UK aid to Afghanistan

1. Introduction

1.1 Last year, ICAI published a country portfolio review assessing all UK aid to Afghanistan from 2014, when British troops ended their combat role in Helmand province, to the Taliban takeover in August 2021. In light of the dynamic and deteriorating situation in Afghanistan at the time, Annex 2 of the report provided a brief, non-evaluative account of UK humanitarian aid following the Taliban takeover. Six months on, this information note looks at how the situation has evolved, in terms of both humanitarian needs and the UK’s response, guided by the lines of enquiry we set out in our 2022 report.

1.2 In March 2022 the UK committed to providing £286 million in aid to Afghanistan per year for 2021-22 and 2022-23, making it the UK’s largest bilateral assistance programme. This note summarises whether and how that aid commitment has been spent. ICAI’s role is to assess the effectiveness and value for money of past official development assistance (ODA) spending. Since the UK’s support for Afghanistan is ongoing and humanitarian expenditure is still being disbursed in a rapidly changing context, this information note does not make evaluative judgments. As in our 2022 report, in Section 3 we propose further lines of enquiry that may warrant consideration by ICAI or other bodies.

1.3 As part of our evidence gathering, we reviewed programme documents provided by the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO) and partners it funds, and undertook a series of interviews with staff from FCDO, UN agencies and international non-governmental organisations (NGOs) working in Afghanistan. We are grateful to all who participated in this rapid exercise.

2. The UK response to Afghanistan

The humanitarian crisis continues in Afghanistan

2.1 Nearly two years on from the Taliban’s takeover of Kabul and establishment of a new government in August 2021, the economic and humanitarian situation in Afghanistan remains dire. Despite ongoing support from the international community, the flow of aid is proving insufficient to respond to growing humanitarian needs. Afghanistan is currently the fourth most at-risk country for humanitarian crises and disasters globally, and the country with the highest prevalence of food insecurity. Afghanistan also has one of the steepest population growth rates in Central Asia, at 2.3% per year.

2.2 The UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) reports that 28.3 million people – two-thirds of Afghanistan’s population – will need humanitarian assistance in 2023. This marks a 16% increase from 2022 (24.4 million) and a 54% increase from 2021 (18.4 million).

2.3 Around 25 million Afghans live in poverty, with households spending over 90% of their income on food. Nearly 20 million people are thought to have been acutely food-insecure between November 2022 and March 2023, with more than 6 million people assessed to be at risk of falling into famine. Highlighting the scale of the challenge, the UN’s Food Security and Agriculture Cluster required $553.4 million to maintain its supplies from January to March 2023 alone.

2.4 The escalating conflict of preceding years resulted in 2.6 million refugees fleeing Afghanistan, many of whom remain in neighbouring countries, and another 5.5 million people being internally displaced (IDPs). While the Taliban takeover has mostly brought the fighting to an end, the deteriorating economic situation has meant that few of the displaced have been able to return home, although the rate of return appears to be increasing. The UN Refugee Agency, UNHCR, has recorded over 1 million IDPs who have voluntarily returned since the end of the conflict in 2021, and an estimated 60,000 refugees and 680,000 IDPs are expected to return in 2023.

The prospects for improvement are limited

2.5 Following the Taliban takeover, most public service delivery mechanisms in Afghanistan suffered almost complete collapse. Much foreign aid was suspended, and the assets of the country’s central bank are not accessible to the country’s new rulers. An economic crisis was triggered by the cessation of much foreign assistance. This crisis has been exacerbated by sustained inflation of key commodity prices (in

line with the global rise in these prices) and a series of natural disasters in 2022. Afghanistan has now entered its third consecutive year of drought-like conditions, although there are indications that the impact on agricultural production this year may be less than originally thought. However, sustained high food prices, economic instability, reduced household income, and the gradual return of refugees and IDPs continue to increase humanitarian needs.

2.6 Improved security and greater humanitarian access to all provinces, including locations that had previously remained inaccessible, had initially been two of the most notable improvements resulting from the Taliban takeover. However, these benefits were soon outweighed by a number of restrictions imposed by the de facto authorities on Afghan women, as well as persistent interference in humanitarian

organisations’ activities. At the same time, a lack of funding for national NGOs has meant that many have ceased operating.

