UK aid for energy transition

Acronyms

| Acronyms | |

|---|---|

| BII | British International Investment |

| CCMM | Climate Investment Funds Capital Markets Mechanism |

| CETP | Clean Energy Transition Partnership |

| CIF | Climate Investment Funds |

| COP | Conference of the Parties |

| CPI | Climate Policy Initiative |

| CSP | Concentrated Solar Power |

| CTF | Clean Technology Fund |

| Defra | Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs |

| DESNZ | Department for Energy Security and Net Zero |

| DFI | Development Finance Institution |

| DSIT | Department for Science, Innovation and Technology |

| FCDO | Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office |

| GCF | Green Climate Fund |

| GCPA | Global Clean Power Alliance |

| GW | Gigawatt |

| ICAI | Independent Commission for Aid Impact |

| ICF | International Climate Finance |

| IPG | International Partners Group |

| JETP | Just Energy Transition Partnership |

| KPI | Key Performance Indicator |

| MCF | Multilateral Climate Fund |

| MDB | Multilateral Development Bank |

| MEL | Monitoring, Evaluation and Learning |

| NDC | Nationally Determined Contribution |

| ODA | Official Development Assistance |

| OECD | Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development |

| PIDG | Private Infrastructure Development Group |

| SDG | Sustainable Development Goal |

| UNFCCC | United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change |

Executive summary

A shift of the world’s energy systems away from polluting and carbon-emitting fossil fuels and towards clean, affordable and renewable energy is essential to support economic growth and poverty reduction while keeping global warming below dangerous levels.

Domestically, the UK has already committed to this energy transition, cutting emissions by half compared to 1990 levels and pledging to reach net zero emissions by 2050. Internationally, recognising the global nature of the climate challenge, successive governments have also allocated a significant share of the UK’s aid budget to supporting developing countries to make the transition to low-carbon, climate-resilient and nature-positive development paths.

This Independent Commission for Aid Impact (ICAI) review assesses how well the UK’s support for energy transition in developing countries has worked over the past five years, focusing on relevant spending and activities from 2021-22 through to 2025-26 within the UK’s overall £11.6 billion international climate finance (ICF) pledge.

The review considers the relevance and effectiveness of the UK’s strategic approach to energy transition in developing countries; how well the UK has worked with international alliances and country partnerships, in particular the Just Energy Transition Partnerships (JETPs); and how effective the UK’s efforts have been at mobilising further public and private finance in support of energy transition.

The review scope is global, including the UK’s bilateral programmes and funding through British

International Investment (BII) and the Private Infrastructure Development Group (PIDG), as well as UK ICF funding for multilateral development banks (MDBs) and multilateral climate funds (MCFs), in particular the Climate Investment Funds (CIF) and the Green Climate Fund (GCF).

Energy transition is a multi-sector and system-focused endeavour that spans all the four priority pillars of the 2023 strategy governing the UK’s ICF spend (clean energy; sustainable cities, infrastructure and transport; adaptation and resilience; and nature for climate and people). The exercise to determine the UK’s portfolio of energy transition-relevant programming for ICAI to build its review around took place in two steps. Initially, the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO) and the Department for Energy Security and Net Zero (DESNZ) shared the outcome of a recent mapping exercise they had conducted across energy transition-relevant programming. Building on this, we conducted an additional exercise in collaboration with the departments to identify the set of programmes and activities that were relevant to energy transition within our review period. In total, we identified 84 energy transition-relevant programmes and activities as constituting the UK’s energy transition portfolio. The findings in this review are centred around this portfolio.

Some of the programmes and activities in this portfolio have clean energy as their primary focus, some do not have an energy focus but are relevant to the wider energy transition, while others include clean energy alongside other ICF pillar priorities. Based on an analysis and estimates of this ICF pillar breakdown, as well as the delivery channels of the support, our best estimate is that the UK will spend around £3.6 billion of official development assistance (ODA) on supporting energy transition in developing countries over the five years 2021-22 to 2025-26 (within a total budget for the 84 relevant programmes and activities of £5.7 billion, and a total for ICF of £11.6 billion).

Findings

Relevance and effectiveness of the UK’s strategy

The review finds that the UK’s energy transition efforts in developing countries are highly relevant to addressing the climate crisis and benefit from long-standing and constant political commitment, substantial financial contributions, and strong technical expertise. Together these lie at the base of the UK’s leading role in international efforts to promote global energy transition.

The UK’s approach has largely evolved through a learn-by-doing, adaptive model shaped by a combination of international climate negotiations and reactive programme-level decisions. The result is a broad and diverse energy transition portfolio, which at its best allows adaptive decision-making, but also risks a lack of coherence. There is no single, shared definition of energy transition, nor a comprehensive operational strategy for achieving all of the UK’s energy transition objectives, and government departments do not have a clear framework for cross-departmental decision making. This makes identifying gaps, and strategic decision making on prioritisation and scaling up, difficult – an urgent challenge as the UK government reduces its ODA budget from 0.5% to 0.3% of gross national income over the next two years to 2027.

Programmes in the energy transition portfolio are reporting significant results in some areas, but accountability for ICF reporting is weak and reporting practice is not comprehensive. The UK’s ICF monitoring and learning system is recognised as stronger and more transparent than those of other donors, but the ICF key performance indicators (KPIs) only provide a partial results picture for the energy transition portfolio. It is also not possible to determine how many programmes should be reporting on a given ICF KPI, hampering accountability and strategic learning across the energy transition portfolio. The available data does not allow a complete and accurate breakdown of the UK’s spend on energy transition by KPIs, delivery channel, or country.

The UK vision is to enable systemic shifts to accelerate progress to deliver transformational change in the energy systems of developing countries. Some early progress has been made, but there is a lack of clarity on how the efforts across the UK’s broad range of programmes work together to achieve transformational change. There is a delicate balance to be managed between the energy transition portfolio’s strategic focus on higher-emitting, middle-income countries, albeit with sizeable poor populations, and the need to ensure adequate support for low-income countries that remain relatively underserved, despite their acute vulnerability and greater dependence on concessional finance, with potential implications for the UK’s longer-term poverty reduction and equity goals. The UK is a major contributor to MCFs and has used its role as the leading donor to influence the strategic direction of the CIF and the GCF in a positive direction. These climate funds are central to the UK’s energy transition objectives, but there has not been a clear strategic rationale underpinning the UK’s allocation decisions between multilateral and bilateral funding channels or on the proportion of funding allocated to each fund.

The review finds positive examples of cross-government coordination on the UK’s international energy transition portfolio, but a lack of high-level coordination structures risks undermining portfolio coherence and strategic delivery. In September 2025 the government announced an overhaul of the way its cross-government ODA board works to address this risk.

Finally, we noted the importance for energy transition of securing a stable and ethical supply of critical minerals and the persistent challenges posed by complex and opaque extraction and supply chains, despite UK and international commitment to strong environmental and social safeguards.

Working with partners and alliances

The UK played a central role in establishing JETPs, notably in Indonesia and South Africa, which are country-led agreements that aim to mobilise grants, concessional loans, guarantees and private finance to help middle-income countries shift from coal to clean energy.

The UK’s support for JETPs is valued by other donors and partner countries due to its responsive nature and focus on capacity support and consultation. While the JETPs have fostered financial commitments from national governments, donors and private financiers, the mobilisation of funds has been slower than intended, with actual project spend lagging behind expectations. Progress on the phase-down of coal-fired power capacity is also off track, and UK offers of guarantees on loans from MDBs – the primary means of UK financial support offered – have not yet been fully taken up.

While the UK’s influence on the outcomes of a country-led partnership is limited, some of the problems could have been anticipated in the original design and goals. However, the UK has used the lessons learned from the JETPs to inform its approach to subsequent country-led initiatives.

The UK has also been central to the creation of several different international alliances bringing developed and developing countries together to promote energy transition in the last five years. These range from the Clean Energy Transition Partnership launched at the Glasgow Climate Summit in 2021 to the Global Clean Power Alliance launched at the G20 in 2024. While the alliances themselves are not aid-funded, developing country members of alliances will often rely on aid funding to be able to commit to the alliances’ objectives.

Although there are some good examples of success, it is not possible to assess the effectiveness of these alliances robustly, since rigorous monitoring, evaluation and learning standards are only applied to direct use of aid money and not to the UK’s influence and wider impact of the alliance. The proliferation of alliances in the same space poses risks of fragmentation and duplication, especially for developing countries with limited capacity.

