The UK’s approach to democracy and human rights

Score summary

The UK’s democracy and human rights programming since 2015 has delivered useful results in often difficult political contexts, but has been significantly affected by budget reductions and the lack of a clear policy framework since 2020.

Promoting democracy and human rights around the world is an important objective for UK aid, particularly in light of widespread democratic backsliding in recent years. We found that the UK’s £1.37 billion programming over the 2015 to 2021 period was generally relevant, as a result of good levels of staff expertise, technical guidance, access to evidence, and the ability to adjust activities in response to changes in context and lessons learned. Programmes were able to document useful results, including in difficult political contexts, especially when they operated over longer timeframes. These included making government, political, media or civil society bodies more effective, and improving rights and access to democratic institutions for at-risk groups, such as women and girls, people with disabilities, youth and, to a lesser extent, ethnic or religious minorities and LGBT+ people. Combining aid programming with diplomatic interventions often proved to be particularly effective.

However, UK aid programmes were not always able to address the key challenges identified through analysis, such as assisting journalists, human rights defenders and civil society organisations under threat from government repression. This was due to a combination of factors, such as at times low appetite for fiduciary risks or concern about doing harm to at-risk groups. The need to maintain access to partner governments led to some risk aversion, whereas some other donor countries were more willing to tolerate this risk. Sometimes it was plausible that public criticism by the UK could increase the risk to the individuals.

Repeated disruptions to UK aid since 2020 have affected the relevance and effectiveness of the portfolio, and undermined the promise of greater coherence across development and diplomatic interventions, despite the creation of a merged Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office. The UK lacks a strategy to operationalise the 2021 Integrated review’s democracy and human rights commitments, which makes it more difficult to achieve coherence. In addition, its high policy ambition is not matched by sufficient or predictable budgets as democracy and human rights expenditure was reduced by 33% in 2020. Internationally, the UK government has been influential in donor coordination, through its combination of aid budgets, technical expertise and diplomatic influence. However, a considerable amount of expertise has been lost since the merger, and the UK government’s reputation as a thought leader and reliable global actor on democracy and human rights has declined. While we award a green-amber score for the 2015-21 review period, we are concerned that the conditions may no longer be in place to reproduce these results.

| Individual question scores | |

|---|---|

| Relevance: Does the UK have a credible approach to using aid to counter threats to democracy and human rights in developing countries? |  |

| Coherence: How coherent is the UK’s approach to countering threats to democracy and human rights? |  |

| Effectiveness: How well has the UK contributed to countering threats to democracy and human rights? |  |

Executive summary

The promotion of democracy and human rights is a long-standing objective of the UK aid programme. Democracy and human rights are seen as both valuable in their own right, and a means of promoting other UK development objectives, such as poverty reduction, prosperity and peace.

Globally, democracy and human rights are under increasing pressure. The past 16 years have seen democracy backslide, with more countries becoming authoritarian than democratising. 70% of the world’s population now live in countries where governments can be considered authoritarian. There are growing restrictions on civic space – that is, the ability of citizens, civil society organisations (CSOs) and the media to organise, express their views and defend human rights.

The purpose of this review is to assess how effectively UK aid has responded to the emergence of new threats to democracy and human rights on the global stage. It assesses UK aid for democracy and human rights between 2015 and 2021, together with related diplomatic engagement. The programming was delivered by the former Department for International Development (DFID) and the former Foreign and Commonwealth Office (FCO), including through the Conflict, Stability and Security Fund (CSSF), and since 2020 by the merged Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO). FCDO made democracy and human rights part of its first priority in its 2021-22 Outcome delivery plan, highlighting how this required the combination of aid and diplomacy.

Between 2015 and 2021, the UK spent £1.37 billion in aid on support to democratic participation, elections, legislatures and political parties, media, human rights, and women’s rights organisations, ranking it among the top ten donors in these areas.

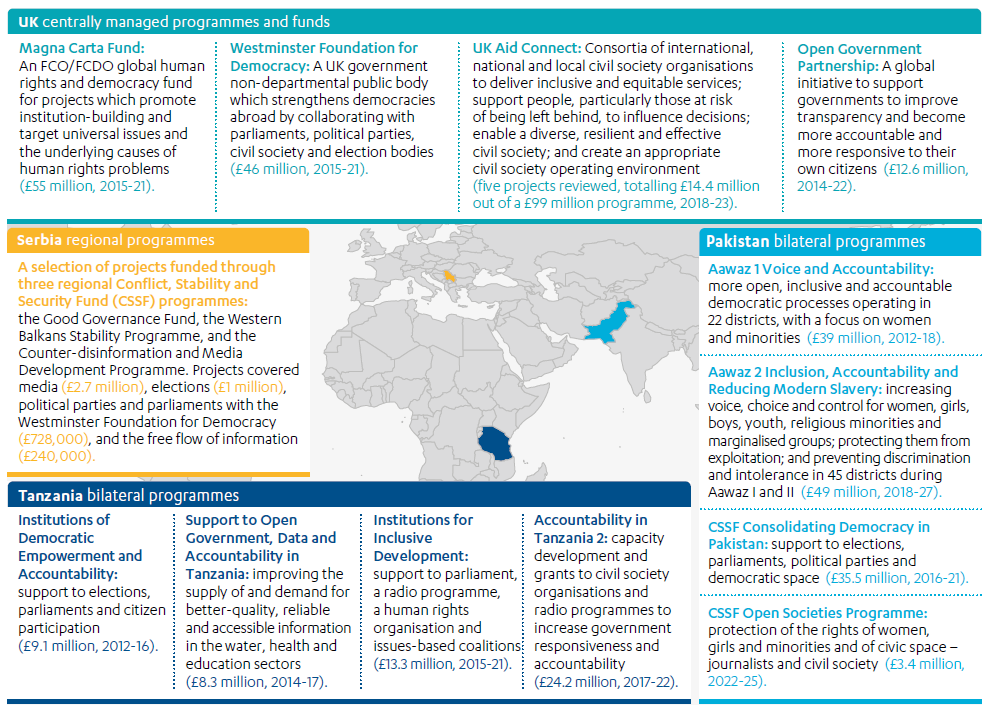

We examine whether the UK has a credible approach to countering threats to democracy and human rights, how coherent its efforts have been – especially between its aid programming and diplomatic engagement – and the effectiveness of its programming. Our methodology included country case studies of the UK efforts in Pakistan, Serbia and Tanzania, and four central programmes: the Magna Carta Fund, the Westminster Foundation for Democracy, Aid Connect and the Open Government Partnership.

Relevance: Does the UK have a credible approach to using aid to counter threats to democracy and human rights in developing countries?

We find that the UK government has correctly identified the most pressing global threats to democracy and human rights. Before 2020, DFID and FCO took different but generally complementary approaches to addressing these threats. DFID had a long-standing commitment to inclusion, supported the poorest, and focused mainly on social and economic rights, rather than civil and political rights. It did not publish democracy or human rights policies, and was usually less explicit in its approach, although it funded relevant central and country programmes which we examine in this review. FCO’s objectives around democracy and human rights were more explicit, as part of its commitment to a rules-based international order and the international human rights system. FCO delivered its objectives mainly through time-bound ‘campaigns’ on priority themes, such as media freedom, and dedicated instruments, such as the £55 million Magna Carta Fund.

However, DFID, FCO and FCDO have seen a rapid turnover of ministers since 2015, with frequent changes in the focus of aid programming and diplomatic engagement. These changes reflect the preferences of different ministers, with some strategic drift after 2019 in particular.

The UK approach is supported by high-quality technical expertise and analysis. DFID governance and social development advisers, in particular, used their in-country networks and diagnostic tools, such as political economy analysis, to understand the threats to democracy and human rights and identify politically feasible solutions. They could also rely on a range of guidance documents, and a limited but growing evidence base funded by central policy and research teams. For its part, FCO offered strong expertise on the international human rights system, and its diplomatic network, in-house researchers and legal advisers.

At the country level, UK aid programmes addressed threats to democracy and human rights by balancing changing ministerial priorities and country analysis. We find that country teams were able to ‘localise’ their response – that is, translate UK priorities into locally appropriate themes and identify suitable partner organisations. Nonetheless, UK aid programmes were not always able to respond to the most pressing threats that they identified. In particular, the need to maintain access to partner governments led to some risk aversion.

UK democracy and human rights programmes promoted and protected the rights of people belonging to the most at-risk social groups, in particular women and girls, people with disabilities, and youth. The rights of people belonging to ethnic and religious minorities were prioritised in some countries, but we found few interventions for LGBT+ people – often a politically sensitive issue in partner countries. The £88 million (2012-27) Aawaz programme in Pakistan is a positive exception that promoted the inclusion of transgender people alongside other discriminated groups.

Before 2020, UK aid programmes remained relevant in often dynamic local contexts by adapting well in response to changes and lessons learned. However, since 2020, the portfolio has been less responsive to emerging democracy and human rights challenges, due to budget reductions and loss of technical expertise within FCDO.

Given the strengths of the portfolio for most of the review period, we award a green-amber score for relevance, while noting that, since 2020, the portfolio no longer retains its agility to respond to new challenges and deliver on the UK government’s high policy ambitions.

Coherence: How coherent is the UK’s approach to countering threats to democracy and human rights?

