The UK’s approach to democracy and human rights

Purpose, scope and rationale

Promoting and protecting democracy and human rights overseas is a long-standing UK government commitment, reiterated in the 2022 UK strategy for international development and the 2021 Integrated review of security, defence, development and foreign policy.

This objective has become both more pressing and more challenging over the last decade, according to academic research and global indices on democracy and human rights. The Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) Institute finds that the democratic gains which followed the end of the Cold War in 1989 were reversed for the average global citizen by 2021 and that the share of the world’s population living in dictatorships has increased from 49% in 2011 to 70% in 2021. The CIVICUS monitoring network identified serious civic space restrictions in 117 out of 197 countries; the most affected civil society groups are those advocating for women, environmental rights, labour rights, LGBTQI+3 and youth. Other threats to democracy and human rights include restrictions on opposition politicians and the media, concentration of power in the president or prime minister, weakening of checks and balances, uncompetitive elections, political polarisation, populism, and disinformation campaigns.

The purpose of the review is to explore how effectively the UK aid programme has responded to the emergence of these new threats to democracy and human rights on the global stage. The review will cover UK aid policy, influencing and programmes on these issues between 2015 and 2021. It will examine programmes funded through official development assistance (ODA) which contribute to democratic participation and civil society, legislatures and political parties, elections, human rights, media and free flow of information, and women’s equality organisations. The review will include both global and in-country programmes managed by the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office, the cross-government Conflict, Stability and Security Fund and other government departments. These programmes are delivered through a range of channels, including core funding to public bodies, grants to non-governmental organisations, contracts with private sector implementers and contributions to multi-donor trust funds.

The review will focus on policies and programmes aimed at promoting and protecting democracy and human rights from threats, including to civil and political rights, which are the backbone of liberal democracy. It will also explore how aid policies and programmes have taken into account the core principles of equality and non-discrimination, transparency, accountability and participation. Through country case studies, it will examine how UK aid has considered economic, social and cultural rights, and the rights of individuals belonging to ‘at-risk groups’ – that is, specific social groups which have been excluded or persecuted (such as LGBTQI+, religious or ethno-linguistic minorities).

Background

Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 16 concerns “more peaceful, just and inclusive societies which are free from fear and violence”. The UK government was active in the negotiations on SDG 16 and has continued to prioritise support for its implementation. For the first time, in 2015, democracy and human rights became globally agreed development objectives, not only through SDG 16, but also as part of commitments to gender equality, combatting inequalities and leaving no one behind. While there are explicit references to the international human rights system in the 2030 Agenda for sustainable development, commitments to democracy are implicit, through democratic principles such as participation.

In addition to the SDGs, the UK government is also the initiator and/or an active member of a range of global coalitions, from the Community of Democracies to the Open Government Partnership.

In 2015, the UK government undertook to:

- push for new global goals to eradicate extreme poverty by 2030 and promote human development, gender equality and good governance

- continue to promote the ‘golden thread’ of democracy, rule of law, property rights, a free media and open, accountable institutions

- promote democracy through specific institutions, such as the Commonwealth, and in specific countries, such as with Burma’s democratic transition

Before the creation of the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO), the Department for International Development (DFID) was responsible for the majority of democracy and human rights aid programming, and shared with the Foreign and Commonwealth Office (FCO) policy leadership on economic, social and cultural rights. As well as leading UK diplomacy on democracy and human rights, FCO was responsible for several democracy and human rights aid-funded programmes, including the Westminster Foundation for Democracy (a non-departmental public body sponsored by FCO, and later FCDO) and the Magna Carta Fund for Human Rights and Democracy. The cross-governmental CSSF also devoted new resources to this agenda, including in Eastern Europe, the Western Balkans and North Africa, with relevant programmes managed by either DFID or FCO.

In 2020, DFID and FCO merged to form FCDO. Democracy and human rights became part of a new Open Societies agenda, pursued through a combination of programmes and diplomatic engagement. The 2021 Integrated review set out a renewed commitment to “the UK as a force for good in the world, defending openness, democracy and human rights” – which it argued both represents UK values and constitutes the best protection for liberal democracies and free markets through a rules-based international order. Open Societies priorities include civic space and human rights defenders, gender equality and women’s rights organisations, freedom of religion or belief, media freedoms and countering disinformation, strong, transparent and accountable political processes and institutions, the rule of law, the prevention of arbitrary arrests and detention, torture and the death penalty, and a new autonomous sanctions regime for human rights violations and abuses.

