The UK’s approaches to peacebuilding

Score summary

The UK government’s peacebuilding efforts are largely relevant and coherent, and achieve results at local and national levels, but these results would be even more significant if its funding were more reliable and patient

The UK government’s peacebuilding work combines peacebuilding programmes with diplomatic efforts, and sometimes with military support. ICAI only assessed work that was financed from the aid budget. After the significant reductions in the UK’s aid spending, this combination of approaches remained important but the emphasis shifted towards diplomacy, and the programmes became less predictable. The UK government’s peacebuilding work is relevant and built on a foundation of expertise, context assessments and central guidance. Monitoring and evaluation of programming relevant to peacebuilding improved during the review period. The government applied some of the learning generated by monitoring and evaluation and research activities, and shared some of this learning with other stakeholders and the wider public.

The work was gender- and conflict-sensitive and aligned with the UK’s Women, Peace and Security commitments. It often focused on particularly vulnerable communities, but did not actively pursue accountability to these communities, or to conflict-affected communities more broadly. The UK government did not achieve its over-ambitious peacebuilding targets but did achieve positive results at national and community levels, although not all results were sustained. Reductions in the aid budget led to hasty project terminations that caused harm.

In-country, the UK government had a leading role among international partners, and worked closely with host governments. It was respected by both like-minded international partners and host governments for its knowledge and coherence – even though many UK-funded projects were of inappropriately short duration, and some had taken a long time to develop. The government also worked through the wider multilateral peacebuilding architecture, where it achieved positive results.

| Individual question scores | |

| Relevance: How well has the UK government responded to different contexts in its peacebuilding approaches? |  |

| Coherence: How internally and externally coherent are the UK’s peacebuilding approaches? |  |

| Effectiveness: How well has the UK contributed to peacebuilding objectives in areas in which it operates? |  |

Executive summary

Conflict forcibly displaces and kills people, and has immediate and longer-term effects on poverty and economic development. Political, social, economic, military and increasingly environmental drivers of conflict are interlinked, and often have a regional dimension. The number of conflicts is on the rise and a quarter of the global population now lives in conflict-affected countries. Countries emerging from violent conflict have a high likelihood of relapsing into new conflict. When they do, it is almost always over the same or related issues.

The UK government has long invested in addressing drivers of conflict and helping to build peace in fragile and conflict-affected countries and regions. The May 2022 UK government’s strategy for international development reconfirms that “we must help countries escape cycles of conflict and violence”. This review assesses how relevant, coherent and effective the UK government’s peacebuilding efforts have been in the period from 2010 until 2022. In addition, we assess the extent to which the UK government pursued gender equality and the Women, Peace and Security (WPS) agenda, as these are UK government priorities. We also consider how well the UK government engaged with those expected to benefit from the UK’s work, and how it incorporated the needs and priorities of vulnerable groups into the design.

We selected case studies from countries in which the UK government believes it has achieved at least some positive results through its peacebuilding activities. We did this because the international community often fails in its peacebuilding attempts, so there is much to learn from efforts that have had some success. Three of our case studies cover the UK’s peacebuilding work in a conflict-affected state (Bosnia and Herzegovina, Colombia and Nigeria), and the fourth covers contributions to the UN Peacebuilding Fund and the Joint Programme on Building National Capacities for Conflict Prevention (the ‘Joint Programme’).

Relevance: How well has the UK government responded to different contexts in its peacebuilding approaches?

Access to regions that are in active conflict is often highly constrained and has been worsened by the COVID-19 pandemic. In Nigeria, we found that the UK government’s travel rules for its staff were risk-averse compared to the rules of almost all other international partners, and that this further reduced access of UK government representatives. Travel restrictions can have an impact on the ability of the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO) to maintain local knowledge and engage directly with conflict-affected people.

Where access is possible, the UK government conducts or commissions contextual assessments of conflict settings. Backed by strategic guidance, these assessments include significant engagement with women, youth and a range of vulnerable groups. The identity of these vulnerable groups is context-dependent. They include unemployed, former combatants and other people who have surrendered, forcibly displaced people, indigenous communities, marginalised ethnic groups, families of ‘disappeared persons’, and victims and survivors of sexual violence in conflict settings. People living with a disability receive less attention than is required by the UK government’s strategy on disability inclusion. Assessments are generally gender-sensitive and often cover options to empower women. They also prominently feature the UK’s WPS commitments. Collectively, these assessments provide an evidence base that is large, contextually relevant and credible.

The UK government uses this evidence base to inform programme and project design, the operationalisation of its WPS commitments, and its diplomatic work. The UK government also uses real-time situation analysis to ensure the ongoing relevance of its work in conflict contexts that are often volatile. It responded swiftly and appropriately to the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on conflict dynamics and peacebuilding efforts.

The links between evidence and analysis on the one hand, and the design of interventions on the other hand, are stronger for direct investments than for UK government contributions to multilateral efforts. In the latter case, the UK government is one of several stakeholders. It often contributes to group decisions but is not in a position to make decisions independently. In recent years, the UK government’s theories of change at programme and portfolio level grew stronger and more evidence-based, albeit from a low base and with exceptions. An important blind spot, for example, is that the original theory of change for the Lake Chad Basin did not explicitly cover environmental degradation. Theories of change continue to be over-optimistic about the extent of likely progress and to underestimate the many obstacles that peace processes typically encounter.

The UK funds and encourages engagement with conflict-affected communities and with vulnerable groups among them. However, it does not systematically require or actively encourage its implementing partners to have systems and mechanisms in place to ensure that conflict-affected communities are meaningfully and continuously involved in project decisions that directly affect their lives, and does not monitor the extent to which this is the case. Some UK government officials did not show awareness of the importance of such ongoing accountability towards conflict-affected communities. Several implementing partners do ensure accountability, with positive effects. However, in other cases the meaningful involvement of affected communities dwindles after the initial phase, and fully functioning accountability mechanisms remain uncommon.

We award a green-amber score for the relevance of the UK’s peacebuilding approach in our four case studies, and note the importance of strengthening accountability to conflict-affected communities.

Coherence: How internally and externally coherent are the UK’s peacebuilding approaches?

Over the course of the review period, the UK government increased its emphasis on the need for a joined-up approach where the UK’s diplomatic, programme and military efforts reinforce each other, and official development assistance (ODA) and non-ODA activities are aligned. The merger of the Foreign and Commonwealth Office and the Department for International Development, and the UK aid budget reductions of 2020 and 2021, have not changed the preference for joined-up action, although they have led to a stronger emphasis on diplomatic influencing.

At headquarters level in the UK, close cross-governmental cooperation in the field of peacebuilding is not yet standard practice. The redirecting of staff to Brexit preparations and the COVID-19 response, the ongoing restructuring within the merged FCDO together with considerable turnover in key positions, and two rounds of aid budget reductions have reduced FCDO’s capacity to lead cooperation efforts. The newly established FCDO-based Office for Conflict, Stabilisation and Mediation could potentially guide the UK’s efforts in the broad field of peacebuilding, but it does not have strong senior backing across relevant UK government departments and its counterparts outside FCDO appear to have little incentive to cooperate.

The UK government’s joined-up approach has long been applied to its work in relation to the UN peacebuilding architecture. First, the UK government combines financial contributions, staff secondments and diplomatic influencing work in relation to the UN Peacebuilding Fund and the Joint Programme. This has helped ensure that the Peacebuilding Fund and Joint Programme took shape in a manner that aligned with UK priorities. Second, the UK government’s in-country programmes and diplomatic efforts inform the UK’s country-specific and wider work in the UN Security Council.

