The Management of UK Budget Support Operations

Executive Summary

The Independent Commission for Aid Impact (ICAI) is the independent body responsible for scrutinising UK aid. We focus on maximising the effectiveness of the UK aid budget for intended beneficiaries and on delivering value for money for UK taxpayers. We carry out independent reviews of aid programmes and of issues affecting the delivery of UK aid. We publish transparent, impartial and objective reports to provide evidence and clear recommendations to support UK Government decision-making and to strengthen the accountability of the aid programme. Our reports are written to be accessible to a general readership and we use a simple ‘traffic light’ system to report our judgement on each programme or topic we review.

Budget support is aid given directly to a recipient government to spend through its normal budgetary processes. At £644 million in 2010-11, it represents 15% of the UK’s bilateral aid budget. This evaluation assesses whether DFID makes appropriate decisions as to where and in what quantity to provide budget support and whether the processes by which DFID manages its budget support operations are appropriate and effective.

Overall

Assessment: Green-Amber

In the right conditions, budget support can offer an effective and efficient way of providing development assistance. Its practical value, however, varies substantially according to the country context and the dynamics of the development partnership. The amount of budget support should, therefore, be determined by reference to the policy and institutional environment. In most cases, budget support should be balanced by other, more hands-on, aid instruments.

Objectives

Assessment: Green-Amber

DFID is now identifying more rigorously what benefits it expects from budget support operations and how to balance budget support with other types of aid. It nonetheless needs clearer criteria for determining the amount of budget support to provide and a greater willingness to adjust the level in response to changes in the performance of the instrument.

Delivery

Assessment: Amber-Red

DFID plays a leading role in general budget support operations, forging strong relations with recipient governments and other donors. It is not, however, taking an active enough approach to managing fiduciary risk and ensuring good value for money of spending through the national budget process. We are concerned at signs of a bias towards optimism in DFID’s assessment of partner country commitment to public financial management reform and fighting corruption. Also, DFID does not always take a strategic approach to policy influence and its methods of linking payment levels to performance are not wholly convincing. While we welcome the renewed emphasis on national accountability, the effectiveness of current programming is yet to be demonstrated.

Impact

Assessment: Green-Amber

UK budget support operations have led to increased expenditure on poverty reduction and basic services, generating progress towards the Millennium Development Goals. In some cases, however, lasting impact will depend on progress in overcoming political and institutional bottlenecks to more effective development expenditure and service delivery. This may not be achievable through budget support alone, indicating a need for more hands-on approaches to accompany budget support.

Learning

Assessment: Amber-Red

Budget support operations are designed around continuous monitoring and there is good evidence of learning from experience. DFID’s reporting on results, however, should capture the transformational effects of UK budget support and real impact for intended beneficiaries, rather than simply measuring the extent of the UK subsidy to basic service delivery.

Recommendation 1: DFID should determine the amount of budget support to provide based on an assessment of how much poverty reduction can realistically be achieved through expanding public expenditure given the quality of national policies and institutions.

Recommendation 2: DFID should build its general budget support operations around the possibility of higher and lower levels of funding, with a substantial increment between them, to send clear signals on performance and free up resources from non-performing operations.

Recommendation 3: DFID should set clear targets for progress on public financial management reform and anti-corruption for each of its budget support operations and link future funding levels to progress achieved.

Recommendation 4: DFID should strengthen its approach to managing short-term fiduciary risk in its budget support operations through more active measures to address specific risks identified in Fiduciary Risk Assessments.

Recommendation 5: Both general and sector budget support operations should include explicit strategies for tackling constraints on efficient public spending and ensure that these are addressed systematically in policy dialogue and reform programmes.

Recommendation 6: DFID should develop explicit influencing strategies in respect of the issues it deems critical to each country’s development path, combining budget support dialogue with other approaches such as funding research and advocacy, media campaigns and working with parliament in the recipient country.

Recommendation 7: DFID should look for every opportunity to promote national accountability, including through sharing information on recipient government performance generated within budget support operations with parliament and other national stakeholders.

Recommendation 8: DFID should change the way it assesses and reports on the results of its budget support operations, to capture the transformational effects of UK budget support rather than simply the extent of the UK subsidy to basic service delivery.

1 Introduction

1.1 Since the 1990s, the Department for International Development (DFID) has been one of the leading pioneers and advocates internationally of budget support as a form of development assistance. Budget support is aid given directly to a recipient government and spent using its normal budgetary processes. General budget support is a contribution to the national budget as a whole. Sector budget support is earmarked for a particular sector or development programme.

1.2 The UK has provided budget support in various forms for decades, principally as macroeconomic support to help partner countries through periods of economic crisis. Budget support emerged in its current form in the late 1990s. In conjunction with international debt relief, it was developed as a method of helping partner countries to finance the implementation of their poverty reduction strategies. In particular, budget support provides partner countries with additional resources to meet the recurrent costs of expanding basic services like health and education to achieve the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs).1

1.3 This evaluation mainly focusses on general budget support. Our report on education programmes in East Africa2 looks in more detail at a number of sector budget support operations. In this review, we assess whether the processes by which DFID manages its budget support operations are appropriate and effective, including the extent to which:

- DFID makes appropriate decisions as to where and in what amount to provide budget support;

- the objectives for budget support operations are realistic;

- the operations are designed and managed so as to minimise risk; and

- the operations are achieving impact.

1.4 Budget support is a controversial part of the UK aid programme. We have received submissions from some parties to the effect that DFID should never provide budget support because it offers no protection against the misuse of aid funds. Others, however, claim that budget support can be one of the most effective forms of assistance. In this review, we do not offer an overall judgement on the merits of budget support as a type of assistance, as it is not our remit to make recommendations on policy. Rather, we assess whether DFID’s budget support operations are appropriately designed and implemented and are providing aid which is effective and value for money both for the intended beneficiaries and the UK taxpayer.

UK budget support

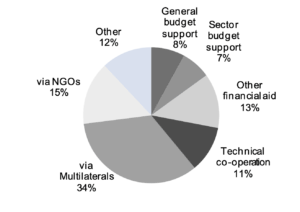

1.5 In 2010-11, DFID provided a total of £644 million as budget support, or 15% of its bilateral aid budget3 (see Figure 1 on page 3). A further 13% is provided as other forms of financial aid, which includes funding provided to the governments of Afghanistan and Palestine via multi-donor trust funds. These are similar to budget support, although with a higher level of fiduciary protection. Some of the aid that the UK gives to multilateral organisations also funds budget support – namely around 25% of funding for the European Union’s development budget4 and 10-15% of the World Bank International Development Association allocation.5 This evaluation addresses only budget support operations managed directly by DFID.6

Source: Statistics in International Development, DFID, 2011

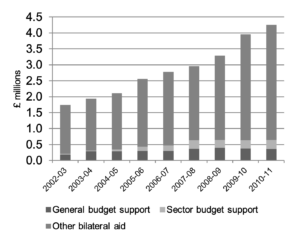

1.6 As shown in Figure 2, the proportion of budget support in the bilateral programme rose steadily between 2002 and 2008, peaking at 17.7%. Since then, it has remained stable in absolute terms, while declining as a proportion of an expanding aid budget to a projected 12% by 2014-15. DFID expects that this trend will continue, with a gradual rebalancing of the UK aid programme away from budget support and a shift from general to sectoral budget support.7 A number of DFID staff expressed the view to us that this trend was due in large part to the increased pressure on DFID to demonstrate results from its operations.

