UK aid to Afghanistan

Score summary

UK aid to Afghanistan lacked a credible and realistic approach to its central goal of building a viable Afghan state. While it provided valuable support to Afghan citizens, including women and girls, it failed to make substantial progress towards its strategic objectives.

Over two decades, the UK disbursed nearly £3.5 billion in aid to stabilise Afghanistan and build a functional state. We find that the UK’s approach contained a number of flaws. It did not rest on a viable and inclusive political settlement, resulting in a long-running counter-insurgency campaign against the Taliban that undermined the legitimacy of the state-building process. The UK’s first priority was to support the US in its military campaign, which led to poor choices on the use of aid. Channelling funding in such high volumes through weak state institutions distorted the political process and contributed to entrenched corruption. The creation of a parallel institutional structure to manage international aid drew capacity away from the Afghan administration. The UK government provided over £400 million in aid over six years to fund the Afghan security services, including paying the salaries of the Afghanistan National Police, who were engaged primarily in counter-insurgency operations against the Taliban. This did not improve the quality of civilian policing, and implicated the UK aid programme in criminality and human rights abuses.

The UK also supported the delivery of basic services and development programmes to the Afghan population, mainly through multilateral partners. This improved access to health services and education (including for girls), expanded infrastructure (for example, power, electricity and irrigation), and promoted agriculture and livelihoods. Large numbers of Afghans benefited directly, and there were some improvements in health outcomes, literacy and other development indicators. However, deteriorating economic conditions, declining security and recurrent drought over the period resulted in increased poverty and food insecurity. Empowering women and girls was a strong focus for UK aid. There were successful pilots on attracting excluded girls back into education and providing services to victims and survivors of gender-based violence, as well as efforts to reform restrictive laws and social norms. While significant numbers of girls and women benefited directly, progress in tackling gender inequality was still at an early stage. Over the period, the UK increased its levels of humanitarian support, helping large numbers of people, but there was limited investment in building resilience in the face of recurrent humanitarian crises.

The review awards an overall amber-red score for UK aid to Afghanistan, on the basis of unrealistic objectives, flawed approaches and limited evidence of progress towards its strategic objectives.

Individual question scores

| Relevance: How well did the UK aid portfolio respond to Afghanistan’s humanitarian and development needs and the UK’s strategic objectives? |  |

| Effectiveness: How effectively did the UK aid portfolio deliver against its strategic objectives in Afghanistan? |  |

| Coherence: How internally and externally coherent has the UK’s work been in Afghanistan? |  |

Acronyms

| Acronym | Definition |

|---|---|

| ACBAR | Agency Coordinating Body for Afghan Relief and Development |

| ANATF | Afghanistan National Army Trust Fund |

| ANP | Afghanistan National Police |

| ARTF | Afghanistan Reconstruction Trust Fund |

| CDC | Community Development Council |

| CSO | Civil society organisation |

| CSSF | Conflict, Stability and Security Fund |

| EU | European Union |

| DFID | Department for International Department |

| FCDO | Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office |

| FCO | Foreign and Commonwealth Office |

| GBV | Gender-based violence |

| ICAI | Independent Commission for Aid Impact |

| ICRC | International Committee of the Red Cross |

| IMF | International Monetary Fund |

| K4D | Knowledge for Development |

| LOTFA | Law and Order Trust Fund for Afghanistan |

| MOIA | Ministry of Interior Affairs |

| NATO | North Atlantic Treaty Organisation |

| NGO | Non-governmental organisation |

| OCHA | Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs |

| ODA | Official development assistance |

| OSJA | Overseas Security and Justice Assessment |

| SIGAR | Special Inspector General for Afghanistan Reconstruction |

| TPM | Third-party monitoring |

| UN | United Nations |

| UNDP | United Nations Development Programme |

| UNFPA | United Nations Population Fund |

| UNICEF | United Nations International Children's Emergency Fund |

Executive summary

Over the past two decades, the UK took part in an ambitious international effort to stabilise Afghanistan and build a functional state, providing nearly £3.5 billion in aid. That effort came to an abrupt end in August 2021 with the withdrawal of international military forces and the takeover of Kabul by the Taliban. While UK officials have now left Afghanistan, the UK continues to provide emergency support through partners in response to an escalating humanitarian crisis.

This country portfolio review covers UK aid to Afghanistan during the period from 2014 to the fall of Kabul in 2021. It assesses whether the country portfolio was relevant to the country’s needs and based on credible and realistic goals, whether it was coherent across the UK government and with international partners, and what progress was being made towards its objectives. We look in particular at three of those objectives: building a viable Afghan state, empowering women and girls, and meeting humanitarian need.

This is an unusual context for an ICAI review, in that many of the results of UK aid are now at risk of reversal under Taliban rule. We are not seeking to assess the long-term impacts of past UK aid in this new and rapidly evolving context. Our purpose is rather to assess the relevance, effectiveness and coherence of UK aid before the Taliban takeover, and to capture some of the rich body of lessons from the UK’s long experience in Afghanistan. ICAI’s remit is limited to UK aid. While this review necessarily touches on the wider political and security context of international intervention in Afghanistan, it is not our intention to comment on political or military decisions.

Relevance: How well did the UK aid portfolio respond to Afghanistan’s humanitarian and development needs and the UK’s strategic objectives?

The core objective of UK aid to Afghanistan was to promote stability by building a viable Afghan state. The UK followed a state-building approach that had been used in past interventions, particularly in the Western Balkans in the 1990s and 2000s, at a time of heightened confidence in the capacity of the international community to remake war-torn states. It reflected UK government guidance on state-building at the time and was aligned with the UK National Security Council objective of countering security threats to the UK. It also enjoyed broad support from the Afghan public, which saw the state as protection against insecurity and lawlessness.

However, there were flaws in the state-building approach that contributed to its eventual failure. These flaws were common to the international mission in Afghanistan, in which the US was the dominant influence. Despite misgivings about the US approach, the UK chose to prioritise the transatlantic alliance, rather than chart a different course. The US decided at an early stage to exclude the Taliban from the political process and instead pursue a military victory over them. As a result, the state-building project did not rest on a broad political agreement to make it legitimate among Afghan elites and the Afghan public, on whose support it depended. The Taliban’s exclusion led to a long-running insurgency that intensified over the review period. As the international community increased its support to the Afghan state to conduct counter-insurgency operations, the ‘softer’ state-building objectives of promoting democracy and the rule of law took second place, further undermining the legitimacy of the state.

Security imperatives also limited the options available to the UK aid programme. The UK worked almost exclusively with the Afghan central government, with limited engagement with local institutions and political leaders. It took a largely technocratic approach to building the capacity of state institutions, focusing on their internal systems and processes, rather than their relationships with Afghan society. It also left UK aid subordinate to rapidly changing objectives and short planning horizons in the security arena, leading to unrealistic assumptions about what was achievable.

The huge scale of UK and international aid support for the Afghan state distorted the development of Afghan institutions. International support (aid and military) accounted for half of the Afghan national budget in 2020, with no prospect of reducing aid dependency in the short or medium term. This far exceeded the capacity of Afghanistan’s weak institutions to make effective use of the funds. To meet spending targets, aid funds were managed by parallel institutions staffed by consultants, which drew capacity away from the Afghan administration. The high volume of support also created intense competition among Afghan political elites to secure access to international resources, contributing to corruption and political fragmentation. By 2021, 98.7% of Afghans described corruption as a major problem for Afghanistan as a whole – up from 76% in 2014.

These dilemmas became more acute over the review period, as Taliban influence across the country increased. They were well understood and analysed by UK government officials at the time. However, the UK’s determination to provide unconditional support to the US meant that there was no attempt to reconsider the approach to state-building, even as its prospects of success receded.

The UK’s largest programme was a contribution to the World Bank-administered Afghanistan Reconstruction Trust Fund (ARTF), which received £668 million (38% of UK aid) over the review period. It supplied the Afghan government with the resources to provide basic services such as health and education, invest in infrastructure and support agriculture and livelihoods. These were relevant to Afghanistan’s many pressing development challenges. The ARTF also provided a means of financing the Afghan government’s fiscal deficit, supplying 30% of the non-military budget. The decision to direct ARTF resources through the budget reflected the view that this would help to build the legitimacy of the state. In retrospect, it might have been preferable to use a wider range of delivery channels, to avoid overwhelming state capacity.

Humanitarian conditions deteriorated over the review period, due to escalating conflict and a succession of droughts. By 2019, a third of Afghans were in acute humanitarian need and 5 million (12.5% of the population) were forcibly displaced. The UK appropriately scaled up its humanitarian support in response, from £23.5 million in 2014 (12% of the total) to £53 million in 2020 (23%). In a data-poor environment, it invested in building national capacity for humanitarian needs assessments, and was an active and informed participant in coordination bodies. However, despite the recurrent droughts, the UK remained largely reactive to humanitarian crises, investing relatively little in crisis prevention and resilience-building.

Overall, we award an amber-red score for the relevance of UK aid to Afghanistan, as its core objective of building a viable state was pursued through a flawed approach that was poorly matched to Afghan realities.

Effectiveness: How effectively did the UK aid portfolio deliver against its strategic objectives in Afghanistan?

