UK aid to agriculture in a time of climate change

Score summary

The UK’s work on aid to agriculture in a time of climate change has been mainly relevant, with many examples of effective interventions, although it has not been sufficiently coherent. Budget reductions and strategic drift have reduced the relevance, coherence and effectiveness of UK efforts.

The agriculture sector provides livelihoods for the majority of the world’s poorest. While climate change is impacting food production and livelihoods, agriculture is also a major contributor to global warming. UK aid to agriculture is provided through delivery programmes by the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO) (formerly the Department for International Development (DFID) and the Foreign and Commonwealth Office) and investments by British International Investment (BII) (formerly CDC Group plc), while agricultural research is funded by FCDO and the Department for Science, Innovation and Technology (DSIT) (formerly the Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy (BEIS)).

DFID/FCDO’s delivery programmes have been well targeted at inclusive growth and poverty reduction, with growing attention to climate change. They have frequently been ambitious and innovative, making serious efforts to integrate climate and nutrition in the commercial agriculture portfolio. BII’s statutory requirement to realise a return on investment led to less focus on direct poverty reduction and fewer incentives for integrating climate, gender and nutrition, although attention to these has improved. DFID/FCDO’s agricultural research has been highly relevant to development challenges, much more so than that funded through the BEIS/DSIT Global Challenges Research Fund (GCRF).

The 2015 Conceptual framework on agriculture has provided DFID/FCDO with a clear approach for an agricultural development portfolio focused primarily on supporting commercial opportunities for smallholder farmers, while also continuing to support the resilience of subsistence farmers and providing opportunities for those that are ready to exit agriculture. Reorganisations, leadership churn and successive crises have eroded this strategic clarity. Some technical capacity has been lost in recent years and there is not yet a coherent agenda on climate and agriculture across government. International partners still value the UK’s thought leadership and the generation and use of evidence, but the UK is drawing upon a dwindling reputation.

We found strong results from innovative approaches, with positive impacts on people’s livelihoods and agency and some contributions to gender equity. Short intervention periods and poorly designed exits may undermine the sustainability of some results, and while some programmes and investments contributed to climate resilience, other results are unlikely to be sustained, or may even exacerbate climate vulnerability. UK-funded agricultural research for development, particularly that managed by DFID/FCDO, has contributed new knowledge and achieved some development impact, while funding rules for the GCRF hampered its ability to promote development impact.

| Individual question scores | |

|---|---|

| Relevance: Does the UK have a credible approach to supporting agriculture? |  |

| Coherence: Does the UK have a coherent approach to ODA-funded agriculture? |  |

| Effectiveness: Is the UK’s support for agriculture achieving its intended outcomes on inclusive economic growth and poverty reduction, food and nutrition security and climate resilience? |  |

Acronyms and glossary

| Acronym | Definition |

|---|---|

| AR4D | Agricultural research for development |

| BBSRC | Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council |

| BEIS | Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy (dissolved in February 2023 and separated out into the Department for Energy Security and Net Zero, the Department for Science, Innovation and Technology, and the Department for Business and Trade) |

| BII | British International Investment (formerly CDC Group) |

| BRACC | Building Resilience and Adapting to Climate Change in Malawi |

| CABI | Centre for Agriculture and Bioscience International |

| CAPR | Commercial agriculture portfolio review |

| CASA | Commercial Agriculture for Smallholders and Agribusiness programme |

| CFA | Conceptual Framework on Agriculture |

| CGIAR | Formerly the Consultative Group on International Agricultural Research |

| CIRAD | Agricultural Research Centre for International Development |

| CLIC | #ClimateShot Investor Coalition |

| Defra | Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs |

| DFID | Department for International Development (merged with the Foreign and Commonwealth Office in September 2020) |

| DSIT | Department for Science, Innovation and Technology (established after the dissolution of BEIS in February 2023) |

| ESG | Environmental, social and governance standards |

| FCO | Foreign and Commonwealth Office (merged with the Department for International Development in September 2020) |

| FCDO | Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (established after the merger of the Department for International Development and the Foreign and Commonwealth Office in September 2020) |

| G7 | The international Group of Seven: Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, the UK and the US. |

| GAFSP | Global Agriculture and Food Security Programme |

| GCRF | Global Challenges Research Fund (in February 2022 it was announced that the GCRF and two other ODA-financed research and development funds would be discontinued. In December 2022 it was announced that a blended ODA and non-ODA International Science Partnership Fund would form part of the replacement for the ODA research and development funds, although full details have yet to be confirmed) |

| IATI | International Aid Transparency Initiative |

| ICF | International Climate Finance |

| IDRC | International Development Research Centre |

| IMSAR | Improving Market Systems for Agriculture in Rwanda |

| IPCC | Intergovernmental Panel for Climate Change |

| MADE | Market Development in the Niger Delta |

| MEL | Monitoring, evaluation and learning |

| MTIP | Malawi Trade and Investment Programme |

| NERC | Natural Environment Research Council |

| ODA | Official development assistance |

| OFSP | Orange-fleshed sweet potato |

| POSA | Programme of Support to Agriculture in Rwanda |

| PROSPER | Promoting Sustainable Partnerships for Empowered Resilience |

| RCUK | Research Councils UK |

| SDGs | Sustainable Development Goals |

| SIARC | Support to the International Agriculture Research Centres |

| SILTPR | Sustainable Inclusive Livelihoods through Tea Production in Rwanda |

| SIVAP | Small-Scale Irrigation and Value Addition Project |

| SPARC | Supporting Pastoralism and Agriculture in Recurrent and Protracted Crises |

| UKRI | UK Research and Innovation |

| Key term | Definition |

|---|---|

| Agriculture | All activities relating to crop and livestock production. |

| Agricultural extension services | Services, often provided by government agencies, private or third sector organisations, that provide farmers with technical advice and training and often also support access to agricultural inputs and other agricultural services. |

| Agricultural inputs | Resources used in agricultural production such as fertiliser, seeds, chemicals and equipment. |

| Agribusiness | Any business involved in farming or farming-related commercial activities including production, processing and distribution. |

| Agrifood | All activities relating to the production and dissemination of food and non-food agricultural products. |

| Centrally managed programme | ODA-funded programme that is managed from FCDO headquarters in the UK. |

| Challenge fund | A competitive financing mechanism for allocating funding to innovation projects that offer a social return, often with some expectation of commercial viability and a matching contribution from the grantee. |

| Climate adaptation | Changes to processes, practices and structures in order to adjust to the current or expected effects of climate change. |

| Climate-smart agriculture | Approaches that simultaneously improve agricultural productivity and incomes, strengthen resilience to climate shocks and/or adapt to changing conditions, and reduce and/or remove greenhouse gas emissions where possible. |

| Commercial agriculture | Producing crops and livestock for sale. |

| Conference of the Parties (COP) | The main decision-making body of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. |

| Enabling factors | Investments such as infrastructure, private sector development and financial initiatives that are not directly agriculture-related but enable agricultural development. |

| Food security | When all people at all times have economic access to sufficient quantities of safe and nutritious food to meet their dietary needs. |

| Greenhouse gas (GHG) | Greenhouse gasses, such as carbon dioxide (CO2) and methane (CH4) contribute to global warming by absorbing infrared radiation emitted from the earth’s surface and reradiating it back to the earth’s surface. |

| Nutrition-sensitive agriculture | Includes interventions anywhere in the food system, from production to processing and distribution, to improve nutritional outcomes. |

| Off-farm activities | Processes and jobs relating to agriculture that occur beyond the farm, usually at the middle and end of the value chain, such as processing, distribution and sale. |

| Paris Agreement | An international agreement on climate change to limit global temperature which was adopted by 196 countries in 2015. |

| Private sector development | A range of approaches that are based on the underlying assumption that economic opportunities for the poor are best generated by promoting growth in the private sector. |

| Smallholders | Farmers on ‘small-scale’ farms that are under two hectares in size. |

| Smallholder commercialisation | A process whereby farmers transition from largely subsistence activities – growing food for their own consumption – to growing food for sale to markets, thereby contributing momentum to broader economic growth. |

| Value chain | The activities required to bring an agricultural product from production to the consumer. Value is added through activities such as processing, packaging and distribution. |

Executive summary

In 2021, during its presidency of COP26, the UK led a call for action to transform global food and agriculture systems. It urged focus on sustainable agriculture that would provide nutritious, affordable food for all while restoring ecosystems, building climate resilience and reducing climate emissions. At COP27 leaders reaffirmed the call for greater collaboration and investment in transforming the world’s food systems in the face of climate change. These priorities reflect growing awareness that progress towards the Sustainable Development Goal of Zero Hunger is faltering, that climate change is accelerating and that the two are linked.

The UK spent an estimated £2.6 billion in bilateral aid to agriculture between 2016 and 2021, the last year for which robust data are available. This included funding for programmes delivering direct development interventions, agricultural research programmes and aid-funded investments in agricultural businesses. Delivery and research programmes of the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO) (formerly the Department for International Development (DFID) and the Foreign and Commonwealth Office (FCO)) accounted for the majority of this spending. The former Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy (BEIS), now the Department for Science, Innovation and Technology (DSIT), also funded a significant amount of agricultural research. Investments in agribusinesses were made by the UK’s development finance institution, British International Investment (BII) (formerly CDC Group).

The purpose of this review is to assess how well the UK has used such significant funding to support agricultural development in a time of climate change. It examines whether the UK’s approach to funding is credible, is relevant to best practice, and supports climate adaptation. It considers whether the different approaches taken by the UK have been internally coherent and how well they have fitted with those of other international funders and partner governments. Finally, the review assesses whether these activities have been effective, at both the programme and the portfolio level.

