UK aid to India

Rationale, purpose and scope

UK aid to India has undergone a major transformation since 2015, and lessons from these changes will be relevant for UK aid in other countries. In the decade before 2015, India was one of the largest recipients of UK aid. The UK’s portfolio of direct financial aid (grants provided directly from donor governments to partner governments in developing countries) focused on supporting the Indian government’s delivery of services, such as health and education, in the country’s poorest states. Since 2010, there has been a trend of decreased UK aid to India, after a long-standing debate in the UK about the extent to which limited aid resources should be disbursed in middle-income countries as opposed to lower-income countries, and after statements from the Indian government that UK aid was no longer needed.

In 2011, the International Development Committee (IDC) of the UK Parliament published an inquiry entitled The future of DFID’s programme in India. The inquiry concluded that UK aid could only have a marginal impact on India’s development because it made up only a tiny proportion of India’s gross domestic product. The IDC therefore called for the UK’s aid relationship with India to change. In response to the inquiry, the former Department for International Development (DFID) noted that it had stopped providing direct financial aid to the Indian government. However, the UK continued to provide other forms of bilateral aid to India through DFID, cross-government funds and other government departments. This aid has been in the form of technical assistance and research funding, as well as ‘development capital’ investment in the private sector. The UK has also continued to provide multilateral aid through core contributions to multilateral organisations. The UK government has increasingly used a ‘mutual prosperity’ approach, whereby aid explicitly benefits both countries, to justify continuing aid to India.

The UK government has sought to pursue an integrated approach to aid, trade, diplomacy and security in recent years. In 2020, the former Foreign and Commonwealth Office (FCO) and the former DFID merged to form the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO). The UK government’s ambition was set out in the Integrated review of security, defence, development and foreign policy, published in March 2021, which stated that the UK government “will more effectively combine our diplomacy and aid with trade” and “tackle regional challenges in our mutual interests”. The Integrated review also set out the UK’s intention of making an ‘Indo-Pacific tilt’, describing the UK’s ambition to forge deeper economic and political ties with the region. Published in May 2022, the new UK Strategy for international development emphasised the need for the UK to use all its capabilities, including diplomatic influence, trade policy, defence, intelligence, business and investment partnerships and development expertise to achieve development objectives.

The purpose of this review is to examine how the UK’s aid spending in India has developed since DFID ceased direct financial aid to the Indian government in 2015. It includes UK aid spending during the COVID-19 pandemic. It will assess the relevance of UK aid to India’s needs and the shared interests of the two countries. It will also look at the extent to which different funding streams have been coherent. Finally, the review will assess the effectiveness of UK aid to India in achieving the UK’s strategic objectives over the review period. The review will build on previous scrutiny of UK aid spending in India, including the 2011 IDC inquiry and the 2016 ICAI review of DFID’s approach to managing exit and transition, in which UK bilateral aid to India was a case study.

The review will cover all the UK’s official development assistance (ODA) to India. This includes ODA spent through FCDO, the former DFID, other government bodies including the Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy, the cross-government Prosperity Fund (now part of FCDO), and UK aid channelled through multilateral organisations. It will cover UK development capital investment in private sector businesses in India, which is provided through two channels: ODA invested by British International Investment (BII, formerly CDC), the UK’s development finance institution, and FCDO’s own development capital portfolio, which is unique in that it is managed directly by FCDO in India separately from BII’s investments in the country. The review will assess the coherence of the UK’s approach in India across all ODA spend, as well as its associated diplomatic activity. It will not cover the effectiveness of this associated diplomatic activity.

Background

India is one of the fastest growing major economies and is projected to become the world’s fourth-largest economy by 2030. However, despite its economic success, India is constrained in reaching its full global economic and political potential by significant challenges, including continuing high poverty rates (with 150 million people estimated to be living below the international poverty line), skills shortages, unplanned urbanisation, a huge infrastructure deficit, pollution and the impacts of climate change.

