UK aid for trade

Score summary

The UK is not doing enough to ensure that its aid for trade interventions benefit the poor, and the increased focus on short-term UK interests poses risks to the quality of programming that are not being sufficiently managed

Overall, we find the UK’s approach to aid for trade broadly reflects the priorities of partner countries and the evidence on ‘what works’ in increasing trade and promoting economic growth. However, the government is not paying sufficient attention to ensuring that trade contributes to poverty reduction and benefits the poor. There are also risks that the pursuit of secondary benefits to the UK may compromise the quality of programming, and the focus on poverty reduction. In addition, the recent aid budget reductions have had detrimental effects on the UK’s reputation and influence among partners.

Nevertheless, there are areas of strength within the portfolio. The UK’s support has contributed to positive results, including delivering significant reductions in the time to trade across borders and contributing to increases in trade, although who benefits is less clear. Overall, the UK made significant progress in delivering its intended results in the period before the aid budget reductions. However, the effectiveness of UK aid for trade is now at considerable risk due to these reductions, which have left a portfolio that is more fragmented and less focused on delivering benefits for the poor.

While there are systemic challenges in assessing the wider impacts of many aid for trade programmes, given the length of time for results to materialise and the long and complex results chains, efforts to address these challenges are lacking and have deteriorated further as a result of the aid reductions.

| Individual question scores | |

|---|---|

| Relevance: Does the UK have a clear and coherent approach to aid for trade? |  |

| Effectiveness: To what extent has the UK achieved its aid for trade objectives? |  |

| Learning: How has the UK used learning from ongoing aid for trade interventions to evolve its approach to design and delivery? |  |

Acronyms

| Acronym | Definition |

|---|---|

| ACCELERATE | Accelerating Ethiopia’s economic transformation |

| AFTR | Africa Food Trade and Resilience |

| AGOA | African Growth and Opportunities Act |

| ARTCP | Asia Regional Trade and Connectivity Programme |

| BII | British International Investment (formerly CDC Group) |

| DFID | Department for International Development (merged with the Foreign and Commonwealth Office in September 2020) |

| EIAF | Ethiopia Investment and Advisory Facility |

| FCDO | Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office |

| FCO | Foreign and Commonwealth Office (merged with the Department for International Development in September 2020) |

| FTESA | FoodTrade East and Southern Africa |

| GATF | Global Alliance on Trade Facilitation |

| GCRF | Global Challenges Research Fund |

| GG | Growth Gateway |

| GTP | Global Trade Programme |

| HMRC | HM Revenue and Customs |

| ICAI | Independent Commission for Aid Impact |

| ODA | Official development assistance |

| OECD | Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development |

| SARTIP | South Asia Regional Trade and Integration Programme |

| SDG | Sustainable Development Goals |

| SITFA | Support for the Implementation of the World Trade Organisation Trade Facilitation Agreement |

| STDF | Standards Trade and Development Facility |

| TAF | Trade Advocacy Fund |

| TAF2+ | Trade and Investment Advocacy Fund |

| TC | Trade Connect |

| TFA | Trade Facilitation Agreement |

| TFAF | Trade Facilitation Agreement Facility |

| TFD | Trade for Development |

| TFMICs | Trade Facilitation in Middle-Income Countries |

| TFSA | Trade Forward Southern Africa |

| TFSP | Trade Facilitation Support Programme |

| TMEA | TradeMark East Africa |

| UKTP | UK Trade Partnerships |

| WEF | World Economic Forum |

| WTO | World Trade Organisation |

Executive summary

Over the last 50 years, the steady rise in international trade has been a major driver of economic growth in many parts of the world, especially in Asia. However, the poorest countries are least likely to benefit from the trading opportunities; together, they account for just 1% of global exports. They face a range of constraints on their ability to trade, including poor infrastructure, high transportation costs and cumbersome border procedures. Enterprises in poorer countries also often lack the ability to produce goods of the required quantity and quality for international markets. Furthermore, the opportunities for trade-related development have been heavily disrupted in recent years, including by trade tensions between the US and China, the COVID-19 pandemic and the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

‘Aid for trade’ is an area of development assistance that helps countries expand their trade. This review assesses how well the UK’s aid for trade supports economic growth and poverty reduction. It examines the relevance of the UK’s support since 2015 and its effectiveness in tackling constraints on trade and promoting inclusive economic growth. It also examines how well the UK has assessed the impact of aid for trade on poverty reduction and the poor.

Relevance: Does the UK have a clear and coherent approach to aid for trade?

Since 2015, trade has become increasingly prominent in UK development policies and strategies. As well as recognising trade’s potential to act as an engine of economic growth, the UK has prioritised building trade ties with developing countries, particularly since its departure from the European Union, in order to promote mutual prosperity. Mutual prosperity objectives include both poverty reduction in recipient countries and benefits for the UK (called secondary benefits) through mutually beneficial economic relationships (see paragraph 1.4).

Through its aid for trade programming, the UK is helping developing countries to increase their trade through interventions that improve market access, reduce the time and cost of trading across borders, and build the capacity of firms to export. The UK is also helping to strengthen the international rules-based system (particularly the World Trade Organisation (WTO), which deals with the rules of trade between countries) underpinning global trade and economic integration. The UK’s approach is relevant and credible, broadly reflecting the priorities of partner countries and the evidence on ‘what works’ in increasing trade and promoting economic growth.

However, whether increases in trade result in benefits for poor people in developing countries depends on other factors, such as the ability of smaller enterprises to produce goods of export quality and the ability to benefit from job opportunities created. The literature shows that additional measures are often required to ensure inclusive results, such as support to small businesses and farmers. We find that many UK programmes are not paying enough attention to whether these measures are in place. Also, while the portfolio has a good level of focus on women, there is less emphasis on inclusion of other marginalised groups (for example, people living with disabilities and youth), particularly since the aid budget reductions.

The creation of the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO) and the increased focus on cross-government working have opened up possibilities for a more integrated approach to aid for trade across government. These developments have encouraged aid officials to explore how to make better use of tools, such as economic diplomacy, to deliver results. However, cross-government coordination and collaboration remain a work in progress and the government has only partially taken advantage of the opportunities this creates. We also found insufficient coordination and collaboration between programmes that have the potential to complement each other. This includes coordination between centrally managed and bilateral UK aid for trade programmes, between UK aid for trade and wider economic development programmes, and between programmes funded by the UK and by other donors, reducing the potential combined impact of programmes.

Up until 2019, we found limited evidence of UK aid for trade programmes being designed specifically to deliver secondary benefits to the UK. References to secondary benefits often appeared to be included in programme design documents to secure internal approval, rather than being integral to their design. However, since 2019, there are signs of an increased emphasis on secondary benefits to the UK in the design of new programmes. These programmes also work primarily with established enterprises in more developed markets, suggesting a shift away from interventions that benefit the poor. In addition, the UK has also shifted its geographical focus in Africa to larger economies, such as Ghana, Kenya, Nigeria and South Africa, where its potential trading opportunities are stronger. While there is poverty in these countries, poverty levels are greater in other countries in sub-Saharan Africa where FCDO, and the former Department for International Development, traditionally provided more support. Aid for trade programmes can legitimately deliver economic benefits for both the UK and developing countries, but we found a lack of detailed guidelines on how to incorporate secondary benefits without compromising the primary purpose of UK overseas development assistance, which is poverty reduction.

The recent aid budget reductions, and the way these were managed, have had detrimental effects on the UK’s relationships, reputation and influence among partners. These budget reductions have also led to a portfolio thinly spread across programmes, themes and countries. In addition, the UK has significantly reduced its support to institutions such as the WTO and the World Bank that strengthen the rules-based international trading system. This runs counter to the UK government’s stated objective.

Due to these important gaps and risks, we award an amber-red score for relevance.

Effectiveness: To what extent has the UK achieved its aid for trade objectives?

UK aid for trade has contributed to positive results in both trade negotiations and trade policy and regulatory reforms. It has enabled least developed countries to gain better outcomes in international trade negotiations. It has also contributed to significant reductions in the time it takes for goods to cross national borders, although it is not always clear who benefits from such reductions. Benefits further along the results chain are harder to measure and attribute to UK interventions (see the section on learning), though several FCDO programmes reported increases in trade volumes and values.

UK-funded interventions directly supporting small enterprises and farmers have contributed to positive results for poor and marginalised groups, including women. However, these programmes often faced difficulties in bringing these benefits to scale and sustaining them over time. These types of programme are also relatively expensive and suffered larger reductions when aid budgets were reduced.

