UK aid to India

Score summary

The new model of development cooperation that has emerged in India has resulted in a fragmented portfolio without a strong development rationale

In recent years, the UK has transitioned away from funding traditional poverty-focused aid projects in India, but still provides substantial aid in the form of development investment, research partnerships and other activities that support the bilateral relationship. We calculate that the UK provided around £2.3 billion in aid between 2016 and 2021, including £441 million in bilateral aid, £129 million in development investment via the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office into Indian enterprises which generates returns, £749 million through multilateral channels, and £1 billion in investments through British International Investment (BII), the UK’s development finance institution. We find that, while the portfolio reflects the shared interests of the UK and Indian governments, it is fragmented across activities and spending channels, and lacks a compelling development rationale. BII invests 28% of its global portfolio by value in India, but much of its portfolio lacks strong ‘financial additionality’ (given India’s relatively mature financial markets) and does not have a clear link to inclusive growth and poverty reduction. UK aid has built research partnerships between UK and Indian institutions on global development challenges, but the research is weakly integrated with the rest of the portfolio. The UK’s support to India’s emerging role as an aid donor lacks a strong focus on results. There is little UK support for Indian democracy and human rights, despite negative trends in these areas.

While we have concerns about the model of development cooperation that has emerged in India, there are areas of strength within the country portfolio. The programming is generally well managed and delivered. The UK has maintained good relationships with the Indian government and has demonstrated that well-targeted technical assistance can have a positive influence on India’s policy and investment choices, although this support has been scaled back during recent aid budget reductions. The UK has provided innovative support on climate change and clean energy, showing the value of combining support for policy reforms with well-targeted development investments.

| Individual question scores | |

|---|---|

| Relevance: How relevant is the UK’s evolving model for development cooperation with India? |  |

| Coherence: How internally and externally coherent has the UK’s official development assistance and associated diplomatic activity been in India? |  |

| Effectiveness: How effective has the UK aid portfolio been in achieving its strategic objectives in India? |  |

Acronyms and glossary

| Acronyms | |

| BEIS | Former Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy (now the Department for Science, Innovation and Technology and the Department for Business and Trade) |

| BII | British International Investment (formerly CDC Group) |

| CDP | Cassa Depositi e Prestiti (Italian investment bank) |

| CIF | Climate Investment Funds |

| CTF | Clean Technology Fund |

| DEG | Deutsche Investitions- und Entwicklungsgesellschaft (German Investment and Development Corporation) |

| DevCap | Development capital |

| DFC | United States International Development Finance Corporation |

| DFI | Development finance institution |

| DFID | Department for International Development (merged with the Foreign and Commonwealth Office in September 2020) |

| DHSC | Department of Health and Social Care |

| ESG | Environmental, social and governance |

| FCDO | Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office |

| FCO | Foreign and Commonwealth Office (merged with the Department for International Development in September 2020) |

| FMO | Nederlandse Financierings-Maatschappij voor Ontwikkelingslanden N.V. (Dutch Entrepreneurial Development Bank) |

| GCRF | Global Challenges Research Fund |

| GDP | Gross domestic product |

| GGEF | Green Growth Equity Fund |

| GHR | Global Health Research portfolio (delivered by the UK’s National Institute for Health and Care Research) |

| GIP | Global Innovation Partnership |

| GIZ | Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit GmbH (German development agency) |

| GNI | Gross national income |

| ICAI | Independent Commission for Aid Impact |

| IDA | International Development Association |

| ILO | International Labour Organisation |

| INVENT | Innovative Ventures & Technologies for Development Programme |

| JICA | Japan International Cooperation Agency |

| KPI | Key performance indicator |

| MFI | Microfinance institution |

| MSME | Micro, small and medium enterprises |

| NDC | Nationally determined contributions |

| NIHR | National Institute for Health and Care Research (UK) |

| NIIF | National Investment and Infrastructure Fund |

| NGO | Non-governmental organisation |

| ODA | Official development assistance |

| OECD | Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development |

| RBI | Reserve Bank of India |

| SC | Scheduled Castes |

| SIDBI | Small Industries Development Bank of India |

| SME | Small and medium enterprises |

| ST | Scheduled Tribes |

| UN | United Nations |

| UNDP | United Nations Development Programme |

| UNICEF | United Nations International Children’s Fund |

| USAID | United States Agency for International Development |

| Glossary of key terms | |

| Additionality | In respect of development investment, a contribution beyond what is already available from the private sector. |

| Bilateral aid | Flows from official (government) sources directly to the recipient country. |

| Central funds | Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office and other government funds operating on a global and regional basis and managed from the UK. |

| Debt investment | Financial resources to a borrower over a prescribed period with the expectation that the money will be repaid with interest. |

| Development investment | Aid-funded investments (usually, loans or equity investment) that are intended to generate development impact along with a modest financial return. |

| Development finance institution | Specialised institutions set up to provide concessional finance, investment and other support for development in low- and middle-income countries. |

| Environmental, social and governance | A set of environmental, social and governance principles used to measure the sustainability and social impact of business activities, and by investors to evaluate corporate behaviour. |

| Equity investment | Investments that involve taking a shareholding in a company, and thereby obtaining the right to receive a share of future profits. |

| Gross domestic product | A standard measure of the value created through the production of goods and services in a country during a certain period. |

| Gross national income | The total amount of money earned by a nation’s people and businesses. It includes a nation’s GDP in addition to the income it receives from overseas sources. |

| Microfinance | Financial services provided to low-income clients, including households and informal businesses, who traditionally lack access to banking and related services. |

| Mobilisation | In respect of development investment, the effect of stimulating other investment, typically from the private sector. |

| Multilateral aid | Core contributions from official (government) sources to multilateral agencies, which use them to fund their own developmental programmes. |

| Official development assistance | Government aid that promotes and specifically targets the economic development and welfare of developing countries. |

| Overseas mission | The UK’s diplomatic representation in other countries. |

| Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes | Officially designated groups of people who are among the most disadvantaged socio-economic groups in India and are provided with a range of public support, including protective arrangements, affirmative action and socio-economic development. Scheduled Castes (also known as ‘Dalit’) are made up of traditionally ostracised groups and those relegated to lower occupations, while Scheduled Tribes are made up of indigenous peoples that have distinct cultures and often live in isolated areas. |

| Venture capital | Capital investment in early-stage, innovative businesses that offer high risks but strong growth potential. |

Executive summary

In 2012 the UK government announced that it would transition away from funding India’s government to implement traditional aid projects, and towards a new kind of partnership based on mutual interests. The transition was agreed with the Indian government and reflected India’s growing economic strength. While India continued to experience high levels of poverty, bilateral aid was no longer a significant source of funding for its national development.

A decade later, the UK still provides a substantial amount of aid to India, but it is very different in nature and purpose. In 2021 India was the 11th-largest recipient of UK bilateral aid, ahead of countries such as Bangladesh and Kenya. While the UK no longer funds traditional development projects, India is the largest recipient of UK development investment – that is, loans and equity investments into the private sector that aim to achieve development impact alongside a modest financial return. The UK’s development finance institution, British International Investment (BII, formerly CDC Group), has invested 28% of its global portfolio by value in India, and the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO) also runs a development investment portfolio of its own (‘FCDO DevCap’) which produces returns, in principle, saving taxpayer money. UK aid also supports UK-India research partnerships, alongside a range of other objectives agreed in a 2021 ‘governing the bilateral partnership. FCDO describes the India portfolio as an exemplar of the new model of development partnership signalled in the 2022 Strategy for international development, where aid is used in support of an integrated UK foreign policy. All told, we calculate that around £2.3 billion in UK aid went to India between 2016 and 2021, including £441 million in bilateral aid, £129 million in investments via FCDO in Indian enterprises which generate returns, £749 through multilateral channels, and £1 billion in investments through BII. BII’s substantial portfolio of investments in India has been generating returns, but these are reinvested to help it meet its global financial returns target.

This country portfolio review examines the UK’s new model of development cooperation with India, covering all UK aid since 2016. The review considers its relevance to the mutually agreed development objectives, its coherence across spending channels, and whether it is achieving its intended results.

Relevance: How relevant is the UK’s evolving model for development cooperation with India?

The transition away from traditional aid to the government was a justifiable response to India’s strong economic performance and its increased access to development finance. The development case for continued UK aid to India rests on it playing a catalytic role, by influencing Indian government policies and investments or mobilising private finance into areas that contribute to inclusive growth, such as renewable energy. The International Development Committee reached a similar conclusion in 2011. The transition also reflects a longstanding preference of the Indian government for a partnership of equals, rather than a traditional donor-recipient relationship, as well as evolving UK government policy on the use of aid to support bilateral partnerships with middle-income countries.

However, the aid portfolio does not map neatly onto the objectives of the 2021 Roadmap, making it difficult to discern a clear overall strategy. Programming is fragmented across objectives and spending channels, rather than thematically integrated. We saw little consideration of the scale of support required for meaningful impact in different areas – especially since the recent UK aid budget reductions, which led to many activities being scaled back. Many of the activities appear focused on facilitating the bilateral partnership and lack a compelling link to poverty reduction, which remains the statutory purpose of UK aid.

The most convincing part of the portfolio is about climate change, where the UK is supporting India’s transition to low-carbon development. This appears a sound choice, given the importance of reducing emissions from India’s large and rapidly growing economy, which will benefit the poor in India and around the world. The UK supports the development of green infrastructure, particularly renewable energy, combining technical assistance to government with development investments designed to support innovation and stimulate private investment.