The rights of women and girls continue to be eroded

2.7 Many of the gains achieved by Afghan women and girls over recent years, which we described in ICAI’s 2022 report, have been eroded since August 2021. There are now severe restrictions to women’s freedom of movement, right to education and right to work.

2.8 In March 2022, the Taliban reversed an earlier pledge to reopen girls’ secondary schools. In December 2022 a ban on women attending universities was announced. On 24 December 2022, the Taliban then issued an edict banning women from working with national and international NGOs. This resulted in a widespread pause or shutdown of many aid operations until mid-February 2023, while NGOs, UN agencies and donors sought to coordinate their response to the edict. The restrictions, which did not initially apply to the UN and other international organisations, were, however, followed in April 2023 by another ban restricting female national staff members from working for UN agencies.

2.9 The impact of these restrictions varies between and within provinces. From January 2023 onwards, national-level exemptions were informally agreed for health and community-based education workers. A range of local-level exemptions were also negotiated by NGOs. However, 94% of NGOs initially fully or partially ceased their operations, with over 70% of their activities directly impacted. The effects were also felt by service users. The protection of citizens sector was one of the most impacted areas of humanitarian work. A January 2023 poll found that women could no longer access services from one in five of the 87 Afghan NGOs surveyed. The services offered by NGOs in Afghanistan have been scaled back. The proportion of organisations reporting operations as either fully or partially suspended decreased from 38% and 68% respectively in mid-January to 12% and 58% in early February.

2.10 The World Economic Forum found that banning women from working in the government and formal sectors will cause Afghanistan’s gross domestic product (GDP) to contract by a minimum of $600 million in the immediate term. Restrictions on women’s private sector employment could lead to a further $1.5 billion loss of output by 2024. This is likely to exacerbate the country’s significant brain drain and growing shortage of human resources, particularly in the health and education sectors.

2.11 Muslim-majority countries and the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation (OIC) have condemned the latest edicts and have been engaging with the Taliban on women’s rights, with the OIC stating on 29 December 2022 that the decision to prevent women and girls from accessing education ran contrary to Islamic law. The UN’s Deputy Secretary-General, Amina Mohammed, also met with Taliban officials in Kabul in January 2023 to try and negotiate a reversal of bans and restrictions on women. Following the meeting, she reported that there had been some progress in engaging with the Taliban on the rights of women and girls, but that the international community, including other Islamic states, was not doing enough to engage on the issue.

2.12 We heard from interviewees that local and national civil society organisations have been more impacted by the ban than international organisations. While UN and international NGO female staff were able to negotiate with local Taliban officials to continue their activities, the Taliban refused to negotiate with Afghan women, raising the risk of getting their projects cancelled. Local women-led organisations have raised concern that UN agencies were not adequately using their negotiating position with the Taliban to stand up for national organisations.

