UK aid to Sudan

Executive summary

In April 2023, after decades of civil conflict and international isolation, Sudan descended once again into open war, further destabilising a fragile region and triggering the world’s largest humanitarian crisis. Over 30 million people are in need of assistance within Sudan and another 4 million have sought refuge in neighbouring countries. This multifaceted regional crisis presents an important test of the UK’s ability to combine its diplomatic, development and humanitarian tools and lead an effective international response – especially in a context of declining global aid resources.

This review by the Independent Commission for Aid Impact (ICAI) assesses the UK’s support to Sudan in the period before the outbreak of conflict and its response to the crisis after April 2023, focusing on four questions: how the UK demonstrates responsible global leadership; how it advances its commitments to women and girls; how it forges and sustains genuine partnerships with international, regional and local actors; and how it supports an effective humanitarian response in a volatile and resource-constrained environment. The review looks back over the past six years, from the hopeful period of democratic transition that followed President Omar al-Bashir’s fall in 2019, through the October 2021 military coup and open warfare since April 2023. The aim is to draw lessons that can strengthen UK engagement in Sudan and other fragile and conflict-affected settings worldwide.

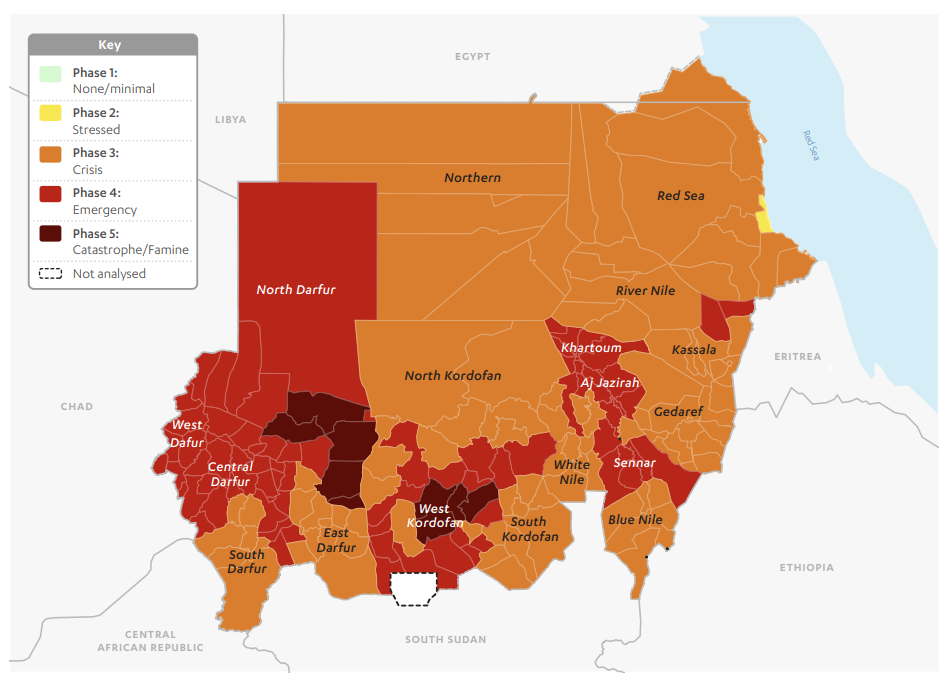

Sudan’s complex and rapidly evolving context has required continual reassessment and repositioning from international partners like the UK. What began in 2019 as a promising but fragile opportunity for reform and stabilisation has culminated in the near-total breakdown of the state, including the destruction of the capital, Khartoum, paralysis of government institutions and basic services, the collapse of food systems, and mass population displacement. Today, two-thirds of the population requires humanitarian assistance, with over 12 million people displaced and famine conditions in multiple areas. For humanitarian actors, Sudan presents one of the world’s most difficult operating environments, given its huge size, vast needs, severe access constraints and rapidly shifting conflict dynamics. The spillover into neighbouring states and beyond has deepened instability in an already fragile region.

Over this period, the UK has shifted from an initial focus on governance and economic reform to a primarily humanitarian portfolio, doubling its annual spending to £231.3 million in the financial year 2024–25 for the humanitarian response in Sudan and the region. In 2024, Sudan was designated one of three priorities for UK humanitarian aid, alongside Ukraine and Gaza, signalling the UK’s intention to play a leading role in the international response. This objective has been made more complex by the contraction in global aid flows, driving calls for urgent reform of an international humanitarian system in crisis. Despite the UK’s efforts, Sudan remains one of the world’s most underfunded humanitarian crises, relative to its needs.

“Many have given up on Sudan. That is wrong… We simply cannot look away.”

David Lammy, London Sudan Conference: Foreign Secretary Opening Remarks, 15 April 2025

This review involved a literature review, desk reviews of UK strategies and programme documents, a perception survey among UK partners, and interviews and focus groups with more than 150 key government and non-government stakeholders and experts in the UK, Sudan and across the region. While security restrictions prevented in-person visits to Sudan, Chad and South Sudan, we held in-person consultations with UK staff, implementing partners and other donors in Ethiopia and Kenya, while local research teams engaged with Sudanese refugee and diaspora organisations in Kenya and Uganda. The review encountered a number of limitations, including participation fatigue among Sudanese actors and limited hard data on the longer-term outcomes of UK programming. While the Sudan conflict has impacted countries across the region, this review focuses only on two neighbouring countries, Chad and South Sudan.

Findings

Responsible global leadership

During the 2019–21 period, the UK played a prominent diplomatic and development role in supporting Sudan’s political transition. It helped establish and strengthen international coordination platforms and align messaging among international actors. It was active in the negotiation of the Juba Peace Agreement between Sudan’s transitional government and various armed groups, and in securing passage of the Security Council resolution that established the UN political mission, UNITAMS. Its economic programming helped Sudan meet the conditions for international debt relief, unlocking the country’s access to international development finance. UK support for economic reforms included an £80 million contribution to the World Bank’s Sudan Transition and Recovery Support Trust Fund, which provided social protection to over 3 million people before being repurposed to humanitarian assistance. Since the outbreak of conflict in 2023, the UK has intensified its international leadership through Security Council engagement, high-level diplomacy and awareness raising, including by co-hosting the April 2025 London Sudan Conference. It has also maintained leadership roles in donor coordination in Sudan, Chad and South Sudan.

The review finds that the UK has in many instances demonstrated credible political leadership and strong convening power, drawing on deep networks that are valued by stakeholders. However, its influence has been inconsistent, limited by periods of reduced ministerial engagement, budget volatility and institutional disruptions. Cross-government engagement has been underdeveloped, including on the defence and migration aspects of the crisis. UK aid budget reductions in 2021–22 sharply reduced spending and caused damage to relationships, although the 2024 designation of Sudan as a UK priority country and related funding increase have helped to restore credibility. The UK’s humanitarian and governance programmes have been adaptable in a volatile environment, but delays in business case approvals have hampered agility. Regionally, the response has not been fully adapted to the cross-border nature of the conflict, which may give rise to imbalances in support between refugees and host communities. While the UK’s convening role in Sudan and neighbouring countries remains strong, partners are concerned about funding predictability and the lack of an explicit regional strategy to address spillover effects in Chad and South Sudan.

Women and girls

The challenges facing women and girls in Sudan are immense. In addition to entrenched inequality and long-standing harmful cultural practices such as child marriage and female genital mutilation (FGM), they now face large-scale conflict-related sexual violence (CRSV) – defined as acts of sexual violence that are directly or indirectly linked to a conflict. The UK has made gender equality a central objective in its response, in accordance with its commitments under the International Women and Girls Strategy (2023–2030). It has helped raise global awareness of CRSV and contributed to support services for survivors. Before the outbreak of conflict, the UK played a leading role in efforts to tackle harmful social norms through flagship programmes on FGM. These helped to promote legal reforms, strengthen services, encourage social change and reduce prevalence rates, although continued donor investment combined with sustained national and local commitment would be needed if FGM is to be eliminated in Sudan. Since the conflict broke out in 2023, the programme has pivoted to also provide medical and psychosocial support to victims and survivors of CRSV, which is a pervasive feature of Sudan’s brutal war. However, the UK opted not to pursue a more ambitious approach towards the protection of civilians, including from sexual violence, given political obstacles and administrative resource constraints.

The UK actively promoted women’s participation in political and peace processes during the transition period, shifting to subnational initiatives after the coup and supporting women’s inclusion in the pro-democracy movement. However, many Sudanese women interviewed for this review felt that advocacy from the UK and other international partners had not been matched by sustained support, and suggested that opportunities to strengthen women’s participation in peace negotiations had been missed. UK support for women-led organisations is mostly through intermediaries. While this support has helped build the capacity of women-led organisations, the model the UK uses has also positioned these organisations as downstream partners, delivering activities chosen by others, thereby limiting their ability to shape priorities and programme design.

