The FCDO’s Programme Operating Framework

Executive summary

An operating framework sets out how an organisation delivers its strategic objectives in a way that promotes its corporate culture. Following the merger of the Foreign and Commonwealth Office (FCO) with the Department for International Development (DFID) in September 2020 to form the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO), FCDO launched the Programme Operating Framework (PrOF) managed by FCDO’s Centre for Delivery. FCDO intended the PrOF, which came into force on 1 April 2021, to be a key tool for embedding a common approach to programme management across the new department, coving both aid and non-aid programming.

This rapid review provides an early opportunity for the Independent Commission for Aid Impact (ICAI) to assess the PrOF’s effectiveness in supporting aid delivery across FCDO’s diverse portfolio. It assesses the extent to which FCDO has incorporated good practice into the PrOF and the extent to which the PrOF has been implemented in the new department. The review aims to support learning in the FCDO, as the department works to refine its programme management approach and integrate systems and staff post-merger.

Internal and external volatility and change characterised the wider context in which FCDO developed and implemented the PrOF. FCDO has faced high staff turnover and significant and ongoing aid budget reductions. Global events have placed significant demands on FCDO, including the COVID-19 pandemic, the rapid withdrawal of the UK and its allies from Afghanistan, and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. In the UK, there have been frequent changes in the ministers of state with responsibility for official development assistance (ODA) in the three and a half years before this review commenced in October 2022. While this context added to the challenge of developing and implementing a common operating framework, it also highlights the importance of a constant yet agile approach to programme management for FCDO.

Relevance: Is the PrOF a credible approach for the management of UK aid programmes?

FCDO’s rapid development and deployment of the PrOF is commendable, especially given the significant internal and external challenges facing the department following its creation. It has helped to create stability for FCDO programme staff and has ensured that good programme management practice, developed within the former DFID and former FCO-managed aid programmes, has been retained, in particular the concepts of ‘subsidiarity’ and ‘empowered accountability’. This is the idea that programmes will be more effective if staff closest to the programme’s activities are empowered to make operational decisions within a clear accountability framework.

The PrOF is the right approach to support agile, impact-focused programme delivery across FCDO. It is closely based on DFID’s Smart Rules, centred around a set of principles and mandatory rules, but simplified and tailored to the new department and cross-government standards and priorities. The Smart Rules established a Senior Responsible Owner (SRO) role as the individual responsible for making operational decisions about their programme(s) under the Smart Rules’ empowered accountability model. The PrOF adds two new roles:

- A Portfolio SRO role at the Head of Mission or Director level, which situates the empowered accountability model within a portfolio approach to delivering UK priorities, supporting coherence between FCDO’s programmes and policy initiatives towards common objectives. This is distinct from the programme level SRO, who reports to the Portfolio SRO.

- A new Programme Responsible Owner (PRO) role, reporting to the SRO, helps align the FCDO with other government departments.

In practice, these new roles are not yet well understood, but they have the potential to make FCDO’s ODA and non-ODA programming more effective at delivering strategic objectives.

As the PrOF covers all FCDO programmes, it is necessarily less focused on aid delivery than DFID’s Smart Rules. However, detailed guidance concerning aid delivery is available and referred to in the PrOF. Moreover, a standardised approach is essential for supporting a unified culture and the development of a wider pool of professional programme management staff, operating to consistent, high standards across all FCDO programmes. This has the potential to benefit aid delivery by developing a wider pool of staff with more diverse programme management experience.

While the PrOF’s overall approach is credible, and the principles and rules that form the centre of the PrOF are relatively concise, much of the remainder of the document is not clearly written, making it harder for readers to find and absorb the most important information.

Effectiveness: To what extent has the PrOF’s implementation supported the delivery of UK aid across FCDO’s diverse programmes?

Implemention of the PrOF is not complete. FCDO has made good progress among programme staff for more traditional, large-scale aid programmes, but it has not always been easy to adapt the PrOF to smaller programmes that can be important tools to support rapid, targeted and agile interventions with limited budgets. Centre for Delivery is aware that more work is needed in this area.

Centre for Delivery has also struggled to gain traction with more senior staff who lack clarity about what the PrOF means to them. This has led to inefficiencies in the PrOF’s implementation. The lack of attention at senior level has also contributed to many programme staff feeling undervalued, affecting morale and potentially contributing to the high staff attrition rates, although these issues are also impacted by wider challenges related to the merger and budget reductions. More work is needed to ensure PrOF promotes efficiency for all programmes, especially smaller programmes, those that do not follow the typical programme lifecycle (for example Chevening), and programmes that cut across regions with multiple Portfolio SROs. FCDO’s Centre for Delivery has actively engaged with these programmes when they have come to light, but the challenges of applying the PrOF in such programmes are not yet fully resolved.

Systems integration following the merger is still not complete due to delays in implementing a new finance system. FCDO’s programme management software, AMP, is aligned to the PrOF and easy to use. While AMP contains valuable data on compliance and performance, central monitoring of compliance with the PrOF is limited and still under development. We found high levels of non-compliance in our sample of 44 programmes, including 30% without a complete risk register. Responsibility for compliance is devolved to Heads of Mission, who do not receive or have easy access to relevant compliance metrics. We also found examples of non-compliance with one of the few new rules on assessing climate and environmental risks to support the UK’s climate change commitments.

Learning: How well has the PrOF been adapted since its launch?

Centre for Delivery has updated the PrOF to reflect changes in the business and feedback from staff. Updates occur every six months and changes to date have been evidence-based and approved at the appropriate level. Updates have been relatively minor, as Centre for Delivery has set a high bar for changes to provide stability among programme delivery staff and while the PrOF is being implemented across the organisation.

While Centre for Delivery has consulted with numerous programme staff, much of the internal feedback has been from staff already engaged with Centre for Delivery. It has struggled to obtain representative feedback from across FCDO through annual surveys. There has been no engagement with other donors to learn from their programme management approaches. FCDO has worked to align the PrOF to cross-government standards and good practice set by the Infrastructure and Projects Authority (IPA). According to the IPA, however, FCDO’s engagement with the IPA has been limited compared to other government departments with a large programme budget.

Recommendations

FCDO’s launch of the PrOF within a short time following the FCO-DFID merger is commendable. It has embedded the principle of empowered accountability – important for agile and impact-focused programming – into FCDO’s programme management approach and provided stability for programme management staff during a volatile and challenging period. However, the process of embedding the PrOF is not yet complete. More work is needed to: raise awareness, especially among senior staff; ensure compliance; and make the PrOF more versatile and accessible, especially to those new to its programme management approach.

Recommendation 1

FCDO should set clear targets and timeframes for PrOF awareness and implementation at all levels of FCDO staff within the scope of the PrOF, especially among Heads of Mission and Directors who have portfolio-level responsibility.

Recommendation 2

FCDO should prioritise developing its programme management software’s capability to provide timely

management data on programme compliance, overall portfolio risk profile and performance to programme

staff and Portfolio Senior Responsible Owners, which Centre for Delivery can monitor, and Internal Audit can

access.

Recommendation 3

FCDO should establish a comprehensive three- to five-yearly internal and external consultation process to focus on the PrOF’s clarity, relevance and accessibility, and to incorporate new learning and international good practice for delivering agile, accountable and impact-focused programmes that support the UK’s strategic objectives.

1. Introduction

1.1 An operating framework bridges an organisation’s strategy and its processes. It sets out how an organisation delivers its strategic objectives in a way that promotes its corporate culture and identity. While operating frameworks should be tailored to each organisation, they typically include principles of good governance, risk management, performance management and continuous improvement.

1.2 The UK’s Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO) uses programmes to deliver many of its policy objectives, including for 92% of its £8.2 billion aid spend in 2021. Programmes are time-bound initiatives that follow distinct steps to achieve targeted outcomes. Programme budgets can range from a few thousand pounds to hundreds of millions. They include small-scale country-level projects, as well as humanitarian responses such as the £220 million Humanitarian preparedness and response support to Ukraine 2022 and multi-year, multi-country funds such as the £140 million Building resilience and adaptation to climate extremes and disasters initiative.