UK aid achieved only limited progress towards strengthening the Afghan state. The ARTF directed its support via the Afghan central budget. To enable it to do so, the ARTF invested in building central government capacity in areas such as public financial management, procurement and public administration. However, the resulting gains in capacity were modest and unsustainable. The reform agenda was driven by international partners, with limited ownership by Afghan leaders. Implementation was held back by low human capacity in government agencies, while constant rotation of staff meant that any gains from training quickly dissipated. ARTF programmes were usually managed by project implementation units staffed by consultants, which drew competent personnel away from the administration. Towards the end of the review period, the UK government’s own analysis described the Afghan administration as inherently weak, and captured by a narrow political elite who benefited from international aid flows but had little interest in supporting national development.

The UK government planned to provide more than £400 million in aid over six years to fund the salaries of the Afghanistan National Police (ANP), via a trust fund managed by the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP). The Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office told us that £252 million in UK aid was ultimately spent on Afghan police and prison officer salaries. This was pursuant to a commitment the UK had made to international partners to contribute to funding the operating costs of the Afghan security forces. The ANP acted primarily as a paramilitary force, operating armed checkpoints across the country in an attempt to control the Taliban insurgency. It suffered heavy casualties, leading to low morale, desertions and attrition rates of around 25% each year. Its recruits were only lightly trained, to facilitate rapid deployment. Theft of arms and equipment was widespread and UNDP struggled to address a widespread problem with ‘ghost officers’ on the payroll. There were numerous reports from human rights organisations of police corruption and brutality, including extortion, arbitrary detention, torture and extrajudicial killings. There were also recurrent concerns about UNDP’s management of the trust fund. The UK nonetheless chose to honour its international burden-sharing commitment. UK support for police salaries helped protect Afghan communities from Taliban incursions, and may have reduced the need for ANP officers to demand bribes from citizens. However, there was limited progress in improving civil law enforcement, as the ANP did not develop a substantial civilian policing role, making it a questionable use of the aid budget. We found evidence of a number of attempts at senior levels to terminate the support, which were overruled at the highest levels of the UK government.

UK support through the ARTF helped deliver basic services to the Afghan population. The results included expanded access to healthcare. The subsequent increases in skilled birth attendance and treatment for acute malnutrition contributed to reductions in maternal, infant and child mortality. The ARTF built schools in remote areas and, by 2019, its support had enabled 4.3 million children (including 1.6 million girls) to attend school regularly. There were improvements in literacy, including for girls, although gender disparities remained wide. The ARTF was a significant investor in infrastructure, helping to expand access to electricity, water, sanitation and all-season roads. There is some evidence that its investments in agriculture and rural livelihoods helped to reduce poverty in remote areas. The ARTF struggled to measure the development outcomes attributable to its interventions, but is nonetheless likely to have delivered tangible benefits to Afghans on a significant scale. However, declining economic and humanitarian conditions meant that, while there were some periods of improvement, overall poverty rates increased over the review period.

Empowering women and girls was a significant focus of UK aid throughout the review period. This was a challenging undertaking, given Afghanistan’s ranking of 157th out of 162 countries for women’s equality. The UK funded some innovative pilot programmes designed to attract excluded girls in remote communities back into education, and to develop models for supporting victims and survivors of gender-based violence. These produced promising evidence on approaches that could work in the Afghan context, but there was no mechanism to take them to scale. The UK used its position as a major ARTF funder to push for initiatives for women and girls across its portfolio. Its advocacy efforts contributed to reforms to government policies, laws and institutions, although the practical impact for women was limited by a lack of government ownership and implementation capacity. It sought to promote social norm change, including by educating men and boys, working with religious and community leaders and media organisations to spread messages about women’s rights, and highlighting the achievements of female role models, including parliamentarians, civil servants, business leaders and army officers. We find that the UK’s support is likely to have made a significant difference to the substantial numbers of Afghan women and girls who benefited directly, but progress towards its strategic objectives of strengthening girls’ education and women’s participation in the economy and public life was still at an early stage. Amid widespread concerns that the benefits have been lost under the Taliban, some of the experts we spoke to were cautiously optimistic that the efforts of the UK and its partners had helped create lasting pressure for social change.

The UK generally made effective use of multilateral delivery partners, which offered technical strength, strong systems for managing fiduciary risks (that is, risks of improper use of UK aid funds), and the capacity to operate across the country. However, there were persistent concerns about high management costs within their lengthy supply chains, and the UK did not always commit enough resources to the relationships to address operational weaknesses when they emerged. The UK had relatively strong processes for managing fiduciary risks. However, it performed less well on its commitment to avoid inadvertently exacerbating local conflicts (‘do no harm’). Much of the ARTF programming implemented during the review period was not based on analysis of local conflict dynamics, while the UK’s own risk assessments identified a high risk that ANP officers paid through UK aid funds might engage in criminal conduct and human rights abuses. The UK put considerable effort into programme monitoring, including using third-party monitors to verify results, but lacked systems for tracking progress towards its strategic objectives for the country portfolio as a whole.

We award UK aid to Afghanistan an amber-red score for effectiveness, in the face of limited evidence of progress towards its strategic objectives, while noting some positive achievements on basic services and support for women and girls.

Coherence: How internally and externally coherent has the UK’s work been in Afghanistan?

The UK conducted high-quality analysis of Afghanistan’s changing context, which was updated regularly. However, given short staff postings and high turnover, it did not invest sufficiently in knowledge management and learning. As a result, the UK country team suffered from continuous loss in contextual knowledge and institutional memory, which affected the quality of its partnerships and programme management.

UK government departments generally worked together well, with close collaboration on aid programmes and shared challenges. However, relationships between the embassy in Afghanistan and UK government counterparts in London were not always as effective. Key decisions were often made at ministerial or Cabinet Office level, sometimes without seeking the advice of expert staff in-country. A prominent example was the decision to continue UK funding for police salaries, to maintain the transatlantic relationship, despite concerns at a senior level as to whether this was a suitable use of the UK aid budget.

As with other donors, UK aid to Afghanistan was provided within strategic parameters set by the US. This shaped the options available to UK aid – for example, by making it imperative to provide large-scale, open-ended support to the Afghan central government and security forces, and by limiting the ability to pursue a broader political settlement. US strategic objectives changed considerably over the period, reflecting variations in the US appetite to remain engaged, and often came with unrealistic timetables. This translated into some unrealistic objectives and timetables for UK aid, and made it difficult for the UK to alter its strategy, even as conditions in Afghanistan deteriorated and its objectives appeared increasingly unattainable. Ultimately, the February 2020 US agreement with the Taliban, setting a timetable for the unconditional withdrawal of US troops, made it necessary to abandon most of the objectives of the UK aid programme, despite heavy sunk costs.

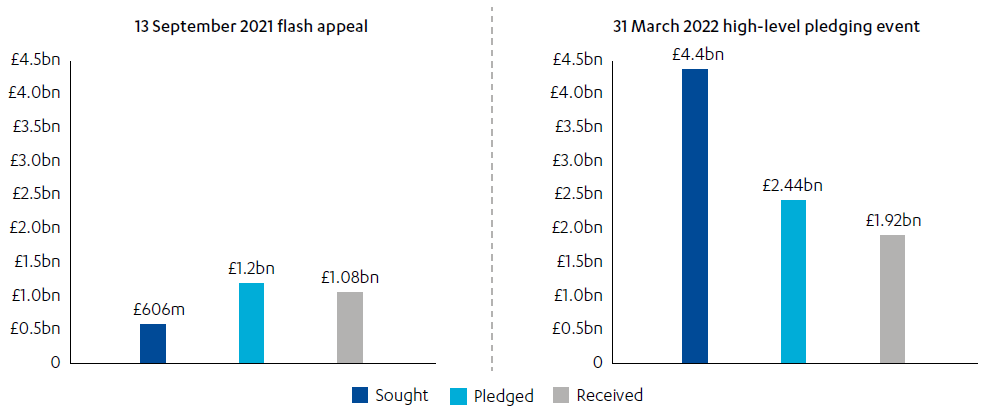

The UK was well regarded among international partners in Afghanistan. It used its diplomatic influence to promote joint international action on Afghanistan, including by hosting international conferences in 2014 and 2016. It was an active and informed participant in donor coordination bodies, and used its influence with multilateral agencies to drive up the quality of international support. Relationships with Afghan political leaders were often challenging and, towards the end of the review period, UK aid staff in Afghanistan lacked the necessary experience in policy dialogue and advocacy.

Overall, we award the UK a green-amber score for coherence, on the basis that the elements within the control of those responsible for UK aid were largely coherent.

Recommendations

The report captures a range of important lessons, both positive and negative, from UK assistance to Afghanistan, and offers three recommendations for future stabilisation efforts.

Recommendation 1

In complex stabilisation missions, large-scale financial support for the state should only be provided in the context of a viable and inclusive political settlement, when there are reasonable prospects of a sustained transition out of conflict.

Recommendation 2

UK aid should not be used to fund police or other security agencies to engage in paramilitary operations, as this entails unacceptable risks of doing harm. Any support for civilian security agencies should focus on providing security and justice to the public.

Recommendation 3

In highly fragile contexts, the UK should use scenario planning more systematically, to inform spending levels and programming choices.

Introduction

1.1 In 2001, following the 11 September al-Qaeda attacks on the US, the UK took part in an international military coalition that overthrew the Taliban regime. Over the next two decades, it worked with the US and other international partners on an ambitious project to build a stable and functional Afghan state, and thereby eliminate threats to international security. That effort came to an abrupt end in August 2021 with the withdrawal of international forces and the takeover of Kabul by the Taliban. In the intervening period, the UK spent nearly £3.5 billion in development and humanitarian aid in Afghanistan, with annual spending peaking at around £370 million in 2019.