UK government staff in our case study countries Bosnia and Herzegovina, Colombia and Nigeria also applied the joined-up approach. The cooperation between different UK funding mechanisms is generally good. Moreover, the cross-fertilisation of the UK government’s programmatic, diplomatic and military efforts strengthened in the second half of the review period.

Within our case study countries, the UK maintained its position as a respected donor, partner and influencer. In its work with host governments, the UK uses its joined-up approach to help strengthen the host governments’ focus on and capacity for peacebuilding. In doing so, the UK government utilises its strong and long-standing relations with host governments. The UK values these relations and is therefore reluctant to criticise host government actions in public. In Nigeria and Colombia, the host governments’ patchy peacebuilding and human rights records mean that the close links to them bring significant reputational risk for the UK government, and support to security forces incurs the risk of contributing to harm. The UK government accepts these risks because the potential results are significant and because its long-term role as a trusted critical friend to the host government is a key component of the international peacebuilding effort as a whole. Within the wider international community in Colombia and Nigeria in particular, the UK helps coordinate the wider international peacebuilding efforts. The UK does this in-country and through the UN Security Council, where the UK serves as the penholder for the Colombian peace process and for the conflict in the Lake Chad Basin. The UK also does this as part of its wider efforts to optimise the multilateral peacebuilding system.

We award a green-amber score for the coherence of the UK’s peacebuilding approach. The UK’s joined-up approach has helped it maintain its position as an influential peacebuilding partner despite some deficiencies in cross-government coherence.

Effectiveness: How well has the UK contributed to peacebuilding objectives in areas in which it operates?

The UK government has a high level of expertise and has continued to learn, and to encourage its staff to learn, in order to strengthen the effectiveness of its peacebuilding activities. However, mechanisms to absorb this learning are insufficiently institutionalised and only part of the learning has been absorbed in guidance and applied to aid programmes. Where insights were not sensitive, learning has often been shared with other stakeholders and the public.

In the years after 2017, the UK government improved its peacebuilding-related monitoring and evaluation (M&E). Datasets were more systematically disaggregated by gender and age, and tools and methods became more varied and fit for purpose. M&E still serves the purposes of learning and accountability, but some of the more recent monitoring efforts also facilitate mid-way course correction of projects and support the host government’s real-time decision-making. M&E increasingly helps the UK government to compare the overall results of programmes and regional and global portfolios. Such comparisons can potentially be used to strengthen decision-making on budget allocations across interventions, but they were not fully utilised to inform the aid reprioritisation decisions made to accommodate aid budget reductions in 2020 and 2021. Moreover, some M&E investments were wasted when programmes were cut short. Lastly, in some cases stringent M&E requirements incentivised short-term results at the expense of longer-term and more uncertain transformational results.

Because of the nature of peacebuilding work, the attribution of results to UK support has a margin of uncertainty. The following findings on the effectiveness of the UK’s peacebuilding work should be read with this caveat in mind.

The UK government played a key role in the establishment and development of the UN peacebuilding architecture. The UK’s funding to the Peacebuilding Fund and Joint Programme is generally unrestricted. This is appropriate because a series of external evaluations confirm that both are performing well.

Working with host governments in conflict-affected countries incurs high risks and potentially achieves important results. The appropriate criterion for effectiveness is not whether there were interventions that failed but whether some of them succeeded in making meaningful contributions to peacebuilding. The UK government did achieve results with its work with these governments, although it failed to achieve many of its targets as these were often unrealistic and assumed a level of influence that an outside government would not ordinarily have. The UK government achieved its most notable results in Colombia, where its peacebuilding effort has a ten-year horizon (2015–25). This long-term commitment allowed it to take a patient approach and to adapt its efforts to an evolving context. It contributed to the design and funding of key mechanisms that helped move the implementation of the peace agreement forward. Examples are a system of UN-mandated monitoring, the Trust Fund for Sustainable Peace in Colombia and the establishment of ‘liaison officers’ who served as the interface between central authorities and a multiplicity of local stakeholders. During the presidency of Iván Duque (2018–22), whose campaign pledge had been to modify the peace agreement, the UK helped avoid a government withdrawal from the original agreement.

In addition to its support for national peacebuilding processes, the UK government made significant contributions to local peacebuilding. As is the case with country-level targets, local targets were frequently overly ambitious. There was insufficient attention to the localisation of the peacebuilding effort. Some projects that over-promised or that were terminated hastily caused harm because unfulfilled promises aggravated grievances. In the north of Nigeria, where gender inequalities are high, hasty project termination left women who had risked exposure by participating unprotected. However, UK efforts did achieve positive results. In Nigeria, for example, UK-funded peacebuilding activities helped build trust within and among communities, and between them and security forces and government authorities. The UK also helped raise levels of women’s public participation in peacebuilding efforts, and awareness about women’s safety and rights. However, in a wider Nigerian context of increasing conflict and fragility, these results are fragile. Moreover, the results were more modest than they could have been, because of the short duration of projects and the unpredictability of the UK’s funding decisions.

We award a green-amber score for effectiveness, based on some significant results achieved, particularly in Colombia where the UK’s patient and long-term approach has helped keep the peace agreement alive. However, the impact and sustainability of UK efforts would be strengthened if shortcomings such as overly ambitious targets, short and sometimes abruptly terminated programme cycles, and the limited institutionalisation of learning related to peacebuilding were addressed.

Recommendations

We offer the following recommendations to strengthen the long-term effectiveness of the UK government’s peacebuilding efforts.

Recommendation 1

The UK government should preserve its ‘thought leadership’ capabilities in the field of peacebuilding.

Recommendation 2

The UK government’s patient, strategic and risk-taking approach to peacebuilding at country and regional levels should extend to its partnerships at programme level.

Recommendation 3

The UK government should strengthen accountability to affected people in its peacebuilding work.

Recommendation 4

In its peacebuilding work, the UK government should maintain its focus on countries and regions in which it maintains strong, long-standing and multifaceted relations with host governments.

Recommendation 5

The UK government should learn from and, if possible, build on initiatives in which it seeks to pursue peacebuilding and environmental goals simultaneously.

Recommendation 6

The UK government should consider what can be learned from other countries when balancing travel risks in conflict-affected settings with the aim that UK government representatives have more access to regions for which they design and manage programmes.

1. Introduction

1.1 The number of violent conflicts in the world has risen dramatically in recent years. Conflict does not only cause death, destruction and suffering, but also reinforces poverty and exacerbates inequalities. Conflict causes mass displacement, with more than 100 million people forcibly displaced in 2022. Environmental degradation and climate change can both heighten the risk and worsen the effect of conflict. The multiple and mutually reinforcing drivers of conflict, often with strong cross-border and regional dimensions, combined with conflict’s adverse effect on poverty and inequality, make peace difficult to achieve and the risk of relapse into conflict high. Peacebuilding activities aim to support communities in conflict-affected and fragile states to break out of the conflict cycle and establish the conditions for lasting peace and sustainable development.

1.2 This review is relevant to Sustainable Development Goal 16, which is to “promote just, peaceful and inclusive societies”. It is impossible to achieve many of the other Sustainable Development Goals without progress towards Goal 16 (see Box 1).

Box 1: How this report relates to the Sustainable Development Goals

The Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), otherwise known as the Global Goals, are a universal call to action to end poverty, protect the planet and ensure that all people enjoy peace and prosperity.