Our methodology includes a literature review, country case studies of UK programming in Malawi, Nigeria and Rwanda, programme desk reviews, and engagement with UK officials, experts, donors and citizens in Malawi and Rwanda.

Relevance: Does the UK have a credible approach to supporting agriculture?

The UK has used aid to support agriculture through a variety of delivery models and several government departments and bodies. A common focus of these diverse programmes has been to support commercial agriculture, particularly helping smallholder farmers to access markets and to improve their agricultural production in order to engage in commercial activities. This approach is based on evidence that smallholder commercial agriculture generates inclusive growth in rural economies.

DFID/FCDO’s delivery programmes have appropriately targeted their interventions at key challenges in agriculture and its enabling environment. In our case study countries, we saw sophisticated, innovative and ambitious programmes that supported agricultural development while reducing poverty. Many of these programmes helped smallholders to engage with markets by improving their access to agricultural inputs, reducing barriers to selling their produce and stimulating demand.

BII’s statutory requirement to realise a return on investment meant that it tended to reduce risk by investing in the growth of large, well-established firms. There is good evidence for BII’s contributions to business growth, although the evidence for job creation is variable and evidence for other development benefits is limited. Until relatively recently, BII has lacked strong incentives to integrate additional priorities such as nutrition, gender or climate and environmental considerations into its investment decisions. The UK’s investment portfolio has therefore exhibited weak relevance in these important themes of our review. This has improved since BII adopted a new development impact framework and published strategies on food and agriculture and on climate change in 2020.

Official development assistance (ODA)-funded agricultural research from 2016 to 2021 was delivered by both FCDO (formerly DFID) and the former BEIS (now DSIT). FCDO has considerable expertise in funding applied agricultural research for development impact. FCDO and DFID funded long-standing international research centres, such as CGIAR (formerly the Consultative Group on International Agricultural Research), with histories of delivering agricultural research of high quality and development relevance. By contrast, most of BEIS’ spending was channelled through new funds, in particular the Global Challenges Research Fund (GCRF), established in 2016. Initially, the GCRF was implemented mainly through the research councils, with UK Research and Innovation (UKRI) taking a lead role after it replaced Research Councils UK (RCUK) in 2018. Focused primarily on supplying funding to UK universities and research institutes, the research councils and RCUK had limited expertise and prior experience of ODA-funded research to draw on when the GCRF was launched in 2016. The GCRF’s funding mechanisms were built for research reflecting the interests of UK academics rather than the interests of developing countries or researchers in the Global South. Changes to the GCRF’s operating arrangements, following an ICAI review in 2017, improved the development relevance of later awards, but by the time these changes came into effect, most of the GCRF’s funding had already been committed.

The climate relevance of the UK’s work on agriculture has increased dramatically over the period of our review, albeit starting from a very low base. The agriculture sector is highly vulnerable to climate change, and is the third-largest source of climate emissions in the global economy. It is therefore surprising that early strategic documents paid little attention to climate change. Consequently, few agriculture programmes in the early phase of our review period contained interventions directly addressing climate change. Over time, more DFID/FCDO delivery programmes had a focus on climate and drew funds from earmarked International Climate Finance. While this is a positive development, there is a risk that programmes integrate climate change concerns only superficially or retrofit climate relevance into programmes, with variable success. While DFID/FCDO’s portfolio of delivery programmes have improved their relevance on both climate and gender, we found little attention in the programme design to how gender shapes climate vulnerability.

Overall, we have awarded a green-amber rating for relevance, despite sometimes insufficient attention to climate, nature and nutrition in delivery programmes and investments, and constraints arising from UKRI’s focus on UK-led agricultural research.

Coherence: Does the UK have a coherent approach to ODA-funded agriculture?

The 2015 Conceptual framework on agriculture developed by the former DFID provided a degree of coherence between delivery programmes supporting smallholder commercialisation, those stimulating growth and jobs in the rural economy, and social protection and resilience-building programmes supporting smallholders not yet ready for commercialisation. In our country case studies, we saw layered and innovative country portfolios with the potential for transformative change. In Malawi, for example, DFID/FCDO programmes supporting private sector policy reforms and improving export markets were complemented by programmes building resilience in agricultural communities, while investments by BII and AgDevCo, a specialised investor in Africa’s agriculture sector funded by DFID/FCDO, BII and other donors, supported medium and large agribusinesses.

Senior-level coordination between BII, FCDO and AgDevCo improved over time, as evidenced by BII’s 2021 investment in AgDevCo. However, we found instances of missed opportunities for coordination, even when this had been built into business cases. There were few incentives in-country for information sharing and joint action. Lack of effective operational coordination between BII and FCDO hampered, for instance, the UK’s ability to engage effectively along agricultural supply chains.

There was a high degree of volatility in the UK’s agricultural research portfolio between 2016 and 2021, with a rapid increase in spending in the first years. In 2016, DFID dominated aid to agricultural research. By 2017, spending on agricultural research had doubled, with almost half funded by the former BEIS, mainly through the GCRF. After 2018, funding fell each year. While the GCRF was an ambitious development in the UK’s agricultural research offer, its rapid deployment and implementation was destabilising. DFID and GCRF research were not well coordinated in the Fund’s early years. Following recommendations from a 2017 ICAI review of the GCRF, coordination improved, but by that point most of the GCRF’s funding had been committed.

At the global portfolio level, internal coherence has been undermined by successive disruptions to staff availability and capacity, from Brexit, the COVID-19 pandemic, the merger of DFID and FCO, and ODA reductions. A sense of ‘strategic drift’ in the agriculture portfolio was compounded by successive changes in budget allocations and in ministerial priorities, and a reduced role for experts in decision making. We spoke to many officials who recognised the importance of advancing an ambitious agenda around climate-resilient food systems. We found little confidence among them that the UK government would currently be able to deliver.

Internal coherence at the country portfolio and programme level was dramatically affected by ODA reductions starting in 2020. In Malawi, ODA reductions undermined the delivery of what had been a highly effective and coherent programme, Building Resilience and Adapting to Climate Change (BRACC). Several components were either downsized or removed altogether, undermining the programme’s ability to deliver on its intended objectives. We found similar examples of country programmes and portfolios being curtailed and coherence being lost in Rwanda and Nigeria. In Rwanda we saw a previously exemplary country portfolio, with an impressive level of complementary and mutually reinforcing interventions, hollowed out by budget reductions, a loss of staff and programme closures.

Despite ODA reductions, the UK has retained some capacity to influence partner governments, donors and multilateral institutions. Although it has lost a significant number of expert agricultural advisers, the UK continues to be viewed as a technically competent development ally. It has used this reputation to its advantage, for example, taking influential positions on the steering committees of multilateral initiatives such as the Global Agriculture and Food Security Programme. Capable and dynamic in-country staff have been able to use the UK’s reputation to leverage influence and improve cohesion among donors working in the agricultural ecosystem. However, with funding reduced, the UK has been drawing on this reputation, and there is a significant risk that its influence will degrade rapidly in the near future.

Increasing fragmentation and weak synergies between programmes, the impact of ODA reductions on complementary interventions, and declining influence with partner governments merit an amber-red rating for coherence.

Effectiveness: Is the UK’s support for agriculture achieving its intended outcomes on inclusive economic growth and poverty reduction, food and nutrition security and climate resilience?

The UK’s ODA-funded agricultural delivery programmes and investments were successful at creating employment and raising incomes. Farmers we spoke to in Malawi and Rwanda confirmed that they used increased incomes to buy local goods and services, contributing to rural growth. UK investments in agribusinesses also supported business growth and job creation, although we found limited evidence for wider pro-poor development impacts.

Achieving transformational change in agriculture requires long-term, patient engagement. UK delivery programmes were often too short to achieve such change. Where programmes were extended, such as the Propcom Mai-karfi programme in Nigeria, results were more likely to achieve scale and sustainability.

The integration of climate and nutrition was variable across delivery and investment programmes. Over time, programmes increasingly included climate-relevant interventions, although often with a low level of ambition. In Rwanda, for example, the Improving Market Systems for Agriculture in Rwanda (IMSAR) programme’s work on agricultural value chains encouraged farmers to make specific adaptations, such as adopting climate-smart crop varieties and technologies. But IMSAR interventions did not address climate risk in agricultural supply chains or help build the systemic resilience of smallholders. By contrast, programmes such as BRACC in Malawi and Sustainable Inclusive Livelihoods through Tea Production in Rwanda used innovative, community-based approaches to climate action which offered better and more sustainable results for smallholders.

While we found DFID/FCDO-funded agricultural research to be effective, with high developmental impact, the effectiveness of research funded through the GCRF was hampered by UKRI’s funding rules. This undermined the GCRF’s ability to help researchers in the Global South build capacity and achieve impact. We found that climate and environmental considerations were variably integrated into the UK’s agricultural research portfolio. While DFID/FCDO research programmes had a very significant and direct focus on climate action, it was not always a significant theme in GCRF awards. This improved over time, and GCRF awards included some very innovative and sophisticated climate-related research.

Approaches towards gender improved. Most DFID/FCDO programmes in our sample were aware of gender best practice, targeted women in interventions and provided gender-disaggregated monitoring data. BII also improved its approach to gender in new investments following the development of its 2020 impact framework, although gender remains under-addressed in its legacy investments. The approach to integrating gender into the GCRF portfolio of research was initially poor, but improved after 2019, following a recommendation from ICAI. But by this time, 75% of awards in the agriculture portfolio had already been made.

