UK aid in a conflict-affected country: Reducing conflict and fragility in Somalia

ICAI Score

A positive contribution by the UK to state-building and stability in Somalia, with significant achievements but scope for improvement in several important areas.

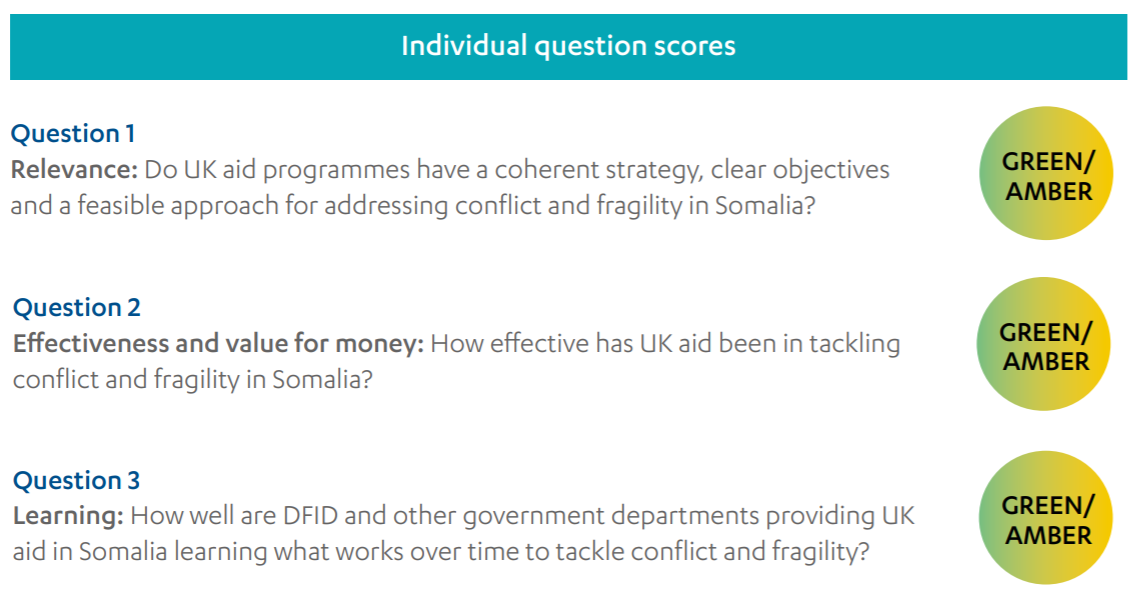

As the world’s most fragile state, Somalia presents an extremely challenging environment in which to deliver aid. Under a National Security Council strategy and within the framework of international cooperation agreements on aid to Somalia, UK aid aims to build a viable political settlement and a more stable, peaceful and prosperous Somalia. We found that aid programmes were well aligned to the UK strategy, and helped to address conflict and fragility in a range of ways. The UK has developed its ability to operate in Somalia by broadening its supplier base to include private sector companies and by developing special arrangements for monitoring and evaluating its investments. It has adapted its strategy and approach in response to experience and changing conditions, and the aid programme has adapted accordingly. It is difficult to be certain of the prospects of long-term success in such a challenging environment, but the UK’s strategy appears both credible and feasible, and has attracted strong international support.

The UK departments delivering aid, mainly DFID and the FCO, are working well together, although not quite yet as ‘One HMG’. Most programmes show a strong record of delivering at output level, though DFID is better able to evidence its high-level contribution than the smaller and shorter FCO-led aid programmes. There is mixed evidence of achievement of outcomes across the portfolios, due in part to weaknesses in identifying and tracking measurable outcomes. However, we heard credible and consistent accounts from a range of very senior stakeholders that UK aid programmes – and the diplomatic influence they generate – had made important contributions to achieving a viable political settlement. The government could, however, do better at articulating a consistent set of peace- and stability-related objectives and how UK aid programming will contribute to them, underpinned by a more developed understanding of the complex drivers of conflict which the aid is seeking to address.

We found a good focus on learning in the DFID country office, which is becoming more systematic, and evidence of continuing improvement in aid management practices. We were concerned that programmes intended to be innovative or adaptive were not designed with a strong enough learning orientation, and to find that potentially valuable learning from past Conflict Pool projects in Somalia is lost or inaccessible. However, there is good evidence that the Somalia experience has helped to inform the UK’s overall approach to using aid to address conflict and fragility.

Overall, the performance warrants a green-amber rating, but there are several important areas where improvement is required.

Executive Summary

Somalia is the world’s most fragile state. After decades of coflict and instability, it is now on the brink of another famine that could kill many thousands of people.

For the UK government, Somalia is a strategically important country. It sits within a troubled region sometimes referred to as the “arc of instability”.1 The National Security Council (NSC) strategy for Somalia addresses UK national security interests, linked to counter-terrorism, as well as development and humanitarian goals. The UK is the second-biggest donor to Somalia, at approximately £122 million in 2015,2 and has played a leading role in international efforts to build a viable political settlement and a functioning state. The UK government recently announced £100 million in humanitarian aid, in response to a famine warning.3 High levels of insecurity make Somalia a very challenging operating environment, with most aid managed remotely from neighbouring countries.

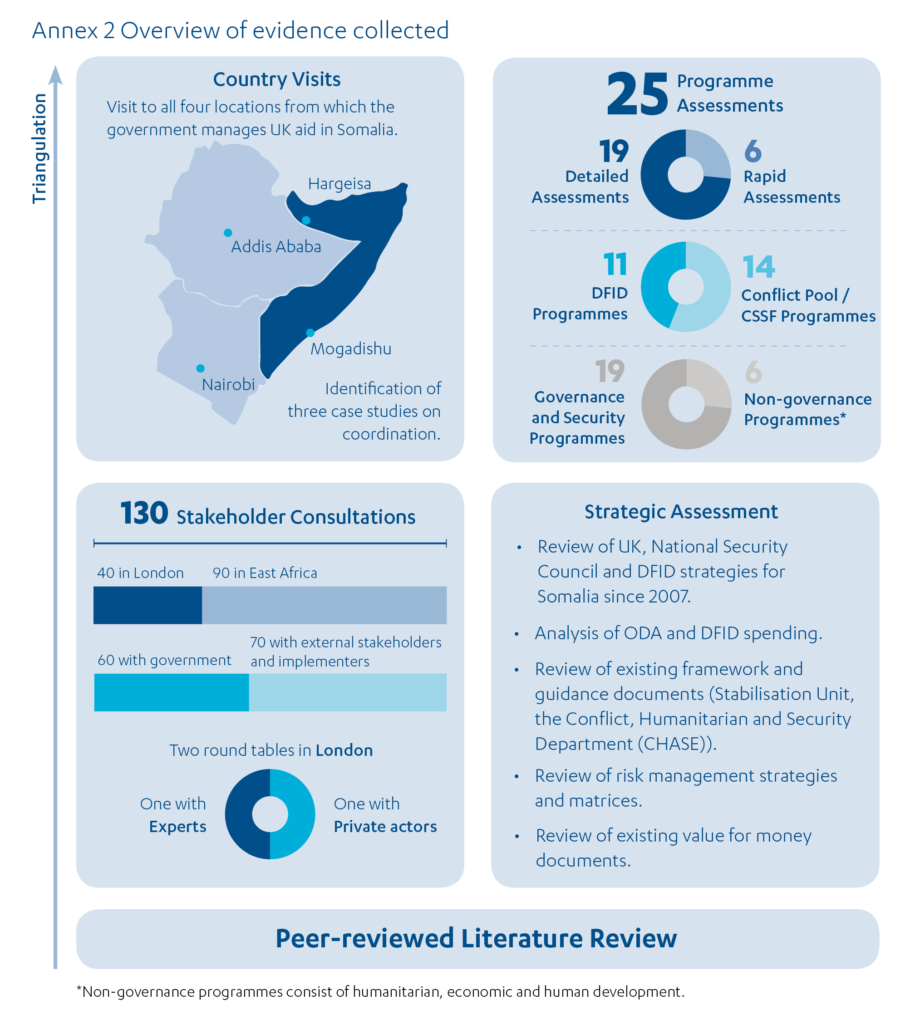

This review assesses the performance of the UK aid programme over the past five years in tackling conflict and fragility in Somalia. It looks at DFID programmes and at projects funded through the Conflict, Stability and Security Fund (CSSF) and its predecessor, the Conflict Pool. It explores the relevance of the overall approach, the effectiveness of aid delivery and the quality of learning. Our methodology included a desk review of a sample of 25 programmes and projects, including all of DFID’s major governance and security programmes, and interviews with 130 key stakeholders in the UK, Somalia and neighbouring countries.

How relevant is the UK approach in Somalia?

A decade ago, UK aid to Somalia consisted mainly of humanitarian assistance and funding for limited UN development interventions in the few accessible parts of the country. Around five years ago, motivated by concerns about piracy o Somalia’s coast and the threat of terrorism, the UK developed an ambitious, cross- departmental strategy, under the authority of the NSC, to help achieve a viable political settlement and build a more stable, peaceful and prosperous Somalia. The strategy combines humanitarian and development goals with a concern for UK security interests. It has a focus on areas recovered from the Islamist insurgent group Al-Shabaab for the Federal Government by the African Union-led peacekeeping force, AMISOM.

We found that the UK aid programme in Somalia is well aligned to the NSC strategy and that it reports against the NSC’s results framework. It contributes to promoting security within Somalia through investments in policing, security sector reform and alternative livelihoods for disbanded militia, and by directing aid to stabilise areas newly liberated from Al-Shabaab. It promotes state-building through support for elections, capacity-building in national revenue management, and the facilitation of local peace agreements. UK aid also supports economic policy, infrastructure, livelihoods, health and nutrition and empowering women, and provides humanitarian assistance to Somalis (prior to the 2017 commitments responding to the increasing risk of famine this accounted for around 40% of the aid budget), although these programmes were not the focus of this review.