Source: Statistics in International Development, DFID, 2011

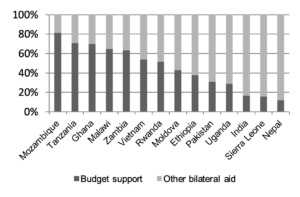

Source: Statistics in International Development, DFID, 2011

1.7 In 2010-11, fourteen countries received UK budget support (see Figure 3). The level ranges from 12% of the country programme in Nepal and 15% in Sierra Leone, the only fragile states in the group, to above 80% in Mozambique. In absolute terms, the largest recipients of UK budget support are Tanzania (£103.5 million) and Ethiopia (£94.7 million). In recent years, seven countries (Mozambique, Tanzania, Ghana, Malawi, Zambia, Vietnam and Rwanda) have received more than half of their UK aid in the form of budget support. In all cases except Pakistan, however, this proportion is projected to decline in the coming years.

1.8 In DFID’s budget support operations, financial support is packaged together with additional support designed to strengthen national systems and capacities. This includes investments in public financial management (PFM) reform, national statistical systems and accountability mechanisms such as national audit offices and parliamentary budget committees. Budget support operations include processes for agreeing on annual reform priorities and development targets and regular reviews of progress. In most cases, part of the financial support varies according to the recipient government’s progress on agreed commitments and targets. In budget support countries, these processes provide a platform for dialogue between the government and donors on development priorities, becoming central to the organisation of the development partnership.

DFID’s rationale for budget support

1.9 This section briefly describes DFID’s rationale for and use of budget support, as well as some of its characteristics, by way of background for the reader. These are not, however, findings of our review.

1.10 DFID’s increasing use of budget support in the mid-2000s was part of a shift in thinking within the international development community as to what constitutes effective aid. Many donors became concerned about the limitations of traditional aid projects in delivering sustainable development results. Traditional projects are administered directly by donors or their agents and focus on the delivery of particular outputs, such as the construction of a new road or hospital or the transfer of particular technical skills. Projects provide a means of bypassing weaknesses in national systems and capacities, giving donors greater assurance that their funds will be used for the intended purpose. This assurance may come, however, at the expense of a missed opportunity to help the partner country build up the institutions and capacity it needs to achieve development results on a sustainable basis.

1.11 To change this dynamic, the UK and other donors made a commitment under the 2005 Paris Declaration on Aid Effectiveness8 to provide two-thirds of their assistance in the form of programme-based approaches. Budget support is one example of this (programme-based approaches also include other aid modalities that do not necessarily use country systems). Under programme-based approaches, donors fund the implementation of a development policy or programme by the recipient government. Rather than dictating precisely how the funds should be spent, donors allow the partner country to apply the funds flexibly towards an agreed set of development objectives. This is thought to strengthen national ownership of the development process and to make recipient governments more accountable domestically for their use of the funds. According to the international consensus behind the Paris Declaration, programme-based approaches offer a range of other potential benefits over project aid, which are summarised in Figure 4. DFID was highly influential in developing this international consensus.

Traditional projects

- Donor-led

- Undermines ownership and accountability

- Fragmented assistance

- Bypasses country systems

- Supports capital expenditure and technical assistance

- Donor support is more volatile

- Higher aid-management costs

- Sustainability more difficult to achieve

Budget support

- Partner country-led

- Strengthens national ownership and accountability

- Facilitates donor harmonisation

- Uses and strengthens country systems, including the national budget

- Supports recurrent expenditure

- Donor support is more predictable

- Lowers aid-management costs

- Generates more sustainable results

1.12 DFID and other donors use budget support operations as platforms for influencing national policy processes and the composition of the national budget. They therefore seek to improve the way in which the partner countries manage not just external assistance but their entire budget. In even the poorest countries, the national budget is a far larger pool of resources than development aid. In Africa, total government revenues are over ten times the volume of development aid flowing to the continent.9 If budget support operations can positively influence this much larger resource envelope, the developmental benefits may be substantial.

1.13 When providing budget support, donors make a contribution to the national or sectoral budget as a whole. While they can claim a share of all development spending under the national budget, it is equally true to say they contribute to non-developmental expenditure, such as the military budget. Indirectly, however, the same can be said for all forms of aid. Aid funds given for a specific purpose, e.g. building a hospital, may free up additional national resources for spending on other purposes.

1.14 Budget support is also directly exposed to any waste or misuse of funds within the national budget. For example, in 2002 the Government of Tanzania drew international criticism for its decision to purchase a £15 million presidential jet.10 The recipient government retains the right to set its own expenditure priorities. DFID argues, however, that general budget support donors are better placed to influence the composition of the budget to minimise waste and promote development. These are controversial aspects of budget support and the reason why some donors choose not to provide aid in this form.11

Evaluation methodology

1.15 In carrying out this evaluation, we reviewed available literature and evaluations on past budget support operations. We examined DFID policies and guidance on budget support and fiduciary risk management and interviewed senior management and policy teams. We carried out detailed case studies of general budget support operations in Rwanda and Tanzania and a lighter case study of budget support in Pakistan. In the two detailed case studies, we interviewed DFID staff, other donors (including donors who do not provide budget support), representatives of non-governmental organisations (NGOs) and a wide range of partner country officials (ministries of finance, aid co-ordination agencies, sectoral ministries, auditors-general) and parliamentarians (including public accounts committees). While the nature of budget support makes it difficult to collect feedback directly from the intended beneficiaries, we consulted with NGOs and parliamentarians as a proxy for beneficiary voice.

1.16 The evaluation focusses primarily on general budget support operations but many of the observations and recommendations in this report also apply to sector budget support. It was conducted in tandem with our review of DFID education programmes in East Africa (Ethiopia, Rwanda and Tanzania),12 which looked closely at education sector budget support. This report draws on the findings of both studies.

| Rwanda | Tanzania | Pakistan | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Level of UK general budget support 2010-11 | £37 million, of which £35.8 million disbursed | £115 million, of which £103.5 million disbursed | £30 million, fully disbursed |

| Proportion of total UK aid disbursed to the country | 49% | 71% | 29% |

| Performance tranche13 | £5 million (15%) | £11.5 million (10%) | £30 million (100% subject to performance triggers) |

| Total general budget support (all donors) | £167 million | £390 million | £104 million |

| Total general budget support as a proportion of the national budget | 14% | 9% | 0.6% |

| Total general budget support as a proportion of Gross Domestic Product | 4.7% | 2.6% | 0.1% |

| Description | The UK has provided general budget support since 2001, providing funds to rebuild national institutions following the genocide and to enable implementation of the national poverty reduction strategy. The UK also provides sector budget support in health, education and agriculture. | The UK has provided general budget support since 2001 to support implementation of the national poverty reduction strategy. For 2011-12, DFID has reduced the overall level of budget support to £80 million, of which £30 million will be earmarked for the education sector. | The UK has provided general budget support since 2005, with the primary goal of boosting poverty-reducing expenditure in the national budget, which increased by 37% from 2005-06 to 2008-09. A second budget support operation for 2009-13 for a planned total of £120 million was discontinued after two tranches of £30 million each, owing mainly to an amendment to the Constitution that devolved responsibility for most development spending to the provincial level. The funds were redirected to support victims of the 2010 flooding. The UK continues to provide substantial sector budget support at the provincial level. |

Sources: data provided by DFID

2 Findings

Objectives

Assessment: Green-Amber

2.1 This section assesses how DFID makes decisions on when to provide budget support and in what form and amount. It then considers whether DFID has clear and appropriate objectives for its budget support operations.

