The UK’s support to the World Bank’s International Development Association

Score

The International Development Association provides good value for money, as it aligns strongly with UK development priorities, leverages non-aid resources and influences development at scale across all low-income countries. However, it could do more to focus on climate change outcomes, to target the poorest, to engage citizens and to meet its own demanding social and environmental safeguard standards.

The World Bank’s International Development Association (IDA) is the world’s largest source of grants and low-interest loans for low-income countries, with annual commitments currently exceeding $30 billion. Two-thirds of IDA’s commitments are in sub-Saharan Africa and nearly two-fifths assist fragile states. Its operational scope stretches across a wide range of social and economic sectors, as well as addressing climate change and governance and providing macro-fiscal support. It likewise draws on a range and depth of specialised expertise, research and analysis capabilities beyond the reach of most bilateral donors acting alone.

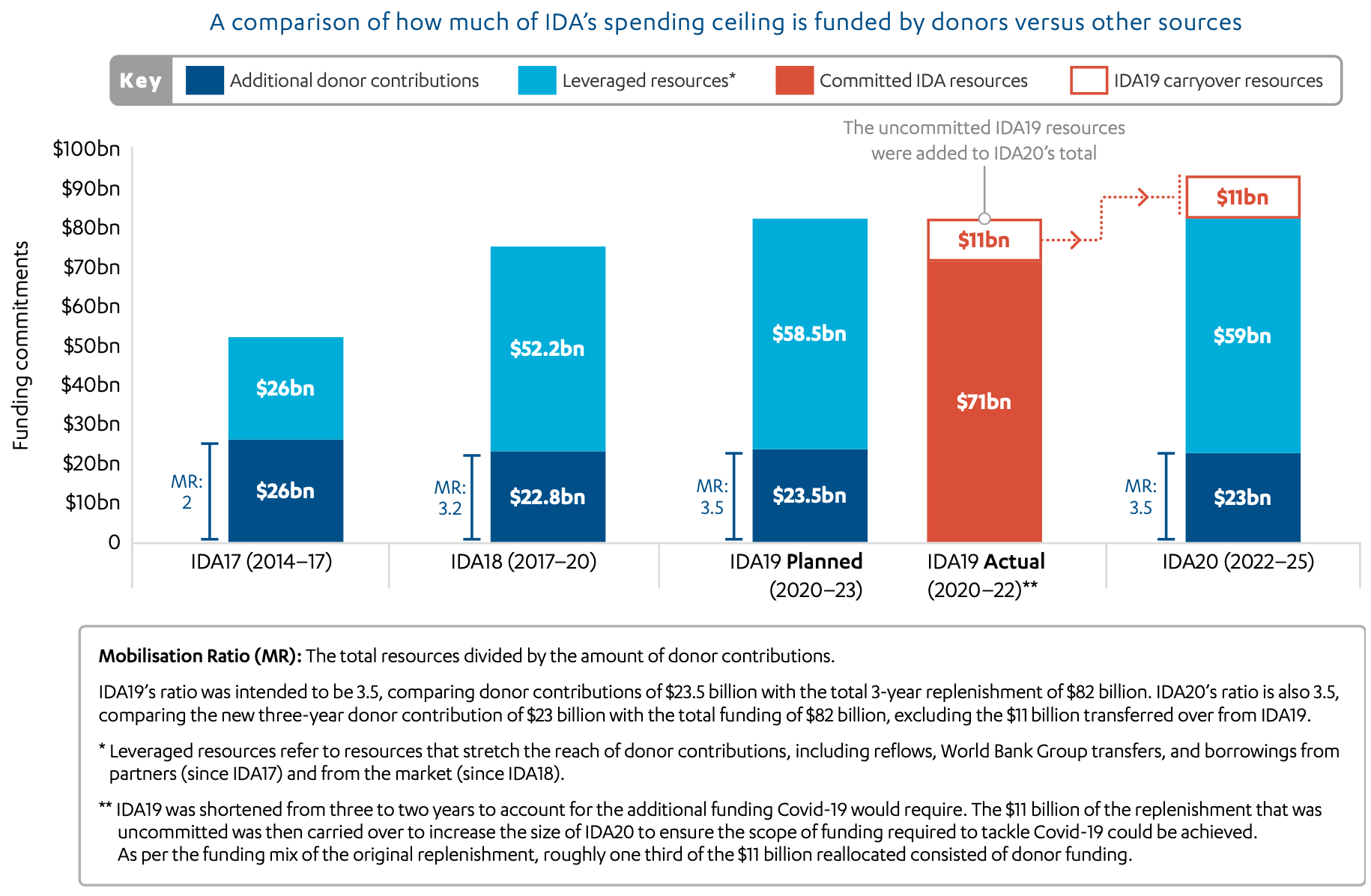

IDA’s funding ceiling is determined through triennial ‘replenishment’ processes, to which the UK and other donor governments are significant contributors. Roughly £1 in every £12 of UK aid was received by IDA over the past five years, and the UK has been IDA’s largest donor for over a decade. IDA’s funding model also enables it to mobilise a multiple – currently 3.5 times – of the sums contributed by its donors, by utilising internal World Bank Group (WBG) resources and (since 2018) borrowing from financial markets. As a result, IDA’s replenishment totals have risen rapidly in recent years, from $52 billion for 2014–17 to $93 billion for 2022–25.

IDA’s concentration on funding low-income countries, its increased funding for fragile states, its significant emphasis on promoting gender equality and its recent work on disability have all promoted its alignment with the strategic emphasis of UK aid. In recent years IDA has also increased its ambitions on supporting its clients to manage the effects of climate change and crises, emergent priorities for the UK’s aid. IDA works mainly with, and through, national governments, which generally express satisfaction with IDA operations and practices. However, IDA also sets itself demanding rules for promoting civil society engagement and consulting citizens potentially affected by its interventions; these are still work in progress.

IDA’s headline project effectiveness on its own measures, verified by its Independent Evaluation Group – which undertakes evaluations independent of Bank management, and reports to the Boards of the WBG – is strong and on an upward trend. IDA also has a comprehensive results management framework which, among other indicators, tracks a range of intermediate outcomes, such as the number of deliveries attended by skilled health personnel. Impact evaluations on IDA programmes reveal more about their broader development impact, but these are not feasible for all types of operations. It is easier to identify IDA’s contributions to high-level development outcomes than to attribute them conclusively to its interventions.

IDA’s project performance seems to be improving in fragile states, and a new suite of strategy and diagnostic tools has recently been introduced to support these operations. IDA has effectively deepened its emphasis on promoting gender equality and has begun to design and deliver more disability-inclusive operations. However, a more comprehensive approach to inclusion and implementing the Bank’s strategic goal of ‘shared prosperity’ is yet to develop. IDA responded to the COVID-19 pandemic rapidly, flexibly and at scale, confounding earlier perceptions that the World Bank was slow-moving and bureaucratic.

Over the last three decades increasingly demanding standards have been set for the Bank for protecting the environmental and social conditions of the communities it affects. We found significant room for improvement in implementing the latest version of these standards, with local implementation systems not yet working adequately and concerns about capacity problems in the Bank and local authorities responsible for oversight. COVID-19 has also posed challenges for monitoring these standards.

World Bank staff and other donors view the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office as systematic and successful in influencing IDA’s strategic direction, assisted by agile and effective networking between London, Washington and country teams. The country teams work closely with their counterparts in IDA in areas where their programmes and the work of locally based staff overlap, but recent reductions in UK bilateral aid have narrowed this space and priorities for future co-financing may need to be looked at again.

The UK’s influence on IDA has rested not only on its financial contribution, which was reduced significantly in IDA’s latest replenishment, announced in December 2021. As long as the UK remains a major funder of IDA (it is about to become the third-largest) and keeps up the analytical and negotiating skills it deploys in engaging it, the UK will remain influential in determining IDA’s strategic direction. The UK also benefits significantly from IDA’s use of donor contributions to leverage additional resources.

- Relevance: How well aligned is IDA with the UK’s development priorities? Green / Amber

- Effectiveness: How effective is IDA’s support for partner countries? Green / Amber

- Efficiency: To what extent does the UK obtain value for money from IDA? Green

Acronyms and glossary

| Acronym | Definition |

|---|---|

| CPF | Country Partnership Framework |

| CSO | Civil society organisation |

| DFID | Department for International Development (merged in September 2020 with the Foreign and Commonwealth Office to become the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office) |

| DIME | Development Impact Evaluation |

| DRC | Democratic Republic of Congo |

| ESF | Environmental and Social Framework |

| FCDO | Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office |

| GRM | Grievance response mechanism |

| IBRD | International Bank for Reconstruction and Development |

| ICAI | Independent Commission for Aid Impact |

| IDA | International Development Association |

| IFC | International Finance Corporation |

| IEG | Independent Evaluation Group |

| IMF | International Monetary Fund |

| IRUMP | Integrated and Resilient Urban Mobility Project (Sierra Leone) |

| MDB | Multilateral development bank |

| ODA | Official development assistance |

| OECD | Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development |

| PBA | Performance-based allocation |

| RMS | Results measurement system |

| SIEF | Strategic Impact Evaluation Fund |

| WBG | World Bank Group |

| World Health Organisation | World Health Organisation |

Executive summary

This review assesses how the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO) manages its contribution to the World Bank’s International Development Association (IDA), the world’s largest source of grants and low-interest loans for low-income countries, and the value for money this contribution provides for the UK taxpayer. We focus in particular on three ‘priority themes’: climate resilience, fragile states, and the COVID-19 response, as well as IDA’s track record on environmental and social safeguards and social inclusion. This review mainly covers the period from 2015 to 2021 and the four multi-year IDA funding arrangements, called replenishments, falling within it. The last of these (announced in December 2021, and which we could not review in any depth due to timing) marks the end of a long period when the UK was IDA’s largest contributor.

Background

About a third of all development aid from industrialised countries is provided as institutional (or un-earmarked) funding to multilateral or inter-governmental organisations. These include multilateral development banks, of which the World Bank Group (WBG), with its annual commitments (including from non-aid sources) of over $100 billion, is the largest. These banks can offer donors like the UK the benefit of their larger scale, depth and (often) breadth of operations and related technical expertise, including a presence on the ground where the donor has none itself. Increasingly they are also valued for the delivery of international public investments in global public goods, like climate change mitigation.

