The UK’s approaches to peacebuilding

Purpose, scope and rationale

The number of active conflicts is higher than at any point since 1945, and many conflicts are persistent. As noted in the September 2020 business case of the UK’s Conflict Prevention and Peacebuilding Programme: “60% of conflicts that ended in the early 2000s have relapsed into violence within five years. We are witnessing more protracted humanitarian crises and famine.” As conflicts continue to pose a significant constraint on poverty reduction and sustainable development around the world, progress against Sustainable Development Goal 16 (“Promote just, peaceful and inclusive societies”) remains essential. In this context, UK aid has made sustained diplomatic and programming investments to address drivers of conflict and help build peace in fragile and conflict-affected countries and regions.

Using a case study approach, the purpose of this review is to examine how relevant, coherent and effective this cross-government investment has been. In addition, for each case study, we will consider the extent to which the UN’s Women, Peace and Security agenda and promoting global gender equality is pursued, as these are key UK government priorities. We will also consider how well the UK engages with those expected to benefit from its programmes, and how the UK incorporates their needs and priorities into its programme designs.

We have selected four case studies. Three of them cover the UK’s peacebuilding efforts in a conflict-affected state. The fourth case study is of the UK’s Conflict Prevention and Peacebuilding Programme and the UK’s multilateral work that preceded and informed this programme. Together, the four case studies encompass a wide and diverse range of programmes and mechanisms. From these case studies, we seek to identify lessons that can be applied more broadly.

The review’s use of the term ‘peacebuilding’ will cover longstanding UK aid and diplomatic efforts to address drivers of conflict, with the aim of helping to prevent and resolve conflict and consolidate post-conflict peace. While the UK government does not use ‘peacebuilding’ as an operational concept, it declared the intention to continue its efforts in this field in its 2021 Integrated review of security, defence, development and foreign policy, which states that one of its “priority actions will be to establish a more integrated approach to government work on conflict and instability, placing greater emphasis on addressing the drivers of conflict”.

To ensure relevance, the scope of this review has been determined by what the UK government identified as its most relevant peacebuilding work in the period from 2010 until 2022. Counterterrorism and other security-related operations and strategies are out of scope, and so is the broader development impact of the peacebuilding efforts we assess. So as not to overlap with ICAI’s 2022 review on the UK’s approach to safeguarding in the humanitarian sector, this review will not focus on safeguarding.

Background

As part of its commitment to transparency, the UK government annually reports against the categories of aid spending agreed by the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development’s Development Assistance Committee (OECD DAC). One of the spending categories is ‘civilian peacebuilding, conflict prevention and resolution’. Under this category and between 2007 and 2019, the UK government reported an annual expenditure ranging from £87 million (in 2007) to £361 million (in 2016). It reported a sizeable increase from 2014 to 2016 (from £128 million to £361 million), followed by a sizeable reduction from 2017 to 2019 (from £307 million to £195 million).

While the UK government’s external annual aid reporting is bound by DAC categories, its internal categorisation of spending is not. Internally, ‘peacebuilding’ is not used as a spending category. The UK has many programmes that relate to peacebuilding, but the boundaries are not clear and it is not possible to count these programmes or provide a neat presentation of their geographical spread or delivery channels. Therefore, the rationale for including or excluding funding streams in the UK’s DAC category of civilian peacebuilding, conflict prevention and resolution is not clear-cut. This means that the UK’s reported spending in this category is at best a rough approximation of the UK’s efforts in relation to drivers of conflict. Because it does not have peacebuilding as a distinct operational concept, the UK government does not have an explicit peacebuilding strategy, policy commitments or results targets.

Although the UK government does not describe its work as ‘peacebuilding’, we chose the word as an umbrella term that is widely used and readily accessible to the public. Our definition covers the wide range of UK efforts which seek to address drivers of conflict with the aim of helping to prevent and resolve conflict and consolidate post-conflict peace. It is comparable to the UN definition, which describes peacebuilding as “an inherently political process aimed at preventing the outbreak, escalation, recurrence or continuation of conflict [that] encompasses a wide range of political, developmental, and human rights programmes and mechanisms”.

Review questions

The review is built around the evaluation criteria of relevance, coherence and effectiveness. Our review questions and sub-questions under each of these criteria are set out in Table 1.