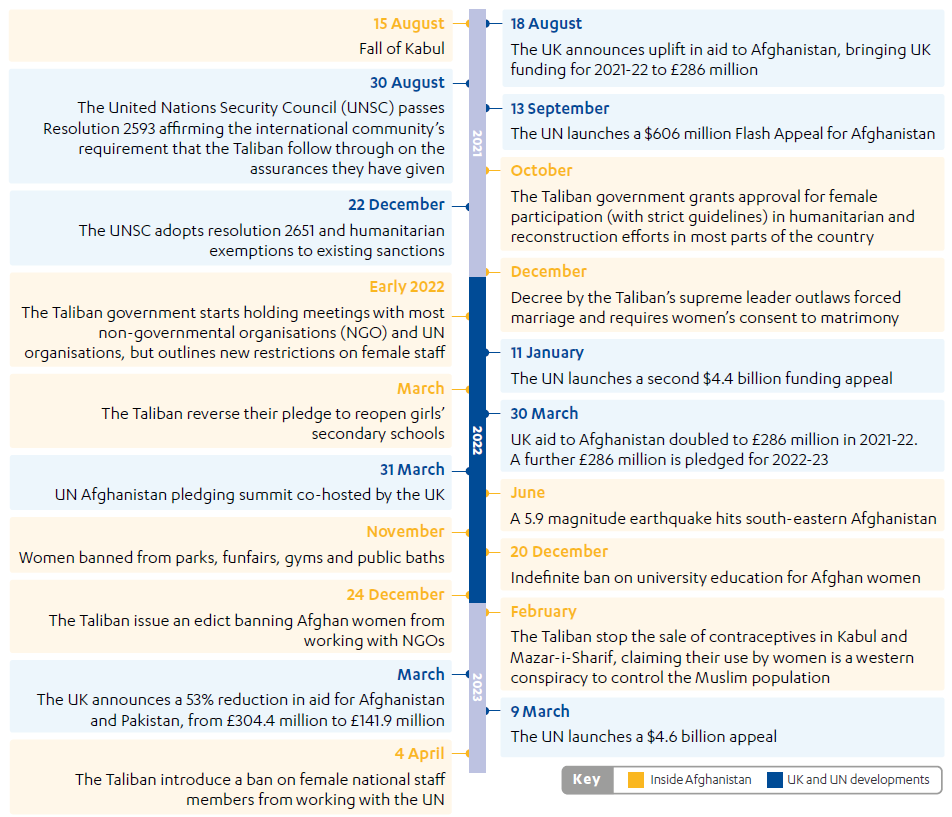

Figure 1: Timeline of key dates since August 2021

Funding of the response is running consistently behind needs

2.13 Since August 2021, the UN has launched annual appeals to support the humanitarian response in Afghanistan. In the first ‘Flash Appeal’, launched on 13 September 2021, the UN sought $606 million for multi-sectoral assistance to 11 million people for the remainder of 2021, including $193 million for newly emerging needs. By January 2022, the crisis had escalated dramatically and the UN appealed for a further $5 billion. This included $623 million to support refugees and host communities in five neighbouring countries and $4.4 billion for humanitarian operations inside Afghanistan (the largest ever single-country appeal), of which donors only funded 73%.

2.14 In March 2023, the mandate of the United Nations Assistance Mission in Afghanistan was extended for another year. On 9 March 2023, the UN launched a $4.6 billion appeal to assist 23.7 million people in 2023, despite predicting that even more people (28.3 million) will be in need. The appeal had been developed for release in January 2023, but the 24 December edict against women led to an operational pause by most organisations. The 2023 Humanitarian Response Plan (HRP) is the largest in UN history. At the time of writing, the appeal was just 7.2% funded ($334.3 million). A revision of the HRP is currently underway which is likely to result in a decrease in the number of people targeted for assistance. This reduction is in large part due to funding constraints. The UN has warned that donors risk disengaging if the edicts restricting women remain in force.

2.15 The United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) said that a sustained inflow of foreign aid, of around $3.7 billion in 2022 (including $3.2 billion from the UN), has helped “avert the total collapse of Afghanistan” and put the country on a slow path to recovery. The UN has noted that aid enabled a rise in exports, an 8% increase in domestic fiscal revenue, stabilisation of the exchange rate, and a reduction in inflation. UNDP calculated that GDP in Afghanistan could increase by 1.3% this year if foreign aid remained at 2022 levels. However, prospects for long-term economic recovery remain weak, especially if foreign aid is withheld as a result of restrictive Taliban policies. UNDP calculated, for example, that a 30% reduction in aid from $3.7 billion to $2.6 billion would further contract Afghanistan’s GDP by 0.4%.

2.16 Donor fatigue was mentioned on several occasions to ICAI by international agencies. There are concerns that some donors will not continue to fund Afghanistan. US Special Representative for Afghanistan, Thomas West, has expressed concerns that contributions from many international donors will be lower in the year ahead as emergencies in Ukraine, Syria and Turkey “have created extraordinary needs” that, compounded with fiscal pressures, will force countries to be selective in the degree of humanitarian assistance they can provide.

2.17 Funding gaps are already apparent, despite new and renewed support from some donors. Traditional donors have either announced or indicated that they would likely scale back support. Some have paused their decision, adding to a climate of unpredictability. We heard that this is affecting partners and implementers’ ability to plan, amid concerns that, as one NGO respondent told us, “humanitarians are being asked to do more and more with less and less”.