Related to this review

![]() Goal 16 is dedicated to promoting peaceful and inclusive societies for sustainable development, providing access to justice for all, and building effective, accountable institutions at all levels. Its targets include the following:

Goal 16 is dedicated to promoting peaceful and inclusive societies for sustainable development, providing access to justice for all, and building effective, accountable institutions at all levels. Its targets include the following:

- building capacity at all levels, in particular in developing countries, to prevent violence and combat terrorism and crime.

- Significantly reduce all forms of violence and related death rates everywhere.

- Ensure responsive, inclusive, participatory and representative decision-making at all levels.

- Strengthen relevant national institutions, including through international cooperation, for

- There are close links between conflict, stability and security and the other SDGs. The SDGs are all part of the 2030 agenda for sustainable development which states, in its preamble, that “there can be no sustainable development without peace and no peace without sustainable development”.

1.3 The UK government has long invested in addressing drivers of conflict and helping build peace in fragile and conflict-affected countries and regions. Using a case study approach, the purpose of this review is to examine how relevant, coherent and effective this cross-government investment has been. In addition, for each case study, we assess the extent to which the UK government pursued gender equality and the Women, Peace and Security agenda, as these are key UK government priorities. We also consider how well the UK engaged with those expected to benefit from its programmes, and how the UK incorporated the needs and priorities of vulnerable groups into its programme designs.

1.4 We have selected four case studies. Three of them cover the UK’s peacebuilding efforts in a conflict-affected state. A range of UK government departments contribute to peacebuilding efforts in the three countries, with the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office and the Ministry of Defence chief among them. The fourth case study covers the UK government’s contributions to the UN Peacebuilding Fund and the Joint Programme on Building National Capacities for Conflict Prevention (the ‘Joint Programme’). Together, the four case studies encompass a wide and diverse range of programmes and mechanisms. From these case studies, we seek to identify lessons that can be applied more broadly.

1.5 The review’s use of the term ‘peacebuilding’ covers the UK government’s aid and diplomatic efforts to address drivers of conflict, with the aim of helping to prevent and resolve conflict and consolidate post-conflict peace. While the UK government does not use ‘peacebuilding’ as an operational concept, it declared its intention to continue its efforts in this field in the May 2022 UK government’s strategy for international development, which reconfirms that the UK government “must help countries escape cycles of conflict and violence”.

1.6 In the absence of a pre-defined peacebuilding portfolio, the scope of this review has been determined by what UK government staff identified as the government’s most relevant peacebuilding work in the period from 2010 until 2022. Counterterrorism and other security-related operations and strategies are out of scope, and so is the broader development impact of the peacebuilding efforts we assess, unless we felt such impact enhanced or diminished the prospects of long-term peace. This review does not focus on safeguarding, so as not to overlap with ICAI’s 2022 review on the UK’s approach to safeguarding in the humanitarian sector, and ICAI’s 2020 review on sexual exploitation and abuse by international peacekeepers.

Table 1: Our review questions

| Review criteria and questions | Sub-questions |

|---|---|

| 1. Relevance: How well has the UK government responded to different contexts in its peacebuilding approaches? | • How well does the UK assess the drivers of conflict and opportunities for peacebuilding in particular contexts and develop plausible theories of change for its interventions? • To what extent do the UK’s approaches to peacebuilding reflect the needs and priorities of vulnerable communities? • How well does the UK meet its commitments on Women, Peace and Security? |

| 2. Coherence: How internally and externally coherent are the UK’s peacebuilding approaches? | • How well have UK departments, funds and agencies worked together to deliver peacebuilding outcomes? • How well does the UK align its programming and diplomatic efforts towards peacebuilding? • Are the UK’s approaches to peacebuilding coherent with the efforts of the host government, and of other funders and agencies? |

| 3. Effectiveness: How well has the UK contributed to peacebuilding objectives in areas in which it operates? | • To what extent is the UK contributing to a resilient peace in the areas in which it operates? • How well does the UK measure and evaluate its contribution to peacebuilding? • How well is UK aid contributing to and learning from evidence, and adapting its approaches to peacebuilding on the basis of such learning? |

2. Methodology

2.1 Our methodology was designed to assess how relevant, coherent and effective the UK government’s investments in peacebuilding can be, and what the UK government could learn from its successes. We selected our case studies from a government-provided list of 18 countries and two regions in which the government believed it had achieved at least some positive results. We did this on the premise that, in the field of peacebuilding, where failures are common and successes relatively rare, there is more to learn from approaches that worked out well than from those that did not. Our Afghanistan country portfolio review covers an example of the latter.

2.2 We conducted our assessment on the basis of four case studies. Three of them are country portfolios (see Box 2 and Annex 1) and one is a series of multilateral contributions (see Box 3). The four case studies are:

- Nigeria, where there is ongoing and worsening conflict and fragility.

- Colombia, where the implementation of a 2016 peace agreement is ongoing.

- Bosnia and Herzegovina, where the Dayton peace agreement was signed in 1995 but which is yet to overcome the legacy of conflict.

- The UK’s long-standing contributions to the multilateral peacebuilding effort through the UN.

Box 2: Background to the case studies of Colombia, Nigeria, and Bosnia and Herzegovina

Bosnia and Herzegovina signed the ‘Dayton peace agreement’ in 1995 but has yet to overcome the legacy of conflict. The peace agreement put an end to the Bosnian war and established Bosnia and Herzegovina as a single state comprising the ‘Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina’ (principally made up of Bosnian Muslim- and Croat-majority areas) and ‘Republika Srpska’ (covering Serb-majority areas). The agreement did not address ethnic division and exclusion, and instead created a complex state structure with layers of government and ethnicity-based governance arrangements. The legacies of the violent conflict that have yet to be overcome include the lack of a full accounting for missing persons, the existence of parallel ethnicity-based structures, the denial of war crimes, and the neglect of the needs of victims and survivors of sexual violence committed during the war.

UK efforts in Bosnia and Herzegovina: In the early years of our review period, the UK government focused on state-building. In more recent years, its peacebuilding work has focused on the legacy of conflict, reconciliation and community cohesion. The UK’s Conflict, Stability and Security Fund (CSSF) funds projects that aim to help account for missing persons, work towards a sustainable and inclusive peace in Mostar (to set an example for the wider region), support wartime sexual violence victims and survivors, and build the institutional capacities of the Srebrenica Memorial in order to establish a globally relevant centre for genocide research and prevention, as well as a regional hub for reconciliation and inter-ethnic dialogue.

Colombia signed a peace agreement in 2016 and faces multiple challenges in the implementation of this agreement. For over 50 years, Colombia faced armed conflict between the government, paramilitary groups, crime syndicates and guerrilla groups such as the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) and the National Liberation Army. The conflict led to widespread loss of life and human rights abuses, and it undermined the development of large parts of the country. A peace agreement between the government of Colombia and FARC was signed in 2016. While progress has been made, implementation of many parts of the peace agreement has been slow. Moreover, after an initial reduction, violence has increased again in recent years. The government continues to lack a meaningful presence in conflict-affected areas, and crime syndicates have assumed control over some of the areas previously held by FARC. Deforestation has accelerated.

UK efforts in Colombia: The UK government is supporting the government of Colombia’s efforts to implement the peace agreement, tackle the underlying causes of conflict and reduce the speed of deforestation. In parallel, the UK government plays a coordinating role for the wider international peacebuilding effort. It does so in-country and as the UN Security Council’s penholder for the implementation of the peace agreement. The UK government also supports community-based programmes in conflict-affected rural regions. These are implemented by UN agencies and civil society organisations (CSOs). The Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO) works with other UK departments, such as the Ministry of Defence (MOD) and the National Crime Agency (NCA) on serious and organised crime, and the Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy on tackling the criminal drivers of deforestation. Most work is funded by the CSSF. Part of a recent programme that aims to strengthen the environmental rule of law in regions affected by the conflict is co-funded by the International Climate Fund.