The UK’s development investment in India shows a mixed picture on ‘additionality’ – that is, ensuring it does not duplicate what is already available from financial markets. FCDO DevCap focuses on equity investments in small and innovative businesses, and on green infrastructure, which is an underdeveloped sector in India. It works closely with the Indian government and government-linked financial institutions, with which it has established joint investment funds and platforms, giving it the potential to influence the investment practices of much larger institutions. We find that FCDO DevCap makes a reasonable case for additionality. We were less convinced by elements of BII’s India portfolio. Nearly half (45%, by value) of investments have been in financial services, especially microfinance. However, the financial services it supports are already widely available in India’s relatively mature financial markets, and there is limited evidence that the growth of the microfinance sector in India has contributed to poverty reduction.

One of the objectives of the UK’s India portfolio is to support India’s engagement on global and regional development issues. We saw some strong examples of regional programmes that support collaboration between India and its neighbours, in particular on the management of transboundary water resources, which is a key strategic issue in the region. We were less convinced by the UK’s approach to supporting India’s emerging global aid programme. The UK supports ‘triangular cooperation’ by co-funding initiatives intended to share Indian development know-how and private sector innovations with low-income countries in Africa and the Asia-Pacific region. While there are multiple initiatives supporting dialogue between UK and Indian institutions on global development issues, the potential benefits to low-income countries seem remote.

The UK has invested around £400 million on promoting research partnerships between UK and Indian universities and research institutes, mostly from central funds. The Global Challenges Research Fund and Global Health Research select their thematic priorities at the global level. While broadly relevant, they are not specifically tailored to India’s needs. The Newton Fund has India-specific research priorities agreed between the two countries, addressing topics such as sustainable cities and the energy-water-food nexus, which are aligned with Roadmap priorities. While the research funding supports the objective of promoting bilateral cooperation in the research sector, it is not designed to support the UK’s development objectives in India and lacks a strong focus on promoting uptake of findings.

According to global indices, democracy and human rights have come under increasing pressure in India in recent years, in the face of growing political polarisation, religious intolerance and restrictions on civil society. The UK has not been active in this area in recent years, either in its aid programme or in its development diplomacy. There is little or no programming designed to protect democratic space, free media or human rights, and UK funding for Indian non-governmental organisations (NGOs) has largely been discontinued. While we acknowledge the acute political sensitivities, we take the view that there are missed opportunities to contribute to protecting India’s longstanding democratic traditions – for example, by supporting civil society coalitions working on social issues.

Overall, we award an amber-red score for relevance. While UK aid to India reflects the shared interests of the two governments, it is fragmented across activities and spending channels, and lacks a convincing development rationale.

Coherence: How internally and externally coherent has the UK’s official development assistance and associated diplomatic activity been in India?

India is the UK’s largest overseas mission, consisting of 830 staff across 11 in-country posts and a large London-based team, with 17 UK departments and agencies represented. This makes effective coordination a perennial challenge. We find that coordination has improved over the review period, with a much clearer governance structure and a number of cross-departmental thematic teams. This structure works well in response to high-profile events (such as the COP26 climate conference in Glasgow in 2021) and situations (such as the response to COVID-19). However, we were not convinced that the India aid portfolio is being managed at a strategic level to promote complementary approaches across thematically linked activities. In particular, research activities are rarely linked to the rest of the portfolio. While the UK’s two development investment portfolios in India have distinct roles and complementary approaches, there is scope for them to collaborate more effectively. Technical assistance is not always combined with investment to maximise impact. There were, however, some positive exceptions. The UK’s work in the power sector, for example, shows the value of coordination across technical assistance and development investment.

The coherence of the portfolio has been further undermined by recent UK aid budget reductions. While the reductions to the India programme were not as severe as those faced by other countries, they led to key activities being discontinued or scaled back abruptly, leaving little space for strategic reprioritisation of the aid portfolio. Long periods of uncertainty and poor communication have also put relationships with Indian counterparts at risk.

The UK’s partnership with the Indian government is generally positive, and the UK is seen as responsive to Indian priorities although this has reduced with lower budgets. There is frequent dialogue between the two governments at multiple levels, and we saw good examples of collaboration across the programmes we reviewed. The UK has also prioritised building a strong relationship with the World Bank, which is a sound choice in the Indian context. It has agreed to provide a $1 billion guarantee that will enable the World Bank to provide additional climate finance equivalent to this amount to India. Partnership with other development partners is more limited but constructive. Like most other bilateral donors, the UK no longer works closely with Indian civil society due to political sensitivities and government restrictions on NGOs’ ability to accept foreign finance.

We award an amber-red score for coherence. While we welcome the efforts made to strengthen internal coordination, and recognise the good partnerships with the Indian government and the World Bank, we find limited evidence that the portfolio is being managed as a coherent whole, making the most of the investment, and note that the budget reductions have had a negative impact on coherence.

Effectiveness: How effective has the UK aid portfolio been in achieving its strategic objectives in India?

There have been commendable efforts to put in place a results framework for the UK government in India, with monitoring and reporting against 108 key performance indicators (KPIs). However, the KPIs do not meaningfully distinguish between activities, outputs and results. Some are process indicators (for example, tracking the holding of particular events like ministerial dialogues). Of the few that measure development results for India, most are yet to generate data.

In the 2017-20 period, the former Department for International Development delivered well against its objectives on basic services and financial inclusion, but these programming areas have now been discontinued. FCDO reports positive results in the areas of climate, clean energy and green finance, and some successes in promoting trade and regulatory reforms, but the data do not provide a clear picture on development results for India.

We did, however, find that most of the programmes we reviewed in detail were well managed and aligned with good development practice. We found good results from UK technical assistance programmes at federal and state levels, with a particularly strong UK contribution in the area of power sector reform, where relatively small UK expenditure (approximately £14 million) has been able to achieve catalytic impact, on the back of many years of investment in building up relationships and a deep knowledge of the sector. However, much of the UK’s technical assistance work was discontinued or cut back during recent budget reductions.

We also found good results on climate change, where the UK has helped India scale up its clean energy generation, while supporting private sector-led green initiatives in areas such as waste management and sustainable agriculture. However, progress towards the goal of mobilising large-scale private finance into green infrastructure remains at an early stage and new funds, while promising, remain nascent.

The two development investment portfolios report positive results on economic growth and job creation. BII data suggest that, between 2017 and 2021, its investments created over 170,000 jobs in investee firms, and over 3 million jobs through their wider economic effects (the latter figure is estimated through modelling, using a method common among development finance institutions, rather than a direct measurement). We found some evidence of the FCDO DevCap portfolio having transformative impacts by helping to build new markets and promoting innovation, particularly in clean energy. However, we were not convinced that BII’s large India portfolio is making a strong contribution to inclusive growth and poverty reduction, with many of its investments providing benefits to middle-class consumers, rather than the poor. One BII study found that only 30% of those benefiting belong to the bottom 60% of India’s population by income. One major investment in an Indian bank, intended to expand financial services for the poor, in fact, led mainly to expansion of the bank’s credit card business and corporate lending.

Overall, despite weaknesses in the results data, we find that UK aid to India is generally delivering well against the objectives set for it, meriting an amber-green score for effectiveness.

Recommendations

We have a number of concerns about the model of development cooperation that has emerged in India, which we find lacks a strong development rationale. However, there are also clear areas of strength in the country portfolio. The following recommendations are intended to help the UK government build on those strengths.

Recommendation 1: The UK should focus its aid portfolio to India on a limited number of areas where UK aid can help make India’s economic growth more inclusive and pro-poor, with clear theories of change to guide the design of aid programming and development diplomacy.

Recommendation 2: The UK should build on its emerging success story in climate finance and green infrastructure, looking for opportunities to combine technical assistance, research partnerships, development investments and multilateral partnerships for greater impact and value for money.

Recommendation 3: UK development investments should have a greater focus on mobilising private finance at scale to address climate change, particularly from large institutional investors based in the City of London.

Recommendation 4: British International Investment should reassess its approach to ensuring additionality in its India portfolio.

Recommendation 5: The UK should look for opportunities to support coalitions of Indian research institutions and non-governmental organisations working on social issues, in support of the UK India Country Plan goal of championing open societies and democratic standards.

1. Introduction

1.1 India has become a major economic power, with a growing geopolitical role. Over the past two decades, it has made impressive progress on promoting economic growth, and is projected to become the world’s fourth-largest economy by 2030. It still faces major social and economic challenges, and is home to 24% of the world’s poor. However, aid is no longer regarded as a significant source of development finance. In fact, according to the Indian government, in recent years, India has given more aid than it has received.

1.2 India’s growth has led to a major change in its development partnership with the UK. For many years India was the largest recipient of UK aid, with a wide range of programmes designed to help tackle extreme poverty in its poorest states. In 2012 the UK announced that it would phase out bilateral financial aid to India by 2015 (that is, grants to the federal and state governments), but would continue with other forms of assistance, including technical assistance and development-oriented investment in the private sector (‘development investment’). The announcement followed concerns raised by the International Development Committee and in the British media about the merits of continuing with traditional aid. The two governments agreed to recast their relationship as a partnership of equals, based on mutual interests. In 2021 this was formalised in a ‘Roadmap’, setting out a range of objectives for bilateral cooperation, including trade and mutual prosperity, collaboration on science and technology, and tackling climate change and global health challenges.

