The UK’s changing approach to water, sanitation and hygiene

Introduction

The UK’s aid programming on water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH) has undergone major changes since it was last reviewed by the Independent Commission for Aid Impact (ICAI) in 2016. At that time, the UK had a substantial portfolio of WASH programmes, designed to deliver on some ambitious global targets. In recent years, however, UK bilateral aid for WASH has fallen steeply, raising questions about the UK’s commitment to the sector – particularly given the importance of WASH in the global response to the COVID-19 pandemic.

This information note provides an account of the evolution of the UK’s WASH portfolio and approach since our 2016 review, including its response to the pandemic. ICAI information notes examine topics of public interest; they are not evaluative, but point to areas that merit further investigation, either by ICAI itself or other scrutiny bodies. The information in this note draws on interviews with officials from the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO), including those responsible for coordinating significant WASH programmes in Ethiopia and Zimbabwe, a review of FCDO programme documents, and consultations with partners in the sector, including multilateral agencies, non-governmental organisations, research institutes and private sector suppliers.

The UK’s water, sanitation and hygiene results

Over the past decade, the former Department for International Development (DFID) set itself – and achieved – ambitious global targets for its water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH) programming. In the period from 2011 to 2015, it pledged to provide 60 million people with access to clean water, basic sanitation or hygiene promotion, and achieved the target, reaching 62.9 million people. DFID made the same pledge for the 2015-2020 period and reached 62.6 million people.

These results were part of the UK’s contribution to WASH targets set out in the Millennium Development Goals and, from 2015, the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), which aim for universal and equitable WASH access for all by 2030 (see Box 1). The targets also reflected UK government manifesto commitments and a desire for quantifiable and clearly attributable results from an expanding UK aid budget.

To deliver on these targets, the UK developed substantial bilateral WASH programmes in a number of countries, including the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Ethiopia, Malawi, Mozambique, Nigeria, Tanzania, Zambia and Zimbabwe. It also entered into a £57.3 million partnership with UNICEF, the United Nations Children’s Fund, to provide sustainable WASH services to 3.8 million people in ten countries, through the Sanitation, Water and Hygiene for the Rural Poor programme (2017-2022).

Box 1: Progress towards global WASH goals

Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 6 aims to ensure availability and sustainable management of water and sanitation for all. Its targets include universal and equitable access to safe and affordable drinking water, adequate sanitation and hygiene, improving water quality and water-use efficiency, and developing integrated water resources management.

So far, progress is lagging well behind these ambitions. Recent assessments suggest that the rate of progress needs to increase fourfold if the 2030 targets are to be met, and even more in fragile and conflict- affected states. As well as the financing gap, SDG 6 is threatened by unsustainable water usage, pollution of water sources and the accelerating impacts of climate change, with more frequent and more severe droughts and flooding undermining sustainable WASH services.

Figure 1: Progress towards Sustainable Development Goals Water, Sanitation and Hygiene targets by 2030 (by percentage of global population with access)

Data source: Progress on household drinking water, sanitation and hygiene 2000‒2020: Five years into the SDGs, World Health Organisation/ UNICEF Joint Monitoring Programme, 2021, p. 7, link.

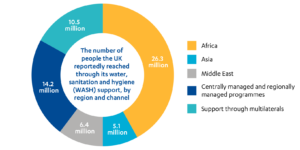

Emergency WASH support is part of UK humanitarian operations, including in conflict-affected countries such as South Sudan and to refugee populations in the Middle East. These humanitarian operations contributed results towards the global target, as did UK core contributions to multilateral partners

(see Figure 2).

Figure 2: The UK’s Water, Sanitation and Hygiene results between 2015 and 2020

Source: DFID results estimates 2015-2020: Sector report, Department for International Development, 2021, p. 47, link.

In our 2016 review, which focused on the 2011-2015 period, we found that the reported results were credible. However, we raised concerns as to whether the programmes were in fact delivering “sustainable access” to WASH, as pledged. We found that suppliers of UK WASH programmes were not strongly incentivised to focus on sustainability and the programmes did not monitor results beyond their completion dates.

