The UK’s humanitarian response to COVID-19

Score

The UK’s rapid humanitarian response to the COVID-19 pandemic has saved lives and built resilience, but could have done more to ensure inclusion of some vulnerable groups

The UK government was quick to recognise the likely impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic in developing countries, and to mobilise a response at both global and national levels. Its efforts were informed by knowledge and experience from past health crises and extensive collection of evidence on the pandemic’s unfolding impact. The UK made a substantial early contribution of unearmarked funds to the global humanitarian response, giving international agencies the flexibility to respond to a rapidly evolving situation. At the country level, while there was no new funding for the COVID-19 response, the UK worked systematically to identify opportunities to adapt programmes and support national responses. The UK’s reliance on existing programming channels, however, meant that groups made newly vulnerable by the pandemic, including the elderly, the urban poor and migrant workers, were not always given priority in the response.

The UK’s response was coherent and coordinated, both across the department and with international partners, and it made an important contribution to national coordination and information-sharing mechanisms. Successive reductions to the UK aid budget in 2020 and 2021, and the September 2020 creation of the merged Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office, however, came at an inopportune time during the pandemic, hampering the UK response. Nonetheless, we find that the UK made a substantial contribution to saving lives and reducing hardship during the critical early phase of the pandemic. The UK’s response has also helped build resilience to future emergences by strengthening national systems and capacities, therefore meriting an overall green-amber score.

Individual question scores:

- Relevance: How well did the UK government prioritise its humanitarian response to COVID-19? Green / Amber

- Coherence: To what extent has the UK supported a coherent humanitarian response to COVID-19? Green / Amber

- Effectiveness: To what extent has the UK humanitarian response to COVID-19 saved lives, reduced suffering and helped affected communities to build resilience? Green / Amber

Acronyms and glossary

| Acronym | Definition |

|---|---|

| ATM | Automated teller machine |

| CERF | Central Emergency Response Fund |

| DFID | Department for International Development (merged with the Foreign and Commonwealth Office in September 2020) |

| EMT | Emergency Medical Team |

| FCDO | Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office |

| FCO | Foreign and Commonwealth Office (merged with the Department for International Development in September 2020) |

| GHRP | Global Humanitarian Response Plan |

| H2H | Humanitarian 2 Humanitarian Network |

| ICRC | International Committee of the Red Cross |

| IFRC | International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies |

| LGBT+ | Lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender/transsexual people |

| NGO | Non-governmental organisation |

| OCHA | United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs |

| OECD DAC | The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development’s Development Assistance Committee |

| PPE | Personal protective equipment |

| RRF | Rapid Response Facility |

| UN | United Nations |

| UNFPA | United Nations Population Fund |

| UNHCR | United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees |

| UNICEF | United Nations Children’s Fund |

| WASH | Water, sanitation and hygiene |

| WFP | World Food Programme |

| WHO | World Health Organisation |

| Glossary of key terms | |

|---|---|

| Earmarked | Earmarking is the practice of specifying the purpose of a funding allocation. Funds might be earmarked to the level of a country, crisis, sector, population or project, for example. |

| Grand Bargain | A global commitment to better serve people in need through a series of aid reforms agreed at the 2016 World Humanitarian Summit. Thirty representatives of Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) donors and aid agencies produced a package of 51 commitments to make humanitarian financing and response more efficient and effective. These reforms notably include a commitment to increased support for local responders and increased use and coordination of tools such as cash-based programming. |

| Indirect impacts | Indirect effects of COVID-19, including impact on livelihoods from public health measures, the effects of disruption to public services, and the increased incidence of violence against women, girls and vulnerable people. |

| Localisation | While there is no single definition of localisation in a humanitarian context, signatories to the Grand Bargain have committed to making “principled humanitarian action as local as possible and as international as necessary”. Grand Bargain signatories commit to engaging with local and national responders in a spirit of partnership and aim to reinforce rather than replace local and national capacities. This can include governments, communities, Red Cross and Red Crescent National Societies and local civil society. |

| Primary impacts | Deaths and illness associated with the COVID-19 virus. |

| Triple nexus | The ‘triple nexus’ or Humanitarian-Peace-Development nexus is a shorthand term to refer to the interlinkages between humanitarian, development and peacebuilding approaches. The OECD Development Assistance Committee (DAC) recommendation describes it as having “the aim of effectively reducing people’s needs, risks and vulnerabilities, supporting prevention efforts and thus, shifting from delivering humanitarian assistance to ending need”. |

| Unearmarked | Refers to ‘core’ funds which are not restricted for specific use, such as a particular field project or for a specific outcome. These unearmarked donor funds can only be provided to the OECD DAC list of eligible multilateral partners. |

Executive summary

The COVID-19 pandemic created a humanitarian crisis of unprecedented scale. With humanitarian need already at historically high levels at the beginning of the pandemic, COVID-19 and the lockdown measures imposed by governments to contain it threatened the lives and livelihoods of vulnerable people around the world. In March 2020, the UN launched its first ever global humanitarian appeal to respond to the COVID-19 pandemic, and by the end of 2020 it was appealing for £7.6 billion in support for 63 countries.

As a major humanitarian donor, the UK made a significant financial contribution to the global humanitarian response, committing £218.7 million in central funds5 by February 2020. It also adapted its bilateral aid programmes to support national responses to the pandemic.