1.3 From 2015 the UK significantly reduced its aid to India. From having been the second-largest recipient of UK bilateral aid in 2014, in 2016 India no longer ranked among the top 20. However, the reduction in grant aid was partly offset by a growing development investment portfolio. The UK’s development finance institution, British International Investment (BII, formerly CDC Group), has since then invested 28% of its global portfolio by value in India, having made £1.2 billion of new investment commitments between 2017 and 2021. FCDO manages a development investment portfolio in India (‘FCDO DevCap’) – the only country where it does so. There is also a substantial volume of aid-funded research cooperation, mostly from global research funds. Moreover, during recent reductions to the UK aid budget, the India portfolio was protected to a greater degree than most other countries, causing it to become the 11th-largest recipient of UK bilateral aid, ahead of countries like Nepal, Bangladesh, Kenya and Uganda. Overall, between 2016 and 2021, we estimate that around £2.3 billion in UK aid went to India.

1.4 While there are still substantial volumes of UK aid to India, it is now very different in nature and purpose. It supports a range of Roadmap objectives under the comprehensive strategic partnership, serving as a tool for UK foreign policy, diplomatic and trade objectives. This puts the India country portfolio at the forefront of the vision for UK aid set out in the UK’s 2022 Strategy for international development.

1.5 This country portfolio review (see Box 1) examines the UK’s new model of development cooperation with India, as it has emerged since 2016. The review considers its relevance to the objectives of both countries, its coherence across spending channels and departments, and whether it is achieving its intended results. Our review questions are set out in Table 1.

1.6 The review builds on previous scrutiny of UK aid spending in India, including the 2011 International Development Committee inquiry and a 2016 Independent Commission for Aid Impact (ICAI) review of the former Department for International Development’s approach to managing exit and transition, in which UK bilateral aid to India was a case study.

Box 1: What is an ICAI country portfolio review?

An ICAI country portfolio review is a strategic assessment of the totality of UK aid, from all departments, funds and organisations, in a given country. This includes both bilateral and multilateral aid, as well as aid-related diplomacy.

India was selected for a country portfolio review as an example of the new mode of development cooperation signalled in the March 2021 Integrated review of security, defence, development and foreign policy, which stated that the UK government “will more effectively combine our diplomacy and aid with trade”. The May 2022 International development strategy also emphasised the need for the UK to use all its capabilities, including “diplomatic influence, trade policy, defence, intelligence, business partnerships and development expertise” to achieve development objectives.

Table 1: Review questions

| Review criteria and questions | Sub-questions |

|---|---|

| 1. Relevance: How relevant is the UK’s evolving model for development cooperation with India? | • How well has the UK understood and adapted its development cooperation to the evolving economic, social and political context in India? • To what extent is UK aid to India governed by a clear set of objectives supporting the shared interests of the two countries? • To what extent is UK aid to India guided by a clear understanding of the UK’s comparative advantage? |

| 2. Coherence: How internally and externally coherent has the UK’s official development assistance and associated diplomatic activity been in India? | • How coordinated are the instruments and channels through which the UK provides aid to India? • How well has the UK built partnerships with, and influenced, other bilateral donors, multilateral agencies, national civil society organisations and other actors? • How well do the UK’s diplomatic activities support its development objectives? |

| 3. Effectiveness: How effective has the UK aid portfolio been in achieving its strategic objectives in India? | • How effectively has UK technical assistance and research funding helped to strengthen Indian institutions and capacities? • How effective have UK capital investments been in promoting inclusive, sustainable and green growth through the portfolio? • How well do UK multilateral aid and partnerships contribute to India’s development? |

2. Methodology

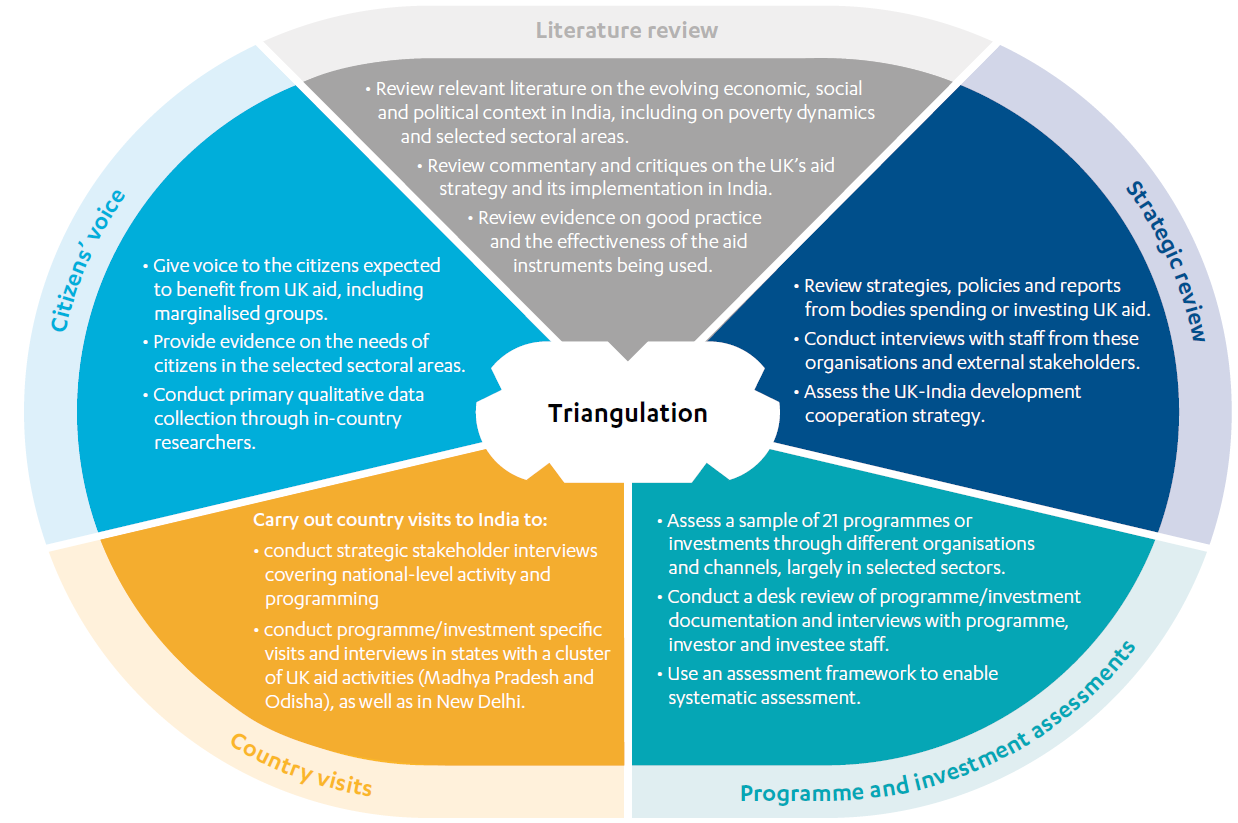

2.1 The review methodology included the following components, to allow for data triangulation to answer the review questions (see Figure 1). Methodological limitations are outlined in Box 2.

Figure 1: Methodology wheel

- Component 1 – Literature review: To assess the relevance of the UK’s approach to development cooperation with India, we reviewed literature on the changing economic, social and political context, particularly on the themes and sectors that are the focus of UK aid. We reviewed commentary on UK aid to India. To enable us to assess UK aid against good practice, we reviewed literature on the effectiveness of the major aid instruments being used (development investment, technical assistance and research funding), and looked at the approaches taken by other development partners in India (the World Bank, the Asian Development Bank and bilateral donors). The literature review, which is published separately, summarises key issues and conclusions from both academic and ‘grey’ literature, commenting where appropriate on the quality of evidence underlying the main conclusions.

- Component 2 – Strategic review: We examined strategies, policies and plans and interviewed relevant staff from UK government bodies, including British International Investment (BII), that are spending or investing UK aid in India. We also interviewed external stakeholders, including representatives of Indian institutions and civil society, other development partners and academic experts. We assessed the UK government’s understanding of the Indian context and its own comparative advantage as a donor, the clarity of the objectives guiding UK aid, how coherently UK development cooperation with India has been implemented (including the use of diplomacy to support development objectives), and how well the UK has built partnerships with, and influenced, others.

- Component 3 – Programme and investment assessments: We conducted desk reviews of a sample of 21 programmes and investments through different organisations, channels and instruments (see Annex 1 for our sampling approach and full details of selected programmes and investments). We reviewed business and investment cases, monitoring results and evaluations, and interviewed the responsible UK officials, implementing partners, investees and counterparts. We developed a framework for systematic assessment of these programmes and investments, to identify strengths and weaknesses across the sample.

- Component 4 – Country visits: Visits to India allowed us to engage with a wide variety of stakeholders, visit programme and investment locations, and engage with members of communities intended to benefit from UK aid investments. We visited New Delhi, primarily to meet with strategic stakeholders, and travelled to the states of Madhya Pradesh and Odisha, where there are clusters of UK-funded programmes and investments. We also briefly visited programmes and investments in Maharashtra.

- Component 5 – Citizens’ voice: Through an Indian research partner, Participatory Research in Asia, we collected feedback from Indian citizens through focus groups and interviews, with a focus on people expected to benefit from UK programmes and investments, including marginalised groups. The research was supported by local civil society organisations in Madhya Pradesh, Odisha, Maharashtra and New Delhi.

Box 2: Limitations to the methodology

The review period covers a period of considerable change and disruption in the UK aid programme, including from the merger of DFID and FCO, the COVID-19 pandemic and successive large-scale reductions to the UK aid budget. This disruption has affected institutional memory of UK aid since 2016, and also limited the extent to which it is possible to reach firm conclusions on the effectiveness of new approaches.

The India aid portfolio is designed to support various mutual objectives in the bilateral partnership, and these have evolved over the review period and are not always clearly articulated. This makes it difficult to assess aggregate results at the portfolio level.