A declining water, sanitation and hygiene budget since 2018, but with new programming in the pipeline

As the programmes and activities that supported the delivery of the UK’s targets came to an end, many were not renewed. Water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH) programmes have continued in a few countries, including Ethiopia and Mozambique. There are continuing WASH components within health programmes, and there are plans to increase the use of UK International Climate Finance to support water security and climate-resilient WASH services programming.

However, the overall result has been a decline in bilateral WASH expenditure. UK aid for WASH peaked in 2018, at £206.5 million. As a proportion of UK bilateral aid, it reached 2.7% in 2014 and has declined since then (see Figure 3). The reduction in expenditure pre-dated the COVID-19 pandemic, and has continued as a result of reductions in the UK aid budget in 2020 and 2021. The effects of these reductions on programming are still emerging. The Foreign, Commonwealth Development Office (FCDO) estimates that its WASH expenditure was around £70 million in 2021, although the final figure will not be known until Statistics in International Development is published in Autumn 2022. This suggests a fall of two-thirds from the 2018 peak.

Figure 3: UK bilateral aid for Water, Sanitation and Hygiene 2009 – 2021

Source: For 2009-2020, Statistics in International Development (SID), DFID/FCDO. The 2021 figure is FCDO’s management information projection of bilateral WASH spend for 2021 as of 7 February 2022. This is not a SID statistic; an official figure will be released with the final 2021 SID in autumn 2022.

The sustained downward trend is marked, as showing in Figure 3. Some FCDO officials suggested that it reflected an ambivalence towards the sector at ministerial and senior management levels, and a desire to consolidate UK bilateral aid into fewer sectors. Within the human development area, health and education programmes have traditionally been seen as a higher priority for UK aid.

FCDO’s management of the 2020 and 2021 budget reductions has been reviewed in other ICAI reports. Across the WASH portfolio, many programmes were affected: some faced budget reductions or delays, while others were brought to an early end. The pipeline of new programmes was also frozen. There were reductions and cancellations of grants to non-governmental organisations through central funds such as UK Aid Connect and UK Aid Direct, as well as cutbacks to WASH-related research programmes through instruments such as the Global Challenges Research Fund.

According to implementing partners consulted for this note, the challenge was not just the loss of funds, but the short notice. As ICAI has described in a previous information note, government officials were not permitted to communicate planned budget reductions to suppliers until the whole package had been announced, which reduced the time available to manage them in an orderly way.7 Many partners informed us that the abrupt nature of the reductions had damaged their relationships with national partners and communities. Some also reported loss of experienced staff and additional financial losses, such as ‘matched funds’ from other sources and sunk costs in preparatory work.

In some cases, the budget reductions may have undermined the sustainability of past assistance. For example, FCDO’s support to UNICEF, the United Nations Children’s Fund, under the Sanitation, Water and Hygiene for the Rural Poor programme saw a £12.1 million budget reduction while the end date of the support was brought forward by nine months. As a result, activities intended to increase the sustainability of past investments were cancelled. UNICEF and other partners nonetheless noted that FCDO staff had worked closely with them to try to mitigate these risks.

FCDO informs us that new WASH programmes are in preparation, as part of an ongoing business planning round launched under the current three-year spending review.

A new strategic direction

In 2018, the UK announced a new approach to water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH) programming. The change was motivated by concerns that past investments in basic WASH facilities in poor rural communities were not sustainable – a concern that had been raised in the Independent Commission for Aid Impact’s (ICAI’s) 2016 report. Following an ICAI recommendation, a review of sustainability across the portfolio was commissioned, covering nine WASH programmes in seven countries. Reporting in 2021, it found that just over half of the water points constructed before 2018 with UK funding still provided reliable access to water, and a further one-third demonstrated limited functionality. Only two-thirds of household latrines were still fully or partly functional, with many showing cleanliness and hygiene problems. Among communities originally certified as ‘open defecation free’ (defined as all households using a sanitation facility rather than defecating in the open), a quarter had relapsed.

There were also concerns about the contribution of WASH programmes across the sector to health outcomes. One of the reasons why the UK and other donors invest in WASH facilities is to prevent waterborne diseases such as diarrhoea, which are a major cause of sickness and infant mortality. However, a group of impact evaluations conducted across the sector which finished in 2018 – including a UK-funded study in Zimbabwe – found that basic WASH interventions had no measurable impact on child stunting (impaired growth and development, which can be a result of frequent illness) and mixed impacts on diarrhoea prevalence. The findings suggested that the provision of basic WASH services alone may not be sufficient to improve health outcomes, although the more holistic, community-level WASH interventions used in many UK programmes were not tested. The trials challenged the sector to move towards a more comprehensive and therefore costly package of facilities and services, such as household toilets and campaigns to change community sanitation and hygiene practices.

