UK aid funding for refugees in the UK

Introduction

This paper provides an overview of the approach and methodology used by the Independent Commission for Aid Impact (ICAI) for its rapid review of official development assistance (ODA) funding for refugees in the UK. The review will complement previous scrutiny of the UK government’s policy and practice in supporting refugees and asylum seekers conducted by the Public Accounts Committee (PAC) and the National Audit Office (NAO). Unlike these earlier reports, ICAI will only review aspects of UK spending that are covered by the UK aid budget.

Background

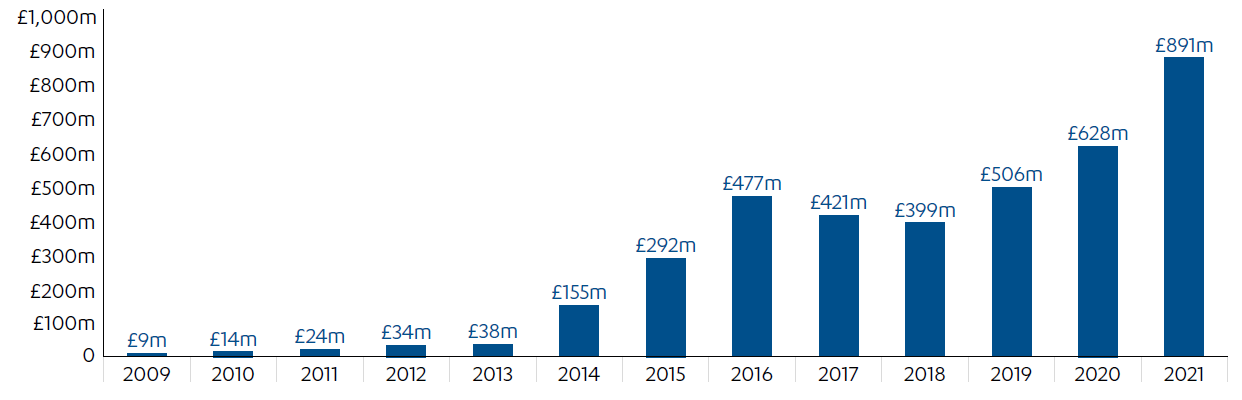

The review will examine all UK ODA spent on supporting refugees and asylum seekers within the UK between 2015 and 2022 and reported annually to the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development’s Development Assistance Committee (OECD-DAC) as ‘in-donor refugee support’. This aid-spending category, where donors report expenses related to hosting refugees and asylum seekers in their own country, has become a significant part of aid spending, amounting to billions of dollars globally every year. The UK started reporting in-donor refugee support to the DAC in 2009, with a sharp increase between 2014 and 2016, and another steep rise from 2019 onwards. In 2021, preliminary data from the OECD shows that the UK reported £891 million as in-donor refugee costs, and further significant increases are expected in 2022. Figure 1 below shows UK spending under this category from 2009 to 2021, as reported to the OECD-DAC.

Figure 1: UK aid reported as in-donor refugee costs, 2009-2021*

*The data, which are in constant prices (2020 USD millions), are retrieved from OECD Query Wizard for International Development Statistics and are converted to GBP following the OECD exchange rate of 2020. The figures are rounded up to the nearest million.

In-donor refugee support costs made up more than 8% of all UK ODA in 2021. There is no cap on how much of the UK aid budget can be spent on in-donor refugee support. The Home Office uses an accounting mechanism to calculate the proportion of its costs of supporting refugees in the UK that it can bill as ODA. This accounting mechanism has remained unchanged while the overall UK aid budget has been reduced from 0.7% to 0.5% of gross national income. As such this spending has continued to increase, unaffected by the budget reductions imposed across most of the UK’s aid programming. It is therefore important that ICAI scrutinises this significant and growing proportion of UK aid.

