The UK aid response to COVID-19

Summary

The initial response of the UK aid programme to the COVID-19 pandemic was rapid, credible and appropriate. It drew on a substantial body of learning from previous crises, particularly Ebola, SARS and H1N1. While the UK government did not have a formal plan or strategy in place for launching an international aid response to a pandemic, experience and the tacit knowledge of staff enabled the early response to be rapid and at scale. The UK government was well informed of the risks and vulnerabilities for developing countries, and international initiatives to limit them. It has continued throughout the pandemic to collect a wealth of detailed analysis of the direct and indirect impacts of COVID-19, including in health, education, violence against women and girls, economic development and livelihoods.

However, while initial decisions taken to reprioritise funding were informed by this analysis, increased pressure on the UK aid budget during the course of 2020 and 2021 meant that a number of later funding decisions did not always reflect the evidence available. This was particularly the case after the reduction of the spending target to 0.5% of gross national income (GNI), when funding stopped for many aspects of the response intended to address the secondary effects of COVID-19. Although the UK government had access to information on the potential negative impact of the budget reduction on vulnerable populations affected by the pandemic, many of the decisions taken as a result of the 0.5% of GNI reprioritisation have inhibited the UK’s continued pandemic response.

Acronyms and glossary

| Acronyms | |

|---|---|

| AMC | Advance Market Commitment |

| BRC | British Red Cross |

| CEPI | Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations |

| DFID | Department for International Development (merged with the Foreign and Commonwealth Office in September 2020) |

| DHSC | Department of Health and Social Care |

| FCDO | Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office |

| FCO | Foreign and Commonwealth Office (merged with the Department for International Development in September 2020) |

| FGM | Female genital mutilation |

| FIND | Fund for Innovative and New Diagnostics |

| Gavi | The Vaccine Alliance |

| GNI | Gross national income |

| HBCC | Hygiene and Behaviour Change Coalition |

| ICRC | International Committee of the Red Cross |

| IDA | International Development Association |

| IMF | International Monetary Fund |

| IFRC | International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies |

| LIC | Low-income country |

| LSHTM | London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine |

| MIC | Middle-income country |

| NGO | Non-governmental organisation |

| ODA | Official development assistance |

| OECD DAC | The Organisation for Economic Co-Operation & Development’s Development Assistance Committee |

| PPE | Personal protective equipment |

| RED | Research and Evidence Division |

| SAGE | Scientific Advisory Group for Emergencies |

| SARS | Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome |

| SDGs | Sustainable Development Goals |

| SMEs | Small and medium enterprises |

| UN | United Nations |

| UNAIDS | Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS |

| UNDP | United Nations Development Programme |

| UNFPA | United Nations Population Fund |

| UNHCR | The United Nations Refugee Agency |

| UNICEF | United Nations Children’s Fund |

| UN OCHA | United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs |

| VAWG | Violence against women and girls |

| WFP | World Food Programme |

| WHO | World Health Organisation |

| Glossary of key terms | |

|---|---|

| Country offices | Legacy DFID offices in bilateral partner countries. |

| COVAX | A global collaboration established in April 2020 to promote equitable global access to COVID-19 vaccines. |

| COVID-19 | The coronavirus disease 2019 is a communicable respiratory disease that spread rapidly around the world from late 2019, resulting in the WHO declaring a pandemic in March 2020. |

| G7 | The Group of Seven are Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, the United Kingdom and the United States. |

| No regrets | A form of decision making that enables planning on the basis of a reasonable worst case scenario and drawing on evidence available at the time to take funding decisions in an uncertain context. No regrets decisions are often seen as worth taking regardless of what scenario actually plays out. |

| ODA | ODA is defined by the OECD DAC as government aid that promotes and specifically targets the economic development and welfare of developing countries. |

| Overseas network | FCDO's diplomatic and development offices worldwide, including overseas embassies and high commissions. |

| Reasonable worst case scenario | Assuming the most pessimistic among the range of plausible scenarios when faced with a high level of uncertainty. |

Executive summary

The World Health Organisation (WHO) declared the COVID-19 outbreak to be a global pandemic on 11 March 2020. Since then, the virus has spread rapidly to almost every country in the world, triggering a global public health crisis on an unprecedented scale. As of 27 September 2021, there had been more than 231.5 million confirmed COVID-19 cases around the world, with nearly 4.7 million deaths. It is estimated that, by the end of 2022, COVID-19 will have reduced the global economy by $3 trillion (approximately £2.2 trillion), the largest global recession since the Second World War (estimated to be more than 3.5% lower than projected before the pandemic).

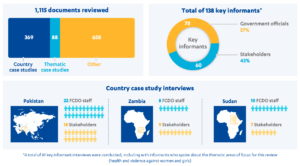

This rapid review explores the UK’s international aid response to the COVID-19 pandemic. It assesses how well the UK government prioritised and redirected its aid resources in the first 16 months of the global response, including at the central level and in three country programmes (Pakistan, Sudan and Zambia). It also looks at the UK aid response to COVID-19 in two thematic areas: violence against women and girls (VAWG) and health. As a rapid review, it is unscored and is intended to inform Parliament and the public about the choices made by the UK government in its aid response to COVID-19 and the rationale behind them. Forthcoming ICAI reviews will explore particular elements of the UK’s aid response to COVID-19 in more depth.

Relevance: How credible has the UK aid response to COVID-19 been so far?

The UK’s aid response during the early months of the pandemic was credible and appropriate. It demonstrated a commendable level of flexibility and a robust approach to risk management, allocating £733 million in central funding by mid-April 2020.

While there was no strategy or blueprint in place for responding to a global pandemic, the response benefited from experience gained during previous health crises, particularly Ebola and SARS. It also benefited from earlier investments in preparedness for health emergencies, including coordination structures, international partnerships and funding mechanisms that could be quickly scaled up.

By March 2020, the government had set clear objectives that provided an organising framework for the international response:

- providing direct support to the most affected developing countries

- supporting the development of vaccines, tests and treatments

- addressing the economic consequences of the pandemic.

While the mechanisms chosen to support vaccine distribution to developing countries are yet to reach the scale needed, we find the initial set of priorities to be well grounded in the evidence available on the pandemic’s likely impact on those countries.

The UK government also identified at an early stage the importance of a coordinated international response, and chose to direct the major share of its resources through the multilateral system. This included unearmarked contributions to global appeals run by the UN and the Red Cross, which provided them with the means to respond flexibly to a rapidly evolving situation.

The responsible departments moved quickly to put in place mechanisms to monitor emerging COVID-19 risks and vulnerabilities. The government made good use of the extensive research capacity in UK-supported institutions and established international networks. The information collected was detailed, providing analysis of likely impacts in areas such as health systems, education, livelihoods and VAWG.

At the country level, UK officials identified which elements of existing aid programmes were no longer relevant or could not be implemented under pandemic conditions and looked for opportunities to repurpose them to support the COVID-19 response. While the full scale of the reprioritisation is difficult to quantify, it appears that a significant quantity of the UK aid programme was repurposed to support health measures, humanitarian aid and social protection for those affected by lockdowns.

The pandemic response coincided with a series of reductions in the UK aid programme, caused first by the contraction of the UK economy and then by the government’s decision to reduce the 2021 aid spending target from 0.7% to 0.5% of UK gross national income. The resulting budget reductions were implemented through three major reprioritisation decisions over the course of 2020. The first two rounds were led by country offices and thematic spending departments, and were generally managed in a way that sought to minimise the impact of the reductions on populations vulnerable to COVID-19. However, the final round of budget reductions, which reduced the UK aid budget for 2021 by an estimated £3.5 billion, did not always reflect the substantial evidence that had been collected on COVID-19 risks and vulnerabilities.