Nigeria is facing worsening conflict and fragility. Conflict in Nigeria has multiple compounding drivers. In the Niger Delta, the main drivers are the oil industry’s environmental damage and the unequal distribution of oil revenues. In the Lake Chad Basin, key drivers of conflict are the insurgencies of Boko Haram and Islamic State West Africa, as well as government violence and human rights violations. Violent groups are exploiting grievances about government failure to facilitate development and deliver basic services. In the North West and Middle Belt zones, conflicts between farmers and pastoralists and bandit group activity have become increasingly violent. In all cases, climate change and environmental degradation drive or exacerbate conflict, and COVID-19 further undermined peacebuilding efforts.

UK efforts in Nigeria: The UK government supports the government of Nigeria at federal and state levels, in recent years with a focus on the Lake Chad Basin. Support focuses on the authorities’ commitment to peaceful settlements, and their capacity to stabilise and tackle threats, respect human rights, address the underlying causes of conflict and work towards Women, Peace and Security goals. In parallel, the UK government plays a coordinating role for the wider international peacebuilding effort. It does so in-country and as the UN Security Council’s penholder for the Lake Chad Basin. At community level, the UK government supports programmes, implemented by UN agencies and CSOs, that aim to enhance social cohesion, security and justice, improve the delivery of services, reduce the vulnerability of youth to recruitment by violent extremists, amplify the voice of citizens, and help create conditions for the reintegration of people who were formerly in the sphere of influence of violent groups. Work is implemented through FCDO, MOD and NCA, and is partially CSSF-funded.

Annex 1 provides an overview of the UK government’s programmes in these three countries.

Collectively, these four case studies include a diversity of programme investments, as well as diplomatic efforts and support to security forces. We only assessed parts that were financed by official development assistance (ODA). The case studies also include guidance and support from the UK government’s headquarters.

Box 3: The UK’s investment in multilateral peacebuilding through the UN

The fourth case study for this review covers the UK government’s contributions to the multilateral peacebuilding effort. This effort is long-standing. The UK’s Conflict Prevention and Peacebuilding Programme that started in March 2021 is the most recent contribution. This programme continues three types of contributions:

- UK secondments to the UN peacebuilding system.

- Contributions to the UN Peacebuilding Fund, which is the financial instrument of first resort for the UN to help sustain peace in countries or situations at risk of or affected by violent conflict. In our review period, the UK government was the third-largest contributor to the Peacebuilding Fund, after Germany and Sweden. It provided £133 million of unearmarked funding between 2010 and 2022. In recent years, the UK’s contribution was less prominent: it was the sixth-largest donor from 2020 until mid-2022.

- Contributions to the Joint Programme, which is a joint programme of the United Nations Development Programme and the UN Department of Political and Peacebuilding Affairs that aims to enhance UN support to national stakeholders on conflict prevention and sustaining peace. Between 2018 and 2020, the UK government provided £3.6 million of unearmarked funding to the Joint Programme.

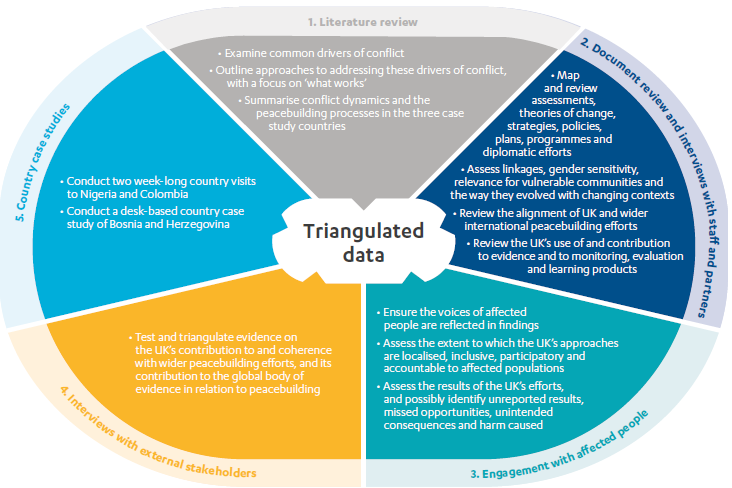

2.3 We assessed the relevance, coherence and effectiveness of ODA-financed work done within each of the case studies against the UK government’s strategies and objectives, and against the context in each country or region. We also considered the gender sensitivity of the UK government’s work, the way this work fulfilled its Women, Peace and Security commitments, and how UK efforts ensured a focus on and the active involvement of vulnerable communities. Where relevant, we assessed how the UK government considered environmental dimensions to conflict. We compared our findings with the perceptions of people affected by conflict, and ensured their voices were incorporated in our analysis and reflected in this report. Lastly, we assessed the way work in these case studies was monitored and evaluated, and the extent to which it had been informed by and had contributed to global and internal learning. To do this:

- We interviewed 161 people who worked for the UK government centrally and in the case study countries, like-minded governments, host government officials, implementing partners and academics. We also visited project sites in Colombia and Nigeria (but not in Bosnia and Herzegovina) and reviewed 663 documents that cover relevant assessments, strategies, policies, plans and programmes.

- We conducted interviews and focus group discussions with 231 conflict-affected people in two regions in Colombia (83 women and 57 men in Cauca and Meta) and Nigeria (37 women and 54 men in Maiduguri, Jere and Damboa, all in Borno State). The researchers were women. They visited the communities in which the respondents lived. The people they spoke with included indigenous people, Afro-Colombians and reincorporated former guerrillas in Colombia, and internally displaced people, former combatants, people from vigilante groups and people from the Christian minority in northeast Nigeria.

- We compared the UK’s peacebuilding approaches against evidence, as presented in literature, about what drives and perpetuates conflicts, what does and does not help to further peace, and what trade-offs typically have to be considered.

2.4 The five components of our methodology are summarised in Figure 1, and explained in full in our approach paper, which is available on the ICAI website. Methodological limitations are listed in Box 4.

Box 4: Limitations to the methodology

- Unless specified otherwise, our findings cover ODA spending from 2010 until mid-2022. However, the evidence base for the earlier years is weaker than for more recent years. We saw relatively little documentation produced before 2018, and relatively few respondents could help us understand the UK’s peacebuilding work that took place before then.

- Because the UK government does not use peacebuilding as an operational concept, the borders of what does and does not amount to peacebuilding work are unclear, and it is not possible to determine the proportion of the UK’s peacebuilding that we assessed. We only provide estimates for the UK’s overall spending on peacebuilding activities and focus our assessment on a detailed analysis of the four case studies.

- Because of the deliberate positive bias in our sample, our findings provide useful insights into ‘what works’ but cannot be assumed to be representative of the UK’s overall peacebuilding work.

- Our citizen engagement was not comprehensive. It was limited to people who had had exposure to projects that were funded or co-funded by the UK government, and does not give an indication of the proportion of conflict-affected people such projects reached. We did not engage with citizens in Bosnia and Herzegovina.

- Due to the nature of peacebuilding work, the causality between efforts and results is often uncertain. The review does not allocate successes or failures in peacebuilding efforts to a single actor or intervention but assesses, through triangulated evidence, plausible contributions to results.

