The UK’s approach to safeguarding in the humanitarian sector

List of acronyms

| Acronyms | |

|---|---|

| ACRO | ACRO Criminal Records Office |

| ACF | Action Contre La Faim (Action Against Hunger) |

| ADRA | Adventist Development and Relief Agency |

| BRAC | Bangladesh Rural Advancement Committee |

| DFID | Department for International Development (merged with the Foreign and Commonwealth Office in September 2020) |

| FAO | Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations |

| FCDO | Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office |

| FCO | Foreign and Commonwealth Office (merged with the Department for International Development in September 2020) |

| ICRC | International Committee of the Red Cross |

| IFRC | International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies |

| IDC | International Development Committee |

| IOM | International Organisation for Migration |

| NGOs | Non-governmental organisations |

| OCHA | United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs |

| PSEA | Protection from sexual exploitation and abuse |

| SEA | Sexual exploitation and abuse |

| SEAH | Sexual exploitation, abuse and harassment |

| SFD | Social Fund for Development |

| UNDP | United Nations Development Programme |

| UNFPA | United Nations Population Fund |

| UNHCR | United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees |

| UNHAS | United Nations Humanitarian Air Service |

| UNICEF | United Nations Children’s Emergency Fund |

| UNOPS | United Nations Office for Project Services |

| VAWG | Violence against women and girls |

| WFP | World Food Programme |

| WHO | World Health Organisation |

Purpose, scope and rationale

Safeguarding at-risk adults and children from physical and emotional abuse, exploitation and neglect across a multiplicity of industries and social sectors has become a matter of acute concern to policymakers and the public. In recent years, within the aid sector, the UK government has focused its attention on safeguarding against sexual exploitation and abuse and sexual harassment.

This review will focus explicitly on the humanitarian aid sector and will examine the extent to which the UK government’s safeguarding efforts have been effective in preventing and responding to sexual exploitation and abuse (SEA) of affected populations, perpetrated by aid workers operating in humanitarian aid contexts. The review will consider how well the UK government has identified and addressed evidence gaps about best practice for protection from sexual exploitation and abuse (PSEA) and how well it has developed a coherent response to the issue. PSEA approaches are considered by this review to include the prevention, detection and response to SEA. A key focus of this review will be how well PSEA approaches work in practice. To evidence this, we will draw on the voices and experiences of people affected by humanitarian crises as well as recipients of humanitarian assistance. We will not explicitly seek to interview victims or survivors of SEA (see Section 7: Research ethics and safeguarding).

This review will build on a number of related reviews and inquiries that have taken place, including the work of the International Development Committee (IDC). It will also consider the impact on safeguarding efforts of the merger of the Department for International Development (DFID) and Foreign and Commonwealth Office (FCO) in September 2020 into the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO), recent cuts in humanitarian aid funding and the COVID-19 pandemic. Its focus before the FCDO merger will be on PSEA approaches pursued by the former DFID.

The review will cover PSEA programming, policy and influencing activities by the UK government between 2017 and 2021, the years straddling the October 2018 international safeguarding summit that was hosted by the UK (known as the ‘London summit’) and at which the UK, alongside other key actors, made significant commitments to sectoral reform. Our scope will include the following:

- the UK’s strategy on safeguarding against SEA within the aid sector

- the UK’s central safeguarding initiatives and influencing activities to promote safeguarding reforms

- DFID/FCDO humanitarian spend from financial year 2017-18 to date

- DFID/FCDO PSEA research spend from financial year 2017-18 to date

- humanitarian implementing partners along programme supply chains (including multilateral, bilateral, private sector and non-governmental organisations).

In humanitarian settings, power imbalances between providers and recipients of aid can be stark, and vulnerability to SEA among aid recipients and affected populations high. While recognising that sexual exploitation, abuse and harassment (SEAH) of aid workers in their work environment is also a serious issue, this will not be within the scope of this review. The review will not look at SEA perpetrated by international peacekeepers, as this was the focus of a separate ICAI review. Finally, the review will not include aid programming by non-FCDO departments as their humanitarian spend is marginal.

