UK aid for sustainable cities

Score summary

We find that UK aid for sustainable cities generally focuses on areas of comparative advantage, and that the portfolio is broadly aligned with Sustainable Development Goal 11. However, a lack of strategic direction has led to missed opportunities to leverage the UK’s strengths. Some UK technical assistance grants are supporting cities in middle-income countries which may be able to finance the assistance themselves. Although the climate relevance of urban development work has increased, more focus is needed on climate adaptation and there are only isolated examples of programmes using nature-based solutions. The UK is making efforts to align its urban development work with the national, subnational and local priorities of the countries where it is delivering aid. However, many interventions lack targeted pro-poor interventions and do not focus sufficiently on how they will benefit the poor. We found that the UK has been particularly strong in providing services for urban development such as planning, feasibility studies, local revenue administration and expenditure management, and data collection. We found examples of UK support resulting in a stronger focus on social inclusion and resilience in urban planning. The UK also has a good track record of supporting the incorporation of citizen voice into planning. We saw strong examples of the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office funding demonstration projects and helping to develop innovative financing structures, with the potential to mobilise further private investment in sustainable cities, but little evidence of market-building. Despite the relevance and effectiveness of much of the sustainable cities portfolio, we found that fragmentation across programmes and investments hinders coordinated action and effective delivery of aid. There is a lack of effective coordination between UK departments and in-country teams delivering aid for sustainable cities. The ability of embassies and high commissions to deliver demand-driven and context-specific programming is also variable, given the overall shortage of specialist urban and infrastructure advisers. We also found that the UK has failed to communicate clearly on its objectives and comparative advantage on sustainable cities, which undermines more systematic collaboration.

| Individual question scores | ||

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Relevance: Does the UK have a clear and credible approach to promoting sustainable cities that aligns with its broader objectives? |  |

| 2 | Effectiveness: How effective is the UK's support for urban programmes achieving its intended results on sustainable cities? |  |

| 3 | Coherence: How coherent is the UK's approach to promoting sustainable cities? |  |

Acronyms and glossary

| Acronyms | |

|---|---|

| BEIS | Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy (dissolved in February 2023 and separated out into the Department for Energy Security and Net Zero, the Department for Science, Innovation and Technology, and the Department for Business and Trade) |

| BII | British International Investment (formerly CDC Group) |

| BIP | British Investment Partnerships |

| CSO | Civil Society Organisation |

| DAC | Development Assistance Committee of the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development |

| Defra | Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs |

| DFID | Department for International Development (merged with the Foreign and Commonwealth Office in September 2020) |

| DESNZ | Department for Energy Security and Net Zero |

| DLUCH | Department for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities |

| DSIT | Department for Science, Innovation and Technology |

| FCO | Foreign and Commonwealth Office (merged with the Department for International Development in September 2020) |

| FCDO | Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (created through the merger of the Foreign and Commonwealth Office and the Department for International Development in September 2020) |

| G7 | The Group of Seven, an international forum consisting of the UK, Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Japan and the US. |

| HMG | His Majesty’s Government |

| ICF | International Climate Finance |

| NBS | Nature-based solutions |

| NDC | Nationally Determined Contribution |

| NGO | Non-governmental organisation |

| ODA | Official Development Assistance |

| PIDG | Private Infrastructure Development Group |

| UN Habitat | United Nations Human Settlements Programme |

| Glossary of key terms | |

| Bilateral aid | Bilateral aid represents flows from official (government) sources directly to the recipient country. |

| Centrally managed programme | ODA-funded programme that is managed from FCDO headquarters in the UK. |

| Climate adaptation | Climate adaptation refers to changes to processes, practices and structures in order to adjust to the current or expected effects of climate change. |

| Climate mitigation | Climate mitigation encompasses actions taken to limit climate change by reducing emissions of greenhouse gases or removing those gases from the atmosphere. |

| Climate resilience | Climate resilience refers to the capacity or ability to anticipate and recover from climatic events or impacts in a timely and efficient manner. |

| Development Assistance Committee (DAC) | The OECD Development Assistance Committee is an international forum of many of the largest providers of aid. The DAC currently has 32 members and its objective is to promote development co-operation in order to contribute to the implementation of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. |

| Imputed share of multilateral ODA | The share of the UK’s core contributions in support of a multilateral organisation that have gone to a recipient country or sector. In this case, we use imputed multilateral to signify the share of the UK’s core multilateral contributions that have funded activities badged as ‘Urban Development and Management’. |

| Informal settlement | Informal settlements are residential areas where inhabitants have no security of tenure, occupying land or buildings which are legally owned by other individuals or the government. In addition to lack of tenure, the United Nations Human Settlements Programme also characterises informal settlements as neighbourhoods that lack access to basic services with housing that may not comply with current planning and building regulations. |

| Market | A mechanism through which economic agents interact to exchange goods and services during which price is determined. |

| Market building | Deliberate interventions by national governments or international organisations to create or strengthen markets to promote inclusive and sustainable economic growth. |

| Market development | The expansion of existing markets or creation of new markets that positively supports inclusive and sustainable economic growth. |

| Multilateral aid | A multilateral organisation is an international organisation whose membership is made up of member governments which are its primary source of funds. Multilateral aid is delivered through international institutions such as the World Bank. |

| Multi-bi | A donor can contract a multilateral agency to deliver a programme or project on its behalf in a recipient country: the funds are typically counted as bilateral flows, and often referred to as multi-bi. |

| Nature-based solutions | Nature-based solution is an umbrella term for interventions that are designed to protect, sustainably manage, or restore natural ecosystems and address societal challenges such as climate change, human health, and food and water security, simultaneously providing human well-being and biodiversity benefits. |

| Slum upgrading | Slums are considered a specific type of informal settlement, defined by UN Habitat as the most excluded form of informal settlements, characterised by poverty and large agglomerations of dilapidated housing, and often located in the most hazardous urban land. The United Nations Human Settlements Programme defines slum households as suffering from one or more of the following: 1) Lack of access to improved water source, 2) Lack of access to improved sanitation facilities, 3) Lack of sufficient living area, 4) Lack of housing durability and 5) Lack of security of tenure. Slum upgrading is a key component of Sustainable Development Goal 11.1, which aims to “ensure access for all to adequate, safe and affordable housing and basic services and upgrade slums”. |

Executive summary

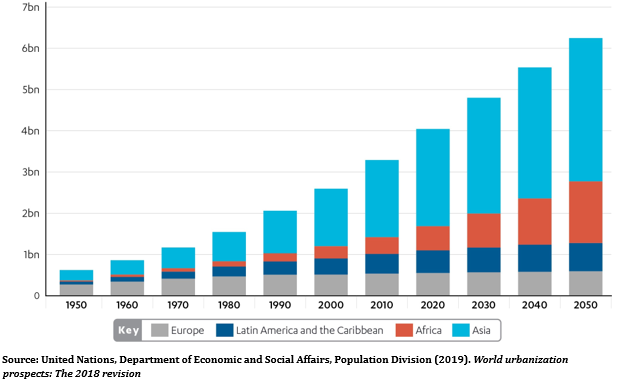

According to the UN, more than two-thirds of the global population will reside in cities by 2050, with rapid growth of urban populations in Asia and Africa. Well-managed urbanisation can drive national development by boosting productivity and accelerating economic growth. However, rapid unplanned urbanisation poses major risks, including informal and poorly serviced housing settlements, environmental degradation, unemployment and poverty. Urbanisation is also a significant driver of climate change, contributing to increased greenhouse gas emissions through altered land-use patterns and changes in energy consumption. Cities are therefore at the heart of global sustainability efforts, as recognised in the 2030 Sustainable Development Agenda and the Paris Agreement. Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 11 has set an objective to create “inclusive, safe, resilient, and sustainable” cities and communities, with a focus on ensuring access to basic services, energy, housing, transport and green spaces.

Promoting sustainable cities has been part of UK development assistance for many years, accounting for an estimated £1.3 billion in bilateral and multilateral aid between 2015 and 2022, including development investment. The Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO) and its predecessors, the Department for International Development (DFID) and the Foreign and Commonwealth Office (FCO), accounted for the majority of this spending. However, UK support to sustainable cities has also been delivered by several other departments, including the former Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy (BEIS), the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (Defra), and the UK’s development finance institution, British International Investment (BII, formerly CDC Group).

The purpose of this review is to assess the relevance, coherence and effectiveness of this support, from an environmental, social and economic perspective. The review builds on previous ICAI work, including a 2018 review of DFID’s transport and urban infrastructure programmes and a number of reviews of the UK’s international climate finance. Our methodology included country case studies of UK programming in Indonesia and South Africa.