1.2 The Taliban takeover and the international withdrawal have come at great cost to Afghanistan’s citizens and economy. The events led to a rapid deterioration of an already dire humanitarian situation, leaving an estimated 24.4 million people (around 55% of the population) in need of humanitarian aid. While the UK has withdrawn its diplomats and aid officials from Afghanistan, it continues to contribute to humanitarian relief and has worked with other donors to unlock multilateral funding for basic services.

1.3 This country portfolio review looks at UK aid to Afghanistan during the period from 2014, when British troops ended their combat role in Helmand province, until August 2021. It assesses whether UK aid was based on credible and realistic goals, given the country’s evolving needs, and to what extent it made meaningful progress towards those goals. It explores whether UK aid was coherent across the UK government and with international partners. We also provide a brief, non-evaluative account of UK humanitarian aid since August 2021 (see Annex 2). Our review questions are set out in Table 1.

1.4 This is a highly unusual context for an ICAI review. The Taliban takeover (which took place as the review was getting under way) and the suspension of most international development assistance means that many of the objectives of the UK aid programme have been abandoned for the foreseeable future. This has come about through circumstances beyond the control of the UK aid programme – primarily through the conclusion of a February 2020 agreement between the US government and the Taliban on the withdrawal of US forces. However, the situation raises important questions about UK aid to Afghanistan up to that point, given the enormous scale of the investment. It remains relevant to ask whether UK aid was guided by realistic objectives and plausible strategies at the time that it was programmed, and whether it had succeeded in delivering meaningful results before the international withdrawal.

1.5 ICAI’s remit is limited to reviewing the use of the aid budget. While this review necessarily touches on the wider political and security context, it is not our intention to comment on political or military decisions. The main purpose of this review is to generate lessons for the future use of UK aid for stabilising war-torn countries.

1.6 ICAI would like to pay tribute at the outset to the extraordinary efforts made by so many UK staff and partners – both Afghan and UK nationals – on the aid programme over the 20-year period, often at considerable personal risk, and to the 457 UK service personnel who lost their lives in Afghanistan seeking to create the conditions for peace.

Table 1: Our review questions

| Review question | Sub-question |

|---|---|

| 1. Relevance: How well did the UK aid portfolio respond to Afghanistan’s humanitarian and development needs and the UK’s strategic objectives? | • To what extent was UK aid to Afghanistan guided by credible and realistic objectives and strategies? • How well did the UK understand and respond to the development, humanitarian and peacebuilding needs and priorities of the people of Afghanistan, especially vulnerable groups? • How well did the UK adapt its approach to the evolving context in Afghanistan? |

| 2. Effectiveness: How effectively did the UK aid portfolio deliver against its strategic objectives in Afghanistan? | • How well did the UK aid programme deliver against its intended outcomes? • How well did the UK aid programme monitor its results? • How effectively did UK aid support women and girls? • How well did the UK use different delivery channels and manage the risks? |

| 3. Coherence: How internally and externally coherent has the UK’s work been in Afghanistan? | • How well did the UK build partnerships with, and influence, other governments, civil society, multilateral agencies, and other actors? • How clear was the division of responsibilities between different UK departments and agencies and how well did they work together? • How well has the UK learned from other governments and partners, and how has it disseminated its own learning to others? |

Methodology

2.1 This is a country portfolio review, examining the totality of UK aid to Afghanistan during the period from 2014 to August 2021, including programming through multilateral partners. It is a strategic assessment, looking at the extent to which the portfolio achieved its overall objectives. It looks at three of those objectives in particular: building a viable Afghan state (hereafter, referred to as ‘state-building’), empowering women and girls, and responding to humanitarian need. While the UK’s approach and portfolio evolved over the period, these were consistently among its chief objectives. The review also assesses the UK’s choice of delivery channels, including its use of and engagement with multi-donor trust funds.

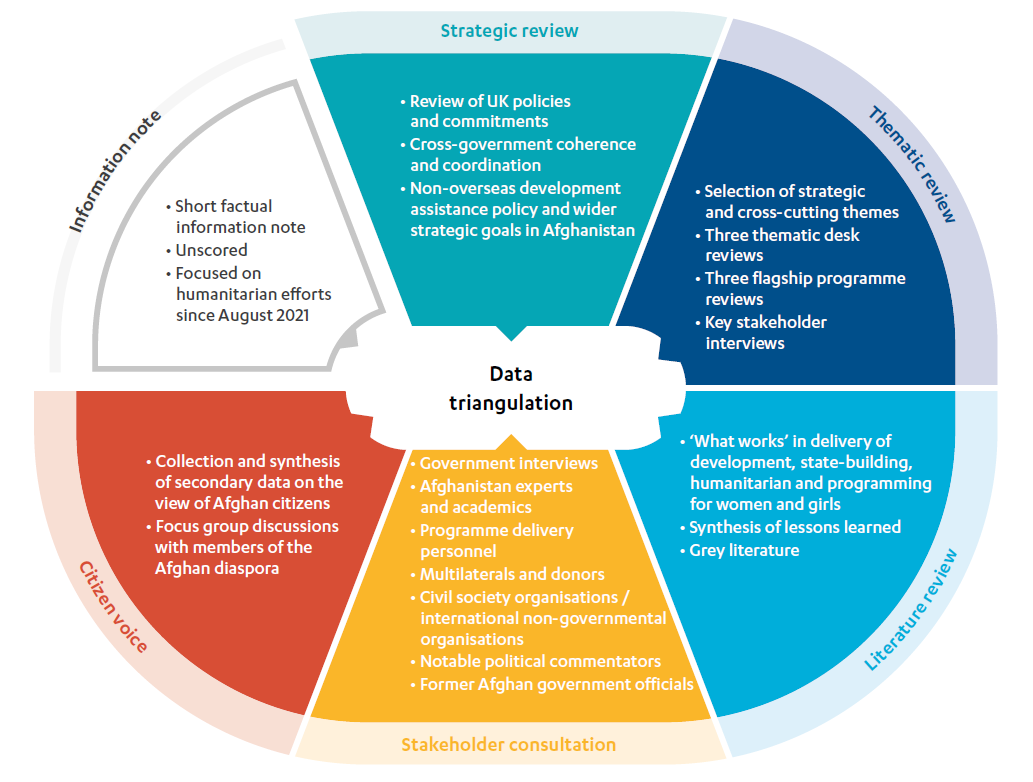

Figure 1: Our methodology

2.2 The methodology involved the following components.

- Strategic review: We undertook a desk-based mapping of relevant policies, strategies and guidance, a broader document review, and key informant interviews with relevant UK government staff, particularly from the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO), supplemented by interviews with academic experts and other development partners.

- Thematic review: We explored a selection of strategic and cross-cutting themes across the UK portfolio and within a selection of flagship programmes. We assessed how well the portfolio as a whole contributed to three strategic objectives: i) state-building, ii) empowering women and girls, and iii) responding to humanitarian need. The individual programmes that we assessed under each theme are listed in Annex 1.

- Literature review: Our literature review is published separately and forms part of the evidence used to inform our assessment. It provides an overview of the most important published and grey literature (including documents published by the major bilateral and multilateral institutions active in Afghanistan) on the international approach to stabilisation in Afghanistan.

- Stakeholder consultation: We conducted stakeholder consultations and interviews with current and former personnel who worked for the UK in Afghanistan over the review period, programme delivery personnel, Afghanistan experts, academics, independent contractors, multilateral counterparts, other donors, international and Afghan non-governmental organisations, and notable political commentators.

- Citizen voice: As security conditions made it risky to conduct research with citizens inside Afghanistan, we undertook focus group discussions with Afghans in the diaspora in lieu of our usual citizen engagement. These focused on key informants, such as former Afghan government officials and staff working with the UK government and its implementing partners on UK aid programmes. We also collected and synthesised secondary data on how the views of Afghan citizens evolved over the review period.

- Information note: A short, factual information note forms an annex to this review, covering UK aid spending on humanitarian assistance to Afghanistan since the international military withdrawal in August 2021.

2.3 Full details of the methodology and sampling approach are provided in the approach paper, available on the ICAI website.

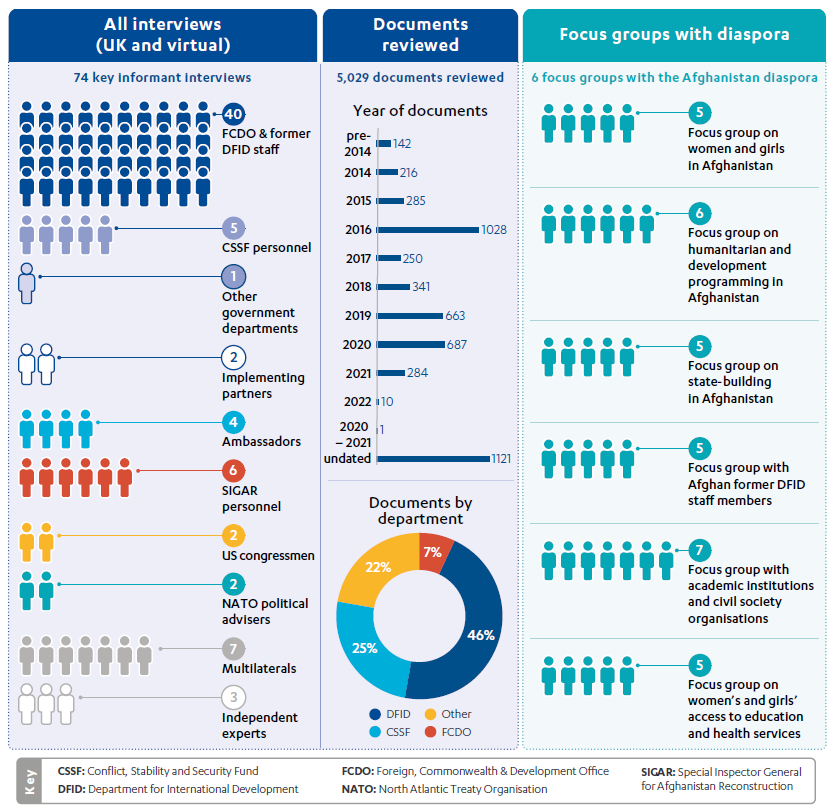

Figure 2: Breakdown of stakeholder interviews and documents reviewed

Box 1: Limitations to our methodology

This review methodology was subject to a number of limitations.