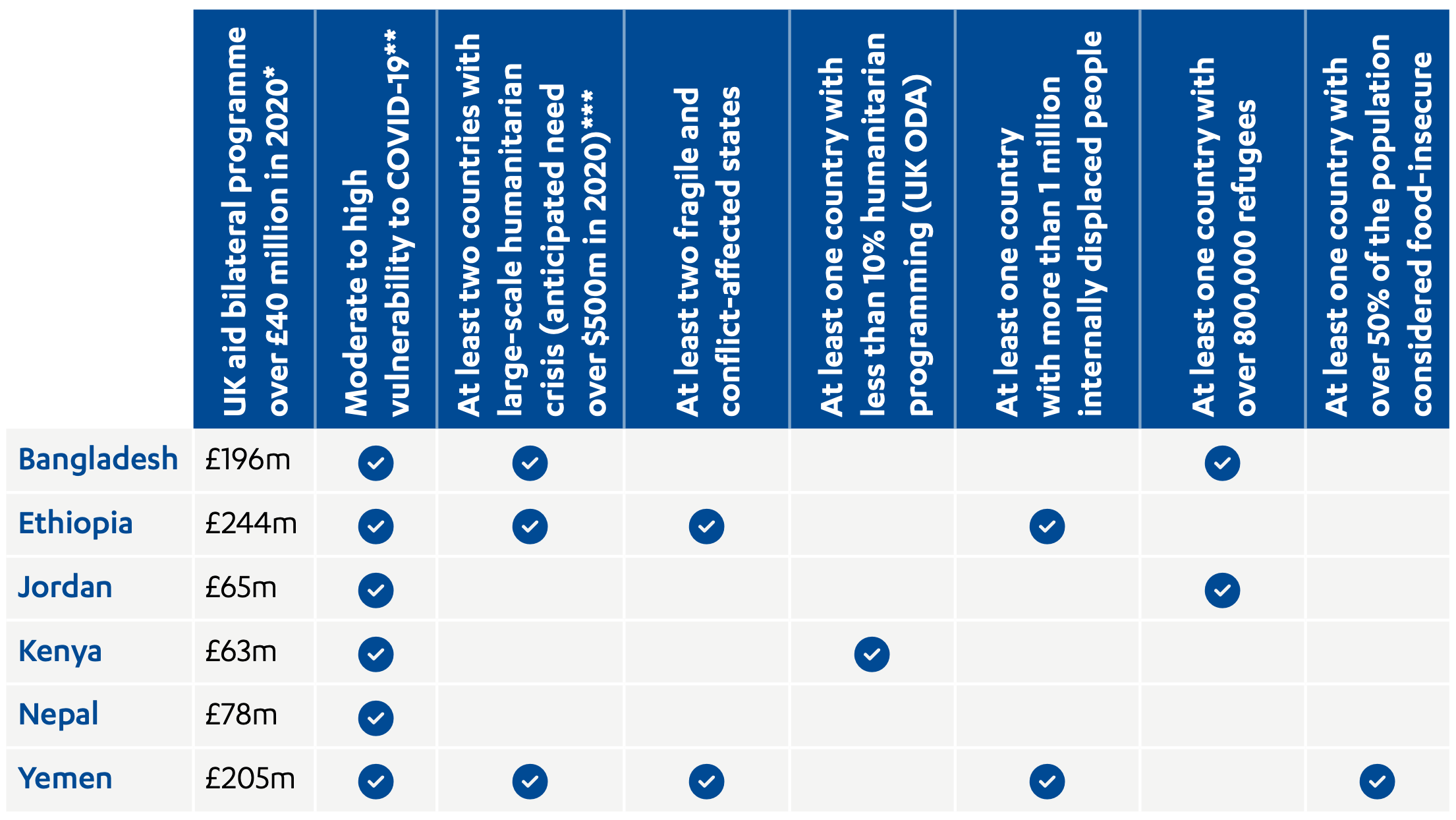

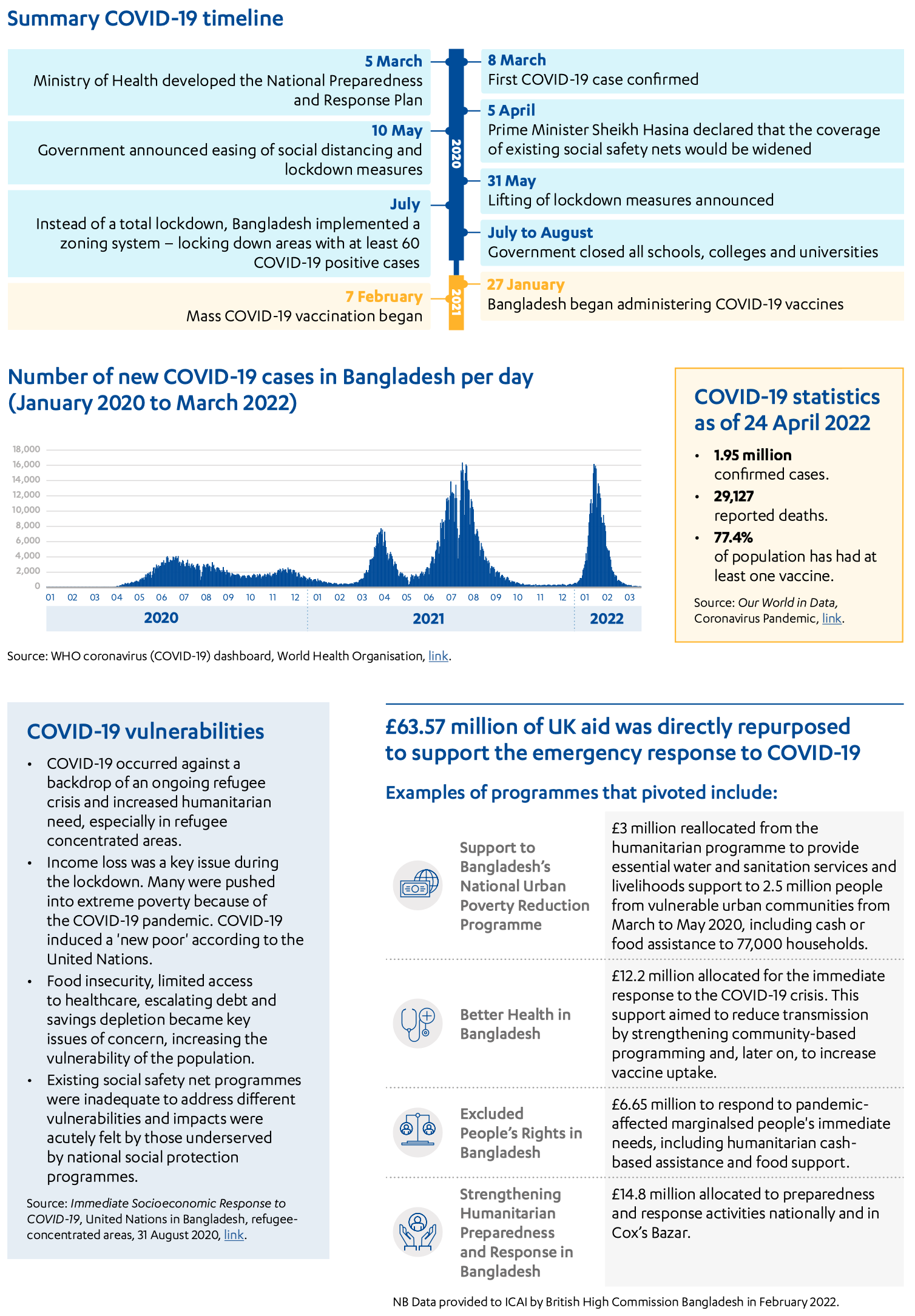

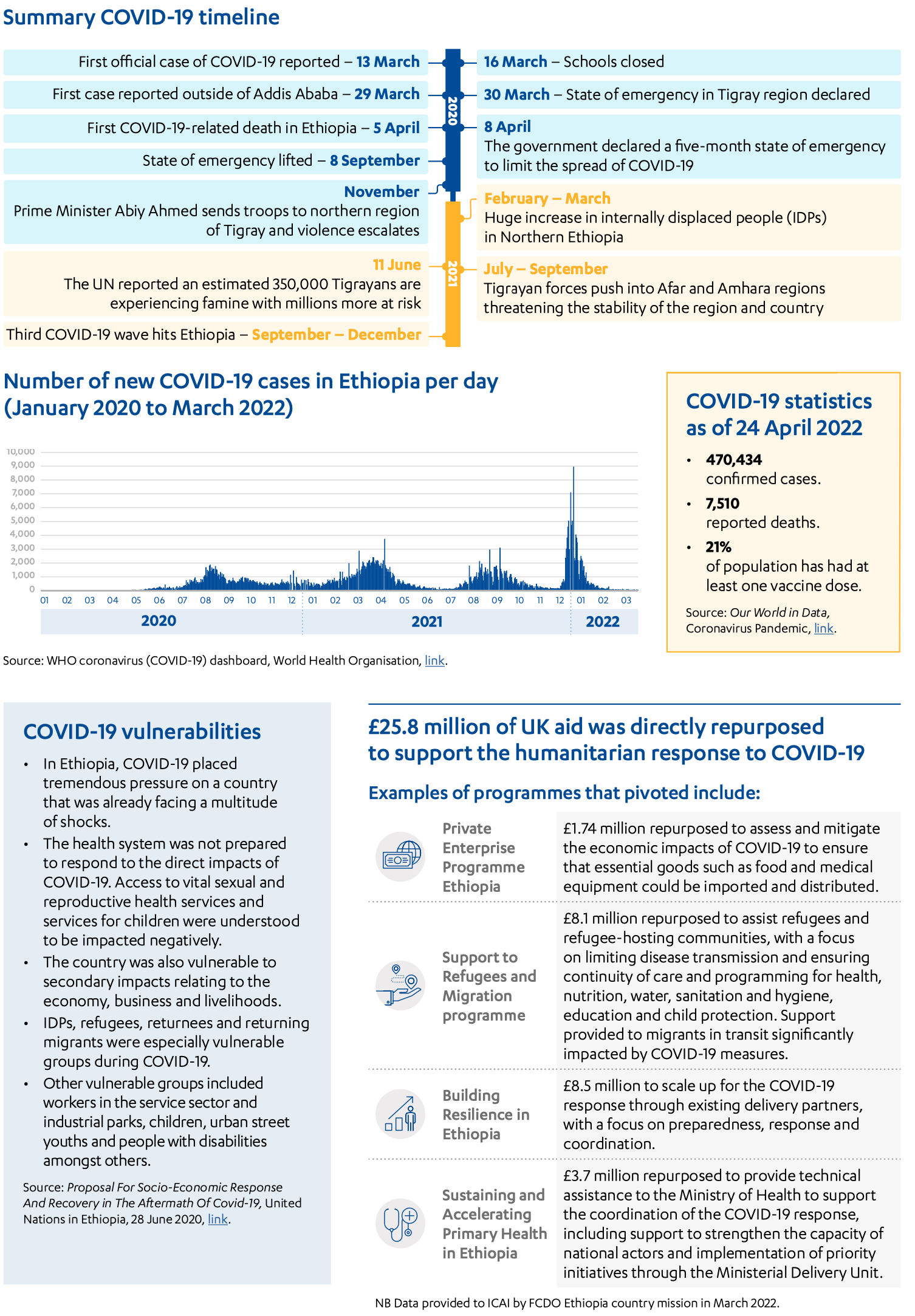

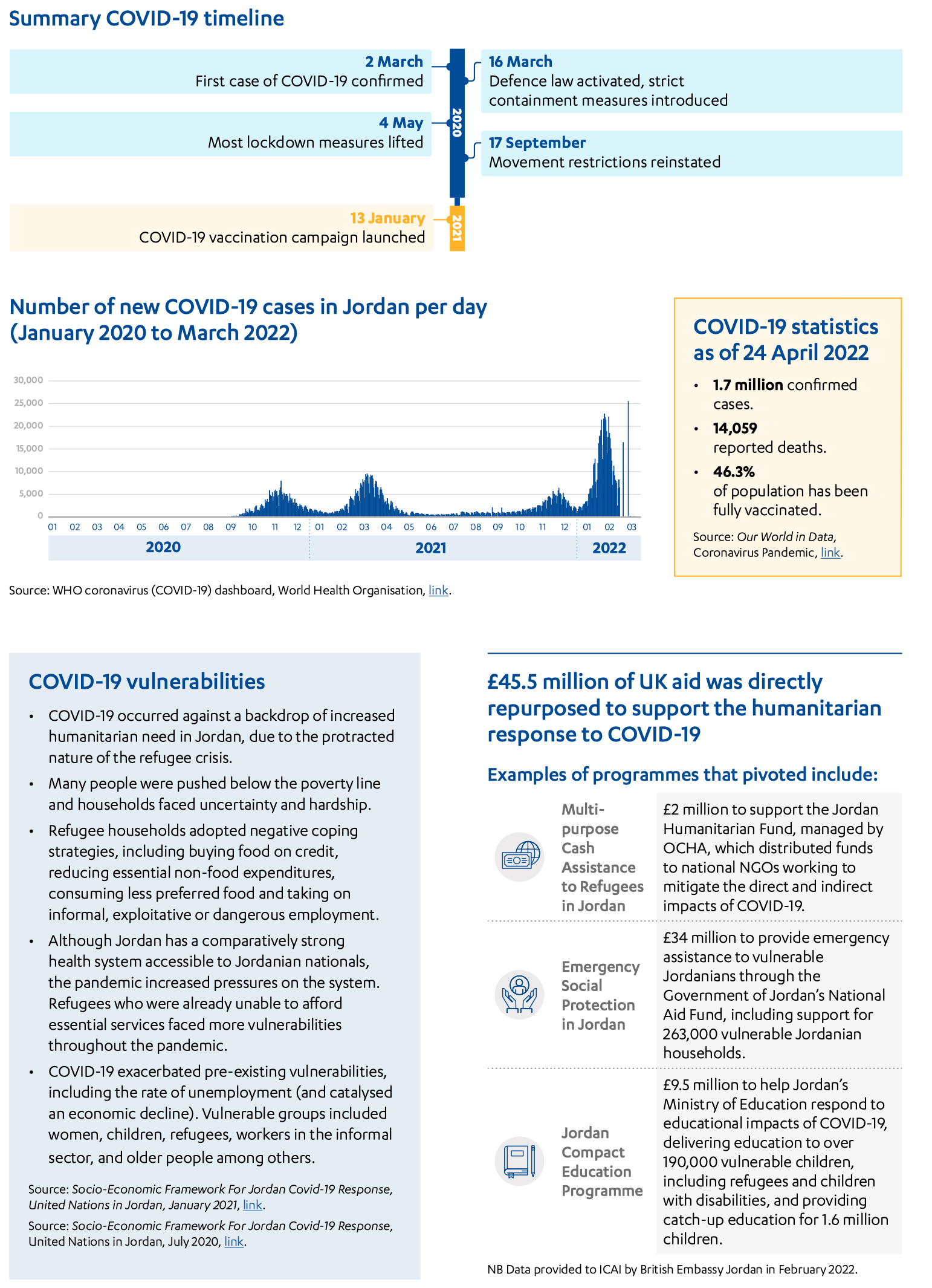

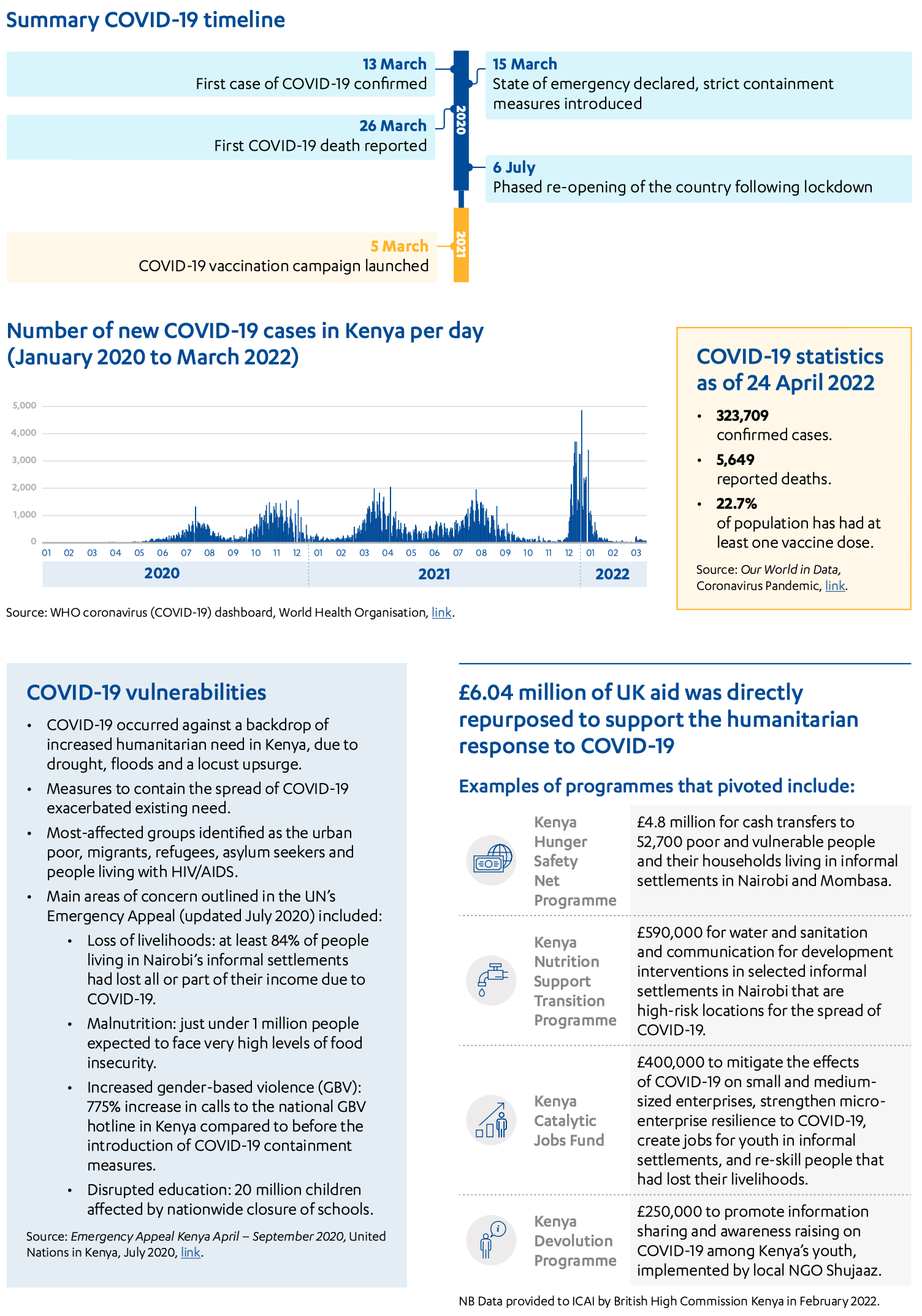

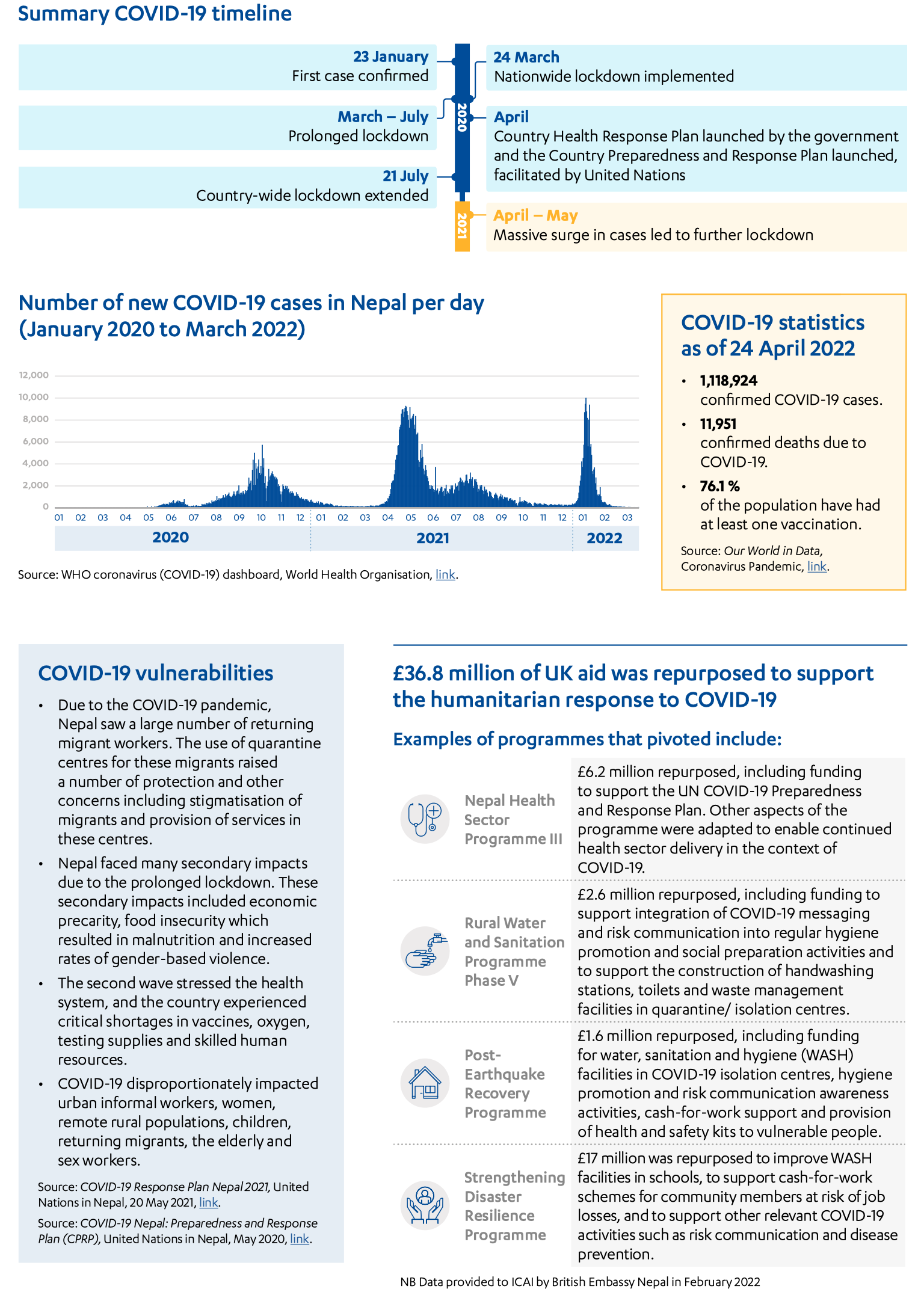

This review assesses two years of the UK’s emergency response to COVID-19, from the onset of the pandemic to February 2022, focusing on the work of the former Department for International Development (DFID) and, from September 2020, the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO).6 In this report, the term “the department” refers to DFID before the merger and to FCDO thereafter. We analyse the relevance, coherence and effectiveness of the response, looking at the UK’s central humanitarian funding and its bilateral response in six countries: Bangladesh, Ethiopia, Jordan, Kenya, Nepal and Yemen. The review identifies lessons to inform UK aid responses to future large-scale health emergencies.

Relevance: How well did the UK government prioritise its humanitarian response to COVID-19?

The UK government was quick to realise the threat that COVID-19 posed to developing countries. Although its initial humanitarian response was allocated before the full impacts of the pandemic were known, early evidence indicated that the COVID-19 outbreak would quickly reach global scale, with wide-ranging impacts on vulnerable people. To facilitate a rapid response, the UK government applied ‘no regrets’ decision- making – that is, in the face of considerable uncertainty, it prioritised interventions that would benefit target communities whatever course the pandemic took, rather than delaying the response until more data were available. It drew on the knowledge and experience of staff that had worked on past health epidemics, including the 2014-16 Ebola outbreak in West Africa, and coordinated with partners to gather real-time information on the evolving impacts.

The UK allocated £218.7 million in central humanitarian funding to the COVID-19 response in the early weeks of the pandemic, including through UN agencies, the Red Cross and international non-governmental organisations. Most of this funding was not earmarked for specific purposes or locations, providing the global humanitarian system with the flexibility to respond to a rapidly evolving global crisis. We find that the decision to provide an early, flexible and substantial contribution to the global humanitarian system was well justified. However, a planned second tranche of central funding for the humanitarian response was not provided because of reductions in the UK aid budget in the summer of 2020. According to FCDO staff, the second tranche would have been more explicitly directed towards the most vulnerable as new evidence on these groups was emerging.

At country level, no new funding was provided for the COVID-19 response, but the UK looked systematically for opportunities to ‘pivot’ existing programmes to support emergency needs arising from the pandemic. As a result, the UK response was primarily directed towards those who were already receiving support before the pandemic. The UK was not well positioned to support groups made newly vulnerable by the pandemic, such as the elderly, people with underlying health conditions, the urban poor and informal sector workers deprived of income as a result of lockdown measures. There was also limited scope for consultation with vulnerable groups, both directly and through partners, due to travel restrictions, social distancing and the need to avoid inadvertently transmitting the virus.

We found little evidence that the UK response helped advance commitments on reforming the international humanitarian system in the areas of localisation (directing more aid through national and local responders) and accountability to affected populations. However, the UK response was well joined up across the humanitarian and development spheres, and made extensive use of cash-based support, which enabled the people targeted to prioritise their individual needs.

As the pandemic has evolved, the UK government has integrated its COVID-19 response into broader humanitarian and development programmes, recognising that in many contexts other humanitarian needs were more acute. This aligns with the approach being taken by other donors and development agencies and appears to be an appropriate choice. However, we were consistently told that successive reductions to the UK aid budget in 2020 and 2021 had reduced the UK’s ability to respond to the unfolding pandemic.

Overall, we award a green-amber score for relevance, in recognition of the rapid and flexible response in the early phase of the pandemic.

Coherence: To what extent has the UK supported a coherent humanitarian response to COVID-19?