There has been an important development in the UK approach towards state-building. In 2011 and 2012 the focus was on support for the new Federal Government, building on the provisionally agreed constitution.

By late 2013 it had become clear that the Federal Government was unable to establish stable authority over territory recovered from Al-Shabaab control. The UK therefore adapted its approach, increasing its efforts with local leaders in these areas, in an attempt to bring them within the emerging federal structure. We found that the aid programme has proved flexible and adaptive to this development. It has supported emerging federal entities with security and justice initiatives and community-driven development, while helping to broker agreements with the Federal Government. The strategy entails various risks and it will not be possible to fully assess its success except in the longer term, when its traction with the Somali general public can be determined empirically. The UK approach is widely accepted by experts and by non-UK stakeholders, including the UN, and is now being followed by other international actors, demonstrating the UK’s leadership role in Somalia.

Beyond the governance and security areas, DFID programmes may contribute indirectly to peace and stability by creating jobs, improving public services or providing humanitarian support to vulnerable populations. However, these programmes are not designed and delivered so as to maximise their contribution to peace and stability. DFID does not yet have a settled position on the extent to which development programmes working in situations of conflict and fragility should actively seek opportunities to promote stability, or how they should do this. DFID aims to ensure that all programmes are politically aware and avoid inadvertent harm. Additional, more proactive, peace and stability objectives for development programmes would place a further premium on the need for a more comprehensive, shared analysis of the drivers of conflict at a local and national level.

Within a broadly positive picture, we have a number of other concerns about the UK approach. We found that inclusion, human rights and gender equality were not sufficiently mainstreamed across the aid programme. In a few instances, we also encountered tensions between UK security needs and development goals, particularly around the approach to institution-building in the security sector.

Overall, we awarded the aid programme a green-amber rating for relevance, in view of the good level of alignment behind a plausible strategy and the adaptive response to emerging challenges.

How effective is UK aid delivery in Somalia?

Over the past five years, the UK government has invested in building up its capacity to deliver aid in the challenging operating conditions in Somalia. To diversify its delivery channels beyond multilateral institutions, DFID has developed a network of international and local private sector suppliers able to operate across Somalia. DFID has also invested in an independent monitoring capability, to generate information on local conditions and verify that aid is reaching the intended beneficiaries. This greatly enhanced delivery capacity has made the aid programme more nimble and more flexible in responding to peace-building opportunities – including by directing aid into territory newly recovered from Al-Shabaab control. A wide range of experts and senior external stakeholders agreed that this shift had led to more effective delivery, and other donors have demonstrated their confidence in this UK development by contributing funding to DFID’s contractor-delivered programmes.

The new approach also gives the UK greater capacity to align with NSC objectives in the aid programme, including on UK security. There are risks associated with the use of contractors that could be managed more actively. Contractors need greater support and political oversight, and the UK needs agreements with Somali counterparts to ensure that contractors are accountable, collaborative and have the appropriate authority to operate.

We found that UK aid programmes in Somalia have a good record of delivering their planned activities and outputs. Of the 25 programmes in our sample, 18 have achieved or are likely to achieve their outputs; for four it is too early to tell, while three appear unlikely to succeed. Given the very difficult environment, this is good performance on delivery. There is a mixed picture of achievement at outcome level, due in a large part to poor definition of outcome indicators and a lack of meaningful performance data. We acknowledge the challenges of definition and measurement in this difficult operating environment, particularly when it comes to enduring changes in conflict and fragility, but we see scope for UK aid to improve its measurement of outcomes.

Attributing responsibility for improvements in the stability of Somalia is difficult. Nonetheless, we heard credible and consistent accounts from a range of senior stakeholders, from the donor community to Somali officials and the UN, that UK aid programmes – and the diplomatic access and influence they generate – had made important contributions to the search for a viable political settlement. For example, the Somalia Stability Fund has increasingly supported political negotiations around the emerging federal structure, using its flexible budget to engage with local authorities. And the Basic Policing Programme has helped establish an electronic payroll system for sub-national police forces and agreements on how they relate to the central security apparatus. The UK also contributed substantially to supporting the recent elections which, though imperfect in many respects, achieved Somalia’s first peaceful transition of power for over half a century. There has so far been only limited progress on establishing an overall security apparatus under democratic control, or an effective rule of law.

Measuring the impact of individual programmes on conflict and fragility is also challenging, and both DFID and the CSSF are only at an early stage in considering how to do this. A clear framework of conflict- and fragility- related outcomes underpinning the NSC strategy has yet to be established, and most programmes are not precise about which aspects of stability they hope to promote. The challenge is more acute for the CSSF, which currently generates less useful performance data. FCO managers told us that diplomatic access and influence were often the most important results of CSSF projects. We also found that CSSF managers had been quick to identify and terminate or downscale unsuccessful projects, so that the funds could be reallocated. Nonetheless we believe that the CSSF would benefit from better measurement and documentation of results, both direct and indirect.

Our findings on effectiveness are complex, with some strong performance in several important areas, counterbalanced by others where substantial improvement is needed. In addition, it is challenging to characterise performance across the DFID and CSSF portfolios when the CSSF is clearly at a much earlier stage in developing its programme management systems – it has some progress to make, although there is evidence of improvement. Overall, we have awarded a green-amber rating for effectiveness, to reflect the substantial improvements in delivery capacity in a very difficult environment, a good track record in delivering activities and outputs, and some significant (though early) contributions to achieving a new political settlement.

How well is the aid programme learning from its experience in Somalia

We found that DFID Somalia has a good focus on learning at the country office level, which is becoming more systematic. It shares with the DFID Kenya office the support of an Accountability and Results Team, which has promoted improvements in programme management practice through training, guidance and internal peer assessment of annual reviews. It compiles and disseminates lessons identified in annual reviews, and has developed a value for money action plan. We saw evidence of improved practices in a number of areas, including financial assurance and fraud prevention.

Both DFID and the CSSF could do more to ensure that programmes which are explicitly innovative or adaptive in nature are designed with a strong learning orientation. Clearer incentives are needed to report and share the failures which one would expect to arise quite often from experimental programming. While we acknowledge that this can be costly and difficult in a context like Somalia, we also see scope for greater use of independent evaluations as well as internal reviews to inform adaptive programming. DFID also needs to ensure that all programmes maximise use of its investments in learning, especially its third party monitoring resource. Although Conflict Pool programmes in Somalia amounted to only a small proportion of overall spending, we were disappointed to find that potentially valuable learning from some past Conflict Pool programmes is lost or inaccessible.

We also assessed whether learning from Somalia had informed the UK’s wider approach to addressing conflict and fragility through aid. DFID has recently updated its central guidance on peace-building and state-building. Positively, we found that the new Building Stability Framework draws on the Somalia experience in stressing the importance of working with a diversity of local actors, rather than primarily with the central state, in the search for a ‘good enough’ political settlement.

We awarded a green-amber rating for learning, in recognition of continuous improvement in a range of areas, but with the important caveat that a more active learning approach needs to be built into programmes to support adaptive management.

Conclusions and recommendations

Our overall rating of green-amber reflects some exceptional performance by the responsible departments in tackling the enormous challenges involved in using aid to address conflict and fragility in Somalia. The UK’s strategy of using aid to support peace-building and state-building has evolved over time in response to lessons learned, and has attracted strong support from other international actors. The UK has significantly improved its ability to deliver aid in Somalia, enabling a more rapid and flexible response to a dynamic situation. There is impressive performance at output level, and evidence that UK aid has helped to put in place some of the building blocks of a new political settlement. There is also good evidence of learning at the country level, and this has been shared with DFID in other fragile and conflict-affected states.

However, performance is mixed in a number of other areas, and we have several important recommendations for how the aid response could be improved in the future.

Recommendation 1

Government departments delivering aid in Somalia should develop a more systematic and shared understanding of the drivers of conflict and fragility there, to help target aid programmes and ensure that they ‘do no harm’.

Recommendation 2

More needs to be done to promote inclusion and human rights across the portfolio of UK aid to Somalia.

Recommendation 3

Where economic development and humanitarian programmes are also intended to contribute to peace- and stability-related outcomes, this should be specified as part of their objectives and built into their associated delivery plans and monitoring and reporting arrangements.

Recommendation 4

DFID and the CSSF should ensure that they provide sufficient oversight and political support to their private contractors, and agree with their counterpart government authorities memoranda of understanding to provide a clear framework of accountability.

Recommendation 5

The CSSF should strengthen its operational management focus on monitoring, evaluation and learning, with realistic results frameworks which recognise indirect benefits such as diplomatic access and influence as well as more tangible programme outputs. It should be clearer whether projects are pilots or intended to deliver results at a significant scale.

Recommendation 6

All CSSF activities funded as ODA should have clear developmental objectives. Work on rule of law institutions should be well coordinated and aim at sustainability and national ownership.

Recommendation 7

Departments operating in Somalia should adopt a more systematic approach to the collection and dissemination of learning on what works in addressing conflict and fragility, particularly for programmes that are intended to be experimental or adaptive in nature.

Recommendation 8

DFID and the FCO should explore opportunities for greater integration of working space, systems and processes to make ‘One HMG’ even more of a reality for UK aid in Somalia.

Introduction

Purpose and scope

This review is being published at a critical moment for Somalia’s recent development. A parliamentary and presidential election process has just culminated in a largely peaceful transition from one national government to another – the first such transition of power for over half a century. At the same time, Somalia is on the brink of another famine, while the security situation remains precarious. On 11 May 2017, the UK hosted another major international conference on Somalia.

Somalia is a strategically important country for the UK, with numerous historical and trading links, and is situated within a set of interlocking regional conflicts sometimes described as the “arc of instability”.4 There is a UK National Security Council (NSC) strategy for the country, which the aid programme supports. The UK has played a major role in some of the key peace-building and state-building processes in Somalia over the past decade.