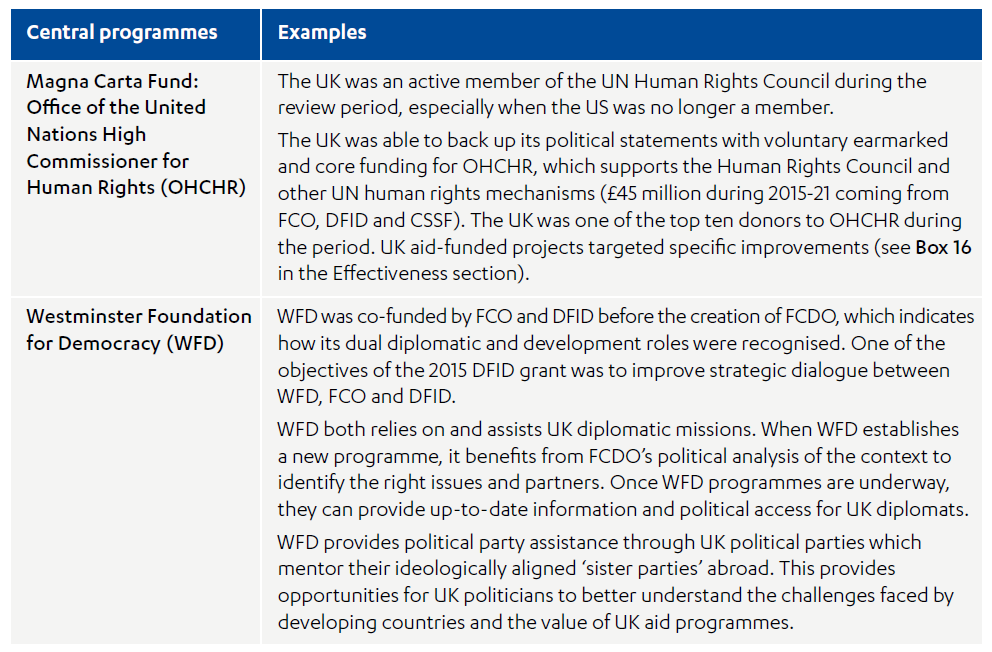

UK support to democracy and human rights has benefited from complementary development and diplomatic interventions. We found several good examples, such as the UK’s active membership of the United Nations Human Rights Council, which was complemented by £45 million in support for the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights between 2015 and 2021.

Before the merger, there were adequate coordination processes in place between DFID and FCO, and their distinct approaches were generally complementary. In principle, the merged department should now be better placed to deploy its development and diplomatic tools in tandem, to promote human rights and democracy. In practice, however, this potential is yet to be fully realised. The department has not yet fully reconciled the main differences between the development and diplomatic approaches. Development assistance typically focuses on poverty reduction, has longer timeframes for social and institutional change, and works primarily on locally defined priorities. In contrast, diplomacy tends to operate with shorter timeframes and with a focus on delivering the UK’s wider policy objectives.

The lack of an overarching UK policy framework on human rights and democracy makes it more difficult to achieve coherence. In 2021, FCDO started working on an ‘open societies’ strategy, to operationalise the UK government’s Integrated review of security, defence, development and foreign policy. This was to have been launched in mid-2022 but has not been completed, while a December 2021 speech by the then foreign secretary, Liz Truss, offered a competing geopolitical narrative, based on the idea of a ‘network of liberty’. The May 2022 International development strategy does not prioritise the theme of ‘open societies’ but refers to some of its elements such as freedom, democracy and women’s rights. None of these three documents offer clear strategic direction on democracy and human rights to FCDO staff, implementing partners and other donors seeking to collaborate with the UK. With the change of foreign secretary in September 2022, discussion of a revision of the Integrated review, and further aid budget reductions, there is more uncertainty. In December 2022 the foreign secretary, James Cleverly, did not explicitly mention democracy, human rights, ‘open societies’ or ‘network of liberty’ objectives in his speech on a ‘network of partnerships’, though he reiterated his commitment to democracy and human rights in a video statement on the same day.

The UK reiterated its global commitments to democracy and human rights, such as statements at the G7 in 2021 and the Summit for Democracy in 2022. However, we find that the UK does not have the same level of cross-government implementation as some other donors, such as Sweden and the UN. For example, we did not identify evidence of significant progress through the cross-government open societies strategy board, or otherwise improved coherence of the UK’s response to democratic backsliding and the closing of civic space since 2020.

UK aid and diplomatic democracy and human rights interventions were often coordinated with other governments, which enhanced their impact. The UK was a co-founder of both the Open Government Partnership and the Media Freedom Coalition, which helped create or sustained global standards. The UK government has also been influential in donor coordination at country level, through its combination of aid budgets, technical expertise and diplomatic influence.

However, the UK government’s reputation as a thought leader and reliable global actor on democracy and human rights has declined in recent years. Over the review period, the UK was a recognised leader on issues such as disability inclusion, the Sustainable Development Goals’ promise of ‘leaving no one behind’, politically informed approaches to development, and evidence on the promotion of some democracy and human rights issues. Since 2020, following aid budget reductions, the lack of a clear strategic framework and the disruption caused by the DFID/FCO merger, the UK is no longer considered a reliable partner or thought leader. In addition, perceptions of declining commitment to democratic and human rights norms within the UK affect the credibility of UK aid and diplomacy abroad. For example, the UK is at risk of being declared an ‘inactive’ member by the Open Government Partnership, a coalition of 77 countries which assists governments in becoming more transparent, accountable and responsive, and which has received £12.6 million in funding from the UK.

We therefore award an amber-red score for coherence, reflecting the unrealised promise of the merger and FCDO’s declining international reputation in this field.

Effectiveness: How well has the UK contributed to countering threats to democracy and human rights?

Democracy and human rights results are both challenging to achieve in repressive political contexts and hard to measure. We found that UK aid programmes improved their approach to measuring results during the period.

A focus on inclusion is a strength of the UK’s approach. UK aid helped a range of at-risk groups, in particular women and girls, people with disabilities, and youth, and to a lesser extent minorities and LGBT+ people, to advocate for their rights, combat discrimination, participate in politics and access services.

UK aid also improved the effectiveness and inclusiveness of elections, political parties and parliaments in several countries, with a shift in most programmes away from an institutional capacity development approach and towards a greater focus on nurturing coalitions for change around locally salient democracy and human rights challenges. Over the period, the Westminster Foundation for Democracy noticeably improved its performance, including in the areas of monitoring results and generating evidence.

UK transparency projects opened governments to scrutiny by promoting the publication of information about their activities. However, transparency alone is not enough to secure positive changes in government performance, and UK aid programmes could more consistently support citizens’ use of government information to promote accountability.

UK aid helped strengthen human rights organisations at global, regional and country levels. It achieved some encouraging results on media, such as improving the representation of excluded groups or testing sustainable funding models. Programmes would benefit from a more systematic approach combining the protection of media freedoms in the short term with helping the media sector develop over the longer term.

In the countries we examined, the UK government found it challenging to assist journalists, human rights defenders and CSOs under threat from government repression – in part because of fear of damaging its relationships with partner country governments. We note that some other donor countries were more willing to tolerate this risk. Support for civic space has also been affected by the UK’s insistence on funding specific activities, rather than offering core funding, which is more useful in helping CSOs withstand pressure from their governments.

Across the portfolio, we found that UK aid programmes achieved good results when they worked with both governments and citizens, focused on locally salient issues, facilitated coalitions and had longer timeframes.

Since 2020, some UK aid programmes delivered less than their potential due to budget reductions during their implementation. UK expenditure for democracy and human rights was reduced by 33% in 2020 and stayed at a similar level in 2021. In our sample, reprioritisation particularly affected central programmes and the Tanzania portfolio, although the unpredictability of funding has had an impact across UK aid’s global portfolio.

Other project management challenges which reduced effectiveness include the short funding cycles and poorer results measurement of the Magna Carta Fund and the CSSF, and long delays in moving from design to implementation for large DFID programmes. The UK government could also improve the links between its central programmes and its country programmes, a weakness which undermined some centrally funded Westminster Foundation for Democracy interventions.

We therefore award a green-amber score for effectiveness, in recognition of some strong results over the review period in difficult political contexts, while noting with concern a trend towards programmes becoming less effective since 2020.

Recommendations

Recommendation 1

FCDO should set out publicly its approach to democracy and human rights.

Recommendation 2

FCDO should ensure it retains sufficient expertise, in particular in governance, to design and monitor its democracy and human rights interventions.

Recommendation 3

FCDO should introduce a leaner process to design and approve smaller programmes, while ensuring that due diligence is sufficient to allow approval for longer than one year.

Recommendation 4

FCDO should consider whether it can learn from other countries, and take more risks to support individuals and organisations facing the most serious threats from repression.

Recommendation 5

FCDO should ensure all its central democracy and human rights programmes work closely with its overseas network where democracy and human rights have been prioritised, in particular with better coordination with the Westminster Foundation for Democracy.

Introduction

1.1 Democracy and human rights are under pressure globally. A rise in authoritarianism since 2006 has entirely reversed the wave of democratisation that followed the end of the Cold War. Today, 70% of the world’s population live in authoritarian regimes, according to the Varieties of Democracy Institute. Most countries have placed new restrictions on ‘civic space’ – the ability of citizens, civil society organisations (CSOs) and the media to organise, express their views and defend human rights.

1.2 Promoting and protecting democracy and human rights overseas is a long-standing objective of UK aid, reiterated in the 2015 UK aid strategy, the 2021 Integrated review of security, defence, development and foreign policy and the 2022 International development strategy. The UK government supports liberal democracy, a political system where governments are elected through regular and credible elections, civil and political rights are respected, and parliaments, the media and civil society can hold officials to account. The UK also promotes democratic and human rights principles, which include participation, accountability, transparency, equality and non-discrimination. Democracy and human rights are considered both goals in their own right and a means of promoting other UK aid objectives, such as poverty reduction, prosperity and peace. Box 1 summarises how they are included in the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

1.3 The purpose of this review is to assess how effectively UK aid has responded to the emergence of new threats to democracy and human rights on the global stage. It covers UK aid programming between 2015 and 2021 in the following thematic areas: democratic participation and civil society, legislatures and political parties, elections, human rights, media and free flow of information, and women’s rights organisations. It examines how well UK aid policies and programmes reflect human rights and democracy principles, and how they help to protect individuals who belong to social groups at risk of persecution or exclusion, such as LGBT+ people and members of religious and ethnic minorities (hereafter, ‘at-risk’ social groups).

