The UK’s humanitarian response to COVID-19

Purpose, scope and rationale

The COVID-19 pandemic has precipitated the most geographically widespread and arguably most complex crisis in modern times. The humanitarian response to this emergency has been unprecedented in scale and global in scope. It was also conducted in a highly uncertain and fluid environment, with limited experience to provide a reliable guide for action. The UK, as a major humanitarian donor, has played a substantial part in this response. As such, a review of the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO), formerly the Department for International Development (DFID) and the Foreign and Commonwealth Office, is warranted not only by the scale of expenditure, but also by the need to learn and apply lessons as the impacts of the pandemic continue.

This review will cover UK emergency support for populations in humanitarian need as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic. This includes funding from central sources to UN-led, global appeals and through other international channels (such as allocations to the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) Central Emergency Response Fund and emergency funding to the Red Cross and international non-governmental organisations). It also includes in-country programming in a sample of case study countries. This includes both new and repurposed funding, including from existing humanitarian programmes, and the work of centrally managed programmes in the case study countries. The review will focus on DFID / FCDO programming only, as opposed to official development assistance (ODA) spent by other government departments.

The review will consider how well the UK responded with humanitarian aid both to the direct effects of the pandemic (caseload and deaths)1 and the indirect effects, including impacts on livelihoods from public health measures, the effects of disruption to public services and the increased incidence of violence against women, girls and vulnerable people. The review will also consider how well UK aid acted to minimise the impact of the pandemic on pre-existing humanitarian caseloads. It will not consider UK aid support for the development and distribution of COVID-19 vaccines, which is covered in ICAI’s rapid review of the broader UK aid response to COVID-19.

This review complements and will build on a number of other ICAI reviews, including a rapid review of the UK’s aid response to COVID-19 (October 2021), a review of procurement during the early phase of the pandemic response (December 2020), a review of the management of the UK’s ODA 0.7% spending target in 2020 (May 2021), and a review of the UK’s approach to funding the UN humanitarian system (December 2018).

It will also draw on a November 2020 report by the International Development Committee on the humanitarian impact of the pandemic on developing countries, and will complement a planned programme of work by the National Audit Office focused primarily on the domestic component of the UK government’s response to COVID-19.

The rapid review of the UK aid response to COVID-19 explored the initial phase of the UK’s aid response to the pandemic, focusing on the relevance of its funding choices and the efficiency with which it mobilised resources. This review will investigate these processes in more depth and explore the effectiveness of the UK government’s humanitarian support to those most vulnerable to the effects of the pandemic.

Background

While COVID-19 has been global in impact, its effects have been uneven: some countries and regions have fared better so far in containing the pandemic, while others have faced – and continue to face – acute public health emergencies. The UN reports that COVID-19 has had a particularly heavy impact on already vulnerable groups, including women and girls, people with disabilities and the elderly. International humanitarian actors were quick to recognise the potential for the pandemic to result in sharp increases in humanitarian need.

The International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies launched its first Global Emergency Appeal for COVID-19 in January 2020, followed by the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA)-led Global Humanitarian Response Plan, launched in March 2020. The UK made significant contributions to both global appeals. As the pandemic continued, these multilateral initiatives became integrated into national emergency response plans.

The UK government recognised at an early stage that there would need to be a significant reallocation of UK aid in response to the pandemic. It set out the objective of supporting a coordinated global response by channelling a significant share of its resources through multilateral institutions. By mid-April 2020, the UK had announced £744 million in central funding, including support for the global humanitarian appeals. By January 2021, the UK had committed £1.3 billion to fight COVID-19 globally. Of this, 90% was channelled through multilateral institutions and global appeals.

In March 2020, country offices were instructed to redirect resources from existing aid programmes to address both the impacts of the COVID-19 virus and measures taken to contain its spread in developing countries. All country programmes were reprioritised against a gold (drive), silver (manage), bronze (pause) set of criteria. Ongoing humanitarian operations were prioritised alongside the COVID-19 response. ICAI’s rapid review of the UK’s aid response to COVID-1911 found that country offices examined their portfolios to identify components of existing programmes that were no longer relevant or could not be implemented as planned under pandemic conditions and repurposed unused funds towards the COVID-19 response.

The UK’s humanitarian response to the pandemic took place during a period of considerable uncertainty for the UK aid programme. Since the start of the pandemic, the UK’s aid budget has been substantially reduced, first as a result of the contraction in UK gross national income (GNI) in 2020 and later as a result of the government’s decision to temporarily reduce the aid target to 0.5% of GNI. While the aid reductions and their management are not the subject of this review, they had an impact on the COVID-19 response.

