UK aid under pressure: a synthesis of ICAI findings from 2019 to 2023

Acronyms

| Acronym | Definition |

|---|---|

| ANP | Afghanistan National Police |

| BII | British International Investment |

| CAAs | Central Assurance Assessments |

| CEPI | Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations |

| COP26 | The 2021 United Nations Climate Change Conference |

| COVAX | COVID-19 Vaccines Global Access initiative |

| CRSV | Conflict related sexual violence |

| CSOs | Civil society organisations |

| DAC | OECD Development Assistance Committee |

| DFID | Department for International Development (merged with the Foreign and Commonwealth Office in September 2020) |

| DHSC | Department of Health and Social Care |

| EU | European Union |

| FCDO | Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office |

| FCO | Foreign and Commonwealth Office (merged with the Department for International Development in September 2020) |

| GCRF | Global Challenges Research Fund |

| GNI | Gross national income |

| IDA | World Bank’s International Development Association |

| IDS | International Development Strategy |

| IFU | International Forests Unit |

| IPA | Infrastructure and Projects Authority |

| LGBT+ | Lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender/transsexual people |

| MOD | Ministry of Defence |

| NGOs | Non-governmental organisations |

| OBR | Office for Budget Responsibility |

| ODA | Official development assistance |

| OECD | Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development |

| PSVI | Preventing Sexual Violence in Conflict |

| PrOF | Programme Operating Framework |

| SEA | Sexual exploitation and abuse |

| SEAH | Sexual exploitation and abuse and sexual harassment |

| SDGs | UN Sustainable Development Goals |

| UN | United Nations |

| UNFPA | United Nations Population Fund |

| UNICEF | United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund |

| WASH | Water, sanitation and hygiene |

Foreword

This report was meant to mark the end of the third ICAI Commission, bringing together the main findings and themes from all our work since July 2019. However, it has just been announced that this Board of Commissioners will be extended until the end of June 2024, so we are starting to plan more reviews. Nevertheless, this is a good moment for us to set out our overarching findings as the UK government is preparing a new white paper on international development, and other political parties are reviewing their development policies.

Our reviews have something to offer in relation to the white paper ambitions, whether at the global level on the linked challenges of development, nature and climate, or at the ground level on the deeply practical answers to ‘what works’ or does not work in preventing fraud affecting the aid programme. The government’s call for evidence mentions the “difficult lessons” of the last few years, and ICAI has reviewed and reported on many of these, as with the lessons from Afghanistan on statebuilding or lessons on respectful partnership with developing countries and multilateral organisations. Above all, in consultation with the people in poverty affected by UK aid, ICAI has promoted the importance of integrating their perspective if aid is to ‘work’.

This synthesis of our findings also pulls together the evidence from our reviews providing “difficult lessons” on the performance of UK aid in the last few years: the disruption and losses from the merger of DFID and FCO and the damage to the UK’s reputation from the succession of budget reductions, a reduced emphasis on targeting aid to assist those in greatest poverty and therefore on the overarching Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) of “leaving no one behind”, and the diversion of aid towards hosting refugees in the UK.

At the same time, it notes from ICAI’s assessments a positive overall picture of the UK contribution to many of the SDGs since 2015 and proposes the key points on which to focus to rebuild UK aid for the future. In the months to come, ICAI will continue its work on some of the key themes of this Commission, with reviews focusing on climate action and on overall management of the aid budget in volatile times, while also picking up SDGs not so far covered, such as SDG 11 on sustainable cities and communities. ICAI too has been subject to quite a bit of turbulence during this Commission including a period when our continuing existence appeared to be in doubt, but the current Board remains firmly focused on ensuring that scrutiny continues seamlessly to help provide both accountability and learning for UK aid.

Dr Tamsyn Barton, Chief Commissioner

Sir Hugh Bayley, Commissioner

Tarek Rouchdy, Commissioner

1. Introduction

1.1 The third Commission of ICAI, which began in July 2019, has coincided with an exceptionally challenging period for UK aid. There were emergency responses to a series of global crises, including the COVID-19 pandemic, the Taliban takeover of Afghanistan and the Ukraine war. The UK aid architecture underwent radical reorganisation with the September 2020 merger of the Department for International Development (DFID) and the Foreign and Commonwealth Office (FCO), ending 26 years of separate development and foreign ministries. The UK aid programme was also subjected to a series of drastic and highly disruptive budget reductions, as well as an extended period of budgetary uncertainty. There were also frequent changes in ministers and government priorities.

1.2 This synthesis review gives an overview of the state of UK aid. Drawing on findings from ICAI’s 17 full reviews, ten rapid reviews, seven information notes and four follow-up reviews (see the list in Annex 1), and supplemented by additional interviews and documentary analysis, the review looks at the impact of the merger and budget reductions on the UK’s capacity as a development partner, and examines the expenditure patterns and strategic shifts that have emerged.

1.3 The review also summarises ICAI’s findings on the achievements of UK aid over the period from 2019 to 2023. Despite the many pressures on the aid programme, UK aid has continued to make an important contribution to international development and global crisis response. The majority of ICAI’s reviews have awarded positive scores for its effectiveness. Most of these scores reflect achievements over a longer period, and some recent reviews have questioned whether the UK is still in a position to offer the same quality of development assistance. Nonetheless, the positive achievements are an important reminder of the value UK aid can bring and the strong traditions on which it draws.

1.4 The review concludes by looking ahead, setting out key elements that will need to be addressed as part of rebuilding the aid programme in a complex and dynamic global context.

1.5 In preparing this synthesis review, we have:

- analysed patterns of findings across ICAI’s reports published between August 2019 and August 2023

- reviewed literature setting out external views on the state of UK aid

- reviewed key UK government documents, strategies and speeches from 2019 onwards that have shaped the strategic direction of UK aid

- consulted with a wide range of stakeholders from government, academia, think tanks, commercial suppliers and civil society, through a series of roundtable discussions

- conducted four focus groups with Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO) staff to learn about their perspectives on the impact of the departmental merger and UK aid budget reductions.

2. The state of the UK aid programme

A turbulent context

2.1 The 2019-23 period covered by this review has been one of extraordinary turbulence for the UK aid programme, both globally and within the UK government. The UK’s withdrawal from the European Union (EU) on 31 January 2020 was the first of many challenges. Many UK aid officials were redeployed to support Operation Yellowhammer, the government’s contingency planning for a ‘no-deal Brexit’. This led to a range of development activities being deprioritised, including the UK’s engagement with United Nations (UN) agencies on humanitarian crises. Initiatives requiring cooperation across DFID teams or government departments were particularly vulnerable to disruption.

2.2 The domestic political context was volatile. The 2019 general election was followed by a series of changes in prime minister and secretaries of state for foreign affairs and later international development, leading to frequent shifts in priorities. The government instituted annual spending reviews in 2019 and 2020, instead of the usual two-to-three-year budget cycle, making forward planning for the aid programme more difficult. Despite significant realignment in UK foreign policy after Brexit, no new aid policy was adopted until the International development strategy in May 2022, nearly six years after the Brexit referendum, leading to a sense of strategic drift among many stakeholders.

2.3 It was against this backdrop of uncertainty that the UK had to mount its international response to the COVID-19 pandemic. This was a rapidly evolving global crisis with potentially devastating impacts on developing countries. As we recounted in our three reports on the COVID-19 response, DFID and FCO put in place mechanisms at global and country levels to track the evolving crisis, and processing the resulting data was itself a major undertaking which at times threatened to overwhelm the available capacity. As well as planning rapid humanitarian support for the most vulnerable countries and populations, the departments worked to adapt many bilateral programmes to help partner countries manage the pandemic and its economic and social impacts.