Spending on gender equality-focused programming fell sharply between 2020 and 2022 as a result of wider UK aid budget reductions, before recovering in 2023. However, the proportion of funding going to gender equality-focused programming has remained consistently above 80%. The review found that consideration of gender equality objectives has been mainstreamed across the UK’s governance, economic empowerment and humanitarian programming, and that vulnerable women and girls have been consistently prioritised in UK humanitarian support. The UK has also supported a range of other activities, such as data collection. However, there is no robust indication of how effective this mainstreaming has been in supporting better outcomes for women and girls, partly due to the volatile context making measurement of impact difficult. Direct, targeted programming to support women and girls with improved access to sexual and reproductive health services and increased economic opportunities is relatively limited. Given the highly gendered nature of the conflict, and structural barriers to achieving lasting outcomes for Sudanese women and girls, the overall international support from the UK and other donors is inadequate, as noted by many stakeholders interviewed for this review.

Genuine partnership

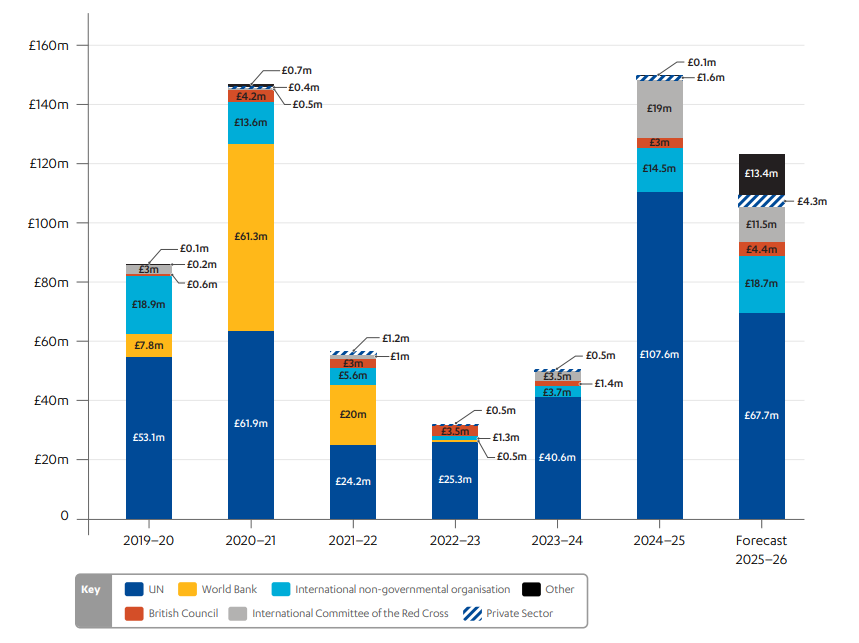

The UK has adapted its approach to partnership across the transition (2019–21), coup (2021–April 2023) and conflict (April 2023 onwards) periods. It backed Sudan’s civilian-led institutions during the transition, supported trade union and civil society reform, and facilitated public dialogue between citizens and government. After the coup, it suspended direct support to the de facto authorities while deepening engagement with civil society, including through constitutional workshops and support for pro-democracy coalitions. The UK has consistently worked through multilateral channels, backing African Union (AU) and subregional mediation efforts and helping shape UN mandates, while working closely with international non-governmental organisations (INGOs), the World Bank and the International Committee of the Red Cross. In its humanitarian response, it has supported a diverse network of actors, including UN agencies, INGOs and, indirectly, local organisations. This includes the UK’s contribution to the UN-managed Sudan Humanitarian Fund, which in 2024 channelled 37.5% of funds through local responders.

The review finds that UK partnerships have been enhanced by the calibre of Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO) personnel, whose expertise and networks have enabled constructive dialogue and coherent international messaging. However, in the period after the UK was forced in 2023 to evacuate Khartoum and shift its operations to neighbouring countries, it terminated most of its key Sudanese staff in advisory and programme roles. The government informed us that attempts at finding ways of continuing their employment were unsuccessful for various legal and operational reasons. This significantly weakened its capacity to engage with Sudanese actors at national and subnational levels, as well as its institutional memory and programme management capacity. Operating from Addis Ababa and Nairobi, British Office Sudan remains under-resourced for such a complex response, with short postings leading to high staff turnover and stress-related wellbeing concerns. Furthermore, FCDO’s surge mechanisms for crisis situations – rosters for business-critical roles such as Temporary Deployments Overseas – have not proved adequate given the scale of response. The UK has played an active role in donor coordination, and now has an opportunity to show leadership in collective donor action to respond together, not only at an operational level but also at a strategic level, to the new funding context, given the significant shortfall in international support for the humanitarian response.

Partnerships with the AU and UN have generally been strong, with a range of UK efforts to strengthen their capacity. However, influence by the UK and other donors has not succeeded in overcoming UN performance gaps, many of which are a result of restrictions and delays imposed by the parties to the conflict. ICAI was told that the UK is actively working with partners to address these issues. Implementing partners value the UK’s flexibility and technical expertise as a funder, but point to short funding cycles, delayed approvals and limited transparency over resource allocation as constraints on predictability and effectiveness. FCDO told us that there are plans to introduce some multiyear funding which, if confirmed, would improve this situation. The UK supports the international commitment to ‘localisation’, which FCDO understands as supporting local leadership of the response, for example through the transfer of power, including control of resources. However, this commitment is yet to translate into major shifts in funding practice. Complicated funding rules and limited UK programme management capacity limit the scale and quality of funding that can be allocated to local organisations, and there is little evidence of the UK involving local partners in priority setting. Engagement with Sudanese diaspora organisations has been ad hoc, which is a missed opportunity to use the diaspora’s contextual knowledge and community networks to strengthen the UK’s approach.

Effective humanitarian response

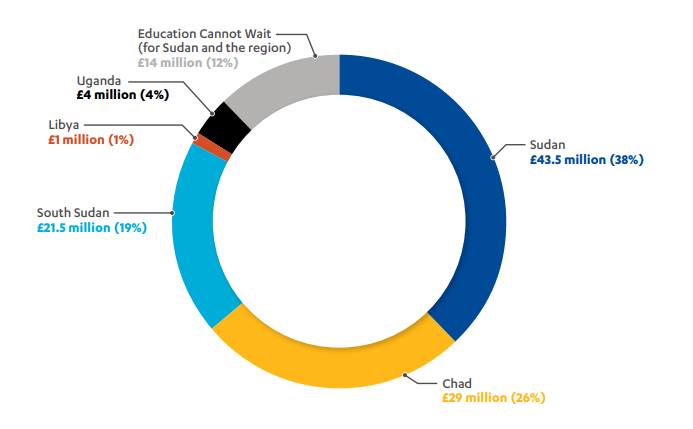

The UK is a significant humanitarian actor in Sudan and neighbouring countries, having adapted its funding and delivery mechanisms since April 2023 to respond to the unprecedented scale of displacement, food insecurity and protection needs. Inside Sudan, support has focused on food security, malnutrition treatment, protection and cash transfers, channelled through multilateral agencies, INGOs and the Sudan Humanitarian Fund, plus funding for an ‘Enabling Facility’ to strengthen data collection and coordination. In South Sudan, the UK has integrated its response to the Sudan crisis into established humanitarian and resilience programmes such as the South Sudan Humanitarian Assistance and Resilience Programme (SSHARP) and in its health and education programming which supports internally displaced people, refugees and host communities. In Chad it has scaled up rapidly, using flexible instruments like the Sahel Regional Fund to become a key donor to the refugee response in eastern Chad, bordering Sudan’s Darfur region. Across all three countries, the UK has leveraged its flexibility, technical expertise and partnerships to deliver timely assistance, advocate for protection and access, and elevate the crisis internationally, doubling aid to the humanitarian crisis to £231.3 million in financial year 2024–25.

The review finds that the UK has demonstrated political and operational leadership in the humanitarian response, through strong technical analysis, evidence-based planning and close coordination with key UN agencies. It has responded rapidly and flexibly to the refugee emergency in Chad and ensured that Sudan-related needs were integrated into existing South Sudan programmes. However, in both these neighbouring countries, it is essential that the UK’s prioritisation of the Sudan crisis does not divert resources and attention in politically fragile contexts from other, pre-existing humanitarian needs. The UK’s strong technical capacity on famine prevention is recognised by partners. However, its prevention work in Sudan has been undermined by limited programme management capacity and access constraints. Flexible UK funding instruments have the potential to bridge humanitarian and development efforts, but short funding cycles, disbursements late in the calendar year and limited predictability have hampered effectiveness. The UK’s use of flexible business cases has contributed to adaptability in an evolving crisis. However, overstretched teams and complex approval processes have slowed decision making and hindered learning and innovation. Finally, FCDO’s cautious security stance has curtailed staff access to field locations, limiting their ability to oversee partners and engage with affected communities.

Recommendations

For the UK government

- Recommendation 1: Ensure sustained high-level political attention to the Sudan conflict and humanitarian crisis, including by strengthening cross-government ownership and coordination.

- Recommendation 2: Develop and implement a clear regional approach to the Sudan conflict, aligning strategies across Sudan and neighbouring countries.

- Recommendation 3: Align delivery capacity with ministerial ambition by backing Sudan’s priority country status with multi-year, protected funding and by adequate capacity to deliver effectively.

For FCDO

- Recommendation 4: Adopt a more flexible and coherent delivery model for fragile and conflict-affected environments, to maximise agility in dynamic contexts.