There are several examples of programmes contributing to the creation of new jobs, especially in labour intensive industries such as manufacturing, services and agriculture. Our citizen engagement research at an industrial park in Ethiopia demonstrated the potential magnitude of manufacturing jobs, but also the challenges involved in ensuring decent working conditions and sustainable results. In Kenya, our citizen engagement research highlighted improvements in the livelihoods of small traders who use the improved border posts.

Interventions that promote trade and investment can generate both opportunities and risks for local communities. In our case study countries, Ethiopia and Kenya, we found examples of negative effects that were recognised as risks during programme design but were not sufficiently mitigated during implementation. In Ethiopia, these included reports of sexual harassment and gender-based violence suffered by women working in the Hawassa Industrial Park and in the surrounding community (see Box 10 and paragraphs 4.50 to 4.51). The UK had supported measures to reduce risks for workers, including by establishing grievance mechanisms, but was less engaged in identifying and mitigating risks in the wider communities surrounding the industrial parks. In Kenya, the construction of the border post at Busia led to job losses for people working in cargo clearance and forwarding companies, who were laid off as operations moved to other locations.

The COVID-19 pandemic demonstrated the vulnerability of global supply chains to shocks and global crises. The UK showed considerable flexibility in response, and many programmes successfully adapted their activities, helping to provide health support and to keep borders open and trade flowing.

We award a green-amber score for effectiveness since, overall, the UK made significant progress in delivering its intended results in the period before the aid budget reductions. However, the effectiveness of UK aid for trade since 2020 is at considerable risk given the budget reductions.

Learning: How has the UK used learning from ongoing aid for trade interventions to evolve its approach to design and delivery?

There are methodological challenges involved in assessing the wider impacts of aid for trade due to the often long, complex and indirect causal pathways between interventions and their intended impacts. Proving contribution of interventions to results further along the results chain (for example, poverty reduction and distributional effects on different groups including the poor) was a challenge for many programmes. We found that the UK and its partners had not done enough to overcome these measurement challenges, including testing assumptions underpinning programmes, and that their efforts had been curtailed further as a result of the aid reductions. There is recognition among some FCDO staff and partners that more should be done to test assumptions and measure the effects (potential and actual) of aid for trade interventions, especially on poverty reduction and the poor.

In addition, we found that learning across the UK government on aid for trade is largely informal, lacking a systematic approach. We found good examples of learning within programmes that led to improvements, but learning between programmes is less common.

Overall, we award an amber-red score for learning, reflecting inadequate progress in addressing measurement challenges and the limited learning taking place.

Recommendations

We make five recommendations which are intended to help the UK government build on lessons learned.

Recommendation 1

The UK government should develop and publish a set of detailed guiding principles for aid programmes to ensure that the pursuit of secondary benefits to the UK does not detract from its primary poverty reduction objective.

Recommendation 2

FCDO should increase its focus on the international institutions underpinning the rules-based trading system to improve the alignment of the aid for trade portfolio with the UK’s commitment to the rules-based international system.

Recommendation 3

The UK should ensure that future aid for trade programmes are based on clear theories of change linking them to poverty reduction and impacts on the poor, and that the links and assumptions are tested through research, monitoring and evaluation.

Recommendation 4

The UK government should improve coordination and collaboration between programmes that have the potential to complement each other to achieve greater impact and value for money.

Recommendation 5

The UK government should inform its partners in a timely and transparent manner when its budgets increase or reduce significantly, and the pace of change should allow partners sufficient time to adjust.

1. Introduction

1.1 International trade is an important driver of economic growth. Throughout history, economies that trade more have tended to have higher economic growth rates. Developing countries face a range of constraints on their ability to engage in international trade, such as poor infrastructure, high transportation costs and cumbersome border procedures. Addressing these constraints can help boost their international trade. However, the extent to which this contributes to the welfare of the population depends on other factors, such as the availability of quality jobs and the ability of small enterprises to produce goods that are suitable for export.

1.2 Aid for trade is a long-standing area of development cooperation that helps countries expand their trade. According to the World Trade Organisation (WTO), aid for trade is about assisting developing countries to increase exports of goods and services, to integrate into the global economy, and to benefit from liberalised trade and increased market access. At the 2005 WTO ministerial conference, donor countries committed to increasing their support to developing countries to expand trade through aid for trade. Since then, the UK has been a leading provider of aid for trade. This area has gained prominence since the UK’s departure from the European Union (EU), as the UK has sought to strengthen trading ties around the world.

1.3 This review assesses how well the UK’s aid for trade supports economic growth and poverty reduction. It examines the relevance of the UK’s support since 2015, and its effectiveness in tackling the most important constraints on trade and in promoting inclusive economic growth. It also assesses the quality of cooperation across the UK government and with partners; how the portfolio has responded to challenges such as the COVID-19 pandemic and reductions in the UK aid budget; and how well it has monitored results and learned from experience. The main spending departments covered are the former Department for International Development (DFID) and, since 2020, the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO), as well as the cross-government Prosperity Fund which was closed in 2021.

1.4 The choice of this topic reflects the growing focus on trade in UK development strategies since 2015, and the shift towards using aid to promote ‘mutual prosperity’ for both developing countries and the UK. This is the first detailed Independent Commission for Aid Impact (ICAI) assessment of UK aid for trade programming since the 2013 review of DFID’s trade development work in southern Africa, although a 2019 information note provided an account of the pursuit of mutual prosperity within UK aid programming. The 2013 review raised significant concerns about a large aid for trade programme in southern Africa, including mismanagement of funds and an inadequate focus on poverty reduction. The programme was subsequently discontinued. This remains the only review where ICAI has awarded an outright red score.

1.5 The WTO’s Aid for Trade Task Force, set up in 2006, broadly defines aid for trade as including all support to the trade-related development priorities of recipient countries. For the purposes of this review, we categorise aid for trade as follows, drawing on WTO and Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) definitions:

- Trade policy and regulations: Support to help countries develop and implement trade-related policies, regulations (for example, food standards) and trade agreements (for example, multilateral/ WTO, continental and regional agreements).

- Trade facilitation: Support to simplify the process of trading across borders (for example, customs procedures) to reduce the time and cost of trading.

- Building productive capacity: Support to build the capacity of the private sector to export, either directly or via export supply chains, and to benefit from trading opportunities.

- Trade-related infrastructure: Support to develop trade-related infrastructure (such as roads, ports and border posts) to connect domestic markets to regional and international markets.

1.6 Within the UK’s portfolio, activities in the latter two categories are often included in wider economic development programmes that are not primarily about promoting trade. To keep the review tightly focused on trade, we opted to limit our scope to programmes that included support for at least one of the first two categories: trade policy and regulations and trade facilitation. Many of these programmes also include activities under the latter two categories, as well as other support not related to trade.

1.7 Box 1 describes how the review subject links to the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Our review questions are set out in Table 1.

Box 1: How this review relates to the Sustainable Development Goals

The SDGs are a universal call to action to end poverty, protect the planet and ensure that all people enjoy peace and prosperity. The following goals are related to aid for trade:

![]() Goal 1: Reduce at least by half the proportion of men, women and children living in poverty by 2030.

Goal 1: Reduce at least by half the proportion of men, women and children living in poverty by 2030.

![]()

Goal 8: Promote sustained, inclusive and sustainable economic growth, full and productive employment and decent work for all, including through trade.

![]() Goal 9: Build resilient infrastructure, promote inclusive and sustainable industrialisation and foster innovation. Open markets are a key determinant of trade and investment between developing and developed countries, facilitating the transfer of technologies, knowledge and innovation which contribute to industrialisation and development.

Goal 9: Build resilient infrastructure, promote inclusive and sustainable industrialisation and foster innovation. Open markets are a key determinant of trade and investment between developing and developed countries, facilitating the transfer of technologies, knowledge and innovation which contribute to industrialisation and development.

![]()

Goal 10: Ensure enhanced representation and voice for developing countries in decision-making in international institutions to deliver more effective and accountable institutions. This includes special and differential treatment under the WTO which allows more favourable treatment of developing countries, such as more time to implement agreements and measures to increase their trading opportunities.

![]() Goal 17: Promote a rules-based, open, non-discriminatory and equitable international trading system under the WTO; increase developing country exports; double the least developed countries’ share of global exports; and improve market access for least developed countries.

