UK aid to refugees in the UK

Acronyms and glossary

| Acronym | Definition |

|---|---|

| AASC | Asylum Accommodation and Support Contracts |

| ACRS | Afghan Citizens Resettlement Scheme |

| AIRE | Advice, Issue Reporting and Eligibility contract |

| ARAP | Afghan Relocations and Assistance Policy |

| COMPASS | Commercial and Operational Managers Procuring Asylum Support Services |

| CSO | Civil society organisation |

| DLUHC | Department for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities |

| EU | European Union |

| FCDO | Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office |

| GNI | Gross national income |

| ICIBI | Independent Chief Inspector of Borders and Immigration |

| IDC | International Development Committee |

| KPIs | Key performance indicators |

| MSVCC | Modern Slavery Victims Care Contract |

| NAO | National Audit Office |

| ODA | Official development assistance |

| OECD-DAC | Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development’s Development Assistance Committee |

| PAC | Public Accounts Committee |

| SDGs | Sustainable development goals |

| UASC | Unaccompanied asylum-seeking children |

| UKRS | UK Resettlement Scheme |

| UNHCR | United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees |

| Key term | Definition |

|---|---|

| Asylum backlog | The asylum backlog refers to the number of individuals seeking asylum in the UK who are awaiting a decision on their case. |

| Asylum seeker | An asylum seeker is an individual seeking international protection, whose claim has not yet been decided on by the country in which it is submitted. |

| Bilateral aid | Bilateral aid is official development assistance (ODA) provided for a specific purpose, normally a particular country, region or sector, which is given directly to recipient governments or delivered through other UK partners. |

| Case Resolution Directorate | The Case Resolution Directorate was established in 2007 to address an asylum backlog of nearly 450,000 asylum cases. It increased dedicated staff to manage processing decisions and digitised tracking systems. |

| Contingency accommodation | Due to capacity issues of initial accommodation [see definition below], contingency accommodation is used to house asylum seekers, including hotels, repurposed Ministry of Defence facilities, student housing and other self-contained accommodation. |

| COVID-19 | The coronavirus disease is a communicable respiratory disease that spread rapidly around the world from late 2019, resulting in the World Health Organisation declaring a pandemic in March 2020. |

| Financial year | The financial (or fiscal) year used in government accounting runs from 6 April to 5 April the following year. |

| In-donor refugee costs | ‘In-donor refugee costs’ is a reporting category used when donors report their ODA spending to the OECD-DAC. Donors can report some of the cost of supporting refugees or asylum seekers for the first 12 months of their time in a donor country as ODA under this reporting category. OECD-DAC has set out rules and clarifications for what costs donors can include. |

| Initial accommodation | Short-term housing, usually hostel-type, that can be full-board, half-board or self-catering. It is for asylum seekers who need accommodation urgently before their support applications have been fully assessed and longer-term or dispersed accommodation [see definition below] can be arranged. The amount of time in initial accommodation can vary. |

| Dispersed accommodation | Temporary accommodation for asylum seekers used on a longer-term basis while asylum claims are being processed. Accommodation is managed by contractors on behalf of the Home Office in local authorities across the UK. The amount of time spent in dispersed accommodation varies and it is not always possible to stay in the same property. |

| Leave to remain | Immigration decision that gives a person from outside the UK permission to stay. Leave to remain can be limited, thus expiring after a set period, or indefinite, allowing the non-UK national permanent residency. |

| Refugee | People who are outside their country of nationality and in need of international protection, and who have fled their country because their lives, safety or freedom are threatened by war, conflict, generalised violence, human rights abuses or persecution. |

| ODA spending target | The UK has an ODA spending target set in law at 0.7% of gross national income. Currently, the UK has set its commitment at 0.5% of gross national income. However, the target in law remains 0.7% and the UK has stated its commitment to return to this when fiscal conditions allow. |

| Resettlement | UNHCR has defined resettlement as the transfer of refugees from an asylum country to another state, which has agreed to admit them and ultimately grant them permanent residence. |

| Safeguarding | Safeguarding includes the protection of individuals from physical, psychological and emotional abuse, exploitation and neglect. |

| Spender and saver of last resort | In the case of UK ODA, FCDO is the ‘spender and saver of last resort’. This means that FCDO will have to adjust its own ODA spending at the end of each calendar year to ensure the 0.5% ODA spending commitment is met but not exceeded. |

| Value for money | Value for money in government spending is a measure of how well an intervention, project, programme, portfolio, contract, policy, etc optimises public value (social, economic and environmental), in terms of potential costs, benefits and risks. Value for money of aid spending should include attention to four Es – effectiveness, efficiency, economy and equity – and can only be achieved if the activity's objectives are SMART: specific, measurable, achievable, realistic and time-limited. Value for money definitions and the SMART objectives are set out in HM Treasury's Green Book. |

Executive summary

Under international aid rules, the first year of some of the costs associated with supporting refugees and asylum seekers who arrive in a donor country qualifies as official development assistance (ODA). This category of aid is referred to as ‘in-donor refugee costs’. The rationale is that supporting refugees with basic services and accommodation is a form of humanitarian assistance, wherever they are located, and can, therefore, be reported as aid. The rule has always been controversial as the funds remain within the donor country. It has become particularly problematic in recent years, as large-scale refugee movements have caused in-donor refugee costs to rise rapidly.

In 2022, ICAI estimates that core UK expenditure on in-donor refugee costs was around £3.5 billion, approximately one third of the UK’s total aid that year. The estimate is based on figures shared by government departments with ICAI between December 2022 and February 2023. The official figures may differ as a result of a quality assurance process taking place before the government reports its annual official statistics on international development spending. The provisional official statistics on UK aid expenditure will be published by the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO) in April 2023.

There are a number of reasons for the increase in UK aid spent on in-donor refugee costs, including the large visa schemes established for Afghan and Ukrainian refugees, increasing numbers of asylum seekers crossing the Channel, and a growing backlog in asylum claims processing. Due to a shortage of accommodation, the Home Office has housed refugees and asylum seekers in hotels, at a reported cost of £6.8 million per day in October 2022.

Because the UK, uniquely among major donors, sets a ceiling for its annual aid budget, more aid spent on indonor refugee costs means less available to spend in developing countries. The recent reduction of the UK aid spending commitment from 0.7% to 0.5% of gross national income (GNI) has caused in-donor refugee costs to absorb a growing share of a shrinking total. This rapid review examines the impact of these rising costs on the UK aid budget, and the effectiveness of the services provided to refugees and asylum seekers.

The impact of in-donor refugee costs on the UK aid programme

Soaring in-donor refugee costs have caused major disruption to the UK aid programme while at the same time not contributing to any of the priorities in the UK government’s International development strategy, published in May 2022. In July 2022, FCDO announced a pause on all ‘non-essential’ ODA spending, which lasted until November 2022. The pause was necessitated not just by the scale of in-donor refugee costs, but by their unpredictability. As the major aid-spending department and spender and saver of last resort, FCDO is responsible for ensuring that the UK government hits, and does not overshoot, its 0.5% ODA spending commitment. It does so by adjusting its own spending in response to ODA expenditure by other government departments. Lacking an accurate forecast from the Home Office of the sharply rising ODA spend on in-donor refugee costs, FCDO was forced to put its own programming on hold, despite the risk to its partnerships and the many people around the world who rely on UK development and humanitarian aid. While FCDO put in place criteria for making exemptions to the spending pause to protect the most vulnerable, the scale of the savings that the department had to make was so large that this was not sufficient to avoid all risks of harm. The department was also unable to undertake financial planning for the coming year.

To limit the impact, in November 2022 the chancellor temporarily raised the ODA spending limit by £2.5 billion over two years, amounting to an increase in the aid spending commitment from 0.5% to around 0.55% of GNI. This has only partially mitigated the disruption facing the UK’s aid programme. While FCDO has not published its budget allocations, the minister of state for development and Africa, Andrew Mitchell, informed the International Development Committee in December 2022 that there were still likely to be 30% budget reductions to bilateral aid programmes across the board.

One important consequence is that the UK’s ability to respond to global crises and humanitarian emergencies has been sharply curtailed. The UK’s bilateral humanitarian budget is now considerably smaller than its ODA spending on in-donor refugee costs, which has undermined its commitment to playing a leading role in the international response to global crises. This was seen in the limited UK response both to devastating floods in Pakistan in August 2022, and to the worsening drought in the Horn of Africa, which is expected to lead to widespread famine in 2023.

The diversion of UK aid resources away from emergency response to supporting refugees and asylum seekers in the UK represents a significant loss in the efficiency and equity of UK humanitarian aid. In-donor refugee support is an expensive way to spend ODA, compared to supporting crisis-affected people in their own country or region. The UK is, therefore, able to use its ODA budget to help far fewer people. It also runs counter to a key humanitarian principle that humanitarian action should give priority to the most urgent needs.

The UK’s approach to in-donor refugee costs creates little incentive for the Home Office and other departments to control their expenditure in this area. Home Office officials underlined their attention to value for money and said the alternative to expensive emergency accommodation through hotels would be widespread homelessness of asylum seekers. We are, nevertheless, concerned that the Home Office and other departments’ ability to spend an unlimited proportion of the UK’s ODA budget could undermine any incentive to undertake long-term planning to reduce costs. One of the stakeholders we interviewed described it as a blank cheque for the Home Office.