The UK has been largely effective in monitoring, evaluation and learning (MEL), although this was not consistent across the portfolio. UKRI’s approach to MEL in the GCRF largely focused on the overall portfolio, while a hands-off approach to post-award management may have undermined UKRI’s ability to understand how its procedures limited the GCRF’s development impact. BII’s initial approach to MEL in its investments was of mixed quality and coverage, in line with its strategic focus at the time, with few of its earlier investments monitoring benefits to poor people beyond job creation. DFID/FCDO’s approach to MEL was more effective and consistent, although a major opportunity for learning may have been missed as DFID/FCDO has never attempted to synthesise learning from across its portfolio.

Towards the end of our review period, we saw significant reductions in the effectiveness of UK programmes in agriculture due to ODA cutbacks. The cutbacks were particularly severe for FCDO’s delivery programmes. Scaling back and cancelling programmes negatively affected the portfolio’s ability to deliver against intentions. ODA reductions also made it more difficult to focus on cross-cutting priorities such as nutrition, gender, climate change and MEL. Since MEL is an important component of the UK’s influencing and thought leadership efforts, reduced MEL spending threatens to undermine the UK’s comparative advantage as a donor.

We rate the effectiveness of the UK government’s agriculture portfolio as green-amber, reflecting the effective contributions to poverty reduction of UK programmes and investments over 2016-21. However, we note the sometimes superficial approaches to climate change and nature, the GCRF’s insufficient attention to the developmental effectiveness of agricultural research, and a declining focus on MEL.

Recommendations

Recommendation 1: The government should ensure that all agriculture programmes and investments have an integral focus on climate change and nature.

Recommendation 2: All commercial agriculture programmes and investments should be monitored for nutritional outcomes.

Recommendation 3: The government should act to secure the UK’s influence and thought leadership on agriculture.

Recommendation 4: FCDO, BII and AgDevCo should look for operational synergies and complementarities between programmes and investments to maximise effectiveness, building on their comparative advantages.

Recommendation 5: DSIT and UKRI should integrate learning about development effectiveness, including from previous ICAI reviews, into future ODA-funded agricultural research.

1. Introduction

1.1 Agriculture both contributes to climate change1 and is adversely affected by its effects. Addressing the inaugural UN Food Systems Summit in September 2021, UN Secretary-General António Guterres told his audience that achieving the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) would require a transition to sustainable, nutritious, equitable and secure food systems. At the COP26 summit in Glasgow in November 2021, participants recognised the need to reduce climate emissions from agricultural systems and strengthen climate resilience and sustainability. At COP27 in November 2022, food and agriculture were included in the text of climate negotiations for the first time. This was broadly welcomed, but most policymakers and scientists acknowledge that transforming global food systems is an incredibly complex task, and the current level of funding and coordination is far below what is required to achieve such a transformation.

1.2 The impacts of climate change on agriculture, food security and nutrition are already felt across the world. The world’s least developed countries are the worst affected, as they rely more on agriculture for livelihoods and have low climate resilience. The UK’s 2022 International development strategy established climate change, nature and global health as one of the UK’s four overarching priorities for

its work on sustainable development. The 2023 refresh of the Integrated review mapped out seven initiatives for delivering the UK’s development strategy, including leading a campaign to improve global food security and nutrition. The review established tackling climate change, environmental damage and biodiversity loss as the UK’s top thematic priority.

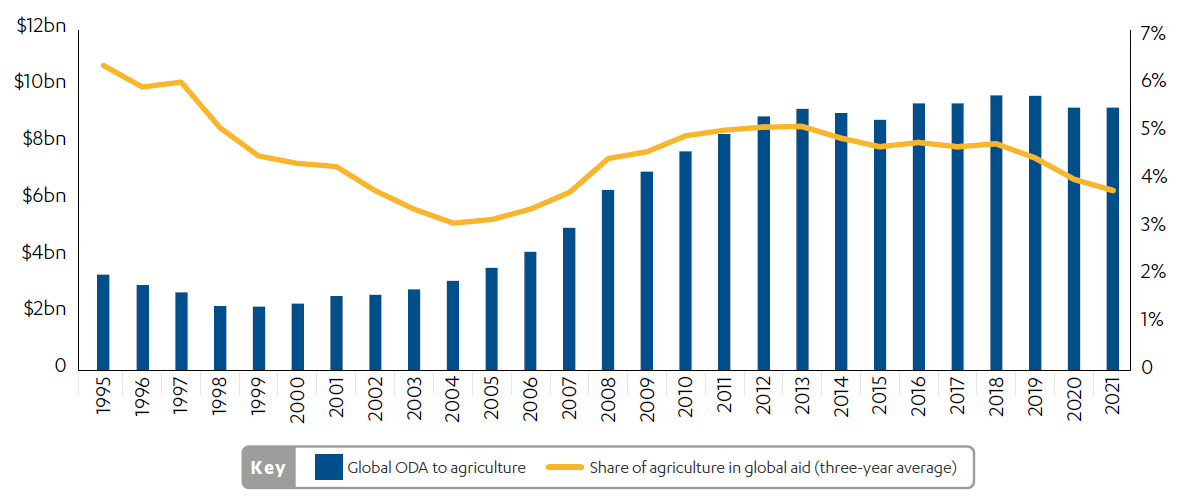

1.3 Despite agriculture’s importance for many developing countries and its very close links to climate change (in both cause and effect), agriculture is not a top priority for international donors. The share of global official development assistance (ODA) spent on agriculture has fallen from 25% of global bilateral aid spending during the 1980s to around 4% today. The UK has been part of this downward trend. Of the G7 countries, it is currently the fifth-largest bilateral donor to agriculture, in both relative and absolute terms.

1.4 This review assesses UK aid for agriculture, with an overarching focus on how the UK’s agriculture portfolio integrates climate change and climate action. The portfolio has three main types of interventions: delivery programmes, research and investments. First, delivery programmes are aid-funded programmes with direct development interventions as their primary objective. These can be delivered through multilateral or bilateral channels and as part of multi-country or country-specific programmes. Second, agricultural research is a significant portion of UK aid spending on agriculture. And third, aid-funded investments in agriculture are made by the UK’s development finance institution, British International Investment (BII). Across these three intervention types, the review considers how the UK has used its position to influence other donors and multilateral institutions and catalyse international action on agriculture.

1.5 This review assesses UK aid to agriculture since 2016, when the UK’s last major strategy for agricultural development was launched. The review assesses aid from the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO) (formerly the Department for International Development (DFID) and the Foreign and Commonwealth Office (FCO)), the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs and the former Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy (BEIS), as well as investment from BII (formerly CDC Group).

1.6 The review considers criteria of relevance, coherence and effectiveness. It addresses the questions and sub-questions set out in Table 1. Box 1 below summarises how the issues explored in this review are related to the SDGs.

Box 1: How this report relates to the Sustainable Development Goals

The Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) are a universal call to action to end poverty, protect the planet, and ensure that all people enjoy peace and prosperity. Agriculture cuts across a wide range of sectors and issues, including the SDGs relating to poverty, health, decent work and economic growth. The following SDGs are of particular relevance to this review:

![]() Goal 2 is to end hunger, achieve food security and improved nutrition and promote sustainable agriculture. It relates in a very clear and direct way to agricultural development. Goal 2 targets include increasing resilient agricultural practices, maintaining seed and crop diversity and boosting investment in agriculture and agricultural research.

Goal 2 is to end hunger, achieve food security and improved nutrition and promote sustainable agriculture. It relates in a very clear and direct way to agricultural development. Goal 2 targets include increasing resilient agricultural practices, maintaining seed and crop diversity and boosting investment in agriculture and agricultural research.

![]() Goal 13 relates to taking urgent action to combat climate change and its impacts, including strengthening resilience and adaptive capacity to climate-related hazards. Agricultural interventions that are adaptive to climate change fall under this goal.

Goal 13 relates to taking urgent action to combat climate change and its impacts, including strengthening resilience and adaptive capacity to climate-related hazards. Agricultural interventions that are adaptive to climate change fall under this goal.

![]() Goal 15 covers the protection, restoration and sustainable management of land to reverse degradation and halt biodiversity loss. Conservation agriculture, agroforestry, and sustainable agriculture interventions are relevant to this goal.

Goal 15 covers the protection, restoration and sustainable management of land to reverse degradation and halt biodiversity loss. Conservation agriculture, agroforestry, and sustainable agriculture interventions are relevant to this goal.

Table 1: Our review questions

| Review criteria and question | Sub-questions |

|---|---|

| 1. Relevance: Does the UK have a credible approach to supporting agriculture? | • How well does the UK aid approach to agriculture take into account the expected impacts of climate change? • How well does the UK aid approach to agriculture support inclusive economic growth and poverty reduction? • In a time of climate change, is the UK making relevant ODA investments in agricultural research? |

| 2. Coherence: Does the UK have a coherent approach to ODA-funded agriculture? | • How coherent and coordinated are programmes across UK ODA-spending departments and arm’s-length bodies? • How well has the UK worked with and influenced partner countries and multilateral institutions on agriculture? |

| 3. Effectiveness: Is the UK’s support for agriculture achieving its intended outcomes on inclusive economic growth and poverty reduction, food and nutrition security and climate resilience? | • How well have farmers, consumers and people affected by agriculture programmes been engaged in the design of UK aid programmes? • How well are UK aid programmes helping to build sustainable agricultural practices which meet needs and respond to environmental concerns? • To what extent is learning and evidence from research programmes being taken up and utilised in-country? |