Goal 17: Promote a rules-based, open, non-discriminatory and equitable international trading system under the WTO; increase developing country exports; double the least developed countries’ share of global exports; and improve market access for least developed countries.

Table 1: Our review questions

| Review criteria and questions | Sub-questions |

|---|---|

| 1. Relevance: Does the UK have a clear and coherent approach to aid for trade? | • To what extent has the design of UK aid for trade programmes focused on the most significant constraints to trade? • To what extent has the design of UK aid for trade programmes focused on poverty reduction and inclusion? • To what extent have UK aid for trade programmes adapted to the changing aid and trade context? |

| 2. Effectiveness: To what extent has the UK achieved its aid for trade objectives? | • To what extent has the implementation of UK aid for trade interventions led to reductions in trade constraints, contributing to increased trade? • To what extent has the implementation of UK aid for trade interventions promoted poverty reduction and inclusion, including addressing the distributional impacts of interventions and managing any unintended consequences? •How effectively has the UK worked with international/multilateral and regional organisations and initiatives to deliver more effective aid for trade interventions? |

| 3. Learning: How has the UK used learning from ongoing aid for trade interventions to evolve its approach to design and delivery? | • Has there been systematic and effective monitoring and evaluation of UK aid for trade programmes, including assessing effects on poverty reduction and inclusion? • How effectively have UK aid for trade programmes used monitoring, evaluation and learning from programmes to adapt and improve design and implementation? |

2. Methodology

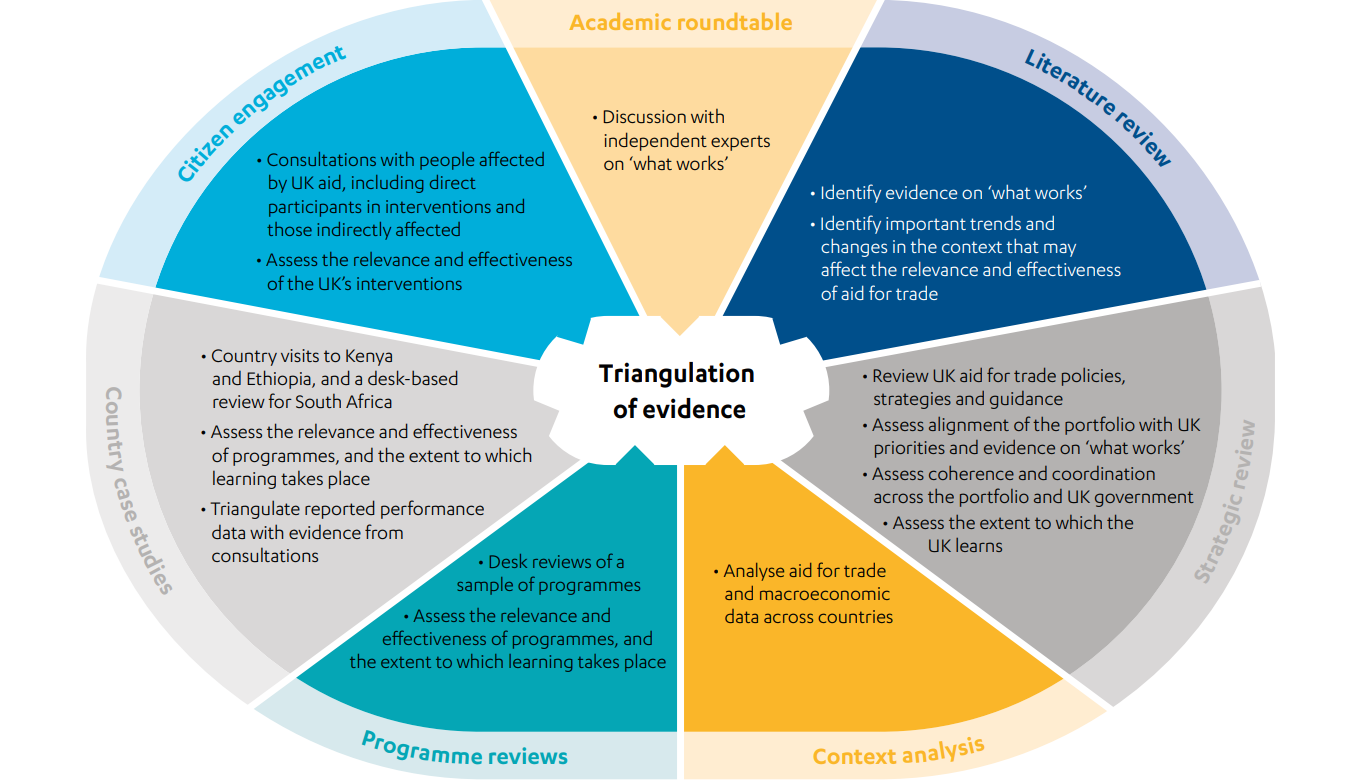

2.1 The methodology for the review involved seven components (Figure 1) to collect and compile evidence against the review questions and ensure sufficient triangulation of evidence to answer these questions.

Literature review: We reviewed published literature on trade and development including aid for trade. We looked at evidence of the main constraints to trade and poverty reduction and ‘what works’ to reduce the binding constraints to trade and contribute to poverty reduction and inclusion. Our literature review is published separately.

Strategic review: We reviewed the UK’s policies, strategies, plans and guidance on aid for trade and how the aid for trade portfolio aligns to UK priorities and evidence from the literature on ‘what works’. We consulted with key stakeholders, including UK government staff, aid for trade experts, other development partners, and international and regional organisations.

- Context analysis: We analysed aid for trade and macroeconomic data across countries, such as national income and share of global and UK trade (exports and imports).

- Programme reviews: We conducted desk reviews of a sample of global, regional and country programmes and conducted interviews with key informants, especially implementing partners. Section 3 and Annex 1 provide details of the programmes selected. Our sampling approach is set out in our approach paper.

- Country case studies: We conducted two country visits (Ethiopia and Kenya) and one desk review (South Africa). The case studies assessed the aid for trade portfolio in each country through examination of programme documents and monitoring data, and interviews with UK officials, government counterparts, implementing partners, development partners and representatives of the private sector and civil society.

- Citizen engagement: In Ethiopia and Kenya, we held consultations with people affected by UK-funded interventions to determine whether these interventions were relevant to their needs and priorities and whether they had experienced positive or negative effects.

- Academic roundtables: We held discussions with academics and independent experts to compare UK strategies and programmes with evidence on ‘what works’ and assess the extent to which the UK’s approach supports inclusive economic growth and poverty reduction.

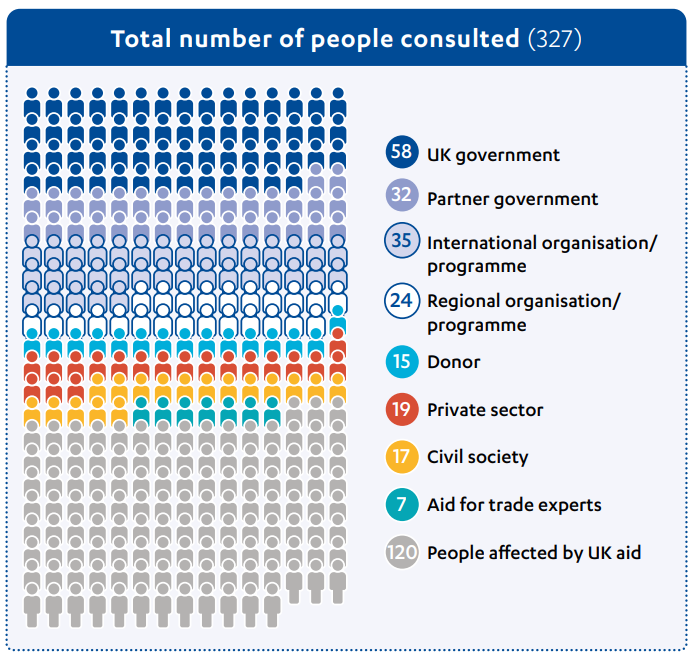

2.2 Overall, we interviewed 207 key informants, collected feedback from 120 people affected by UK aid, and received over 1,100 documents. Figure 2 provides a breakdown of people consulted. Box 2 notes certain limitations to our methodology.