- Because access to regions in active conflict is often highly constrained, we did not engage with people in some of the regions for which peacebuilding has been most important.

- We engaged with host government representatives, and to a limited extent with former combatants in Colombia, but not with other conflict parties in our case study countries. We only talked with representatives of countries that the UK sees as broadly sharing its peacebuilding objectives. Our data for Bosnia and Herzegovina rely on UK government documents, and insights gained through virtual interviews with representatives of the UK government and their implementing partners.

Figure 1: Our methodology

3. Background

3.1 The world is enduring the highest number of conflicts since the creation of the UN, with one quarter of the global population now living in conflict-affected countries. Within our review period, the number of active state-based conflicts increased from 31 in 2010 to 56 in 2020. According to the Global Peace Index, the level of global peacefulness deteriorated in this same period, and the situation in the 25 least peaceful countries deteriorated even more. Countries emerging from violent conflict have a high likelihood of relapsing into new conflict, and when they do it is almost always over the same or related issues. A formal end to a conflict does not mean that people are safe.

“The compañeros and compañeras who decided to leave [the conflict behind them] wanted […] to have a life, and what have they been? Assassinated, so each person who decided to believe in peace, what did they receive? Well, death.”

Mixed focus group discussion of rights defenders in Cauca, Colombia

“The problem we are facing is a youth problem. They fight a lot. […] They fight even during burial or funeral ceremonies, then also invite youths from the neighbouring community to assist them.”

Focus group discussion of young women (Woman, 18–25 years), Borno State, Nigeria

3.2 The nature of conflict is shifting. Environmental degradation and climate change are increasingly important drivers and amplifiers of conflict. Interlinked political, social, economic and military drivers of conflict have increasingly strong regional dimensions, and this makes them harder to resolve. The COVID-19 pandemic has placed critical limitations on peacebuilding efforts and governments have added to conflict risks by using the pandemic as a justification for strengthening surveillance and further restricting movements and liberties.

3.3 Conflict causes many types of harm. Conflict kills people. Between 2010 and 2017 the conflict death rate as a proportion of the world population nearly tripled. Conflict also forces people to move. The number of forcibly displaced people increased year on year throughout our review period, except for one year, and reached 100 million people in 2022. Conflict has immediate effects on economic activity and poverty: insecurity and infrastructure damage disrupt supply chains, violence and looting force people to flee and lose livelihoods, and the distortions of war economies facilitate corruption and the criminal exploitation of natural resources. In the longer term, these effects are compounded by disruptions in education, stunting, injuries and mental disorders.

3.4 The importance of building and maintaining peace is clear from the UN Charter, the opening line of which is: “We the peoples of the United Nations are determined to save succeeding generations from the scourge of war”. The UN’s understanding of what this means and requires has evolved over time. In 2016, the UN Security Council described peacebuilding as “an inherently political process aimed at preventing the outbreak, escalation, recurrence or continuation of conflict [that] encompasses a wide range of political, developmental, and human rights programmes and mechanisms”. The literature review that accompanies this report presents and categorises a range of other peacebuilding definitions and paradigms.

The UK government’s evolving approach to peacebuilding

3.5 The UK government’s interpretation of peacebuilding has also evolved. At the start of our review period (2010), the then Department for International Development (DFID) had landed on an approach to peacebuilding that “aims to establish positive peace” in which there is no structural violence and there are no structural impediments preventing people from reaching their full potential. This is more ambitious than achieving a ‘negative peace’ in the form of the mere absence of violent conflict. DFID’s approach consisted of three interrelated elements:

- Supporting supportive peace processes and agreements.

- Addressing causes and effects of conflicts.

- Building mechanisms to resolve conflict peacefully.

3.6 Soon thereafter, the UK government ceased to use peacebuilding as an operational term. However, its commitment to addressing the root causes of conflict and to consolidating peace remains. One of the priority actions of the 2021 Integrated review of security, defence, development and foreign policy is “to establish a more integrated approach to government work on conflict and instability, placing greater emphasis on addressing the drivers of conflict”. The May 2022 UK government’s strategy for international development reconfirms that “we must help countries escape cycles of conflict and violence”.

3.7 Ascertaining the level of UK investment in peacebuilding activities is not straightforward. A rough but low estimate provided by the UK government in 2022 declared spending on “civilian peacebuilding, conflict prevention and resolution” to range from a low of £92 million in 2007 to a high of £382 million in 2016, with a decline to £159 million in 2020. The UK’s peacebuilding work spans a range of areas. The programmes in our sample (see Annex 1 for an overview) cover a variety of objectives, including addressing environmental and other drivers of conflict, supporting peace negotiations, strengthening government and security institutions, promoting peaceful relations within and among communities, and working with like-minded donors to consolidate peacebuilding gains. Throughout the review period, key criteria for support were the UK’s perceived national interests and the UK’s perceived potential to contribute to peace. Other key criteria were the contributions the UK could make to gender equality and the Women, Peace and Security agenda and to ensuring that no one was left behind in the trajectory towards peace.

3.8 A portion of the UK’s peacebuilding work was channelled through the Conflict, Stability and Security Fund (CSSF), and implemented by the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office and its predecessors DFID and the Foreign and Commonwealth Office (FCO), and the Ministry of Defence. There were also programmes that were implemented directly by DFID, and in Colombia our sample included a programme that is implemented by the Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy.

3.9 Annex 2 lists documents that were published in our review period and that outline the UK government’s approach to peacebuilding. This approach evolved, and Box 5 lists the key shifts made in our review period. Some of these shifts were driven by changes in the nature of conflicts and the analysis of the wider international community. The UK incorporated a stronger regional focus into its work, for example, at the time when the landmark World Bank and UN publication Pathways for peace identified a trend towards the regionalisation of conflict. Another key shift is the acknowledgement of the role of (mis)information in conflict, and the understanding that the distinctions between peace and war, state and non-state violence, and the roles of the virtual and reality in conflict are increasingly blurred. A key internal shift was that the UK government gradually placed more importance on the need for its various parts to work as one, including official development assistance (ODA) and non-ODA spending. The CSSF served as a key vehicle for this.

Box 5: Shifts in the UK government’s approach to cross-government cooperation

Until the start of our review period, the guidance on the nature of cross-government cooperation followed a ‘comprehensive approach’ that focused on security and had its roots in military operations in Iraq and Afghanistan.

Around the start of our review period, the UK government moved to an ‘integrated approach’ rooted in DFID and the FCO. This approach seeks to bring different perspectives together (such as through the ‘Joint Analysis of Conflict and Stability’), and to ground collaborative work in conflict sensitivity and outcome-based thinking. This approach has continued to evolve. It has, for instance, moved from country-level to more regional thinking. It has also come to acknowledge that there are trade-offs between the immediate reduction of violence and the building of longer-term stability.

In 2018, the Cabinet Office introduced the ‘fusion doctrine’. This doctrine emphasises the need for resources to be commensurate with ambitions, and for strategic choices to be made on the basis of the UK’s national interest as well as on the basis of where the UK government could potentially make a catalytic contribution. The ‘fusion doctrine’ requires different parts of the UK to contribute to efforts that are not their core business if this maximises the UK government’s capabilities to achieve its overall goals.

The reductions from 2020 onwards in the UK aid budget meant that the diplomatic part of the UK’s effort gained in relative importance, but this has not changed the government’s emphasis on the need to work in a ‘whole-of-government’ manner.

4. Findings

4.1 Unless specified otherwise, findings apply to all three of our case study countries and country-specific examples illustrate wider points.

