The UK’s aid engagement with China (including July 2021 update)

Executive summary

In 2011, the former Department for International Development (DFID) announced its intention to bring bilateral aid to China to an end, moving instead to a new kind of partnership on global development issues. This transition recognised that China had become a major trading partner, investor and donor for developing countries around the world, as well as an important player on global challenges such as public health threats and climate change. In April 2021, the Foreign Secretary announced a cut to bilateral spending by the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO). This note outlines the policy context up until this announcement and the relevant spending from 2015 to 2019.

Since 2015, UK aid to and with China has scaled up again, with a range of other departments and funds using aid to support diverse partnerships between the UK and China in areas of mutual interest. This has resulted in the emergence of a complex mosaic of aid programmes and activities engaging2 China, in order to support its development (which we refer to as aid ‘to’ China), UK-China partnerships on global development challenges (aid ‘with’ China), and work with third countries on their engagement with China (aid ‘on’ China). In 2019, it is estimated that £82 million in UK bilateral official development assistance went towards engaging China. As it is difficult to gain a complete picture from information in the public domain, this information note offers an account of the extent, nature and purpose of UK development cooperation with China, to support informed debate on a controversial topic.

UK aid supports a variety of UK strategic objectives on China, outlined in the National Security Council’s China strategy as well as a number of broader UK development priorities. Aid-funded activities include research partnerships between UK and Chinese universities, technical support for economic development through the Prosperity Fund, climate change mitigation initiatives, health partnerships, small human rights projects, scholarships and British Council programmes on education and culture. The majority of the aid goes to UK research, academic and government institutions engaging China. This included £12.1 million for UK diplomatic costs3 in 2019, on the basis of the government’s judgment that 40% of diplomatic outcomes are aid-related. We were unable to establish the basis on which this judgment was made.

In the last few years, DFID’s engagement evolved from joint projects with China in other developing countries (‘triangular cooperation’) towards dialogue with China about their respective global development policies and supporting independent analysis and advice for third countries on their engagement with China, and this approach is now being taken forward by the FCDO. According to the Chinese stakeholders we interviewed, China welcomes the UK sharing its development cooperation experience. Through its Belt and Road Initiative, China is the largest infrastructure financier in many African and Asian countries. The UK is encouraging China to adopt international environmental and social standards for infrastructure projects and more widely. This will improve their development impact while potentially creating commercial opportunities for UK companies. Health is also a recurring theme of the partnership: the UK is helping China develop its primary healthcare system, while engaging in joint research on antimicrobial resistance. According to UK government officials, this support has also created opportunities for the UK’s health sector worth hundreds of millions of pounds.

China is expected to reach the income threshold to graduate from aid eligibility in the next four to six years. This transition, already approaching, has been accelerated under the UK aid cuts announced on 21 April 2021. We were informed in January 2021 that, so far, there had been little planning for this transition. According to the March 2021 Integrated Review, collaborating with China on global issues, particularly climate change, biodiversity and global health, remains a UK foreign policy priority. The government will need to consider carefully how to manage the FCDO’s transition away from bilateral aid, and any future transition for the aid funded partnerships with Chinese government and research institutions in other departments in an orderly way, as set out in the recommendations to our 2016 review on DFID’s approach to managing aid exit and transition.

Introduction

Cooperation with China is among the more controversial elements of the UK aid programme.5 In 2011, in view of China’s rapid economic growth and rising global power status, the then Department for International Development (DFID) ended its UK bilateral aid in support of China’s development.6 Instead, recognising China’s growing role in other developing countries as investor, trading partner and provider of ‘South-South’ development cooperation, DFID transitioned to a partnership approach whereby aid was used to engage China on global development issues.

However, other aid-spending departments have taken a different path. Since 2015, the Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy (BEIS), the Prosperity Fund and the Department of Health and Social Care (DHSC)7 have all initiated new aid partnerships with China, in areas such as research and innovation, health, climate change and mutual prosperity. Alongside DFID, the former Foreign and Commonwealth Office (FCO) and the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (Defra) also continued to use aid to engage China. As a result, official8 UK bilateral grant aid to China, which remains a developing country and therefore eligible to receive official development assistance (ODA), has scaled up again, reaching record levels in 2019.

The result is a complex mosaic of UK aid spent engaging China, in order to support its development (which we refer to as aid ‘to’ China), UK-China partnerships on global development challenges (aid ‘with’ China), and working with third countries on their engagement with China (aid ‘on’ China). It is difficult for the public to gain a full picture of this relationship from information currently in the public domain.9 The lack of clear information has heightened the concerns of those who believe that the UK should not provide aid to China10 or who fear that the aid is not contributing to poverty reduction,11 which is the statutory purpose of UK aid.

This information note aims to shed more light on the subject by providing an account of the nature and objectives of UK development cooperation with China. Its purpose is to improve transparency and support informed discussion among parliamentarians and other interested actors. It builds on a 2016 ICAI review of DFID’s approach to managing exit and transition in its development partnerships, which included a case study of DFID’s transition away from traditional aid to China.13 This information note will explore how the UK’s aid engagement with China has evolved since then, culminating in the Foreign Secretary’s announcement that ODA for programme activity undertaken by the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office would be cut to £900,000.

ICAI information notes shed light on aspects of UK aid that are of public interest. They are not evaluative, although they may point to issues that would merit further investigation, whether by ICAI itself or by other bodies. This note covers (i) the strategy and objectives of UK development cooperation with China, (ii) a mapping of relevant UK aid spending, (iii) case studies of UK-China development cooperation in particular thematic areas and (iv) a brief overview of the future context for UK aid engagement with China. The information presented here is drawn from UK government statistics, strategies and programme documents, interviews with UK government officials and a limited number of interviews with stakeholders in China, including officials from six ministries, research institutions and independent observers. For reasons of national security, we could not access some government documents and others could not be referenced in this report. We submitted a draft of this report to the government in March 2021, to enable them to check that it was factually accurate. We had asked the FCDO for information on the planned 2021 aid cuts. Unfortunately, the FCDO did not provide us with any information in advance of the Foreign Secretary’s announcement.

Background

China’s rapid development and global rise

China’s economic development is arguably the most dramatic in recent history. Since the 1980s, over 800 million people in China have emerged from extreme poverty, which China claimed in 2020 to have eradicated, although around a quarter of its population still live below the $5.50 a day poverty line. This progress on reducing poverty has been achieved through a wide range of economic and social reforms and rapid economic growth.

Alongside economic development has come growing global prominence. With a population of 1.4 billion, China is now the world’s second-largest economy and produces over a quarter of global manufacturing output. In 2019, it exported $2.5 trillion in goods and had a trade surplus of $430 billion. Foreign exchange reserves of $3.2 trillion have enabled China to become a major global investor. Since 2013, China has invested an estimated $770 billion on transport and connectivity infrastructure in countries with which it is collaborating on the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI).