For the purpose of this review, our understandings of safeguarding, SEAH, PSEA, sexual exploitation, sexual abuse, and sexual harassment, are set out in Table 1. These align with definitions used by the UK government and reflect UN definitions.

| Definitions |

|---|

| Safeguarding: The UK government’s strategy on safeguarding within the international aid sector6 considers safeguarding to broadly mean avoiding harm to people or the environment. Its strategy includes in its scope sexual exploitation, sexual abuse and sexual harassment. In this review, we understand safeguarding to refer to a broad set of protection issues including protection of individuals from physical abuse, psychological and emotional abuse, exploitation and neglect. We have adopted a narrower set of issues (concerning the protection from sexual exploitation and abuse, below) to be in scope. |

| Sexual exploitation, abuse and harassment (SEAH): This term has been adopted by the UK government to describe the scope of its safeguarding strategy for the UK aid sector and includes sexual exploitation, abuse and harassment both of affected populations and of other aid workers. |

| Protection from sexual exploitation and abuse (PSEA): We use the term PSEA in this review to include the prevention and detection of, and response to sexual exploitation and abuse of people impacted by the humanitarian aid sector. PSEA is narrower in scope than safeguarding. |

| Sexual exploitation: Any actual or attempted abuse of a position of vulnerability, differential power or trust for sexual purposes, including, but not limited to, profiting monetarily, socially or politically from the sexual exploitation of another. |

| Sexual abuse: The actual or threatened physical intrusion of a sexual nature whether by force or under unequal or coercive conditions. |

| Sexual harassment: Unwelcome sexual advances (without touching). It includes requests for sexual favours, or other verbal or physical behaviour of a sexual nature, which may create a hostile or offensive environment. |

ICAI is committed to incorporating the voices of people expected to benefit from UK aid into its reviews and has done so in previous reviews through citizen engagement in countries impacted by UK aid. People affected by humanitarian crises, such as refugees or stateless people, may not be citizens of the country in which they reside. To acknowledge this, we refer in this review to ‘affected people’ rather than ‘citizens’. We include in our definition of affected populations both people receiving humanitarian assistance and people in communities affected by the humanitarian response, including host communities in areas of displacement, or people living in communities that have been transformed by the large-scale arrival of humanitarian actors. We refer to those directly affected by SEA as victims/survivors.

For the purposes of this review, the term ‘aid worker’ comprises anyone working in the management or delivery of humanitarian assistance. This includes international, national and local members of staff, as well as government staff working under the management of humanitarian organisations or incentivised volunteers and community workers from among the target or host population.

Background

Exploitation, abuse and harassment cause widespread suffering and are contrary to the spirit and purpose of humanitarian response. While there is currently no comprehensive data on the prevalence of exploitation and abuse across the sector, based on existing evidence this is considered to be a consistent problem that urgently needs to be tackled. SEA perpetrated by humanitarian aid workers is not a new issue, but it received renewed attention in 2018 following widespread coverage of allegations of SEA perpetrated by humanitarian aid workers during the 2010 Haiti earthquake response.

In March 2018, the UK government hosted a safeguarding summit to drive collective action to prevent and respond to SEA in the UK aid sector. The government subsequently hosted an international safeguarding summit in October 2018 (known as the ‘London summit’) at which bilateral donor organisations, nongovernmental organisations (NGOs), multilateral and private sector organisations formulated (and many signed up to) a set of commitments on SEAH designed to bring about four long-term strategic shifts:

- ensuring support for survivors, victims and whistleblowers, enhancing accountability and transparency, strengthening reporting and tackling impunity

- incentivising cultural change through strong leadership, organisational accountability and better human resource processes

- agreeing minimum standards and ensuring they are met, including by partners

- strengthening organisational capacity and capability across the international aid sector, including building the capability of implementing partners to meet the minimum standards.

In 2019, the former secretary of state for international development, Rory Stewart, told the IDC that DFID planned to spend at least £40 million in funding centrally managed programmes and activities earmarked specifically for safeguarding over the period 2019-24, the majority of which is detailed in Table 2.

Building on the commitments made by donors at the London summit, in July 2019, alongside 29 other donors, the UK adopted the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development’s Development Assistance Committee (OECD DAC) recommendation on ending SEAH in development cooperation and humanitarian assistance.