- Recommendation 5: Support the UK’s localisation commitment by increasing direct funding to local organisations, simplifying compliance procedures, fostering long-term partnerships and strengthening local leadership of humanitarian response and resilience building.

- Recommendation 6: Address the need for more targeted programming for priority gender-related challenges in Sudan, and assess how well the current mainstreaming approach is delivering results for women and girls.

- Recommendation 7: Use learning from the Sudan conflict as an opportunity to rethink and adapt UK international leadership on mobilising and coordinating the international response to major crises, given severe global funding pressures, a shifting donor landscape and rising humanitarian need.

Introduction

1.1 The Independent Commission for Aid Impact (ICAI) is undertaking this review of UK aid to Sudan in light of the scale and urgency of the crisis facing Sudan and the UK’s significant role and stated ambition in the international response. Sudan is one of the world’s largest and fastest-growing humanitarian emergencies, with over 30 million people – nearly two-thirds of the population – in need of assistance within Sudan1 and another 4 million seeking refuge across the border in neighbouring countries.2 The UK has longstanding historical ties with Sudan, together with deep country expertise and an extensive programming history. In 2024, it designated Sudan as one of three priorities for UK humanitarian aid, alongside Ukraine and Gaza.3

1.2 This review assesses the UK’s aid to Sudan between 2019 and mid-2025, and to neighbouring countries since the outbreak of large-scale conflict in Sudan in April 2023 led to a regional humanitarian crisis. It examines how well UK support – diplomatic, developmental and humanitarian – has responded to the fast-evolving situation, and whether resources have been used strategically to deliver results. The review draws lessons to inform future UK engagement in Sudan, as well as the UK’s broader approach to conflict and insecurity – especially in fragile, highly interconnected regions where conflict and insecurity spill over national borders.

1.3 The review questions guiding this report reflect commitments that the current UK government has made for its international aid and related diplomatic engagement, including in Sudan (see Table 1). These commitments include:

- a renewed ambition for responsible global leadership

- a legal duty to consider providing aid in a way which is likely to contribute to reducing gender inequality and, in humanitarian assistance, takes account of any gender-related differences in the needs of those affected by the disaster or emergency4

- a pledge to build genuine partnerships based on mutual respect

- a determination to work towards a future peace in Sudan while responding to what the Prime Minister has called “the worst humanitarian crisis in the world today”.5

These high-level commitments form the basis against which ICAI has assessed the effectiveness, impact and value for money of the UK’s approach to Sudan, with the aim of informing both current and future conflict and crisis responses.

1.4 The review assesses the UK’s aid response across three distinct periods in Sudan’s recent history, each marked by major political shifts and corresponding changes in UK approach and programming. Findings are located within these specific phases to reflect the evolving context and the UK’s adaptation over time:

- Transition (2019–21): Following the ousting of President Omar al-Bashir, Sudan embarked on a fragile shift towards democracy under a joint civilian-military transitional government.

- Coup (2021–April 2023): The Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF) and Rapid Support Forces (RSF) jointly staged a military coup in October 2021, halting the transition and seizing power.

- Conflict (April 2023 onwards): Tensions between SAF and RSF escalated into open conflict, characterised by atrocities against civilian populations and famine conditions, triggering one of the world’s largest and fastest-growing humanitarian emergencies.

| Review question | Timeframe |

|---|---|

| Has the UK demonstrated responsible global leadership through its past, present and planned efforts both in Sudan and regarding the impact on neighbouring countries? | Transition, coup, conflict |

| Has the UK acted for and with women and girls through its past, present and planned efforts both in Sudan and regarding refugee flows into neighbouring countries? | Transition, coup, conflict |

| Has the UK demonstrated genuine partnership through its past, present and planned efforts both in Sudan and regarding the impact on neighbouring countries? | Transition, coup, conflict |

| Has the UK delivered, contributed to and supported an effective humanitarian response post-April 2023 both in Sudan and regarding refugee flows into neighbouring countries? | Conflict |

1.5 The methodology involved eight components, including a strategic review of UK policies and coherence over time, a literature review aligned with the four review questions, and desk reviews of active UK aid programmes. A deep dive on famine provided focused analysis of the humanitarian and diplomatic response. The review also incorporated extensive stakeholder consultation through interviews, focus groups and expert roundtables, along with in-person visits in Kenya and Ethiopia, and virtual visits in Chad and South Sudan. A perception survey gathered views from partners and experts, while locally led research in Kenya and Uganda engaged Sudanese diaspora, refugee-led and women-led organisations. Limitations included travel restrictions and participant fatigue, which affected engagement in some research components. The methodology is set out in more detail in Annex 2.

1.6 The review faced several limitations that affected the scope and depth of evidence gathering, and in particular the ability to reach firm conclusions about the impact of UK aid to Sudan. While initial plans included in-person consultations in South Sudan and Chad, an escalation in the security situation during the data collection phase required a shift to virtual visits. Access to Sudan itself was also not possible due to security risks. Participation challenges also reduced the breadth of perspectives: a significant number of invitees to the locally led research component declined or did not respond, and signs of consultation fatigue were evident. These factors inevitably limited the review’s ability to capture the full range of experiences and views from across Sudan and the region. Finally, the review has been able to identify only limited evidence on impact. Some of the areas we have reviewed (leadership and partnership) are not usually the subject of monitoring and reporting, while UK programmes have limited resources available for tracking longer-term results in the midst of an ongoing conflict and crisis.

1.7 To help signpost for the reader, this report presents ICAI’s findings across the four review questions. The discussion of findings for each of the questions is introduced by a short description of relevant context and an overview of the UK’s evolving response. The report ends with a set of overall conclusions, followed by recommendations to enhance the impact and value for money of the UK’s engagement in Sudan and to inform future responses to complex, fast-moving, cross-border crises.

Background

2.1 This review covers the period since 2019, when Sudan entered a political transition following the ousting of President Omar al-Bashir after three decades in power. After mass protests led to his removal in April 2019, a transitional government was established, involving civilian and military leaders, to guide the country towards democracy. This fragile progress was disrupted in October 2021 when the military seized full control in a coup, dissolving the transitional government. This deepened political instability and set the stage for the violent conflict that erupted in April 2023 between the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF) and the Rapid Support Forces (RSF).

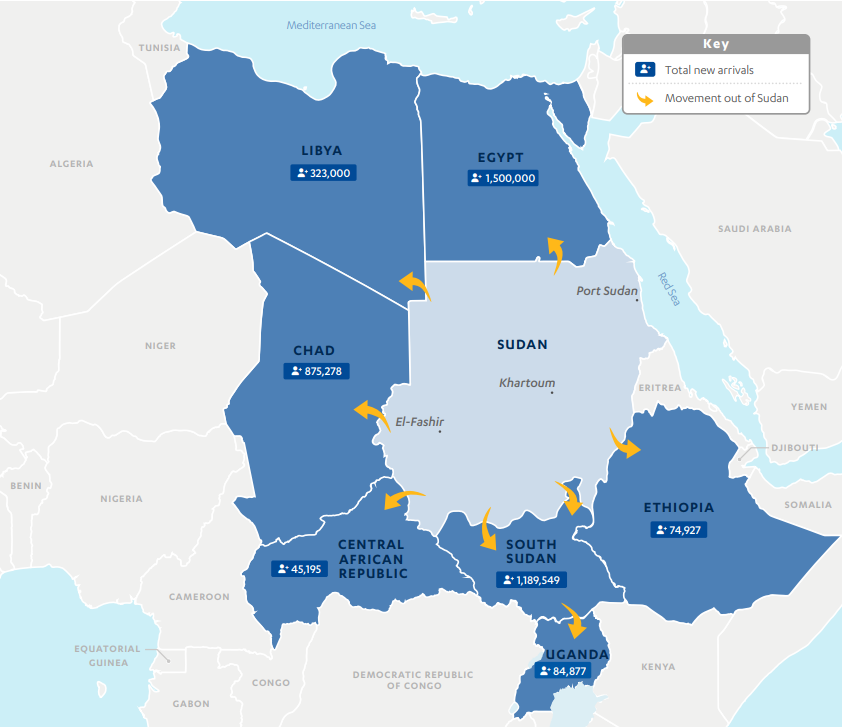

2.2 Sudan now sits at the centre of a deepening regional crisis (see Figure 1). Since large-scale conflict erupted in April 2023, over 12 million people have been displaced, including more than 4 million across borders.6 Chad, South Sudan and Egypt have seen the largest influx, together receiving more than 87% of new arrivals. Chad and South Sudan are under particular strain, as both countries have their own significant humanitarian needs. Chad hosts over 1.2 million Sudanese refugees, of whom around 875,000 have arrived since the outbreak of conflict in Sudan in April 2023.7 Almost 1.2 million people have fled to South Sudan since April 2023, of whom around 800,000 are South Sudanese refugees returning from Sudan and the rest are Sudanese refugees. In total, South Sudan is currently dealing with almost 2 million internally displaced people, 584,000 registered refugees (of whom 95% come from Sudan), 1.7 million returned refugees, and worsening humanitarian conditions for large numbers of the country’s non-displaced population.8

2.3 Inside Sudan, over 30 million people – nearly two-thirds of Sudan’s population – now require humanitarian assistance, including 16 million children.9 Women and girls are particularly vulnerable, facing heightened risks of gender-based violence, including conflict-related sexual violence. Famine conditions are confirmed in multiple locations, with 8.1 million people facing emergency food insecurity and more than 600,000 at risk of starvation.10 Health systems have collapsed in many areas, with rising deaths from disease outbreaks such as cholera and measles.11 Humanitarian access in Sudan is extremely limited, relying heavily on local networks, with few international actors able to operate across complex and rapidly shifting frontlines.