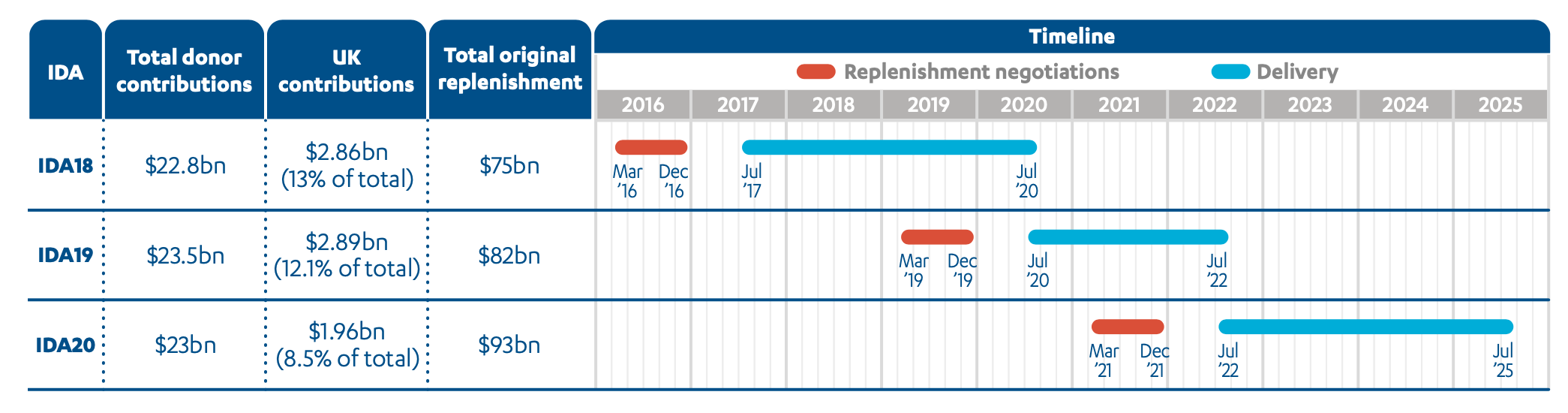

IDA, founded in 1960, is one of the major components of the WBG, and provides grants and long-term loans to 74 low-income countries for a wide range of social and economic development purposes. IDA’s funding ceiling is agreed with its shareholders every three years, during lengthy ‘replenishment’ negotiations. Its funds come from four main sources, including donor contributions, reflows from loan repayments, internal World Bank resources, and, more recently, borrowing from financial markets. This third source has facilitated a continuous rise in IDA’s three-year replenishment budget, from $52 billion for 2014-17 to $93 billion for 2022- 25. IDA complements the operations of the WBG’s other institutions, which include the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development’s lending to middle-income countries on more market-related terms than IDA, and the International Finance Corporation’s financing to the private sector.

The UK spends about 35% of all its aid through core multilateral contributions and about a quarter of that on IDA, meaning that roughly £1 of every £12 of UK aid was received by IDA during 2015-20. During our review period, the UK was also the largest single donor to IDA, contributing a steady 12-13% of all donor funds, until the decision to reduce this share to just over 8% announced in December 2021. IDA replenishment negotiations also set allocations across funding streams and countries, and sector priorities and policies to be applied to its operations. The UK, as we examine below, is particularly active in this process.

Relevance: How well aligned is IDA with the UK’s international development priorities?

IDA is relevant to, and strongly aligned with, the UK’s development priorities during the review period. IDA’s portfolio has a strong poverty focus. This alignment is partly by design: only low-income countries (currently below $1,205 per capita income, with specific exceptions) can receive support from IDA, and within this eligible group, more funding and softer terms are available for lower-income countries. The UK has consistently advocated for this progressive income-based ‘graduation’ approach for countries within and ultimately out of the IDA pool altogether. However, the empirical link between countries with low per capita income and the concentration of global poverty and other major challenges has weakened over the past decade, as average incomes grew but underlying structural problems persisted in many large developing countries.

Thematically IDA is also well aligned to key UK priorities such as gender, disability, fragility, early crisis responses, human capital, and jobs and economic transformation. Indeed, the UK was a front-runner among IDA donors in advocating for all of these priorities, especially in the case of disability inclusion. Climate change, particularly resilience, has been a special theme since IDA16. IDA support for climate resilience developed further during IDA18 and IDA19, although IDA19 climate-related commitments fell short of UK ambitions. World Bank priority for climate change more widely, especially support for mitigation, was less evident during the Trump US administration (2017-21), which opposed multilateral action in this area.

IDA works closely with partner country governments, which affirm their ownership of IDA programme choices and implementation and have an increasing, though largely informal, voice in replenishments. Long-standing debates about the excessive or unreasonable policy reform conditions of World Bank (and International Monetary Fund) programmes, especially before the release of budget support, have resurfaced recently under the Bank’s current leadership. But such concerns were not echoed by any of our IDA borrower government interviewees.

The World Bank is becoming more open to direct citizen engagement, but this is still work in progress. It has mandated consultations ahead of approval of all new country strategies and individual operations. Internal reviews have found these engagements to occur far more often, but not yet to be as intense as intended.

Effectiveness: How effective is IDA’s support for partner countries?

IDA’s operational performance is generally strong and on an upward trajectory, according to its internal results management system, which is subject to quality checks on all projects and substantial sampling of follow-up performance reviews by the World Bank’s internationally respected Independent Evaluation Group. This broadly positive assessment applies both to overall project results and, to a lesser extent, to country portfolio quality. On completion, over four out of five IDA operations now pass its headline test of ‘moderately satisfactory or better’ outcome scores.

The focus of most IDA results targets is, however, on outputs and intermediate outcomes, not final development impacts, which are objectively harder to identify, manage and attribute. The way multiple results objectives on different levels are aggregated within individual operations also makes systematic scrutiny harder. However, steps are being taken to increase corporate outcome focus, including by greater integration of lessons from impact evaluations.

This mostly positive picture according to internal results also holds for three of this review’s priority themes: climate resilience, fragile states, and the COVID-19 response. Climate change action is mainly rated by measuring the proportion of the portfolio with side benefits for the reduction of global emissions or their impact on developing countries. This ‘co-benefit share’ is a common multilateral development bank standard with some weaknesses, and targets which IDA is already largely meeting (overall) or exceeding (for climate resilience in particular). Higher co-benefit shares are not necessarily better than lower ones, as at some point an exclusive focus on climate benefits could crowd out important IDA non-climate outcomes and constrain efforts to address the needs of IDA borrowers.

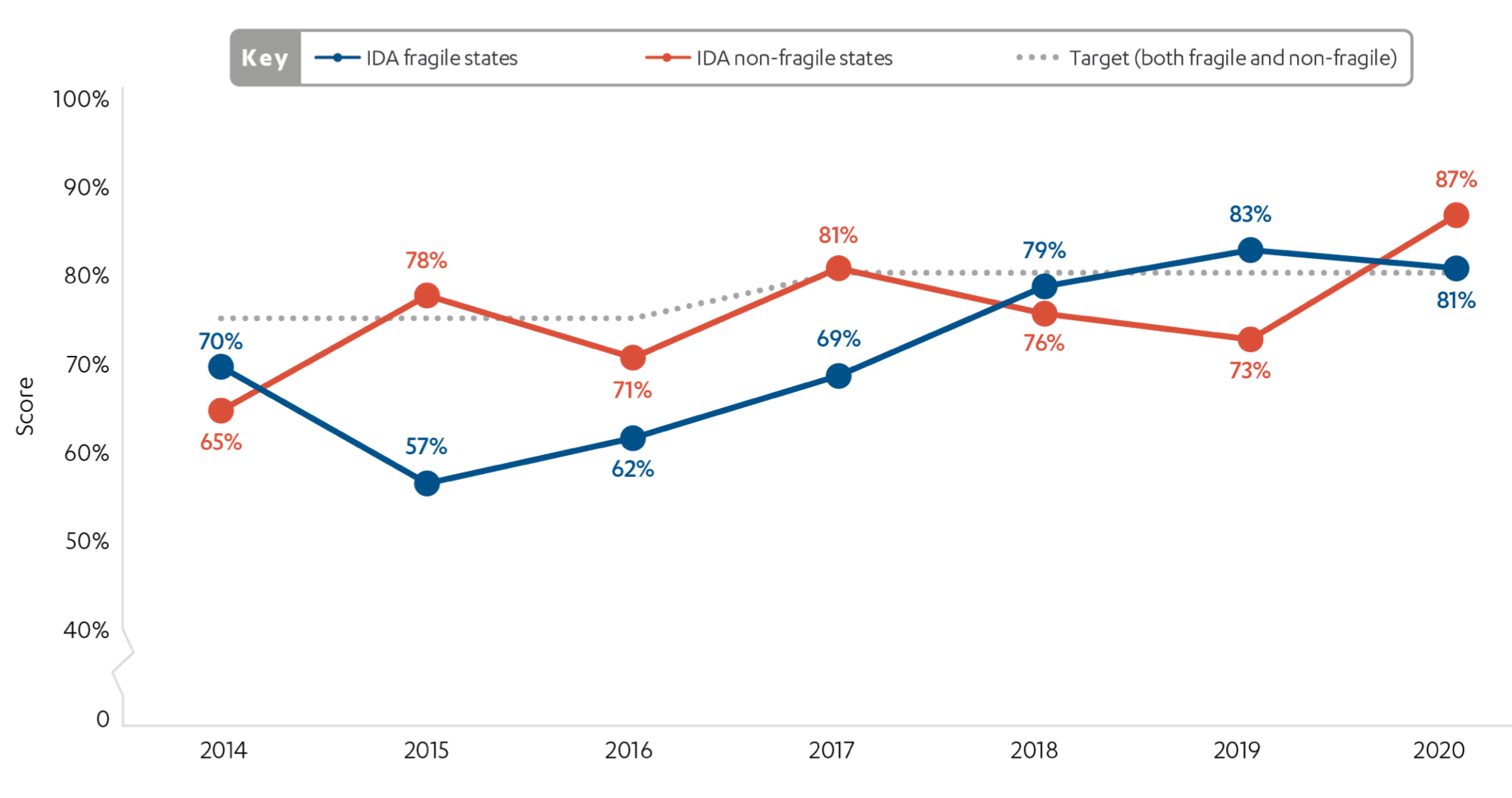

IDA performance in fragile states, measured by the share of operations meeting their outcome objectives, has come close to that in non-fragile contexts, although underlying objectives may differ so much between the two sets of countries as to defy comparison. IDA’s COVID-19 response broke records for speed and flexibility at scale, thanks to process innovation, technology and sheer hard work, but it is too soon to judge impact. IDA has quickly become an indispensable vaccine funder for low-income countries.