- Lack of field research: The international withdrawal and the takeover of government by the Taliban occurred during our review, leading to a rapidly deteriorating security situation. The UN offered to facilitate a visit by ICAI to Afghanistan, as it has done for officials from other donor countries, but FCDO did not approve this, citing, as reasons, the security situation in the country at the time and the duty of care it holds for ICAI staff. FCDO accepted that its attitude was more risk-adverse than that of other countries which had visited under the UN’s protection, and agreed to reconsider an ICAI visit at a later date. Our interviews with UK government officials and partners were conducted either remotely or after their return to the UK. ICAI is committed to hearing the voices of citizens affected by UK aid. We discussed with three research organisations in Afghanistan the feasibility of them conducting research with citizens on our behalf, but ethical concerns about levels of risk to both participants and researchers and other practical difficulties prevented this. In lieu of direct citizen engagement, we conducted key informant interviews with Afghan professionals in the diaspora and collected data from secondary sources on the evolution of Afghan citizens’ views over the review period.

- Data on effectiveness: Our assessment of the effectiveness of UK aid depends primarily on results data generated by programme monitoring and evaluation systems. To the extent possible, we have triangulated these through key informant interviews, published sources and feedback from Afghan professionals in the diaspora. We also conducted our own assessment of the credibility of the available results data. However, declining security conditions in Afghanistan during the review period meant that those responsible for managing UK aid programmes had limited capacity to verify the results generated by implementing partners. Afghanistan is also a data-poor environment, lacking reliable official statistics (including census data), which makes it challenging to assess results at outcome level. Our conclusions on effectiveness are subject to appropriate caveats.

Background

3.1 Afghanistan is a landlocked, multi-ethnic country in south-central Asia. Its estimated population of 41.7 million is three-quarters rural and widely dispersed across a vast territory, much of it remote, mountainous and arid. The capital, Kabul, is one of the world’s fastest growing cities; its population of 4.8 million has increased fourfold since 2001.12 Afghanistan has a young population, with 47% under the age of 15. It is also ethnically diverse: the Pashtun tribes make up the largest ethnic group, with an estimated 42% of the population (including the nomadic Kuchi group), followed by Tajiks (27%), Hazaras (9%), Uzbeks (9%), Aimaq (4%), Turkmen (3%) and Baluch (2%). While Islam is practised by the majority of the population, Afghanistan has diverse religious and cultural traditions, which in turn shape attitudes towards the state, gender roles and the outside world. The country has been war-torn for four decades, with a history of foreign invasions and civil conflict among its tribal and ethnic groups.

3.2 Afghanistan first emerged as a political entity in the 18th century and became an independent state after the First World War, under a Pashtun monarchy. Armed resistance against external invaders – including three wars against the British – in the preceding century helped create the conditions for unification. However, Afghanistan’s tribal groups continued to enjoy high levels of autonomy, with diverse customary systems of local government.

3.3 In the 1970s, Afghanistan went through a period of social reform under a Soviet-backed People’s Democratic Republic. This was overthrown in 1978, triggering a decade-long Soviet military occupation. The ‘Mujahidin’ armed insurgency against the Soviets, which enjoyed extensive Western support, adopted conservative Islam as its unifying ideology and opposed interference from both sides of the Cold War. The conflict led to the displacement of millions of refugees and the exodus of most of the country’s educated elite, leaving Islamic education through mosques and madrasas in a dominant position.

3.4 In the civil conflict that followed the Soviet withdrawal in 1989, an Islamic fundamentalist group, the Taliban, gained control of nearly two-thirds of the territory. The Taliban (the name means ‘students’ in Pashto) began as a group of students and scholars committed to fighting crime and corruption. They took a strict approach towards the enforcement of Sharia law, sharply curtailing civil liberties – especially for women and religious minorities – but also winning a degree of public support for their efforts to restore law and order. The Taliban permitted al-Qaeda to operate on their territory, and the 11 September 2001 terrorist attacks against the US were planned from Afghanistan. The Taliban’s refusal to extradite the al-Qaeda leader, Osama bin Laden, led to the US-led invasion of Afghanistan later that year, supported by the ‘Northern Alliance’ group of resistance fighters. This resulted in the fall of the Taliban and the establishment of the International Security Assistance Force led by the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation (NATO) in 2001.

3.5 The international mission to stabilise and reconstruct Afghanistan, which ran from 2001 to August 2021, found a country left fragmented and bitterly divided by the long legacy of conflict. State institutions were heavily degraded and had to be rebuilt almost from the ground up. The underdeveloped formal economy was dwarfed by an illicit economy of drugs and arms trafficking, and most Afghans made a living from smallholder agriculture. The international mission faced a continuing armed insurgency from the Taliban, which operated across the Pakistani border and enjoyed substantial financial and logistical support from backers within Pakistan. In 2010, the US government ‘surged’ an additional 30,000 troops into Afghanistan, with the goal of stabilising the situation before handing over security responsibilities to the Afghan security services in 2014. NATO leaders pledged continuing international financial, material, logistical, training and advisory support through the Resolute Support Mission, with around 18,000 international troops remaining in Afghanistan.

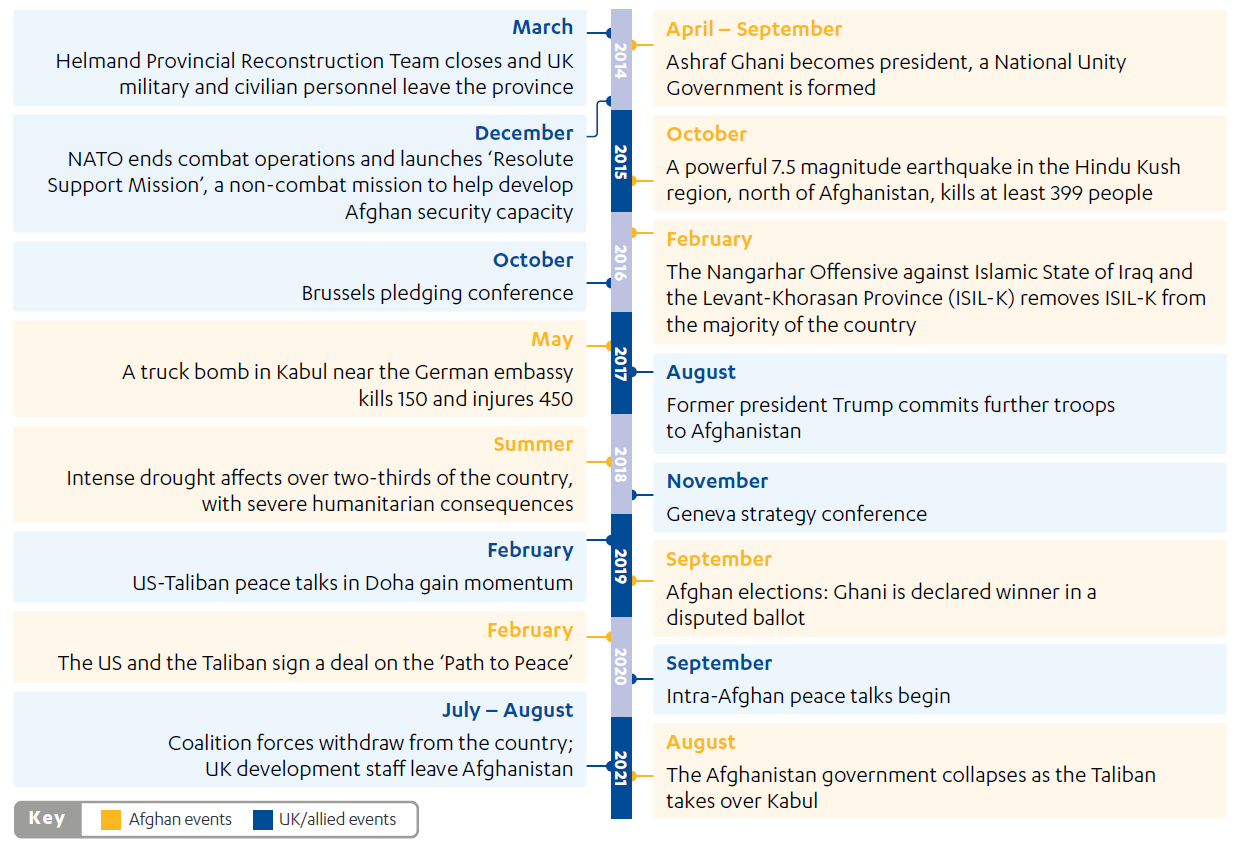

Figure 3: Timeline of important events in Afghanistan during review period

Source: ICAI research.