It is inherently difficult to assess the impact of development investments, due to numerous shifts in investment strategy over the review period, the long-term nature of many of the investments, and the difficulty of measuring key variables such as ‘additionality’ (see paragraph 4.21). We have attempted to fill gaps in the evidence on investment results through our own primary research, but our ability to do so was necessarily limited by time and budget constraints.

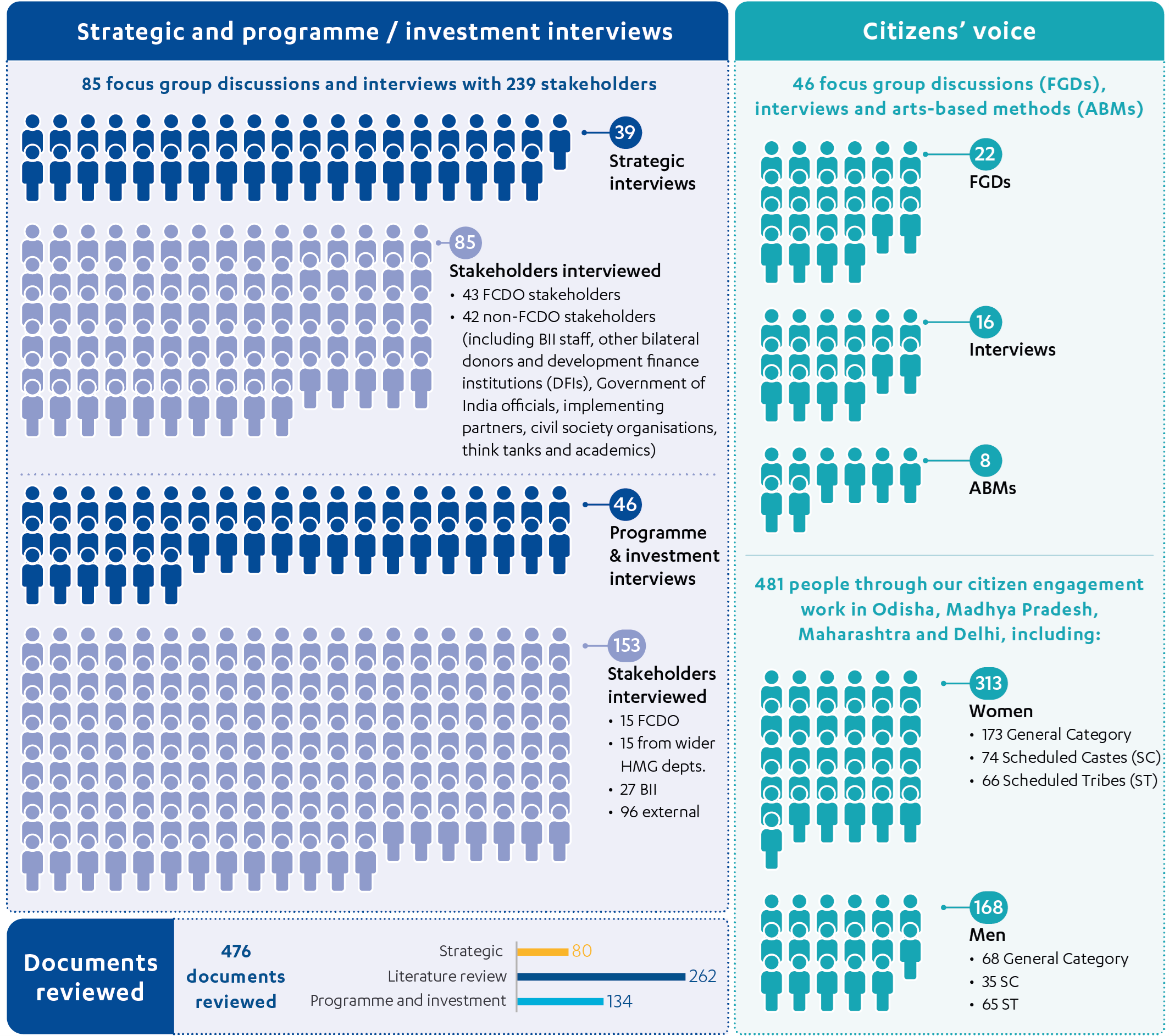

Figure 2: Our data collection

3. Background

India is a major power, but with major challenges still to overcome

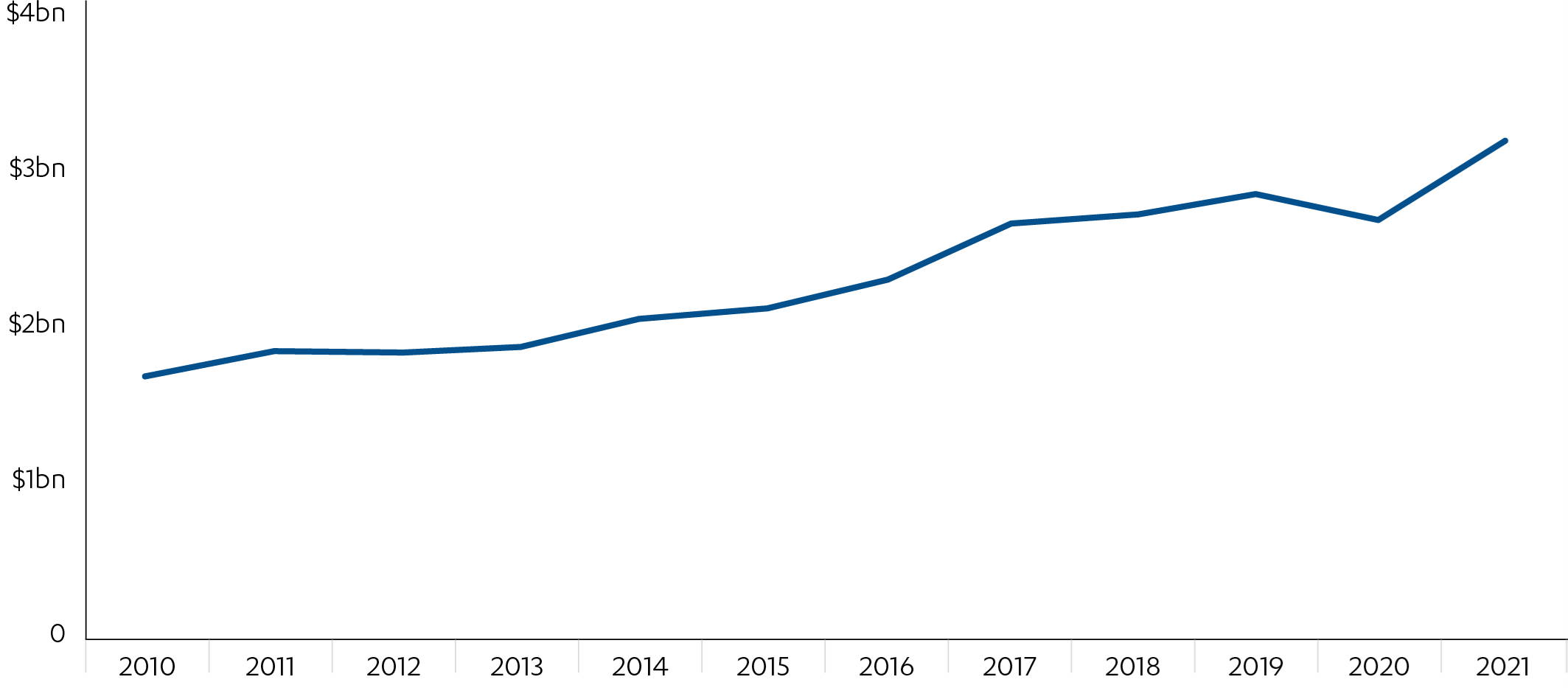

3.1 India has undergone an extraordinary economic transformation over the past 20 years. Its economic growth exceeded 7% in each of the ten years before the COVID-19 pandemic, putting it on a path to becoming the world’s fourth-largest economy by 2030 (see Figure 3). Its economy is increasingly diversified, with a vibrant services sector (including outsourcing and information technology) and rapidly growing industries, alongside a large and more traditional agricultural sector. The economy contracted by 7.3% in 2020-21 with the impact of COVID-19, but has rebounded quickly.

3.2 Economic growth has, in turn, increased the resources available for national development. Government funding for public services and infrastructure has increased, while public debt remains sustainable. India is an attractive market for foreign investment, and its relatively mature banking sector and capital markets help to mobilise domestic resources for private investment. There is a well-developed microfinance sector for small and micro businesses, with small-scale lending increasingly available through commercial institutions.

Figure 3: India’s nominal gross domestic product (current $ billions), 2010-21

Source: India – World Bank data, World Bank.

3.3 Economic growth has delivered impressive gains in poverty reduction. In 2011 some 22.5% of people lived in extreme poverty; by 2019 this had fallen to 10%. On the Global Multidimensional Poverty Index, which covers health, education and standard of living, 415 million people exited ‘multidimensional poverty’ in the 15 years between 2005 and 2020, before the COVID-19 pandemic, including 140 million people since 2015. However, poverty remains a widespread challenge. On the United Nations (UN) Human Development Index, which measures income, education and life expectancy, India still ranks just 132nd out of 191 countries and territories. According to the Global Hunger Index, it faces ‘serious’ levels of hunger, ranking 107th among the 121 countries where data are available, with 17% of the population undernourished. Among children under five, stunting (low height-for-age) and wasting (low weight-for-height) are at 36% and 20% respectively. Poverty is heavily concentrated in the poorest states, in rural areas, among workers in the informal economy, and among marginalised and excluded social groups. Gender inequality is also acute. Although India now has more women than men for the first time in its recorded history, with 1,020 women for every 1,000 men, the sex ratio at birth remains low, with 929 girls born for every 1,000 boys, indicating continued preference for male offspring. Only 20.5% of working-age women are active in the labour force, compared to 76.1% of men.

