The UK’s approach to safeguarding in the humanitarian sector

Score summary

The UK government has increased international attention to protection from sexual exploitation and abuse (PSEA) in the humanitarian sector but should reinforce systems for consultation with affected people, especially victims and survivors of sexual exploitation and abuse (SEA), so their views are consistently used to learn ‘what works’ and inform prevention of and response to SEA

In the wake of high-profile safeguarding incidents that emerged in 2018, the UK government has increased attention to the issue internationally and has added impetus to efforts to tackle sexual exploitation and abuse (SEA) by humanitarian workers at local levels. The UK’s strategy is wide-ranging and rightly acknowledges that reducing SEA in international aid will take long-term, sustained efforts. However, the approaches adopted by the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO) place particular emphasis on accountability towards the department itself, putting accountability towards affected people, particularly victims and survivors, at risk of being deprioritised. This, and the need to reinforce systems for routinely consulting with, and learning from, affected people, are important weaknesses that need to be addressed.

Since hosting the 2018 international safeguarding summit, the UK has become a key actor whose investments and leadership have been instrumental in strengthening coordination on PSEA. FCDO is working collaboratively with a range of partners to increase coherence within the humanitarian sector and to drive up standards. There is, however, a need to solicit the voices of victims and survivors more actively, both in high-level forums and on a day-to-day basis in humanitarian response operations, and to strengthen information sharing and reporting on SEA.

FCDO has made extensive efforts to reinforce minimum standards both within the department and for its implementing partners. This has contributed to increased awareness and a focus on improved staff conduct. However, insufficient funding for partners’ core costs, particularly for smaller organisations, can limit their ability to establish systems for prevention and response. Significant under-reporting of SEA incidents, particularly among affected populations, continues to be a challenge despite increased efforts to encourage reporting. FCDO has made significant investments in systems for investigating reported safeguarding cases. However, we found that their own investigations case management system was not calibrated to prioritise reports of SEA perpetrated against affected populations and that there were gaps in FCDO’s internal guidance, including on protecting whistleblowers and on ensuring due process and protection of the rights of the accused (improvements have since been made).

FCDO’s support to employee screening schemes that aim to prevent perpetrators from being given the opportunity to reoffend has not yet been fully realised. Neither have the department’s aims to ensure that victims and survivors consistently receive survivor-centred responses and adequate support. Many of the measures are at an early stage of implementation and there is as yet limited evidence to show that the measures taken have reduced the risk of SEA for people affected by humanitarian responses.

Individual question scores:

- Relevance: How well has the UK government gone about building a relevant and credible portfolio of safeguarding programmes and influencing activities? AMBER/RED

- Coherence: How well does the UK work with other donors and multilateral partners to ensure a joined-up global approach to protection from sexual exploitation and abuse? GREEN/AMBER

- Effectiveness: How effective is the UK’s approach to protection from sexual exploitation and abuse at programme, delivery partner and sector-wide levels? AMBER/RED

Acronyms and glossary

| Acronyms | |

|---|---|

| ACRO | ACRO Criminal Records Office |

| AAP | Accountability to affected populations |

| CATI | Computer-Assisted Telephone Interview |

| CHASE | FCDO Conflict, Humanitarian and Security Department |

| CHS | Core Humanitarian Standard on Quality and Accountability |

| CSO | Civil society organisations |

| CSSG | Cross-Sector Safeguarding Steering Group |

| DFID | Department for International Development (merged with the Foreign and Commonwealth Office in September 2020) |

| DRC | Democratic Republic of the Congo |

| FCDO | Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office |

| FCO | Foreign and Commonwealth Office (merged with the Department for International Development in September 2020) |

| FRRM | Feedback, Referral and Resolution Mechanism |

| GBV | Gender-based violence |

| IASC | Inter-Agency Standing Committee |

| IDC | International Development Committee |

| IDP | Internally displaced person |

| LGBTIQ+ | Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans, Intersex, Queer plus (all other gender and sexual orientations) |

| MDS | Misconduct Disclosure Scheme |

| NGO | Non-governmental organisation |

| OCHA | United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs |

| ODA | Official development assistance |

| OECD DAC | Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development’s Development Assistance Committee |

| PSEA | Protection from sexual exploitation and abuse |

| RSH | Resource and Support Hub |

| SCHR | Steering Committee for Humanitarian Response |

| SDG | Sustainable Development Goal |

| SEA | Sexual exploitation and abuse |

| SEAH | Sexual exploitation, abuse and harassment |

| SIT | Safeguarding Investigations Team |

| UNHCR | he United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, the UN Refugee Agency |

| WHO | World Health Organisation |

| Glossary | |

|---|---|

| Accountability to affected populations | Accountability to affected populations (AAP) is an active commitment by humanitarian actors to use power responsibly by taking account of, giving account to, and being held to account by the people they seek to assist. |

| Do no harm | The principle of ‘do no harm’ applies to all development and humanitarian organisations. It requires them to strive to minimise the harm they may inadvertently cause through providing aid, as well as harm that may be caused by not providing aid. |

| Downstream partner | Any person, organisation, company or other third-party representative contracted throughout the humanitarian aid delivery chain (see below). |

| Humanitarian aid delivery chain | In humanitarian relief operations, logistics and supply chain management are a critical component to ensure that goods and services reach affected people. Challenging environments require the engagement of various stakeholders such as governments, the military, civil society, private companies, and international and national relief organisations, which all form part of the delivery chain for humanitarian aid. |

| Humanitarian assistance | Humanitarian assistance is intended to save lives, alleviate suffering and maintain human dignity during and after man-made crises and disasters caused by natural hazards, as well as to prevent and strengthen preparedness for when such situations occur. Humanitarian assistance should be governed by the key humanitarian principles of humanity, impartiality, neutrality and independence. |

| Localisation | Localisation is a process of recognising and delegating leadership and decision-making to national actors in humanitarian action. Pooled funds Pooled funds, contributed to by multiple donors, are used to finance joint interventions that are managed by humanitarian agencies which deliver programmes on behalf of the contributing donors. |

| Refugee Convention | The 1951 Convention relating to the Status of Refugees and Stateless Persons (commonly known as the Refugee Convention) is the main international treaty concerning refugee protection. The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees serves as the ‘guardian’ of the 1951 Convention and its 1967 Protocol. |

| Survivor-centred approach | Ensuring that prevention of, and response to, SEA are non-discriminatory and respect and prioritise the rights, needs and wishes of survivors, including groups that are particularly at risk or may be specifically targeted for sexual exploitation, abuse and harassment. |

| Whistleblowing | Whistleblowing is the process whereby an employee or other stakeholder raises a concern about SEA or a risk of harm to other employees, aid workers, those intended to benefit from aid, or the wider community. |

Executive summary

The sexual exploitation and abuse (SEA) by humanitarian workers of people they have a duty to support is a persistent problem in the humanitarian sector. Lack of robust data means that the scale and scope of the problem is unknown. Despite reforms dating back to 2002, prompted by a ‘sex-for-aid’ scandal in West Africa, SEA is still believed to be widespread in the sector.

This review examines the extent to which the UK government’s safeguarding efforts have been effective in preventing and responding to SEA in humanitarian aid contexts. It considers programming, policy and influencing activities by the UK government between 2017 and 2021, the years straddling the October 2018 international safeguarding summit hosted by the UK (known as the ‘London summit’) where the UK and other key actors made significant commitments to sectoral reform. The review looks at whether the UK government has built a relevant and credible portfolio of safeguarding programmes and influencing activities, and assesses the extent to which the portfolio is having an impact on the problems it seeks to address. It also assesses how well the UK works with others to promote a joined-up global approach to addressing the challenges of preventing, detecting and responding to SEA.