Criteria for providing budget support

2.2 In July 2011, DFID introduced a strengthened approach14 to budget support, which elaborates on earlier policies.15 DFID ministers approve all general budget support programmes over £20 million in value, on the basis of business cases prepared by country offices. The new approach sets out a two-stage process for deciding when to provide budget support and in what form. First, budget support should only be provided to a government that demonstrates a credible commitment in four areas:

- poverty reduction and the MDGs;

- respecting human rights and other international obligations;

- improving public financial management, promoting good governance and fighting corruption; and

- strengthening domestic accountability.16

Second, budget support must be assessed as delivering better results and value for money than other aid instruments.

2.3 DFID assesses a country’s commitment to poverty reduction by examining budget allocations for growth and poverty reduction and seeing whether the budget seeks to address inequalities between different regions or social groups. DFID also examines the country’s macroeconomic policies and its performance against key poverty measures. Where a commitment to poverty reduction is in place, DFID may choose to provide budget support, where this is assessed to be the best way to achieve results and value for money in that country. For example, Vietnam has one of the most impressive development records in the world: the poverty rate fell from 60% living below the national poverty line in 1990 to around 10-12% in 2010.17 It has achieved this in part through a major redistribution of budgetary resources to its poorest communities. As a result, DFID assessed that the £30 million of UK budget support (53% of the country programme) provided to Vietnam in 2010-11 represented good value for money.

2.4 Guidance on assessing a country’s commitment to human rights and other international obligations was introduced in 2009 and complements the human rights component of the DFID Country Governance Analysis. Both sets of guidance are currently being updated. No minimum standard for compliance with international human rights obligations is specified. Rather, DFID requires a credible commitment to achieving those standards over time. This enables it to provide budget support to a number of countries with closed political systems and a difficult history of civil and political rights. DFID argues that it has more positive influence as a budget support donor and that periodic setbacks should not lead to an automatic suspension of budget support.

2.5 Any decision to terminate budget support on human rights or political grounds is taken at ministerial level. In 2005, the then Secretary of State for International Development terminated general budget support to Ethiopia following large-scale violence during an election campaign. This was, however, replaced shortly afterwards with a sector budget support programme supporting local service delivery but without channelling funds through central government. More recently, general budget support to Malawi was discontinued for a number of reasons, including concern over a deteriorating political and human rights situation (see Figure 6 on page 8).

In 2011, DFID decided to discontinue general budget support to Malawi. The decision was based on a number of factors. Macroeconomic management had deteriorated and the 2011 budget was regarded as lacking credibility. DFID was also concerned about Malawi’s worsening human rights record, with problems around freedom of the press and democratic space. The decision of DFID and other donors to discontinue budget support left a significant gap in the budget, causing government programmes to be curtailed. DFID responded by redirecting its funds to the procurement of fertiliser and essential medicines, to mitigate the impact on the poor.

2.6 The UK National Audit Office concluded in a 2008 review of DFID budget support operations that monitoring of the commitment to human rights had not been done systematically.18 Our finding is that DFID is now well informed about the human rights situation in its partner countries, both through its periodic Country Governance Analysis and through more regular monitoring.

2.7 There are no minimum conditions for the quality of a country’s financial system or its level of corruption risk. This enables DFID to provide budget support to countries with known weaknesses in their PFM systems, provided they show a credible and continuing commitment to addressing them. Their continued commitment is assessed through regular Fiduciary Risk Assessments.

2.8 This is a controversial aspect of budget support. DFID has stated that it is unable to quantify its potential losses to corruption when channelling funds through the budget19 (see our report on DFID’s approach to corruption20). Potentially, the risks of losses when funding through the national budget may be much greater than in project aid, where the funds are under DFID’s direct supervision, although we have seen no definitive evidence one way or another.21

2.9 Some commentators have suggested that the UK should set clear minimum fiduciary standards as preconditions for budget support, using objective assessment methods. For example, Paul Collier argues that budget support should be limited to those governments that are well-intentioned towards their citizens and which have a reliable public spending process. While the former is a political judgement, the latter is a technical one that should be left to third-party experts.22 DFID argues that, if budget support is a tool for addressing weaknesses in country systems, it makes no sense to wait until those weaknesses have already been addressed. The experience in Rwanda, where DFID began providing budget support at a time when public financial systems were in substantial disarray, seems to bear this out, although the experience in other cases has not been as positive.

2.10 In effect, DFID is trading off short-term fiduciary risk for the opportunity to advance longer-term development goals.23 The flexibility to do this is arguably one of DFID’s strengths as a development agency. Where such a trade-off is made, however, continuous and rigorous assessment is required both of the risks and the benefits.

2.11 We are, therefore, concerned at signs of a bias towards optimism in DFID’s assessment of partner country commitment to PFM reform and fighting corruption. In Tanzania, for example, many of the people we spoke to questioned the level of commitment in recent years. DFID has nonetheless chosen to continue with general budget support, although at a reduced level. DFID Tanzania makes the argument that PFM reforms are necessarily long and difficult and that the budget support ‘tap’ should not be turned off every time there is a setback. While we accept that predictability of resource flows is a key element in budget support operations, this logic comes close to contradicting the official policy, which calls for rigorous monitoring of recent progress on reform in assessing continued eligibility for budget support.24 Where a country consistently fails to back its commitment to PFM reform with concrete action, it should lead to a reassessment as to whether budget support is appropriate.

2.12 The fourth underlying condition is a commitment to strengthening national accountability mechanisms. There are no minimum standards or prescribed forms of accountability but an assessment is made periodically through a Country Governance Analysis. This is a new element of DFID’s budget support approach introduced in 2011 and country offices are still working through the practical implications.

Objectives of budget support operations

2.13 If the underlying conditions are established, the second criterion for UK budget support is whether it offers better results and value for money than other aid instruments. This involves identifying the objectives of each budget support operation and examining whether they could be achieved more effectively by other means. Since January 2011, this is done through a formal business case. The intangible nature of many of the benefits DFID claims for its budget support operations, however, makes rigorous comparison difficult.

2.14 There is no common or overarching set of objectives for DFID budget support operations. Rather, budget support is an approach used for different purposes in different countries. In the cases we examined, we understand DFID’s objectives for budget support operations as falling into three categories. The first category is direct financing effects:

- budget support is usually given to help finance the implementation of a national or sectoral development strategy. In aid-dependent countries, budget support provides a substantial increase in the resources available for development spending and basic service delivery. In Rwanda, budget support from all donors funds 14% of the national budget, while in Tanzania it is 8% (down from a high of 20% in 2003-04). In Pakistan, where total budget support is only 0.6% of the national budget, the direct financing effects are minimal;

- in post-conflict environments (including Sierra Leone and, initially, Rwanda), budget support provides funds for the re-establishment of government institutions; and

- budget support is also intended to help partner countries maintain macroeconomic stability. In both Rwanda and Tanzania, it enabled the governments to expand development spending without increasing their debt burden. During the global financial crisis, the donor community provided additional budget support to enable partner countries to implement counter-cyclical measures and strengthen social protection.