3.4 India is a key country for global climate action. Given its large and rapidly growing economy, India’s ability to transition to a low-carbon development path will be pivotal in determining whether the planet remains within the two-degree global warming threshold. India also faces serious environmental challenges in managing its scarce water resources, modernising its food systems and ensuring its megacities and diverse urban environments remain inclusive and sustainable. Climate change pressures are likely to fall disproportionately on the poorest states and communities, which are vulnerable to both flooding and heatwaves.

3.5 At the COP26 climate conference in 2021, India pledged to reach net zero emissions by 2070 and to produce half of its energy from renewables by 2030. These pledges have since been formalised in India’s nationally determined contributions (NDCs, voluntary actions under the Paris climate agreement) in August 2022, and have been followed by a number of new policy initiatives. In November 2022, India released a long-term low-carbon development strategy, which includes actions to promote low-carbon transition in electricity generation, transport, industry, cities, agriculture and forests. The government has also promoted a ‘Lifestyle for Environment’ movement to encourage citizens to combat climate change. However, India has faced criticism for its slow transition timetable and its commitment merely to ‘phase down’, rather than phase out, its use of coal. Since COP26, India has backed away from its NDC commitment to installing 500 gigawatts of renewable energy capacity, although this remains a domestic target, and has kept open the option of new coal-based power plants. Currently, 70% of India’s power comes from coal. While renewables are growing rapidly, they account for only 18% of generation, leaving the country without a clear pathway to net zero.

3.6 Over the review period, India has fallen significantly on global democracy indices. The Democracy Index 2021 notes a “serious deterioration in the quality of democracy” since 2016, linked to the government’s failure to prevent “increased intolerance and sectarianism towards Muslims and other religious minorities”. India’s ranking on the index has declined from 32nd in 2016 to 46th in 2021, reaching its lowest ranking of 54th among 167 countries in 2020. India rates well for the quality of its electoral processes, government institutions and political pluralism, but has seen sharp declines in its ratings for political culture in the face of an increasingly polarised discourse, and for civil liberties, with reports of excessive force by security forces against protestors. Protests by Muslims and other minorities have increased, most notably in Kashmir, India’s only Muslim-majority state, following the revoking of its autonomous status, and in Assam, where 1.9 million Muslims were stripped of their rights through 2019 amendments to India’s national citizenship law. The Bharatiya Janata Party of Prime Minister Modi came to power on the back of pledges to tackle corruption in India’s political system, but has faced major corruption scandals of its own. India ranks 85th of 180 on the Corruption Perceptions Index. Indian democracy is supported by an independent judiciary and a vibrant civil society, but non-governmental organisations face growing government restrictions on their ability to register, operate and raise funds.

3.7 India is seeking to take on a more prominent role in regional and global affairs. In recent years, in the face of growing strategic rivalry with China, it has discontinued its traditional non-aligned stance in favour of strengthening ties with the US and other Western allies, and also with Russia and regional powers such as the United Arab Emirates and Saudi Arabia. It is a member of the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue (‘Quad’), with the US, Australia and Japan, created in response to China’s increased projection of power in the Asia-Pacific region. It plays an increasingly vocal role in multilateral forums such as the G20, of which it will hold the presidency in 2023. For all these reasons, India is a key strategic partner for the UK, given the ‘Indo-Pacific tilt’ in UK foreign policy signalled in the 2021 Integrated review.

3.8 At the regional level, India has border disputes with both China and Pakistan, and faces growing threats from Islamic terrorism in neighbouring countries. Water is a key strategic issue in the South Asian region. The Ganges-Brahmaputra-Megna basin, where three major rivers converge, spans India, China, Bangladesh, Bhutan, Myanmar and Nepal, and is home to almost 10% of the world’s population. Competing demands for hydro-electric power, irrigation and drinking water have the potential to become a source of conflict, as climate change increases water scarcity.

3.9 India is also an emerging donor, supporting humanitarian response in neighbouring countries such as Nepal and Bhutan, and funding aid projects in Africa. It also provides low-interest or ‘soft’ loans, technical assistance and humanitarian relief. India is not a member of the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) Development Assistance Committee and does not contribute to global aid statistics. Indian aid is spent by a range of government departments and agencies, and estimates of the total vary widely. In the 2021-22 budget, nearly £2 billion was allocated for foreign aid grants. The Indian Ministry of External Affairs reports that India has extended soft loans totalling around £25 billion to developing countries since it began its aid programme.

The UK’s evolving partnership with India

3.10 A decade ago, India was the largest recipient of UK bilateral aid, with annual funding peaking at £421 million in 2010. Aid was concentrated in India’s poorest states and focused on relieving poverty through programming to improve basic services like health and education and to promote livelihood opportunities among poor communities. However, as India began to assume a more prominent global role, UK aid to India became increasingly controversial, criticised by sections of the British media and political establishment. A 2011 International Development Committee inquiry found that there was a case for continued support to India in the short term, concentrated in the poorest states, but concluded that the UK should work towards a fundamentally different relationship by 2015, based around the sharing of knowledge. A phasing out of financial aid by 2015 was duly adopted as UK government policy in 2012, by agreement between the two countries.

3.11 The transition process was reviewed by ICAI in 2015. We found that it was marred by miscommunication and a lack of clarity about the new relationship, reflecting uncertainty within the Department for International Development (DFID) at the time about its role in middle-income countries. Furthermore, the UK had not done enough during the transition to preserve its strong relationships with Indian stakeholders, across government and civil society. We found that significant aid flows continued after the transition. While financial aid to the Indian government was, indeed, phased out as planned, the reduction was partly offset by increases in development investment, and programming designed to promote mutual prosperity. We recommended greater transparency to UK taxpayers through such transition processes to avoid misunderstanding.

3.12 Since its departure from the European Union, the UK has given more weight to its bilateral relationship with India. It was UK policy to build a more ambitious strategic partnership, in order to strengthen bilateral economic ties and leverage opportunities arising from India’s growing regional and global roles. A number of joint statements between the two governments over the 2016-18 period spoke of the need to increase trade and investment for mutual prosperity, to link up people and institutions, to mobilise finance for India’s infrastructure development and ‘smart’ cities, and to address climate change. In September 2021 these objectives were formalised into a ‘comprehensive strategic partnership’, with the objectives set out in a 2030 Roadmap for India-UK future relations (hereafter, ‘Roadmap’), signed by the two prime ministers, covering both economic and security matters, and designed to deliver benefits for both countries. Box 3 summarises the main objectives of the Roadmap.

Box 3: The 2030 Roadmap for India-UK relations

The 2030 Roadmap for India-UK future relations, agreed by the two governments on 4 May 2021, set out the objectives of the bilateral partnership over the next decade. Here are some of the main objectives, organised under five chapters:

- Connecting our countries and our people

- Enhance political ties, including through biennial India-UK summits, improved cooperation in the UN and other multilateral forums, and regular exchanges between parliaments, judicial and executive institutions.

- Increase mobility of students and professionals.

- Expand cooperation between universities on research, science and innovation.

- Technology partnerships in areas such as artificial intelligence.

- Trade and prosperity

- Conclude a comprehensive free trade agreement and eliminate barriers to trade.

- Share experience on regulatory reform, tax administration and trade facilitation.

- Increase cooperation in services sectors, in areas such as IT, healthcare, financial services, transport and tourism.

- Increase trade in financial services and promote infrastructure financing in India.

- Promote smart and sustainable urbanisation.

- Defence and security

- Tackle cybercrime and terrorist threats.

- Defence and maritime cooperation.

- Climate

- Reduce carbon emissions and build resilience to climate change.

- Mobilise investment in renewable energy, clean transport, industrial decarbonisation and green business.

- Support small island developing states with disaster-resilient infrastructure.

- Promote nature and biodiversity, including through innovative solutions to tackling plastic and marine pollution.

- Improve waste management and the circular economy.

- Health

- Promote research and innovation on global health threats.

- Strengthen COVID-19 and other pandemic preparedness.

Take global leadership on tackling anti-microbial resistance and non-communicable diseases.