Coherence: How coherent has the UK aid response to the COVID-19 pandemic been so far?

Cross-government structures established before the pandemic helped to coordinate the international response. These included the Scientific Advisory Group for Emergencies (SAGE) and the EpiThreats group, which drew together the scientific and operational capacity to respond to global health threats. The international response was placed at the heart of the UK’s overall planning for the pandemic, providing a link between UK and global institutions. Throughout the pandemic, ministers were well briefed on the emerging situation, with regular interaction with scientific experts.

The March 2020 mandatory return of UK aid staff from many international postings (called a ‘drawdown’) hampered the UK aid response and resulted in the UK being out of step with implementing partners and some other donors. Some UK country offices, such as Pakistan, were exempted from the mandatory drawdown. Many officials interviewed for this review told us that the mandatory approach was unhelpful, and that decisions should have been better tailored to individual country contexts and the personal situations of individual staff. It is notable that some health advisers were drawn down when their knowledge and experience was most needed.

Efficiency: How efficiently did the UK reallocate aid resources in response to the COVID-19 pandemic at the central and country levels?

Over the course of 2020, much of the UK’s in-country aid programming was repurposed to support the pandemic response. In most instances, this was done by pivoting existing programmes to respond to the direct and secondary impacts of COVID-19 and suspending activities that could not be delivered in a COVID-19 context. UK aid officials demonstrated a good level of flexibility and adaptability during the early period of the crisis, facilitated by the high level of delegated authority to country teams.

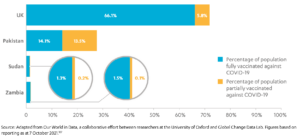

At the international level, the UK government made an important contribution to global efforts to develop COVID-19 vaccines. The UK clearly contributed significantly to an unprecedented level of international cooperation, for instance through its early contributions to humanitarian appeals and funding for COVAX. In June 2021, the prime minister also announced that the UK would donate 100 million doses of COVID-19 vaccine to developing countries. It is not clear, however, how much of the UK’s contribution towards vaccines will qualify as official development assistance (ODA). Plans for the distribution of vaccines have also been disrupted by production and distribution challenges and benefits to developing countries have so far been modest. We find that the UK’s decision to invest in the COVAX facility, established to promote equitable global access to COVID-19 vaccines, was a sound one at the time, but we believe that urgent action will be necessary to ensure that the facility is able to deliver vaccines at scale to developing countries.

The UK’s strong initial response to the pandemic has been undermined by the budget reductions made later in 2020 and in 2021, following the decision to reduce the aid spending target to 0.5%. A number of programmes central to tackling the secondary effects of the COVID-19 pandemic have been reduced or closed, increasing the burden on developing countries and placing vulnerable groups at increased risk. As a result of the ODA reduction, the ability of the UK aid programme to respond flexibly to the evolving pandemic has been reduced.

Recommendations

Recommendation 1

Building on its investments in vaccine development, the UK government should now do more to accelerate the supply of COVID-19 vaccines to developing countries and support their equitable rollout to vulnerable populations.

Recommendation 2

FCDO should delegate as much operational discretion as possible to specialist staff close to the point of programme delivery to ensure the UK’s COVID-19 response is nimble, adaptable and fully informed by the local operating context.

Recommendation 3

FCDO should review and adapt its drawdown strategy to be more clearly differentiated by risk and individual staff preferences to guide repatriation of staff to home countries during future crises.

Introduction

The World Health Organisation (WHO) declared the COVID-19 outbreak to be a global pandemic on 11 March 2020. Since then, the virus has spread rapidly to almost every country in the world, triggering a global public health crisis on an unprecedented scale. At the time of publication, there had been more than 231.5 million confirmed COVID-19 cases around the world, with nearly 4.7 million deaths. It is estimated that, by the end of 2022, COVID-19 will have reduced the global economy by $3 trillion (approximately £2.2 trillion), the largest global recession since the Second World War (estimated to be more than 3.5% lower than projected before the pandemic).

For many of the world’s poorest countries, the pandemic is reversing development gains made over the past two decades. Up to 97 million additional people were pushed into extreme poverty in 2020 and 2021. The UN estimates that 235 million people (1 in every 33 people worldwide) are in need of humanitarian assistance in 2021, through the combination of COVID-19 and other crises. In 2020, the UN launched an unprecedented global appeal for $10.3 billion (£7.6 billion) to respond to the COVID-19 pandemic, covering 63 countries. The global economic crisis has also led to loss of income and sharp rises in debt for developing countries, limiting their ability to invest in their recovery.

The UK was quick to identify that the pandemic would require a significant reprioritisation of the UK aid programme. On 24 January 2020, the UK government started planning its response on a ‘reasonable worst case scenario’ basis – that is, faced with a high level of uncertainty, it assumed the most pessimistic among the range of plausible scenarios. On 15 March 2020, the former Department for International Development (DFID) decided that it would need to reprioritise a significant quantity of the UK’s aid efforts towards the response. By the end of April 2020, £733 million had been allocated from central funds to support the international response, and country offices and spending departments set about redirecting resources from existing aid programmes to address the impacts both of the virus and of measures taken to control its spread in developing countries.

Further reprioritisation of the UK aid programme took place later in 2020, linked first to the contraction of the UK economy in 2020 and then to the reduction of the 2021 aid spending target to 0.5% of gross national income (GNI). The COVID-19 response continued to be a priority for the UK government, alongside ‘bottom billion’ poverty reduction, climate change, girls’ education and Britain as a force for good. In September 2020, the UK government merged DFID and the Foreign and Commonwealth Office (FCO) into the Foreign Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO). This was a major undertaking that has taken up a lot of staff time.

This rapid review assesses the UK’s international response to the COVID-19 pandemic. It looks at how well the UK government prioritised and redirected its aid resources in the first 16 months of the global response, examining how the UK allocated its resources at the central level and in three of its country programmes (Pakistan, Sudan and Zambia). It also looks at the UK aid response to COVID-19 in two thematic areas: violence against women and girls (VAWG) and health.

The review is intended to inform Parliament and the public about the choices made by the UK in its international response to COVID-19 and the rationale behind them. It draws on our 2018 review of the UK aid response to global health threats. It also builds on or complements:

- a November 2020 report by the International Development Committee on the humanitarian impact of the pandemic on developing countries.

- an ICAI information note from 2020 on the procurement aspects of the COVID-19 response

- an ICAI review on the management of the 0.7% official development assistance (ODA) spending target in 2020.

- a planned in-depth ICAI review of the humanitarian aspects of the COVID-19 response.

- a programme of work planned by the National Audit Office to investigate the UK government’s response to the pandemic.

The review questions are set out in Table 1 below.

