UK aid to Afghanistan: country portfolio review

Purpose, scope and rationale

This country portfolio review will examine the relevance, coherence and effectiveness of the UK’s aid investment in Afghanistan from 2014, when the deteriorating security situation led the former Department for International Development (DFID) to close its office and programmes in Helmand Province, up to the international military withdrawal from Afghanistan in August 2021. An additional information note chapter will cover UK aid spending on humanitarian assistance to Afghanistan from August 2021 to present.

An ICAI country portfolio review is a strategic assessment of the totality of UK aid to a particular country, including multilateral and bilateral aid, as well as aid-related diplomacy. Afghanistan presents a highly unusual context, in that many of the results of the UK’s aid investments are likely to be lost as a result of the takeover by the Taliban and the subsequent humanitarian crisis. Given the extraordinary scale of UK and international aid investment in Afghanistan, ICAI believes that it is important to examine the lessons which emerged, to inform both the current response to the ongoing humanitarian situation in Afghanistan and future work with other countries in crisis.

This review will assess how well the UK’s aid portfolio in Afghanistan delivered on its strategic objectives, as they evolved over the review period. It will look in particular at three of those objectives: i) alleviating humanitarian need, ii) empowering women and girls, and iii) building core state functions. The review will explore the choice of delivery channels, including the UK’s use of and engagement with multi-donor trust funds, such as the Afghanistan Reconstruction Trust Fund. It will explore the UK’s management of the risks associated with the challenging operating context, including the volatile political and security context, restrictions on access, weak national institutions and high levels of fiduciary risk. It will assess the quality of the UK’s partnerships with multilateral institutions, other development partners, national and local government institutions and other national actors. It will also examine how the UK has approached learning from its aid programme in Afghanistan, what it has learned, and how it has adapted its work.

The review will incorporate a factual account of how UK official development assistance has been used in response to the humanitarian crisis that followed the Taliban takeover. The process of the UK’s withdrawal from Afghanistan in 2021 will not be covered in the review, and has been covered in detail by other accountability bodies.

This country portfolio review builds on ICAI’s 2016 review of DFID’s approach to managing exit and transition, as well as two previous ICAI reviews of UK aid to Afghanistan. The review will draw lessons for other aid transitions, and other contexts where the UK is engaged in remote management of humanitarian and development programmes.

Background

The Taliban takeover of Kabul on 15 August 2021 brought to an end a 20-year international military and civilian intervention to stabilise Afghanistan and rebuild its institutions, economy and society. Despite tens of billions of pounds in international aid, the economic and social situation is bleak. The withdrawal of international military and financial support, economic sanctions and the freezing of Afghan state assets has left the country in a state of near collapse. As of March 2022, it is estimated that over 90% of Afghans live in extreme poverty and 24.4 million people need humanitarian support.

Gender inequality, infant and maternal mortality, vulnerability to climate change, energy access, food insecurity, corruption, high levels of insecurity, and drug production all remain significant problems. The COVID-19 pandemic, economic factors and drought have also contributed to a dramatic increase in food insecurity. The World Health Organisation (WHO) warned in 2021 that COVID-19 infection rates had reached record highs, with only 5% of the population fully vaccinated. Following the Taliban takeover in 2021, the World Bank predicted that large amounts of the population would fall into poverty, alongside a worsening humanitarian crisis.

The UK has been a major provider of development and humanitarian assistance to Afghanistan since the beginning of the international military intervention in 2001, and Afghanistan has consistently ranked among the top recipients of UK aid. The UK’s objectives and chosen methods for delivering aid have evolved over the years. From 2001 to the withdrawal of UK combat troops from Afghanistan in 2014, UK aid was principally concentrated in Mazar-e-Sharif, Meymaneh and Helmand Province, where the UK military contingent was stationed. After 2014, it shifted towards country-wide support, principally through multi-donor programmes managed by multilateral institutions. In 2018, the former Department for International Development (DFID) listed its three “headline deliverables” in its Afghanistan country profile as (i) economic development, (ii) humanitarian assistance, and (iii) basic services and building institutions. Over the same period, the former Foreign and Commonwealth Office also managed a portfolio of projects, partly focused on promoting human rights and democracy. Following the 2020 merger into the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office, one of the UK’s aid objectives was to “reduce child mortality rates, and improve access to education and vital infrastructure”. In the February 2021 integrated review, the UK government commits to “continuing to support stability in Afghanistan, as part of a wider coalition.” However, following the withdrawal of international forces and the Taliban’s de facto control, development assistance to Afghanistan by the UK and other donors has been halted, although the UK continues to contribute to humanitarian support through multilateral channels.