Relevance: How well has the UK government gone about building a relevant and credible portfolio of safeguarding programmes and influencing activities?

The UK-hosted 2018 London summit played an important role as a catalyst for change, focusing international attention in the humanitarian sector on addressing SEA and adding impetus to efforts at local levels. The UK’s strategy, developed in 2020, is wide-ranging, setting out four ‘strategic shifts’ that reflect a broad consensus on priorities in the humanitarian sector: to ensure support for survivors, victims and whistleblowers, to incentivise cultural change, to adopt global standards, and to strengthen organisational capacity and capability across the humanitarian sector to meet these standards. The strategy appropriately includes a mix of short- term and long-term measures, acknowledging that addressing SEA in international aid will take sustained efforts over time.

The UK’s safeguarding strategy was developed based on wide consultation but would benefit from reinforced systems for ensuring that consultation with crisis-affected people, especially victims and survivors of SEA, informs both policy and prevention and response efforts. The London summit was preceded by a ‘listening exercise’, but more than three years on, a planned follow-up to this has not yet taken place. At country level, there are limitations to donors’ ability to engage directly with people at risk of SEA and, like other donors, the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO) relies largely on implementing partners to relay information from their consultations with affected people. Efforts should be reinforced to ensure that such information is continuously solicited, analysed and shared by FCDO to improve their partners’ programming, and their own strategy and approach.

The UK’s strategy of seeking change at both the international level of the humanitarian system and at the delivery level in country is relevant, but the balance between the two is overly skewed towards the former. The UK has made substantial investments to improve protection from sexual exploitation and abuse (PSEA) in the wider humanitarian system, supporting development of guidance and training, the establishment of international systems for information sharing on SEA, and sector-wide tools aiming to prevent perpetrators of SEA from being rehired by other humanitarian organisations and donor governments. International systemic change is both important and necessary, but it is a long-term endeavour. Both the magnitude of change and the extent to which it has become embedded in humanitarian response remain to be seen. There is a risk that FCDO’s focus on the systemic level, coupled with its emphasis on partners’ compliance with minimum standards, reinforces a top-down approach that may reduce the space for local-level initiatives that could deliver more contextualised results.

FCDO has invested substantially in the creation of a Safeguarding Investigations Team, which has a mandate to ensure a survivor-centred response to safeguarding incidents involving members of staff and recipients of FCDO funding. The department has made a significant effort to enable accountability when complaints are made in UK-funded programmes. However, the design of the case management system made it difficult to identify cases of abuse against affected populations, limiting FCDO’s ability to focus its attention on cases involving the most vulnerable. It is important to be able to identify these victims and survivors, as they are often those most at risk of all forms of abuse and least likely to have their voices heard. We note that FCDO took action to remedy this defect in response to the questions raised by our safeguarding investigations study.

The UK has invested in highly relevant measures to develop the humanitarian sector’s capacity and capability, and to build an evidence base. However, a targeted strategy is needed to address serious and widely recognised evidence gaps on where, when and how SEA takes place in humanitarian settings, who is most at risk, and the short- and long-term effectiveness of current prevention and response measures.

The UK has got many things right in developing a wide-ranging strategy for safeguarding in the humanitarian sector based on extensive consultation with a broad range of stakeholders. However, the approaches adopted place particular emphasis on accountability from operational levels towards the international level, especially the donors, putting accountability towards affected people, particularly victims and survivors, at risk of being deprioritised. This, and the need to reinforce systems for routinely consulting with, and learning from, affected people, are important weaknesses that need to be addressed. We therefore award an amber-red score for relevance.

Coherence: How well does the UK work with other donors and multilateral partners to ensure a joined-up global approach to protection from sexual exploitation and abuse?

Since 2018, when the UK committed to stepping up action on SEA at the London summit, it has become one of the leading global actors on PSEA. While the UK’s initial activities drew substantially on domestic safeguarding policies and practice, it quickly aligned its approach with established terminology and processes in the international humanitarian sector around PSEA. FCDO investments have been instrumental in strengthening coordination on PSEA, and the department is working collaboratively with a range of partners to increase coherence within the humanitarian sector and improve standards.

The UK has built an effective network of donors and partners, using its convening power to wield influence and provide practical coordination support. However, there is a need to solicit the voices of victims and survivors more actively, both in high-level forums and on a day-to-day basis in humanitarian response operations. While the UK has worked to strengthen information sharing and reporting on SEA, we found that important weaknesses and gaps exist in global information sharing, which undermine transparency and accountability. The lack of robust timely data on confirmed incidents of SEA, which are essential for understanding when, where and how exploitation and abuse is taking place, makes the task of reducing risks to vulnerable people much harder.

Although there remain important areas where the coherence of the international effort should be improved, particularly data sharing, the UK government has shown strength and leadership. We therefore award a green-amber score for coherence.

Effectiveness: How effective is the UK’s approach to protection from sexual exploitation and abuse at programme, delivery partner and sector-wide levels?

Reinforcement of minimum standards has improved the quality of PSEA programming, but insufficient funding for core costs undermines effectiveness, particularly for smaller organisations. Since 2018, FCDO has taken measures aiming to ensure that staff and partners are consistently held to a minimum standard on SEA. The department has introduced mandatory e-training for all FCDO staff and role-specific training as required.

It has also developed a Safeguarding Champions network of 85 staff at different levels of seniority, which provides important day-to-day support and ensures that safeguarding remains on the agenda. An SEA risk management capacity has been developed within the department, which requires the logging of SEA risks for each operational context.

FCDO has also imposed requirements and minimum standards on implementing partners, reinforced by training. Partners told us that the department has supported improved awareness and capability among programme staff. However, the implementation of FCDO’s requirements demands additional investments in training, monitoring, establishment and maintenance of complaints mechanisms, and investigations. FCDO funding has not always been made available to cover these costs, which is a particular problem for smaller national and local organisations.

Reporting of SEA incidents remains low, particularly among people affected by humanitarian emergencies, despite heightened attention to SEA and increased work to encourage reporting. Our telephone survey of people affected by the humanitarian response in Uganda revealed a reluctance to use aid agencies’ SEA reporting or referral mechanisms. Our study of FCDO’s own reporting mechanisms showed that the department’s wide definition of safeguarding, extending beyond sexual exploitation, abuse and harassment (SEAH), coupled with the way it filtered and selected cases for follow-up, means it has been overwhelmed with cases. The investigations case management system was not calibrated to prioritise reports of SEA perpetrated against affected populations and there were gaps in FCDO’s internal guidance available in spring 2021, including on protecting whistleblowers and on ensuring due process and protection of the rights of the accused.

Basically, you are going to report, but the length of the process is going to be so tedious you may even give up along the way and the people you’re reporting to may be corrupt and fail to attend to you because they have the bigger man on their side. They are corrupt because of their positions and there is also fear to be exposed to the community and be looked at as a victim

To me it’s three out of ten that report because people fear being stigmatised. Even when it happened to me, I didn’t report to anyone, just talked to my two friends, because most times people may not even believe you.

Members of affected communities, Northern Uganda

The UK has made substantial investments in initiatives to prevent perpetrators from being given the opportunity to reoffend, such as employee screening schemes. Such schemes are necessary but have inherent limitations, not least their limited coverage of staff recruited within countries of humanitarian response, who make up the majority of humanitarian aid workers. It will be important to critically assess the level of effort and investment in these schemes to ensure effectiveness and value for money.