Figure 1: Methodology wheel

Figure 2: Breakdown of people consulted by category

Box 2: Limitations to our methodology

- Scope: Our review covered three country portfolios and a sample of global, regional and country programmes. However, given the diversity of countries where the UK provides aid for trade, the sample was not fully representative of the global portfolio. In particular, for practical reasons, we were unable to include an Asian country case study, even though around 20% of UK aid for trade is spent in Asia (see paragraph 3.17).

- Timing: The review period was one of substantial change and disruption in the UK aid programme, including the Department for International Development and Foreign and Commonwealth Office merger,14 the COVID-19 pandemic and successive large-scale reductions to the UK aid budget. Given the time required to assess the results of aid for trade programmes, our conclusions on effectiveness relate primarily to programmes implemented before this disruption and may not, therefore, be representative of the current portfolio.

- Availability of results data: Weaknesses in the collection of data on the contribution of programmes to outcome-level results limit our ability to draw firm conclusions on the effectiveness of the aid for trade portfolio. There are also difficulties in comparing and aggregating results across the diverse levels and types of interventions involved in the portfolio.

3. Background

The role of trade in international development

3.1 Trade is widely recognised as an important driver of economic growth, with the potential to contribute to poverty reduction in developing countries. Economies that trade more tend to have higher economic growth rates. However, gains from international trade are rarely evenly distributed. Trade can create both winners and losers – for instance, where local firms are unable to cope with increased competition from imports, impacting on jobs and livelihoods. In addition, increased openness to trade may leave the economy as a whole more vulnerable to trade-related price shocks.

3.2 Poorer groups often lack the resources (for example, skills or finance) to benefit from trading opportunities, or face constraints such as remoteness from markets. As a result, efforts to increase trade often need to be accompanied by additional measures to ensure that the poor and marginalised are able to benefit, and to offset any negative impacts on existing jobs and livelihoods. In recent years, there has been increased recognition of the need to consider distributional impacts (that is, who benefits) in the design and implementation of aid for trade programmes.

The global trading environment

3.3 For most of the past half-century, international trade has risen steadily, with most countries moving towards liberal trade policies. This increase in international trade has been a major driver of economic growth and poverty reduction, particularly in China and other Asian countries.

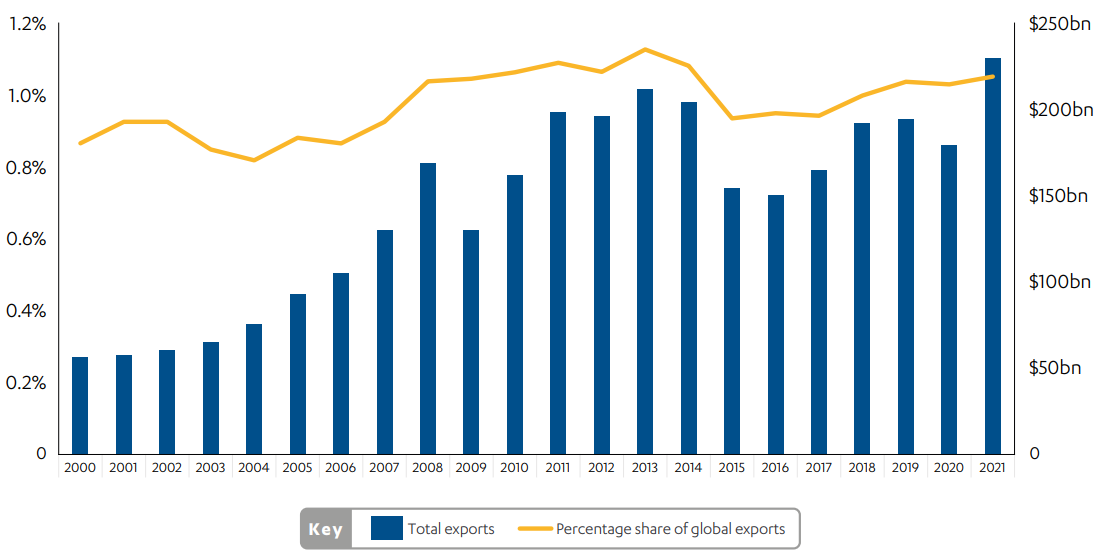

Figure 3: Least developed countries’ total exports and share of global exports, 2000-21

3.4 The SDGs included commitments to doubling least developed countries’ share of global exports by 2020, and to significantly increasing the exports of all developing countries (see Box 1). However, this has been an area of slow progress. Least developed countries’ exports have remained at around 1% of the global total over the past ten years (see Figure 3), while developing countries’ exports have increased only marginally, from 38% to 40% of global exports. Much of this trade consists of raw commodities such as oil, minerals and agricultural produce.

3.5 Since 2018, the trend towards increasing global trade has been disrupted by a range of factors, including protectionist policies in many countries, trade tensions between the US and China, the COVID-19 pandemic, the Russian invasion of Ukraine, high energy prices and inflation. The pandemic also demonstrated the vulnerability of global supply chains to shocks and global crises, leading some commentators to predict a period of ‘deglobalisation’. This may make it more difficult in the coming period for poor countries to benefit from international trade.

What works in aid for trade?

3.6 There is a significant body of literature assessing the effectiveness of different aid for trade interventions. Overall, it shows that interventions which increase market access and reduce the time and cost of trading, such as trade policy and regulatory reform, trade facilitation and trade-related infrastructure, have the potential to contribute to increased trade and economic growth.

3.7 There is less evidence on ‘what works’ in promoting inclusive economic growth that benefits poor communities. The extent to which the poor benefit from reductions in the time and cost involved in trading across borders depends on a range of other factors. For example, farmers and small businesses do not usually export their produce directly, but depend on intermediaries to aggregate, process, package and transport their goods. These intermediaries often directly benefit from measures to simplify trading across borders. The extent to which these savings are passed on to producers and consumers depends on whether there is sufficient competition in these intermediary markets, which is often not the case. If smallholder farmers lack the knowledge and bargaining power to demand higher prices for their produce, then the aid for trade intervention may lead to higher profits for intermediaries. Furthermore, poorer areas may lack firms able to produce goods of export quality. For these reasons, the literature concludes that interventions to facilitate cross-border trade are more likely to benefit the poor when part of a broader package of support.

3.8 There can also be negative impacts for the poor from trade reforms. Increasing international trade can lead to job losses if local producers are unable to match the price or quality of imported goods. Workers may need help to move into new sectors or regions, such as training and relocation support. In addition, the emergence of new, export-oriented industries may call for regulatory measures, such as labour standards, to ensure that they create ‘decent work’.

UK government policy objectives related to aid for trade

3.9 The UK does not have a specific policy, strategy or plan for aid for trade. However, a range of UK strategies and plans include objectives on aid for trade. During the review period, the most relevant policy and strategy documents for the aid for trade portfolio have been the 2011 Trade and investment for growth white paper, the 2015 UK aid strategy, the 2017 Department for International Development (DFID) economic development strategy, the cross-government 2021 Integrated review and the 2022 International development strategy. The UK government’s high-level commitments on trade and development are outlined in Box 3 and summarised below.

3.10 The 2011 Trade and investment for growth white paper demonstrated the UK’s commitment to using trade to drive economic growth and poverty reduction. The 2015 UK aid strategy marked a shift towards using aid in the UK national interest. Alongside the primary objective of promoting economic growth and poverty reduction in developing countries, it emphasised the role of aid in creating trade and investment opportunities for the UK, as a secondary benefit.

3.11 The 2017 DFID economic development strategy recognised trade as “an engine for poverty reduction”. It aimed to improve coherence between UK development cooperation and trade policy by supporting developing countries to take advantage of UK market access after the vote to leave the EU, and to improve the multilateral trading system for the benefit of developing countries. A 2019 DFID Sector best buys document summarised evidence on the effectiveness of different interventions, including aid for trade, which helped inform funding decisions and programme design.

3.12 The 2021 Integrated review and the 2022 International development strategy both included commitments on helping developing countries to increase their trade, including with the UK, alongside commitments to strengthening the global trading system. The 2022 International development strategy emphasised the role of trade in helping countries grow their economies, raise incomes, create jobs and lift people out of poverty. Both documents emphasised the importance of combining aid with trade policy and diplomacy. They outlined a continued commitment to supporting Africa, but with a shift towards countries (namely, Ethiopia, Ghana, Kenya, Nigeria and South Africa) and regions (the Indo-Pacific) with greater potential for increased trade with the UK. The UK remains committed to untying all its aid (that is, refraining from attaching conditions on buying goods or services from the UK), and the 2002 International Development Act continues to require that all aid must be “likely to contribute to a reduction in poverty”.