Relevance: Does the UK have a clear and credible approach to promoting sustainable cities that aligns with its broader objectives?

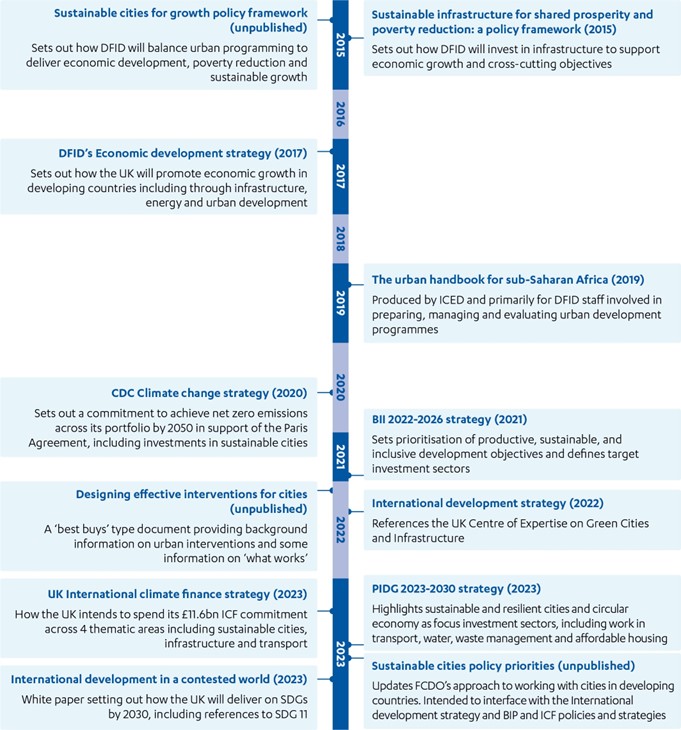

Since 2015, the UK’s support for sustainable cities has diversified away from an early focus on urban infrastructure and slum improvement to a wider portfolio of programmes covering urban planning, transport, economic growth and climate resilience. We find that the UK generally focuses on areas where it has a comparative advantage, and that the portfolio is broadly aligned with SDG 11. Early in our review period, DFID produced, but did not publish Sustainable cities for growth policy framework, which outlined an approach to urban development. Later policies and strategies show less of a focus on cities until the 2023 UK International climate finance strategy, which includes “sustainable cities, infrastructure and transport” as one of its four pillars. The recently published White paper on international development (2023) includes a commitment to “work with cities to create infrastructure services that are resilient and sustainable (SDG 11) and help realise their potential to drive growth and create jobs”.

Between 2015 and 2022, we found a growing lack of clarity on the UK’s approach to sustainable cities, including its comparative advantage and objectives. The lack of strategic direction has led to missed opportunities to leverage the UK’s strengths, such as in mobilising finance. From around 2019, FCDO made a decision to disengage from affordable housing while continuing to invest through BII and the Private Infrastructure Development Group (PIDG), but without a clear plan for targeting those on incomes below levels usually acceptable to commercial investors. Some UK technical assistance grants are supporting cities in middle-income countries, which may be able to finance the assistance themselves, although there may also be non-financial benefits associated with the grants such as access to UK networks. The UK’s stated objective of working in secondary cities has the potential to make a distinctive and influential contribution, but in practice the UK has made little progress in systematically integrating this across the portfolio, despite some good individual interventions. The lack of strategic direction has made it increasingly difficult to ensure relevance across a portfolio distributed between different departments and focus areas, without a shared overall purpose.

Although the UK’s work on urban development has not traditionally had a strong climate focus, its climate relevance has increased. So far, most of the climate-related programming has had a mitigation focus – that is, helping to reduce emissions – rather than adaptation (helping cities deal with the impacts of climate change, such as more extreme weather). UK officials working on sustainable cities recognise this imbalance and recent programme designs pay greater attention to adaptation. One area where the UK has failed to invest is in ‘nature-based solutions’, other than some isolated projects, although the UK has identified this as an area for future investment.

The UK is making efforts to align its urban development work with national, subnational and local priorities. Several programmes designed earlier in our review period had made efforts to incorporate the views of local communities and stakeholders. However, the UK’s sustainable cities portfolio has shown a declining focus on poverty reduction over time. Many interventions lack targeted pro-poor interventions and do not focus sufficiently on how they will benefit the poor.

We award a green-amber score for relevance on the basis that programming is generally aligned with stakeholder needs and priorities, while noting a significant risk to this rating in the absence of a clearer strategic direction for the portfolio.

Effectiveness: How effectively is the UK’s support for urban programmes achieving its intended results on sustainable cities?

The UK has been particularly strong in providing services for urban development such as planning, feasibility studies and data collection. The UK has helped cities improve their master plans and strategies, which has helped shape investment plans. Several programmes have helped improve access to good-quality local data, which have informed the development of water, energy and other resources. The UK has also helped improve local revenue administration and expenditure management. We found examples of UK support resulting in a stronger focus on social inclusion and resilience in urban planning. The UK also has a good track record of supporting the incorporation of citizen voice into planning.

However, evidence of concrete results from these upstream services was not easy to find. A lack of consistent results reporting meant that there were relatively low amounts of data on the effectiveness of a diverse portfolio. In some cases, it is still too early to identify results on the ground.

We saw strong examples of FCDO investing in demonstration projects and helping to develop innovative financing structures, with the potential to mobilise further private investment in sustainable cities. For example, FCDO was instrumental in supporting the issue of Kenya’s first green bond, which will help to develop broader green bond markets for the country. UK development finance has also supported innovative investments in affordable housing that have helped leverage private finance into urban housing.

The Africa Cities Research Programme has completed initial studies to identify priorities in participating cities. These provide a foundation for future work investigating the political economy of cities, cities as systems, and specific sectors such as affordable housing. However, the programme is not yet advanced enough to allow for a judgement on effectiveness.

Overall, despite scarce results data, we heard sufficient positive feedback from city officials and other stakeholders and saw enough evidence of improvements in city governance and urban planning to award a green-amber score for effectiveness.

Coherence: How coherent is the UK’s approach to promoting sustainable cities?