1.3 Following the merger of the Foreign and Commonwealth Office (FCO) with the Department for International Development (DFID) in September 2020 to form the FCDO, FCDO launched the Programme Operating Framework (PrOF) which came into force on 1 April 2021. FCDO intended the PrOF to be a key tool for embedding a common approach to programme management across the new department. It provides the basis for how FCDO programmes should be managed to ensure high standards and meet central government expectations.

1.4 This rapid review provides an early opportunity for ICAI to assess the PrOF’s effectiveness in supporting aid delivery across FCDO’s diverse portfolio. It assesses the extent to which FCDO has incorporated good practice into the PrOF and the extent to which it has implemented the PrOF in practice. The review also considers alignment of the PrOF with the Government Functional Standard on project delivery, which sets out rules and guidelines for portfolio, programme and project delivery that apply to all UK government departments.6 The review aims to support learning in the FCDO, as the department works to refine its programme management approach and integrate systems and staff, post-merger.

1.5 Table 1 sets out our review questions. For this report ‘programme’ includes all types of projects and programmes governed by the Government Functional Standard on project delivery.

Table 1: Our review questions

| Review criteria and question | Sub-questions |

|---|---|

| 1. Relevance: Is the PrOF a credible approach for the management of UK aid programmes? | • Does the PrOF content reflect good practice for programme and risk management? • How well suited is the PrOF to FCDO’s context (including its priorities, culture and resources)? • Has the PrOF been reviewed and approved, and promoted and endorsed, by appropriate levels of seniority within FCDO’s governance structure? |

| 2. Effectiveness: To what extent has the PrOF’s implementation supported the delivery of UK aid across FCDO’s diverse programmes? | • How well has FCDO implemented and embedded the PrOF; are training and communications effective and targeted to the right people; is the PrOF understood and used? • To what extent does the PrOF help FCDO programme staff to deliver aid objectives in practice? • How clearly does the PrOF communicate to programme staff what is mandatory and what is guidance? • To what extent does the PrOF enable FCDO programme staff to adjust programmes based on learning or changed circumstances? • How well does the PrOF support a consistent, proportionate and professional approach to programme management across FCDO? |

| 3. Learning: How well has the PrOF been adapted since its launch? | • Are there mechanisms in place to capture learning on how well the PrOF helps staff to take risk-based, value-for-money decisions that are proportionate and appropriate to the size, complexity and degree of risk inherent in a particular project or programme, and in how the PrOF can be improved? • To what extent does the learning process result in meaningful and timely change in the PrOF and/or related training, guidance, culture and communications? How is this balanced with the need for consistency? • Are changes made to the PrOF (if any) based on evidence from operational experience and have they been timely, justified and approved by appropriate levels of seniority? |

2. Methodology

2.1 The COSO framework informed the methodology for this rapid review. While there are no common standards for operating frameworks, the COSO framework provides a comprehensive structure for how organisations can optimise their strategy and performance based on enterprise risk management good practice. This private sector initiative has been deployed in “organisations of all types and sizes around the world to identify risks, manage those risks within a defined risk appetite, and support the achievement of [their] objectives”. It encapsulates a broad perspective of internal controls that include organisational culture and how senior leaders demonstrate a commitment to core values. The COSO framework includes 20 good practices across five pillars, as shown in Figure 1, that should be tailored to an organisation’s context.

Figure 1: Good practices for strategic and performance-enhancing risk management from the COSO framework

Source: Enterprise risk management: Integrating with strategy and performance, COSO, June 2017, p. 4 and 10.

2.2 Our methodology included the following components:

- Annotated bibliography: A brief annotated bibliography, published as a separate document, summarising good practice in programme management.

- Document review: Review of the Programme Operating Framework (PrOF) using the COSO framework as a guide, and of documentation provided by the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO) Centre for Delivery12 relating to the PrOF’s development, implementation and ongoing maintenance.

- Programme sample review: High-level review and compliance checks of 44 aid programmes

selected to include:- Programmes initiated or closed (approximately evenly split) during financial year 2021-22, as the PrOF launched at the beginning of this period, on 1 April 2021.

- Programmes with different budgets including those with budgets more than £40 million, which require additional sign-off under the PrOF, and a sample with budgets less than £1 million.

- A mix of centrally managed and single-country programmes covering diverse geographies and development areas, including rapid onset humanitarian responses.

- Legacy DFID and FCO programmes and programmes established under FCDO.

- Focus groups: Six focus groups with staff members from 20 diverse programmes in our sample. Participants included:

- Senior Responsible Owners (SROs) – the strategic lead for a programme.

- Programme Responsible Owners (PROs) – the day-to-day project managers, advisors and other programme staff.

- Stakeholder interviews: Interviews with:

- Twelve staff involved in the design, implementation and governance of the PrOF.

- Three FCDO Heads of Mission (the UK’s ambassadors and high commissioners).

- Six programme SROs and PROs from our sample.

- A representative of the UK’s Infrastructure and Projects Authority (IPA).

Box 1: Limitations of scope

- PrOF covers both official development assistance (ODA) and non-ODA programmes and some of our findings may be relevant to all types of programmes; however, the Independent Commission for Aid Impact is only mandated to evaluate the effectiveness of ODA so we designed the review for this purpose only.

- PrOF applies only to FCDO. Our review did not assess how other government departments manage aid programmes.

- PrOF does not cover non-programme spend such as internal infrastructure and information technology programmes. Such spend was therefore outside the scope of this review.

3. Background

3.1 The Programme Operating Framework (PrOF) applies to all staff managing or advising on Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO) programmes, and decision-makers for approving and overseeing those programmes. It is used for all FCDO policy programmes, whether UK aid funded or not, as well as for cross-government funds managed by FCDO.

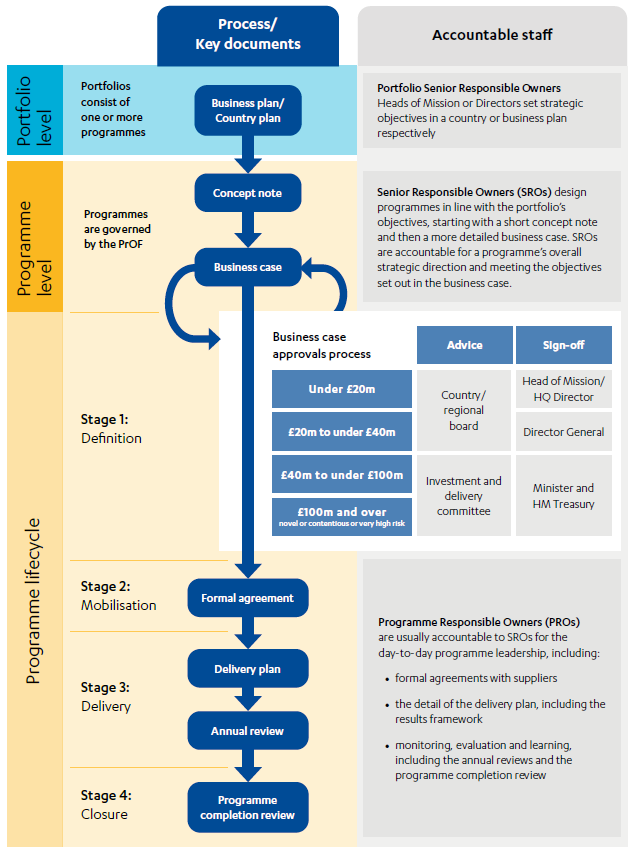

3.2 The framework is structured around the FCDO programme management cycle. Figure 2 shows key aspects of the programme cycle and approval levels required to initiative programmes according to the PrOF. The PrOF sets out principles, rules, roles and responsibilities, governance, guidance and best practice. Its intention is to empower staff to take risk-based approaches to programme delivery, using their own judgement and contextual expertise within a set of mandatory rules and process milestones.

Figure 2: Programme management cycle and governance

Source: FCDO Programme Operating Framework, Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office, updated November 2022, p. 12-14.