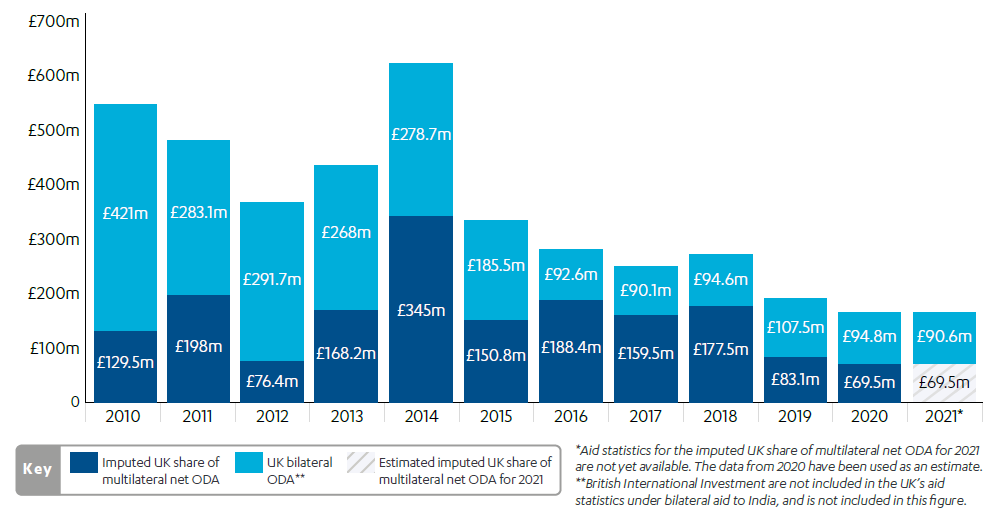

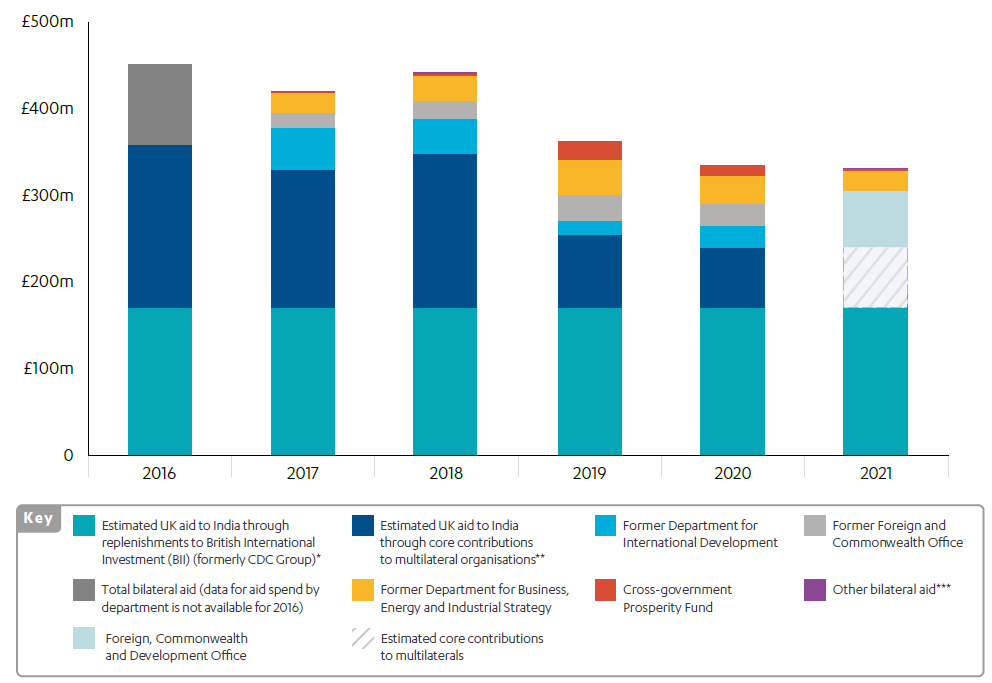

The new profile of UK aid to India

- The official aid statistics show a steady decline in UK aid to India, through both bilateral and multilateral channels (see Figure 4). This is consistent with the UK government’s phasing out of financial aid to the government of India and of traditional aid projects. Bilateral aid fell from £279 million in 2014 (when India was still the second-largest recipient of UK bilateral aid) to £186 million in 2015 (making it 9th), and £95 million in 2020 (16th). However, India was protected during recent rounds of UK aid budget reductions, relative to many other countries. While bilateral aid to India fell to £91 million in 2021, India rose to 11th place, ahead of Bangladesh, Kenya and the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

Figure 4: UK bilateral and multilateral official development assistance (ODA) to India

Source: Additional tables: Statistics on international development: final UK aid spend 2021, Table A4b and Table A10, various years, Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office: Aid spend 2021; Aid spend 2020; Aid spend 2019; Aid spend 2018; Aid spend 2017.

3.14 The UK’s imputed share of multilateral aid to India has also declined. Historically, India was the largest borrower from the International Development Association (IDA), the part of the World Bank Group that provides concessional finance to the world’s poorest countries. From 2014, it began to graduate from IDA, and it is now the largest borrower from the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development, which lends on more commercial terms to middle-income countries. India is now repaying its approximate £2.5 billion in IDA credits at an accelerated pace, freeing up resources for other developing countries. India has also become a donor to IDA. As a consequence, while India is still borrowing from the World Bank, it is repaying more than it receives. This appears as a negative figure in the aid statistics, and accounts for India’s declining multilateral aid receipts. India also receives funding through other multilateral channels, including the Asian Development Bank, UN agencies and international climate funds.

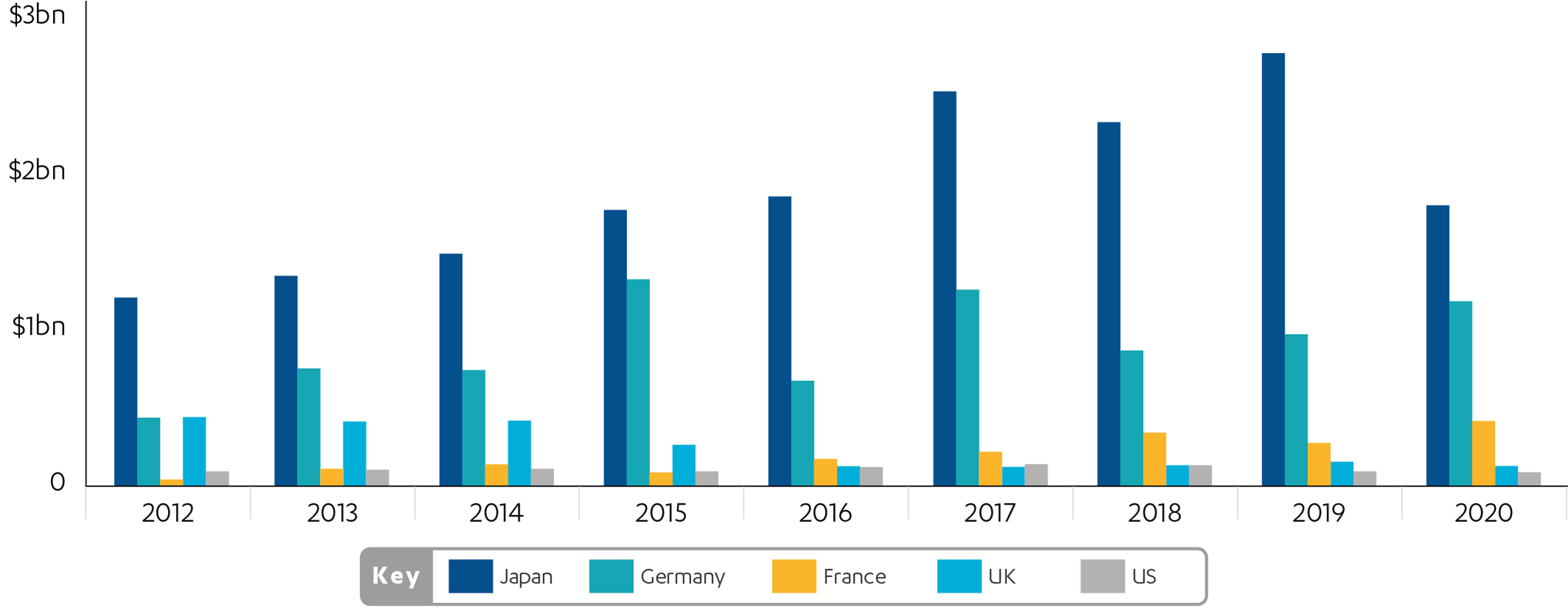

3.15 According to OECD statistics, the UK is the fourth-largest bilateral donor to India, well behind Japan, Germany and France (see Figure 5). For each of these donors, a substantial share of their assistance is in the form of loans and equity investments through their respective development finance institutions (see Box 4 and Box 5).

Figure 5: Gross disbursement of official development assistance to India by major bilateral donors

Source: Development finance data, Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development Creditor Reporting System (CRS). OECD CRS data are only available between 2012 and 2020.

Box 4: Development finance institutions in India

Development finance institutions (DFIs) are specialised institutions set up to provide concessional finance and other support for development in low- and middle-income countries. Bilateral DFIs, like British International Investment (BII), are owned by their national governments, making investments in accordance with objectives and policies set by those governments. DFIs are expected to balance development impact and financial sustainability, while promoting high levels of public transparency and environmental, social and governance standards.

In India major bilateral DFIs include the UK’s BII, France’s Proparco, the Dutch Entrepreneurial Development Bank (FMO), the German Investment and Development Corporation (DEG), and the US International Development Finance Corporation (DFC). BII is the largest bilateral DFI in India and invests a larger proportion of its global portfolio in India than other bilateral DFIs, at 28%.

Over our review period, BII (formerly CDC Group) investments in India have been guided by three different investment strategies:

- CDC’s 2012-16 Investment policy: This strategy announced a shift of focus away from middle-income countries and towards the poorest countries and the most challenging sectors. This strategy introduced an approach to selecting investments on the basis of their potential development impact, with job creation as the primary objective.

- CDC’s 2017-21 Investing to transform lives: This strategic framework deepened CDC’s approach to development impact, to include addressing market failures and achieving a wider range of objectives under the Sustainable Development Goals and the Paris climate agreement, including women’s economic empowerment and low-carbon development. CDC also introduced its ‘catalyst’ portfolio to facilitate higher-risk investments with greater potential for development impact. Under this strategy, CDC decided to treat Indian states as equivalent to other countries in its portfolio, prioritising the poorest states and populations, as well as helping Indian companies expand their operations in the poorest states. The strategy also posits that some investments (such as in solar panels) outside the poorest states could also promote inclusive growth. In this period, CDC strengthened its presence in India through offices in Bengaluru and Mumbai.