Table 1: Our review questions

| Review criteria and question | Sub-questions |

|---|---|

| 1. Relevance: How credible has the UK aid response to COVID-19 been so far? | • To what extent did the UK’s ODA response to COVID-19 draw on relevant learning from past global health threats and advance planning for future ones? • How well did the UK government inform itself of the risks and vulnerabilities for developing countries caused by the pandemic and measures to contain it? • To what extent were decisions to reprioritise UK ODA informed by robust assessment of the vulnerabilities and likely impacts of the pandemic on individual countries and regions? |

| 2. Coherence: How coherent has the UK aid response to the COVID-19 pandemic been so far? | • How well did the UK government’s choice of investments, delivery channels and influencing work support a timely and coordinated international response to the pandemic? • How well did the UK government put in place cross- government structures and processes to ensure a coherent and coordinated UK aid response to the pandemic? |

| 3. Efficiency: How efficiently did the UK reallocate aid resources in response to the COVID-19 pandemic at the central and country programme levels? | • To what extent has the UK aid response to the pandemic remained flexible, timely and efficient? • To what extent were programme performance and value for money of existing programmes taken into account during the reprioritisation of funds? • How well did the UK government seek to minimise the potential impact of its reprioritisation in response to the pandemic on planned and current programmes and their target communities? |

Methodology

This rapid review used a mixture of methods to provide robust answers to our review questions and ensure a sufficient level of triangulation. The methodology encompassed five intersecting components:

- Annotated bibliography: We reviewed evidence on the expected impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic in developing countries, including both direct and secondary impacts, and explored global evidence on how to prepare for and respond to pandemics, including relevant learning and evidence from SARS, Ebola and H1N1. We also explored the multilateral response and other bilateral donor responses to COVID-19. The annotated bibliography is published as a separate document.22

- Strategy review: We reviewed the policies, systems and guidance put in place to support the UK aid response to COVID-19. This included a review of UK government architecture, processes and decisions in response to COVID-19, a mapping of financial flows and an assessment of the evidence used to inform decision making.

- Key informant interviews: We interviewed UK officials at the centre of the aid response to COVID-19, including current FCDO staff and former DFID and FCO officials, one minister and implementing partners (including multilaterals, bilateral organisations and civil society organisations).

- Light-touch country and thematic case studies: We looked in detail at the UK aid response to COVID-19 in three countries (Pakistan, Sudan and Zambia) and two thematic areas (violence against women and girls (VAWG) and health). Interviews were held with current and former UK officials, national country partners, other donors and implementing partners. The country case studies were selected to reflect different geographical and operational contexts, including low- and middle- income countries and fragile contexts, and included Sudan as one of only three country programmes to receive an increase in UK aid in 2020. The thematic case studies were selected to explore how UK aid sought to respond to secondary impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic.

- Academic roundtable: A roundtable discussion was held with experts from academic institutions and think tanks working in the field of global health and development. This provided an opportunity for independent reflection and discussion on the UK aid response to COVID-19 so far.

Figure 1: Summary of methodological elements of the review

Figure 2: What we did

Box 1: Previous ICAI recommendations on the aid response to global health threats

ICAI previously considered the UK’s response to global health threats in a review published in 2018, which made four recommendations. The implementation of these recommendations was assessed through our regular follow-up process. The recommendations served as a reference point for this rapid review.

- The UK government should build on the success of the Stronger, Smarter, Swifter framework

by developing a refreshed global health security strategy with a clearer focus on strengthening country health systems, a broader set of research priorities and clearly defined mechanisms for collaboration both across departments and with external actors. The strategy should be published and communicated widely. - The Department of Health and DFID should strengthen and formalise cross-government partnership and coordination mechanisms for global health threats, broadening their membership where relevant. This should include regular cross-government simulations to rehearse how the UK government might coordinate and respond internationally to a future global health threats crisis similar to Ebola, and engage with other actors such as the WHO.

- The government should ensure that DFID has sufficient capacity in place to coordinate UK global health security programmes and influencing activities in priority countries, including around the objective of strengthening national health systems.

- DFID and the Department of Health should work together to prioritise learning on global health threats across government, overseeing the development of a broad evaluation and learning framework, regular reviews of what works (and represents good value for money) across the portfolio, and a shared approach to the training and development of health advisors.

ICAI’s follow-up assessment, published in July 2019, found that a refreshed strategic framework for global health security was under development that would highlight health systems strengthening work and facilitate wider engagement by adopting the internationally recognised ‘prevent, detect, respond’ approach. We also saw improvements in cross-government working and learning in support of the high priority given by the UK government to global health security and found that important learning was taking place on how to adapt global health threat responses to fragile and conflict-affected settings.

Box 2: Limitations to our methodology

COVID-19: The ongoing COVID-19 pandemic has placed restrictions on travel to and within countries that receive UK aid and affected the degree to which face-to-face meetings with programme partners and citizens can be undertaken. Interviews and country visits were therefore conducted remotely, which limited the depth of evidence collection possible.

Time period: The review covers the period from January 2020 to May 2021. Evidence is more limited for issues and challenges emerging in the latter part of the review period. In particular, FCDO only announced full details of its 2021 budget in September this year, following the government’s November 2020 decision to reduce the aid spending target for 2021 to 0.5% of GNI. This announcement came after our review was complete. Some of these issues may be pursued in more depth in forthcoming ICAI reviews.

Background

The COVID-19 pandemic has had unprecedented global impact

On 11 March 2020, the World Health Organisation (WHO) declared the novel coronavirus (COVID-19) outbreak to be a global pandemic. Its impact around the world has been unparalleled in modern times: over 4.7 million people have lost their lives, while the measures taken to reduce transmission have resulted in vast social and economic disruption (often described as secondary or indirect impacts).

The World Bank estimates that the pandemic has pushed an additional 97 million people into extreme poverty, exacerbating inequality. The United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) also estimates that global human development, a measure that includes education, health and living standards, could fall as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic for the first time since 1990, when the measure was first introduced.

The UN has reported that the pandemic has set back progress across the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), including the loss of the equivalent of 225 million full-time jobs in 2020, the first increase in child labour in two decades, and an additional 101 million children falling below the minimum reading proficiency level. Gains in gender equality have also been set back by the pandemic, with women bearing a disproportionate share of job losses. In March 2020, analysis by the former Department for International Development (DFID) identified that COVID-19 was likely to increase the risk of domestic violence, workplace violence in the health sector, and racial and sexual harassment. This has indeed occurred: the UN secretary-general, António Guterres, has described lockdowns as causing “a horrifying global surge in domestic violence” and UN Women has identified violence against women and girls (VAWG) as a “shadow pandemic”. As reported by the International Development Committee, the COVID-19 pandemic has also had a severe impact on health systems globally. An April 2021 WHO survey of member states found widespread disruption to routine immunisations (57% of respondent countries), antenatal and paediatric care (56% and 52% respectively) and intimate partner and sexual violence prevention and response services (39%). Access to education and other basic services has also been severely impacted, with potential long-term consequences. In August 2020, the UN reported that 1.6 billion learners in over 190 countries had been affected by COVID-19, exacerbating existing educational disparities. The UN estimates that an additional 23.8 million children will drop out of school in 2021, with long-term impacts not only on learning but also on access to food and work.

Global humanitarian and financial institutions have mobilised significant levels of support

Early in the pandemic, the international community recognised the importance of supporting the COVID-19 response in developing countries to mitigate both immediate and longer-term impacts. The UN launched an unprecedented global appeal for $2 billion (£1.4 billion) to support the humanitarian response to the pandemic in March 2020. This was later revised upwards to $10.3 billion (£7.6 billion), covering 63 countries. In May 2020, the International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement also launched a collective global appeal, for $3.2 billion (£2.3 billion). As outlined below in Table 2, the UK provided unearmarked contributions to both of these appeals. Initial estimates from the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development’s Development Assistance Committee (OECD DAC) indicate that DAC donors spent $12 billion on COVID-19-related activities in 2020, including both new spending and funds redirected from existing development programmes. While this was a substantial mobilisation of aid, it is a tiny fraction (0.07%) of the $16,000 billion spent by governments globally on stimulus measures to protect their own economies.