The UK’s commitment to deliver a survivor-centred approach has not yet been realised. We found that FCDO staff and partners understood what a survivor-centred approach was in principle, but very few were able to describe how this was being delivered in the contexts in which they were working. In terms of providing support to victims and survivors, FCDO has made a large ad hoc financial contribution to the UN’s Trust Fund in Support of Victims of Sexual Exploitation and Abuse and has provided financial and political support to the Victims’ Rights Advocate and field officers. However, the department has not yet found a consistent approach to ensuring the needs of victims and survivors are met or harm is redressed.

Failures to prevent SEA in humanitarian contexts have been attributed to the culture within individual organisations and in the humanitarian sector overall. Profound power disparities and gender inequality contribute to a culture that normalises exploitation and abuse and discourages reporting. We saw evidence that FCDO is addressing culture change internally and externally, but the absence of baseline data and the immaturity of much of the programming make it impossible to gauge the depth or sustainability of this change.

FCDO’s stringent requirements around minimum standards and reporting are helping to encourage culture change in the humanitarian sector. Despite concerns voiced by some about creating a ‘tick box’ culture around safeguarding, these standards and requirements have raised the profile and seriousness of SEA for delivery partners, and reportedly also for their downstream partners. It is, however, important that FCDO ensures that partners do not become complacent in their approach. In addition, risks of negative side effects of stringent reporting mechanisms and sanctions need careful handling if the aims of transparency and accountability are to be achieved.

The UK has invested substantial political capital and financial and human resources on PSEA, resulting in policy and operational changes. This has contributed to increased awareness, more reporting mechanisms, and better monitoring of these mechanisms and of staff conduct. Nonetheless, it remains widely recognised that there is under-reporting of cases by members of affected populations, and there is no evidence base to show that the measures taken have reduced SEA in contexts of humanitarian crisis. We therefore award an amber-red score for effectiveness.

Recommendations

Recommendation 1:

FCDO should focus greater attention on humanitarian responses in country, supporting partners in implementing approaches to protection from sexual exploitation and abuse that are tailored to each context.

Recommendation 2:

FCDO should ensure that trusted mechanisms systematically capture the voices of affected populations, victims and survivors to inform policy and improve operations on sexual exploitation and abuse in humanitarian settings.

Recommendation 3:

FCDO should develop and implement a research agenda on protection against sexual exploitation and abuse that identifies and prioritises key evidence gaps, in particular on what is happening on the ground.

Recommendation 4:

FCDO should ensure that its support of efforts to prevent the re-hiring of perpetrators of sexual exploitation and abuse includes staff recruited in countries of humanitarian response, who make up the majority of humanitarian aid workers.

Recommendation 5:

FCDO should conduct a review of its approach to investigating allegations of sexual exploitation and abuse by humanitarian workers in order to address the points identified by this review.

Introduction

Humanitarian workers sexually exploiting and abusing those they have a duty to support and protect is a persistent problem in the sector. Against a backdrop of the global #MeToo and #AidToo movements, incidents of sexual exploitation and abuse (SEA) involving humanitarian workers continue to surface.

In the UK, SEA hit the headlines in 2018, when allegations were revealed of SEA perpetrated in Haiti by staff from a UK non-governmental organisation (NGO). The allegations were followed by an immediate upsurge in the reporting of safeguarding incidents to the Charity Commission for England and Wales, with 80 serious safeguarding incidents reported from 26 charities working in the aid sector. That year, the UK government launched a long-term effort to place the safeguarding of vulnerable populations against SEA by humanitarian workers on international and national agendas, with the aim of pushing and supporting strict standards, robust processes and the cultural change necessary to address the widespread problem.

This review examines the extent to which the UK government’s efforts have been effective in preventing and responding to SEA in humanitarian aid contexts. It considers how well the UK government has identified and addressed evidence gaps in best practice for protection from sexual exploitation and abuse (PSEA) and how well it has developed a coherent response to the issue. PSEA approaches are considered by this review to include the prevention and detection of, and response to, SEA.

In the UK, efforts to address SEA by humanitarian workers fall under the rubric of safeguarding, while international humanitarian agencies and other donors generally use the term PSEA. The UK’s concept of safeguarding in the domestic context is broader than PSEA, and is usually understood as protecting at- risk adults and children from physical (including sexual) and emotional abuse, exploitation and neglect. Since 2018, in engaging with the international aid sector, the UK has used the term ‘safeguarding’ to refer to sexual exploitation, abuse and harassment as understood in the humanitarian sector, although this has led to some definitional confusion. This ICAI review focuses specifically on safeguarding against SEA in the humanitarian sector, perpetrated by humanitarian workers against affected populations, and particularly against people receiving humanitarian assistance. The report therefore only focuses on the aspects of safeguarding that fall under the narrower definition of PSEA. An overview of the many different and overlapping definitions covering the topic under review in this report is set out in Table 1 below.

Scope of the review

The review considers PSEA programming, policy and influencing activities by the UK government between 2017 and 2021, the years straddling the October 2018 international safeguarding summit that was hosted by the UK (known as the ‘London summit’) and at which the UK, alongside other key actors, made significant commitments to sectoral reform. In July 2019, alongside 29 other donors, the UK adopted the recommendation on ending sexual exploitation, abuse and harassment (SEAH) in development cooperation and humanitarian assistance of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development’s Development Assistance Committee (OECD DAC). The UK government’s strategy on safeguarding against SEAH, published in 2020 and building on OECD DAC and London summit commitments, provides the backdrop to our review. The merger of the Department for International Development (DFID) and the Foreign and Commonwealth Office (FCO) in September 2020 into the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO), recent reductions in humanitarian aid funding, and the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on operations and humanitarian access also add important context to our findings.

Table 1: Definitions used in this review

| Definitions |

|---|

| Safeguarding: In its broadest sense, safeguarding refers to a set of issues including both the environment and people. It includes the protection of individuals from physical, psychological and emotional abuse, exploitation and neglect. |

| Sexual exploitation, abuse and harassment (SEAH): This has been the focus of the UK government’s strategy on safeguarding for the aid sector.5 It includes sexual exploitation, abuse and harassment both of crisis-affected populations and of aid workers. In this review, SEAH against aid workers is not in scope, apart from when locally hired aid workers are themselves aid recipients or belong to affected communities. |

| Protection from sexual exploitation and abuse (PSEA): We use the term PSEA to include the prevention and detection of, and response to, sexual exploitation and abuse of people affected by humanitarian emergencies, perpetrated by aid workers. |

| Sexual exploitation: Any actual or attempted abuse of a position of vulnerability, differential power or trust for sexual purposes, including, but not limited to, profiting monetarily, socially or politically from the sexual exploitation of another. |

| Sexual abuse: The actual or threatened physical intrusion of a sexual nature whether by force or under unequal or coercive conditions. |

| Sexual harassment: Unwelcome sexual advances (without touching). It includes requests for sexual favours or other verbal or physical behaviour of a sexual nature, which may create a hostile or offensive environment. |

A key focus of the review is how well PSEA approaches work in practice in humanitarian settings. To evidence this, we consulted people affected by humanitarian responses. We include in our definition of affected populations both people receiving humanitarian assistance and people in communities affected by humanitarian response, including host communities in areas of displacement, or people living in communities that have been transformed by the large-scale arrival of humanitarian actors. In keeping with a survivor-centred approach, recognising that some people identify with the term ‘victim’ while others prefer ‘survivor’, we refer to those directly affected by SEA as ‘victims and survivors’.