1.4 The UK’s efforts to promote democracy and human rights include both aid programming and related diplomatic engagement. The review therefore examines the effects of merging the Department for International Development (DFID) and the Foreign and Commonwealth Office (FCO) in 2020 to form the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO). It covers UK aid policies and programmes delivered by DFID, FCO and FCDO, including those funded through the Conflict, Stability and Security Fund.

1.5 The review is built around the evaluation criteria of relevance, coherence and effectiveness. It addresses the questions and sub-questions set out in Table 1.

Box 1: How this report relates to the Sustainable Development Goals

The SDGs, otherwise known as the Global Goals, are a universal call to action to end poverty, protect the planet and ensure that all people enjoy peace and prosperity.

Democracy and human rights are most directly addressed through Goal 16 on peaceful and inclusive societies for sustainable development, access to justice, and effective, accountable institutions. Its targets include “Ensure responsive, inclusive, participatory and representative decision-making at all levels”.

The goals relating to gender equality (SDG 5) and combatting inequalities (SDG 10) are directly linked to human rights. The 2030 agenda for sustainable development also calls for ‘leaving no one behind’, makes explicit references to the international human rights system and mentions democracy.

Table 1: Our review questions

| Review criteria and questions | Sub-questions |

| 1. Relevance: Does the UK have a credible approach to using aid to counter threats to democracy and human rights in developing countries? | • To what extent are UK aid programmes based on sound diagnostic analysis, clear theories of change and evidence of ‘what works’? • To what extent are UK aid programmes addressing the most pressing threats to democracy and human rights? • To what extent does UK aid focus on promoting and protecting the rights of the most at-risk groups in each context? |

| 2. Coherence: How coherent is the UK’s approach to countering threats to democracy and human rights? | • How coherent and coordinated are the UK government institutions involved in influencing and delivering UK aid for democracy and human rights? • To what extent is the UK’s use of aid to promote and protect democracy and human rights coherent with other policy areas and interventions? • How well does UK aid serve as a platform for partnerships and diplomatic engagement at national and international levels? |

| 3. Effectiveness: How well has the UK contributed to countering threats to democracy and human rights? | • To what extent have UK aid programmes delivered results towards democracy and human rights objectives, and increased access to democracy and human rights for target groups? • How well have UK aid programmes developed institutional capacity for protecting and promoting democracy and human rights at national and international levels? • How well have UK aid programmes partnered with and supported change agents and coalitions at national and international levels? • How well do UK democracy and human rights programmes measure results and adapt in response to changes in context and to learning? |

Methodology

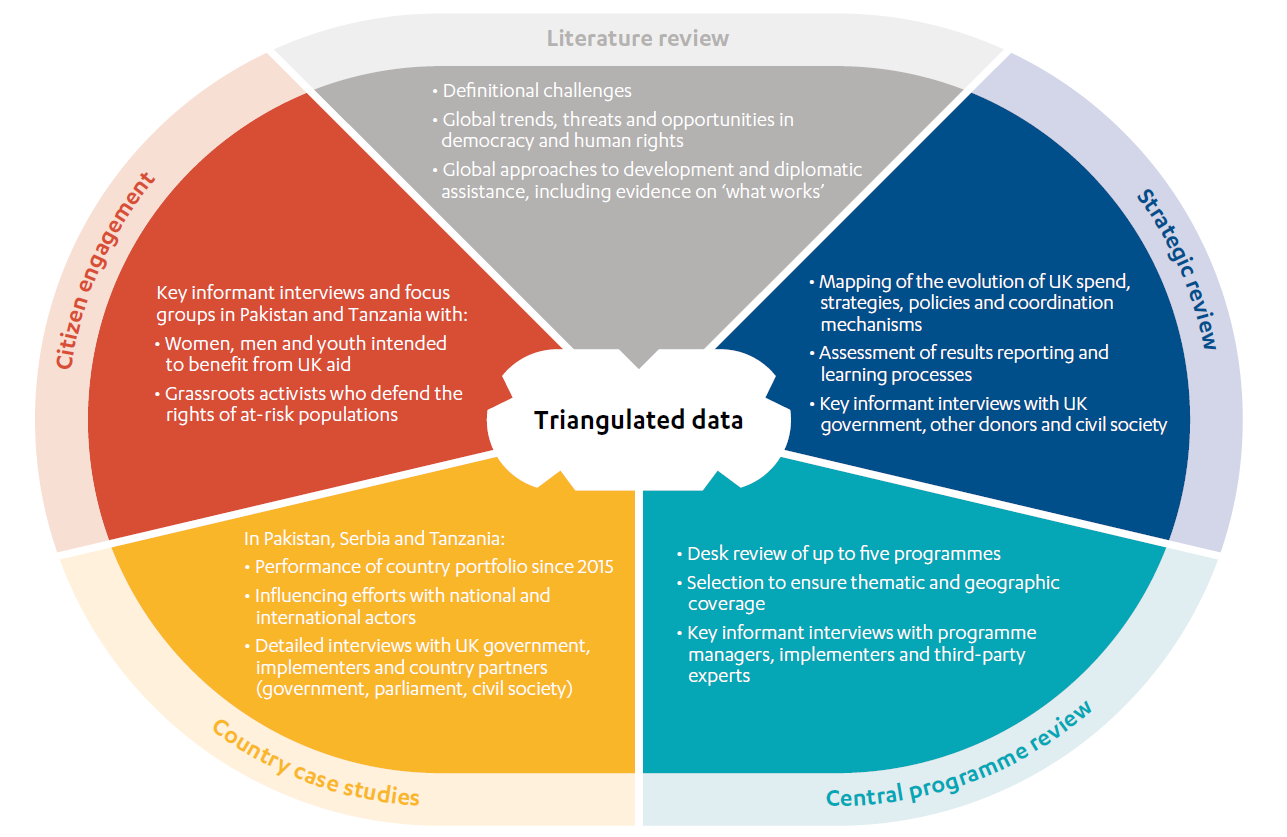

2.1 The methodology for the review involved five components, to compile evidence around the review questions and ensure sufficient triangulation of findings (see Figure 1). The components are explained below.

- Literature review: We examined 261 sources – both peer-reviewed and grey literature. The literature review examines definitions and measurement issues; global trends, threats and opportunities; and global approaches to using development assistance and diplomacy to support democracy and human rights. It summarises the main strengths, weaknesses and lessons learned from approaches used by different actors across different contexts, while outlining strengths and weaknesses in the evidence base as to ‘what works’.

- Strategy review: We reviewed the UK’s strategies, policies, guidance notes and management systems in relation to the six thematic areas through interviews with UK government officials and a document review. We prepared a financial analysis of the UK’s overall democracy and human rights aid portfolio. We examined how the former Department for International Development (DFID) and Foreign and Commonwealth Office (FCO) collaborated to leverage aid and diplomatic instruments, and whether a merged Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO) has developed and is implementing a coherent agenda. We interviewed other donors and experts to compare the UK’s approach to other organisations and to assess the UK’s current global reputation.

- Country case studies: We examined three UK aid country portfolios through document reviews and field visits to Pakistan, Serbia and Tanzania. We interviewed UK officials, implementing partners, partner country democracy and human rights actors (such as human rights defenders, women’s activists, journalists and politicians), government officials and independent thematic experts, as well as multilateral organisations and other donor governments. We assessed country strategies, and the relevance and effectiveness of 23 programmes or projects across the six thematic areas in these three countries.

- Central programme review: We examined four priority democracy and human rights organisations or schemes funded from the UK through 19 programmes or projects: the Westminster Foundation for Democracy, the Open Government Partnership, UK Aid Connect, and the Magna Carta Fund for Human Rights and Democracy. We undertook document reviews and remote interviews with UK officials and implementing partners. We also gathered first-hand evidence from local partners in the three case study countries.

- Citizen engagement: In Pakistan and Tanzania, national partners undertook focus group discussions with a selection of members of at-risk groups who were supported by UK programmes. We collected feedback on whether UK aid programmes responded to their priorities and advanced their access to democracy and rights.

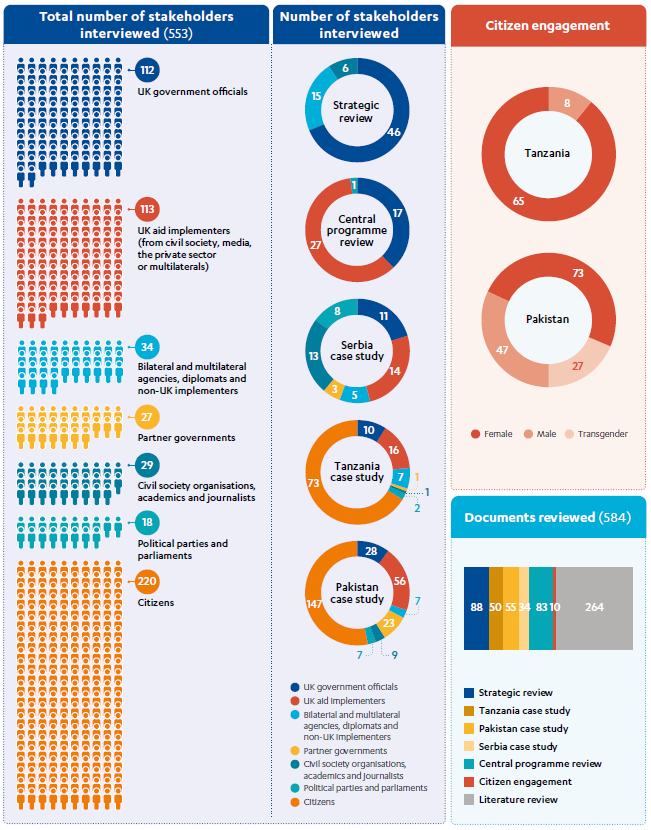

2.2 We reviewed 584 documents and interviewed 553 people (see Figure 2). A summary of all the programmes and projects we reviewed can be found in Annex 1. The limitations to our methodology are summarised in Box 2.