In 2020, the UK published its Safeguarding Against Sexual Exploitation and Abuse and Sexual Harassment within the Aid Sector strategy. The strategy pledges that the UK will work at three levels (across the aid sector, within UK government organisations and through partners and programmes) to support interventions that promote accelerated deterrence and prevention, victim/survivor-centred reporting and response, incentivised culture change and sector-wide capability and mutual accountability.

| Centrally managed safeguarding programming |

|---|

| Safeguarding Innovation and Engagement Programme Fund (2018-24, £4.4 million) Focus on providing responsive expert advice and technical assistance on safeguarding to DFID/FCDO, piloting and implementing approaches to raise safeguarding standards for DFID/FCDO to pursue, and engaging and convening partners to drive up standards and deliver culture change across the international aid sector. |

| Project Soteria (2019-25, £10 million) Support to organisations in the aid sector to stop perpetrators of SEAH from working in the aid sector via more and better criminal record checks on staff. Includes collaboration with Interpol and the UK criminal records body, ACRO. |

| Safeguarding Resource and Support Hub (2019-24, £10 million) Support to organisations which deliver international aid to strengthen their safeguarding policy and practice against SEAH. Primarily intended to support smaller, local NGOs in developing countries and those operating in high-risk environments which are least able to pay for this support themselves. To be delivered via an open-access, online platform and regional hubs initially in Ethiopia, Nigeria and South Sudan. |

| Supporting Survivors and Victims of Sexual Exploitation and Abuse and Sexual Harassment (2020-25, £3.7 million) Support through four components: promoting and strengthening some reporting mechanisms, improving the aid sector’s capacity to conduct high-quality investigations, improving delivery of support to survivors in country, and promoting the range and quality of services available to survivors. |

Humanitarian context

Protracted and acute humanitarian emergencies, including conflict, natural disasters and widespread and often systematic violations of human rights, cause devastation to millions globally. Climate change combined with the socio-economic fallout of the COVID-19 pandemic mean that humanitarian emergencies are expected to rise in coming years. The 2021 Global Humanitarian Overview states that a record 235 million people will require humanitarian assistance in the next year, an almost 40% increase on 2020, attributed primarily to the impacts of COVID-19. It is estimated that approximately one in four people in need of humanitarian assistance are women and girls of reproductive age, who, along with other marginalised groups, are particularly at risk of SEA. This may be exacerbated by the socio-economic impacts of the pandemic, including loss of income, school closures and restriction of access to health and social services.

The urgency, speed, high influx of new staff, and quick turnaround times associated with many emergency contexts often mean that safeguarding is not prioritised. During the Ebola crisis in the Democratic Republic of Congo in 2020, the surge in new responders combined with a high demand for and unequal access to essential goods increased the risk of SEA, and similar trends are present during the current COVID-19 pandemic.

In 2020, the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs’ (OCHA) Financial Tracking Service (FTS) listed the UK as the fourth-highest bilateral spender of humanitarian assistance behind the US, Germany and the European Commission. Table 3 provides a breakdown of UK humanitarian expenditure since 2018. We note, however, that there is expected to be a significant decline in 2021 following the reduction in the official development assistance spending target to 0.5% of gross national income. Because of the way spend is recorded, it is not possible to quantify the spend on safeguarding initiatives included in the amounts shown.

FCDO’s Conflict, Humanitarian and Security Department (CHASE) responds to humanitarian needs arising from conflict and natural disasters. Most of CHASE’s humanitarian programming is not tied to a specific theme such as PSEA. The largest portion of CHASE programming is for core funding to key humanitarian partners. This funding is unearmarked and provides agencies with the flexibility to disburse funds rapidly, to respond immediately when a crisis hits, to perform anticipatory action so crises are less severe, to respond to neglected crises, and to invest in central functions (including safeguarding mechanisms) which enhance efficiency and controls across their global operations. The flexible nature of this funding means that FCDO cannot attribute any single PSEA initiative to any specific programme.

Table 3: UK government humanitarian spend 2018-19 to 2020-21

| Funding channel | 2018-19 | 2019-20 | 2020-21 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bilateral spend in country | £1,346m | £1,567m | £1,440m |

| Multilateral core support to UN and Red Cross organisations | £276m | £487m | £255m |

| Humanitarian Response Group | £34m | £34m | £34m |

| Central COVID-19 programming classified as humanitarian | £111m | ||

| total | £1,656m | £2,088m | £1,840m |

Source: FCDO management information, January 2021 Humanitarian Quarterly Report

Review questions

The review is built around the evaluation criteria of relevance, coherence and effectiveness. It will address the questions and sub-questions listed in Table 4.

