UK aid’s alignment with the Paris Agreement

Executive summary

The Paris Agreement is an international treaty of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change that aims to limit global warming and strengthen countries’ ability to deal with the adverse impacts of climate change. The UK government’s commitment to align its official development assistance (ODA) with the Paris Agreement was made in 2019. It reflects one of the Paris Agreement’s long-term goals – to make finance flows consistent with low-emission, climate-resilient development pathways. It is part of the UK’s ambition to integrate climate and environmental considerations into all its decision-making processes and lead by example.

This rapid review examines the progress towards aligning all UK aid with the Paris Agreement. Recognising that this commitment is relatively recent, the review focuses on the relevance and coherence of the UK’s emerging approach to alignment and its measures for delivering alignment in all UK aid-spending departments, rather than how effective these measures have been.

Findings

The UK has made an important commitment to align its aid with the goals of the Paris Agreement. It reflects the urgency of addressing the climate crisis and the reality that the level of effort needed to mitigate and adapt to climate change goes beyond channelling aid to programmes specifically addressing climate change. Since 2019, the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO) (and before 2020, the Department for International Development) has developed four programme-level tools for Paris alignment: climate risk assessment, shadow carbon pricing, fossil fuel policy, and alignment with country partners’ own mitigation and adaptation plans. In April 2021, FCDO’s Programme Operating Framework (PrOF) rule 5 mandated the use of these four tools at the design and development stage of new FCDO ODA and non-ODA programmes.

The four tools mainly reflect emerging good practice among donors for screening out high-emission development projects and identifying those with high risks of adverse climate impacts. The current programme-level approach is limited to screening out harmful activities, and does not yet contain positive selection tools designed to encourage a systemic shift towards low-emission, climate-resilient options. Such a screening out approach could be interpreted as a conditionality on aid, limiting development options available to developing country partners. In order to support developing countries’ pursuit of the Paris Agreement goals, the evolving UK approach will need to include different types of support to partners to tackle the transformational shifts necessary to achieve low-emission, climate-resilient development.

Paris alignment of aid is a challenging commitment in the absence of agreed best practice and with the high diversity of developing country contexts. The UK’s approach is work in progress. It took 21 months from the commitment being made to mandate Paris alignment to the point of establishing PrOF rule 5. There are a number of exemptions to the comprehensive application of the four alignment tools to bilateral FCDO ODA spending. For FCDO aid spent through multilateral channels and CDC Group, the UK’s development finance institution, the UK is largely reliant on these institutions’ own efforts to achieve Paris alignment. There are also gaps and inconsistencies in how other government departments pursue Paris alignment of ODA. Only the fossil fuel policy is currently a cross-government policy, whereas the three other tools are limited to FCDO ODA and non-ODA programming.

FCDO has undertaken significant work to operationalise Paris alignment. However, there is no roadmap for full operationalisation of the commitment across UK ODA-spending departments, taking into account their variable mandates and differing risks of misalignment. There is also no timeline for developing the approach beyond minimum requirements and ‘do no harm’. FCDO is planning to introduce portfolio- and strategic-level approaches to Paris alignment, recognising the importance of doing so to achieve its ambition of making transformative progress towards low-emission, climate-resilient development pathways. Such approaches would help embed Paris alignment within the multiple strategies that guide UK ODA spending, and could broaden the application of alignment rules and guidance beyond FCDO to the UK’s wider aid programming. Wider use of PrOF rule 5 guidance would also emphasise that responsibility for Paris alignment sits not only in FCDO’s Climate and Environment Directorate, but across all ODA-spending departments and teams.

Paris alignment will be implemented at the same time as UK climate finance programming to developing countries is increasing. This means that gaps in capacity and capability to apply the PrOF rule 5 guidance are likely to be felt across FCDO, as well as in other government departments, if they also adopt this guidance for their programming. The gaps will vary between the ODA-spending departments and the overseas network, depending on ODA spending characteristics, country context and the existing climate change experience and knowledge of individuals. FCDO must also pay attention to how well existing draw-down resources, such as the climate mainstreaming facility, can cope with increased demand. Outreach and training to the overseas network and other government departments on Paris alignment has recently started, but an acceleration of action will be needed across all levels of management to reflect the urgency of the problem, as well as to avoid Paris alignment being badged as a ringfenced ‘climate issue’.

Within FCDO, the application of the PrOF rule 5 guidance has so far been limited, since the rule has only been in place since 1 April 2021 and only a few new programmes have been designed and developed since then. However, it is unclear how the lines of reporting on Paris alignment between and within teams and departments will look as the alignment process rolls out. There is no metric or assessment for monitoring progress on Paris alignment, in contrast to the usual level of attention paid to the monitoring and evaluation of UK aid. This hinders the tracking of progress and the provision of public information on the commitment.