Box 1: A lack of funds has resulted in humanitarian food rations being cut

The World Food Programme (WFP) reports that 20 million people will have faced acute food insecurity between November 2022 and March 2023. However, critical funding shortfalls are reducing the WFP’s ability to support those that are food-insecure in Afghanistan. To stretch its resources, in March 2023 the WFP reduced the ration provided to households defined as in a food emergency to 50% of people’s basic nutritional needs, down from the 75% ration it was previously providing.

In April 2023, the WFP reported it had reduced its planned caseload from 13 million to 9 million people, meaning that 4 million Afghans it identifies as in need of emergency assistance will not receive any due to severe funding constraints. If additional funds are not urgently received, the WFP says it will be forced to cut assistance to a further 4 million people in May, providing food aid only to 5 million, and may have to cease distribution of any assistance in June. The WFP reports that any interruption of aid risks creating famine-like conditions in areas vulnerable to food insecurity. The WFP currently reports that it will need $800 million to provide the 50% ration to those in need in Afghanistan through to the end of 2023.

There is no unified international strategy towards Afghanistan

2.18 While the international community continues to demonstrate unity in its response to specific crises in Afghanistan (such as the 2022 earthquake and the December 2022 and April 2023 edicts narrowing women’s rights), the volatility of the situation and increasingly repressive Taliban policies have prevented donors and the UN from defining key drivers of needs and articulating a clear pathway for sustained support. In a context such as Afghanistan, moving beyond providing humanitarian assistance towards building more durable domestic capabilities in the country’s economy and institutions would be a typical objective for donors and international agencies in order to avoid a protracted crisis.

2.19 In interviews, many respondents lamented the lack of a coherent, long-term strategy towards Afghanistan from donors and the wider international community. They noted that there remain diverging views on how to provide aid. There are different views among donors on whether and how aid for basic services should be made conditional on the behaviour of the authorities (for instance in relation to their treatment of women and girls). We also heard concerns that there were dangers in applying such blanket conditionalities. Maintaining flexibility for different agencies to respond to the immediate humanitarian challenges based on developments at the local level was important, we were told. Many respondents also requested that donors, in particular the UK, provide technical assistance, particularly to improve basic public services. We heard mixed views on the efficiency of the UN sector ‘clusters’ (where service delivery organisations come together to coordinate responses to particular challenges), and in particular the health cluster. Some respondents described this architecture as over-complicated and no longer fit for purpose. They told us that there was no clear view of what aid should be provided in the future, or the structure of future coordinating mechanisms for donors.

2.20 FCDO documentation that we reviewed notes that responding to continuously increasing appeals is unsustainable in view of global resource challenges, competing priorities, and increased pressures on donor budgets. FCDO recognises that longer-term solutions are needed. While the department acknowledges that appeals, and the resulting scaling-up of the humanitarian response, have been largely successful in mitigating the worst-case scenarios, the approach remains broadly reactive, or limited in time and scope (multi-year to one-year agreements). As yet there is no clear plan to move beyond humanitarian aid.

While still a large donor, the UK is reducing its support to Afghanistan

2.21 The UK has been an active and significant donor to Afghanistan. In August 2021, the UK government announced a doubling of UK aid to Afghanistan, to a total of £286 million for the 2021-22 financial year, with funds channelled through UN partners and international NGOs. On 30 March 2022, the UK government announced it would provide a further £286 million commitment for the 2022-23 financial year. The key priorities were to support food security and protection interventions, as well as increase preparedness for winter, and FCDO hoped to disburse 90% of its commitment by the end of December 2022. The UK also provided £5 million for immediate support after the earthquake in eastern Afghanistan in June 2022. The overall allocation was, however, subsequently reduced to £246 million, resulting in activities being halted or rephased in programmes for polio inoculations and landmine and improvised explosive device clearance.

2.22 Having spent 95% of its revised ODA allocation by late November 2022, the UK was left with a limited budget for Afghanistan for the remainder of the 2022-23 financial year. As a result, funds planned to be provided through the World Bank-administered Afghanistan Reconstruction Trust Fund (ARTF) were rephased to the 2023-24 financial year, which enabled the remaining financial allocation to be spent on humanitarian programming. In March 2023, Andrew Mitchell, the minister of state for development and Africa, announced FCDO’s 2023-24 ODA budget for Afghanistan and Pakistan of £141.9 million, 53% lower than the 2022-23 figure of £304.4 million.