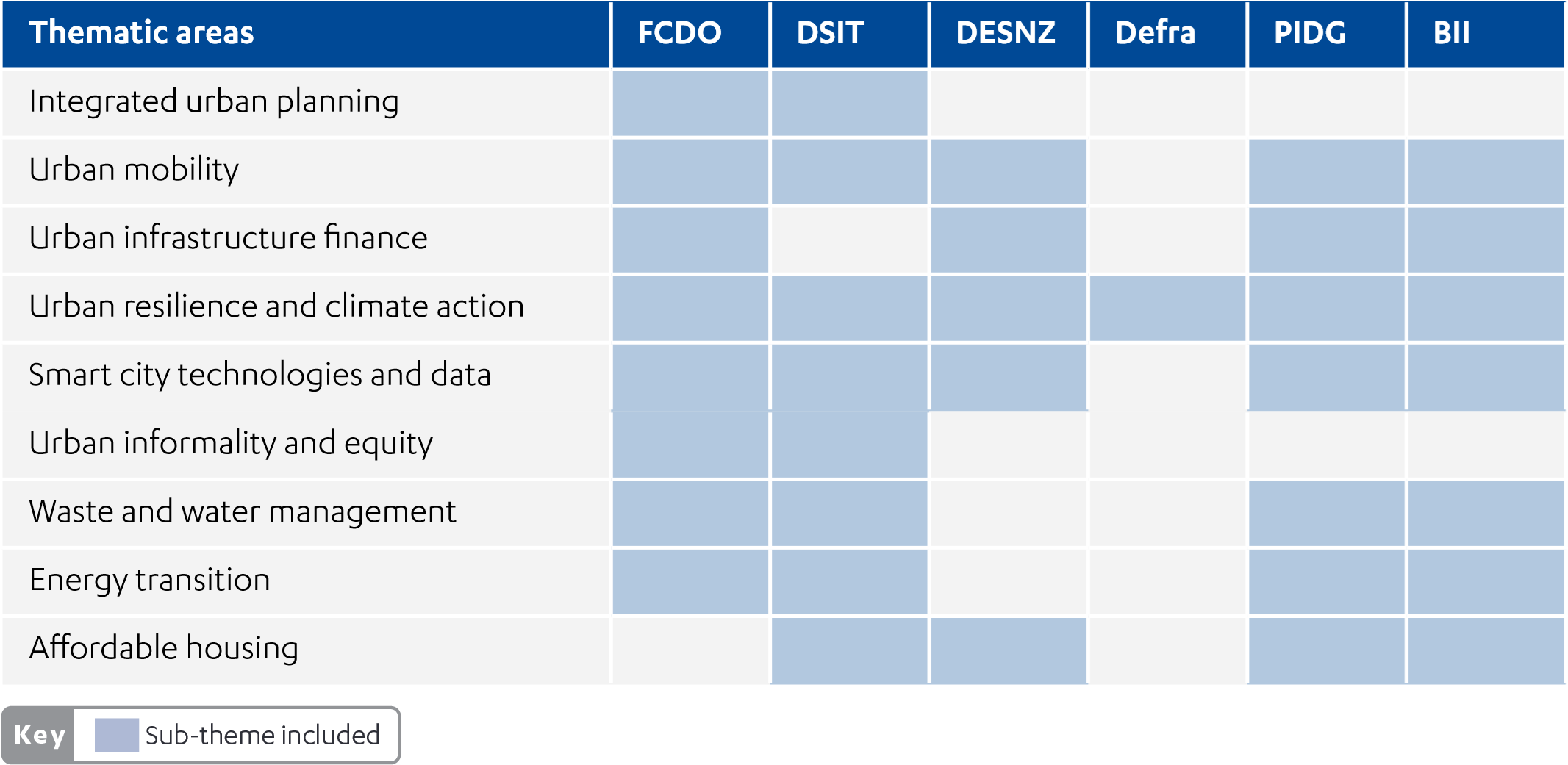

Fragmentation across the UK’s programmes and investments on sustainable cities hinders coordinated action and effective delivery of aid. There is no single entity responsible for overseeing UK aid for sustainable cities, nor a clear allocation of roles and responsibilities, either within FCDO or across departments. Programming is distributed across several departments, notably the Department for Energy Security and Net Zero, the Department for Science, Innovation and Technology (formerly BEIS) and, to a smaller extent, Defra. This fragmentation increases the time and resources needed to communicate and coordinate activity.

The coherence of sustainable cities programming has been further diminished by aid budget reductions and the FCDO merger. We found a lack of readily available information about which urban programmes had been cut back, delayed or terminated. While the FCDO merger presented an opportunity to rationalise UK aid for sustainable cities under one banner, it also created new coordination challenges and resulted in some loss of expertise.

There is a lack of effective coordination between UK departments and in-country teams delivering aid for sustainable cities. The ability of embassies to deliver demand-driven and context-specific programming is also variable, given an overall shortage of specialist urban and infrastructure advisers.

The creation of British Investment Partnerships, a government initiative to mobilise UK expertise and development finance, has provided a platform for coordination with the potential to support a more joined-up approach to funding sustainable cities. There is potential for more structured engagement between FCDO and BII on their respective approaches to sustainable cities.

The number of infrastructure and urban advisers in FCDO has declined in recent years. A new Centre of Expertise in the area is intended to fill the gap in expertise, but is still in the early stages of development.

The UK generally collaborated well with other development partners in its programming. However, it has failed to communicate clearly on its objectives and comparative advantage on sustainable cities, which undermines more systematic collaboration. The UK’s engagement with partners has also been undermined by a lack of continuity in personnel.

We award an amber-red score for coherence. UK aid for sustainable cities is not being managed as a coherent whole, and the UK failed to communicate its approach to partners, which hinders collaboration.

Recommendations

Recommendation 1: The UK needs to conduct a portfolio-wide evaluation of its interventions to support sustainable cities to better understand what has been effective, both in central and country-based programming, and to assure value for money.

Recommendation 2: Following the portfolio evaluation, FCDO should convene UK departments and external partners in a collective strategic planning process for sustainable cities work.

Recommendation 3: British International Investment (BII) and the Private Infrastructure Development Group (PIDG) should develop a credible model for supporting affordable housing for people in the bottom 40% income category in any country, drawing on learning from other development finance institutions and the development capital portfolio.

Recommendation 4: The UK should better align its technical assistance in urban settings with securing private and public finance.

Recommendation 5: The UK should rebalance its investments in climate action in urban settings towards climate adaptation (relative to mitigation).

Recommendation 6: The UK should support development and investment in urban nature-based solutions (NBS) as a key solution for climate adaptation and resilience in developing countries.

Recommendation 7: The UK should develop mechanisms for seeking reimbursement or co-finance in cash or kind from the partner country for its technical advisory services for sustainable cities in upper- and lower middle-income countries.

1. Introduction

1.1 Cities are central to development and poverty reduction. The clustering of people, businesses, industries and services in well-run cities promotes innovation, entrepreneurship and productivity growth. It generates prosperity not just for urban populations, but also for rural and semi-rural areas, through complex economic and social networks. However, rapid, unplanned urbanisation poses major risks to the development process, including the development of informal and poorly serviced housing settlements, environmental degradation, unemployment, poverty and inequality. Poorly planned cities are also more vulnerable to the impacts of climate change. Ensuring that cities deliver on the promise of sustainable development requires the right mix of public and private investment and supporting laws and institutions. Box 1 sets out key international commitments on promoting sustainable cities.

1.2 Support for urban development is a longstanding element of UK development assistance. This review assesses UK aid in support of sustainable cities, from an economic, social and environmental perspective. It covers the period since 2015, when the UK adopted a commitment to scaling up support for urban development, “with a focus on harnessing the opportunities of cities as engines of growth that can support job creation and poverty reduction”. It includes aid-funded programmes, research, and development investment, including through British International Investment (BII, formerly CDC Group) and the Private Infrastructure Development Group (PIDG), both of which provide investment finance to companies involved in urban development. The review also covers the UK’s policy engagement and international advocacy on sustainable cities and its efforts to mobilise other sources of development finance.

1.3 The Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO), together with its predecessor departments, the Department for International Development (DFID) and the Foreign and Commonwealth Office (FCO), is the primary spending department for the sustainable cities portfolio. However, a number of other departments and bodies also contributed to the portfolio over the review period, including the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (Defra), the Department of Energy Security and Net Zero (DESNZ) and the former Department for Business, Energy, and Industrial Strategy (BEIS).

1.4 The review examines the relevance, effectiveness and coherence of the sustainable cities portfolio. Our review questions are summarised in Table 1.

Box 1: How this review relates to international agreements for sustainable cities

SDG 11: Sustainable cities and communities

The 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) are a universal call to action to end poverty, protect the planet, and ensure that all people enjoy peace and prosperity. Comprising ten targets, SDG 11 focuses on cross-cutting sectors within sustainable urbanisation, including housing, transport, green public spaces, disaster risk reduction, environmental management and cultural heritage. It also advocates for supporting the “positive economic, social and environmental links between urban, peri-urban and rural areas by strengthening national and regional development planning”.

The 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) are a universal call to action to end poverty, protect the planet, and ensure that all people enjoy peace and prosperity. Comprising ten targets, SDG 11 focuses on cross-cutting sectors within sustainable urbanisation, including housing, transport, green public spaces, disaster risk reduction, environmental management and cultural heritage. It also advocates for supporting the “positive economic, social and environmental links between urban, peri-urban and rural areas by strengthening national and regional development planning”.

New urban agenda

Adopted at the United Nations Conference on Housing and Sustainable Urban Development (Habitat III) on 20 October 2016, The New Urban Agenda is the first internationally agreed document outlining the cross-cutting urban dimensions of the SDGs. The framework provides guidance to address both the challenges and opportunities of urbanisation and development, focusing on 11 SDGs that include targets with an urban component. Since its publication, The New Urban Agenda has increasingly been regarded by UN member states as a roadmap to localising the SDGs. The UN Secretary-General has submitted two reports on progress in the implementation of the New Urban Agenda to the UN General Assembly, in 2018 and 2022. The most recent report endorses the growing conception of the New Urban Agenda as a road map for the “implementation and localisation of the 2030 Agenda in an integrated and coordinated manner at the global, regional, national, subnational and local levels”.

Paris Agreement

The Paris Agreement is a legally binding international treaty on climate change, endorsed by the 196 national governments which form the Conference of Parties (COP) of the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) in December 2015. The Agreement entered into force on 4 November 2016, two weeks after the adoption of the New Urban Agenda. Since its publication, countries have pledged specific contributions – formally known as Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) – to achieve the Paris Agreement’s goal of limiting the increase in the global average temperature to well below 2°C above preindustrial levels. To date, over two-thirds of the 164 submitted NDCs show clear references to urbanisation in the context of national priorities for reducing emissions and adapting to climate change.