In April 2021, the World Bank launched an early 20th replenishment of the International Development Association (IDA-20), the fund that it uses to provide loans and grants to 74 of the world’s poorest countries. The early replenishment process aims to boost the support available to poor countries in their recovery from the COVID-19 crisis and in their transition to green, resilient and inclusive economic development. The IDA-20 replenishment will conclude in December 2021 with a policy and financial package for the July 2022 to June 2025 period. The World Bank Group has also announced up to $160 billion in financing tailored to respond to the health, economic and social shocks that countries are facing, including over $50 billion of IDA resources on grant and highly concessional terms. The UK sits on the World Bank’s governing bodies and is the largest contributor to IDA. ICAI is currently undertaking a separate review of the UK’s support for IDA.

Other global mechanisms have also mobilised finance to help developing countries manage the economic consequences of the pandemic. During 2020, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) temporarily doubled access to its emergency facilities, the Rapid Credit Facility and Rapid Financing Instrument, through which the Fund provides emergency assistance without the need for a fully fledged programme. The UK provides funds to these facilities through a call down arrangement – where the funds are only paid if needed. As of 30 June 2021, the IMF had made approximately $250 billion – a quarter of its $1 trillion lending capacity – available to member countries through these facilities. The IMF has also been approving financial assistance under other lending arrangements, bringing the total number of countries benefiting from emergency finance to 85.

Vaccine development and distribution has been central to the global response

There was early recognition that vaccines would play a key role in the global pandemic response. During 2020, huge international resources were invested in the development of vaccines. The full extent of the investment is difficult to calculate, but one study estimated that governments had spent €86.5 billion (£74 billion) on COVID-19 vaccine development by January 2021. There was also an unprecedented level of international cooperation within the scientific community. The WHO approved the first COVID-19 vaccine for emergency use on 31 December 2020.

At the time of publication, there had been more than 231.5 million confirmed COVID-19 cases around the world, with nearly 4.7 million deaths. To date, however, vaccine rollout has disproportionately benefited developed countries: only 2.2% of people in low-income countries have received at least one dose of a COVID-19 vaccine, compared with 44.5% of the global population.

COVAX is a global collaboration established in April 2020 to promote equitable global access to COVID-19 vaccines by Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance (an international platform that supports routine vaccination in poor countries), the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations (CEPI) and the WHO. It supports the development and manufacturing of vaccines, and equitable and affordable access for developing countries. The concept behind COVAX was that donor countries would purchase a share of their vaccines through COVAX, which then allows developing countries to buy vaccines at cheaper prices. By consolidating the buying power of multiple countries through a single purchasing mechanism, it hoped to be able to negotiate better deals with drug companies than developing countries could have done on their own. It also made early commitments to purchase vaccines before they had received regulatory approval, enabling the drug companies to scale up production at an earlier stage.

COVAX initially aimed to provide enough vaccines for 20% of the population of poorer countries, but has so far been unable to secure vaccines at the scale required. Implementation has been beset by problems, including competition among wealthier countries for vaccines and the Indian government’s March 2021 decision to halt vaccine exports in the midst of a surge in COVID-19 cases in India. Additional funding pledged during the Gavi COVAX Advance Market Commitment (AMC) Summit in June 2021 has enabled Gavi to secure agreements with manufacturers to provide fully subsidised doses to cover almost 30% of the population in 91 AMC countries.

The UK and other G7 leaders have also responded to inequitable vaccine access by pledging to donate an additional one billion vaccine doses from their own supplies to developing countries. However, current supply remains far short of the 11 billion doses that the WHO estimates are needed to vaccinate the world to a level of 70% (the point at which transmission could be significantly affected). Furthermore, many poorer countries need additional support for their national health systems in order to be able to administer the vaccine to their populations.

As a result, the global distribution of vaccines has so far been highly inequitable. The slow rollout will mean that developing countries will continue to face both the direct and the secondary impacts of COVID-19 for longer.

The UK response to the pandemic

In the early months of the pandemic, the Cabinet Office directed every government department to reprioritise their work around COVID-19. In response to this directive, DFID identified that it would need to reorient a significant quantity of its aid efforts to provide urgent health, economic and humanitarian support. By the end of April 2020, DFID had allocated £733 million from central funds towards the pandemic response, much of it through multilateral channels (see Table 2 below). These early allocations were in support of three objectives:

- providing direct support to the most affected developing countries

- supporting the development of vaccines, tests and treatments

- addressing the economic consequences of the pandemic.

Over the course of 2020, DFID/Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO) also reoriented a significant share of their bilateral programming to help countries deal with the multiple impacts of the pandemic.

The pandemic response was carried out during a period of considerable uncertainty for the UK aid programme. The aid budget was substantially reduced, as a result of the contraction in UK gross national income (GNI) in 2020 and then the government’s decision to reduce the aid spending target from 0.7% to 0.5% of GNI in 2021. To achieve these budget reductions, three major reprioritisation exercises were undertaken, described in Box 3. The results of the third phase have not yet been released in full.

Box 3: The three reprioritisation processes for UK aid in 2020

The first reprioritisation process (March/April 2020)

On 24 March 2020, an instruction was issued by DFID’s acting permanent secretary to reprioritise all DFID programmes according to the following criteria:

- Gold (drive): Ministerial priorities including COVID-19 response, economic support and social protection, ongoing humanitarian response operations, preparation for the Gavi Summit and girls’ education.

- Silver (manage): Second-tier priorities to be managed proportionately to ensure programmes stayed on track.

- Bronze (pause): Areas where the department could pause or slow down programmes, in particular areas not related to COVID-19 policies and engagements.

Each spending department identified its proposed reprioritisation, including budget reductions, delays and reprogramming of funds, which were then reviewed at the central level. All new contracting was paused during this time.

The second reprioritisation process (June/July 2020)

In mid-2020, when it became clear that the pandemic would have a severe impact on the UK economy, the government began a second reprioritisation exercise to ensure that the 0.7% spending target was not exceeded. Based on the UK GNI projections available at that time, the prime minister signed off on a package of up to £2.94 billion in-year official development assistance (ODA) budget reductions. We have detailed this process in our report on the management of the 0.7% ODA spending target in 2020.59 An initial set of priorities was drawn up under the direction of ministers, and included the response to the COVID-19 pandemic, supporting manifesto commitments such as climate change and girls’ education, advancing the role of Britain as a force for good (such as promoting media freedom), and support for the world’s poorest countries and people (the ‘bottom billion’).

The third reprioritisation process (November 2020 onwards)

In November 2020, the chancellor announced a reduction in the UK aid spending target to 0.5% of GNI for 2021. The former foreign secretary, Dominic Raab, announced a new strategic framework for ODA management, to replace the 2015 Aid Strategy. Departments were given ODA budget ceilings and invited to make reductions in their programming accordingly, with the final decisions taken by ministers. At the time of publication of this report, the government has not yet published details of the budgetary impacts for individual programmes.