‘During the war, we had plenty of humanitarian assistance but when we signed the peace agreements, all this aid started to go away. Budget support helped us to support recurrent budget expenditures and to complement the efforts in governance building. It has helped in restoring macro-economic stability, which is a benchmark if you want to move forward.’

2.15 The second category of objectives is policy and institutional effects. As part of a budget support operation, the government and donors agree an annual set of policy actions and development targets, with a joint review mechanism to assess progress. DFID provides part of its budget support, usually of the order of 10-15%, in the form of a performance tranche. This is disbursed in proportion to the level of progress against the agreed commitments. DFID uses the dialogue platform around its general budget support to pursue a range of objectives, such as:

- influencing the composition of the national budget;

- supporting cross-government reform initiatives, particularly in PFM;

- encouraging sound economic management; and

- addressing any development issues that cannot be resolved through sectoral dialogue, including cross-cutting or thematic issues.

These influencing objectives are central to the importance that DFID attaches to budget support operations.

2.16 The third set of objectives concerns aid effectiveness (that is, the principles and goals set out in the Paris Declaration and its successor instruments26). Both general and sector budget support are designed to structure the interactions between the recipient government and donors into a regular and predictable form. Budget support encourages donors to align behind the recipient government’s development efforts, rather than pursue separate agendas. This could reduce the burden on the recipient government of managing aid (although the evidence on this point is equivocal). While budget support operations are time-consuming, the costs involved may be lower than the alternative of managing separate bilateral projects and policy dialogues from each of the donors.

2.17 We found a solid consensus among the stakeholders we consulted in our case study countries that these goals are relevant and important. In particular, the recipient governments themselves put a strong case to us as to why budget support enabled them to make better use of their aid flows. These benefits, however, are by no means automatic. In the next section, we discuss some of the major differences we observed in how well these processes operate in different countries. In general, we found that DFID’s central role in multi-donor budget support operations affords it a useful platform for influencing the donor agenda and engaging with the recipient government on its policy and budgeting choices. The resulting influence, however, remains fairly modest. The most important eligibility criterion for UK budget support, therefore, should be whether it offers a more efficient and effective way of reaching the intended beneficiaries than the alternative channels. We are encouraged to see that DFID is now taking a more rigorous and realistic approach to identifying exactly what benefits can be expected of budget support in each country.

2.18 We note, however, that DFID does not have clear criteria for determining the amount of budget support to offer. In the past, DFID sometimes appears to have assumed that, if the conditions were in place for budget support to be effective, then more budget support would necessarily be better. In some cases, it reached close to 90% of the country programme, with little analysis as to whether the benefits would continue to increase in proportion to the scale of the funding.

2.19 In almost all cases, DFID is now reducing the proportion of budget support in its country programmes and rebalancing from general to sector budget support. In respect of our case study countries, we take the view that the policy and institutional effects and aid effectiveness goals could be achieved equally well with a lower level of general budget support. There is some evidence that there may be diminishing returns on higher levels of budget support. Injecting more funds into the social sectors without addressing the political and institutional bottlenecks to more effective services may not represent value for money – a point reinforced in our concurrent study on education in East Africa.27 Given this concern, we encourage DFID to develop a more explicit rationale for its decisions on the amount of budget support to provide, based on the returns to be gained from increasing budgetary resources in the specific institutional context of each country. Sector budget support may in some circumstances provide a better platform for addressing complex institutional reforms. We would expect to see general or sector budget support accompanied by targeted technical assistance and capacity-building to address constraints on effective and efficient public spending.

Delivery

Assessment: Amber-Red

2.20 This section looks at how effectively DFID’s budget support operations are designed and implemented, focussing on the management of fiduciary risk, dialogue and influencing processes and support for national accountability.

Managing fiduciary risk

2.21 Managing fiduciary risk is central to the effective delivery of budget support operations. If budget support entails a trade-off between fiduciary risk and development benefit, then the risks must be carefully assessed and minimised to make the risk–benefit ratio as favourable as possible. There are two elements to this. One is to strengthen national PFM systems in order to reduce leakage and corruption risk. The other is to ensure that national budget processes are able to allocate funds wisely against national development targets and that inefficiencies in spending are minimised.

Minimising losses through corruption

2.22 In budget support operations, all funds are accounted for through national systems. Having passed the funds to the national treasury, it is not possible to track the UK’s contribution through to the point of expenditure. DFID’s role is limited to reviewing national budget execution and audit reports regarding the national budget as a whole.

2.23 Fiduciary Risk Assessments (FRAs) and annual updates are mandatory for budget support operations. DFID has produced substantial guidance on how to conduct FRAs, updated most recently in June 2011.28 FRAs are usually prepared by external consultants. They are internally peer reviewed and quality assured externally. They examine the quality of PFM systems, assess the credibility of ongoing PFM reforms, assess residual risks for budget support and propose additional safeguards. The indicators for assessing PFM systems now reflect agreed international standards, in particular the Public Expenditure and Financial Accountability (PEFA) assessment framework, which DFID has helped to promote internationally. From our own observations and opinions gathered from informed observers, the FRAs are prepared to a high professional standard and provide a wealth of information on the strengths and weaknesses of national systems. This includes political economy analysis of the incentives working for and against PFM reform.

2.24 According to DFID guidance,29 the management of the residual fiduciary risks identified through the FRA comprises two elements. First, any budget support operation should include support for PFM reform. Second, recognising that PFM reforms may need some years to take effect, DFID should identify short-term risk mitigation measures for the intervening period.

2.25 While there is no doubt that DFID gives high priority to PFM reform, we were unable to identify many examples of short-term risk mitigation measures. DFID guidance appropriately cautions against safeguards that might undermine ongoing PFM reforms but suggests a number of areas (increased budget transparency; stronger internal and external accountability; increased participation of citizens and civil society) where measures could be taken to address weak links in the PFM cycle.30 Examples might include bringing in external audit experts to work with the Supreme Audit Institution, introducing additional checks on large-scale procurement or using tracking surveys to monitor transfers between levels of government. Special vigilance may also be required in pre-election periods. We expected to see more use of the detailed analysis available in the FRAs to identify measures of this kind, to be agreed with the recipient government as a condition of budget support. We also expected to see more evidence of DFID actively monitoring the most important risks identified in the FRA.