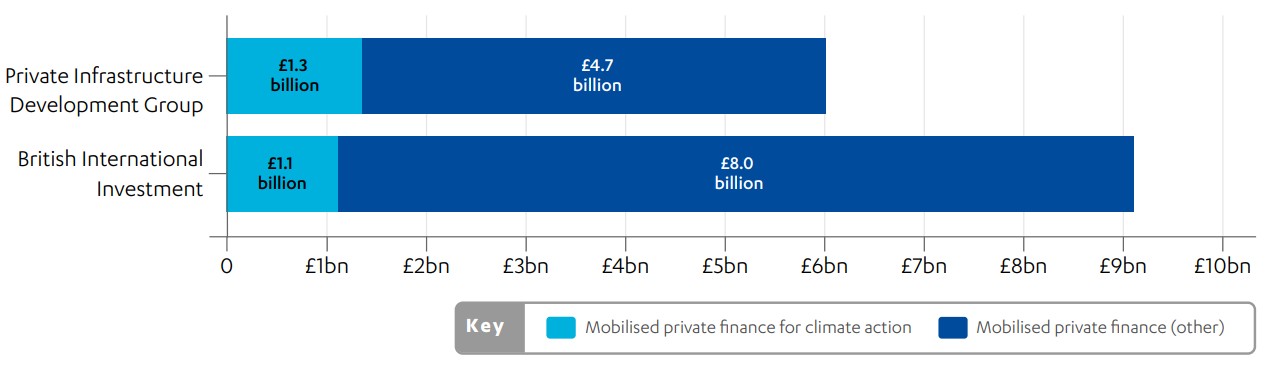

Mobilising finance

A central UK objective is to use its ICF to leverage and mobilise further public and private finance in support of energy transition. While global climate finance remains far below required levels, the review found evidence of UK leadership in supporting effective finance mobilisation. Looking at the results reported against the ICF KPIs on the mobilisation of public and private finance, the energy transition portfolio reported £5.2 billion of mobilised finance in the period from 2021-22 to 2023-24 (the last financial year for which we have KPI data). The UK-supported MCFs and development finance institutions all report significant mobilisation of public and private finance. However, their performance cannot be easily compared: they have different mandates, some operate in areas where attracting climate finance is easier, and they use different ways of measuring finance mobilisation, which may ultimately also affect the quality of the data fed into the ICF KPI data on mobilisation.

There is potential for the MCFs to increase their already considerable mobilisation of private capital, and the UK has been working with the funds to emphasise and operationalise this priority. There is evidence that in the past year the government has begun to engage with City of London institutions more intensively.

The UK takes a system-wide approach to finance mobilisation at all stages of the investment cycle, including for higher-risk innovations and for promoting an enabling investment environment in developing countries. This is a robust approach, but it is constrained in practice by the limited coherence between the many small and diverse activities and programmes that make up the energy transition portfolio, and insufficient coordination with other funders and between FCDO and DESNZ. The need for strengthened cross-departmental coherence on climate-related spending is recognised by the government, and there are intentions to strengthen the working of the cross-departmental ODA board, where all ODA-spending departments have a seat.

There is a risk of concessional funding crowding out private finance, linked to the UK’s focus on middle-income countries and emerging markets. Many middle-income countries, unlike low-income countries, have the capacity to access climate finance through non-ODA mechanisms and market-based instruments. The sample of business cases we reviewed in the UK’s energy transition portfolio all addressed the risk of crowding out private finance, but did so with the aim of justifying the proposed investment rather than providing a rigorous assessment of whether the programme’s goals could be secured without, or with less, concessional finance. Nevertheless, a few evaluations concluded that UK support had not crowded out private investors.

Conclusions and recommendations

Overall, there are many positive achievements to highlight in the UK’s ICF work on energy transition in developing countries. However, with difficult choices on the allocation of resources ahead, there is scope for improvement. This includes forming an overarching energy transition definition and strategy, addressing accountability and implementation gaps in data and reporting, and strengthening coordination across programmes and financial mobilisation efforts across the investment cycle, with sensitivity to the country context. While the UK’s influential role and adaptive decision making are clear strengths, further progress is needed on strategic direction, coherence, and transparency to fully maximise effectiveness and impact.

Work on energy transition through partnerships and alliances has the potential to empower developing countries to take the lead on this work. But in the absence of systems to evaluate the impact of some of these initiatives, there is no evidence that they are an effective replacement for more conventional bilateral aid programming or investments through multilateral funds and development banks.

With the aim of supporting the UK government in further strengthening its efforts on energy transition in developing countries, ICAI offers the following recommendations.

Recommendation 1: The UK should publish a comprehensive energy transition strategy with a clear definition and theory of change, which also reflects poverty reduction and inclusion goals

Recommendation 2: The UK should take a portfolio-level approach to identifying and allocating funding between different bilateral and multilateral channels, notably between the multilateral climate funds, based on comparative advantage and value for money

Recommendation 3: The UK should establish clear, publicly accountable departmental roles with joint accountability to strengthen decision making and coordination on energy transition

Recommendation 4: The UK should standardise and strengthen the implementation of monitoring and learning across its energy transition portfolio, particularly accountability for reporting and the use of data on transformational change, financial leverage, and the additionality of UK finance

Recommendation 5: The UK should clarify the role of its country partnerships and international alliances in supporting energy transition, introduce more realistic targets for the JETPs, and create robust performance frameworks for alliances

Recommendation 6: The UK should clearly articulate its objectives for mobilising additional finance, distinguishing between support for countries at different development stages and across the investment cycle

1. Introduction

1.1 Global energy transition from fossil fuels to renewable energy is key to reducing the rate of global warming and helping countries and communities become resilient to the impacts of climate change. It is at the centre of the global climate goals set out in the Paris Agreement of 2015 and subsequent accords (see Box 1). Despite record investments and strong policy support, the climate goals are off track, making energy transition more urgent than ever.1 The latest overview of the scientific evidence by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change found that climate change is already affecting weather and climate extremes in every region of the world, including heatwaves, droughts, heavy precipitation, floods, and cyclones. Adverse impacts are already felt on food and water security, human health, and economies, with vulnerable communities disproportionately affected.2

Box 1: The Paris Agreement and the global climate goals

The United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) is the main vehicle for driving global cooperation to reduce climate change and its negative impacts. The UNFCCC convenes an annual Conference of the Parties (COP) where states review the scientific evidence on climate change, assess progress against global goals and national targets, and negotiate further agreements. In 2015, at COP21 in Paris, almost all the world’s states adopted the Paris Agreement, committing to “strengthen the global response to the threat of climate change, in the context of sustainable development and efforts to eradicate poverty”. The Paris Agreement has three linked commitments:

- To keep the average global warming to well below 2 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels and as close to 1.5 degrees as possible.

- To increase the world’s ability to adapt to the adverse impacts of climate change and foster resilience. This includes “low greenhouse gas emissions development” – economic development that builds on low-emitting technologies (away from fossil fuels).

- To ensure there are sufficient finance flows (known as “climate finance”), both public and private, to enable countries to pursue the first two commitments.

Developing countries will be the worst affected by climate change. They have historically contributed less to the emissions causing global warming, although fast-growing emerging economies are now some of the largest emitters.3 The Paris Agreement establishes the principle of “common but differentiated responsibilities and respective capabilities”, with climate finance to support developing countries’ transition to low-emission and climate-resilient development.

In 2023, at COP28 in Dubai, the first global stocktake of the Paris Agreement was held. It found that important progress had been made, but the world was nevertheless on a dangerous path to a temperature increase of 2.5-2.9 degrees Celsius. In the United Arab Emirates Consensus, agreed at COP28, countries committed to:

- transition away from fossil fuels in energy systems – also known as ‘energy transition’ – in a just, orderly and equitable manner

- triple the global renewable energy capacity and double the rate of energy efficiency improvements by 2030

- strengthen adaptation and resilience, including national adaptation plans and support for vulnerable communities

- scale up climate finance, especially for developing countries. The mechanisms for delivering the collective finance goal, including mobilising private finance, will be a central topic at COP30 in Belém, Brazil, in November 2025.

1.2 At the same time, securing affordable and clean energy is also a core part of achieving broader development outcomes for sustainable economic growth. The World Bank report on progress towards Sustainable Development Goal 7 (SDG7) on Affordable and Clean Energy4 and the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) report on climate finance flows show that there has been significant but uneven progress in this area:5

- Electricity access: almost 92% of the world’s population now have access to electricity. However, 666 million people remain without access, most of whom live in sub-Saharan Africa.6

- Clean cooking:1 billion people still lack access to clean cooking sources, with negative consequences for indoor air quality and human health, as well for as climate change. Progress in this area remains slow.7

- Renewable energy: in 2022, renewables made up 17.9% of the world’s total energy consumption. This is an improvement, but it is not on track for the UAE Consensus commitment to triple the global renewables-based power capacity by 2030.8

- Energy efficiency: this is mainly measured as energy intensity – the ratio of energy supply to gross domestic product, where a decrease in the ratio means that a country produces more with less energy. There are moderate improvements, but not at the pace needed to meet 2030 targets.9

- Financial flows: in 2022, developed countries mobilised $115.9 billion (£86.2 billion) in climate finance for developing countries. This was the first year that countries achieved the goal of mobilising $100 billion (£74.4 billion) towards climate finance.10 However, this is still far below the amount required, based on estimated need. The World Bank found that in 2023, $21.6 billion (£16.1 billion) of climate finance went towards clean energy research and development and renewable energy production, a 29% increase from the year before.11 According to the OECD, the overall volumes of investments going to least developed and low-income countries remain modest in both absolute and relative terms, accounting for less than 10% of global climate flows.12 The World Bank found a similar disparity in climate finance for energy, where the flow to least developed countries dropped by 0.5% in 2023.13

- Rising demand: although the least developed countries currently have some of the lowest energy consumption levels globally, their demand is expected to grow rapidly, underscoring the urgent need for sustainable energy solutions to support inclusive and resilient development.