Our review assesses the performance of the UK aid programme in tackling conflict and reducing fragility in Somalia, focusing mainly on the period from 2011 onwards. We examine the evolution of the overall approach, and review a selection of bilateral programmes managed by DFID Somalia and projects funded through the Conflict, Stability and Security Fund (CSSF) and its predecessor, the Conflict Pool. Given the highly insecure environment, much of the aid programme is managed remotely from Nairobi in neighbouring Kenya. We look at the effectiveness of the delivering mechanisms in overcoming access constraints.

This is a performance review, probing whether the design and delivery of programmes in Somalia are likely to be effective at reducing conflict and fragility. Our review questions are set out in Table 1.

Box 1: What is an ICAI performance review?

ICAI performance reviews look at how efficiently and effectively UK aid is being spent on a particular area, and whether it is likely to make a difference to its intended beneficiaries. Performance reviews aim to identify improvements in processes and ways of working to increase effectiveness and value for money.

Other types of ICAI review include impact reviews, which examine results claims made for UK aid to assess their credibility and their significance for the intended beneficiaries, and learning reviews, which explore how knowledge is generated in novel areas and translated into credible programming.

Table 1: Our review questions

| Review criteria and questions |

|---|

| 1. Relevance: Does UK aid have a coherent strategy, clear objectives and a feasible approach for addressing con ict and fragility in Somalia? |

| 2. Effectiveness and value for money: How effective has UK aid been in tackling conflict and fragility in Somalia? |

| 3. Learning: How well are DFID and other government departments providing aid in Somalia learning what works over time to tackle con ict and fragility? |

Methodology

There are four methodological components to our review:

- We conducted a literature review to survey the available evidence on what works in using aid to address conflict and fragility, and the difficulties involved in measuring impact in Somalia and in fragile and conflict-affected states more generally.

- We conducted a strategic review, analysing UK government strategies, policies and results frameworks. We conducted in-depth interviews with UK government stakeholders and external partners. We mapped the aid portfolio against its high-level objectives, to assess coherence, and assessed whether it was based on a sound analysis of the drivers of conflict and fragility in Somalia.

- We conducted key informant interviews with more than 130 stakeholders to explore the overall strategy and the relevance and effectiveness of specific programmes. Approximately half of these were from the UK government; the remainder were external to the UK government and included other donors, international organisations, Somali government officials and independent observers. These detailed consultations took place in London, in Somalia and in UK posts in Nairobi and Addis Ababa.

- We selected a sample of 25 UK programmes and projects5 for desk review from the activities of DFID, the Conflict Pool and the CSSF from 2011 to 2016. A list of all the programmes reviewed is included in Annex 3. Our sample covered almost 90% by value of DFID’s in-country bilateral programming in Somalia over the period, and included all of DFID’s major governance and security programmes. We reviewed six DFID programmes outside the governance portfolio to assess their contribution to peace and stability. We also reviewed 14 programmes funded through the Conflict Pool and the CSSF in Somalia, covering 40% of all relevant projects over that time period.6 For each programme, we reviewed programme documentation and independent reviews and evaluations where available. For the programmes directly targeting conflict and fragility, we also conducted in- depth interviews with the responsible UK government staff and implementing partners.

Box 2: Limitations of our methodology

Because of the severe restrictions on our access to many parts of Somalia and to the beneficiaries themselves, our assessments relied heavily on monitoring and evaluation information produced by or for the programmes themselves. We sought to reduce the risk of bias by comparing the information coming from other counterparts, development partners and programme implementers, providing a level of triangulation. However, we had only limited capacity to reach independent conclusions about programme effectiveness where the programme data turned out to be incomplete or inaccurate. Lack of primary data on Somalia also made it difficult to gauge the country’s trajectory towards peace and stability. We have indicated wherever it was not possible to draw robust conclusions about programme effectiveness.

Background

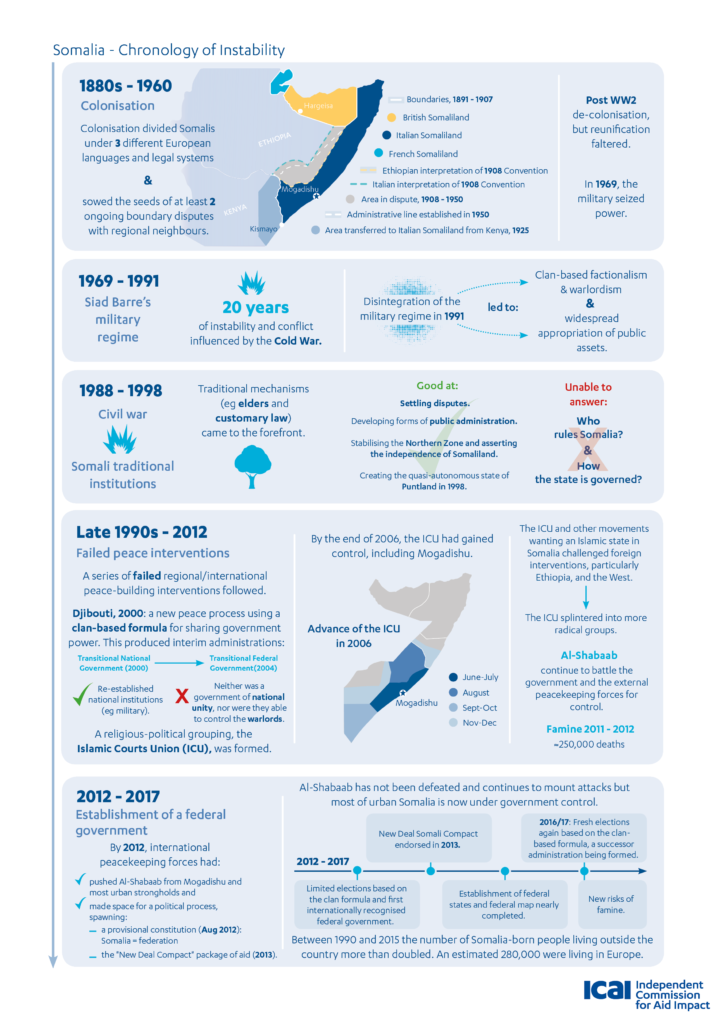

Some progress, after decades of instability

Somalia has experienced serious unrest and instability for the last half-century, ranking for the past decade as the world’s most fragile state.7 It has suffered periods of military dictatorship, civil war, state collapse, clan-related warlordism and now conflict with the extremist group Al-Shabaab. There has been a history of intervention by Western and regional powers and, since 2011, a peace-enforcement mission by the African Union, AMISOM (see Box 3).

Box 3: The African Union Mission in Somalia

The African Union Mission in Somalia (AMISOM) currently has over 22,000 troops deployed in Somalia under an African Union mandate.8 They work alongside the Somali National Army to recapture territory from Al-Shabaab, the main insurgent group fighting the government. Al-Shabaab has links to Al-Qaeda and is designated a terrorist organisation by the UK.9 The peacekeeping mission aims to assist the government to re-establish peace and the rule of law.

Commentators agree that the causes of conflict are complex and deep-seated (see the timeline in Figure 1). They include contradictions between a modern state, fractious kinship systems and a Somali pastoral culture in which power is highly dispersed.10

Commentators agree that the causes of conflict are complex and deep-seated (see the timeline in Figure 1). They include contradictions between a modern state, fractious kinship systems and a Somali pastoral culture in which power is highly dispersed.10

Box 4: The New Deal and the Somali Compact

The New Deal is an agreement between fragile and conflict-affected states, international development partners and civil society to improve current development policy and practice in these countries. It was signed by development partners and 19 fragile and conflict-affected countries at the Fourth High Level Forum on Aid Effectiveness at Busan, South Korea, in November 2011. Donor countries committed themselves to pursuing more political ways of working to address the root causes of conflict and fragility and to channelling investments in fragile states in line with basic but adapted aid effectiveness principles.11

The New Deal Somali Compact, endorsed in Brussels in 2013 and in place from 2014 to 2016, set out a partnership framework between Somali authorities, civil society in Somalia and the international community. The five Peace-building and State-building Goals for Somalia are:

Inclusive politics: achieve a stable and peaceful Somalia through inclusive political processes.

Security: establish uni ed, capable, accountable and rights-based Somali federal security institutions providing basic safety and security for citizens.

Justice: establish independent and accountable justice institutions capable of addressing the justice needs of the people of Somalia.

Economic foundations: revitalise and expand the Somali economy with a focus on livelihood enhancement, employment generation and broad-based inclusive growth.

Revenue and services: increase the delivery of equitable, affordable and sustainable services that promote national peace and reconciliation among Somalia’s regions and citizens and enhance transparent and accountable revenue generation, equitable distribution and sharing of public resources.12

The Somali Compact expired in 2016 and international partners are discussing with Somalia’s new government the principles of the next partnership framework.