Review questions

The review is built around the evaluation criteria of relevance, coherence and effectiveness. It will address the following questions and sub-questions about UK aid to Afghanistan over the period from 2014 to 2021:

Table 1: Our review questions

| Review criteria and questions | Sub-questions |

|---|---|

| 1. Relevance: How well did the UK aid portfolio respond to Afghanistan’s humanitarian and development needs and the UK’s strategic objectives? | • To what extent was UK aid to Afghanistan guided by credible and realistic objectives and strategies? • How well did the UK understand and respond to the development, humanitarian and peacebuilding needs and priorities of the people of Afghanistan, especially vulnerable groups? • How well did the UK adapt its approach to the evolving context in Afghanistan and to lessons learned? |

| 2. Effectiveness: How effectively did the UK aid portfolio deliver against its strategic objectives in Afghanistan? | • How well did the UK aid programme deliver its intended outcomes? • How well did the UK aid programme monitor its results? • How effectively did UK aid support women and girls? • How well did the UK use different delivery channels and manage their risks? |

| 3. Coherence: How internally and externally coherent was UK support for Afghanistan? | • How well did the UK build partnerships with, and influence, other governments, civil society, multilateral agencies and other actors? • How clear was the division of responsibilities between different UK departments and agencies and how well did they work together? • How well has the UK learned from other governments and partners, and how has it disseminated its own learning to others? |

Methodology

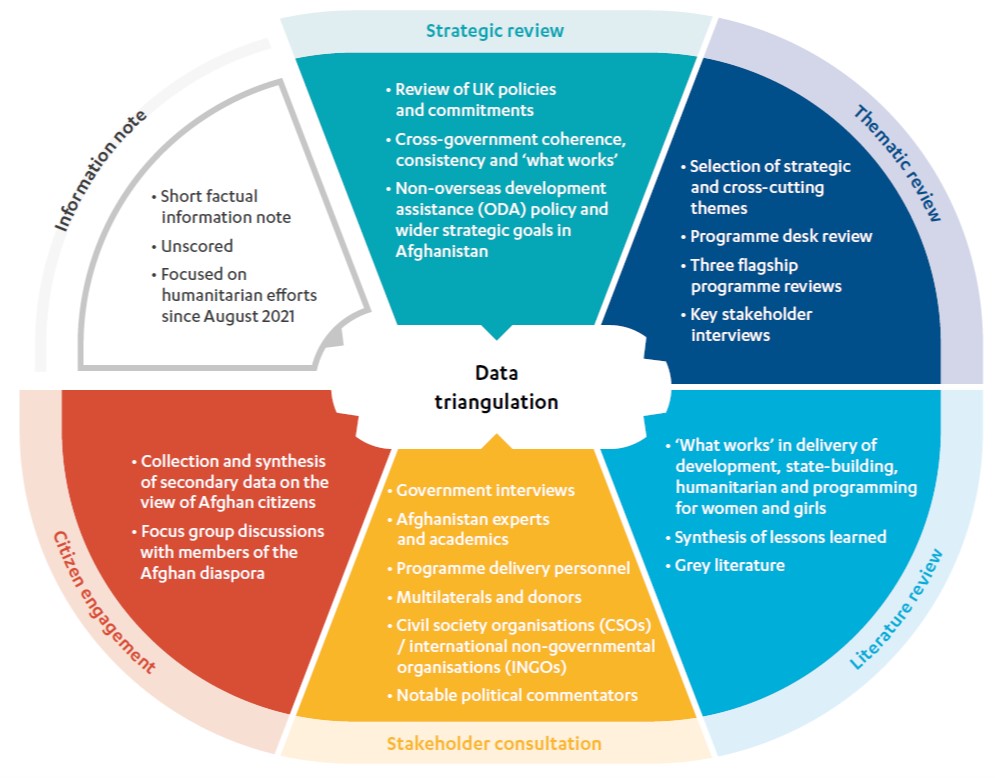

The methodology for this review will involve six main components, each used to inform and triangulate findings in the others. The methodology will make extensive use of Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO) programme data, triangulated through key informant interviews, and other documentary sources, assessed through a literature review. It will also draw on expert and stakeholder opinion, including that of current and former UK government officials (including locally recruited development staff) and officials from other bilateral and multilateral donors. Given access constraints, consultations with Afghan citizens will be conducted primarily in the diaspora. Each component is detailed below.

