issue in cross-donor working through the UK representative led to a change in the ADB country-level approach.

Follow-through on lesson learning could be stronger

2.90 Learning is incorporated into ADB and DFID project management processes. For joint projects, both ADB and DFID systems require a minimum of annual joint reviews (which include the executing agency and key donors). DFID takes part in these reviews, for example in Bangladesh and Nepal.

2.91 Responsibility for implementing agreed actions is left to the executing agency (i.e. the government). In neither of the two detailed case study projects (the second phases of UPHC and PEDP in Bangladesh) did implementation always take place. DFID relies on ADB and the executing agency to ensure that actions are implemented. This links to the findings in the Delivery section of this report – that the resources allocated to project implementation did not always reflect project risks.

DFID is using independent project assessments

2.92 In two of the 13 projects we reviewed, DFID commissioned or planned to commission an independent assessment to provide information about the impact of the projects and to help make decisions about future support (the UPHC in Bangladesh and Making Markets Work for the Poor in Vietnam). We examined the UPHC phase 2 review; it appeared to be rigorous and to provide a good basis for the design of a subsequent phase.

2.93 More generally, DFID is using a range of evidence, including these types of reviews, to learn the areas in which there is a strong rationale for working closely alongside ADB (for example, climate change, infrastructure or private sector financing). It is also learning where engagement may be higher risk (for example, social sectors or small enterprise development). There is clear evidence of shifts in the co-financing portfolio to support this.

DFID has learned to be an effective minority shareholder

2.94 DFID has used a range of evidence to shape its relationship with ADB. Through the MAR process, DFID developed a methodology to assess value for money across the multilateral development institutions. It used this to inform its ADF negotiations and policy positions, including the ADF XI replenishment.

2.95 The ADF XI replenishment was informed by a major review by IED of the development effectiveness of ADF operations in the period 2001-10.70 DFID was an active participant in the three replenishment meetings – each of which involved substantive discussion of research and policy papers. This, together with priorities identified in the MAR, was used to inform the ADF XI negotiating strategy. Overall, the ADF XI negotiating strategy appears well informed.

2.96 The UK has learned how to work with ADB as a minority shareholder. It adopts a pragmatic approach to lobbying, selecting issues of importance to the UK. This is either where ADB has shown willingness to reform (e.g. the results agenda), or where there is support from one or more major shareholders (e.g. the Afghanistan funding uplift). Given the limited resources available for shareholder activities, it will need to continue to be pragmatic in deciding on which issues to lobby.

3 Conclusions and Recommendations

Conclusions

DFID as a shareholder

3.1 ADB is reducing poverty across Asia, including in critical countries for the UK. The UK’s 2% capital investment in ADB ($113 million since 1966) represents value for money. Every dollar of this capital investment has yielded on average $22 of ADB lending in Asia.71

3.2 The ADF makes concessional loans and grants to low-income countries. The UK’s proportionately larger contribution to this fund (than its shareholding), reflects its focus on the poorest (£175 million to ADF over the past five years). The recent, large increase in DFID’s contribution to the ADF over the period 2013-16 followed the MAR finding that ADF represents ‘very good value for money’, making a ‘strong’ contribution to UK development objectives.

3.3 The evidence of our review is that DFID has a positive influence on ADB’s strategy, policies and internal reforms. Through the ADF replenishment process, it has promoted a continuing focus on areas such as inclusive growth, gender, climate change and operational effectiveness.

3.4 ADB is not, however, meeting its own targets for the delivery of development outcomes. As a shareholder and contributor of core funding to the ADF, DFID should continue to work with the Bank to help to improve the outcomes of its projects.

DFID as a co-financier

3.5 The UK Government, through DFID and DECC, has also provided $255 million of official co-financing for projects with ADB over the past five years (2007-11). This funding is concentrated in a small number of projects in four countries. The current value of active projects is $489 million plus $21 million technical assistance.

3.6 ADB has strong, well-established expertise in a range of areas, for example, in private sector financing, the power sector and infrastructure. These sectors are essential for Asian growth and complement DFID’s other work.

3.7 The evidence of this review is that DFID engages effectively with ADB at country level in developing country strategies and co-ordinating with other donors. DFID should, however, provide greater support to ADB and recipient governments during implementation, to improve the performance of co-financed projects.

3.8 DFID’s co-financed projects with ADB are delivering substantial results on the ground. Despite this, many have not fully achieved their planned objectives. Delivery problems begin at the design stage, when DFID needs to make sure that it has sufficient staff with the right experience to be fully involved. DFID also needs to be more closely involved in implementation at country level, with a particular focus on programme management and outcome assessment, monitoring overall performance and making sure that agreed changes are implemented. This will help to ensure that project outcomes are delivered.