3.13 The UK government has a Trade for Development (TFD) unit, jointly staffed by Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO) and the Department for Business and Trade. It brings together trade and development expertise and spends both official development assistance (ODA) and non-ODA resources. Its objectives include promoting a free and fair global trading system and promoting international development and poverty reduction through trade. TFD aims to enhance market access for poor countries and ensure that they can take advantage of this through aid for trade interventions, acknowledging that, for the poorest countries, greater access to global markets is not enough.

Box 3: The UK government’s evolving commitments on trade and development

A range of UK government policies and strategies contain commitments that are relevant to the aid for trade portfolio.

The 2011 Trade and investment for growth white paper demonstrated the UK’s commitment to using trade to drive growth and poverty reduction and that “ensuring lower income countries are fully integrated into the global economy is central to the government’s policy of driving growth and poverty reduction”.

It stated that the “UK is committed to assisting poor countries take advantage of the opportunities in the global trading system” and that “international trade is one of the most important tools in the fight against poverty”.

The 2015 UK aid strategy signalled a move towards using aid in the national interest. A key objective was to promote economic growth and prosperity and “contribute to the reduction of poverty and also strengthen UK trade and investment opportunities around the world”. It stated that “no country can eradicate poverty or graduate from aid without economic growth” and “global growth directly benefits the UK, creating new trade and investment opportunities for UK companies”.

The 2017 Economic development strategy stated that: “DFID’s focus and international leadership on economic development is a vital part of Global Britain – harnessing the potential of new trade relationships, creating jobs and channelling investment to the world’s poorest countries.” It affirmed that the government’s approach to trade would centre on poverty reduction. One of its ambitions was to “build the potential for developing countries to trade more with the UK and the rest of the world and integrate into global value chains”. It included commitments to use the UK’s voice in the World Trade Organisation (WTO) and with the World Bank to encourage others to promote free trade with a strong focus on economic development. It highlighted the importance of working across government to agree trade and investment deals that benefit developing countries, and of opening up the UK market to the world’s poorest countries, “bringing trade opportunities to those that need it most”.

DFID produced a 2019 Sector best buys document that categorised interventions in support of economic development from ‘mega’ to ‘bad’ buys, according to the weight of available evidence on their effectiveness. This document has been an important reference point for the design of aid for trade programmes.

The 2021 Integrated review outlines the government’s overall national security and international policy objectives, including on trade and development. It highlights the importance of openness and free trade for global economic growth and poverty reduction. It includes a commitment to developing “mutual partnerships” for “shared prosperity” between the UK and priority countries, through diplomatic efforts, trade agreements and development cooperation. Its objectives on trade include advancing global trade for the benefit of the UK economy, improving developing countries’ integration into the global economy to create stronger trade and investment partners for the UK in the future, opening up opportunities for UK exporters, and contributing to poverty reduction in developing countries. It pledges “to revitalise free, fair and transparent trade by strengthening the global trading system”, and to reform and strengthen the WTO. It emphasises the UK’s continued aid commitments to Africa, along with a shift towards certain regions and countries (East and West Africa – namely, Ethiopia, Ghana, Kenya and Nigeria – and South Africa), as well as an “Indo-Pacific tilt”.

The 2022 International development strategy states that “trade helps countries to grow their economies, raise incomes, create jobs and lift themselves out of poverty. Trade should be conducted within a system of transparent and predictable international rules.” It reiterates the government’s commitment to using “all our capabilities” – including diplomatic influence, trade policy and development expertise – to build strong country-level and global partnerships that benefit both developing countries and the UK. It commits the UK to supporting countries to “increase their exports, increase trade with the UK, build sustainable and resilient global supply chains that benefit all, and tackle market distorting practices and economic policies. This will help low- and middle-income countries become our trade and investment partners of the future, creating secondary benefits for UK business and consumers.” It states that the UK will use its trade policy, including Economic Partnership Agreements and the Developing Country Trading Scheme, to provide better access to the UK market for developing countries. It also suggests a tighter focus on future trading partners, such as Ethiopia, Ghana, Kenya, Nigeria and South Africa, as well as the Indo-Pacific. It states that the UK will provide aid equivalent to 0.2% of gross national income to least developed countries, while also providing aid to middle-income countries “as necessary”.

UK programming relating to aid for trade

3.14 UK aid for trade increased over the review period up until 2019, before declining as a result of aid budget reductions between 2020 and 2022. Support for trade policy and regulations (including trade facilitation) increased from an average of £82 million annually in the 2015-17 period to £106 million in the 2018-19 period, an increase of 28%. When building productive capacity and infrastructure is included, the portfolio increased from an average £2 billion to £2.7 billion annually, an increase of 35% over the same period. This trend mirrored the overall increase in the UK aid budget over the period and made the UK the fourth-largest bilateral provider of aid for trade in 2019, after Japan, Germany and France.

3.15 Since 2020, UK support for aid for trade has reduced due to the overall reductions in the UK aid budget. This began with COVID-related reductions in 2020, followed by the lowering of the UK aid spending target from 0.7% to 0.5% of gross national income in 2021, and the demands on the aid budget caused by the increase in support for refugees in 2022. Total UK ODA fell by 25% in 2021 compared to 2019.

3.16 After the budget reductions, support fell by 14% to an average of £90 million in the 2020-21 period for trade policy and regulations (including trade facilitation) and, when including building productive capacity and infrastructure, fell by 27% to an average of £2 billion. The TFD unit experienced a reduction in its budget to £6 million in 2022-23, from £39.5 million in 2019-20. Most programmes in our sample have seen significant budget reductions.

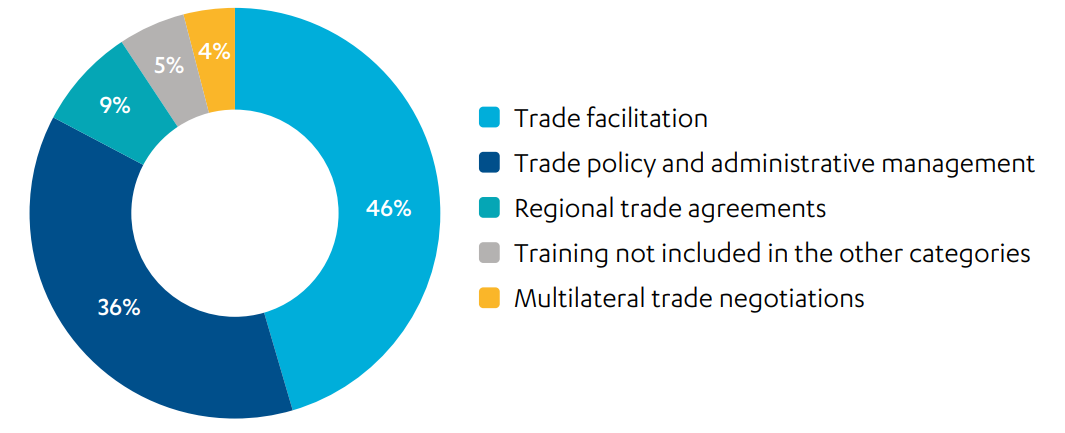

Figure 4: Share of UK government aid for trade spend on trade policy and regulations, 2015-21

3.17 Over the 2015-21 period, UK support for trade policy and regulations (including trade facilitation) amounted to £638.1 million. This support can be broken down as follows:

- Geography: African countries received 44% of the funding and Asian countries received 20%. 34% is ‘unspecified’ geographically, representing global and multi-country programmes. The remaining 2% is linked to other specified countries and regions.

- Sub-categories: The spending is split across the following areas: trade facilitation (46%), trade policy and administrative agreements (36%), regional trade agreements (9%), training not included in the other categories (5%) and multilateral trade negotiations (4%) (see Figure 4).

- Channels: The UK provided 30% of support through multilateral channels and 70% as bilateral aid.

- Spending departments: The former DFID was responsible for 84% of programmes by value, the cross-government Prosperity Fund funded 11%, the former FCO and the Conflict, Stability and Security Fund each accounted for 2%, while the former Department for International Trade and HM Revenue and Customs (HMRC) managed less than 1% each.

3.18 Other important contextual factors during the review period included the vote to leave the EU and the UK’s need to develop its own independent trade policy for the first time in over 40 years, while the COVID-19 pandemic disrupted the implementation of UK aid programmes and trade flows across the world.