The humanitarian response to COVID-19 remains a significant priority for the UK aid programme in 2021. Within the strategic priorities for the UK aid programme identified in the Integrated Review, the ongoing COVID-19 response falls under global health security, which was allocated £1.3 billion in total. This includes funding for vaccine development and distribution, support for the World Health Organisation and humanitarian support for the countries in greatest need.

Review questions

This review looks at the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office’s (FCDO) emergency support to populations in humanitarian need during the COVID-19 pandemic. It will focus on three evaluation criteria: relevance (the degree to which activities funded responded to priority needs), coherence (compatibility with other interventions and activities, both within and beyond the UK government), and effectiveness (the extent to which the activities funded achieved their objectives). It will address the questions and sub-questions outlined in Table 1:

Table 1: Our review questions

| Review criteria and questions | Sub-questions |

|---|---|

| 1. Relevance: How well did the UK government prioritise its humanitarian response to COVID-19? | • To what extent were funding allocations guided by evidence on the impacts of the pandemic on vulnerable populations and emerging evidence of effective mitigation measures? • To what extent did the UK government support consultation with affected populations and seek to address community priorities in the design of its response? • To what extent did the response reflect relevant principles from the Grand Bargain15 and the Triple Nexus16? |

| 2. Coherence: To what extent has the UK supported a coherent humanitarian response to COVID-19? | • To what extent did UK participation in joint mechanisms, advocacy and influencing work with multilaterals, other donors and partner country governments support a coherent and coordinated humanitarian response to the pandemic? • To what extent was the UK humanitarian response coherent within its overseas network and departments? |

| 3. Effectiveness: To what extent has the UK humanitarian response to COVID-19 saved lives, reduced suffering and helped affected populations to build resilience? | • To what extent did the UK aid response succeed in reaching vulnerable people, including marginalised groups? • To what extent has UK support helped to increase the resilience of partner countries and affected populations to future health emergencies? |

Methodology

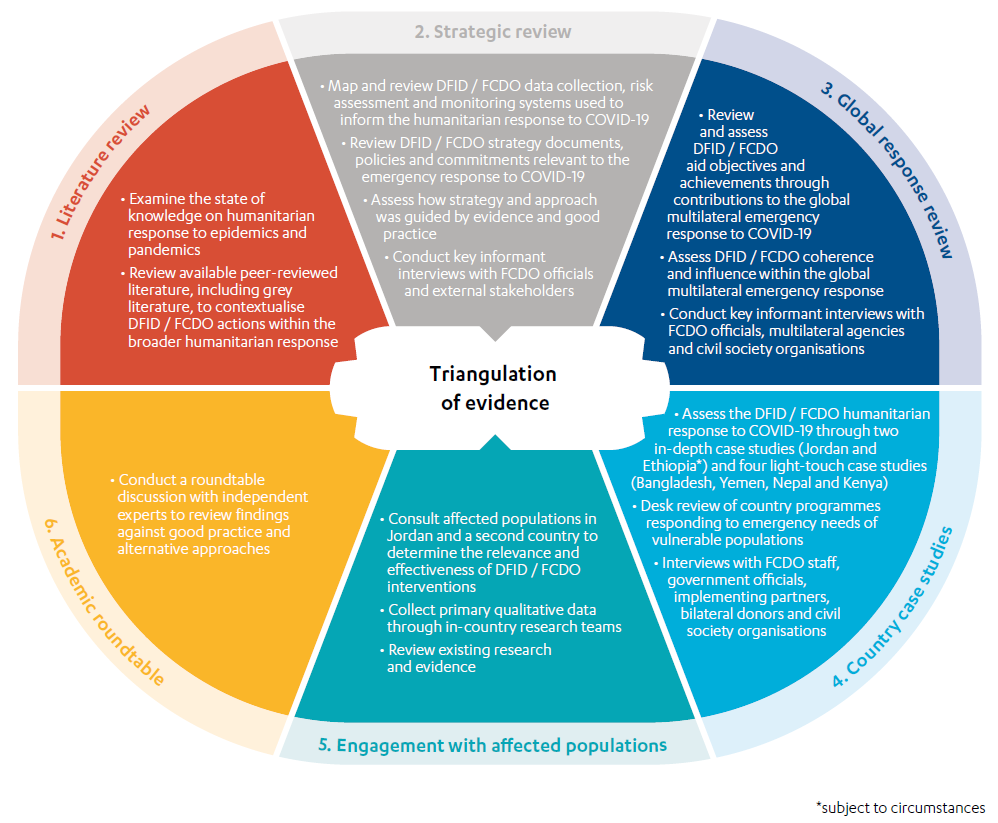

The methodology includes the following six components to allow for data triangulation to robustly answer the review questions.