2. Methodology

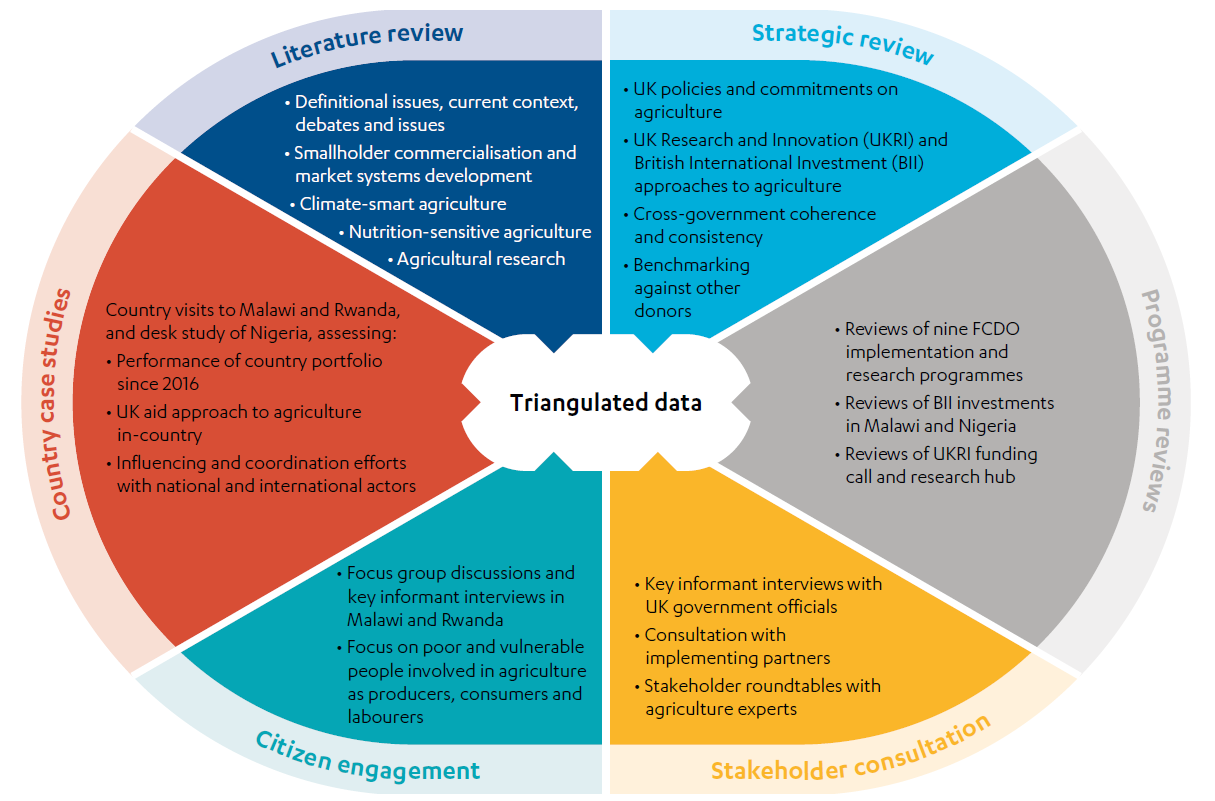

2.1 The methodology for our review involved six components (see Figure 1) to gather evidence against our review questions and ensure sufficient triangulation of findings:

- Literature review: provides an overview of the peer-reviewed and grey literature on the review’s main topics to identify ‘what works’ in agricultural development. The literature review is published separately on the ICAI website.

- Strategic review: a desk-based review of key UK strategies, policies, commitments and guidance notes concerning agriculture, climate and development. This review included two benchmarking exercises comparing the UK’s approach to agricultural delivery programmes and research with other major international donors.

- Programme reviews: desk reviews of agricultural delivery programmes, research programmes, and investment. This included seven delivery and research programmes managed by the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO), a selection of direct equity and intermediated investments in Malawi and Nigeria made by British International Investment (BII), and a sample of six grant awards made under the Global Challenges Research Fund (GCRF) and managed by UK Research and Innovation (UKRI).

- Stakeholder consultation: interviews with a wide range of stakeholders including current and former UK government officials, implementers of UK ODA-funded programmes, firms receiving UK ODA investment, representatives of other donors, and agricultural experts. We also conducted two stakeholder workshops with independent experts, one on climate change and agriculture, the other on agricultural research.

- Country case studies: we reviewed three UK aid country portfolios through visits to Malawi and Rwanda, and a desk-based study of Nigeria. In each country we assessed the UK’s aid programme, including investments, delivery and research programmes, in terms of relevance, coherence and effectiveness.

- Citizen engagement: we consulted with people directly or indirectly affected by UK agriculture aid in Malawi and Rwanda. The consultations were conducted by national research partners, supported by citizen engagement experts to ensure that rigorous safeguarding and research protocols were followed.

Figure 1: Our methodology

Our methodology and approach were independently peer-reviewed. The methodology and sampling process is detailed in our approach paper. Some of the main limitations to our methodology are listed in Box 2.

Box 2: Limitations of the methodology

Scope: ‘agriculture’ potentially includes a very broad range of issues, interventions and approaches. While the sector benefits from aid supporting enabling factors, such as infrastructure, private sector development, and financial initiatives, our review focuses on aid badged as agriculture. Forestry and fisheries are not included in this review. ICAI is planning a future publication covering UK aid spending on marine protection. Forestry has also been covered by ICAI in a previous review.

Sample: our review covers a diverse portfolio, split between several ODA-spending departments with divergent approaches. Our relatively small sample of a large and varied portfolio is informative, rather than representative. As our programme and investment sample focuses on aid badged as agriculture, it likely under-represents total UK support to the sector (see data quality, below). Our country case studies include some agriculture-related private sector, trade and finance programmes to understand their coherence with the agriculture-badged country portfolio. Our approach to agricultural research funded by the former Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy (BEIS) focused on the GCRF, and we sampled grants made after 2018 and managed by UKRI. We excluded other avenues of BEIS spending, and GCRF funds managed by Innovate UK, as information was not available during our evidence gathering stage.

Data availability: less evidence was available from the earlier years of our review period. Key stakeholders able to provide insights on earlier projects had moved on, and for some countries we were unable to access strategic documents such as country development diagnostics and country business plans covering the years before the merger of the Department for International Development (DFID) and the

Foreign and Commonwealth Office in 2020. We overcame this to an extent by interviewing national FCDO staff with longer experience of working in-country, and through analysis of publicly available literature from the pre-merger period of our review.

Data quality: spending badged as agricultural development and agricultural research was obtained from International Aid Transparency Initiative (IATI) databases. This under-represents total UK spending on agriculture, as some agriculture projects were badged under other sectors. For example, some agricultural development projects were wholly or partially badged as food assistance or small and medium enterprise development. Similarly, much agricultural research was reported as environmental research or general, multi-sector research. We use IATI data as indicative of DFID/FCDO delivery programmes, BII investment, and BEIS research spending.

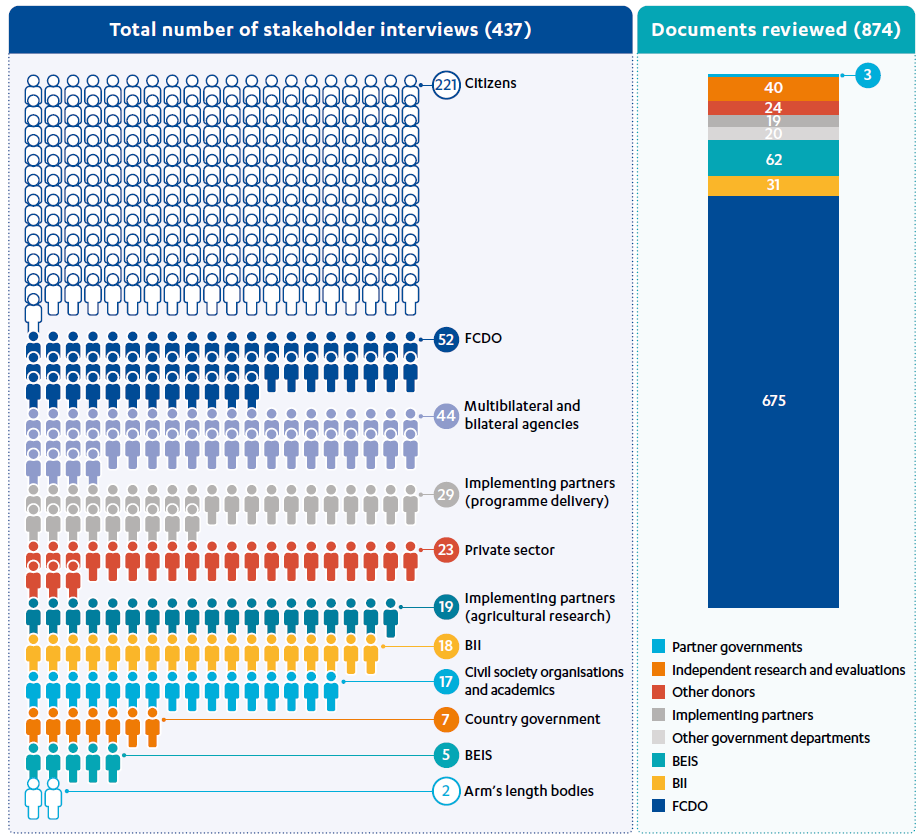

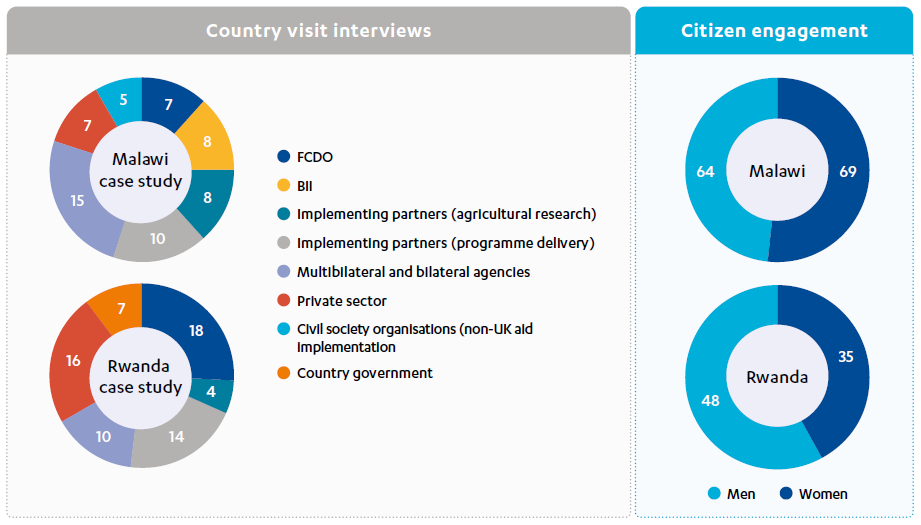

2.3 We conducted 87 interviews in the UK, and over 120 interviews with 200 individuals in Malawi and Rwanda. We also heard from over 200 individuals in Malawi and Rwanda through our citizen engagement exercise. We reviewed close to 900 documents across our methodological components. Figure 2 details the reach of our documentary and stakeholder consultation.