3.3 The PrOF provides a set of rules and principles which staff must apply in delivering FCDO’s policy programmes (see Box 2); 97% of these programmes qualify as official development assistance (ODA) spend. The PrOF is intended as a ‘one-stop framework’ for programme delivery – a set of parameters within which all teams should work to drive programme management excellence. It is intended to empower staff to adapt their approach to the diverse needs of the FCDO portfolio.

Box 2: PrOF structure

- Introduction – including what the PrOF is for and how to use it.

- Principles – including ten programme principles (see Annex 1) that underpin programme delivery.

- Ruleset – including the 29 rules (see Annex 1) followed by a one-page explanation of each rule.

- Roles and responsibilities – covering the key roles for programme delivery including the Senior Responsible Officer (SRO), the Programme Responsible Officer (PRO, the Portfolio SRO and the Development Director.

- Lifecycle – including the four stages of a programme lifecycle (definition, mobilisation, delivery and closure) and the controls at each stage (see Figure 2).

- Governance – including FCDO’s governance structures and the approval limits, such as for business cases (see Figure 2).

The PrOF is supported by more than 100 guides providing further information on specific aspects of programme management or types of programme (see the full list in Annex 2). Guides are non-mandatory but designed to incorporate good practice into programming and provide guidance on how rules can be implemented in practice.

Context and the development of the PrOF

3.4 FCDO developed the PrOF in response to the merger of the Foreign and Commonwealth Office (FCO) with the Department for International Development (DFID) in September 2020. The framework aimed to draw on established practices and incremental learning in legacy frameworks for project and programme management, to provide a tool to support high standards of delivery and risk management in the new department. It also aimed to bring together the strengths of the operating frameworks used by FCDO’s predecessor departments – DFID’s Smart Rules and FCO’s Policy Portfolio Framework – alongside new additions, intending to make the PrOF “better than both”.

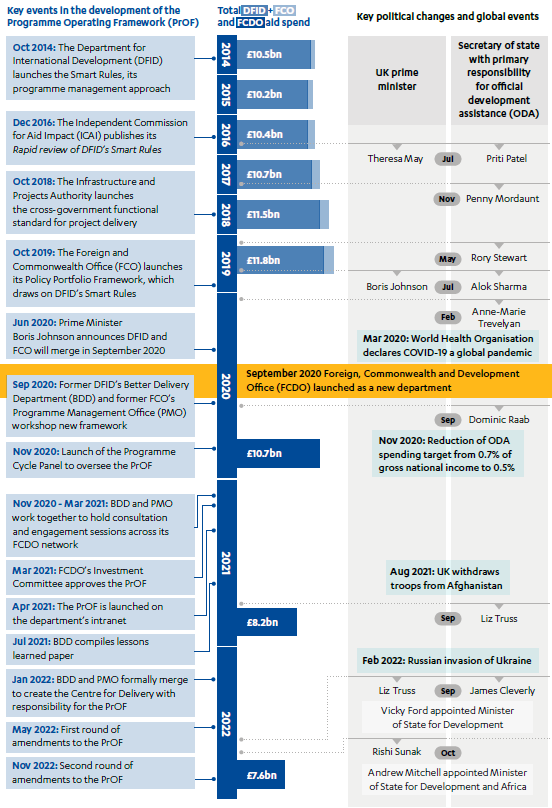

3.5 The wider context in which the PrOF was developed and implemented was also characterised by volatility and change affecting FCDO (see Figure 3). Following the merger, many roles have changed and FCDO has faced high staff attrition rates and understaffing in many areas. Whereas DFID developed its Smart Rules in the context of increasing aid budgets, FCDO developed and is implementing the PrOF during significant and ongoing aid budget reductions. Global events during this period also placed significant demands on FCDO, including the COVID-19 pandemic, the rapid withdrawal of the UK and its allies from Afghanistan, and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. In the UK, political changes led to a high turnover of ministers with responsibility for ODA in the last four years. While this context added to the challenge of developing and implementing a common operating framework, it also highlights the importance of a constant yet agile approach to programme management for FCDO.

Figure 3: PrOF development timeline and context

Programme management in the UK civil service

3.6 Project delivery (which covers both projects and programmes in the same way that PrOF, and this report, uses the term ‘programmes’ to include both projects and programmes) is a distinct civil service profession and one of 12 government ‘functions’. Functions have common standards, networks and career development support across government. The Infrastructure and Projects Authority (IPA), a centre of expertise that reports into the Cabinet Office and HM Treasury, oversees the project delivery profession and is responsible for developing project delivery capacity and capability in all government departments. It provides resources and guidance for programme delivery staff and links to a range of resources including Treasury guidance and further resources and training.

3.7 IPA is also responsible for the Government Functional Standard on project delivery. This sets “expectations for the direction and management of portfolios, programmes and projects ensuring value for money and the successful and timely delivery of government policy and business objectives”. The standards are mandatory across all government departments.

The PrOF principles and rules

3.8 The PrOF centres around ten overarching principles and 29 mandatory rules. The rules are split across six

categories:

- Seven operating framework and strategic alignment rules

- Six programme design and approval rules

- Four mobilisation and procurement rules

- Five programme management and delivery rules

- Six financial management rules

- One programme closure rule.

We have provided the PrOF principles and rules in Annex 1 of this report for reference, or they are in sections 2 and 3 of the publicly available PrOF document.

Findings

4.1 In this section, we assess the relevance and effectiveness of the Programme Operating Framework (PrOF) for Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO) aid programming, and FCDO’s approach to learning to improve the PrOF following its implementation in April 2021.

Relevance: Is the PrOF a credible approach for the management of UK aid programmes?

The PrOF maintains important aid programme management practices developed by the former Department for International Development (DFID)

4.2 DFID’s Better Delivery Department initiated and led the development of the PrOF, in partnership with the Foreign and Commonwealth Office’s (FCO) Portfolio Management Office, after the merger between DFID and FCO was announced. The Better Delivery Department managed DFID’s Smart Rules, which had been in place since 2014.

4.3 The Smart Rules had helped to streamline official development assistance (ODA) programme management within DFID. The Rules replaced 200 prescriptive compliance steps with 37 mandatory rules supported by ten principles and a comprehensive set of non-mandatory Smart Guides. The Smart Rules were principle-based and founded on the concept of ‘subsidiarity’ – the idea that programmes will be more effective if operational decisions can be taken close to programme activities. This ‘empowered accountability’ model enabled in-country staff with the closest knowledge of the context to take decisions about how programmes and associated risks should be managed, within an overarching framework.

4.4 ICAI supports efforts to streamline aid delivery, enable adaptive programming and continuous learning, and empower programme delivery staff to decide how to achieve aid outcomes within clear accountability structures. Following a rapid review of DFID’s Smart Rules in December 2014, ICAI commended the Smart Rules’ principles-based, empowered accountability approach while recommending DFID do more to drive the cultural changes of the Smart Rules across the organisation, supported by senior leadership. The Smart Rules subsequently became central to DFID’s culture and approach.

4.5 While DFID’s main activity was programme management – increasingly through large-scale, outsourced programmes – FCO programmes tended to be smaller and less prominent. FCO had only launched its Policy Portfolio Framework in October 2019, shortly after the Government Functional Standard on project management came into effect. FCO’s framework was not fully embedded by the time of the merger, having only existed for a year, and was not widely known by former FCO staff. DFID’s Better Delivery Department engaged with their counterparts in FCO to form a working group to develop the PrOF and, in January 2022, formed the Centre for Delivery in FCDO (see Box 3).

Box 3: The role of Centre for Delivery

Centre for Delivery informed us that its role is to inspire, empower and equip FCDO staff to achieve real world impact by building a more capable organisation that embraces evidence, learning, innovation, creativity, empowered accountability, and informed decision-making. Centre for Delivery is the home of the PrOF and its Head of Department chairs the Programme Cycle Panel, the governing body that owns the PrOF rules and approves any changes.