The UK has been an effective influencer within the multilateral development banks (MDBs), whose scale of investment will have impact on future emission and resilience pathways in developing countries. Together with like-minded shareholders, the UK has communicated to the MDBs the need for clear implementation plans for their Paris alignment commitments and a target date for implementation. The UK could strengthen this influencing role further, pushing beyond the MDBs to other multilaterals. This is particularly relevant considering the UK’s desire for leadership in green finance, as outlined in its 2019 Green Finance Strategy.

Recommendations

Based on the findings of this review, a number of recommendations are made to support the UK in continuing to develop its approach to aligning aid with the Paris Agreement:

- The UK should ensure that a commitment to align ODA with the Paris Agreement, with timebound milestones, is embedded at the heart of the forthcoming International Development Strategy.

- The UK needs to develop a cross-government reporting and accountability process for Paris alignment of UK ODA that ultimately allows public scrutiny of progress.

- The UK should urgently build appropriate capacity and capabilities across its ODA spending teams in order to design and deliver alignment of UK aid with the Paris Agreement.

- The UK should work with other leading countries, including developing countries, to establish and promote international best practice on Paris alignment of ODA.

Introduction

In June 2019, the UK government made a commitment to align UK official development assistance (ODA) with the Paris Agreement. This commitment was first articulated in the Green Finance Strategy, whose objective is to position the UK as a green finance centre. The commitment is reiterated in the 2021 Integrated Review of security, defence, development and foreign policy and in UK communications to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC).

The Paris Agreement is an international treaty of the UNFCCC agreed in 2015. It provides a framework to limit global warming and to strengthen the ability of countries to deal with the adverse impacts of climate change. The pursuit of these long-term goals has been dubbed ‘Paris alignment’ (see Box 3).

The commitment to align UK aid with the goals of the Paris Agreement is part of the UK government’s ambition to lead by example and integrate climate and environmental considerations into all its decision-making processes. It reflects the recognition that tackling climate change and achieving sustainable development are inextricably linked, as one cannot be achieved without the other. The August 2021 report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change confirms unequivocally that no country will be unaffected by climate change and that low-income countries, the poor and marginalised populations will be hit the hardest. Development must be climate-resilient and the alignment of all aid with the Paris Agreement will make UK aid investments more resilient to the risks caused by present and future climate conditions.

This rapid review examines the progress the UK has made towards aligning all UK aid with the Paris Agreement since its commitment to do so. Recognising that this commitment is relatively recent, dating from June 2019, the review focuses primarily on whether the UK government has put in place suitable measures for delivering alignment in aid-spending departments. It assesses the UK approach to alignment, situating it in broader emerging practice.

It is important to note that Paris alignment covers all finance flows, not just ODA. It is generally accepted that ODA alone will not be enough to support developing countries’ efforts to reach the Paris Agreement goals. There is therefore a need to ensure that all finance flows, of which ODA is only one small part, contribute to building low-emission, climate-resilient futures. Paris alignment is thus about all finance flows, including other official flows of public finance to developing countries. However, such broader efforts are beyond ICAI’s remit and this report is specifically concerned with the UK commitment to align its aid programming with the Paris Agreement.

Box 1: How this report relates to the Sustainable Development Goals

The Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) are a universal call to action to end poverty, protect the planet and ensure that all people enjoy peace and prosperity. The UK goal to align all aid with the Paris Agreement is primarily relevant to SDG 13:

![]() SDG 13: Take urgent action to combat climate change and its impacts – including building resilience and capacity to adapt, integrating climate change measures into national development strategies and promoting global mechanisms for climate action under the UNFCCC.

SDG 13: Take urgent action to combat climate change and its impacts – including building resilience and capacity to adapt, integrating climate change measures into national development strategies and promoting global mechanisms for climate action under the UNFCCC.

The growing impact of climate change means that SDG 13 interlinks with many of the other goals – including SDG 1: No poverty, SDG 2: Zero hunger, SDG 3: Good health, SDG 6: Clean water, and SDG 12: Responsible consumption and production – as it threatens our ability to achieve the goals and, in some cases, can cause a reversal of progress.

Table 1: Our review questions

| Review criteria and question | Sub-questions |

|---|---|

| 1. Relevance: Does the UK have a credible approach to aligning UK aid with the Paris Agreement? | • To what extent is the UK’s approach to alignment based on best available science and good international practice? • To what extent has the UK developed a credible approach to aligning UK bilateral aid with the Paris Agreement? • How credible is the UK’s approach to aligning its multilateral aid with the Paris Agreement? |

| 2. Coherence: Is the UK’s approach to aligning with the Paris Agreement coherent across aid-spending departments and with international partners? | • Are the systems and processes that the UK has put in place coherent across aid-spending departments to ensure alignment with the Paris Agreement? • Is the UK encouraging and supporting its bilateral partners in a coherent manner to assist alignment with the Paris Agreement? • Is the UK working coherently with other multilateral and international partners to assist alignment of development finance with the Paris Agreement? |

Methodology

Research for this review took place in May and June 2021. The alignment of UK aid with the Paris Agreement is a live policy area, and some limited data gathering continued in parallel with writing this report as government decision making evolved.