The UK’s method for calculating in-donor refugee costs is more transparent than that of many other donors. It seems to be in accord with guidance from the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development’s Development Assistance Committee, which oversees international aid statistics, but the UK’s use of modelling instead of reporting actual incurred costs carries risks of over-reporting. However, there are significant variations in how, and to what extent, other donors report their refugee costs. Australia and Luxembourg choose not to report any in-donor refugee costs as ODA. Comparing the approach of different donors based on their published methodologies on how they report in-donor refugee costs, ICAI found that some donors, such as Austria, Belgium, Canada, France and Iceland, calculate some ODA-eligible costs in a more conservative manner than the UK. This suggests that the UK could reduce disruption to its aid programme by adjusting how it reports in-donor refugee costs.

The quality and value for money of in-donor refugee spending

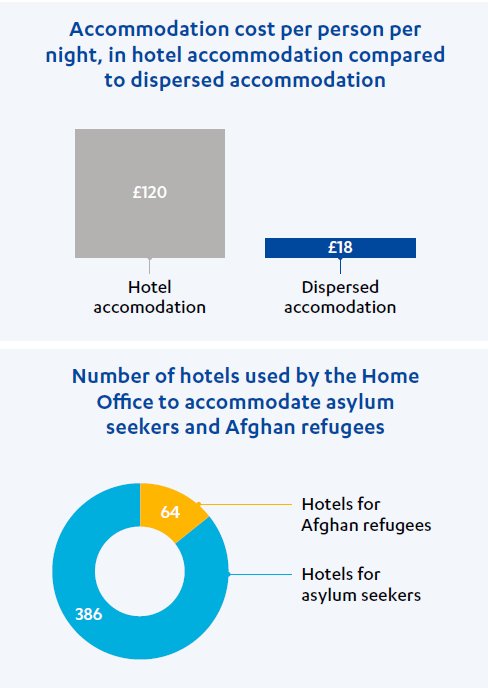

In recent years, the Home Office has faced a critical shortage of accommodation for refugees and asylum seekers. As of 14 March 2023, it used 386 hotels around the UK to host asylum seekers, up from around 200 in October 2022. In addition, in October 2022 we were told the Home Office used 64 hotels to accommodate Afghan refugees. While ICAI had initially been given a different, and larger, figure for the average cost of hotel accommodation, we were informed in March 2022 by the Home Office that it amounted to £120 per person per night (including catering and other services), compared to £18 for longer-term accommodation in houses and flats. While the Home Office has recently started planning long-term solutions, the short-term nature of its response to date has contributed to the spiralling costs. This has been exacerbated by a large and growing backlog in processing asylum claims, which results in many more people entering Home Office-provided accommodation than leaving, and longer stays in hotel accommodation for newly arrived asylum seekers. While the asylum system is not within ICAI’s scrutiny remit, it is clear that measures to speed up processing could help reduce emergency accommodation costs, thus lessening the disruption to the aid programme.

The Home Office engages private contractors to provide accommodation and services for asylum seekers. ICAI assessed how these high-value contracts were managed and found that the Home Office did not effectively oversee the value for money of the services. It has recently developed trackers to monitor and compare the cost effectiveness of different suppliers, but the key performance indicators (KPIs) that are being monitored are, overall, not appropriate for the task of ensuring that the right outcomes are being reached and that value for money is achieved. Without appropriate performance data and baselines, the Home Office’s ability to manage its suppliers in such a way as to encourage continuous improvement is limited. The KPIs for supplier performance are no longer considered to be effective and have not been changed for four years despite significant changes to the operating environment. The commercial contract management team has been significantly under-resourced since the inception of the contracts, and is only now in the process of recruiting the size of team required according to contract management best practice. In our review, we found that the officials charged with managing the contracts have not had the appropriate level of commercial experience for contracts of this value, according to UK government guidance. We were told by the Home Office in March 2023 that an open book audit of the contracts had been performed a year earlier, but we were not given documentation of its findings.

Several other scrutiny bodies have examined the Home Office’s support for asylum seekers and refugees over the past five years, including the Public Accounts Committee, the Home Affairs Committee, the National Audit Office and the Independent Chief Inspector of Borders and Immigration. Value for money concerns emerge as a consistent theme, along with urgent calls for the Home Office to resolve the accommodation crisis. We did not find evidence in our review that the Home Office had improved its contract management practices in response to earlier recommendations. In March 2023, the Home Office provided a list of improvements they are currently undertaking, including remedying the under-resourcing of the commercial contract management team, clarifying roles between commercial and service delivery teams, and strengthening commercial oversight. However, ICAI did not see evidence to verify this information or assess how these improvements are being implemented.

The UK has set up individual schemes for different groups of refugees and asylum seekers, which provide different levels of support and create unhelpful competition for resources, including for scarce accommodation. High-profile schemes for Afghans and Ukrainians are relatively well resourced, but have crowded out other categories, particularly schemes for resettling refugees identified by the UN High Commissioner for Refugees.

There is considerable variation across regions and local authorities, and between different hotels in the same areas, on the quality and level of services. Services are particularly limited for asylum seekers, and we found many examples of charities, community groups, hotel management and concerned individuals providing additional support to fill key gaps, such as donating winter clothes for newly arrived destitute asylum seekers. We are concerned at the high levels of inequity across the UK’s refugee and asylum seeker support, which runs contrary to the humanitarian principle of fairness (‘leaving no one behind’).

We are also concerned about the high level of safeguarding lapses we heard about in relation to schemes managed by the Home Office. Refugees and asylum seekers in hotel accommodation – particularly women and girls – face significant risks, especially of gender-based violence and harassment. There appears to be considerable variation between hotels as to whether asylum seekers are housed and treated in a gender-sensitive way, and whether hotel staff are properly vetted and trained. Home Office contractors do not have clear enough obligations to address safeguarding issues systematically, and safeguarding does not feature in their KPIs.

Recommendations

We offer the following recommendations to the UK government on how to improve the quality of aid spending on in-donor refugee costs and minimise the resulting disruption to UK aid.

Recommendation 1: The government should consider introducing a cap on the proportion of the aid budget that can be spent on in-donor refugee costs (as Sweden has proposed to do for 2023-24) or, alternatively, introduce a floor to FCDO’s aid spending, to avoid damage to the UK’s aid objectives and reputation.

Recommendation 2: The UK should revisit its methodology for reporting in-donor refugee costs, as Iceland did, with the aim of producing a more conservative approach to calculating and reporting costs.

Recommendation 3: The Home Office should strengthen its strategic and commercial management of the asylum accommodation and support contracts, both individually and as a group, to drive greater value for money.

Recommendation 4: The Home Office should consider resourcing activities by community-led organisations and charities as sub-contractors in the asylum accommodation and support contracts for dedicated activities to support newly arrived asylum seekers and refugees.

Recommendation 5: The government should ensure that ODA-funded in-donor refugee support is more informed by humanitarian standards, and in particular that gender equality and safeguarding principles are integral to all support services for refugees and asylum seekers.

Recommendation 6: The Home Office should strengthen its learning and be more deliberate, urgent and transparent in how it addresses findings and recommendations from scrutiny reports.

1. Introduction

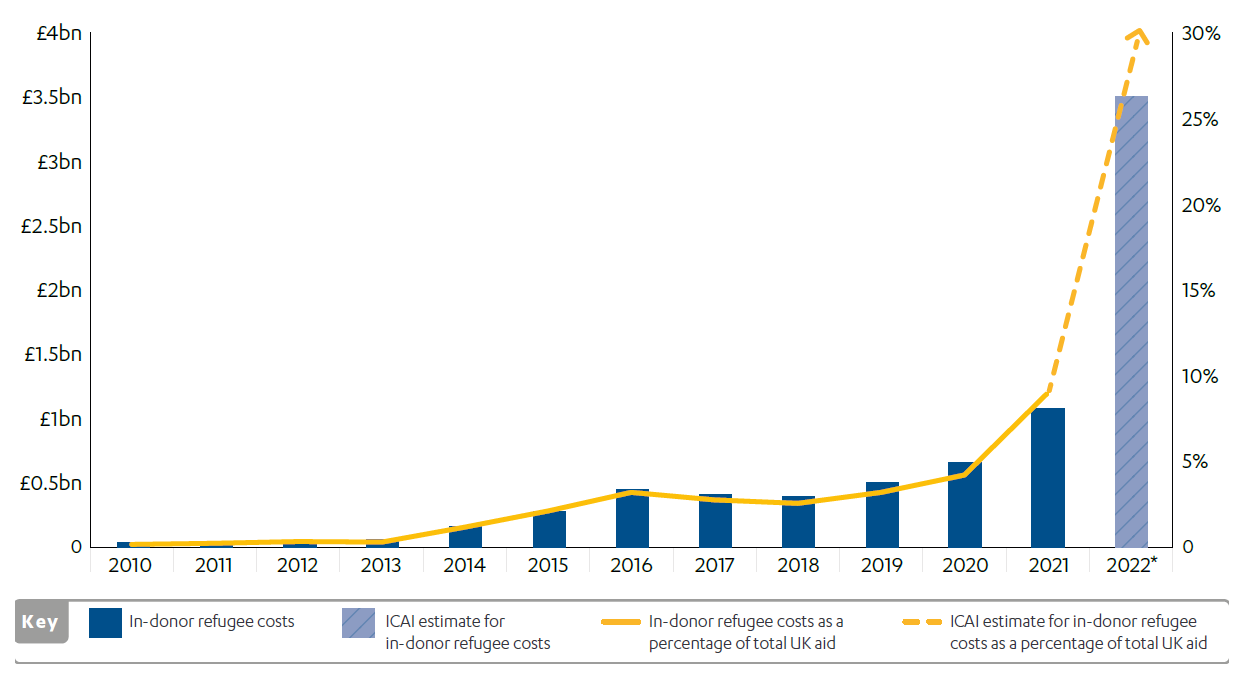

1.1 The amount of official development assistance (ODA) spent within the UK’s borders on accommodation and support for refugees and asylum seekers (known as in-donor refugee costs) has increased dramatically in recent years. From a negligible amount ten years ago, in 2021 this made up around 9% of all UK ODA, amounting to more than £1 billion. While official statistics from the government had not yet been released at the time of publication of this report, ICAI estimates that in 2022 the cost rose to around £3.5 billion and approximately one third of all UK aid that year (see Figure 1). ICAI’s estimate is based on the preliminary ODA spending figures departments were working with, updated in the period between December 2022 and February 2023. These data are not comprehensive but cover core UK spending on in-donor refugee costs. They have not yet been quality-assured, so the official statistics, which will be published by the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO) in April 2023, may differ.