IDA has also made a visible effort to include specific groups which are at risk of discrimination on grounds of, for example, gender and disability. It could, however, do more for broader social inclusion, including implementing the Bank’s strategic ‘co-prosperity’ goal, which targets faster-than-average growth for the lowest 40% of the population by income in all countries.

The World Bank’s environmental and social safeguards have greatly expanded. Implementation is the responsibility of national agencies, which face increasing capacity challenges as a result. However, we also found weak monitoring capacity on the part of the Bank and problems with grievance redress systems on the ground. These could prove a serious obstacle if replicated across the wider IDA portfolio.

The Bank’s fiduciary, anti-corruption and fraud controls have been well regarded and considered an institutional strength in earlier Independent Commission for Aid Impact and other reviews. Nevertheless, we remain concerned that persistent pressure to hit ever-higher IDA commitment levels in countries with weak national systems, under strict conditions and safeguards, may strain capacity for reducing fiduciary risk to the limit.

Efficiency: To what extent does the UK obtain value for money from IDA?

UK taxpayers get good value for money from the UK’s stake in IDA. This is partly because of IDA’s close alignment to UK priorities and its effectiveness in delivering results, but also because of its ability to leverage other resources.

IDA is able to mobilise major contributions from non-aid sources, in addition to those contributed by donors like the UK, on a scale that no other multilateral development institution focused on low-income countries is able to achieve. It has always made long-term loans, whose future repayment streams get recycled into new operations. It has also, for many years, been the beneficiary of substantial net income transfers from other parts of the WBG operating in middle-income and emerging countries – indirectly a transfer from richer to poorer members. In addition, it incentivises private sector investment stakes in individual IDA projects, particularly in infrastructure and through its Private Sector Window.

For the last four years, IDA’s growing financial market borrowings have been increasingly important in this context, underpinned by the huge asset base constituted by these outstanding loans and supported by IDA’s excellent market credit ratings. The combined effect of this resource package is that every £1 of UK funding is now linked to £2.50 of additional non-donor resources mobilised. Donor contributions remain essential, however, both to reassure markets and to cross-subsidise softer terms and grants passed on to IDA’s clients.

The World Bank and IDA also bring to the table other less tangible sources of value: notably world-class development advisory and research capabilities which support its financial operations. The integrity of the Bank’s research effort has been challenged recently by allegations of top management pressure on research staff to manipulate findings in the Doing Business report for political ends. However, our review team heard opinions that the Bank’s reputation for objectivity had not suffered any lasting damage. A more frequent criticism is that its vast range of research topics would benefit from greater prioritisation.

Finally, with its COVID-19 response, IDA has proven its value as a last-resort insurer or ‘surge capacity’ in the face of global crises, alongside other parts of the WBG and the International Monetary Fund.

The UK has a systematic and highly effective IDA influencing strategy, respected by management and partners. This rests not just on the UK’s lead funder role but also on analytical contributions and agile networking with its country teams and with other donors.

Influencing by UK embassies and high commissions on IDA teams in-country was found to be more opportunistic and concentrated in areas where their programmes and the work of locally based staff overlap.

We asked IDA staff and other donors whether a large part of the UK’s influence on IDA would be lost in the event of a drop in its funding from lead to third donor, as is now occurring. The consensus was that it would not, providing the UK’s intellectual and political leadership skills were kept up, and its funding slide did not continue much further. If the UK manages to carry off the feat of contributing only about 2% of IDA’s total resource package, yet retaining substantial influence on its direction, this represents very real leverage.

Recommendations

We offer a number of recommendations to help FCDO increase the value of its contributions to IDA:

Recommendation 1

Climate targets: FCDO should advocate for more action-focused targets for IDA climate change action, particularly on adaptation.

Recommendation 2

Country relationships with IDA: FCDO should set more systematic objectives for engaging the World Bank at country level.

Recommendation 3

Leave no one behind: FCDO should hold IDA accountable for meeting the ‘leave no one behind’ commitment, including by advocating for the operationalisation of its ‘co-prosperity goal’.

Recommendation 4

Environmental and social safeguards: FCDO should work constructively with World Bank management and other donors to improve the Bank’s capacity to monitor and oversee implementation of environmental and social safeguards.

Recommendation 5

Pressure to lend and financial system strengthening: The UK should strengthen key country partnerships with IDA to bolster public financial management and anti-corruption programmes.

Introduction

A third of global aid from Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development donors goes towards core funding to multilateral development organisations, such as the World Bank’s International Development Association (IDA). Multilateral organisations are diverse in their mandates, but collectively offer certain advantages as a channel for aid, including their ability to concentrate resources and expertise, promote global public goods, and address development challenges at a global scale. It has also been suggested that they provide a greater degree of political neutrality and insulation from donor economic interests than bilateral development organisations do.

Among multilateral organisations, the multilateral development banks (MDBs) play a unique role in utilising a variety of financing instruments – including grants, loans and guarantees – to support investments at scale across a wide range of countries and sectors. By far the largest MDB in terms of commitments to developing countries is the World Bank Group, which currently provides more than $100 billion in finance annually to developing countries through its five institutions, including IDA.

IDA specialises in providing finance on grant terms and better loan terms than available from financial markets (collectively referred to as ‘concessional’ finance) to low-income countries. It will provide $93 billion of finance in the three-year cycle beginning in July 2022, making it the single-largest source of international aid for the world’s poorest countries. In addition to its funding impact, IDA offers platforms for policy dialogue at country and thematic levels, including through its specialised windows on regional public goods, refugees, private sector investment and other topics.

The UK government is a major supporter of multilateral development organisations, especially the World Bank. Between 2015 and 2020, the UK provided 35% of its mostly increasing aid budget – equivalent to an average of £4.9 billion annually – as core multilateral funding. Over this same period, a quarter of UK multilateral aid went to IDA which, as a result, received around £1 in every £12 of total UK aid. This level of support led to the UK becoming the largest donor to IDA over most of the past decade, a position it has decided to relinquish in the 20th round (IDA20, covering 2022-25). The quality of support provided through IDA is therefore central to the overall impact of UK aid.

While a number of Independent Commission for Aid Impact (ICAI) reviews have examined programmes financed by IDA, only a small number have examined IDA as a whole, most recently in 2015. A review of UK support for IDA therefore provides an opportunity for a stand-alone assessment of this important element of UK multilateral aid. It also provides an opportunity to examine changes to IDA’s financing and investment model introduced since 2016.

The purpose of this review is to assess both the effectiveness of UK aid through IDA and how well the UK has used its position as IDA’s largest bilateral donor to shape its policies and operations.

The review is built around the evaluation criteria of relevance, effectiveness and efficiency. It will address the following questions and sub-questions about IDA’s impact and the UK’s efforts to influence its operations.

| Review criteria and questions | Sub-questions |

|---|---|

| Relevance: How well aligned is IDA with the UK’s international development priorities? | • How well does IDA’s portfolio support the UK’s development priorities and its cross-cutting themes? • How well are the needs and voices of governments and poor people in partner countries reflected in IDA programmes? |

| Effectiveness: How effective is IDA’s support for partner countries? | • How well has IDA delivered its intended results (outputs and outcomes) through its operations? • How well are IDA objectives on equity, inclusion and safeguarding delivered in practice? |

| Efficiency: To what extent does the UK obtain value for money from IDA? | • How well has IDA mobilised other sources of development finance, including from within the World Bank Group? • How robust is the evidence base on IDA’s performance and value for money used by the UK to justify the level of its IDA-related contributions and its share of overall IDA funding? • How well has the UK used its IDA contributions and relationship with the World Bank to shape IDA policy and to advocate for continuing improvement in the Bank’s organisational performance and portfolio? |

Methodology

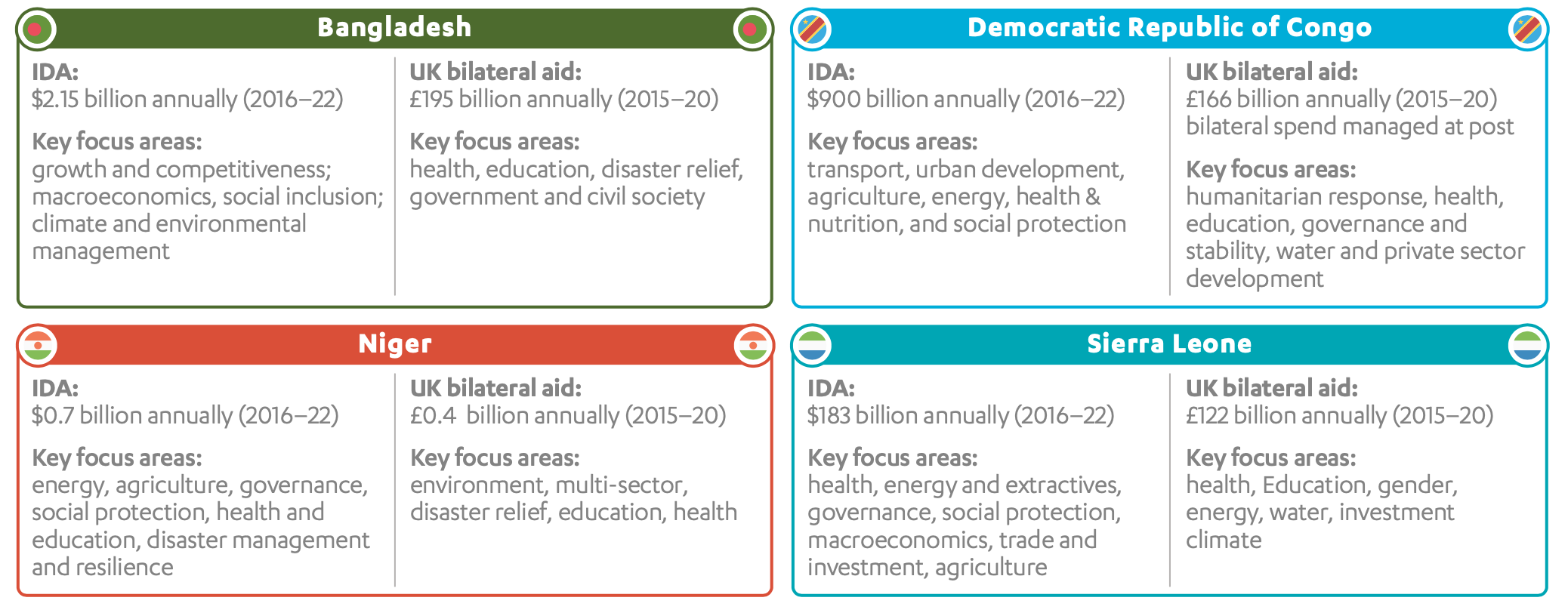

The review methodology included six main components (see Figure 1) to allow for a good level of methodological and data triangulation for robust answers to the review questions.