2.4 A number of states in the region and beyond have deep strategic interests in Sudan and are providing support to the warring parties, which heightens risks of escalation and complicates conflict resolution efforts.12 The conflict is also exacerbating fragility in neighbouring countries. People, weapons and smuggled natural resources flow easily across porous national borders, while disruptions to trade and rising food insecurity have regional impacts.

Figure 1: Map of population movements from Sudan into neighbouring countries since the outbreak of conflict

Source: United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, ‘Sudan Emergency: Population movements from Sudan’, 11 August 2025

Description: Map showing population movements from Sudan into neighbouring countries since the outbreak of conflict on 15 April 2023, as of August 2025. Since the outbreak of the conflict, there are 4.1 million displaced persons in neighbouring countries – 1,189,549 in South Sudan; 1,500,00 in Egypt; 875,278 in Chad; 323,000 in Libya; 84,877 in Uganda; 74,927 in Ethiopia and 45,195 in Central African Republic.

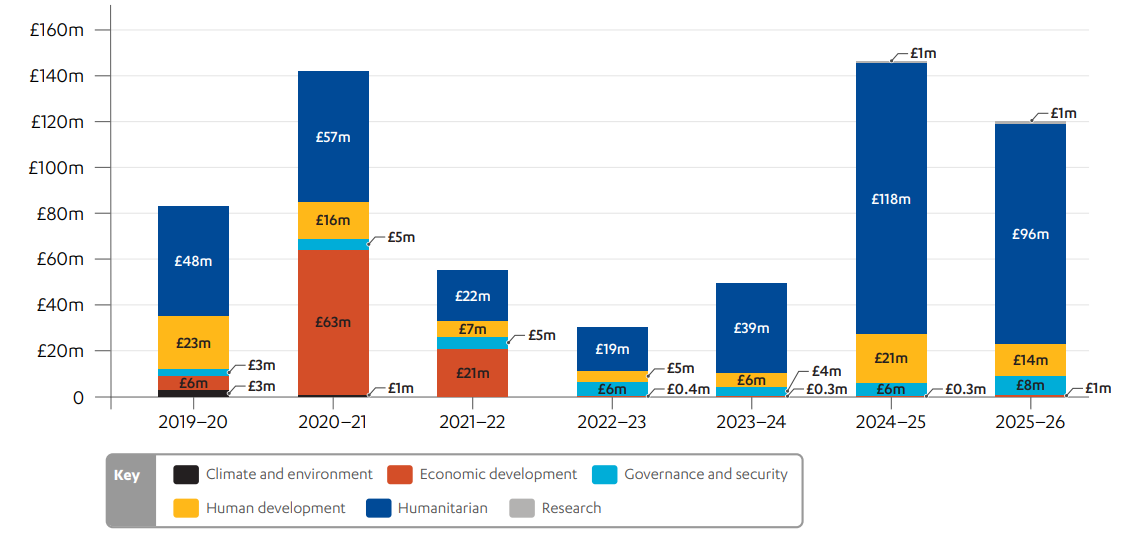

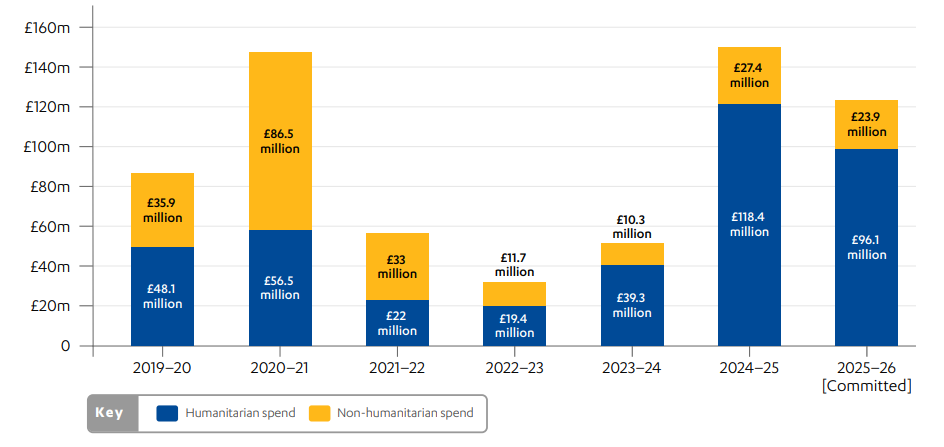

2.5 Between 2019 and 2025, the UK’s aid portfolio in Sudan has evolved markedly in scale and focus. Initially geared towards supporting Sudan’s democratic transition through diplomatic engagement, economic reform and peacebuilding, the UK pivoted towards humanitarian aid and regional stabilisation following the 2021 coup and the April 2023 outbreak of conflict (see Figure 2). By the end of 2024, the UK had become the fourth-largest donor to the Sudan crisis, after an additional £113 million pledge in November 2024 brought its total commitment to the Sudan response to £226.5 million for financial year 2024–25 (see Box 1).13 The UK has also taken on a prominent role in the coordination of the international humanitarian response, underpinned by high-level country visits and active diplomacy within the UN Security Council.

Box 1: The UK is a major donor to the Sudan crisis

By November 2024, the UK pledged an additional £113 million to the Sudan crisis, bringing its total commitment to £226.5 million for the 2024–25 period. This made the UK the fourth-largest donor to the Sudan crisis, including the response in Sudan and for Sudanese seeking refuge in neighbouring countries. This commitment was exceeded by £4.8 million, bringing the UK’s total spending on the Sudan response to £231.3 million for the 2024–25 financial year.

The humanitarian response consists of support for internally displaced people and war-affected communities within Sudan, as well as a regional refugee response that supports host countries, including Chad and South Sudan. The latter provides life-saving protection and humanitarian assistance for the over 4 million people who have fled Sudan, as well as strengthening local capacity to include refugees in national systems and services.

With nearly $1.8 billion in support in 2024, this humanitarian response reached over 15.6 million people across Sudan. Assistance included food and livelihoods support to more than 13 million people, as well as water, sanitation, health, nutrition, and shelter services.14 By 22 September 2025, a further $1.44 billion of humanitarian financing had been received, supporting efforts to tackle food insecurity, scale up protection services, restore basic services and address other acute needs – prioritising the most affected areas including Darfur, Kordofan and Khartoum.15

Figure 2: Since the outbreak of conflict in 2023, UK bilateral aid to Sudan has increasingly been allocated to support the humanitarian response

Stacked bar chart showing UK bilateral expenditure to Sudan by sector*

Source: Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office, ‘Sudan spend 2019–2025’, September 2025, unpublished

* Bilateral spend for education is not included in the chart, since it represents too small a proportion of overall spend to be visible (£6,264 in 2024–25 and £39,600 forecasted for 2025–26). Figures for 2025–2026 are forecasted.

Description: The chart shows annual UK bilateral expenditure in Sudan for financial years 2019–20 to 2024–25 disaggregated by sectors. In the last three financial years (2022–23 to 2024–25), the majority of UK official development assistance in Sudan has been on humanitarian spend, increasing from £19 million in 2022–23 to £118 million in 2024–25.

2.6 The speed, scale and complexity of Sudan’s escalating conflict has posed a major challenge for international partners such as the UK. Across the three phases covered by this review, the UK has operated in contexts that bring very different challenges (see Figure 3). During the 2019–21 transition, optimism following the ousting of President Bashir led to a wave of international support, with programming heavily focused on economic stabilisation as the pathway to democratic transition. The 2021 coup shattered this optimism, requiring rapid reorientation to a more restrictive and uncertain operating space, with international partners shifting away from direct support for government in favour of working with civil society partners and pro-democracy activists.

2.7 The outbreak of war in April 2023 marked a profound rupture, coming as a surprise even to many Sudanese observers. The UK, like other international actors, was forced to evacuate Khartoum, relocating first to the UK before establishing a renewed British Office Sudan (BOS) in Ethiopia and Kenya (see Box 2), reinforced by an upgraded Sudan Unit in London. This meant managing the evacuation of UK staff and nationals in an increasingly volatile environment. Since then, the situation has continued to deteriorate, with mass atrocities and growing famine conditions. International humanitarian actors have faced severe access restrictions, limiting their ability to mount a response at the scale required. Both the SAF and RSF, as well as other armed groups, have hindered the humanitarian response through the destruction of critical infrastructure and through bureaucratic impediments that deliberately limit humanitarian access, such as refusing or delaying the grant of travel permits for humanitarian actors.16

Box 2: British Office Sudan

British Office Sudan (BOS) was established in Addis Ababa and Nairobi following the withdrawal of the British Embassy Khartoum in April 2023. In addition to overseeing UK aid programmes in Sudan, BOS supports UK policy and advocacy related to the Sudan response, engaging with the UK mission to the UN in New York, UK-based policy and research teams, and other UK embassies in the region. The two locations also offer different platforms for coordinating with other international partners: Nairobi-based staff lead engagement with the Humanitarian Donor Working Group, as well as various UN agencies and international non-governmental organisations, while Addis Ababa is the headquarters of the African Union.