China’s growing economic power also makes it a key player in international development cooperation. China is the largest trading partner collectively for sub-Saharan African countries20 and for many Asian countries (including Indonesia and Pakistan). China is Africa’s largest financier of construction projects and is thought to be the largest creditor to African countries, fuelling disputed concerns that it uses debt to expand its influence over them. It is both the world’s biggest carbon emitter, in absolute terms, and a world leader in renewable technologies, making it an indispensable partner in the global response to climate change. China is also asserting its growing military power in disputes over contested territories in the South China Sea.

Box 1: The Belt and Road Initiative

Launched by Xi Jinping, the president of the People’s Republic of China, in 2013, the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) is an ambitious strategy to improve connectivity across Asia, Europe and Africa through the construction of transport and other infrastructure – much of it in developing countries. It is a central pillar of Chinese foreign, development and investment policy. As of January 2021, around 140 countries are thought to have signed memoranda of understanding with China to participate in the BRI. While the UK is not one of those, the Department for International Trade has signed an agreement to guide collaboration on infrastructure projects in third country markets between UK and Chinese companies in third countries. There is significant interest in the BRI from UK businesses. For example, in January 2018 Standard Chartered agreed a deal with China Development Bank worth up to $1.6 billion over five years to fund corporate finance projects and trade finance transactions linked to the BRI.

China as an aid recipient

Despite rapid economic growth, China faces major development challenges. Industrial development has been concentrated in coastal and urban areas, leading to slower progress in poverty reduction in rural areas and levels of inequality that are among the highest in the world. It faces serious public health challenges from a high burden of non-communicable diseases. Environmental degradation is a major concern, with 48 Chinese cities featured among the 100 across the world with the worst air quality. China also faces significant governance challenges, with high levels of corruption, weaknesses in judicial process, constraints on freedom of expression and human rights abuses, most prominently in Xinjiang, Tibet and Hong Kong.

Under current Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) rules, a country is no longer eligible for ODA once its gross national income (GNI) per capita has passed the threshold of $12,535 for three consecutive years. Given that China’s GNI per capita was $10,410 in 2019, it is currently ODA-eligible but is likely to cross the eligibility threshold within the next four to six years.

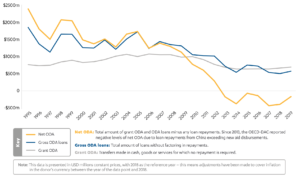

Net ODA from OECD countries to China has declined since the early 1990s, when it was almost $2.5 billion annually, and turned negative in 2013 due to loan repayments exceeding new disbursements. ODA grants to China peaked at $1.2 billion annually during the period from 2004 to 2008, before stabilising at around $600 million since 2013. ODA loans to China averaged around $1.4 billion annually between 1995 and 2008, before stabilising at around $500 million since 2017 (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: OECD Development Assistance Committee (DAC) ODA to China

Germany is by far the largest OECD donor to China, providing $522 million in net ODA in 2019, and is the only country currently providing more grant aid to China for development projects39 than the UK, at $92 million in 2019. Since 2009, Germany has ended its traditional bilateral aid to China and focused on building partnerships on global development issues and areas of mutual interest. Both Germany and France also provide concessional development loans to China.

China’s development finance

China is also a substantial provider of development finance, a role it has been playing since the 1950s. Chinese aid – which it describes as ‘South-South cooperation’ – has increased rapidly since the mid2000s and in 2019 was estimated to have reached $5.9 billion, making China the seventh-largest donor country. In 2018, the Chinese government established the China International Development Cooperation Agency (CIDCA) from the structure of the Ministry of Commerce’s (MOFCOM) Department of Foreign Affairs, which was separated from MOFCOM. While CIDCA now oversees project policy and approval, MOFCOM still oversees project implementation.

China’s approach to aid is distinctive in a number of ways. In 1964, China set out eight basic principles of foreign assistance, which still drive Chinese aid today. They include mutual benefit, non-interference, solidarity and South-South collaboration. China also combines its grants with other forms of official finance, investing in sectors such as infrastructure, natural resources and manufacturing. China has a complex architecture of institutions involved in managing these investments, including state-owned policy banks.

In January 2021, China published a white paper entitled China’s International Development Cooperation in the New Era. It includes new emphases on cooperation with multilateral agencies, delivering global public goods and supporting the Sustainable Development Goals. It identifies the BRI as a commercial component of China’s international development cooperation.

The history of UK-China development cooperation

The UK’s development partnership with China has evolved through a number of phases over the past 15 years. DFID first signalled its intention to end traditional aid to China in 2006 and began exploring the possibility of collaborations with China on development in third countries (‘trilateral cooperation’). The department began to scale down its bilateral aid to China in 2009-10, contributing to total UK bilateral grant ODA to China falling from £49 million in 2009 to £15 million in 2011 (see Figure 2). DFID formally ended its aid for China’s development in 2011, in accordance with government policy, following strong media criticism of aid to growing powers such as China and India. However, rather than ending aid engagement, DFID transitioned towards a new partnership with China, involving ‘trilateral cooperation’ and collaboration on global development issues such as climate change. Our interviews suggested that Chinese partners were interested in using trilateral cooperation to deepen their knowledge of other developing countries and learn from the UK’s experience as a development partner.

A new era of UK engagement began with the then prime minister David Cameron’s state visit to China in 2013 and his proclamation of a ‘golden era’ of trade and investment relations with China in 2015. In support of this engagement, a number of other UK departments began providing aid to China, most of which also pursued benefits for the UK as a secondary objective, a goal DFID was not suited to pursuing given its departmental focus on reducing poverty. This included programmes through the Newton Fund (established in 2014) and the Global Challenges Research Fund (2016), overseen by the Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy (BEIS), which supported UK organisations in developing research and innovation partnerships in China. These partnerships were welcomed by the Chinese partners we interviewed as helping China draw on valuable UK expertise. The Prosperity Fund was launched in 2016 to promote inclusive economic development in middle-income countries, overseen by the National Security Council, with China as its largest planned programme (see Section 4 below).

With more UK departments involved, UK bilateral aid to China began increasing again from 2014. In 2019, officially reported levels of bilateral grant ODA to China reached £68.4 million, their highest recorded level in real terms (see Figure 2). Bilateral ODA was also provided to China through the loans and equity investments provided by UK’s development finance institution, the CDC Group, until it ended new operations in China in 2014.

A new memorandum of understanding on development cooperation was agreed between the two countries in 2015, with the stated aim of refocusing the partnership around global development, with fewer sectors of engagement. The engagement has also been shaped by annual high-level dialogues between the governments, including on economic and financial issues (since 2008), energy (since 2010) and health (since 2013). From 2016, DFID led on organising an annual UK-China Development Forum, focused on global development issues. The Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO) convened the latest forum in December 2020. It announced it would cut ODA for programme activity to £900,000 in April 2021.