Table 1: Our review questions

| Review criteria and questions | Sub-question | |

|---|---|---|

| Relevance: Does the UK have a clear and credible approach to promoting sustainable cities that aligns with its broader objectives? | •To what extent does the UK’s sustainable cities portfolio balance the objectives of climate change adaptation and mitigation, promoting economic growth, poverty alleviation and the development of safe and inclusive cities for marginalised groups, including women and children? •To what extent has the design of the sustainable cities portfolio focused on addressing the most significant constraints to sustainable urbanisation? •How well does the UK aid approach to sustainable cities support inclusive urbanisation, economic growth and poverty reduction? •How well does the UK’s approach align with the policies and priorities of local actors responsible for management and governance of cities and promote accountable governance? | |

| Effectiveness: How effectively is the UK’s support for urban programmes achieving its intended results on sustainable cities? | •How effectively has UK aid contributed to making cities more prosperous, inclusive and sustainable? •How well does the UK mobilise other sources of finance for sustainable cities, including multilateral funding and private investment? •How well does the UK use its influence to strengthen the effectiveness of multilateral programming? •Is FCDO making efforts to maximise value for money? | How effectively has UK aid contributed to making cities more prosperous, inclusive and sustainable? |

| Coherence: How coherent is the UK’s approach to promoting sustainable cities? | •How well does the UK ensure coherence across its ODA programme to promote action on sustainable cities? •To what extent does UK aid complement the efforts of other development partners to promote action on sustainable cities? |

2. Methodology

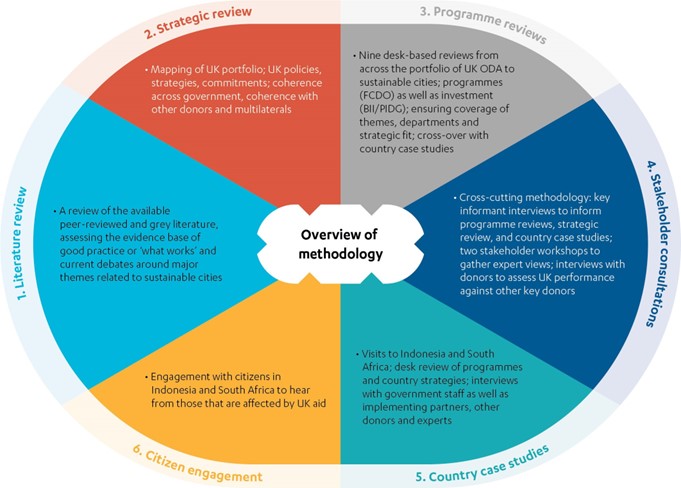

2.1 Our methodology for this review comprised six reinforcing components (see Figure 1).

- Literature review: A review of the available peer-reviewed and grey literature, assessing the evidence base of good practice or ‘what works’ and current debates around major themes related to sustainable cities, such as economic growth, inclusion, sustainability, municipal governance and finance.

- Strategic review: A review of the strategies, policies and commitments relevant to the UK’s sustainable cities portfolio.

- Programme reviews: Desk reviews of a sample of programmes and investments, selected to cover different channels and instruments.

- Stakeholder consultation: Key informant interviews supported our strategic review, programme reviews and country case studies, as well as stakeholder workshops involving the private sector, academics and civil society organisations.

- Country case studies: We conducted two country visits of Indonesia and South Africa. The country case studies assessed the UK’s aid for sustainable cities in each country, and involved consultations with UK officials, implementing partners, other donors, and country counterparts at national and city levels.

- Citizen engagement: We consulted with people directly or indirectly affected by UK aid for sustainable cities in Indonesia and South Africa, to determine whether the UK’s support for sustainable cities has been relevant to their needs and priorities and has resulted in tangible benefits.

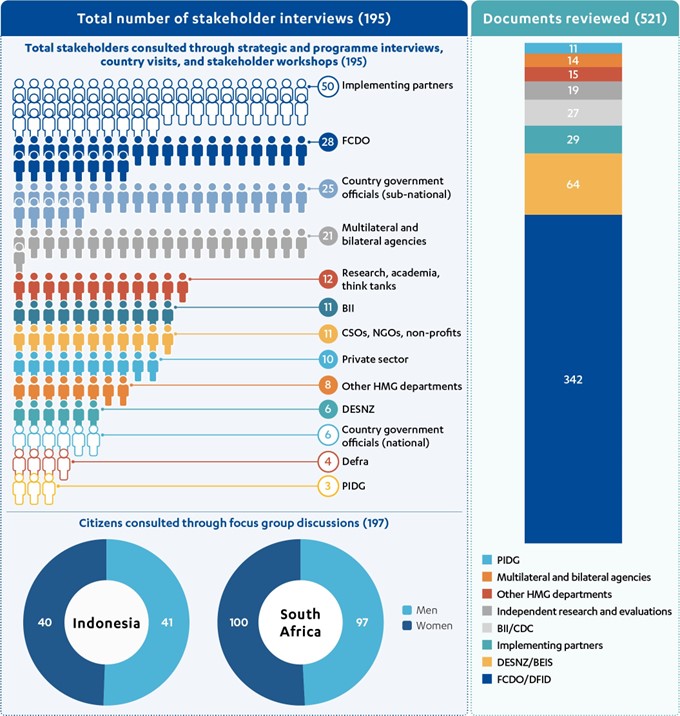

- Altogether, we conducted 45 interviews in the UK with 58 key stakeholders, including 34 UK government officials, and reviewed over 500 documents (see Figure 2). Through our country visits, we conducted 69 interviews with over 110 individuals in Indonesia and South Africa. Through our citizen engagement, we also collected feedback from 81 individuals in Indonesia and 197 in South Africa.

- The methodology and approach were independently peer-reviewed and are further detailed in our approach paper. Some of the main limitations to our methodology are listed in Box 2.

Box 2: Limitations to the methodology

Geographical focus: Our choice of two upper-middle-income countries as case studies means that our country evidence has less of a focus on programming in low-income settings. However, given the large inequalities of income and opportunity seen within the two case study countries, we have been able to cover programming aimed at poverty reduction. By visiting secondary cities in those countries, we also gained insights into programming in lower-capacity environments. Our programme desk reviews included programming in low-income countries.

Breadth of sample: We selected a sample of nine programmes and investments from the sustainable cities portfolio to review in depth, out of 98 programmes and investments that we identified as active over the review period. This sample is not fully representative of the UK’s sustainable cities portfolio. However, the sample covered a broad range of programming, including programmes operating globally and across the UK’s strategic focus areas, as well as different types of funding.

Availability of data: We reviewed performance through a primarily qualitative assessment of documentary and interview evidence. However, quantitative analysis of the portfolio, in particular an in-depth review of results, was not possible due to the lack of available data. Variable levels of programme monitoring and evaluation, a low number of independent programme evaluations, and inconsistent results gathering across a fragmented portfolio meant that a cross-portfolio analysis of quantitative results data could not be carried out. While our methodology enables sufficient triangulation for us to be secure in our findings, a portfolio-wide set of performance metrics would allow for more strategic tracking and evaluation of the UK’s contribution to sustainable cities as a whole.

Figure 2: Our data collection

3. Background

Cities and global development

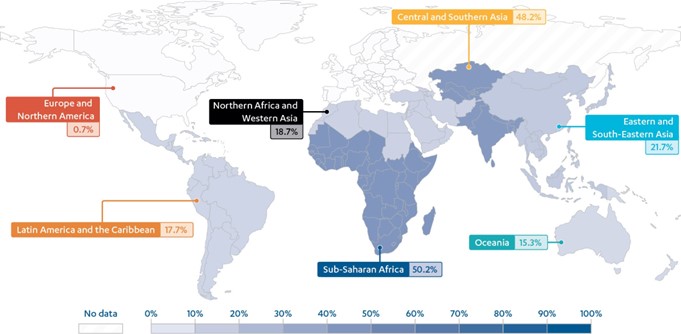

3.1 More than half of the world’s population – 4.4 billion people – live in cities, generating over 80% of global GDP. The UN’s World urbanization prospects forecasts that, by 2050, two-thirds of all people will live in cities, with over 90% of urban population growth occurring in Asia and Africa (see Figure 4).

Figure 3. Urban populations by region, 1950-2050

3.2 Cities are vital for economic growth and national development. In well-managed cities, agglomeration – the clustering of skilled people, markets and amenities – raises productivity by facilitating networking, collaboration and information sharing. This accelerates the generation of knowledge, technology and innovation, driving a virtuous circle of rising prosperity and further economic concentration. Cheaper, faster and better infrastructure – both physical and digital – has enabled many megacities to create jobs at scale through participation in global value chains.

3.3 While urbanisation and economic transformation have gone together in most parts of the world, this is not necessarily the case. In poorly planned and managed cities, excess pressure on infrastructure, services, land and housing can be locked in, undermining productivity and leading to urban poverty and inequality. It can lead to an increase in the share of jobs in the informal sector, where women are often over-represented, exposing workers to insecure or dangerous working conditions.