2.8 Sudan’s conflict is unfolding amid a crisis in the international humanitarian system. Demand for humanitarian assistance is at record levels – over 305 million people worldwide now need support – driven by overlapping crises including in Gaza, Ukraine, the Sahel, Yemen and the Horn of Africa.17 However, major donors, including the US, the UK and a number of other European donors, have significantly reduced their aid budgets, causing global aid flows to fall by up to 17% in 2025, with a highly uncertain outlook in future years.18 This makes for a complex backdrop to the UK’s commitment to play a leading role in the international response to one of the world’s most urgent and underfunded crises.

Figure 3: Timeline of key events in Sudan and the international response

| Key developments in Sudan | Timeline |

|---|---|

| President Bashir is removed from power, and the Transitional Military Council (TMC) is declared | 11 April 2019 |

| The TMC and Forces for Freedom of Change (FFC), a wide alliance of political parties and business associations, agree to a 39-month period of transitional government. The transitional government is to be led by an 11-member Sovereign Council composed of military leaders and civilians, and a civilian prime minister appointed by the FFC | July 2019 |

| The TMC and FFC sign a Constitutional Declaration to govern the 39-month transitional period. Abdalla Hamdok is sworn in as prime minister and General al-Burhan, leader of the Sudanese Armed Forces, is sworn in as chair of the Sovereign Council | August 2019 |

| The Sudanese transitional government and a broad alliance of armed movements sign the Juba Peace Agreement, which extends the transitional period by two years and grants the armed movements three seats in the Sovereign Council | 3 October 2021 |

| In a military coup, the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF) and Rapid Support Forces (RSF) arrest the civilian members of the Sovereign Council, including prime minister Hamdok | 25 October 2021 |

| General al-Burhan appoints a new Sovereign Council, with himself as chair and the leader of the RSF, Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo (‘Hemedti’), as his deputy | 11 November 2021 |

| A political Framework Agreement, calling for the formation of a new transitional civilian government and the launch of a comprehensive process to draft a new constitution, is signed by al-Burhan, Hemedti, and the FFC | 5 December 2022 |

| Heavy fighting breaks out between the SAF and RSF in Sudan’s capital city, Khartoum, and several other parts of the country | 15 April 2023 |

| The Sudanese Coordination of Civil Democratic Forces (Tagadom), a pro-civilian power and anti-war coalition led by former prime minister Hamdok, is founded | October 2023 |

| The RSF sign a charter with allied political and armed groups to establish a parallel government in RSF-held areas | February 2025 |

| Tagadom formally announces a split with members who support the prospective RSF-aligned government. The remaining majority rename themselves Somoud and state they remain neutral and are committed to maintaining an independent democratic path | February 2025 |

| International response | Timeline |

|---|---|

| Sudan International Partners Forum, a platform composed of a range of donors, international finance institutions, and non-governmental organisations, is established to strengthen international coordination on humanitarian, development, and peacebuilding activities in Sudan | June 2019 |

| The UN Security Council adopts resolution 2524, establishing the UN Integrated Transition Assistance Mission in Sudan (UNITAMS), a special political mission, to provide support to Sudan for an initial 12–month period during its political transition to democratic rule | 3 June 2020 |

| The UN Security Council ends the mandate of the African Union-United Nations Hybrid Operation in Darfur (UNAMID), a joint peacekeeping mission established in 2007 | 31 December 2020 |

| The World Bank determines Sudan has taken the necessary steps to begin receiving debt relief under the Heavily Indebted Poor Countries Initiative | 29 June 2021 |

| The withdrawal of all UNAMID personnel is completed. The government of Sudan assumes responsibility of the mission’s activities, including protecting civilians, facilitating humanitarian assistance, and mediating intercommunal conflicts in Darfur | 30 June 2021 |

| The Trilateral Mechanism, consisting of the African Union, the Intergovernmental Authority on Development, and UNITAMS, is established to facilitate and coordinate political dialogue | March 2022 |

| The Trilateral Mechanism facilitates a series of workshops aimed at reaching a final political agreement, including consultations on security sector reform and transitional justice | January - February 2023 |

| The Jeddah Declaration, committing to the protection of civilians, is signed by the SAF, RSF, US and Saudi Arabia | 20 May 2023 |

| The Famine Review Committee confirms famine conditions in ZamZam camp (North Darfur) and concurs with projections that this will continue to be the case and most likely deteriorate | 1 August 2023 |

| The 2025 Sudan Humanitarian Needs and Response Plan and the Regional Refugee Response Plan are launched. The humanitarian appeals ask for a combined $6 billion, almost 50% higher than the previous year, to reach almost 26 million people in Sudan and the region | February 2025 |

| The UK co-hosts the London Sudan Conference, which aims to foster international consensus on political and humanitarian priorities | 15 April 2025 |

Findings

3.1 The findings of this review are structured around the four review questions set out in Table 1, which assess the quality of the UK’s global leadership on Sudan; its efforts to support women and girls; the quality of its partnerships; and the effectiveness of its humanitarian response. Each section begins with a descriptive account setting the scene, before it presents a set of findings that assess performance against the UK’s stated objectives, drawing out key lessons for future engagement in Sudan and other complex crises.

Has the UK demonstrated responsible global leadership through its past, present and planned efforts both in Sudan and regarding the impact on neighbouring countries?

“We are returning the UK to responsible global leadership… This is the moment to reassert fundamental principles and our willingness to defend them. To recommit to the UN, to internationalism, to the rule of law.”

Prime Minister Keir Starmer, United Nations General Assembly Speech, 26 September 2024

Setting the scene

3.2 The 2023 white paper on international development set out the UK’s aspirations for responsible leadership on global challenges. It states: “The United Kingdom is uniquely placed to help address these challenges at source, using our science and technology expertise, our position as a global financial centre and our extensive diplomatic network.”19 The document outlines broad principles for the UK’s leadership approach, including building partnerships based on mutual respect, listening to and championing the needs of developing countries, modelling good behaviours, promoting global collective action, mobilising international finance, and helping strengthen and reform the international system. In the case of Sudan, the UK has pledged to use its diplomatic influence and UN Security Council membership to exert collective pressure on the warring parties to remove barriers to humanitarian action, enable accountability for atrocities, support African-led solutions through the African Union (AU), and promote inclusive dialogue on restoring civil government.20 In this section, we look at how these aspirations have shaped the UK’s response to the Sudan crisis.

3.3 After the ousting of President Omar al-Bashir (2019–21), UK aid and diplomatic engagement were directed towards supporting a successful democratic transition. This included playing an active role in international coordination platforms and funding a range of economic and governance reforms (see Boxes 3 and 4). The UK also worked to align diplomatic messaging with other international actors through platforms such as the Troika, Quad and the Juba Peace Agreement, to facilitate the formation of multilateral groups such as the Friends of Sudan (see Box 5), and secure passage of the June 2020 Security Council resolution establishing the UN Integrated Transition Assistance Mission in Sudan (UNITAMS) political mission.

Box 3: UK support to economic resilience through the World Bank Sudan Transition and Recovery Support (STARS) Trust Fund

UK support for Sudan’s economic development in the transition period was primarily in the form of an £80 million contribution to a $1 billion World Bank-managed multi-donor trust fund. The UK contribution funded cash transfers to 3.2 million Sudanese civilians through the Sudan Family Support Programme (SFSP), to mitigate the adverse impacts of macroeconomic reforms on poor households. The SFSP delivered $100 million in cash transfers before the programme was halted following the 2021 coup, leaving $443 million in unspent donor contributions and $354 million in unspent World Bank funds.

In May 2022, in response to escalating humanitarian need and a lack of progress in restoring civilian government, the trust fund donors agreed to repurpose $100 million in unspent funds for an emergency cash and food transfer programme implemented by the World Food Programme, which eventually supported 2.4 million people.

Following the outbreak of conflict in April 2023, the trust fund pivoted once again, launching a new programme, Somoud, which became active in mid-2024. The Somoud programme has funded basic services, prioritising urban and peri-urban areas with high inflows of internally displaced people (IDPs). Reported results include establishing 90 primary health centres, the provision of essential medical and nutrition supplies, and distributing ‘school-in-a-box’ kits, which facilitate the rapid establishment of temporary learning centres in crisis settings. To enhance food security, the programme has supported 84 farmer cooperatives, with expected increases in yields that will meet the food needs of approximately 250,000 people. It has also launched a matching grant programme aiming to support 80 small and medium-sized enterprises in agricultural value chains.

Source: Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office, ‘Sudan Economic Impact and Reform Programme Annual Review 2024’, May 2025

Box 4: Unlocking debt relief: the UK’s role in Sudan’s HIPC milestone

The UK helped Sudan regain access to support from international financial institutions under the

Heavily Indebted Poor Countries (HIPC) Initiative. HIPC is an international process that allows the world’s poorest and most indebted countries to qualify for debt relief once they meet specific reform and economic management conditions.