4.6 The PrOF adopted the Smart Rules’ principles-based, empowered accountability approach. This is well suited to support agile, adaptive programming and reducing bureaucracy in aid delivery across a diverse portfolio within clear governance and accountability structures.

DFID’s Smart Rules have been simplified and updated and valuable new guidance added

4.7 While it draws on aspects of the FCO’s Policy Portfolio Framework, the PrOF is primarily a restructured and updated version of DFID’s Smart Rules. It has reduced the number of rules from 37 to 29 and reduced many of the rules’ length and complexity. This makes the PrOF rules less cumbersome than the Smart Rules and more relevant to aid delivery than the Policy Portfolio Framework.

4.8 Each rule is supplemented by a ‘one-pager’ explanation of the rule, which includes: ‘why’ the rule is needed; ‘who’ is responsible for what; and ‘how’ programme teams can comply. Much of the content removed from the Smart Rules is incorporated into these PrOF one-pagers. For example, DFID’s Smart Rules had seven separate rules covering procurement, which were replaced by one higher-level rule in the PrOF with much of the old detail moved to the one-pagers.

4.9 The one-pagers explain how the rules link to the overarching principles and any special circumstances such as for rapid onset humanitarian responses and working with multilaterals. One-pagers also link to further guidance. There are more than 100 additional non-mandatory ‘PrOF Guides’ which programme staff can refer to according to their or their programme’s needs and context (see Annex 2). These build on the former DFID Smart Guides.

4.10 Programme staff advised us that the one-pagers helped them to understand how to comply with the rules in their work.

The PrOF covers key aspects of good programme and risk management practices

4.11 Our assessment of the PrOF against the COSO22 framework shows that there is good coverage of the key COSO areas. The PrOF itself covers each of the five pillars and all 20 COSO elements to some degree. Certain aspects of these elements are outside the remit of the PrOF but are captured in the systems and governance structures around the PrOF.

4.12 Limited public information is available about other major aid agencies’ operating frameworks, and FCDO’s publication of the PrOF demonstrates leadership in transparency and collaboration. Of relevant information that is publicly available, such as USAID’s Programme Cycle Operating Policy, there was nothing to suggest that the PrOF was substantively lacking good practice and some areas where the PrOF had advantages, such as incorporating examples of real-life applications. However, FCDO had not engaged with other donors as part of the PrOF’s development. As publicly available information is very limited, we would like to have seen efforts by FCDO to engage with other donors to ensure as much learning as possible from other donors’ experiences informed the PrOF.

The PrOF reflects the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office’s priorities and structure

4.13 While Centre for Delivery has updated most of the rules in some way, the most substantive changes to the PrOF compared to the Smart Rules reflect the differences between FCDO and DFID, and alignment with government priorities. FCDO only added three completely new rules, which reflect the new department’s context and priorities. These are:

- PrOF Rule 2: All spend reported as official development assistance (ODA) must meet the agreed international definition of aid.

- PrOF Rule 3: All programmes and projects must align with FCDO and government policy priorities and business objectives.

- PrOF Rule 5: All new programmes (and the projects, interventions or events within them) must align with the Paris Agreement – an international treaty on climate change – and assess climate and environmental impact and risks, taking steps to ensure that no environmental harm is done. Any International Climate Finance (ICF) programmes must identify and record ICF spend and results.

4.14 Rule 2 is needed because the PrOF covers both ODA and non-ODA programmes within FCDO, whereas DFID’s Smart Rules only covered ODA programming. Rule 3 reflects the structure of the FCDO where aid delivery is included in portfolios overseen by Heads of Mission – the UK’s ambassadors and high commissioners – who are responsible for delivering against a country strategy. Rule 5 reflects the UK’s commitment to the Paris Agreement, a legally binding international treaty on climate change which came into force in November 2016 and is relevant for both ODA and non-ODA programmes.

4.15 Centre for Delivery expanded several rules; notably, while the Smart Rules required gender equality to be considered for every programme, Rule 10 of the PrOF also covers disability inclusion and people with protected characteristics.

- PrOF Rule 10: All programmes (and policies) must consider and provide evidence on how their

interventions will impact on gender equality, disability inclusion and those with protected characteristics.

4.16 The PrOF also contains updated roles and responsibilities that align more closely with those across government. This included establishing the Head of Mission or Director as the ‘Portfolio Senior Responsible Owner’, with overall responsibility for all the programmes within their portfolio, which has the potential to support coherence between FCDO’s programmes and policy towards common objectives. In addition, there are two roles that are mandatory for every programme – the Senior Responsible Owner (SRO) and the Programme Responsible Owner (PRO) (see Box 4). The PRO is a new role added in the PrOF, similar to the former SRO role in DFID’s Smart Rules. The SRO role in the PrOF now has greater responsibility.

Box 4: Accountabilities and responsibilities of SROs and PROs

The Portfolio Senior Responsible Owner (Portfolio SRO) has overall accountability for the entire portfolio of activity in a country or central directorate, including programmes. The Head of Mission holds this role for a country portfolio, and a Director for a central portfolio managed from the UK.

The Senior Responsible Owner (SRO) is accountable for a programme meeting its objectives, delivering the required outcomes and contributing as expected to the portfolio-level outcomes set out in delivery frameworks, country or directorate business plans and FCDO as a whole. The SRO for a programme is responsible for strategic oversight of the programme(s) they are accountable for, holding the programme team to account in ensuring effective delivery, and providing overall leadership, decisions and direction.

The Programme Responsible Owner (PRO) is accountable for driving the delivery of programme outcomes daily within agreed time, cost and quality constraints. The PRO is responsible for leadership within the programme team. The role combines technical, programme management and relationship management responsibilities. Different skills are likely required at different stages of a programme, so an advisor, a programme manager or another member of the programme team may fill the role.

Source: FCDO Programme Operating Framework, Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office, updated November 2022, p. 67-75.

The PrOF was rapidly developed as a minimum viable product to provide stability during the process of integration following the merger decision

4.17 Centre for Delivery developed the PrOF which was launched in April 2021, the start of the first financial year since the creation of FCDO in September 2020. The team engaged with more than 1,500 staff during this process over seven months. The panel overseeing DFID’s Smart Rules, known as the Programme Cycle Committee, became the Programme Cycle Panel in FCDO. The panel oversaw the PrOF’s development, and it reviews and approves all changes to the PrOF. The PrOF was signed-off by FCDO’s Investment and Delivery Committee, chaired by the Director General for Finance and Corporate, in March 2021 in time for the April 2021 launch. Centre for Delivery described the PrOF as a minimum viable product to be adapted after piloting. We discuss this further in the Learning section below.

4.18 The Audit and Risk Committee did not formally review and sign off the PrOF, which we consider would have been good practice. However, as part of FCDO’s work on reducing bureaucracy, the Audit and Risk Committee was briefed on the PrOF and, according to Centre for Delivery, the committee’s chair and a non-executive committee member closely scrutinised the PrOF.

4.19 The rapid creation of the PrOF helped to provide stability for programme delivery staff during a time of substantial disruption due to the merger and external events. It ensured programme management good practice was adopted into the new department and created a common language for former DFID and FCO staff.

Covering both ODA and non-ODA programmes has advantages and disadvantages

4.20 The PrOF covers all programme management in FCDO and, apart from Rule 2, all rules apply to all programmes, whether or not they are funded by ODA. From an aid effectiveness perspective, the broader coverage means less focus on aid delivery than with the Smart Rules, which focused specifically on aid programming. It also potentially makes it more difficult to make the case that other aid-spending departments should adopt PrOF practices as these are not ODA-specific. While this review did not directly assess other departments’ approaches, previous ICAI reviews have identified varying degrees of maturity in how other departments manage aid programmes, and several staff, including a Head of Mission, to whom we spoke for this review, raised concerns about lower standards of programme delivery in non-FCDO managed programmes.

4.21 Centre for Delivery saw a generalised framework as an important way to support the merger by creating a common approach and culture across the department, to enable mobility of programme management staff across all types of programme in the new department, and to raise standards of former FCO programme management where the operating framework was not yet embedded.