2.23 As things stand, we understand that the UK’s support for Afghanistan in financial year 2023-24 will be £100 million in total, £75 million of which will be spent on humanitarian support. The intention is that 90% of this sum will be disbursed by December 2023.

2.24 The UK government’s Afghanistan ODA allocation has reduced over the past two years, in the context of successive reductions to UK ODA and the unprecedented scale of ODA utilisation for housing refugees in the UK. Respondents (including from UK-based NGOs) offered the view that a pound of ODA spent in Afghanistan can have a much greater impact than a pound of ODA spent in the UK. We were told that repeated failures to fulfil pledges risk damaging the UK’s standing with its partners. Several respondents questioned how this was consistent with the UK government’s commitment to reinvigorate its position as a global leader in development, as set out in the Integrated Review Refresh published on 13 March 2023.

2.25 Table 1 sets out the allocation by implementing partner for the financial years 2021-22, 2022-23. The allocations for partners in financial year 2023-24 are yet to be finalised.

Table 1: UK aid to Afghanistan by implementing partners since the fall of Kabul

| Partner | Financial year allocations for 2021-22 | Financial year allocations for 2022-23 |

| United Nations Development Programme | £91 million | £50 million (Afghanistan Humanitarian Fund |

| World Food Programme | £93 million | £95 million |

| United Nation’s Children Fund | £27 million | £28 million |

| International Committee of the Red Cross | £23 million | £16 million |

| International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies | £7 million | £4 million |

| Disasters Emergency Committee | £10 million | |

| UN Refugee Agency | £8 million | |

| International Organisation for Migration | £7 million | £12.2 million |

| Norwegian Refugee Council | £4.1 million | £7.9 million |

| UN Population Fund | £2.2 million | £8.1 million |

| International Rescue Committee UK | £2 million | £9.2 million |

| UNMAS (Global Mine Action Programme 2) | £10 million | |

| Supporting Afghanistan's Basic Services NGOs | £12.2 million | |

| Other | £1.7 million | £3.4 million |

| Total | £286 million | £246 million |

Sources: FCDO management data. Figures as of August 2022 and April 2023.

2.26 In March 2022, the UK co-hosted a high-level pledging conference alongside Germany and Qatar, raising $2.4 billion towards the UN’s Afghanistan appeal of $4.4 billion. While holding the presidency of the G7, the UK led discussions with the World Bank. These culminated in the restructuring of the ARTF and, with the involvement of the Asian Development Bank, the release of $1.8 billion for Afghanistan.

Unpredictability hampers a consistent approach to providing UK aid

2.27 We note that FCDO staff were only made aware of the 2023-24 ODA budget for Afghanistan at the end of the 2022-23 financial year. While FCDO staff had warned partners of budget reductions, the late decision on actual funding allocations added to an existing climate of unpredictability for those organisations operating in Afghanistan. The UK has historically been able to provide clarity earlier, and has often funded partners over multiple years, usually through three-year plans. However, due to reductions to the aid budget and pressures such as the COVID-19 pandemic and, more recently, the allocation of a large proportion of ODA to in-country refugee costs, the UK has only been able to announce funding allocations on an annual basis. Committing funding for just one year has both operational and reputational impacts for the UK aid programme.

Box 2: The UK government’s strategic priorities for Afghanistan

Overall UK priorities: Mitigating the threat of terrorism in Afghanistan and the Central Asia region; stemming refugee flows; and curbing poppy cultivation which fuels the drug trade in the UK.

UK aid priorities: Health and education; agriculture; livelihoods and the economy; women and girls’ ability to access assistance, services and education, and play a role in the delivery of aid; and support for reproductive health, gender-based violence and child protection.

Source: UK government documentation (not published).

2.28 FCDO told us it intends to develop a multi-year strategy for ODA in Afghanistan and stated that flexibility has been built into all programmes to ensure that the UK government can retain agility in response to changing circumstances. While there are some multi-year programmes, financial commitments are currently only confirmed on an annual basis. FCDO has developed two new humanitarian programmes to replace the Afghanistan Multi-year Humanitarian Programme. The Supporting Humanitarian Assistance and Protection in Afghanistan programme and the Afghanistan Food Security and Livelihoods programme will also provide funding over three years.