2.4 COVID-19 also impacted on the UK’s ability to deliver aid. In March 2020, FCO implemented a mandatory withdrawal of UK staff from 36 countries for periods of three to six months. While FCO had a responsibility to protect all UK government staff posted overseas, ICAI found that other donors took greater account of individual staff preferences. In our reviews, many aid staff spoke of the difficulties of managing the pandemic response remotely while simultaneously finding accommodation and managing home-schooling and childcare in the UK. Border closures and social distancing measures in partner countries also limited the ability of staff and implementing partners to travel and supervise aid programmes. Finally, as discussed below, the impact of COVID-19 on the UK’s own economy triggered a reduction in the aid budget, which is based on gross national income (GNI) for 2020, leading to major in-year budget reductions in bilateral programmes. An ICAI review of the management of the aid-spending target found that the government’s use of a pessimistic GNI forecast led to more severe reductions than were in fact necessary, creating additional value for money risks.

2.5 Although undoubtedly the largest, COVID-19 was not the only international crisis during this period. The takeover of Afghanistan by Taliban forces in August 2021 led to a mass evacuation from Kabul, requiring the diversion of FCDO resources. Just a few months later, the Russian invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 triggered a major geopolitical crisis, leading in turn to refugee movements unparalleled in Europe since the Second World War. The disruption to global markets caused by the Ukraine crisis led to sharp rises in international prices for food and agricultural inputs, triggering a widespread food security crisis.

The merger of FCO and DFID

2.6 In the early months of the pandemic, on 16 June 2020, the then prime minister, Boris Johnson, announced the merger of FCO and DFID. In his speech to Parliament, he stated that the pandemic had shown the distinction between “diplomacy and overseas development” to be “artificial and outdated”, and that the division into two departments meant that no single decision-maker had a comprehensive overview of the UK’s international engagement. The merger would empower the foreign secretary to decide which countries received UK aid, and to deliver a single UK strategy for each country, under the leadership of the UK ambassador. Other government documents from that time emphasise that the merger would enable an all-of-government approach to complex international challenges, helping to promote the UK as a “force for good” in a changing world. High ambitions were set for the merger: the then foreign secretary, Dominic Raab, stated that the new department would represent “the best of both” of its predecessors.

2.7 FCDO launched less than three months later, on 2 September 2020. The merger came at an inopportune time, when both DFID and FCO were dealing with COVID-19 lockdowns and mobilising the UK’s global response to the pandemic. A Transformation Directorate was established to manage the process. Initially, it set out an expansive transformation agenda, designed to create a modern and effective FCDO able to deliver the UK’s international objectives, achieve value for money and become an employer of choice for talented people from all backgrounds.

2.8 However, in February 2022, the government’s Infrastructure and Projects Authority (IPA) found the agenda to be overambitious and unachievable, given competing demands on the department’s resources. In response to the IPA’s recommendation, the agenda was scaled back to a more limited portfolio of activities focused on enabling FCDO to operate as a single organisation (the ‘Integration Portfolio’). These included aligning pay structures, building a common finance and human resources system, creating a shared IT architecture and integrating former DFID- and FCO-managed aid programmes onto a common platform. The more ambitious, longer-term objectives were collected into a second portfolio, ‘Future FCDO’, to be pursued through an open-ended process of continuous improvement, rather than a time-limited change management exercise.

2.9 The Integration Portfolio was formally closed in July 2023. However, the IPA noted that there was still work to be done to achieve full integration – particularly in the human resources area – and to realise the benefits of the merger. Similarly, ICAI’s March 2022 review on tackling fraud found that the programme management and counter-fraud systems from the two predecessor departments were still operating in parallel at the time of publication (see Box 1), while our April 2023 review of FCDO’s Programme Operating Framework found that the FCDO programme management system was not yet fully integrated with the new joint finance system.

2.10 The department was initially set up without any senior role focused solely on development, with directors general given responsibility for both thematic and geographical areas. However, this changed over multiple rounds of restructuring. In March 2022, a new post of director general for humanitarian and development was created, with expanding responsibility over time. A second permanent under-secretary post was later also established, serving as an accounting officer role for aid spending. There were also changes at ministerial level, with a minister for development sitting in Cabinet since October 2022. These appointments have raised a question as to whether the original vision of a fully merged, geographically based configuration is gradually being dropped, in favour of giving development cooperation a more distinct place in the departmental structure. As yet, however, there is no return to having a separate wing for development, as in previous merged departments.

2.11 The practical challenges raised by the merger inevitably had an impact on the aid programme, leaving the department inward-focused and distracted for much of the period. One of the chief concerns from stakeholders both within and outside the department was the loss of development expertise during the transition. Several ICAI reviews noted an erosion of technical capacity and institutional memory. ICAI’s democracy and human rights review, for example, found that the departure of DFID governance experts (particularly senior advisers and local staff), or their move into other roles, had reduced FCDO’s ability to pursue its objective of promoting democracy around the world. In our aid to agriculture review, we found that the number of food and agriculture advisers had fallen by 25% between 2019 and 2023. We also found that the expertise DFID had acquired on managing complex emergencies, which proved critical in the early phase of the pandemic response, had diminished.

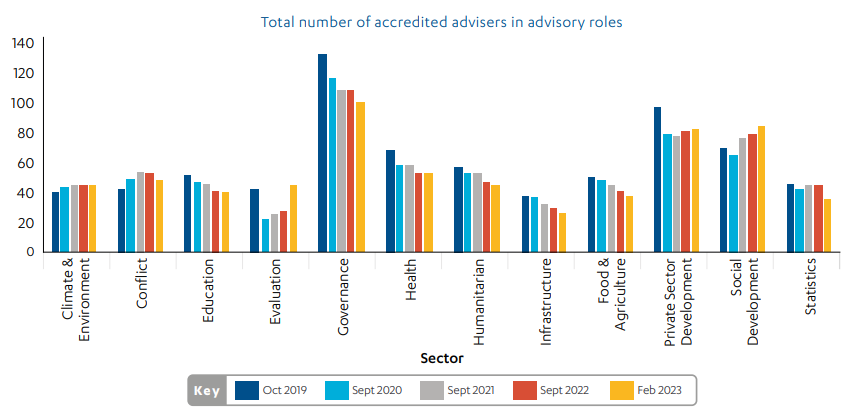

2.12 Staffing figures provided by FCDO show that the loss of experts in advisory roles varied across professional cadres (see Figure 1), with governance, health, humanitarian, and food and agriculture (formerly livelihoods) the most affected. (Accurate data are not available on the economist cadre). Some cadres started to recover the lost ground in 2023, although mostly through the accreditation of existing staff rather than external recruitment. According to FCDO officials, the overall rate of attrition of staff did not increase as a result of the merger. Rather, staff shortages arose from a hiring freeze imposed during Dominic Raab’s tenure as foreign secretary and, subsequently, from barriers to external recruitment. Furthermore, the decision to make FCDO a ‘reserved’ department means that only UK nationals can be appointed to UK-based roles, although existing non-UK nationals retain their jobs. One of DFID’s greatest strengths was that it could recruit leading experts externally from around the world, and this has been impaired by the merger.

Figure 1: Changes in expert staff in advisory positions since 2019

Source: Data provided by FCDO Heads of Profession Group.

2.13 In our interviews and focus groups, former FCO officials also expressed concerns about aspects of the merger. Some found the responsibility of managing large aid programmes to be burdensome, and felt that heavy financial management processes deprived them of the agility that had been the hallmark of FCO’s use of aid. Others questioned the value of making ambassadors responsible for large aid budgets, as this took their time away from diplomatic engagement, and were concerned that former FCO staff would no longer qualify for ambassadorial posts in countries with large aid programmes.

2.14 There are unresolved questions about the role of specialist expertise within FCDO. Whereas senior management continue to say that specialist expertise is valued, ICAI has encountered a perception among specialists that it is not valued as much as in the past. ICAI has often been told by external stakeholders around the world that the UK’s influence on international and national partners rests on the quality of its research and analysis, and its ability to offer high-quality technical inputs on policy issues. If FCDO chooses to prioritise generalist over specialist skills in recruitment and career progression, it risks losing depth of expertise over time.