The UK’s democracy and human rights portfolio includes both in-country and centrally managed programmes. Estimated total spend (2015-16 to 2021-22) is around £1 billion for the six thematic spending areas mentioned above, with democratic participation and civil society representing half of the portfolio. The in-country programmes (estimated at £623 million) include stand-alone democracy and human rights programmes and relevant components of other programmes from other sectors, for example, inclusion or accountability in health or education.

Review questions

The review is built around the relevance, coherence and effectiveness evaluation criteria.13 It will address the following questions and sub-questions:

| Review criteria and questions | Sub-questions |

|---|---|

| 1. Relevance: Does the UK have a credible approach to using aid to counter threats to democracy and human rights in developing countries? | • To what extent are UK aid programmes based on sound diagnostic analysis, clear theories of change and evidence of ‘what works’? • To what extent are UK aid programmes addressing the most pressing threats to democracy and human rights? • To what extent does UK aid focus on promoting and protecting the rights of the most at-risk groups in each context? |

| 2. Coherence: How coherent is the UK’s approach to countering threats to democracy and human rights? | • How coherent and coordinated are the UK government institutions involved in influencing and delivering UK aid for democracy and human rights? • To what extent is the UK’s use of aid to promote and protect democracy and human rights coherent with other policy areas and interventions? • How well does UK aid serve as a platform for partnerships and diplomatic engagement at national and international levels? |

| 3. Effectiveness: How well has the UK contributed to countering threats to democracy and human rights? | • To what extent have UK aid programmes delivered results towards democracy and human rights objectives, and increased access to democracy and human rights for target groups? • How well have UK aid programmes developed institutional capacity for protecting and promoting democracy and human rights at national and international levels? • How well have UK aid programmes partnered with and supported change agents and coalitions at national and international levels? • How well do UK democracy and human rights programmes measure results and adapt in response to changes in context and to learning? |

Methodology

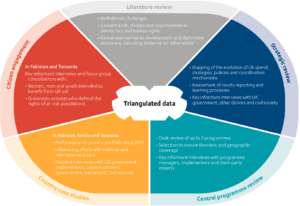

The methodology for the review will involve five components, to gather and compile evidence around the review questions and ensure sufficient triangulation of findings (see Figure 1). The components are:

- a literature review

- a strategy review of the UK’s guiding strategies, policies and management systems as well as a desk review of the UK’s overall democracy and human rights aid portfolio

- a central programme review examining the UK’s support, through funds managed from the UK, for priority democracy and human rights organisations or partners

- three country case studies of UK portfolios

- citizen engagement undertaken with people, in particular at-risk groups, affected by UK aid democracy and human rights programmes

The review will draw on evidence from UK policy, strategy, guidance and programming documents, key informant interviews with UK government departments, implementing partners, partner country democracy and human rights actors (such as human rights defenders, women’s activists, journalists and politicians), government officials and independent thematic experts, as well as multilateral organisations and other donor governments. We will engage with a selection of at-risk groups which have interacted with UK programme activities in the case study countries to collect feedback on whether UK aid programmes responded to their priorities and advanced their access to democracy and rights.

Figure 1: Methodology wheel

Component 1 – Literature review: The literature review will provide evidence for the relevance and coherence review questions. It will outline global trends, threats and opportunities in democracy and human rights, and global approaches to using development assistance to support democracy and human rights. It will summarise the main strengths, weaknesses and lessons learned from approaches used by different actors (including diplomacy, policy coherence, diplomatic tools and use of non-aid instruments) across different contexts, while outlining strengths and weaknesses in the evidence base as to ‘what works’. The literature review will be published alongside the report.

Component 2 – Strategic review: To address our review questions on relevance and effectiveness, we will trace the evolution of UK strategies, policies, commitments and programming guidance, and collect data

on the evolution of the portfolio and programming over time, particularly in terms of identified threats. To address our questions on coherence, we will examine how the Department for International Development and the Foreign and Commonwealth Office collaborated to leverage aid and diplomatic instruments, and whether a merged Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office has developed and is implementing a coherent agenda. We will also identify intra- and interdepartmental coordination mechanisms around open societies and human rights, and explore how well they have ensured policy coherence, focusing on selected issues and decisions. As well as key informants across the UK government, we will interview academics, practitioners, non-governmental organisation representatives and implementing partners, and conduct a stakeholder workshop with academics and practitioners.