3.4 Lack of investment in affordable housing can also create informal settlements, which are linked with poor health, crime and other social problems. The UN reported that over 1.1 billion urban residents lived in slums or informal settlements in 2020, with 2 billion more projected over the next 30 years (see Figure 4). The predominance of informal work and housing poses a challenge for municipal finance, limiting the tax base for local governments and their scope to offer social protection.

Figure 4: Share of the urban population living in slums, by region, 2020

Source: United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division (2019). World urbanization prospects: The 2018 revision.

3.5 Promoting good governance in cities is essential to ensuring that the benefits of urbanisation are realised. Governance arrangements in cities are often complex, involving both national and municipal authorities, and influenced by diverse historical, cultural and political factors. Common constraints to effective multi-level governance include unclear distribution of responsibilities, weak cooperation and limited political power at local government level. All these can impede the adoption and implementation of inclusive urban policies.

3.6 Rapidly urbanising cities are vulnerable to climate change. Unplanned or unmanaged urbanisation can result in urban sprawl, leading to irreversible land-use changes and biodiversity loss. This threat is particularly acute in low-income countries, where city land area will expand fastest (by 141%) over the next five decades, as compared to lower-middle-income (44%) and high-income countries (34%). Urban infrastructure, including transport, water, sanitation and energy, is also at risk from extreme and slow-onset climate events, resulting in economic losses, disruptions to services, and costs to human health and welfare. About 70% of African cities are highly vulnerable to climate shocks, with small and medium-sized towns and cities most at risk. More than a billion people in low-lying cities and settlements will be at risk from sea-water incursion and other coastal-specific hazards by 2050. Climate impacts tend to fall hardest on economically and socially marginalised urban residents, including those living in informal settlements.

Global aid for sustainable cities

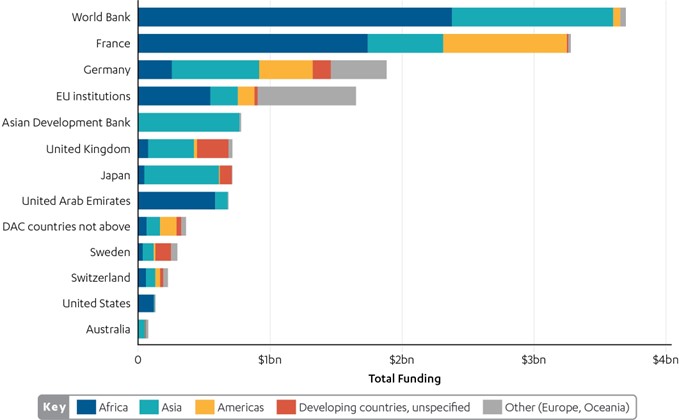

3.7 International aid and cooperation can play a useful role in helping developing countries to achieve Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 11. They contribute to poverty reduction, service delivery and community empowerment. According to the literature, successful aid programmes can help by addressing the constraints of limited data and information technology, improving access to financial and human resources, and promoting coordination across governments and agencies. Direct interventions for ‘slum upgrading’, including housing, infrastructure, and health services, have provided environmental and social benefits for the urban poor. International aid organisations have increasingly used climate finance to support urban development and enhance cities’ capacities for mitigation and adaptation. Most of the largest donors for sustainable cities are multilaterals, including the World Bank, the EU and the Asian Development Bank (see Figure 5). The UK is the sixth-largest donor for urban development.

Figure 5: Global spending on sustainable cities 2015-2022 (Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development aid data)

Source: OECD aid data, supplemented with data from BII investment commitments

UK aid’s approach to sustainable cities

3.8 While the UK has long recognised the importance of urbanisation in the development process, the former Department for International Development’s (DFID) 2015 Sustainable cities for growth policy framework explicitly articulated the department’s increased emphasis on cities as drivers of growth and economic transformation, while also recognising their central role in the shift towards low-carbon development. The document noted that rapid urbanisation was not leading to many of the expected benefits, such as economic transformation, regional and national growth and employment, particularly in Africa. It therefore set out a framework to guide both programming and influencing activities, and to feed into the development of what would become DFID’s 2017 economic development strategy.

Box 3: DFID’s Sustainable cities for growth policy framework

DFID’s 2015 framework for urban development aimed to foster economic growth and create more and better jobs, in ways that were inclusive and poverty-focused, and that targeted sustainability and resilience. It identified five areas where DFID could support sustainable urban development:

- Planning: spatial planning, land use, property rights and resilient infrastructure

- Finance: mobilising public and private finance for urban infrastructure

- Growth: in investment, the business sector, inclusive growth and job creation

- Knowledge: including evidence and improved metrics of ‘what works’

- Leadership: supporting debates and partnerships on cities internationally

Despite reaching an advanced stage of development, the framework was never published. However, it fed into what would become DFID’s 2017 economic development strategy and has continued to frame the UK’s increasingly cross-sectoral approach to urban development. Although the framework was focused on economic growth, it included several cross-cutting issues, such as rural-urban linkages, conflict and fragility, women and girls, and sustainability.

3.9 The framing of cities as a key climate priority was further emphasised in the 2023 International climate finance strategy, which placed sustainable cities at the core of the UK’s global efforts to address climate change (see Box 4). This is elaborated further in an unpublished 2023 Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO) policy briefing, Sustainable cities policy priorities, which highlights the cross-cutting nature of urban programming and states that future approaches must be “informed by analysis of the local political economy and engagement with the shadow economy to determine what is politically feasible and ensure that the poor benefit”.

Box 4: Sustainable cities in the UK’s International climate finance strategy

In March 2023, the UK published its International climate finance strategy (ICF 3). The strategy covers the UK’s pledged £11.6 billion of funding over the period 2021-22 to 2025-26 for achieving outcomes in climate mitigation and adaptation, biodiversity and poverty reduction. One of the four themes of focus is Sustainable Cities, Infrastructure and Transport. Under this theme, the UK commits to supporting SDG 11 through green, resilient and inclusive urban development that makes use of nature-based infrastructure, avoids emissions, and works to reduce cities’ environmental footprint. According to ICF 3, work on this theme will be delivered through investment, research and by supporting cities with their environmental governance and planning. It is notable that ICF 3 – a climate strategy – is the UK’s first published statement of intent on sustainable cities. However, it contains only limited detail about non-climate aspects of supporting cities, such as employment, housing, data and technology, municipal finance and governance.

3.10 Sustainable cities have recently risen in profile through British Investment Partnerships (BIP) – a cross-government initiative introduced in The UK government’s strategy for international development to mobilise UK expertise on investment finance for development (see Box 5). Bringing together several UK departments, investments made through BIP will contribute to the $600 billion G7 Partnership for Global Infrastructure and Investment.

Box 5: Sustainable cities in British Investment Partnerships

The primary objective of British Investment Partnerships (BIP) is to link technical assistance and investment by developing bespoke investment packages to meet the needs of partner countries using three levers:

- Finance – BIP mobilises finance through capital markets, multilaterals, export and trade, and development finance. In the context of sustainable cities, this includes building on previous investments and strategies of British International Investment (BII), formerly CDC Group, and the Private Infrastructure Development Group (PIDG):

- British International Investment: As the UK’s development finance institution, BII is a major component of the BIP initiative. BII’s strategic development impact objectives are set out in five-year strategies, with the most recent 2022-26 strategy integrating sustainable cities in two of BII’s focus sectors: i) infrastructure and climate and ii) construction and real estate. In addition to its five-year strategy, several cross-cutting policies frame BII’s investment approach in support of sustainable cities, including the 2020 climate change strategy which positions “safe and resilient cities” as one of BII’s development objectives for climate-focused investments.

- Private Infrastructure Development Group: Established in 2002, PIDG is an infrastructure development and finance organisation funded by six governments, including the UK, as well as the International Finance Corporation. Focusing on frontier markets in sub-Saharan Africa and South and South-East Asia, PIDG aims to mobilise private sector finance to support climate-resilient infrastructure. PIDG operates through three business lines: i) technical assistance and project preparation; ii) project development; and iii) credit solutions. The 2023-30 strategy highlights sustainable and resilient cities and circular economy as one of PIDG’s focus investment sectors, including work in transport, water, waste management and affordable housing.

- Partnerships – BIP’s approach to partnerships includes leveraging the UK’s existing network with country governments, international finance institutions, and multilateral organisations.

- Expertise and research – In addition to ongoing research programmes, BIP consolidates UK expertise through five Centres of Expertise: i) Green Cities and Infrastructure; ii) Public Finance; iii) Financial Services; iv) Green and Inclusive Growth; and v) Trade.