2.26 All of the budget support operations we examined give high priority to PFM reform, both in the policy dialogue and through accompanying technical assistance. In Rwanda, DFID’s decision to provide budget support in 2000, when government systems were still in disarray, was a high-risk strategy. DFID’s willingness to provide budget support and the government’s desire to attract other budget support donors ensured that strengthening the budget process and national PFM systems received high priority. Some major institutional reforms, including the creation of the Rwanda Revenue Authority (for tax collection) and the National Tender Board (to oversee public procurement), were agreed through the budget support dialogue. As a consequence, revenue collection increased from 9% of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) in 1998 to 14% in 2009. The budget is now assessed as a credible instrument, corruption is well below regional norms and overall fiduciary risk is assessed as ‘moderate and declining’.31 While legislative scrutiny has in the past been weak, at the time of our visit a newly created Public Accounts Committee was in the process of carrying out energetic hearings into issues identified in the Auditor-General’s reports.

2.27 Not all of these achievements are attributable to budget support. The Rwandan Government, however, claims that PFM capacity in sectors with a high proportion of aid passing through the budget (such as education, at 95%) has improved faster than in sectors like agriculture where projects are predominant. Budget support has also strengthened the position of the Ministry of Finance over the line ministries, creating more discipline and accountability within the budget process. All of the observers we consulted agreed that budget support had provided additional momentum to PFM reform.

2.28 In Tanzania, DFID’s support for PFM reform (through a multi-donor basket fund) has proved more problematic. There have been disappointing results in recent years in the face of a lack of leadership from the Tanzanian Government and what some stakeholders described as a poorly designed and delivered package of assistance (now redesigned for a new phase). Corruption remains rife across the administration and there have been few examples of successful corruption prosecutions. Government–donor dialogue on corruption has broken down a number of times. On occasions, when the budget support dialogue has been led by other donors, the corruption issue has not been pursued as actively as it might have been.

2.29 DFID’s comparison of the scores from the PEFA assessment of 2010 with those from 2006 indicate that while there were some improvements, more scores deteriorated than improved. The obstacles to effective public spending are multiple and complex, with deep roots in Tanzania’s political economy.32 Attempts to drive forward reforms through conditions within the budget support instrument resulted in a deterioration of relations between the Tanzanian Government and donors, although these have improved over the past 12-18 months. DFID, however, informs us that, despite the obstacles, PFM in Tanzania is still slightly better than the regional norm and that the government has recently renewed its commitment to PFM reform.

2.30 The experience in the two countries is, therefore, very different. In Rwanda, budget support accelerated progress on PFM reforms from a low base, vindicating DFID’s willingness to accept higher levels of short-term fiduciary risk in pursuit of longer-term development gains. Tanzania undoubtedly presents a more difficult challenge and it is not surprising that PFM reforms have proved to be prone to setbacks and periods of stasis. This also makes it more difficult to keep a consistent and strategic focus across the donors. In this more difficult context, the budget support operation has helped DFID to manage a difficult partnership but without generating major breakthroughs.

Improving budgetary efficiency

2.31 Controlling the leakage of funds through corruption or financial mismanagement is only one aspect of managing fiduciary risk. The value for money of budget support is determined by the overall efficiency of public spending on poverty reduction. Many factors can influence this, from the quality of budget processes to the accuracy of national statistics. The quality of national procurement systems is an important factor. There is evidence from our case study countries that funds transferred from the national budget down through sub-national government to local service delivery units (e.g. schools and health centres) often suffer substantial losses, due to excessive layers of bureaucracy. This can significantly undermine the value of national development expenditure and therefore of aid funds provided via the national budget.

2.32 In its budget support operations, DFID is a strong advocate for increased budgetary allocations to the social sectors, with some success in all of our case study countries. It is also the leading bilateral investor in national statistical systems, to improve the quality of data. We observed, however, that DFID does not have a clear overview of the factors that influence the efficiency and value for money of development spending through the national budget in each country. Neither does DFID have an explicit strategy for addressing them. We would like to see more use of assessment tools like Public Expenditure Reviews to assess the efficiency of public spending (ideally in collaboration with the recipient government and other donors). We would also like to see more use of multi-country evidence and analysis to devise strategies for increasing the value for money of public spending to be pursued within budget support operations.

Dialogue and influence

2.33 Policy influence in budget support operations is advanced in two ways. First, there is a structured process of policy dialogue, leading to agreement on policy actions and targets and a joint annual review process. Second, performance incentives are built into the budget support instrument through the use of performance tranches. A proportion of the budget support, usually of the order of 10-15%, is disbursed in proportion to the percentage of indicators in the Performance Assessment Framework (PAF) that have been met (see Figure 8). Any undisbursed amount is reallocated to other programmes within the same country.

In Rwanda, £5 million from the general budget support instrument is provided as a ‘variable tranche’. Each year, DFID awards 0%, 50%, 75% or 100% of the variable tranche, depending on how many of the indicators under the Common Performance Assessment Framework have been met. The assessment is done jointly by the Rwandan Government and the budget support donors. In 2011, there were 45 indicators in the Framework. In recent years, 90% of the variable tranche has been paid.

2.34 DFID invests a great deal of effort into these dialogue processes, thereby gaining considerable influence over the collective donor agenda. It forges very good working relations at the centre of government, particularly with ministries of finance. Its role is strongly appreciated by both the recipient governments and donors. Many of the stakeholders we spoke to were of the view that DFID’s strength as a donor is its ability to engage with the policy process. We were less convinced, however, that the use of performance tranches adds substantially to its level of influence.

2.35 A general budget support operation enables DFID to engage with issues such as the credibility of the budget, macroeconomic management and cross-government reforms. General budget support is the only aid modality designed around achieving influence at this macro level. Our case studies, however, suggest that the degree of influence it affords is modest, though useful.

2.36 In Rwanda, for example, the government provides the budget support donors with its budget framework paper, giving them an opportunity to comment on the overall composition of the budget. Observers on both the donor and government sides informed us that this provides an opportunity for good quality, two-way dialogue and that government is generally responsive to donor input where it is seen as helping the government to achieve its development goals. One example offered was that donors had helped to increase the focus on urban poverty within Rwanda’s development planning.

2.37 Against that must be set the Rwandan Government’s tendency to make policy through large, bold initiatives, often communicated to donors at the last minute and over which they have little influence. Examples include decisions to shift the language of instruction in schools from French to English and to introduce an entitlement to free upper secondary schooling – both decisions with major consequences for donor-supported programmes. In addition, weaknesses in capacities and systems in Rwanda mean that agreements reached in the budget support dialogue are not always translated into effective action, which limits the impact of dialogue at this level.

2.38 The partnership with the Rwandan Government has been marked by periodic concerns over human rights and political openness. The UK Government has an active influencing agenda around these issues, mainly through bilateral channels. While joint donor statements on these issues are sometimes presented in the budget support dialogue, the process is not necessarily well suited to dealing with sensitive political matters. DFID and Foreign and Commonwealth Office officials informed us, however, that the UK’s position as the leading bilateral budget support donor lends weight to UK work in this area.

2.39 In Pakistan, one of the objectives of the budget support operation was to improve the poverty orientation and efficiency of the national budget – a very ambitious goal in the country context. DFID’s own reporting33 suggests that national expenditure on poverty reduction increased during the first budget support cycle, only to fall away subsequently in the face of a sharp economic downturn. DFID had some success in introducing stronger tools for budget management but the gains were offset by the Pakistani Government’s inability to drive through some difficult economic reforms, leading to a deterioration in macroeconomic management. Continuing weaknesses in budgetary processes, including the alignment between budget and development plans and weakness in the costing of development programmes, make it difficult to conclude that there have been any longer-term gains from influence at this level.