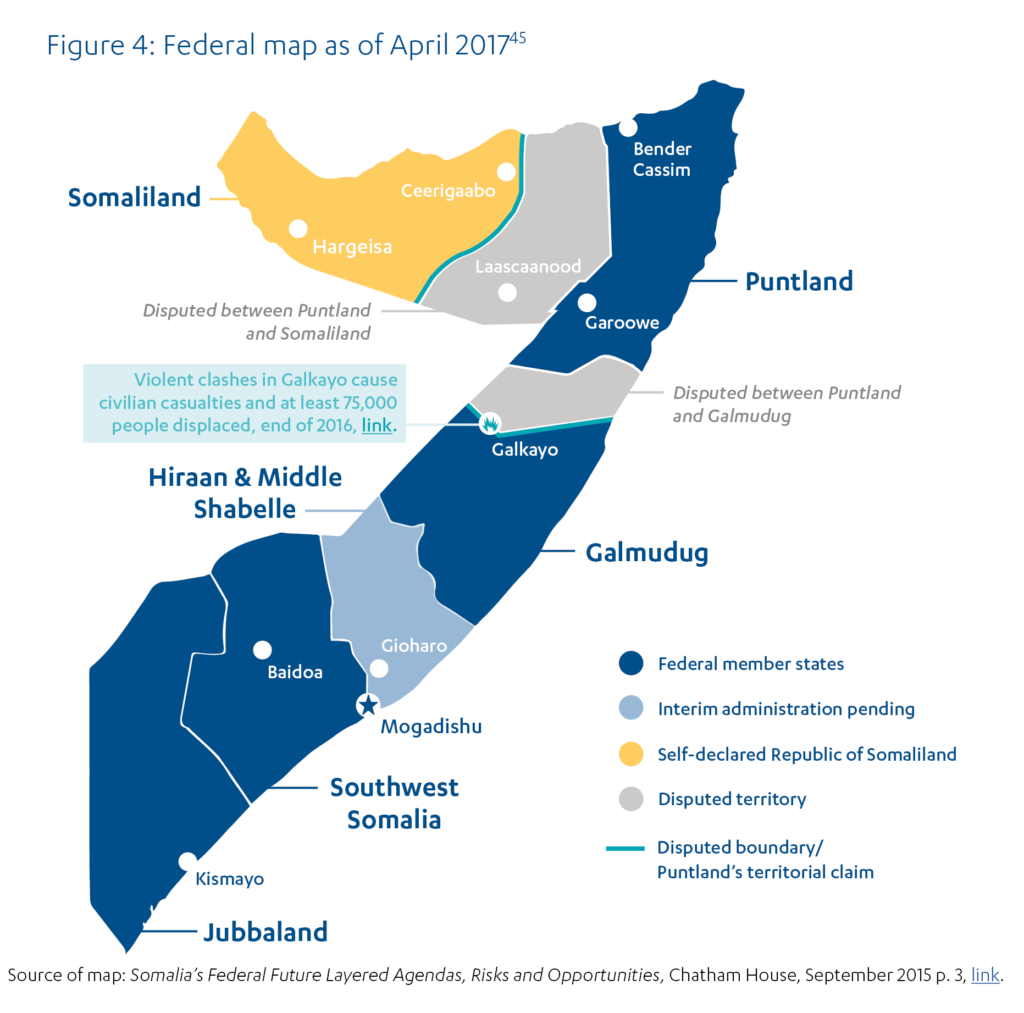

At present there is a loose federal structure, with a clan-based power-sharing formula, and an internationally recognised Federal Government which has regained control over Mogadishu and most urban areas. The Republic of Somaliland in the north, which seceded in May 1991 (see Box 5), and the quasi-autonomous state of Puntland are both functionally independent. In the south, the Federal Government is in conflict with various insurgent groups, including Al-Shabaab. Elections were held in late 2016 and early 2017, leading to a new president and government.

Box 5: Somaliland

The former British Protectorate of Somaliland declared independence from the rest of Somalia in 1991 and has achieved comparatively high levels of peace and stability, including a functioning government and three democratic elections. Without prejudging its status, the UK has engaged directly with Somaliland to support its stable and sustainable development and to counter terrorist threats. Somaliland remains impoverished and in need of development assistance, but relatively high levels of stability and access have allowed some pioneering developments in the rule of law, governance and economic development to be trialled there.

The Somali people have paid a heavy price for the long conflict. Of a population of approximately 12.3 million,13 1.1 million are internally displaced and another million are overseas.14 Somalia has a young population, with 70% under 30, but two thirds of people aged 19 to 24 are unemployed and an estimated 43% of the population live on less than $1 a day.15 Conflict and instability have led to persistent humanitarian crises, including a serious famine in 2011. At the end of 2016, Somali officials and the international community raised the alarm on an impending new famine. It is estimated that 6.3 million people are currently in need of humanitarian assistance.16

UK aid to Somalia has increased significantly since 2009

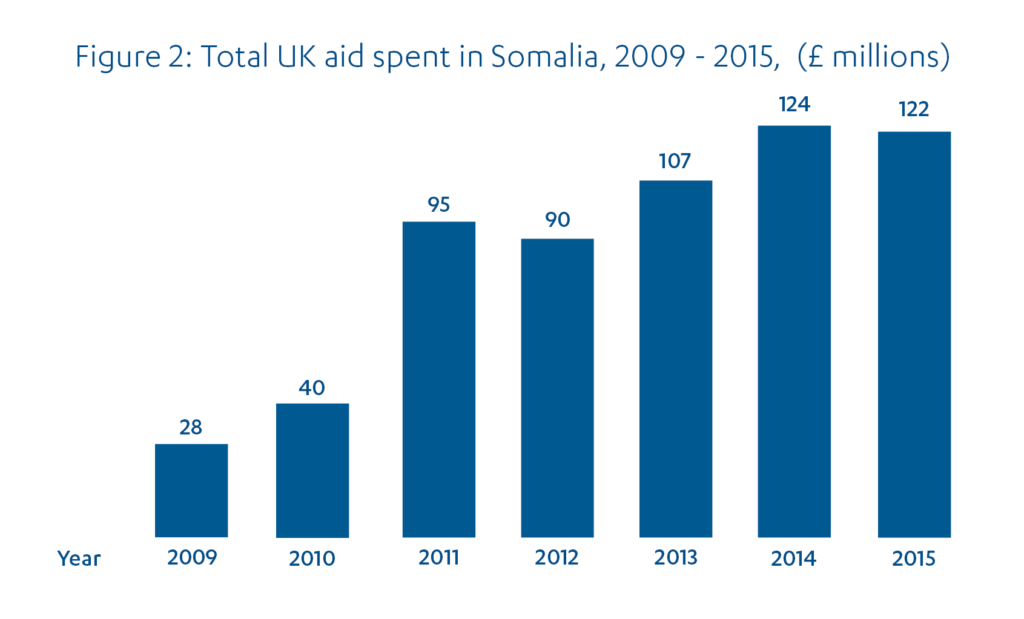

DFID is committed to spending half of its budget in fragile and conflict-affected states and regions.17 The UK aid programme to Somalia has increased from £28 million in 2009 to approximately £122 million in 2015 (see Figure 2).18 DFID spent approximately 90% of UK aid over this period.

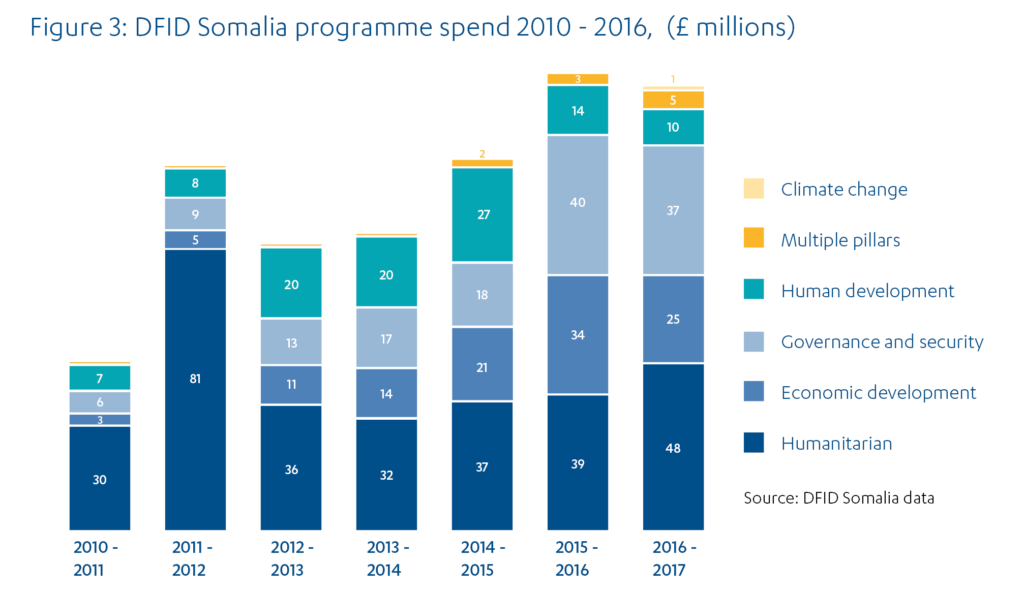

The UK aid budget in Somalia for 2016-17 is estimated to reach £185m, comprising £165 million for DFID19 and approximately £20 million for the CSSF.20 DFID’s expenditure on humanitarian assistance increased from £30 million in 2010-11 to £39 million in 2015-16, with a spike to £81 million in 2011-12 to respond to the last famine. However, the share of humanitarian expenditure in DFID’s programming has declined from 65% in 2010-11 to 30% in 2015-16, as spending on governance and economic development programming was boosted. Those two pillars combined represented 57% of DFID’s expenditure in Somalia in 2015-16, compared to just under 20% in 2010-11 (see Figure 3). In 2017, the UK government announced an additional humanitarian package of £100 million for Somalia to respond to the increasing risk of famine as well as £21 million in additional support for security reform.21

Box 6: Drought in Somalia

This review was designed, and the research and evidence-gathering completed, before the full scale of the drought now gripping Somalia had become apparent. At the time of publication, more than six million people (around half of the population of the country) are thought to be in need of humanitarian assistance. While many countries experienced drought in 2016-17, the four countries which have been most affected by the present emergency are Somalia, South Sudan, Yemen, and the parts of Nigeria where Boko Haram is active. All four also su er from serious conflict and consequent problems of access. In Somalia in particular the ongoing struggles with Al-Shabaab and the associated difficulties accessing many rural areas of the country highlight the need for long term solutions to build peace and stability in order to effectively tackle wider humanitarian challenges.

Findings

This section presents the findings of our review, covering the relevance and coherence of the UK approach to using aid to address con ict and fragility in Somalia, the effectiveness of aid delivery and the quality of associated learning.

Relevance

We begin by exploring the relevance and coherence of the UK’s approach to using aid in pursuit of the peace-building and state-building aims prioritised for Somalia.

The UK aid programme is pursuing the stabilisation of Somalia under a National Security Council (NSC) strategy

Ten years ago, the UK aid programme in Somalia comprised mainly humanitarian assistance and funding for limited UN development interventions in the few accessible parts of the country.22 The approach was to work around conflict and fragility, rather than to address them directly – even though it was apparent that conflict and instability lay at the heart of Somalia’s poverty, underdevelopment and recurrent humanitarian crises.