The UK’s new approach involved a shift of focus towards supporting national WASH systems by building institutions, raising service standards and mobilising other sources of finance, including by encouraging communities to pay for services. It included a stronger emphasis on WASH in urban settings and on water as a productive resource for farming and industry. It stressed the need to draw on UK research to identify innovative solutions to WASH provision, and to focus more on resilience in the face of climate change.

This change in direction is not yet fully implemented, as the launch of new programmes has been delayed by budget reductions. Nonetheless, it is visible in recent and forthcoming programme designs. For example, a new programme (yet to be approved) is being prepared to strengthen the delivery of climate-resilient WASH services in ten water-scarce countries. The draft concept note states:

“We are moving away from delivering basic water and sanitation facilities at community level. Instead, we will make full use of UK expertise, influence and resources to transform the delivery of inclusive, sustainable and climate resilient water supply and sanitation services at scale. UK funds will benefit whole populations rather than individual communities.”

In December 2021, the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO) published an approach paper on Ending the Preventable Deaths of Mothers, Babies and Children by 2030, which supports the delivery of a 2019 government manifesto commitment. The paper highlights the importance of WASH services to global health, and stresses the need for WASH services in primary healthcare facilities. This points to another likely feature of future UK WASH support raised in our interviews – the incorporation of WASH elements into other sector programmes, particularly health and education.

Feedback from external partners on these new strategic directions was positive, but cautious. There was widespread agreement on the need to focus on building WASH systems and mobilising other sources of finance. However, interviewees warned that system building requires significant, long-term investments in institutions, infrastructure, partnerships and community behaviour change. The UK’s system-building ambitions therefore call for even greater resources and commitment. Stakeholders (both within and outside the department) also questioned how effective a system-building approach can be in fragile and conflict-affected environments, where resources are more limited and institutional capacity is harder to build.

Stakeholders expressed concerns that WASH components incorporated into health and education programmes might not be given sufficient priority by implementing partners, given the challenges involved in achieving sustainable WASH services. There were also concerns as to whether FCDO retains enough technical expertise in WASH, particularly at country level, to support system building. Some of the new centrally managed programmes under preparation may offer a means of bringing in additional expert capacity.

The importance of water, sanitation and hygiene for women and girls

Health impacts are not the only reason for investing in water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH). Around the world, girls and women are disproportionately impacted by inadequate WASH access. One of the most direct impacts is the burden of collecting water, which in 80% of households without access to running water falls to women and girls. Globally, women and girls spend 200 million hours each day collecting water, taking time away from livelihood activities and schoolwork. These journeys can also place them at increased risk of gender-based violence, as does a lack of private and secure sanitation. This underlines the importance of adequate and functioning WASH facilities in, or close to, the home. Increasing water scarcity will be one of the most direct and serious impacts of climate change in many developing countries, with direct impact on women and girls.

Globally, one in four primary health clinics lacks clean water and, in sub-Saharan Africa, 7% lack any handwashing facilities. This increases the risks of infection for mothers and newborn infants, as well as facilitating the transmission of epidemic disease. Only 69% of schools have access to clean water, while 19% have no sanitation services at all, affecting 367 million children. The lack of safe and private spaces for girls to manage menstruation causes many to miss school days each month, with long-term consequences for their education.

The UK government has committed to making women and girls central to its approach to international development. The government’s manifesto pledges UK support for 12 years of quality education for every girl in the world, and to end the preventable deaths of mothers, infants and children by 2030. The foreign secretary, Liz Truss, who is also minister for women and equality, has reaffirmed the UK’s commitment to gender equality, and undertaken to step up UK support for tackling violence against women and girls (VAWG) – although an internal analysis by the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO) suggests that recent UK aid budget reductions are likely to lead to significantly reduced services for VAWG survivors in the short term.

It is therefore significant that the UK’s new approach to WASH, announced in 2018, stresses the role that WASH can play in supporting gender equity, reducing VAWG and improving health outcomes for women and children. We noted that gender issues had been incorporated into the design of the UK WASH programmes we examined.