The UK government made it an early priority to enable the multilateral system to deliver an effective global response to the pandemic, and generally worked well with multilateral partners. Its flexible contribution helped improve the coherence and coordination of the multilateral response, and was an efficient way of getting funds and equipment to where they were needed most. At country level, partners highlighted the UK’s important role in promoting coordination and information sharing in support of national response plans.

Despite its speed, the UK’s humanitarian response was well coordinated across the department, both centrally and at country level. The UK’s ability to combine humanitarian and development interventions in flexible ways was a real strength. However, the volume of information demanded of country teams was at times overwhelming, diverting time and focus away from implementing the response, and was often beyond the department’s capacity to process and use. Internal coordination was also made more challenging by an overly risk-averse drawdown of overseas staff, with several health and humanitarian advisers recalled to the UK at periods when they were needed most.

We award a green-amber score for coherence, in recognition of a strong UK contribution to coordination.

Effectiveness: To what extent has the UK humanitarian response to COVID-19 saved lives, reduced suffering and helped affected communities to build resilience?

The UK’s humanitarian response to COVID-19 has saved lives and reduced suffering by mitigating the direct and indirect impacts of the pandemic. The commitment of flexible funding to multilateral agencies helped enable rapid, large-scale mobilisation of support for vulnerable countries and communities. While the results are difficult to quantify, they included procurement and delivery of essential medical supplies at a time when global supply chains were not working, including personal protective equipment (PPE), diagnostics, vaccines, therapeutics, oxygen concentrators and cold-chain freezers for vaccines. The UK also deployed Emergency Medical Teams to at least 12 countries to support national responses to the pandemic.

Country programmes were adapted to provide tailored support to national health systems, including community awareness raising, hygiene promotion, isolation and treatment centres (especially for refugees) and medical supplies. UK support also included infection prevention and control measures across its wider programming, such as support for handwashing, sanitiser and PPE and social distancing. In some instances, the UK supported COVID-19 treatment, including in the world’s largest refugee camp, in Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh.

The UK also funded social protection payments for groups which were especially vulnerable to lockdown measures. These included the urban poor, informal sector and migrant workers, people with disabilities and female-headed households, although coverage of these groups varied between countries. This support was particularly effective where the UK had made long-term investments in strengthening national social protection mechanisms. In Jordan, for example, informal sector workers who lost income during the pandemic received emergency support through the National Aid Fund, although this was not available to non-Jordanian migrant workers. In Ethiopia, the Rural Poverty Safety Net Programme was able to support rural communities badly affected by the pandemic, although it was not in a position to support the urban poor.

There is strong evidence that the response has been most effective in countries where it built on existing programmes which sought to build resilience by strengthening national systems. Successive reductions to the UK aid budget in 2020 and 2021, however, reduced the overall scale, reach and flexibility of the UK’s COVID-19 response. Reducing funding for UN-managed Country-Based Pooled Funds, for example, diminished their capacity to support the COVID-19 response at a critical time. The September 2020 merger of DFID and the Foreign and Commonwealth Office (FCO) into FCDO also came at an inopportune time in the pandemic, taking staff attention away from the pandemic response.

We award a green-amber score for effectiveness, in recognition of a substantial contribution to saving lives and reducing suffering during the pandemic.

Conclusions and recommendations

Overall, we find that the UK’s humanitarian response to the COVID-19 pandemic was, for the most part, relevant, coherent and effective. The UK government deserves credit for its early recognition of the likely impacts of the pandemic in developing countries, and the speed with which it mobilised its response at both global and national levels. UK aid programmes demonstrated considerable flexibility in identifying opportunities to support national responses, particularly in respect of groups already receiving UK support before the crisis. However, in the absence of any new bilateral funding, the reliance on repurposing existing programmes left the UK poorly placed to meet the needs of groups made newly vulnerable by the pandemic.