Figure 1: Methodology wheel

Component 1 – Strategic review: We analysed the strategies and priorities both of the International Development Association (IDA) and of the UK for engaging IDA as these evolved across the period encompassing IDA18 (2017-20), IDA19 (2020-22) and the negotiation of IDA20. The analysis focused on issues such as IDA country allocations, thematic priorities, issue-specific funding windows and reform priorities. It involved reviewing relevant documentation and interviewing officials from both the World Bank (including through a visit to the Bank’s Washington headquarters) and the UK’s Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO), as well as a range of external experts and stakeholders.

Component 2 – Thematic review: We analysed IDA strategy, policy and performance and UK efforts to influence IDA in relation to each of the priority themes for this review: i) fragility, conflict and violence; ii) climate adaptation and resilience; iii) the COVID-19 response; and iv) equity, inclusion and safeguards. This analysis involved document reviews, interviews (with both officials and some key external actors) and the programme reviews (see Component 4).

Component 3 – Literature review: We produced a literature review, which is published alongside this report and explores the evolving policy, functioning and effectiveness of IDA and the key debates about its strategic focus and development role. It covers both World Bank publications and academic and grey literature published by a range of organisations. Key themes addressed through the literature review include: the effectiveness of IDA in delivering development impacts, including a benchmarking of performance against other multilaterals; the background, nature and impact of IDA’s work in the focus thematic areas; and key debates about the World Bank, IDA and its future.

Component 4 – Country case studies and reviews: Our country-level analysis explored the effectiveness of IDA and the UK’s engagement with World Bank-IDA policy and operations at the country level in four countries. There were two in-depth country case studies, one involving an in-person country visit (Sierra Leone) and the other involving a virtual visit (Democratic Republic of Congo, DRC) as COVID-19 restrictions limited travel opportunities. In addition, there were two country desk reviews – on Bangladesh and Niger. These case studies and desk reviews were informed by the programme reviews and reviews of country-level documentation, with the in-depth case studies involving extensive interviews with the World Bank, FCDO, partner country officials and other stakeholders, including civil society. The countries for these country case studies and reviews were selected using the sampling methodology presented in the approach paper.

Component 5 – Programme reviews: We reviewed individual IDA programmes, which provided granular insight and evidence to inform the country case studies and thematic reviews. In each of the four focus countries, three IDA programmes were selected for review (in other words, 12 in total). Each of these helped to examine the priority themes for the overall review, and involved analysis of programme documents, as well as a small number of interviews related to each programme (where relevant).

Component 6 – Citizen engagement: ICAI gives the highest priority to including the voices of those who are intended to benefit from or are affected by UK aid. Researchers in DRC and Sierra Leone interviewed citizens in relation to a major infrastructure project in each country. This research investigated whether relevant World Bank IDA policies and procedures related to social and environmental safeguards were applied, and whether these were adequate to ensure responsiveness to community needs.

Limitations to the methodology

There are three main limitations to the methodology of this review:

- Scale of the review relative to that of IDA: The in-depth review of programmes analysed just 12 of the 1,628 IDA operations currently being implemented and focused on just four of IDA’s current client base of 74 countries. Similarly, the direct citizen engagement work focused on a small group of people affected by two of the IDA projects reviewed. While both of these elements of the review were supplemented by other sources, it is important to acknowledge that the sample of IDA operations assessed and affected citizens engaged is unlikely to be representative.

- Constraints relating to stakeholder engagement due to COVID-19: The main stakeholder interviews for the DRC case study were undertaken remotely due to restrictions resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic. As a result, there were constraints related to the number and quality of stakeholder contacts available for this case study, resulting in limitations to the evidence that emerged.

- Limited insight on the outcomes of the IDA20 replenishment process: Although the IDA20 replenishment process was completed during the course of this review (in December 2021), the timing of the evidence gathering phase – from June to November 2021 – did not allow us to undertake a full assessment of the UK’s role in shaping the outcome. Our insights on UK influence over IDA replenishments therefore focus largely on IDA18 and IDA19 and we make fewer references to the IDA20 settlement.

Background

IDA’s history and role in the World Bank

Building on its experience in supporting post-war reconstruction in Europe, in 1960 the World Bank formed a new financing arm to provide concessional finance to developing countries – the International Development Association (IDA). IDA’s founding Articles of Agreement state that its purpose is to:

…promote economic development, increase productivity and thus raise standards of living in the less-developed areas of the world included within the Association’s membership, in particular by providing finance to meet their important developmental requirements on terms which are more flexible and bear less heavily on the balance of payments than those of conventional loans…

International Development Association Articles of Agreement, Article I (Purposes), September 1960, link

Beginning with an initial capitalisation of $912 million and a founding membership of 15 countries, over the following decades IDA grew rapidly in size and attracted a wider range of member countries. IDA currently has 174 members and supports 74 developing countries, committing $36.7 billion in funding in financial year 2020-21.

IDA is one of five development institutions which form the World Bank Group, and its focus is on providing highly concessional finance to governments in the poorest and most vulnerable countries. The other World Bank Group institutions are:

- the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (IBRD), which provides less concessional financing to middle-income countries

- the International Finance Corporation (IFC), which provides equity and more commercial loans to private companies and financial institutions across developing countries

- the Multilateral Investment Guarantee Agency (MIGA), which provides political risk insurance (guarantees) to investors and lenders across developing countries

- the International Centre for Settlement of Investment Disputes (ICSID), which supports the conciliation and arbitration of international investment disputes.

How IDA functions

IDA replenishments

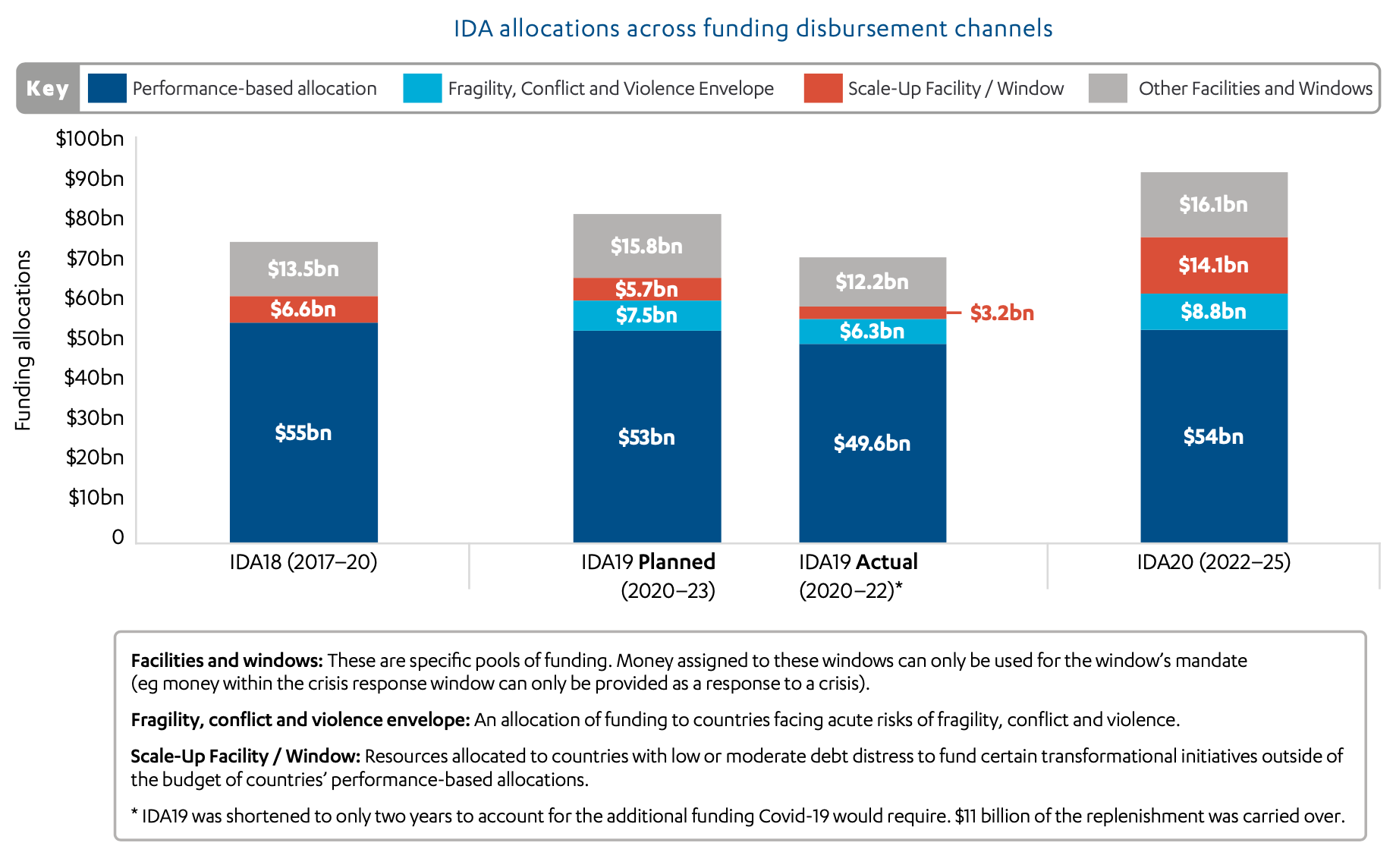

The funding available to countries from IDA is mobilised through a process of replenishing its funds, usually every three years (by custom, these replenishment periods are referred to sequentially by number; IDA20 is starting in 2022). Traditionally, funds were pledged by its shareholders (mainly Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development countries) and supplemented by reflows from loan repayments and other sources.11 However, since IDA18 (2017-20), the World Bank has supplemented IDA’s finances with borrowing from international bond markets (against the value of IDA’s outstanding loans). This has allowed IDA to expand its resources, from $52 billion for IDA17 to $93 billion for IDA20. Not only did this expansion confirm its status as the world’s largest source of concessional multilateral funding for developing countries, it also helped IDA to overtake its older and less concessional (or more market-related) sister, IBRD, in 2020, at least in terms of commitments. As a consequence of this additional funding, the share of donor contributions – which had remained broadly constant until IDA17 – in IDA’s total resources has fallen considerably (see Figure 2).