BII’s 2022-26 strategy on Productive, sustainable and inclusive investment: This strategy outlines three strategic objectives: (i) invest in productive development that delivers jobs and growth, with an emphasis on building new markets by demonstrating the potential for successful investment; (ii) promote sustainable development by tackling climate change adaptation and mitigation, as well as natural resource depletion; and (iii) promote inclusive development by tackling gender inequality and other forms of exclusion, and prioritise job creation for marginalised groups. Under this strategy, BII has introduced ‘country perspectives’, taking account of national development plans and FCDO country plans.

Box 5: Different aid instruments used by the UK and other bilateral donors

The UK uses a number of different instruments for channelling and delivering aid to India. These include:

- Technical assistance: The provision of resources, aimed at the transfer of technical and managerial skills or technology, for the purpose of building capacity or supporting the implementation of specific investments.

- Research funding: Aid spent on research, mostly in science and technology, resulting in new products, processes and understanding, that promotes the economic development and welfare of developing countries. Research funding is reported in aid statistics as a form of technical assistance.

- Development investment: Aid-funded investments (usually loans or equity investments) that are intended to generate development impact along with a modest financial return.

In addition to these aid instruments, donors such as Japan and Germany also provide financial aid to India, which explains their larger aid flows in comparison to the UK. This includes:

- Concessional loans: Low-interest (below market rates), long-term ‘soft’ loans extended by donor governments directly to developing country governments.

- Grant finance: Provision of funds to the governments of developing countries without the obligation of repayment.

3.16 The fall in bilateral grants from the UK has been partially offset by a rise in development investment. The UK has two separate development investment portfolios in India. The larger one is managed by the UK’s development finance institution, British International Investment (BII, formerly CDC Group). While the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO) is BII’s sole shareholder, it operates at arm’s length, with individual investment decisions taken independently of FCDO. BII is the world’s oldest development finance institution, established in 1948 as the Colonial Development Corporation with a mission “to do good without losing money”. It currently has a global portfolio of over £8 billion, invested in over a thousand businesses across Asia and Africa. It has been active in India for over 30 years, with a portfolio of 389 investments valued at £2.3 billion in 2021 – by far its largest country portfolio, at 28% of the total. The next-largest portfolio is Nigeria, at 7%. Among peer DFIs, this is the highest concentration of investments in India. It includes loans and equity investments provided directly to Indian firms, as well as investments through Indian financial institutions as intermediaries. It seeks to promote productive, sustainable and inclusive development in sectors such as agribusiness, manufacturing, healthcare, infrastructure and financial services. In particular, BII’s India ‘country perspective’ prioritises investments in climate action, including renewable energy, electric vehicles, the circular economy and sustainable agriculture.

3.17 In recent years BII has scaled up its global portfolio, receiving £3.7 billion in new capital from the former DFID and FCDO between 2016 and 2021. One of the objectives of the scale-up was to deliver greater development impact in low-income and fragile states. Its financial return targets were reduced, in recognition that this objective would require it to operate in riskier markets. 28% of BII’s portfolio by value has been invested in India which, as a large and relatively mature market, has greater capacity to absorb development investment at scale than most aid-eligible countries. These investments do not appear in the UK’s aid statistics under bilateral aid to India. BII’s average financial return from its Indian investments was higher than the average financial return from the global portfolio throughout the review period, which suggests that the India portfolio helps to balance BII’s riskier investments in other markets.

3.18 FCDO also directly manages a development investment portfolio in India (‘FCDO DevCap’). Its purpose is to pioneer investments in sectors and regions that are neglected by private investors to scale up access to markets and services for excluded and disadvantaged groups. Since 2013 DFID/FCDO has committed £336 million to DevCap, of which £228 million has so far been invested. These investments have generated a return of £100 million since 2013. DevCap invests in sectors such as renewable energy, infrastructure, financial services, agriculture and healthcare. The investments are directed through 11 intermediary funds, of which two are lending institutions and the other nine are equity funds. In recent years the portfolio has also included ‘trilateral’ funds, established with the objective of supporting Indian innovators to scale up their activities in other developing countries.

3.19 FCDO’s approach to development investment is distinct from BII’s in several ways. Since 2014, its focus has been entirely on equity. Unlike BII, it works closely with the Indian government, and has established a number of joint investment funds with government-led financial institutions. The majority of FCDO investments are also accompanied by technical assistance to support institutional, policy and regulatory reforms, de-risk investments and build markets in targeted sectors. FCDO has spent £41 million in linked technical assistance projects since 2013.

3.20 When these additional figures are taken into account, we estimate that the UK disbursed around £2.3 billion in aid to India between 2016 and 2021 (see Figure 6 for a breakdown by year and spending channel). This figure includes £441 million in bilateral grants in the form of technical assistance and research, and £129 million in bilateral development investments via FCDO which generate a return. The majority has been spent by FCDO (and its predecessor departments) and the Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy (now the Department for Science, Innovation and Technology), which manages most of the research funding. The figures also include an estimated £749 million of aid to India between 2016 and 2021 through an imputed share of core contributions to multilateral organisations. In addition, the UK contributed an estimated £1 billion in India via BII. Returns from these investments are reinvested by BII to help it meet its global financial returns target.

Figure 6: Total estimated UK bilateral and multilateral aid to India by channel, including British International Investment

Source: Additional tables: Statistics on international development final UK aid spend 2021, Table A4f and Table A10, Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office, 2022, link.

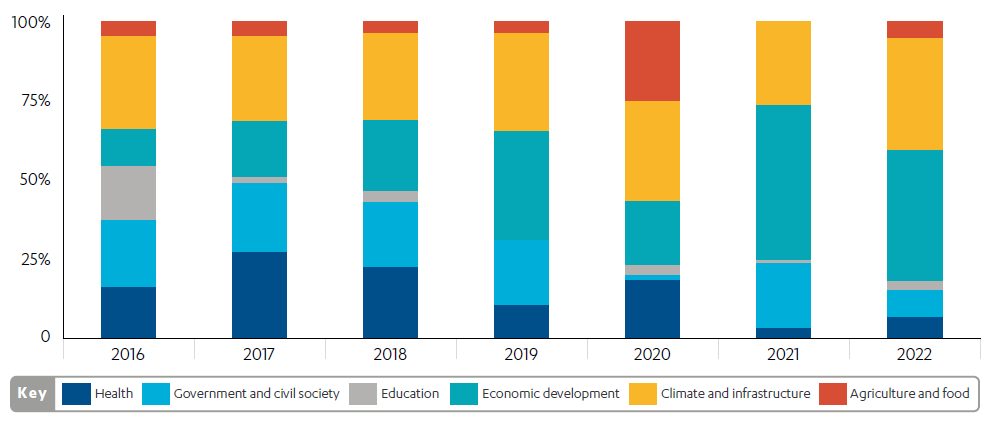

3.21 The sectoral composition of UK aid has also evolved. At the beginning of the review period there was a strong focus on agricultural and rural livelihoods, support to government and civil society, and basic services. Economic development is now the largest programming area, with climate change a consistent priority through the review period (see Figure 7).

Figure 7: Sector composition of UK bilateral programmes and investments

Source: International Aid Transparency Initiative data on programmes and investments made by FCDO by sector since 2016 to reflect different sector tags attached to India programmes. As there are often many sectors applied to programmes under this system of categorisation, sectors were aggregated into the six broad categories used above. The specific dataset used for FCDO India has since been removed from the IATI website, so a general link to FCDO IATI data has been provided in place.

3.22 The UK has a Country Plan for India, setting out shared objectives for the UK government as a whole. It aligns with the shared objectives set out in the Roadmap and also outlines UK-specific objectives and outcomes. This is not a public document and it covers areas of activities that are not linked to the aid programme. The main goals of the India Country Plan that are supported by aid programming are:

- mutual prosperity through an enhanced trade relationship

- acceleration of India’s clean growth transition

- an innovative UK-India health partnership

- championing of open societies and democratic standards

- leveraging of UK education, research, enterprise and innovation expertise.

3.23 Relevant outcomes in the strategy include: economic, trade and regulatory reforms that enable market-led inclusive growth and poverty reduction; financial sector reform and liberalisation; reform of India’s power sector and greater uptake of renewable energy; increased green finance; increased government capacity to deliver smart urbanisation; more evidence-based policymaking by India’s federal and state governments; and an open, democratic India that grows inclusively and respects minority rights and civic freedoms. The Country Plan emphasises the use of development investment to support sustainable, pro-poor private sector organisations in areas such as clean energy, waste management, health, education and skills development. On global development issues, it includes objectives around working in partnership with India to drive global climate action, and looking for opportunities to collaborate within the UN and multilateral forums. There are no specific objectives relating to research partnerships which are mainly funded centrally.

3.24 The UK government’s representation in India is its largest anywhere in the world, with 830 staff in the UK and in 11 locations across the country, managing both aid and other expenditure. This reflects India’s scale and diversity, and the range of UK interests. The size of this network enables the UK to maintain relationships with Indian stakeholders at both central and state levels. Just under a third of the salaries of UK government officials in India are counted as aid (see Box 6).

Box 6: Which UK government salaries in India are charged to the aid budget?

In 2021 the UK government charged around a 34% share of the salary and overhead costs of UK staff in India to the aid budget, for a total of £13 million (known as ‘aid-related frontline diplomatic activity’). This was a reduction on the £15.4 million charged in 2020, due to a reduced aid budget. In 2022 the proportion of aid-related frontline diplomatic activity charged to the aid budget was 30%.