Component 3 – Central programme review: Through a desk review and selected interviews with UK government officials, programme implementers and international partners, we will examine up to five centrally managed, regional or multilateral programmes, to compare approaches to responding to threats to democracy and human rights in different contexts and support for at-risk groups (relevance), assess coherence and coordination among the responsible departments (coherence), and trace the results, innovations and adaptations in response to changes in the context and learning (effectiveness). Findings

will be triangulated through field work in the three case study countries and a separate citizen engagement exercise. We will review at least one global initiative to assess the UK’s international influence and how UK aid served as a platform for partnerships and diplomatic engagement.

Component 4 – Case studies: We will conduct visits to three case study countries: Tanzania, Serbia and Pakistan. We will assess how the UK identified and responded to threats to democracy and human rights

and supported the most at-risk groups (relevance), how UK aid served as a platform for partnerships and diplomatic engagement at national levels (coherence), and the extent to which UK aid programmes and related influencing contributed to results and increased access to democracy and human rights, developed institutional capacities, built coalitions for change, and adapted in response to changes in context or learning (effectiveness). In addition to UK government officials and programme implementers, we will interview national and local organisations who took part in UK-funded activities and independent actors (for example academics, media), as well as other development and diplomatic actors, to triangulate findings.

Component 5 – Citizen engagement: ICAI is committed to incorporating the voices of citizens in countries affected by UK aid into its reviews. We will consult women and men, including youth, in Tanzania and Pakistan. The engagement will be undertaken by national research partners, supported by rigorous safeguarding and research protocols. The research will be primarily qualitative in nature: we will engage with citizens from at-risk groups who are expected to benefit from UK aid programmes. Citizen engagement will be gender-sensitive and will provide evidence about our relevance and effectiveness review questions, including whether UK aid has addressed core democracy and human rights threats as perceived by citizens, if it is reaching the right people, and the degree to which it has empowered grassroots change agents in their defence and promotion of human rights.

Sampling approach

ICAI has chosen to review three country programmes in Eastern Europe/Western Balkans, East Africa, and Asia/Pacific. Three case studies have been selected on the basis of the following criteria:

- largest aid expenditure over the period in each region, across most of the six thematic areas

- active centrally managed programmes (see below – central programme sampling)

- a range of political contexts and threats to democracy and human rights, with at least one UK human rightspriority country and one improving context

- feasibility of either a field visit or a remote visit.

Applying these criteria, from a shortlist of ten countries, we selected Tanzania, Pakistan and Serbia. Pakistan and Tanzania have some of the largest UK aid democracy and human rights portfolios, which include long- standing programmes operating over successive phases. Although it is not the largest portfolio in its region, Serbia has received UK aid for democracy and human rights through three relevant Conflict, Stability and Security Fund (CSSF) programmes: the Good Governance Fund, the Western Balkans Stability Programme, and the Counter-disinformation and Media Development Programme. In the three countries, UK aid activities cover all six thematic areas, and central programmes from our sample.

In all three countries, global democracy and human rights indices and reports identify a range of severe restrictions, in particular facing opposition politicians, journalists and civil society groups. There were few improvements during the 2015-21 period. Pakistan is a Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO) human rights priority country.14 At-risk groups across all three countries include women, girls and boys, religious and ethnic minorities, people living with disabilities, and LGBTIQ+ people.15

The central programmes were selected on the basis of the following criteria:

- largest aid expenditure over the period across different thematic areas to capture the main central thematic instruments (including cumulative funding for the same organisation or objective through different central programmes)

- active in case study countries (see above)

- one former Foreign and Commonwealth Office (FCO) fund, to learn lessons from a distinctive approach

- one international or global initiative, to review UK influence.

Applying these criteria, from a longlist of 30 programmes, we selected the following, which represent at least 40% of expenditure by central programmes on the six thematic areas:

- Magna Carta and other human rights funds: FCO financed its democracy and human rights priorities through a series of funds, which are now managed by FCDO’s Open Societies and Human Rights Department. These are mainly small projects linked to ministerial priorities, including in Pakistan, Tanzania and Serbia, our case studies.