In addition to discussing funding sources and uses, IDA replenishment processes involve World Bank management and shareholders agreeing allocations across funding streams and countries, as well as sector priorities and policies to be applied to programmes and general operations.

Figure 2: Total IDA financing and funding mobilisation, IDA17 to IDA20

Sources: IDA18 retrospective: Investing in growth, resilience and opportunity through innovation, 2021, figure ES.1, p. x, link; IDA19 implementation status and proposed reallocations, 2021, p. 26-28, link; IDA20 report from the executive directors of the International Development Association to the Board of Governors, 2022, table 4.1, p. 73, link.

Governance

The World Bank’s Board of Governors oversees the Bank’s work and meets annually. The Board of Governors consists of one governor for each member country, who collectively make decisions about the Bank’s functioning. Decisions about IDA (including the terms of IDA replenishments or midterm adjustments) are made specifically by IDA deputies, who are senior official representatives of IDA member countries. IDA member countries do not, however, have equal formal say over these decisions, although in practice they are taken on a consensus basis. The World Bank president (by tradition an American, David Malpass since April 2019) chairs the Board and is also the organisation’s Chief Executive Officer.

The Board of Governors delegates day-to-day decision making – including for approving individual IDA programmes – to the World Bank and IDA Boards of Directors, which consist of 25 executive directors who collectively represent all members. Six countries (the UK, China, France, Germany, Japan and the US) currently appoint their own executive directors, with the other 19 executive directors representing other country constituencies.

IDA funding eligibility and terms

To be eligible for IDA funding, countries need to meet one primary eligibility criterion: they must have an average income per person below the ‘operational cut-off’, which is revised annually and is currently $1,205. Also under consideration are a country’s creditworthiness and risk of debt distress. In addition, formal assessments of debt sustainability help determine the share of grants in a country’s overall financing.

As a country’s income increases above the operational cut-off level, the country begins a multi-phased process of ‘graduation’ from IDA. This involves a move towards borrowing at a higher cost from IBRD, as the country’s creditworthiness improves. Over its history, 46 countries have graduated from IDA funding – including ten since 2010 and five since 201515 – although nine returned to eligibility due to economic or other shocks. There are currently 74 IDA-eligible countries, of which receive a blend of funding from both IDA and IBRD.

One exception to this traditional system of countries graduating from IDA is the case of ‘small island economies’ which, in recognition of their vulnerability to shocks, have been able to access IDA funding despite their incomes often being well above the IDA operational cut-off.

IDA funding allocation

IDA mainly provides loans and grants to government entities by funding standard projects (known as Investment Project Financing), budget support (known as Development Policy Financing), and projects supported on a performance basis (known as Programme-for-Results).

The majority of IDA’s funding is allocated to countries on the basis of performance-based allocations (PBAs). PBAs are calculated according to the quality of countries’ policies and institutions – based on the results of the World Bank’s Country Policy and Institutional Assessments – as well as their population and level of income.

In addition to PBAs, an increasing volume of IDA resources – around 27% at the end of IDA1819 – is allocated to countries through special funding windows, envelopes or set-asides, which each have their own allocation rules. These include the Regional Window, the Crisis Response Window and the Arrears Clearance Set-aside. More recently, IDA has introduced the Window for Host Communities and Refugees, the Scale-Up Window,20 the Private Sector Window and the Fragility, Conflict and Violence Envelope

(see Figure 3 and Annex 1 for more detail).

Figure 3: IDA allocations across funding disbursement channels

Sources: IDA18 retrospective: Investing in growth, resilience and opportunity through innovation, 2021, table 2.1, p. 7, link; IDA19 implementation status and proposed reallocations, 2021, p. 26-28, link; IDA20 report from the executive directors of the International Development Association to the Board of Governors, 2022, table 4.1, p. 73, link.

Sub-Saharan Africa is IDA’s largest region of operation, receiving 64% of commitments during IDA18, followed by South Asia (22%). Fragile and conflict-affected situations have also seen their funding levels increase rapidly, from $10.1 billion (19% of total) in IDA17 to $23.0 billion (30% of total) in IDA18.

During IDA18, public administration and energy were the largest sectors for IDA operations (16% and 14% of commitments respectively), with other major sectors including education, social protection and health (11% of commitments each).22 During the first year of IDA19, commitments to social sectors almost doubled, compared to the first year of IDA18, stimulated by the COVID-19 response.

IDA’s strategic and sector focus in each country is guided by overall World Bank country plans – called Country Partnership Frameworks – which are supposed to be produced in partnership with local stakeholders and are usually revised every three years.

Although IDA funding is mostly allocated by country, the introduction/expansion of thematic funding windows and changes to IDA’s strategic emphasis have led to a growing focus on global public goods, such as addressing climate change, developing regional infrastructure and responding to global crises.

IDA conditionality

Policy reform conditions, which are negotiated and agreed with borrowing governments, are applied to development policy financing and act as a trigger for access to funding. These conditions have been a controversial element of World Bank policy, especially during the 1980s, when they were used to promote economic reforms that many believe to have been harmful. Critics of the World Bank’s present approach to the scope of policy conditions (also known as ‘conditionality’) argue that this practice constrains national sovereignty and that the Bank continues to push controversial reforms. However, others argue that the World Bank has since adopted a more consensual approach, and that its policy conditions are supportive of reformers in developing countries.

UK funding and priorities for IDA

The UK has been one of the largest contributors to IDA throughout its history and has considerably increased its contributions over the last two decades. The UK became the largest IDA donor during IDA15 (2008-11), a position it also held during IDA17 (2014-17), IDA18 (2017-20) and IDA19 (2020-22). However, the UK’s significantly reduced pledge for IDA20 has resulted in it falling behind the USA and Japan.

Between IDA17 and IDA19, the UK’s share of donor contributions to IDA stayed relatively stable, at 12%-13% of the total. However, its share of total IDA resources has fallen since the World Bank began supplementing replenishments with external borrowing.

Between 2015 and 2020, on average, £1 in every £12 of UK official development assistance, and £1 in every £4 of UK core multilateral contributions, went to IDA – around £1 billion a year. Across this period, annual UK contributions to IDA stayed relatively stable in cash terms but fell as a share of total UK aid spending.

As is the case with all IDA shareholders, the UK government identifies themes – particular development challenges or reform issues facing the Bank – to prioritise for each replenishment, and on which it aims to secure additional IDA commitment and action. The UK’s priorities for IDA18, IDA19 and IDA20 are presented in Table 2.

Figure 4: IDA replenishment timeline

Table 2: UK priorities for IDA18, IDA19 and IDA20

| Priorities | |

|---|---|

| IDA18 priorities | • Fragility and crises – more resources for fragile states, increased flexibility and staffing in fragile states, and strengthened crisis response • Jobs and leveraging the private sector – a core theme for IDA18, closer collaboration of IDA with IFC and MIGA • Leave no one behind and women and girls – strong emphasis on women’s economic empowerment • Climate change – increased support for climate resilience • Results – to scale up support for country statistical capacity • Resourcing, graduation and pricing – better managed graduation from IDA, ambitious IDA leveraging, and using additional IDA funds to support the poorest and most fragile countries |

| IDA19 priorities | • Fragility, conflict and violence – tackling the drivers of fragility and conflict, mitigating risks, tackling corruption and illicit financial flows • Crises – improving analysis, mitigation and prevention of crisis risks in client countries • Leave no one behind – more ambitious or new commitments on gender equality, disability and tackling sexual exploitation, abuse and harassment • Human capital – supporting the Bank’s emphasis on developing human capital • Jobs and economic transformation – support for productive sectors, open trade and investment and creating jobs; an emphasis on migration, labour, skills and youth • Climate change – tackling climate change and promoting resilience, through investments, analytics and dialogue with governments • IDA operational and financial framework – improving the focus on results, value for money, transparency, agility, collaboration and effective staffing |

| IDA20 priorities | • COVID-19 – resources at scale to address economic impacts, fund vaccines and respond to health needs; including further use of balance sheet to raise finance • Promoting a green, inclusive and resilient recovery – supporting countries to plan for a sustainable recovery, and to monitor and plan for future crises • Girls’ education – improving learning and getting 40 million additional children into school by 2025 • Climate change – helping countries plan for and manage the impacts of climate change and increase the amount of finance mobilised for adaptation and resilience • Crisis preparedness – addressing the increasing risks around the challenges of food security and climate change through better use of pre-arranged financing and faster use of IDA’s resources in a crisi• COVID-19 – resources at scale to address economic impacts, fund vaccines and respond to health needs; including further use of balance sheet to raise finance • Promoting a green, inclusive and resilient recovery – supporting countries to plan for a sustainable recovery, and to monitor and plan for future crises • Girls’ education – improving learning and getting 40 million additional children into school by 2025 • Climate change – helping countries plan for and manage the impacts of climate change and increase the amount of finance mobilised for adaptation and resilience • Crisis preparedness – addressing the increasing risks around the challenges of food security and climate change through better use of pre-arranged financing and faster use of IDA’s resources in a crisi |

IDA and the focus themes for this review

This review has selected a number of key themes and cross-cutting issues for in-depth analysis. These themes and issues have been selected because they reflect issues prioritised by both IDA and the UK government across the review period (in the case of climate resilience and fragility, conflict and violence (FCV) issues) or more recently (in the case of COVID-19), or they reflect important contemporary development challenges that the Bank has been working with shareholders to address (in the case of inclusion, equity and safeguards).

Presented below is a brief background on each theme, including an overview of how they link to UK priorities.

- Fragility, conflict and violence: The World Bank has been working to address the challenges of fragile, conflict- and violence-affected situations (hereafter referred to as fragile states) for the last two decades. In recent years, the Bank has developed its work to focus on FCV, recognising the impact of violence and criminality on development. Increasing IDA’s operations and capacity in fragile states was a priority theme for the UK government during IDA18 and IDA19 and was also an IDA special theme supported by special financing allocations in IDA18, IDA19 and IDA20.

- Climate change adaptation/resilience: For most IDA recipients, adapting and building their resilience to the effects of climate change is highly relevant to their development prospects, as these countries face disproportionate risks from climate change impacts and have the least adaptive capacity to respond to them. Climate change was a priority theme for the UK government and a ‘special theme’ for the IDA replenishment during IDA18, IDA19 and IDA20.