Table 4: Our review questions

| Review criteria and questions | Sub-questions |

|---|---|

| Relevance: How well has the UK government gone about building a relevant and credible portfolio of safeguarding programmes and influencing activities? | • How relevant and appropriate is the UK government’s approach to PSEA? • How relevant and appropriate is the UK’s approach to building the evidence base on the scale and nature of PSEA and on ‘what works’ in prevention and response? • How well does the UK government’s approach reflect the needs and priorities of affected communities in humanitarian contexts and of victims/survivors? |

| Coherence: How well does the UK work with other donors and multilateral partners to ensure a joined-up global approach to PSEA? | • Is the UK’s approach coherent and consistent with the efforts of other humanitarian funders and agencies, and does this reflect a shared approach across government? |

| Effectiveness: How effective is the UK’s approach to PSEA at programme, delivery partner and sector-wide levels? | • How effective is the UK government’s support to its implementing partners to strengthen systems, train staff and engage communities in preventing, detecting and responding to SEA (including investigating allegations, taking action against perpetrators and supporting witnesses and victims/survivors)? • How effective is the UK’s approach in responding to incidents and preventing perpetrators from reoffending? • To what extent have PSEA measures promoted by the UK led to changes in attitudes and behaviours in humanitarian operations? |

Methodology

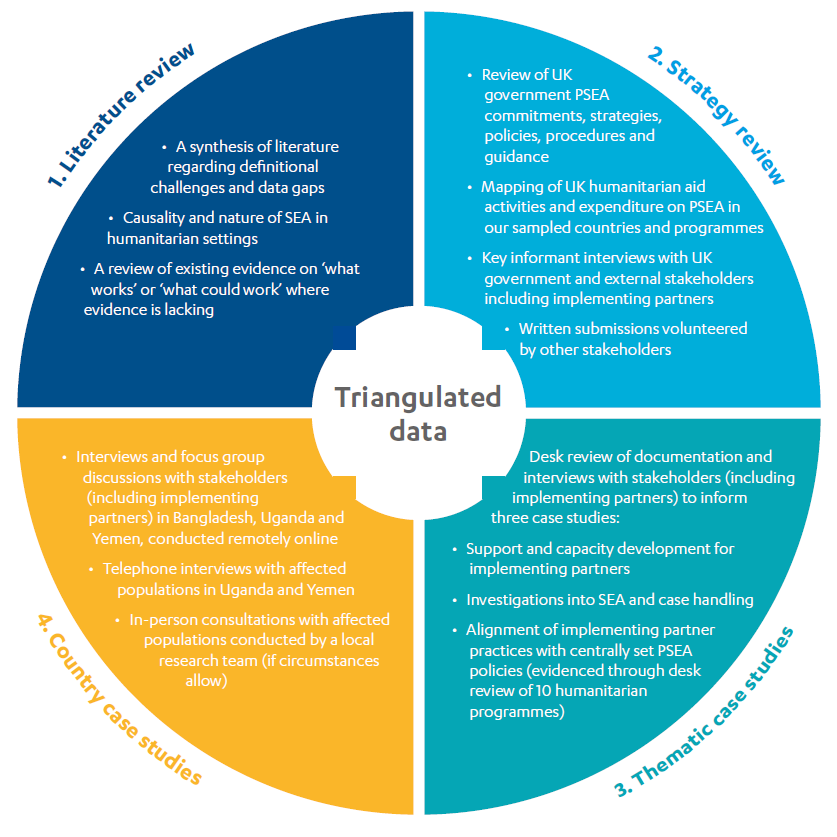

The methodology for the review will involve four main components, each used to inform and triangulate findings in the others. The review will draw on expert and stakeholder opinions, including those of affected people in humanitarian settings, and will be informed by a robust literature review.

Figure 1: Methodology

The methodology will have the following components:

Literature review: We will conduct a review of the available peer-reviewed literature and grey literature (including news articles, blogs, investigative reports and guidance produced by the aid sector) related to SEA in humanitarian settings, published since the West Africa scandal in 2001-02.23 While this will inform all the review questions, it will primarily speak to questions under ‘relevance’ and ‘coherence’, outlining the strength of available research and evidence on ‘what works’ in preventing and responding to SEA in humanitarian aid settings while highlighting gaps in the evidence base. This will help respond to questions about how relevant and appropriate the UK government’s approach is, the extent to which evidence and best practice underpin its strategy and approach, and the coherence of the UK’s approach with that of other actors and initiatives.

The key topic areas for the literature review will include:

- definitional issues

- availability and robustness of data on SEA

- evidence, experience and knowledge about the prevalence and nature of SEA in humanitarian settings

- what is known in terms of ‘what works’ in PSEA in the humanitarian aid sector.