There is no doubt that the large-scale reductions in the UK aid budget and the September 2020 merger of DFID and the FCO into FCDO came at an inopportune time in the pandemic, diverting staff time and attention from the pandemic response. The UK nonetheless succeeded in making a substantial contribution to saving lives and protecting livelihoods, meriting an overall green-amber score.

Recommendation 1

FCDO should undertake an after-action review of its COVID-19 response, to identify lessons on information management, management processes and programming options, to inform its future responses to complex, multi-country emergencies.

Recommendation 2

To fulfil its commitment to localising humanitarian response, FCDO should make long-term investments in building national disaster-response capacities, including mechanisms for directing funding to local non- state actors.

Recommendation 3

Building on its past investments in cash-based humanitarian support and national social protection systems, FCDO should invest in flexible social protection systems which help the most vulnerable in times of shock.

Introduction

On 11 March 2020, the World Health Organisation (WHO) declared the COVID-19 outbreak a global pandemic. Over the next two years, the pandemic precipitated the first truly global humanitarian emergency. It struck at a time when the world was already facing its highest level of humanitarian need in decades. At the beginning of 2020, at the onset of the pandemic, it was estimated that 168 million people were in need of humanitarian assistance across 53 countries. By the end of 2020, humanitarian need had risen to 243.8 million people across 75 countries, due to both the direct impacts of the pandemic and the extraordinary measures taken to control its spread.

The global humanitarian response has been unprecedented in scale and scope. As a major humanitarian donor, the UK has played a significant role. By 19 February 2020, even before the WHO announcement, the UK government had already committed £218.7 million from its central humanitarian funds to support vulnerable countries, initially through the UN, the Red Cross and other international agencies. There was also a significant reprogramming of bilateral aid, as the UK government sought to identify and support those most in need.

The COVID-19 pandemic coincided with considerable changes to the UK aid programme. In September 2020, the Department for International Development (DFID) was merged with the Foreign and Commonwealth Office (FCO) to become the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO). The UK aid budget was also reduced by £0.7 billion in 202011 due to the impact of the pandemic on the UK economy, and then further reduced by £3.5 billion in 2021 due to the government’s decision to reduce the aid spending target from 0.7% to 0.5% of UK gross national income.

The purpose of this review is to assess the UK’s humanitarian response to COVID-19, from the onset of the pandemic in January 2020 to December 2021, and to identify lessons to inform future responses to COVID-19 and other global health emergencies. It is part of a series of ICAI reviews looking at the UK’s aid response to COVID-19, including a rapid review of The UK aid response to COVID-19, published in October 2021, and a December 2020 information note: UK aid spending during COVID-19: management of procurement through suppliers. It draws on ICAI’s reviews of Management of the 0.7% ODA spending target, published in November 2020, and Management of the 0.7% ODA spending target in 2020, published in May 2021. This review also complements work undertaken by the National Audit Office, including a recently published study on reductions to the UK aid budget in 2021 and a series of reports on the UK government’s response to COVID-19.

This review focuses on emergency support for populations in humanitarian need as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic. It assesses how well the UK identified and prioritised those most vulnerable to the pandemic, the effectiveness of the support provided, and how well the UK worked with other stakeholders at global and country levels. It covers the UK’s response both to the direct impacts of the pandemic on public health, and to the indirect impacts – principally, the effects of social distancing regimes, curfews and other measures taken to contain the virus on vulnerable populations, including those already dependent on humanitarian support. It looks at contributions at the global level and in six case study countries: Bangladesh, Ethiopia, Jordan, Kenya, Nepal and Yemen. It does not cover vaccine development and distribution, which was covered in the October 2021 rapid review.

The review is built around the evaluation criteria of relevance, coherence and effectiveness. It addresses the questions and sub-questions set out in Table 1.

This review covers the work of DFID for the period up to its merger with the FCO on 2 September 2020, and thereafter the work of FCDO, which took over responsibility for ongoing DFID programmes and activities. In this report, the term “the department” refers to DFID before the merger and to FCDO thereafter.

Table 1: Our review questions

| Review criteria and questions | Sub-questions |

|---|---|

| 1. Relevance: How well did the UK government prioritise its humanitarian response to COVID-19? | • To what extent were funding allocations guided by evidence on the impacts of the pandemic on vulnerable populations and emerging evidence of effective mitigation measures? • To what extent did the UK government support consultation with affected populations and seek to address community priorities in the design of its response? • To what extent did the response reflect relevant principles from the Grand Bargain and the triple nexus? |

| 2. Coherence: To what extent has the UK supported a coherent humanitarian response to COVID-19? | • To what extent did UK participation in joint mechanisms, advocacy and influencing work with multilaterals, other donors and partner country governments support a coherent and coordinated humanitarian response to the pandemic? • To what extent was the UK’s humanitarian response coherent within its overseas network and departments? |

| 3. Effectiveness: To what extent has the UK humanitarian response to COVID-19 saved lives, reduced suffering and helped affected communities to build resilience? | • To what extent did the UK aid response succeed in reaching vulnerable people, including marginalised groups? • To what extent has UK support helped to increase the resilience of partner countries and affected communities to future health emergencies? |

Methodology

Methods

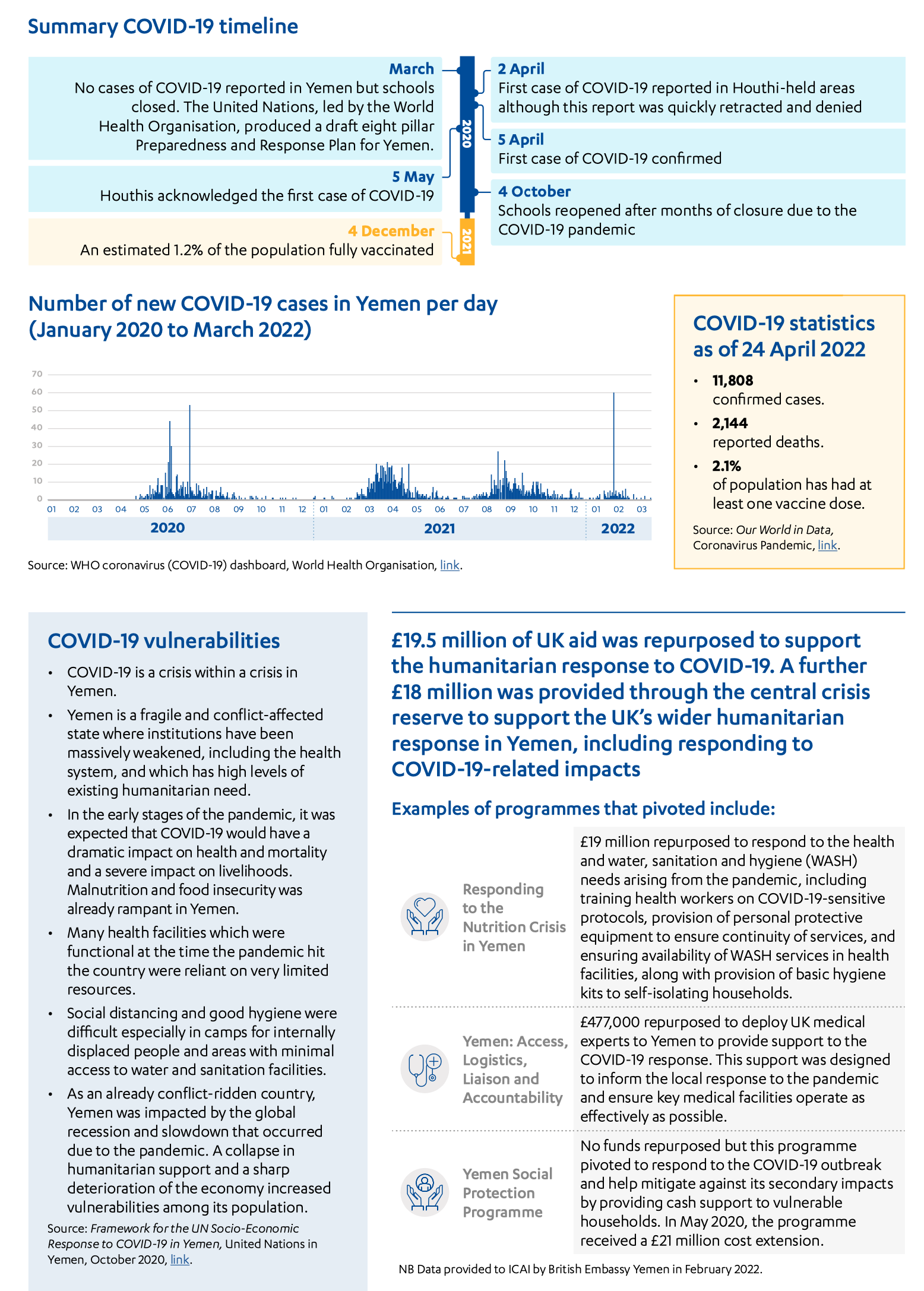

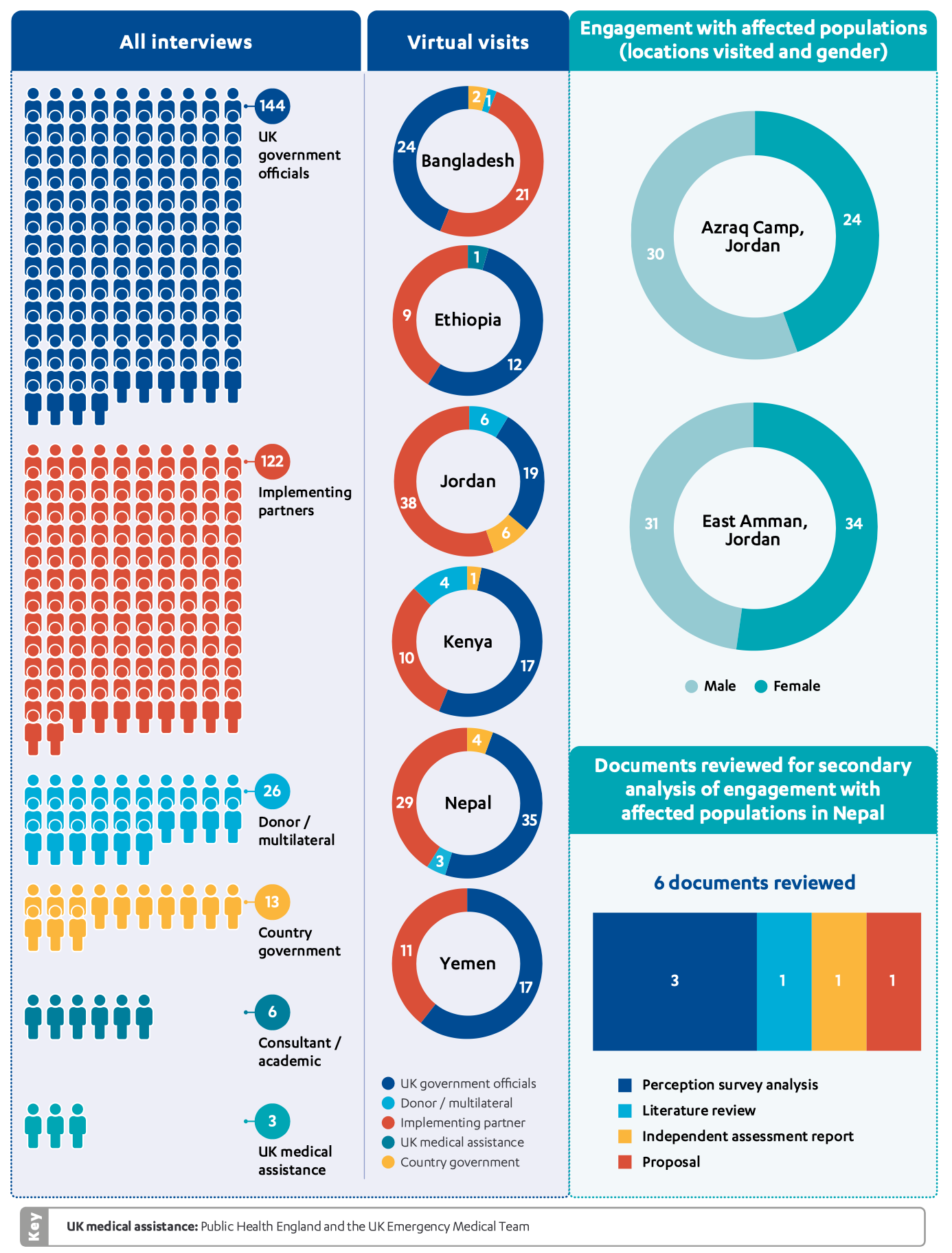

The review used the combination of methods shown in Figure 1 to answer the review questions and to provide a sufficient level of triangulation to ensure robust findings.