Figure 2: Official UK grant ODA to China and key moments in UK-China aid engagements, 2005-19

In our 2016 report on DFID’s approach to managing exit and transition, we noted that the publicity that had been given to ending DFID aid for China’s development in 2011 had potentially created the impression that all UK aid for China was being phased out. Against that background, we concluded that the reasons for continuing and then scaling up UK aid to China had not been adequately communicated to the UK public.

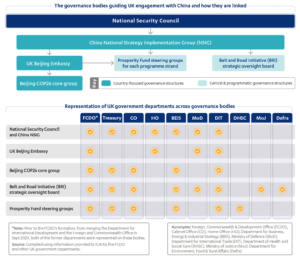

UK government strategy and architecture

There is no single purpose for UK development cooperation with China. Instead, it is one among the various tools used to deliver a range of strategic objectives defined by the National Security Council (NSC), which is the cabinet committee responsible for foreign policy and national security matters, chaired by the prime minister. The NSC sets thematic and geographic strategy, including on China, covering the depth and breadth of UK-China engagement and China’s growing global role. While the strategic approach to China is not public, government evidence to the UK Parliament states that it covers the following seven broad thematic areas of focus:

trading safely to ensure maximum economic benefit to the UK while protecting national security

- China’s global role and the rules-based international system

- countering security threats

- Hong Kong

- human rights

- people-to-people links

- digital and technology.

Supporting these areas of focus is a further cross-cutting strand, to increase capability and expertise on China across government to support all thematic areas of focus.

The government’s strategic approach to China is underpinned by detailed interdepartmental implementation plans, which are used to monitor and direct progress through meetings of the China National Strategy Implementation Group, chaired by the deputy national security adviser. Some of the implementation activities involve spending that falls within the ODA definition, such as technical assistance and funding for development-related research. The FCDO informs us that UK aid is used to support all but one of the seven thematic NSC areas of focus for China.

A number of other UK government bodies have a role in UK aid engagement with China, with associated strategic objectives. These include:

- UK embassy, Beijing: Led by the UK ambassador to China, the embassy coordinates and ensures coherence of departmental activity (including the work of four other offices in China55 which, together with the embassy, form the ‘China Network’) in pursuing the UK’s strategic objectives. Its 2019-20 China Network Business Plan focused on ten objectives, including sustainable and inclusive growth in China, global public goods (including climate change and health), China’s role on development and health security in Africa, China’s role in the rules-based international system, reform, human rights and UK values, and educational and cultural collaborations. The business plan was refreshed in May 2020 and now includes a stronger emphasis on global health and tackling climate change among its headline objectives.

- COP26 China group: To support strategic engagement with China ahead of COP26 – the next UN climate conference, which the UK will co-host with Italy in 202156 – the UK embassy in China has convened a COP26 core team. The UK’s COP26 China strategy focuses on objectives around achieving ‘net zero’ emissions, green growth, nature and the role of China in UN Framework Convention on Climate Change processes.

- Belt and Road Initiative strategic oversight board: This body was established in 2017 to monitor developments around the BRI and to support a coordinated response from the UK. The board meets quarterly and is supported by a working group. The board aims to promote adherence to UK strategic priorities and approaches among departments engaging with the BRI, including the need to support positive development outcomes, support social, labour and environmental standards, increase transparency and promote debt sustainability.

- Prosperity Fund steering groups: Each of the Prosperity Fund programme strands has its own steering group of officials from across government, who advise on and help monitor ongoing programme delivery. These steering groups generally involve officials from the FCDO (previously DFID and the FCO), the Department of International Trade and others.

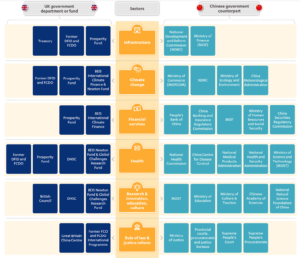

Figure 3: The governance bodies guiding UK engagement with China

UK-China development cooperation

To gain a full picture of the UK’s aid engagement with China, it is necessary to look at a number of categories of statistics.

First, there are official statistics on the UK’s bilateral aid to China. These are generated from information reported by departments on aid spent to promote China’s development and in accordance with the international rules on aid reporting. The reporting is overseen by a dedicated Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO) (previously the Department for International Development (DFID)) statistics team and has become increasingly detailed in recent years.

However, these official statistics only provide a partial view of UK bilateral aid to China. A second portion is spent through multi-country programmes, for which spending is not reported separately by country. We asked aid-spending departments to calculate this amount, to the best of their ability.

A third portion is the UK’s multilateral aid that goes to China. An estimate of this is included in the aid statistics, although for reasons set out below it is only an approximate figure.

For the purposes of this review, we are also interested in a fourth category: UK aid spent engaging with China on global development issues, or working with third countries to support their engagement with China, which we describe as UK aid ‘with’ and ‘on’ China, respectively. Appropriately, neither of these categories are reported as aid to China in the statistics, because their purpose is not to support China’s development.

In this section, we present an overview of the UK’s aid engagement with China across departments and funds, and how this relates to each of these four categories.

Overview of UK aid spending engaging China

According to official UK bilateral aid statistics, the UK spent £68.4 million on aid to China in 2019, up from £44.7 million in 2015. Table 1 presents the breakdown of this aid by department or fund over the period from 2015 to 2019. A detailed mapping is provided below (see 4.15 onwards). Just over half of UK aid to China reported during this period was reported by the Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy (BEIS) and spent through the Newton Fund. The former Foreign and Commonwealth Office (FCO) was the next largest spender, at just over a third of the 2015-19 total, followed by the Prosperity Fund, at around 10%. The Department of Health and Social Care (DHSC) and the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (Defra) reported smaller amounts. Over this period, DFID did not report aid to China, which had come to an end in 2011.

Table 1: UK aid ‘to’, ‘with’ and ‘on’ China by department/fund, 2015-19

| Official UK bilateral ODA to China | UK bilateral ODA to China spent through multicountry programmes | Bilateral ODA 'with' and 'on' China |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Department | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2019 (estimate) | 2019 (estimate) |

| BEIS (Newton Fund) | £18.1m | £26.3m | £24.4m | £34.7m | £33.0m | ||

| BEIS (i) GCRF and (ii) climate finance programmes | (i) £3.4m; (ii) £1.3m | ||||||

| Former FCO,*including: • British Council • Chevening Scholarship • Frontline Diplomatic Activity • International Programme • Great Britain China Centre | £26.3m | £12.9m | £11.7m | £14.4m | £28.1m | ||

| Prosperity Fund | £7.6m | £6.6m | £4.2m | £7.3m | |||

| DHSC | £0.9m | £2.2m | £4.8m | ||||

| Defra | £0.3m | £0.2m | £0.3m | £0.09m | £0.03m | ||

| Former DFID (i) China office and (ii) centrally managed programmes | (i) £1.7m;† (ii) £2.1m |

||||||

| Total | £44.7m | £47.0m | £43.9m | £55.6m | £68.4m | £4.7m | £8.6m |

Most of this aid (at least 68% in 2019) to China was given to UK research and government institutions working in or with China. Grants from the Newton Fund for research partnerships between the UK and China (£33 million in 2019) went almost entirely to the UK partner organisations (universities and research institutes), with the Chinese government providing ‘matched funding’ to the Chinese partners. The FCO’s reported aid to China in 2019 included £12.1 million for ‘aid-related frontline diplomatic activity’, based on its assessment that 40% of diplomatic costs are aid-related and can therefore be charged to the UK aid budget on the basis of international aid rules (see Table 3). The FCO’s work with China through the Chevening Scholarship programme also channels most of its aid spending (£1.7 million in 2019) to British universities to cover the costs of scholarships for Chinese students.