Figure 2: Breakdown of stakeholder interviews, country visit interviews, citizen engagement and documents reviewed

3. Background

Global context

3.1 Agricultural development supports Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 2, which aims to eliminate all forms of hunger everywhere by 2030. Investments in agricultural development have long focused on productivity gains. In the post-war period, this investment helped to increase global food supply much faster than the growth in global population. Hundreds of millions of people nevertheless face hunger and malnutrition two decades into the 21st century.

3.2 Most poor people live in rural areas and rely on agriculture for their livelihoods. Investing in agricultural development can therefore be an effective way of targeting rural poverty reduction by increasing income and employment. Raising agricultural yields and flows of produce to markets can also ease the poverty of food consumers by increasing supplies and bringing down food prices. The SDG targets have concentrated minds on how to reduce poverty rapidly in low-income countries. Agriculture has been recognised as an engine of broader economic development that can contribute to growth in the industrial and service sectors.

3.3 It is estimated that women provide at least half of the agricultural workforce, yet find it more difficult than men to sell crops for profit and to access land, agricultural extension services, finance, and resources used in agricultural production (known as agricultural inputs) such as fertiliser and labour. Such barriers mean women are less resilient to climate-related shocks. Despite increasing recognition of a gendered dimension to climate vulnerability in agriculture, it is feared that funding for climate action does not sufficiently target women farmers or the specific issues they face.

3.4 Long-term climate change and the increased frequency and intensity of extreme climate events are already affecting agricultural production and food security. Climate change will reduce food production even under the Intergovernmental Panel for Climate Change’s (IPCC) most optimistic scenario of an average 1.5°C warming. Pressures from climate change on all areas of agriculture, including food production, livestock health and water availability, will increase even further under the IPCC’s less optimistic scenarios. Global finance for assisting agriculture to adapt to climate change is far below estimated requirements to address these pressures.

Figure 3: Global bilateral official development assistance (ODA) to agriculture

Source: Creditor Reporting System (CRS) database, OECD.Stat.

Note: Only bilateral ODA is reported on the OECD CRS database, therefore the figure above only reflects trends in global bilateral ODA.

3.5 In our three case study countries – Malawi, Nigeria and Rwanda – most people’s livelihoods depend on rain-fed agriculture, which is highly vulnerable to climate impacts. All three countries are classified as highly vulnerable to climate change, with Malawi in the top ten countries exposed to climate risk. Climate shocks affecting agriculture between 2016 and 2021 included extreme storms in southern Malawi in 2019 and 2020, drought in eastern Rwanda in 2016 and recurrent droughts in northern Nigeria. Meanwhile, ODA to agriculture in the three countries has been in decline since 2017.

UK aid’s approach to agriculture

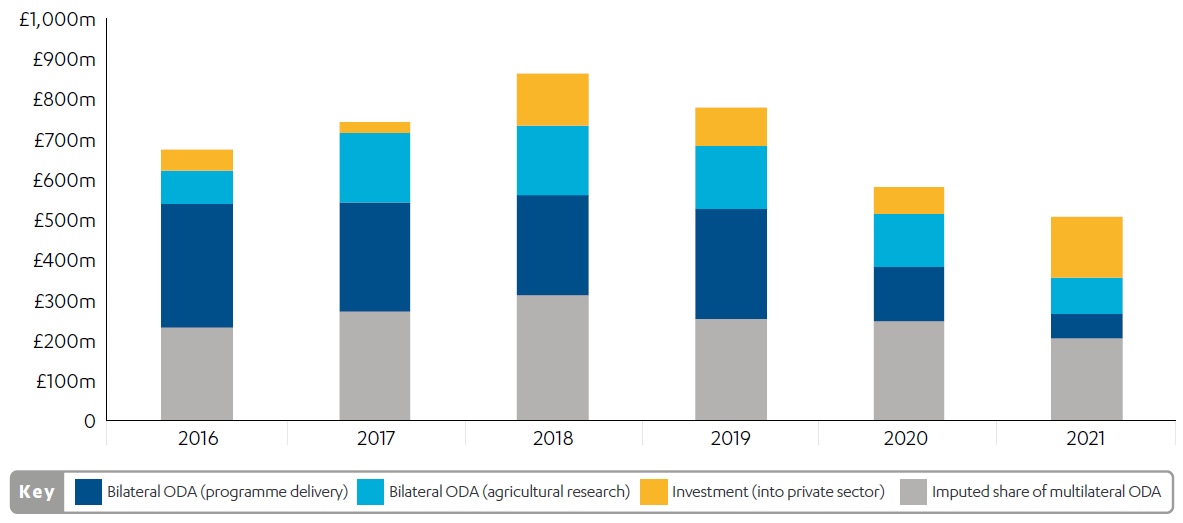

3.6 While the review relies on evidence about the UK’s approach to agriculture since 2016, we have spending figures only up to the end of 2021. Between 2016 and 2021, total UK aid to agriculture was £4.15 billion (see Figure 4). This consisted of £2.63 billion in bilateral ODA and £1.52 billion in imputed multilateral ODA.

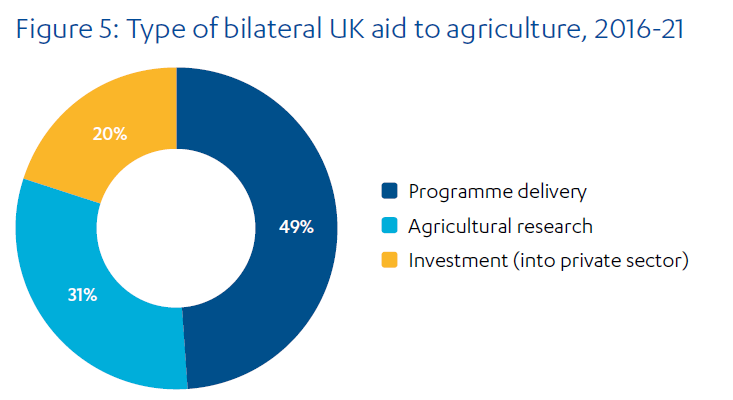

3.7 In this review we focus our analysis on the UK’s bilateral ODA funding, the portion of aid that is managed directly by the UK. We have not attempted to include the UK’s imputed multilateral ODA spent on agriculture. We differentiate between spending on agricultural research, investment in agribusinesses and grant-funded agricultural delivery programmes (see Figure 5).

Figure 4: Total UK aid to agriculture, by modality and type, 2016-21

Source: Creditor Reporting System Database, OECD.Stat; d-Portal, International Aid Transparency Initiative, link; Statistics on international development: final UK aid spend 2021 and 2017.

Figure 5: Type of bilateral UK aid to agriculture, 2016-21

Source: Creditor Reporting System Database, OECD.Stat, link; d-Portal, International Aid Transparency Initiative.

3.8 The Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO) sets the strategic direction for much of the UK’s aid approach to agricultural development. For most of our review period this was managed by the Department for International Development (DFID), until that department was merged with the Foreign and Commonwealth Office in 2020.

3.9 The most important document setting out the UK’s approach to agriculture during our review period was DFID’s 2015 Conceptual framework on agriculture (see Box 3). DFID’s 2017 Economic development strategy also includes a section on agriculture that was influenced by the direction set out in the Conceptual framework. The 2021 Integrated review sets out the UK’s position on food security and using international trade to encourage sustainable agriculture, while the 2023 refresh of the Integrated review commits to the UK leading on food security, nutrition and strengthening global resilience against risks posed by climate change and environmental damage. The 2022 International development strategy acknowledges agriculture as a sector where UK expertise can boost sustainable economic growth, but does not comment on it in depth. The UK’s 2030 strategic framework for international climate and nature action, published in March 2023, commits to UK leadership on decarbonisation, with agriculture as a priority sector, and building resilience, including by increasing global adaptation finance. A recent speech made by the UK’s international development minister outlining a new vision for UK development included priority areas for addressing global hunger by boosting funding for climate resilience, as well as maintaining and championing a focus on agricultural research and investment.