Purpose and scope

The review will cover all UK ODA spent on supporting refugees and asylum seekers within the UK, as reported to the OECD-DAC as ‘in-donor refugee support’ between 2015 and 2022. ICAI will engage with government departments and bodies involved in the planning, delivery, coordination, reporting and oversight of ODA-funded in-donor refugee support spend across government, including local government. The main department involved in this spend is the Home Office, while the Department for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities runs the Homes for Ukraine scheme, significant parts of which are ODA-funded. The Department for Education and the Department of Health and Social Care also spend ODA under this category. The Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office is responsible for reporting ODA spend to the OECD-DAC.

lCAI has not reviewed this topic before and there is little publicly available information on this large and growing part of the UK’s aid budget. It is a topic of public interest, and of interest to Parliament’s International Development Committee, in a time when the UK aid budget is under significant pressure. The review will complement and follow up on the ODA-relevant aspects of recent recommendations by the PAC and the NAO.

Scope: what can be counted as in-donor refugee ODA costs?

There are relatively clear rules on what can be counted as in-donor refugee costs, although different donors pursue different approaches within these rules. In 2017, the DAC set out five ‘clarifications’ on how to report in-donor refugee costs as ODA (see Figure 2 below).

Figure 2: The five DAC clarifications on reporting in-donor refugee costs*

| The rationale: The rationale for counting in-donor refugee costs as ODA is that refugee protection is a legal obligation and that providing assistance to refugees may be considered a form of humanitarian assistance |

| Eligible categories: Asylum seekers and recognised refugees, following international legal definitions, are the two eligible categories covered |

| Time limitation: The ‘12-month rule’ means that only costs incurred in the first 12 months after arrival are eligible |

| Eligible cost: All kinds of temporary sustenance costs such as food, shelter and healthcare, and school for refugee children, as these can be described as humanitarian in nature. But no costs towards integration in the host country or any form of coercion, such as detention centres |

| Methodology for assessing costs: The need for a conservative approach to reporting against this category |

*The clarifications can be found on the OECD-DAC website.

Using the five clarifications, the UK has created a methodology and shared this with the DAC, which allows it to report a certain share of its refugee and asylum seeker costs as ODA.3 Table 1 sets out the categories and schemes that have been confirmed to ICAI by the Home Office as ODA-eligible and that are therefore in scope for this review.

Table 1: Refugee and asylum seeker support schemes in scope

| Support scheme | Description | Responsible department |

|---|---|---|

| UK Resettlement Scheme (UKRS) | Mainly used for resettling Syrian refugees and using selection criteria set out by the UN Refugee Agency, UNHCR. There are no targets for resettlement through UKRS. Resettled refugees are supported through local authorities. | Home Office |

| Vulnerable Persons Resettlement Scheme | Mainly resettled Syrian refugees, concluded February 2021. | Home Office |

| Vulnerable Children’s Resettlement Scheme | Mainly resettled Syrian refugees, concluded February 2021. | Home Office |

| Afghan Citizens Resettlement Scheme | Launched in January 2022 to resettle Afghan refugees. | Home Office |

| Homes for Ukraine | Refugee sponsorship scheme launched 14 March 2022 to house Ukrainian refugees in private citizens’ homes. | Department for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities |

| Asylum seekers (general process) | Asylum seekers who arrive in the UK individually and whose claim to asylum is in the process of being determined. Support to asylum seekers may be counted as ODA in the first year after their arrival, including during the appeals process for those whose application failed in the first instance. | Home Office |

| Modern Slavery Victim Care Contract | ODA support in the first year is given to some victims and survivors of modern slavery. | Home Office |

| There is in addition spend by the Department for Education and the Department of Health and Social Care to cover primary school and NHS costs for refugees and asylum seekers in the first year after arrival. This is not under any specific scheme. | ||

Review questions

ICAI will assess the relevance, effectiveness and coherence of in-donor refugee support spending. The review questions are listed in Table 2 below.