2.40 In Tanzania, the political context for influence has been difficult. National leaders are preoccupied with factional struggles34 and political commitment to the national development agenda is less evident than in Rwanda. The dialogue process is highly formal in nature, with both sides delivering prepared statements and little opportunity for two-way exchange of views. The majority of conditions in the PAF are assessed positively each year. A number of areas, however, on which the budget support donors have focussed most strongly – particularly reforms to PFM and the business environment – have performed poorly. DFID’s country programme evaluation concluded that the level of information-sharing had fallen over time, leading to a decline in the quality of dialogue.35 It appears that a lot of time and energy are devoted to maintenance of the dialogue process itself, rather than to addressing development policy.

2.41 Given this more difficult political context, the budget support platform is valued by DFID as a tool for managing risks to the development partnership, such as corruption scandals or misuse of budgetary resources. The general budget support operation enables DFID to send carefully calibrated signals in response to such issues, from joint donor statements, to launching special dialogue processes, to delaying or cancelling payments.

2.42 For example, in Tanzania, budget support donors were dissatisfied with government action in response to a major corruption scandal in the Bank of Tanzania. Donors invoked a provision in their budget support agreement to establish a high-level dialogue, leading to agreement on a package of corrective measures (e.g. investigations, prosecutions, systemic reforms) and regular reporting on implementation. There has been one successful conviction to date and other related cases are at various stages of investigation and prosecution. While progress on anti-corruption remains slow, having a range of options makes it more likely that such an event can be managed without leading to a major rupture in government–donor relations.

2.43 Overall, the dialogue platform is only as useful as the influencing agenda that DFID and other donors bring to it. The process can easily become overcrowded with too many competing donor agendas and lose its strategic focus. There is also a tendency for the dialogue to follow the most pressing issues of the day, without pursuing a consistent set of goals over time. DFID has recognised that greater selectivity is called for. It was not clear to us, however, that DFID has given enough consideration to identifying the issues that are most critical to each country’s development path. Where DFID selects priority issues to pursue through the general budget support dialogue, it might also be appropriate to make this part of a broader influencing strategy, for example funding civil society research and advocacy or working with parliament and the media.

2.44 As might be expected, the level of influence is greatest when the recipient government is committed to poverty reduction and interested in donor input into how to achieve its goals. In such cases, the structures around budget support clearly help to make the interaction between the recipient government and donors more productive than it would be with parallel, bilateral discussions.

2.45 When that commitment weakens, however, the quality of the budget support process is likely to be a casualty. In Tanzania, frustration with slow progress on reforms led donors to tighten up the conditions in the PAF and link them more directly with disbursement levels, in an attempt to generate greater accountability. The result was that the dialogue deteriorated into negotiations over the wording of individual PAF indicators and influence was lost. DFID’s Tanzania country programme evaluation concluded:

‘Where performance targets become interpreted as disbursement conditions, there is an obvious interest on the government side to ‘keep the bar low’ so as to fulfil targets and secure disbursements, whereas the incentive on the DP [development partner] side is to raise the bar so as to increase “policy leverage”. This can only lead to protracted and conflictive negotiations (hence higher transaction costs) and, during implementation, to secrecy rather than openness in discussing performance problems and looking for shared solutions.’36

2.46 The evaluation found little evidence that the use of conditionality had been effective in achieving policy breakthroughs in a difficult political environment. On the contrary, it had led to the dialogue processes becoming more formal and legalistic, concentrating on the formulation and interpretation of conditions rather than the underlying policy issues.

2.47 Including a performance tranche in a budget support operation appears only to reinforce this tendency. The amounts of funding at stake for any given target or policy action are not large enough to create a significant financial incentive. There is little sign that financial incentives are effective when dealing with complex institutions, budget processes and political systems. The recipient government officials we spoke to saw the performance tranches either as an unhelpful element of unpredictability in budget support or as donors trying to demonstrate their influence for a domestic audience. One Ministry of Finance official told us: ‘If we started to take the conditionality seriously, that would be bad for our dialogue because we would start to trick each other.’

2.48 We note that performance tranches can have an important signalling effect to the outside world. A well-performing general budget support operation is prestigious for the recipient government, helping it to demonstrate its development credentials to its electorate. It may even help it to attract private investment and access the financial markets. If, however, as often seems to be the case, performance assessments routinely rate government performance as ‘partially satisfactory’ and performance tranches vary only by small sums each year, the signal is not clear enough to be effective.

2.49 Overall, we are satisfied that general budget support is useful as a platform to enable DFID and other donors to engage with recipient governments on high-level policy issues, particularly around the composition of the national budget and the progress of cross-government reform initiatives. DFID plays an important leadership role within these processes, which increases its ability to make a positive contribution to the national development agenda in its partner countries.

2.50 There are, however, some clear limits to the extent of this influence. One is that it does not provide an effective means of engaging with the more complex policy and institutional challenges involved in improving the quality of public services. For this reason, we are unconvinced of DFID’s strategy until very recently of supporting the education sector in Tanzania solely via general budget support. Budget support needs to be complemented by other ways of delivering aid, including not just sector budget support but also technical assistance to specific government agencies. This would enable DFID to work intensively with its counterparts on resolving the bottlenecks to more effective services. As the DFID country programme evaluation for Tanzania pointed out, unless this happens, there is a real risk that the additional public spending generated through budget support will encounter diminishing returns.37

2.51 There is also a danger that budget support processes can settle into a routine and lose their potentially transformative impact. In Tanzania, in particular, our impression was that the budget support operation was mainly serving to keep the development partnership on an even keel, rather than to deliver policy breakthroughs. DFID needs continuously to look for new ways to achieve transformative impact.

Strengthening national accountability

2.52 DFID has recently launched a major new policy initiative on national accountability. The 2011 Strengthened Approach commits DFID to spending an amount equivalent to 5% of budget support on national accountability. There is an Empowerment and Accountability policy team in London and some ’emerging guidance’ on programming.38

2.53 DFID’s investments in national accountability include support for formal accountability institutions (parliamentary committees; supreme audit institutions; anti-corruption commissions) and civil society organisations and processes (e.g. policy-related research and advocacy; budget analysis and tracking). Figure 9 gives an example of a civil society contribution to this debate. DFID is also experimenting with new approaches to citizen empowerment in its sectoral programming. Work with the media (both the traditional media and new or social media) seems to be a relatively neglected area.

‘I like the concept of MDBS [Multi-Donor Budget Support]. I support it in principle because it aims to provide much needed resources for a democratically elected government to fulfil pledges and promises made in its election campaign and which constitute part of its mandate… However, I remain concerned about other aspects of the MDBS. It is irresponsible for donors to write a cheque to a government and then look the other way. There is substantial risk that rather than empower, MDBS resources would be abused by government. This imposes a difficult-to-enforce obligation on donors to ensure that recipient governments are not only democratically elected but that there are adequate mechanisms for domestic civil society to hold government accountable.’