This review focuses on humanitarian settings, where power imbalances between providers and recipients of aid are particularly stark, and vulnerability to SEA among aid recipients and affected populations can be high. For the purposes of this review, the term ‘aid worker’ comprises anyone working in the management or delivery of humanitarian assistance. This includes staff recruited internationally, nationally and locally, as well as government staff working under the management of humanitarian organisations or incentivised volunteers and community workers from among the target or host population.

While recognising that SEAH of aid workers by other aid workers is also a serious issue, this was outside the scope of this review. The exception to this rule is locally hired aid workers who are themselves members of affected communities.

The review did not look at SEA perpetrated by international peacekeepers, as this was the focus of a separate ICAI review. Nor did it include aid programming by non-FCDO official development assistance (ODA) spending departments as their humanitarian aid expenditure is marginal.

This review builds on a number of related reviews and inquiries that have taken place, including three reports by the International Development Committee (IDC). The most recent of these was published in January 2021 and considered UK government progress on tackling the SEA of those intended to benefit from UK aid.

Failure to protect affected populations from SEA undermines the achievement of a wide range of sustainable development goals (SDGs) and the commitment to ‘leave no one behind’. The main SDGs, and the ways in which PSEA principally relates to them, are illustrated in Box 1.

Box 1: How this review relates to the Sustainable Development Goals

The Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), otherwise known as the Global Goals, are a universal call to action to end poverty, protect the planet and ensure that all people enjoy peace and prosperity.

This review of the UK’s response to sexual exploitation and abuse in the humanitarian sector relates to the following SDGs, with many others also being relevant:

Goal 1: No poverty – With 700 million people across the world living in poverty and struggling to fulfil basic needs like food, health, education, and access to safe water and sanitation, vulnerability to SEA is an increased risk

Goal 5: Gender equality – PSEA requires a fundamental shift towards a world with gender equality and away from discrimination and violence, as well as universal access to sexual and reproductive healthcare

Goal 8: Decent work and economic growth – Economic opportunity for women, men, young people and people

with disabilities improves their livelihoods and contributes to their safety

Goal 16: Peace, justice and strong institutions – Accountability and provision of access to justice through inclusive and responsive systems can prevent and support victims of SEA

Goal 17: Partnerships for the goals – Through inclusive multi-stakeholder partnerships and mobilisation of resources at the global, regional, national and local levels, governments, the private sector and civil society can work towards a shared vision for safer humanitarian aid

Table 2: Our review questions

| Review criteria and questions | Sub-questions |

|---|---|

| Relevance: How well has the UK government gone about building a relevant and credible portfolio of safeguarding programmes and influencing activities? | • How relevant and appropriate is the UK government’s approach to protection from sexual exploitation and abuse (PSEA)? • How relevant and appropriate is the UK’s approach to building the evidence base on the scale and nature of PSEA and on ‘what works’ in prevention and response? • How well does the UK government’s approach reflect the needs and priorities of affected communities in humanitarian contexts and of victims and survivors? |

| Coherence: How well does the UK work with other donors and multilateral partners to ensure a joined-up global approach to protection from sexual exploitation and abuse? | • Is the UK’s approach coherent and consistent with the efforts of other humanitarian funders and agencies, and does this reflect a shared approach across government? |

| Effectiveness: How effective is the UK’s approach to protection from sexual exploitation and abuse at programme, delivery partner and sector-wide levels? | • How effective is the UK government’s support to its implementing partners to strengthen systems, train staff and engage communities in preventing, detecting and responding to sexual exploitation and abuse (including investigating allegations, taking action against perpetrators and supporting witnesses, victims and survivors)? • How effective is the UK’s approach in responding to incidents and preventing perpetrators from reoffending? • To what extent have PSEA measures promoted by the UK led to changes in attitudes and behaviours in humanitarian operations? |

Methodology

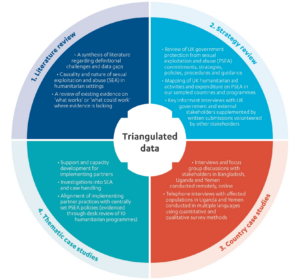

Our review followed the methodology and sampling approach described in our approach paper and summarised in Figure 1. It included the following elements:

Literature review: We reviewed the literature on protection from sexual exploitation and abuse (PSEA) covering definitional issues, data on incidents, prevalence, scale and trends, causal mechanisms, and evidence on ‘what works’ in PSEA in humanitarian settings. Our literature review informed our findings and is published as a separate report.

Strategy review: We reviewed the UK government’s strategy and approach to safeguarding with specific reference to humanitarian aid. This included assessment of strategy papers, policy and programme commitments, guidance, meeting records, stakeholder interviews and written submissions received via an online survey.

Country case studies: We looked in detail at the UK’s approach to PSEA in Bangladesh, Uganda and Yemen. Working remotely because of COVID-19 travel restrictions, we interviewed FCDO staff and programme partners in each country and working along different humanitarian aid delivery chains. We explored how each implementing partner was accountable to and supportive of others in their delivery chain, as well as affected people. We consulted people affected by humanitarian programme responses in the West Nile sub-region of Uganda and in Southern Yemen using quantitative and qualitative telephone surveys. The methodology, limitations, ethics, safeguarding and COVID-19 challenges are described in Annex 1. Given the dearth of primary data about PSEA and its impact on affected people, particularly from the perspective of those affected, this engagement provided an important source of evidence in answering the review questions and in testing the claims and assumptions of implementing partners about how they engage with affected communities.

Desk reviews to inform three thematic case studies:

- Support and capacity development for implementing partners: We reviewed management documents, evidence from interviews and website sources to assess FCDO’s ‘dual approach’ to capacity building: an external focus on building the capacity of smaller, local partners in partner countries, and an internal focus on strengthening the department’s own capability to promote behaviour change and embed safeguarding among partners. We looked at the Resource Support Hub, the Open University safeguarding course (Module 1), and support to FCDO Programme Managers, Senior Responsible Owners and the Safeguarding Champions Network to strengthen due diligence processes, build risk management capacity and better manage sexual exploitation and abuse (SEA) cases. We heard from a sample of FCDO’s implementing partners how these initiatives were helping them to develop their safeguarding capabilities and systems.

- Investigations case management: We conducted ten in-depth interviews with FCDO staff and external partners, reviewed some 140 documents and used case data analysis to assess how FCDO handles SEA cases perpetrated by humanitarian workers against affected populations. We looked in depth at FCDO’s oversight of how implementing partner organisations dealt with complaints, investigation and follow-up of such cases. We considered FCDO policies, processes and guidelines and good practices followed by other agencies. We sampled all 318 cases from Bangladesh, Uganda and Yemen reported to FCDO’s Safeguarding Investigations Team (SIT) during the four financial years 2017-18 to 2020-21. This represented around a quarter of SIT’s total caseload in this period. The 318 cases covered a range of complaints including workplace misconduct issues between staff and broader protection cases (such as corporal punishment and child labour perpetrated by non-aid workers, which are not relevant to the scope of this inquiry). Out of the 318, we reviewed the 40 case summaries that involved SEA towards people from affected populations, followed by an in-depth study of three cases from this subset.