3.9 Improving project delivery will require additional resource. This could be achieved by re-allocating priorities in DFID country offices, concentrating effort on the sectors that make the greatest contribution to poverty relief and the achievement of the Millennium Development Goals.

3.10 Increasing project impact also requires a strong understanding of project performance and whether the original design is still appropriate. DFID must ensure that it has the management information it needs to assess this. Ideally, this information should come from ADB.

3.11 Careful decisions are also required about when to co-finance with ADB. In some cases, ADB will be chosen by DFID as a partner for practical reasons, not its technical ability. These include: existing relationships with government; a dominant position in a sector; or a willingness to invest in fragile states or innovation.

3.12 Where these other factors influence DFID’s decision to co-finance in areas where ADB has less expertise, for example education, DFID must manage the risks of projects not delivering. This applies particularly in countries where the recipient government, as the executing agency, has low capacity.

Recommendations

3.13 The priority for DFID’s relationship with ADB should be to improve the delivery of outputs and outcomes on a sustained basis. This applies to ADB-financed projects (where DFID has indirect influence as a shareholder) and to co-financed projects (where DFID has direct influence).

3.14 Better outcomes will be achieved by strengthening the project management cycle, in particular: improving design, increasing real-time monitoring and improving evaluation follow-up. This will require DFID both to change its own approach in country offices and to influence change in ADB.

3.15 Better project management will improve the quality of ADB’s project design and the achievement of development outcomes. These actions would also impact positively on the results and value for money of the UK’s co-financed projects.

Recommendation 1: Where DFID is co-financing projects with ADB, it should be clear about the relative contributions of each partner, strengthen its initial risk assessment and resource accordingly and improve its real-time monitoring and evaluation.

3.16 Delivering projects in complex environments needs to be dynamic. Frequent design adjustments are required, based on real-time monitoring. This requires that:

- DFID pays greater attention to the quality of the initial risk assessment on each project, particularly the political context;

- DFID country resources are prioritised to ensure appropriate levels of staffing for co-financed projects – particularly where the choice of ADB as a partner was not based primarily on its technical expertise;

- adequate real-time independent project monitoring and evaluation are in place during implementation, which should identify changes required in the project design or the implementation at critical points; and

- the executing agency implements jointly agreed actions to improve project performance.

Recommendation 2: As a shareholder, DFID should concentrate its influence on improving the impact of ADB and ADF projects, in particular by strengthening project design, implementation and independent evaluation.

3.17 This can be achieved through the UK representative in ADB headquarters:

- influencing the Development Effectiveness Committee to increase the use of evaluation learning;

- ensuring that IED continues to be strengthened through its internal reforms;

- challenging ADB’s senior management to improve project design, implementation and real-time project monitoring and evaluation; and

- making more routine use of feedback from country offices (see Recommendation 3).

Recommendation 3: Ad hoc discussions between DFID country offices, DFID headquarters and the UK representative in ADB headquarters should be formalised in quarterly strategic reviews for the five DFID focus countries where ADB activity is significant.

3.18 We recommend a formal quarterly review between the UK representative at ADB and DFID offices in the five focus countries in Asia (Afghanistan, Bangladesh, India, Nepal and Pakistan) where ADB activity is significant. These should prioritise discussion of progress and risks on co-financed projects and an overview of significant OCR and ADF lending in-country. Reviews should also cover DFID’s plans for the future, including engagement with ADB’s country strategy development and future co-financing opportunities. This will allow DFID to be involved at an earlier stage of planning than is currently the case. Discussions should be based on DFID country office priorities and a clear rationale of the type of projects that should be co-financed with ADB.

3.19 These reviews must be based on a clear understanding of relative strengths of ADB by sector in each country. They will also require up-to-date information on current projects, including disbursements against plans, progress in delivering planned outputs and outcomes and risks to successful completion.

Recommendation 4: DFID needs to ensure that it always has the right information to make choices about when and how to work with ADB. If DFID wishes to use the MAR for this purpose, then future MARs should consider the capabilities of multilateral agencies on the ground across a range of countries, capabilities and project types.

3.20 The current MAR considers an organisation’s behaviours and values, as well as the fit with UK aid priorities. It does not consider in any detail the operational effectiveness of delivery on the ground; as a consequence, it cannot provide assurance on this for individual DFID offices.