The PrOF has not been fully adapted to the FCDO landscape of reducing aid budgets and smaller programmes

4.22 Although there is some loss of focus on ODA, the PrOF is still more familiar to those who were used to DFID’s Smart Rules and more applicable to traditional, large-scale aid programmes. The language and non-prescriptive nature of the Smart Rules provide continuity for experienced development staff who operated under DFID’s decentralised model, yet can be disconcerting for staff new to aid programming or those more familiar with the former FCO’s Programme Policy Framework. In addition, given the UK’s reduced aid budget, some staff are concerned that the PrOF has not fully adapted to suit smaller programmes that may be an important tool to support rapid, targeted and agile interventions with limited budgets. ICAI’s review of ‘The UK’s approach to democracy and human rights’ also identified the potential value of small programmes and the need for a leaner process to design and approve them.

4.23 In our programme sample, we found staff feeling obliged to undertake unnecessary steps to get smaller programmes or partnerships approved, adversely impacting the department’s agility. We learned of staff conducting onerous due diligence assessments for programme spend in the low thousands. As one Head of Mission said:

“We do not currently have the proper tools in our toolkit for small amounts of money. We are no longer in a world where programmes are likely to be £100 million, so the language of ‘be proportionate’ is not enough.”

4.24 A specific example of this challenge came from one of our focus groups:

“Right now, we’ve had a hurricane hit so we are launching a small programme of £60,000 and navigating PrOF rules is very difficult, especially in humanitarian programmes.”

“[PrOF] is not fit-for-purpose for short-lived interventions. It may work when you have existing programmes and due diligence done, but when starting from scratch on something small it’s very hard to navigate what is proportionate and what is not.”

4.25 Centre for Delivery is working to address this and published a PrOF Guide on proportionality in May 2022. However, much of the guidance draws out exceptions that are already in the PrOF. In other cases, guidance on proportionality will take time and experience to implement effectively. For example, the guidance suggests “[w]hen considering a very small funding intervention, consider if there is a larger programme which would provide a good fit for the funding to sit under. This will ensure only one concept note (where relevant), one business case, one annual review is required.” In principle, this may be a pragmatic approach but, if poorly applied, could lead to contrived or incoherent overarching programmes.

The PrOF document is not clearly written and risks distracting from the important content

4.26 While the PrOF is a credible approach for aid delivery in FCDO based on learning and good practice (albeit with challenges such as with small programmes that are still being worked through), the wider document is daunting, especially for staff new to this style of programme management.

4.27 All sections of the PrOF (see Box 2 for an overview of each) would benefit from thorough proofreading, albeit the principles and rules (in Sections 2 and 3 respectively) are relatively concise and helpful. The one-pagers in Section 3 contain useful practical information, examples and links, although the ‘why’, ‘who’ and ‘how’ structure is sometimes muddled. Section 4, on roles and responsibilities, also generally contains relevant information.

4.28 Sections 1, 5 and 6, however, are often repetitive. They include several diagrams that are overly complex or unnecessary. Large parts of these sections are either unnecessary in the PrOF itself and could be moved to guidance documents, or be deleted. The consequence is that the PrOF is over 100 pages long (twice the length of the Government Functional Standard on project delivery) and it is difficult for readers to find and absorb the most important information.

4.29 FCDO has published a summary document which is more succinctly written and provides a useful introduction, but it is not a substitute for the important detail in the PrOF that programme staff and more senior staff in the chain of command need to know.

4.30 Other cross-government standards and guidance, including the Government Functional Standard on project delivery, contain a key that clearly defines terminology (see Box 5). This is missing from the PrOF.

Box 5: Excerpt from the Government Functional Standard on Programme Delivery

| Term | Intention |

|---|---|

| shall | denotes a requirement: a mandatory element |

| should | denotes a requirement: an advisory element |

| may | denotes approval |

| might | denotes a possibility |

| can | denotes both capability and possibility |

| is/are | denotes a description |

Source: Government Functional Standard GovS 002: Project delivery, Infrastructure and Projects Authority, 2021, p. 2.

4.31 Several of the rules, which are supposed to be mandatory, use ‘should’ rather than ‘shall’ or ‘must’. Rule 7 states “[a]ll FCDO programmes and projects should be as transparent as possible”, implying this is not mandatory; and Rule 9 states that material business cases “should be formalised and approved”. Other parts of the PrOF document use language that could introduce ambiguity about what is and is not required.

- PrOF Rule 7: All FCDO programmes and projects should be as transparent as possible with taxpayers, our partners, host countries and programme constituents (beneficiaries). Programme documents and decisions must be saved correctly for publication. Sensitive information must be treated appropriately.

- PrOF Rule 9: All programmes must be appropriately designed and have a suitably approved [business case] in place prior to the start date (and for the full duration), using the [business case] template. Material changes and extensions to this design should be formalised and approved in a [business case] addendum. Prior [HM Treasury] approval is required for any announcements involving spend if related to a business case or a package of business cases, yet to be developed, totalling [£40 million] or above in any one year.

Effectiveness: To what extent has the PrOF’s implementation supported the delivery of UK aid across FCDO’s diverse programmes?

The PrOF launch was low key and there are examples of internal support teams giving conflicting advice

4.32 Centre for Delivery chose a ‘soft launch’ for the PrOF, in part due to the other significant changes and events placing demands on FCDO staff during the period. This meant that Centre for Delivery communicated the PrOF’s introduction through its networks of known programme managers and through internal FCDO communications platforms. It supported staff by addressing direct queries and by holding drop-in clinics. However, there was no high-profile launch across the department or an engagement campaign to promote the new rules and principles to ensure they reached all staff with programme responsibilities. It has also meant that Centre for Delivery has focused on engaging and supporting staff to understand the PrOF rather than on compliance. During our review, Centre for Delivery established important activities to increase focus on compliance (see paragraphs 4.39 to 4.43).

4.33 This understated roll-out resulted in some programme leads being unaware of their immediate obligations under the PrOF. Furthermore, some programme staff received conflicting or incorrect advice from internal support functions who were unfamiliar with the correct guidance (see Box 6). In particular, many former FCO programme staff were not in Centre for Delivery’s communication networks as FCO did not have a comprehensive list of its programme staff before the merger. This also indicates that corporate functions are not sufficiently engaged with the PrOF.

Box 6: The Chevening Programme case study

The Chevening Scholarship Programme is an ODA-funded, legacy FCO programme that sponsors individuals from around the world to study at UK universities. Chevening scholars are required to return to their country of origin following their studies so they can use their skills to contribute to the development of their home countries. It is, therefore, both a development and soft-power approach to spending UK aid.

The Chevening team was aware of the PrOF but not of its mandatory nature. Due to the light-touch communications, the length of the PrOF document, and their involvement in the evacuation of Afghan fellows in August 2021, the Chevening team did not prioritise applying the PrOF for the first year after the PrOF launched. In March 2022, when renewing a contract with a delivery partner, Chevening staff sought advice from both ex-DFID and ex-FCO commercial and procurement teams, which are still not fully integrated, on how to proceed with the contract renewal. The team later learned that the advice it had received was incorrect due to confusion over the programme’s status under the PrOF. This resulted in delays and duplicated effort, as the team had to repeat the process.

The Chevening programme has existed since 1983 and is a flagship part of UK foreign policy that is periodically reapproved by ministers. It is, therefore, not a natural fit with the typical programme lifecycle on which the PrOF is based. Mandatory PrOF requirements, such as the existence of a concept note for each programme, do not fit Chevening’s model, and Centre for Delivery and Chevening teams had to negotiate a way forward. Both parties described this as a ‘heavy lift’.

PrOF training is available but not mandated, and uptake is low

4.34 The department’s Global Learning Opportunities (GLO) platform provides programme management training. Five of the six main categories had been updated in line with the PrOF at the time of writing (‘Programme cycle management’, ‘Risk management’, ‘Mandatory safeguarding’, ‘Commercial’, and ‘Monitor, learn and adapt’) with the sixth category (‘Financial management’) due to be updated by June 2023. The training is online only and not mandatory, even for programme staff, except for the ‘Sexual exploitation and abuse and harassment (SEAH)’ modules, which are mandatory for all FCDO staff.