- Response to the COVID-19 pandemic: The COVID-19 pandemic has pushed an estimated 100 million more people into extreme poverty, had major impacts on health and education systems and led to a spike in debt as countries borrow to finance their response. IDA mobilised an ambitious response to this crisis, supported by a front-loading of IDA19 funds and bringing forward the IDA20 replenishment by a year. It rapidly approved financing for COVID-19 support across IDA countries in April 2020 and subsequently extended these programmes to support vaccine access. More broadly, crisis response has been a priority for the UK government and has been prominent in IDA replenishment discussions during each of IDA18, IDA19 and IDA20.

- Inclusion and equity: In 2015, the World Bank Group (WBG) joined the rest of the international community in committing to the Sustainable Development Goals, which included a commitment to the ‘leave no one behind’ principle of focusing development assistance first and foremost on those left behind by recent development progress. Reflecting the World Bank’s existing twin goals to eliminate extreme poverty and increase the incomes of the poorest 40% of people (introduced in 2013) the subsequent period has seen a number of related themes prioritised by the UK and IDA. These include gender equality, which was a special theme during IDA18, IDA19 and IDA20, as well as disability, which was a special theme during IDA19.

- Environmental and social safeguards: Over the last two decades the World Bank’s approach to applying environmental and social safeguards – policies and procedures for ensuring that aid programmes do no harm to and benefit communities and the environment – has been the focus of significant debate, both inside and outside the Bank. Following a major evaluation in 201029 and an intensive review process during 2012-16 in which the UK was an active player) the WBG launched its new Environmental and Social Framework in 2016, which became operational in October 2018.

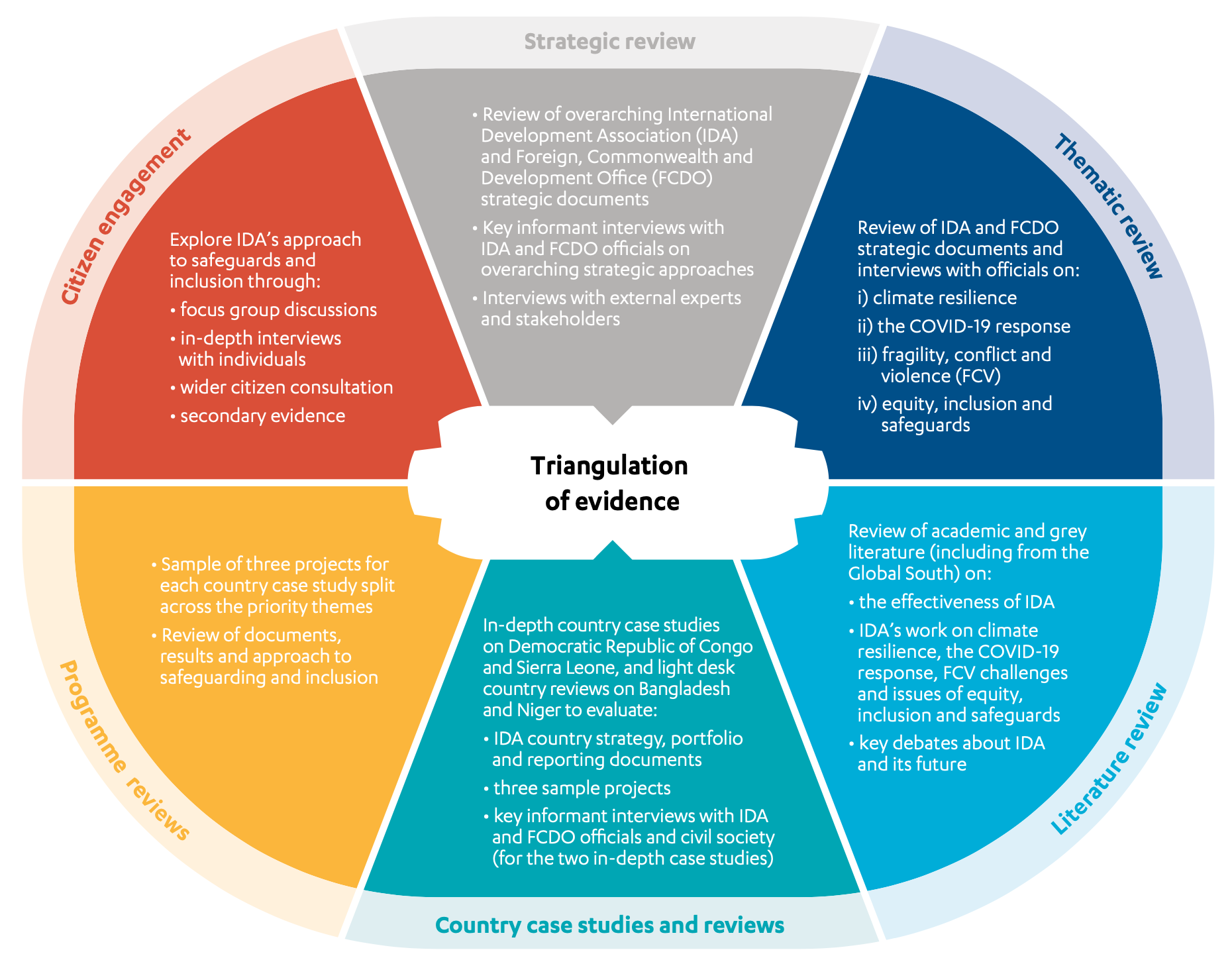

IDA and the focus countries for this review

This review has included in-depth analysis on IDA programmes and UK engagement with IDA in four countries – the Democratic Republic of Congo and Sierra Leone (the subjects of country visits), as well as Bangladesh and Niger (the subjects of desk studies). Figure 5 illustrates the context, scale and focus of IDA programmes in each country, as well as relevant information about the UK aid programme in these countries.

Figure 5: IDA and UK bilateral portfolio in case study countries

Findings

Relevance: How well aligned is IDA with the UK’s international development priorities?

This section first reviews the overall strategic alignment of IDA’s portfolio with the UK’s long-standing focus on poor countries, as well as fragile states, and other key UK thematic priorities such as gender, disability, crisis response and climate change. It then examines how well the voices of partner countries, in terms of both governments and citizens, are reflected in IDA policies and operations, which is also a major UK objective.

IDA’s strategy and portfolio are well aligned with the UK’s international development priorities in the Association’s emphasis on tackling poverty, fragility and crises, its country allocations and its focus on inclusion

Overall, and consistent with previous analysis,32 we find IDA well aligned in strategy and portfolio terms with UK development priorities, especially regarding IDA’s poverty focus, cross-country footprint, emphasis on fragile states, focus on gender and disability, and responses to the COVID-19 pandemic. As explained below, this alignment seems to have been driven in part by the UK government’s significant influence over IDA in recent years.

IDA’s legal remit (see Section 3.1) is to “promote economic development, increase productivity and thus raise standards of living” in its beneficiary countries, which is squarely in line with promoting global prosperity, another of the UK government objectives in its 2015 aid strategy. From a strategic perspective, both IDA and the UK also place a significant emphasis on addressing global poverty. The first of the World Bank Group’s two overarching strategic goals is to support the eradication of extreme poverty. This mirrors the statutory objective of UK aid, which must be provided in ways that are “likely to contribute to poverty reduction”. In addition, one of the four core strategic objectives for UK aid over the period of this review has been “tackling extreme poverty and helping the world’s most vulnerable”.

UK development priorities continue to evolve, however, and with them the relative emphasis on poverty reduction. For example, following the merger of the Foreign and Commonwealth Office and the Department for International Development (DFID) into the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO) on 2 September 2020, the then foreign secretary laid out a significant shift in priorities in a letter to the chair of the International Development Committee linked to seven “global challenges”:

- climate change and biodiversity

- COVID-19 and global health security

- girls’ education

- science, research and technology

- open societies and conflict resolution

- humanitarian preparedness and response

- trade and economic development.

There may be questions about how the UK government sees the poverty reduction agenda reflected in the priorities of this letter and its new strategy for international development, which was published just as this review was being finalised. Answers will only become apparent over time. The integrated review for security, defence, development and foreign policy, which sets out the UK’s ambitions to tilt its global engagement towards the Indo-Pacific region, could be seen as implying a priority for more aid to be spent in this region, which tends to be less poor in terms of gross national income per capita.

IDA’s emphasis on supporting the poorest countries is implemented by its main eligibility criterion for support: the $1,205 per capita income cut-off. There are also special funding arrangements for countries which have limited or no access to the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (IBRD) despite having passed this income level, and for small island economies. During recent IDA replenishments, the UK has been a prominent voice calling for limits to special allocations of funding for graduating countries, to avoid diluting IDA’s poverty focus.

The UK has repeatedly advocated for this kind of firm ‘graduation’ approach to IDA eligibility as country incomes grow. However, as India and Vietnam, and soon other large IDA countries like Nigeria and Pakistan, progressively reach middle-income status, then graduate out of IDA altogether, yet still carry with them a high poverty headcount, IDA will no longer map as closely to global poverty as it once did. Middle-income countries are also a key focus of international efforts to invest in global public goods like climate change mitigation. Both factors argue for longer-term reconsideration of how scarce concessional resources are allocated globally, including within the World Bank Group (WBG). This longer- term question, important though it is, is beyond the remit of this review.

There are also similarities in allocations across regions and countries by IDA and the UK. Both concentrate support in sub-Saharan Africa, to which IDA directed 64% of its commitments during IDA18 (2017-20) and the UK directed 51% of bilateral aid during 2017-20. In addition, during IDA18 (financial years 2018-20), six of the ten largest IDA countries in terms of funding commitments featured among the top ten recipients of UK bilateral aid.

IDA and the UK have both placed strong emphasis on addressing the challenges faced by fragile, conflict- and violence-affected situations over the last decade. Building on a long-standing strategic focus on this group (going back to the early 2000s), and a more recent emphasis on how violence and criminality link to development, fragile states were priorities for IDA18, IDA19 and IDA20. The World Bank committed to increasing funding for these countries in its 2016 strategy document, Forward look, and in 2020 it launched its Strategy for fragility, conflict and violence 2020-25, which signalled a step change in the institution’s response to these challenges. For the UK, responding to the challenge facing these countries has been a core priority of all aid and development strategies going back to at least 2009.