Operational challenges remain significant

2.29 Aid agencies in Afghanistan continue to face an increasingly complex and restrictive operating environment. Documentation reviewed for this information note highlights persistent Taliban interference in organisations’ activities and processes, including selection of people intended to benefit and participation in field missions. Agencies also face the challenge of having to navigate factional divisions within the Taliban. Organisations delivering aid in Afghanistan told us that, according to in-country staff, delivering aid without the support of Taliban officials is near-impossible. We heard calls for UN agencies and implementing partners to reach agreement with the de facto authorities at provincial and local levels in order to effectively deliver humanitarian assistance.

2.30 Officials from FCDO, UN agencies and most international NGOs expressed concern to ICAI about a gradually deteriorating security situation in Afghanistan, notably from Islamic State in Khorasan Province (ISKP) and other terrorist organisations in the region (Al-Qaeda and Tehrik-i-Taliban Pakistan (TTP) in particular). The operation of these groups risks further destabilising the country and the wider region. Stakeholders interviewed by ICAI also expressed concerns that changes to the school curriculum could exacerbate the spread of extremism. The UN has warned of a deteriorating security situation in the country, and of a growing number of sanctioned individuals among the Taliban. The UK’s Permanent Representative to the United Nations, Dame Barbara Woodward, said in December 2022 that “while the Taliban is failing to meet its counterterrorism commitments, it cannot expect to see sanctions relief or acquire legitimacy in the eyes of the international community or the Afghan people”.

2.31 NGOs and other international organisations that we spoke to believed that the stringent security plans they currently have in place would need to remain for the foreseeable future. These, along with the restrictions on women’s movement and activities (such as the creation of gender-segregated offices and the need for a mahram – or male chaperone – for female travel) have also increased operational costs. One implementer warned about the risk of a general erosion of humanitarian principles as NGOs bargain to keep operating. Data collection and sharing is put at risk due to fears of retribution against people intended to benefit and local workers if sources are disclosed. At the delivery level, despite the monitoring mechanisms put in place by donors and implementers, it remains impossible to fully eliminate the risk of misappropriation of aid by local de facto authorities, with taxes applied by the government also reducing the amount of assistance ultimately provided. As one implementer pointed out in the documentation reviewed, NGOs are among the most lucrative targets for extractive behaviour.

2.32 Many respondents recognised the reputational risks associated with operating in Afghanistan and understood the UK’s requests for regular reporting on activities. Several noted that the level of scrutiny demanded by the UK (in terms of accounting for spending and outputs) was greater than that required by other donors. FCDO says it will be focusing closely on monitoring and reporting in 2023-24 to maximise the impact of UK ODA. This monitoring also seeks to ensure that UK funding does not go through Taliban systems. Many of FCDO’s implementing partners have third-party monitoring (TPM) contracts to ensure programme objectives are met and aid is not diverted. FCDO has also established a four-year £6 million Assurance and Learning Programme that will provide TPM for those organisations that do not have their own resources. This programme has just completed its inception stage.

The UK has been active in seeking to overcome key challenges

2.33 FCDO has encouraged information sharing and contingency planning with different partners. Following the Taliban’s December edict on women, the UK played a critical role in helping achieve a unified approach by the international community to continue the meaningful participation of women in programming activities. In particular, the UK successfully advocated against the suspension of a large proportion of international support for Afghanistan in response to the edict, a move called for by a number of donors and NGOs. The UK also contributed to a ‘guiding principles’ document following the 24 December edict (although we heard mixed views on how well such guidance had been communicated).

2.34 The UK co-chairs (with Qatar) the UN Group of Friends of Women of Afghanistan and has repeatedly affirmed its commitment to upholding the rights of women and girls in Afghanistan. FCDO does not have any direct programming with women’s organisations in the country. However, from January to March 2022, a UNICEF-led initiative involving partners implementing safe space models for women and girls was funded by FCDO. In February 2023, the UK launched the fifth National Action Plan on Women, Peace and Security, a five-year plan aimed at reducing the global impact on women and girls in conflict, as well as other global threats like climate change and cyber crime. The plan focuses on 12 countries where the threats are most acute, including Afghanistan.