3.19 As mentioned, we have limited the scope of our review to programmes with at least one element related to trade policy and regulations and/or trade facilitation (see Table 2 and Annex 1). Details of our sampling approach are in the approach paper. Over the review period, we estimated that spending across the sample was approximately £265 million.

Table 2: Overview of sampled programmes

| Name | Brief description | Region |

|---|---|---|

| Enhanced Integrated Framework (EIF) | Support to least developed countries to use trade as an engine for development and poverty reduction | Global |

| Global Challenges Research Fund (GCRF) Trade Hub | Support to research on sustainable trade | Global |

| Global Trade Programme (GTP) | Support to middle-income countries to reduce barriers to trade, open their markets and increase their capability to trade with the rest of the world including the UK | Global |

| Growth Gateway (GG) | Support to businesses to increase trade and investment between the UK and developing countries | Global |

| SheTrades | Support to increase the participation of women-owned businesses in trade | Global |

| Trade Advocacy Fund (TAF) and Trade and Investment Advocacy Fund (TAF2+) | Support to developing countries to effectively participate in trade negotiations | Global |

| Support for the implementation of the WTO Trade Facilitation Agreement (SITFA) | Support to help developing countries implement the WTO Trade Facilitation Agreement and reduce the time and cost of trading | Global |

| Trade Connect (TC) | Support to developing countries to export to the UK and to UK importers to source from developing countries | Global |

| UK Trade Partnership (UKTP) | Support to trading partners in Africa, the Caribbean and the Pacific to benefit from UK and EU trade agreements | Global |

| Accelerating Ethiopia's economic transformation (ACCELERATE) | Support to economic transformation through promoting manufacturing and improving the investment climate | Africa |

| Ethiopia Investment Advisory Facility (EIAF) | Support to outward-oriented, manufacturing-led, sustainable and inclusive economic growth | Africa |

| FoodTrade East and Southern Africa (FTESA) | Support to stimulate regional food trade to help address shortages and contribute to more jobs and increased smallholder farmer incomes | Africa |

| Africa Food Trade and Resilience (AFTR) | ||

| Trade Forward Southern Africa (TFSA) | Support to businesses to trade regionally, internationally and with the UK | Africa |

| TradeMark East Africa (TMEA) Kenya Country Programme | Support to reduce barriers to trade and improving business competitiveness in East Africa | Africa |

| South Asia Regional Trade and Integration Programme (SARTIP) | Support to expanding markets across South Asia through reducing barriers and improving connectivity | Asia |

| Asia Regional Trade and Connectivity Programme (ARTCP) |

4. Findings

Relevance: Does the UK have a clear and coherent approach to aid for trade?

UK programmes align broadly with UK and partner country priorities

4.1 The UK’s main objectives for its aid for trade programming are to help developing countries to increase their trade, promote economic growth and reduce poverty by improving market access, reducing the time and cost of trading across borders, and building the capacity of firms to export (see Box 3). This includes strengthening the international rules-based system (particularly the World Trade Organisation (WTO) underpinning global trade and economic integration. We find that the portfolio broadly aligns with these objectives.

4.2 In both Ethiopia and Kenya, the programming also reflects government priorities. The Kenyan government has strong ambitions to build the country’s productive capacity and take advantage of existing and emerging trade and integration opportunities. During the review period, Kenya has been a champion of regional integration and trade in East Africa and benefited significantly from the region’s growing international trade. Ethiopia is one of Africa’s poorest countries, but also one of its largest markets. The country has significant potential for economic growth and aims to reach middle-income status by 2025. While it demonstrates the beginning of industrial development, with potential for large-scale job creation and poverty reduction, it has some significant constraints to overcome. Despite its export potential, Ethiopia has been a cautious entrant into the global and regional trade architecture, as demonstrated by its drawn-out negotiations for WTO membership, which began in 2003. It is hoped that the end of the conflict in Tigray and the government’s renewed commitment to economic reform will create new momentum.

4.3 In 2013, the UK transitioned from providing aid to South Africa to focus on low-income African countries. However, a new phase of UK aid engagement began in 2016-17. This reflected the importance of South Africa as a trading partner for the UK, after its departure from the EU, and the shift towards using aid to promote mutual prosperity for both the recipient and the UK.

4.4 Many of the UK’s aid for trade programmes include capacity-building support for officials in partner governments and other organisations. We find this support to be of continuing relevance, given the persistence of significant capacity gaps across the UK’s partner countries, including a lack of skilled staff, limited inter-agency collaboration and inadequate budgets. The UK has appropriately focused its support on lower-capacity environments, such as least developed countries, through programmes such as the Enhanced Integrated Framework and the Trade Advocacy Fund.

The portfolio aligns broadly with available evidence on ‘what works’

4.5 The portfolio reflects the available evidence on ‘what works’ in increasing trade and economic growth. In 2019, the Department for International Development’s (DFID) Research and Evidence Division identified ‘best buys’ across various areas of the aid programme. For economic development programmes, it identified intervention types that the evidence suggests are most likely to be effective and offer value for money, which we refer to collectively as ‘best buys’. It also identified ‘bad buys’ where there is strong evidence that these programmes have not worked in the past or are not cost-effective and ‘low evidence’ interventions where there is not enough rigorous evidence available to make a judgment. Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO) staff frequently refer to the ‘best buys’ document on economic development as steering the overall shape of the aid for trade portfolio, along with departmental and country plans. Our literature review broadly confirmed the analysis in the ‘best buys’ document of the state of the evidence on ‘what works’.

4.6 The aid for trade portfolio broadly aligns with the ‘best buys’ identified in the document. These include support for trade policy and regulations, trade facilitation and trade-related infrastructure. The literature suggests that interventions in these areas have the potential to address binding constraints on trade across the economy, including by increasing market access and reducing the time and cost of trading. During the review period, the bulk of UK government aid for trade has concentrated on interventions in these areas. We found that approximately 90% of interventions in our sample aligned with the ‘best buys’. These intervention areas also reflect the priority given by many developing countries to trade facilitation and the development of transport infrastructure.

The UK is not doing enough to ensure that its aid for trade interventions benefit the poor

4.7 Aid for trade business cases usually state that the programme will contribute to poverty reduction and, in some cases, inclusion, as required by the 2002 International Development Act. However, in some cases, programme designs and theories of change rest on the assumption that trade is, on average, likely to contribute to poverty reduction by promoting economic growth. This includes two of the largest UK aid for trade programmes, TradeMark East Africa and the Global Trade Programme. However, not enough attention is given to ensuring that the necessary conditions are in fact in place for this to occur (see paragraphs 3.2, 3.7 and 3.8).

4.8 The ‘best buys’ document and our literature review identified complementary measures that may be required to increase the likelihood that these interventions will translate into real benefits for the poor. These include support to small enterprises and smallholder farmers to build their capacity to produce export-quality goods and measures to increase competition in intermediary markets such as trucking. There may be a need for measures to mitigate negative impacts, such as the retraining of workers whose jobs are threatened by competition from imported goods. Overall, we found that the UK and its partners were not paying adequate attention to whether the necessary conditions were in place and whether complementary measures were needed. In Kenya, for example, key stakeholders highlighted the importance of building the capacity and competitiveness of the private sector (especially small and medium enterprises and smallholder farmers) to export to unlock the potential gains of other trade-related interventions (see Box 4).

Box 4: TradeMark East Africa: increasing the capacity of the private sector to trade

A key lesson learned from the evaluation of TradeMark East Africa’s first phase (2010-17) is that reducing barriers to trade is not necessarily sufficient to promote trade, economic growth and poverty reduction. Business competitiveness must also be stimulated, especially for small and medium enterprises and smallholder farmers. TradeMark East Africa therefore developed a programme designed to increase the capacity of the private sector to export to complement its work on reducing the barriers to trade, including interventions to support more inclusive trade. However, the UK government decided to allocate most of its funding for TradeMark East Africa to interventions focusing on trade policy and regulations, trade facilitation and trade-related infrastructure.

4.9 Overall, the UK portfolio has a limited focus on building productive capacity for small and medium enterprises and smallholder farmers. The UK has provided some targeted support, including for specific sub-sectors or products where there are pro-poor market opportunities. For example, UK programmes have helped smallholder farmers to form cooperatives, aggregate their produce and improve quality, enabling them to reach the volumes and quality required to sell their produce through export supply chains (such as FoodTrade East and Southern Africa and Africa Food Trade and Resilience). However, key stakeholders informed ICAI that these interventions were significantly cut back when aid budgets were reduced (see Box 5). Some interviewees mentioned that direct support to small and medium enterprises and smallholder farmers is often relatively expensive, per person reached, compared to other interventions.