Box 2: Limitations to our methodology

Scope: Democracy and human rights cover many themes and delivery mechanisms. We excluded rule of law and anti-corruption, which are closely related topics, because ICAI had previously reviewed them. We did not systematically review all economic, social and cultural rights, as some of them are considered in other ICAI reviews, for example on education and modern slavery. We did not consider how UK aid prioritised the poorest groups. We also excluded funding for the BBC World Service, although we did include the BBC’s charity, BBC Media Action.

Sample representativeness: Our analysis is based on three country case studies, selected for regional diversity and to cover all six thematic areas of interest, as well as a sample of global initiatives and centrally managed programmes. The sample may not be fully representative of the diverse approaches and contexts in which the UK provides aid for democracy and human rights.

Data availability: FCDO was not able to share the same degree of information for Magna Carta Fund and Conflict, Stability and Security Fund projects (which were mostly managed by the former FCO), compared to former DFID programmes. As the review period covered seven years, key informant interviews for the early part of the period were more difficult to arrange or generated less reliable data.

Figure 1: Our methodology

Figure 2: Number of stakeholders interviewed and documents reviewed

Background

Threats to democracy and human rights

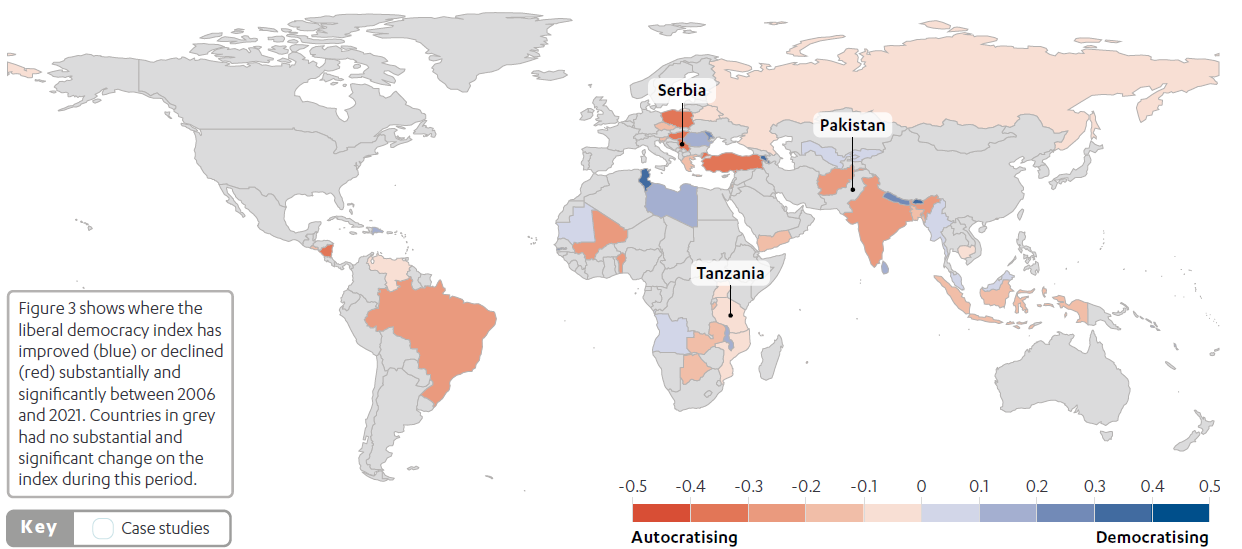

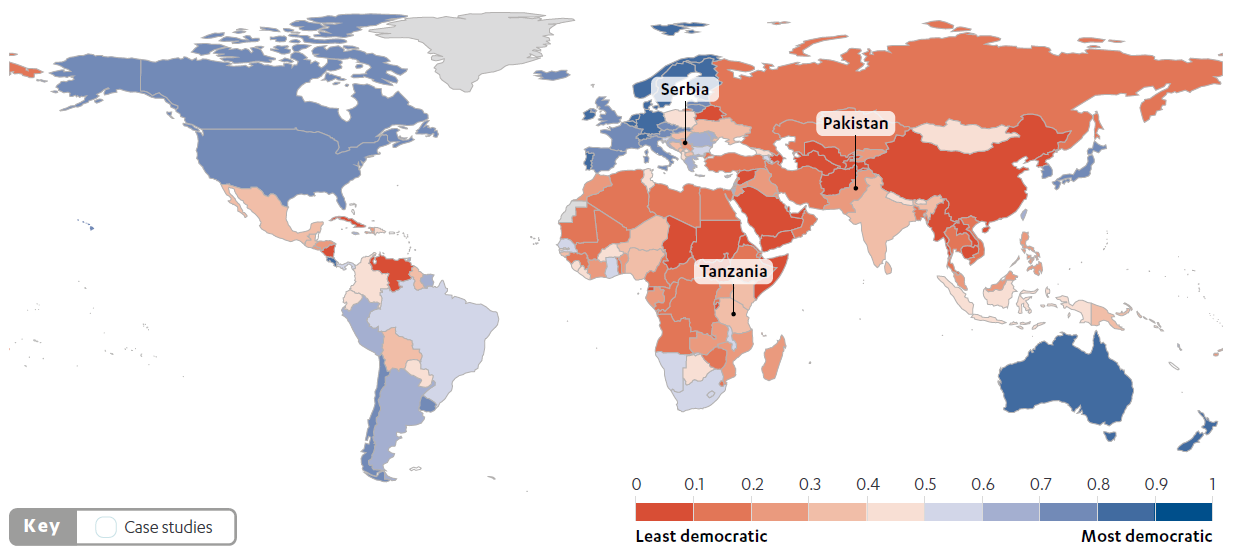

3.1 There is a broad consensus that democracy and human rights have faced increased pressure globally over the last 16 years, a trend referred to as ‘democratic backsliding’. The number of liberal democracies in the world peaked at 42 in 2012 and has now fallen to 34, representing 13% of the world’s population. The share of the global population living in countries that are becoming less democratic has increased from 5% in 2011 to 36% in 2021. Using Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) Institute data, Figure 3 shows that more countries became authoritarian than democratic between 2006 and 2021, including Serbia and Tanzania, while Figure 4 gives a snapshot of current levels of democracy, with Pakistan, Serbia and Tanzania all assessed as ‘electoral autocracies’.

Figure 3: Autocratisation trends (2006-21)

Source: V-Dem country-year dataset v12, Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) Institute 2022.

Figure 4: Liberal democracy index (2021)

Source: Democracy report 2022, Autrocratisation changing nature?, Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) Institute, 2022, p12.

3.2 Globally, there have been growing restrictions on civic space through laws that control the funding and activities of non-governmental organisations (NGOs), as well as censorship and intimidation of journalists and media houses. In 2021, the CIVICUS monitoring network assessed that 117 out of 197 countries had serious civic space restrictions. Compared with 2020, civic space ratings had deteriorated in 13 countries and only improved in one. The most affected civil society groups are those advocating for women environmental rights, labour rights, LGBT+ people and youth.

3.3 Our literature review identified other threats to democracy and human rights. In countries that are becoming less democratic, power is increasingly concentrated in the president or prime minister. There are uncompetitive or fraudulent elections, restrictions on opposition politicians, a weakening of checks and balances (for example, through political control of the judiciary) and, in some countries, the forcible removal of civilian leaders from power by the military. The COVID-19 pandemic was another source of restrictions on civil liberties (such as curfews or social distancing).

3.4 There has also been a rise in the number of populist leaders who see themselves as directly accountable to the people, disregard institutions such as parliaments or courts, and exacerbate social tensions. This can be accompanied by growing political polarisation, fed by disinformation campaigns, leading to a decline in tolerance for opposing political views. In some countries, political disengagement and complacency about the benefits of democracy have contributed to autocratisation. Emboldened autocrats resist foreign criticisms, in particular from Western governments, and learn from one another, such as by copying restrictive media and civil society laws, in order to reduce public accountability and silence critics.

3.5 Economic factors have also undermined democracy and human rights, including the capture of the state by economic elites to promote their interests; pronounced inequalities, which prevent poorer citizens from participating fully in politics; and disruptions, such as those caused by global financial crises.

3.6 This review does not cover economic or private sector development programmes that address these economic and financial threats to democracy and human rights.

‘What works’ in the promotion of democracy and human rights

3.7 Support for democracy and human rights is a sensitive area for international development partners, as these issues are at the heart of national sovereignty. External support is justified on the grounds that international human rights agreements represent a global consensus. Legally binding global or regional treaties

constitute the international human rights system. However, this system is under increasing pressure from governments that reject foreign interference in domestic affairs. There are also long-standing concerns that democracy and human rights represent ‘Western values’, despite near-universal membership of the treaties.

3.8 There are many ways in which development organisations can support democracy and human rights, including through: policy dialogue with governments; technical assistance for the preparation and implementation of policies, laws or regulations; funding and monitoring of elections; organisational development and training of parliaments, political parties, electoral commissions, human rights commissions, media and civil society organisations (CSOs), including women’s rights organisations; and programmes designed to influence social norms and values, and change behaviours, such as in relation to the rights of women or minorities.

3.9 The evidence on ‘what works’ to support democracy and human rights is limited. Our literature review summarises some of the main insights. It finds that democracy assistance can increase the prospect of democratic outcomes, but that the political context in partner countries determines the extent to which aid will be effective. It is therefore particularly important to design flexible programmes that analyse and respond to country dynamics, understand who has the power to support or block change, and avoid imposing foreign blueprints. This approach is known as ‘thinking and working politically’). In closed political contexts, it can be challenging for donors and diplomats to collaborate with state authorities, and foreign funding for non-state organisations is restricted. Innovative approaches tailored to the context are therefore needed.