- Alignment of implementing partner practices with FCDO-set PSEA policies: We conducted desk reviews of components of large humanitarian programmes under implementation in our case study countries. Our sample comprised programmes at ‘high risk’ for SEA, involving direct interaction with at-risk individuals and communities. The sample covered a diversity of funding mechanisms, including programme components funded directly, sub-contracted through the UN, international non-governmental organisations (INGOs) and through mechanisms such as pooled funds. The desk reviews were based on programme documentation including business cases, annual reports and evaluations, triangulated with telephone interviews.

Our research was conducted in line with strict safeguarding and ethical protocols, as set out in our approach paper.

Figure 1: Summary of methodology

The evidence used in the review was collected through the survey of 600 affected people, interviews and focus group discussions with 232 stakeholders, 53 written submissions and the review of over 1,000 documents. Limitations of the methodology are listed in Box 2.

Box 2: Limitations of the methodology

Getting robust data and evidence on SEA in humanitarian settings is challenging.

- SEA definitions are contested and interpreted differently by different actors, which can make comparison difficult.

- SEA is a highly sensitive issue and stakeholders may have been unwilling or unable to speak openly and candidly, which may have skewed our evidence. The sensitivity of the topic also required us to adopt a cautious approach with strict research ethics and protocols to ensure that the rights and anonymity of victims and survivors of SEA are protected, and the risk of re-traumatisation or retaliation avoided.

- There is limited data and peer-reviewed literature on the subject.

- PSEA requires action under every UK aid-funded humanitarian programme and is context-specific, making it difficult to generalise findings to humanitarian aid as a whole.

- There are methodological challenges associated with attributing results to the UK’s influencing work on PSEA, given the involvement of many other actors.

- Many of FCDO’s centrally managed safeguarding programmes are still at an early stage of implementation and are yet to generate outcome-level results.

- COVID-19 restrictions required us to engage with affected populations using telephone survey methods. This may have biased consultations away from more marginalised groups including poorer and more remote households and women who are less likely to have access to a mobile phone.

Background

The international humanitarian system performs a critical role in saving lives and reducing suffering in countries in conflict and crisis, but the humanitarian sector is failing in its duty to do no harm. While its scale and scope is unknown, sexual exploitation and abuse (SEA) of affected populations perpetrated by aid workers is a serious and persistent problem. Despite reforms dating back as far as the 2002 ‘sex-for- aid’ scandal in West Africa, SEA is believed to be widespread in the sector. High-profile cases continued to be reported throughout the period of this ICAI review, beginning in 2018 with a scandal triggered by historical cases in Haiti and ending in 2021 with an independent investigation13 evidencing serious cases of SEA by humanitarian workers in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) (see Figure 2).

Figure 2: Safeguarding timeline of key events, 2002 to 2021

In addition to the significant suffering that SEA causes victims and survivors, its widespread nature also undermines the credibility of humanitarian action by the UN, donors, state and non-state actors, and the UK’s broader international commitments. The latter include Sustainable Development Goal 5 pertaining to gender equality and empowerment for women and girls, legal requirements under the International Development Gender Equality Act (2014) to meaningfully consider the impact of all development assistance from a ‘do no harm’ and gender equality perspective, and Strategic Outcome 4 of the UK National Action Plan on Women, Peace and Security, which recognises that women and girls face heightened risk of exploitation and abuse in humanitarian contexts and require more tailored attention from humanitarian interventions.

Humanitarian organisations have a responsibility and commitment to protect the people they serve from harm, including harm caused by their own personnel or programmes. This is tied to a commitment to accountability to affected populations (AAP), by using power responsibly, taking account of, giving account to, and being held to account by the people they seek to assist. Sectoral standards, articulated by the Inter-Agency Standing Committee (IASC), hosted by the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) and under the Core Humanitarian Standard on Quality and Accountability (CHS), require organisations to work in partnership with affected populations, soliciting their views, listening to them, and taking meaningful action. AAP includes an obligation to feed back to affected communities what action has been taken in response to their expressed needs and concerns. These principles have been adopted by FCDO and are integrated into its safeguarding work. They are also tied to other areas in which the UK has played a strong role in developing humanitarian policy, in particular by empowering national responders as part of work on localising humanitarian response.

Key issues and challenges

Causality and nature of sexual exploitation and abuse in aid settings

SEA is a manifestation of the abuse of power. The literature consistently emphasises the gendered nature of SEA, which disproportionately affects women and girls, but boys and men can also fall victim. People who identify as lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender or queer (LGBTIQ+) may be especially vulnerable to SEA, particularly in contexts where homosexuality is illegal or deemed socially unacceptable and there are few legal or community-based protections. Other individual risk factors include age, disability, socio- economic status, migrant status, race and ethnicity. Isolation also increases risk, especially for internally displaced people (IDPs), children and female-headed households.

There are a range of structural factors driving SEA. Some drivers present immediate opportunities for perpetrators, such as the lack of law and order that often characterise humanitarian settings. Other drivers reinforce normalisation of SEA, such as individual and organisational attitudes and norms that enable or condone SEA, including structural sexism and racism. Most evidence on the causal drivers of SEA is context-specific, making it challenging to identify general patterns. Instead, risks must be understood and addressed differently in different contexts. Context-sensitive risk mitigation approaches are needed to prevent and respond to incidents.

Available data and evidence of ‘what works’ in preventing and responding to sexual exploitation and abuse

No systematic data on the prevalence of SEA across the humanitarian sector exists, beyond context- specific incidents (for instance, in relation to specific humanitarian responses). The quality of reporting across governments, multilateral agencies and international and local NGOs also varies greatly, making it challenging to identify any macro-level trends or patterns. Evidence of ‘what works’ in preventing and responding to SEA in humanitarian settings is also limited. There are no systematic evaluations, portfolio reviews or reliable outcome data on PSEA efforts across the humanitarian sector.

PSEA approaches in the humanitarian sector generally fall into two main areas:

- Prevention, including proactive communication with affected communities about their rights, establishment of an accountable ‘speak up’ culture, effective risk management, and the development and better application of PSEA standards and policies in recruitment, vetting and human resource management, including training and disciplinary procedures.

- Response, including the establishment of safe, effective and responsive complaints mechanisms, fair and transparent investigations, and a victim and survivor-centred response, including consideration of medical, legal and psychosocial needs.

To achieve accountability, organisations need to integrate the experiences of victims and survivors in the design and delivery of PSEA efforts, ensuring their consent and protection of confidentiality throughout.

The nature of humanitarian contexts

The urgency and fast-changing nature of humanitarian crises, combined with a high influx of new staff and quick staff turnaround associated with many emergency contexts, often means that safeguarding is not prioritised at the onset of new crises. During the Ebola crisis in the DRC between 2018 and 2020, the surge in new responders, together with a high demand for and unequal access to essential goods, increased the risk of SEA. Similar risks are present during the current COVID-19 pandemic.

In order to understand the challenges posed by different contexts, the review looked in detail at humanitarian crises in three countries: Bangladesh, Yemen and Uganda. Background on the three countries is provided in Boxes 3, 4 and 5. The three crises differ in their nature and scale, the extent of the national response, and the access afforded to humanitarian responders. The country case studies serve to illustrate the importance of context-specific responses to humanitarian crises and to PSEA.

Box 3: Bangladesh

Bangladesh is one of the most densely populated countries in the world and highly vulnerable to natural disaster. More than 80% of the population is exposed to risks of floods, earthquakes and drought, and more than 70% to cyclones. Bangladesh hosts one of the world’s largest refugee populations, around 950,000 Rohingya people who have fled violence and persecution in Myanmar. Virtually all Rohingya refugees are settled in 34 camps in the Cox’s Bazar region.