2.15 One of the most negative impacts of the merger has been on country-based staff (that is, nationals of the partner country, recruited and employed locally). In DFID, country-based staff were eligible for promotion to senior advisory positions and to apply for jobs in other countries, but this was less common in FCO, where few country-based staff held specialist roles. Past ICAI reviews have commented on the value that country-based staff brought to the aid programme, given their deeper knowledge of country contexts and languages, and their networks of contacts. In our interviews and focus groups, many country-based staff reported feeling disempowered and demoralised. They told us that they faced restrictions on their access to information, their ability to represent the department externally and their career prospects. This trend does not sit well with a recommendation by the International Development Committee that FCDO should promote diversity, equity and inclusion within its own workforce and across the aid sector. FCDO informs us that it has recently started work on strengthening career pathways for country-based staff.

2.16 Looking forward, combining development and diplomatic skills within the merged department could still have benefits to offer, potentially bringing both greater political acumen to the aid programme and a more developmental perspective to UK diplomacy. Whether the merger will deliver this potential, however, remains uncertain. So far, we have seen only a few examples of benefits in our reviews, including positive UK engagement on global climate action, a stronger focus on development issues beyond former DFID priority countries, and improved collaboration with the Ministry of Defence on tackling sexual exploitation and abuse by international peacekeepers. A recent Royal United Services Institute study of FCDO’s work in East Africa was somewhat more positive, suggesting that the merger had led to improved diplomatic support for some development objectives, and better links between trade and development initiatives. However, it also noted concerns among some stakeholders that human development had been deprioritised in favour of commercial and security concerns. By and large, the officials we spoke to who were focused on global development challenges, as opposed to in-country aid delivery, were more optimistic about the potential of the merger. However, we have also seen risks, as the merger beds in, that UK aid is used in a short-term or transactional way, to facilitate diplomatic access, especially in settings where the UK has strong national interests at stake. In our country portfolio review of UK aid to India, we raised concerns that aid was being used to support the bilateral relationship and lacked a strong enough focus on development outcomes.

2.17 By mid-2023, there were signs that FCDO was finally getting on top of the ‘nuts and bolts’ challenges posed by the merger, many of which should prove to be transitional in nature. Yet the strong consensus among the stakeholders we spoke to and the external commentary we reviewed was that the merger represented a significant setback in the UK’s ability to provide high-quality development assistance, while the gains in terms of more joined-up external engagement remain uncertain. Inevitably, DFID and FCO had different cultures and ways of working. Most stakeholders are of the view that the FCO culture has emerged as dominant within the merged department. They point to a decline in transparency, lower levels of external consultation, less focus on evidence and learning, more hierarchical decision-making and a reduced culture of internal challenge. FCDO was assessed in the International Aid Transparency Index for the first time in 2022, where it scored 13.5 percentage points lower than DFID in 2020. The department continues to struggle with its IT platforms for storing data and documents from past aid programmes, which risks a large-scale loss of institutional memory. The UK development non-governmental organisations (NGOs) we spoke to told us that there was less consultation on FCDO’s policies and priorities, and that they now felt more like service providers than strategic partners. We found that the new Programme Operating Framework (PrOF) is a sound document, setting down clear principles for good development practice. However, there remains work to do in institutionalising this way of working across the department, with compliance not yet strong.

Box 1: Fraud and corruption risks in UK aid

Our April 2021 review on tackling fraud in UK bilateral aid found that stakeholders faced a range of hurdles in highlighting or reporting fraud, including the fear of being identified or disadvantaged. These issues, combined with weaknesses in whistleblowing and procurement oversight and data analysis, may negatively affect the amount of fraud detected in UK aid. At the time of our follow-up review in 2023, three out of four recommendations from this review remained inadequately addressed. Our 2023 PrOF review also showed unsatisfactory compliance in several areas of programme management, with a lack of leadership on the part of senior management. FCDO has a much wider range of issues to address than DFID did, and it will need to ensure that its systems and culture are conducive to fraud prevention and detection.

Managing budget reductions

2.18 The impact of the merger is difficult to disentangle from the effects of the successive UK official development assistance (ODA) budget reductions implemented over the same period, which most stakeholders saw as more damaging. There were several phases:

- In 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic caused a sharp contraction in the UK economy, which translated into a reduced absolute aid-spending target. (It is government policy to meet but not exceed 0.7% of UK GNI). In July 2020, the government began to implement a £2.94 billion (19%) in-year reduction in aid spending based on a pessimistic GNI forecast, and failed to adjust its plans when higher forecasts became available. In the end, the GNI contraction was not as severe as anticipated but it was too late to restore funds to bilateral programmes, and additional funds were allocated as multilateral contributions at year end instead, to make up the difference. An ICAI review found that, if the government had taken account of later forecasts, it could have managed the uncertainty by varying the timing of multilateral payments, which had been the practice in other years, and this would have reduced the real-world impacts.

- In 2021, the government reduced the aid-spending target to 0.5% of GNI, explaining this as a temporary measure in response to the impact of the pandemic on UK public finances. This measure remains in place. While it is government policy to return to the 0.7% target “when fiscal conditions allow” – namely, when the Office for Budget Responsibility’s (OBR) fiscal forecast shows, on a “sustainable basis”, that the UK is not borrowing to support day-to-day spending, and when underlying debt is falling. Current OBR forecasts suggest that this may be several years away. This decision led to a further £3 billion (21%) reduction in the 2021 aid budget, compared to 2020.

- From 2020, the cost of supporting refugees and asylum seekers arriving in the UK rose sharply, absorbing a larger share of the aid budget. Under international rules, the first year of support to refugees arriving in donor countries can be reported as ODA. As we recounted in a March 2023 report, an increase in arrivals led to the Home Office accommodating asylum seekers in hotels, at high cost. In 2021, in-donor refugee support costs absorbed over £1 billion, or 9%, of the UK aid budget, and in 2022 this rose to around £3.7 billion, or 29% – double the average of other donor countries. Difficulties in forecasting the scale of the refugee support costs led FCDO to place its own aid spending on hold for five months in 2022, with some exemptions for “essential” spending. While the chancellor responded by increasing the aid budget by £2.5 billion over two years, this only partially mitigated the disruption to the aid programme.

2.19 While the aid budget is not within FCDO’s control, reports by ICAI and the National Audit Office have been critical of the department’s management of the reductions for lacking a focus on development outcomes, as well as HM Treasury’s inflexible interpretation of the target. Repeated in-year budget reductions and the continuing lack of predictability in the aid budget have undermined the UK’s reputation as a reliable development partner. In 2021, FCDO officials were not permitted to communicate openly to partners about planned reductions in programme budgets, which reduced their ability to mitigate the impact. According to the implementing partners we consulted, many aid programmes lost key components or activities – especially monitoring, evaluation and learning – leaving them with reduced value for money or sustainability prospects. Many informed us that the abrupt nature of the reductions had damaged their relationships with local partners and communities, and caused them to lose experienced staff.

2.20 The reduced budget and continuing budget uncertainty have had many impacts across the aid programme, including a reduced ability to respond to global crises and emerging challenges. UK bilateral humanitarian aid fell by half between 2020 and 2021. While providing access to protection in the UK for refugees is an important international obligation, the reallocation of resources away from supporting people affected by humanitarian crises worldwide to meet soaring costs for asylum seekers and refugees in the UK is an inefficient use of the aid budget and undermines the previous UK policy of supporting refugees in their region of origin. It has meant that UK support for global relief and recovery efforts – for example, in response to the August 2022 floods in Pakistan and the worsening drought in the Horn of Africa – was significantly smaller and pledged later than in previous years. This has diminished the UK’s ability to play a leading role in the international response to crises. This pattern appears to be continuing in 2023-24. An equality analysis conducted by FCDO on the budget reductions planned in the 2023-24 financial year acknowledged that there will be a “severe impact” on support to some of the world’s most vulnerable people, including in Afghanistan, Yemen, Syria, Nigeria, Somalia, Ethiopia, South Sudan and Myanmar.

2.21 In our consultations with both internal and external stakeholders, a prominent message was about the debilitating effects of budgetary uncertainty on the UK aid programme, which for several years now has made forward planning all but impossible. In its 2022-23 annual report, FCDO was able to provide forward plans for aid spending per country, having been unable to do so the previous year. However, with domestic refugee costs potentially continuing to absorb a large part of the UK aid budget in 2023, FCDO is still operating in an environment of considerable uncertainty. The government has rejected ICAI’s recommendations to cap the proportion of the aid budget that can be spent on in-country refugee costs or set a floor for FCDO’s budget, which would have reduced the uncertainty.