The UK provided diplomatic and technical support to Sudan’s transitional government, including efforts to clear arrears at the World Bank and African Development Bank, mobilise donor backing and coordinate with international financial institutions. Sudan progressed through the early stages of the HIPC process at record speed – within about two years of its transition – unlocking initial access to concessional finance and laying the groundwork for economic recovery. However, this process was interrupted by the coup. Further steps will be required to reactivate debt relief and enable Sudan to benefit from concessional finance once stability returns.

Box 5: The UK’s participation in international platforms: Troika, the Quad and Friends of Sudan

The Troika is an informal diplomatic grouping of the UK, the US and Norway, which has been central to the diplomatic work to support peace, democratic transition and conflict resolution efforts in Sudan since the early 2000s.

The Quad is a diplomatic grouping originally comprising the UK, the US, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates, formed to coordinate international efforts in supporting Sudan’s political transition and resolving its ongoing conflict. By 2025, the Quad had evolved to become the US, Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates and Egypt.

The Friends of Sudan consists of Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Saudi Arabia, the Netherlands, Norway, Spain, Sweden, the United Arab Emirates, the UK, the US and the European Union. It works to support Sudan’s civilian-led political transition, back multilateral mediation efforts and coordinate diplomatic and financial support.

3.4 In October 2021, Sudan’s military forces seized power in a coup, dissolving the transitional government and halting progress towards civilian rule. The UK condemned the military takeover and shifted its approach towards backing the political process jointly facilitated by the UN, the AU and the regional Intergovernmental Authority on Development (IGAD), aimed at restoring a civilian-led transition. The UK continued its engagement with non-government actors, while promoting international human rights monitoring mechanisms to ensure accountability during this period.

3.5 Conflict erupted in 2023 between the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF) and the Rapid Support Forces (RSF) – a paramilitary group formerly aligned with the army. What began as a power struggle between rival generals quickly escalated into a full-scale civil war, devastating communities and displacing millions. At this point, the UK approach included using its role as ‘penholder’ (see Box 8) on the Sudan conflict and crisis in the UN Security Council, sanctions on warring parties and high-level diplomacy, while adapting its aid portfolio to support the humanitarian response in Sudan and neighbouring countries.

Figure 4: Timeline of selected diplomatic events, and the UK’s role in these, related to Sudan 2020–25

| UK diplomatic efforts | Timeline |

|---|---|

| The UK and Troika partners sign as witnesses to the Juba Peace Agreement | October 2020 |

| UK efforts help secure Sudan’s clearance of arrears to the IDA, enabling its full re-engagement with the World Bank Group after nearly three decades | March 2021 |

| The first meeting of the re-launched UK-Sudan Strategic Dialogue takes place in Khartoum, aiming to refresh bilateral engagement and discuss areas of cooperation, including UK support to economic reform and transitional government institutions | October 2021 |

| The UK leads a UNHRC special session on the situation in Sudan and helps secure a resolution appointing a UN expert to further monitor the human rights situation following the military coup | November 2021 |

| The Troika and the Quad issue a joint statement endorsing the Trilateral Mechanism’s role in facilitating negotiations to restore a transitional civilian government | December 2022 |

| The Troika and EU envoy’s statement reaffirms support for African leadership in the peace process, including the AU's Roadmap for the Resolution of the Conflict in Sudan | May 2023 |

| The UNHRC adopts a UK-led resolution to establish an independent fact-finding mission for Sudan | October 2023 |

| The UNSC adopts a UK-penned resolution calling for a ceasefire during Ramadan and a renewed mandate of the UN Panel of Experts on Sudan | March 2024 |

| The UNSC adopts a UK-penned resolution calling for de-escalation in El Fasher and cross-border aid delivery, and requesting the UN Secretary-General make further recommendations for the protection of civilians | June 2024 |

| The UK and Sierra Leone co-penned UNSC resolution to advance measures for the protection of civilians in Sudan is vetoed by Russia | November 2024 |

| The UK co-hosts the London Sudan Conference which aims to foster international consensus on political and humanitarian priorities | April 2025 |

| UK Official Development Assistance (ODA) | Timeline |

|---|---|

| The UK minister for Africa pledges £80 million for the Sudan Family Support Programme at the Sudan Partnership Conference | June 2020 |

| Announcement of UK ODA budget reduction from 0.7% of Gross National Income to 0.5% | November 2020 |

| Sudan’s clearance of arrears to the African Development Bank is supported by a UK bridging loan of £330 million | May 2021 |

| British Embassy Khartoum establishes a set of principles to guide the pivoting of UK ODA programming in Sudan post-coup, including ceasing all support to the de facto authorities | October 2021 |

| UK ODA spending pause | July – November 2022 |

| Engaging closely with implementing partners, the UK rapidly pivots ODA programming in Sudan to deliver in the crisis context following the outbreak of conflict in April 2023 | May 2023 |

| The UK announces a £113 million package for Sudan and neighbouring countries, doubling aid in response to the conflict to £227 million | November 2024 |

| Announcement of UK ODA budget reduction from 0.5% of Gross National Income to 0.3% | February 2025 |

Key findings

The UK has shown credible political leadership and strong convening power on Sudan, but its impact has been constrained by inconsistent political attention

3.6 The review finds that, during the early transition period (2019–21), the UK exercised strong political leadership and convening power on development assistance and diplomatic engagement. It played a leading role in donor coordination platforms and political forums, including the Troika and Quad, and supported the Juba Peace Agreement. These efforts helped align international actors behind the transition. UK engagement with the World Bank helped shape international support for economic reform and stabilisation. Coupled with a bridging loan of £330 million via the African Development Bank, it helped Sudan achieve a key milestone in the international debt clearance process (HIPC – see Box 4) in a record time of around 18 months, compared to an average of 4–7 years – a strong example of the influence the UK can wield by working through multilateral channels.

3.7 After the October 2021 coup, UK ministerial attention to Sudan diminished. The coup brought to an end the civilian-led transition that had been the focus of engagement, leaving the UK with limited diplomatic leverage and fewer options for support. This was compounded by competing global crises, including the August 2021 fall of Kabul in Afghanistan and the Russian invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, which drew senior attention elsewhere, and the UK’s COVID-19-related aid budget reductions, which forced difficult reprioritisation decisions. Institutional disruptions, including the merger of the Department for International Development and the Foreign and Commonwealth Office in 2020, also drew ministerial attention away from events in Sudan. During this period, UK influence was sustained more through in-country political leadership, as well as technical participation in international forums and continued support for a civilian transition, rather than through visible ministerial leadership.

3.8 Since the outbreak of full-scale conflict in April 2023, the UK has played a more active leadership role through high-profile engagement by ministers, senior officials and dignitaries. Visits to the Chad-Sudan border by the Duchess of Edinburgh, the former Foreign Secretary and the Minister for Development helped raise international awareness of the conflict and its humanitarian toll and were highly valued by stakeholders. The UK’s support for AU co-chairmanship at the April 2025 London Sudan conference (see Box 6) was also well received by the AU and aligned with the UK’s stated commitment to African-led solutions.

Box 6: The UK as a convenor: the April 2025 London Sudan Conference

The London Sudan Conference, held on 15 April 2025 at Lancaster House, was co-hosted by the UK, Germany, France, the African Union and the European Union. The conference brought together foreign ministers and key international stakeholders to reaffirm shared commitments to pursuing a ceasefire, protecting civilians, humanitarian relief and support for a civilian-led peace process.

3.9 The UK has continued to pursue active leadership at country level. In Sudan, it plays a prominent role among donors in the Heads of Mission group and co-chairs both the Core Donor Working Group and the Humanitarian Donor Working Group. It has continued with longstanding leadership roles in South Sudan and taken up new positions of influence in Chad, including as chair of the Chad Climate Working Group. Sudanese stakeholders interviewed for this review consistently emphasised the value of the UK’s deep networks and longstanding support for a civilian-led transition.

3.10 However, there are also some limitations in the UK’s influencing efforts towards sustainable peace. While the UK continues to engage a range of partners, including Gulf countries such as the United Arab Emirates and Saudi Arabia, in interviews, Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO) staff stated that, as with all UK diplomatic engagement, their approach had to accommodate wider foreign policy considerations, such as commercial relationships, regional security cooperation and other bilateral interests. This and broader geopolitical considerations have constrained the UK’s political stance in a region that is central to Sudan’s political trajectory and a sustainable peace.

3.11 On contentious issues such as violations of international humanitarian law21 and the use of famine as a weapon of war,22 the UK has supported international accountability processes, including evidence collection for the International Criminal Court and the UN Human Rights Council’s fact-finding mission. However, these international initiatives are yet to yield any change in the behaviour of perpetrators. This review encountered perceptions of international inaction, including by the UK, both on atrocities and in relation to improving humanitarian access to populations most affected by the conflict. Given the complexity and political sensitivities around these issues in Sudan, there are no easy choices for the UK. However, it could review a range of options – including stronger public messaging, more visible support for accountability mechanisms, and integrating atrocity prevention in conflict analysis and programming decisions – to assess if it might be possible to do and achieve more.