We identified an estimated additional £4.7 million in UK aid spent in China through multi-country climate finance and research programmes overseen by BEIS (see Table 1).

Finally, we identified an estimated additional £8.6 million in UK bilateral aid spent in 2019 to collaborate ‘with’ and ‘on’ China on development issues in third countries or at the global level, through DFID’s China office programmes, some DFID centrally managed programmes and DHSC (see Table 1).

Overall, we calculate that UK bilateral aid engaging China totalled around £82 million in 2019. In showing the full picture of UK aid to and with China we are not suggesting that the aid statistics are inaccurate. The same exercise would be needed to calculate total UK aid engaging any country.

UK aid to China also went towards projects that engaged Chinese partners through training, technical support, research, advocacy – including an emphasis on securing secondary benefits to the UK (the Prosperity Fund) – and promoting the UK’s ‘soft power’ (FCO support to the British Council for educational and cultural collaborations (see Table 4)).

UK multilateral aid to China

UK aid statistics also estimate the amount of aid provided to China through the UK’s core support for multilateral organisations. These organisations record their spending by country and a share of this is imputed to the UK. However, due to some multilaterals not reporting detailed data to the OECD and the specific methodology used for this calculation, these figures are only approximate.

In 2019, imputed UK multilateral ODA to China was estimated to be £4.4 million, down from £11.2 million in 2015. Most of this ODA was channelled through the Global Environment Facility (GEF), but it also included (declining levels of) aid spent through EU institutions and some modest spend through the UN system.

Table 2: Imputed multilateral share of UK aid to China

| 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 |

| £11.2m | £9.8m | £6.2m | £6.1m | £4.4m |

Mapping bilateral UK aid by department and fund

This section presents an overview of the main departmental portfolios of UK bilateral aid spending engaging China, which sit under the six departments/funds who oversee ODA spending. Eleven distinct portfolios are identified, and for each the levels of spending, the types of programmes and partnerships and other important characteristics are presented. Unless stated, these portfolios involve official bilateral aid spending in China, and tables are presented to illustrate statistics for portfolios not already detailed in Table 1.

BEIS – Newton Fund and Global Challenges Research Fund

Background

BEIS oversees the work of two ODA-funded research innovation funds, the Newton Fund (established in 2014) and the Global Challenges Research Fund (established in 2016):

- The Newton Fund was initially designed (in 2013) as a non-ODA fund promoting research and innovation partnerships in emerging economies. Since its repurposing as an ODA fund in 2014, its official primary objective has been producing knowledge and technologies that will support poverty reduction, and its secondary objectives focus on strengthening the UK’s ‘soft power’, global leadership on development research and cooperation and trade. The Newton Fund’s China programme is called the UK-China Research and Innovation Partnership Fund, and it is its biggest country programme. The Newton Fund channels its funding almost entirely through UK research institutions, with Chinese partners funded through matched funding.

- The Global Challenges Research Fund (GCRF) was established to promote research collaborations on global challenges with research partnerships led primarily by UK institutions. Projects on China are delivered largely through multi-country programmes where spending is not disaggregated by country, so are not reported in official UK bilateral aid figures as spending to China, but do in actual fact fall into the same category of spending (see Table 1).

Based on a new policy applied from April 2020, both the Newton Fund and the GCRF are placing renewed emphasis on their spending on partnerships with Chinese organisations focusing on achieving global development impact, for example focusing on global public goods such as climate mitigation.

Main partners

The overarching relationship is managed through China’s Ministry of Science and Technology, with a very wide range of academic and research institutes involved in partnerships.

Project focus

At least 330 projects have been funded by the Newton Fund, on a wide range of topics. The largest partnership is the Climate Science for Service Partnership Programme (CSSP), which supports a collaboration between the Met Office and its counterpart in China on climate science issues. The GCRF has funded over 30 projects in China, focusing mostly on health issues.

Impacts

ICAI reviews on both the GCRF66 and the Newton Fund identified concerns about both funds’ emphasis on assessing impact based on academic metrics (such as articles published) rather than development ones. We did, however, come across some development-related impacts being achieved, including research on antimicrobial resistance (AMR) leading to a ban on antibiotics being used for animal feed in China, and the CSSP helping to improve water management along the Yangtze river.

Former FCO – frontline diplomatic activity

Table 3: Frontline diplomatic activity reported as ODA in China and share of total diplomatic costs

| 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| £8.7m | £9.1m* | £9.3m* | £13.2m* | £12.1m | |

| % of diplomatic costs | N/A† | N/A† | 31% | 40% | 40% |

* In these years, this spending was not reported in official statistics on UK bilateral aid to China but included as part of UK regional ODA spend in Asia

† This data was not made available to the review team

Background

The former FCO’s costs related to diplomatic staff assigned wholly or in part to aid related duties are reported as ODA, and referred to as frontline diplomatic activity (FDA). The UK has reported these costs as ODA since 2011, initially on the basis of staff activity reporting, which resulted in 31% of diplomatic costs in China being reported as ODA in 2017. From 2018 a figure for the proportion of diplomatic activity that was aid-related was calculated by individual diplomatic posts through the business planning process, and agreed to be 40% for China. This proportion of all categories of diplomatic costs that are ODA-eligible has since been reported as FDA. However, limited detail was shared with us on how this FDA percentage was calculated, and we have not been able to determine the specific thematic areas, activities or staff it relates to.

Focus

The FCO’s China Network Business Plan identified diplomatic activity related to ‘grand challenges’ (such as emissions reductions, AMR and healthcare) and ‘global challenges’ (such as green finance, debt sustainability and the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank) as ODA-related, and ‘foreign and security policy’, ‘reform, human rights and values’ and ‘serious organised crime’ as partially ODA-related.

Impacts

There is no separate reporting of the results emerging from FDA, as these are overhead costs which support the whole of government in its ODA delivery and are only the portion of administrative spend not captured elsewhere. Given that FDA constitutes around 20% of UK ODA to China, formally reporting on its impacts would help the government to be accountable for this ODA.