The purpose and scope of this review

1.3 Successive UK governments have made clear their long-standing commitment to energy transition both domestically and globally. The International Climate Finance (ICF) Strategy, which governs the use of the UK’s £11.6 billion pledge for climate-related aid, has clean energy (a key dimension of energy transition see Box 22) as one of its key pillars.

1.4 This review looks at UK-supported activities and interventions to promote energy transition in developing countries, assessing their effectiveness and their relevance to UK policy objectives. It assesses UK activities to date and provides recommendations to support the development of future UK strategies. This is timely, since the government is currently updating its strategy for the next period of ICF spending and deciding its approach to future replenishments for multilateral climate funds. The review provides the first ICAI assessment of how the UK supports energy transition in developing countries.

1.5 The review focuses on the UK’s ICF spending and its activities in support of energy transition in developing countries from 2021-22 through to 2025-26. Its scope is global, reflecting the UK’s funding through multilateral initiatives, in particular the Climate Investment Funds (CIF) and the Green Climate Fund (GCF), and its work with international alliances with worldwide reach, such as, most recently, the Global Clean Power Alliance launched at the G20 in 2024. In addition, the UK has entered into country-specific partnerships, and the review looks at the most important of these, the Just Energy Transition Partnerships (JETPs).

1.6 We selected the GCF and the CIF, and the JETPs, because they are the largest-value and most significant multilateral initiatives and country partnerships in the UK’s energy transition portfolio. We also identified, together with government departments, a list of 84 programmes and activities that were relevant to energy transition objectives during the review period. The list includes 74 ICF-funded programmes plus ten additional activities, some of which are funded through official development assistance (ODA) and some that are non-ODA. We refer to these programmes and activities (84 in total) as the UK’s energy transition portfolio. Among these, we selected a sample of 12 programmes for more in-depth analysis. When selecting our sample, we kept a thematic focus on energy supply, keeping in mind that this does not cover all of the broad range of activities and sectors that are relevant to energy transition. This was done for the practical reason of ensuring a more focused scope for the programme reviews. (See paras 2.1 to 2.3 for the energy transition definition and Annex 1 on the methodology, limitations and sampling approach.)

1.7 The three questions and sub questions guiding the review are set out in Table 1. They focus on the UK’s strategic objectives, its partnerships and alliances, and its mobilisation and leveraging of funding for energy transition in developing countries.

Table 1: Review questions

| Review question | Sub-questions |

|---|---|

| 1. How relevant and effective is the UK’s strategy for the use of development aid to support its objectives for the global transition to clean energy? | • How well is the UK articulating its energy transition aims, including in relation to other actors? • Are the UK’s priorities focused in the most impactful areas to effect transformational change and systemic shifts and guided by what works? • In what ways has the UK been operationalising its priorities in supporting energy transitions? • What is the added value of the UK’s energy transition approach as part of the overall landscape of support for energy transition? |

| 2. How well is the UK working with its partners and alliances to support developing countries’ energy policies and practices? | • How is the UK’s work with partners and alliances supporting effective delivery of developing countries’ energy transition aims? • How does the UK ensure that its engagement with initiatives and alliances remains coherent and effective? • Does the UK promote inclusive partnerships and alliances to help achieve its energy transition aims? |

| 3. How effective are UK efforts at leveraging and mobilising public and private finance for the global energy transition in developing countries? | • How effective and coherent is the UK’s approach to leveraging and mobilising finance for energy transition, including private climate finance? • How effective are the UK-supported multilateral development banks and multilateral climate funds in mobilising private finance for the energy transition? • How effectively is the UK addressing the barriers to attracting climate finance? • To what extent is the UK harnessing its leadership in financial services to deliver its energy transition objectives? |

1.9 We designed our methodology to assess how well the energy transition portfolio and other activities by the UK government are supporting energy transition in developing countries. Set out in more detail in Annex 1, the design consists of five key components: a strategic review to understand the policy context and structure of UK support for energy transition in developing countries; portfolio mapping to capture the scale and diversity of UK efforts in this area; a multilateral case study, which examined the UK’s influence and investments through two major climate funds, the CIF and the GCF; a country partnership case study focusing on high-profile JETPs, particularly in South Africa and Indonesia; and four thematic deep dives into critical areas such as finance mobilisation, alliance support, transformational change, and just transition barriers. These elements collectively cover both financial and diplomatic UK activities, ensuring a comprehensive review of bilateral and multilateral engagements, with programme selection based on spending size, strategic importance, and relevance to review questions.

2. Background

What is energy transition?

2.1 The term ‘energy transition’ is shorthand for all the elements needed for a global shift away from energy systems based on fossil fuels and traditional biomass, towards systems based on clean and renewable energy sources and modern technologies at the point of use. It includes changing power sources, such as closing down coal mines, eliminating charcoal reliance for cooking, or building wind farms. It is a systemic effort, including constructing more efficient grids to distribute power, creating more efficient and less wasteful energy storage, transforming market and regulatory frameworks, and ensuring that energy systems are resilient in the face of future climate change. Energy transition objectives cover all the sectors of the economy related to energy, including for example urban planning measures to electrify public transport systems or building energy-efficient buildings that are resilient to global warming and climate shocks. Because of this broad remit, various definitions of energy transition are in use, including within different departments and teams in the UK government.

Box 2: Defining energy transition

A common definition of energy transition is provided by the International Renewable Energy Agency. It describes energy transition as the fundamental shift from fossil fuel-based energy systems to those dominated by renewable sources such as wind, solar, and hydropower, with the aim of achieving a net zero carbon energy system by 2050. This transition encompasses decarbonising energy production, modernising grids and energy markets for greater efficiency and resilience, reforming regulatory and financing systems, electrifying end-uses across transport and industry, improving energy efficiency at scale, and integrating system-wide technologies like green hydrogen – going well beyond investments in individual clean energy projects. Achieving global energy transition requires coordinated policy, investment, and infrastructure changes, ensuring system resilience, as well as social behaviour changes, to secure a sustainable, affordable and inclusive energy future that supports economic and social wellbeing.14

ICAI’s review of the UK’s support for energy transition in developing countries also uses this definition, and we have worked with relevant departments in the UK government to identify relevant programming and activities in a range of sectors that fall under this definition.

Energy transition versus clean energy: Clean energy typically refers to specific renewable energy technologies and projects, while energy transition is a broader systemic shift. The latter extends beyond power generation to include the transformation of energy systems, markets, and end-uses, requiring regulatory, financial and technological change that is resilient and sustainable, at scale. In other words, clean energy is one component of energy transition, but the transition itself involves a much wider reorganisation of entire energy systems.

2.2 Energy transition entails a system-wide shift. It involves decarbonising energy systems, switching to ultra-low- or zero-carbon energy sources – often referred to as ‘clean energy’. But it goes far beyond clean energy, as described in Box 2.15 Achieving energy transition globally will require coordinated policy, investment, and behavioural changes to ensure a sustainable, affordable and inclusive energy future.

2.3 If plotted on a graph, the energy transition pathway to achieve this system-wide shift would typically follow the shape of an S-curve,16 illustrating how clean energy sources and energy-efficient technologies – like solar, wind or batteries – move from slow early adoption to rapid growth once they hit a tipping point (around 5-10% market share), driven by falling costs and learning-by-doing. Countries advance their energy transition from ‘emergence’ through to ‘maturity’ along the S-curve, as their technology absorption and use, renewable markets, and ability to attract and manage finance evolve (see Box 3).17 Middle-income countries often accelerate faster along this curve because they have the market size, policy frameworks, and credit capacity to attract both public and private finance. Low-income countries, by contrast, tend to lag on the S-curve, as higher perceived risks, weaker financial systems, and limited infrastructure make it harder to mobilise the capital needed for large-scale, rapid deployment.

Box 3: Different phases of the S-curve for energy transition in developing countries

The energy transition pathway is often described as an S-curve, with slow rates of technological and market absorption at the early ‘emergence’ stage of the transition, followed by a period of rapid ‘diffusion’ in the middle stage, before reaching a slower rate of change again at the final ‘maturity’ stage.