Cross-government collaboration on Sudan is underdeveloped, affecting strategic coherence on key cross-cutting issues

3.12 UK cross-government collaboration on Sudan has varied by department and over time. During the transition period (2019–21), the Defence section at the Embassy enabled regular engagement with Sudanese authorities. However, the section closed in autumn 2022. This limited involvement from the UK Ministry of Defence restricted the UK’s ability to influence discussions on security sector reform – a central issue at the time. The lack of a sustained defence attaché presence in-country also curtailed access to key officials in the SAF and RSF, diminishing UK influence on security and access matters.

3.13 FCDO has acknowledged that its analysis in the transition phase (2019–21) period was shaped by a bias towards optimistic narratives, largely because it did not consistently invite more dissenting or critical perspectives. ICAI concurs that – taking the benefit of hindsight – there was an overemphasis on governance and economic stabilisation priorities in UK programming, including macroeconomic policy reform, without adequately interrogating the links between economic incentives and conflict dynamics, or fully recognising the threat Sudan’s entrenched political and military elites posed to long-term stability. A more risk-aware strategy may have allowed the UK to identify more ways to alleviate the pressure on a fragile political process.

3.14 Even in the current conflict period (April 2023 onwards), despite Sudan’s designation as a UK foreign policy priority, there are opportunities to increase cross-departmental coordination. Defence and migration portfolios in particular have been largely peripheral, including on efforts to align international messages around peace. The Home Office has only recently shown greater engagement on Sudan, driven in part by rising numbers of Sudanese arrivals via small boat crossings, even though it has been likely for some time that the conflict would affect migration flows into Europe and towards the UK. However, this has not translated into sustained interdepartmental collaboration in strategic planning on the UK’s response to the conflict, although the government tells us that there is an FCDO and Home Office commitment to develop a Sudan/regional migration strategy by March 2026.

3.15 A formal National Security Council-style process (see Box 7) may not be necessary, but without more deliberate coordination and engagement across departments, the UK is at risk of missing opportunities for effective engagement in a complex and rapidly evolving situation.

Box 7: The National Security Council

The UK National Security Council is a Cabinet committee chaired by the Prime Minister. It brings together senior ministers and officials, such as the Foreign Secretary, Defence Secretary, Home Secretary, and heads of intelligence and defence services, to promote strategic alignment across departments on issues including national security, foreign policy and defence.

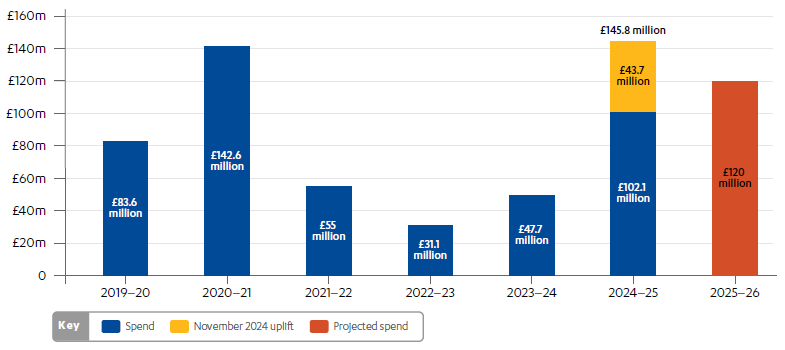

Volatility and uncertainty in UK aid to Sudan has undermined trust and hampered forward planning

3.16 UK aid to Sudan has fluctuated significantly over the review period (see Figure 5). The reduction in the UK aid budget to 0.5% of gross national income (GNI) in 2021 led to sharp reductions to the Sudan budget, with further pauses and reductions in 2022. The Sudan budget was reduced during the course of 2022–23 by 40%, from a planned £51.7 million to £31 million. As a consequence, some planned activities within programmes were postponed, and a water, sanitation and hygiene programme was closed early. According to an unpublished FCDO equalities and inclusion assessment of the budget reductions, these measures were implemented in a way that prioritised high-performing programmes and protected those most in need within Sudan.23 They nonetheless resulted in significant reductions in the numbers of people reached by UK humanitarian support, as well as delays in support to women-led organisations at a key moment in peace negotiations.

3.17 This volatility in UK support has eroded partner trust in the UK’s ability to sustain a leadership role, limited scope for forward planning and disrupted programming – particularly for larger initiatives such as the Sudan Free of Female Genital Mutilation (SFFGM) programme and the Sudan Stability and Growth Programme (SSGP). As Figure 5 shows, the Sudan allocation had fallen by 75% in the two years leading up to the outbreak of conflict. As one UK official interviewed for this review put it, “we went from big spend a few years before, to a crash at a time when the country needed it”.

Figure 5: Total bilateral aid to Sudan, from 2019–20 to 2025–26

Column chart showing UK bilateral official development assistance in Sudan (not including funding for the regional humanitarian crisis caused by the Sudan conflict in neighbouring countries) since 2019–20, with figures for projected rather than actual spend in 2025–26.

Source: Compiled from Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office, ‘FCDO Annual Report and Accounts 2019–2020’; ‘FCDO Annual Report and Accounts 2020–2021’,September 2021; ‘FCDO Annual Report and Accounts 2021–2022’, July 2022; ‘FCDO Annual Report and Accounts 2022–2023’, July 2023; ‘FCDO Annual Report and Accounts 2023–2024’, July 2024 and ‘FCDO Annual Report and Accounts 2024–2025’, July 2025; and 2025–26 data supplied to ICAI by FCDO

Description: The chart shows UK aid spend and funding uplifts (where applicable) to Sudan, for financial years 2019–20 to 2025–26. The columns show actual spend for all years apart from the 2025–26 column, which shows projected spend. Following UK budget reductions in 2021, spending reduced significantly from £142.6 million in 2020–21 to £55 million in 2021–22. Spending then increased from £31.1 million in 2022–23 to £145.8 million in 2024–25, following a £43.7 million funding uplift in November 2024. Projected spending for 2025–26 is £120 million.

3.18 These reductions also weakened the UK’s visibility and credibility in key multilateral forums. At moments when international attention and coordination were critical, especially following the outbreak of conflict in April 2023, the UK lacked senior representation at major pledging conferences and other diplomatic platforms such as the Sudan Pledging Conference in June 2023, diminishing its influence over the international aid response.

3.19 However, after designating Sudan as one of three priority countries for UK humanitarian aid in mid-2024, the UK significantly increased its financial commitment up to a projected spend of £120 million in Sudan in financial year 2025–26, re-establishing itself as a prominent donor. This has in turn helped reinforce UK diplomatic influence. Alongside continuing leadership roles, such as serving as UN Security Council ‘penholder’ on Sudan (see Box 8), the UK is also a member of major donor groups, such as the Sudan Humanitarian Fund Advisory Board, and co-chair of both the Core Donor and Humanitarian Donor Working Groups. There was also a funding uplift for the regional response to the Sudan humanitarian crisis. In Chad and South Sudan, this renewed aid investment has strengthened the UK’s voice in strategic and humanitarian coordination.

Box 8: The UK as Security Council ‘penholder’ on Sudan

Within the UN Security Council, one or more member countries (typically one of the three Western permanent members, France, the UK and the US) acts as ‘penholder’ for particular countries or issues, leading on the preparation of resolutions, statements and other documents. As the ‘penholder’ on Sudan since 2019, the UK has a platform for building consensus among members and influencing Security Council action. The UK is also ‘penholder’ for a range of other countries, including Somalia and Yemen, and for thematic issues such as the UN Women, Peace and Security agenda.

3.20 However, this review found that partners remain concerned about the UK’s reliability as a funding partner. Despite the designation of Sudan as a priority country, the government’s February 2025 decision to reduce overall aid to 0.3% of GNI by 2027 has left a perception of uncertainty among Sudanese stakeholders. Ongoing unpredictability, coupled with the fact that increased funding often comes from late uplifts, such as the announcement in November 2024, hampers planning and risks undermining long-term resilience programming.24

Early leadership in the transition period was underpinned by strategic foresight and timely support, but delays in programme approvals and delivery undermined impact

3.21 During the transition period (2019–21), the UK demonstrated clear strategic foresight. Together with UK work on HIPC (see Box 4), pre-planning enabled the UK to become the first bilateral donor to support Sudan’s transitional government, with early governance programming responding quickly to emerging political opportunities. Programme reporting shows that these efforts delivered visible results, including increasing women’s participation in the Juba peace talks, coalition building in Darfur and Blue Nile, and capacity building for grassroots peace efforts. This reinforced the UK’s credibility at a critical moment, particularly as other donors held off engaging.

3.22 The Sudan Humanitarian Preparedness and Response (SHPR) programme, the UK’s principal humanitarian vehicle in Sudan, also displayed significant agility. Its flexible structure enabled rapid pivots in response to the humanitarian fallout of the April 2023 outbreak of conflict, including scaling up food security support and diversifying partnerships by reallocating funds towards international non-governmental organisations (INGOs) with coverage in important areas when access constraints increased.