In relation to this last topic, we will pay particular attention to the extent to which the literature – through its use of sources and analyses – focuses on and includes victim/survivor needs, experiences and voices. We will also assess the extent to which the literature looks at the disproportionate risks of SEA based on age, disability, race, ethnicity, religion, marital status, class, social group(s), sexuality, sex and gender identity, and where these intersect.

Strategy review: We will conduct a review of the UK government’s approach to addressing SEA in humanitarian settings. This will include assessment of strategy papers, guidance, evidentiary bases for interventions and theories of change, to determine whether they are internally coherent and reflect the available evidence to inform interventions identified in the literature review. We will also map UK humanitarian aid activities and expenditure on PSEA in our sampled countries and programmes to give strategic perspective to our country case studies and to inform the sampling of our programme desk reviews. In addition to document reviews, our strategic review will be informed by stakeholder interviews with the responsible UK government staff and key external stakeholders, including international organisations, UK NGOs and members of the FCDO-convened ‘Independent Reference Group’ made up of academic experts active in the area. Alongside interviews we will be inviting anyone wishing to respond to the review questions to submit their written submissions through an online facility accessed through the ICAI website. This facility will offer space for voices that might not otherwise be heard and will allow for issues that we might not be aware of to be raised.

Thematic case studies: We anticipate taking an in-depth look at three aspects of the UK government’s programming work.

Support and capacity development for implementing partners: This will critically assess how the UK’s work has strengthened efforts to identify and fill evidence gaps and share information, improved information and guidance to partners on best practice and compliance, including through the Safeguarding Resource and Support Hub, and ensured partners have sufficient resources and capacity to implement best practice, including consultation with affected communities, especially victims/survivors. This case study will be evidenced through the systematic review of policy and programme documents and key informant interviews, including with implementing partners.

Investigations into SEA and case handling: We will undertake a deep dive into FCDO’s oversight of complaints involving partner organisations, from how it receives concerns through to investigation and follow-up. This will include looking at how FCDO handles complaints and investigations and will be evidenced by reviewing a sample of cases handled by FCDO’s Safeguarding Investigations Unit. The cases will be sampled through various methods such as random and purposive sampling. The review will consider FCDO policies, processes and guidelines and may also look at external good practices.

Alignment of implementing partner practices with centrally set PSEA policies: This will assess the extent to which PSEA policies have been implemented in practice. The thematic study will include desk reviews of up to ten programme components to seek evidence in relation to:

- how effectively FCDO supports partners to strengthen systems and build capacity to prevent, detect and respond to SEA throughout the supply chain, including response to incidents and prevention of reoffending

- the relevance of measures to ensure central policies are implemented throughout the supply chain, from central to local level, including private sector suppliers

- the engagement of affected communities in the design of mechanisms, responses and programme monitoring and evaluation systems

- the consistency and appropriateness of engagement with and support to victims/ survivors of SEA.

The majority (up to eight) of the programme components reviewed as part of this case study will be sampled from our selected countries so that they, our virtual country visits and community engagement can inform each other.

We will use purposive sampling to select up to two additional programme components for desk review, to evidence this or other thematic issues that emerge during the review.

Country case studies: Case studies of Bangladesh, Uganda and Yemen will seek evidence of the relevance, coherence and effectiveness of the government’s approach to PSEA, and consider the impact of centrally managed UK PSEA programmes on the humanitarian aid sector and affected communities. Case studies will assess how effectively UK policies on PSEA are embedded in humanitarian programming in each country, and the consistency of policy implementation across different countries, with particular reference to the prevent/listen/respond/learn framework elaborated in the UK government’s sector-wide theory of change. Building on the work of the IDC, we will consider the centrality of community participation in every aspect of prevention and response, including design, reporting and victim/survivor support. The country case studies will also consider the impact of reductions and cuts to UK humanitarian funding, the DFID/FCO merger, and the length of programming cycles on delivery of PSEA objectives.

These case studies will be informed by the literature review, strategy review, desk review, community engagement, and interviews and focus group discussions with country-based representatives of relevant partners, including implementers and advocates from government, the UN, NGOs, civil society actors and the private sector, as well as UK missions. Due to COVID-19-related travel restrictions, interviews and focus group discussions will be conducted remotely.