Relevance: How well has the UK government responded to different contexts in its peacebuilding approaches?

The UK government’s understanding of the conflicts it engages in is good, although limited by access constraints

4.2 Access to regions that are in active conflict is often highly constrained, and UK security risk appetite is low, which means that UK government staff often manage programmes they are unable to visit. The COVID-19 pandemic added to the constraints. In Nigeria, we found that the UK government’s travel rules for staff were risk-averse compared to the rules of almost all other international partners. Because of these constraints, it was not always possible to monitor conflict situations in real time, to engage directly with conflict-affected people, or to verify the quality of assessments.

4.3 As far as is possible under these circumstances, the UK government has a sound understanding of drivers of conflict and opportunities for peacebuilding. In part, this is a result of high levels of staff expertise and proactive learning. We come back to this in the section on effectiveness, see paragraphs 4.51 to 4.52 below. UK government staff deepen this understanding, and keep it current, through their active engagement with the UK’s sizeable in-country networks and an awareness of external research. Where this adds value, the UK conducts and commissions assessments, and contributes to the monitoring efforts of other stakeholders. In Colombia, the UK co-funds the missions of the UN and the Organisation of American States, both of which monitor elements of the implementation of the peace agreement. In Nigeria, the UK government works with national human rights institutions to establish local human rights monitoring committees. Some of the UK-funded assessments are sensitive and are not publicly available. Collectively, they form an evidence base that is large, contextually relevant and credible. In only a few cases did we see evidence of blind spots, and of somewhat duplicative assessments.

4.4 Many of the assessments focused on drivers and amplifiers of conflict, increasingly including climate change and environmental deterioration, and on impediments to peacebuilding, such as COVID-19 and disproportionate security force responses. Assessments often considered the multiplicity of mutually reinforcing drivers and amplifiers of conflict. The UK government also invests in conflict prediction capabilities that make use of quantitative data and machine learning (a form of artificial intelligence). Part of this work was paused when Russia’s invasion of Ukraine led to a reprioritisation of UK government activities. In Bosnia and Herzegovina, where there has been a fragile peace since late 1995, assessments focus on conflict risks and cover gender and inclusivity analysis, and the role of media and (dis)information in peacebuilding. Larger in-house studies, and specifically the UK’s Joint Analysis of Conflict and Stability (JACS) studies, evolved over the course of the review period. On the one hand, recent JACS assessments consider atrocity prevention options and are better designed to help make programme choices. On the other hand, recent JACS assessments engaged less extensively with the UK government’s civil society organisation (CSO) partners, which often have deeper insights into local realities than the UK government itself.

4.5 The nature of assessments evolved with shifting realities. Some such shifts are global. The regional dimensions of conflicts are gaining importance, as is the relationship between conflict and climate change and environmental degradation. Other shifts are specific to particular contexts. When the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) gave up their territorial control in Colombia, some forested regions were opened for legal and illegal commercial exploitation and deforestation accelerated. The UK government conducted research on criminal drivers of this acceleration and of links with peacebuilding efforts, and then designed a programme to respond to this new reality. The nature of assessments evolved with internal shifts as well. When reductions in the UK aid budget put the focus more on the diplomatic part of the UK’s peacebuilding efforts, assessments increasingly focused on the incentives that fuel and perpetuate conflict, and on opportunities for negotiation and mediation.

The UK government invests in understanding the needs and priorities of affected communities, but does not encourage accountability towards affected communities

4.6 In addition to national-level studies, the UK commissioned assessments on specific regions and specific groups within these regions. These assessments were generally conflict- and gender-sensitive, and intended to feed into projects that aimed to support ‘local peacebuilding’. Local peacebuilding is an increasingly influential approach to peacebuilding, meaning that the involvement of religious, community and women’s groups is a key factor in the design and implementation of projects. The assessments often related to the needs and priorities of particularly vulnerable groups, reflecting DFID’s emphasis on the principle of leaving no one behind. Such assessments worked well in contexts where vulnerable groups were somewhat organised, but less so in contexts where this was not the case.

“We [indigenous leaders] always […] go to the base and we consult with the community on what type of project is going to be managed, what type of project is viable in the indigenous territories because I cannot say let’s bring [for example] gold extraction, that we cannot allow. [Nobody can] say I have this project, you accept it, no, they first make the consultation, if it is possible, if it is viable or not, what kind of risks it will cause, if it will improve or worsen, then […] the authorities take the decision to convene an assembly and look at the line of needs of the tree of needs […] and then the assembly will determine if this project seems good to us.”

Mixed focus group discussion of people who were involved in projects of the Trust Fund for Sustainable Peace, Popayán, Colombia

“When they were building the shopping complex at the market area, they called us and asked our opinion on the project and I think our advice was considered.”

Men-only focus group discussion (25+ years), Borno State, Nigeria

“If we had been consulted at the beginning of the project they might not have used that kind of machine to pump water because the foot pump doesn’t produce water effectively and efficiently.”

Men-only focus group discussion (25+ years), Borno State, Nigeria

4.7 For more general assessments, including ones that took place for the immediate purpose of programme design, the UK and its implementing partners actively sought to include the voices of women and vulnerable groups. The identity of these vulnerable groups was context-dependent. They included unemployed people, former combatants and other people who have surrendered, forcibly displaced people, indigenous communities, marginalised ethnic groups, families of ‘disappeared persons’, and victims and survivors of sexual violence in conflict settings. The UK sometimes considered the specific needs of people who identify as lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer or intersex (LGBTQI+), where this did not conflict with local laws. In Colombia and Bosnia and Herzegovina, more than in Nigeria, some of the programming considered and aimed to address how different types of marginalisation intersected and compounded an individual’s vulnerability (such as, for instance, being a woman and a member of an ethnic minority). Notwithstanding the adoption in 2018, by the Department for International Development (DFID), of a strategy for disability-inclusive development, people living with a disability received relatively little attention.

4.8 The UK funded and encouraged engagement with vulnerable groups. However, it did not systematically require or monitor the use of mechanisms through which implementing partners ensure that conflict-affected communities are meaningfully involved in project decisions that directly impact their lives. Some UK government officials did not show awareness of the need for this accountability to conflict-affected communities. We saw several implementing partners that did ensure such accountability, and in our citizen engagement we learned about its positive effects. A man in Damboa, Nigeria, for example, told us: “There was a project by the UNDP at the market. The community discovered that the contractor was using substandard material. We reported [this] to [the local implementing partner] and they have stopped the work [of this contractor].” However, in many other cases meaningful involvement with affected communities dwindled after the assessment phase. Through our conversations with conflict-affected people, we learned that fully functioning accountability mechanisms were uncommon.

“They left without our knowledge. […] They are supposed to gather us and tell us that they are leaving. […] it just finished.”

Mixed focus group discussion of youth from the Christian minority in Borno State, Nigeria

“Once we were called to the District Head’s palace. We spent the entire day answering questions just like the way you are asking us questions, but apart from that, we have not seen anything.”

Women-only focus group discussion of farmers (25+ years), Borno State, Nigeria

“They impose projects […] like a project […] of 50 hens with their shed […]. This project is […] going to last until the [feed] concentrate runs out and after that the hens are going to get their necks turned and go to the sancocho [a Colombian stew] and that’s it. [Those who implement peacebuilding projects] spend millions on things that we don’t need.”