4.35 FCDO still cannot determine the total number of staff who need to understand the PrOF. FCDO’s programme management system (discussed in paragraphs 4.38 to 4.40) lists just under 2,000 programme staff, but the PrOF is directed at a much higher number of people as many legacy FCO programmes are not yet recorded on this system. Centre for Delivery noted that it is difficult to determine precise numbers, as the level of involvement of many staff in programmes is constantly shifting. It estimates there are around 3,500 for whom the PrOF is relevant, including Heads of Mission and Directors and programme staff including SROs and PROs. Even taking the known staff, uptake on the non-mandatory GLO training is low, as shown in Table 2. Centre for Delivery reports engagement on its broader programme management support to be higher, at around 900 staff in 2022-23. However, many programme staff from our sample reported they had not completed available training since the PrOF had been implemented, nor had they generally received encouragement or pressure from their managers to do so. Of the programme staff we spoke to in our focus groups, only half had taken the training. One of the country offices had mandated training for its SROs and PROs.

Table 2: Top 20 PrOF-related online training modules, completed from April 2021 to January 2023

| Online course title | No. of staff that have completed the course | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Part 1: What is sexual exploitation and abuse and harassment (SEAH)?* | 10,363 |

| 2 | Part 2: SEAH - engaging with partner organisations* | 9,438 |

| 3 | Safeguarding overview video (3 minutes)** | 7,362 |

| 4 | Manage safeguarding against SEAH in programmes | 379 |

| 5 | Principles of programme cycle management | 365 |

| 6 | Capability framework for delivering international programmes (CF-DIP) | 216 |

| 7 | Fundamentals of risk | 187 |

| 8 | Approaches to design | 177 |

| 9 | Concept note | 147 |

| 10 | Business case | 133 |

| 11 | Financial governance | 132 |

| 12 | Approaches to design (update) | 131 |

| 13 | Value for money in programmes | 102 |

| 14 | Programme closure | 99 |

| 15 | Value for money | 96 |

| 16 | Financial planning: budgeting | 91 |

| 17 | Approvals process for programmes and contracts | 90 |

| 18 | Identifying and articulating risks | 89 |

| 19 | Delivery plans | 86 |

| 20 | Business case extensions and amendments | 82 |

*Mandatory training for all FCDO staff members **Linked to the mandatory training

4.36 Centre for Delivery designed the ‘Capability Framework for Delivering International Programmes (CF-DIP)’ to support staff using the PrOF along with associated training (item 6 in Table 2). It sets out the skills, knowledge and competencies required by staff to deliver on the expectations of the PrOF at foundation, practitioner and expert levels. Centre for Delivery aligned this to the Infrastructure and Projects Authority’s (IPA) project delivery profession, thereby supporting career opportunities across the UK civil service. This has the potential to support and incentivise staff to build their programme management skills within FCDO, thereby embedding the PrOF across the organisation. However, not all programme staff we consulted with were aware of it, and few were aware of how it related to the IPA project delivery profession or to them personally.

4.37 IPA has developed a Government Project Delivery Accreditation which provides an industry-aligned standard for project delivery professionals. It supports the development of project (and programme) delivery capability across government by providing a deeper level of understanding, assessment and validation of knowledge, skills and experience. Following recent pilots, FCDO aims to launch the accreditation process in summer 2023. This process will provide staff with a pathway towards accreditation that will include an assessment against competencies, completion of external learning, online training modules and continuing professional development requirements. This should help increase staff awareness and understanding of the competencies and skills expected of programme managers with linked learning to support any development. Depending on how the launch is delivered, it may also help to raise the profile and understanding of the importance of programme management.

FCDO’s programme management software is user-friendly and aligned to the PrOF, but not fully developed to support compliance

4.38 FCDO adopted DFID’s programme management software, AMP (originally DFID’s Aid Management Platform) to manage legacy DFID aid programmes and, increasingly, for FCDO’s programmes regardless of whether they include aid funding. The migration of former FCO programmes, including its legacy ODA programmes, onto AMP is ongoing. We found the AMP information management system to be well-structured and easy to navigate, and aligned to PrOF requirements. Although the use of AMP is not explicitly required in Rule 7 (below) on transparency, because non-ODA programmes are not yet required to use AMP, the rule requires that staff must correctly save programme documents and decisions. In practice, for aid programmes, the guidance makes it clear that this means saving them to AMP.

- PrOF Rule 7: All FCDO programmes and projects should be as transparent as possible with taxpayers, our partners, host countries and programme constituents (beneficiaries). Programme documents and decisions must be saved correctly for publication. Sensitive information must be treated appropriately.

4.39 FCDO systems have some features that support compliance, such as automatic publication of key documents on AMP to the public domain on the DevTracker website. This helps to meet the key aspect of Rule 7 in ensuring all FCDO programmes are as transparent as possible. Some parameters must also be completed before others can be initiated. For example, programmes without a business case or named SRO cannot proceed to delivery. At present, however, platform pathways do not always flag areas of non-compliance with the PrOF or provide guidance on how to comply in relevant sections, such as when completing risk registers and risk appetite.

4.40 Centre for Delivery informed us that it plans to develop this aspect of AMP, but this was on hold while AMP is being integrated with FCDO’s new finance system, HERA. Implementation of the FCDO-wide finance system has been more challenging than anticipated and is still not integrated with AMP two and a half years after the merger.

Programmes are not fully compliant with the PrOF and compliance is not systematically reported on or enforced

4.41 There is no central enforcement of programmes’ compliance with the PrOF. Compliance for the PrOF is aligned to the line management structure. This means that Heads of Mission and Directors are accountable for compliance with the PrOF. Centre for Delivery is not responsible for enforcement but it prioritises providing support to staff to understand and apply the PrOF. Centre for Delivery is, however, increasingly looking at how to support compliance by providing management information to oversight boards and Heads of Mission and Directors. It is working to improve the range of management information available. Some of this is currently available through AMP, whereas other key information is collated manually, such as time to approve business cases. Currently, however, Heads of Mission and Directors are not widely engaging with the compliance information provided to them. Of the three Heads of Mission we spoke to, one said they had not heard of the PrOF until we contacted them to discuss it. This Head of Mission told us that while they were confident in their programme staff’s capabilities and ability to escalate any issues as needed, and they did not have direct visibility of compliance of programmes within their portfolio.

4.42 Centre for Delivery has made efforts to engage at the Head of Mission and Director level, including collating key performance data on programme management such as: training completion levels among SROs and PROs; time from concept notes to programme implementation; risk register compliance and risk levels compared to appetite; and programme scores. We saw an example of a report prepared by Centre for Delivery to one region’s Heads of Mission aiming to engage them, but this approach requires significant effort and is not easily scalable with limited resources. During our review, Centre for Delivery also identified that, based on AMP data:

- 45 Annual Reviews were overdue;

- 42% of programmes have not updated their risk registers in the last three months, which is the minimum expectation; and

- only 69% of SROs and 55% of PROs have completed programme leadership induction training for roles that sees them empowered to oversee large volumes of UK funds.

4.43 Centre for Delivery provided this and other performance data to the Investment and Delivery Committee which discussed concerns around PrOF compliance and agreed that the Directors General of Corporate and Finance and of Humanitarian and Development would write to all FCDO Heads of Mission and Directors to emphasise their responsibilities in ensuring compliance with the PrOF and the training and support available. In April 2023 the Directors General followed this up with formal communications to Heads of Mission and Directors about their accountabilities and responsibilities as Portfolio SROs. The issue was also discussed in the February 2023 Management Board. The Management Board and Investment and Delivery Committee committed to reviewing adherence to the PrOF by June 2023.

4.44 At the programme delivery level, all programme staff from our sample were familiar with the PrOF and said they use it regularly as a guide to managing their programmes. However, when we conducted checks of compliance on AMP and the public DevTracker website, we found non-compliance in our sample of 44 programmes (see Table 3).