Figure 1: Overview of the methodology

Component 1 – Literature review: We will conduct a review of the available peer-reviewed literature and grey literature. This will both outline the state of knowledge on humanitarian response to epidemics and pandemics, to help determine the degree to which UK actions were based on available evidence, and consider the actions of the broader humanitarian ‘system’ – including key donors – over the period, to contextualise the UK government’s actions within the broader humanitarian response, and to compare these actions with those of other donors.

Component 2 – Strategic review: We will conduct a review of the UK’s data collection, risk assessment and monitoring systems, strategy documents and policies relevant to the UK emergency response to COVID-19. We will also examine which financing instruments were used to support the UK’s humanitarian response to COVID-19. This will allow us to assess the degree to which the strategy and approach were guided by evidence and took account of existing commitments and good practice. It will also serve as the basis to determine whether actions followed the prescribed strategies.

Component 3 – Global response review: This component will review and assess the UK’s aid objectives and achievements in its contributions to the global multilateral emergency response to COVID-19 over the period from January 2020 to August 2021. It will also look at the UK’s coherence with the global multilateral emergency response, including its influencing objectives and how well the UK aligned with other actors. The review will draw on evidence from FCDO programme documents and key informant interviews with UK and global implementing partner staff.

Component 4 – Country case studies: We will review FCDO’s emergency response to COVID-19 in six case study countries. This will include two in-depth case studies (Jordan and Ethiopia*) and four lighter-touch desk-based case studies (Bangladesh, Yemen, Nepal and Kenya). See Section 5 below for the sampling criteria. The case studies will assess the UK’s humanitarian response at the portfolio level, including the quality of evidence collection, consultations and needs assessment, the UK’s cooperation with national authorities and other development partners, and the extent to which pandemic-related programmes and activities achieved their objectives. The case studies will also identify particular themes or programming areas in each country for more detailed investigation.

Component 5 – Engagement with affected populations: ICAI is committed to incorporating the voice of people expected to benefit from UK aid into its reviews. Consultations with affected populations in Jordan and a second country will be undertaken by a national partner, using a combination of virtual and in-person methods as appropriate in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. The consultations will focus on vulnerable groups targeted by FCDO programmes to determine whether the UK’s interventions were relevant to their needs and priorities. Other vulnerable populations, not targeted by UK aid, will also be consulted to capture the effects of the pandemic and to determine the extent to which the UK’s interventions were relevant to broader needs and priorities. Findings will be triangulated through review of relevant available secondary data in the two countries.

Component 6 – Academic roundtable: We will hold a discussion with independent experts to review findings against good practice and alternative approaches.

* Subject to circumstances relating to the recent declaration of a nationwide state of emergency. Ethiopia declares nationwide state of emergency, Al Jazeera, November 2021, link.

Sampling approach

ICAI recognises that COVID-19 has affected different countries and different population groups (for example women and girls, informal workers) in different ways. This review will undertake six country case studies to explore the relevance, coherence and effectiveness of the UK’s humanitarian response to COVID-19. This yields a sufficiently representative sample of country contexts and humanitarian needs, given the time and budget constraints for this review.

The review will take a purposive approach to guide the selection of countries to review. To obtain a representative sample from across the UK aid programme, the sampling criteria set out in Table 2 have been applied. In addition to the criteria listed in Table 2, ICAI has sought a balance of geographical spread and a mix of lower- and middle-income countries.

Table 2: Selected case study countries

| UK aid bilateral programme over £40 million in 2020* | Moderate to high vulnerability to COVID-19** | At least two countries with large-scale humanitarian crisis (anticipated need over $500m in 2020) | At least two fragile and conflict-affected states | At least one country with less than 10% humanitarian programming (UK ODA) | At least one country with more than 1 million internally displaced people | At least one country with over 800,000 refugees | At least one country with over 50% of the population considered food-insecure | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bangladesh | £196m | Tick | Tick | Tick | ||||

| Ethiopia | £244m | Tick | Tick | Tick | Tick | |||

| Jordan | £65m | Tick | Tick | |||||

| Kenya | £63m | Tick | Tick | |||||

| Nepal | £78m | Tick | ||||||

| Yemen | £205m | Tick | Tick | Tick | Tick | Tick |

Limitations to the methodology

This review will inevitably be subject to a number of limitations, which will affect the degree to which comprehensive, robust and fully triangulated findings can be obtained. Key limitations are summarised below.

The ongoing COVID-19 pandemic: This may continue to create travel restrictions to and within partner countries and restrict face-to-face meetings with programme partners and affected populations. If this is the case, interviews will be conducted remotely and through in-country partners where appropriate. A particular challenge is the degree to which engagement with affected populations can be conducted in ways that safeguard vulnerable communities while ensuring that the voices of marginalised groups are effectively heard and represented.