Figure 1: UK spending on in-donor refugee costs, in absolute figures and in proportion to total aid, from 2010 to 2022*

*The spending figure and proportion for 2022 are ICAI estimates based on working numbers provided between December 2022 and February 2023, not official government statistics. ODA spend figures were taken from OECD QWIDS data to calculate the proportion of ODA spent on in-donor refugee costs.

Source: OECD Query Wizard for International Development Statistics, Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development, n.d., (accessed January 2023).

1.2 Under the international rules governing ODA, donors are permitted to report some of their spending on accommodation and support for refugees and asylum seekers during the first year after their arrival as international aid (a category of aid known as ‘in-donor refugee costs’). The rationale is that support for refugees is a form of humanitarian aid, wherever they are located. While the rule has always been controversial, it becomes particularly problematic when major conflicts cause in-donor refugee costs to spike. This happened in 2015-16, when large numbers of Syrian refugees travelled from regional host states to the EU. In August 2021, the Taliban takeover of power in Afghanistan led to the evacuation and flight of many Afghan refugees. In 2022, the Russian invasion of Ukraine led to 7.5 million refugees fleeing to European countries.

1.3 The sharp rise in in-donor refugee costs comes against the background of recent reductions in the UK aid budget, caused by the COVID-19 pandemic’s impact on gross national income (GNI) and the reduction in the UK aid spending commitment as a proportion of GNI. The reduction from 0.7% to 0.5% of GNI has magnified the impact of the increased costs, causing them to absorb a much larger share of a shrinking total. This rapid review aims to shed light on this category of aid spending which, until recently, was not well known to the public. It covers all UK ODA spent on supporting refugees and asylum seekers in the UK, with the Home Office as the main spender.

1.4 ICAI’s remit is only to review the use of the aid budget. We have not investigated the asylum claims processing system, detention practices or forced removals, since these activities are not eligible as ODA under the rules set by the Development Assistance Committee of the Organisation for Economic Development and Cooperation (OECD-DAC). Due to the rapid nature of this assessment, and the many different schemes and departments spending ODA on refugees and asylum seekers, the review could not cover all aspects of in-donor refugee costs with the same level of detail. It focuses attention on the UK’s main resettlement schemes and its asylum accommodation and support contracts, which together make up a large proportion of UK ODA on in-donor refugee costs.

1.5 The review complements recent reports by the Public Accounts Committee, the National Audit Office, and the Independent Chief Inspector of Borders and Immigration, as well as the International Development Committee’s report on the topic, published on 2 March 2023.

Box 1: How this report relates to the sustainable development goals

The sustainable development goals (SDGs), otherwise known as the global goals, are a universal call to action to end poverty, protect the planet and ensure that all people enjoy peace and prosperity.

ICAI’s reviews always describe how the ODA spending under scrutiny is related to furthering the SDGs. The topic of in-donor refugee support is unusual since it does not fit neatly under any SDG. This is partly to do with donors agreeing that in-donor refugee costs should be understood as a form of humanitarian assistance, not development aid.

![]() Goal 10: Reduced inequalities: SDG target 10.7 is on “orderly, safe, regular and responsible migration, and mobility of people, which includes the implementation of planned and well-managed migration policy”. This target falls under SDG goal 10, to reduce inequality within and among countries. There is no specific target for SDG 10 on refugees or forced migrants, which has led experts to describe an “SDG refugee gap”.

Goal 10: Reduced inequalities: SDG target 10.7 is on “orderly, safe, regular and responsible migration, and mobility of people, which includes the implementation of planned and well-managed migration policy”. This target falls under SDG goal 10, to reduce inequality within and among countries. There is no specific target for SDG 10 on refugees or forced migrants, which has led experts to describe an “SDG refugee gap”.

![]() Goal 5: Gender equality: The International Development Act, which guides all UK aid, includes the duty when providing humanitarian assistance to “have regard to the desirability of providing assistance … in a way that takes account of any gender-related differences in the needs of those affected by the disaster or emergency”.

Goal 5: Gender equality: The International Development Act, which guides all UK aid, includes the duty when providing humanitarian assistance to “have regard to the desirability of providing assistance … in a way that takes account of any gender-related differences in the needs of those affected by the disaster or emergency”.

1.6 The review questions are listed in Table 1 and address the relevance, coherence and effectiveness of the UK’s aid spending on in-donor refugee costs. The review findings in Section 4 are structured into two parts. Part one assesses the relevance and coherence of this aid spending, and Part two assesses the effectiveness and quality of the expenditure.

Table 1: Our review questions

| Review criteria and questions | Sub-questions |

|---|---|

| Relevance: How relevant is the UK’s approach to spending official development assistance (ODA) on in-donor refugee support to its International development strategy, its legal requirements towards refugees and asylum seekers, and to the OECD-DAC reporting criteria and international best practice in this area? | • How does the UK’s approach to ODA spending on in-donor refugee support align with the overall objectives and delivery of the UK aid programme? • How well does the UK’s approach to in-donor refugee support meet international best practice when benchmarked against other donors? • How does this spend align with key UK commitments, specifically the sustainable development goals and the global compact on refugees? • How is ODA eligibility, management and oversight organised and ensured? |

| Coherence: How well are different parts of the UK government working together to minimise the impact that sharp increases and fluctuations in spending on refugees in the UK have on the planning and delivery of the UK’s international development and humanitarian programming? | • How well do UK government departments forecast and communicate on in-donor refugee support costs and manage volatility in the context of the aid-spending target? • How well has the UK government managed disruption in the UK aid programme caused by the sharp rise in in-donor refugee support costs? |

| Effectiveness: How well are standards met for aid delivery in support of refugees in the UK? | • To what extent is value for money achieved through delivery contracts for refugee and asylum seeker accommodation and support? • Are adequate standards upheld in terms of quality, non-discriminatory and respectful care for all refugee and asylum seeker groups? • Are there effective systems and processes in place to identify the most vulnerable and ensure their needs and requirements are met, including safeguarding standards and gender-sensitive approaches? • How has the Home Office learned to improve delivery of in-donor refugee support from previous scrutiny reports? |

2. Methodology

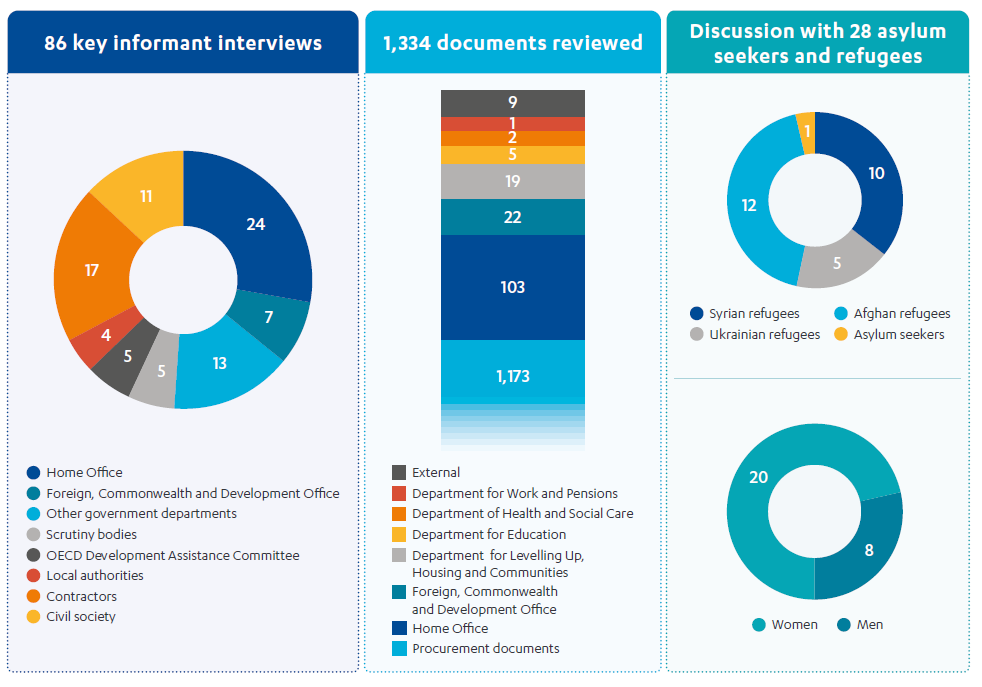

2.1 The methodology has six components, which together allow evidence to be triangulated and the analysis to be informed by a range of tools and perspectives.