Former FCO – British Council

Table 4: British Council ODA spend

| 2016-17 | 2017-18 | 2018-19 | 2019-20 |

|---|---|---|---|

| £7.0m | £11.4m | £10.0m | £10.8m |

Background

The British Council is a non-departmental public body overseen by and operating at arm’s length from the FCDO. Its ODA spending is focused on educational and cultural collaborations to pursue mutually beneficial outcomes for both countries, and it is seen as an important tool for ‘soft power’ by the UK government.

Main partners

The British Council has partnerships with many Chinese stakeholders on its ODA funded work – its key counterpart on the education portfolio is the Ministry of Education and on cultural activities it is the Ministry of Culture and Tourism.

Project focus

ODA collaboration is focused on two sectors: i) education, including higher education partnerships, inward and outward mobility, education services, gender, youth and schools, and sport (including a partnership with the English Premier League)74 and ii) arts and culture, including international exchanges, cultural heritage development, craft partnerships, and exchanges.

Impacts

Educational programmes were reported to have built sustainable, long-term partnerships between UK and Chinese educational institutions, with significant benefits also flowing to the UK’s tertiary education sector. A cultural programme advised China on the first deaf-led film and arts festival in 2017. In some cases, development and UK interest outcomes were hard to disentangle.

Prosperity Fund

Background

The Prosperity Fund was launched in 2015 to promote sustainable economic development and poverty reduction in middle-income countries. The Fund also has an explicit secondary benefit goal of promoting global business opportunities, including for the UK. The Fund has a global budget of £1.22 billion over 2015-22 and is overseen by the National Security Council. The early phase of the Fund involved small-scale projects managed directly by the Fund, with multi-year programmes launched in 2018-19 and overseen by external implementing partners.

Main partners

These include the China National Development and Reform Commission and the main ministries relevant to each sector programme, such as the National Health Commission, the National Energy Administration, the Ministry of Ecology and Environment, the Ministry of Finance, the Ministry of Commerce and the Ministry of Education.

Project focus

There are currently five programme strands being implemented; business environment, financial services, energy and low carbon economy, infrastructure and health. Work on two additional programme strands – skills and global partners (programmes for building the capacity of Chinese civil servants) – was discontinued in 2020 due to strategic reprioritisation and budget cuts. All of these programme strands are focused on collaborations in China, except for the infrastructure strand, which focuses mainly on influencing the activities of Chinese companies in third countries.

Impacts

The Prosperity Fund’s multi-year programmes are still at a relatively early stage of implementation, and primary purpose results reported to date are largely focused at the output level (for example, training provided and research undertaken). The energy and low carbon economy strand is reported to have helped support China’s commitment to achieve net zero emissions by 2060. The Prosperity Fund has also promoted secondary benefits to the UK, especially through the health strand (see Section 5), and through supporting the trading of China’s currency and the issuing of Chinese bonds in the UK, as well as through promoting infrastructure collaborations.

Former Department for International Development

Table 5: Former DFID China office ODA spend

| 2015-16 | 2016-17 | 2017-18 | 2018-19 | 2019-20 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| £8.1m | £7.4m | £5m | £2.8m | £1.7m |

Background

Since 2011 DFID’s China engagements have been focused primarily on using aid to partner ‘with’ China on global development issues, but have also supported third countries and other actors to engage more effectively ‘on’ China’s development role and impact.

Main partners

These include the Development Research Center of the State Council, the Ministry of Commerce, the Ministry of Finance, the Ministry of Environment and Ecology, the National Forestry and Grasslands Administration, the National Health Commission and a range of UK and international research organisations.

Project focus

Following the 2011 transition to a global development partnership, DFID’s focus was primarily on trilateral cooperation projects on agriculture, community-based disaster management and health. Current projects focus on collaborations with the Chinese government on aid and development policy, research on China’s global development impact and forest governance.

Impacts

DFID support is reported to have helped China’s Development Research Council to launch and develop the Center for International Knowledge on Development and supported the introduction of new laws regulating the timber industry.

Other departmental portfolios

In addition to these larger aid portfolios engaging China, there are a number of more modest-sized portfolios of aid programmes supporting collaboration with China, as illustrated below:

FCO/FCDO – International Programme

This is a portfolio of small projects, with an overall budget of around £1 million. These projects are focused mainly on rule of law and democracy issues, but also maritime security and global peace, security and governance. Projects have helped to highlight concerns about human rights in Xinjiang, highlight issues around freedom of speech and press freedoms, and input to maritime confidence-building in the South China Sea.

FCO/FCDO – Great Britain China Centre

Through £0.5 million of grant funding annually and additional project funds, the former FCO has been partnering with the Great Britain China Centre – a nondepartmental public body established in 1974 – to advance the UK’s interests with China through political dialogues, legal exchanges and capacity building on issues related to judicial reform and the rules based international system. Projects are reported to have led to practical improvements to policies and practices related to pre-arrest detention and access to legal defence support.

FCO/FCDO – Chevening Scholarships

Chevening is a global scholarship programme overseen by the FCDO. Chevening scholars are selected based on their motivation to develop their career in order to establish a position of leadership in their own country, and all candidates commit to returning home for a minimum period of two years following their award. Since 2015 Chevening has supported 328 Chinese scholars, and China has the largest alumni network of all its country programmes. In 2019 Chevening reported ODA spending of £1.7 million.

BEIS – International Climate Finance (ICF)

This is a portfolio of climate change mitigation projects spending an estimated £3.3 million (largely grants) to engage China during 2015-19, but not reported as UK bilateral aid to China (as they are delivered mainly through multi-country programmes). Projects focus on issues such as carbon capture, usage and storage, emissions trading, green finance and energy sector transition. Programmes are mainly implemented by multilateral institutions, which are able to pool funding from a range of donors and contribute niche expertise, although BEIS ICF has one bilateral technical assistance programme working in China, focused on green finance. Projects are reported to have helped support the alignment of China’s green finance standards with international best practice, promote the phase out of coal and feed into China’s ‘net zero’ policy.

DHSC – Global Health Security and Global Health Research

DHSC is supporting a range of research programmes engaging with China, spending around £2 million of ODA annually. On global health security, DHSC is supporting research by UK institutions through its Global AMR Innovation Fund, with Chinese partners supported by the Chinese government. Global health research programmes involving Chinese institutions focus on issues such as salt consumption, road safety, vaccine development and atrial fibrillation. DHSC views its research projects with China as supporting global public goods (in other words, research with global application), and since 2019 it has not reported these as spending in China.

Defra – Darwin Initiative and Illegal Wildlife Trade Challenge Fund

These funds spent less than £100,000 of UK ODA on China in each of the last three years. They mainly engage on issues related to the illegal wildlife trade, for example demand emerging from China for illegal wildlife products.