The Office of Refugee Relief and Repatriation within Bangladesh’s Ministry of Disaster Management oversees and coordinates the humanitarian operations in Cox’s Bazar. Humanitarian agencies and international and national NGOs have deployed a large number of humanitarian workers to the area. In 2021, some 134 agencies, NGOs and government bodies worked together under the 2021 Joint Response Plan to support 1.4 million refugees and affected host community members.

Bangladesh is not party to the UN Refugee Convention. The government does not confer formal refugee status on Rohingya refugees, with the rights and entitlements this entails. Government policies are directed at ensuring settlement is temporary, with restrictions on livelihoods opportunity, mobility and formal education for children in the camps.

The camps are difficult environments, with the population, highly traumatised by atrocities suffered in Myanmar, squeezed into densely populated camps with very basic services. Protection is a huge challenge, and camps are afflicted by violence, trafficking, and organised crime and criminal gangs. Protection challenges are exacerbated by curfews that restrict access to the camps in the evenings by humanitarian workers. The broader restrictions introduced to contain the spread of COVID-19 resulted in many services in the camps being stopped, including protection services. Victims and survivors of SEA are made more vulnerable in patriarchal contexts where women have less power and fewer rights, and risks associated with stigma have a stifling effect on reporting.

Box 4: Uganda

With around 1.5 million refugees, Uganda is host to one of the largest refugee populations in the world and the largest in Africa. Roughly two-thirds of refugees are South Sudanese (65.6%), just under one-third are Congolese (30.8%) and a small proportion (3.5%) Burundian.

Apart from those residing in the capital, Kampala, the vast majority of refugees are hosted in 13 settlements established on land donated by local communities in collaboration with the Office of the Prime Minister. This ‘Ugandan Model’ is widely praised and considered among the most progressive refugee policies in the world. It allows relatively open borders and supports the integration and self-reliance of refugee and host communities. It provides land allocations to refugees as well as the right to work, study, access social services and enter into contracts and allows Ugandan nationals to access some of the services provided to refugees by the international community. While this generosity is commendable, it remains the case that many self-settled refugees live in deep poverty and are highly vulnerable to exploitation and abuse.

There is a reluctance to report SEA, as evidenced in recent studies and in ICAI’s own survey. This is a likely contributory factor to the low levels of SEA cases reported in the Inter-Agency Feedback, Referral and Resolution Mechanism (FRRM). The FRRM dashboard shows that out of a total 84,215 calls referred by the central helpline to agencies since 2018, just 27 concerned SEA.

In March 2017, the Ugandan government launched the Comprehensive Refugee Response Framework, with the United Nations Refugee Agency (UNHCR) supporting its implementation. However, there is a history of corruption and fraud in the refugee response. In February 2018, senior officials in the Office of the Prime Minister were suspended pending investigations into alleged collusion with staff at UNHCR and the World Food Programme to exaggerate refugee figures. The UK, along with Germany and Japan, responded by suspending in-country funding to UNHCR – although the other governments resumed their assistance not long afterwards.

General underfunding and continued growth of the refugee population have resulted in, for example, a 30% cut in food rations for refugees in April 2020, and a further 10% cut in 2021. While efforts are being made to reduce the impact of cuts on the most vulnerable, this, combined with the COVID-19 pandemic, will worsen the well-being of refugees in Uganda, including their protection and livelihoods.

Box 5: Yemen

Yemen was already one of the poorest countries in the Middle East before civil war broke out in March 2015, driving the country into severe crisis. At the end of 2020, around 21 million Yemenis (two-thirds of the population) needed humanitarian assistance. By 2021 this had risen to some 24.8 million people (around 80% of the population), including 5 million on the brink of famine. The UN describes the situation in Yemen as the world’s worst humanitarian crisis.

With more than four million Yemenis displaced since the beginning of the crisis, Yemen now has the fourth-largest number of IDPs in the world. Yemen also hosts more than 135,000 refugees and asylum seekers from Somalia and Ethiopia. Around two-thirds of the internally displaced in Yemen live in dangerous locations, characterised by widespread food insecurity and lack of basic services.32 The humanitarian situation was exacerbated in 2020 by escalating conflict, the COVID-19 pandemic, and a range of other crises, including economic collapse, outbreaks of infectious disease, flooding, locusts, and a fuel crisis across northern governorates. These issues had an impact on humanitarian assistance, which was already highly restricted due to access challenges and insecurity that hindered a response delivered in accordance with humanitarian principles.

Among both IDPs and refugees, vulnerability to SEA is heightened for women, children, people with disabilities, older people and historically marginalised groups such as the Muhamasheen, a minority community who are subjected to caste-based discrimination. In 2019 Amnesty International reported that Yemen was “one of the worst places in the world to be a woman”.34 Women and girls are disadvantaged by economic inequality, a discriminatory legal system, child marriage, divorce shame, domestic violence, and forced niqab and honour killings. Women and girls have also been disproportionately affected by the ongoing conflict.

The Inter-Agency Standing Committee (IASC), hosted by the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA), leads a coordinated approach to PSEA measures in Yemen with PSEA focal points within settlements. Despite efforts to strengthen the protection environment, significant gaps in protection capacity remain across Yemen. The IASC estimates that in 2019 and 2020, at most only 25% of the affected population could access safe complaints channels and SEA assistance. The issue of unrepresentative and unreliable data compounds any efforts to have a clear picture of the relevance and effectiveness of PSEA measures in Yemen.

The challenge of interagency working

Effective responses to humanitarian crises require a multiplicity of actors, including government, multilateral agencies, bilateral donors, civil society organisations (CSOs) and private sector service providers, to work together along a humanitarian delivery chain to supply goods, services and information to affected populations.

This can involve the very rapid deployment of thousands of aid workers into dangerous situations, where law and order, service and community infrastructure may have broken down. In these circumstances, interagency working becomes paramount, with the coordination of responses and sharing of information between government and agencies essential. It is also a prerequisite for establishing coherent policies that can drive up standards and deliver culture change across the international aid sector.

Risk of SEA set to grow as humanitarian crises become more frequent

Protracted and acute humanitarian emergencies, including conflict, natural disasters and widespread and often systematic violations of human rights, cause devastation to millions globally. Climate change, combined with the fallout of the COVID-19 pandemic, means that humanitarian emergencies are expected to rise in coming years. The 2021 Global Humanitarian Overview states that a record 235 million people will require humanitarian assistance in the next year, an almost 40% increase on 2020, attributed primarily to the impacts of COVID-19.

It is estimated that around one in four people in need of humanitarian assistance are women and girls of reproductive age, who, along with other marginalised groups, are particularly at risk of SEA. This risk is increased by the socio-economic impacts of the pandemic, including loss of income, school closures and restriction of access to health and social services.35 The risk is particularly high in areas where humanitarian organisations and donors are unable to be consistently present where assistance is being provided. Impunity flourishes in such closed environments where power dynamics are exaggerated and monitoring is more difficult.

…two years before, it was better but ever since corona started in these two years it has worsened. The young girls no longer go to school and a lot of peer influence has got into the youth that has increased the basis of teenage pregnancies and rape cases.