Across the WASH sector, there is considerable evidence on the value of gender-sensitive programming that integrates the views of women and girls into all stages of the programme cycle, from situation analysis and design through to implementation and monitoring. Programming that engages with women and girls is more likely to be responsive to their needs, and may help empower them to hold decision makers and service providers to account.

Water, sanitation and hygiene research and global influencing

The UK has been a leading investor in research on water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH) for many years, drawing on the depth of expertise available in UK universities. In our 2016 review, we noted that the UK had supported a range of influential research projects, including Sanitation and Hygiene Applied Research for Equity (£16 million; 2010-2018), which funded an international consortium of research partners led by the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine to identify and fill critical research gaps on sanitation and hygiene. It supported over 50 research projects, produced 110 peer-reviewed publications and around 200 other products, such as evidence summaries and guides. The UK-funded REACH: Improving Water Security For the Poor programme (£22.5 million; 2015-2024), led by Oxford University with a network of international partners, uses an interdisciplinary approach to generate new evidence on water security issues.

The UK’s WASH research portfolio has been curtailed by the pandemic and UK aid budget reductions, and some research programmes have seen substantial budget reductions. Some of the stakeholders we interviewed were concerned that the UK’s traditional strengths in the area may have been eroded.

The UK also has some long-standing investments in support of global WASH initiatives. Its Global Water Leadership Programme (£15 million; 2020-2024) supports, among other things:

- The work of the Global Water Partnership on water governance and integrated water resource management.

- The Sanitation and Water for All initiative (SWA), hosted by UNICEF (the United Nations Children’s Fund), which is a forum that brings together developing countries at ministerial level, together with development partners, non-governmental organisations and researchers, to promote the uptake of effective approaches to WASH. SWA also produces a global report on actions taken to implement Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 6.

- Work by the World Health Organisation (WHO) on global WASH norms and standards.

- The Joint Monitoring Programme for Water Supply, Sanitation and Hygiene, run jointly by WHO and UNICEF, which collects, analyses and publishes data on WASH and progress towards SDG 6.

Box 2: The UK’s international influencing objectives on WASH

FCDO informs ICAI that its four main global influencing objectives on WASH are:

- Focus global attention and resources on the importance of securing and maintaining hygiene behaviour change, particularly handwashing.

- Promote international cooperation on strengthening WASH systems and capacities in developing countries, to accelerate progress towards the SDGs.

- Promote WASH in health facilities and schools.

- Increase the climate resilience of water supply and sanitation services.

Water, sanitation and hygiene in the UK’s pandemic response

Early in the COVID-19 pandemic, hand hygiene was identified by global health experts as a first line of defence against the virus. In April 2020, the World Bank advised that investing in water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH) was “one of the most cost-effective strategies for increasing pandemic preparedness, especially in resource constrained settings”. While the focus later broadened to include mask-wearing, social distancing and vaccination, handwashing is still seen as important in the pandemic, as well as offering wider benefits for health and health security.

The UK moved quickly to support a global drive on hand hygiene. The former Department for International Development (DFID) had been working with Unilever, a global consumer goods company, since 2015 through its TRANSFORM programme (£40.1 million; 2015-2025) to promote innovative, market-based solutions to development challenges in Africa and South Asia. Recognising the company’s expertise in hygiene promotion and its global supply network for hygiene products, DFID approached Unilever in March 2020, in the early weeks of the pandemic, to explore possible collaboration. The outcome was the Hygiene and Behaviour Change Coalition (HBCC), which began operations in May 2020. With a contribution of up to £50 million from the UK government, the HBCC provided grants to 21 non-governmental organisations (NGO) and UN agencies for rapid hygiene-promotion activities. Unilever itself provided £50 million of in-kind contributions, including management support, hygiene products, marketing materials and advertising space. Unilever was also able to use its global network to help partners access soap and hygiene products, at a time when supply chains were breaking down.

The UK contribution also supported the establishment of the Hygiene Hub, hosted by the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, which drew in academic expertise on behaviour change. The Hub provided guidance and public information products for HBCC partners and governments on hygiene and COVID-19 prevention. As the pandemic progressed, its work expanded to include guidance on public communication regarding mask use, social distancing and vaccine uptake. The Hub continues to provide a repository for learning and capturing best practice in hygiene behaviour change interventions.