3.6 The 2014 to 2021 period, which is the focus of this review, saw increasing instability at both the political and the security level as resistance grew to the attempted centralisation of power in the Afghan state. Attacks on Afghan security forces and the international mission grew steadily in intensity and an increasing share of the territory fell under Taliban control. A 2014 general election had led to a powersharing agreement and the formation of a National Unity Government under President Ashraf Ghani, but by 2017 this had fallen into dysfunction and factionalism. In 2017, a massive car bomb attack near the German embassy killed 150 people and wounded another 450, leading to sharp reductions in the international civilian presence. New elections in 2019, with low voter turnout, returned Ghani to office, but disputes over the result raised questions about the legitimacy of the government and the electoral process itself.

3.7 On 29 February 2020, the US government concluded an agreement with the Taliban which put in place a timetable for the withdrawal of US forces. The Afghan government was not a party to the agreement. Intra-Afghan peace talks were held in Doha from September 2020, but failed to reach an accord. By this point, the Taliban were rapidly gaining control of the territory and had little incentive to conclude a peace agreement. The Afghan security forces presented little resistance, which commentators linked to low morale, poor leadership, extensive corruption and the withdrawal of air cover and logistical support by the departing US forces. On 15 August 2021, President Ghani fled the country and the Afghan government collapsed, leaving the Taliban to take control and bringing a definitive end to the 20-year international mission to stabilise Afghanistan.

The development and humanitarian context

3.8 Forty years of instability have left Afghanistan one of the poorest and most fragile countries in the world. There are multiple drivers of conflict and instability. External support for insurgent groups over an extended period has created incentives for conflict rather than compromise. Ethnic and tribal divisions have been exacerbated by long-running conflict. State institutions are weak, and competition among political elites to gain access to budgetary resources, public procurement contracts and other ‘rents’ of public office has led to pervasive corruption and chronic political instability. Conflict is fuelled by a large illicit economy: Afghanistan produces 85% of the world’s opium, generating an estimated income of between £1.5 billion and £2.2 billion in 2021, equivalent to 6-11% of gross domestic product. Afghanistan is also highly vulnerable to natural disasters and extreme weather, with droughts and flooding increasing in frequency and intensity through the effects of climate change.

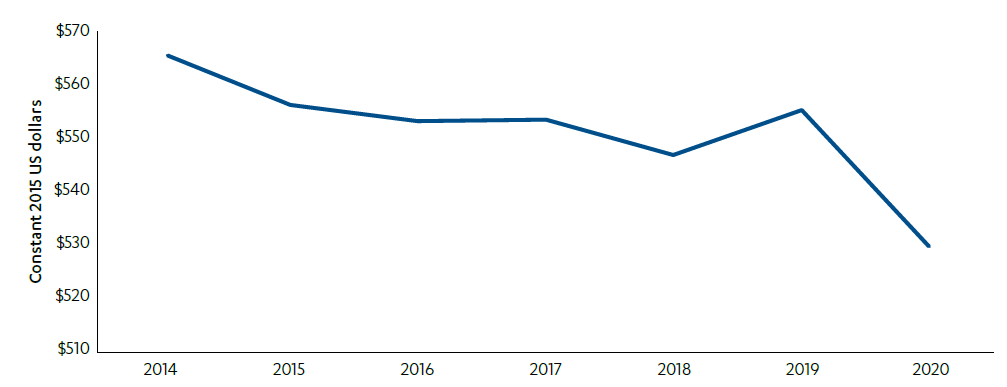

3.9 The formal economy is small and undiversified, representing around 20% of economic activity and leading to a small tax base. Official unemployment stood at 18.6% in 2019-20, but most Afghan workers are in insecure and poorly paid jobs in the informal sector, with 49.4% of the labour force estimated to be in vulnerable employment. The economy grew at an average of 9% per year between 2003 and 2014, linked to high levels of international civilian and military expenditure. Gross domestic product per capita fell from $565.2 in 2014 to $529.7 in 2020 (See Figure 4). Poverty rates increased sharply from 2011-12 into the early part of the review period and then declined gradually after 2016. By 2019, just under half the population were reported to be living below the poverty line, which was an increase of approximately 10% over the 2011-12 figures. The World Bank projected poverty rates of up to 72% in 2020, under the impact of COVID-19. In 2021, the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) warned that poverty could become “near universal” following the Taliban takeover and the withdrawal of international development aid.

Figure 4: Afghanistan gross domestic product (GDP) per capita

Source: World Bank data, 2022.

3.10 Afghanistan ranks 169th out of 189 countries in the UNDP’s Human Development Index, and its ranking has changed little over the past decade. Life expectancy has increased to 65 years, up from 63 in 2014. There are no accurate data on school enrolment and completion rates, but adult literacy has increased from 34.8% in 2016-17 to an estimated 43% in 2020, with 65% literacy among 15-to-24-year-olds. Although this is notable progress, it includes huge gender disparities: literacy stands at 55% for men, but only 29.8% among women. According to the United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund, of the 3.7 million children who are out of school in Afghanistan, 60% are girls. Maternal mortality has fallen in recent years, but it remains one of the highest rates in the world, at 638 per 100,000 live births. In 2019, Afghanistan ranked 157th out of 162 countries for gender equality.

3.11 The humanitarian situation deteriorated over the review period as a result of rising insecurity and recurrent drought. In 2019, 15.9 million Afghans (nearly 45% of the population) were chronically food insecure. In mid-2022, a year after the Taliban takeover, 24.4 million people, or 55% of the population, are in acute need of humanitarian assistance. It is estimated that there are more than 2.6 million Afghan refugees worldwide, and an estimated 5.5 million have been displaced by conflict and disasters inside the country since 2012.

UK aid to Afghanistan

3.12 Between 2002 and 2021, the UK provided £3.5 billion in aid to Afghanistan. This represented 7% of total global aid to Afghanistan during the period. According to data from the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development’s Development Assistance Committee, the UK is the third-largest bilateral donor to Afghanistan, after the US and Germany.

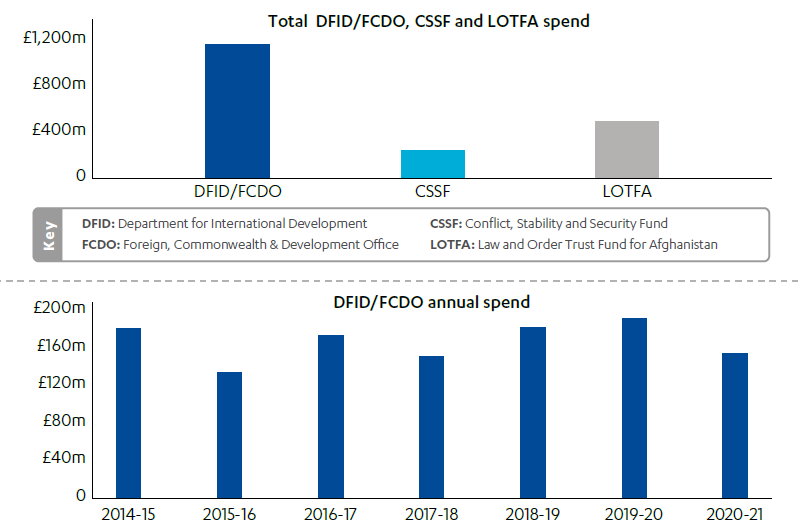

Figure 5: UK official development assistance to Afghanistan by department, 2014-21

Source: Top graph derived from FCDO and CSSF management data supplied to ICAI, unpublished; Bottom graph derived from FCDO management data supplied to ICAI, unpublished.

Note: The top graph uses FCDO financial data rather than Statistics on international development data to capture DFID/FCDO spend in the financial years in our review period. At the time of publication, Statistics on international development data were only available up to the end of calendar year 2020. The 2021 data presented in this chart do not therefore represent a final figure.

3.13 This was a major commitment of resources: Afghanistan was the fourth-largest recipient of UK aid in 2020.46 Figure 6 shows total UK aid for Afghanistan from 2014 to 2020 through bilateral and multilateral channels. Over this period bilateral aid to Afghanistan was £1.7 billion – although as we discuss in the report, the majority of UK bilateral aid was also delivered by multilateral partners (as ‘multi-bi’ aid).

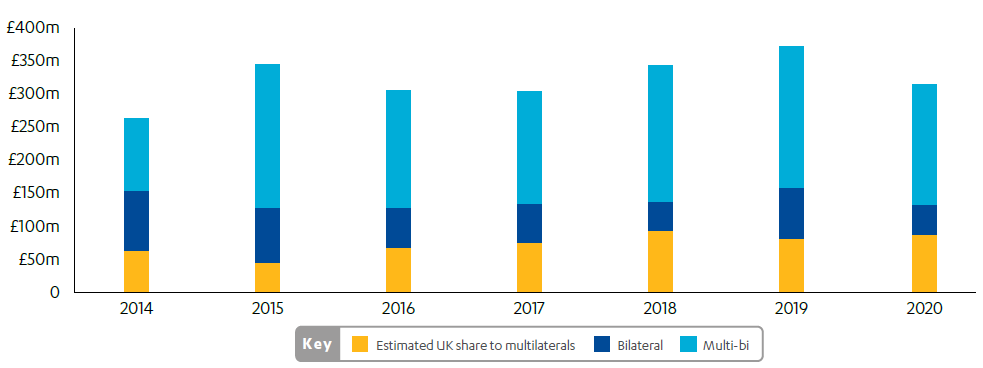

Figure 6: UK aid to Afghanistan by channel, 2014-20

Source: Statistics on international development, 2017 and 2020.