International official development assistance (ODA) reporting rules permit donor countries to report a share of the salary-related costs of diplomatic staff working on their aid programme as ODA, based on an estimate of the share of their time spent on aid-related duties. FCDO generates its estimate using the following method: Of approximately 820 UK government staff working on India, 91 staff work in FCDO’s main ‘aid-spending teams’, who manage the delivery of ODA but also have other duties. For each goal in the FCDO country plan, an estimate is made of the proportion of activities undertaken in support of the goal that are ODA-eligible. The proportion of time that the relevant FCDO teams spend on that goal is also estimated. For example, FCDO’s work on ‘climate and investment partnerships’ is assessed as 99% ODA-eligible and takes up 47% of the time of FCDO aid-spending teams. Work on ‘defence and security’ is only 10% ODA-eligible and takes up 7% of the time of FCDO aid-spending teams. When the figures are totalled across the five goals, it yields an estimate of 73% of the time of FCDO aid-spending teams as spent on aid-related duties.

A simpler method is used for staff from other government departments as follows: Officials from the Department of International Trade are assumed to spend 5% of their time on the aid programme, and officials from other departments are assumed to spend 30%.

| Goal in the country plan | What percentage of activities under this goal are ODA-eligible? | What percentage of the time of FCDO spending teams goes towards this goal? | Weighted ODA effort | |

| 1 | Trade, investment and prosperity | 50% | 28% | 14% |

| 2 | Defence and security | 10% | 7% | 1% |

| 3 | Climate and investment partnerships | 99% | 47% | 46% |

| 4 | Science, technology and health | 75% | 14% | 10% |

| 5 | Connecting people | 50% | 5% | 3% |

| Total for FCDO aid spending teams- | 73% | |||

4. Findings

4.1 This chapter of the report sets out the substantive findings of our review, under the three review criteria of relevance, coherence and effectiveness.

Relevance: How relevant is the UK’s evolving model for development cooperation with India?

4.2 In this section we assess the relevance of the UK’s new model for development cooperation with India in light of India’s evolving needs, the objectives of the two governments, and the UK’s comparative advantage as a development partner.

The new approach to aid reflects Indian government preferences, UK strategic interests and the evolving bilateral relationship

4.3 The transition of UK aid away from financial support to government and from the direct financing of poverty reduction was a legitimate response to the Indian government’s evolving needs and preferences. India’s economic growth over the past two decades has translated into rapid growth in domestic fiscal revenues. With its large economy, India is able to borrow from international financial markets and its maturing domestic financial sector. Given India’s access to development finance at scale, UK aid is no longer significant in financial terms. The development case for any further aid rests on it playing a catalytic role, to influence Indian government policies, or to mobilise private finance into key areas for inclusive economic development, such as renewable energy. The International Development Committee made a similar case back in 2011.

4.6 The transition also reflects the Indian government’s longstanding preference for a partnership of equals with the UK, based on mutual interests, rather than a traditional donor-recipient relationship. In 2003 it announced that it would no longer accept tied or conditional aid – an apparent reference to donors attempting to influence Indian government policy. It also requested that bilateral donors with smaller aid programmes direct their support through multilateral institutions or non-governmental organisations (NGOs). It declined international humanitarian assistance after a number of natural disasters, including the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami. India has since become a net donor, giving more aid than it receives. The UK government’s 2012 announcement of a transition away from traditional aid was based on an agreement between the two countries, and this is reiterated in subsequent joint statements and agreements.

4.7 The India portfolio also reflects evolving UK government policy on how to use aid to support bilateral partnerships with middle-income countries such as India. The March 2021 Integrated review of security, defence, development and foreign policy stated that the UK would focus its aid on “those areas which are important to a globally-focused UK”, with increasing efforts in the Indo-Pacific region (‘the Indo-Pacific tilt’). It stated that the UK would “more effectively combine our diplomacy and aid with trade.” On India it stated that, over the next ten years, the UK would “seek transformation in our cooperation across the full range of shared interests”, including cultural ties, trade, investment, research collaboration, and global challenges such as climate change, clean energy and global health. It stated that: “Where countries can finance their development, we will move gradually from offering grants to providing UK expertise and returnable capital [i.e. loans and equity investments] to address regional challenges in our mutual interest. This will include support to high-quality infrastructure.”

4.8 The 2022 International development strategy similarly stresses that aid is part of a coherent UK foreign policy, alongside “diplomatic influence, trade policy, defence, intelligence [and] business partnerships”. Its first priority is to “deliver honest and reliable investment”, based on the UK’s financial expertise (including in climate finance) and the strengths of the City of London as a global financial centre. It cites India (together with Indonesia) as an example of a comprehensive strategic partnership that will help the UK achieve global impact. It notes the importance of collaboration in science and technology to tackle global development challenges, and of joint working in global forums to advance climate and biodiversity goals.

“We will help countries get the investment they need to grow secure, open, thriving economies. Countries need to avoid loading their balance sheets with unsustainable debt, and mortgaging their future economies against bad loans. We can help, by putting our national economic power at the centre of our development approach: capital markets, investment and growth expertise, independent trade policies.”

UK International development strategy, p. 8.

4.7 The India portfolio has been developed to fit this new paradigm. Aid is being used to support a range of shared objectives agreed under the Roadmap, with the main focus areas being mobilising climate finance for investing in clean energy and sustainable infrastructure, research partnerships on global development challenges and, on a smaller scale, supporting India’s emerging global and regional roles.

4.8 While the aid portfolio is broadly relevant to the Roadmap, it does not map neatly onto Roadmap objectives. Not all the objectives are suitable for aid programming, and some which could be supported by aid are not, especially since the recent budget reductions. However, Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO) officials note that this is an evolving picture, as the Roadmap is a 2021 document setting out joint objectives through to 2030. In the period since then, the development of programming in support of the Roadmap has been disrupted by the COVID-19 pandemic, the merger of the Department for International Development (DFID) and the Foreign and Commonwealth Office (FCO), and successive UK aid budget reductions, all of which have reduced FCDO’s scope to take on new initiatives.

4.9 Indian government officials noted that the UK was one of the few donors able to maintain a network of relationships across Indian government departments and agencies in its chosen thematic areas, which helps to increase the relevance and responsiveness of UK aid. The shift from grants to development investments elicited mixed views. Some officials were of the view that loans and investments were more appropriate to a partnership of equals than ‘free’ grant funding. Others noted that grants remained a better instrument for supporting reforms and testing out innovations, which could then be scaled up with development investment. Indian government officials also fed back that the UK had moved away from several sectors where there is still demand for its support, such as vocational training and urban development. The UK’s exit from those areas had occurred as a result of UK aid budget reductions, and had not involved consultation with the Indian government. Overall, Indian stakeholders noted that, while India no longer considers itself a traditional aid recipient, it remains eager to learn from the experiences of advanced economies, including the UK.

UK aid to India lacks a compelling development rationale

4.10 The UK’s overarching objective is a stronger bilateral relationship with India, and aid is being used in a variety of ways to support that partnership. This results in a fragmented portfolio without a compelling development rationale.

4.11 The UK India Country Plan has 58 outcomes. Of these, we assess that at least 16 have been supported by aid programming over the review period:

- economic reform

- trade and regulatory reform

- financial services

- infrastructure

- evidence-based policymaking

- democracy and institutional partnerships

- UK-India Global Partnership on Development

- global development cooperation

- clean energy

- green finance

- adaptation and resilience

- urbanisation and clean transport

- nature and biodiversity

- health and epidemic preparedness

- crisis preparedness

- finance, enterprise and entrepreneurship.

4.12 FCDO documents do not set out an explicit rationale for which objectives should be supported through aid funding, or what level of investment is appropriate in each area. This results in activities that are not well integrated thematically, and that often lack the scale required for meaningful impact. Individually, each activity is relevant and meets the eligibility criteria for official development assistance (ODA). Collectively, however, it is not clear that they add up to a strategic portfolio of development cooperation. This is particularly the case since recent aid budget reductions have led to many of the activities being scaled back. A number of stakeholders, both within and outside the UK government, expressed the view that UK aid to India has become ‘transactional’, rather than outcome-focused. To achieve strategic outcomes with relatively small budgets would require a concentration of resources (both finance and development diplomacy) into a few areas with the greatest potential for catalytic effect.

“The UK talks the big talk, but then plays a marginal game.”

“When you are small, you need to decide where you can have the greatest probability of strategic impact.”

Indian think tank representatives.

4.13 We note that stronger bilateral ties with India, while an important UK foreign policy objective, should not be the primary purpose of the aid programme. The internationally agreed definition of ODA specifies that it must have “the promotion of the economic development and welfare of developing countries” as its main objective. The International Development Act 2002, which provides the spending authority for most UK aid, further requires that spending departments must be “satisfied that the provision of the assistance is likely to contribute to a reduction in poverty”. To meet both these requirements, UK aid must be focused primarily on promoting poverty reduction and economic development, either in India or in other developing countries.

4.14 We accept that, in the Indian context, there was a clear case for moving away from direct funding of individual development projects towards working at the policy and institutional level. Relatively small amounts of UK aid can potentially have much larger impact by influencing far larger Indian government expenditure and private sector investment flows. However, upstream interventions of this kind must still demonstrate a clear and convincing link to inclusive growth and poverty reduction. In fact, as aid programming moves upstream, our view is that there is a greater onus on spending departments to articulate a clear rationale for how aid will lead to poverty reduction. In the India context, this means not just contributing to India’s already high economic growth but identifying bottlenecks that prevent that growth from being inclusive in nature and identifying how to use UK aid in catalytic ways to address them. That rationale has not been clearly set out for the India portfolio. While some of the analytical foundations were set out in diagnostic work done by DFID in 2018 and 2019, such analysis dates quickly, and it is not clear that it has, in fact, influenced the composition of the current portfolio.