There is evidence that the Cabinet Office, DFID Somalia and other UK departments were exploring strategies for stabilising Somalia as long ago as 2007. Over the subsequent decade, energised by political concerns about piracy off Somalia’s coast and the need to curb the threat of terrorism, the UK’s approach has evolved into an ambitious, cross-departmental strategy, under the authority of the NSC, to help build a more stable, peaceful and prosperous Somalia. The strategy combines humanitarian and development objectives for Somalia with a concern for UK security interests.

It recognises that conflict, poverty and famine in Somalia have their roots in the lack of a viable political settlement, and need to be addressed at the political level as well as directly.

The NSC country strategy has framed all departmental activity in Somalia since 2014. Its overarching aim is to: “Reduce the threat that Somalia poses to UK national interests by building a more stable, peaceful and prosperous Somalia”.23 This aim is broken down into four objectives (see Table 2). The role of UK aid in Somalia is to deliver the development objectives in a way that complements diplomatic engagement and non-aid interventions and contributes jointly towards a shared results framework. This use of aid to support wider UK government strategy is consistent with the approach set out in the 2015 Strategic Defence and Security Review and the Aid Strategy.24

The NSC strategy for Somalia covers military and intelligence objectives as well as development objectives, and therefore cannot be reproduced in full here. However, we can summarise the main objectives that are supported by the aid programme.

Table 2: Objectives in the NSC country strategy for Somalia supported by the aid programme

| Pillar | Objective | Sub Objective |

|---|---|---|

| Pillar 1 | Reduce the risk to the UK and UK interests | |

| Pillar 2 | Increase security, reduce terrorist territory and resources | |

| Pillar 3 | Increase political stability and predictability |

|

| Pillar 4 | Reduce poverty and improve resilience and economic stability |

|

UK aid programmes are increasingly well integrated under the strategy

Our review of strategy documents and business cases confirmed that, since 2014, all UK government departments working on aid in Somalia have aligned their activities with the NSC strategy and have reported their achievements against its results framework. Although international documents such as the New Deal Compact 2013-16 (see Box 4) have provided important frames for donor coordination and reporting, we found that the NSC strategy provided the overall strategy and results framework for the UK’s interventions.25

Table 3 shows how the UK’s major aid programmes contribute to different pillars of the strategy.The first pillar (related to UK national security) includes approximately £6 million in aid from the CSSF (the CSSF also provides non-ODA funding, for example to build the capacity of security forces to combat terrorism).

The second pillar (on internal and regional security) includes a DFID security and justice programme and a complementary basic policing programme, which together have a budget of around £38 million. Their objective is to re-establish the rule of law in key urban areas recovered from Al-Shabaab and to develop federal and sub-national laws, policies and institutions on justice and security. This substantial investment in the security sector is helping to build one of the core functions of the Somali state.

The bulk of the UK aid programme is integrated under the third and fourth pillars, targeting, respectively, acknowledged gaps in Somalia’s state-building process and key humanitarian and development issues. State institution-building activities include supporting elections, helping the state to raise and manage revenues, facilitating local peace agreements and local governance, and generating alternative livelihoods for disbanded militia. Pillar 4 includes humanitarian aid, which accounts for just under 40% of DFID’s budget in Somalia (prior to the 2017 commitments responding to the increasing risk of famine). There is also programming on economic policy, infrastructure and energy security, livelihood creation, health and nutrition, and empowering women.

Table 3: How aid activities align to the NSC country strategy

| Pillar | Programmes under each pillar of the NSC country strategy26 |

|---|---|

| Pillar 1 |

|

| Pillar 2 |

|

| Pillar 3 | DFID and CSSF programmes to boost electoral processes, state formation and the development of state institutions.

|

| Pillar 4 | DFID’s humanitarian work, plus a range of programming on economic policy, infrastructure and energy security, livelihood creation, health and nutrition, and empowering women.

|

Finally there is work cutting across all the programmes. This includes a strand of CSSF projects on human rights and freedom of expression and support for survivors of sexual violence. The Somalia Monitoring Programme (£10.3 million, 2014-16) is a third party monitoring programme, generating information on local security conditions and governance arrangements and verifying results across a number of DFID’s flagship programmes.

There is no distinction between reducing poverty, tackling global challenges and serving our national interest – all are inextricably linked.

The UK has led a shift in the international approach to state-building in Somalia

Past DFID and Conflict Pool programmes supported constitutional negotiations that led to a 2012 agreement on a provisional constitution. Although never formally adopted, the provisional constitution established the Somali Federal Government as the main counterpart for state-building efforts, even though it controlled little territory outside Mogadishu.

In the period after 2012, the core of the UK strategy was to strengthen the Federal Government and enable it to project its authority across more of the territory. The strategy was closely linked to operations by the regional peacekeeping mission under the African Union. Aid was deployed into areas newly recovered from Al-Shabaab by AMISOM forces in an attempt to stabilise them and bring them into the emerging federal structure. UK resources were also used to help the Federal Government develop a legitimate, civilian-controlled security apparatus, including through the payment of stipends to the police and military (the latter is not from ODA funds). A functioning payroll is important for order and discipline and to sustain a formal command structure. These are needed to clamp down effectively on predatory behaviour by security forces against the local population. The UK also invested in other basic functions of the Federal Government, including its ability to raise and spend revenues.

Over time it become apparent that the Federal Government was unable to establish stable authority over most of the territory recovered through military operations outside Mogadishu. From late 2013, the UK was instrumental in an important evolution in the international strategy. Rather than projecting the notional authority of the Mogadishu-based Federal Government of Somalia directly, it worked increasingly with international and regional interests and the local leadership in newly recovered areas to encourage them to take their place in the constitutional structure as emergent federal entities (see Figure 4).

The UK has a number of aid programmes that have adapted to support this approach. The Somalia Stability Fund is an innovative, flexible, multi-donor instrument designed in 2012 to consolidate and expand areas of local stability through targeted investments.28 It now supports emerging federal entities by facilitating dialogue, investing in local governance structures, supporting community-driven development, promoting community safety initiatives and supporting projects to empower young people. DFID has contributed £34 million to the Fund, while other donors have contributed a total of around £12 million.

The Somalia Stability Fund supports the large Somalia Stability Programme, accounting for nearly £40 million since 2012 and is about to begin a new phase. This complex, multi-component programme has increasingly supported local and regional political objectives through its investments in infrastructure and helping to build new local government administrations.

We have also observed a similar adaptation in UK support for the security sector. The Core State Functions Programme (£52.7 million, 2012-16) focused mainly on building the core institutions and security apparatus of the Federal Government. The new Security and Justice Programme concentrates on building local police and justice services in newly liberated areas and negotiating their relationships with the wider federal structure.

There were evolutions in our approach; we certainly did adapt between 2012 and 2016… Once we had the 2011-12 elections, we did a lot of planning to work with the Federal Government of Somalia, to establish the federal and security structure. But it became clear that we had wonderful plans that proved impossible to implement. The Federal Government and the Police Commissioner were de facto only in control of Mogadishu… We realised that the greatest needs were outside Mogadishu. Following the London Conference, President Sheikh asked for help and the National Security Council took the decision to support other areas.

While this appears to be a realistic and pragmatic response to developing circumstances, it remains difficult to predict the likelihood of success. Its ultimate impact will depend on many factors beyond the UK’s control; meanwhile there are risks in using aid to help local leaders of uncertain motivation and popular support. However, our literature review and most of the experts we consulted indicated support for a loose federal model. We also found a strong consensus among key stakeholders – including representatives of international organisations, other donors and independent experts – that this was a necessary and appropriate adaption in strategy in response to the realities in Somalia. We found that the UK had played a major role within the international community in this evolution (see Box 7). We conclude that the UK’s approach is both credible and feasible.

Box 7: The UK plays a leadership role in the international community in Somalia

- Second-largest donor to Somalia, after the US and ahead of the EU.29

- Key international events to galvanise and shape international action – the London Somalia Conferences in 2012 and 2013 (chaired by the then Prime Minister), the 2015 Security Conference and another London Conference, which took place in May 2017, endorsing a New Partnership for Somalia going forward as well as more funding for drought relief.

- Leadership on Somalia discussions in the UN Security Council.

- Leading role in the main grouping of Somalia donors.

- Co-lead for discussions about the New Deal framework for aid, introduced in 2013.

- Built a new embassy in Mogadishu (2013), making the UK an influential on-the-spot host and coordinator of international discussions.

- Creator of major UK initiatives organised alongside the New Deal coordination mechanisms, such as the Somaliland Development Fund and the Somalia Stability Fund.

Not all UK aid programmes are aligned with objectives on conflict and fragility

DFID programmes which are designed to deliver humanitarian assistance or encourage economic growth (the fourth pillar of the NSC country strategy) can also contribute indirectly to peace and stability, for example by creating jobs and livelihoods, improving public services or providing humanitarian support to vulnerable populations. If poorly designed they may also inadvertently undermine peace and stability, which is recognised in DFID’s so-called ‘do no harm’ policy, which requires an assessment to be made of possible unintended adverse effects which may result from aid interventions.30

We reviewed a selection of such programmes to check how far sensitivity to drivers of conflict was reflected in their design and delivery, and found inconsistencies and gaps in their approach. Only four of the 25 programmes we sampled included an analysis of relevant drivers of conflict at the design stage. Moreover, although most mentioned the promotion of peace and stability in their initial arguments for funding the programme, there were few instances where this was followed through into the programme design or its results framework, and only one instance where there was an attempt to monitor or evaluate impact on conflict (See Box 8).