The strategic direction of UK aid

2.22 A common finding across ICAI reviews – supported by feedback from a broad range of FCDO officials and external stakeholders – is that this has been a period of strategic drift, as a succession of new ministers have sought to define the role of UK aid in a changing global environment. In the absence of a clear strategic direction, significant shifts in priorities have come about as a result of financial pressures from a sharply reduced aid budget. The most pronounced of these is the redirection of around £3.7 billon of the annual aid budget away from developing countries to support asylum seekers and refugees in the UK (partially offset by increasing the aid budget by £2.5 billion over two years), which has severely undermined the government’s ambitions for the aid programme. There is no reference to this as a priority in government publications detailing their strategy for aid and development, such as the International development strategy or the Integrated review of security, defence, development and foreign policy. This approach has come about not through strategic choice, but because of the UK’s interpretation of its aid-spending target.

2.23 For most of ICAI’s third Commission, the 2015 strategy – UK aid: tackling global challenges in the national interest – set the strategic framework for the aid programme, at least on paper. However, by 2019, through changes in government and lapse of time, it had ceased in practice to provide a reference point for aid programming. Delays in the preparation of a new strategy were followed by the disruption of the pandemic, a succession of budget reductions and changes in government priorities.

2.24 In December 2020, after major reductions to bilateral programmes in July, the then foreign secretary, Dominic Raab, laid out seven global challenges for UK aid to focus on. In March 2021, the government released its Integrated review of security, defence, development and foreign policy. This document set out a number of new priorities, such as building resilience in the face of threats to security and prosperity, and announced a shift of geographic focus, including an ‘Indo-Pacific tilt’. It also foreshadowed the imminent release of a new International development strategy (IDS). However, the new IDS was not released until 14 months later, in May 2022, under a new foreign secretary, Liz Truss. The IDS sets out four priorities:

- deliver honest and reliable investment

- provide women and girls with the freedom they need to succeed

- provide life-saving humanitarian assistance

- take forward the government’s work on climate change, nature and global health.

2.25 The flagship initiative in the IDS was ‘British Investment Partnerships’, which covers a range of economic initiatives including rebranding the UK’s development finance institution British International Investment (BII), the ‘Clean Green Initiative’ (clean energy partnerships), support for infrastructure and capital markets, more use of UK guarantees, UK Export Finance and the conclusion of new trade agreements with developing countries. As we noted in our 2020 review of the government’s management of the aid-spending target, HM Treasury rules requiring a proportion of DFID’s budget to be allocated to capital expenditure (that is, investments that add to the government’s assets) were met in large part through significant capital injections to BII, given relatively few other bilateral options.

2.26 Less than a year later, the government issued an update or ‘refresh’ to the Integrated review in response to the Russian invasion of Ukraine and a deteriorating geopolitical environment. The document notes the intensification of transnational challenges, including global health threats, climate change and conflict. It reaffirms the four priorities in the IDS as the overarching goals of UK aid through to 2030, but states that they will be pursued in the short term through seven initiatives. The additional short-term priorities include promoting food security and nutrition, and reform of the global financial system to make it better equipped to deal with global challenges.

2.27 In April 2023, development minister Andrew Mitchell launched a ‘rebranding’ of UK aid as ‘UK International Development’, or UKDev, as part of an effort to rebuild international partnerships and shore up domestic support for UK aid. Shortly afterwards, in July 2023, he also announced that the government would publish a new international development white paper focused on climate finance and getting the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) back on track. This suggests further changes in priority may be imminent.

2.28 After a lengthy gap in the updating of sectoral and thematic strategies, the last two years have seen a number of new publications, including on health systems strengthening, ending the preventable deaths of mothers, babies and children, a humanitarian framework, an international women and girls strategy, and an international climate finance strategy. However, stakeholders noted that, given continuing budgetary uncertainty, many of these strategies are not yet supported by spending commitments and a pipeline of future programming.

2.29 The new strategies indicate that UK aid retains a number of its long-standing priorities, including gender equality and girls’ education, international climate finance and humanitarian support. They contain new emphasis on global threats and global public goods, including reform of the international financial system, fairer global tax systems, preventing global health crises and promoting food security.

2.30 In our consultations, stakeholders raised various concerns about the strategic direction of UK aid. First, there were concerns that the UK has reduced its focus on the eradication of extreme poverty. While poverty reduction remains the statutory purpose of UK aid under the International Development Act, it no longer features prominently in the strategy documents. Current strategies also signal a shift of geographical focus – both the ‘Indo-Pacific tilt’ and, within Africa, towards more mature markets and future trading partners. When combined with major international climate investments in energy transition and low-carbon development, this suggests a rebalancing in favour of middle-income countries. It is also notable that the SDGs have not been a prominent reference point for UK aid over this period, although very recently they have come back into focus.

2.31 Second, stakeholders raised concerns about the emphasis on UK ‘national interest’ and ‘mutual prosperity’, which has been growing in prominence since 2015. A June 2023 ICAI review found that the most recent trade programmes had an increased emphasis on ‘secondary benefits’ to the UK, in addition to the primary goal of supporting developing countries. Since 2019, ICAI has flagged the need for stronger guidelines to ensure that the pursuit of commercial and other benefits to the UK does not detract from the quality of development programming.

2.32 Analysis of the government’s aid-spending commitments, especially given the reduced aid budget, provides important information on priorities. The UK has committed to spending £11.6 billion in international climate finance over the 2021-26 period, of which £3 billion will be for the protection of nature and at least £1.5 billion per year by 2025 to support adaptation. Recent press reporting has cast doubt on whether this commitment is still achievable, given the reduced aid budget, although a government spokesperson responded by denying that the pledge had been dropped. The increasing prominence given to supporting climate action in developing countries is one of the clearest trends in UK aid over the period, and has led to a growing tendency for aid programmes across all sectors to include climate components.

2.33 The other major visible financial commitment is to private sector development and investment promotion. BII plans to commit around £9 billion in new investments over the 2022-26 period, on top of its existing investment portfolio of £7.5 billion. This includes £250 million to support the rebuilding of Ukraine. The UK also hopes to mobilise up to £8 billion per year in other investments, including from the private sector, by 2025, through its British Investment Partnerships. BII’s investments are not visible in the aid statistics, as the UK chooses to report as aid its capital injections into BII, rather than outward investment from BII. However, they represent an increasingly important part of UK aid, with an additional £3 billion entrusted to BII between 2018 and 2022. The increased prominence of development finance also implies a geographical shift towards more mature markets, where more and larger investment opportunities are available. In our 2022 India country portfolio review, we noted that 28% of BII’s recent investments had been made in India.

2.34 In a July 2023 letter to Sarah Champion MP, chair of the International Development Committee, development minister Andrew Mitchell stated that FCDO had sought to reduce the impact of budget reductions on the poorest countries, drawing on an ‘equality impact assessment’ prepared by the department. This had involved protecting humanitarian allocations to some of the most vulnerable countries, including Afghanistan, Yemen, Syria and Somalia. The letter further states that 2024-25 spending plans have been informed by data and modelling on equality, humanitarian need and extreme poverty. While ICAI recognises these efforts to reduce the impact on poor countries and vulnerable people, we note that they are only a partial mitigation of the effects of successive budget reductions.