Abbreviations

- ADB – Asian Development Bank

- ADF – Asian Development Fund

- ADF X – ADF Ninth Replenishment

- ADF XI – ADF Tenth Replenishment

- CP3 – Climate Public Private Partnership

- CPS – Country Partnership Strategy

- DEC – Development Effectiveness Committee

- DECC – Department of Energy and Climate Change

- DFID – Department for International Development

- ED – Executive Director

- ICAI – Independent Commission for Aid Impact

- IED – Independent Evaluation Department

- IFID – International Financial Institutions Department (of DFID)

- MAR – Multilateral Aid Review

- MOPAN – Multilateral Organisation Performance Assessment Network

- MTR – Mid-Term Review

- NGO – Non-governmental organisation

- OAI – Office of Anti-Corruption and Integrity

- OCR – Ordinary Capital Resources

- PEDP – Primary Education Development Programme, Bangladesh

- PCR – Programme Completion Report

- TACR – Technical Assistance Completion Review

- UPHC – Urban Primary Health Care Programme, Bangladesh

Footnotes

- Strategy 2020: The Long-Term Strategic Framework of the Asian Development Bank 2008–2020, Asian Development Bank, 2008, http://www.adb.org/sites/default/files/Strategy2020-print.pdf.

- There are 40 recipient members (16 low-income countries, 15 blend/lower-middle-income countries and nine middle-income countries), as well as eight donor members from the region and 19 donor members from outside the region.

- 61% of the ADF X replenishment was financed by ADB’s own resources.

- Project loans typically have a maturity of 32 years, including an eight-year grace period; interest is charged at 1% during the grace period, then at 1.5%.

- ADF XI Donors’ Report: Empowering Asia’s Most Vulnerable, Asian Development Bank, May 2012, http://www.adb.org/sites/default/files/adf-xi-donors-report.pdf.

- ADF XI Donors’ Report: Empowering Asia’s Most Vulnerable, Asian Development Bank, May 2012, http://www.adb.org/sites/default/files/adf-xi-donors-report.pdf.

- Data from Asian Development Bank’s Controller’s Department and Strategy and Policy Department.

- 2011 data from ADB Annual Report 2011, Volume 1, Asian Development Bank, 2012, http://www.adb.org/sites/default/files/adb-ar2011-v1.pdf. 2007 data from ADB Annual Report 2010, Asian Development Bank, 2011, www.adb.org/sites/default/files/adb-ar2010-v1.pdf.

- Approvals to India and China were $3 billion and $1.5 billion respectively.

- ADB Annual Report 2011, Volume 1, Asian Development Bank, 2012, http://www.adb.org/sites/default/files/adb-ar2011-v1.pdf.

- See http://www.worldbank.org/depweb/beyond/beyondbw/begbw_06.pdf.

- The Bilateral Aid Review identified eight focus countries where the Asian Development Bank invests: India, Bangladesh, Pakistan, Afghanistan, the Kyrgyz Republic, Myanmar, Nepal and Tajikistan. See Bilateral Aid Review: Technical Report, DFID, 2011, http://www.dfid.gov.uk/Documents/MAR/FINAL_BAR%20TECHNICAL%20REPORT.pdf.

- ADB Annual Report 2011, Asian Development Bank, 2012, http://www.adb.org/sites/default/files/adb-ar2011-v1.pdf#page=125. Co-financing data is at March 2012.

- These are based on figures provided to us by DFID’s International Financial Institutions Department and the Asian Development Bank. ADB’s financial years are calendar years. DFID financial years run from April to March.

- Following a General Capital Increase in April 2009. The General Capital Increase tripled the Bank’s capital base from $55 billion to $165 billion. See ADB Financial Profile 2011, Asian Development Bank, 2011, http://www.adb.org/sites/default/files/pub/2011/financialprofile2011.pdf.

- As of December 2011, see http://www.adb.org/sites/default/files/pub/2012/UKG.pdf.

- The UK next becomes Alternate ED in July 2012 and ED in July 2014.

- The six Board committees are: Audit, Budget Review, Compliance Review, Development Effectiveness, Ethics and Human Resources.

- ADF XI Donors’ Report: Empowering Asia’s Most Vulnerable, Asian Development Bank, May 2012, http://www.adb.org/sites/default/files/adf-xi-donors-report.pdf.

- Multilateral Aid Review, DFID, March 2011, http://www.dfid.gov.uk/Documents/publications1/mar/multilateral_aid_review.pdf. This MAR is focussed on the ADF, but the management process is largely common to both ADB and the ADF.

- To place the UK’s contributions in perspective, total direct co-financing in 2011 was $7.7 billion. See http://www.adb.org/sites/default/files/pub/2012/UKG.pdf.

- This is a grant to increase the availability of finance to the solar sector in India, see http://www.adb.org/site/private-sector-financing/india-solar-generation-guarantee-facility.

- Although ADB manages far fewer trust funds than, for example, the World Bank.

- ADB Strategy 2020, Asian Development Bank, 2008, http://www.adb.org/documents/strategy-2020-working-asia-and-pacific-free-poverty.