Box 8: The Sustainable Employment and Economic Development Programme

The Sustainable Employment and Economic Development Programme (£22.6 million, 2010-14) was designed “to contribute to improved stability through economic growth and sustainable employment”. A recent evaluation found that it had made a positive contribution to jobs and livelihoods but not to stability. Its areas of operation and bene ciaries were not selected with stability goals in mind – for example, by targeting young men vulnerable to radicalisation. While some minority groups were included, the programme had not engaged with the local governance structures to address issues around their status. The evaluation even raised the risk that beneficiaries might turn to violent groups for protection of their increased incomes.31

The academic literature we reviewed is clear that economic prosperity is highly relevant to peace and stability, but its impact depends upon questions of equity and whether underlying drivers of conflict are resolved. We saw no evidence of attempts to model these dynamics for Somalia and to relate them strategically to the programmes under Pillar 4. On the face of it this is a missed opportunity for greater synergy across the four pillars of the strategy.

We encountered mixed views across DFID staff in London and the country office as to whether it was appropriate to expect economic development programmes of this type to contribute to peace and stability goals when this is not their primary purpose. The evaluation mentioned above,32 and several interviewees, referred to the possibility of specifically targeting groups at risk of radicalisation. Others stressed the value of supporting political influence or diplomatic engagement. The debate suggests that, overall, DFID does not yet have a settled position on the extent to which development programmes working in situations of conflict and fragility should actively seek opportunities to promote stability and, if so, how. It aims to ensure that all programmes are politically sensitive and do no harm, which is challenging given the complexities of the conflict in Somalia and the widespread corruption. Developing a fully integrated portfolio of programmes that proactively address the many dimensions of conflict and fragility in a mutually reinforcing way would be a very ambitious undertaking. Both approaches would bene t from a more comprehensive, shared analysis of the drivers of conflict at a local and national level.

There are gaps in the UK’s activities on human rights, inclusion and gender equality

We recognise the short-term imperative to secure a political settlement. However, we noticed gaps in implementing the NSC country strategy’s objective to promote the duty of Federal Government authorities to answer under Somalia’s international human rights obligations. Few opportunities to promote such “top-down” accountability were being taken by programmers, despite widespread human rights problems33 and evidence from interviews that the Somali elite were responsive to such external pressures.34

Somalia is a signatory of many international human rights instruments, such as the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights and the Cairo Declaration on Human Rights in Islam. Such formal obligations by themselves may deliver little on the ground but we heard that they can offer a range of potent reference points and levers to help improve people’s lives. We were therefore concerned to find that although the UK is spending £13 million on a project to develop accountability in Somalia, little if any of the budget is going to promote the accountability of the Federal Government itself under the various international human rights treaties. We can see the case for piloting ‘bottom-up’ accountability interventions and we acknowledge that a third of the budget is expected to be spent on strengthening more formal accountability mechanisms within Somalia (such as parliamentary scrutiny). However, it is not clear to us why more has not been done to leverage the international human rights treaties to which Somalia is already bound, for example by effective promotion of the rights themselves and of the power granted to the individual citizen to place violations directly before international bodies.35 We heard that there was no appetite for work on accountability under international law for violations of fundamental human rights.

There was no programming on the objective to foster international [human rights] commitments – because there is no political will. It is very di cult to make accountability work on that basis.

I’ve never seen a real push from the donors. Pushing about the Human Rights Committee, trying to put pressure on the UN Human Rights Commission: it’s not been a priority. That would help the UK among others to have a better understanding of the situation on the ground.

On inclusion, DFID acknowledges that its programmes at this stage include only limited consultation with local communities or support for their inclusion in the state-building process. We were told that there are practical reasons linked to the difficulty of identifying legitimate civil society actors. We understand this reasoning. However, the literature on Somalia suggests much greater inclusion of civil society in peace-building and state-building processes is needed.36 We also noted that a recent independent evaluation of the New Deal has underlined inclusion as a key means of ensuring the quality and sustainability of programming in Somalia.37

We found that DFID had pushed for progress on gender equality, especially through its work supporting a quota of 30% of female parliamentarians during the last electoral process and through its gender programming.38 However, some of DFID’s key governance programmes, including the flagship Somalia Stability Fund and the Implementation and Analysis in Action Accountability Programme (IAAAP), could do more to mainstream gender into their implementation processes.39 The Human Rights and Vulnerable Groups strand of the CSSF has some activities addressing gender issues, but gender mainstreaming was acknowledged as a gap by CSSF senior managers, and this was also apparent in our review of project documents. A gender audit of CSSF’s portfolio in Somalia has now been commissioned, which is a welcome step towards addressing this issue.

There are some tensions between developmental and national security objectives

The NSC country strategy’s primary objective for Somalia is to reduce threats to UK national interests. This is a policy choice so it would not be appropriate for us to comment on that, other than to note that this can only be a secondary objective of aid programmes that meet the OECD DAC definition of ODA and that fall under the spending authority of the UK’s International Development Act. Separately, a very senior UN official and two of the seven donors we spoke to commented that the priority given by the UK to its own national and security interests could potentially create tensions with Somali national ownership – a key principle of good aid practice.

We also saw evidence of tensions within UK aid programmes. We found at least two examples in Somaliland where longer-term institutional development seemed to be losing out to shorter-term operational security objectives. We heard, for example, that leverage from substantial aid investment in new police headquarters was being used to secure cooperation on particular security issues, rather than for political leverage to unblock progress on crucial new police reform legislation. We have concerns about how such tensions are resolved on the ground and how they are handled by the interdepartmental coordinating machinery.

There is an associated risk that the priority given to national security issues might lead to pressure to use ODA funding for activities that fall outside its legally de ned purposes. We found no evidence of this in our sample, but we came across instances in Somaliland where it was difficult to draw a clear line between capacity building of national security agencies, which is ODA-eligible, and security-related operational activities, which are not.

We found some differences in views on the drivers of of conflict

Since 2011, UK government guidance on tackling conflict and fragility overseas has emphasised the importance of a shared and systematic understanding of conflict,40 to ensure coherence across the various departments and to help avoid unintended consequences. The main instrument developed for this purpose is the Joint Analysis of Conflict and Stability (JACS). Ensuring a JACS has been conducted across fragile and conflict-affected states has been one of the results indicators for DFID’s Conflict, Humanitarian and Security department (CHASE).41

No JACS has been developed for Somalia. We were offered several reasons for this by senior DFID and FCO staff, who suggested that it was unnecessary as the departments already shared a common understanding of the issues, and because the NSC country strategy ensured sufficient coherence. We also heard that the resources involved in compiling a JACS and the transactional costs in agreeing one were considerable.

We nonetheless found that UK stakeholders could have bene ted from a more comprehensive and systematic shared understanding of the drivers of conflict in Somalia.42 While there was agreement on many key points, we noted some important differences of opinion, with implications for UK strategy, for example on the politicisation of clan identity, political exclusion and fear of the state, hostility towards Ethiopian and Kenyan soldiers, and the role of religious ideology in driving conflict.

We found consensus among academic and other commentators that Somalia’s problems should be seen as a series of fluid and overlapping conflicts produced by multiple drivers at national and local levels. Experts caution against conceptualising Somalia’s conflict solely as a struggle for control between the government and Al-Shabaab.43 Yet elements of such thinking are found in high-level UK documents and appeared to have influenced a number of activities, including CSSF support for projects in Pillar 1 of the NSC country strategy.44 Only four out of the 25 UK aid programme documents we reviewed attempted to analyse the drivers of conflict relevant to the proposed intervention, raising the question of whether programmes are as well targeted as they could be.

UK aid has improved its ability to adapt to local conditions

Somalia represents an extremely complex and dynamic operating environment. In this section, we consider the ability of the aid programmes to adapt to local contexts.

Based on our interviews with programme managers and our review of programme documents, we saw evidence that, over the period under review, the UK has improved its ability to assess local conditions. Contextual analysis is included in most programme or project documents. The CSSF, in particular, has increased its focus on analysis. The four large DFID governance programmes all also included some elements of a local conflict analysis, or required partners to conduct one. The Somalia Monitoring Programme provides a source of local analysis, as does the UN Monitoring Group.

We found differences in the quality of contextual analysis and its timeliness across the portfolio. In our sample of 25 programmes, only the principal DFID governance programmes clearly identified local drivers of conflict. We also encountered some conflicting ideas on how to operationalise the ‘do no harm’ principle in relation to CSSF activities.

From CSSF’s perspectives, there is a real institutionalisation of ‘do no harm’ and conflict sensitivity in the programmes.

The ‘do no harm’ principle is not on the CSSF agenda, although we do consider conflict sensitivity.

Conclusion on relevance

Overall, we have given the UK aid programme in Somalia a green-amber rating for relevance. Aid is deployed actively in support of a strategy for stabilising conflict-affected areas and bringing them into the emerging federal structure. Programmes are aligned behind the NSC country strategy, and are clear about which high-level objectives they contribute to. The UK approach has adapted over time, in response to experience and changing conditions, and the UK has played a strong leadership role within the international community, attracting support from other donors and international organisations. The World Bank’s evidence suggests that stabilising a country like Somalia takes at least a generation.46 It is too early to offer a firm conclusion about the prospects of success for the UK’s strategy. Nevertheless we find that the strategy is credible and feasible.

While the aid programme has got better at analysing and adapting to local conditions, we were concerned at the lack of a shared conflict analysis across the responsible departments. One of the inferences is that programmes may not be active enough in managing the risks of inadvertent harm.

Beyond the governance and security areas, we find that DFID’s development and humanitarian programmes are not fully oriented towards peace and stability objectives. While this may not be possible or appropriate in all cases (for example famine relief), more should be done to analyse and take account of social or economic drivers of conflict for all interventions so as to minimise the risk of inadvertent harm. We also found a few important gaps in the focus on cross-cutting issues like human rights, gender equality and, potentially most significantly, political inclusion.

Effectiveness

This section considers how effective UK aid has been in tackling conflict and fragility in Somalia and how far it has achieved value for money. Our assessment takes into account the extremely challenging operational environment in which UK aid is delivered.47 We review the UK’s ability to deliver aid and achieve outputs in this environment and assess the consequences of its decision to shift the delivery of part of its aid to the private sector. We then assess the UK’s ability to measure outcomes and examine existing evidence of its contribution to high-level positive political changes that have occurred in Somalia over the past five years.

