UK aid for trade

Purpose, scope and rationale

‘Aid for trade’ is development assistance that helps developing countries to build their capacity to benefit from international trade. The purpose of this review is to assess whether UK aid for trade is designed and delivered to support inclusive economic growth and poverty reduction.

The review will examine the relevance and effectiveness of UK aid for trade since 2015, assessing to what extent programmes address binding constraints to trade and promote poverty reduction and inclusion. The review will also assess how effectively the UK has worked with partners at the international, regional and country levels. Other important issues will include whether the UK has adapted its approach to the changing context (domestically and globally), whether it has caused inadvertent harm, and how well it has used learning to improve programming. The review will focus on support provided through the Department for International Development (DFID), the Foreign and Commonwealth Office (FCO) and, subsequently, the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO), as well as the cross-government Prosperity Fund.

The choice of this review topic reflects the strong focus on trade in the UK’s 2015 and 2022 international development strategies, including the dual objectives of poverty reduction in developing countries and securing benefits for the UK. ICAI has not conducted a detailed assessment of UK aid for trade programming since the 2013 review of DFID’s trade development work in southern Africa, although our 2019 information note on the use of UK aid to enhance mutual prosperity assessed some related issues. The 2013 review highlighted some serious challenges, including a lack of focus on poverty reduction, while the 2019 information note flagged the risk that the focus on poverty reduction might be diluted by the pursuit of benefits for the UK. This review provides an opportunity to assess the wider aid for trade portfolio, offering evidence to inform improvements in programming, as well as examining how the UK balances its objectives on aid for trade.

The World Trade Organisation Aid for Trade Task Force, set up in 2006, defines ‘aid for trade’ broadly as including all support to the trade-related development priorities of recipient countries. This includes the following categories:

- Trade policy and regulations and trade-related adjustment including: building the capacities needed to develop national trade policies, participate in regional and multilateral trade negotiations and implement trade agreements; facilitating trade through improvements and simplification of export and import procedures to support, for example, improved compliance with international standards and reducing burdensome customs procedures at the borders; and helping developing countries with the costs associated with trade liberalisation, such as tariff reductions which lead to reductions in government revenue.

- Building productive capacity by supporting the productive sectors of the economy (such as agriculture, industry and services) to build their capacity to export.

- Economic infrastructure, including support to help countries build the physical means (such as transport, storage, communications and energy) to produce, move and export goods.

In practice, however, some development partners classify all their support to the productive sectors or infrastructure as aid for trade, including support that does not have any trade-related objectives. In setting the scope for this review, we will include UK programmes that include at least one element of support related to trade policy and regulations. This enables us to cover the range of activities listed above, while keeping the review focused on trade.

Background

Trade is an important driver of economic growth, with the potential to contribute to poverty reduction in developing countries. Economies that trade more tend to have higher growth rates. However, gains from trade are rarely evenly distributed across the economy and changes to trading patterns can create winners and losers. Particular regions, communities or social groups may face adjustment costs (such as increased competition from imports and job losses) or experience only limited benefits (due, for example, to remoteness, poor infrastructure and/or unequal access to resources). The economy as a whole may become more vulnerable to trade-related shocks, such as spikes in key prices. For this reason, efforts to increase trade often need to be accompanied by additional measures to cushion the impacts on people living in poverty and ensure they are able to benefit. In recent years, there has been increased recognition of the need to apply an ‘inclusion lens’ to the design of aid for trade programmes.

The UK government’s 2015 and 2022 international development strategies shifted the focus of UK aid towards economic growth and trade. The objectives included supporting developing countries to increase their exports and to trade more with the UK, thereby creating secondary benefits for UK business. The UK remains committed to complying with the provisions of the International Development Act 2002 that aid is untied (in other words, that aid is not offered on the condition that it be used to procure goods or services from the UK). The 2022 strategy emphasises the potential of trade to help countries grow their economies, raise incomes, create jobs and lift people out of poverty.