Thematic case studies

This section presents analysis from three thematic case studies, which explore areas of engagement with China that involve multiple departments collaborating and combining programmatic activity with influencing objectives. These case studies aim to provide a richer description of where and how UK aid works with China, and focus on the most substantive areas of UK-China aid engagement and on areas where improving public knowledge would be of value.

DFID’s Global Development Partnership with China

The Department for International Development’s (DFID) engagement with China on third countries and global development issues, which began in 2011, is referred to as its ‘Global Development Partnership’ with China. To support this partnership DFID has maintained a China office, staffed with 10 to 12 people.

This partnership initially involved a significant focus on ‘trilateral cooperation’. However, in recent years trilateral projects have been less actively pursued, due primarily to a shift in DFID priorities in favour of policy dialogue on global development issues. Chinese partners we interviewed also suggested that these projects did not always meet their expectations. In this initial phase of the partnership, DFID also funded work on forest governance, commissioned research into China’s global development impact (as a public good and to support partner countries), supported UK non-governmental organisations operating in China and engaged in policy dialogue on development issues with the Development Research Center of the Chinese State Council.

DFID’s engagement with China continued to evolve on the basis of a memorandum of understanding agreed in 2015, which included a joint commitment to promoting the UN Sustainable Development Goals, and through a DFID Business Plan in 2016, which added a focus on engaging China on its non-aid investments in developing countries and on global issues such as climate change.

From 2018, the National Security Council adopted the Fusion Doctrine, which called for greater synergy between the UK’s various tools of external engagement, including aid. The role of DFID’s China office became more concretely focused on ‘development diplomacy’, which is the approach now being pursued by the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO). DFID’s aid programme expenditure was therefore reduced, although aid funds were still seen as valuable in building partnerships with Chinese government, research and other institutions and providing a platform for policy dialogue. There was a focus on knowledge generation through DFID’s support for China’s Development Research Center to launch and develop the Center for International Knowledge on Development. DFID also served as a ‘front office’ to other UK departments interested in engaging Chinese partners on development issues, helping to ensure a coordinated and coherent approach.

We learned from our interviews with Chinese stakeholders that the UK’s developing country and thematic expertise, as well as its strong capacity within China, are highly valued. The UK’s flexible and practical approach to development collaboration is also welcomed by its Chinese counterparts.

In recent years DFID, and now the FCDO, also increased their support to African and Asian countries to assist them in engaging with China. For example, the departments commissioned a series of papers by the Overseas Development Institute in 2020 and 2021 to map the impact of COVID-19 on the Chinese economy and its trade and investment flows – important information for developing country governments seeking to mitigate the impact of the pandemic on their own economies.

The shift to a development diplomacy role necessarily implies a long and uncertain results chain. While the objective is to relieve poverty in developing countries, the impact depends upon the UK successfully influencing China’s highly consequential trade and investment practices in developing countries as a means to this end. The extent of that influence is difficult to assess and we have not attempted to do so. Some influential voices have also cautioned against overestimating this influence and it is fair to view this influence as uncertain. The challenges involved in securing this influence also serve to highlight questions about whether this partnership is attempting to engage across too many policy agendas.

Infrastructure development in third countries

China is the largest financier of infrastructure in many African and Asian countries, and the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) is a vast undertaking with the potential to be an accelerator of trade and economic development. However, it also carries significant risks for countries and communities, including around social and environmental costs and debt sustainability.

UK engagement with the BRI, which includes both ODA-funded and non-ODA activity, aims to maximise the development benefits and minimise the risks of this initiative. It is also intended to secure commercial opportunities for UK companies in the design and delivery of BRI investments. In this instance, there is potentially strong alignment between the primary goal of maximising development results and secondary benefits to the UK: if BRI projects meet international environmental, social and governance (ESG) standards, they are more likely to offer opportunities for UK companies.

In recent years, UK government departments have used between £2 million and £3 million annually to engage Chinese actors on infrastructure standards. This spending has supported the Prosperity Fund in implementing a pilot project in Kenya, which is promoting the application of ESG standards to a road construction project involving Chinese and Kenyan companies, and in training Chinese infrastructure companies and researching their practices in relation to issues such as community consultation, gender and inclusion. It has also supported DFID in commissioning research on the risks and opportunities of the BRI.

The UK also engages China on infrastructure standards through policy dialogue in a range of multilateral institutions and forums, including the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB), the Multilateral Cooperation Center for Development Finance (MCDF) – both initiated by China – and the G20. The UK was a founding investor (contributing $611 million81 in paid-in capital) in the AIIB, and has engaged with China to ensure that its governance, ESG and procurement systems and procedures are in line with international best practice. The MCDF is a technical assistance facility designed to raise the quality of infrastructure investments, in accordance with international standards, the Sustainable Development Goals and the Paris Climate Agreement. The UK has supported efforts to ensure that the MCDF applies strong ESG standards through systematic engagement with the Chinese Ministry of Finance and multilateral development banks during the design phase of the initiative. Through the G20, which includes China, the UK played a leading role in the adoption of a set of quality infrastructure investment standards. While the standards are voluntary, G20 members are currently exploring how to track their implementation.

Across these interventions, the UK is pursuing a consistent set of priorities, focused on ESG standards, transparency and debt sustainability. DFID provided advice on these issues to the other UK government departments involved, helping to ensure a coherent approach.

Influencing the BRI programme in relation to ESG standards is a very ambitious undertaking, and will need to be sustained for some time if it is to secure change. In our interviews, Chinese actors stated that they value the UK’s expertise on quality infrastructure standards. However, the responsible UK departments are aware that commercial and other incentives may work against China’s adoption and implementation of international standards in BRI.

Global health

Public health is a recurring theme in the UK’s development cooperation with China. Four UK departments and funds have used aid to implement health-related activities. These include efforts to strengthen primary healthcare services and modernise the pharmaceutical market in China (Prosperity Fund), trilateral cooperation in Africa and Asia on malaria and maternal and child health (DFID), combating antimicrobial resistance (Department of Health and Social Care (DHSC)) and collaborations with academic and scientific institutions (DHSC and Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy (BEIS)).

These collaborations have a strong emphasis on sharing the UK’s own health expertise and promoting the UK’s life sciences sector. The Prosperity Fund has been using the National Health Service’s (NHS’s) expertise to support China’s primary healthcare system, as well as sharing the experiences of UK drug regulators with their Chinese counterparts. DHSC’s support for research on antimicrobial resistance and BEIS-funded research collaborations (especially through the Newton Fund) have enabled UK researchers to develop partnerships with Chinese-funded researchers.

The UK’s health collaborations in China can potentially help to both address China’s health needs and promote commercial benefits for the UK’s health sector. The Chinese government recognises that its primary health system faces weaknesses and UK expertise could help to fill these gaps. In addition, China faces a significant burden from non-communicable diseases, which research collaborations on new health treatments and technologies can help to address. So far, the projects have reported few examples of direct health impacts for the population of China, especially poor and marginalised groups, but it may be too early to observe these, especially given the time required to realise benefits from research.