Figure 1: Summary of methodological elements of the review

[1] The Ethiopia country case study was changed to a light-touch country case study due to the state of emergency declared in Ethiopia in November 2021.

- Literature review: We conducted a review of relevant peer-reviewed and grey literature. The literature review provides background on the global humanitarian response to COVID-19 and outlines prior knowledge on humanitarian responses to epidemics and pandemics, helping us assess whether the UK’s actions were evidence-based. It helps to contextualise UK government actions alongside those of other donors and the broader humanitarian system.

- Strategic review: We assessed how well the UK informed itself about the humanitarian consequences of the unfolding pandemic, and reviewed the strategies, policies and guidance relevant to the UK response. We also reviewed the financing instruments used to support the UK’s emergency response to the COVID-19 pandemic.

- Global response review: We reviewed the objectives and achievements of the UK contributions to the global humanitarian response to COVID-19 during the period from January 2020 to August 2021. We assessed the UK’s coordination with other actors and processes, and the significance of its influencing efforts in promoting global coherence. Evidence for the global response review drew on DFID and FCDO programme documents, strategies and key informant interviews with UK government officials and global partners.

- Country case studies: We reviewed the UK’s emergency response to COVID-19 in six case study countries: Bangladesh, Ethiopia, Jordan, Kenya, Nepal and Yemen. The Jordan case study was selected for a more in-depth, in-person country visit and citizen engagement as COVID-19 regulations at the time of our research allowed travel to the country. In each case study, we assessed the UK’s humanitarian response at the portfolio level, and the extent to which COVID-19-related programming and activities achieved their objectives.

- Engagement with affected populations: We undertook consultations with affected populations in Jordan, and secondary analysis of consultations with affected populations in Nepal. In-person consultations, including interviews and focus groups, were undertaken in Jordan by a national partner, observing all COVID-19 regulations. These focused on vulnerable groups targeted by UK aid programmes, and whether the UK’s interventions were relevant to their needs and priorities.

- Academic roundtable: We held a roundtable with six independent experts to identify good practice to inform our assessment.

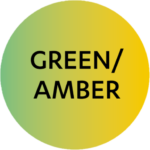

Figure 2: Sampling approach for case study countries

* Based on management data provided to ICAI by FCDO for calendar year 2020. All countries must meet this criterion.

** For direct impacts we took into account reported COVID-19 caseload and deaths per one million of the population and for secondary impacts we included World Bank data on percentage change in national unemployment rates between 2019 and 2020 as a proxy for livelihoods impacts, as well as FCDO reporting on country vulnerability to COVID-19 as of December 2020. World Bank unemployment data are not available for Yemen, and COVID-19 mortality rates have stayed relatively low due to the country’s young population. Yemen was nonetheless included in the sample due to its extremely high levels of humanitarian need (over 80% of the population) and the difficulties of mounting an effective COVID-19 response in an insecure context.

*** Based on Global Humanitarian Overview 2020 data. See Global humanitarian overview 2020, United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs, 2019, link.

Figure 3: Breakdown of stakeholder interviews, country case studies and engagement with affected populations

Box 1: Limitations to our methodology

- Scope: The humanitarian impacts of COVID-19 were highly varied across country contexts. To capture the breadth of the UK response, we undertook six country case studies, a higher number than usual in ICAI reviews. However, our findings may not be fully representative of the effectiveness of the UK response around the world.

- Disaggregating the COVID-19 response: The UK’s initial response to COVID-19 included new central funding and adaptation of existing programmes to meet pandemic-related needs at country level. Over the review period, however, the UK’s COVID-19 response was progressively mainstreamed into existing programmes, making it more difficult to identify COVID-19-specific results.

- COVID-19: The pandemic limited our ability to travel to and within partner countries. Except for our visit to Jordan, all country case studies were conducted remotely. All other interviews, including with FCDO staff in London, were conducted virtually.

- Ethiopia conflict: Escalating conflict in the Tigray region of Ethiopia in late 2021 led us to substitute a planned in-depth case study with a lighter-touch case study, and to cancel our planned engagement with affected populations. Secondary analysis of affected population engagement undertaken by others in Nepal was included as an alternative method of incorporating citizen voice into the review.

Background

The COVID-19 pandemic has exacerbated existing humanitarian needs and contributed to rising humanitarian needs globally

Humanitarian need has risen sharply over the last decade, driven by increases in armed conflict, natural disasters, extreme weather, food insecurity, displacement and forced migration. At the end of 2019, 79.5 million people were forcibly displaced from their homes worldwide because of conflict, persecution, violence, human rights violations and disasters. Before the COVID-19 pandemic was declared, the UN projected that 168 million people globally would be in need of humanitarian assistance during 2020, the highest number in decades. Despite this, global humanitarian funding had dropped by 5%, from $31.2 billion in 2018 to $29.6 billion in 2019 (the first fall since 2012), with half of the 20 largest humanitarian donors reducing their contributions.

Against this backdrop, the pandemic presented a major new challenge. Social distancing regimes, movement restrictions and travel bans pushed vulnerable people in many countries into crisis situations, while disrupting the delivery of humanitarian support to those already in crisis. By December 2020, 243.8 million people across 75 countries were identified as in need of humanitarian assistance – an increase of 75.8 million people (45%) from pre-pandemic projections.

In July 2020, the UN warned that the pandemic would increase poverty and inequality, with the most disadvantaged individuals and groups likely to be worst affected (see Box 2). Our engagement with affected populations in Jordan confirmed that the COVID-19 pandemic intensified existing pressures on vulnerable populations, including Syrian refugees and Jordanian host communities.

We don’t have money to buy food or anything because my husband was out of work because his workplace is very remote and he can’t go there and return before lockdown.

Jordanian woman from a vulnerable household, East Amman, Jordan

We suffered financially during the lockdown; we didn’t have enough money to buy basics like food, so we borrowed money and accumulated debts, which we started to pay off after lockdown was lifted and we are still in debt now. We don’t have electricity in the house now, because we couldn’t pay off the accumulated electricity bills. My husband works occasionally on odd jobs, but we are struggling to make ends meet.

Non-Jordanian refugee woman, East Amman, Jordan

The pandemic presented a disproportionate burden on and threat to women and girls, in areas such as health, livelihoods and personal security. Women workers were over-represented in the sectors hardest hit by lockdown measures, such as hospitality and retail, leading to loss of jobs and income. Women and girls also faced an increased burden of unpaid care and domestic work, as well as sharp rises in domestic violence. Furthermore, women have faced adverse sexual and reproductive health impacts, including lack of access to skilled healthcare, unwanted pregnancy and unsupervised abortions. It is also significant that COVID-19 infection rates were three times higher among female healthcare workers than for their male counterparts.

Box 2: UN Vulnerability Assessment, July 2020

In July 2020, as the pandemic was spreading around the world, the UN reviewed and updated its Global Humanitarian Response Plan. It projected that COVID-19 would:

- Increase the number of people living in extreme poverty by 71-100 million people.

- Deepen the global hunger crisis, with an additional 121 million people in urgent need of food assistance.

- Disrupt essential health and other services, causing up to 6,000 children to die every day from preventable causes between July and December 2020.

- Dramatically increase gender-based violence.

- Increase the vulnerability of refugees, asylum seekers, internally displaced people and migrants, given that these groups already face greater difficulty accessing essential health and other services and are often excluded from national social protection mechanisms.

Vulnerability also varied by region and context. Social and economic factors influenced the transmissibility of the virus, and there were wide gaps in national testing and treatment capacity. In countries already facing humanitarian crises, the COVID-19 pandemic compounded existing challenges. Conflicts and natural disasters continued alongside the pandemic over the course of 2020 and 2021, in many contexts posing a more acute risk to vulnerable populations than the pandemic itself. At the onset of the pandemic, the UN was clear that development partners should continue to see existing humanitarian needs as “an utmost priority”.

In fragile humanitarian contexts, the COVID-19 pandemic is creating new vulnerabilities for people who are already most at risk. We now face a crisis on top of a crisis with worsening poverty and food insecurity alongside crippling economic conditions and a lack of public health services, safe water, sanitation and hygiene.

Jagan Chapagain, International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies Secretary General, May 2020, link.

The global humanitarian response to the pandemic

On 28 March 2020, the UN launched the Global Humanitarian Response Plan (GHRP), its first ever global humanitarian appeal, for $2 billion (£1.4 billion), to support the humanitarian response to the pandemic. The GHRP brought together appeals from multiple UN agencies, including the World Food Programme, World Health Organisation (WHO), International Organisation for Migration, United Nations Development Programme, United Nations Population Fund, United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, United Nations Children’s Fund and United Nations Human Settlement Programme, as well as the Red Cross and international non-governmental organisations. The GHRP funding requirement was later revised upwards to $10.3 billion (£7.6 billion), covering 63 countries. As of 15 February 2021, funding for the GHRP had reached $3.73 billion (£2.7 billion), only 36.2% of the total requirement.

The GHRP had three strategic objectives:

- Contain the spread of the COVID-19 pandemic and decrease morbidity and mortality.

- Decrease the deterioration of human assets and rights, social cohesion and livelihoods.

- Protect, assist and advocate for refugees, internally displaced people, migrants and host communities particularly vulnerable to the pandemic.

The International Red Cross and Red Crescent also launched a collective global appeal, on 26 March 2020, for $823 million (£601 million). This funding requirement was revised upwards in May 2020 to $3.2 billion (£2.3 billion). It focused on measures to contain the spread of the virus, while at the same time seeking to protect and support those most vulnerable to the effects of social distancing and other public health measures.

The UK’s humanitarian response to COVID-19

The UK government launched its central humanitarian response to COVID-19 before WHO declared COVID-19 a global pandemic. By 19 February 2020, DFID’s central humanitarian team had developed a business case for the ‘COVID-19 outbreak – UK response’ that allocated £218.7 million in new UK funding to support the global response (see Table 2). The UK’s central humanitarian response to the COVID-19 pandemic was entirely committed by February 2020. It had three strategic objectives:

- Contain or delay the COVID-19 outbreak in the most vulnerable countries.

- Mitigate the secondary health and humanitarian impacts of COVID-19.

- Support UN leadership and coordination to ensure fast and effective global and national responses.