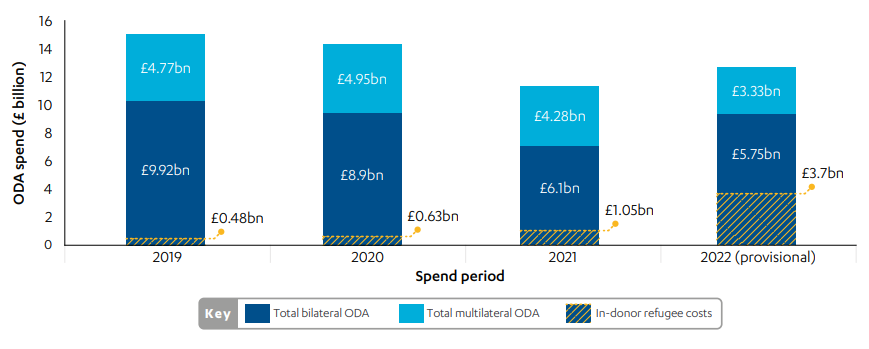

2.35 The balance between bilateral and multilateral aid has shifted over the period, as shown in Figure 2, and this too has been driven less by strategy than financial imperatives. From 2019 to 2021, reductions in the overall aid budget fell disproportionately on bilateral aid, because many multilateral contributions are subject to multiannual agreements. In 2022, when sharper reductions had to be made to meet targeted cuts, there were more opportunities to reduce multilateral aid through:

- the scheduled phasing out of aid through EU institutions

- reduction of 54% in UK contributions to the World Bank, 30% to the African Development Bank, and 30% to the Global Fund, which fights HIV/AIDS, tuberculosis and malaria

- sharp reductions in UK contributions to UN agencies, including UN Women (down by 77% from 2020 to 2022) and the United Nations Development Programme (down by 80%).

2.36 However, leaving aside refugee support costs in the UK, bilateral aid has seen much larger reductions, both absolutely and in proportion to total aid, than multilateral aid. This is despite a statement in the IDS that FCDO would “substantially rebalance its ODA investments from multilateral towards bilateral channels.” If and when there is a decision to return to the 0.7% of GNI statutory aid-spending target, it is likely to take some time to scale up bilateral spending, given the lead times involved in developing new programmes. The forthcoming white paper on international development may offer an opportunity for a more strategic look at the balance between multilateral and bilateral aid. ICAI has highlighted the importance of having a large enough multilateral aid budget to enable effective management of the spending target.

Figure 2: ODA spend 2019-22, including in-donor refugee costs

2.37 A major shift has been towards more aid spending in the UK. Although difficult to quantify in full, the pattern is pronounced. The spiralling cost of supporting asylum seekers and refugees in the UK is a stark example. There was no rationale other than a fiscal one for shifting resources on such a scale away from countries in crisis, where the funds could have helped many more people. ICAI has also commented on the substantial share of UK ODA-funded research allocated to UK universities. While research that benefits developing countries is ODA-eligible wherever it is conducted, the amount of ODA channelled to UK research institutions has at times appeared contrary to the UK’s commitment to untying all its development aid.

3. Delivering results in challenging circumstances

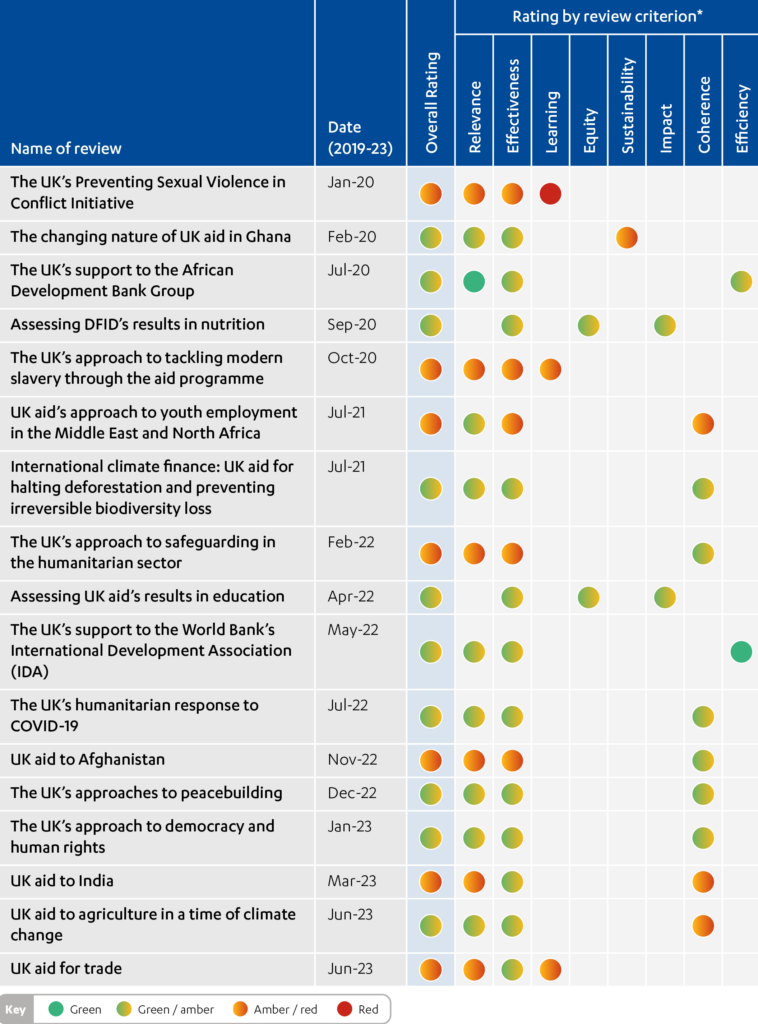

3.1 The turbulence facing the UK aid programme in recent years has given a distinct pattern to ICAI review findings during this Commission. Many of these reviews have covered the performance of UK aid in particular countries or thematic areas over the period since 2015 or even earlier, providing an overall review score, as well as scores for different criteria such as relevance, coherence, and effectiveness. Most of our scoring has been positive, with 11 overall green-amber scores out of 17 scored reviews (see Table 1). This reflected generally positive ratings for the relevance of aid programmes (9 out of 15 green or green-amber scores) and their effectiveness in delivering their intended results (12 out of 15 green-amber scores). UK aid generally scored well for coherence across UK government departments (six out of nine green-amber scores), but poorly for learning (one red and two amber-red scores, of the three reviews that were scored).

3.2 Overall, this is a positive set of findings which shows the value that has been delivered through UK aid in recent years. However, the picture is qualified by concerns raised in a number of ICAI reviews as to whether the conditions are still in place to sustain this quality of programming in the future. For example, our review of the UK’s approach to human rights and democracy awarded a green-amber score overall, but raised concerns about a loss of responsiveness and technical capacity within FCDO, which has led to programmes becoming less effective since 2020. Our review of UK aid for trade found that budget reductions had left the portfolio more fragmented and less focused on poverty reduction. On agricultural programming, we noted a decrease over time in the UK’s technical capacity and strategic clarity, and observed that the UK’s reputation for thought leadership was declining. Overall, the pattern of scores shows a slight deterioration in performance from the second to the third Commission.

3.3 This chapter nonetheless presents some of the most important results to have emerged from UK aid over the period, and highlights the underlying strengths of UK aid that can be built upon in the future.

Table 1: Scoring from 17 ICAI Phase 3 reviews

*ICAI reviews award a score to each of the review criteria, which vary according to the focus of the review. These scores are averaged to generate an overall score.

Climate and nature

3.4 UK climate finance has grown in volume over the period. The International climate finance strategy, published in March 2023, reiterates the UK government’s commitment to spending £11.6 billion on international climate finance between 2021-22 and 2025-26. Priority areas for action include clean energy, nature for climate and people, adaptation and resilience, and sustainable cities, infrastructure and transport. The UK also committed in 2019 to aligning all its aid with the 2015 Paris Agreement, a global framework intended to limit global warming to well below 2°C. UK climate-related programming contributes to three of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs): SDG 13 on climate action, SDG 14 on life below water, and SDG 15 on life on land.

3.4 UK climate finance has grown in volume over the period. The International climate finance strategy, published in March 2023, reiterates the UK government’s commitment to spending £11.6 billion on international climate finance between 2021-22 and 2025-26. Priority areas for action include clean energy, nature for climate and people, adaptation and resilience, and sustainable cities, infrastructure and transport. The UK also committed in 2019 to aligning all its aid with the 2015 Paris Agreement, a global framework intended to limit global warming to well below 2°C. UK climate-related programming contributes to three of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs): SDG 13 on climate action, SDG 14 on life below water, and SDG 15 on life on land.