Over recent years, the changing aid and trade context, in the UK and globally, has affected the direction of aid for trade and the shape of the portfolio. This includes UK-specific factors such as aid budget reductions and Brexit, as well as global factors such as the COVID-19 pandemic, war in Ukraine and the rise in protectionism.

According to the latest aid statistics, the UK was among the top ten providers of aid for trade between 2015 and 2020, behind Japan, the World Bank, EU institutions, Germany and France. However, the latest figures do not capture the significant reductions to UK aid that have taken place since 2020, and it is likely that the UK has moved

down the ranking.

Between 2015 and 2020, UK support specifically to trade policy and regulations amounted to £416 million. Below, we summarise the main characteristics of this type of support:

- Geography: African countries received 44% of the funding, and Asian countries 20%. 34% is ‘unspecified’ geographically, representing global and multi-country programmes. The remaining 2% is linked to other specified countries and regions.

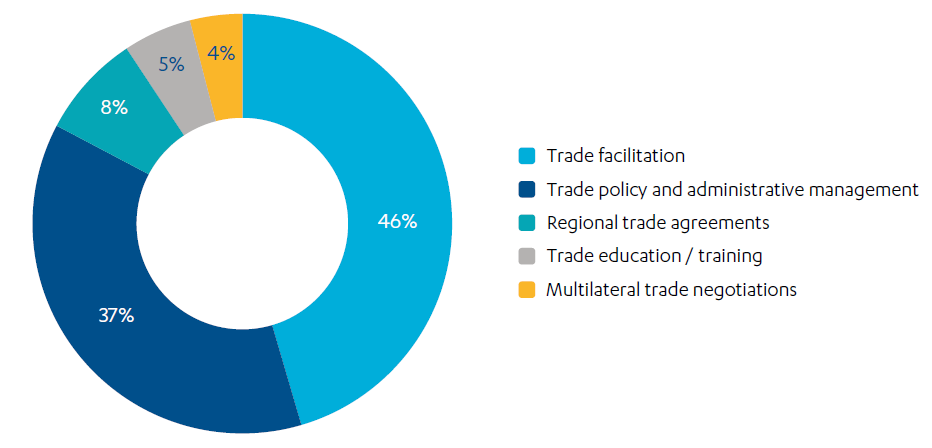

- Sub-categories: The spending is split across the following areas (see Figure 1): trade facilitation (46%), trade policy and administrative agreements (37%), regional trade agreements (8%), trade education/training (5%) and multilateral trade negotiations (4%).

- Channels: The UK provided 30% of support through multilateral channels and 70% bilaterally.

- Government departments: Across government departments, the former DFID was responsible for 84% of programmes by value, the cross-government Prosperity Fund funded 11%, the former FCO and the Conflict, Stability and Security Fund each accounted for 2%, while the Department for International Trade and HM Revenue and Customs managed less than 1% each.

Figure 1: Trade policy and regulations aid for trade sub-categories, 2015-20

The UK appears to report all of its support to productive sectors and infrastructure as aid for trade. Using this broad definition, the aid for trade portfolio included over £9 billion in support during the review period. Interventions in these two areas tend to be of higher value than support for trade policy and regulations, which is mainly technical assistance. We have limited the scope of our review to programmes with at least one element related to trade policy and regulations. Given these programmes often include support to other areas, such as economic infrastructure, this results in a portfolio of approximately £1.5 billion, covering 64 programmes. All the programmes support trade policy and regulations, 48% include support for building productive capacity, and 22% include support for economic infrastructure.

Review questions

The review is built around the evaluation criteria of relevance and effectiveness, as well as learning. It will address the questions and sub-questions listed in Table 1.