Mixed focus group discussion of former combatants, Miranda, Colombia

The UK government and its implementers use their contextualised understanding of conflicts as they develop and adapt theories of change, strategies and interventions

4.9 In the first half of this review period, theories of change were generally developed at programme level only, though not all programmes had them. They were often artificial constructs which retrofitted pre-existing projects that were not necessarily joined up, and they were not revisited once they had been finalised. In the second half of the review period, programme-level theories of change grew stronger. In addition, the UK government started to capture its approaches to conflict in credible theories of change at regional level (such as the one for the Western Balkans, which covers Bosnia and Herzegovina), national level (such as the one for Colombia), and sub-regional level (such as the one for the Lake Chad Basin). These theories of change are periodically revisited in light of evolving contexts. They outline change trajectories that cover official development assistance (ODA) and non-ODA work, and that demonstrate how political, developmental and sometimes military interventions could jointly contribute to peace and stability. These trajectories are generally plausible, although there are a few exceptions and blind spots. The expected speed of change is over-optimistic and underestimates the many obstacles that peace processes typically encounter – such as the prevalence of weapons in many post-conflict situations, and the power imbalance between indigenous people and the extractive and agro-industry sectors. We found an important example of a blind spot in the original theory of change for the Lake Chad Basin, which did not explicitly cover environmental degradation, even though this is a key driver of conflict in the region.

“The weapons, the weapons break everything, so this has stalled all the projects…”

Mixed focus group discussion of people who were involved in peace projects, Colombia

“They moved us here, […] they changed our territory, we live there by the river but we have to change [because the original land is valuable for commercial agriculture].”

Focus group discussion of displaced indigenous people, Colombia

4.10 Diplomatic efforts and programme choices generally align with the theories of change of which they are meant to be part. They also generally reflected the findings of assessments, where it was possible to translate these findings into useful action. This is most clearly the case where the UK government provides direct funding. Some of the work with host governments and multi-donor initiatives was less strongly rooted in assessments and therefore less likely to deliver good results. The UK was aware of this but was not always in the position to address the issue since it was only one of several stakeholders involved. In such cases, the UK government did not withdraw its support. Instead, it tried to influence decision-making, because the benefits of joint work with like-minded countries outweighed the drawback of co-funding some interventions that lack a strong evidence base. This is a reasonable assumption.

The UK government’s conflict endeavours are generally gender-sensitive and pay attention to its Women, Peace and Security commitments

4.11 Following the UN Security Council’s adoption of Resolution 1325 on Women, Peace and Security (WPS) in 2000, the UK was among the first to adopt a national action plan on WPS (see Box 6). The links between this and subsequent UK national action plans and actual practice are strong. For example, the 2018 national action plan argues that, in many post-conflict contexts, transitional justice mechanisms do not adequately include women and girls, and the UK funds work that is meant to ensure this will not happen in Colombia. Internally, UK government staff and documents are critical of shortcomings in the UK government’s global practice in this field, and point to the need to establish internal accountability mechanisms to ensure gender commitments are upheld. This internal criticism is in contrast to the views of the like-minded country partners we talked with, who all respect the UK’s WPS work and often see the UK government as a frontrunner in this field. The UK’s implementing partners see limitations in the form of short project timelines and lack of UK government attention to transformational change, but also say that the UK government actively supports WPS, and gender mainstreaming and inclusive approaches more widely, in all its peacebuilding programmes.

4.12 Nigeria is one of the UK’s WPS focus countries. The UK supported two iterations of Nigeria’s national action plan at federal level and in a few states. The UK’s work in Nigeria has focused on protection and prevention. Some of this was trailblazing: the UK government was among the first to support community reintegration of women and girls who had survived captivity, for example. Within these protection and prevention pillars, the issue of sexual violence received most of the attention.

4.13 Colombia never adopted a national action plan on WPS, but the situation is otherwise more enabling than it is in Nigeria. The gender gap is less wide41 and the 2016 peace agreement is widely seen as the most gender-sensitive peace agreement negotiated in recent times. The government of Colombia is supportive of women’s empowerment, and the wider donor community has a strong focus on gender equality in its various policies and programme efforts. Some of the citizens we engaged with confirmed that “women have become visible leading projects [and] many have participated in political spaces […] such as the [territorial] council. [Such participation] is no longer so stigmatised”. Colombia is data-rich in the field of gender equality and WPS, and instead of duplicating efforts the UK government uses external sources of information as it designs its contributions and monitors progress. Significant obstacles remain but, in this relatively enabling context, the UK’s WPS and wider gender equality work is able to consider how gender inequality intersects with LGBTQI+, indigenous and ethnic minority communities.

4.14 Starting in 2017, the UK government invested in its gender expertise in the Western Balkans. We saw evidence of gender sensitivity across the Bosnia and Herzegovina portfolio. The most important WPS assessments are appropriately related to the priorities set by the country’s current (2018–22) national action plan, which prioritises the increased participation of women in military forces, the police and peace missions, including in decision-making positions.

4.15 Overall, the UK government was relatively gender-sensitive at the start of the review period, and then invested in gender and WPS expertise. This further improved its gender sensitivity, and its capacity for gender-responsive and gender-transformative programming. The Ministry of Defence started at a lower base than other parts of the government, but also became more gender sensitive over the course of the review period. It prominently covered WPS commitments in strategic documents, and played a leading role in Bosnia and Herzegovina. The UK government generally ensured that assessments included or specifically focused on WPS and gender equality, and actively followed up on its WPS commitments. The UK also monitored, and was content with, the gender sensitivity of the UN Peacebuilding Fund it contributed to, and the proportion of projects that had gender equality as a principal objective (38% in 2018).

The government responded swiftly to challenges posed by COVID-19

4.16 The COVID-19 pandemic affected both conflict dynamics and peacebuilding activities. In all case study countries and around the world, access to goods and services in regions in conflict was further impeded, gender-based violence spiked, and WPS and wider peacebuilding programmes slowed down or were put on hold. Where peacebuilding efforts moved to virtual platforms, those who could not get online lost agency. This ‘digital divide’ between those who could and those who could not easily access and use modern information technology disproportionately disadvantages women and girls, elderly people, and rural and conflict-affected regions. In Colombia, site visits from the government and international organisations were no longer possible, and this widened the space for armed groups to take control of some rural regions. In Nigeria, it added to distrust in the Nigerian government, and people feared the virus itself less than the impact of the security forces’ inhumane containment measures and extortion of traders supplying essential goods.

Box 6: The global WPS agenda and the UK’s commitments

The global Women, Peace and Security (WPS) agenda aims to promote and fulfil women’s human rights and achieve gender equality as part of efforts to build more peaceful and stable societies. It has been driven by the UN Security Council’s Resolution 1325, a resolution adopted in 2000, which calls for increased representation of women at all decision-making levels for the prevention, management and resolution of conflict. The global WPS agenda has four pillars:

- Prevention of conflict and all forms of violence against women and girls in conflict and post-conflict situations.

- Participation. Women participate equally with men and gender equality is promoted in peace and security decision-making processes at all levels.

- Protection. Women’s and girls’ rights are protected and promoted.

- Relief and recovery. Women’s and girls’ specific relief needs are met and women’s capacities to act as agents in relief and recovery are reinforced in conflict and post-conflict situations.

The UK’s commitment to the WPS agenda, and its approach to implementation, are outlined in a national action plan (NAP). The current NAP (2018–22), the UK’s fourth, is jointly owned by the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office and the Ministry of Defence and is the UK’s highest-level strategy on gender and conflict. It has seven ‘strategic outcomes’, which are linked to the four pillars of the global WPS agenda. While UK commitments apply to all relevant contexts, the NAP has nine focus countries: Afghanistan, Burma, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Iraq, Libya, Nigeria, Somalia, South Sudan and Syria.