Figure 3: UK official development assistance response to COVID-19

While UK aid as a share of national income remains high by international and historical standards, the most recent budget reductions have reduced UK aid funding by an estimated £3.5 billion in 2021. As a result, the reallocation of UK aid to support the COVID-19 response was later counterbalanced by reductions in funding for related areas, such as support for national health systems and social safety nets intended to protect families from the impact of shock. We examine, where appropriate, the net effect of the reprioritisations on the UK government’s COVID-19 response, including reductions in aid spending in areas intended to address the secondary impacts of the pandemic.

The reprioritisation of UK aid also coincided with the merger of DFID and the FCO into FCDO, which was announced in June 2020 and took place in September 2020. The merger was an important contextual factor, in that the pandemic response was undertaken in an environment of some uncertainty and when officials were preoccupied with planning for and implementing the merger.

The UK government’s Integrated Review of Security, Defence, Development and Foreign Policy, published in March 2021, reaffirmed the UK government’s commitment to an international COVID-19 response. Global health security has also been set as one of seven strategic objectives for the UK aid programme.

Findings

In this section, we assess the relevance, coherence and efficiency of the UK aid response to the COVID-19 pandemic over the period from January 2020 to May 2021.

Relevance: How credible has the UK aid response to COVID-19 been so far? The UK government set clear objectives for its international COVID-19 response

The UK government did not have a strategy or blueprint in place for an aid response to a global pandemic. However, the UK response benefited from a range of prior investments in preparing for global health threats. Over the period from 2015 to 2018, the UK had developed a strategy – Stronger, Smarter, Swifter – to guide preparations for future health emergencies. It had also created a cross-government EpiThreats group, to link up its scientific and operational capacity. As we concluded in our 2018 review, that strategy drew on learning from the Ebola epidemic in West Africa from 2014 to 2016 to provide a relevant and well-balanced framework for action, supported by a strong strategic rationale.

The UK’s response benefited from experience gained during earlier disease outbreaks, particularly Ebola (as mentioned above), H1N1 and SARS.65 Drawing on this experience, UK aid staff in key positions in the UK, Geneva (where the WHO is headquartered) and Department for International Development (DFID) country offices were able to assess the potential consequences of the unfolding crisis for developing countries and identify options for the UK aid response.

In March 2020, an International Ministerial Implementation Group was set up to coordinate the UK’s international response, including through the aid programme. The UK identified at an early stage that the multilateral aid system should be the primary mechanism for responding to COVID-19, not least because of the scale of resources required to respond to the social and economic impacts of the crisis. This objective was affirmed in the government’s May 2020 COVID-19 recovery strategy, which included a section on the international response, with a strong statement of intention to position the UK at the forefront of a coordinated global response. From February 2020, UK officials in Geneva and Washington began engaging with their multilateral counterparts, and DFID’s permanent secretary met with World Bank and International Monetary Fund (IMF) officials to encourage and support their pandemic response.

Initial resources were reallocated quickly and at scale, with most of the central resources allocated for pandemic response in 2020 already decided by mid-April. The UK identified three main objectives for its international COVID-19 response strategy, which guided an initial allocation of £733 million from central funds to the global response (see Table 2). £170 million was allocated from the UK official development assistance (ODA) Crisis Reserve and the balance from reprioritising the UK aid programme. The three main objectives were:

- protecting the most vulnerable countries and populations (40%)

- supporting the development of vaccines, tests and treatments (40%)

- supporting the economic response (20%).

Decisions made in this early period, although taken rapidly, were credible and appropriate, reflecting emerging evidence on the evolving crisis and its likely impact on the most vulnerable populations.

| Focus | Funding stream | Activites | DFID/FCDO funding |

|---|---|---|---|

| Providing resilience to vulnerable countries | World Health Organisation (WHO) | Contributing towards WHO costs in supporting the global response | £75 million |

| United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) | Supporting infection prevention and access to safe water | £25 million | |

| Unilever coalition | Mass communication, product response and digital behaviour change programmes focused on hand and environmental hygiene | £50 million | |

| World Food Programme (WFP) | Unearmarked support to appeal | £15 million | |

| The United Nations Refugee Agency (UNHCR) | Unearmarked support to appeal | £20 million | |

| United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) | Unearmarked support to appeal | £10 million | |

| Red Cross (IFRC/ICRC/BRC) | Unearmarked support to global response | £55 million | |

| Non-governmental organisation (NGO) support | To be determined with NGO partners | £20 million | |

| Finding a vaccine, new drugs and therapeutics | Wellcome, Gates Foundation and Mastercard Therapeutics Accelerator | Accelerating the development, manufacturing and distribution of treatments for COVID-19 in low- and middle income countries | £40 million |

| Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations (CEPI) Supporting vaccine development | Supporting vaccine development | £250 million | |

| Fund for Innovative and New Diagnostics (FIND) | Supporting the development of rapid diagnostic tests | £23 million | |

| Economic response | International Monetary Fund (IMF) Catastrophe Containment and Relief Trust | Helping to mitigate the short-term economic impact of COVID-19 on the most vulnerable countries | £150 million |

| Total | £733 million |

The first objective focused on providing humanitarian support. It consisted mainly of unearmarked support through multilateral mechanisms and established non-governmental organisation (NGO) partners. Those partners that we interviewed confirmed that the provision of unearmarked support was extremely useful, enabling them to respond flexibly to a rapidly evolving crisis. Working through multilateral channels also helped the global response to scale up rapidly.

The second objective consisted primarily of investments to support the development of COVID-19 vaccines and enable their distribution to developing countries. Through its support for CEPI and COVAX, the UK helped to galvanise an impressive level of international cooperation around vaccine development. However, as discussed below in the ‘efficiency’ section, in the face of competition among wealthy nations for vaccines, the COVAX mechanism has not functioned as intended. The supply of vaccines to developing countries has been beset by production delays and distribution challenges, and the global distribution of vaccines has so far been far from equitable.

Overall, we find that the initial choice to invest in an international cooperative platform for vaccine development and distribution was sound, given that vaccination remains the only known route out of the pandemic. However, there are some significant questions around the design of the COVAX mechanism that are beyond the scope of this review to explore, but would merit further analysis. There is also an unresolved question as to what share of the UK’s investment in COVAX will ultimately count as ODA, given that vaccine development benefits both developed and developing countries (see paragraphs 4.57 to 4.62 below), and it is not yet agreed how to value vaccine doses.

The third objective consisted of a £150 million contribution to the IMF’s Catastrophe and Containment Relief Trust, which enables countries hit by catastrophic events, including health disasters, to suspend payments on their debt to the IMF. This has the effect of freeing up national budgetary resources for pandemic response. The pandemic resulted in a sudden loss of income to many developing countries, due to sharp falls in investments, tourism, remittances and commodity exports. While many now face a long-term challenge with debt sustainability, the UK contribution was intended to alleviate budgetary pressure over the short term.

The UK government took early action to inform itself and others of emerging risks and vulnerabilities for developing countries

The UK government quickly put in place processes to monitor evolving COVID-19 risks and vulnerabilities for developing countries. It made good use of DFID’s research base and the networks of its technical staff to ensure access to timely and robust data. Information was drawn together from a wide range of sources, with regular reporting to the Cabinet Office, the National Security Council and the Prime Minister’s Office.

Throughout the review period, the UK government collected a wealth of data and analysis on the direct and secondary impacts69 of COVID-19 in developing countries. The analysis tracked the impacts of COVID-19 in multiple areas, including health, education, violence against women and girls (VAWG), economic development and livelihoods. It identified and monitored particular at-risk groups, such as informal workers who had lost their ability to earn income and children that had lost their access to education. This information was of direct operational relevance and helped to inform decisions by country offices and overseas networks on how to prioritise the response.