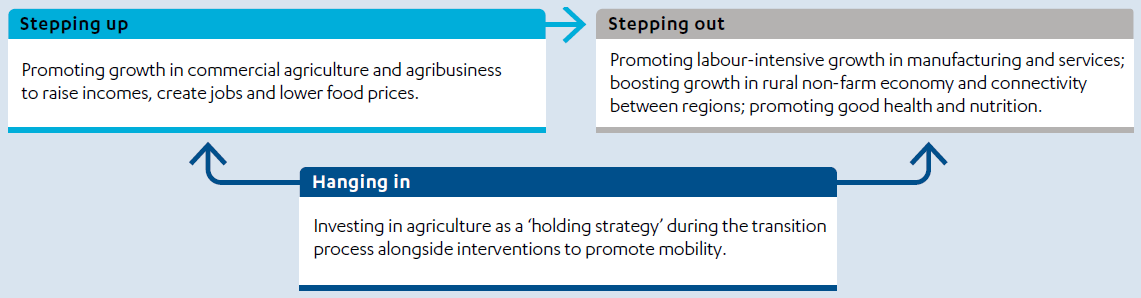

Box 3: DFID’s Conceptual framework on agriculture

Published in November 2015, the former DFID’s Conceptual framework on agriculture (CFA) has been the principal document guiding the UK’s approach to agricultural programmes since 2016. The CFA set the direction for future programming by synthesising contemporary evidence on opportunities, challenges and risks facing the agricultural sector in developing countries.

The CFA focused on the food and agriculture sector’s contribution to three interconnected goals:

- Economic growth and poverty reduction: how agriculture contributes to jobs and higher incomes for the rural poor.

- Food security and improved nutrition: how agriculture leads to reliable access to sufficient, nutritious and safe food.

- Sustainable food systems: how agriculture can become more resilient in the face of climate change and resource scarcity.

The CFA identifies broad programming approaches to support three archetypical livelihood strategies aimed at poverty alleviation and agricultural development. These strategies involve supporting the poorest in rural areas while also helping farmers to build their incomes by increasing the value of their agricultural outputs and, where appropriate, to diversify away from agriculture:

- Helping farmers ‘stepping out’: long-term investment facilitating a transition away from rural agriculture by supporting i) labour-intensive sectors creating off-farm jobs (such as processing or packaging) and ii) rural people seeking to access employment outside of the agriculture sector.

- Helping farmers ‘stepping up’: stimulating agricultural transformation that supports smallholders to engage in commercial agriculture.

- Helping farmers ‘hanging in’: continued support for agricultural livelihoods of rural poor people until conditions are right for them to step up or step out.

The CFA also included three cross-cutting priorities: (i) nutritious and safe food, (ii) resilience to climate change and environmental sustainability and (iii) inclusion and gender.

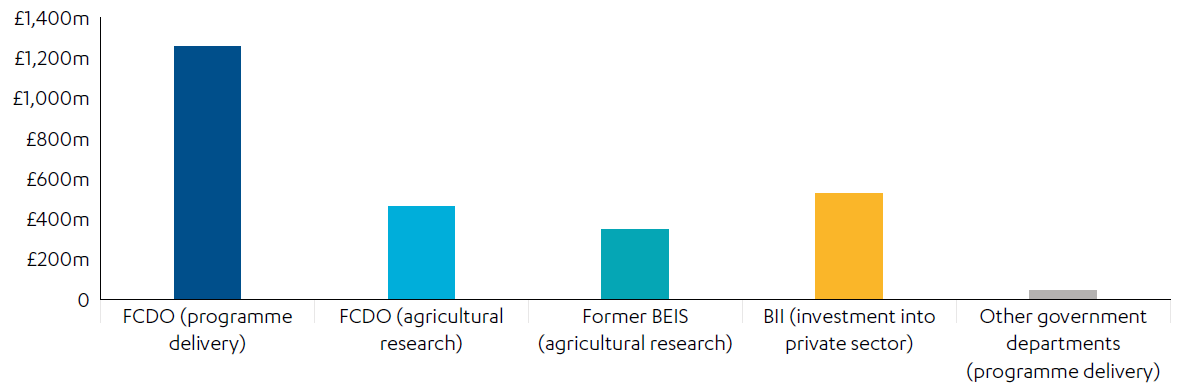

Figure 6: Bilateral UK aid to agriculture by government department, 2016-21

Source: Creditor Reporting System database, OECD.Stat; d-Portal, International Aid Transparency Initiative.

3.10 While all figures are indicative (see Box 2 in the Methodology section), between 2016 and 2021 DFID/FCDO was responsible for around 65% of UK ODA spend on agriculture, shared between its delivery and research activities (see Figure 6).

3.11 British International Investment (BII) represented one-fifth of UK bilateral aid to agriculture from 2016 to 2021, all of it in the form of investments. Investments by BII were governed by its 2017-21 strategic framework and, later, by its 2020 Food and agriculture sector strategy. BII focused on investments in agribusinesses and related industries to scale up agricultural productivity.

3.12 The former department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy (BEIS) (now the Department for Science, Innovation and Technology), oversaw 40% of the UK’s aid to agricultural research from 2016 to 2021, which was 13% of total bilateral aid to agriculture. BEIS-funded research, channelled through the Global Challenges Research Fund (GCRF), Newton Fund and other ODA portfolios, was managed by Research Councils UK, which became UK Research and Innovation in 2018. In February 2022 it was announced that no further funding would be available under the GCRF or Newton Fund, and a new International Science Partnerships Fund was announced in December 2022.

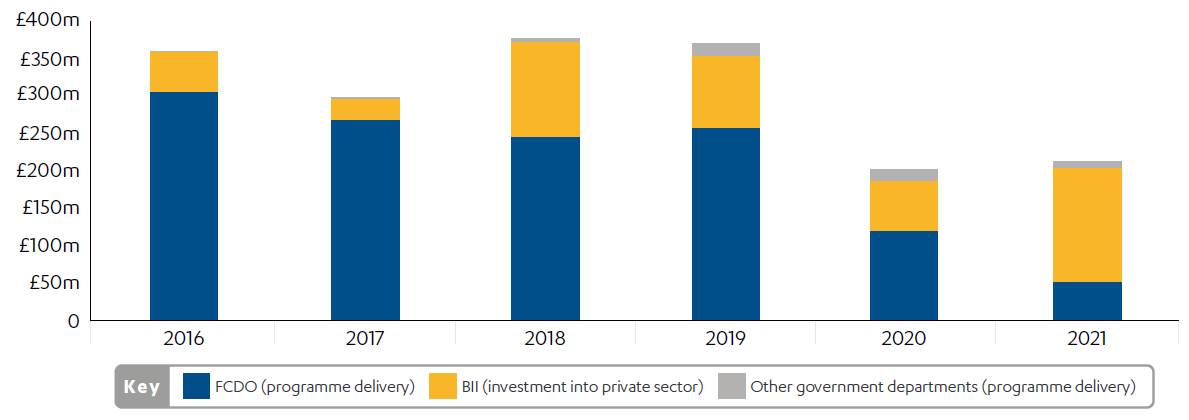

3.13 In the Findings section of this review, Part one covers grant funding for delivery programmes and investments, while Part two focuses on research. Delivery and investment are mainly funded through spending by FCDO and BII, with a relatively small amount of spending on agricultural delivery from other ODA-spending departments (see Figure 6). Between 2016 and 2021, almost 70% of the UK’s bilateral ODA portfolio on agriculture was either grant funding for delivery programmes, mainly from DFID/FCDO, or investments by BII. Over this period, grant funding by FCDO declined while average annual investments by BII increased (see Figure 7).

Figure 7: UK bilateral ODA funding for delivery programmes and investment spending by department, 2016-21

Source: Creditor Reporting System database, OECD.Stat; d-Portal, International Aid Transparency Initiative.

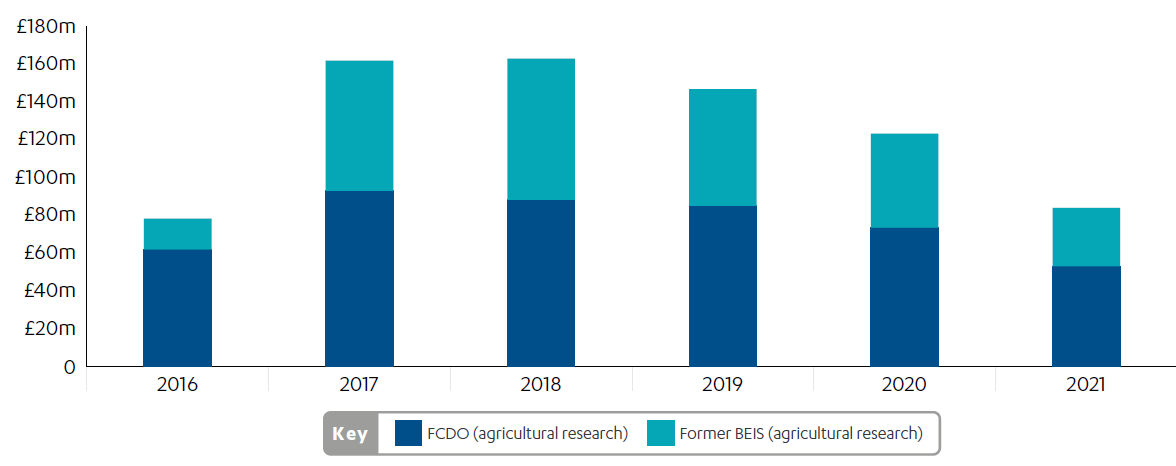

3.14 Overall, agricultural research spending increased rapidly between 2016 and 2018, and has since fallen year on year. The former BEIS first began spending ODA on agricultural research in 2016, initially accounting for 21% of annual spending. This rose to 46% in 2018, then fell to just over one-third by 2021 (see Figure 8).

Figure 8: Agricultural research spending by government department, 2016-21

Source: Creditor Reporting System database, OECD.Stat; d-Portal, International Aid Transparency Initiative.

3.15 We reviewed ten programmes (see Annex 1). In total, these programmes spent £791 million over the period of our review and represent a third of the UK’s overall agricultural portfolio by spend. In sampling and reviewing this portfolio we prioritised four thematic areas:

- smallholder commercialisation

- climate-smart agriculture

- nutrition-sensitive agriculture

- gender.