Uncertainty around good practice: Many reviews can evaluate performance against existing standards or good practice. However, this is not possible for the humanitarian response to COVID-19. DFID/FCDO and partner staff have been operating in an unprecedented context and without established evidence on good practice for a global pandemic. However, the substantial body of good practice learning from previous crises, particularly Ebola and SARS health threats, will be considered.

Limited availability of literature: The global pandemic is unprecedented in nature and therefore the availability of relevant literature, peer-reviewed or otherwise, is limited. There may be limited literature available from other donors arising from their COVID-19 response, to allow a comparative analysis. If literature is found to be limited, there will be a requirement to rely more heavily on interviews.

Disaggregating COVID-19 impacts and response: In addition to needs that have arisen from the COVID-19 pandemic, all six of our country case studies face multiple existing and emerging humanitarian shocks and longer-term stresses, such as food insecurity, climate change, conflict and displacement. Yemen, Ethiopia and Bangladesh face large-scale humanitarian crises and varied levels of humanitarian access and communications restrictions. This makes disaggregation of COVID-19 impacts and the COVID-19 response more complex.

Our sampling approach seeks to address this through selecting a range of countries with diverse humanitarian needs, for comparison. In addition, the review will explore humanitarian need attribution through country-level interviews as well as affected population engagement in Jordan and a second country. As circumstances allow, affected people will be engaged in person through focus group discussions conducted by locally based research teams with knowledge of the affected populations’ spoken languages.

Data on effectiveness and resilience: As the pandemic is still ongoing, evaluations are likely to be limited. Data may not yet be available on effectiveness, particularly with regard to secondary impacts of the pandemic, for example on livelihoods, education, and sexual and gender-based violence. Our methodology depends primarily on data generated by programme monitoring and evaluation systems to assess effectiveness. Reported results will be triangulated through review of relevant accessible secondary data (where available) and, to a limited extent, through key informant interviews and feedback from people expected to benefit.

We will conduct our own assessment of the credibility of the results data that has been generated. However, since our methodology depends on data produced by programmes, we may not be able to reach conclusions on the programmes if this data is of poor quality or the collection of this data has been delayed or is deemed unreliable. Similarly, evidence of the extent to which the COVID-19 humanitarian response has contributed to building resilience may only be available further down the line.

Risk management

We have identified several risks associated with this review and propose a series of mitigating actions, where necessary, as presented below in Table 3.

Table 3: Risks and mitigation

| Risks | Mitigation and management actions |

|---|---|

| In-person visits by the review team are not possible due to COVID-19 restrictions on entry and movement. | • We will conduct virtual country visits where in-person visits are not possible. These will include interviews with a wide range of stakeholders. Lessons learned from recent ICAI reviews that have included virtual visits will be applied. |

| Case study countries are vulnerable to other humanitarian or further COVID-19 shocks that could impact the review plans. | • We will monitor the humanitarian18 and COVID-19 context in each country, and liaise with the FCDO to identify and respond to shocks. |

| Engagement with affected populations cannot be undertaken face to face in the case study countries due to COVID-19 restrictions. | • We will engage in-country partners for engagement with affected populations and assess access restrictions as part of the design criteria for this component. Where travel is restricted, we will seek remote interviews where necessary. We will be guided by security and local travel and meeting advice, adapting all plans accordingly. |

| The speed of the response and rapid repurposing of funds makes it difficult to identify all official development assistance (ODA) repurposed for the humanitarian response. | • We will consult relevant FCDO stakeholders to determine ODA funds repurposed across humanitarian and development budgets and programmes, examining collaboration between humanitarian and development actors. We will also review relevant centrally managed programmes that pivoted to support the humanitarian COVID-19 response. |

Quality assurance

The review will be carried out under the guidance of ICAI chief commissioner Tamsyn Barton, with support from the ICAI secretariat. The review will be subject to quality assurance by the service provider consortium.

Both the methodology and the final report will be peer reviewed by Silvia Hidalgo, co-founder of DARA (Development Assistant Research Associates). Silvia is an expert on humanitarian action and development evaluation and improvement of policy and practice.

Timing and deliverables

The review will take place over a ten-month period, starting from July 2021.

| Phase | Timing and deliverables |

|---|---|

| Inception | Approach paper: November 2021 |

| Data collection | Desk research: August – October 2021 Fieldwork: October – December 2021 Evidence pack: December 2021 Emerging findings presentation: January 2022 |

| Reporting | Report drafting: February – April 2021 Final report: June 2022 |