We did, however, note some examples of health interventions that were specifically focused on rural and other resource-poor settings. For example, a number of Global Challenges Research Fund (GCRF) projects have focused on developing cost-effective health technologies or treatments adapted to these contexts.

Of the various aid-funded health engagements with China, the Prosperity Fund has the most explicit focus on secondary commercial benefits for UK companies, alongside primary development impact. Documents reviewed and information shared by officials in interviews indicate that the secondary benefits of Prosperity Fund ODA have included £912 million of UK exports to China. We were also informed by officials that the Prosperity Fund health programme had leveraged its existing relationships with Chinese organisations to help the NHS to secure personal protective equipment (PPE) during the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic. We have not verified these results.

The global health programming also includes policy dialogue with Chinese government institutions. For example, DFID’s Global Health Support Programme was also used to fund a series of high-level UK-China Health Dialogues, which have aimed to strengthen UK-China collaborations on a range of health issues.

The future of UK aid engagement with China

Given that China is expected to graduate from Official Development Assistance (ODA) in the next four to six years, we asked the responsible UK government departments to explain how they are planning to manage this transition and how they might engage with China on development issues beyond this date. We were informed that, so far, there has been little discussion on these questions. This seems to be largely because the planned multi-year cross-government spending round has been delayed, and partly because more pressing funding issues are demanding attention (see below). Some departments also appear to view China’s ODA graduation as a challenge to be addressed in a few years’ time.

One option raised by interviewees was that UK government staff in China whose salaries are currently ODA funded could be brought onto the non-ODA baseline budget of their parent departments, reversing a step taken by some departments following the 2015 Spending Round.84 The Foreign Secretary’s April 2021 written ministerial statement does not reference this issue and it is unclear to us whether this has been implemented.

The issue of transition has been brought into immediate focus by the cuts to FCDO ODA for programme delivery in China that have been introduced following the government’s decision to reduce the ODA spending target from 0.7% to 0.5% of Gross National Income (GNI) in 2021. It has already been announced that cuts will be made to the Newton Fund and the Global Challenges Research Fund (GCRF), which may affect their China programmes. The Integrated Review of Security Defence, Development and Foreign Policy, published on 16 March 2021, suggested that collaboration with China on global issues, including climate change, biodiversity and global health, will remain a priority, as will engagement on quality infrastructure. Considering this, it is unclear whether and how departments will collaborate on these issues following the aid cuts. The lack of preparation for a China transition will make it harder for the responsible UK departments to exit from their programmes in an orderly way, as recommended in our 2016 review of DFID’s approach to managing aid exit and transition.

Among other recommendations, ICAI’s report on the transition of aid relationships outlined the importance of implementation plans, coordination among departments and clear communication to the public when undertaking these changes. Regardless of any immediate changes to ODA spending, China’s looming graduation from ODA eligibility means that planning for the changes in the development partnership was required.

Box 2: April 2021 cuts to aid to China

On 21 April 2021 the Foreign Secretary submitted a Written Ministerial Statement to parliament which outlined the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO) departmental official development assistance (ODA) allocations for 2021/22. In this statement he stated that “In China, I have reduced FCDO’s ODA for programme delivery by 95% to £0.9 million (with additional ODA in this year only to meet the contractual exit costs of former programmes).” He also clarified that “The remaining £900,000 will fund programmes on open societies and human rights.”

The description of “FCDO’s ODA for programme delivery” is hard to reconcile with the individual categories we outline in Section 4. We identify 11 portfolios and seven of these are now overseen by the FCDO – a December 2020 statement confirmed the Prosperity Fund would be moved onto the FCDO’s baseline. The Written Ministerial Statement suggests that, once contracted exit costs are addressed, only the Prosperity Fund – which had a budget of £16.5m for 2020-21 – will cease to spend programme funds in China. We propose in Section 7 a line of enquiry on the government’s strategic approach to transition, which is relevant both to the Prosperity Fund’s transition in this fiscal year and the longer-term transition of other parts of the UK’s aid engagement with China.

The statement does not provide clarity on the future levels of ODA spending related to frontline diplomatic activity and arm’s length bodies overseen by the FCDO (such as the British Council and Great Britain China Centre) – which together constituted around a third of total official UK ODA spend engaging China in 2019 – given that these are not classified as core programme delivery by the FCDO. The statement also does not provide clarity on the future levels of ODA spending by other departments. It would be for the government to confirm exactly which of the funds will continue, and which will not. We are asking further questions of departments about these cuts and will update this note in due course.

Conclusions

In the decade since DFID announced its intention to end aid for China’s development in 2011, two UK departments and funds have built new aid partnerships and others have scaled up their aid spending in pursuit of a wide range of strategic objectives. In 2019, official UK bilateral grant aid to China reached record levels, but this has been followed by a cut announced in April 2021.

Much of the engagement relates to China’s role in developing countries and on global development, and is therefore intended to benefit other countries. Even where China is formally recorded as the recipient, most of the assistance goes to UK research and government institutions working with China and there is a strong focus on securing secondary benefits to the UK.

The current aid relationship is increasingly focused on the idea of ‘development diplomacy’ – the use of aid funds to support diplomatic engagement on public policy and global development issues. It is beyond the scope of this information note to assess how influential UK aid has been in China. While the UK departments offered examples of constructive engagement with Chinese partners and we received positive feedback from Chinese stakeholders on the value of UK aid, the challenging political context suggests a need to limit expectations about what influence UK aid can leverage. However, given the scale of economic ties between China and other developing countries, even modest influence has the potential for wide-ranging impact.

UK development cooperation with China remains controversial, and there are many voices arguing that no UK aid should go to a rising economic power whose interests and values are not well aligned to the UK’s.90 In view of this criticism, it is notable that the UK government has published only limited information on the objectives and nature of its development cooperation with China and limited information on the detail of its cut in April 2021. There are complex issues involved and a more informed public debate about how to address them would be beneficial. We outlined in our 2016 report on transition that the reasons for continuing and scaling up aid to China had not been adequately communicated; in this context, it is unfortunate that the FCDO have presented the recent announcement as a 95% cut, without an explanation of the levels of spending across government that will continue.

Despite the fact that China is expected to graduate from Official Development Assistance eligibility in the next four to six years, the UK government is yet to plan for a transition of its development relationship with China beyond ODA. As a result, the government seems ill-prepared to deal with the reality of cuts to its aid engagement with China. These same risks motivated ICAI to raise concerns in 2016 about DFID’s lack of exit and transition planning in its aid relationships with emerging economies. It therefore seems fair to ask how far government policy in this area has developed over this period.

Lines of enquiry

This account of UK development cooperation with China has raised some important issues that may benefit from further scrutiny by the government, International Development Committee, ICAI or other actors.