2.54 In Rwanda, domestic accountability has only recently become a specific focus of DFID’s support. Rwanda has strong accountability mechanisms at the centre of government39 but lacks the political space for citizen feedback on government performance. DFID is trialling a community scorecard tool in 190 communities to help them monitor the performance of local authorities.40 This involves encouraging communities to articulate their expectations and opinions of public services and facilitating a dialogue between citizens and local authorities on how to improve them. This welcome approach is a promising one, although it remains at an early stage. DFID Rwanda is currently below the 5% target for expenditure on accountability but has a number of new initiatives in the pipeline.

2.55 In Tanzania, DFID has much larger accountability-related investments. These include substantial support for anti-corruption, the National Audit Office and the electoral process, a media fund and a large civil society grant instrument supporting voice and accountability at both national and local levels. Much of this assistance appears to be quite effective in its immediate goal of building up the institutional capacity and professionalism of individual accountability institutions. It is less clear how this is contributing to the overall accountability of government. The institutions are generally limited to making recommendations to government which, in the absence of a strong democratic process, are routinely disregarded without obvious political cost. DFID’s programming with civil society organisations has strengthened their capacity to engage decision-makers on substantive issues and, to a limited extent, to mobilise public constituencies in support of change. We look forward to seeing whether DFID’s efforts to build more effective civil society organisations will translate into a change in the political incentives facing governments.

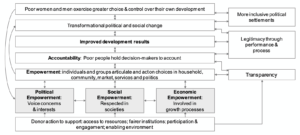

2.56 DFID acknowledges that its programming on empowerment and accountability remains in its infancy and is more driven by theory than evidence. It has launched various processes to strengthen the evidence base.42 At present, much of the programming is based on idealised models of accountability such as the one represented in Figure 10 on page 18, rather than strategies adapted for the political and social context of the countries where it operates. While we welcome DFID’s strong commitment to support national accountability, we see this as an area of programming with considerable scope for improvement.

Source: Empowering Poor People and Strengthening Accountability, DFID, undated

2.57 One of the concerns we encountered among national stakeholders was whether the very strong government-donor accountability within general budget support operations might crowd out or displace national accountability mechanisms. One parliamentarian commented to us that it was difficult for parliament to hold the government to account when the government was more concerned about meeting donor demands. While this concern may be overstated, it is one that DFID country teams should take into consideration in the design of their budget support processes. We saw one good practice example in Rwanda: after each annual performance review, the donors visit the parliamentary Budget Committee to share information on government performance. There may be more scope to share performance information generated within budget support operations with national stakeholders and the public. In this way, budget support would contribute to, rather than displace, national accountability mechanisms.

Impact

Assessment: Green-Amber

2.58 The impact of budget support operations is very difficult to measure. Most of the existing reviews and evaluations focus on intermediate results, such as increases in development expenditure, policy changes and institutional reform. When trying to identify the impact on economic growth and poverty reduction, there are too many variables at play to be sure of what results to attribute to budget support. Overall, we found some evidence of successful policy influence, institutional reform and increased development expenditure across all our case study countries. This was combined with some impressive results on poverty reduction in Rwanda.

2.59 In Pakistan, the first cycle of general budget support corresponded with significant improvements in the national poverty rate, which fell from 32% in 2001 to as low as 17.2% in 2007-08, by some estimates. This was due mainly to a favourable international economic climate and a period of rapid growth in the economy. By the second budget support cycle, the dynamic had changed dramatically. Poverty rates shot up as a result of a series of external shocks, including the global financial crisis and the worst floods in Pakistan’s history. The UK budget support operation can claim some influence over a substantial increase in development spending during its first phase, which rose by 53.6% in real terms between 2004-05 and 2007-08. It was nonetheless unable to overcome significant political and institutional constraints to further progress on poverty reduction. DFID has now discontinued budget support at the federal level, principally because of a constitutional amendment transferring responsibility for most development spending to the provincial level. DFID still has some substantial sector budget support operations in its target provinces which we will review in more detail in a forthcoming Pakistan country programme evaluation.

2.60 In both Tanzania and Rwanda, there have been significant increases in expenditure on development programmes, primarily through the direct financing effect of general budget support. In Tanzania, priority development expenditure (as classified in the national development plan) increased from 27% of the budget in 2004-05 to 46% in 2008-09, without leading to a growth in the debt burden. This enabled a dramatic expansion in the level of service provision in education, health, water and sanitation, infrastructure and agriculture. DFID’s country programme evaluation concluded: ‘It is inconceivable that such a significant contribution to spending in these areas could have been made through other aid modalities.’43 In Rwanda, budget support has financed government initiatives such as free primary education, lower prices for critical drugs, a health insurance scheme for the poor and agricultural loan programmes. In both Rwanda and Tanzania, budget support corrected a historical imbalance in aid flows towards capital over recurrent expenditure.

2.61 Increased expenditure has in turn led to an expansion in public services. In Tanzania, primary school enrolment has risen from just over 70% in 2002 to a high of nearly 95% in 2007, with an extra 4 million children in school (although the figure has fallen slightly since then). This expansion, however, caused class sizes to rise dramatically and pass rates to fall away substantially. The country now faces a major challenge to ensure that those enrolled are in fact receiving a basic education (for details, see our concurrent review on education in East Africa44). Child mortality has declined by 45% over the past decade, due to the increased provision of basic health services including malaria prevention and treatment, immunisation for infants and reduced mother-to-child transmission of HIV-AIDS.

2.62 While these are important achievements, the proportion of people living below the poverty line in Tanzania has declined only marginally since 1991. In fact, due to population increase, during the first six years of budget support, the number of people living below the poverty line increased by over a million, despite cumulative GDP growth in excess of 50%. In the face of continuing acute poverty in rural areas, child nutrition has barely improved, with more than 40% of children showing signs of stunting.45 In short, poverty and inequality have remained stubbornly resistant to the increases in development expenditure.

2.63 Rwanda has also expanded primary education rapidly and is close to achieving both universal enrolment and gender parity but faces a continuing struggle to improve learning outcomes. Unlike Tanzania, however, it has achieved significant breakthroughs on poverty reduction. Repeatedly cited as one of the best performers globally on improving its business environment,46 Rwanda has achieved annual economic growth in excess of 8.2%. Its agricultural programmes have been very successful in promoting higher-value crops and better livestock management, improving household income for the rural majority. Contrary to the predominant trend across Africa, rapid economic growth has corresponded with a reduction in income inequality, apparently as a result of the government’s development programmes. Reduced inequality means that economic growth translates into higher levels of poverty reduction. Between 2006 and 2011, the share of the population living below the poverty line declined from 57% to 44.9%, exceeding national targets and making Rwanda one of Africa’s best performers on poverty reduction of recent years.47

2.64 Rwanda’s impressive record is primarily attributable to the government’s own strong commitment to national development. Given that commitment, however, it is clear that UK budget support (and its leverage of budget support from other donors) has provided the Rwandan Government with the resources it needs to implement its poverty reduction programmes. In this environment of strong national leadership, budget support represents a highly effective means of delivering development results.

2.65 This suggests that budget support can offer good value for money in good policy environments. The picture in weaker policy environments like Tanzania is not as clear. UK budget support has succeeded in expanding expenditure on development programmes and service delivery. In the face of political and institutional bottlenecks, however, it is likely that, above a certain level, budget support encounters diminishing returns. It needs to be balanced with other forms of programming more precisely tailored to addressing those bottlenecks. There may also be a case for exploring non-state delivery of services and development programmes. We note with interest that DFID is supporting low-cost private education in Pakistan, to complement its work with the public system.