The growing strategic focus of IDA and the UK on fragile contexts has driven an increase in IDA support for these countries in recent years. IDA interviewees confirmed that this progress was directly influenced by UK positions. The proportion of IDA commitments to fragile and conflict-affected situations increased from 18.7% during IDA17 to 30.1% during IDA18,47 and then 39% during the first year of IDA19. Driven by spending commitments in the 2015 UK aid strategy, over the period from 2015 to 2018 45% of UK bilateral aid was spent in fragile states, although this share fell back to 39% in 2018.

Another area of common strategic interest has been in addressing key issues related to inclusion, especially in responding to the development challenges facing women and girls, and people with disabilities. The World Bank introduced a new gender strategy in 2016. Gender and development was a ‘special theme’ for IDA18, IDA19 and IDA20, and we heard in interviews that the sustained emphasis on gender during these replenishments has led to “a sea change” in IDA’s focus on the issue. The UK government’s deepening emphasis on gender and development issues over the last decade is reflected in its global efforts to tackle violence against women, promote women’s rights and address sexual exploitation, abuse and harassment, and its emphasis on scaling up programming on girls’ education and maternal and reproductive health. (The UK’s strong stance on preventing violence against women and girls was documented in a previous ICAI review).

Regarding disability, we heard repeatedly in interviews with World Bank staff that the UK – including through its hosting of the 2018 Global Disability Summit – has been the driving force in ensuring that the World Bank made global commitments on disability and that IDA began addressing this agenda seriously during IDA19 (see paragraph 4.78).

Finally, there has been growing alignment between IDA and the UK in response to challenges posed by crisis risks faced by the poorest countries. Informed by experiences in responding to the Ebola outbreak in West Africa, the UK has increased its strategic emphasis on crisis preparedness and response, which have also been priorities for its engagement with the IDA18, IDA19 and IDA20 replenishments. Encouraged by the UK and others, IDA has also been expanding its ambitions on emergency response, by increasing the budget of its Crisis Response Window (to $2.5 billion during IDA19) and introducing new mechanisms for supporting early responses to food security crises and disease outbreaks. In IDA19 the Early Response Financing mechanism had an aggregate cap of $500 million, which with strong UK support was later raised to $1 billion, and retained in IDA20.

There has been weaker alignment between IDA and the UK regarding climate change, although this has begun to change

The UK government hoped that IDA19 (finalised in December 2019) would signal IDA’s increased ambitions on climate change, with commitments to scale up investments, analytics and dialogue with governments on issues such as climate risk insurance and delivering national strategies for tackling climate change. However, the IDA19 replenishment agreement fell short of most of these ambitions, and UK officials described the gains as marginal. Both UK government and World Bank officials noted that constraints on IDA’s ambitions on climate change were linked to resistance from the Trump administration in the US (2017-21) to multilateral support for robust climate change action (particularly in relation to mitigation).

Our country reviews likewise found relatively low visibility of climate change work in IDA country portfolios. In Bangladesh, although we identified two ongoing programmes dedicated to strengthening coastal resilience, these were approved during 2013-14 and we found few stand-alone climate-related projects that had been initiated since. We did, however, hear that resilience or adaptation actions were integrated into a range of other operations (such as constructing roads that can also act as dykes or school buildings that serve as cyclone shelters). We also heard that the Bank had only recently posted a climate and environment specialist to Bangladesh, although there was also a regional expertise hub for South Asia. In the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), home to the world’s second-largest rainforest and regionally important hydroelectric power potential, we also found a relatively low profile of historical programming related to climate change, even though these issues are closely linked to poverty and conflict in the country. This included $8.6 million disbursed to date through the 26-country Readiness Fund of the Forest Carbon Partnership Facility, which is supported by IDA. In Sierra Leone, a modest IDA programme had helped respond to a climate-related disaster (the Freetown mudslides), including through intensive tree-planting, and IDA was clearly building resilience components into the Integrated and Resilient Urban Mobility Project (IRUMP), but did not appear yet to prioritise climate change more widely.

Over the last year, however, helped by political change and the high profile of the COP-26 climate summit (held in the UK in late 2021), the World Bank’s ambitions on climate change have significantly increased. The Bank’s new Climate Action Plan (2021-25) was launched ahead of COP-26 (as encouraged by the UK) and includes the rollout of a new integrated country diagnostic tool (Country Climate and Development Reports). These are expected to support the integration of climate priorities into IDA operations. We were told that a major new climate programme is being planned in Bangladesh, and that the recently approved DRC Country Partnership Framework for 2022-26 aims to tackle climate change head-on, as an integral element of breaking out of the country’s long vicious cycle of poverty, violence and natural resource depletion.

Despite earlier constraints on IDA’s ambitions on climate change, the World Bank reports that the proportion of its operations reporting climate adaptation ‘co-benefits’ – in other words, climate-beneficial outcomes from programmes not necessarily labelled as climate action – have increased significantly in recent years. This suggests that IDA’s climate change adaptation efforts have been continuing, although we would question whether co-benefits should remain the main metric on which to make such judgments (see paragraphs 4.67 to 4.73).

IDA also provides useful complementarity to UK bilateral aid

As well as their strategic and thematic alignment across the spectrum of low-income countries and with UK priority development themes, IDA and UK bilateral aid also have different strengths and focus areas. In most cases, this makes IDA a valuable complement to UK aid.

IDA is active in 74 low-income countries, which is many more than the UK. In recent years the UK has focused on 25-30 priority countries with which it has closer historical relationships. This means that IDA helps to extend the influence of UK aid to a wider range of countries, including regions like the Sahel, which is a UK security priority but receives only modest amounts of UK aid. Small island states are another example of countries of interest to the UK in which IDA is more active.

IDA also works in a wider range of sectors than UK aid, with large-scale investments in agriculture, energy, transport and other economic sectors, as well as its extensive knowledge and analytical work. These strengths are reflected in analysis on the Bank in the 2016 Multilateral Development Review, which states that “[T]he Bank is the most important partner in delivering the Global Prosperity objective of the UK’s [official development assistance]…IDA alone accounts for over half DFID’s core multilateral spend on wealth creation”.

Partner governments have a strong voice in IDA country programmes and seem largely satisfied with IDA’s responsiveness

Most IDA resources are subject to recipient government choices and management. This is largely due to IDA’s country-by-country ‘performance-based allocation’ (PBA) model, a multi-year entitlement within which governments can exercise choices for specific operations. Moreover, as most IDA funding is transferred on a loan basis, the responsibility for sovereign borrowing tends to increase national ownership and scrutiny.

Government ministries, often coordinated through a country’s Ministry of Finance or equivalent, also have the primary responsibility for project implementation, unlike in the case of many bilateral aid programmes. This includes a lead role in management of social and environmental safeguards and adequate citizen consultation through national systems. The ministries may choose to contract some of their responsibilities out to local authorities, communities, the private sector and non-governmental organisations, but they cannot be obliged to do so.

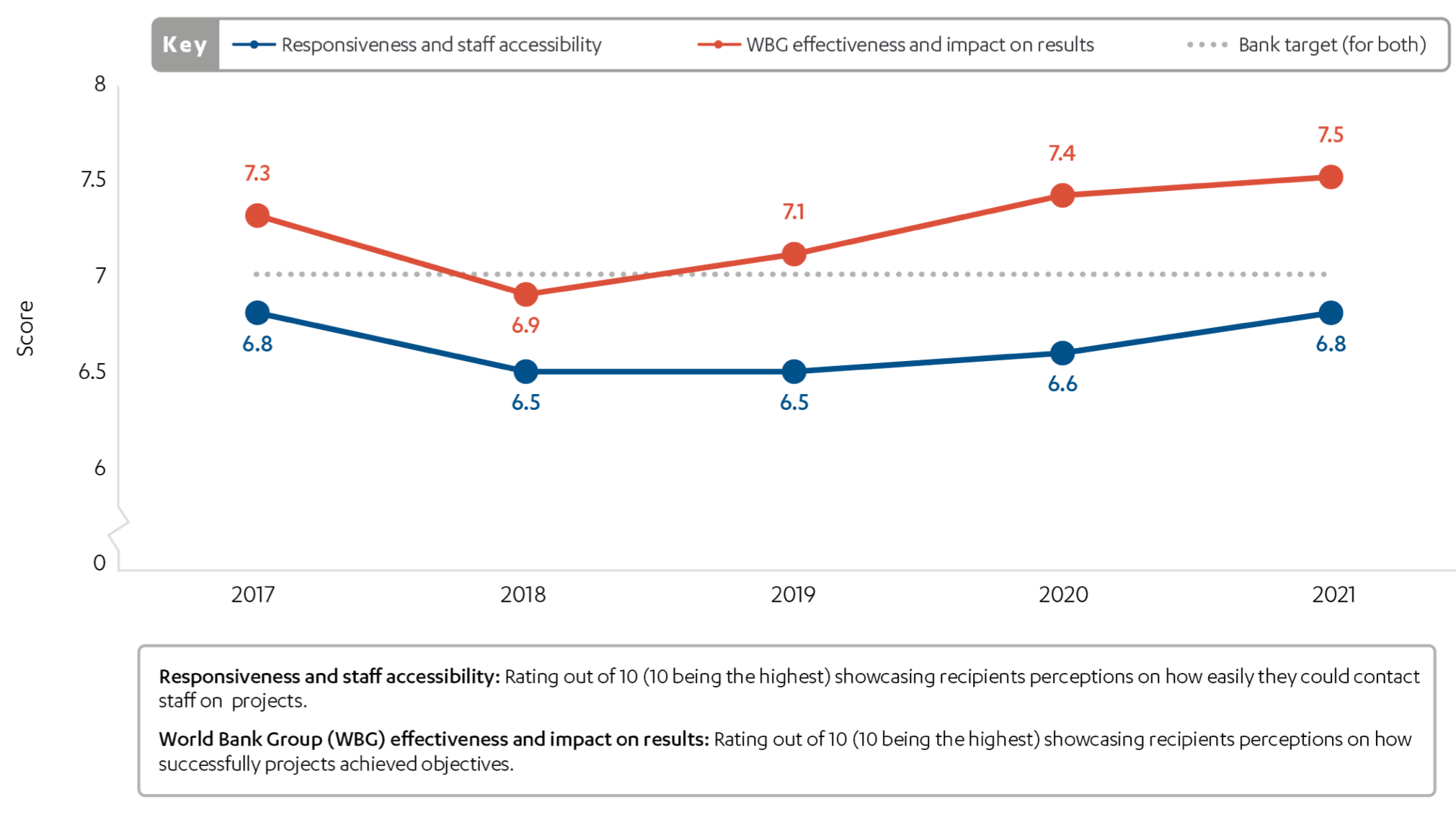

Government officials are regularly surveyed by the Bank about their views on the relationship. Partner governments are asked to score the Bank on a ten-point scale in relation to various criteria, including ‘responsiveness and staff accessibility’ and ‘effectiveness and impact on results’. In the year ending June 2021, the average score for the Bank on this measure was 6.8 for the former and 7.5 for the latter against a target of 7 (see Figure 6). This suggests that partner country governments are largely satisfied with the Bank’s responsiveness and impact.