Member of affected community, Northern Uganda

The UK government’s safeguarding strategy and programme portfolio

The UK government’s 2020 strategy for safeguarding in the aid sector36 pledges that the UK will work at three levels to tackle SEA: across the aid sector, within UK government organisations, and through partners and programmes. It will support interventions that promote accelerated deterrence and prevention, victim and survivor-centred reporting and response, culture change and sector-wide capability and mutual accountability. This ICAI review only covers FCDO programming, which is responsible for the vast majority of UK humanitarian aid spending.

For this review, we looked at the programmes managed directly by FDCO’s Safeguarding Unit in so far as they related to safeguarding in the humanitarian sector. We also considered FCDO’s portfolio of humanitarian programmes delivered both bilaterally and through core contributions to multilateral agencies.

In 2019, the former Department for International Development (DFID) had planned to spend at least £40 million on centrally managed programmes and activities earmarked for safeguarding over the period 2019-24. The four main centrally managed FCDO safeguarding programmes under implementation in 2021 as part of this commitment are detailed in Table 3.

Table 3: FCDO centrally managed safeguarding programme commitments

| Safeguarding Innovation and Engagement Programme Fund (2018-24, £4.4 million) | Provides responsive expert advice and technical assistance on safeguarding to DFID/FCDO, pilots and implements approaches to raise safeguarding standards for DFID/FCDO, and engages and convenes partners to drive up standards and deliver culture change across the international aid sector. |

|---|---|

| Project Soteria (2019-25, £10 million) | Supports aid organisations to stop perpetrators of SEAH from working in the aid sector via more and better criminal record checks on staff. Includes collaboration with Interpol and ACRO, the UK criminal records body. |

| Safeguarding Resource and Support Hub (2019-24, £10 million) | Provides support to aid organisations to strengthen their safeguarding policy and practice against SEAH. Primarily intended to support smaller, local NGOs in developing countries and those operating in high-risk environments which are least able to pay for this support themselves. The Hub is delivered via an open-access, online platform and regional hubs initially in Ethiopia, Nigeria and South Sudan. |

| Supporting Survivors and Victims of Sexual Exploitation and Abuse and Sexual Harassment (2020-25, £5 million) | Support is offered through four components: promoting and strengthening reporting mechanisms, improving the aid sector’s capacity to conduct high- quality investigations, improving delivery of support to survivors in country, and promoting the range and quality of services available to survivors and victims. |

In 2019, the UK’s ODA spending on humanitarian programmes was £2,205 million, comprising £1,536 million bilateral humanitarian aid and £669 million imputed UK share of multilateral net humanitarian aid. Unlike in previous years, the official statistics published in September 2021 do not include the imputed UK share of multilateral net humanitarian aid in 2020. OCHA’s Financial Tracking Service listed the UK as the fourth-highest bilateral spender of humanitarian assistance behind the US, Germany and the European Commission. Following the UK government’s reduction in the ODA spending target from 0.7% to 0.5% of gross national income, it is expected that there will be a reduction in humanitarian aid spending in 2021 compared to 2020. Because of the way expenditure is recorded, it is not possible to quantify how much of total spending on humanitarian programming has been allocated to safeguarding initiatives.

FCDO’s Conflict, Humanitarian and Security Department (CHASE) responds to humanitarian needs arising from conflict and natural disasters. The largest portion of CHASE programming is for core funding to key humanitarian partners. This funding is unearmarked and provides agencies with the flexibility to disburse funds rapidly, to respond immediately when a crisis hits, to perform anticipatory action so crises are less severe, to respond to neglected crises, and to invest in central functions (including safeguarding mechanisms) to enhance efficiency and controls across their global operations. The flexible nature of this core funding means that FCDO cannot attribute specific amounts to any single PSEA initiative. However, the programme includes PSEA performance indicators against which agencies report on PSEA- related activities and through which FCDO is able to hold agencies to account. FCDO carries out Central Assurance Assessments on each agency which include a specific safeguarding focus, and FCDO staff are active participants in regular governance and other meetings through which agency PSEA-related activities are scrutinised.

Findings

Relevance: How well has the UK government gone about building a relevant and credible portfolio of safeguarding programmes and influencing activities?

The UK has used its resources, influence and convening power to galvanise action on sexual exploitation and abuse in the humanitarian sector, acting as an important catalyst for change and complementing other initiatives at both international and local levels

The international safeguarding summit hosted by the UK government in London in 2018 helped focus attention in the humanitarian sector on prevention of sexual exploitation and abuse (PSEA). The UK used its convening power and influence as a prominent donor to focus a spotlight on an issue that was not receiving enough attention and to bring a diverse array of actors to the table to make specific commitments to improving prevention and response. We heard the London summit described as “a shot of adrenaline” and “a galvanising moment”.

The London summit also played a catalytic role at local level. In Bangladesh, we heard that the heightened attention to safeguarding resulting from the summit added impetus to efforts already under way to address sexual exploitation and abuse (SEA) of Rohingya refugees in camps in Cox’s Bazar. In Uganda, stakeholders noted that it dovetailed with wider work on corruption and abuse of power issues in the refugee response.

The UK has developed a wide-ranging strategy comprising four ‘strategic shifts’ that reflect a broad consensus on priority actions and interventions

The UK’s strategy on Safeguarding Against Sexual Exploitation and Abuse and Sexual Harassment within the Aid Sector aims to provide a comprehensive approach to safeguarding. This includes measures aimed at preventing and responding to incidents, listening to people with practical experience, particularly victims and survivors, and learning from every case. There is also a commitment to building capacity and capability at all levels of the sector. This strategy generally reflects the priorities of the humanitarian sector and shows a good balance of learning from and adopting existing standards and approaches and innovating or investing in new initiatives.

The strategy identifies four long-term ‘strategic shifts’:

- To ensure support for survivors, victims and whistleblowers, enhance accountability and transparency, strengthen reporting, and tackle impunity.

- To incentivise cultural change through strong leadership, organisational accountability and better human resource processes.

- To adopt global standards and ensure that they are met or exceeded.

- To strengthen organisational capacity and capability across the international aid sector to meet these standards.

The strategy acknowledges the long-term nature of the challenge of ensuring safeguarding against SEA in the aid sector and commits to taking both short- and long-term measures to address it. This long-term commitment is realised through inclusion of minimum safeguarding standards in FCDO systems such as enhanced due diligence, business cases and funding agreements. The strategy aims to drive higher standards and meaningful, long-term leadership and culture change on safeguarding against sexual exploitation, abuse and harassment (SEAH), both within the UK government and the whole aid sector. Delivery of the strategy is led on a day-to-day basis by the Safeguarding Unit which was established in February 2018, with quarterly oversight by a Safeguarding Delivery Board and annual discussion by the FCDO Management Board. A Safeguarding Champions Network (established in January 2020) helps to embed safeguarding norms and practices in order to effect long-term behavioural change within FCDO.

The UK safeguarding strategy was developed based on wide consultations but lacks systematic ongoing engagement with crisis-affected people, especially victims and survivors of SEA

In preparation for the 2018 London summit, the UK engaged a diversity of actors, and their input helped inform the priorities of both the event and the UK safeguarding strategy. Key actors from the humanitarian sector included representatives from the UN, NGOs, international financial institutions, private sector suppliers, research funders, donors, CDC Group (rebranded on 4 April 2022 as British International Investment), the Global Fund and GAVI, the Vaccine Alliance. Following the London summit, an Independent Reference Group was formed, made up of individuals with technical and practitioner expertise in SEA and sexual harassment from multiple disciplines. We found that the consultation was meaningful, as evidenced by adaptations and course corrections, in developing the strategy. However, some stakeholders involved in ongoing consultation mechanisms told us it had become less clear in the post-London summit period how their input was being used to shape policy.