2.2 Strategic review: This involves a combination of document review, key informant interviews and two expert roundtables, and included the following analytical tasks:

- Mapping changes over time in relevant factors including changes to asylum policy, official development assistance (ODA) methodology (especially on eligibility), spending departments, and ODA cost per refugee/asylum seeker from 2015 to 2022.

- Mapping UK ODA strategies, priorities and relevant international commitments and checking the relevance of spending on in-donor refugee support against these.

- Mapping, through document review and interviews, current and historical refugee resettlement schemes, and Homes for Ukraine, from 2015 to 2022.

- Reviewing existing scrutiny of this ODA spend and related activities, mapping recommendations by the National Audit Office (NAO), the Public Accounts Committee (PAC) and the Independent Chief Inspector of Borders and Immigration (ICIBI), and identifying follow-up activities on implementation of ODA-relevant recommendations.

- Recording the historical debate among Development Assistance Committee (DAC) donors on whether and how in-donor refugee costs should be ODA-eligible, and the UK’s role and position in this debate.

- Reviewing implications for the transparency, predictability and reliability of UK aid from the budget volatility caused by sharp rises and fluctuations in in-donor refugee costs.

2.3 Procurement and contract management analysis: We analysed the procurement, contract management and oversight of the current asylum seeker accommodation and support contracts. A sample approach was taken due to time and resource constraints.

2.4 Site visits: We undertook key informant interviews and group discussions during three short site visits in England and Scotland, meeting with local authorities, private service providers, and with civil society and community groups working with refugees and asylum seekers.

2.5 Stakeholder roundtables: We undertook two roundtable discussions with key stakeholders and experts among civil society, practitioners and researchers, with one on effectiveness questions and one on coherence.

2.6 Benchmarking exercise: We conducted a benchmarking exercise of the UK approach to in-donor refugee support against a selection of other DAC donors. The benchmarking was in two parts: (i) a quantitative exercise mapping the UK and ten other donors against a set of quantitative indicators drawn from the DAC database and other internationally comparable datasets; and (ii) a qualitative analysis of the approach taken by a smaller set of donors.

2.7 Engagement with affected people: While ICAI’s rapid reviews do not usually include engagement activities with affected people due to the short timeframe of the review, we undertook six focus group discussions with refugees from Afghanistan, Syria and Ukraine and one interview with an asylum seeker living in hotel accommodation. In addition to these organised engagement activities with a total of 28 refugees and asylum seekers, we also heard from asylum seekers and refugees on our three site visits.

Figure 2: Breakdown of interviews and focus groups conducted and documents reviewed

Box 2: Limitations to the methodology

Limited site visits: We carried out in-person research in three urban areas, visiting asylum seeker, Afghan and Ukrainian emergency accommodation, and interviewing a range of government, contractor and civil society organisation (CSO) stakeholders. Findings on quality and availability of services are not based on this limited number of site visits alone, but are cross-referenced with information from interviews with experts and representatives of CSOs, local authorities and the Home Office, as well as previous scrutiny reports from ICIBI, NAO and PAC. We did not visit rural locations or sites in Wales and Northern Ireland.

Limited number of interviews: There were a limited number of interviews with the Home Office and service providers on the procurement and contract management aspects of asylum services but, after delays, we were able to see a large number of contract documents and map gaps in the existing documentation. This allowed us to effectively use the limited number of interviews (conducted with three out of four of the private contractors and with the Home Office’s operational, commercial and finance teams) and provide a robust analysis of value for money and contract management.

Limited engagement with affected populations: We consulted 28 refugees and asylum seekers in six focus groups and one interview. This sample cannot produce generalisable results on its own, but it illustrated and emphasised challenges and issues that also emerged in the documentary evidence and stakeholder interviews. We found that evidence from the focus groups and from other sources tended to reinforce each other.

Limitation of scope: As we were only assessing ODA-funded activities, we did not assess: (i) the asylum determination process and reasons for the backlog (which greatly affect accommodation and support services); (ii) detention centres such as Manston; and (iii) forced removals such as the proposed Rwanda scheme, as these are not funded by ODA.

Limitation of time: We were not able to cover all aspects of UK aid spending on in-donor refugee costs due to a tight review schedule combined with a complex and large range of spending reported as in-donor refugee costs. Most notably:

- We gathered spending data from most of the government spenders of in-donor refugee costs in the UK, but not from HM Revenue and Customs or ODA-eligible costs for education and health administered by the devolved administrations. Our estimated spending figures for 2022, nevertheless, include the core part of UK in-donor refugee costs from the main spending departments.

- We did not assess services and accommodation for unaccompanied asylum-seeking children. This important topic was covered in a recent inspection report by ICIBI (March-May 2022). It remains a highly relevant issue of concern as unaccompanied minors continue to be placed in hotel accommodation.

- We conducted a preliminary review of material from the Modern Slavery Victim Care Contract, but did not conduct an in-depth analysis of this scheme. ICAI recently conducted a review of other aspects of the Home Office’s modern slavery scheme.

- We were not able to look at the Homes for Ukraine scheme to the same extent as the Afghan Citizens Resettlement Scheme and the asylum accommodation and support contracts.

3. Background

A global displacement crisis has led to rising refugee support costs

3.1 Official development assistance (ODA) spending on in-donor refugee costs in the UK has increased significantly since 2019, with costs accelerating in 2021 and 2022 (see Figure 1 above). The increase was particularly sharp in 2022 due to a combination of factors, including the following:

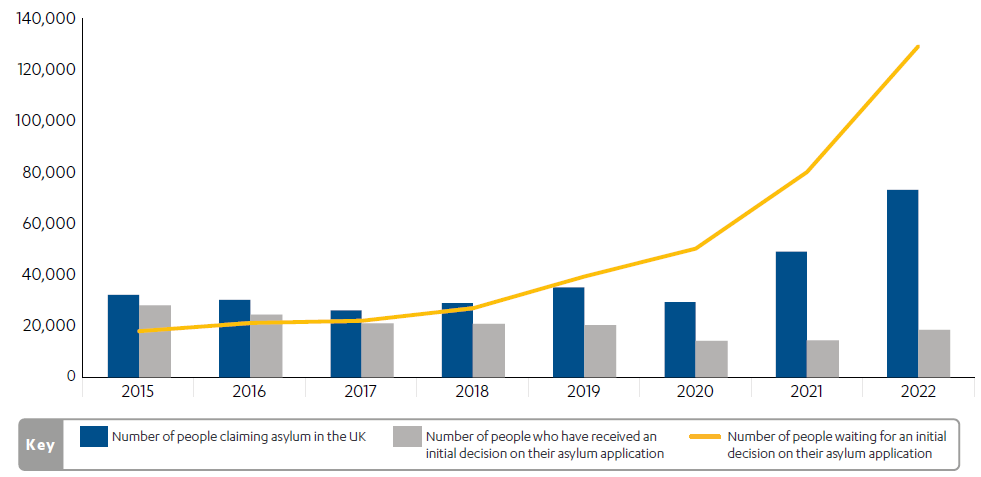

- Many people entered the asylum system, with 74,751 individuals claiming asylum in 2022, compared to 50,042 in the previous year. In 2022, 45,755 people arrived in small boats across the English Channel, of whom almost all claimed asylum on arrival.

- Large visa schemes came online for Afghan and Ukrainian refugees. Around 21,400 Afghans have arrived in the UK for resettlement since the Taliban took control of Afghanistan in August 2021. While data from the Home Office are not yet finalised, around 6,300 of these have been granted indefinite leave to remain in the UK under the mainly ODA-funded Afghan Citizens Resettlement Scheme (ACRS) and another 6,200 under the open-ended non-ODA-funded Afghan Relocations and Assistance Policy (ARAP) for Afghans who had worked directly with the UK government. After the Russian invasion of Ukraine on 24 February 2022, 165,700 Ukrainian refugees have arrived in the UK as of 6 March 2023, of whom 117,100 arrived under the mainly ODA-funded Ukraine Sponsorship Scheme, also known as ‘Homes for Ukraine’.

- A growing backlog in asylum processing, with 160,919 asylum applications (including main applicants and their dependants) awaiting decision on 31 December 2022, 109,641 of whom had waited more than six months. This has added to the pressures on a limited stock of accommodation for asylum seekers.

- The widespread use of hotels to house both Afghan refugees and people claiming asylum. Before the COVID-19 pandemic, hotels were used sparingly as initial or bridging accommodation for a few weeks. By October 2022, lengthy stays in hotel accommodation cost £6.8 million every day. When ICAI conducted site visits in November 2022, we were told there were 64 hotels for Afghan refugees (ACRS and ARAP) and some 200 hotels for asylum seekers. As of 14 March 2023, the Home Office told us the number of hotels used to accommodate asylum seekers had increased to 386.

“We were told that the accommodation was temporary, but we stayed for two years and there is still no news [about housing].”

Syrian woman refugee, UK resettlement scheme

“One of our problems is that we cannot be active [staying in a hotel room for long], my son couldn’t have any activity. Most of the time he wants to go shopping but we don’t go out. We don’t have any places in the hotel for us to speak to other families and talk about our problems.”