Engagement with affected populations: Affected people will be consulted to assess whether UK government programmes are needs-based, effective and accountable. Engagement will provide:

- voice: enabling the review to reflect the voices of affected communities, including victims and survivors, where UK humanitarian aid programming is implemented

- evidence: primary data collected from affected communities will be an important source of evidence in answering the review questions, and in testing the claims and assumptions of implementing partners about how they engage with affected communities.

The views of affected people will inform questions related to community awareness and empowerment, perceptions of the conduct of aid workers, involvement in the design of reporting mechanisms, and understanding of and barriers to the use of these mechanisms. It will also provide perceptions of how effectively incidents are followed up, including support to victims/survivors and accountability for alleged perpetrators.

As circumstances allow, affected people will be engaged in person through focus group discussions conducted by a locally based research team. At-risk groups to be consulted may include, but not be limited to, youth and adolescents, people with disabilities, and people belonging to groups that are marginalised for reasons of identity (for example LGBTI+), religion, ethnicity or other characteristics.

Remote interviews will be conducted with selected communities in Uganda and Yemen using computer-assisted telephone interviewing. It is anticipated that around 600 people’s views will be solicited through these different primary data collection methods.

As there are sensitivities in addressing these issues with communities, affected people will be engaged only to the extent needed to inform the evidence. Consultation will focus on whether and how affected people perceive an improvement in their safety and ability to raise concerns as a result of efforts to prevent and respond to abuse in UK-supported humanitarian responses. The review will take a trauma-informed approach and will not probe individuals for their testimony or accounts of their experiences of SEA. As it is important for affected people’s voices to be heard as directly as possible, quotations and stories that speak to the review questions and findings will be included in the report where appropriate and with informed consent.

Sampling approach

FCDO has provided ICAI with a breakdown of its humanitarian spend and programming. In shortlisting our sampled countries and programmes, we considered a range of criteria.

Country sampling

In shortlisting case study countries we took the following criteria into account:

- level of UK financial contribution to the humanitarian response as of January 2021

- number of SEA cases reported in last four years

- breadth of cultural and regional contexts, including Asia, the Middle East and Africa

- diversity of contextual factors, including conflict, mass displacement and natural disaster

- range of in-country partners and humanitarian interventions

- practical considerations, such as mobile telephone service coverage to facilitate remote engagement, and civil society presence.

Based on these criteria, Bangladesh, Uganda and Yemen were selected as country case studies. Salient features informing their selection are listed for each country below.

Bangladesh:

- acute and protracted crisis affecting the Rohingya people

- high level of UK humanitarian spend (£87 million in the financial year 2020-21)

- highest number of SEA cases reported to FCDO between 2018-20

- accessibility for local research teams to engage with affected communities in refugee camps in Cox’s Bazar

- significant numbers of civil society organisations working outside of the humanitarian response able to provide independent assessment of the approaches to PSEA taken by humanitarian sector actors.

Uganda:

- mid-level number of reported SEA cases

- mid-level UK humanitarian spend (£27 million in the financial year 2020-21, which was significantly less than in previous years, and may provide data for an assessment of how cuts can impact PSEA efforts)

- largest refugee-hosting country in Africa

- unique and widely acclaimed progressive government policy of settling refugees in communities (rather than in refugee camps as other countries do) and giving them the right to work and freedom of movement through its self-reliance model

- substantial civil society outside of the humanitarian response

- provides an opportunity for read across to South Sudan due to the large population of South Sudanese refugees.

Yemen:

- described by OCHA as the world’s “worst humanitarian crisis”

- received the highest overall UK humanitarian spend (approximately £221 million in the financial year 2020-21)

- low number of SEA cases reported to FCDO, suggesting significant under-reporting

- diversity of humanitarian partners and delivery modalities, particularly in light of access constraints

- managed by FCDO remotely (no in-country FCDO humanitarian team presence).

Programme sampling:

To select the programme components in our chosen countries for desk review, we compiled a list of humanitarian programmes under implementation in each country using information recorded in FCDO’s Devtracker and cross-referenced with OCHA’s FTS for humanitarian programmes. As well as the type of programme and amount of humanitarian spend, we identified the range of multilateral partners and UK suppliers involved in humanitarian programme delivery in each country (as listed in Table 5).