In the early ‘emergence’ phase, seen in many low-income countries, transition is slow as countries build the basic conditions for absorbing new technologies and attracting related investments. Priorities centre on developing the enabling environment: crafting policy frameworks, strengthening institutions, providing technical assistance, and mobilising concessional finance (loans on more favourable terms than what is available at market rates)18 to de-risk investments and expand energy access. These countries require context-sensitive regulation and capacity building to support foundational infrastructure and local skills, with energy transition plans adapted to urgent development needs.19 Getting this enabling environment in place to absorb technological innovation and attract related finance is slow and painstaking.

As countries progress into the ‘diffusion’ phase, progress accelerates as they adopt new technologies and attract diverse financial instruments. Needs shift towards scaling technology deployment and strengthening energy markets. This means attracting diverse investment – such as concessional loans, blended finance (using grants to attract private investment), competitive auctions, and public-private partnerships. Efforts focus on grid modernisation, research, innovation, and creation of a domestic renewable industry.

In the ‘maturity’ phase, policy shifts towards energy system optimisation and integration. Here, the emphasis is on sophisticated financial instruments such as green bonds (regular bonds or loans to specifically finance environmental projects) and demand-side management. Higher-income countries can therefore focus on system flexibility and resilience, and on attracting private finance.20

International organisations, including the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, the International Renewable Energy Agency, the World Bank and the International Energy Agency, highlight the importance of tailored, phased approaches aligned with national context and each country’s stage on the S-curve of transition. Achieving global energy transition requires flexible support – targeted technical assistance, robust policy tools, and innovative finance – matched to individual country priorities and developmental and market realities.

The UK’s energy transition portfolio in support of developing countries

2.4 The UK’s aid spending on energy transition is organised under the umbrella of the International Climate Finance (ICF) Strategy. In 2019 the government pledged to spend a total of £11.6 billion in climate finance over the five-year period from 2021-22 to 2025-26, covering all aspects of support for climate action, both mitigation and adaptation. This commitment was reaffirmed by the new government in 2024.

2.5 The ICF Strategy is structured around four thematic priority pillars: clean energy; sustainable cities, infrastructure and transport; adaptation and resilience; and nature for climate and people. Each pillar sets out a number of objectives, and there is a framework for measuring and assessing results. (See Box 4 on how these pillars relate to the UK’s energy transition goals.)

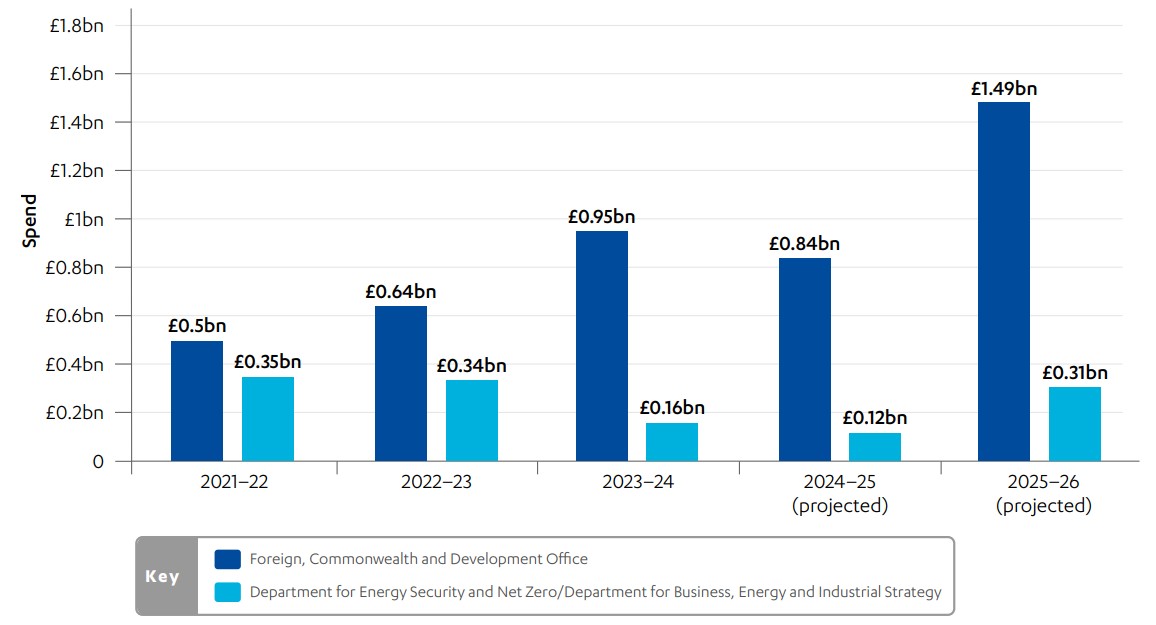

2.6 Spending under ICF is primarily administered and managed by the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO) and the Department for Energy Security and Net Zero (DESNZ),21 with a smaller proportion delivered through the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (Defra) and the Department for Science, Innovation and Technology (DSIT).

2.7 ICF includes a wide range of programmes and instruments including:

- conventional bilateral programmes administered mainly by FCDO, whether grants or technical assistance

- finance for investment in infrastructure through the development finance institutions British International Investment (BII) and the Private Infrastructure Development Group (PIDG)

- contributions to multilateral climate funds (MCFs), most notably the Green Climate Fund (GCF) and the World Bank-administered Climate Investment Funds (CIF) (see Box 7 for more information on these MCFs)

- the climate finance-related share of the UK’s core contributions to multilateral development banks (the World Bank and regional development banks) during this period.22

What the UK’s energy transition portfolio looks like

2.8 The core of the UK’s support for energy transition falls within the ‘clean energy’ pillar of the ICF Strategy. However, energy transition is a multi-dimensional endeavour, with many programmes designed to deliver a range of energy, development, and wider climate-related outcomes. Box 4 sets out how the four priority pillars all involve objectives that are relevant to energy transition.

Box 4: The priority pillars of the International Climate Finance Strategy and their links to energy transition

The UK’s International Climate Finance Strategy (ICF3) is built on four priority pillars:

- clean energy

- sustainable cities, infrastructure and transport

- adaptation and resilience

- nature for climate and people.

Clean energy is the most prominent pillar, directly driving the clean energy shift and wider energy transition through decarbonisation, system reform, and just transition support. Investments in sustainable cities and infrastructure complement this by strengthening grids, storage, transport and efficiency, while adaptation and resilience ensure that energy systems are climate-proofed and able to withstand shocks. Even the nature pillar, although least directly linked, contributes by protecting ecosystems (for example watersheds for hydro, coastal protection for assets) that underpin sustainable and resilient energy systems. The resilience and nature pillars ensure that energy systems endure shocks and stay on track with transition goals, reducing losses and safeguarding gains. Together, these pillars create a platform that supports systemic progress towards a low-carbon, climate-resilient energy future.

2.9 We worked with the relevant government departments to map and delineate the UK’s energy transition portfolio. Together we identified 74 ICF-funded programmes and ten non-ICF-funded activities that were relevant to energy transition and active during the review period from 2021-22 to 2025-26.23 This group of programmes and activities, referred to in the review as the UK’s energy transition portfolio, includes:

- 28 ICF-funded programmes that fall solely under the ICF ‘clean energy’ pillar. These include, for example, Transforming Energy Access, the Mitigation Action Facility, and the Energy Sector Management Assistance Programme.

- 24 ICF-funded programmes that contribute to both ‘clean energy’ and one of the other thematic pillars in the ICF Strategy. These include, for example, UK Partnering for Accelerated Climate Transitions, Climate Compatible Growth, and Supporting Structural Reform in the Indian Power Sector.

- 22 ICF-funded programmes that are not tagged by government as contributing to the ‘clean energy’ pillar, but which ICAI and government departments have identified as contributing to energy transition outcomes. These include, for example, the Market Accelerator for Green Construction, classified under the ‘sustainable cities, infrastructure and transport’ pillar.

- The UK also reports a share of its core contributions to the multilateral development banks (MDBs) as climate finance, and tags this under the ‘adaptation and resilience’ pillar of the ICF Strategy. We have included this in the energy transition portfolio since many MDB investments are relevant to energy transition.

- Ten activities, with small budgets, that are not ICF-funded but contribute to the UK’s energy transition objectives in developing countries. These activities are not eligible to be reported as official development assistance (ODA) and are mainly related to the UK government’s support for international alliances to promote global energy transition. They include, for instance, the Accelerate to Zero Coalition, the Breakthrough Agenda Secretariat, the Global Alliance for Buildings and Construction, and the Global Clean Power Alliance.

- Finally, the UK is a major donor to MCFs, in particular the GCF and the CIF. The funding for these is tagged across all the ICF priority pillars. Since they are key investors in energy transition activities, the UK’s ICF funding of these funds is included in the energy transition portfolio.