3.11 Announced in the 2022 international development strategy, the Centres of Expertise (CoEs) have been endorsed by ministers as a new way to deliver technical assistance (see Figure 6). The Green Cities and Infrastructure CoE brings together some of the existing centrally managed programmes focused on urban development. It has two primary objectives: i) to serve as a central hub for country teams to access technical expertise on urban development; and ii) to coordinate the UK’s international offer on cities and infrastructure, drawing from a range of government departments, including the Department for Business and Trade (DBT), the Department for Energy Security and Net Zero (DESNZ), the Department for Science, Innovation and Technology (DSIT) and public agencies (Crossrail, TfL and others).

3.12 The 2023 White paper on international development further affirms CoEs as a one-stop-shop for international partners to access cross-department specialist expertise, including UK expertise in urban planning and project development to “create infrastructure services that are resilient and sustainable (SDG 11) and help cities realise their potential to drive growth and create jobs”. The white paper also notes that PIDG and the Green Cities and Infrastructure CoE will serve as a channel for providing project development support to develop a “pipeline of bankable projects” and mobilising private capital. The FCDO Resilient Cities and Infrastructure Team serves as the Secretariat for the Green Cities and Infrastructure CoE and is the primary point of contact for international engagement.

Figure 6: Timeline of relevant UK strategies, policies and publications

The UK sustainable cities aid portfolio

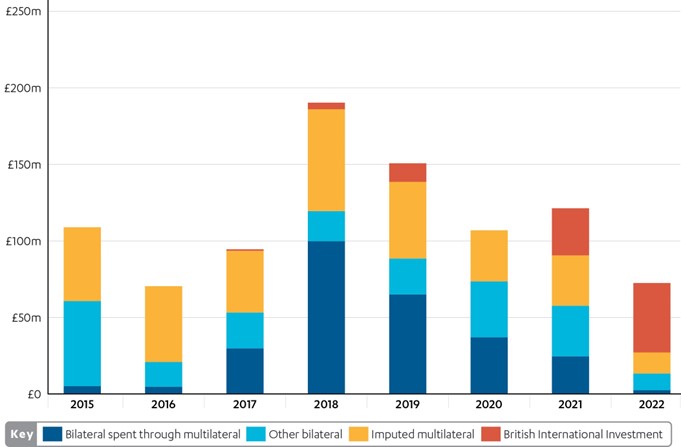

3.13 Between 2015 and 2022, the UK has reportedly spent a total of £916.6 million on urban development, through multi-bi funding (29%), other bilateral funding (24%), its core contributions to multilateral development agencies (37%), and BII (10%). However, during this period, the UK’s annual spending on urban development fell sharply, from £190.5 million in 2018 to just £72.6 million in 2022.

3.14 FCDO is responsible for the largest share of UK aid for sustainable cities. However, several other departments and development finance instruments also contribute (see Figure 7), using a range of aid modalities and channels. The main spending departments have been DFID/FCDO, which spent £318.2 million, followed by the former Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy (BEIS), which spent £141 million, and the cross-government Prosperity Fund, which spent £23.4 million. The Department for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities (DLUHC) supports engagement on cities through the G7 and G20 fora, although it does not have any active programming.

Figure 7: Spread of sub-themes covered by UK departments and instruments

3.15 Most of the UK’s bilateral aid for sustainable cities has focused on Asia (48%), compared to 11% in Africa, although a significant share of its spend is not classified by country (34%). Where a breakdown is available, £81.8 million went to low-income countries, £92.6 million to lower-middle-income countries and £72.1 million to upper-middle-income countries.

3.16 However, UK aid for sustainable cities is not well captured in the statistics, and there are discrepancies in different published sources. For example, the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) Creditor Reporting System (CRS) reported that the UK spent the smaller amount of £582.4 million between 2015 and 2022. In many instances, support for sustainable cities is an indirect result of programmes targeting other sectors, such as transport or energy.

Figure 8: UK official development assistance spending on sustainable cities, by modality

3.17 We identified 214 programmes that contributed to sustainable cities to varying degrees during the review period. We categorised these into three groups: those focused on cities, those with some reference to cities, and those where cities are a minor component. We found that 102 programmes or projects are focused on cities, including 44 FCDO programmes, 34 DSIT-funded programmes and projects, one Defra programme, 14 PIDG and nine BII investments. Using this method, we found that the UK had spent at least £1.3 billion on sustainable cities, with an additional £365.5 million in sectors with partial or limited reference to cities. This categorisation was further applied to evaluate the performance of programmes identified as contributing to the sustainable cities portfolio. However, missing or incomplete data were also found in the collection and publication of performance metrics across programmes. Our analysis of current programmes revealed that out of a total of 39 programmes, only 21 had annual reporting available for 2022. From this sample, only one programme had an overall annual review score below A, and one-third of programmes scored either A+ or A++. At the output level, scores for individual programme components were more varied. While the majority of the programmes’ components scored either an A (43%) or A+ rating (35%), there was a significant minority (12%) that scored B or C. The majority of the 84 programme activities were focused on governance and finance, with poverty reduction featuring the least at the output level.

4. Findings

Relevance: Does the UK have a clear and credible approach to promoting sustainable cities that aligns with its broader objectives?

4.1 In this section we examine the relevance of UK aid for sustainable cities, including the extent to which the UK’s urban development programmes contribute to UK objectives, meet countries’ needs and address cities’ most pressing concerns.

While there are individually relevant activities, there is no clear overall purpose for the sustainable cities portfolio, creating uncertainty over direction and leaving gaps

4.2 The UK’s support for sustainable cities includes a broad range of programmes focused on urban planning, infrastructure, transport, economic growth and urban climate resilience. UN Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 11 (see Box 1) provides a framework for assessing the relevance of UK support for sustainable cities. Our analysis of programme business cases and theories of change confirms that the UK’s official development assistance (ODA) portfolio on sustainable cities was broadly aligned with SDG 11’s sub-goals over our review period. However, officials we interviewed and urban experts who participated in roundtable discussions for this review have noted that there remains a lack of clarity over the UK’s rationale and approach for working on cities.

4.3 A 2018 Independent Commission for Aid Impact (ICAI) review of the former Department for International Development (DFID)’s transport and urban infrastructure programmes found that the UK was achieving impact through its support for urban infrastructure. In 2018, DFID identified urban infrastructure as an area where it would like to build up its portfolio. In practice, however, the UK moved away from urban infrastructure towards programming in other areas, such as urban planning (including transport), economic growth, finance and climate. This broadening of approach brought with it some issues. Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO) delivery partners as well as UK officials have noted that there have been challenges to framing development through a distinctly ‘urban’ lens, and whether to address sectoral issues at a purely national level, or as a component of urban programming.

4.4 The UK’s urban development programmes have generally reflected its areas of comparative advantage. For example, the UK possesses expertise in city governance and urban planning, and programming has reflected this. However, there are areas of comparative advantage and perceived strategic interest that are not reflected in the urban portfolio. The 2022 international development strategy and 2023 White paper on international development set out UK ambitions to use its financial expertise and the City of London to mobilise investment for green infrastructure. However, in our meetings with UK officials and experts, we heard that for the urban portfolio, in most cases, relatively little has been done on this.

4.5 There is recognition within FCDO of a need for clearer guidance to structure programming choices in the urban portfolio. In 2015, DFID developed a Sustainable cities for growth policy framework, which outlined the department’s approach to promoting growth in sustainable cities through its urban development and economic growth programmes (see Box 3). As an internal DFID document, the framework had less relevance for other departments’ urban development work and has had limited impact, although some programmes designed after the framework have gone on to be influential. FCDO produced The urban handbook for sub-Saharan Africa in 2019, and an internal insights document in 2022, to provide examples drawn from experience and current evidence, aimed at FCDO officials designing urban interventions. While useful for drawing together evidence on ‘what works’ in urban development programmes, these documents do not provide a clear framework to guide programming. They are also of limited relevance to non-FCDO staff. While FCDO infrastructure and urban advisers can offer this knowledge to teams in-country on a demand-led basis, we are not aware that these documents have been shared with other departments or widely across FCDO.

4.6 Interviews with FCDO staff revealed a lack of consensus on the UK’s approach to sustainable cities, including its comparative advantage and objectives. Without a shared approach across FCDO and other departments, it is difficult for officials to design programmes that reflect the UK’s aims and commitments. As a consequence, the portfolio has become very broad, touching on a wide range of areas and objectives, without clear criteria for allocating resources. While the 2023 International climate finance strategy (ICF 3) describes in broad terms how UK climate finance will work to improve the environmental sustainability of cities, it is not specific about how this is to be achieved, nor does it provide a clear rationale for investing in urban development more generally. In particular, the focus on cities as an engine of economic growth and development, which was central to the 2015 DFID framework, is not well understood outside the urban team in FCDO, and is no longer central to the portfolio.