3.5 ICAI reviews have found that the UK has helped galvanise international action on climate change. In June 2019 the then prime minister, Theresa May, delivered a speech promising to “put the UK at the forefront of climate action at the G20”, including through the UK’s hosting of the COP26 international climate conference in Glasgow in 2021. The government worked closely with multilateral partners to raise their ambitions on climate finance and to improve the quality of their climate work. As a result of pressure from the UK along with other shareholders, climate change was included as a ‘special theme’ in the past three replenishments of the World Bank’s International Development Association (IDA), and the Bank launched a new and more ambitious Climate Action Plan (2021-25) in the lead-up to COP26. We found relatively little focus on climate, including adaptation, in the World Bank IDA country portfolios we reviewed, but this appeared to be changing after COP26.

3.6 UK aid has also helped leverage other finance and investment for climate change. There are positive examples in India, where the UK has combined technical assistance on policy reforms with well-targeted investments. Working in partnership with the Indian government and financial institutions, it has invested in green infrastructure companies and investment platforms for renewable energy, energy efficiency, energy storage, electric public transport and waste management. We found that the UK aid portfolio in India is helping to demonstrate the viability of private investment in projects that contribute to environmental sustainability (see Box 2).

Box 2: Emerging impacts of climate investment in India

UK investments in India have increased renewable electricity generation capacity in central and state-level grids, helping to lower emissions during energy generation and distribution, with some suggestive evidence of indirect contributions to reducing air pollution. The UK has made pioneering investments in clean transport – for example, in the company GreenCell Mobility, which is investing in 5,000 electric buses and charging infrastructure on major bus routes. Another example is its investment in Chakr Innovation, which has developed technology to capture diesel emissions and convert them into an ink by-product. Chakr worked with India’s Centre for Research on Excellence in Clean Air to develop methods for retrofitting vehicles and devices such as generators to reduce pollution.

3.7 The UK aid programme has provided valuable and innovative support on biodiversity, with a range of relevant and credible programmes. We found that the UK was helping to tackle drivers of deforestation and biodiversity loss, including through its efforts to shape global markets for tropical timber and to improve research and forest governance. In the Democratic Republic of Congo, the Improving Livelihoods and Land Use in Congo Basin Forests programme has helped forest communities establish effective community forest management and develop sustainable rural enterprises. This was supported by legal reforms across the Congo Basin. Overall, however, the UK’s biodiversity work lacks evidence of impact at scale.

3.8 The UK’s investments in sustainable agriculture are helping build community resilience to climate change. In Malawi, UK aid has helped introduce drought-tolerant crops and shock-responsive social protection. In Rwanda, it has helped communities cope with increased risks of erosion and landslides from extreme weather. We also saw evidence of effective resilience building in India, where the UK has helped nearly 100,000 households to cope with climate change through its livelihood initiatives, and is on track to support one million people by the end of 2024.

3.9 Despite progress on climate change and biodiversity, further efforts will be needed across UK aid-spending departments if the UK is to deliver its ambitions in this area. The UK has been slow to disburse its international climate finance in relation to its commitment, and global climate finance flows remain below the $100 billion annual commitment in the Paris Agreement. FCDO also recognises the need to increase its analytical capability on climate and biodiversity, to support alignment of UK aid with the Paris climate agreement.

Economic development and livelihoods

![]()

3.10 While ICAI has not undertaken a comprehensive review of UK aid for economic growth and private sector development, it has looked at several important aspects. SDG 8 promotes ‘decent work and economic growth’, and economic growth is also a key condition for achieving other goals.

3.11 ‘Aid for trade’ – aid intended to help developing countries enjoy the benefits of trade – is a long-standing area of programming for UK aid. The ICAI review of the aid for trade portfolio found that programming was generally well aligned with the evidence on ‘what works’ in boosting trade volumes. There were positive results in promoting improved trade policy and regulations in partner countries, as well as support for them to achieve better outcomes in international trade negotiations. UK programmes had helped reduce the time and cost involved in shipping goods across national borders, and some programmes had helped create jobs in manufacturing and agriculture. However, we found that the causal links between the interventions and pro-poor growth were often weak, and that the impacts on inclusive growth were not always monitored. We also raised some concerns about the quality of jobs that were being created, and flagged continuing risks around sexual harassment and gender-based violence for female employees working at the industrial park we visited, despite efforts by a UK programme to mitigate those risks.

3.12 ICAI’s review of UK aid to agriculture – which totalled around £2.6 billion between 2016 and 2021 – found that the UK’s programming was promoting inclusive growth by helping smallholder farmers move towards commercial production. Agriculture generates around half of all jobs and livelihoods in sub-Saharan Africa. FCDO programmes had helped improve access to key inputs such as fertiliser, reduced barriers to the sale of produce and stimulated demand, and succeeded in creating employment and raising incomes. However, given the long-term nature of agricultural transformation, many programmes were too short to ensure sustainable impact. BII investments in the agricultural sector had helped promote the development of larger and more established firms, but with limited evidence of employment creation and wider development benefits. New BII thematic strategies in 2020 have helped improve its focus on climate change, gender and nutrition. Overall, the UK has been slow to take into consideration the accelerating impacts of climate change on the agricultural sector, but this is now changing.

3.13 The UK also funded a substantial portfolio of agricultural research. We found that research supported by DFID/FCDO had a practical focus that enhanced its impact. For example, research on biofortified crop varieties had a close link to improving nutrition. By contrast, research funded by the Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy, now the Department for Science, Innovation and Technology – especially through the Global Challenges Research Fund, which operated from 2016 to 2021 – was less practical in focus. It was also less suited to building research capacity in developing countries.

3.14 Our review of the UK’s efforts to address youth unemployment in the Middle East and North Africa found that this was not a strong focus for UK aid. The UK’s efforts to improve the business environment and promote job creation broadly aligned with the available evidence on ‘what works’, but we found the investments in skills training (including British Council ‘employability skills’ programming) to be unconvincing. We found some successes in supporting young entrepreneurs and small businesses, although at high cost per intended recipient, but little evidence overall that the portfolio was delivering jobs for young people. There had also been limited effort to tackle the social and cultural barriers that make it difficult for young women in the region to participate in the workforce.

3.15 In India, the UK has a strong focus on development investment – that is, private sector loans and equity investments that help to achieve development impact alongside a modest financial return. Alongside a substantial BII portfolio, India is the only country where FCDO directly manages development investments. Our country portfolio review found that the FCDO investments showed ‘additionality’ (benefits over and above what the markets already provide) by working jointly with Indian financial institutions, influencing their investment practices. We were less convinced by elements of the BII portfolio. For example, nearly half of BII’s investments were in financial services, and there was limited evidence that they were contributing to poverty reduction. Both portfolios reported positive results on economic growth and job creation. According to BII, its investments created 170,000 jobs in investee firms between 2017 and 2021, and over 3 million jobs through their wider economic effects. However, we raised concerns as to whether BII’s investments were making a strong contribution to inclusive growth and poverty, since many of its investments were primarily benefiting middle-class workers and consumers.

3.16 Overall, a common theme across our reviews of the economic development portfolio is that programmes lack convincing theories of change linking economic growth objectives to poverty reduction. Furthermore, there is underinvestment in monitoring and evaluation of what benefits are being delivered, and to whom. Promoting economic growth is of course an important foundation for achieving a broad range of development outcomes. However, we take the view that programmes focused primarily on growth have a responsibility to establish who is benefiting and who is missing out. This question is particularly pressing for development investments. There are clear risks that the growing scale of BII’s global portfolio will lead it to invest in more mature markets and sectors where the links to inclusive growth are often less convincing.

Women and girls

![]()

3.17 Supporting women and girls, and particularly girls’ education, has been a consistent priority for UK aid during the third ICAI Commission and has demonstrated some strong results. The UK’s efforts align with SDG 5 to ‘achieve gender equality and empower all women and girls’.