Table 5: Main implementing partners delivering UK-funded humanitarian programmes in selected countries across the review period

| Country | Partners* |

|---|---|

| Bangladesh | IOM, UNHCR, WFP, UNFPA, WHO, FAO, UNDP multi-partner trust fund, ICRC, IFRC (British Red Cross), Christian Aid Consortium, Action Against Hunger (ACF) Consortium, Handicap International, HelpAge International, Solidarities International, BRAC, BBC Media Action and Start Fund Bangladesh |

| Yemen | CARE, ADRA, ICRC, IOM, UNCHR, Palladium, UNOPS, UNHAS, WFP, UNICEF, World Bank, OCHA and SFD |

| Uganda | WFP, UNICEF, Mercy Corps, World Bank, Palladium, Save the Children (U Learn) Consortium, WHO |

* See the list of acronyms for the full names of partners. Implementation is likely supported by other smaller organisations via sub-contracting arrangements.

In finalising the shortlist of programme components to review we will apply the following criteria:

- programmes at ‘high risk’ for SEA, involving direct interaction with at-risk individuals and communities

- diversity of funding mechanisms in use, including programme components funded directly, subcontracted through UN, international non-governmental organisation and private sector partners, and through mechanisms such as pooled funds

- size and nature of spend

- UK share of funding, to facilitate attribution of the impact of UK funding and influence.

We will interview field-level representatives of the partners implementing selected programme components in sampled countries to inform our programme desk reviews and will triangulate their evidence with that provided by internationally based representatives of implementing partners.

Within the sample of programmes to review we will look at how PSEA interventions interact with violence against women and girls (VAWG) programming and/or other PSEA work (such as governmental or development), and whether the absence of such initiatives creates a gap in safeguarding responses. Mechanisms such as the Standby Partnership Programme will also be considered to assess how they are used to contribute to PSEA work or show evidence of mainstreaming.

Limitations to the methodology

SEA definitions are contested and variously interpreted. This may have implications for stakeholder engagement on the issue, particularly internationally where there is higher variation in understanding. SEA is also a highly sensitive issue and has led to the UK withdrawing funding from certain organisations. This may impact on stakeholders’ willingness or ability to speak candidly, particularly if they are receiving funding. An online facility will give stakeholders an avenue to contribute anonymised written submissions to the review.

PSEA requires action under every UK aid-funded humanitarian programme. The scope of the review is therefore broad, making it difficult to identify a representative sample of activities to review or to generalise findings to humanitarian aid as a whole.

Most of the centrally managed safeguarding programmes listed in Table 2 that have a bearing on humanitarian field-level practices are still at an early stage of implementation, having been launched in late 2018. There is therefore limited data available at this stage on results achieved, which may require us to qualify our findings on effectiveness.

Most programmes have not been independently evaluated, and it will therefore be difficult to attribute changes to the intervention. Direct attribution of changes to UK interventions is also difficult given the broad nature of the challenge and the diverse array of actors involved in championing and contributing to sectorwide change.

The ongoing COVID-19 pandemic has required us to adapt our approach to conducting in-country fieldwork. While the majority of our key informant interviews, focus group discussions and engagement with affected communities will be conducted online or by telephone, if circumstances allow, locally based research teams will conduct focus group discussions in person. Local COVID-19 travel and meeting restrictions will be strictly observed to minimise any risk of infection to participants and the research team involved in facilitating these focus group discussions in person. Should these change during the review period, plans will be adapted.

Limited data and peer-reviewed literature on the scale and nature of SEA in humanitarian contexts makes assessment a challenge. This will be addressed through consultation with PSEA sectoral experts, both externally and within the review team.

As the IDC has conducted a related inquiry, we will minimise duplication by focusing on implementation of PSEA policy in practice.

The review will make use of monitoring and evaluation data provided by FCDO’s central safeguarding teams and the country programmes. We will manage risk of bias by interviewing counterparts, partners and affected communities, among other stakeholders. This will enable us to draw our own conclusions on the results achieved by FCDO. However, access limitations and the broad scope of this inquiry will inevitably limit the capacity to draw independent conclusions about programme effectiveness to some extent.

Research ethics and safeguarding

It is important to our review that at-risk members of affected populations are consulted about how effective they think prevention and response measures have been. However, PSEA is a sensitive topic to discuss with communities. Sexual violence, exploitation and/or abuse is a deeply personal and painful experience for victims/survivors. Moreover, there may be high personal and social risks for victims/survivors in disclosing abuse or exploitation, due to cultural and social norms that can result in stigma and therefore further abuse, including economic, social and physical suffering. There is also a risk to victims/survivors of retribution from both alleged perpetrators and those close to them.