The UK government also went through an extensive process of adapting or ‘pivoting’ existing bilateral programmes to respond to the pandemic. On 24 March 2020, DFID instructed country teams and other aid-spending departments to reprioritise their programmes. As described in ICAI’s rapid review of the UK aid response to COVID-19, programmes were classified into three priority levels: gold (drive), silver (manage) and bronze (pause). The COVID-19 response and ongoing humanitarian operations were ranked as gold. The UK’s overall humanitarian expenditure (including core contributions to multilateral agencies) nonetheless fell by 25.8% in 2020, compared to the previous year. This reduction was linked to the overall UK aid budget being reduced in line with falling UK gross national income as a result of the pandemic.

Findings

In this section, we assess the relevance, coherence and effectiveness of the UK’s humanitarian response to the COVID-19 pandemic between January 2020 and December 2021.

Relevance: How well did the UK government prioritise its humanitarian response to COVID-19?

The UK’s early, flexible contribution through the international humanitarian system was a sound choice

The UK government was quick to realise the threat that COVID-19 posed to developing countries, establishing a watching brief on the virus even before the World Health Organisation (WHO) declared a global pandemic on 11 March 2020. Regular situation reports and scientific updates, including Department for International Development (DFID) COVID-19 SitReps, UK Emergency Medical Team SitReps, and reports on epidemiological modelling and emerging evidence from DFID’s Research and Evidence Division, were introduced on 1 February 2020. This was followed by the introduction of country-level vulnerability reporting from 12 February 2020.

Although the UK’s initial response was allocated before the full impacts of the pandemic were known, early evidence indicated that the COVID-19 outbreak would quickly reach global scale and that its impacts would be multisectoral, affecting not just public health but also health systems, economies, livelihoods, food security, education and human rights. In interviews, Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO) staff recalled a rapidly evolving environment, where urgent decisions had to be made on the basis of reasonable projections from limited data.

The department’s early decisions on its central humanitarian response were enabled by a ‘no regrets’ approach to decision-making – that is, in the face of uncertainties over the pandemic and its impacts, it prioritised actions that were likely to offer benefits to those targeted in any scenario, rather than delaying the response until more data were available. This reflected the wider departmental approach to the COVID-19 response. The use of existing partners and funding mechanisms also facilitated a rapid response.

By 19 February 2020, DFID’s central humanitarian team had developed a business case for its response that allocated £218.7 million towards the global humanitarian response (see Table 2). The majority of this funding was not earmarked for specific purposes or geographical areas, to give the global humanitarian system flexibility to respond to a rapidly evolving crisis. While initial decisions on funding to UN agencies predated the Global Humanitarian Response Plan (GHRP), led by the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA), the GHRP later became the framework against which UK funding to UN agencies was reported. The GHRP was intended to help the UN achieve scale and reach the most vulnerable. Similarly, early funding to the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies and International Committee of the Red Cross was incorporated into the Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement’s consolidated global appeal.

We find that the decision to provide an early, flexible and substantial contribution to the global humanitarian system was well justified. Given the potential scale of the crisis and uncertainties about its geographical spread, the UK’s flexible contribution enabled resources to be allocated rapidly to the most acute needs as they emerged. In interviews, multilateral agencies expressed their appreciation for the UK’s swift and flexible funding approach at the beginning of the pandemic. This is consistent with good humanitarian funding practice.

Table 2: The central humanitarian response

| Funding stream | Purpose | UK funding |

|---|---|---|

| World Health Organisation (WHO) | Address the primary impacts of COVID-19 and provide strategic global leadership of the response | £72 million |

| United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) | Lead on global humanitarian action for COVID-19 for children | £20 million |

| United Nations Refugee Agency (UNHCR) | Lead on COVID-19 health preparedness in camps and settlements | £20 million |

| World Food Programme (WFP) | Sustain the global response and support the global supply chain and humanitarian logistics | £15 million |

| United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) | Strengthen local and national health systems to maintain access to life-saving sexual and reproductive health and gender-based violence services | £10 million |

| International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (IFRC) | Coordinate with all National Societies to lead a community-level response* | £36 million |

| International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) | Adapt existing humanitarian programmes across all sectors to better respond to the impacts of COVID-19 | £17 million |

| British Red Cross | Provide support to National Societies including official development assistance-eligible British overseas branches in St Helena and Montserrat | £2 million |

| Rapid Response Facility (RRF) | Provide direct funding to non-governmental organisations (NGOs) to support preparedness and response to direct and indirect impacts of COVID-19 on the most vulnerable individuals and communities | £18 million |

| Humanitarian 2 Humanitarian Network (H2H) | Provide small grants to NGOs for niche services, including communication, countering misinformation, information management and training, and local capacity-building | £2 million |

| Monitoring, Evaluation, Learning and Research | Learning and Research Commission an evaluability assessment to support evaluation and evidence decision-making | £2 million |

| Emergency Medical Team (EMT) | UK experts advising and working with WHO and health ministries to prepare national health systems for COVID-19, including by setting up field treatment centres | £1.7 million |

| UK aircraft support to UN Humanitarian Response | Use of UK military aircraft to support the UN’s humanitarian response | £1.2 million |

| UN Standby Partnerships Rapid Deployment | Rapid deployment of specialist short-term surge personnel to support the capacity of UN agencies | £1 million |

| Humanitarian and Stabilisation Operations under an existing contract Team deployments | Specialist expertise to support the UK response to COVID-19 £750,000 | £750,000 |

| Personal protective equipment (PPE) procurement | PPE procurement to equip UK humanitarian responders and support the Overseas Territories of St Helena and Ascension | £55,200 |

| Total | £218.7 million | |

* The International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (IFRC) is made up of 192 National Societies, which are each made up of a network of community-based volunteers and staff who provide a wide variety of services.

The UK’s direct humanitarian response was also supported by earlier funding to the UN’s Central Emergency Response Fund (CERF), a central fund established to respond to sudden crises and fill gaps in humanitarian assistance. In December 2019, the UK had provided a substantial annual contribution of £300 million to the CERF, which UN partners told us had facilitated a swift response to COVID-19.

Funding choices were guided by past learning and emerging evidence

The UK’s pandemic response drew on learning and experience from previous humanitarian crises and global health emergencies, including learning from the 2003 SARS outbreak, the 2004 South East Asia tsunami and the 2014-16 West Africa Ebola outbreak. For example, experience from the Ebola outbreak had shown that the indirect social and economic impacts from an epidemic can be more severe than the direct health impacts.

Much of this learning was in the form of tacit knowledge and experience within the department, which proved of considerable value. ICAI’s October 2021 rapid review of the UK aid response to COVID-1937 found that staff with experience of past crises had drawn on their knowledge to guide the COVID-19 response. Our interviews across the department confirmed the importance of this institutional knowledge. We heard concerns, however, that this knowledge was at risk of being lost as a result of high staff turnover since the merger of DFID and the Foreign and Commonwealth Office (FCO) into FCDO.

The department was quick to put in place mechanisms to collect emerging evidence on the pandemic, drawing on existing networks and relationships. Multilateral agencies and other implementing partners were asked to assess and report back on likely COVID-19 impacts, both centrally and at country level. Across the department, various teams drew together real-time data and evidence to track the impacts of the unfolding pandemic. The central humanitarian team compiled and analysed much of the data being collected. They also worked closely with OCHA on the design of the global appeal, with a ‘red team’ of advisers from different professional backgrounds reviewing and challenging funding requests.

At country level, the UK looked systematically for opportunities to adapt existing programmes

No new funding was provided to support the UK’s humanitarian response to COVID 19 at country level. However, the department issued instructions to all spending units – including country teams – to identify opportunities to adapt existing programmes to support the response. Under the reprioritisation exercise initiated in March 2020, COVID-19 response measures, including health and humanitarian interventions and fast-disbursing financial aid and social protection, were accorded the highest priority, alongside ongoing humanitarian operations. All other programmes were tasked with identifying how and where they could repurpose funds or activities to support the COVID-19 response. Decentralised decision-making by country teams helped ensure the relevance of the response to country needs.

The department drew on past learning and emerging evidence to update its thematic guidance, including on health, social protection and humanitarian programming, to help country offices address the needs of vulnerable groups. Programme pivots were also informed by evidence shared by national governments, other donors and implementing partners in-country. This approach was in line with the global literature, which highlights that understanding local contexts and cultures was a key lesson from the Ebola humanitarian response.

Among our case study countries, most country teams had started to plan their programme adaptations before receiving formal instruction to do so from headquarters. In Bangladesh, the team had developed early COVID-19 impact scenarios and programme responses. In Nepal, other donors confirmed that the UK had foreseen the risks posed by COVID-19 at an early stage and was quick to review which programme activities could pivot to support the most vulnerable.

We also saw examples of innovative approaches to data and evidence generation. In Yemen, the UK partnered with the London School of Health and Tropical Medicine and Catapult (a UK-based company) to estimate excess mortality (that is, how many more people had died than usual) by using satellite imagery to monitor burial sites, recording the number of graves being dug. In Bangladesh, the UK Public Health Rapid Support Team worked with WHO to assess COVID-19 infection rates in Cox’s Bazar, home to the world’s largest refugee camp. In Kenya, the UK-funded non-governmental organisation (NGO) Shujaaz mobilised youth through comic books and social media to gather data on COVID-19 spread and impacts. We heard reports of these data being used by Kenyan members of parliament, UN actors and other donors.

The UK response primarily targeted those already receiving assistance before the pandemic, missing some newly vulnerable groups

The UK’s central humanitarian business case for the COVID-19 response predicted that several groups were likely to be acutely vulnerable to the direct and indirect impacts of COVID-19, including women (given their roles as frontline health and social care workers and as family caregivers), people with disabilities and pre-existing medical conditions, older people, the urban poor, migrants, internally displaced people and refugees. It also recognised that certain groups were more likely to be excluded from national health systems, compounding their vulnerabilities. These included individuals from the LGBT+ community, sex workers, forcibly displaced people, and ethnic and religious minorities.

My husband was very frustrated and angry because he wasn’t working during the lockdown, so he would take his anger out on all of us sometimes. We didn’t have the money to buy the basics like food and the kids didn’t study well during the online classes. All of these things had their toll on us mentally and psychologically.

Female, East Amman, Jordan

We faced a lot of difficulties. We’re barely paying the rent, how can we afford to get an internet connection? I need to buy internet cards every month for my phone so that my kids can

learn online.

Male, East Amman, Jordan

The UK’s COVID-19 response at country level (that is, through its bilateral programmes) focused primarily on groups that were already receiving assistance before the pandemic. We found that country teams did not engage in systematic and rigorous assessment of the needs of groups made newly vulnerable by the pandemic. These included the elderly, sex workers, disabled people, people living with HIV/AIDS, people with mental health conditions and the LGBT+ community.

While pivoting existing programmes enhanced the speed of the UK’s response, it also reduced the UK’s ability to identify and target the newly vulnerable. We found that the elderly and people with co- morbidities were not prioritised in any of our case study countries, despite evidence showing that they would likely be most at risk of morbidity and death from the COVID-19 virus. Initial research in China, for example, found that the COVID-19 mortality rate was 8% among those aged 70-79 years, compared to 2.3% for the general population, and this figure rose to 15% among those aged 80 years and over. We found that other groups were also underserved by the UK’s COVID-19 response, including people displaced by conflict, migrant workers in Jordan, Ethiopia, Kenya and Yemen, and the urban poor in Ethiopia.

There were some positive exceptions, although on a fairly small scale. In Bangladesh and Kenya, short- term cash support schemes were set up under existing programmes to support the urban poor, while some support was provided to returning economic migrants in both Ethiopia and Nepal. In Ethiopia, the UK reprogrammed £1 million under the Ethiopian Migration Programme (£170 million; 2016-23), implemented by the Danish Refugee Council, to assist returning migrants with food, non-food items and protection. In Jordan, UK assistance through a top-up to the National Aid Fund reached some informal sector workers, alongside other vulnerable groups.