The research and analysis were commissioned through several aid-funded channels, including the Global Challenges Research Fund and established resource centres and help desks. It drew on regular situation reports and briefings from DFID/Foreign, Commonwealth and Development (FCDO) humanitarian and economic development teams, the Research and Evidence Division (RED) Science Cell and epidemiological modelling. DFID also made good use of its in-house centres of expertise, including groups led by the DFID chief scientist and chief economist, the governance team and specialist advisers in health, VAWG and other areas, as well as their wider networks.

These multiple sources of data and analysis were reported and collated through DFID’s COVID Hub, which ensured tight management of the information. Central policy teams across DFID then disseminated the information across spending departments, including to country offices. Staff that we spoke to during our country case studies reported receiving a high volume of information, noting that at times this was too much to read and absorb. However, they valued the investment put into understanding the operational context, challenges and impact of the pandemic – knowledge that proved a key strength in the UK’s response.

Information and analysis was also disseminated to other development partners and national governments, and there is evidence that it was used by others to inform their pandemic response. For example, an evidence assessment commissioned through the VAWG Helpdesk on the likely impacts of COVID-19 on VAWG70 was widely circulated and has been cited in strategies and guidance produced by other development partners, including the World Bank71 and the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF).72 UK ODA-funded analysis and modelling on COVID-19, particularly from the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine (LSHTM), was also used by national authorities in our case study countries. In Zambia, for example, LSHTM modelling and mapping of COVID-19 incidence, as well as genome sequencing, helped inform the national response.

Early decisions on reprioritising aid were well informed by the data and analysis available

During the first round of reprioritisation, in March 2020, country offices and thematic programme teams were asked to identify resources that could be reallocated from existing programmes to support the pandemic. In our case study countries, these decisions were based on emerging data and analysis, and involved consultations with key partners.

The DFID Pakistan office recognised in late January that the pandemic would be highly disruptive to existing programmes. Even before any directions had been received from London, staff began engaging with partners to identify opportunities to pivot programmes towards the pandemic response. In Sudan, reprioritisation efforts began with conversations with partners about which elements of existing programmes remained viable in pandemic conditions, and from where resources could be diverted to emerging needs. For example, the Sudan Free of Female Genital Mutilation programme was unable to proceed with many of its planned activities and therefore pivoted to delivering community messaging on COVID-19. A new activity was also added under the Sudan Stability and Growth Programme to support non-state actors in engaging and informing communities on COVID-19 risks.

The value for money risk of not prioritising long-term development while responding to COVID-19 was flagged

By early May 2020, senior managers knew that the combination of the decline in UK gross national income (GNI), unprecedented calls for contributions from international agencies, and what it identified as “huge financing gaps in partner countries” would result in the UK ODA budget being squeezed as a result of the pandemic. Internal documents seen by ICAI show officials in May saying that “a failure to step back and rigorously prioritise” would result in “giving precedence to requests that come early and focusing on ‘what is the best thing to do [to respond to] COVID-19’ instead of ‘what is the best investment given the reality of COVID-19’”.

Senior management in DFID took the view at this point that cost-effectiveness and the UK’s comparative advantage should be a metric for any fundamental reprioritisation of UK ODA, not ‘no regrets’ (which key staff told us drove the immediate response actions). Senior DFID officials identified in principle that in many cases long-term development investments would be the most effective investments even during the time of COVID-19. DFID’s analysis suggested that the reprioritisation should be structured into three ‘buckets’:

- interventions that directly reduced the severity and length of the crisis

- interventions that mitigated the long-term damage caused by the crisis

- good long-term development investments which were not related to COVID-19 but remained highly cost-effective.

The analysis suggested that DFID should only drop good development investments (the third category above) when the long-term benefits of damage prevention (the second category) were greater. Senior officials noted the importance of ensuring that the development needs of countries were met throughout.

Box 4: Pandemic response measures at the country level

Pakistan

DFID/FCDO built on existing programmes and relationships to respond to the COVID-19 challenge in Pakistan, pivoting and adapting programmes across the country portfolio. Approximately £27.1 million was repurposed within existing project-level budgets, a further £29 million was approved as new project funds within existing programmes, and £13.4 million in programme funding was paused as a result of COVID-19. £21 million was committed to the COVID-19 response under the Pakistan Multi-Year Humanitarian Programme, including £4.5 million to the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (UNOCHA) for the Pakistan Humanitarian Pooled Fund for COVID-19 and Flood Response, £5 million to the International Rescue Committee to deliver cash assistance to highly vulnerable populations, £3.4 million to support the Natural Disaster Consortium’s COVID-19 response and £4.6 million to WHO Pakistan to strengthen technical and strategic support to the federal government.

Pakistan’s economic growth portfolio also pivoted to respond to COVID-19. £3.9 million was channelled through the Enterprise and Asset Growth Programme to capitalise on local and global demand for the drug Remdesivir and to support vaccine production capacity. £4 million was also provided through the Financial Inclusion Programme to support development of a COVID Tax Loan Guarantee scheme to provide liquidity to small and medium enterprises (SMEs) and help protect jobs. DFID also pivoted its Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Merged Districts Support Programme, allocating £9.7 million to ensure more targeted support for food security, health and economic recovery. At the time of our evidence gathering, the implications of the 0.5% of GNI reprioritisation were still emerging. The overall budget reduction will, however, reduce flexibility across the country programme, which is expected to impact the continued COVID-19 response.

Sudan

In Sudan, the UK government repurposed £0.8 million of existing project funds and allocated £8.4 million in new project funds within existing programmes to support the COVID-19 response. £5 million was allocated under the Humanitarian Reform, Assistance and Resilience Programme to provide immediate support to the UN’s Sudan COVID-19 Preparedness and Response Plan and a further £320,000 was repurposed under the same programme to fund technical capacity (in other words, staff positions) in WHO Sudan. Although the 0.5% of GNI budget reductions were still being finalised in Sudan at the time of our data collection, we were informed that the humanitarian budget would be reduced in 2021, directly affecting the flexibility of the UK’s continued COVID-19 response.

The UK government’s Sudan Stability and Growth Programme also provided a vehicle for funding the COVID-19 response. Approximately £2.5 million in new project funds was approved under this programme, including £1.5 million through the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) to support a coherent government response to the COVID-19 crisis, £446,000 for community-led research and advocacy to support COVID-19 mitigation in Sudan and £155,000 to support civil society actors working with government and communities to improve risk communication and mitigation. £2.6 million in project funding was also paused in Sudan as a direct result of the COVID-19 pandemic, including projects focused on building the capacity of political parties and strengthening urban water infrastructure.

Zambia

As in Pakistan and Sudan, the UK government pivoted its existing programmes and partnerships to respond to COVID-19 in Zambia. This included working with partners to adapt programme activities and identify areas for supplementary funding. £3.5 million was allocated or repurposed under the Zambia Health Systems Strengthening Programme, including £2 million to the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) to help maintain basic health services by ensuring the availability of essential drugs, sexual and reproductive health commodities and vaccines. £1.5 million in WHO funding was also repurposed to support preparedness, commodities and planning, as well as broader health security work. A second tranche to this programme was not disbursed, however, and the subsequent 0.7% of GNI recalibration resulted in an overall budget reduction of £2.3 million in 2020. Significant reductions were also made to the Tackling Maternal Health and Child Undernutrition Programme during the 0.7% of GNI recalibration, with an additional £257,080 taken out of the programme budget on top of the £3 million budget reduction already proposed by the country team.