Table 3: Compliance levels with mandatory elements of the PrOF from the programme sample

| AMP checks | DevTracker checks | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Compliance area | SRO named | PRO named | Risk register completed for all mandatory risk areas | Live on DevTracker | Business case uploaded | Results framework uploaded |

| Applicable rule(s) | Rule 4 | Rule 4 | Rules 6 and 18 | Rule 7 | Rules 7 and 9 | Rules 7 and 27 |

| Compliant | 85% | 56% | 70% | 91% | 74% | 58% |

| Non-compliant | 15% | 44% | 30% | 9% | 26% | 42% |

4.45 The elements of the PrOF selected for our compliance checks are important for aid effectiveness, as outlined below in relation to the rules indicated.

- PrOF Rule 4: All programmes must have a named Senior Responsible Owner (SRO) and Programme Responsible Owner (PRO).

4.46 In our programme sample, 15% did not have a named SRO on AMP, as required by Rule 4. SROs are accountable for a programme meeting its objectives and delivering the required outcomes. They are responsible for the strategic oversight and direction of the programme, including management of risks and upholding transparency. If the SRO role was assigned in practice but not logged in AMP, this means a key governance requirement is not visible on the system. A high turnover of SROs can adversely affect programme outcomes and Centre for Delivery cannot easily monitor this or communicate key messages without knowledge of all the key programme staff. Heads of Mission and Directors are responsible for ensuring appropriate SROs and PROs are assigned to programmes in their portfolios.

4.47 Recording risks on central systems is key for senior management’s understanding of risk across a portfolio and necessary to comply with Rule 18 whose guidance states that, for programmes on AMP, “a programme specific risk appetite for each of the seven risk categories must be documented and an AMP risk register must be completed on programme approval and updated regularly”. The guidance states that this “supports much stronger portfolio-level data, enabling better oversight and decision-making by senior leadership”. However, 30% did not have risks properly recorded or were missing mandatory fields such as sexual exploitation and abuse and harassment (SEAH) risks. Ensuring a clear understanding of programme risks and risk appetite is the responsibility of the SRO.

- PrOF Rule 6: Programmatic decisions (including payments and commitments) must only be taken within delegated budget and approved levels of individual authority and in line with the agreed risk appetite. Decisions going beyond these limits and risks which exceed appetite must be escalated to the appropriate level.

4.48 There was also some confusion about how to comply with Rule 6 when setting out risk appetite. PrOF guidance for the rule indicates that the risk appetite must be set for “each of FCDO’s risk categories”, yet some programmes considered the public service delivery and operations category not applicable to their programmes. This is defined by the PrOF as “risk arising from weaknesses in the delivery of consular services or the delivery of internal operations which support our core business and wider [government], including security, legal, technology and information and property risks, impacting delivery, our people and British citizens”. This highlighted an ambiguity in how this rule should be applied in practice.

4.49 Transparency is one of the ten guiding principles of the PrOF and is central to FCDO’s ability to be accountable to “taxpayers, partners and beneficiaries”. However, not all mandatory programme documentation was published on the UK government’s public DevTracker website which is how aid programmes should comply with Rule 7. ICAI previously highlighted concerns that UK government’s previously standard-setting record on this had diminished since the merger in its October 2022 rapid review Transparency in UK aid which reiterated the importance of upholding high standards in this area. Ensuring documentation is managed according to the PrOF is usually the responsibility of the PRO.

- PrOF Rule 5: All new programmes (and the projects, interventions or events within them) must align with the Paris Agreement – an international treaty on climate change – and assess climate and environmental impact and risks, taking steps to ensure that no environmental harm is done. Any International Climate Finance (ICF) programmes must identify and record ICF spend and results.

4.50 A closer review of programme documentation identified other areas of non-compliance. For example, in response to the new requirement to align programmes with the Paris Agreement (Rule 5), several programmes simply noted that this was not an environmental programme rather than properly assessing climate and environmental impact and risks. The guidance in the PrOF is clear that this rule requires more than stating it is not applicable but, without compliance checks and widespread training, this issue may not be corrected.

Without strong messaging and support from senior leadership, there is a risk of PrOF being viewed as a ‘tick box’ exercise

4.51 Senior management formally endorsed the PrOF, which includes a foreword from FCDO’s Permanent Under Secretary (the department’s most senior civil servant). In practice, however, programme staff from all backgrounds, whether former FCO or DFID, or new to programme management in the FCDO, reported their perception that senior management does not sufficiently value or support the PrOF and that programme management excellence is not yet fully embedded in the department’s culture. The two (former DFID) Heads of Mission we spoke to, who were aware of the PrOF, concurred while a (former FCO) Head of Mission with a major aid budget had never heard of the PrOF.

4.52 Staff report that management sometimes sees the PrOF as a set of compliance checks and that its intent, as a tool to help deliver aid strategically, is not being fully realised. ICAI has also observed this concern in previous reviews. ICAI’s October 2021 rapid review, UK aid’s alignment with the Paris Agreement found that the guidance for Rule 5 missed an opportunity for a more strategic embedding of climate risk management fully into the programme design.

4.53 Similarly, there were concerns among stakeholders interviewed for our February 2022 report, The UK’s approach to safeguarding in the humanitarian sector, that over-emphasis on compliance with standards risked creating a ‘tick box’ approach, with partners more concerned about showing their FCDO programme managers that systems are in place than ensuring they are effective. This shows that, although the approach of the PrOF is commensurate with flexible and proportionate programme management, in principle, this will only translate into practice with the right support for those implementing it. The COSO framework highlights the importance of setting the right tone from leadership and balancing business and compliance incentives, which seem off-kilter in FCDO.

Accountabilities and responsibilities are more complicated than before the merger and were not well communicated

4.54 The PrOF introduced the new mandatory role of PRO, reporting to the SRO. This was modelled on the cross-government standard for project management, where the SRO is accountable for meeting overall programme objectives, and the PRO for day-to-day programme leadership. Alignment with wider government approaches is a positive step, but introducing the PRO role has caused confusion for staff accustomed to SRO-only ownership. Staff have generally perceived the PRO role as adding unnecessary layers of bureaucracy and duplication. In some cases, it has affected morale, especially when former DFID SROs feel demoted to the new PRO role. Centre for Delivery informed us it introduced the PRO role to try to counter the perception of demotion. The turmoil of merging departments and ongoing reductions in the aid budget may have exacerbated some of the negative reaction. However, better communication and explanation around this change may have mitigated these negative effects.

4.55 The PrOF’s addition of the Portfolio SRO reflects the intent of the UK government’s strategy for international development to reduce bureaucracy by giving authority and portfolio oversight to Heads of Mission – the UK’s Ambassadors and High Commissioners – and central Directors of equivalent seniority. Portfolio SROs “have overall accountability for the whole portfolio of activity in the post/directorate, including programmes”.

4.56 Implementation of this is more complex in practice, particularly where interventions relate to regions rather than countries. For example, programme staff based in a Caribbean country seeking approval for a regional programme business case were unsure whether the country Head of Mission or the Regional Director would provide it. Another Caribbean-based Head of Mission agreed that:

“The reporting lines don’t work where everything is regionally managed. Heads of Mission across the Caribbean are not directly responsible for programmes in their countries.”

4.57 The tension between regional and country programme management was also present in DFID and is not new. Centring programme delivery around the Head of Mission is a step toward aligning all policy and programme work around a single-country strategy. However, there are aspects of engagement between regional and country programmes that the PrOF could more clearly address.

4.58 Heads of Mission require support and training in taking on this role of portfolio accountability for aid programmes. The two ex-DFID Heads of Mission interviewed for this review told us that Heads of Mission are not given the proper tools to “actually be accountable”. The ex-FCO Head of Mission we interviewed had not heard of the PrOF before our interview. Although senior-level training is available, it is largely online but mostly not enforced. While the PrOF incorporated much of the good practice from DFID into FCDO, without strong leadership and clear valuing of this approach to programme management from senior management, there is no guarantee it will reach its potential to drive good programme delivery in practice.