3.10 Some development partners use implicit or indirect approaches, such as efforts to promote participation, transparency and accountability, without mentioning human rights or political reforms. This is the approach preferred by the World Bank and some other multilateral development banks, which have apolitical mandates. By contrast, human rights-based approaches, as promoted by the UN, the EU and some donor countries, such as Sweden or Denmark, are more explicit. They see human rights as constitutive of development and seek to mainstream human rights considerations across all aspects of development and foreign policy, as well as through dedicated programmes. The literature review finds growing evidence that mainstreaming human rights is an effective approach, which can also boost poverty reduction and improve links between states and their citizens.

3.11 Diplomatic action can complement development assistance through positive measures, such as giving public platforms to human rights defenders or rewarding governments that demonstrate a sustained commitment to democracy and rights. Negative measures include international prosecutions and sanctions for those who commit gross human rights violations, or aid conditionality (the threat of reducing foreign aid or trade benefits in response to electoral fraud or systematic human rights violations). For diplomatic action to be successful, messages must be adjusted to the country context, represent a unified international position, and be consistent with respect for democracy and human rights in the diplomats’ home countries.

The UK government’s approach to democracy and human rights

3.12 The UK government regularly makes high-level commitments on democracy and human rights (see Box 3). They are seen as UK values to be promoted, both to defend the UK’s national interest and as underpinning development in partner countries.

3.13 The UK government uses the concept of ‘open societies’ as an umbrella term covering both democracy and human rights, along with the rule of law, free trade and property rights. This framing is not used by other development organisations.

Box 3: UK government high-level policy commitments 2015-22

In the 2015 Aid strategy the UK government undertook to continue to promote the ‘golden thread’ of democracy, rule of law, property rights, a free media and open, accountable institutions. This included promoting democracy through specific institutions, such as the Commonwealth, and in specific countries, such as Myanmar’s democratic transition.

In its 2019 Governance position paper, DFID stated that: “Open, inclusive, accountable governance is fundamental to delivering sustainable development and tackling global challenges. And it supports our national interest by contributing to international prosperity, security, and the rules-based international system.” One of its shifts was: “Being confident in our values – focusing on the beneficiaries of our work and ensuring that respect for dignity, human rights, democracy and equality are reflected in the choices we make.”

The 2021 Integrated review set out how the UK would be a “force for good” in the world by supporting open societies and defending human rights, reversing the decline in global freedoms by strengthening UK domestic governance and working with allies, like-minded partners and civil society to protect democratic values, “tailoring our approach to meet local needs and combining our diplomacy, development, trade, security and other tools accordingly”. Priorities included: universal human rights, including a new global human rights sanctions regime; gender equality; effective and transparent governance, robust democratic institutions and the rule of law; freedom of religion or belief; press and media freedom; and ending the practice of arbitrary arrests and detention or sentencing of foreign nationals.

The 2021-22 FCDO Outcome delivery plan includes “promoting human rights and democracy” as part of its first objective, which is to “shape the international order and ensure the UK is a force for good in the world”.

The December 2021 foreign secretary’s ‘network of liberty’ speech no longer prioritised ‘open societies’. Instead, it set out freedom and democracy as a geopolitical vision of like-minded liberal democracies collaborating on security and trade: “When we put freedom first, we all benefit. The more freedom-loving countries trade with each other, build security links, invest in our partners and pull more countries into the orbit of freedom, the safer and freer we all are.”

The 2022 International development strategy made a commitment to furthering “UK ideals, standing up for freedom around the world and supporting countries to plan for their own sustained, long-term progress and resilience”. This included support for “effective institutions” which underpin development: “from functioning markets to a free press and from a credible central bank to fair courts. Open and accountable institutions ensure systems work for everyone.” Beyond the prioritisation of women and girls, the strategy did not make democracy and human rights an explicit priority to the same extent as the Integrated review or the Outcome delivery plan.

The UK government used multilateral events, such as the G7 in 2021 and the Summit for Democracy in 2022, to reiterate its commitments to democracy and human rights.

On 12 December 2022, the foreign secretary made two speeches. In a video statement, he reaffirmed his commitments to human rights and democracy. By contrast, there were no references to democracy, human rights, ‘open societies’ or ‘network of liberty’ objectives in the main speech setting out his aim “to revive old friendships and build new ones, reaching far beyond our long-established alliances” by “developing clear, compelling and consistent UK offers, tailored to their needs and our strengths, spanning trade, development, defence, cyber security, technology, climate change and environmental protection.”

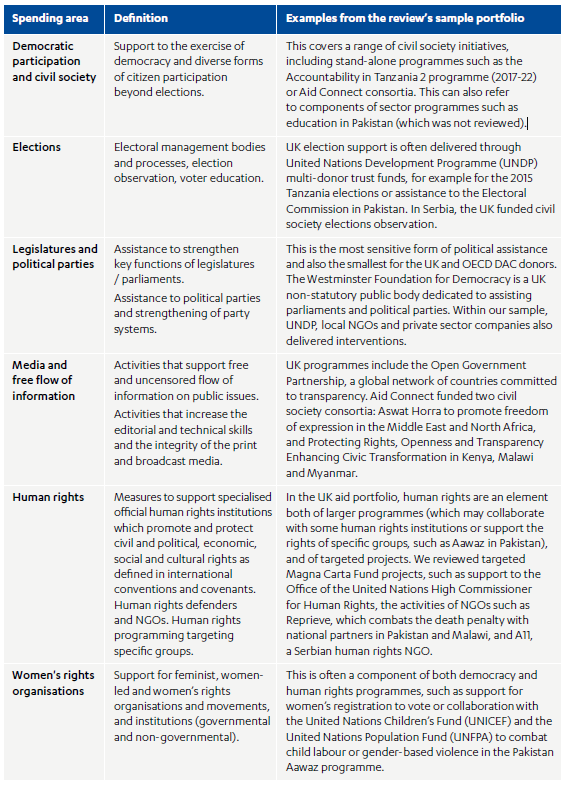

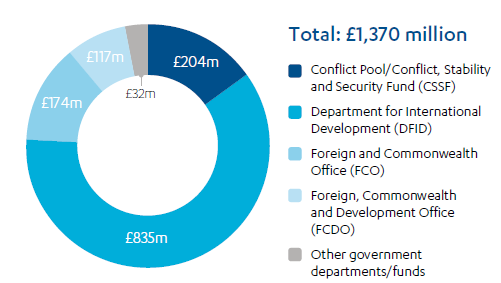

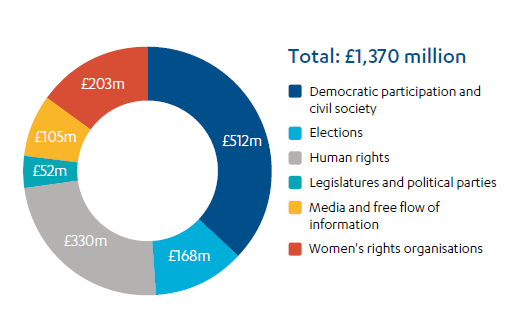

The UK aid democracy and human rights portfolio

3.14 We reviewed the UK aid democracy and human rights portfolio across six thematic spending areas (see Table 2 for the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development’s Development Assistance Committee (OECD DAC) definitions). Between 2015 and 2021 (the last calendar year for which official data is available), total UK aid expenditure was £1.37 billion.

3.15 Between 2015 and 2021, the Department for International Development (DFID) was responsible for 61% of the expenditure, and the Foreign and Commonwealth Office (FCO) for 14%. The Conflict, Stability and Security Fund funded 15% of programmes (mostly implemented by FCO), and other departments or funds only accounted for 3%. The first year of the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO) in 2021 represents 8% of spend over the period (see Figure 5).

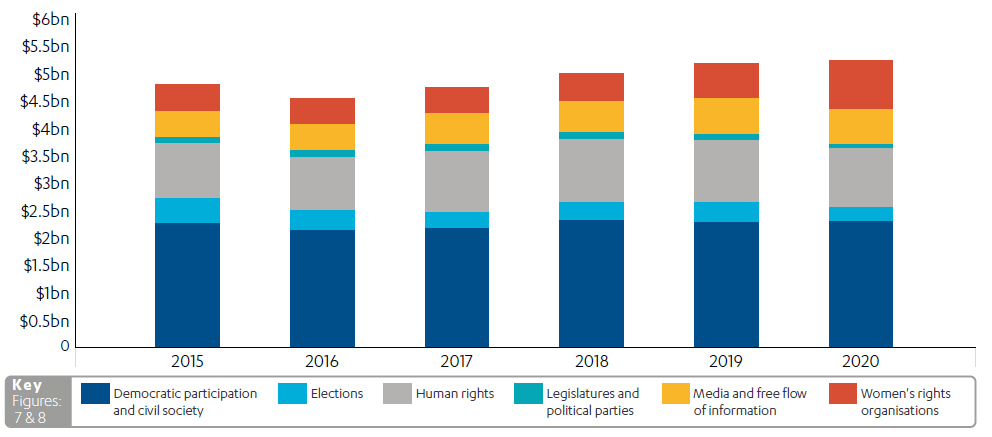

3.16 Democratic participation and civil society is the largest UK thematic area (36%), followed by human rights (24%) and women’s rights organisations (16%). These cover a broad range of activities, usually through CSOs or specialised governmental bodies. Direct democracy assistance represents a smaller share, with funding for elections (13%), and legislatures and political parties (4%). Media and free flow of information interventions (7%) are relevant for both democracy and human rights (see Figure 6).