2.35 However, given the funding gaps resulting from the reductions to the UK’s aid budget, it is not clear how FCDO will meet its commitments. FCDO informed Save the Children in March 2023 that it would fund just over £1 million of a promised £7 million for a year-long programme that started in December 2022. This prompted Gwen Hines, CEO of Save the Children UK, to say that “The decision to cut millions in funding to Afghan children sends a stark message to the world that the UK is turning its back on the most vulnerable children and families in one of the world’s most challenging contexts. The UK’s rhetoric that it supports women and girls in Afghanistan now rings hollow.”

2.36 The documentation reviewed for this information note highlighted that some organisations have been able to employ additional staff and set up more field work thanks to FCDO funding. Two UN respondents told us that UK contributions to the appeal had prevented Afghanistan from experiencing famine conditions. Most organisations have also commended the UK for its flexibility in funding in the face of an unpredictable operational context, and one described the UK as one of the few donors trying to take a longer-term view and a structured approach towards Afghanistan.

UK diplomatic engagement remains but is based outside Afghanistan

2.37 Despite losing over half of its staff complement after the fall of Kabul in August 2021, FCDO told us that a team of over 80 people is now in place to support UK efforts in Afghanistan. International humanitarian agencies have commended the UK for demonstrating continuing engagement with the humanitarian coordination structure in Afghanistan, including by co-hosting donor meetings. However, the UK staff working on Afghanistan remain based either in the UK, or in Qatar or Pakistan.

2.38 The lack of international diplomatic representation in Afghanistan (bar the UN and the European Commission’s Directorate-General for European Civil Protection and Humanitarian Aid Operations) was highlighted in interviews as increasingly problematic. Many respondents considered donors, including the UK, as insufficiently engaged with Afghan decision makers in the country, and noted that this reduced their ability to understand the context in which they operate. Several respondents reinforced the importance of face-to-face engagement with the Taliban, and one pointed out that top-level Taliban officials would not hold virtual meetings.

2.39 We heard concerns that the lack of an international political process of engagement was creating hazards for the humanitarian effort. Aid efforts and agencies were at risk of being politicised, rather than being seen as providing neutral, independent humanitarian assistance. Respondents told us that in the absence of a diplomatic presence in Afghanistan, international NGOs and humanitarian workers increasingly risk being seen as proxy representatives for their home governments.

2.40 Most organisations we spoke to insisted on the need for donors to disassociate operational engagement with the Taliban (to achieve humanitarian and developmental objectives) from a formal recognition of the group as the legitimate government (characterising them as the ‘de facto authorities’ instead). It appears likely that the Taliban, despite internal divisions and external threats against them, will remain in power in Afghanistan for the foreseeable future. We heard a common view from agencies on the ground that diplomatic engagement with the Taliban entails reputational risks. Equally, stakeholders argued that disengagement from Afghanistan would result in significant risks to the UK’s strategic interests and harm the Afghan people. A consistent commentary from respondents was that the Taliban see UK aid as addressing humanitarian needs. The UK remains, in the words of one respondent, a “big player”. Many of the organisations interviewed saw top-level donor engagement with the Taliban as a prerequisite for a credible aid response in Afghanistan. Several international NGOs and UN agencies have pressed donors, particularly the UK, to play a stronger role in engaging in dialogue with the de facto authorities in a way that will give humanitarian organisations operational space and access.

3. Future lines of enquiry

3.1 We conclude with some points that may merit further scrutiny in the coming period, by the UK Parliament’s International Development Committee, ICAI itself or other bodies, as the humanitarian crisis in Afghanistan continues to unfold.

- How should the UK and other donors maximise the impact of humanitarian assistance while minimising the benefits which accrue to the de facto authorities?

- How can the UK move beyond a crisis response towards other modes of development assistance that build durable local capacities and reduce dependence on humanitarian aid?

- What strategy should the UK and other donors adopt to preserve, as far as possible, the rights and opportunities which women and girls won before 2021?

- How should the UK respond to the risk that other donors may disengage from Afghanistan as a result of growing insecurity and the Taliban edicts?

- Should the UK consider making the case within the international community for wider engagement with the Taliban, without implying that this would lead to recognition or normalisation of relations?

- What are the potential advantages and disadvantages of the UK re-establishing a physical presence within Afghanistan, when security conditions allow, to exercise more effective oversight of UK aid?