According to Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO) reviews, the HBCC reached 1.2 billion people with COVID-19 and hygiene messaging in its first year, including 630 million through partner projects and 650 million through a joint Unilever-UNICEF (the United Nations Children’s Fund) mass media campaign. It also supported government-led hygiene coordination mechanisms, provided over 10,000 healthcare centres with WASH facilities, and trained over 140,000 key workers, drawing on guidelines and advice prepared by the Hygiene Hub. There are, however, some questions around the sustainability of the behaviour change it has achieved once fear of the pandemic recedes.

The stakeholders we interviewed praised the speed with which the HBCC had been assembled, making it one of the first donor responses to COVID-19 and one of few devoted specifically to hygiene. They noted the value of bringing together private sector expertise, leading academics, NGOs and UN agencies. The HBCC contributed to raising the profile of hygiene within the global response, with active support from UK ministers. FCDO has recently approved a further £20 million contribution as part of a package of measures to control the spread of the Omicron COVID-19 variant.

Beyond the HBCC, the ability of the UK WASH portfolio to support the COVID-19 response was limited by budget constraints. However, FCDO’s WASH Policy Team produced guidance on how to adapt WASH programmes, and this was done in a number of cases (see Box 3).

Box 3: Examples of UK WASH programmes responding to COVID-19

In Zimbabwe, the UK was the only bilateral donor in the WASH sector at the start of the pandemic. In its final year, the UK programme Support to Improved Water and Sanitation in Rural Areas (£50.6 million; 2012-2021) provided 47,050 households with hygiene kits, 255 public spaces with handwashing stations, 250 schools with WASH services, and 21 local authorities with water treatment chemicals. In Ethiopia,

the UK programme Strengthening Climate Resilient Systems for Water, Sanitation and Hygiene Services in Ethiopia (£95 million; 2019-2024) aims to improve access to climate-resilient WASH services for 1.2 million people in drought-prone districts, including by providing WASH services in schools and health facilities. During the pandemic, the programme supported the Ethiopian government’s response by reallocating resources to improve access to WASH facilities at health centres, schools and public gathering places, as well as supporting related communication and behaviour-change activities.

For the centrally managed Sanitation, Water and Hygiene for the Rural Poor programme, FCDO and UNICEF agreed to repurpose around £2 million in unspent funds to support the development of national COVID-19 response plans and fill critical WASH service gaps in five countries. The programme was permitted to widen its geographical focus to include urban areas and communities assessed as particularly vulnerable to the effects of the pandemic, such as informal settlements and internally displaced persons. FCDO staff worked closely with UNICEF to support the reprogramming.

Suggested further lines of enquiry

Since 2016, the UK’s water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH) portfolio has undergone a substantial change of strategy and approach. It has rebalanced from investing in basic infrastructure towards a new focus on WASH system building and water security. At the same time, there has been a sharp decline in funding levels, as a generation of large, in-country programmes came to an end. Recent UK budget reductions have meant that the new approach is not yet fully implemented, but the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO) informs us that new WASH programmes are in the pipeline.

We conclude by suggesting a number of issues that would merit further investigation, by the Independent Commission for Aid Impact itself, the International Development Committee or other scrutiny bodies.

- UK leadership: Following a period of declining UK bilateral aid for WASH, will the UK regain its global leadership role and rebuild its comparative advantage in the WASH sector?

- Adequacy of investment: Will the UK be willing to sustain the levels of investment required to achieve its system-building goals, and achieve an appropriate balance between system building and

capital investment? - Technical capacity: How will FCDO ensure that it continues to have sufficient technical capacity to support its WASH approach?

- Fragile contexts: Is FCDO’s system-building approach viable in fragile and conflict-affected countries, given resource and capacity constraints?

- Integrated programming: When integrating WASH objectives into health and education programmes, how will FCDO ensure that they receive sufficient resources and attention from implementing partners?

- Gender and climate change: How will the UK integrate the perspectives of women and girls impacted by growing water scarcity into its programming on WASH and water security?

- Hygiene behaviour change: Will the results of FCDO’s investments in handwashing and hygiene behaviour change prove sustainable after fear of the pandemic subsides?