Zambia Social Protection Expansion Programme Phase II: DFID/FCDO Zambia adapted their technical assistance to support an adaptation of the social protection programme so that COVID-19 emergency cash transfers could be delivered by the implementing partner to effectively target 58,000 of the most vulnerable urban households. However, they were unable to contribute any funds directly towards the emergency cash transfers as the programme budget saw an overall decrease of £160,000 in 2020 and further reductions in 2021 due to subsequent reprogramming. This went against FCDO’s COVID-19 objectives in the country, which included maintaining existing social protection systems, known to be a critical part of the global COVID-19 response. DFID Zambia’s Private Enterprise Programme also provided support for the economic response, supporting SMEs suffering severe cash distress as a result of COVID-19 while at the same time identifying and supporting businesses capable of responding to new opportunities arising from the pandemic (such as the supply and transportation of health-related goods and services).

________________

The second reprioritisation did not, overall, reduce programming that sought to respond to COVID-19

The second round of reprioritisation undertaken in mid-year to meet the expected reduction in UK GNI was also led by country offices and thematic spending teams, but with the final decisions taken by ministers through a series of ‘Star Chambers’.75 In our case study countries, we were informed that ministers largely took the advice of country offices on where to reduce programming. However, a few decisions – such as budget reductions to social safety nets in Pakistan – did not consistently reflect country office advice and analysis indicating that the activity was important to the pandemic response and a cost-effective long-term development investment. In that instance, the funding withdrawn by the UK was made up by other development partners already active in the sector, while FCDO has continued to provide technical assistance, building on years of UK support for national social protection mechanisms in Pakistan.

Later reprioritisation decisions did not always reflect the evidence available to government

The third round of prioritisation decisions, from November 2020 onwards, were taken in response to the government’s decision to reduce the 2021 aid spending target to 0.5% of GNI. While the COVID-19 response was considered in the prioritisation, the scale and nature of this budget reduction has had the effect of reducing UK aid funding in many areas that were linked to the pandemic response, in particular mitigating the long-term effects of the crisis. These decisions were mostly taken centrally, with overseas networks and spending teams closest to the programmes providing advice. They did not always reflect the substantial volume of evidence and analysis on pandemic-related risks and vulnerabilities that had been collected.

We heard from numerous UK officials, implementers and multilateral partners that UK ODA reduction was likely to inhibit the response to the secondary impacts of the pandemic in multiple ways, as a result both of funding lost from existing programmes and of reduced flexibility to respond to emerging needs. The UK’s decision to reduce support for Syrian refugees in Jordan is one example.76 In 2020, UN agencies had been able to provide social safety nets to refugee families in Jordan to deal with the impacts of COVID-19, especially the lack of informal work. Officials informed us, however, that the reduction of the UK’s 2021 aid budget has resulted in a 27% decrease in UK support to social safety nets in Jordan this year, despite DFID analysis showing that this form of support was both necessary and important for the COVID-19 response among refugee communities, as it mitigated the impact of the crisis and was a cost-effective intervention. Guidance developed by the Chief Economist’s Office in March 2020 recognised that the most vulnerable households are most likely to be affected economically by the COVID-19 pandemic and recommended ensuring access to social safety nets.77 Later (unpublished) DFID guidance, issued in July 2020, similarly recommended maintaining and scaling up social protection systems as part of the UK government’s COVID-19 response.

The UK’s decision to reduce its support to family planning is another example where the need to mitigate the long-term impact of the crisis has not been prioritised. This decision comes at a time when the COVID-19 pandemic has disrupted women’s access to maternity care and reduced access to sexual health services, including access to contraceptives. By March 2021, one year into the pandemic, UNFPA estimated that 12 million women had seen interruption in their access to contraceptives, leading to 1.4 million unwanted pregnancies.78 In April 2021, the UK government announced its decision to reduce funding to UNFPA Supplies, UNFPA’s flagship commodities programme focused on expanding access to reproductive health commodities including family planning and maternal health medicines, by 85%. This decision was taken despite DFID’s own guidance on the secondary impacts of COVID-19 highlighting the risk of reduced access to sexual and reproductive health services and an increase in unwanted pregnancies. The guidance drew on learning from previous epidemics, noting that during the Ebola outbreak in Sierra Leone more women had died of obstetric complications than of the disease itself, and rates of teenage pregnancy had increased by up to 65% in some areas.79 It also notes that many sexual and reproductive health services are highly time-sensitive, with short-term delays having distorting effects on gender equality that can last for many years.

Although the UK prioritised health systems, we heard how decisions made by the UK government in response to COVID-19 did not always reduce the burden on them. Research shows that in areas with significant prevalence of COVID-19, vulnerability to other health conditions also increases. For instance, it is estimated that deaths from HIV could increase by 10% due to interrupted anti-retroviral therapy resulting from the COVID-19-related burden on health systems.81 Tuberculosis deaths could increase by 20% due to reduction in early identification and treatment of cases, and deaths from malaria could be up 36% because of mosquito net distribution campaigns being paused or cancelled.82 Zambian government officials told us that they value the UK’s long-standing assistance for health systems strengthening, including the Zambia Health System Strengthening Programme. As well as supporting the direct response to the crisis, UK aid to Zambia has supported other areas such as sexual and reproductive health, family planning, basic nutrition, malaria control, HIV/AIDS and neglected tropical diseases, both directly and through multilateral partners such as UNAIDS. However, senior officials in the Zambian government told us that the UK’s decision to remove funding for health activities such as neglected tropical disease services and women’s integrated sexual health would place a burden on the health system at a time when it was experiencing unprecedented demand, and would most likely weaken it. We note that the UK also reduced its funding for UNAIDS by 83% from 2020 to 2021.

Further examples of the impact the UK ODA reduction has had on the pandemic response in our case study countries, including the response to secondary impacts of COVID-19, are listed in Box 4 above. We will explore in more depth how the UK supported the pandemic response at country level in our forthcoming review of the UK’s humanitarian response to COVID-19.

Coherence: How coherent has the UK aid response to the COVID-19 pandemic been so far?

Cross-UK government structures established before the pandemic helped with coordination of the response

In its earlier work on preparedness for global health threats, the UK had put in place a number of cross- government structures to facilitate coordination. These included the Scientific Advisory Group for Emergencies (SAGE) and the EpiThreats group, which drew together the scientific and operational capacity to respond to global health threats.

These existing structures played an important role in the early stage of the pandemic response by linking the aid programme to sources of scientific research and expertise. DFID was represented in SAGE through its chief scientist, giving the department access to regular situation reports and the latest scientific analysis. It also placed the international response at the heart of the UK’s overall planning for the pandemic, providing a link between UK and global institutions. According to senior officials familiar with the response, ministers were well briefed on the emerging situation, with regular interaction with scientific experts.