Woman from Iran seeking asylum

3.2 The rising number of refugees and asylum seekers arriving in the UK is part of a global crisis. In May 2022, the UN Refugee Agency (UNHCR) counted more than 100 million forcibly displaced people for the first time since it started keeping records. While most are internally displaced, the number of refugees – those fleeing outside their own country due to persecution or violent conflict – has been rising every year in the past decade and steeply in 2022. After the Russian invasion in February 2022, Ukrainians have taken over from Syrians as the world’s largest refugee population, with more than 7.8 million Ukrainian refugees recorded across Europe. Around one million Ukrainians had arrived in Germany by the end of 2022. Poland has had millions of refugees travelling through, with 1.5 million granted temporary protection in the country by January 2023. The Czech Republic, with a population of 10.5 million people, granted temporary protection to 485,124 Ukrainian refugees by January 2023. Across the world, host countries struggle to register and provide material support to refugees and asylum seekers in a time of economic downturn and high inflation, humanitarian crises, and the enduring impact of the COVID-19 pandemic.

3.3 There is no ceiling for how much of the UK aid budget can be spent on in-donor refugee costs. The methodology for determining ODA-eligible costs is based on data and estimates of how many refugees and asylum seekers arrive in the country, how much support they will need, and which forms of support are ODA-eligible.

3.4 The UK is committed to achieving but not exceeding its ODA spending commitment of 0.5% of gross national income (GNI). As the government’s ODA spender and saver of last resort, the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO) is required to offset any rise in in-donor refugee costs by reducing its own ODA expenditure. Furthermore, it is required to do so in the same year and must, therefore, engage in a complex forecasting and planning process in order to avoid overshooting the 0.5% ODA spending commitment. The chancellor’s autumn statement in November 2022 introduced some flexibility for the first time, adding an extra £1 billion in 2022-23 and £1.5 billion in 2023-24 to the ODA budget. This raised the ODA spending commitment from 0.5% to around 0.55% of GNI for the two financial years, in response to the increased aid spending on refugees and asylum seekers.

The UK’s position in the historical debate on reporting in-donor refugee costs

3.5 The Development Assistance Committee of the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD-DAC) has collected statistics on resource flows to developing countries since 1961 and introduced an agreed definition of ‘official development assistance’ (ODA) in 1969. In-donor refugee support was first included in the ODA definition in 1988. The rationale was that aid to refugees should count as ODA wherever it is provided. This was a controversial decision as the expenditure is within the donor country, and some donors, including the UK, chose initially not to use this reporting option.

3.6 In the 1990s, large-scale refugee movements led to an increasing share of ODA being categorised as in-donor refugee support. This led in the early 2000s to some DAC members, including the UK, Switzerland, Belgium and the US, voicing concern that aid funds were being diverted away from poverty reduction and humanitarian support in developing countries, undermining the credibility of ODA. Their view did not prevail, but the DAC Secretariat added ‘refugees in donor countries’ to the statistical annex of its development cooperation report, to make this category of expenditure more visible.

3.7 In 2010, the UK reported in-donor refugee costs for the first time, backdated to 2009. It has continued to report annually since then. According to UK officials, the decision to begin reporting in-donor refugee costs was to align UK aid statistics with international practice.

3.8 During the Syrian refugee crisis in Europe in 2015-16, unprecedented levels of in-donor refugee costs were reported as ODA. Discrepancies emerged across donors as to which expenditures were included. To improve consistency, a new round of consultations culminated in DAC members endorsing five clarifications to the reporting directives. The aim was to provide a blueprint for reporting in-donor refugee costs and to ensure that ODA-eligible activities were restricted to emergency support for newly arrived asylum seekers and refugees, aligned with humanitarian principles (see Table 2).

Table 2: The five DAC clarifications on reporting in-donor refugee costs

| 1. The rationale: | The rationale for counting in-donor refugee costs as ODA is that refugee protection is a legal obligation and providing assistance to refugees may be considered a form of humanitarian assistance. |

| 2. Eligible categories: | Asylum seekers and recognised refugees, following international legal definitions, are the two eligible categories covered. |

| 3. Time limitation: | The ‘12-month rule’ means that only costs incurred in the first 12 months after arrival are eligible. |

| 4. Eligible cost: | All kinds of temporary sustenance costs such as food, shelter and healthcare, and school for refugee children, are eligible, since these can be described as humanitarian in nature, but costs towards integration in the host country or any form of coercion, such as detention centres, are not. |

| 5. Methodology for assessing costs: | There is a need to adopt a conservative approach and to exercise caution when reporting against this category, to avoid overestimates and to protect limited resources available for ODA and the integrity of the ODA concept. |

3.9 The DAC requested members to publish their methodology for calculating in-donor refugee costs in line with the five DAC clarifications, to increase transparency and consistency between reporting practices. The UK shared its methodology with the DAC Secretariat in 2019 and published it in 2021. Not all donors have done so, notably including Germany. Two bilateral DAC donors (Australia and Luxembourg) have decided not to report any in-donor refugee costs as ODA at all (and so did not need to develop a methodology).

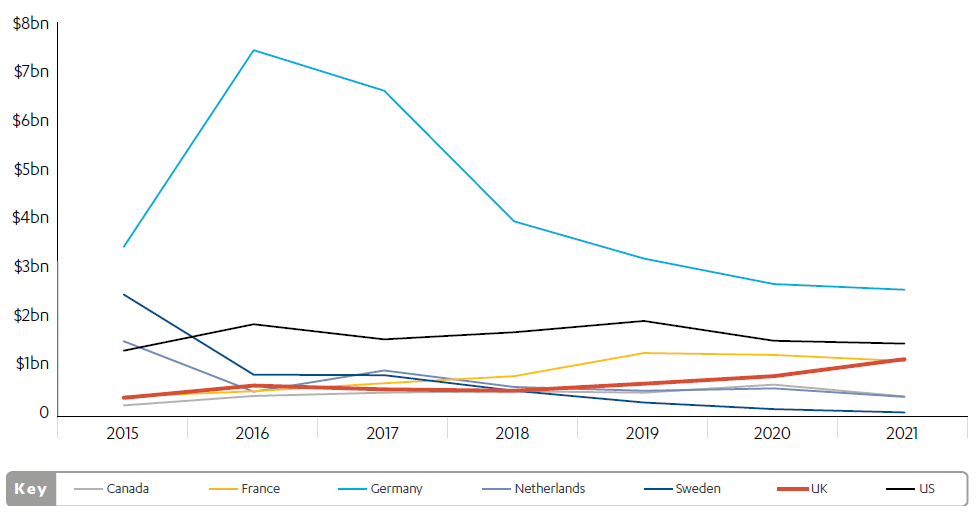

3.10 The DAC has asked members to provide disaggregated data on their spend and how much of the reported ODA pertains to administrative costs. In a 2022 report, the DAC Secretariat noted an issue with countries reporting lump sums for their refugee resettlement programmes without disaggregation. Only three DAC members (Austria, Italy and Sweden) track actual costs per individual refugee, allowing them to make accurate calculations of costs. The rest, including the UK, have methodologies to estimate costs based on assumptions rather than actual measurement. Figure 3 shows the trend in in-donor costs among a selection of donors, including the UK. Most donors stabilised or reduced their reported expenditure in this category after a peak around the 2015-16 refugee crisis in Europe.

Figure 3: Trajectory of in-donor refugee costs for a selection of donors, 2015-21

Source: OECD Query Wizard for International Development Statistics, Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development, n.d., (accessed January 2023).

How in-donor refugee costs are spent in the UK

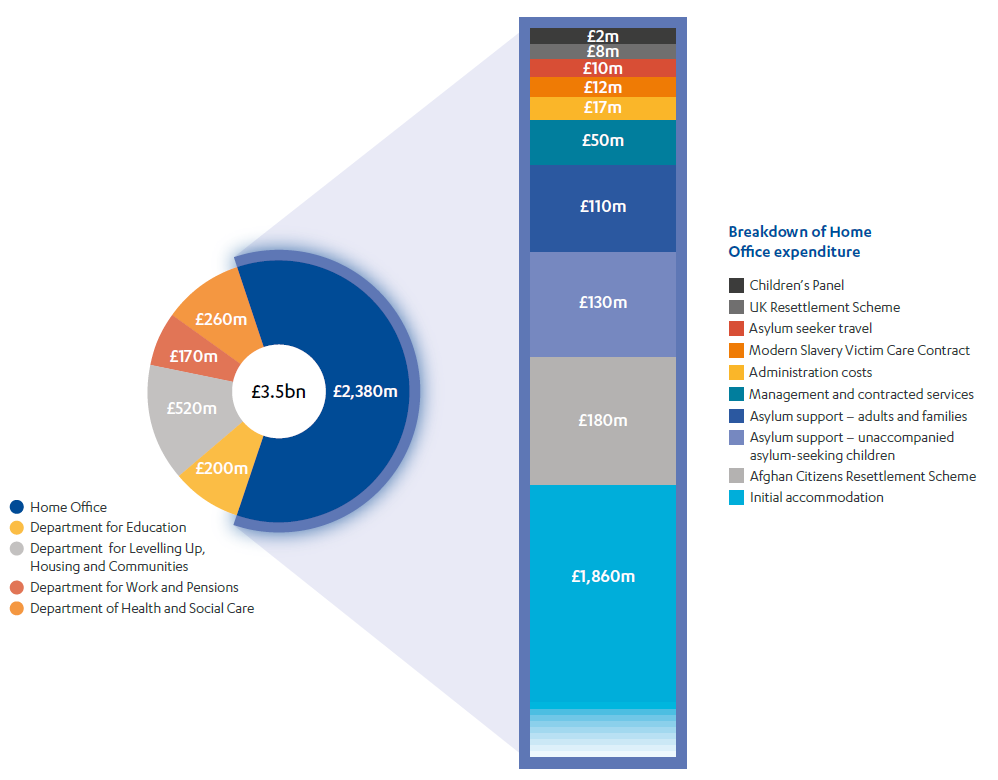

3.11 Although the main spender is the Home Office, the UK’s aid spending on in-donor refugee costs involves several departments. Table 3 provides estimated total UK in-donor refugee costs for 2022, broken down by the main departments. The estimates are based on the spending figures departments were working with up until the end of 2022 and early 2023. They are not the official statistics, which will come out in April 2023 after the spending data has been quality-assured. The figures may, therefore, change.