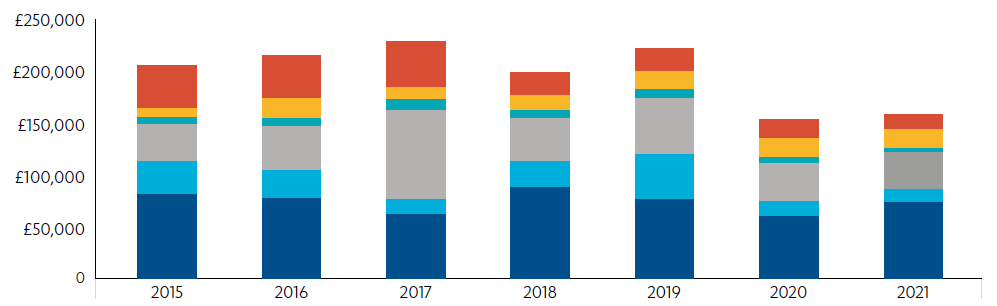

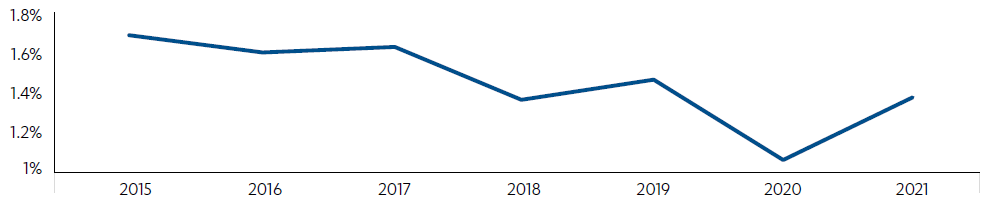

3.17 Following an increase in annual expenditure since 2015 (with a dip in 2018), 2020 saw a reduction of 32.8% (from £220 million to £148 million), as part of the reductions to the overall UK aid budget during COVID-19 (see Figure 7). This is broadly in line with reductions faced by other sectors and thematic areas. Spending remained at a similar level in 2021. Overall UK aid for democracy and human rights increased from 1.1% to 1.4% of total UK official development assistance (ODA) in 2021, indicating some prioritisation relative to other thematic areas, but it was not back to its highest level of 1.7% of ODA in 2015 at the start of our review period (see Figure 10).

3.18 While the UK reduced its expenditure over the period, OECD DAC donors spending increased slightly (see Figure 8). Compared with other bilateral and multilateral donors, the UK is a relative leader in democracy assistance. The UK consistently ranks among the top ten donors for each thematic area during the 2015-20 period. Including BBC World Service funding, the UK provided the second-highest amount for media and free flow of information, with Germany providing the highest. The UK was the third-highest donor for assistance to legislatures and political parties (behind the US and Sweden) and elections (behind the US and the EU), the fourth-highest for women’ rights organisations and the sixth-highest for both democratic participation and human rights.

Table 2: Six thematic areas examined through the review’s sample portfolio

Figure 5: UK thematic ODA expenditure by department or cross-government fund, 2015-21

Source: Statistics in International Development, Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office, 2015-21.

Figure 6: UK ODA expenditure by thematic spending area 2015-21

Note: DFID and FCO funding for 2015-20; FCDO funding for 2021 only; all others for 2015-21.

Figure 7: UK ODA thematic expenditure trends 2015-21

Source: Statistics in International Development, Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office, 2015-21.

Figure 8: OECD DAC bilateral and multilateral donor thematic expenditure trends 2015-20

Source: Creditor Reporting System, Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development, accessed November 2022.

3.19 We reviewed 21 programmes operating at a central level, and in Pakistan, Serbia and Tanzania. The total budget of our sample is £245.7 million.28 Figure 9 provides a summary of the portfolio, with more details in Annex 1.

Figure 9: Overview of the reviewed sample of programmes

Findings

Relevance: Does the UK have a credible approach to using aid to counter threats to democracy and human rights in developing countries?

The UK government has correctly identified the main global threats to democracy and human rights, but its high-level commitments have suffered from some strategic drift, particularly after 2019

4.1 Box 3 summarises the UK government’s main democracy and human rights commitments over the seven-year period covered by our review. They cover a range of thematic areas that were consistent with both ongoing and new threats to democracy and human rights, such as persistent exclusion and discrimination as barriers to poverty reduction, and restrictions on civil and political rights, which are the backbone of liberal democracy. However, they remain at a very high level. Only a few themes during the period, such as gender and governance, benefited from dedicated published strategies.

4.2 The former Department for International Development (DFID) and Foreign and Commonwealth Office (FCO) had different approaches towards democracy and human rights.

- DFID had a long-standing commitment to inclusion and non-discrimination, ‘leave no one behind’ in reference to the poorest and most excluded, women’s and girls’ empowerment, and gender equality as strategies for poverty reduction and prosperity. DFID did not publish democracy or human rights policies and was usually not explicit in its promotion of democracy and human rights, as it often had to collaborate with governments with poor records in those areas in order to implement development programmes. DFID chose to prioritise social and economic rights in its policies, such as the right to education or labour standards, over political and civil rights. It was more comfortable referring to the more neutral-sounding principles of ‘open’, ‘accountable’, ‘inclusive’, or ‘transparent’ governance, rather than democracy, which could be interpreted as imposing a Western political model.

- FCO’s approach to democracy and human rights as foreign policy objectives was part of its commitment to a rules-based international order, including the international human rights system, where FCO represented the UK. Although it had no formal policy document on the subject, FCO’s annual human rights and

democracy reports set out its thematic areas and countries of concern (including Pakistan, one of our case studies). DFID added information on its priority themes and programmes in these annual FCO reports. FCO and now the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO) deliver time-bound

central ‘campaigns’ on themes selected by foreign secretaries. FCO’s main UK aid instruments were the Westminster Foundation for Democracy and the Magna Carta Fund, whose budget doubled in 2016.

4.3 DFID and FCO approaches can be seen as complementary, rather than contradictory. Thanks to its human rights and legal advisers, FCO had a better understanding of the legal dimension of human rights, including the obligations of state actors. DFID programmes worked to empower the poorest and members of at-risk social groups to claim their rights and hold governments to account through political, media or social channels.

4.4 The preferences of UK prime ministers have shaped UK aid priorities on democracy and human rights. For example, David Cameron championed ‘open societies’, while Theresa May paid special attention to ‘modern slavery’, which she had also prioritised as home secretary.

4.5 DFID, FCO and FCDO have seen a rapid turnover of ministers: there have been six international development secretaries of state (SoS) between 2015 and 2020, six foreign secretaries between 2015 and 2022, and two ministers of state for development in 2022. This has resulted in frequent changes in the focus of central priorities and programmes, reflecting the preferences of different ministers.

4.6 For example, under SoS Justine Greening (2012-16), democracy and human rights were conceptualised by DFID in terms of processes of ‘empowerment and accountability’, which would enable poor and excluded people to gain ‘voice, choice and control’. This framing was no longer used under SoS Priti Patel (2016-17), who was sceptical of media programmes and ended core funding for civil society organisations (CSOs). DFID central initiatives instead focused on specific rights or principles, such as people with disabilities, a new objective introduced under Priti Patel. This continued under SoS Penny Mordaunt (2017-19), who also prioritised transparency and media freedoms.

4.7 FCO/FCDO similarly pursued different ministerial thematic interests over the review period. For example, as foreign secretary, Boris Johnson (2016-18) prioritised girls’ education and LGBT+ rights, whereas media freedom and freedom of religion or belief (especially in terms of the persecution of Christians) became campaigns under foreign secretary Jeremy Hunt (2018-19). Foreign secretary Dominic Raab (2019-21) continued these themes. There was increased funding and staffing on LGBT+ issues but the campaign faced political challenges, such as repeated delays and then the cancellation of the ‘Safe To Be Me’ global conference in 2022.

4.8 DFID/FCDO relies on its governance and social development advisory cadres to analyse global and country contexts, identify emerging threats and opportunities, and design relevant strategies and programmes. These cadres provide complementary technical perspectives; while the former looks at institutions, the latter puts people at the heart of their analysis. Both perspectives are needed to ensure that citizens can claim their rights and state authorities can better respond to their demands. FCO/FCDO human rights advisers and research analysts provide expertise in international legal standards, the workings of the multilateral system, and individual country contexts.

4.9 In 2019 alone, DFID had three secretaries of state and FCO two foreign secretaries, which contributed to some strategic drift from that time onwards, as no strategic direction was agreed for long enough to be operationalised. For example, despite the 2021 Integrated review commitments or the December 2021 ‘network of liberty’ speech, in December 2022 the foreign secretary did not explicitly mention democracy, human rights, ‘open societies’ or ‘network of liberty’ objectives as part of his new UK foreign policy offer.

4.10 In the Coherence section, we review how FCDO attempted to bring together DFID and FCO approaches under an ‘open societies’ framing.

The UK approach is supported by high-quality technical expertise, diagnostic tools and analysis

4.11 DFID diagnostics included mandatory country-level political economy analyses to inform country strategies, and the approach is still used by FCDO in sectoral or issues-based analyses. These enable advisers to understand why democracy and specific rights are under threat and to propose politically feasible solutions (an approach known as ‘thinking and working politically’). Our interviews with other donor agencies and independent experts indicate that DFID was seen as a thought leader in this more politically informed approach to development challenges.

4.12 When designing programmes, advisers can also rely on guidance notes prepared by central teams, such as the 2018 joint DFID/FCO guide on assistance to parliaments and political parties, the 2019 Gender How to Note or the 2021 Disability Inclusion How to Note. However, central guidance was not always produced in a timely way. For example, the UK government correctly identified closing civic space as a new challenge, but as ICAI’s 2019 civil society partnership review found, it has been slow to respond with central guidance. FCDO only issued its toolkit on the subject in 2022.

“The strengths of DFID had to do with the fact that the organisation contained a lot of sophisticated thinking about development. Its agenda was well-grounded empirically and there was a lot of commitment in DFID to research/evidence. It was impressive. People were searching for answers in a serious way. It was a culture of thinking and applying thinking to action. The quality of DFID personnel was high in terms of intellectual capacity and professional success.”