Learning: How well has the PrOF been adapted since its launch?

Learning has been built into the PrOF from the outset but focuses on those already engaged

4.59 Centre for Delivery developed the PrOF as a minimum viable product with a view to continuously improve the PrOF as the department evolves and integration completes following the merger. Centre for Delivery captures feedback through its regular engagement with programme teams and reviews the PrOF every six months, amending as necessary.

4.60 Given the significant continuing changes across the organisation following the merger and the ongoing systems integration, Centre for Delivery chose to minimise changes to the PrOF to provide staff with stability and continuity. Amendments to the PrOF since its launch have therefore been minor and generally relate to changes in the business, such as adding newly agreed insourcing roles, or providing small clarifications based on feedback. The Programme Cycle Panel approved all changes based on evidence, although this is already resulting in the expansion of rules and guidance.

4.61 Staff are notified of changes through bulletins and newsletters. The PROs we spoke to were aware of update bulletins although some SROs, who less frequently refer to the PrOF, suggested making track change versions available to enable visibility of the changes when scanning the document. Distribution networks are based around known programme staff and, while they are increasingly comprehensive, this list is a work in progress. Distribution lists do not link to named SROs and PROs from the programme management system which, in any case, may be out of date following staffing changes as was the case in some of our programme sample.

4.62 Although Centre for Delivery informed us it had gathered feedback through engagement, with more than 1,500 members of staff in various forums, these are built around existing networks of those already engaged with the PrOF. Over time, this network has expanded to include teams previously not engaged with the PrOF, such as Chevening and, predominantly, former FCO Arm’s Length Bodies. This has led to important learning about challenges in applying the PrOF in practice but there is a need for wider engagement, especially on smaller or less traditional aid programmes.

Staff are not engaging on the PrOF through surveys

4.63 Centre for Delivery conducts annual surveys to collect feedback on the PrOF, as was the case for the Better Delivery Department for DFID’s Smart Rules. Staff generally gave positive feedback on DFID’s Smart Rules in the 2017-19 surveys. Key concerns raised were flexibility and agility which, while actively promoted within the former DFID, were not always being achieved in practice because of the increasing levels of bureaucracy staff still faced. These concerns were reflected in the Programme Cycle Panel meetings and initial consultations Centre for Delivery held during the PrOF development process. As a result, reducing bureaucracy and simplifying the ruleset were key objectives for Centre for Delivery in developing the PrOF.

4.64 Since the launch of the PrOF, survey responses have dropped to just over 100 in 2021 and only 41 in 2022, whereas DFID had more than 250 respondents in 2019. Respondents in 2021 suggested improvements that were consistent with our findings: the PrOF should be further simplified and shortened; further training is needed; and there was a perceived lack of senior buy-in or appreciation of the importance of programme management. Centre for Delivery deemed the volume of 2022 responses “not enough for a credible overall picture”. Those who did respond gave positive examples of receiving support from Centre for Delivery in applying the PrOF in difficult programme management scenarios but continued to raise concerns about the level of awareness of the PrOF among senior staff. Most of these respondents also considered FCDO to be less flexible and agile than its predecessors.

4.65 Our focus groups and interviews suggest a range of potential reasons for the reduced survey response rate. Most staff we spoke to, who were selected to represent a wide range of FCDO programmes rather than self-selecting through a voluntary survey, said they were not aware of the survey. Many noted they have much greater concerns than the PrOF, such as merging systems, under-staffing and ongoing budget reductions so this would not be a priority. Our review of the surveys also found some questions to be too complex with limited options for answers, which may have deterred some staff. However, the staff we contacted directly to discuss their experiences were extremely responsive. This suggests other forms of engagement beyond surveys, such as direct requests to selected programme staff, potentially through the AMP system or sampled during key points in the programme lifecycle, may provide routes to access input from a wider range of staff.

FCDO has not engaged with other donors in updating the PrOF and has limited engagement with the Infrastructure and Projects Authority (IPA)

4.66 FCDO is yet to engage with other donors as part of the PrOF’s development. In addition, although FCDO has worked to align the PrOF to cross-government standards and good practice set by IPA, according to IPA, FCDO is less engaged in cross-government working groups than other government departments with large programme management budgets.

4.67 Many departments have a full-time Chief Project Delivery Officer, including the Cabinet Office, the former Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy (since separated into the Department for Science, Innovation and Technology and the Department for Business and Trade), the Department for International Trade, the Department for Work and Pensions, HM Revenue and Customs, the Home Office, the Ministry of Defence and Ministry of Justice. The Chief Project Delivery Officer is a senior staff member who represents their department at IPA’s cross-government engagement and learning sessions, and champions project management excellence. In FCDO this role is included in the Finance Director’s remit, which also includes overseeing major systems changes in the department.

FCDO’s programme management systems have the potential to support learning

4.68 As noted in the Effectiveness section above, FCDO’s AMP system has the potential to provide data on compliance or which could support learning, or both. In addition, mechanisms to gather feedback and learning could be incorporated into the platform. These could range from voting buttons to provide feedback when staff come across something that is not clear, to requiring feedback from a sample of programmes each year through the system instead of sending out surveys. In our experience, programme staff were highly responsive when they knew their programme had been specifically sampled for review.

5. Conclusions and recommendations

5.1 The Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office’s (FCDO) rapid development and deployment of the Programme Operating Framework (PrOF) is commendable, especially given the significant internal and external challenges facing the department following its creation. It has helped to create stability for FCDO programme staff. Furthermore, it has ensured good programme management practice, developed within the former Department for International Development (DFID) and former Foreign and Commonwealth Office (FCO) managed aid programmes, has been retained, in particular the concepts of subsidiarity and empowered accountability that are well suited to agile, impact-focused aid delivery.

5.2 The PrOF is a credible approach for the management of UK aid programmes. It is closely based on DFID’s Smart Rules, centred around a set of principles and mandatory rules that have been simplified and tailored to the new department and cross-government standards and priorities. The addition of a Portfolio Senior Responsible Owner at the Head of Mission or Director level situates the empowered accountability model within a portfolio approach to delivering UK priorities, supporting coherence between FCDO’s programmes and policy work. The addition of a Programme Responsible Owner (PRO) role has also helped to align the FCDO with other government departments. In practice, these new roles are not yet well understood, but they have the potential to make FCDO’s official development assistance (ODA) and non-ODA programming better at delivering strategic goals.

5.3 While covering all FCDO programmes makes the PrOF less focused on aid delivery than DFID’s Smart Rules, detailed guidance concerning aid delivery is available in more than 100 PrOF Guides (see Annex 2) which derive from DFID’s ‘Smart Guides’. Moreover, a standardised approach is essential for supporting a unified culture and the development of a wider pool of professional programme management staff, operating to consistent, high standards across all FCDO programmes. This has the potential to benefit aid delivery through a wider pool of staff with more diverse programme management experience. Wider changes and challenges facing staff, largely related to the merger and aid budget reductions, have hampered these potential benefits so far.

5.4 The PrOF’s overall approach is credible, and the principles and rules that form the centre of the PrOF are relatively concise. However, much of the rest of the document is not clearly written, making it harder for readers to find and absorb the most important information. In some cases, language needs to be tightened to clarify what is mandatory and what is advisory.

5.5 Implemention of the PrOF is not complete. FCDO has made good progress among programme staff for more traditional aid programmes but has struggled to gain traction with more senior staff who lack clarity about what the PrOF means to them. This has led to inefficiencies in the PrOF’s implementation and to many programme staff feeling undervalued, although these issues are also impacted by wider challenges related to the merger and budget reductions.

5.6 More work is needed to ensure PrOF promotes efficiency for all programmes, especially smaller aid programmes, those which do not follow the typical programme lifecycle (such as Chevening), and programmes that cut across regions with multiple Portfolio SROs. FCDO’s Centre for Delivery has actively engaged with these programmes when they have come to light, but the challenges of applying the PrOF in such programmes have not yet been fully resolved.