Note: Figure 6 uses Statistics on international development data rather than FCDO management data to capture official development assistance (ODA) spend across all UK aid-spending departments, including estimates of how much ODA went to Afghanistan from the UK’s core contributions to multilateral agencies.

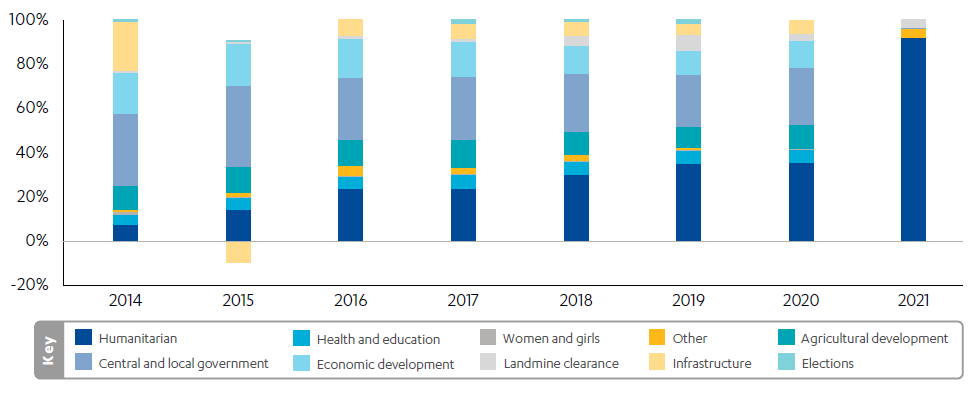

Figure 7: UK aid to Afghanistan by sector split

Source: Derived from FCDO management data supplied to ICAI, unpublished.

Notes: a) Figure 7 uses FCDO financial data rather than Statistics on international development data to capture DFID/FCDO spend in the financial years in our review period. At the time of publication, Statistics on international development data were only available up to the end of calendar year 2020. The 2021 data presented in this chart do not therefore represent a final figure.

b) Sectoral split is based on classification provided by the UK government and may not fully reflect all spending on, for example, women and girls or climate, which were mainstreamed across all programming.

c) ICAI understands that the negative value in 2015 was due to the amount recharged from funds unspent in previous years.

3.14 From 2006 to the withdrawal of international combat troops in 2014, a substantial share of UK bilateral aid to Afghanistan was spent in Helmand province, where the main UK military contingent was stationed. After the withdrawal of UK combat forces, the focus of the aid programme shifted from Helmand towards support for the central government and country-wide programming, principally through multidonor programmes managed by multilateral institutions.

3.15 The strategy that guided all UK efforts in Afghanistan during the review period, including the aid programme, was set by the UK’s National Security Council. It established two overarching, closely linked objectives: countering direct security threats to the UK and building a viable Afghan state. This was reflected in the 2015 international development strategy, in which the UK committed to “[s]upport the Government of Afghanistan in ensuring that the country remains stable and never again becomes a haven for international terrorists”.

3.16 Over the review period, other development objectives were added. A 2016 Department for International Development business plan for Afghanistan included objectives around building democracy and the rule of law, unlocking the potential of women and girls, and supporting poor and marginalised communities (‘leaving no one behind’). A 2019 update added mobilising public revenues, generating a self-sustaining economy, and strengthening resilience to humanitarian crises and climate change.

3.17 From 2015, following the withdrawal from Helmand, the UK sharply reduced the numbers of programmes it managed directly, redirecting 90% of its funding through multilateral funds. The largest share of UK aid was spent via the Afghanistan Reconstruction Trust Fund (ARTF), a multi-donor fund managed by the World Bank, which provided the Afghan central government with much of its operating budget and funded essential services and infrastructure across the country.

3.18 The UK initially pledged £70 million per year over six years, from 2015, to Afghanistan’s civilian security agencies – primarily the Afghanistan National Police – as part of a burden-sharing agreement among NATO countries. As the humanitarian situation deteriorated, the UK increased the proportion of humanitarian support in its country programmes, to 37% in 2019. The remaining bilateral spend was primarily through the multi-country Girls’ Education Challenge programme, which promoted the education of marginalised girls.

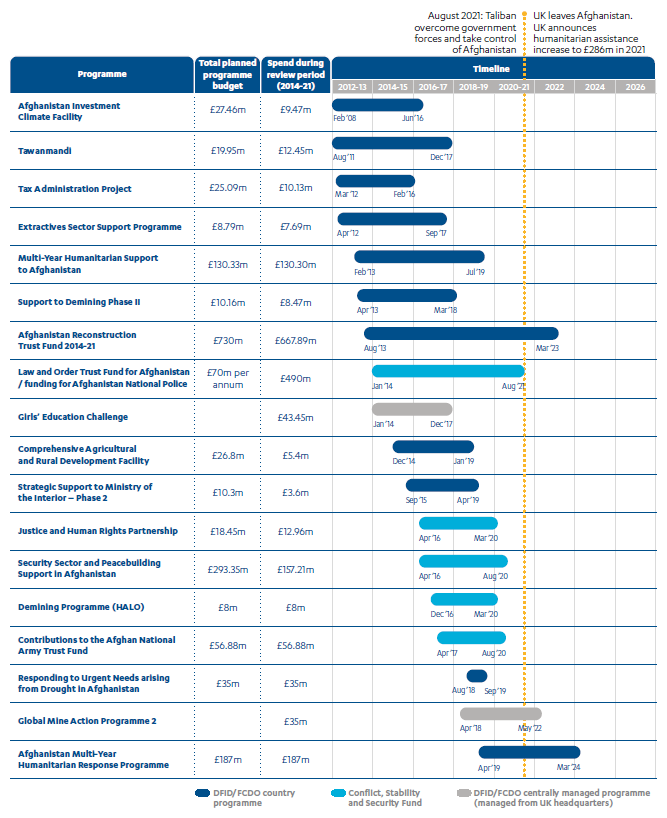

Figure 8: Timeline of UK aid programming in Afghanistan

Notes: a) Total planned programme budgets not included for centrally managed programmes as a particular country budget is not separately identifiable.

b) It is unclear whether programmes scheduled to run beyond August 2021 have continued, due to changing circumstances in the country.

c) The sample above only includes programming and spending that was planned before August 2021 as only this programming is in the scope of the review – see Annex 1 for details of funding that the UK has provided since August 2021.

3.19 Afghanistan is among the most challenging environments in which the UK has spent aid over the past decade. As the security situation deteriorated, the UK reduced the number of aid officials stationed in Afghanistan. Those that remained served on shorter rotations than other contexts and were increasingly confined to the British embassy in Kabul. Fiduciary risks (risks of aid funds being used for improper purposes) and operational risks (risks of not achieving programme objectives) were high, owing to entrenched corruption across Afghan institutions and the UK’s limited ability to supervise programmes.

3.20 Following the Taliban takeover, the UK suspended development cooperation with the Afghan government while scaling up its humanitarian assistance. In August 2021, the UK government announced a doubling of planned aid to Afghanistan, to £286 million for 2021-22, with the funds channelled through UN partners and international non-governmental organisations (NGOs) (see Table A1 for details). The ARTF, which still holds substantial funds from the UK and other donors, has likewise suspended cooperation with government, but has approved projects supporting basic services, livelihoods and food security, to be implemented by UN agencies and international NGOs.

Findings

4.1 This section presents the findings of our review regarding the relevance, effectiveness and coherence of UK aid to Afghanistan.

Relevance: How well did the UK aid portfolio respond to Afghanistan’s humanitarian and development needs and the UK’s strategic objectives?

4.2 In this section, we assess whether UK aid to Afghanistan was relevant to the country’s needs and to the UK’s strategic objectives, whether it was guided by credible and realistic objectives and strategies, and how well it adapted to the evolving context and lessons learned.

The UK approach to building the Afghan state contained some key flaws and failed to adapt to a deteriorating situation.

4.3 The core objective of UK aid to Afghanistan was to promote stability by building a viable Afghan state. This objective was set down in the National Security Council strategy for Afghanistan and articulated in successive Department for International Development (DFID) country business plans. Other key objectives for UK aid – such as building a sustainable economy and supporting marginalised groups – were pursued in partnership with Afghan central government institutions, and therefore depended on the success of the state-building project.

4.4 The UK pursued an ambitious model of state-building that had been developed in the Western Balkans (Bosnia and Herzegovina and Kosovo) in the 1990s and early 2000s, at a time of heightened confidence in the capacity of the international community to remake war-torn states. The basic elements of this approach reflected UK government guidance at the time on how to support state-building. They included:

- Agreement on an internationally brokered constitution, including protections for ethnic and religious minorities and support for elections.

- Training and equipping the security sector, including the army and police, to enable the state to project its authority across its territory.

- Support for core government functions, such as tax collection, public finances and public administration.

- Channelling of development finance through the state, to give the state the capacity to provide public services and basic infrastructure to communities, to help build its legitimacy across society.

4.5 The state-building objective was closely aligned with the security strategy being pursued by the UK and its international partners in Afghanistan, which was to build a state that would maintain stability, prevent the resurgence of the Taliban, and ensure that Afghanistan never again became a haven for terrorist groups. Many of the UK government officials we interviewed confirmed that this security rationale was the main driver of the state-building approach, making it imperative to work with central government institutions.