For further information about our programme sampling, please see our approach paper. For further information about the thematic areas, please see the relevant sections of our literature review.

4. Findings

4.1 In this section, we present our main findings on the UK’s official development assistance (ODA) for agriculture in a time of climate change. Part one looks at agricultural delivery programmes funded by the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO) (formerly the Department for International Development (DFID)) and investments made by British International Investment (BII). Part two covers ODA-funded agricultural research funded by DFID/FCDO and through the Global Challenges Research Fund (GCRF). Part three assesses the overall coherence of the portfolio. A summary assessment of the portfolio’s relevance, coherence and effectiveness is presented in the Conclusions and recommendations section.

Part one: The UK’s delivery programmes and investments in agriculture

DFID/FCDO’s targeting of smallholder commercialisation was a relevant, innovative and credible approach to poverty reduction

4.2 The 2015 Conceptual framework on agriculture (CFA), developed by the former DFID, articulated the department’s strategic approach to agriculture by identifying developmental relevance, and goals and priorities for effecting change. The CFA identified three strategies for reducing rural poverty and promoting inclusive growth (see Box 3). DFID’s agricultural delivery programmes emphasised two of these strategies: helping smallholder farmers to engage in commercial agriculture (‘stepping up’) and expanding their opportunities for off-farm employment by investing in agribusinesses (‘stepping out’). This helped align the work of DFID’s rural livelihoods cadre with the department’s growing interest in private sector development. DFID’s 2017 Economic development strategy re-emphasised smallholder commercialisation’s role in transforming rural economies, particularly in agriculture-dominated economies.

4.3 The CFA helped align different areas of DFID/FCDO’s support for rural poverty reduction. While agriculture programming moved away from supporting subsistence (‘hanging-in’) farmers, this group was supported through social protection and other resilience-building programmes. Programmes supporting access to financial services, infrastructure, education and economic growth in other sectors also supported the CFA’s ‘stepping up’ and ‘stepping out’ strategies.

4.4 Programmes in our sample and country case studies used several approaches related to smallholder commercialisation. These included:

- supporting community initiatives to diversify income and build resilience, such as replanting local watersheds and creating small enterprises to process local produce

- overcoming barriers to smallholders’ entrance into formal markets, for example by improving their access to seeds that meet buyers’ specifications

- overcoming disincentives for private sector firms to work with smallholder farmers, such as by demonstrating aggregation models that improve the reliability of supply

- investing in agribusinesses, enabling them to grow, create off-farm jobs and include more smallholders in their supply chains.

4.5 Smallholders reached by these interventions told us how they had benefited:

“We had a mindset of cultivating small quantities, because we didn’t have a market. Now we have a big market. We cultivate large quantities to satisfy the market. We make more money to buy other types of food.”

Woman, farmer, focus group discussion, Rwanda

“Some farmers have been able to buy livestock after harvesting and selling maize or beans from the programme and this is all because of SIVAP [Small-Scale Irrigation and Value Addition Project]. Personally, I built a house with iron sheets, I bought pigs, goats and one cattle because of the scheme; and I am not the only one, a lot of others would also testify.”

Woman, farmer, semi-structured interview, Malawi

“My life had previously been difficult due to my disability, but with this project, I am able to hire people to work for me on my tea plantation.”

Woman, tea farmer, semi-structured interview, Rwanda

4.6 The department’s programming was relevant throughout 2016-21, clearly shaped by the CFA, and frequently ambitious and innovative. In interviews, however, officials told us that changing ministerial priorities have shifted focus away from the CFA’s model for agricultural development and poverty reduction. Over our review period, grants and development finance increasingly targeted larger agribusinesses rather than small producers. In principle, such investments can benefit poverty reduction by creating jobs and stimulating economic growth. However, we found mixed evidence that these approaches were substantially benefiting smallholders. More recently, the 2022 International development strategy and 2023 Integrated review refresh refer to sustainable economic growth and sustainable agriculture, shifting the focus away from specific references to commercial agriculture.

Box 4: Overcoming market constraints in northern Nigeria

The Propcom Mai-karfi programme worked in eight agricultural and non-agricultural rural markets of northern Nigeria between 2012 and 2022. It used market systems approaches to improve market services for smallholders by identifying the constraints and incentives of market actors and facilitating sustainable changes. The programme’s first phase improved smallholders’ access to fertilisers, tractor hire, seeds and grain storage, among other goods and services. The programme’s second phase expanded into conflict-affected areas, testing the feasibility of market-based approaches in humanitarian situations.

Due to ODA budget reductions, Propcom Mai-karfi’s endline evaluation was cancelled. However, an independently produced Programme Completion Report found that the programme had delivered significant results in reducing poverty and women’s economic empowerment, but was less successful at encouraging humanitarian agencies to deliver market-based solutions. It also found that the best prospects for sustainability came in value chains the programme had engaged with for over seven years, having allowed sufficient time for consolidation and scaling up of activities.

4.7 In Malawi, Rwanda and Nigeria we saw DFID/FCDO programmes targeting smallholders directly that were complemented by programmes addressing key challenges in their enabling environment. In each country, these formed sophisticated, innovative and ambitious attempts to support growth in the agriculture sector. Several such programmes had contributed to transformative change or may yet do so.

4.8 In Rwanda, for example, long-standing DFID programmes had helped lower barriers for smallholders to invest in commercial agriculture, particularly by improving their access to finance and formal land tenure. These programmes helped prepare the ground for programmes that supported smallholder commercialisation directly. One programme supporting smallholder commercialisation directly was Improving Market Systems for Agriculture in Rwanda (IMSAR), which helped smallholders to improve yields and quality of produce and facilitated aggregation models that connected farmers with agribusinesses such as food processors. US officials told us that IMSAR’s example encouraged USAID to implement their own market systems approach in the country.

4.9 In Malawi we saw how economic growth programmes that were not badged as agriculture had targeted smallholders’ enabling environment. For instance, much of the support of the Private Sector Development in Malawi programme for private sector policy reforms and finance for private enterprises supported agricultural enterprises. Similarly, the subsequent Malawi Trade and Investment Programme (MTIP) aimed to improve the country’s agricultural exports. By stimulating growth in agribusinesses, both programmes potentially contributed to increased demand for smallholders’ produce. These approaches complemented interventions supporting smallholders directly, such as investments made by AgDevCo (a specialised investor in Africa’s agriculture sector funded by DFID/FCDO, BII and other donors). Many of these interventions also supported community agribusinesses to adapt to a changing business environment. For example, AgDevCo’s support for the Kasinthula sugar cooperative addressed management and financial problems, opening opportunities to create jobs and ultimately benefit from wider business environment reforms.

FCDO’s programmes have been largely effective in increasing incomes and creating jobs, particularly when working on a longer time scale

4.10 A recent review of FCDO’s commercial agriculture portfolio found that its 35 operational programmes had helped over 19 million farmers improve their incomes and contributed to the creation of over 231,000 jobs between 2015 and 2020.

4.11 Reports from our citizen engagement process were positive about the contribution FCDO’s programmes had made to their income and livelihoods:

“Having livestock and earnings from produce sales provided the much-needed alternative to migration for casual labour in Mozambique.”

Man, farmer, focus group discussion, Malawi

“Before I was making between RWF 70,000 to RWF 200,000. But I am now earning more than one million. The reason why is that I changed the way I grow maize.”

Woman, farmer, semi-structured interview, Rwanda

“I have more means now. I plan ahead of time how I will spend my money, and I no longer depend on my husband to buy stuff for the house.”

Woman, farmer, focus group discussion, Rwanda

4.12 One of the underlying reasons for supporting smallholder commercialisation is that farmers with increased incomes buy more local goods and services, contributing to inclusive rural growth. While few programmes monitored such impacts, our citizen engagement suggested that they were indeed happening:

“What changed is that they used to sell small quantities such as one kilogram or two. They used to get money inconsistently, which cannot help them. But now they receive money in a lump sum and can afford to buy products from my shop and I benefit too. I noticed that their profit reaches other people in the neighbourhood because farmers hire labourers who earn income from them, and I get profits too.”

Woman, small enterprise owner, semi-structured interview, Rwanda

“When farmers get money, our products sell fast. And we restock other products within a short time.”

Woman, small enterprise owner, semi-structured interview, Rwanda

“Another advantage is that many people now have jobs. People used to travel to other areas to look for money in the past. I received a loan of RWF 2 million, which I used in order to hire more people to do farming activities for me, and those people were also able to meet their household needs.”

Farmer, focus group discussion, Rwanda

4.13 We heard from UK officials and independent experts that achieving transformational results in commercial agriculture takes time. Our literature review confirmed this. Convincing smallholders, enterprises and investors to change their behaviour in a risky sector requires patience. Ensuring such change is embedded and sustainable often takes longer than the typical programming cycle of four to five years. An independent review of Market Development in the Niger Delta (MADE), for example, found that the programme’s two-year extension until 2020 allowed the consolidation of market system interventions made between 2013 and 2018. The number of farmers reached by MADE doubled between 2018 and 2020, as activities were scaled up and successful results encouraged additional private sector investment (‘crowding in’) and copying of behaviour by other farmers. Propcom Mai-karfi (see Box 4) was another example of a programme where an extension allowed for deepening impact and sustainability. Few programmes were followed by retrospective evaluations, however, limiting insights into their long-term sustainability and effectiveness.