Table 3: Estimated total in-donor refugee costs per department in 2022

| Department | Estimated spend in 2022 |

|---|---|

| Home Office | £2,380 million |

| Department for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities | £520 million |

| Department for Work and Pensions | £170 million |

| Department for Education | £200 million |

| Department of Health and Social Care | £260 million |

| Total | £3,530 million |

How the Home Office spends in-donor refugee costs

3.12 The government department with by far the largest expenditure on in-donor refugee costs is the Home Office. The Home Office estimated a spend of almost £2.4 billion of ODA on in-donor refugee costs in 2022 (based on data provided to ICAI in February 2023). The main ODA costs incurred by the Home Office are for asylum services, in particular: (i) seven regional Asylum Accommodation and Support Contracts (AASC) with private service providers; and (ii) the Advice, Issue Reporting and Eligibility (AIRE) contract, an asylum seeker information and helpline service contracted to a charity.

3.13 The second-largest in-donor refugee cost for the Home Office is the Afghan Citizens Resettlement Scheme (ACRS), for Afghans evacuated or fleeing after the Taliban took control of Afghanistan in August 2021. In addition, the Home Office incurs in-donor refugee costs for the UK Resettlement Scheme (UKRS), which resettles vulnerable refugees identified by UNHCR, and the Modern Slavery Victims Care Contract (MSVCC), contracted to a charity. Finally, ODA is spent on in-donor refugee costs for asylum accommodation and support services for unaccompanied asylum-seeking children. This is separate to the AASC contracts.

Table 4: The Home Office’s main ODA-funded refugee and asylum seeker services

| Scheme/contract | Description and ODA eligibility (only in the first year) | Number of people |

|---|---|---|

| Asylum seeker accommodation, support and advice services (2019 – 2029) Asylum Accommodation and Support Contracts (AASC) Advice, Issue Reporting and Eligibility (AIRE) contract | Provision of accommodation, support and information to asylum seekers who arrive in the UK and whose claim to asylum is in the process of being determined. AASC is divided into seven regional contracts operated by three contractors: Clearsprings Ready Homes, MEARS and Serco. AIRE is operated by the charity Migrant Help. Support to unaccompanied asylum-seeking children is ODA-eligible, but not provided through AASC and AIRE. | 74,751 individuals (main applicants) claiming asylum in 2022. |

| Afghan Citizens Resettlement Scheme (ACRS) (January 2022 – present) | ACRS was launched to resettle up to 20,000 Afghans who assisted UK efforts in Afghanistan and stood up for democratic values and human rights, as well as vulnerable individuals at risk. ACRS has three pathways: • Pathway 1 is for vulnerable and at-risk individuals who arrived in the UK under the evacuation programme in August 2021. • Pathway 2 is for vulnerable refugees referred by UNHCR. • Pathway 3 is for vulnerable groups and at-risk individuals such as GardaWorld and British Council contractors, and Chevening alumni. | 6,292 people given indefinite leave to remain through Pathway 1. Four people have arrived under Pathway 2. No one has arrived under Pathway 3. |

| UK Resettlement Scheme (UKRS) (January 2021 – present) | The UKRS resettles vulnerable refugees identified by UNHCR and accepted by the UK. When launched, the scheme foresaw resettling up to 5,000 vulnerable refugees within the first year. No resettlement targets through the UKRS have since been set, and the number of arrivals is modest. | 2,237 people since January 2021. |

3.14 The Home Office also runs a scheme for Afghans that is not funded by ODA. Before the creation of ACRS, the UK government launched the Afghan Relocations and Assistance Policy (ARAP) in April 2021 as part of the UK’s preparation for withdrawal of troops from Afghanistan. The scheme, which is still open, is for Afghan citizens who worked for or with the UK government “in exposed or meaningful roles”. Eligibility is determined by the Ministry of Defence, after which relocation is handled by the Home Office. By early March 2023, indefinite leave to remain had been granted to 6,235 Afghan refugees through ARAP.

3.15 Table 5 shows how the Home Office estimated (as of January 2023) that its 2022 expenditure of almost £2.4 billion was shared out among its different activities. The ODA expenditure was mainly incurred by the AASC contracts, with almost £1.9 billion of ODA spent on providing initial accommodation in the first 12 months after arrival for asylum seekers, with most of the costs accrued by hotel accommodation.

Table 5: The Home Office’s in-donor refugee costs per activity or scheme, 2022

| Home Office activity or scheme | Estimated ODA spend |

|---|---|

| Initial accommodation through Asylum Accommodation and Support Contracts (AASC), including hotels and other contingency accommodation | £1,860 million |

| Asylum seeker travel, such as when moving to new accommodation or to attend asylum interviews | £10 million |

| Support for unaccompanied asylum-seeking children | £130 million |

| Children’s Panel, which advises and assists unaccompanied children through the asylum process | £2 million |

| Asylum support – providing dispersed accommodation and cash support to adults and families | £110 million |

| Afghan Citizens Resettlement Scheme (ACRS) | £180 million |

| Afghan Relocations and Assistance Programme (ARAP) | N/A – determined as not ODA |

| UK Resettlement Scheme (UKRS) | £8 million |

| Modern Slavery Victims Care Contract (MSVCC) | £12 million |

| Administration costs, such as staff costs for processing applications for asylum support, assessing accommodation needs and managing contractors’ provision of accommodation | £17 million |

| Management and contracted services, the Advice, Issue Reporting and Eligibility contract (AIRE) and fees to AASC providers and cash card providers | £50 million |

| Total estimated spend | £2,380 million |

How other government departments spend in-donor refugee costs

3.16 The largest ODA spender in this category after the Home Office is the Department for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities (DLUHC), which leads the Homes for Ukraine scheme, in collaboration with the Home Office. Most of this scheme is classified as ODA in the first 12 months.

3.17 Homes for Ukraine: In 2022, DLUHC spent ODA on in-donor refugee costs for the first time, as the lead department running the Homes for Ukraine scheme. In 2022, DLUHC spent a total of £520 million in aid to cover the following in-donor refugee costs:

- Grant payments to local authorities (known as tariffs) to provide ‘wrap-around’ support to Ukrainian arrivals: In 2022, local authorities were provided with £10,500 for each new arrival in their area under the Homes for Ukraine scheme, paid for the first year of a guest’s time in the UK. Of this, 69%, or £7,245 per person, was reported as ODA. The government has asked local councils to prioritise their funding to ensure guests are housed within safe arrangements, can access work and education, and are supported into long-term sustainable housing. (Separate funding is also provided to local councils for children’s education and childcare services by the Department for Education). Due to wider pressures on public finances and to reflect the fact that some Ukrainian arrivals return to Ukraine, the government decided to reduce the council tariff to £5,900 per person for arrivals entering the UK from 1 January 2023. If ODA continues to be reported as 69% of this amount, this would be £4,071 per new arrival in 2023.

- Thank-you payments for hosts: Sponsors are eligible for a monthly payment of £350 per household during the first 12 months of their guests’ stay as a thank-you for hosting, of which 100% is reported as ODA in the first year after arrival. The thank-you payments will be increased to £500 per month once the guest has been in the UK for 12 months. The higher payments should not be counted as ODA, due to the 12-month rule.

3.18 The Department for Education, the Department of Health and Social Care, and the Department for Work and Pensions spend considerable ODA funds on in-donor refugee costs, to cover education, healthcare and social security payments for refugees, including arrivals on the Afghan and Ukrainian schemes, and asylum seekers in the first year after arrival (see Table 6).

3.19 FCDO does not spend any ODA on in-donor refugee costs in the UK but is responsible for collating data from other departments and reporting the UK’s ODA spend on in-donor refugee costs to the OECDDAC.