4.6 There is evidence to suggest that state-building enjoyed broad support from the Afghan people. A survey of Afghan public opinion in 2014, at the beginning of our review period, found that 75.3% of Afghan citizens thought that the national government was doing a ‘very good’ or ‘somewhat good’ job (see Box 2). A similar percentage (73.1%) said that they felt somewhat or very satisfied with the way democracy worked in Afghanistan, although 76% thought that corruption was a major problem for the country as a whole. A narrow majority (55%) thought that the country was moving in the right direction: ‘good security’ and ‘reconstruction/rebuilding’ were the two most commonly cited reasons for optimism. This reflects observations in the literature that many Afghans supported state-building as protection against a return to insecurity and lawlessness.

Box 2: Evolution in Afghan attitudes towards the state

The Asia Foundation undertook annual surveys of the views of Afghans across the country, providing a picture of how those views evolved over the review period.

Share of citizens who thought corruption was a major problem in Afghanistan as a whole:

2014: 76%

2021: 98.7%

Share of citizens who thought the country was going in the right direction:

2014: 55%

2019: 36.1%

Share of citizens who thought national institutions were doing a ‘very good’ or ‘somewhat good’ job:

2014: 75.3%

2019: 66.0%

Share of Afghans who were very or somewhat satisfied with the way democracy works in Afghanistan:

2014: 75.1%

2019: 65.1%

Share of Afghans willing to accept a peace deal involving a role for the Taliban in government (2021):

Male: 70.6%

Female: 45.3%

Sources: Afghanistan in 2014: A survey of the Afghan people, The Asia Foundation, 2014, pp. 95, 174 and 188; A survey of the Afghan people – Afghanistan in 2019, The Asia Foundation, 2019, pp. 279 and 312; Afghanistan flash surveys on perceptions of peace, COVID-19, and the economy: Wave 3 findings, The Asia Foundation, 2021, p. 111.

4.7 While building a viable Afghan state was relevant to both UK strategic objectives and the needs of the Afghan people, there were flaws in the approach which contributed to its eventual failure. These flaws were common to the wider international mission in Afghanistan, in which the US was the dominant influence militarily, politically and financially. Key informants confirmed that the UK had relatively little influence at the strategic level. UK officials had misgivings about elements of the strategy, and at times advocated for alternatives with their US counterparts. However, the UK ultimately chose to prioritise the transatlantic alliance by supporting the US approach, rather than charting a different course. As Professor Michael Clarke, former director-general of the Royal United Services Institute, has written, the UK’s priority was to align with the US – “good or bad, right or wrong, and through thick and thin”.

4.8 One basic flaw in the approach was the lack of a sufficiently inclusive political settlement to underpin the state-building process. The UK government has produced a range of papers and strategies on post-conflict stabilisation and state-building, capturing the experience of past interventions in the Western Balkans, Sierra Leone, Iraq, Libya and elsewhere. These documents talk at length about the importance of a viable and inclusive political settlement, to attract the support of political elites and the public, so that the state-building process is seen as legitimate (see Box 3).

Box 3: UK guidance on post-conflict political settlements

Various UK government documents stress the importance of viable and inclusive political settlements as a foundation for peacebuilding and state-building.

What is a political settlement?

“Political settlements are the expression of a common understanding, usually forged between elites, about how power is organised and exercised. They include formal institutions for managing political and economic relations… [and] informal, often unarticulated agreements that underpin a political system, such as deals between elites on the division of spoils.”

Political settlements may be engineered (negotiated through a peace process), imposed (by the victor of a conflict, and maintained through coercion) or inclusive (involving long-term negotiation between the state and groups in society, leading to rights and responsibilities that are broadly accepted).

Building peaceful states and societies: A DFID practice paper, Department for International Development, 2010, pp. 22–23.

When is a political settlement legitimate?

“States are legitimate when elites and the public accept the rules regulating the exercise of power and the distribution of wealth as proper and binding.”

Building peaceful states and societies: A DFID practice paper, Department for International Development, 2010, p. 16.

“State-building remains a crucial element for long term stability. But it must be about more than reinforcing central state institutions’ capacity to govern… Legitimacy is shaped not only by authorities’ capacity and the processes through which they relate to the population, but also by local norms, beliefs, historical grievances and expectations.”

Building stability framework 2016, Department for International Development, 2016, p. 12.

When is a political settlement stable?

“Countries and communities are more stable when different groups are included fairly within the structures of power… Building stability is above all a deeply political process of moving from exclusion and inequality towards open institutions which can manage change peacefully; and towards a way of distributing and exercising power which is accepted in the long run by both elites and wider communities… [P]ower-sharing arrangements which include the elites of different groups can reduce the likelihood of conflict and promote stability.”

Building stability framework, Department for International Development, 2016, p. 6.

“Attempts at transformative change, for example in Afghanistan, Libya and Iraq, have faced considerable challenges. Those excluded from the political and security arrangements have often used violence to challenge and undermine them and strengthen their position. This has often resulted in continued conflict, failed institution-building efforts and the collapse of peace agreements.”

The UK government’s approach to stabilisation: A guide for policy makers and practitioners, Stabilisation Unit, March 2019, p. 87.

4.9 A key plank of the US strategy for Afghanistan was the exclusion of the Taliban from the political process and the single-minded pursuit of a military victory against them.54 That strategy prevailed until February 2020, when the US government reversed its approach and concluded a peace agreement with the Taliban, to which the Afghan state institutions were not party.55 Many of the UK officials we interviewed believed that there were points in time (mainly before our review period) when the Taliban were a relatively marginal force, both politically and militarily, and could have been invited into the state-building process. Given the diversity of views and interests within the Taliban, this might have brought the more moderate Taliban leaders into the political sphere, and left the extremists further marginalised. UK government documentation and officials we spoke to were clear that a viable Afghan state could not be achieved without significant engagement with the Taliban, and this is consistent with the guidance summarised in Box 3. As it transpired, the exclusion of the Taliban led to a long-running insurgency that increased in intensity over the review period, posing a growing threat to the state-building process.

4.10 The lack of a viable political settlement left the Afghan state in the role of a combatant in a long-running conflict, and the international community pursuing “an unstable hybrid of state building and counter-insurgency”. This situation is described in UK government guidance as ‘hot stabilisation’, where development aid is used primarily to win consent for the government being supported and the international military presence. The imperative of defeating the Taliban on the battlefield at times clashed with the ‘softer’ objectives of the state-building project, such as building democracy and the rule of law. Key informants confirmed that security objectives took precedence. Within the UK aid programme, this can be seen in the decision to fund the Afghanistan National Police to conduct paramilitary operations against the Taliban, with only minimal effort to build their civilian policing capacity (see paragraphs 4.36 to 4.42 below). From 2014, the international community provided extensive support to the Afghan security forces for counter-insurgency operations. This created a political opening for the Taliban to portray state institutions as puppets of an occupying force, in an effort to co-opt nationalist sentiment against the central government. It led to a paradoxical situation where the UK was attempting to build the state in order to establish peace and security but had limited prospects of building legitimate institutions in the absence of peace and security.

4.11 The growing challenge from the insurgency, the dominance of security imperatives within the international mission, and the UK’s determination to remain closely aligned to the US limited the options available to the UK aid programme. It pushed the UK into an almost exclusive partnership with the Afghan central government, with little room to work with sub-national institutions and local political leaders to foster more legitimate local governance arrangements. It forced UK aid into a largely technocratic approach to capacity building, focused on the internal systems and processes of selected institutions, rather than their relationships with Afghan society. It also left the aid programme subject to rapidly changing security objectives and short programming cycles. There were dramatic shifts in US strategy over the period, linked to changes in the US government’s willingness to commit troops and resources to Afghanistan, and often unrealistically short timetables for achieving security objectives. Being unwilling to challenge the US approach, the UK became publicly committed to a narrative of imminent success. According to UK officials, this translated into a state-building approach that was based on unrealistic assumptions about what was achievable in short time horizons. This top-down, short-term approach to state-building is extensively criticised in the literature.

“In 2002 Afghanistan was a failed state, but huge changes came after that. However, more time and proper strategies were needed for democracy to take root. Donors, particularly the US, did not have a long-term strategy and their plans were made on a one-year basis.”

Afghan former minister, Ministry of Rural Development

4.12 Perhaps the most important flaw in the state-building approach was the sheer scale of international financial support for the Afghan state, which distorted and ultimately undermined the development of Afghan institutions. The World Bank estimates that, in 2020, international grants (both official development assistance and military support) accounted for half of the central government budget and 75% of total public expenditure – up from 60% in 2013. The Afghan state spent approximately $11 billion each year, but raised only $2.5 billion of its own resources. Despite international support for revenue collection, World Bank analysis suggested that the prospects of reducing Afghanistan’s dependence on aid in the short-to-medium term were limited, and that it would take at least 35 years to achieve self-financing, due to the weakness of the economy. The state-building strategy therefore depended on open-ended, large-scale international financial support.