The UK’s urban programmes have made efforts to align with local and national priorities, and to incorporate local stakeholder perspectives in project designs

4.7 The UK made efforts to engage with policymakers and civil society at both national and city levels. For example, FCDO staff and external partners emphasised the importance of engaging and empowering city-level authorities, noting that city administrations are often ‘first responders’ and therefore best placed to understand the complex issues facing urban residents. This is confirmed in our literature review, which notes the importance of strong city-level governance, which can result in policies that are better rooted in the needs of urban communities. UK programmes have also funded cities’ networks and partnerships involving think tanks, research institutions, international organisations, and other stakeholders such as Cities Alliance, Coalition for Urban Transitions, and C40. This has allowed programmes to engage with a wide range of actors, strengthening both government and nongovernmental networks.

4.8 Several programmes demonstrated well-thought-out approaches to incorporating the views of local stakeholders. Through the UK’s support to Bangladesh’s National Urban Poverty Reduction Programme (NUPRP), community-based organisations were supported to advocate for their rights and hold local governments to account. This programme’s design was cited as ‘unique’ by FCDO and UN Development Programme (UNDP) officials, as well as in an external evaluation, due to its use of participatory studies and community platforms. The Asian Development Bank’s (ADB) Urban Climate Change Resilience Trust Fund (UCCRTF), the major share of which was financed by the UK through the Managing Climate Risks for the Urban Poor (MCRUP) programme, was designed to include community participation in the design of interventions. This approach was new to ADB when it was introduced to the UCCRTF. It has been one of the more successful elements of the programme, and has gone on to increase community leadership and local relevance in other programming in ADB.

“From the time we were told that there was going to be construction in our street…there was a meeting with the residents’ associations, where we were all involved.”

Woman resident, Makassar, Indonesia

4.9 In our country case studies, we found that UK aid to sustainable cities was broadly aligned with government priorities in Indonesia and South Africa. South African stakeholders consistently highlighted the positive and constructive engagement of the British High Commission in Pretoria. Urban programmes in Indonesia also appeared to reflect local priorities and key issues and encouraged the use of national expertise. However, we saw limited evidence that programme and thematic selection were underpinned by analysis of ‘what works’ or a comparison of options for impact. It was clear, nevertheless, that efforts had been made to reflect the priorities of the Indonesian government. Indonesian officials told us that they were committed to the electrification of municipal transport, and that UK programming had been helpful in this regard.

4.10 The UK’s aid-funded research on cities in the Global South has highlighted the importance of conducting research at the subnational level, driven by researchers in the region, to explore and help relieve constraints facing cities. The FCDO-funded Africa Cities Research Consortium is a positive example. It is African-led by design, where local actors, including African researchers, civil society, local and national politicians, municipal employees and other actors key to reform are centrally involved in the design of the programme. However, we found instances of research which did not involve equitable partnerships with researchers from the Global South. Consultations with researchers, experts and other multilateral partners revealed that overall, the UK performed less well than other donors in involving researchers from developing countries, particularly from Africa. The Global Challenges Research Fund (GCRF)-funded Centre for Sustainable, Healthy and Learning Cities and Neighbourhoods is one example, where the majority of the Centre’s funding, its design, and the priorities identified were predetermined and concentrated centrally in the UK, not locally.

4.11 Our citizen engagement exercise in Indonesia and South Africa found that the UK had a mixed performance in integrating local stakeholder perspectives in the inception and delivery stages of urban programmes. As a result, some areas of programming did not align with local stakeholder priorities. In Indonesia, we found that while citizens understood the climate relevance of the transport electrification programme delivered by UK Partnering for Accelerated Climate Transitions (UK PACT), the programme inadequately addressed the needs of some public transport users and had unintended consequences, and the rationale for electrification had not been fully explained.

“Electric buses cannot operate like diesel buses because their battery power is limited. Diesel buses can operate from 1 pm to 11 pm. If we drive an electric bus, at 7 o’clock we have to go home, and we lose four hours of work, so our earnings decrease.”

Bus driver, Jakarta, Indonesia

“This plan is to be implemented without citizens’ understanding it… What needs to be addressed is how to give people more information about it so they can understand.”

Public transport user, Jakarta, Indonesia

4.12 In South Africa, we heard in our citizen engagement that some local residents felt they had not been adequately consulted during the planning stages of a project funded under the Global Future Cities Programme (GFCP), with community engagement delivered by a Cape Town-based non-governmental organisation (NGO). These residents felt that their involvement in the planning process came at too late a stage and at a point where their consultation was not able to positively affect project outcomes. A British International Investment (BII) investment in Johannesburg had provided good-quality accommodation for working-class South Africans, but residents told us that there were significant issues about the affordability of the units, and questioned whether this investment was relevant for the lower strata of the urban working class.

“The rent is too high, and we pay up to R4,200 [approximately £180 per month] for a bachelor unit.”

Resident of a BII-backed provider of urban housing and regeneration projects, Johannesburg, South Africa

The UK has missed opportunities to leverage its expertise in affordable housing

4.13 Access to safe and affordable housing is the first of SDG 11’s sub-goals and, according to a recent UN progress report on the SDGs, in 2020 an estimated 1.1 billion urban residents lived in slums or slum-like conditions. Over the next 30 years it is expected that there will be an additional two billion people joining them. Between 2002 and 2019, FCDO (as DFID) consistently supported housing-related projects. FCDO officials have acknowledged that they do not have a model of how to deliver housing projects that successfully combine private finance and affordability. During our review period, FCDO decided to move away from safe and affordable housing in its bilateral aid portfolio, choosing to address housing through non-grant mechanisms (see para 4.11).

4.14 Our literature review and expert workshops confirmed that affordable housing is a critical aspect of inclusiveness in urban settings which, given the necessity of decent housing and the issue of informality in cities in the Global South, warrants inclusion in urban aid programmes. FCDO noted that expertise for housing finance is now located in BII and the Private Infrastructure Development Group (PIDG). Since the department was constrained by resources, it decided to pass the lead for supporting affordable housing to these organisations. In its construction and real estate strategy, BII refers to investing in social infrastructure such as housing, while PIDG in 2018 developed impact guidelines for affordable housing. However, officials told us that commercial investment in housing requires mortgages or rents that are not viable for some low-income households, while non-commercial housing models (such as housing associations and cooperatives) that could benefit them were not commercially viable. In principle, PIDG would consider mixed models with sub-commercial elements, but specifically exclude housing investments for the 20% lowest-income households. We found in our programme desk reviews and interviews with citizens in South Africa that, consistent with these views, where BII and PIDG had been able to lend to commercial property developers for housing, this had been without a clear plan for targeting those on incomes below levels usually acceptable to commercial providers. UK officials acknowledge that the lack of attention to housing is a gap, and we were shown that affordable housing and shelter are not referenced in the recent white paper.

Although the focus on climate change has increased, attention to adaptation has until recently been low and nature-based solutions have not been put into practice

4.15 Early UK strategic documents and programme designs did not have a strong climate or low-carbon development emphasis. Although the 2015 Sustainable cities for growth framework paper does refer to “climate-smart” and resilient infrastructure programming, it does not outline a focused approach towards climate change or low-carbon development. Around 2015, DFID urban programmes addressed climate through the lens of urban resilience. A mapping exercise undertaken by the review team confirms that, since 2015, there has been a shift in the portfolio towards a greater focus on urban climate, including climate risk management, climate resilience, and decarbonisation of infrastructure such as sustainable transport and renewable energy.

4.16 Although it is well understood that both adaptation and mitigation efforts should be addressed in urban programmes to maximise climate effectiveness, there has been a greater focus on mitigation in the UK’s urban portfolio. Indeed, ICAI has found that across the UK’s international climate finance (ICF), the UK is falling behind on its adaptation commitments. We note that the urban development programmes designed by the former Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy (BEIS) focused almost exclusively on mitigation, in line with BEIS’s ICF investment mandate. We observed in both our country case studies that the majority of the UK’s urban development portfolios in those countries set climate change objectives primarily for mitigation. Both our case studies are of middle-income countries with large coal-fired power sectors, and a case study of a low-income country might have included more significant adaptation activities. However, an ICAI mapping of the UK portfolio shows a greater focus on mitigation in the urban portfolio overall, which was also reflected in interviews with urban experts. While one of the BII investments we reviewed had adopted the Excellence in Design for Greater Efficiencies (EDGE) certification, which aims to reduce resource intensity (energy, water and carbon) in buildings, the BII and PIDG investments we reviewed did not include specific measures to address or report on adaptation. Our literature review finds that many urban plans are missing opportunities to advance the co-benefits of climate action and sustainable development, and this has a potential effect of compounding inequality and reducing well-being. This finding has also been documented in UK programmes.