2.66 DFID has no explicit exit strategies for its budget support operations, although business cases include a discussion of future programming choices. In both Rwanda and Tanzania, DFID appeared to be operating on the assumption that budget support should continue for as long as the underlying conditions were satisfied. This is a concern, giving the operations the appearance of a permanent subsidy rather than a tool for achieving specific development ends. More thought needs to be given to the question of when countries should graduate from budget support. For the best-performing countries, budget support may continue to deliver good value for money over the long term. For weaker performers, as domestic revenues grow, it may be better to reduce the share of budget support in the country programme. This would allow DFID to devote more resources to helping address institutional bottlenecks to effective service delivery.

2.67 We also note that many African countries are expecting substantial increases in natural resource revenues over the coming years. On the one hand, this lends an urgency to budget support operations. It is important to get budget processes and PFM systems working as well as possible in advance of the potentially disruptive impact of large natural resource revenues. On the other hand, it may also set a time horizon for how long UK budget support will continue to be useful. We also note that the rise of emerging donors in Africa, who provide assistance without the complex processes associated with UK budget support, might create circumstances in which budget support is no longer appropriate.

Learning

Assessment: Amber-Red

2.68 Budget support operations are designed around a continuous cycle of reviewing the recipient government’s performance against its policy commitments. The joint review process collects and analyses results at sectoral and national levels, on an annual or semi-annual basis. In Rwanda, there is also an annual review of donor performance against their aid effectiveness commitments. This provides a snapshot of joint government and donor performance that helps to reinforce mutual accountability.

2.69 As well as making annual decisions on its performance tranches, DFID prepares annual reports on how well each budget support operation is functioning. In the case study countries, there have been periodic external reviews of the quality of the process.

2.70 DFID has been an active supporter of the development of international standards for measuring country systems. This is particularly the case in PFM through the PEFA framework.

2.71 DFID made a major investment in a large, multi-donor evaluation of budget support in 200648 and is a stakeholder for a current multi-country evaluation of European Union budget support.

2.72 We saw various examples of DFID learning from past experience with budget support. The strengthened approach and the new business case procedures have introduced greater rigour into assessing expected results from budget support operations. There is evidence from the case studies of continuous improvements to national dialogue processes and of greater selectivity in PAFs. DFID is currently engaged in a process of collecting evidence on what approaches work best in supporting national accountability.

2.73 There are a few areas where we see a need for more investment in lesson learning. One is in assessing the determinants of effective and efficient public spending. We would expect DFID country teams in budget support countries to be able to list the most important constraints and have an explicit strategy for addressing them. We would also expect more analysis as to what types of accountability already exist within partner countries and how DFID accountability programmes could build on them. This would help to protect against the risk of overly standardised approaches to programming.

2.74 We have some significant concerns about the way DFID reports on results in budget support operations. The practice is to attribute to UK assistance a share of national development results according to what percentage of the national budget comes from UK budget support. For example, in Tanzania in 2009-10, DFID’s budget support was equivalent to 2.3% of the national budget. As there were 8.3 million children in primary school in Tanzania in that year, DFID claimed to have maintained almost 200,000 children in primary school.49

2.75 While we can appreciate the need for a simple way of describing the results for budget support operations, this type of indicator both understates and overstates the impact of budget support. It misses the policy and institutional effects, which in some instances may be as important as the direct financing effects. It fails to capture the additional impact of UK support – namely, how many more children are in primary school as a result of UK budget support. A continuing subsidy to the Tanzanian education system would not in our view represent a development result unless accompanied by improvements to the scope and quality of education provided. It also focusses exclusively on the scope of public services, rather than their quality. In the education field, in particular, expanding the number of children enrolled in primary school does not necessarily equate to the delivery of adequate basic education.

2.76 While it is legitimate to report on the crude financing effect of budget support, the main reporting on results should focus on transformational effects (the changes brought about by UK budget support) and should capture changes in the quality of services provided (real impact on citizens).

2.77 We would like to see more effort made to capture and quantify the impact of budget support on the efficiency of public spending, as this is fundamental to the rationale for budget support. For example, with sufficient investment in baseline data (through sampling in priority sectors), it should be possible to capture changes in the value for money achieved by national procurement systems. DFID could assess whether fiscal transfers to sub-national government have become more targeted on poverty reduction. Through more systematic use of tracking surveys, it should be possible to identify whether there have been increases in the level of capitation grants reaching schools or budget for pharmaceutical purchases reaching medical facilities. DFID could assess changes in the quantity of unproductive spending, such as (in the Tanzanian case) the proportion of departmental budgets spent on workshops and related allowances. One way of approaching this would be to agree a regular cycle of rigorous public expenditure reviews with recipient governments.

2.78 We would also like to see DFID’s reporting on results capturing the combined impact of different aid delivery mechanisms in particular sectors. As we have said, delivering real impact in the social sectors, looking at the quality as well as the scope of services, calls for a combination of budget support and other aid instruments. It would therefore seem appropriate to test whether this complementarity is being achieved by reporting against combined results across a range of interventions – including the extent to which other interventions are enhancing the effectiveness and value for money of UK budget support and vice versa.

3 Conclusions and Recommendations

Conclusions

3.1 Budget support plays an important role in the UK aid programme. It helps to finance the recurrent costs of expanded service delivery, particularly in the social sectors. Where recipient government policy leadership is strong, national systems are sound and budgetary allocations favour growth and poverty reduction, investments channelled through the national budget can represent a relatively efficient way of delivering development resources to the intended beneficiaries. Budget support also provides a high-level platform for dialogue and influence on key development issues, particularly around the composition of the budget and on PFM reform. Where the government is committed to poverty reduction and open to donor input, the dialogue and review processes help to organise the development partnership on a more mature and productive basis, whether at the national or sectoral level.

3.2 There is, however, nothing automatic about these benefits. The practical value of budget support varies substantially, depending on the country context and the dynamics of the development partnership. In more marginal cases, like Tanzania, budget support may help DFID to manage what is sometimes a difficult partnership but is unlikely to deliver transformative impact. We appreciate that DFID has invested a lot in developing its budget support operations. It is important, however, not to get locked in to providing large volumes of budget support where the value is not clearly demonstrated. We are, therefore, pleased to see DFID adopting a more rigorous approach to assessing the likely results of its budget support operations. As more budget support operations go through DFID’s formal business case process, we would hope to see a clearer rationale for the amount of budget support, based on the development value to be gained from expanding public expenditure in the prevailing policy and institutional environment.

3.3 In the East Africa context, budget support has led to an unprecedented expansion in development expenditure and the scope of basic services. This has generated some impressive results, particularly in the health field. The challenge is now to bring the quality of services up to an appropriate level. Unless the political and institutional bottlenecks to improvements in service quality are addressed, the value of further budget support comes into question. New, more hands-on approaches are needed to help partner countries deal with these practical challenges. We would like to see DFID explore new ways of combining budget support with other aid instruments, so as to bring different forms of finance and influence to bear and increase the value of its overall assistance.