Figure 6: Average scores from World Bank country opinion surveys that track perceptions and views of clients, 2017-21

We found a similar picture of satisfaction with the role of IDA in our case study countries, with some nuances. In Sierra Leone, prompt IDA support in 2020 was directly credited with preventing a severe economic downturn under the impact of COVID-19, and government stakeholders reported that the Bank responded rapidly to the government’s request for support in response to the 2017 mudslides. In DRC, in the early stages of its support for vaccine rollout, IDA was responsive to the government’s changed preference for a vaccine given concerns with vaccine hesitancy. However, a 2019 perception survey found that the Bank’s effectiveness had declined since 2016 and it needed to improve collaboration with government and donor partners.

A common critique of the national ownership of World Bank operations relates to the conditions that are applied to these operations, which are sometimes said to constrain democratic decision making (see Section 3). A study of World Bank development policy operations, which provided budget support during the COVID-19 pandemic, found that recipient governments were required to enact, on average, eight policy reforms to secure funding, only a fraction of which were directly relevant to the COVID-19 crisis. However, the Bank’s primary response to COVID-19 used investment-type instruments which did not require prior policy actions. When interviewed, Washington civil society representatives stated that, under the current World Bank presidency (which began in April 2019), World Bank conditions have become more extensive. Indeed, in Sierra Leone, the series of three Productivity and Transparency Support programmes have pushed forward reform in a range of difficult areas, including fisheries and agriculture.

However, none of the borrower government representatives (including African IDA Board chairs and senior Sierra Leone government officials) or civil society representatives that we interviewed expressed such concerns. They did not believe that recent prior conditions, where applicable, were unreasonable or at odds with national priorities, and the health-related COVID-19 response in both cases was funded through unconditional emergency instruments anyway. ‘Development policy financing’, that is, broad- based budget support linked to policy reforms, has not yet been approved for DRC. However civil society consultations on the new Country Partnership Framework (CPF) for DRC, a statement of IDA programme priorities for 2022-26, have highlighted concerns over corruption and inadequate public funding for social services and advocated for targeted reforms to improve the situation. These reforms presumably imply a more, not less, conditional approach in the future.

At the central level, IDA’s Boards of Governors and Directors are dominated by Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development countries, which have the (theoretical) voting strength to block borrowing country agendas. However, in practice IDA Board decisions are taken on a consensus basis. Efforts have also been made to improve partner country voice in recent IDA replenishment processes by introducing borrower government representatives, which now number 14, compared to 25 Board seats and Governors. Those whom we interviewed welcomed these developments and identified a number of policy agendas that they had influenced in recent replenishments. These included the establishment and scaling-up of regional initiatives, the introduction of the Private Sector Window and the agreement to prioritise ‘jobs and economic transformation’ in IDA18 and IDA19.

Despite recent attempts to strengthen citizen engagement and voice, practice still lags behind ambition

In 2013-14, the Bank introduced some demanding new standards and guidelines for citizen engagement in World Bank operations. These included a requirement for consultations ahead of country strategy processes and the approval of individual operations, as well as a commitment to integrating ‘beneficiary’ feedback (the World Bank’s terminology) into all investment projects where ‘beneficiaries’ can be clearly identified, by fiscal year 2018.

An Independent Evaluation Group (IEG) progress review in 2018 found considerable, but uneven and incomplete, achievement against this commitment. This mixed record was confirmed in our country case studies and project reviews. The number of these interactions is increasing, but they are, on average, shallower than originally intended. IEG’s finding from 2018 appears still to hold: “Mechanisms implying a light degree of engagement (“informing and “consulting”) are much more frequent than more intense forms of engagement (“collaborating” and “empowering”).”

IEG also found that only a small fraction of CPFs report on the feedback from citizens received during these consultations, and fewer still documented how that feedback was integrated into the final strategy, meaning that the accountability loop was rarely closed.

Among our two main country case studies, the nature of consultation and indications of how views shared in these consultations had informed country priorities varied. In the case of Sierra Leone, its CPF indicates that a structured process of consultation took place over two rounds and it elaborates how stakeholder views shaped this framework. Our own discussions with civil society, however, raised questions about the depth of consultations. In the case of DRC, its CPF suggests that a more modest formal consultative process was undertaken, and the document fails to clarify how the outcomes of these consultations shaped the CPF. In interviews, we were informed that formal consultations in DRC were constrained by the need to secure buy-in for a new strategic approach within the Bank before external discussions could begin, and that informal dialogue on the CPF was also important.

Our review of programmes in Niger identified some significant examples of engaging local communities in the design and delivery of programmes. The Climate Smart Agriculture Support Project supported communes in developing their own plans to invest in promoting climate resilience through a bottom-up participatory approach. The Refugees and Host Communities Support Project used an independent feedback mechanism to collect information about progress on deliverables every six months directly from people expected to benefit, either face-to-face through interviews or by phone, which helped to direct ongoing delivery.

We were informed in interviews that for fast-tracked COVID-19 response projects, consultation requirements were reduced. For example, in DRC, the stakeholder engagement plan (SEP) (typically a requirement for Board approval), for the COVID-19 IDA programme was explicitly set aside to speed up programming with a commitment to deliver the SEP in full within two months of Board approval. However, IDA staff acknowledged that the full SEP was never subsequently carried out for this programme. The additional financing to expand this programme’s cover to vaccines in 2021 did benefit from fuller stakeholder engagement, however.

Several civil society organisations (CSOs) that we spoke to also found that their opportunities to engage with Bank staff were still limited, and that consultations with them were sometimes perceived as formalistic or one-directional. These constraints may, however, have been temporarily aggravated by COVID-19 travel restrictions.

For example, we were told by Washington-based CSO representatives that a full draft of the Bank’s 2021 Climate Change Action Plan (CCAP) was only shared with them at a very late stage, precluding meaningful input on their part. The Bank did, however, inform us that they held a four-month-long consultation process on the CCAP, which generated more than 500 comments that were subsequently shared with the authors of the draft action plan and with Bank management, thereby helping to shape the final plan.

Involvement of CSOs in the implementation or monitoring of IDA programmes is mostly on an ad hoc basis, outside the formal procurement process, which can be difficult for CSOs to navigate. CSO involvement is, in any case, not a substitute for broader citizen engagement, as we saw in country reviews. We return to citizen engagement in the context of environmental and social safeguards in paragraphs 4.85 to 4.94 below.

Conclusions on relevance

Our country reviews, literature review and strategic and thematic assessments all confirm IDA’s high relevance and alignment to UK development priorities. IDA shares the UK’s strong poverty focus, while its broader geographic and thematic footprint provides complementarity.

IDA began its substantive climate change focus during IDA16. It has since developed this further, especially since IDA19 and particularly with regard to resilience and adaptation, but less so in terms of headline mitigation action, especially during the Trump administration in the US. It works closely with partner country governments, who affirm their ownership of IDA programme choices and implementation, and have a growing voice in replenishments. It is becoming more open to direct citizen engagement, but this remains a work in progress.

We therefore award a green-amber score for relevance.

Effectiveness: How effective is IDA’s support for partner countries?

This section explores evidence on the effectiveness of IDA programmes in delivering development results at the corporate level and across the priority themes for this review. The World Bank is a highly scrutinised institution, with its own Independent Evaluation Group (IEG) delivering an extensive array of evaluations, and a range of external actors (including academics, think-tanks and CSOs) also carrying out independent analysis of the Bank’s operations. As a result, this section draws on the large volume of available independent and semi-independent analysis of IDA’s effectiveness. It is also informed by our country case studies (including evidence from programme reviews, citizen engagement and interviews) to provide triangulation and more detailed evidence of in-country effectiveness.

IDA’s internal results indicators are generally strong and improving, but refer to outputs and intermediate outcomes more than to longer-term impact, which is harder to track and attribute to aid interventions

We first review the overall IDA framework for reporting results, especially the extent to which IDA- supported projects meet their multiple development objectives, and how these are set. We then discuss how these objectives relate to intermediate and long-term (or final) outcomes, how the latter may also be informed by development impact evaluations, and the inherent tension between ensuring short-term management accountability and maintaining a longer-term outcome focus. Finally, we look at how agreed IDA policy reforms are tracked and reported. However, a cautionary note is needed at the outset: it is very difficult, if not impossible, to attribute rigorously any large body of high-level development outcomes, such as IDA’s objectives, to arrays of individual interventions.

There are two monitoring processes that generate data on IDA’s effectiveness. First, there are project and country portfolio assessment ratings that are produced for all World Bank projects and countries, and which score performance against a range of criteria. Second, the IDA results measurement system (RMS) reports against a wide range of indicators at three levels: i) country progress, ii) IDA-supported results (which also draws on project assessment scores), and iii) IDA’s operational and organisational effectiveness (which includes progress on reforms and actions agreed with shareholders through the IDA replenishment process).

IDA projects report on whether they have achieved their planned outcomes on completion and are scored on a six-point scale. These scores are checked by IEG, which reports directly to the Board. About a quarter of these operations are subject to an in-depth IEG review, usually involving additional information sources and country visits. Results are aggregated and reported by period, country, and theme or sector.

The proportion of IDA projects closing in financial year (FY) 2019-20, which were rated ‘moderately satisfactory or better’ (scoring 4/6 or above) was 86%. This was a historical high, up from 75% in FY2018-19, and an average of just 68% during 2011-16 (see Figure 7). IEG confirmed to us that underlying performance, scored like-for-like, improved across all sectors and regions, and that the improved ratings were not a by-product of disruption to project supervision during the pandemic.

Figure 7: IDA projects rated as ‘moderately successful’ or better, 2011-20

However, IEG’s Results and Performance Report 2020 adds an important caveat, by noting that there is limited independent scrutiny of results indicators, and that not all project objectives are associated with results indicators (especially ‘institutional strengthening’ objectives). It also notes that “many projects rely on weak, indirect, or anecdotal evidence with an overreliance on measured outputs over outcomes”.