Table 1: Our review questions

| Review criteria and questions | Sub-questions |

|---|---|

| 1. Relevance: How well has the UK government responded to different contexts in its peacebuilding approaches? | • How well does the UK assess the drivers of conflict and opportunities for peacebuilding in particular contexts and develop plausible theories of change for its interventions? • To what extent do the UK’s approaches to peacebuilding reflect the needs and priorities of vulnerable communities? • How well does the UK meet its commitments on Women, Peace and Security? |

| 2. Coherence: How internally and externally coherent are the UK’s peacebuilding approaches? | • How well have UK departments, funds and agencies worked, and worked together, to deliver peacebuilding outcomes? • How well does the UK align its programming and diplomatic efforts towards peacebuilding? • Are the UK’s approaches to peacebuilding coherent with the efforts of the host government, and of other funders and agencies? |

| 3. Effectiveness: How well has the UK contributed to peacebuilding objectives in areas in which it operates? | • To what extent is the UK contributing to a resilient peace in the areas in which it operates? • How well does the UK measure and evaluate its contribution to peacebuilding? • How well is UK aid contributing to and learning from evidence, and adapting its approaches? |

Methodology

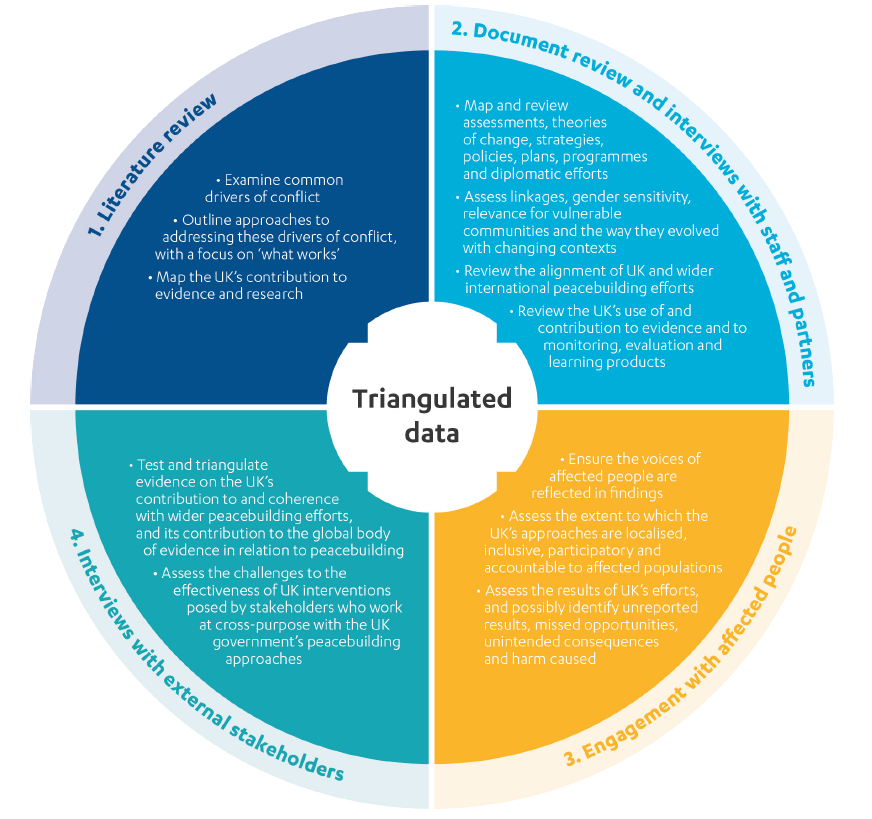

To gather, compile and triangulate evidence, this review will include the following:

- a literature review

- a review of UK government documents and interviews with UK government staff and implementing partners

- engagement with affected people

- interviews with external stakeholders.

Most of this work will be done in the context of four distinct case studies.

Figure 1: Methodology wheel

The literature review will outline common drivers of conflict. It will provide insight into approaches to addressing these drivers, in the case study countries and elsewhere. It will also look at the trade-offs and dilemmas that relatively successful approaches may face. This will help us address the relevance of UK efforts, as it will enable us to compare the UK’s assessments and approaches with what matters and ‘what works’. The literature review will also help us understand what trade-offs and dilemmas the UK may be facing. Its starting point will be research commissioned by the UK government. As such it will also inform our response to sub-question 3c in Table 1, on how the UK contributes to and learns from evidence. The literature review will be published alongside the main review.