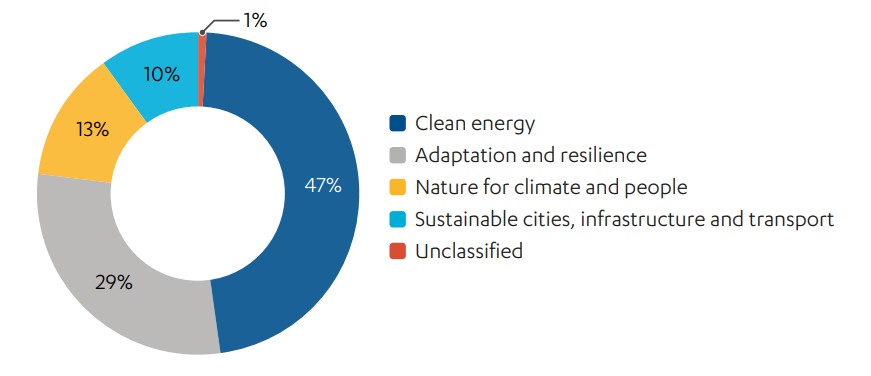

2.10 Figure 1 shows how the full value of the energy transition portfolio is distributed across the four priority pillars of the ICF Strategy. Almost half the portfolio is tagged as clean energy, with adaptation and resilience, at 28%, the second largest category (including the core funding for the MDBs). Nature for climate and people is 13%, while sustainable cities, infrastructure and transport accounts for 10%. The MCFs are tagged across all the pillars, as appropriate.

Figure 1: The UK’s energy transition portfolio is distributed across the international finance climate finance thematic pillars

The total value of the programmes and activities tagged under the ICF pillars identified by the government as its energy transition portfolio, split across the four thematic pillars of the UK’s ICF Strategy from 2021–22 to 2025–26

Source: International climate finance (ICF), ‘ICF Management Information data’, December 2024, unpublished

Description: The pie chart shows the UK’s energy transition portfolio spend and projected spend for the period from 2021–22 to 2025–26, classified according to the four pillars of the UK’s ICF Strategy. ‘Clean energy’ has the largest percentage at 47%, and ‘Adaptation and resilience’ is the second largest segment at 29%. There is a 1% portion for ‘unclassified’ programming that is contributing to energy transition but is not categorised under any of the pillars.

Estimating the value of the UK’s energy transition portfolio

2.11 In total, the UK expects to spend £5.7 billion in ODA on this portfolio of 84 energy transition-relevant programmes and activities over the five-year period from 2021-22 to 2025-26, although final spend figures for 2025-26 are not yet known. However, this is an overestimate of the UK’s true spending on energy transition: while some of those programmes have clean energy and other ICF pillars contributing to energy transition as their primary focus, others include clean energy alongside other climate objectives, or are estimates of the core climate finance-related contributions to MDBs, which are recorded wholly as adaptation and resilience, although they also have various activities that contribute to energy transition.

2.12 We therefore sought to make a more accurate estimate of the UK’s energy-only spend. Looking at programming tagged under the ICF clean energy pillar, we identified a total of £2.7 billion in ODA spending over the five-year review period. This is, however, an underestimate: energy transition goes wider than just clean energy to include other ICF pillars and system-wide support. Additionally, there are important clean energy elements of existing ICF programmes that are not tagged under the ICF clean energy pillar.

2.13 We then employed two different methods to refine our estimate within the range of £2.7 billion to £5.7 billion by using first the ICF pillar tags and second an analysis of delivery channels, which both arrived at a similar conclusion (see Box 5 for a more detailed technical account of how we did this). Our best estimate is that the UK will spend around £3.6 billion in ODA on energy transition over the five-year review period, although there is considerable uncertainty around this figure.

Box 5: The technical explanation of the two estimation methods for the total value of the UK’s energy transition portfolio

Determining the size of the UK’s energy transition portfolio is a challenge due to the inherent limitations of the ICF dataset and the challenges of isolating the impact of programmes with multiple objectives. We used two different methodological approaches to triangulate our results and strengthen the robustness of our estimates. The two approaches are described in this box.

The pillar methodology:

The energy transition portfolio comprises three distinct groups of programmes, defined by how they are tagged against the priority pillars of the ICF Strategy:

- Group 1: This group consists of cross-sector programmes that are not tagged to the clean energy pillar at all. This means it has no energy-tagged budget lines. The total value of Group 1 programmes is £1.25 billion.

- Group 2: This group has cross-sector programmes that have both clean energy and other sector tags. This means that the programmes have some budget lines that are relevant to clean energy and others that are relevant to one or more of the three other priority pillars. The total value of Group 2 is £2.65 billion. Within that overall value, the elements that are tagged as clean energy within Group 2 amount to £0.9 billion, while the rest is tagged to one of the other three priority pillars.

- Group 3: This group consists of energy-only programmes, that is the programmes that have all their budget lines tagged as clean energy. (This group has a total value of £1.8 billion.)

The combined value of all budget lines of the programmes in Groups 1 to 3 constitute the ‘maximalist’, upper bound value of the energy transition portfolio, as shown in Figure 2. This is the total value of all the programmes that the government identified to ICAI as relevant to energy transition.

The ‘minimalist’ scenario, or lower bound (also depicted in Figure 2), includes only the budget lines that were tagged as clean energy. This included all the energy-only programmes in Group 3 and the £0.9 billion tagged as clean energy in the cross-sector programmes in Group 2. In total, this adds up to £2.7 billion, representing the sum of energy-only programmes and the energy-tagged share of cross-sector programmes.

To estimate the proportion of energy transition-related spend in Group 1, which was also identified by the government as relevant for the review, we 1) observed the energy share in cross-sector programmes that had been energy-tagged (Group 2), and noted that the energy-tagged budget lines in this group (£0.9 billion out of a total of £2.65 billion) amounted to 34% of the value. We also 2) reviewed a small sample of individual programme annual reviews from Group 1 and found that approximately 35% of the activities and budget of these programmes were energy-related (despite not being tagged as such).

Applying a 35% pro-rata assumption of the energy pillar spend across Groups 1 and 2 confirmed our best estimate of a total of £3.6 billion for the energy transition portfolio.

The channel estimation methodology:

The energy transition portfolio is delivered through different delivery channels:

- bilateral programmes

- bilateral investment through development finance institutions (DFIs), notably British International

Investment (BII) and the Private Infrastructure Development Group (PIDG)

- multilateral development banks (MDBs)

- multilateral climate funds (MCFs), notably the Climate Investment Funds (CIF) and the Green Climate Fund (GCF).

We looked at the UK’s ICF funding through these different delivery channels including bilateral programmes, bilateral funding to DFIs (BII and PIDG), MDBs (which the government tags as adaptation and mitigation) and the MCFs (which are tagged across the four ICF pillars as appropriate). Based on 2023 annual reports and other relevant reporting,24 we estimate that around 33% (one-third) of ICF core funding to MDBs is relevant to energy transition objectives. And, based on the MCFs’ own reporting,25 we estimate that 50% of funding to the GCF and 70% of funding to the CIF are relevant to energy transition. Adding the 35% coefficient from the pillar analysis to the remainder of the bilateral programmes, separating out the DFIs, MDBs and MCFs and the 100% actual energy tagging of the DFIs, the analysis confirms the best estimate figure of around £3.6 billion for the total energy transition portfolio.

Conclusion

By arriving at a similar total figure of £3.6 billion for the energy transition portfolio using both the pillar methodology and the delivery channel methodology, we have greater confidence that this is the best possible total budget estimate for the portfolio. While this approach is supported by different data sources and methods, it nevertheless rests on the assumption of uniform energy transition relevance across bilateral programming beyond the DFIs, MDBs and MCFs. This assumption may not hold in all cases, particularly for sectors with inherently lower energy linkages, and cannot be validated without project-level financial attribution.

The analysis in this review is, unless otherwise stated, conducted on the full portfolio value, without attempting to break down the programmes into individual budget lines relevant to energy transition, since the dataset does not permit this. Using the full envelope of the portfolio ensures that the analysis is based on an unaltered, reproducible dataset and avoids selective adjustments that cannot be applied uniformly across the portfolio. It also allows us to compare spend data over time (see Figure 3).