While the UK’s initial activities drew substantially on domestic safeguarding policies and practice, it soon aligned its approach with the established terminology and processes in the international humanitarian sector around PSEA, endorsing and adopting sectoral standards such as the Inter-Agency Standing Committee (IASC) Minimum Operating Standards on PSEA and the Core Humanitarian Standard. These are described in Box 6 below.

Efforts have been made to include the voices of victims, survivors and whistleblowers, notably through a ‘listening exercise’ held prior to the London summit, a survivor engagement meeting hosted in March 2019 to “get views on how best to engage further with victims and survivors as we develop policy and initiatives”, and engagement with individual whistleblowers. As part of its due diligence processes, FCDO also requires partners to include victims and survivors in the design, implementation and monitoring of programmes and systems targeting SEA, and monitors whether this is taking place.

At country level, we heard that FCDO is engaging with mechanisms like the Refugee Engagement Forum in Uganda. However, those most likely to be affected by SEA are also those least likely to have access to or make use of these mechanisms, since they are often vulnerable, disempowered and perhaps afraid to express concerns or make their voices heard. Moreover, cultural sensitivities can preclude these kinds of issues being discussed in an open forum. In Yemen, for example, we heard that partners struggle to broach the subject of gender-based violence due to cultural sensitivities and conflict dynamics.

The tools and frameworks partners are using are not localised and not aligned with the local context. Before the war, we had some flexibility to do gender work. Today that space has closed… talking about gender, to support women, there are ways it can be done to bypass some of the political issues. If you start talking about enhancing women’s capacity at the household level, they will accept this talk. They will not accept talk of women’s empowerment in isolation. Thinking outside the box about how you do this is not there.

Gender expert, Yemen

FCDO makes efforts to be present and to understand the conditions in which partners work and in which people affected by crisis live. In Bangladesh, for example, we heard from partners that an FCDO staff member regularly visited the camps to observe activities and monitor how partners were delivering on their commitment to provide opportunities for affected people to give feedback and make complaints. Such engagement from FCDO as a donor is valuable and complements the continuous presence provided by implementing partners. Being less frequently present, donors are less able to reach at-risk community members and gain their trust. However, in some contexts, their engagement with at-risk community members could garner unwanted attention, particularly in contexts where women have less power and fewer rights and where risks for victims and survivors of SEA are consequently very high.

Like other donors, FCDO requires partners to consult with affected people and to address their feedback and complaints. Information from these consultations is sometimes shared with the donor, but this is not systematic. FCDO’s programme and partner management systems and stakeholder consultation include opportunities to learn, but FCDO does not have a system to ensure that this experiential learning on SEA is used to improve not only partner programming but also the department’s own strategy and approach.

Box 6: International standards on PSEA

FCDO has aligned its expectations of partners with the IASC Minimum Operating Standards on PSEA and the Core Humanitarian Standard on Quality and Accountability (CHS).

The four pillars of the IASC Minimum Operating Standards on PSEA relate to:

- Management and coordination: ensuring PSEA policies and standards of conduct are developed and effectively implemented, establishing cooperative arrangements whereby partners can signal their written agreement to abide by the standards, and having a dedicated department / focal point committed to PSEA.

- Engagement with and support of local communities through establishing communication from headquarters to the field on how to (a) provide information to affected populations on their right to be protected from SEA, and (b) establish effective community-based complaints mechanisms.

- Prevention: (a) mechanisms to ensure staff awareness on SEA, including through induction and refresher training, and (b) effective recruitment and performance management, including requiring new hires

to sign the code of conduct and committing to improve systems of reference checking and vetting for former misconduct. - Response: ensuring internal complaints and investigation procedures are in place, with investigations undertaken by experienced and qualified professionals.

The Core Humanitarian Standard on Quality and Accountability sets out nine commitments and quality criteria that can be used to improve the quality and effectiveness of humanitarian assistance delivery, and improve accountability to communities and people affected by crisis.

How FCDO has adopted these standards

FCDO has incorporated these standards in its staff code of conduct and in its policies and procedures for suppliers. FCDO’s enhanced due diligence procedures require compliance from partners on standards in six areas: safeguarding, whistleblowing, human resources, risk management, code of conduct, and governance and accountability. Standards are also embedded in the supply partner code of conduct,43 supplier contract documents and memoranda of understanding with different multilateral agencies. FCDO notes in its enhanced due diligence guidance that it applies proportionality to its assessment of partners’ efforts. This acknowledges the need for continuous improvements, even when a basic standard is met, and that smaller partners may struggle to fully implement measures in all areas.

The UK has adopted a wide-ranging strategy of seeking change both at the international and delivery level, but a disproportionate emphasis on systems may be resulting in slower change for affected people

Updating requirements to ensure partners meet minimum standards for PSEA, in line with the CHS and IASC Minimum Operating Standards (see Box 6), has been an important part of the FCDO’s approach for affecting change to the delivery of humanitarian assistance in-country – referred to as the ‘delivery level’. Several stakeholders expressed concern that the emphasis on compliance with standards risked creating a ‘tick box’ approach, with partners more concerned about showing donors that systems are in place than ensuring they are effective. However, we saw no evidence that partners are failing to take this seriously. On the contrary, there was evidence that attention to SEA had increased at all levels of the delivery chain, including both NGO/CSO and private sector service providers, over the review period.

FCDO has made substantial investments to improve PSEA in the wider humanitarian system – the ‘international’ or ‘systemic’ level – including through training and guidance and establishing more effective systems for information sharing. This is a highly relevant approach because it uses the UK’s influence and convening power to create systemic change that will ultimately have the broadest possible impact. However, it takes time for changes at the international level to be fully implemented in country, including ensuring adequate training and support to staff working in the most remote locations. Moreover, some projects have taken time to gain traction, as illustrated by the slow rollout of initiatives to block perpetrators from accessing employment in the humanitarian sector or efforts to promote a more accountable humanitarian culture. FCDO should look at what more immediate efforts can be undertaken at the delivery level to prevent abuse in the short term while systemic approaches are bedding in.

An additional risk of focusing on system-wide change is that it reinforces what is already a top-down culture in the humanitarian sector, in which funding, learning and systems are pushed from the centre to the periphery. Coupled with the importance of compliance with minimum standards, this puts a heavy emphasis on accountability towards donors, which leaves less time and space for accountability to people from affected communities, particularly for smaller organisations with less capacity. This may in turn hinder the inclusion of voices from trusted local rights organisations, women’s groups and other community actors who are more connected with the needs of affected people and victims and survivors. This tilting of the balance of FCDO’s approach not only risks reducing the centrality of affected people, victims and survivors in humanitarian response, but also works against other UK commitments, notably towards the localisation of humanitarian response.

FCDO has invested substantially in the creation of a Safeguarding Investigations Team (SIT), which sits in the Internal Audit and Investigations Directorate. Formed in January 2019, SIT has a mandate to ensure an appropriate survivor-centred response to safeguarding incidents involving members of staff and FCDO funding. Under this system, all concerns are routed through a central reporting system and are triaged on the basis of risk. Where deemed appropriate a new case is opened, with each case allocated a priority rating based on the level of risk to FCDO. The case is allocated to a dedicated case manager in SIT, and this case manager then works with partners and programme teams to progress the case. In this way, SIT directly investigates priority cases and provides oversight of partners’ investigations.