3.18 ICAI’s education review found that bilateral education programmes had improved the teaching and learning environment for girls, including by making schools safer and more accessible and by promoting gender-responsive and inclusive teaching practices. However, in our follow-up of the review, we questioned whether FCDO had an adequate approach to mainstreaming a focus on girls across its education programming. We did, nevertheless, find a focus on helping girls who are out of school to resume their education. In Ghana, for example, the UK supported 228,556 children from hard-to-reach communities, half of whom were girls, to access formal schooling. The UK also provided stipends to encourage 86,000 girls to remain in school. In Afghanistan, the expansion of women’s and girls’ access to health and education services stands out as one of the most significant achievements of UK aid. Our Afghanistan country portfolio review found that the UK had supported 2.8 million girls through school, established 1,670 community-based girls’ schools, and supported innovative efforts to drive social norm change – although what remains of these results under Taliban rule is uncertain.

3.19 It is a statutory obligation of the UK government to consider gender equality when spending aid. DFID, and subsequently FCDO, made progress on mainstreaming gender equality across policies, programmes and influencing work in many areas, but other aid-spending departments have further to go. We found a mixed record on mainstreaming gender equality into UK programming on deforestation and biodiversity loss, and our citizen engagement suggested that women were often excluded from programme processes and benefits. Our rapid review of UK support for refugees in the UK found that gender-sensitive approaches had not been mainstreamed across services for refugees provided by the Home Office and other departments, and refugees and civil society organisations (CSOs) told us that safeguarding lapses in aid-funded accommodation were widespread. Despite the priority given to gender in official policies, gender programming has been heavily impacted by recent aid budget reductions. For example, while our peacebuilding review found that gender had been mainstreamed into programming, the abrupt termination of some programmes funding women, peace and security activities had left the participating women unsupported and at risk of harm. An equality impact assessment prepared by FCDO noted that centrally managed programmes on girls’ education had lost 54% of their funding during the 2022-23 budget reductions, while funding for a pan-African programme on sexual and reproductive health rights had been reduced by 60%. This was on top of reductions from previous years.

3.20 The UK has been an effective voice for the rights of women and girls on the global stage, particularly where it has conducted high-profile campaigns. During the review period, we have assessed UK efforts to prevent sexual violence in conflict, eliminate modern slavery and tackle sexual abuse and exploitation in the international humanitarian system. All three of these topics have been high ministerial priorities for a period of time, and were strongly promoted by the UK, both through its aid programming and in international forums, helping to galvanise global action. These are, however, long-term challenges, and it is notable that momentum is easily lost as ministerial priorities move on. For example, the Preventing Sexual Violence in Conflict Initiative lost direction once William Hague was no longer foreign secretary. It has, however, received more focus again after the FCO/DFID merger.

3.21 The campaigns are most effective where the UK works at several levels, including with grassroots organisations, survivor groups, governments and the private sector. We found that programming would be improved by more engagement with survivors in programme design, although this improved in later years in response to ICAI’s recommendations. In the modern slavery review, we found that the UK’s efforts would have been improved by stronger partnerships with UK private companies, which are better placed to identify modern slavery risks within their international supply chains.

3.22 The UK has influenced its multilateral partners to prioritise gender in their programming and monitoring arrangements. In the African Development Bank, the UK has used its contributions to push for more sex disaggregation of results data, while in Afghanistan the UK was prominent in the Afghanistan Reconstruction Trust Fund gender working group, which promoted women’s empowerment and gender mainstreaming across the portfolio. In Sierra Leone, we found that the UK has worked closely with the World Bank to promote new policies on retention of girls in school, with a particular focus on girls’ secondary education. Early in the COVID-19 pandemic, FCDO commissioned its Violence Against Women and Girls helpdesk to assess the risks of increased violence against women and girls, and this was cited in strategies and guidance produced by the World Bank and the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF). In our democracy and human rights review, partners told us that the UK is viewed as a global leader on gender and inclusion.

Governance, democracy and human rights

![]()

3.23 SDG 16 focuses on ‘peace, justice and strong institutions’. Democracy and human rights have been subject to variable focus within UK development policy during the third ICAI Commission. FCO had an explicit commitment to supporting democracy and the international human rights system, which it promoted through campaigns on specific themes such as media freedom, and through small grant instruments such as the £55 million Magna Carta Fund. DFID tended to focus on inclusion and social and economic rights, including gender equality, rather than civil and political rights. With the frequent change of ministers since 2015, the language used to describe the UK’s objectives on democracy and human rights has shifted (including, at various points, ‘open societies’ and ‘network of liberty’), causing some confusion for external stakeholders. The 2021 Integrated review has a focus on ‘open societies’, particularly in the context of rising geopolitical tensions in the Indo-Pacific region, but this receives notably less emphasis in the International development strategy, while the 2023 Integrated review refresh is more ambivalent on the subject of democracy and human rights.

3.24 In our review of the democracy and human rights portfolio, which included £1.37 billion in programming over the 2015 to 2021 period, we found the programmes to be relevant and useful, supported by good levels of staff expertise, technical guidance, access to evidence, and flexibility in dynamic contexts. Across a range of countries, UK support had helped make government institutions, parliaments, political parties, media organisations and civil society bodies more effective. It had also improved rights and democratic participation for groups at risk of exclusion, such as women and girls, people with disabilities, youth and, to a lesser extent, ethnic and religious minorities and LGBT+ people. Some of the most effective programming went beyond strengthening specific institutions to nurturing coalitions for change around particular democratic or human rights challenges, therefore strengthening the democratic process.

3.25 However, we also noted instances where the UK has prioritised protecting its relationships with governments, as well as instances where restrictive funding modalities limited its ability to support journalists, human rights defenders and CSOs under threat from government repression. These factors limit its contribution to countering growing threats to civic space around the world. When reviewing UK peacebuilding activities in Colombia, we noted that the UK was reluctant to publicly condemn human rights violations by security forces. In India, we found that the UK was not active in supporting democratic space, free media or human rights, despite growing concerns about political polarisation, religious intolerance and restrictions on civil society. While the political sensitivities around these issues are often acute, the emphasis on global threats to democracy and human rights in the Integrated review seems to be at odds with this limited risk appetite. Bringing together the former DFID and FCO approaches within the merged department may create opportunities for stronger engagement, although thus far a lack of strategic direction and budget reductions have prevented the benefits from being realised.

Responding to conflict and crises

![]()

3.26 A significant share of UK aid over the period has gone towards responding to conflict and humanitarian crises. SDG 16 is about promoting peaceful and inclusive societies, including through the reduction of violence and the promotion of inclusive governance and the rule of law.

3.27 The International development strategy (IDS) commits the UK government to providing principled humanitarian assistance to people affected by crises, and providing them with the support they need to recover. At present, its ability to do so has been sharply curtailed by aid budget reductions, which saw UK humanitarian aid fall by more than half between 2019 and 2021, to £743 million. It is likely to have fallen further in 2022 and 2023. As discussed above, the UK’s decision to charge spiralling refugee support costs to the aid budget has resulted in a major reallocation of resources from crisis-affected countries to the UK. This has dramatically reduced the resources available to respond to new crises, such as the 2022 Pakistan floods and the growing food security crisis in the Horn of Africa. According to FCDO officials, ministers are committed to returning humanitarian spending to at least £1 billion per year.

3.28 ICAI found that the UK responded rapidly and flexibly to the COVID-19 pandemic, providing early, unearmarked funding to support an effective international response. DFID/FCDO directed its multilateral support towards people already affected by crises, while pivoting bilateral programmes to provide urgent support to those made newly vulnerable by the direct and indirect impacts of the pandemic. In Yemen, for example, the UK retained its existing humanitarian priorities, adapting its programmes to address COVID-19 risks and impacts. We found that DFID’s track record of aligning humanitarian and development programming and its past investments in social protection provided a strong foundation for its emergency response to the pandemic.

3.29 In our peacebuilding review, we found some high-quality interventions, combining financing, technical inputs and diplomatic engagement. Peacebuilding is a high-risk area where tangible results are relatively rare, so the review focused on more positive examples to enable lesson learning. In Colombia, patient UK engagement over a ten-year period helped put in place key elements for implementation of the peace agreement. In Nigeria, the UK played an important role in coordinating international engagement on conflicts in the northeast, with partners noting the value of its expertise and use of evidence. International partners working alongside the UK in Colombia and Nigeria also highlighted the UK’s ability to play the role of trusted partner and critical friend to host governments. However, recent capacity pressures across the department, linked to Brexit, the pandemic and the merger, have reduced the government’s ability to promote international cooperation on peacebuilding.