The UK government has set out an agenda for strengthening its strategic partnership with India, aimed at promoting the security and prosperity of both countries, including through increasing trade and investment opportunities, cooperation on defence and security, collaboration around research and innovation, and efforts to address climate change. Within this broader strategic partnership, assistance that is likely to contribute to a reduction in poverty should remain the focus of the UK official development assistance spent in India, in accordance with the International Development Act.

The Department for International Development (DFID) stopped providing direct financial aid to the Indian government in 2015. The UK’s remaining bilateral aid portfolio in India, managed through DFID and subsequently the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO), as well as other departments such as the Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy, shifted to other aid modalities such as technical assistance and development capital to private sector companies. UK aid to India is now largely focused on climate, infrastructure and economic development, rather than the provision of basic services such as health and education to the poorest states in India.

As noted above, FCDO in India is unique in that it manages its own portfolio of development capital investments in private companies. This is separate from the India investment portfolio held by British International Investment (BII, formerly CDC). India represents BII’s largest portfolio, making up 25% of its active investments at the end of 2020. The UK also provides aid to India through core contributions to multilateral organisations including the World Bank and the Asian Development Bank.

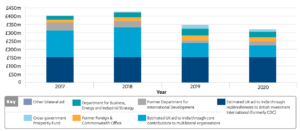

Between 2016 and 2020, we estimate that the UK disbursed around £1.9 billion of aid to India. This figure includes £480 million in bilateral aid, including technical assistance, development capital and research. It also includes an estimated £679 million of aid to India through an imputed share of core contributions to multilateral organisations, largely through the World Bank and the multilateral Climate Investment Funds, which focus on clean technology. In addition, the UK contributed an estimated £756 million in India via replenishments to BII.

Figure 1: Estimated amount of UK bilateral and multilateral aid to India over the review period (where comparable data are available)

Source: FCDO’s Statistics for International Development collection, link.

Note: We have estimated UK aid to India through replenishments to BII using FCDO’s budget data (link) and assuming that 25% of this replenishment capital is being invested by BII in India, based on data available on the BII website (link).

Review questions

The review is built around the evaluation criteria of relevance, coherence and effectiveness. It will address the following questions and sub-questions:

Table 1: Our review questions

| Review criteria and questions | Sub-questions |

|---|---|

| Relevance: How relevant is the UK’s evolving model for development cooperation with India? | • How well has the UK understood and adapted its approach to development cooperation to the evolving economic, social and political context in India? • To what extent is UK aid to India governed by a clear set of objectives supporting the shared interests of the two countries? • To what extent is UK aid to India guided by a clear understanding of the UK’s comparative advantage? |

| Coherence: How internally and externally coherent has the UK’s official development assistance and associated diplomatic activity been in India? | • How coordinated are the instruments and channels through which the UK provides aid to India? • How well has the UK built partnerships with, and influenced, other bilateral donors, multilateral agencies, national civil society organisations and other actors? • How well do the UK’s diplomatic activities support its development objectives? |

| Effectiveness: How effective has the UK aid portfolio been in achieving its strategic objectives in India? | • How effectively has UK technical assistance and research funding helped to strengthen Indian institutions and capacities? • How effective have UK capital investments been in promoting inclusive, sustainable and green growth through the portfolio? • How well do UK multilateral aid and partnerships contribute to India’s development? |

Methodology

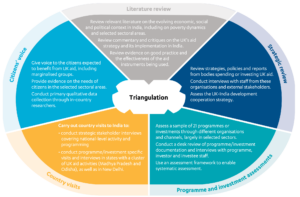

The methodology for the review will involve five components, allowing a high level of triangulation of evidence to provide robust answers to our review questions. The review will include evidence collection at a strategic level and across the UK aid portfolio in India, as well as more detailed assessment of a sample of programmes and investments. The methodology includes primary evidence collection, review of documentation from the bodies spending or investing UK aid, and a literature review. The interlocking components of the methodology will be sequenced to allow the literature review and strategic review to help generate key lines of enquiry to pursue through the other elements of the review.