Table 1: Our review questions

| Review criteria and question | Sub-questions |

|---|---|

| 1. Relevance: Does the UK have a clear and coherent approach to aid for trade? | • To what extent has the design of UK aid for trade programmes focused on the most significant constraints to trade? • To what extent has the design of UK aid for trade programmes focused on poverty reduction and inclusion? • To what extent have UK aid for trade programmes adapted to the changing aid and trade context? |

| 2. Effectiveness: To what extent has the UK achieved its aid for trade objectives? | • To what extent has the implementation of UK aid for trade interventions led to reductions in trade constraints, contributing to increased trade? • To what extent has the implementation of UK aid for trade interventions promoted poverty reduction and inclusion, including addressing the distributional impacts of interventions and managing any unintended consequences? • How effectively has the UK worked with international/multilateral and regional organisations and initiatives to deliver more effective aid for trade interventions? |

| 3. Learning: How has the UK used learning from ongoing aid for trade interventions to evolve its approach to design and delivery? | • Has there been systematic and effective monitoring and evaluation of UK aid for trade programmes, including assessing effects on poverty reduction and inclusion? • How effectively have UK aid for trade programmes used monitoring, evaluation and learning from programmes (UK-funded and other donors/multilaterals) to adapt and improve design and implementation? |

Methodology

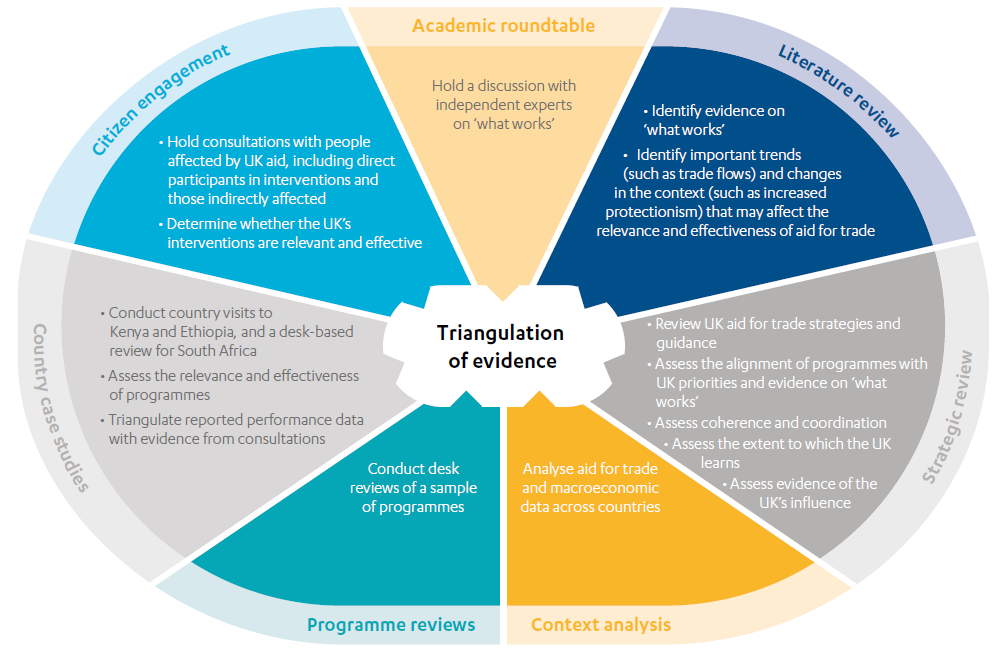

The methodology includes the following seven components (Figure 2) to allow for data triangulation to robustly answer the review questions. The methodology will employ qualitative approaches throughout, except for the context analysis where we will analyse aid and macroeconomic data to better understand the context in each country.

Figure 2: Methodology overview

Component 1 – Literature review: We will conduct a review of the available peer-reviewed and grey literature. The literature review will assess the evidence on ‘what works’ in aid for trade programming to enable us to determine the degree to which the UK approach reflects evidence and best practice. It will also inform our context analysis (Component 3) by identifying relevant contextual changes to help the team assess the extent to which these have been factored into the design and adaptation of UK strategies and programmes. Overall, it will help to contextualise the current trends and developments in UK aid for trade.