Table 6: In-donor refugee costs incurred by other government departments

| Support type | Description of ODA costs | Responsible department |

|---|---|---|

| Homes for Ukraine scheme | Visa sponsorship scheme launched on 14 March 2022 to support Ukrainians, including hosting guests in private citizens’ homes. ODA is spent on a one-off payment per Ukrainian arrival to local authorities and on monthly thank-you payments to hosts (paid via local authorities). | Department for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities (lead) and Home Office |

| Education and schools | The cost to the school system of supporting asylum-seeking children (age 2-16) as well as children in the UK under the Afghanistan resettlement education grant, Homes for Ukraine scheme, Ukraine Families scheme and Ukraine Extension scheme. For the Homes for Ukraine scheme, children aged 2-18 are eligible. | Department for Education |

| Healthcare costs | The costs to the National Health Service of providing healthcare to asylum seekers as well as for Afghan arrivals under ACRS and Ukrainian arrivals under the three visa schemes: Homes for Ukraine, Ukraine Family scheme and Ukraine Extension scheme. Costs are estimated using healthcare unit costs or fixed tariffs, instead of counting actual health costs. | Department of Health and Social Care |

| Social security payments | Payments covering temporary subsistence, income benefits and disability benefits are charged to the ODA budget for Afghans under ACRS (all pathways), as well as for Ukrainians under all three visa schemes. Eligible costs include: Attendance Allowance, Disability Living Allowance (child), Pension Credit, Personal Independence Payment, Universal Credit. | Department for Work and Pensions |

Figure 4: Overview of estimated UK aid spending on in-donor refugee costs, per department, including more detail on Home Office costs disaggregated by activities and schemes*

4. Main findings

4.1 The findings from the review are organised in two parts. Part one assesses the impact of in-donor refugee costs on the coherence and relevance of the UK aid programme, while Part two examines the quality and value for money of the services for refugees and asylum seekers funded with aid. The criteria for assessing the value for money of aid spending is usually described as ‘four Es’: effectiveness, efficiency, economy and equity. For an activity to achieve value for money across these four criteria, its objectives need to be SMART: specific, measurable, achievable, realistic and time-limited.

Part one: The impact of in-donor refugee support costs on the UK aid programme

Soaring in-donor refugee costs have had a severely negative impact across the UK aid programme

4.2 Soaring in-donor refugee costs in 2022 forced the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO) to announce a spending pause on all its ‘non-essential’ official development assistance (ODA) spending in July 2022. This happened despite ODA spent on in-donor refugee costs not contributing to any of the priorities set out in the UK government’s International development strategy, published in May 2022. The pause lasted until November 2022. During that time, FCDO was unable to make scheduled payments on existing aid programmes, or any new commitments. It was also unable to engage in any forward planning for the financial year 2022-23, as confirmed by Philip Barton, permanent under-secretary at FCDO, to the International Development Committee (IDC) in October 2022. FCDO developed criteria for making exceptions to the spending pause for activities vital to protect against immediate threat to life and wellbeing, or which prevented people falling into humanitarian need, or prevented delays to accessing healthcare, primary education, sanitation and clean water. However, the scale of the savings that had to be made by FCDO were so large that these criteria were impossible to meet in full.

4.3 The pause was caused not just by rising in-donor refugee costs, but by their unpredictability. The Home Office was unable, until almost the end of 2022, to predict with any certainty how much of that year’s ODA budget it would spend on refugees and asylum seekers. This made “forward financial planning incredibly difficult”, in the words of Philip Barton, permanent under-secretary at FCDO. The minister of state for development and Africa, Andrew Mitchell, noted as late as December 2022: “[t]he reality is that I do not know what the full extent of the Home Office demands [on the UK aid budget] will be […] in the end, this is an open-ended cost and we do not know.”

4.4 As ODA spender and saver of last resort, FCDO is tasked with ensuring that the UK government hits its ODA spending target to a high degree of precision within each calendar year, adjusting its own expenditure plans over the course of the year in response to changes in the ODA spending and forecasts from other departments. As we have found in other reviews, the system functions effectively enough in years where both ODA expenditure and the UK’s gross national income (GNI) are relatively predictable. FCDO manages the target by using a range of programme and financial management tools, including shifting certain payments (typically contributions to multilateral organisations) between calendar years.

4.5 However, the rise in in-donor refugee costs has occurred against the backdrop of successive reductions in the UK aid budget. These resulted first from the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the UK’s GNI, and then from the UK government’s decision to reduce the aid spending target from 0.7% to a commitment to spend 0.5% of GNI. As a result, the UK aid budget fell to £11.4 billion in 2021, from a peak of £15.2 billion in 2019. In-donor refugee costs are, therefore, absorbing a larger share of a shrinking aid programme. Having already reduced its bilateral aid budget the previous year by 53%, compared to its spending in 2020, FCDO lacked options to find further reductions in 2022 without causing harm to its development partnerships and to the people relying on the services provided through UK aid.

4.6 Faced with the prospect of drastic and damaging reductions to the UK aid programme, in the 2022 autumn statement, the chancellor temporarily raised the ODA spending limit by £2.5 billion over a two-year period, amounting to an increase in the ODA budget from 0.5% to around 0.55% of GNI for this period. HM Treasury confirmed to ICAI that these funds will create more capacity within the ODA commitment for FCDO spending, with £1 billion extra for the financial year 2022-23 and a further £1.5 billion for 2023-24.

4.7 This adjustment only partly mitigates the disruption facing the UK aid programme, as it came too late to undo the effects of the spending pause and will be insufficient to offset the likely scale of in-donor refugee costs. While FCDO has not published its budget allocations, the minister of state for development and Africa, Andrew Mitchell, indicated to the IDC in December 2022 that there were likely to be 30% budget reductions to bilateral programmes across the board.

“Let us not beat about the bush – we are not a development superpower at the moment. That is bemoaned around the world by our many friends and people who look to Britain for leadership on international development.”

Minister of state for development and Africa, Andrew Mitchell, 6 December 2022

4.8 There was widespread agreement across the FCDO staff we interviewed that the disruption to aid programmes, coming on top of two successive years of budget reductions, has damaged the UK’s reputation as a donor and development partner. One example of the damage could be seen during the seventh replenishment drive for the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria. Having previously been the second-largest donor after the US to the Global Fund, the UK failed to make a pledge at the seventh replenishment conference in September 2022. When the spending pause was lifted, the UK finally pledged £1 billion for the seventh replenishment. This made the UK the Fund’s fourth-largest donor, with its contribution down from the £1.4 billion pledged at the sixth replenishment in 2019 and less than requested by the Fund.

The rise in in-donor refugee costs has sharply reduced the UK’s ability to respond to humanitarian crises

4.9 Rising in-donor refugee costs have led to dramatic reductions in the UK’s bilateral humanitarian aid, at a time of large-scale global displacement crises and humanitarian emergencies. UK commitments to support global relief and recovery efforts in 2022 have been significantly smaller and pledged later than in previous years.

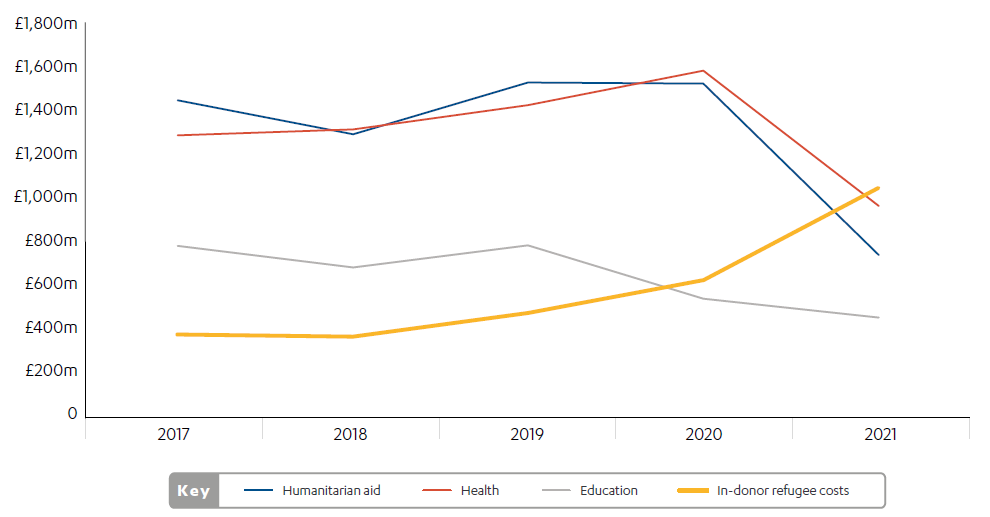

4.10 This trend started in 2021, a year when the overall ODA budget was reduced to 0.5% of GNI. In that year, in-donor refugee costs continued to rise sharply in absolute terms and doubled as a proportion of total UK aid, while bilateral aid for humanitarian assistance fell by more than half, from £1,531 million in 2020 to £743 million in 2021. Figure 5 shows how bilateral spending in areas prioritised in the UK International development strategy dropped from 2020 to 2021, with humanitarian spending particularly affected. While final figures for 2022 are not yet available, it is clear that humanitarian spending will continue on a downward trajectory.

Figure 5: Trends in absolute bilateral spend in key priority areas: humanitarian, global health and education, compared with in-donor refugee costs, 2017-21

Sources: Statistics on international development, various years, Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office: Aid spend 2021; Aid spend 2020; Aid spend 2019; Aid spend 2018; and Aid spend 2017. All accessed January 2023.

4.11 One example of the impact of the spending pause and reduction of the UK’s bilateral humanitarian budget was the UK response to the devastating floods in Pakistan in August 2022 (said to be the worst in the country’s history, leaving 33 million people in need of assistance). The UK government received strong domestic criticism for initially pledging just £1.5 million to the international response. By the end of January 2023, it had pledged a total of £36 million to the response and recovery efforts. This compares to pledges of €360 million (£316 million) from France and €84 million (£74 million) from Germany.