UK NAP strategic outcomes

- Decision-making processes: An increase in women’s meaningful and representative participation in decision making processes, including conflict prevention and peacebuilding at community and national levels.

- Peacekeeping: A gender perspective is consistently applied in the setting and implementation of international standards and mandates for peace operations.

- Gender-based violence: An increase in the number and scale of interventions that integrate effective measures to prevent and respond to gender-based violence (GBV), particularly violence against women and girls, which is the most prevalent form of GBV.

- Humanitarian response: Women’s and girls’ needs are more effectively met by humanitarian actors and interventions through needs-based responses that promote meaningful participation and leadership.

- Security and justice: Security and justice actors are increasingly accountable to women and girls, and responsive to their rights and needs.

- Preventing and countering violent extremism: Ensure the participation and leadership of women in developing strategies to prevent and counter violent extremism.

- UK capabilities: The UK government continues to strengthen its capability, processes and leadership to deliver against WPS commitments.

4.18 In the field of peacebuilding in our case study countries, the UK government’s response to the COVID-19 crisis was swift. When the pandemic restricted movement in Colombia, the UK embassy immediately contacted its implementing partners to reassure them that the previously agreed funding could be repurposed to remain useful in this suddenly changed context. In Bosnia and Herzegovina, ongoing WPS work with the military quickly turned virtual, and the search for missing persons resumed after a break of only a few months. In Nigeria, some activities were put on hold, but the UK government was quick to commission research on the potential impact of measures to prevent the spread of COVID-19 on livelihoods and to help reduce the risks of such measures exacerbating conflict and instability. The UK government embraced the UN Peacebuilding Fund’s ambition to expand its work in response to the challenges to peace and stability caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, seeing this expansion as “a core part of helping […] to Build Back Better” after COVID-19.

Conclusions on relevance

4.19 Where access is possible, the UK government combines its considerable expertise with contextual assessments to develop theories of change, approaches and programmes, and to modify them to ensure continued relevance in shifting contexts and during pandemic restrictions. Backed by strategic guidance, these assessments include significant engagement with women, youth and, depending on context, a range of vulnerable communities. Assessments and designs are generally gender-sensitive and intended to empower, and they prominently feature the UK’s WPS commitments.

4.20 The UK government does not require or systematically encourage implementing partners to ensure that conflict-affected communities are meaningfully and continuously involved in project decisions that directly impact their lives. We saw implementing partners that have appropriate systems and mechanisms in place, and we saw their benefits; but in some projects meaningful community involvement dwindled after initial consultations. We award a green-amber score for the relevance of the UK’s peacebuilding approach in our four case studies, and note the importance of strengthening accountability to conflict-affected communities.

Coherence: How internally and externally coherent are the UK’s peacebuilding approaches?

Government officials understand the UK government’s approach to peacebuilding work and adjust to shifts in policy direction

4.21 Section 3 of this review outlines the UK commitments that remained firm throughout the review period, and the ways in which the UK government’s approaches to peacebuilding evolved. While the UK government’s peacebuilding work has always had programmatic, diplomatic and military dimensions, government guidance has increasingly emphasised the importance of approaches that, where beneficial, combine these efforts, and combine ODA and non-ODA contributions. The 2020 merger of the Foreign and Commonwealth Office (FCO) and DFID and the significant reductions of the UK aid budget in 2020 and 2021 have not changed the preference for joined-up action but have led to stronger emphasis on diplomatic influencing. This stronger emphasis is aligned with the conclusion of an internal review on the UK government’s role in international peace-making since 1989, which is that “the UK has a broad range of capabilities it can bring to bear on a conflict-resolution process, [and] the consistently most important have been traditional diplomatic skills and tradecraft including long-term relationships, political-economy analysis, deep background knowledge, and coalition-building”.

4.22 The various shifts in the UK’s approaches were explained in successive strategy and policy documents, and during staff meetings and through presentations. When we asked longer-serving officials to list the long-standing fields of commitments and to explain the differences between approaches such as the comprehensive approach, the integrated approach and the ‘fusion doctrine’ (see Box 5), they could generally do so. Their explanations aligned with what we learned from documentation. Cooperation between programmatic and diplomatic efforts have long been standard in the UK’s contributions to UN peacebuilding work.

4.23 The UK’s contributions to UN peacebuilding work consist of diplomatic efforts, funding and the provision of technical support. This technical support is partly in the form of secondments. This aligns with the shifts towards an integrated approach taking place at the beginning of our review period, which emphasised putting “the right people in the right places”. However, unlike some other like-minded governments, such as Germany, the UK does not have a mechanism in place to create synergies among the staff it seconds to UN posts.

4.24 The funding, diplomatic efforts and technical support reinforce each other, and had already done so before the start of our review period. In our case studies, we saw two types of integrated ways of working.

- The UK government combined financial contributions, secondments and influence in relation to the UN Peacebuilding Fund and the Joint Programme between the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) and the UN Department of Political and Peacebuilding Affairs. Without its position as a significant donor to the fund and the programme, the UK would not have been able to play the influencing role described below in the Effectiveness section (see paragraphs 4.88 to 4.90 below) of this review. This influencing role helped ensure that the Peacebuilding Fund and Joint Programme took shape in a manner aligned with UK priorities.

- The UK government’s in-country programmes and diplomatic efforts influenced the UK’s work in the UN Security Council. This includes the UK’s penholder role for the peace process in Colombia and for the Lake Chad Basin, but also transcends country-specific work. For example, the UK government’s in-country experience strengthened its contributions to Security Council statements on demobilised child soldiers and WPS.

Close cross-government cooperation in the field of peacebuilding was operationalised in each of our case study countries

4.25 Within the UK’s programming efforts, we saw evidence of good cooperation between, and complementarity of, different UK funding mechanisms. In Colombia, the Conflict, Stability and Security Fund (CSSF) and the Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy applied their respective fields of expertise and funding modalities in a joint conflict-sensitive endeavour that aims to reduce the risk of conflict while also reducing deforestation levels. In Nigeria, various programme efforts came together in an integrated delivery plan that was issue-based rather than sectoral, and projects that did not fit within this plan were not renewed. In Bosnia and Herzegovina, all funding is channelled through the CSSF, which is a cross-departmental fund, and the country’s portfolio fits well within the Western Balkans strategy. We did not see initiatives working towards contradictory aims in any of our case study countries. We did, however, see some evidence of a disconnect between in-country programmes and some of the centrally managed peacebuilding efforts, and coordination across implementing partners working in the same regions was not always adequate.

4.26 In each of our country case studies, the relevant parts of the UK embassy or high commission had at least broad knowledge of one another’s portfolio of work. We saw examples of interrelated programmatic and diplomatic efforts. Groups regularly provide technical support to one another. The benefits flowed both ways: we saw evidence of programmes capitalising on diplomatic milestones, and of diplomatic access being facilitated by programme work. We saw examples of cross-fertilisation in the early years of our review period, even though implementing partners were not yet encouraged to ‘think politically’. Cross-fertilisation gained momentum in the second half of the review period. In Nigeria, this joined-up approach was facilitated by the co-location of the former DFID and FCO. In all country case studies, it was also facilitated by the centralisation of decision-making in the hands of the ambassador or high commissioner who led the in-country efforts. We saw some evidence suggesting that the merger between DFID and FCO has helped facilitate the interplay between programming and diplomatic efforts in Nigeria.