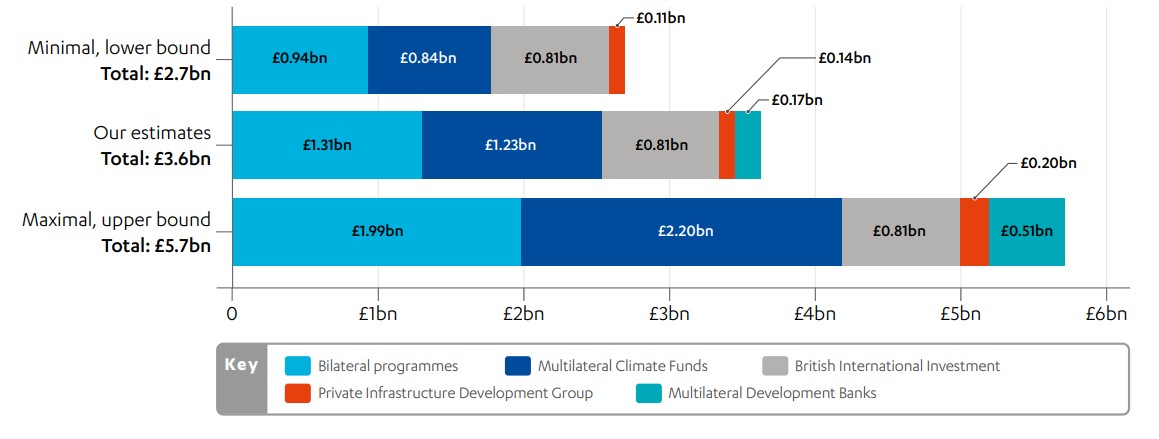

2.14 The bar chart in Figure 2 gives a breakdown of the portfolio, showing the lower bound, minimum value of identified clean energy programmes of £2.7 billion, the upper bound, full maximum value of all energy transition-relevant programmes of £5.7 billion, and our best estimate of energy transition spending of around £3.6 billon.

2.15 Given the challenges of isolating spending on energy transition, the analysis underpinning the findings of this review (see Section 3) is conducted on the full portfolio of 84 programmes and activities. The government is currently working to refine and disaggregate its data to better identify the energy transition-specific contributions within broader programmes.

Figure 2: Estimated value of the UK energy transition portfolio by funding source and inclusion criteria, financial years 2021–22 to 2025–26

A stacked bar chart showing the value of the UK’s energy transition portfolio based on different estimates

Source: International climate finance (ICF), ‘ICF Management Information data’, ’, December 2024, unpublished; Climate funds update database, link; GCF Open data library, link; GCF 2024 Annual progress report, link; GCF unpublished report; CIF 2024 Annual report, link; CIF unpublished dataset; BII website database, link; BII unpublished report; PIDG unpublished report

Description: The stacked bar chart sequence illustrates the energy transition portfolio estimate values based on different inclusion criteria, disaggregated by funding source. The lowest bar represents the maximal, upper bound view, including the total value of all relevant programmes (£5.7 billion). The middle bar represents our estimates (£3.6 billion). And the top bar represents the minimal, lower bound, which includes only the value of programmes with clean energy tagging (£2.7 billion).

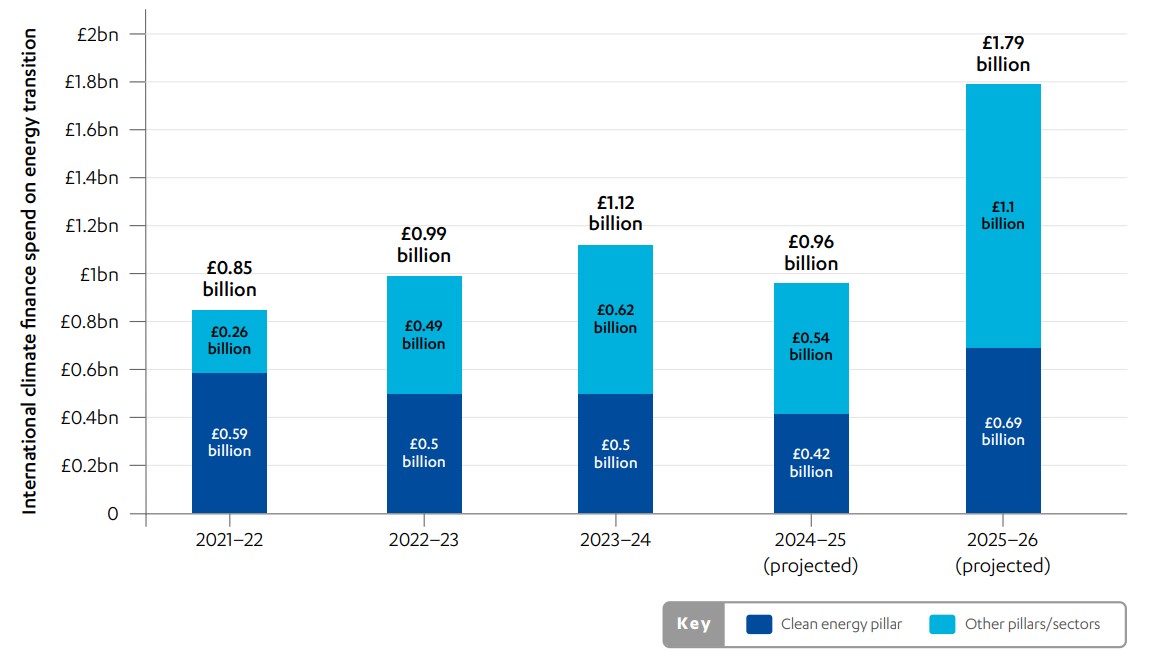

2.16 Figure 3 shows UK ICF spend on the entire energy transition portfolio for the review period, with actual spend to the end of the 2023-24 financial year and projected financial commitments for the next two financial years. The columns show the total value of the portfolio in each year, as well as how much of this spend is tagged as clean energy (thus reflecting the upper and lower bounds of the data analysis in paras 2.11 to 2.15).

Figure 3: The value of the UK energy transition portfolio

Estimated UK international climate finance spending on energy transition from 2021–22 to 2025–26

Source: The figures are derived from ICF unpublished management information data provided by the UK government, December 2024, with estimates for the share of funding relevant to energy transition derived by the ICAI review team

Description: The column chart shows estimated UK ICF spend on energy transition. The total value of the energy transition portfolio rises from £0.85 billion in 2021–22 to £1.1 billion by 2023–24. The projected estimated spend on energy transition drops in 2024–25, before rising to £1.8 billion in 2025–26. The columns also show how much of the energy transition portfolio spend each year is tagged as ‘clean energy’ only in the UK’s ICF reporting. The rest of the spend is tagged against the other three ICF pillars (sustainable cities, infrastructure and transport; adaptation and resilience; and nature for climate and people), sometimes in combination with clean energy.

Alliances and partnerships are central to the UK energy transition work

2.17 The approach set out in the ICF Strategy also includes a range of partnerships, alliances and initiatives. These include:

- Country partnerships, particularly the Just Energy Transition Partnerships (JETPs), which were launched during the UK’s Conference of the Parties (COP) presidency in 2021.26 The JETPs aim to raise ambition, coordinate donor action, and mobilise additional financing, all with strong country ownership. The UK is actively involved in three of the four JETPs: it leads the International Partners Group (IPG)27 in South Africa’s JETP, co-leads the IPG with the EU in Viet Nam’s JETP, and is an active partner in Indonesia’s JETP. (The UK also participates in the Senegal JETP, but on a much smaller scale.) More recently, the UK-Brazil Hubs represent a newer model of country partnership, supporting Brazil’s goals for industrial decarbonisation and green hydrogen.28

- International alliances, such as the Clean Energy Transition Partnership (CETP), which are aimed at different aspects of promoting energy transition in developing countries. Many of these alliances, including CETP, were established under the UK’s COP presidency in 2021. Not all are funded by ICF, but they are central to the 2023 ICF Strategy for advancing climate action, including energy transition, in developing countries.

Guarantees are not scored upfront as aid but may incur future liabilities to the aid budget

2.18 The UK has offered loan guarantees to multilateral lenders (the World Bank and the African Development Bank) to Indonesia (up to £750 million) and South Africa (up to £975 million), as well as commercial debt and equity via PIDG and BII (£371 million in South Africa and £111 million in Indonesia) as the main financial component of UK support for these two countries’ JETPs. Across all four JETPs, the UK has committed £2.3 billion in guarantees, including over £730 million through PIDG and BII, and £28 million in grants and technical assistance.29 Guarantees are a secondary liability, where the UK agrees to take on debt if the debtor cannot fulfil their commitment to the lender. Guarantees do not have any upfront cost to the aid budget, but if the primary debtors are unable to fulfil their commitments, the UK would become responsible for servicing the debt, which would be drawn from the aid budget in future years. In this case, neither South Africa nor Indonesia has taken up the offer of UK-guaranteed loans, so any secondary liability for the UK has not at this point been incurred (on why, see para 3.58).

3. Findings

3.1 This section is divided into three parts, presenting the main findings for each of the three review questions set out in the introduction to this report (see Table 1).

3.2 We first look at the relevance and effectiveness of the UK’s use of development assistance in support of energy transition. We then address how well the UK is working with partner countries and in international alliances to support developing countries’ energy transition, before turning to the UK’s efforts to leverage and mobilise public and private finance for energy transition.