Component 2 – Strategic review: We will conduct a review of relevant UK policies, strategies and guidance on aid for trade, and examine whether these reflect the available evidence identified in the literature review. We will expand our initial mapping of aid for trade programmes to examine whether the portfolio aligns to UK priorities, as well as the evidence base on ‘what works’. We will assess coherence and coordination across government departments and with other development partners on aid for trade. We will also review how well departments are learning, including efforts to collect, synthesise, share and use evidence. This component will also seek evidence of the UK’s influence on key international, multilateral and regional organisations involved in aid for trade.

In addition to the document review, we will undertake stakeholder interviews with relevant UK government staff and key external stakeholders, including academics, development partners, and private sector and civil society representatives, including interviews with relevant stakeholders in Geneva. We will also conduct interviews with members of the Trade for Development Thematic Working Group, Trade Centre of Expertise and Trade for Development Board.

Component 3 – Context analysis: This component will analyse aid for trade and macroeconomic data (such as trade, growth and poverty) across countries. This will enable the team to assess the context in each country and inform the assessment (through the strategic review, programme reviews and country case studies) of the extent to which contextual changes are factored into strategies and programme design and adaptation.

Component 4 – Programme reviews: We will conduct desk reviews of a sample of programmes by reviewing relevant programme documents and conducting interviews with responsible government officials and implementing partners, including in Geneva. We have selected a sample of programmes based on the criteria described in Section 5. The programme reviews will assess whether the programme designs are evidence-based, the extent to which they are implemented effectively and achieving their intended results, and the degree to which any learning leads to improvements.

Component 5 – Country case studies: We will conduct two country visits and one desk review. We have selected Kenya and Ethiopia for the country visits and South Africa for the desk review. The case studies will assess the UK aid for trade portfolio in each country, collecting and analysing evidence on the relevance and effectiveness of programmes and the extent to which learning is taking place to improve design and implementation. This includes assessing whether programming reflects the underlying evidence base and context, UK priorities in policies and strategies, and any guidance on aid for trade. The case studies will triangulate reported performance data with evidence from key stakeholder interviews with programme counterparts and implementers and other informed observers, as well as feedback from people affected by UK aid (Component 6).

Component 6 – Citizen engagement: ICAI is committed to incorporating the voice of people affected by UK aid into its reviews. Consultations with people affected in Kenya and Ethiopia will be undertaken by a national research partner. The consultations will include direct participants in UK programmes and those indirectly affected by the interventions, to determine whether the UK’s interventions are relevant to their needs and priorities and whether any potential negative effects are assessed and mitigated. Findings will be triangulated through review of relevant available secondary data on citizen views in the two countries.

Component 7 – Academic roundtable: We will hold a discussion with independent experts to compare UK strategies and programmes with evidence on ‘what works’ and assess the extent to which the UK’s approach supports inclusive growth and poverty reduction, and whether it is relevant in light of a changing global context.

Sampling approach

The methodology involves two sampling elements: selection of global and regional programmes and three case study countries. The country case studies will include those global and regional programmes that are/were active in the selected countries, as well as bilateral programmes.

Table 2: Sampling criteria for global and regional programmes for the programme review

| Primary criteria |

|---|

| Budget size greater than £10 million |

| Balanced coverage of aid for trade categories |

| Approval before 2020 |

| Secondary criteria |

| Mix of implementing partners |

| Coverage of relevant UK government priorities and objectives |

| Includes programmes suitable for engagement with people affected by UK aid |

Table 3: Sampling criteria for country selection for country case studies

| Primary criteria |

|---|

| Size of portfolio for aid for trade |

| Number of programmes |

| Mix of income groups: least developed countries (LDCs), lower-middle-income countries (LMICs) and upper-middle-income countries (UMICs) |

| Includes programmes suitable for engagement with people affected by UK aid |

| Secondary criteria |

| Coverage of relevant UK government priorities and objectives |

| Coverage of aid for trade categories |

We selected ten global and regional programmes from a long list of 64, based on our initial scoping research and information provided by FCDO and using the sampling criteria in Table 2. The sample covers different aid for trade categories and a mix of implementing partners such as the World Trade Organisation and the UN, as well as the private sector and civil society. It also includes programmes which have the potential to benefit people both in low- and middle-income countries and in the UK. We will also add any additional relevant bilateral programmes for the country case studies.