A review of UK government documents and interviews with UK government staff and implementing partners will inform all three of our review questions. Documents include assessments as well as strategy, policy and programme documentation. Interviews will be conducted at central level, in-country (through country visits), and remotely (in the context of desk studies). The combination of the document review and interviews serves the purpose of deepening and triangulating our findings.

For the relevance and coherence questions, we will use the document review and interviews to map the existence, methods, coverage and quality of assessments, and their links with the theories of change, approaches and plans that underpin relevant UK programming. The document review and interviews will also help us assess:

- the clarity and coherence of UK programming and diplomatic efforts towards peacebuilding

- the evolution of approaches and how this relates to changing contexts

- how UK investments relate to wider international peacebuilding efforts

- the extent to which the UK’s peacebuilding work is gender-sensitive and promotes the Women, Peace and Security agenda

- how UK efforts ensure a focus on and the active involvement of vulnerable communities

- how the UK deals with trade-offs and dilemmas.

For the effectiveness question, the document review and interviews will help us assess the UK’s use of and contribution to evidence and to monitoring, evaluation and learning products. The document review and interviews will also be used to triangulate evidence we may find in relation to unreported results, missed opportunities, unintended consequences and harm caused.

Engagement with affected people will ensure that the voices of people in countries affected by conflict are incorporated into the analysis. This engagement will be undertaken by national research partners in Nigeria and Colombia. Their research will be governed by the research ethics guidance for ICAI reviews. This guidance builds on the research ethics codes of the Economic and Social Research Council and includes a rigorous safeguarding and ethics protocol that is based on the objectives of doing no harm, doing some good, and treating people with respect.

This component will make use of a mix of qualitative methods, such as focus group discussions, key informant interviews, observations of behaviour and possibly, where other options do not exist, phone interviews. Collectively, these methods of engagement will help us address our relevance questions by giving us insight into the extent to which the UK’s efforts are localised, inclusive, participatory and accountable to affected populations in all stages of the development and operationalisation of the UK’s approaches. Engaging affected people will also help us address our effectiveness question, by deepening our understanding of the results of UK efforts and, possibly, by alerting us to unreported results, missed opportunities or harm that UK efforts may have caused.

Interviews with external stakeholders, such as academics, state actors and non-governmental organisations that are not implementing partners, will help us test the UK’s contribution to and coherence with wider peacebuilding efforts, and its contribution to the global body of evidence in relation to peacebuilding. The external perspective of the interviewees will help us triangulate findings for our effectiveness question, and for sub-questions 1b, 1c and 2b in Table 1. If it is feasible to conduct interviews with stakeholders who may – consciously or otherwise – be working at cross-purpose with the UK government’s peacebuilding approaches, these interviews will help us understand the challenges that UK peacebuilding work is facing.

Most of this work will be conducted in the context of four distinct case studies. We will review relevant UK aid spending in Nigeria, Colombia and Bosnia and Herzegovina, and spending on the UK’s multilateral effort that culminated in the UK’s Conflict Prevention and Peacebuilding Programme. These case studies include bilateral and multilateral spending since 2010, as well as national partnerships and diplomatic efforts. In addition to the methods outlined above, the visits to Nigeria and Colombia may also include observations of meetings and the hands-on work of implementing partners. These visits may also lead to further document review and will be closely coordinated with our national partners that lead on our engagement with affected people.

Sampling approach

Because the UK’s multilateral contributions are a substantial part of its aid spending, one of our case studies is the Conflict Prevention and Peacebuilding Programme, and the UK’s multilateral engagement that led to the launch of this programme.

In addition, we will conduct two country visits and one country desk study. We asked the government to use three criteria to compile a list of relevant countries. The first criterion is that UK contributions to peacebuilding should stretch back to at least 2010, in the assumption that progress towards resilient peace requires a long-term endeavour. The second criterion is that UK engagement should be diverse and sizeable (even if definitional challenges mean that the government may be unable to tell exactly how diverse and sizeable the engagement has been). This ensures that the review is able to assess cross-government coherence across activities. The third criterion is that the UK government should judge that its peacebuilding efforts have been at least partially successful. This criterion acknowledges the challenging nature of peacebuilding. There exists a vast literature on what causes and perpetuates conflict, while the understanding of ‘what works’ to reduce conflict and fragility is weaker. The selection of cases judged to have had some success is based on the premise that there is more to learn from approaches that have worked well than from those that have failed.