- Ensuring a pro-poor focus – How should the UK government ensure that poverty reduction, which is the statutory purpose of UK aid, remains the primary focus of its remaining aid engagement in China? Is there a need for more explicit rules on what elements of spending are reported as ODA in the UK’s partnerships with middle-income countries?

- Taking a strategic approach to transition – How can the transition out of aid to China be managed in a way that preserves the relationships that have been built with Chinese institutions? How will the UK resource its continuing engagement with China on shared global development challenges, such as global health threats and climate change, when aid can no longer be used?

- Improving transparency – How could the government better communicate to the public the nature and purpose of UK development cooperation with China, including changes to the UK aid relationship with China as spending reduces, to promote public understanding and informed debate?

- Development diplomacy – What has been learned about how to use aid effectively for policy influence on global development issues? Is development diplomacy possible without project funding? How can the UK departments distil learning from their development diplomacy in China for use in other contexts? How will aid-funded spending on development diplomacy by UK diplomats in China fall as FCDO aid programme delivery in China is cut back?

July 2021 update to ICAI information note on UK aid engagement with China

Introduction

The Independent Commission for Aid Impact (ICAI) published an information note on UK aid engagement with China on 28 April 2021. While the note was awaiting publication, the foreign secretary announced Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO) official development assistance (ODA) allocations for programme delivery for 2021-22. In a Written Ministerial Statement, published on 21 April 2021, he noted that “[i]n China, I have reduced FCDO’s ODA for programme delivery by 95% to £0.9 million (with additional ODA in this year only to meet the contractual exit costs of former programmes)”. He also confirmed that “[t]he remaining £900,000 will fund programmes on open societies and human rights”. As outlined in the information note (see Table 1), in 2019 FCDO expenditure accounted for just under half of the government’s total ODA spent engaging China, and FCDO’s ODA for programme delivery accounted for only part of the department’s total ODA spent engaging China.3

ICAI was not provided with advance information about these reductions and was therefore not able to report fully on these changes at the time. We were also not able to look into whether FCDO’s announcement signalled that reductions to aid engagement with China had been agreed in other departments. As a result, our published information note stated that ICAI would ask further questions of FCDO and other departments about these changes and publish an update. We asked the government to confirm:

- the budgets and, where available, expenditure across three financial years up to and including 2021- 22 for the 11 portfolios outlined in our information note

- which programmes were considered “FCDO’s ODA for programme delivery” and were affected by the foreign secretary’s announcement

- details of the contractual exit costs required for “former programmes”.

Based on the information provided, this update attempts to describe what reductions have been made by the government to UK aid engaging China. It begins with changes to FCDO’s activities and then moves on to those of other departments.

FCDO aid engagement with China

In order to fully explore the impact of the Written Ministerial Statement on FCDO’s aid spent engaging China, ICAI asked about the eight portfolios managed by FCDO outlined in our information note. These were:

- British Council

- Chevening Scholarships

- Frontline diplomatic activity

- Great Britain China Centre

- International Programme

- Prosperity Fund (which was moved on to FCDO’s baseline in 2021-22)

- Former DFID China office

- Former DFID centrally managed programmes.

In its response, FCDO confirmed that only two portfolios, the International Programme and the Prosperity Fund, are categorised by the department as “ODA for programme delivery in China” and were therefore covered by the Written Ministerial Statement. In 2020-21, the baseline year for the reductions, spending for these two portfolios totalled £17.48 million, comprising £16.7 million for the Prosperity Fund and £0.78 million for the International Programme. ICAI was told that, in 2021-22, the Prosperity Fund was to have no budget for working in China, beyond the contractual exit costs for its programmes, and the International Programme was to be provided with a budget of £0.9 million to fund programmes on open societies and human rights. This is how FCDO explains the meaning of the 95% reduction described above. FCDO did not provide us with information on the contractual exit costs for the Prosperity Fund programmes, on the grounds that these are still being negotiated.

In 2020-21, the Prosperity Fund and the International Programme accounted for 35% of FCDO’s bilateral aid engaging China, and 22% of the overall UK bilateral aid engaging China. We asked for confirmation of the 2021-22 budgets for the remaining six FCDO portfolios, to better analyse the overall reductions to ODA engaging China, but FCDO did not provide us with these figures. We were informed that in the case of frontline diplomatic activity, the methodology for calculating this element of UK ODA is being updated, and that Chevening Scholarships and British Council ODA figures are not budgeted by country. In other cases, FCDO responded that it was not willing to share this information with ICAI at this time, and that this information would be published in accordance with the “usual process”, in FCDO’s annual report, in the Statistics on International Development, and on Devtracker.

ODA spending which engages China planned by other government departments

We also requested information on planned levels of aid spending engaging China in 2021-22 from the Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy (BEIS – including the Newton Fund, the Global Challenges Research Fund (GCRF) and International Climate Finance), the Department of Health and Social Care (DHSC) and the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (Defra). As a baseline, projections for 2020-21, provided to us by the government, showed a 25% decline in Newton Fund spending in China compared to 2019-20. Spending for the GCRF, DHSC and Defra had remained broadly stable.

BEIS responded that a 2021-22 budget for the Newton Fund’s work in China had not yet been finalised, and that it was unable to provide portfolio budget information for the GCRF on the basis that its partnerships “are thematically driven and challenge led and they don’t work in such a way as to budget spend on a country basis upfront”. BEIS also did not provide information on the 2021-22 budgets of individual Newton Fund and GCRF programmes that engage China.

DHSC responded that budgets for relevant programmes for 2021-22 had not yet been finalised.

Defra confirmed that for 2021-22 it was planning to spend £148,275 on two projects through the Illegal Wildlife Trade (IWT) Challenge Fund which aim to reduce demand for IWT products among Chinese nationals visiting Laos and Thailand.

In summary, we are not able to provide a clear account of the budgets for the current financial year, and thus any changes in ODA spending engaging China by government departments other than FCDO.

Conclusion

The Written Ministerial Statement of 21 April 2021 announced a reduction of FCDO’s ODA for programme delivery in China of 95%. We have assessed the budget figures, and the reduction can be explained as referring to the closure of the Prosperity Fund programme in China. This reduction only applies to 22% of total government ODA expenditure engaging China. Of the remaining 78% of ODA spent engaging China, the government did not provide ICAI with budget figures for the 2021-22 year, and we are unable to provide a description of changes in expenditure compared to previous years. FCDO also did not provide us with details of contractual exit costs for programmes in China which are closing. Overall, it is clear that the description of a 95% reduction applies to two funding channels provided by FCDO which are considered “programme delivery… in China”, and therefore only a portion of total ODA spent by the government on engaging with China. ICAI will continue to track emerging plans for UK aid engagement in China and report on any significant new developments.

Annex 1: UK collaborations with China

Figure 4: Engagement by UK departments or funds with Chinese government counterparts facilitated by UK aid spending, by sector