4.13 While Afghanistan faced many acute development challenges, support on this scale far exceeded its ‘absorption capacity’ – that is, the amount of funding that a low-capacity administration could spend effectively. The UK and other donors were under pressure to disburse funds rapidly, while ensuring that they were used for their intended purpose. To meet these requirements, the Afghanistan Reconstruction Trust Fund (ARTF) established a large network of parallel institutions (‘project implementation units’) within Afghan ministries, staffed by well-paid international and Afghan consultants. This had the effect of drawing skilled personnel out of the Afghan public service, undermining capacity development (see paragraphs 4.43 to 4.55). At the political level, it led to the emergence of a ‘rentier’ system in which political elites competed to gain access to international resources, which in turn enabled them to cement their power and influence through patronage (the sharing of benefits with their supporters). Intense competition for access to international resources contributed to widespread corruption and the breakdown of the national unity government elected in 2014. Because Afghan political elites gained power through their access to international resources, they were largely unaccountable to their own electorates, and had little incentive to invest in collecting revenues and building effective institutions. Around the world, such ‘rentier’ political systems are associated with low economic growth, high inequality and poor development outcomes.

4.14 As the review period progressed and Taliban influence across the country increased, these dilemmas became more acute. These were well understood by the UK officials we interviewed and are analysed in internal UK government documents. However, there was no significant attempt to reassess the state-building approach and its underlying assumptions. Instead, the commitment to aligning with the US left the UK locked into investing large amounts of aid into a state-building process which its own analysis suggested had limited prospects of success. As one senior official told us, “if we’ve invested in a state-shaped object that can’t command the loyalty or support of large parts of the population, it will amount to nothing”.

“Cash was injected by donors into the government, but it caused more corruption as systems were not in place. So, as a result, a huge amount of money was spent but with very little impact.”

Former Afghan National Security Adviser

“Corruption was endemic in government due to wrong appointments by the leadership and the prevailing culture of impunity… Centralisation of power was one of the main impediments to good governance, which became even more severe after 2014 when President Ghani came to power.”

Afghan former ARTF programme manager

“Local government should be given more power; to choose a proper model for state-building, it should be done through consultation and sharing of power.”

Former Ministry of Interior Affairs staff member

The UK’s support for basic services and livelihoods through the ARTF responded to Afghanistan’s acute development needs, but overloaded the absorption capacity of the Afghan government

4.15 The UK’s main financial contribution to basic services and economic development needs in Afghanistan was through the World Bank-administered ARTF (see Box 4). The ARTF was the world’s largest multidonor trust fund, spending over £10 billion since its inception in 2002. The UK was its second-largest donor, pledging £730 million during the period from 2014 to 2022, with £688 million disbursed by the end of the review period. More than half of all UK aid to Afghanistan went through the ARTF.

Box 4: The Afghanistan Reconstruction Trust Fund

The Afghanistan Reconstruction Trust Fund (ARTF) was established to provide a dependable and predictable mechanism for on-budget financial aid68 to the Afghan government. As the primary avenue for funding development interventions at scale, it also provided an important coordinating mechanism for international donors.

The World Bank was the ARTF’s administrator, responsible for fund management, disbursement, managing implementing partners, monitoring and reporting. It was supported by a management committee, which included representatives of other multilateral agencies and the Afghan Ministry of Finance, which approved major funding decisions. Strategic direction was provided by a steering committee, chaired by the World Bank country director and the Afghan minister of finance, with donor countries represented at ambassador level. Donors were also represented on three technical advisory groups, on strategy, gender and the incentive programme (a financial instrument that supported institutional reforms).

ARTF funding was provided through two ‘windows’. The Recurrent Cost Window helped pay the Afghan government’s operating costs, by reimbursing it for eligible, non-security expenditure, including salaries of civil servants, teachers and health workers. The Investment Window funded development projects in six main sectors – agriculture, governance, human development, infrastructure, rural development and social development – chosen to align with the government’s development priorities.

4.16 The ARTF provided a means of addressing some of Afghanistan’s many acute development challenges. It provided primary health services across the country. It funded the construction of primary schools, with a focus on areas with low attendance of girls, and supported curriculum and textbook development and teacher recruitment and training. It supported agricultural development through irrigation and drainage projects, and promoted women’s economic empowerment through local self-help groups and access to finance. It invested in basic infrastructure, including electricity connections and roads. The UK was active within the ARTF’s gender working group in promoting the mainstreaming of gender equality and women’s empowerment across the portfolio. These objectives were relevant to the needs of Afghan citizens. As a means of delivering development programming at scale to Afghan communities,

the ARTF was a sound choice.

4.17 The large UK contribution to the ARTF also provided a means of funding the Afghan government’s fiscal deficit, in support of state-building. The ARTF funded around 30% of the non-military budget, enabling the government to pay for civil servants, operating costs and essential items such as interest on its debt. By enabling the government to provide basic services and infrastructure, the UK hoped to build the Afghan government’s legitimacy in the eyes of its citizens. This was consistent with UK government guidance at the beginning of the review period, although later DFID research raised doubts as to whether improvements in services did in fact contribute to building state legitimacy in conflict areas. Given the concerns raised above about the effects of funding at this scale on the development of Afghan institutions, there are questions as to whether the ARTF should have made more use of diverse delivery channels, including non-government partners, to avoid overwhelming state capacity.

The UK scaled up its humanitarian support as conditions deteriorated, but was slow to invest in building resilience to future crises and climate change

4.18 Afghanistan is highly vulnerable to humanitarian crises, including from conflict, natural disasters and extreme weather. Its instability, lack of economic development and dependence on rainfed agriculture make it highly vulnerable to recurrent drought and the accelerating impacts of climate change. Over the review period, there were recurrent humanitarian crises that compounded a deteriorating economic situation. In 2011-12, food insecurity affected 30% of households; by 2016-17, this figure had risen to 45%. By 2019, a third of Afghans were in acute humanitarian need, and five million (12.5% of the population) had been forcibly displaced.

4.19 The UK responded appropriately by scaling up its humanitarian support. Bilateral humanitarian aid doubled from £23.5 million in 2014 (12% of the total) to £53 million in 2020 (23%). The support was mainly directed through UN agencies and the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), taking advantage of their neutrality and greater access to Afghan territory.

4.20 The UK was well informed about humanitarian needs, drawing information from a wide range of sources. The UN system produced an annual Afghanistan humanitarian needs overview, and identified priorities for support in the form of the Afghanistan humanitarian response plan. The Afghanistan humanitarian country team provided a forum for information sharing and coordination, and included the major UN humanitarian agencies, international and national non-governmental organisations (NGOs) and bilateral donors, including the UK. According to interviewees from other agencies, the UK was an active and well-informed participant.

4.21 While the UK’s humanitarian response was well informed and appropriate, it was slow to invest in building resilience to future humanitarian crises. Already, at the start of the review period, UK government stability assessments noted that climate change was a risk multiplier for Afghanistan, exacerbating food and water shortages and compounding instability. In a 2019 country development diagnostic, DFID recognised the need for a long-term approach to building resilience to the impacts of climate change.

4.22 The UK included some small resilience components within its multi-year humanitarian programming. It funded the Afghanistan Resilience Consortium, led by the international NGO AfghanAid, to undertake livelihood interventions in remote communities and build their capacity to bounce back after disasters. Despite some small-scale results in target communities, UK funding for the consortium was discontinued after 2019. Some resilience programming continued in the second phase of the multi-year humanitarian programme, led by the Norwegian Refugee Council. The UK also attempted to build the capacity of the Afghanistan National Disaster Management Authority, but discontinued the effort after poor results.

4.23 Beyond that, the UK remained largely reactive to humanitarian crises. This affected the quality and timeliness of its response. Afghanistan suffered drought every year from 2015 to 2018, culminating in a particularly severe drought in 2018 that affected over two-thirds of the country, with a devastating impact on agriculture. Despite the recurrent nature of the problem, DFID designed an emergency drought programme in 2018 only after the severity of the situation had become apparent, contributing to what was widely considered to be “a slow and inadequate response” by the international humanitarian community. It was only towards the end of the review period that UK programming began to focus on resilience-building and crisis prevention and, according to interviewees, those initiatives had not progressed far into implementation by the time of the UK withdrawal in 2021.

4.24 We note that the tendency to respond to recurrent crises with short-term emergency measures, rather than long-term investments in prevention and resilience-building, is a structural problem across the international humanitarian system, and by no means unique to the UK. However, it is an important lesson that has been pointed out many times before, including in the UK government’s 2011 Humanitarian emergency response review.

Conclusions on relevance

4.25 We award an amber-red score for the relevance of UK aid to Afghanistan. The UK’s most important strategic objective for the aid programme – building a viable Afghan state – contained a number of key flaws that contributed to its ultimate failure. These included the lack of an inclusive political settlement, the top-down nature of the process, the dominance of security objectives and the distorting impact of aid being provided at such a scale. Despite widespread misgivings about the approach and deteriorating conditions within Afghanistan, the UK did not significantly revise its state-building approach, electing to remain aligned with the US. However, we also find that the UK made relevant and important contributions to Afghanistan’s development needs through the ARTF, and responded appropriately to deteriorating humanitarian conditions, although mainly in a reactive rather than a preventative way.

Effectiveness: How effectively did the UK aid portfolio deliver against its strategic objectives in Afghanistan?

4.26 In this section, we examine the effectiveness of UK aid to Afghanistan against its intended outcomes and strategic objectives. We assess how well the UK made use of different delivery channels, and how well it monitored its results.

UK aid made only limited progress in building Afghan government institutions

4.27 UK support for the Afghan government achieved only limited progress towards its core strategic objective of creating a viable Afghan state. The large amounts of financial support, mainly through the ARTF, did enable the state to provide basic services and infrastructure; the development benefits of this for the Afghan people are considered below. However, there is limited evidence of effective state institutions emerging over the review period.