Box 5: TradeMark East Africa: impact of UK aid reductions

FCDO’s funding of TradeMark East Africa Kenya fell by approximately 50% between 2020 and 2022, with several rounds of budget reductions. Most of FCDO’s spending was allocated to finishing infrastructure projects during that period. This was due to penalties associated with cancelling infrastructure contracts, the reputational risks of leaving infrastructure investments unfinished, the risk of not delivering expected benefits of substantial investments already made, and the importance of these types of interventions for FCDO. The most recent reductions in 2022 were made mid-year, after commitments for higher levels of funding had been made and TradeMark East Africa had already contracted work based on the previously committed funds. Funding reductions led to contract revisions, cancellations and TradeMark East Africa staff redundancies. Some of the funds (including other development partner funds) originally allocated to increasing business competitiveness were diverted to infrastructure investments. Also, business competitiveness interventions were at an earlier stage of development and the potential impact on value for money was considered lower compared to curtailing trade-related infrastructure and trade facilitation investments.

4.10 Overall, we find that the UK is not doing enough to ensure that the private sector, especially small and medium enterprises and smallholder farmers, is able to take advantage of improved trading conditions.

The portfolio shows an increased focus on women, but less on other marginalised groups

4.11 Prioritisation of women has increased in aid for trade programmes during the review period. The UK made a commitment at the G7 to supporting women in developing countries to access jobs and build businesses, including through targeted support to the SheTrades programme. Other examples include the Accelerate programme in Ethiopia, which aims to attract foreign direct investment into the manufacturing sector and generate decent jobs and improve working conditions, notably for women working in the textile industry.

4.12 Several development partners and implementing partners praised the UK’s role, especially the Trade for Development (TFD) unit, as a ‘thought leader’ on women and trade. They described the UK’s approach as “innovative”, and even “transformational”, challenging traditional ways of designing and implementing aid for trade programmes. This has included undertaking influential research on women in trade, mainstreaming gender equality in aid for trade programmes, designing programmes that specifically target women (for example, SheTrades and Accelerate) and numerous examples of disaggregating results data by sex (see paragraph 4.46). According to several interviewees, the UK was willing to take the risks involved in piloting untested approaches, developing models for other development partners and implementing partners to follow.

4.13 Overall, ministers have prioritised women’s economic empowerment. However, the UK decided to provide limited funding to TradeMark East Africa’s Women in Trade programme. This was a new programme under TradeMark East Africa’s second phase (2017-23) (see Box 4). Also, recently, some officials in-country noted a lack of coherence between the priorities set out in the 2022 International development strategy and budget allocations from the centre. Despite the importance given to women and girls in policy documents, budget allocations for women’s economic empowerment were disproportionately affected during the aid reprioritisation process according to some officials in Kenya.

4.14 While most programmes focus on women, there is less emphasis on the inclusion of other marginalised groups (for example, people living with disabilities and youth), particularly since the aid budget reductions. We found only a few examples of programmes targeting youth, such as the Enhanced Integrated Framework (see Box 9), or of efforts to target poorer, more marginalised regions (such as SheTrades). The reductions in support for small and medium enterprises and smallholder farmers has also reduced the focus on inclusion across the portfolio. In addition, our citizen engagement research found inadequate consultation with local communities, including marginalised groups in some instances, limiting the ability to identify and meet their needs (see Box 6).

Box 6: Examples of inadequate consultation with local communities

In Kenya, at the TradeMark East Africa-supported one-stop border post at Busia, consultations took place with cross-border traders before construction began, followed by training on how to use the border post. However, informal traders were not included, and the consultations did not extend to neighbouring communities on either side of the Kenya-Uganda border. In Ethiopia, where the UK is working to improve working conditions and attention to environmental and social impacts at the Hawassa Industrial Park, there appears to have been substantial data gathering from workers inside the Hawassa Industrial Park, but minimal consultation of the community beyond the industrial park perimeter.

The creation of FCDO and improved cross-government coordination are opening up possibilities for a more integrated approach to aid for trade

4.15 Several interviewees mentioned that coordination and collaboration across government had improved in-country to the benefit of the aid for trade portfolio. This was the result of both the DFID and Foreign and Commonwealth Office (FCO) merger and a greater emphasis on cross-government working, which facilitates access to a wider range of expertise across departments. In 2018, the Cabinet Office introduced the ‘fusion doctrine’, which encourages the UK government to make the most of all available ‘levers’ to deliver shared objectives. Recent programme business cases (such as Trade Connect, Growth Gateway and the Standards Partnership Programme) refer to the doctrine. For example, Growth Gateway aims to “maximise [the UK government’s] trade and development offer” by drawing on expertise from several government departments in order to deliver development benefits and secondary benefits to “make the offer greater than the sum of its parts”.

“…deeper integration across government, building on the Fusion Doctrine introduced in the 2018 National Security Capability Review. A more integrated approach supports faster decision-making, more effective policy-making and more coherent implementation by bringing together defence, diplomacy, development, intelligence and security, trade and aspects of domestic policy in pursuit of cross-government, national objectives.”

Integrated review (2021), p. 19, link

4.16 According to several interviewees, the DFID/FCO merger has enabled engagement at a higher, more strategic level on aid for trade, combining DFID’s understanding of political economy issues with FCO’s political and diplomatic access. In Ethiopia and Kenya, cross-government working has enabled access to non-official development assistance (ODA) tools, including economic diplomacy and commercial expertise, to advance trade and development objectives. The merger and the aid budget reductions have encouraged aid officials to explore how to employ other tools, such as economic diplomacy, to deliver results with less money. In Ethiopia, interviewees informed ICAI that FCDO and the Department for Business and Trade regularly discuss how to advance shared goals and engaged jointly with partners on both development and UK commercial interests. In Kenya, we encountered some differences in view between FCDO and Department for Business and Trade staff on priority sectors, possibly due to differences in departmental mandates and understanding of the Kenyan context.

4.17 We also found examples of FCDO and the Department for Business and Trade working more closely with the UK’s development finance institution, British International Investment (BII). Most notably, FCDO’s investments (via TradeMark East Africa) in a road to the Berbera port in Somaliland helped encourage BII to take an initial $320 million stake in a company that is developing the port. FCDO Ethiopia and Somaliland have also contributed to political dialogue that will help to unlock the full potential of BII’s investments at the port.

4.18 In both Ethiopia and Kenya, some officials described cross-government coordination and collaboration as “work in progress” and suggested that the government was yet to take full advantage of the available opportunities. For instance, they suggested there was scope to draw more on the Department for Business and Trade’s expertise and connections to build commercial partnerships between the UK and partner countries that also deliver developmental impacts in-country. There are plans to develop a Trade Centre of Expertise to help UK officials in-country access expertise from across the UK government.

4.19 In addition, we found insufficient coordination and collaboration between programmes that have the potential to complement each other. This includes coordination between centrally managed and bilateral UK aid for trade programmes, between UK aid for trade and wider economic development programmes, and between programmes funded by the UK and by other donors, reducing the potential combined impact of programmes (see also paragraphs 4.66 and 4.67 on learning). That said, UK aid for trade programmes are generally not designed and implemented to dovetail with each other to create a portfolio that is more than the sum of its parts. Nevertheless, given the aid budget reductions, collaboration between programmes to deliver greater impact is arguably more important now.

The recent increase in the priority given to secondary benefits to the UK poses risks to the quality of programming that are not sufficiently managed

4.20 One of the core objectives of the 2015 UK aid strategy was to use UK aid in the national interest, including by strengthening trade and investment opportunities for the UK in developing countries. The strategy announced the creation of the cross-government Prosperity Fund, which aimed to contribute to poverty reduction in middle-income countries while also delivering secondary benefits for the UK. The Prosperity Fund defined secondary benefits as “new economic opportunities for international, including UK, business and mutually beneficial economic relationships”.

4.21 Over the 2015-19 period, apart from the Prosperity Fund, we found limited evidence of UK aid for trade programmes being designed to deliver secondary benefits to the UK, or even targeting countries offering greater opportunities for secondary benefits. Many business cases argued that aid for trade interventions would eventually lead to long-term benefits for the UK through increased trade. The references to secondary benefits often appeared to be included to secure approval for programmes, rather than being integral to their design.