The UK has significantly improved its ability to deliver aid inside Somalia

Five years ago, the UK had very little capacity to deliver aid programmes within Somalia, due to the highly restrictive security environment. It had little choice but to deliver its assistance through multilateral partners.

In 2011, I and a colleague were the first DFID officials to visit Mogadishu in 20 years. This reinforced how little we knew.

The risks were high. You get it wrong, you create more conflict, your resources get captured, your staff get captured. We could not visit anywhere.

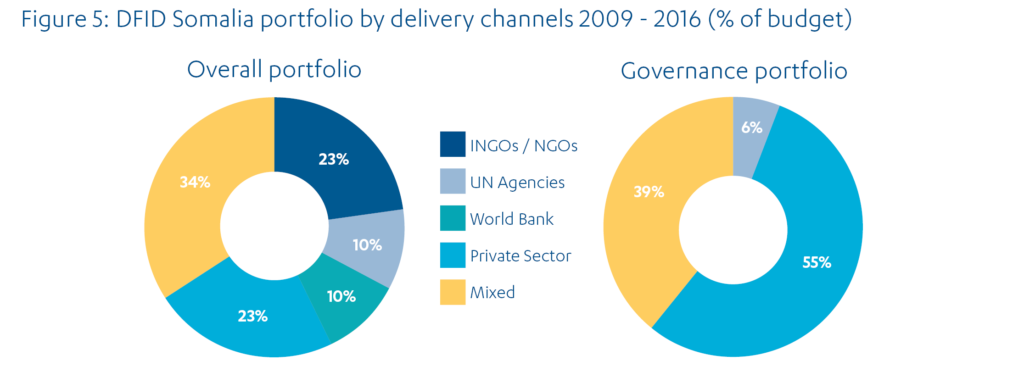

Since then, DFID has made a significant investment in building up an independent delivery capacity in Somalia. It has developed a network of international and local private sector suppliers able to operate across most of the territory. Private sector providers now implement about a third of DFID’s programming by value (Figure 5).48

This shift in delivery mechanism has enabled DFID to target its programming more rapidly so as to support peace-building initiatives – including by directing aid into newly liberated areas. This has enabled the UK to respond quickly and with flexibility to opportunities to support local political dynamics that have led to the emergence of federal structures. Most of the stakeholders we interviewed, including Somali officials and UN partners, confirmed that this shift had led to more effective delivery, especially in terms of reach and access.49 It is telling that some of DFID’s contractor- delivered programmes have been able to attract funding from other bilateral donors.

The use of private contractors also gives the UK greater capacity to build NSC objectives into the aid portfolio. Some of DFID’s most sensitive interventions – such as the Somalia Stability Fund, the Somaliland Development Fund and the Reconciliation Programme – are managed by private rms. They are directly accountable to the UK government and responsive to its precise objectives, including those with a bearing on the UK’s own security interests. By contrast, UN agencies are formally accountable to the host government, and answerable to a range of donors. They are obliged to work within the general strategic framework for the UK contribution which is de ned by the international community. This strategic framework was the New Deal Compact for much of the period covered by this report.

We found that there were also some risks associated with the use of private contractors, which the UK departments involved could be managing more actively. Contractors need direct support from UK officials or UN political actors to equip them to engage with Somali political leaders. We saw a positive example where the Somalia Stability Fund had addressed this issue by including a DFID secondee in the programme secretariat, to ensure close collaboration, but we also saw programmes where this support was not forthcoming.

We also heard from contractors and from Somali officials that in most instances private actors are not operating under an official memorandum of understanding. This misses an important opportunity to define the wider operating framework, lines of political accountability and requirements to coordinate with national and international partners.

The UK has increased its capacity to monitor aid in Somalia

DFID has also taken steps to increase its effectiveness by investing at least £14 million over the past four years in remote monitoring capacity through third party suppliers. Its Somalia Monitoring Programme (£10.3million, 2014-16) provides monitoring support across seven flagship programmes, conducting site visits to verify that work has been done and to collect beneficiary feedback. In addition, a significant component of the 2013-17 Multi-Year Humanitarian Programme is dedicated to third party monitoring. DFID and its contractors have developed sophisticated monitoring techniques, including satellite verification, call centres to collect beneficiary feedback and online data platforms. Although there is scope for further improvements, they provide DFID with assurance that its aid is reaching the intended beneficiaries, even in places where government staff are unable to visit. We also identified several instances where DFID was able to intervene and resolve delivery problems identified by its independent monitors. The CSSF has built on DFID’s model and contracted independent partners to monitor its own portfolio of activities in Somalia. We note that this approach to third party monitoring is considered to be an important innovation for UK aid operating in fragile and conflict-affected states, and this was spearheaded by DFID Somalia.

The UK is also starting to use this apparatus to assess the results of its programming beyond the output level. DFID has for example contracted an expert agency to collect qualitative data to assess the effects of a sensitive security and justice programme, the Basic Policing Programme, and to monitor the level of acceptance that new police forces are able to generate in the communities. We reviewed the quarterly reports produced by the agency and were satis ed that they provided a deeper level of analysis of the programme than simple verifications and were relevant for DFID’s decision making. Given the difficulty of obtaining reliable data in Somalia and the high risks of diversion, we understand why the third party monitoring focuses first on verifications, but we were disappointed not to see more of this across the governance portfolio, especially on programmes like the Somalia Stability Fund (see below).

We also noted that in areas where access is easier, DFID generated some outcome data. For example, the Somaliland Development Fund, DFID’s flagship programme in the north, conducted a large perception survey to help measure outcomes. According to a recent internal review,50 DFID programme managers could make even more use of this investment in monitoring, for example to collect data at outcome level, on value for money and to support learning on effectiveness.

We recognise that generating more sophisticated outcome data through larger-scale surveys or in-depth qualitative interviews is still very challenging and expensive in Somalia and that DFID had justification to orient its third party monitoring apparatus towards verifications first given the high fiduciary risks for its operations. Our interviews also suggested that DFID managers could make more use of the technical assistance made available to them under the programme to improve delivery standards down the supply chain. This reinforces a finding from our 2016 review of DFID’s management of fiduciary risk,51 which found that DFID lacked sufficient visibility of its overall portfolio and of risk arising further down the delivery chain.

Cross-departmental coordination has improved

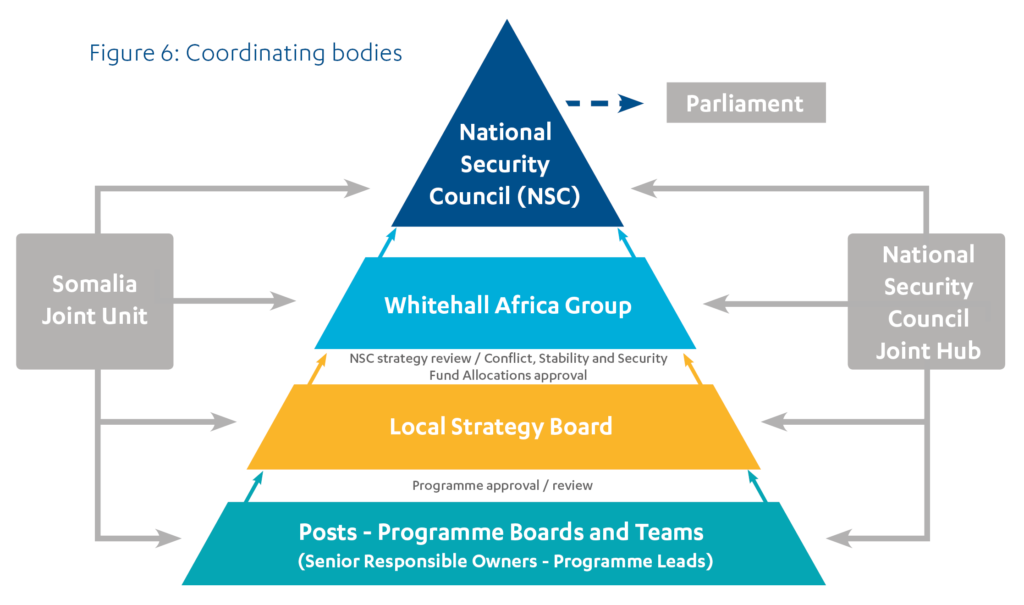

We found good levels of cooperation between DFID, the FCO and other UK government departments, especially at the operational level. UK departments and external stakeholders noted significant improvement compared with the situation prior to the advent of the NSC country strategy in 2014. We came across a small number of instances of poorly coordinated work,52 but the coordinating structures – the Local Strategy Board, the Whitehall Africa Group and the Joint Somalia Hub – have helped to build more of a ‘One HMG’ approach (see Figure 6).

There are a lot fewer frictions between government departments than there used to be: the National Security Council and the CSSF structures played a role in improving this.

Coordination is the one thing that is the marked step change since the inception of the CSSF. The cross-Whitehall coordination is just so different. Coordination of programming is much better: everyone is aware of what’s going on.

The architecture and ways of working much more genuinely correspond to the idea that all our work aggregates under the National Security Council Strategy.

To explore the quality of coordination, we looked at three instances of how it had operated in response to specific issues or challenges (see Box 9). We saw one case where the Strategy Board engaged extensively on a sensitive issue of particular concern to DFID. In the other cases we would have expected the coordinating committees to have played a more active or strategic role in addressing the issues.

Box 9: Cross-department coordinating structures at work

-

-

- The coordinating machinery engaged at all levels, and frequently with a difficult policy challenge around an initiative to provide transitional livelihood support to low-level former Al-Shabaab supporters. This raised concerns about operational and reputational risks which were the subject of anxious consideration within and between departments. We found, from records of the discussions and interviews with DFID and FCO managers, that the Local Strategy Board addressed the various concerns raised mainly by DFID about the value and risks of the programme, agreed modi cations and safeguards, and monitored progress, reporting to the higher-level committees as appropriate.