The UK government coordinated its approach to the purchase of personal protective equipment (PPE) and other medical equipment

4.26 As described in a previous ICAI information note on procurement during the pandemic response,84 the UK (like other countries) faced acute shortages of PPE and other medical equipment during the early phase of the pandemic. The government therefore centralised the procurement of PPE and other equipment under the Department of Health and Social Care (DHSC). DFID was directed not to procure COVID-19-related medical supplies directly, to avoid any perception that the aid programme was competing with the UK’s domestic needs. DFID therefore encouraged its partner countries to obtain supplies through multilateral channels, such as the WHO. This was consistent with the position taken by other donors, with the exception of the US, that procurement was best undertaken by the multilateral system.

Joint working was important, but was at times undermined by administrative challenges

Joint working between the former DFID and FCO during the initial response was important, facilitating information sharing and collaborative working. However, the two departments also had competing priorities. The FCO focused heavily on the repatriation of British nationals during the initial months of the pandemic, while DFID was focused on reprioritising its aid programme to respond to COVID-19. We were informed that a number of DFID staff, both centrally and in country, were reassigned away from the aid programme to support consular functions in these early months.

DFID was required to report a range of information through cross-government coordination structures. We were informed that the reporting obligations at times became burdensome, and that the amount of information generated became too overwhelming to be used effectively. DFID and the FCO subsequently set up mechanisms to manage and streamline reporting and information flows.

At country level, additional mechanisms were quickly put in place to manage and coordinate the response, and generally functioned effectively. In Zambia, the Lusaka mission established a crisis team and was holding regular crisis meetings by late March 2020. Roles within the crisis team were rotated as required to ensure a consistent COVID-19 response. In Pakistan, the Pakistan Cross-Mission Leadership Board developed an Integrated Delivery Plan – COVID (IDP-C). This included a set of objectives to guide the COVID-19 response across the mission, with new virtual teams created to support each objective. Across the international network, teams were established to bring together government departments and cross-departmental funds to safeguard UK wider interests, including UK aid programming.

The pandemic response coincided with the merger of DFID and the FCO into FCDO, which was a major undertaking and inevitably competed for staff and management time. We found evidence that this impacted negatively on the pandemic response, primarily through the opportunity cost as staff were drawn into change management processes. There was also a reduction in operational discretion at both central and country levels. Officials reported delays in decision making as a result of the introduction

of new approval processes and structures, and the introduction of individuals into the decision-making chain who lacked experience in aid management.

The mandatory drawdown of staff from country posts hampered the UK aid response to the pandemic

In March 2020, the FCO’s acting permanent secretary, who held duty of care responsibility for all UK government staff posted overseas, mandated the return of UK staff, in a process called a ‘’drawdown’, from 32 countries with a DFID presence. The decision to implement this drawdown was based on a risk assessment of medical services, law and order, the availability of necessities such as food and fuel, and national decisions on border closures. There were options, however, that the UK government did not pursue early enough to overcome challenges that would have allowed UK aid staff to remain in post, including the use of UN flights when commercial flights were not operational (an approach used by some other donor countries and the UN itself). Officials informed us that the UK signed up in May to use the World Food Programme’s aviation platform two months after the drawdown was implemented.

Only a few UK country offices with a DFID presence, such as Pakistan, were exempted from the mandatory drawdown, giving staff the choice of whether or not to remain. In our three case study countries, some implementing partners and some other large donors gave their staff the option of remaining in country, enabling them to retain a presence at this critical time.

The drawdown had a detrimental effect on the UK’s aid response to the pandemic, taking specialist aid staff out of vulnerable countries when their input and decision making was most needed. It reduced capacity at post, increased programme uncertainty and slowed decision making, with one official describing it as a “period of relentless challenge and change”. Internal lesson learning noted, however, that locally employed DFID staff were more able to maintain business continuity than their FCO colleagues since the DFID staff had greater delegated authority. It is also notable that some health advisers were drawn down despite strong arguments from some staff for remaining in post. This decision runs counter to learning from previous global health threats, including Ebola, that highlights the need for swift deployment of experts on the ground. ICAI’s 2018 review of the UK aid response to global health threats also recommended that DFID put sufficient capacity in place to coordinate UK global health security programmes and influencing activities in priority countries.86 In its management response to this review, the government agreed with the importance of supporting this work at country level, stating that it would continue to use its presence in priority countries to support coordination.

Many officials interviewed for this review told us that a mandatory drawdown was not the right approach, and that decisions could have been better tailored to individual country contexts and the personal situations of individual staff. Among staff who returned to the UK, the burden of finding new accommodation and balancing childcare and home schooling proved disruptive to their ability to work remotely. Officials informed us that working under these circumstances had a negative impact on their morale.

Efficiency: How efficiently did the UK reallocate aid resources in response to the COVID-19 pandemic at the central and country programme levels?

The UK aid response benefited from past investments in preparedness for global health threats

The UK government had made a number of prior investments in strengthening key international partners. It had supported the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations (CEPI), a global partnership launched in 2017 to develop vaccines against future epidemics. In 2020, CEPI was one of the founding partners of COVAX,88 an international fund to accelerate the development and manufacture of COVID-19 vaccines and promote access for developing countries. In 2015, the UK established the Ross Fund, which had a budget of £1.1 billion to invest in developing and deploying new medical products (including vaccines, drugs and diagnostics) and included a focus on diseases with epidemic potential. It has also invested in the WHO R&D [Research & Development] Blueprint, an initiative intended to speed up the response to public health emergencies.

According to key stakeholders, investments in global health preparedness had fallen off after 2018, in the face of changing political priorities. However, the groundwork that had been done following the SARS, H1N1 and Ebola epidemics proved an important foundation for the UK government’s COVID-19 response. It meant that the UK was able to draw on well-established international networks, partnerships and mechanisms that could be scaled up rapidly in response to the pandemic.

This was a strong example of the UK implementing the first principle of the 2011 Humanitarian Emergency Response Review (the ‘Ashdown Review’), that the UK should take an “anticipatory approach, using science to help us both predict and prepare for future disasters”.

Efficiency was enhanced by a robust approach to risk management

In the face of considerable uncertainty over the global course of the pandemic, the UK opted for a ‘no regrets’ approach to its initial aid investments in the COVID-19 response. This robust approach to risk management was well understood among the officials we interviewed, and facilitated rapid decision making around the initial response. Indeed, by April 2020, the UK government had already committed £733 million to the international fight against COVID-19, making the UK one of the largest donors in that early phase.

Unearmarked funding through multilateral channels also enhanced efficiency

The UK opted to provide a substantial share of its support in the form of unearmarked contributions to international agencies and appeals (see Table 2 above for details). Multilateral partners informed us that the rapid UK funding enabled an immediate response in the field, including the timely purchase of PPE. The provision of unearmarked support also allowed partners the flexibility to respond to rapidly emerging needs and priorities during the volatile early phase of the crisis. We were informed that the UK was one of few donors to provide this level of unrestricted funding, which was highly valued by multilateral partners, both in the early phase of the response when individual country needs were still being determined and later on, when the resources could be used to support underfunded areas.

The management response was rapid, but at times almost overwhelmed by the challenge

The response was initially rapid and quickly scaled up. DFID issued its first guidance on the use of ODA in response to COVID-19 to other departments on 31 January 2020. On 1 February, it began daily internal COVID-19 updates and on 4 February the first specialist Emergency Medical Team staff91 were deployed overseas. On 10 February, a joint DFID/FCO International Task Force was established, located in the FCO and supported by DFID’s Conflict, Humanitarian and Security Department. The staffing of this team and the DFID COVID Hub was progressively increased through to June 2020. The offices of the DFID chief scientist and chief economist also shifted their activities to focus on generating information for decision making.