“When we put submissions to ministers, we focus on trade’s role in reducing poverty but to get the best chance of success you need to put this in the context of objectives and benefits for the UK.”

UK government official

4.22 However, since 2019, there are signs that an increased emphasis on secondary benefits in the design of more recent aid for trade programmes is leading the UK government to focus on more developed enterprises and economies. For example, Growth Gateway and Trade Connect aim to promote trade and investment between developing countries and, primarily, the UK. They were designed in response to the UK’s departure from the EU and its commitment to helping developing countries take advantage of new UK trading arrangements. Growth Gateway facilitates connections between enterprises in developing countries and primarily the UK, providing information on opportunities and advice on how to export, rather than directly building the capacity of enterprises to export. According to the literature, these types of programmes usually benefit more established exporters in developing countries and are less effective at enabling non-exporting enterprises to begin exporting. Growth Gateway has identified priority countries and sub-sectors based on analysis of the potential trade with the UK, together with development impact, and is, therefore, working mainly in countries with relatively strong export capacity (for example, Kenya, Nigeria and South Africa) (see paragraph 4.23). The programme works mainly with more established enterprises in more developed markets, suggesting a shift away from aid for trade interventions that benefit smaller enterprises and poorer countries. Given that few new programmes have been designed since the UK aid budget reductions began, it is difficult to assess at this stage how pronounced this trend will be.

4.23 Some interviewees confirmed that the emphasis on secondary benefits to the UK has increased since the FCO/DFID merger and in response to the increased prominence given to UK trading interests in government policies and strategies. In the past two years, the UK has shifted its geographical focus within Africa to larger economies, such as Ghana, Kenya, Nigeria and South Africa, where the potential trading opportunities for the UK are stronger. These countries are in the top ten African markets for UK exports and imports, with South Africa ranked first and Nigeria second. While there is poverty in these countries, poverty levels are greater in other countries in sub-Saharan Africa where FCDO, and the former DFID, traditionally provided more support (for example, Malawi, Tanzania and Zambia).

4.24 Many of the UK officials we interviewed took the view that aid programmes could legitimately deliver economic benefits for both the UK and developing countries. This is in line with a similar finding in our earlier information note on mutual prosperity objectives in UK aid programmes. While this may be correct in principle, there is a lack of detailed guidance on how to incorporate secondary benefits without compromising the primary purpose of UK ODA, which is poverty reduction. The Prosperity Fund developed and published guidance on secondary benefits, but this is no longer in use. FCDO staff and FCDO’s programming framework specify that secondary benefits should not be considered unless the primary purpose is satisfied, ensuring that programmes are compliant with the 2002 International Development Act. However, the framework states that, where two projects are both likely to contribute to poverty reduction, “it is legitimate to choose between them on the grounds of secondary benefit”. As mentioned in our earlier information note, this leaves open the risk that officials will select interventions with relatively lower potential for poverty reduction to secure benefits for the UK, thereby compromising the quality of programming.

4.25 The UK is in the process of considering the case for guidance on secondary benefits. Overall, we found that the UK currently does not have robust enough rules or requirements in place to protect against risks to the quality of UK aid. In the absence of clear guidelines on aid use, beyond compliance with the 2002 International Development Act, the ability of FCDO to manage these risks is likely to be overly reliant on senior staff and ministers giving priority to development objectives, as highlighted in an earlier ICAI country portfolio review.

UK aid budget reductions have left the portfolio spread thinly across priorities and countries, and reduced UK support for the international trading system

4.26 During the review period, one of the main objectives of the TFD unit was to support the international trading system and enhance the ability of developing countries to participate, negotiate and take advantage of market access opportunities. During the recent reprioritisation of UK aid, TFD suffered a major reduction to its budget, receiving only £6 million in 2022-23, compared to £39.5 million in 2019-20. The unit sought to retain as many of its active programmes as possible and was, therefore, obliged to cut individual programme budgets dramatically. This has led to a portfolio that is spread thinly across countries, programmes and priorities. At present this does not look like an effective use of resources, although it may make it easier to scale up the portfolio in the future if more funds become available.

4.27 TFD has also significantly reduced its support to institutions and programmes that strengthen the international trading system. It ended its support for WTO and World Bank programmes that support implementation of the WTO Trade Facilitation Agreement (TFA), in favour of channelling resources through UK-based institutions, including HM Revenue and Customs (HMRC) and the British Standards Institution. TFD retained some support to other international partners, such as the International Trade Centre and the World Customs Organisation. This reprioritisation reflects the goal of increased reliance on UK expertise, as set out in the 2021 Integrated review and 2022 International development strategy. However, it runs counter to the UK government’s stated objective of supporting the rules-based international trading system. It also reduces potential economies of scale generated through funding multi-donor initiatives through multilateral partners.

Rapid ODA reductions, and the way these were managed, have had a detrimental impact on the UK’s relationships and reputation

4.28 The reprioritisation of aid for trade programming in response to UK aid budget reductions was a top-down process managed at FCDO headquarters. There was limited communication with officials in-country, who were often obliged to notify partners abruptly of substantial reductions in UK support. There has also been a long period of uncertainty over the available resources, making it impossible to engage in forward planning.

4.29 Some of the UK’s aid for trade implementing partners have been obliged to postpone or cancel activities and make staff redundant. While they understand that priorities change, they noted that greater transparency and more timely information would have enabled them to manage the changes more effectively. For the majority of those we interviewed, the unpredictability, rather than the reduced funding, was their chief concern.

4.30 As a donor, the UK also had a reputation for providing valuable strategic inputs into programming. For instance, FCDO exercised leadership through its support to macroeconomic reforms in Ethiopia. Alongside its funding, it provided oversight and strategic direction to TradeMark East Africa for more than ten years, which gave other development partners the confidence to fund the programme. However, the effort going into budget reprioritisation over the past two years has limited the ability of UK officials to provide strategic inputs and direction. According to many interviewees, the reduction in strategic inputs and financial resources has led to a decline in UK influence. For multi-donor programmes such as TradeMark East Africa, this also poses risks to other funders who, to some extent, have relied on FCDO’s financial and strategic inputs as well as oversight.

4.31 While the Ethiopian and Kenyan governments continued to stress to ICAI the value of their partnership with the UK, there are concerns among UK officials that the UK’s influence will quickly diminish if budget reductions continue and new funding does not materialise. We found that some partners believe that their funding is paused, with several government partners expecting resources to return to previous levels. The UK needs to be transparent about its funding intentions, to enable partners to either seek funding elsewhere or adjust their programming.

Conclusions on relevance

4.32 Overall, we find the UK’s approach to aid for trade broadly reflects the priorities of partner countries and the evidence on ‘what works’ in increasing trade and promoting economic growth. However, the portfolio is not paying sufficient attention to ensuring that poorer countries and people benefit. The creation of FCDO and the increased focus on cross-government working have created potential benefits for the portfolio, but also raise risks that the pursuit of secondary benefits to the UK may compromise the quality of programming. The recent aid budget reductions have had detrimental effects on the portfolio and on the UK’s influence with partners, while also resulting in a portfolio that is thinly spread across programmes, themes and countries. For these reasons, we award an amber-red score for relevance.

Effectiveness: To what extent has the UK achieved its aid for trade objectives?

UK aid for trade has contributed to positive results in both trade negotiations and trade policy and regulatory reforms

4.33 UK support to developing countries to participate in trade negotiations (see Box 7) has empowered countries, especially least developed countries, to engage in trade negotiations and achieve favourable results. For instance, the UK has supported Afghanistan, Comoros, Ethiopia, Somalia, Sudan and Uzbekistan in the process of seeking accession to the WTO. Afghanistan acceded to the WTO in 2016 and Uzbekistan reaffirmed its commitment to the accession process in July 2022. In Ethiopia, according to interviews, the accession process has resumed following the signing of the peace accord, although the government has generally been reticent on international and regional trade arrangements over the years.

Box 7: UK support to trade negotiations

The Trade and Investment Advocacy Fund support to help developing countries participate in WTO ministerial conferences and negotiations was praised as one of the most significant achievements, according to FCDO and partner country interviewees. This includes:

- Demand-driven independent legal advice to developing countries provided by the Advisory Centre on WTO Law, including assisting with 70 legal disputes and providing an average of 213 legal opinions per year.