Based on the criteria in Table 3, we selected Kenya and Ethiopia as country case studies, plus South Africa for a desk review. Both Kenya and Ethiopia are in the top ten recipients of UK aid for trade. The selection covers a range of income groups (LDCs, LMICs and UMICs), programmes across aid for trade categories and a mix of country, regional and international programmes. The selection also covers programmes that reflect UK priorities on aid for trade (for example, dual objectives of poverty reduction while securing benefits for 8 the UK and continent-wide integration) and programmes which lend themselves to the citizen engagement component (in other words, the ability to identify and reach affected populations).

Specific reasons for selecting the countries include the following

- Kenya has the highest number of aid for trade programmes in sub-Saharan Africa, including the UK’s largest ‘flagship’ aid for trade programme, TradeMark East Africa, which focuses principally on regional integration in East Africa.

- Ethiopia has an high number of aid for trade programmes and is an LDC.

- The South Africa portfolio includes an active legacy Prosperity Fund programme working across government departments.

Limitations to the methodology

We will rely primarily on data generated by the programmes in the scope of this review, plus any relevant evaluations to assess effectiveness. We will manage the resulting risk of evidence gaps and bias by collecting and triangulating evidence through interviews with implementing partners, other development partners and, in the case study countries, through consultations on the ground.

Given the long and complex causal links between trade interventions, poverty reduction and inclusion, we may struggle to find evidence and adequate insight of the effects on poverty reduction and inclusion. To mitigate this, we will identify key testable elements in the theories of change and use secondary evidence (for example, in the literature) to supplement our assessment of effectiveness.

Inadequate labelling of support as aid for trade due to FCDO statistical and reporting issues, especially at the country level, may lead the team to inadvertently omit relevant programmes. To mitigate this, the team will work with FCDO country offices (Kenya, Ethiopia and South Africa) early on to identify any additional programmes.

Risk management

We have identified several risks associated with this review and propose a series of mitigating actions, where necessary, as presented below in Table 4.

Table 4: Risks and mitigation

| Risks | Mitigation and management actions |

|---|---|

| Limited historical memory in the departments going back to 2015 | We will exclude programmes that were completed before 2020. We will also secure contact details of previous advisers and emphasise the importance of their insights for the review, especially with respect to learning. |

| Sensitivities of programme information lead to resistance from the UK government in sharing information and insights | We will mitigate this through effective relationship management and emphasising the learning opportunity from this review. |

| Different interpretations of aid for trade definitions | We will make it clear to all how we are defining aid for trade for the purpose of this review. |

| Programme budgets available online may not be up to date | We will work closely with FCDO to ensure all figures used are accurate. |

Quality assurance

The review will be carried out under the guidance of ICAI lead commissioner Sir Hugh Bayley, with support from the ICAI secretariat. The review will be subject to quality assurance by the service provider consortium. Both the methodology and the final report will be peer-reviewed by Dr Mohammad Razzaque, an expert in applied international trade and development policy analysis.

Timing and deliverables

The review will take place over an 11-month period, starting from July 2022.

Table 5: Timing and deliverables

| Key stages and deliverables | Dates/timeline |

|---|---|

| Inception | Approach paper publication: October 2022 |

| Data collection | Desk research: July – September 2022 Fieldwork: October – November 2022 Evidence pack: December 2022 Emerging findings presentation: December 2022 |

| Reporting | Report drafting: January 2023 – April 2023 Final report: May 2023 |