Nepal stands out as a country where the UK has been particularly active in seeking to apply emerging evidence on chronic and acute needs to identify the groups most vulnerable to the impacts of COVID-19. Community engagement under the Social Accountability in the Health Sector programme, for example, identified a lack of women’s sanitation facilities at border isolation posts, which the UK then worked with its partners to rectify. Through its work with WHO, the UK government has also provided rehabilitation support for people living with disabilities who contracted COVID-19, as well as for people suffering from the long-term effects of COVID-19, including the provision of assistive devices.

Where the UK government was not directly involved in supporting newly vulnerable groups, there is evidence that it advocated for their inclusion in national response plans. In Jordan, for example, the UK government contributed to a study on informal settlements, seeking to identify people unable to access existing social protection mechanisms through UN agencies or the National Aid Fund. The study highlighted informal migrant workers and those on the margins of the economy as groups in need of assistance. The UK was unable to support these groups directly, but lobbied for the World Food Programme (WFP) to do so. It also supported advocacy through the regionally managed Work in Freedom Programme (£13 million; 2018-23), lobbying for migrant workers to receive social security entitlements in Jordan rather than on return to their countries of origin. Overall, however, efforts to support stranded economic migrants (foreign nationals working in Jordan, often without clear legal status) had limited effect.

The UK’s ability to support the continued COVID-19 response has been constrained by reductions in the aid budget

While the UK government has continued to collect evidence on the unfolding impacts of the pandemic around the world, its ability to adapt its support in response to emerging needs has been constrained by successive reductions to the aid budget. In 2020, the UK aid budget was reduced by £0.7 billion due to the impact of COVID-19 on the UK economy. Government officials had initially planned for a package of up to £2.94 billion in-year reductions to programmes in 2020 but this was later revised. Further reductions of £3.5 billion were undertaken in 2021 as a result of the government’s decision to reduce the aid target to 0.5% of gross national income.

No substantial new COVID-19 response activities were initiated after these budget reductions. While we identified some instances of the UK continuing to adapt its COVID-19 response after the initial set of programme pivots, these changes were small in scale. We were consistently informed by FCDO staff in the UK and in-country that budget reductions had reduced the UK’s flexibility to respond to emerging evidence on vulnerability to COVID-19.

These reductions also meant that a planned second tranche of central humanitarian funding was not provided to support the COVID-19 response. We were informed by FCDO staff that this second tranche would have focused more explicitly on groups most in need of assistance. No central humanitarian funding has therefore been allocated for the COVID-19 response since February 2020.

The UK’s COVID-19 response has been integrated into other humanitarian activities

Throughout the pandemic response, the UK retained a strong focus on pre-existing humanitarian needs. In Yemen, the UK retained its existing humanitarian priorities, adapting its programmes to address COVID-19 risks and impacts. This was an appropriate response in a country where over 80% of the population was already in humanitarian need. A similar approach was employed in other countries, including Kenya and Ethiopia. During interviews, country partners generally agreed that the UK took the right approach in strengthening existing programming, rather than developing a parallel response.

As the pandemic progressed, it became clear that, in many contexts, the COVID-19 impacts were less catastrophic than initially anticipated, and often less critical than other humanitarian needs. Across our country case studies, with the exception of a severe second wave of COVID-19 in Nepal in May 2021, most worst-case scenarios did not come about. In Ethiopia, escalating conflict in the Tigray region towards the end of 2021 was a larger concern for vulnerable populations, while in Kenya, drought and desert locust invasion caused significant livelihood and food-security challenges.

The department therefore moved from an initial stand-alone COVID-19 response towards strengthening its broader humanitarian programmes against COVID-19 impacts. As one FCDO staff member put it, the response became “COVID-aware rather than COVID-focused.” This reflected the emerging evidence and was in line with approaches taken by other donors.

Consultation with affected populations has been limited throughout the response

The UK’s capacity to consult affected populations during the pandemic and adapt to their needs was limited by various factors, including the speed and scale of the initial response, COVID-19 travel restrictions, fear of inadvertently transmitting the virus, and the withdrawal of UK staff from affected countries. As a result, FCDO staff acknowledge that consultations were limited.

In view of the difficulties of engaging affected populations directly, the UK funded the Red Cross at the central level to include consultations in its programming and to share the data. Although this was done, the department lacked the time and resources to process and interpret the large volume of data that was received, and it was not systematically shared with country offices. For their part, country teams collected data from needs assessments carried out by other agencies, and regularly asked implementing partners for updated impact assessments.

Our own consultations in Jordan revealed that, while participants were glad of the UK’s support, they were not aware of any consultations. A study of the Jordan response confirms this, finding that most organisations did not consult with people expected to benefit from adaptation measures due to time pressures and not wanting to raise expectations. This was broadly the pattern across our case study countries, with some positive exceptions. In Jordan, the release of vouchers to refugees resulted in price rises in the designated grocery stores, which was addressed by shifting the WFP programme to allow cash deposits via personal bank accounts. In Bangladesh, consultation with affected populations by the NGO partner BRAC led to innovative approaches to COVID-19 testing in crowded settings, using open- air kiosks to maintain social distancing.

In the beginning, they gave us cheques which we could only use in the mall, and the mall increased prices. So after that, UNHCR changed the method and opened for us a bank account so we can withdraw money from the ATM.

Refugee woman, East Amman, Jordan

The UK made little progress on humanitarian reform commitments during the pandemic, although its response benefited from earlier reforms

At the 2016 World Humanitarian Summit, the UK signed up to a set of commitments for reforming the international humanitarian system, known as the Grand Bargain. These include increased use of cash for humanitarian support, rather than food or other items, directing more support through national and local responders (localisation), increased accountability to affected populations, and more coordination between humanitarian and development assistance. However, these are complex and challenging reforms, and the UK took the view that a global emergency was not the right context to take them forward.

The department already had a strong track record of aligning its humanitarian and development programming and providing humanitarian cash-based assistance. This provided a strong foundation for the UK’s pandemic response. Without a rigid separation between its humanitarian and development budgets, the UK was better placed than many other donors to deliver a cross-sectoral response. Across our case study countries, the UK set up COVID-19 joint response teams, involving health, livelihoods, social protection and humanitarian experts, to plan and implement the response. While programming to address emergency needs created by the pandemic was primarily humanitarian, the UK’s ability to adapt development programmes enabled a robust, multi-sectoral response. The Building Resilience in Ethiopia programme (£262 million; 2017-22), for example, pivoted to deliver infection prevention and control and sanitation measures in schools, churches, mosques and health facilities. The Jordan Compact Economic Opportunities Programme, implemented by the World Bank, pivoted to create home-based IT jobs.

However, as ICAI found in a 2018 review, the UK could have done more to support localisation (that is, increasing the share of support channelled through national and local responders). The Grand Bargain refers to national and local actors comprising governments, communities, Red Cross and Red Crescent National Societies and local civil society. We found that while the UK worked closely with national and local governments, no clear strategy for supporting localisation was included in its humanitarian response to COVID-19 and only limited support was provided through local NGOs and civil society organisations. Staff explained that the department was unwilling to take on the additional risks associated with localisation and lacked the capacity to manage multiple small grants to local responders. Country teams also focused on adapting existing delivery mechanisms, rather than creating new ones.

The UK’s work with national and sub-national governments built on past support for emergency preparedness and resilience. In Nepal, channelling aspects of the COVID-19 response through government was also part of a deliberate strategy to support the country’s ongoing transition to federalism (that is, a governance system that divides power and responsibility between central and regional government). In Bangladesh, Ethiopia and Nepal, the UK was supporting technical experts posted in the national ministry of health before the pandemic, who were able to support national counterparts to capture and analyse COVID-19 health data and design national health responses. The UK also supported the establishment and scale-up of COVID-19 testing laboratories in Bangladesh and Nepal, upgrading of primary health facilities and staff recruitment and training.

We found few examples of working with other local responders to support the COVID-19 response. Some measures were taken at the central level to facilitate funding of national NGOs, including a reduction in reporting requirements and a change to the rules to permit funding of their operating costs. However, this did not result in a higher proportion of support being channelled to local responders.

In Nepal, FCDO worked with local partners to deliver cash-for-work infrastructure projects, and provided capacity-building for national NGOs through the Strengthening Disaster Resilience Programme. In Kenya, the UK government set up a new project to support the national NGO Shujaaz to promote awareness of COVID-19 and encourage behaviour change among Kenya’s youth, although funding was channelled through an international NGO. However, these initiatives were small in scale, and the overall effort on localisation was inadequate.

Furthermore, NGO partners in several countries informed us that their relationships with FCDO had become more distant during the DFID/FCO merger and the UK budget reductions, with less dialogue, feedback and evidence sharing. FCDO country teams confirmed that the merger had led to a shift away from direct engagement with local responders, towards encouraging multilateral partners to support them.

Conclusions on relevance

The UK made an early and significant contribution to the international humanitarian response to COVID-19. In the period when little was known about the likely course of the pandemic, the use of unearmarked funding gave international humanitarian organisations the ability to respond rapidly and flexibly in an evolving context. The UK’s response drew on knowledge and experience from earlier epidemics, and the UK was quick to access and generate new data on COVID-19 risks and impacts. The reliance on existing programming channels, however, meant that groups made newly vulnerable by the pandemic were not always prioritised.

The pandemic offered limited opportunities for driving forward global humanitarian reform commitments. The UK did not channel more support through local responders, although it did continue to work closely with national and local governments.

We award the UK’s response a green-amber score for relevance, in recognition of a strong and rapid response in the early phase of the crisis.

Coherence: To what extent has the UK supported a coherent humanitarian response to COVID-19?

The UK set clear and appropriate objectives for its central response

The UK’s objectives for its central humanitarian response to COVID-19 focused on enabling the multilateral system to deliver an effective global response, reinforcing frontline support agencies. In our case study countries, the UK used its relationships with UN agencies and national governments to encourage them to prioritise the most vulnerable, with varying success. For example, in Ethiopia, the UK worked with partners to encourage the government to include refugees in its COVID-19 health response.

The UK’s early, unearmarked contributions to the humanitarian system helped promote coherence and coordination at the international level and proved to be an efficient way to get money and equipment to where it was most needed. This represented good quality humanitarian funding, enabling multilateral agencies to work with partners to direct funds rapidly to emerging needs and to fill gaps in humanitarian provision. The UK government placed trust in the global system and provided the flexible funding it needed to do its job.

The UK government contributed to the creation and design of the UN’s global appeal, the GHRP. It also provided 6.6% of the funds raised, making the UK the fourth-largest donor. The UK was the largest donor to the Red Cross Global Appeal, recognising its ability to access affected communities. Central support to the Red Cross was not connected to the UK’s country responses, however, resulting in a missed opportunity for collaboration and data sharing with UK country teams.

The UK played an important coordination role at country level

At country level, the UK actively supported coordination of the COVID-19 response. Various stakeholders told us that UK aid staff had helped to improve the coherence of national and sub-national responses to COVID-19. Where there were information gaps, the UK worked to develop and share reliable evidence, including drawing on centres of international expertise such as the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine and Johns Hopkins University.

Data and evidence collected and distributed across the department were used in several countries to inform the national response. In both Bangladesh and Ethiopia, the UK helped by providing epidemiological modelling. The Bangladesh Ministry of Health reported that its national health response drew on COVID-19 disease projections shared by the UK government. Stakeholders in Ethiopia informed us that the Ethiopian health minister had requested and applied COVID-19 impact projections provided by the UK government in planning the national response and informing district responses.

The UK also played a role in supporting COVID-19 information capture and management systems. In Nepal, for example, the UK supported the Ministry of Health in developing local health data capture, reporting and analysis systems. The UK was also noted for its role in supporting coordinated procurement of emergency oxygen, personal protective equipment (PPE) and ventilators in Nepal during the second wave of COVID-19, as well as its support to WFP to develop a central distribution mechanism for such supplies.