4.17 Resilience building and climate adaptation in urban areas is often also a good pro-poor investment. For instance, housing-related adaptation measures and developing urban heat action plans are effective climate and pro-poor solutions, since the urban poor are disproportionately likely to live in poorly adapted housing and to work outside during the warmest periods of the day. The portfolio’s lack of focus on adaptation risks missed opportunities to capture the co-benefits of poverty reduction and increased climate resilience. Indeed, work by the Coalition for Urban Transitions, under the Infrastructure and Cities for Economic Development (ICED) programme, identified a need for urban programmes to pay greater attention to adaptation, to ensure they are pursuing mitigation, adaptation and development goals in tandem. Climate vulnerability and the relative costs of adaptation are becoming an increasingly urbanised problem, and investing in climate adaptation programming in urban settings often represents good value for money by both targeting the urban poor and addressing climate. Towards the end of our review period, we saw greater efforts by the UK to increase climate adaptation and resilience relevance across the portfolio. For instance, the Urban Climate Action Programme (UCAP), launched in 2022, was a successor to the Climate Leadership in Cities (CLIC) programme, but with an added focus on climate resilience and adaptation.

4.18 While the UK has supported the development of nature-based solution (NBS) pilots, these have been small-scale and have not yet generated transferable lessons. Our literature review finds that NBS offer an important opportunity to address environmental, social and economic objectives. In strategic documents and from UK officials, we see increasing interest in potential nature co-benefits for green urbanisation. The UK’s 2023 ICF strategy includes a commitment to increase investment in nature-based infrastructure. The recent white paper also confirms that NBS is an area in which the UK wishes to build capacity.

4.19 In the current urban portfolio, however, NBS are underserved. Although there are individual projects within larger programmes featuring NBS, there are few programmes in the portfolio that feature NBS prominently. The Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs’ (Defra) Cities4Forests (C4F) programme is one exception, featuring projects that focus on the delivery and financing of NBS, but we understand that a decision has been made not to continue funding for a next phase. Our country case studies featured examples of using NBS in urban development programming (such as the Diep River system in Cape Town, under UCAP and the Revitalisation of Informal Settlements and their Environments (RISE) project in Makassar under MCRUP – see Box 7). However, these examples were the exception. Senior staff at FCDO are aware that they have not prioritised NBS in the urban development portfolio, and have informed ICAI that progress on NBS has been to date constrained by availability of finance for NBS, limited evidence of impact and therefore value, and low FCDO capacity, given a lack of climate expertise among urban advisers. However, recent ICAI reviews have found that, in the period during which the UK co-chaired COP 26, FCDO considerably increased its climate staff positions, which created an opportunity for building climate capability across the department. We also heard from a head of profession that climate and environment experts are readily available to provide advice and support to the infrastructure and urban cadre when needed. Lack of expertise does not therefore appear to be a credible explanation for the low penetration of NBS through the urban portfolio.

Some UK sustainable cities programmes lacked credible links to poverty reduction, inclusion and engagement with the informal economy

4.20 While DFID’s approach to urban development was historically focused on poverty reduction, over time, the emphasis of the UK’s urban portfolio shifted towards programmes focusing on cities as engines for increasing productivity and creating jobs, and towards programming in middle-income countries. In 2015, at the start of our review period, the sustainable cities portfolio was mostly focused on delivering programmes in South Asia. DFID India was the single biggest spender, at 40% of the portfolio, with an emphasis on informal settlement improvement projects. Over time, the geographical focus changed, with an increasing number of programmes focusing on megacities in middle-income countries, including prosperity-focused programmes delivered by the former Foreign and Commonwealth Office (FCO), climate mitigation programmes by the former BEIS, and development finance investments by BII.

4.21 While many of the UK’s urban development programmes have worked to address key constraints facing vulnerable groups, there are several examples of programmes in the portfolio that do not adequately address inclusion and the informal sector. The MCRUP and NUPRP programmes are good examples of programmes that recognised vulnerable populations and inclusive growth. We saw several programmes in Indonesia that made efforts to include disabled transport users in their interventions. By contrast, the CLIC programme, for example, did not have a strong focus on inclusion, and cities’ climate action plans developed through the programme only met minimum requirements. The ICED programme sought to address inclusion through the generation of guidance, training and technical assistance. However, as acknowledged in its programme completion report, it is difficult to assess the result of this knowledge sharing as monitoring and evaluation systems did not effectively measure uptake and downstream impact. More generally, a lack of common metrics has made such measurements difficult across the portfolio as a whole. Experts in our stakeholder workshops told us that, despite the importance of the informal sector in many cities in developing countries, not enough is being done to incorporate the informal sector into programme designs more explicitly.

4.22 While the need to pursue minimum financial returns can make it more difficult to target inclusion through development finance, the UK’s urban investments address inclusion only narrowly, and in some cases are not adequately ensuring that they meet the inclusion goals they have set for themselves. In Kenya, we saw that an investment funded by PIDG had made efforts to focus on gender, evidenced by its commitment to gender equality in identifying the people it aimed to benefit and in its employment policies. However, we saw no information regarding how gender was addressed in combination with other characteristics that could result in disadvantage or discrimination either across its investment more generally or within its existing gender equality initiatives. BII’s investment in a provider of urban housing and regeneration projects in South Africa was designed to address gender by having 50% female ‘primary tenants’ in its properties. However, the team found that prior to BII’s investment, female tenancy was already at 47%, indicating only modest incremental impact as a result of BII’s investment, although the provision of a subsidised day care centre at one of the buildings did offer working mothers an affordable child care option. Nor did we find evidence signalling the investment’s prioritisation of links to other facets of inclusion, including disability. The development impact score for the investment – which measures an investment’s contribution to BII’s key strategic goals relating to productivity, sustainability and inclusiveness and is one of BII’s key performance indicators – was 1.02 out of 4 at the time of investing (2021). This is significantly below the aggregate development impact score of 2.84 for the 2019-21 period.

4.23 Over time, programmes were increasingly based on theories of change that made assumptions about indirect poverty reduction channels, which often do not articulate how such investments will result in pro-poor benefits. Generally, programmes from earlier in our review period were better able to show direct and credible pathways to reducing urban poverty. NUPRP, for instance, was based on long-term UK engagement on urban poverty reduction in Bangladesh and addressed key challenges identified in poverty reduction and inclusive growth diagnostic studies. It also placed a focus on communities at climate risk – acknowledging that addressing both urban poverty and climate vulnerability has the potential to be transformational. Since around 2017, an increasing focus has been placed on indirect poverty reduction channels, including technical support to national and municipal governments on planning and capacity building, with increasingly less emphasis on direct ‘pro-poor’ interventions.

4.24 Some of this shift was caused by the change in the nature of the UK’s development partnership with India, with a shift away from ‘traditional’ aid programmes towards enhanced technical assistance and capacity building, reflecting India’s changing needs as a middle-income country. These later programmes were expected to result in improved delivery of services or finances, with the assumption that these would benefit the poorest and most marginalised. Our analysis of these and similar programmes across the portfolio reveals that the evidence for these pathways is often contested, and can be based on assumptions derived from higher-income country experience that do not hold when replicated. Elsewhere, we heard that urban development programmes are often based on the assumption that such investments lead to the creation of new jobs and integration of people into the urban system. However, experts in our stakeholder roundtables noted that there was often a mismatch between the skills of many individuals and the opportunities available in urban labour markets.

4.25 UK technical assistance for sustainable cities in middle-income countries continues to be provided as a grant despite the greater capacity of recipients to fund this assistance themselves, relative to those in low-income countries. This is particularly the case in more decentralised countries where municipal budgets tend to be higher. For example, the budget of the city of Cape Town, which we visited as part of our case study of UK aid for sustainable cities in South Africa, amounted to approximately £3 billion in 2023-24, easily able to accommodate the relatively modest cost of UK technical assistance to the city. While the provision of climate finance support, including to middle-income countries, is consistent with meeting UK obligations under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), several stakeholders pointed out that some cities in middle-income countries are better able to pay for technical assistance than in low-income countries. Moreover, they also benefit from access to UK networks, expertise and momentum that comes with UK support.

The UK has had a long-stated intention to extend its support beyond primary cities to secondary cities, but has made little progress