How relevant and effective is the UK’s strategy for the use of development aid to support its objectives for the global transition to clean energy?

3.3 This section examines how effectively the UK uses its international climate finance (ICF) to support energy transition in developing countries. It explores whether the UK’s approach is clearly defined, well targeted, and aligned with its climate and development goals. This includes the extent to which the UK’s approach addresses systemic barriers to energy transition and contributes to transformational change.

The UK’s energy transition efforts in developing countries are highly relevant to addressing the climate crisis and benefit from long-standing political and financial commitment

3.4 A range of strategic frameworks guide the UK’s approach to supporting energy transition in developing countries, setting a stable and committed course for UK efforts over time. The most recent strategy documents include the 2030 Strategic Framework for International Climate and Nature Action (2023), the International Climate Finance Strategy “Together for People and Planet” (2023), and the International Development Strategy (2022, refreshed in 2023). All three present global energy transition as central to UK development assistance objectives and see it as aligned with both climate and poverty reduction goals. UK commitment to the promotion of energy transition has remained stable through changes in ministers and governments. Confirming climate action as central to global prosperity and security, the then Foreign Secretary, speaking in Kew Gardens in September 2024, announced the appointment of a Special Representative for Climate Change with responsibility for driving the global transition to clean energy, and launched the Global Clean Power Alliance.

3.5 This long-standing policy commitment to energy transition can also be seen in the UK’s financial contributions to ICF. The UK’s ICF spend started in 2011 and accelerated for the period covered by this review, as shown in Figure 3 in the previous section.

While overall commitment is strong, the UK’s energy transition portfolio is broad and diverse, which risks a lack of coherence and presents challenges in prioritisation as the UK reduces its aid budget

3.6 The UK’s approach to supporting energy transition in developing countries has largely evolved through a learn-by-doing, adaptive model shaped by international climate negotiations and reactive, programme-level decisions. While the adaptive approach has enabled flexibility, government stakeholders almost unanimously emphasised the need to consolidate learning and shift towards a more strategic and coherent direction. This was also reflected in a June 2023 ICF Management Board review, which flagged risks of incoherence in the energy/mitigation portfolio.

3.7 There is a lack of clarity on how energy transition is defined and operationalised in ICF. As the discussion of the portfolio in paras 2.4 to 2.18 shows, energy transition cuts across all four pillars in the 2023 ICF Strategy, but the strategy does not set out how to pursue this cross-cutting ambition. There is no specific and unified energy transition strategy with a related theory of change setting out key objectives, and timelines and approaches for achieving these across different departments. The Department for Energy Security and Net Zero (DESNZ) developed an overall, umbrella business case for ICF in 2020, but this was focused on ICF overall, not on energy transition, and it only covered the approach of a single department. The lack of a cross-cutting portfolio approach – understood as the strategic management of a diverse mix of delivery channels, programmes, financial instruments, and partnerships – creates a risk to coherence, both at a strategic level and at a programme level. One such area of risk to coherence is when the UK’s bilateral spend and its core support to multilateral bodies provide finance through different channels to the same project. This is, for instance, the case for the Mission 300 initiative for energy access in Africa, which receives UK aid through direct bilateral funding as well as through UK core contributions to the World Bank and the African Development Bank.

3.8 Most government interviewees agreed that a strategic approach to achieving energy transition must address persistent barriers, and recognised that these are consistent across sectors and geographies. Commonly cited barriers include investment risk management, political will, policy stability and identifying bankable project pipelines. Interviewees emphasised that barriers must be addressed through targeted programmes designed to tackle specific constraints at different phases of the transition and across the S-curve, addressing different country circumstances, degrees of technological absorption, and financial readiness (see Box 3 for an explanation of the S-curve in energy transition). Interventions needed to address these obstacles range from early-stage support to improve the enabling environment, notably in low-income countries, to mobilising capital at scale for innovative pilots to lead to commercially viable investments in higher-income contexts. However, although the portfolio is broad and diverse, it is not explicitly structured to address these challenges systematically.

3.9 The lack of a clear strategy will make evidence-based decision making on prioritisation difficult as the UK reduces its official development assistance (ODA) budget from 0.5% to 0.3% of gross national income over a three-year period to 2027. Government stakeholders broadly recognised the need for a clearer energy transition definition and greater strategic coherence, with some advocating for stronger prioritisation and scaling up of proven solutions. The government told us that the next iteration of the ICF Strategy, which is currently under development, will include a theory of change for energy transition.

Programmes in the energy transition portfolio report substantial results in some areas, but accountability for the selection and application of ICF key performance indicators (KPIs) remains limited, which constrains the comprehensiveness of reporting

3.10 Table 2 shows the reported results for the UK’s energy transition portfolio for the three-year period from 2021-22 to 2023-24 (the last year for which we have data) for three ICF KPIs central to the UK’s energy transition goals: the amount of greenhouse gas emissions reduced or avoided; the number of gigawatts (GW) of clean energy capacity that has been installed; and how many people have improved access to clean energy. We recognise that these three KPIs do not cover all relevant dimensions of energy transition.30

3.11 Table 2 shows substantial results: between 2021-22 and 2023-24, 35 million people improved their access to clean energy; the carbon dioxide equivalent of 26 million tonnes of greenhouse gas emissions were reduced or avoided; and 2.1 GW of clean energy were installed. However, only around a third of the programmes in the portfolio report results against any one of these three KPIs, which suggests that the results picture may be incomplete. There are some programmes, notably some of the support to multilateral development banks (MDBs), which do not appear to report to ICF KPIs at all. Accountability for results and reporting is weakened by the fact that individual programmes self-select ICF KPIs, and are only required to select one KPI at a minimum. There is little visibility at portfolio level as to which programmes have selected a given indicator and whether data is actually being collected and reported on selected ICF KPIs.

Table 2: Efforts to support energy transition in developing countries have led to substantial impacts

Reported results for the energy transition portfolio for three key performance indicators: the volume of greenhouse gas emissions reduced or avoided; the installed capacity of clean energy; and the number of people with improved access to clean energy, from 2021 to 2024

| Key performance indicator (KPI) | Programme results for 2021-22 to 2023-24 |

|---|---|

| KPI 2.1: People with improved access to clean energy | 35 million people |

| KPI 6: Tonnes of greenhouse gas emissions reduced or avoided | 26 million tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent |

| KPI 7: Installed capacity of clean energy | 2.1 gigawatts |

Source: This table is derived from unpublished KPI results reporting provided by the UK government, December 2024. It includes reporting by the selected energy transition programmes only and therefore cannot be compared with the cumulative ICF results reporting for the review period. It also does not include the latest ICF KPI data for 2024-25, as we had not received the underlying programme-by-programme dataset for the latest year of reporting by the time of publication. Energy access programmes are best aligned with KPI 2, while renewable energy programmes correspond more directly to KPIs 6 and 7. Programmes would therefore not be expected to report against all three KPIs. They are included for illustrative purposes only.

3.12 Both of the multilateral climate funds (MCFs) reviewed, the Climate Investment Funds (CIF) and the Green Climate Fund (GCF), demonstrate progress on similar metrics. For example, since its establishment in 2008, the CIF has supported 65 million people to cope with the effects of climate change overall, added a cumulative total of 25.9 GW of renewable energy capacity, brought energy access to 3.9 million people, demonstrated the commercial viability of energy access investments, and generated tens of billions of dollars of economic value in local economies.31 About two-thirds of CIF programmes report across the KPIs listed above, and the CIF provides a transparent account of the number of programmes reporting on each indicator on the summary dashboard on its webpage.

The UK has made some early progress in its aim to support transformational change of energy systems in developing countries, but the concept of transformational change is not consistently understood and applied across the energy transition portfolio

3.13 There is broad recognition within the Department for Energy Security and Net Zero (DESNZ) and the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO) of the need for a systemic approach to energy transition. The UK vision is to provide the catalytic change that enables systemic shifts or accelerates climate progress to deliver transformational change in developing countries.32 But while the UK’s vision is clear, it is not yet consistently understood or applied across departments and teams. There is also a lack of clarity on how the efforts across the UK’s broad portfolio of programmes, which covers every aspect of the energy system, can work together and amplify the total impact of the portfolio to achieve transformational change. We heard that work is currently underway to better align programmes and partnerships towards a systemic approach across geographies and sectors.

3.14 ICF KPI 15 assesses the likelihood that specific programmes or interventions will lead to transformational change. KPI 15 is a forward-looking, qualitative indicator aligned with the broader ICF Strategy to promote transformational outcomes. Some programmes in the energy transition portfolio are explicitly expected to deliver transformational impact in their business cases and to report to KPI 15.