Implementing partner

4.13 At the beginning of the review period, there was limited evidence of ‘what works’ to promote democracy and human rights, especially in the context of democratic backsliding and closing civic space. DFID rightly invested in improving the evidence base. DFID’s policy departments funded relevant research with universities and think tanks. Policy teams, heads of profession and the chief economist’s office produced evidence guides and value for money ‘best buys’, including on social accountability, elections, democracy, information and inclusion. During the review period, an external resource centre responded to staff queries and produced topic and learning guides.

4.14 DFID also invested in research programmes that generated evidence on aspects of the democracy and human rights agenda. For example, the Action for Empowerment and Accountability programme (£6.3 million, 2016-21), based at the Institute for Development Studies in the UK, examined social and political action in fragile and conflict-affected countries. There is some evidence that UK aid-funded research influenced some country programmes, but it has not been central to FCDO’s ‘open societies’ strategy development. DFID’s Research and Evidence Division (RED) framed the governance and development agenda more broadly than democracy and human rights. It was only following the merger, in 2022, that RED commissioned an evidence gap review on freedom and democracy and an evidence assessment on international norms and rules. FCO did not commission external evidence on ‘what works’ to support change to the same extent as DFID.

UK aid interventions addressed the most important threats to democracy and human rights by balancing changing ministerial priorities and country analysis, but the need to maintain access to governments has caused some risk aversion

4.15 We find that DFID central programmes responded appropriately both to ministerial thematic priorities and to threats and opportunities identified in individual countries. For example, Aid Connect (£99 million, 2017-24) funded civil society coalitions on a multi-annual basis, including on the central campaign themes of media freedom and freedom of religion or belief in countries or regions where they were most at risk, including in Pakistan, North Africa and the Middle East. The Magna Carta Fund (£55 million, 2015-21) requested proposals from across the FCO/FCDO network on centrally determined themes, such as media freedom, LGBT+ rights and the death penalty. FCO/FCDO teams then sought to develop one-year projects with their local partners or international organisations such as the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR). Central programmes, such as the Westminster Foundation for Democracy, were not always a priority for DFID country teams, which had the resources to fund country-based priorities, but they offered a useful source of funding and diplomatic access for FCO teams.

4.16 Central and country programmes made good use of local research and undertook consultations, for example with CSOs working with at-risk groups. National staff working within UK country teams were a key resource, given their local knowledge, extensive networks with state and non-state partners, and their longer period in post than UK-based advisers.

“Before Aawaz, our voices were not heard. Our demands would get lost and, in the end, would not be catered to.”

Religious minority participant, Mansehra focus group discussion, Pakistan

“CHAVITA has sensitised the police and hospital through media on how to address the challenges that Deaf people face when trying to communicate with them.”

Deaf participant, Dar es Salaam focus group discussion, Tanzania

4.17 As country programmes were designed around ministerial priorities, country teams had to ‘localise’ their response – that is, translate UK priorities into locally appropriate themes and identify the most suitable partner organisations. See Box 4 for an example from Pakistan.

Box 4: Adapting central priorities to the local context in Pakistan

The first phase of the Aawaz programme in Pakistan (£39 million, 2012-18) focused on voice, accountability and inclusion of at-risk groups. Its second phase (£49 million, 2018-27) was required to also address modern slavery, a UK priority since the 2015 UK Modern Slavery Act. The DFID country team worked with local CSOs to unpack the elements of modern slavery in Pakistan. They identified child labour, child and forced marriage and gender-based violence, which were prevalent and were better understood by local stakeholders than the term ‘modern slavery’. They concluded that highlighting health risks would be a better entry point to campaign against child marriage.

Given the sensitivities associated with human rights in Pakistan, and the increased restrictions faced by civil society, DFID also decided to collaborate with UNICEF and UNFPA in this second phase. These partners had access to the Pakistani government, and were seen as neutral and expert organisations. Aawaz II funded these UN agencies, among other things, to undertake research to develop evidence-based approaches, such as a political economy analysis of child marriage, a gender parity report and the first survey on child labour since 2006 in Punjab.

4.18 UK aid programmes did not always address all the main threats to democracy and human rights identified in country analysis, despite the quality of diagnostics, practical guidance, evidence and local networks available to DFID and FCO teams. This was due to a range of factors, in particular a desire to maintain access to governments which has led to trade-offs in supporting and defending democracy and human rights. Other factors include the reduction of UK aid budgets, and practical challenges with finding the right partners in closed political contexts. We provide examples from our three country case studies below.

4.19 In Pakistan, during a period of democratic backsliding, growing civil society and media restrictions and increasingly populist politics, the UK government decided to deprioritise democracy objectives. The Conflict, Stability and Security Fund (CSSF) Consolidating Democracy in Pakistan programme (£33.5 million, 2016-21) was extended in 2020 to respond to COVID-19 but not renewed. While it was an appropriate choice to cease funding for the electoral commission (as it had made technical progress and further UK aid would not improve forthcoming elections), this decision left FCDO without a significant mechanism to respond to political openings or further democratic backsliding. The CSSF Open Societies Programme (£3.4 million, 2021-25) provided proportionately much less for democracy initiatives with media and on civic space (£942,000). In a context of continuous aid budget reductions since 2020, FCDO in Pakistan has prioritised gender inclusion and freedom of religion or belief, rather than democracy, which is a more sensitive topic with the government, yet is needed if inclusion and human rights are to be protected on a more sustained basis.

4.20 The International Development Committee identified inclusion as a priority for UK aid to Pakistan, including the rights of women and girls, people with disabilities, religious minorities, and LGBT+ people. It called on FCDO to “direct its bilateral ODA spending in Pakistan strategically towards supporting marginalised groups reach their full potential” and to ensure that its programmes are “fully inclusive”.

4.21 In Tanzania, the UK did not fund media freedom or media sector development programmes despite identifying media freedom as a critical issue, as it was unable to find suitable implementing partners. Our analysis found that the main civil society programme, Accountability in Tanzania 2 (£24.2 million, 2017-22) did not help the most at-risk journalists, while other donors were able to provide assistance to protect journalists, indicating a higher risk tolerance on this issue. UK aid grants to BBC Media Action helped to create platforms on local radio to hold officials to account, but did not protect media freedoms or support media sector development.

4.22 In Serbia, local embassy staff used their own knowledge of the context and excellent networks to develop a portfolio of projects funded through three regional CSSF programmes. This included partnerships with the government on some issues of mutual interest, such as data transparency. We found that the portfolio was relevant overall, but that the UK government, despite having a £2.7 million media portfolio, appears to have been slow to respond to the growth of hate speech and disinformation, which were well-known threats in Serbia.

UK programmes prioritised excluded social groups, but found it harder to assist LGBT+ people

4.23 UK aid promoted and protected the rights of the most at-risk groups, identified through a combination of ministerial priorities and country analysis. Box 5 describes groups that were supported in our case study countries. The list reflects DFID’s long-standing commitments to gender equality and inclusion, combined with FCO’s concern with specific groups at risk of human rights violations, such as religious minorities, LGBT+ people and death row detainees. It reflects guidance requiring gender and inclusion to be mainstreamed in programme designs, as well as the UK public sector equality duty.

4.24 Consultation with FCDO’s international partners confirms that the UK is seen as a global leader on gender and inclusion, in particular its support for ‘leaving no one behind’ and defending the rights of people with disabilities, which became a DFID priority in 2017. Civil society programmes (such as Aid Connect, Aawaz in Pakistan and Accountability in Tanzania) generally find it easier to target excluded social groups than governance programmes. Civil society programmes are usually designed and implemented by social development experts who pay particular attention to poverty, gender and social inclusion, and are implemented by local civil society partners who can reach these groups.

4.25 However, as a result of a shift in DFID governance policy, democratic governance programmes also improved their inclusion focus. This was visible in the Westminster Foundation for Democracy (WFD) assistance to parties and parliaments, which promoted women’s political empowerment more systematically after it began its combined FCO/DFID Supporting Effective Democratic Governance programme (£19.8 million, 2015-18). Inclusion became an official objective of the second DFID programme, Inclusive and Accountable Politics (£11.8 million, 2018-21). WFD also increased its focus on youth, people with disabilities and LGBT+ people during the period. The WFD Western Balkans Democracy Initiative (£3.7 million, 2019-22) prioritised the issue of distrust in politics and youth migration.

4.26 FCO made LGBT+ people a central priority, with support for a global equality alliance, commitment to a global conference, CSSF central funding to reform discriminatory Commonwealth legislation, Magna Carta Fund allocations and ongoing diplomatic activities. It was one of the top donors on LGBT+ issues in 2019-20.34 However, the programmes in our sample generally found it challenging to support LGBT+ communities, partly because of the risk of doing harm while trying to support them. In Tanzania, legal restrictions, discriminatory statements by authorities, conservative social norms and fragile civil society groups made LGBT+ people a particularly difficult group to assist. The UK did not manage to design any relevant bilateral interventions, while other donors were able to do so, despite substantial risks to their diplomatic relationships with government. In Pakistan, programmes were able to support transgender people, who are a recognised social group, but not the wider LGBT+ community, which faces legal restrictions and social stigma. In Serbia, there were some regional activities and diplomatic engagement, but the theme was not prioritised. The Aid Connect LGBT+ consortium was slow to establish itself because of DFID’s due diligence requirements, by which time funding was cancelled as a result of reductions in the UK aid budget.

Box 5: Prioritisation of at-risk groups in our case study countries

The social groups assisted by UK aid programmes in our sample of country programmes usually corresponded with those identified as most at risk in consultations with local experts and communities.

However, some groups and issues were seen as too sensitive for the UK aid programmes.

- Women and girls, people with disabilities, and youth were the groups most commonly prioritised by UK aid democracy and human rights programmes.