BII’s development impact is less well evidenced, particularly in terms of benefits to smallholders

4.14 BII invests in the growth of commercial farms and large agribusinesses. Investing in the agriculture sector is high-risk. The risk is typically higher when investing in producers but lower when investing in agribusinesses situated further along supply chains, such as those engaged in food processing or manufacturing agricultural inputs. These risks make agriculture a challenging proposition for BII as it has a statutory obligation to realise a return on investment. BII’s primary approach is to invest more than £10 million directly in large, well-established businesses. However, there can be limited opportunities to do so in countries with underdeveloped private sectors, such as Malawi and Rwanda. To overcome this constraint, BII uses other models to broaden its options. For example, our sample included smaller indirect investments in Nigerian agribusinesses mediated through a local fund manager.

4.15 In our sample of investments, the analysis of development impact was generally weak and tended to assume anticipated benefits would follow investment. In principle, BII’s investments in business growth can benefit the wider economy, such as by generating exports. They may also benefit poor people more directly, for example by creating jobs and stimulating demand for smallholder produce. In practice, we found that BII’s reported results contained strong evidence for supporting business growth, although prospects for business sustainability were weakly analysed in some exit documents. However, we saw limited evidence for development benefits beyond job creation, particularly in investments mediated through local fund managers. For example, we saw no robust assessment of benefits such as import substitution or the reduction of post-harvest losses that were anticipated from some of the investments in our sample which were mediated through a local fund manager. Moreover, evidence for job creation was variable and we saw no analysis as to whether the jobs created met expectations for permanent or decent work, or who benefited from them. For example, a 2019 investment in a shea butter processing firm mediated through a local fund manager would most likely have increased its purchases from independent shea nut collectors, many of whom are women. However, investment documents, developed before BII’s revised development impact framework (see below), did not anticipate or monitor this impact.

4.16 Following a recommendation in ICAI’s 2019 review of investments by CDC (BII’s previous name) in low-income and fragile states, CDC required all new investments to be designed against a new development impact framework. Assessing progress on this recommendation after two years, ICAI concluded in 2021 that new investments were now taking into account certain development impacts satisfactorily, although there remained some areas of weakness, such as inclusion, nutrition and considerations of ‘who benefits’. Being quite recent, this greater focus on development impact largely applies to investments made towards the end of the review period.

The monitoring and evaluation of development outcomes across a diverse portfolio of delivery programmes and investments was of mixed quality and coverage, inhibiting learning

4.17 Monitoring, evaluation and learning (MEL) in DFID/FCDO programmes and BII investments was of mixed quality and coverage. Approaches to measuring development impact in DFID/FCDO programmes generally focused on numbers of jobs created, farmers reached or increases in income. There was no consistent approach to measurement and little attention to whether jobs created met accepted definitions of decent work. Few programmes monitored wider impact on inclusive growth. Building Resistance and Adapting to Climate Change (BRACC), in Malawi, was one of the exceptions, providing evidence that increased income among programme participants led to increased spending on goods, services and casual labour in local communities.

4.18 As noted above, BII’s reporting of benefits to poor people focused on job creation, and that was of variable quality. Only one investment in our sample reported on development impact beyond jobs created, an investment in Nigeria which attempted to evaluate its impacts on the substitution of rice imports. We note that BII developed a new approach to contextualise its reporting and provide a more comprehensive picture of development impact beyond enterprise growth towards the end of the review period. BII’s 2020 impact framework and its 2022 impact score methodology have the potential to introduce consistency and improve monitoring of how well investments reach low-income populations and whether impact is achieved beyond jobs created.

4.19 The UK deployed a wide variety of models and approaches to agricultural development in different contexts and value chains over 2016-21. To this should be added programmes such as Access to Finance Rwanda and MTIP, which address agriculture’s enabling environment. The variety of models and approaches constitutes a potentially rich evidence base from which to learn, inform future programming and provide evidence on ‘what works where and why’ to the wider development community. However, officials told us that inconsistent quality and coverage of MEL information, and a lack of retrospective evaluations of long-term impact, mean that this evidence base is not being developed or exploited to its full potential.

4.20 FCDO has invested in thematic evaluations and annual commercial agriculture portfolio reviews (CAPRs) of its delivery portfolio. The thematic evaluations provide some useful insights, but all of them reported challenges with drawing firm conclusions due to the limited evidence at their disposal. While the CAPRs report on results from across the commercial agriculture portfolio, they do not evaluate the factors that underlie or hamper these results. Their utility for learning is therefore limited. At the research portfolio level, DFID/FCDO has invested in embedding evaluations into its agriculture research programmes which have generated valuable lessons and are shared externally. However, while these have generated useful insights, they have not evaluated the success of the portfolio as a whole. BII had

not conducted any portfolio-wide evaluations to develop empirical learning on effective agricultural investment during 2016-21, although we understand that FCDO’s evaluation and learning programme has commissioned an evaluation of BII’s food and agriculture portfolio, which it expects to publish at the end of 2023.

4.21 These evidence gaps constrain the UK’s ability to capture lessons on success factors in different contexts, make evidence-based decisions and act as a thought leader in the development community.

There are improvements in strategic coherence between FCDO and BII, but opportunities for synergy between FCDO, BII and AgDevCo activities are not regularly being seized

4.22 DFID/FCDO and BII have not always been closely coordinated. A 2019 ICAI review recommended that BII (then named CDC) should work more systematically and regularly with DFID, particularly at the country level, and strengthen engagement with other parts of the UK aid programme. There are indications that closer senior-level discussions have improved strategic alignment since then. An example is BII’s recent investment in AgDevCo (see Box 5). This follows on from long-term DFID/FCDO support to AgDevCo, amounting to over £152 million during 2016-21. AgDevCo targets high-risk, early-stage firms with finance of between £2 million and £10 million, making it well placed to prepare a pipeline of firms which might, with growth, be suitable for BII investment.

Box 5: AgDevCo investment in agriculture AgDevCo invests long-term capital in, and provides technical support to, early-stage and higher-risk

African agribusinesses. AgDevCo’s investments have enabled small and medium enterprises to become more financially sustainable, potentially enabling them to access development finance to fund further growth.

In 2021, BII invested $50 million to help AgDevCo widen and deepen its impact and support continuing financial stability, and to demonstrate BII’s openness to investing in higher-risk businesses. BII’s investment has improved cooperation and reduced competition between BII and AgDevCo. It has the potential to enable both organisations to leverage their complementary strengths and coordinate investments along agricultural value chains and related services.

We heard from interviews that, following a reduction in grant financing, AgDevCo is shifting towards lower-risk investments. This was expected to be only temporary, until AgDevCo builds up its capital. While AgDevCo will retain an important offer to African agriculture, this new position does leave a significant gap in the market in terms of support for high-risk and early-stage firms.

4.23 After BII’s investment we found promising evidence of improved coordination between BII and AgDevCo in countries where both had a footprint. In Malawi, AgDevCo took over the management of BII’s investment in a macadamia plantation and bought BII’s investment in a sugar plantation. Both were relatively small investments for BII, and these moves reflect AgDevCo’s comparative advantage in managing smaller investments and supporting agricultural firms that work directly with smallholders.

4.24 However, we saw more examples of missed opportunities for operational coordination between FCDO delivery programmes and BII and AgDevCo investments. IMSAR is an example of this. IMSAR included both a delivery component with interventions to improve smallholders’ access to markets and an investment component, in which AgDevCo provided long-term finance to agribusinesses. IMSAR’s business case implies that the two components would collaborate, but did not specify how. In the event there was no collaboration. This was partly because the delivery component started two years after the investment component due to procurement delays. More significantly, there was a lack of financial and contractual incentives for AgDevCo and IMSAR’s delivery partners to collaborate. In particular, we were told by the UK government that the programme’s design did not offer material value to AgDevCo in making an impactful investment. The absence of effective coordination between development finance investments and grant-based delivery programmes makes it more challenging to develop smallholder-inclusive value chains as well as generate economic growth. Coordination options could, for example, include a delivery programme that trains smallholder farmers and aggregates their produce to supply a firm receiving AgDevCo investment.

The commercial agriculture portfolio’s climate relevance has improved rapidly from a low baseline, yet still lacks ambition

4.25 The UK’s work on agriculture has included a climate focus for over a decade. However, the UK’s strategic direction for climate and agriculture remains unclear. The 2015 CFA conceptualised climate change as a risk to yields, food security and prosperity, but few early commercial agriculture programmes emphasised climate adaptation and resilience. FCDO staff told us a revision of the CFA would now need a more ambitious and systematic approach to climate and environmental considerations that would likely incorporate nature and biodiversity issues. This reflects the department’s heightened understanding and prioritisation of these themes.

4.26 The climate relevance of BII’s agriculture investments improved between 2016 and 2021, from a low base. Its 2017-21 food and agriculture strategy encouraged inclusion of sustainability issues in investments. However, climate considerations were not routinely included. The level of ambition in BII’s earlier approaches to, and reporting of, environmental, social and governance (ESG) standards was also variable. BII’s 2020 climate strategy commits all new investments to align with the Paris Agreement on climate change and requires 30% of all annual investment commitments to be climate finance.

4.27 Between 2016 and 2021, DFID/FCDO’s commercial agriculture portfolio also improved its focus on the climate crisis. Between 2018 and 2021, the number of DFID/FCDO commercial agriculture programmes using the UK’s International Climate Finance (ICF) budget doubled, from 15 to 31. This is a broadly positive indicator and correlates with increasing prioritisation of climate objectives and action by FCDO.

4.28 However, claiming ICF funding does not necessarily mean high performance on climate action. Eight programmes that were operational but not claiming ICF budgets in 2018 were claiming ICF budgets by 2021. Some interviewees expressed concerns that programmes were using ringfenced ICF budgets to secure funding in a context of ODA budget reductions. Some programmes which come under ICF, including the Future of Agriculture in Rwanda and Commercial Agriculture for Smallholders and Agribusiness (CASA), were rated poorly against all climate objectives by a recent CAPR.