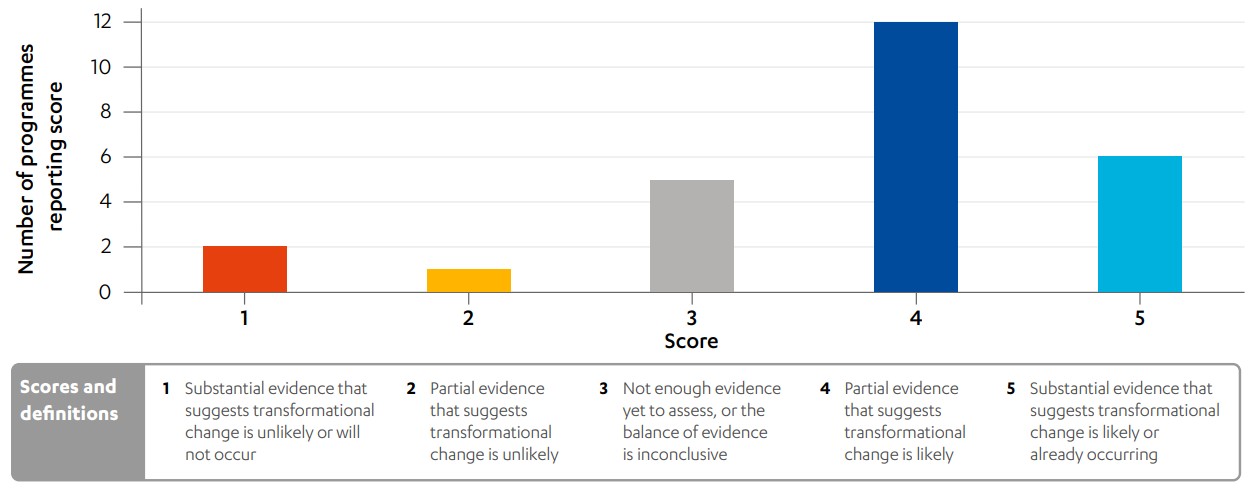

3.15 However, transformational change takes time and is challenging to measure, and the overall reporting towards KPI 15 is limited. Figure 4 shows the results for KPI 15 for the 26 programmes within the energy transition portfolio that report against this indicator. It shows that 12 programmes reported a score of 4, which signifies that there is partial evidence that transformational change is likely. Another six programmes reported a score of 5, meaning that there is substantial evidence that transformational change is likely or already occurring. Three programmes scored 1 or 2 – indicating that there was evidence that transformational change was unlikely.

Figure 4: The majority of energy transition programmes show partial or substantial evidence of transformational change

Column chart showing the likelihood that specific energy transition programmes will lead to transformational change (key performance indicator 15) for financial year 2023–24

Source: This chart is derived from unpublished KPI results reporting provided by the UK government, December 2024

Description: The column chart lists the number of energy transition programmes reporting against KPI 15 on the y-axis, and their distribution of KPI 15 scores, from 1 to 5, on the x-axis. The chart shows that about half of the 26 programmes scored 4 for KPI 15, demonstrating partial evidence of transformational change; six programmes scored 5, indicating substantial evidence; and three programmes scored below 3, suggesting that transformational change is unlikely.

3.16 The best evidenced examples of contribution to transformational change come from the CIF, which has reported substantial evidence that transformational change is likely or already occurring in three programmes. An example of transformational change that the UK’s energy transition portfolio has contributed to is provided in Box 6, on a vast concentrated solar power installation in Morocco financed by the CIF Clean Technology Fund (CTF).

Box 6: Concentrated solar power in Morocco: transformational change in action

The 500-megawatt Noor Ouarzazate Concentrated Solar Power (CSP) complex in Morocco, which supplies clean energy to over one million people and has helped to reduce Morocco’s dependence on imported fossil fuels, was supported by the Clean Technology Fund (CTF) with UK co-financing. It exemplifies transformational change in action. As one of the world’s largest CSP installations, the project added significant renewable energy capacity while catalysing follow-on investments in Morocco and the wider Middle East and North Africa region.

By absorbing early-stage technology and market risks, the CTF played a pivotal role in mobilising private and multilateral finance and demonstrating the commercial viability of solar power in emerging markets. The project also contributed to national energy security, created local employment, strengthened domestic supply chains, and helped embed renewable energy as a central pillar of Morocco’s long-term energy strategy. Its sheer scale has driven down the costs of this technology by 40% and has enabled the Moroccan government to meet its renewable energy target of 42% in 2020, and raise its 2030 target to 53%. The Noor example illustrates how targeted concessional finance can drive systemic, scalable and inclusive energy transitions.

3.17 The GCF does not currently report against KPI 15 but applies the concept of ‘paradigm shift’ to ensure that projects are transformational by design and implementation. Nevertheless, the Independent Evaluation of the GCF’s Energy Sector Portfolio and Approach found that the GCF’s goals and intended pathways in catalysing a paradigm shift in the global energy sector seem less clearly articulated.33 A financing package provided by the GCF and the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development in Egypt is cited as an example. The package included support for tariff reform, technical assistance, and reverse auctions (with one buyer and many sellers), which helped establish a more predictable market environment and enabled private investment in large-scale renewable energy.

3.18 Several of the programmes supported by UK funding beyond the MCFs can demonstrate partial or substantial evidence that transformational change is likely. The challenges in catalysing transformational change were nevertheless raised in numerous interviews. We found that the approach to assessing the evidence for transformational change was not consistent across programmes.

The energy transition portfolio is directed towards higher-emitting, middle-income countries, which can leave lower-income countries underserved, with potential implications for the UK’s overall poverty reduction objective

3.19 The UK’s energy transition portfolio has a strong focus on high-emitting middle-income countries, based on the sound rationale that these countries contribute significantly to global emissions. The rationale is reflected in the UK’s ICF Strategy, its ICF spend, and its choices of multilateral and country partnerships. UK engagement in high-emitting middle-income countries has focused on targeted technical support to advance low-carbon transitions, with potential to serve their large populations living below the poverty threshold, while also promoting green finance and broader UK diplomatic and commercial interests.

3.20 Recent evidence from the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) and the Climate Policy Initiative (CPI) highlights a persistent geographic imbalance in global climate finance flows, which is also evident in the UK energy transition portfolio.34 In 2022, about 70% of all global climate finance was channelled to support middle-income countries, of which 40% went to lower-middle-income countries and 30% to upper-middle-income countries35 Low-income countries received approximately a 10% share of flows, although in absolute terms the volume of financing to low-income countries as well as small island developing states has increased substantially over time.36 Of the remaining amount, 18% is geographically unallocated while 2% goes to high-income countries. MDBs and MCFs struggle to channel support to the poorest countries, with both allocating less than 10% of their climate finance to low-income countries (30% of MCF financing remains geographically unallocated), according to the OECD analysis.37 As of July 2025, the GCF reported that 29% of its funding was targeted towards least developed countries, and 12% towards small island developing states,38 which is a substantially higher proportion than the prevailing 10% average allocation to low-income countries. The CPI’s Global Landscape of Climate Finance 2025 report found that 79% of global climate finance was mobilised in three regions: East Asia and the Pacific, Western Europe, and the US and Canada, with a trend towards a further concentration of finance in these regions and China dominating the first region.39 If looking only at private finance, middle-income countries benefited from more than 50% of total private finance mobilised in the period 2020-2023, in part because they are in general perceived as lower-risk investment environments than low-income countries.40 Most private climate finance flows to larger, creditworthy economies, notably China, leaving lower-middle-income and low-income countries with increasingly constrained fiscal space reliant on grants and a diminishing pool of concessional finance.

3.21 In our analysis of data from the GCF, the CIF, British International Investment (BII) and the Private Infrastructure Development Group (PIDG) on their geographic financial allocations to single countries during the review period, there is a strong representation of upper-middle-income countries such as South Africa (£208 million) and Indonesia (£184 million), and lower-middle-income countries such as India (£876 million) and Egypt (£164 million), and inclusion even of high-income countries, notably Barbados (£71 million), where high-income countries are eligible through MCFs such as the GCF. Aggregating from the data on single-country funding provided by the GCF, the CIF, BII and PIDG, country allocations are distributed as follows: 75% is directed to lower-middle-income countries, 12% to upper-middle-income countries, and 3% to high-income countries, with only 10% allocated to low-income countries during the review period.

3.22 The available ICF data does not allow us to determine exactly the geographic spread of all the UK’s energy transition activities. Of the programmes in the energy transition portfolio, more than 90% were geographically unspecified in the ICF data. For instance, multi-country programmes (of which there are many) are excluded from the overall geographic breakdown by individual countries. The same is the case with the allocations by MCFs and development finance institutions (DFIs) to multi-country programmes. In addition, the data analysed does not include pre-2021 project approvals from the MCF and DFI data. The figures reported separately by the GCF are above the averages noted across the ICF data. However, the trend towards predominantly supporting middle-income countries is clear.