Table 2: Our review questions

| Review criteria and questions | Sub-questions |

|---|---|

| Relevance: How relevant is the UK’s approach to spending official development assistance (ODA) on in-donor refugee support to its development strategy, its legal requirements towards refugees and asylum seekers, and to the OECD-DAC reporting criteria and international best practice in this area? | • How does the UK’s approach to ODA spending on in-donor refugee support align with the overall objectives and delivery of the UK aid programme? • How well does the UK’s approach to in-donor refugee support meet international best practice when benchmarked against other donors? • How does this spend align with key UK commitments, specifically the Sustainable Development Goals and the Global Compact on Refugees? • How is ODA eligibility, management and oversight organised and ensured? |

| Effectiveness: How well are standards for aid delivery in support of refugees in the UK being met? | • To what extent is value for money achieved through delivery contracts for refugee and asylum seeker accommodation and support? • Are adequate standards upheld in terms of quality, non-discriminatory and respectful care for all refugee and asylum seeker groups? • Are there effective systems and processes in place to identify the most vulnerable and ensure their needs and requirements are met, including safeguarding standards and gender-sensitive approaches? • How has the Home Office learned from previous scrutiny reports to improve delivery of in-donor refugee support? |

| Coherence: How well are different parts of the UK government working together to minimise the impact that sharp increases and fluctuations in spending on refugees in the UK have on the planning and delivery of the UK’s international development and humanitarian programming? | • How well do UK government departments forecast and communicate on in-donor refugee support costs and manage volatility in the context of the aid-spending target? • How well has the UK government managed disruption in the UK aid programme caused by the sharp rise in in-donor refugee support costs? |

Methodology

The methodology for the review has six components, which together will allow evidence to be triangulated and the analysis to be informed by a range of tools and perspectives.

Strategic review: The strategic review will consist of a combination of document review and key informant interviews and will include six elements:

- Map changes over time in relevant factors including changes to asylum policy, ODA methodology (especially on eligibility), spending departments, and ODA cost per refugee/asylum seeker, 2015-22.

- Map UK ODA strategies, priorities and relevant international commitments, and check relevance of spending on in-donor refugee support against these.

- Map, through document review and interviews, each of the refugee resettlement schemes and Homes for Ukraine, plus historical resettlement schemes, 2015-22.

- Review existing scrutiny of this ODA spend and related activities, map recommendations by NAO and PAC, and follow up on implementation of ODA-relevant recommendations.

- Record the historical debate among DAC donors on whether and how in-donor refugee costs should be ODA-eligible, and the UK’s role and position in this debate.

- Map and review implications for the transparency, predictability and reliability of UK aid of the budget volatility caused by sharp rises and fluctuations in in-donor refugee support costs.

Procurement review: We will analyse the procurement, contract management and oversight of the current asylum seeker support and accommodation contracts and assess any follow-up on NAO and PAC recommendations on value for money and quality of support for refugees and asylum seekers. A sample approach will be taken due to time and resource constraints.

Site visits to local authorities: We will undertake key informant interviews and/or focus group discussions during short site visits, aiming to meet with local authorities, private service providers and civil society and community groups working with refugees and asylum seekers.

Stakeholder roundtables: We will undertake two roundtable discussions with key stakeholders and experts among civil society, practitioners and researchers.

Engagement with affected people: While ICAI’s rapid reviews do not usually include engagement activities with affected people due to the short timeframe of the review, we will aim to undertake some focus group discussions with refugees who have received support through ODA-funded schemes.

Benchmarking exercise: We will conduct a benchmarking exercise of the UK approach to in-donor refugee support against ten other DAC donors. The benchmarking will be in two parts: (i) a quantitative exercise mapping the UK and ten other donors against a set of quantitative indicators drawn from the DAC database and other internationally comparable data sets; and (ii) a qualitative comparison of a subset of donors along a further set of indicators.

Timeline

The rapid review will take place over a six-month period, beginning in September 2022, with publication planned for March 2023.