Figure 1: Our methodology

Component 1 – Strategic review: We will undertake a desk-based mapping of relevant policies, strategies and guidance, a broader document review and key informant interviews with relevant UK government staff, particularly from FCDO, supplemented by interviews with academic experts and other development partners. To address our review questions on relevance, we will trace the evolution of UK strategies and the focus and composition of aid for Afghanistan. This will include assessing the UK’s strategic coherence, both internally (including between aid-related and other objectives for Afghanistan and neighbouring countries) and externally (with other bilateral and multilateral development agencies), and the quality of coordination and partnerships. We will assess how well the UK’s aid portfolio reflected its strategic objectives, and the needs and priorities of Afghan citizens. We will assess if these goals were based on a sound understanding of the context in Afghanistan, including whether they were designed based on clear analysis of the expressed needs of the target communities, reflected and responded to rapidly changing local contexts across the region, and drew on evidence of ‘what works’. We will examine the degree to which the UK approach incorporated components designed to reduce conflict and fragility.

Component 2 – Thematic review: We will explore a selection of strategic and cross-cutting themes across the UK portfolio and within a selection of flagship programmes. We will assess how well the portfolio as a whole contributed to three of the UK’s strategic objectives: i) alleviating humanitarian need, ii) empowering women and girls, and iii) building core state functions, including engagement with central and subnational government, and programming on security, justice and the rule of law (the so-called ‘golden thread’). Against each objective, we will assess the relevance, coherence and effectiveness of the portfolio. We will also explore how well the UK portfolio and programme have incorporated and addressed a number of cross-cutting issues (see Section 5 below). The thematic reviews will assess the UK’s research and evidence collection, its approach and guidance, the quality of programme design, how well implementation challenges were managed and the results. The assessment will be based primarily on programme documentation obtained from the responsible departments, as well as interviews with key stakeholders. The findings of the desk reviews will then be analysed to identify recurrent patterns, including strengths and weaknesses in the programming approach.

Component 3 – Literature review: Our literature review will be both a stand-alone published document and part of the evidence used to inform our assessment. It will provide an overview of the most important published and grey literature (including documents published by the major bilateral and multilateral institutions active in Afghanistan). It will include commentary on current issues and debates, summarise the available evidence of good practice or ‘what works’ in each of our three thematic areas (humanitarian assistance, state-building and the empowerment of women and girls in fragile contexts), and make observations on the strength of the evidence base. It will incorporate research commissioned by the UK government and other development actors.

Component 4 – Stakeholder consultation: We aim to conduct stakeholder consultations and interviews with current and former personnel who worked for the UK in Afghanistan over the review period, programme delivery personnel, Afghanistan experts, academics, independent contractors, multilateral counterparts, other donors, international and Afghan non-governmental organisations, and notable political commentators. These interviews will be held with stakeholders no longer based in Afghanistan to ensure that our interviewees are protected from reprisals from the Taliban. The interviews will help us assess the range and scope of Afghanistan programming and allow for more detailed assessments and in-depth interrogation of relevance, effectiveness and coherence. They will also enable the review team to triangulate and deepen the analysis emerging from the stakeholder consultations and the case studies. The stakeholder consultations will enable us to assess how well UK aid programmes and projects reflect best practice and contextual needs in relation to the evolving and volatile situation in Afghanistan.

Component 5 – Citizen engagement: ICAI is committed to incorporating the voice of citizens in countries affected by UK aid into its reviews. It may not be possible, due to the ethical and practical difficulties involved, to consult with citizens in Afghanistan, but ICAI will conduct this research if the situation allows. ICAI, together with any party who may be commissioned to do such research, will assess the risks to researchers and participants and will proceed only if those risks are manageable. Our citizen engagement will also take place with Afghans in the diaspora, alongside collection and synthesis of secondary data on the views of Afghan citizens.

Component 6 – Information note: The review will incorporate a short, factual information note, which will cover UK aid spending on humanitarian assistance to Afghanistan since the international military withdrawal on 31 August 2021. The information note will not make evaluative judgements, but will provide an account of evolving humanitarian needs and the level and nature of UK commitments to, and support for, humanitarian assistance since the Taliban takeover.

Sampling approach

There are two sampling elements in the methodology. First, we will assess programmes to see how well they supported UK strategic objectives. Second, we will undertake deep dives into a selection of a sample of flagship programmes for detailed review.