- Ethnic and religious minorities were prioritised in Pakistan.

- LGBT+ people were less often prioritised. Transgender people in Pakistan are a socially defined group, so work was feasible. The issue was too sensitive for projects in Tanzania and feasible but less prioritised in Serbia. The following were in general much less prioritised or mainstreamed in our sample of country programmes:

- Elderly people.

- Indigenous peoples.

- Refugees, despite important refugee populations in Pakistan and Tanzania.

Before 2020, UK aid programmes adapted well in response to changes in context or lessons learned, but there were missed opportunities for cross-portfolio learning

4.27 The theories of change in the programmes we reviewed were not always of high quality initially. For example, the CSSF Consolidating Democracy in Pakistan programme assumed there would be democratic political space in which to operate, whereas soon after it started the political context became more restricted. It invested heavily in supporting the conduct of elections, without investing enough in democratisation between elections – a common and well-documented weakness of electoral programmes.

4.28 However, theories of change and implementation strategies usually improved during implementation when programme management allowed for adaptation. For example, improvements were seen during the ‘co-creation’ phases for Aid Connect and Accountability in Tanzania 2, which gave civil society consortia time and money to undertake deeper analysis and adjust their activities. DFID designed several programmes with problem-based approaches, such as the Tanzania Institutions for Inclusive Development (£13 million, 2015-21), the WFD Western Balkans Democracy Initiative and the Pakistan Open Societies Programme. Political economy analyses during both the inception and implementation phases enabled these programmes to enhance their relevance by selecting salient issues around which to build coalitions for change.

4.29 Portfolios and programmes were able to adjust in response to changes in context. DFID Tanzania increased its use of political economy analysis following the election of President Magufuli in 2015, as it progressively realised that political space was closing and it would have to adjust its portfolio. In response to COVID-19, programme extensions or new activities allowed programmes to pivot.

4.30 We found that most programmes were able to remain relevant by learning during implementation (see Box 6). We found three weaker aspects of learning:

- The Magna Carta Fund was not designed or managed centrally with the capacity to learn and disseminate lessons systematically from its £55 million portfolio. This is a missed opportunity to learn about ‘what works’ within short and relatively small projects.

- We found little evidence of learning between democracy and human rights programmes within the same country portfolios, even though they were responding to similar challenges and sometimes had the same local counterparts.

- Central learning (between central programmes or across countries) was also weak. Apart from the 2016 empowerment and accountability macro-evaluation, UK aid has not invested in global thematic democracy or human rights evaluations, although it funded some regional thematic evaluations.

Box 6: Ensuring ongoing relevance by generating evidence

Some UK aid programmes generated evidence on citizens’ priorities. In Pakistan, Aawaz’s Aagahi centres provide at-risk communities with information on their rights and connect them to social services. In Serbia, the CSSF Media for All programme (£1.8 million, 2019-23) developed an ‘engaged citizens reporting’ tool, an online platform through which media outlets ask their audiences about topics of interest, to guide their programming choices.

Across our sample, UK aid programmes generated evidence that was used to adjust their approach either following a mid-term review or when moving to a successor programme. In Pakistan, Aawaz II included partnerships with state authorities, which had been absent from Aawaz I, limiting the programme’s ability to respond to citizens’ demands. In Serbia, the larger Media for All programme scaled up learning from smaller civil society projects led by the Balkans Investigative Reporting Network. The UK government funded a £500,000 independent developmental evaluation of the Open Government Partnership, which helped its secretariat navigate political realities, analyse bottlenecks and identify suitable partners. UK aid programmes themselves generated evidence which was used by other UK aid programmes or as global public goods. For example, the Westminster Foundation for Democracy evidence hub produces and disseminates research on issues which have been less investigated, such as the role of money in politics.

Aid budget reductions and loss of expertise have left the portfolio less responsive to democracy and human rights challenges and not well-matched to FCDO’s high-level policy ambition

4.31 Our interviews and document review showed that FCDO’s draft ‘open societies’ strategy, developed during 2021 to support implementation of the Integrated review, had limited influence on programming. Most interviewees who tried to use it to guide their work in the absence of an approved strategy saw it as conceptually very broad, without clear delivery mechanisms and without the budgetary resources to match its ambition. From December 2021, foreign secretary Liz Truss’s ‘network of liberty’ speech provided a different policy framing. It put freedom and democracy at the heart of a new geopolitical strategy against authoritarian states, at the same time as UK aid budget reductions left FCDO with sharply reduced funding for democracy and human rights programming. The May 2022 International development strategy did not prioritise ‘open societies’ but refers to some of its elements such as freedom, democracy and women’s rights. None of these three documents offer clear strategic direction on democracy and human rights. With the change of foreign secretary in September 2022, discussion of a revision of the Integrated review, and a ‘pause’ of the UK aid programme for several months during 2022, there is more uncertainty. The Effectiveness section provides more details on budget predictability and reductions.

4.32 Finally, some FCDO interviewees in headquarters and in-country expressed the view that the department does not value technical development expertise to the extent that DFID did. This was also the perception of some external partners. The governance cadre seems more affected than the social development cadre: between April 2020 and April 2022, 13% of governance advisers employed in governance roles have taken up generalist positions or left FCDO. This included one-fifth of senior governance advisers and one-third of country-based governance advisers.

4.33 The combined impact of the budget reductions and the loss of expert personnel is that the UK democracy and human rights portfolio is now not as well positioned to respond to its high policy ambitions, or to new threats or opportunities emerging at the international level, as it was earlier in the review period.

Conclusions on relevance

4.34 During the first part of the review period, UK aid had the expert staff and systems in place to ensure democracy and human rights programmes were relevant. Programmes balanced a response to specific threats, changing thematic ministerial priorities and the need to maintain access to partner governments, which at times made them risk-averse. They increasingly prioritised the most excluded social groups and developed politically informed approaches, maintaining their relevance through good-quality contextual analysis and in-programme learning – although we noted missed opportunities for cross-portfolio learning. However, UK aid budget reductions and the ongoing consequences of the DFID/FCDO merger on the use of expertise make it difficult to conclude that the portfolio still retains its agility to respond to new challenges and deliver on the UK government’s high policy ambitions. Given the strengths of the portfolio for most of the review period, we award a green-amber score for relevance.

Coherence: How coherent is the UK’s approach to countering threats to democracy and human rights?

4.35 We reviewed the democracy and human rights portfolio in terms of cross-government coherence (in particular the combination of development and diplomatic resources) and donor coordination.

UK support to democracy and human rights has benefited from complementary development and diplomatic interventions

4.36 We found consistent evidence, including before the merger, that UK aid central and country democracy and human rights initiatives have benefited from the combination of diplomatic engagement and aid spending. Table 3 provides some examples from central programmes.

4.37 UK aid and diplomatic objectives are often mutually reinforcing. UK aid programmes can ask for diplomatic support to unblock problems. This includes behind-the-scenes dialogue between UK diplomats and senior government officials to explain the negative impact of laws restricting media or civil society activities. Conversely, substantial UK aid budgets often increase diplomats’ access to governments. Smaller aid portfolios, such as the CSSF in Serbia, can also provide influence when the projects are perceived to be relevant and of high quality.

Table 3: Illustrations of the mutually beneficial diplomatic and programme efforts

Coherence and coordination between DFID and FCO were ‘good enough’ before the merger

4.38 In the Relevance section, we noted that the differences in approach to democracy and human rights between DFID and FCO were generally complementary, rather than contradictory. Interviewees identified three areas of tension between development and diplomacy approaches, which the merged department now needs to address. Development assistance typically focuses on poverty reduction, works across longer timeframes for social and institutional change, and aims to support locally defined priorities. In contrast, diplomacy tends to operate with shorter timeframes and with a focus on delivering the UK’s wider policy objectives.

4.39 Before the creation of FCDO, there were appropriate coordination structures in place in the UK and at country level to manage these complementarities and tensions. DFID and FCO each drew on the other’s expertise when needed, for example in relation to elections or the workings of particular international bodies. The CSSF was able to fund interventions of mutual DFID/FCO interest, especially when they were seen as risky (from a political or security perspective) or were in locations where DFID had no country presence. Box 7 provides examples.

Box 7: Examples of coordination mechanisms between aid and diplomacy

Most of the Serbia democracy and human rights portfolio was funded through three CSSF programmes, of which only one, the Good Governance Fund, was implemented by DFID. The portfolio was managed by the UK embassy in Serbia, with well-networked local staff and support from DFID governance and economic advisers based in the UK.

In Pakistan, UK aid support for elections after 2016 was delivered through the CSSF Consolidating Democracy in Pakistan programme, managed jointly by DFID and FCO. Its predecessor programme had been DFID-funded, but the then international development secretary of state considered political governance too high a risk for DFID. UK aid provided funding for the 2015 Tanzania and 2018 Pakistan elections through United Nations Development Programme multi-donor trust funds, and UK diplomats were involved in election monitoring. The decision not to fund the 2020 elections due to electoral fraud risks in Tanzania was taken jointly by DFID and FCO teams in preceding years, but FCDO staff still monitored the 2020 elections.

FCO’s UK diplomatic delegations to human rights bodies in Geneva and New York advance UK aid gender and inclusion policy objectives. DFID advisers provided lines to take, for example at the UN Commission on the Status of Women. Conversely, FCO called on DFID expertise to advance the then foreign secretary Boris Johnson’s priority of girls’ education.

The 2018 first global conference on disability inclusion was co-chaired by the UK and Kenya. It would not have been possible without close DFID coordination with FCO’s diplomatic network. At Commonwealth Heads of Government meetings, FCO delegates ensured progressive language on disability inclusion, pushing back against the institutionalisation of people with disabilities. FCO also appreciated DFID technical contributions on disability inclusion in cross-government forums.

The potential of the FCDO merger to bring diplomacy and development further together on democracy and human rights has yet to be fully realised