On the basis of these criteria, the UK government presented us with a list of 15 countries and regions. We selected three countries from this list, using a further three criteria that needed to be met in at least two of the three countries:

- an active role by the United Nations Peacebuilding Fund to which the UK contributes

- a focus on Women, Peace and Security

- a focus on peacebuilding with an environmental dimension.

The application of these criteria led to the initial selection of Nigeria, Colombia and Myanmar as our case studies. Following further information from the UK government on potential risks to partners, we later replaced Myanmar with Bosnia and Herzegovina to avoid the risk of harm. We will visit and engage with affected people in Nigeria and Colombia. Our assessment of the UK’s efforts in Bosnia and Herzegovina will be desk-based.

Limitations to the methodology

Scope: The borders of what does and does not qualify as peacebuilding are subject to interpretation. This is due to the combination of, on the one hand, the UK government not using ‘peacebuilding’ as an operational concept or programme category, and, on the other, the broad nature of the definition of peacebuilding that ICAI will use in this review. To ensure that we cover relevant UK activities, we will interpret the concept of peacebuilding in a context-specific manner in each of our case studies.

Counterterrorism and other security-related operations and strategies are out of the scope of this review, and so is the broader development impact of the peacebuilding efforts we assess. However, affected communities and implementing partners are unlikely to make clear distinctions between the UK’s activities and impact as a contributor to peacebuilding, a development actor and a counterterrorism actor. An assessment of programmatic and diplomatic coherence of work in the field of peacebuilding may not be possible without considering these other areas.

Results data: In assessing the effectiveness of UK peacebuilding efforts, we will rely primarily on data generated by the UK government and its implementing partners. We will manage the resulting risk of bias by triangulating in a number of ways. We will assess the quality of data, including by checking source data coherence on a sample basis. We will interview counterparts and other development partners on programme effectiveness, and we will consult implementing partners at the working level on how implementation challenges have been addressed. We will also engage with affected people. In combination, these assessment activities will enable us to come to conclusions about the accuracy of the UK’s data. However, in the event that the data are inaccurate, we will have limited capacity to reach independent conclusions about programme effectiveness.

Risk management

Table 2: Risk management

| Risk | Mitigation and management actions |

|---|---|

| UK government capacity limitations, security concerns or COVID-19 restrictions prevent the review team, including local partner teams, from travelling and meeting affected people | • We will use virtual meetings where needed. • We will work with local partners to engage with affected people. • In the event that risks are considered too great to undertake planned travel, the safety of the review team, including local partner teams, will always take priority. In such cases we may change our selection of case study countries, or the regional choices within these countries, to ensure that timely, relevant visits and engagement with affected people do take place. |

| We do not have full and timely access to data | • Some data needed for this review are classified, and the review team may not be granted full and timely access to such data. To manage this risk, all team members have been security-cleared and the ICAI secretariat will liaise with FCDO to agree on protocols regarding access to and use of restricted information. We will respect the UK government security guidance. |

| Implementing partners or external stakeholders are unwilling to make time available for interviews and/or to share documents | • We may shift our focus to other stakeholders, and note the resultant limitations in our final report. |

Quality assurance

The review will be carried out under the guidance of the ICAI chief commissioner, Dr Tamsyn Barton, with support from the ICAI secretariat. Both the approach paper and the final report will be subject to quality assurance by the ICAI service provider consortium, and will be peer-reviewed by Professor Jonathan Fisher, head of the International Development Department at the University of Birmingham and a leading international expert on peacebuilding.

Timing and deliverables

The review will take place over a ten-month period.

Table 3: Estimated timing and deliverables

| Phase | Timing and deliverables |

|---|---|

| Inception | Approach paper: spring 2022 |

| Data collection | Country visits and desk-based reviews: spring and summer 2022 Evidence pack: summer 2022 Emerging findings presentation: summer 2022 |

| Reporting | Final report: winter 2022 |