Figure 2: Overview of methodology

Component 1 – Strategic review: We will examine strategies, policies and plans and interview relevant staff from UK government bodies, including British International Investment, that are spending or investing UK aid in India. We will also interview external stakeholders, including from Indian institutions, civil society, other development partner organisations and academia. Through these activities, we will assess: the UK government’s understanding of the Indian context and of the UK’s comparative advantage as a donor; the clarity of the objectives of the organisations delivering UK aid; how coherently the UK’s development cooperation with India has been implemented (including through using diplomatic activities to support development objectives); and how well the UK has built partnerships with, and influenced, others.

Component 2 – Literature review: To assess the relevance of the UK’s approach to development cooperation with India, we will review literature on the changing economic, social and political context, particularly on the sectoral areas that are the focus of UK aid. We will also review commentary and critiques on the UK’s approach to aid to India and its implementation. To help us to consider the alignment of UK aid with good practice, and thereby inform our assessments of the effectiveness of UK aid to India, we will review literature on the effectiveness of the major aid instruments being used (development capital, technical assistance and research funding), of aid to the sectoral areas that UK aid to India focuses on (climate, infrastructure and economic development), and peer approaches in India (World Bank, Asian Development and other bilateral donors). The literature review will offer a concise summary of the key issues and conclusions emerging from both academic and ‘grey’ literature, commenting where appropriate on the quality of evidence underlying the main conclusions. The review will make full use of existing literature reviews and summaries where available. It will be published alongside the report.

Component 3 – Programme and investment assessments: We will assess UK aid spending and investment in India using a sample of 21 programmes and investments through different organisations, channels and instruments. We will conduct a desk review of each programme or investment, including business cases or investment cases, monitoring documentation and any evaluations undertaken. We will also conduct interviews with programme, investor and investee staff. We will assess the coherence of the objectives of each programme or investment with overall UK objectives and its comparative advantage as a donor. We will look at how well the programme or investment is coordinated with other UK aid spending and with other non-official development assistance spending. Finally, we will examine the effectiveness of the programme or investment in contributing to strengthening Indian institutions and capacities and promoting sustainable and inclusive development. We will develop a framework for the systematic assessment of these programmes and investments to identify recurrent patterns, including strengths and weaknesses.

Component 4 – Country visits: Visits to India will allow us to engage with a wide variety of stakeholders, visit programme and investment locations, and engage with citizens intended to benefit from UK aid investments. We will visit New Delhi, primarily to meet with strategic stakeholders. We will also travel to Madhya Pradesh and Odisha, where there are clusters of UK-funded programmes and investments. Concentrating our in-country work in these states will maximise our opportunities to triangulate our findings on the ground.

Component 5 – Citizens’ voice: We will conduct primary qualitative data collection with citizens, with a focus on people expected to benefit from UK programmes and investments, including marginalised groups. We will carry out this research in several Indian states (including Madhya Pradesh and Odisha). This component will provide an opportunity for those expected to benefit from UK aid to offer their perspectives. It will provide evidence to help us answer our relevance and effectiveness questions. This component will be implemented through in-country researchers using focus group and individual interviews.

Sampling approach

Sampling states

We identified Madhya Pradesh, Odisha and Bihar as states which have high levels of poverty and substantial UK development cooperation in a range of focus sectors and through different channels. However, we considered that Bihar would be less practical to visit given particular challenges to accessibility during the monsoon season, when our visits are scheduled. Hence, we selected Madhya Pradesh and Odisha.

Sampling programmes and investments

To select a sample of UK aid-funded programmes and investments in India for detailed assessment, we collated information on spending and investment of UK aid through all channels, from publicly available sources and information provided to ICAI by the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO), British International Investment (BII, formerly CDC) and other government departments. Using this information, we estimated what the UK spent and invested in India between 2016 and 2021 through the largest channels (see above).