3.30 Afghanistan was not a positive example of peacebuilding. There, nearly £3.5 billion in UK contributions to building the Afghan state came to an abrupt end in August 2021 with the withdrawal of international forces and the takeover of central government by the Taliban. ICAI’s country portfolio review found that the UK approach to state-building did not rest on an inclusive and viable political settlement. The failure was linked to the UK’s decision to support the US-led military occupation, which prioritised excluding the Taliban over forging an inclusive political process with its more moderate elements. As the Taliban insurgency intensified, the focus on building legitimate institutions took second place to counter-insurgency operations. The huge scale of UK and international support for central government institutions had a distorting effect, contributing to corruption and political fragmentation, and leaving the UK funding an enterprise it knew had little prospect of success.

3.31 The UK also spent more than £250 million in aid on salaries for the Afghanistan National Police (ANP) and other security institutions, following a commitment it made to international partners to share security costs. The ANP acted primarily as a paramilitary force, rather a civilian policing institution, and was subject to numerous allegations of corruption and brutality. We found this to be a questionable use of the aid budget.

3.32 The Taliban takeover in August 2021 and the withdrawal of international development assistance has come at huge cost for the Afghan people, who faced a collapse in economic activity and public services. By March 2023, nearly 20 million Afghans were acutely food-insecure. In response, the UK announced a doubling of humanitarian aid to Afghanistan for 2021-22 and 2022-23, to £286 million. However, the 2022-23 allocation was subsequently reduced to £246 million and, despite efforts to protect the humanitarian allocation for Afghanistan, it has been affected by subsequent budget reductions, and will fall to a planned £100 million in 2023-24. With competing emergency needs in Ukraine, Syria, Turkey and across Africa, the UK will struggle to mount an effective response with a reduced humanitarian budget.

Global health and nutrition

![]()

3.33 Health is a clear priority in the IDS and FCDO sector strategies, with a strong focus on strengthening national health systems, ending preventable deaths for women, babies and children and, since COVID-19, on global health security. SDG 3 covers ‘good health and well-being’.

3.34 The UK has made substantial aid investments in health research stretching back more than two decades. During the third ICAI Commission, the Department of Health and Social Care (DHSC) invested more than £451 million in research tailored to the health needs of developing countries. As we noted in a 2018 review, experience with the 2014 Ebola outbreak in West Africa led to an intensification of aid-funded research on future global health threats. In 2016, DHSC awarded £1.87 million to Oxford University through the UK Vaccine Network Project for preclinical development and phase one clinical trials of a Middle East Respiratory Syndrome vaccine. This laid important foundations for the development of the Oxford-AstraZeneca COVID-19 vaccine. Two further DHSC aid-funded projects with Oxford University were also redirected during the pandemic to support development of the Oxford-AstraZeneca COVID-19 vaccine, including £1.1 million repurposed to support clinical trials in Kenya and £305,000 to support further research and development of vaccines better suited to developing countries. FCDO and DHSC officials confirmed that these investments had generated learning which helped accelerate the development and deployment of COVID-19 vaccines.

3.35 The UK also made a £250 million contribution to the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations (CEPI), to support vaccine development, manufacturing and distribution. The UK was one of the founding partners of CEPI, launched in 2017 to develop vaccines against future epidemics. CEPI in turn helped establish COVAX, an international fund to accelerate the development of COVID-19 vaccines and promote access for developing countries. COVAX in due course delivered over 1.6 billion doses of COVID-19 vaccine to 87 developing countries. Despite this important initiative, access to COVID-19 vaccines remained far from equitable. For its part, the UK donated 85 million doses of COVID-19 vaccine and supported COVAX’s COVID-19 Vaccine Delivery Partnership to increase vaccine coverage in the most vulnerable countries. The UK also contributed to the World Bank’s response to the pandemic, which included more than £20 billion in funding for vaccines and other health interventions.

3.36 The UK also supported national responses to the pandemic, mainly via multilateral partners. UK funding for the World Health Organisation, for example, enabled it to scale up its support for national health authorities during the pandemic. Support to UNICEF enabled the delivery of therapeutics, diagnostics and oxygen concentrators to vulnerable countries. The UK’s contributions to the World Bank supported a rapid, flexible and large-scale response to the pandemic, helping to demonstrate its important role as a global insurer in time of crisis. The Bank approved funding for national response efforts in April 2020, within a few weeks of the declaration of the pandemic.

3.37 ICAI found the UK’s bilateral efforts to be rapid and effective, drawing on the knowledge of staff with experience of past epidemics, including Ebola. The UK sent emergency medical teams of UK health personnel to developing countries in Africa, Asia and the Middle East, to enhance the capacity of national health systems. In Bangladesh, Ethiopia and Nepal, UK-supported technical experts posted in national health ministries were able to help national counterparts gather and analyse COVID-19 health data and design national responses. The UK also supported COVID-19 testing laboratories in Bangladesh and Nepal, helping to build resilience to future health emergencies.

3.38 The UK aid programme has also made important contributions on maternal and child health. In Afghanistan, UK support through the Afghanistan Reconstruction Trust Fund helped promote improvements in maternal and neonatal health, and to expand immunisation coverage for children under the age of two (increasing the vaccination rate from 30% in 2014 to 52% in 2019). FCDO has recently published new approach papers on health systems strengthening and ending preventable deaths. We found both to be of good quality, responding to past concerns raised by ICAI. However, budget reductions have had a dramatic impact on maternal health programming. Over the years, the UK has been the largest funder of efforts by the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) to increase the supply of maternal health and family planning commodities, and its flexible, multiannual support enabled UNFPA to reach women, girls and young people in more than 150 countries. However, UK support for UNFPA’s commodities budget was cut by 85% in 2021. UNFPA has estimated that if these funds been provided as pledged, it would have averted 47 million unintended pregnancies, 813,000 maternal and child deaths and 14.4 million unsafe abortions.

3.39 One pillar of the UK’s approach to ending preventable deaths is tackling malnutrition and promoting sustainable food systems, to make nutritious diets more affordable, accessible and climate-resilient. Between 2015 and 2019, DFID reached 50.6 million women, children under five and adolescent girls through its nutrition interventions. However, the nutrition portfolio has also suffered budget reductions, even though humanitarian need and global food insecurity were on the rise. In Kenya’s refugee camps, for example, reduced funding from the UK and other donors resulted in the World Food Programme cutting food rations for 440,000 refugees to 52% of the basic food basket (about 1,050 calories per day) from October 2021. The commitment in the Integrated review refresh to promoting global food security and nutrition would need to be backed by budgetary resources to be compelling.

4. Building for the future

4.1 This has been an exceptionally challenging period for the UK aid programme, with pressure on many fronts. The period was dominated by the COVID-19 pandemic, which required DFID and then FCDO to respond to an unprecedented global emergency, even as their own operational capacity was curtailed. Coming at this most demanding of times, the merger left FCDO distracted and inward-focused. While the department is progressively coming to grips with the practical challenges it created, there is evidence of a loss of development expertise, including country-based staff, since the merger. To achieve its objective of greater synergy between diplomacy and development cooperation, the UK will need to preserve and rebuild its expertise on global and national development challenges.

4.2 The successive rounds of budget reductions have undoubtedly caused the greatest disruption to the UK aid programme. The top-down way in which they were executed and the lack of timely communication with collaborators has damaged the UK’s reputation as a reliable development partner. On top of that, continuing uncertainty over budgets has severely constrained the government’s ability to protect its past investments and plan for the future. Much of this uncertainty has been self-inflicted, through overly rigid interpretation of the UK’s aid-spending target as both a floor and a ceiling. This was manageable in the past, when conditions were more stable. Such rigidity has now become a major obstacle to restoring the credibility of UK aid, so it was good to see a precedent set by allowing more flexibility in response to soaring in-donor refugee costs.