For these reasons, when engaging with affected people, we will follow a set of strict research protocols designed to minimise the risk of distress or harm to participants. The dialogue with affected people will be conducted sensitively, in the interviewees’ preferred language, and participants will be advised of their right to end their participation at any time.

The research will focus on participants’ experience with UK aid interventions, rather than their direct experience of SEA. We will not explicitly seek to consult victims or survivors. However, we cannot be certain that they will not be consulted as people at risk of SEA. To ensure that they, and others, are protected and supported, we will take a trauma-informed and survivor-centred approach to consultations that respects people’s rights, protects their anonymity and avoids re-traumatisation or the risk of retaliation by perpetrators. We will ensure follow-up support is signposted if needed. The review will be conducted in a conflict-sensitive manner, recognising the complexities of the contexts, and of Yemen in particular.

We will obtain the informed consent of participants, following written or oral explanations of the purpose of the research. For any children that are involved in group discussions, there will be an enhanced consent process to include the consent of parents, guardians or other responsible adults.

We will respect the confidentiality of information collected during the research. Information on the identity of participants will be kept strictly confidential and separate from our interview notes. In accordance with UK law and the General Data Protection Regulation it will be retained only as long as is necessary for the purposes of the research, as explained to participants. Information from participants will only be used in an anonymised form in reporting so that it cannot be traced back to specific individuals.

Closing the loop

The research team leading in-person focus group discussions will identify options for reporting the results of the research back to the involved affected communities. These options might include identifying local civil society organisations, media outlets or social media networks.

At the conclusion of the research, the research team will produce a short summary (approximately two pages) of headline findings from the field research. This will be shared with those involved in the consultations through the identified channel.

Safeguarding

The review team will follow ICAI’s policy regarding SEA, and each researcher will be fully trained in the research protocols and ethical requirements for this assignment.

Researchers are subject to the standards set out in the UK government’s Safeguarding Against Sexual Exploitation and Abuse and Sexual Harassment within the Aid Sector strategy and FCDO’s Supply Partner Code of Conduct and in the service provider’s Code of Conduct for research.

In the event that any concerns about sexual exploitation or abuse in connection with ICAI’s review or a UK aid programme come to light during the course of the fieldwork, the review team will report the matter in a timely manner to FCDO’s reporting mechanism (reportingconcerns@fcdo.gov.uk) and inform ICAI’s head of secretariat.

Before commencing the field research, the review team will undertake security and COVID-19 risk assessments, and follow local advice on safety, travel and meeting restrictions.

Risk management

The main exogenous risks to the review are shown in Table 6. “Shocks” include potential worsening of the COVID-19 epidemics in each country, as well as the heightening of humanitarian crises associated with conflict, rapid-onset natural disasters or similar.

Table 6: Exogenous risks to the review

| Risk | Mitigation and management actions |

|---|---|

| Case study countries are vulnerable to further humanitarian and COVID-19 shocks that could impact research plans | We will monitor the humanitarian and COVID-19 context in each country (including the spread of the Delta COVID-19 variant) and liaise with our research teams to identify and respond to shocks. We will be guided by security and local travel/meeting advice and adapt research plans as necessary. |

| Consultation with victims/survivors of SEA causes distress and could lead to re-traumatisation and further victimisation | We will not explicitly seek to consult victims and survivors, but we cannot be certain that they will not be consulted through interviews or focus group discussions. To mitigate this risk, we will adopt strict ethical research protocols and take a trauma-informed and survivor-centred approach to consultations that respects people’s rights, protects their anonymity, and avoids re-traumatisation or risk of retaliation by perpetrators. We will ensure that follow-up support is signposted if needed. |

Quality assurance

The review will be carried out under the guidance of ICAI lead commissioner Sir Hugh Bayley, with support from the ICAI secretariat. The review will be subject to quality assurance by the service provider consortium.

Both the methodology and the final report will be peer-reviewed by Dr Synne L Dyvik. Dr Dyvik is a senior lecturer in international relations at the University of Sussex and has expertise in safeguarding, humanitarianism and development.

Timing and deliverables

The review will take place over a ten-month period, starting from May 2021.

| Phase | Timing and deliverables |

|---|---|

| Inception | Approach paper: July 2021 |

| Data collection | Country visits: June – August 2021 Evidence pack: September 2021 Emerging findings presentation: September 2021 |

| Reporting | Final report: February 2022 |