COVID-19 highlighted long-running coordination challenges within the UN system, including siloed working, duplication of effort and competition between agencies. In two case study countries, we were informed that UN agencies competed for position and funding, and failed to share timely and relevant information with other agencies. External stakeholders highlighted UK efforts to improve coordination and information sharing within the UN, including between humanitarian and development agencies.

The UK struggled with information overload

Despite its speed, the UK’s humanitarian response was generally well coordinated. At country level, UK trade, development and diplomatic staff worked closely together to plan the response. Country teams also nominated staff to coordinate information flows across humanitarian and development teams, and with central teams in London. For 40 countries identified as most vulnerable to the impacts of COVID-19, country teams were tasked with developing ‘country vulnerability plans’, which they reported on until the end of 2020.

However, the volume of information requested and shared between staff posted overseas and the central department was, at times, overwhelming, and could not be properly processed. Country teams informed us that they experienced ‘information overload’. We found that information was not systematically filtered, collated or summarised before being shared. Daily reporting requirements at the beginning of the pandemic also placed a huge burden on country teams, distracting them from programme delivery. FCDO staff said that the information generated was not always coherent or useful.

Mandatory drawdown of staff from overseas networks undermined coherence

As reported in ICAI’s rapid review of the UK aid response to COVID-19, the FCO (which held ‘duty of care’ for all UK government staff posted overseas) mandated the return of UK aid staff from 36 countries. At its peak, the drawdown saw some 300 staff removed from the overseas network, for an average of three to six months. This decision was based on a risk assessment of country medical services, law and order, the availability of food, fuel and other essentials, and national decisions on border closures. ICAI’s rapid review found, however, that there were alternative options which the UK could have pursued earlier to enable more staff to stay posted overseas.

The drawdown was highly disruptive of the pandemic response. FCDO officials in a number of countries told us that they were temporarily distracted from delivering essential activities as they moved into new accommodation and sought to balance childcare and homeschooling. Several UK aid staff told us that people were drawn down without any individual assessment of whether they could continue safely in their roles. Despite a stated goal of retaining health and humanitarian capacity in-country where possible, we found that health and humanitarian advisers were drawn down in some of our case study countries – often at the point when their support was most needed. ICAI’s rapid review of the UK’s COVID-19 response made the same finding across its three country case studies. By contrast, several implementing partners and other donors gave staff involved in the pandemic response the option of remaining in-country.

Conclusions on coherence

The UK’s contribution of early, flexible funding to the multilateral humanitarian system helped promote a coherent and coordinated response and was an efficient way to get money and equipment to where it was needed most. Through its bilateral programme, the UK also played an important role in promoting coordination and coherence for the COVID-19 response at country level.

The UK’s response was well coordinated across the department, although information demands on overseas networks were at times overwhelming, diverting time and focus away from implementing the response. This was made even more challenging by the drawdown of overseas staff at a critical time in the pandemic response, including the drawdown of health and humanitarian advisers.

Overall, despite some weaknesses, we have awarded the UK a green-amber score for coherence, in recognition of a strong UK contribution to coordination.

Effectiveness: To what extent has the UK humanitarian response to COVID-19 saved lives, reduced suffering and helped affected communities to build resilience?

The UK’s central humanitarian response undoubtedly saved lives and protected livelihoods

The UK’s rapid commitment of central funding to multilateral agencies contributed to the large-scale mobilisation of resources for vulnerable countries. In an unprecedented global emergency, the UK’s flexible funding enabled partner agencies to respond swiftly to global needs for equipment, logistics and life-saving activities.

So far, the evaluative evidence on the effectiveness of the multilateral response is limited, but a range of evaluations are underway or planned. In particular, the UK is supporting an Inter-Agency Standing Committee evaluation, due for publication in September 2022. However, the available evidence suggests that at least some aspects of the global humanitarian response were highly effective. The GHRP was the humanitarian community’s first ever global appeal, and demonstrated how quickly the international community could collaborate to tackle an emergency without borders.

UK funding to WHO supported the global health response, including healthcare for vulnerable communities and strengthening national health systems to respond to COVID-19. Support to the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) enabled the delivery of therapeutics, diagnostics and oxygen concentrators to vulnerable countries. UNICEF also led on global procurement of PPE, helping to reduce competition between countries and ease supply constraints. At a minimum, this protected the lives of key workers and enabled essential healthcare services to continue during the pandemic.

The UN also played a critical role in keeping global supply chains operational. WFP supported the transport of people and goods at a time when many commercial airlines had suspended operations. By December 2020, WFP had transported 28,000 people from 424 organisations to 68 destinations and delivered 145,500 cubic metres of medical and other supplies to 173 countries on behalf of 72 organisations.

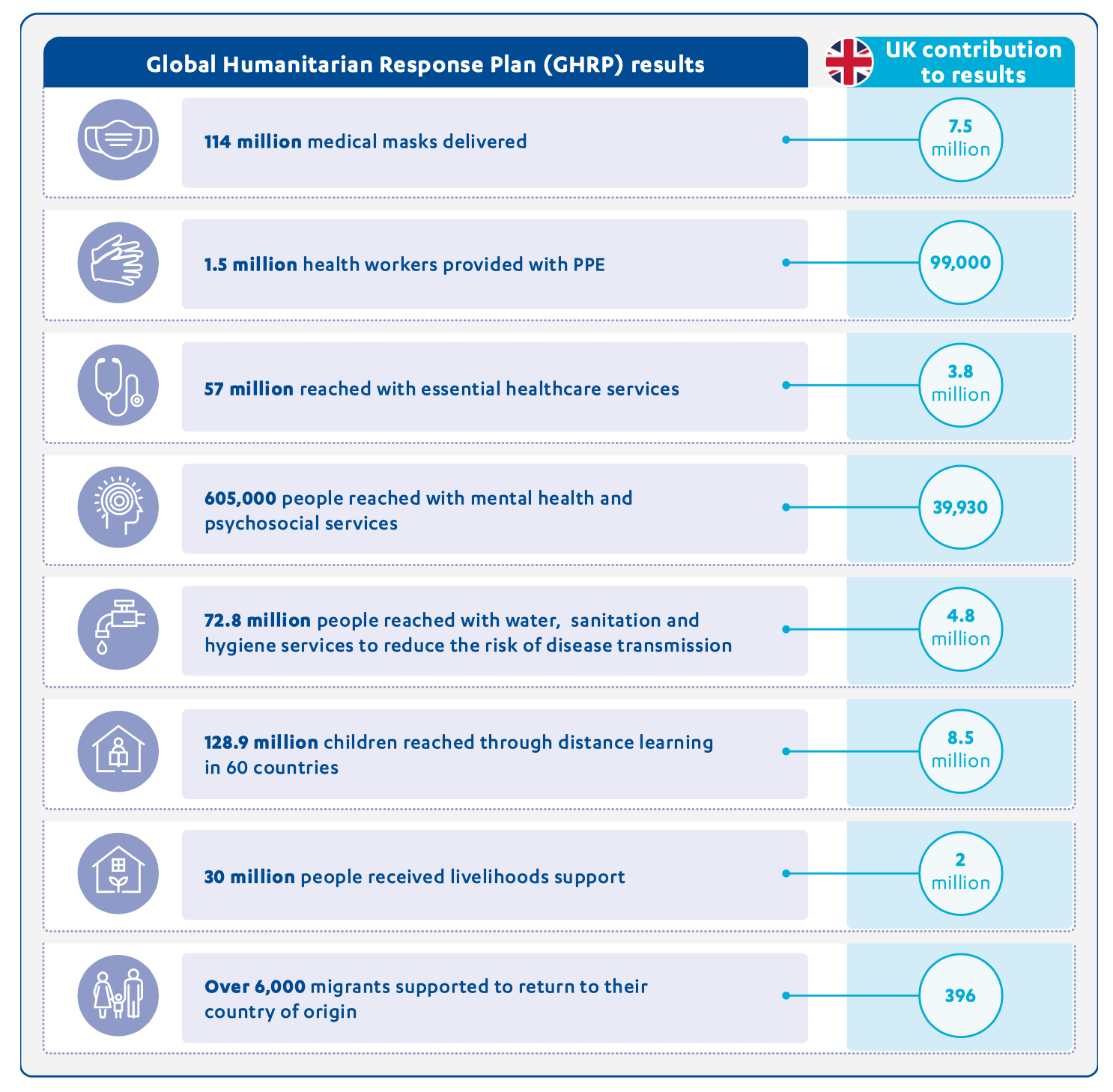

According to the latest GHRP reporting from OCHA, the UK provided 6.6% of total funding to the GHRP. We have applied this percentage to the overall results reported against the GHRP, summarised below in Figure 4.

Figure 4: GHRP results attributable to the UK’s contribution (as of December 2020)

Support via the Red Cross provided health, food, livelihoods and other support to vulnerable communities in 74 countries. This included health services for 8.4 million people, community water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH) activities for 106 million people, and livelihoods support for 4.2 million people. A focus on early infection prevention and control is also likely to have reduced morbidity and mortality among vulnerable groups.

The UK’s Rapid Response Facility (RRF) provides rapid funding to pre-registered NGOs for emergency assistance during the initial phase of new crises. As part of its COVID-19 response, the RRF provided hygiene kits to 773,370 people and food and other essential livelihoods assistance to 19,315 households.

The UK’s support for Emergency Medical Teams (EMTs) enabled the deployment of health experts to Ghana, Cambodia, Zambia, Burkina Faso, Bangladesh, South Africa, Chad, Lebanon and, more recently, to Armenia, Lesotho, Namibia and Botswana. This enhanced the capacity of national health systems to respond to COVID 19, and included introducing systems for prevention, testing, diagnosis, isolation and treatment. In Bangladesh, as part of the Rohingya response in Cox’s Bazar, UK EMTs had trained health workers, helped establish data capture and analysis systems, and boosted laboratory testing capacities.

Despite this results reporting, there are no indicators or targets against which to assess the overall effectiveness of the UK response. In interviews, both FCDO staff and multilateral partners stressed the difficulties involved in setting meaningful targets in a context of such uncertainty. We therefore cannot reach a conclusion as to whether the UK contribution achieved its intended results. We can, however, confirm that the UK’s assistance made an important contribution to the global response.

UK in-country programmes limited disease transmission and provided life-saving support

In all our case study countries, the UK built infection prevention and control measures into ongoing programmes, including support for handwashing, sanitiser and PPE, as well as new operational guidelines on social distancing. These efforts helped protect frontline workers and the vulnerable communities they served.

While we were able to confirm that UK support reached the target communities, the results were impossible to quantify. Many programme-level monitoring and evaluation activities were postponed during the emergency phase. Furthermore, as COVID-19 measures have been mainstreamed into wider programmes, the effects are more difficult to disaggregate. At the time of our review, no attempt had been made by FCDO to calculate how many vulnerable people had been reached through in-country programmes as part of its COVID-19 response.

A significant part of the UK response has focused on hygiene promotion and community awareness raising aimed at reducing the spread of COVID-19. In Ethiopia, UK support through UNICEF improved access to WASH services in 22 health centres. In Bangladesh, the UK supported the installation of 50,000 handwashing points, including in Cox’s Bazar, and distributed supplies such as soap to 61,807 people. The UK also targeted vulnerable urban communities, providing hygiene facilities in slums in 18 towns and cities. In Kenya, the UK’s work with UNICEF reached 21.2 million people with messaging on COVID-19 prevention. Over 200,000 refugees in Kenya were also reached with hygiene awareness campaigns, as well as 56% of Kenya’s youth (see Box 3). In Bangladesh, UK support reached over 3 million people with awareness raising and early warning messages.