4.12 Another example is the drought and food insecurity crisis in the Horn of Africa, affecting Ethiopia, Kenya and, in particular, Somalia, which is expected to lead to widespread famine in 2023. The UK allocated £156 million in humanitarian aid to the region in the financial year 2022-23, down from £221 million in 2021-22. This is significantly lower than the UK’s £861 million contribution during the 2017 drought in East Africa and the Horn of Africa. The then minister of state for development, Vicky Ford, announced to the UN General Assembly in September 2022 that the UK was playing a leading role in the international response to the crisis. However, experts we consulted for this review noted that, while the UK had in fact played a leading role during the 2017 crisis, no such effort was apparent this time. In a statement to the IDC, the minister of state for development and Africa, Andrew Mitchell, confirmed that the UK’s humanitarian spending in response to drought in Somalia announced in November 2022 could not have been announced before the spending pause was lifted.

In-donor refugee costs at this scale are a highly inefficient response to global crises

4.13 According to the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development’s Development Assistance Committee (OECD-DAC), the rationale for treating support for refugees and asylum seekers as ODA is that it amounts to a form of humanitarian aid. However, this rationale becomes problematic when in-donor refugee costs rise to such a level that they displace other humanitarian expenditure. This situation has introduced major inefficiencies and inequities into the UK’s response to global humanitarian crises.

4.14 In-donor refugee support is an extremely expensive form of ODA, as compared to supporting crisis-affected people in their place of origin or displaced within their own region. This is particularly the case in the last two years, when an acute shortage of accommodation for refugees and asylum seekers in the UK has caused unit costs to rise dramatically. Part two of this section sets out our concerns around the value for money of this expenditure.

4.15 By shifting aid resources at this scale towards covering the costs of supporting refugees and asylum seekers in the UK, the UK is able to help far fewer crisis-affected people overall. Given the automatic way in which the UK calculates in-donor refugee costs as ODA, when this form of humanitarian spending becomes as large as it did in 2022, the UK government’s ability to make active policy decisions about how to allocate humanitarian funds to reach those in the greatest need is heavily curtailed. This is contrary to basic humanitarian principles which hold that humanitarian action should be carried out based on need, giving priority to the most urgent needs.

4.16 Providing access to protection in the UK for refugees is an important international obligation, as is providing support to ease the pressures on regional states hosting large numbers of refugees – both are key principles of the Global Compact on Refugees, to which the UK has committed. However, the imbalance in 2021 and 2022 between the UK’s spending on in-donor refugee costs and its humanitarian spending in developing countries undermines its ability to pursue its well-established aid policy of supporting states hosting large numbers of refugees and displaced persons in their regions. In recent years, the UK government has championed ‘refugee compacts’ with refugee-hosting countries, such as Jordan, Lebanon and Ethiopia. Under these compacts, the UK and other donors provide funding to support both refugees and host communities and to create jobs, while the host country provides refugees with increased access to basic services and the labour market. The objective is to create better living conditions for refugees and host communities and reduce the risk of ‘secondary displacement’, particularly to the EU.

The UK’s management of in-donor refugee costs creates little incentive for departments spending this aid to control their expenditure

4.17 During our interviews, we found that most staff involved in the delivery of in-donor refugee support did not know that the resources came from the UK aid programme. In the Home Office and the Department for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities (DLUHC), it was only staff involved in preparing ODA calculations who knew, not the operational teams providing ODA-funded services. Those who did know saw ODA eligibility as a mere accounting category.

4.18 The Home Office’s ODA spending on accommodation and basic sustenance for asylum seekers is a statutory obligation and not subject to any budget restrictions. The Home Office is not required to factor in the impact of its ODA expenditure on the rest of the aid programme or on people expected to benefit from UK aid in developing countries, as the resulting adjustments are done by FCDO as spender and saver of last resort. Many stakeholders interviewed noted the risk of perverse incentives, with one expert describing it as a ‘blank cheque’ for the Home Office.

4.19 In interviews Home Office officials insisted that value for money was constantly on their mind when managing their budget, whether or not it is classed as ODA. They noted that the sharp rise of costs was linked to an accommodation crisis that had forced them to house refugees in hotels, with high costs in both human and financial terms. We acknowledge that the Home Office has made considerable efforts to find acceptable accommodation in difficult conditions. The alternative might be homeless asylum seekers, of which there are reported to be at least 70,000 in France.

4.20 Nonetheless, we are concerned that the lack of limitation on how much of the UK’s aid budget can be spent by the Home Office as in-donor refugee costs militates against long-term planning to reduce costs. The Home Office does not need to finance much of its extensive use of very expensive contingency accommodation by making cuts elsewhere in its own budget, although it does have to negotiate with HM Treasury to go above its initial ODA allocation for the year. There is also less incentive from a financial perspective for the Home Office to reduce the backlog and long processing time for asylum applications since much of the resulting cost is borne by the aid budget.

Cross-government oversight and cooperation to manage in-donor refugee costs are not transparent, and are inadequate for protecting the integrity of the UK aid budget

4.21 Cross-government reporting on spend: There is a system for other government departments to report their ODA spend and forecasts to FCDO, which is tasked with compiling and reporting the UK’s aid expenditure. However, due to the considerable uncertainties in forecasting the level of refugee and asylum seeker arrivals and the cost of their support, the quarterly reporting to FCDO does not help them predict the budget for their own aid programme with any certainty.

4.22 Determination of ODA eligibility: This is the responsibility of the accounting officer in the government department that spends ODA. FCDO corresponds on behalf of the UK government with the DAC Secretariat to confirm eligibility. There was no cross-government deliberation on whether and how to include a particular cost as ODA, such as the £350 per month welcome payments to UK hosts of Ukrainians arriving on temporary sponsorship visas, or on the decision to define one Afghan visa scheme, Afghan Citizens Resettlement Scheme (ACRS), as ODA and not the other, Afghan Relocations and Assistance Policy (ARAP). There does not seem to have been a principled cross-government discussion of the implication for in-donor refugee cost rules of determining Afghan and Ukrainian visa schemes (rather than refugee protection schemes) as eligible for spending within this ODA category. Finally, the lack of a cross-government mechanism for determining eligibility also means that there was no formal cross-government forum in which to consider the impacts of rising in-donor refugee costs on the objectives of the UK International development strategy and the integrity of FCDO’s aid programme. The new cross-government ODA Board announced in February 2023 is, therefore, a highly welcome addition. The board is tasked with looking at costs and value for money across the UK ODA budget and is co-chaired by the chief secretary of HM Treasury and the minister of state for development and Africa. It remains, however, to be seen how successful the board will be in protecting the integrity and coherence of the UK aid budget.

The UK’s method for calculating in-donor refugee costs seems to be within the rules but does not follow the OECD-DAC guidelines on a conservative approach

4.23 The UK reports to OECD-DAC in a timely way and with a reasonable level of detail. It is among the better of the DAC donors on the quality of its reporting, in a setting where the general standard of reporting is low. In 2019, after the DAC updated its guidance, the UK published a detailed methodology on how it adheres to the DAC’s five clarifications to calculate its in-donor refugee costs (see Table 2 in Section 3 of this review on the clarifications). The methodology was discussed with the DAC Secretariat before being published on the OECD website in February 2021. It describes which services for refugees and asylum seekers are deemed ODA-eligible, and how the costs for each are calculated. The costing methodology is complex, using modelling to derive unit costs, with various assumptions and estimates.

4.24 The UK’s reporting methodology appears to meet the DAC rules. The UK also consults with the DAC from time to time on whether schemes or expenditure categories are eligible. HM Treasury, the Home Office and FCDO agree that the methodology allows for an objective determination of whether a particular cost category is ODA-eligible and argue that if a cost meets all the eligibility criteria it must be reported as ODA in its entirety. There has therefore been no adjustment of the UK’s ODA reporting practice in response to the spike in in-donor refugee costs.

4.25 We find, however, that there are other DAC members which have taken a more conservative approach to reporting, while two DAC donor states, Australia and Luxembourg, do not count any refugee or asylum support costs as ODA at all. Belgium does not include support costs for asylum seekers whose application for refugee status ultimately fails, and its methodology only takes into account the number of people granted refugee status. Iceland does not include costs for asylum seekers arriving from safe countries in cases where close to 100% of applicants from that country are rejected. France does not include education for refugee and asylum-seeking children in its in-donor refugee costs and only began to include healthcare costs in 2019. Belgium only includes marginal costs such as textbooks and school supplies when counting ODA-eligible education costs.

4.26 Furthermore, the UK’s extensive use of modelling and unit pricing to calculate costs increases the risk of higher levels of reporting. Only three donors, Austria, Italy and Sweden, report only actual, measurable costs and keep data bases to track ODA expenditure at the level of individual refugees and asylum seekers, while the DAC clarifications ask all donors to report actual expenditure as far as possible and the DAC offers support to help states achieve this. Modelling and unit pricing may lead to overreporting. For instance, DLUHC pays tariff grants to local authorities as part of the Homes for Ukraine scheme. In 2022, the tariff grant was £10,500 per Ukrainian who settled in the local authority area, of which 69% would be charged to the ODA budget. The guidelines provided to local authorities on how the tariff grant should be spent include a range of humanitarian (ODA-eligible) and integration (non-ODA-eligible) aims, without specifying how much of the funding should be spent in different categories. Local authorities can roll unspent funds from tariff grants provided in 2022-23 over into 2023-24. If the UK tracked expenditure at the level of individual refugees, then it would be able to work out how much of the actual local council expenditure is ODA-eligible. But due to the use of modelling based on unit costs, and assumptions of how local authorities will spend the funding, we cannot confirm that DLUHC can ensure that no more than 69% of the funds are spent on ODA-eligible activities, or that the 12-month rule for spending of in-donor refugee costs is always followed.