- Westminster Foundation for Democracy (WFD): The UK’s non-departmental public body for international support for parliaments, political parties, elections and civil society, supported through UK aid core funding and grants as well as competitive contracts. In the case study countries, the UK funds WFD activities in Pakistan and Serbia (including through a CSSF Western Balkans regional democracy initiative). The review will assess the UK government’s strategic partnership with WFD, and lessons from our case study countries.

- Open Government Partnership (OGP): An international initiative sponsored by the UK government which has involved close collaboration across the government (including with the Cabinet Office) and with country offices (with complementary in-country funding and diplomatic support in some countries). The review will assess OGP’s work on enabling civil society organisations and citizens to engage better with governments, and on making governments more accountable and transparent to citizens. All three case study countries, Serbia, Tanzania and Pakistan, are or have been OGP members and have benefited from central funding, although Tanzania left OGP during the review period.

- UK Aid Connect: A central civil society fund that supports a range of themes, including inclusion and open societies. The programme review will examine four grants to consortia which focus on relevant thematic areas and at-risk groups not covered by previous ICAI reviews (inclusion of at-risk groups, freedom of expression, transparency and accountability, and freedom of religion or belief). Together they represent nearly a quarter of UK Aid Connect spend to date.

- International programme: The programme review will also include an examination of UK aid in support of the international human rights system or a global initiative. For example, the Magna Carta Fund and the CSSF provide UK funding for the UN Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights.

Limitations to the methodology

Scope of the review: Democracy and human rights encompass a wide range of themes, aid modalities and approaches, which need to be explored selectively. The review will not examine human rights issues already reviewed by ICAI (such as disability, modern slavery, civil society support, or programmes targeted at women and girls such as education or maternal health). The review will not explore the wider governance agenda.

Breadth of sampling: The three country case studies were selected because they offer a breadth of programming across the main spending areas, but do not necessarily constitute a representative sample of the portfolio. The central programme reviews will undertake field work only in the case study countries, which may not be representative of their global activities. However, lessons identified should be relevant for other Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO) programming and influencing.

Access to documentation: Based on experience in other ICAI reviews, there may be limited documentation on former Foreign and Commonwealth Office-led programmes, and there have been recent limitations on access to Department for International Development’s legacy document management system. To manage these risks, all team members will be security-cleared and the ICAI secretariat will liaise with FCDO to agree protocols on access to and use of restricted information, respecting UK government document security guidance. Key informant interviews will address documentation gaps in case study countries, the UK and with global partners, and enable triangulation. A staggered evidence-gathering schedule allows for extra time to arrange further interviews and address any documentation gaps.

Risk management

| Risk | Mitigation and management actions |

|---|---|

| Consultation with victims of human rights violations causes distress and re-traumatisation | Consultation with victims of human rights violations causes distress and re-traumatisation We will adopt strict ethical research protocols and take a trauma-informed, ‘do no harm’ approach to consultations that respects people’s rights, protects their anonymity and avoids risk of retaliation by perpetrators. We will ensure that follow-up support is signposted if needed. |

| Security risk to the team | The team will follow Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office’s travel advice and observe strict ‘duty of care’ arrangements put in place for ICAI’s service provider. The design of the methodology includes contingency planning to achieve a sufficient level of evidence even if the security conditions prevent in-person visits. Remote interviews can be conducted with a cross-section of stakeholders if required. |

| COVID-19 remains an ongoing risk | National regulations and social distancing will need to be respected during field visits, potentially affecting the quality of interviews and focus group discussions. The COVID-19 context may change rapidly, thus requiring field visits to be transformed into virtual visits. |

Quality assurance

The review will be carried out under the guidance of the ICAI chief commissioner, Dr Tamsyn Barton, with support from the ICAI secretariat. The review will be subject to quality assurance by the service provider consortium. The methodology, final report and literature review will be peer-reviewed by Jonas Wolf, a political scientist from the Peace Research Institute Frankfurt and a member of the External Democracy Promotion Network.

Timing and deliverables

The review will take place over an 11-month period, starting in January 2022.

| Phase | Timing and deliverables |

|---|---|

| Inception | Approach paper: May 2022 |

| Data collection | Country visits: March to June 2022 Evidence pack: July 2022 Emerging findings presentation: July 2022 |

| Reporting | Final report: December 2022 |