- On security and justice in Somaliland, overlap, incoherence and poor coordination had been identified by the Stabilisation Unit and other observers.53 Only one of the committees (the high-level Whitehall Africa Group) discussed the issues – and endorsed a mistaken assurance that the problems had been solved.

- Nor did the coordinating machinery help to build a cross-departmental approach to paying police (which is ODA-funded) and soldiers (which is not). The NSC had decided in 2011 to fund both forces. However, the FCO and DFID used di erent payment modalities: one cash-based (and considered by UK expert advisors to be more open to abuse) and one electronic. While the Whitehall Africa Group devoted much attention to the issue of pay to soldiers and police, its focus was on the risk of underspend. There was no coordination on the choice and quality of safeguards, or sharing of lessons between the two initiatives.

-

Interviews with DFID and FCO managers supported our observations that the Local Strategy Board has scope to occupy a more strategic coordinating role.

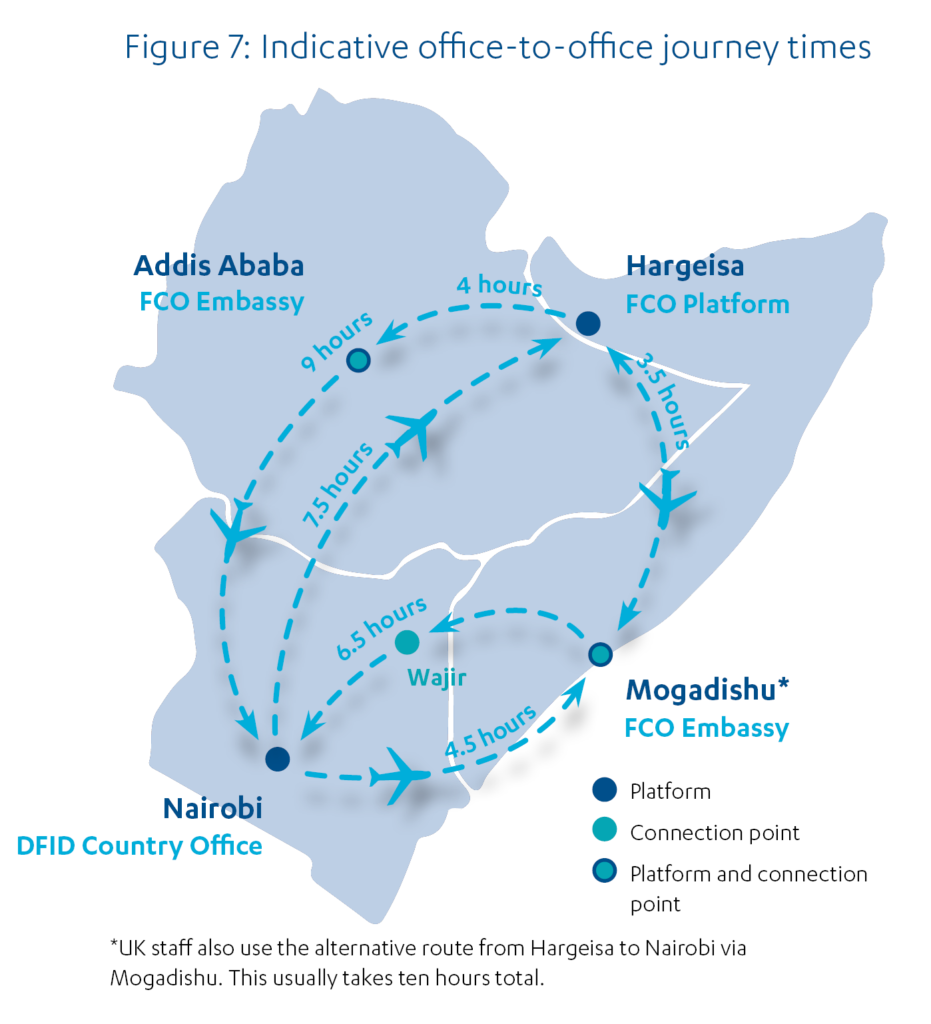

One of the challenges to ‘One HMG’ working in Somalia is that staff from different departments work from four separate locations, with differing communication, accounting and management systems. Figure 7 shows the typical journey times required to travel between the four different locations. Together, these factors constitute a lack of shared working space which is relevant to effectiveness and efficiency, as well as costs.

Box 10: Examples of the lack of shared ‘One HMG’ working space

- IT issues mean that FCO staff cannot access data from another FCO platform (eg project documents).

- DFID Somalia does not have full visibility of the costs of the Hargeisa platform run by the FCO, limiting its ability to assess value for money adequately.

- Occupancy data from the Hargeisa platform shows that DFID staff seem to visit projects much less frequently than FCO staff.

- The maximum time for FCO staff rotation in Mogadishu is 12 months. For Ministry of Defense staff it is two years. For DFID staff it can be up to three years in Nairobi. Therefore staff relationships are constantly changing.

We discussed these issues with DFID and FCO management. Cross-departmental collaboration has certainly improved following the advent of the NSC country strategy but we did not feel con dent that the four separate operating platforms and the different departmental arrangements were conducive to best value and optimal collaboration. We heard that a recent review had endorsed the current arrangements for managing aid to the Somaliland operations from Addis Ababa and Nairobi; however it did not consider all four locations. There is a case for a more radical review, focusing on cost drivers and value for money as well as the consequences of the dislocations we referred to in Box 10.

UK programmes perform well at output level, but there is limited data at this stage on achievement of outcomes

DFID’s programmes show a good track record of delivering their planned activities and outputs. DFID Somalia reports that its Portfolio Quality Score has increased from 92 in 2014 to 108.5 currently. (This score sums up how well DFID projects, weighted by budget, deliver against their expectations; a score of 100 would indicate that the programmes were, on average, delivering exactly as planned.) This puts it at the top end of DFID’s Africa Division.54 Because this scoring might also be explained by less than ambitious targets, we checked to see whether milestones were downgraded over the life of programmes. We found only two instances where this had occurred. We also saw two other cases where milestones were upgraded due to better-than-expected performance. While this is only output data, not impact, it is evidence of a portfolio that is delivering well in a very difficult environment. Interviews with stakeholders supported that conclusion (see Box 11).

Across the 25 programmes we reviewed, we have evidence that at least 18 have achieved or are likely to achieve their outputs. It is uncertain for four of them, and three programmes appear unlikely to achieve all their outputs.

Box 11: Glossary of results terminology

- Outputs: The immediate results of an intervention. Implementers are directly accountable for their delivery of outputs.

- Outcomes: The benefits that an intervention is designed to deliver. Outcomes are not within the direct control of the implementer, but if the intervention is well designed, the outputs should lead logically to the outcomes.

- Impact: The higher-level strategic goals to which the intervention is intended to contribute.

- Theory of change: A set of assumptions or hypotheses as to how a development intervention will lead to the intended outcomes and impacts. Impact is often heavily influenced by the actions (or inaction) of others.

There is a mixed picture on achievement at outcome level. Several of DFID’s governance and security programmes are complex initiatives, with many component activities at different stages of implementation. Because of this complexity, we found that outcome indicators in programme logframes did not always provide an accurate picture of emerging results. Furthermore, many programmes are yet to generate outcome data. Box 12 summarises the results data available from DFID’s four flagship governance and security programmes. It is difficult to draw firm and clear conclusions about the contribution the programmes are making to conflict- and fragility-related outcomes based on this data. Nevertheless, our review of sampled programmes suggested that in 17 of the 25 programmes reviewed the links were plausible. This indicates that those outputs would contribute to the desired outcome.

Box 12: Summary of results from DFID’s major governance and security programmes

Re-establishing Basic Policing Programme (£8 million, 2014-17) seeks to re-establish basic policing in selected areas recovered from Al-Shabaab.

- Outputs: By the time of the 2016 Annual Review, it had trained 800 police officers in Kismayo and Baidoa, established a reliable electronic payment system to pay their stipends and helped broker an agreement regarding their accountability to the Federal Government. The programme reports that output targets have been achieved or exceeded.

- Outcomes: The expected outcome is the re-establishment of basic policing in selected areas, measured by public awareness of police presence and levels of public trust in the police. The programme is yet to claim any results at outcome level, amid mixed evidence from surveys on awareness and trust. It has adequate monitoring systems in place to monitor outcomes as the programme progresses.

- Our assessment: It is too early to assess whether the programme will achieve its outcomes, but it has the potential to make an important contribution to restoring security in the target areas.

Accountability Programme (£23 million, 2012-19) aims to create more representative and accountable Somali administrations.

- Outputs: The 2016 Annual Review notes that outputs have been delivered generally as expected. They include the belated completion of voter registration in Somaliland, a body of research on accountability and the establishment of a payroll system for the security sector.

- Outcomes: The Annual Review states that the programme’s outcome (increase in transparent evidence-based interventions supporting Somali administrations that are representative and accountable) is “broadly on track” to be achieved with all three indicators on target. We note that the outcome indicators are not particularly ambitious, resembling outputs.

- Our assessment: The programme has the potential to make a contribution to stabilising Somali institutions, but it has struggled to establish a coherent overall framing for a range of disparate interventions. The majority of the programme addressed ‘bottom-up’ aspects of accountability and involved nancing the activities of local groups. It wasn’t clear how these interventions added up to genuine outcomes. Work on ‘top-down’ accountability had a lower priority in terms of spend and missed opportunities to leverage Somalia’s accountabilities under the various international human rights treaties.

Core State Functions Programme (£52.7 million, 2012-16) works with a large number of local, district and central institutions to build their capacity to deliver core functions and respond to citizens’ priorities.

- Outputs: Mixed achievement against targets. Good results from longer-term interventions, including promoting access to justice, mobile courts and legal aid.

- Outcomes: Outcome indicators are poorly de ned, and little performance data is available.