We selected three strategic objectives that have consistently been part of the UK’s strategy in Afghanistan over the review period. These are:

- providing humanitarian support, together with efforts to build resilience to crises so as to reduce

- dependence on humanitarian aid over time

- empowering women and girls

- building core state functions, including support for both central and subnational governments,

- and programming on security, justice and the rule of law.

During our review period, the UK delivered 43 bilateral aid programmes in Afghanistan. We will look across all these programmes, weighting them by size and organising them by stated sectoral spend, to analyse their performance in support of the strategic objectives. Note that not all programmes will have worked in support of the objectives set out above. There were significant disparities in budgets, with the largest share of spending going through large, multi-donor programmes implemented by multilateral partners, and two-thirds of all expenditure going through a single programme: the World Bank-administered Afghanistan Reconstruction Trust Fund (ARTF).

Selecting the largest and most important programme under each strategic objective yields a sample of three programmes, representing 80% of the portfolio by value. These are:

- the £150 million contribution to the Afghanistan Multiyear Humanitarian Programme Phase 2

- UK support to the Law and Order Trust Fund, at approximately £248 million

- the UK’s £688 million in contributions to the ARTF.

We will undertake detailed reviews of these three programmes, as well as drawing from the rest of the UK official development assistance portfolio.

We also selected a number of cross-cutting issues that reflect the challenges of providing effective development assistance in the challenging context in Afghanistan, and which may offer useful lessons for future engagement in similar contexts. These are:

- quality of contextual analysis, learning and adaptability

- consultation with Afghan citizens and their participation in the design, delivery and monitoring of aid interventions

- management of delivery and fiduciary risks, including through remote management

- results management

- producing sustainable results and reducing dependence on aid.

When we collect information from the programmes, we will draw out evidence on these issues.

Limitations to the methodology

This review will inevitably be subject to a number of limitations, which will affect the degree to which comprehensive, robust and fully triangulated findings can be obtained. Some key aspects are summarised below.

Security situation in Afghanistan: The collapse of the government of the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan on 15 August 2021 and its replacement by the Taliban-led Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan places severe restrictions on travel to and within Afghanistan. This deteriorating and unpredictable security situation affects the degree to which face-to-face meetings with programme partners and citizens can be undertaken. Most interviews will be conducted remotely, and largely through diaspora partners where appropriate. A particular challenge to ICAI’s preferred approach in this context is the degree to which citizen engagement can be conducted in ways that safeguard vulnerable communities, while ensuring that the voices of marginalised groups are effectively heard and represented.

Data on impact: Our methodology depends primarily on data generated by programme monitoring and evaluation systems to assess effectiveness. Reported results will be triangulated wherever possible through key informant interviews, other published sources and feedback from Afghan citizens in the diaspora. We will also conduct our own assessment of the credibility of the results data that have been generated. However, since our methodology depends on the data produced by programmes, we may be limited in the conclusions we can draw if results data are unavailable or inadequate.

Risk management

We have identified several risks associated with this review and propose a series of mitigating actions, where necessary, as presented in Table 2.

Table 2: Risks and mitigation

| Risks | Mitigation |

|---|---|

| It is difficult to access UK government records that have been restricted due to their sensitive nature | The team members assigned have appropriate accreditation and are able to work cooperatively with FCDO to manage sensitive documents. Our review timeline has been significantly extended to allow extra time to gather material. |

| Visits to Afghanistan carry a prohibitive level of risk due to insecurity | We will conduct some key informant interviews through remote methods, as well as identifying key informants located in the UK and third countries. |

| UK government officials are unable to engage with the review process due to competing priorities | This risk has already materialised during the evidence gathering stage of the review. To mitigate further impacts, ICAI and the review team will remain in close dialogue with FCDO throughout the review process to identify appropriate windows of time for interviewing staff. The review team will also seek out former FCDO staff with knowledge of events earlier in the review period. |

Risks will be reviewed on a regular basis and mitigating actions will be adjusted as the external operating environment changes and if any new risks emerge.

Quality assurance

The review will be carried out under the guidance of ICAI commissioner Hugh Bayley, with support from the ICAI secretariat. Both the approach paper and the final report will be peer-reviewed by Nikolaus Schall, a leading international expert on Afghanistan and governance issues.

Timing and deliverables

The review will take place over a 16-month period because it started in June 2021 and was delayed for five months.

Table 3: Estimated timing and deliverables

| Phase | Timing and deliverables |

|---|---|

| Inception | Review inception: June 2021 Approach paper: June 2022 |

| Data collection | Desk research: February–June 2022 Evidence pack: June 2022 Emerging findings presentation: June 2022 |

| Reporting | Final report: October 2022 |