We selected a sample of a total of 21 programmes and investments. The sample size balances the need to reflect the diversity of the UK’s aid portfolio in India with what is feasible in a single ICAI review. We considered larger programmes and investments for inclusion in the sample and purposively selected a sample that is broadly reflective of the level of aid flowing through different organisations, different types of spending and to different sectoral areas. We sampled ten bilateral programmes, two World Bank programmes, one Climate Investment Fund programme and eight BII (formerly CDC) investments. Of the BII investments sampled, two are part of its Catalyst portfolio, which makes higher-risk investments with the potential for greater development impact in poorer communities and places, and six are part of its main Growth portfolio.

We will carry out:

- ten assessments of UK bilateral programmes or funds operating in India, including:

- five funded by FCDO, two by the Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy, two by UK International Climate Finance and one by the Department of Health and Social Care

- five development capital programmes, three research and innovation programmes and two technical assistance programmes

- nine focusing on the identified core bilateral portfolio themes of climate and infrastructure (five) and economic development (four), with one focusing on health

- four operating in multiple countries, including India

- three assessments of multilateral programmes, including:

- two lending operations indirectly funded by FCDO contributions to the World Bank, focusing on economic development

- one development capital fund indirectly funded by UK International Climate Finance contributions to the multilateral Climate Investment Funds, focusing on green energy investments

- eight assessments of BII (formerly CDC) investments in India, including:

- four direct investments and four in investment funds

- one investment in a multisector fund, two in financial services, three in infrastructure, one in health and one in construction

- six investments as part of the Growth portfolio and two as part of the Catalyst portfolio.

Limitations to the methodology

The review questions will be challenging to answer in the context of a period of significant change and disruption. These changes and disruptions have included the merger of the Department for International Development and the Foreign and Commonwealth Office and the COVID-19 pandemic. We will bring our understanding of the strategic, organisational and operational context to bear throughout in answering the review questions.

A relatively small number of programmes and investments will be reviewed in depth. We have selected a sample of 21 programmes or investments in India to review in depth, from over 50 bilateral programmes active over the review period, further programming through multilateral channels and around 80 British International Investment (formerly CDC) investments that have been active over the review period. This will limit the extent to which we will be able to report findings which can be generalised across the whole of the UK aid portfolio in India. However, the sample is broadly reflective of the level of aid flowing through different organisations, different types of spending and to different sectoral areas. Furthermore, we will be able to triangulate findings from our programme and investment assessments with our strategic document review and strategic interviews, which will consider the whole of the portfolio in scope.

There will be constraints to assessing alignment with evidence of ‘what works’. There is limited literature relating to the effectiveness of aspects of the UK aid portfolio in India, including the use of development capital, research grants and ‘soft’ diplomatic power. The review will consider what evidence is available from the literature, as well as drawing on qualitative evidence from stakeholders. Areas where evidence on ‘what works’ is missing or inconclusive will be noted.

Risk management

Table 2: Risks and mitigation

| Risk | Mitigation and management actions |

|---|---|

| Difficulty in engaging companies that the UK has invested in and obtaining evidence | We will work closely with the sampled funds and investee companies to get their buy-in to the review. To encourage them to engage fully with us, we will use ‘non-disclosure agreements’ with British International Investment and other UK-funded development capital funds, ensure all team members have the necessary security clearance and respect all information security protocols. |

| The COVID-19 situation affects country visits | We will stay informed about the evolving situation and alter our plans accordingly. If necessary, visits could be carried out virtually. |

| The monsoon season impacts evidence collection because of travel difficulties | We will travel to states that are less affected by the monsoon season. |

Quality assurance

The review will be carried out under the guidance of ICAI chief commissioner Tamsyn Barton, with support from the ICAI secretariat. The review will be subject to quality assurance by the service provider consortium. Both the methodology and the final report will be peer-reviewed by Emma Mawdsley, professor of human geography at the University of Cambridge, an expert on development in India and the UK aid programme in India.

Timing and deliverables

The review will take place over a 12-month period, starting from March 2022.

Table 3: Estimated timing and deliverables

| Phase | Timing and deliverables |

|---|---|

| Inception | Approach paper: July 2022 |

| Data collection | Country visits: July – August 2022 Evidence pack: September 2022 Emerging findings presentation: October 2022 |

| Reporting | Final report: March 2023 |