3.23 The governance and humanitarian programmes were grounded in ongoing political analysis and maintained delivery despite a deteriorating operating environment. This underscores the value of adaptable programming in fragile and fast-moving contexts.

3.24 However, while existing programmes demonstrated ability to adapt to changing contexts, internal processes for approving new programmes have often constrained the flexibility of the UK response. Lengthy business case approvals and complex internal clearance procedures – both within FCDO and between FCDO and HM Treasury – have delayed implementation during critical windows. In 2022, for instance, a key humanitarian business case was reportedly “stuck with Treasury” during a period of heightened need. This coincided with a pause in official development assistance (ODA) spend while the impact of budget reductions was being worked out. Such delays have undermined the UK’s agility and limited its ability to respond in real time to shifting dynamics on the ground. While tools such as the Internal Risk Facility contingency funds25 have since helped humanitarian teams manage peaks in need, stakeholders consistently noted that the UK’s internal systems are not well adapted to the demands of such a fast-moving context.

The UK maintains a strong and constructive engagement in South Sudan and Chad, where its effective partnerships support donor coordination and help attract other funding

3.25 In South Sudan, the UK serves as a collaborative and influential lead donor, supported by a well-staffed embassy and an active role in donor coordination. This has helped promote strategic alignment and effective implementation across the international humanitarian response. In Chad, while operating with very limited staffing in a new and small embassy, the UK has nonetheless also played a leadership role in donor coordination, with support from the FCDO regional office in Dakar. However, as funding pressures intensify and humanitarian strategies evolve, deeper operational coordination among donors will be essential to sustain impact across the region (see para 3.97).

The UK’s response is not fully adapted to the cross-border nature of the Sudan conflict and humanitarian crisis, limiting its ability to address regional spillover effects

3.26 The current crisis has exposed critical interdependencies between conflict and fragility in Sudan and its neighbours (see Box 9), including flows of small arms, disrupted trade corridors and regional economic shocks. These cross-border or ‘spillover’ effects are not systematically reflected in UK strategy or programming, which is organised primarily at country level. While there is informal coordination and information sharing between FCDO staff in Sudan and neighbouring countries, there is no overarching approach to align the UK’s diplomatic, humanitarian and development responses across borders.

3.27 A more deliberate regional approach would strengthen coordination between UK country-led priorities, policy and programming, ensuring attention to Sudan-related impacts as well as to existing country-specific priorities in already fragile contexts. It is essential that focus on the Sudan crisis does not lead to neglect of other important humanitarian and conflict/fragility issues in the region. In Chad, the Sudanese refugee response has drawn attention and funding away from other crises in the Sahel region (see Box 9).

3.28 While FCDO does not view a shared regional aid budget as the right solution, adequate financing for spillover effects remains essential. Top-up UK aid allocations to Chad and South Sudan have helped, but without a more deliberate regional approach, the UK risks reinforcing siloed, border-bound interventions, diminishing its ability to mitigate the wider destabilising impacts of the Sudan conflict.

Box 9: Regional interdependencies of the Sudan conflict: focus on South Sudan and Chad

The Sudan conflict has had spillover effects on neighbouring countries, particularly South Sudan and Chad, exacerbating existing humanitarian and political fragilities. Both countries have received large numbers of people fleeing the conflict – since April 2023, there are around 875,000 newly arrived refugees in Chad and more than 1.2 million newly arrived returnees and refugees in South Sudan. In both countries, these arrivals come in addition to existing displaced populations and widespread humanitarian needs, and have placed additional pressure on already overstretched services and infrastructure. These movements intersect with longstanding conflict dynamics, border tensions and resource competition, heightening instability.

In Chad, where communities host large numbers of Sudanese refugees, including both the new arrivals since April 2023 and more than 300,000 Sudanese refugees who fled previous outbreaks of conflict in their home country, pressure on land, livelihoods and basic services is intensifying. Meanwhile, in South Sudan, the influx of returnees and refugees is straining a humanitarian system already facing severe funding shortfalls and climate-related shocks.

Regional fallout and interdependencies are not only humanitarian, but also political and economic. Both Chad and South Sudan maintain complex relationships with actors in Sudan’s conflict and are affected by crossborder trade, arms flows and political alliances. The UK’s response to Sudan must therefore be grounded in a regional lens that balances support for Sudanese refugees with ongoing commitments to host communities. This includes working with local authorities to preserve social cohesion and prevent destabilisation, aligning humanitarian and development strategies to avoid creating imbalances, and ensuring that country-specific priorities are not overshadowed by regional crisis response. Without such a joined-up approach, there is a risk that efforts to support Sudanese populations could inadvertently undermine stability in neighbouring states.

Has the UK acted for and with women and girls through its past, present and planned efforts both in Sudan and regarding refugee flows into neighbouring countries?

“Overwhelmingly, what I’ve seen here in Chad, on the border with Sudan, are women and children fleeing for their lives – telling stories of widespread slaughter, mutilation, burning, sexual violence against them, their children.”

Foreign Secretary David Lammy, reported by the BBC, 25 January 2025

Setting the scene

3.29 Under the International Development (Gender Equality) Act 2014, UK development and humanitarian assistance should be delivered in ways that promote gender equality. The Act requires that, before allocating ODA, the Secretary of State must consider doing so in ways that contribute to reducing gender inequality and that take into account gender-related differences in needs. This duty applies not only to long-term development programming but also to emergency and humanitarian responses.

3.30 The International Women and Girls Strategy (2023–2030) sets out three priorities for the UK in support of women and girls internationally: educating girls; empowering women and girls, including through health and rights; and ending gender-based violence (GBV). It is guided by five principles: standing up for women’s and girls’ rights; supporting grassroots women’s rights organisations and movements; targeting investment across life stages; acting in crises; and strengthening systems. It commits FCDO to ensuring that at least 80% of its bilateral aid programmes will include a focus on gender equality by 2030 (a reference to the ‘gender marker’ system used in international aid statistics – see Box 10), and to developing UK expertise through a centre of excellence and other knowledge resources.

3.31 The status of the International Women and Girls Strategy is unclear after the 2024 UK election, as the current government has not listed support for women and girls among its stated priorities for international development. Nonetheless, there remain commitments on gender in FCDO’s Programme Operating Framework, which sets out rules and principles governing FCDO programming, and FCDO has informed us that there will be a refresh of the International Women and Girls Strategy in late 2025. Programme teams must assess the impact of aid programmes on gender equalities at each stage of the programme cycle, including selection, design, implementation, and monitoring and evaluation, while business cases are required to assess options for supporting gender equality in programme design and delivery.

Box 10: The gender equality marker system

The Development Assistance Committee of the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD-DAC) is a forum where donor countries agree the standards for international aid statistics. In 1997 it introduced a Gender Equality Policy Marker, to help donor countries monitor and report on their efforts to address gender equality through their development finance.

Donors can score their aid programmes using a three-point system, as follows:

- (Not targeted): Gender equality is not a policy objective

- 1 (Significant objective): Gender equality is an important and explicit objective, but not the main reason for the intervention

- 2 (Principal objective): Gender equality is the primarily goal.

If scored 1 or 2, a programme is considered to be gender equality-focused. The commitment in the UK’s International Women and Girls Strategy is that 80% of FCDO bilateral programmes (by number) will be scored as gender equality-focused by 2030. The most recent international aid statistics from OECD-DAC show that 63.9% of the UK’s total bilateral allocable aid in 2023 was scored as 1 (55.2%) or 2 (8.7%), while 25.3% was rated 0, and 10.8% not screened against the gender equality marker. Looking at Sudan only, the share of gender equality-focused programming is higher: 91.2% of all UK bilateral allocable aid to Sudan was scored as 1 (77.9%) or 2 (13.3%) in 2023.26

Globally, the vast majority of gender equality-focused programmes are scored as significant, rather than principal. In 2023, OECD data show $9.5 billion ODA scored as principal, with a further $99.1 billion scored as significant.27 However, the global data are not fully reliable. Independent reviews of how different donors apply the OECD-DAC gender equality marker, undertaken by Oxfam28 and the Overseas Development Institute,29 show gaps and inconsistencies in reporting practice. Not all donors systematically screen all programmes against the marker, and programmes are not always accurately labelled, particularly those in the ‘significant’ category.30 While the UK screens most of its aid against the gender equality marker and has internal guidance in place to ensure that the marker is correctly applied, it also has issues with accuracies in its scoring. The gender equality marker data provides a useful indication of progress, but other analysis is needed in order to judge the extent to which gender equality is effectively mainstreamed across a portfolio.

3.32 The inequalities facing Sudanese women and girls are immense, especially in times of conflict. Entrenched social norms severely restrict Sudanese women’s mobility, access to education and participation in decision making. Female genital mutilation (FGM) is deeply embedded in cultural and social norms, with more than 86% of Sudanese women and girls affected.31 The drivers behind the practice include patriarchal gender stereotypes and the belief that the practice protects girls’ social status and marriage prospects. Although prevalence was slowly declining before the April 2023 conflict, many stakeholders we consulted noted that weaknesses in law enforcement and the increased vulnerabilities of communities in conflict-affected areas and in displacement mean that the risks facing girls are once more on the rise.