Our methodology combined the following elements:

- Annotated bibliography: A review of selected academic and ‘grey’ literature, offering a summary of context, key issues and emerging practice in the rapidly evolving field of Paris alignment.

- Process review: Document review of the UK government’s approaches to aligning UK aid with the Paris Agreement, including relevant policies, strategies, coordination mechanisms, tools, learning and accountability mechanisms across government. This was supported by key informant interviews with a cross-section of UK government officials, academics and other development partners as well as consultation with civil society and appropriate private sector representatives.

- Strategy review: A review of the UK government’s interpretation of and strategic approach to aligning its aid with the Paris Agreement. We explored the degree to which this alignment moves beyond existing climate mainstreaming and ‘do no harm’ considerations towards a more proactive alignment, and examined the climate sensitivity of aid spending by departments using the sectoral codes for reporting aid spending provided by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development’s Development Assistance Committee (OECD-DAC) – a forum of major donor countries.

- Thematic case studies: We explored aspects of the UK government’s approaches to aligning UK aid with the Paris Agreement in detail through three thematic case studies, selected to cover key issues of importance for answering our review questions:

i. How coherently are the UK aid alignment processes being implemented?

ii. Is the UK encouraging and supporting its bilateral partners in a coherent manner to assist alignment with the Paris Agreement?

iii. How credible and coherent is the UK’s approach to ensure Paris alignment in multilateral and international aid efforts?

A total of 145 individuals were interviewed, including UK government staff, bilateral and multilateral partners, and experts. Feedback was collected from civil society through two roundtables. The team talked to UK government staff in ten countries to assess the application of Paris alignment tools and guidance, including: Bangladesh, Colombia, Ghana, Indonesia, Kenya, Nigeria, Pakistan, Uganda, Yemen and Zambia.

Box 2: Limitations to the methodology

The breadth of possible interpretation of Paris Agreement ‘alignment’ makes it hard to establish best practice. Differing mandates and modes of operation mean that it is hard to compare current practice between development finance institutions. The review scope is limited to the consideration of aid and the review focuses on emerging good practice in relation to ODA, although where necessary emerging good practice in other official flows (official finance going to developing countries but not meeting the criteria for ODA) has been considered.

The UK’s commitment to align all aid with the Paris Agreement is young. For this reason, the review questions do not consider the effectiveness of the measures put in place by the UK government, but instead look at their relevance and coherence.

Background

What is Paris alignment?

As one of 191 Parties to the Paris Agreement under the UNFCCC, the UK has committed to contribute to the global achievement of three long-term goals on climate change mitigation, adaptation and financing. The pursuit of these three long-term goals can be considered as ‘Paris alignment’ (see Box 3).

Box 3: The Paris Agreement and its three long-term goals

The Paris Agreement (2015) serves as an international legal framework for the response to climate threats. The Agreement recognises the specific needs and circumstances of both developing and developed countries in addressing climate change, while also emphasising the relationship between climate change action and equitable access to sustainable development.

The Agreement aims to strengthen the global response to the threat of climate change as outlined in Article 2.1, through three long-term goals:

- Taking action to stabilise greenhouse gases at a level that will hold the increase in the global average temperature to well below 2°C above pre-industrial levels and pursuing efforts to limit the temperature increase to 1.5°C, recognising that this would significantly reduce the risks and impacts of climate change. Such efforts to reduce or prevent emissions of greenhouse gases to stabilise global temperatures are referred to as climate change mitigation.

- Increasing the ability to adapt and adjust to the adverse impacts of climate change, build resilience, and strengthen the ability to withstand climate-related impacts and foster low greenhouse gas emissions development in a manner that does not threaten food production. This is referred to as climate change adaptation.

- Making finance flows consistent with a pathway towards low greenhouse gas emissions and climate-resilient

development.

Article 2.2 notes that the Agreement “will be implemented to reflect equity and the principle of common but differentiated responsibilities and respective capabilities, in the light of different national circumstances”.

The three long-term goals of the Paris Agreement are collective goals that all countries should be aiming for in their climate actions. Each country prepares its own Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC), which sets out the country’s targets for reducing emissions and (in some cases) adapting to the impacts of climate change in contribution to the long-term goals. A ‘ratchet mechanism’ allows Parties to the Paris Agreement to assess, review and improve their NDCs every five years to ensure that the NDCs become increasingly ambitious over time. Parties are also invited to provide longer-term strategies for climate change mitigation stretching to 2050. There are a number of other reporting processes that are required or voluntary under the UNFCCC process. These include national communications, biennial reporting and the development of National Adaptation Plans, which is the newest process to identify medium- and long-term adaptation needs and to develop and implement strategies and programmes to address those needs.

Neither the Paris Agreement nor other UNFCCC decisions and documentation define what ‘consistency’ of finance flows with a pathway towards low-emission and climate-resilient development entails, nor do they provide guidance on how to get there. Despite this, many donors and development finance institutions have committed to become ‘Paris-aligned’. Pathways to operationalising alignment commitments are, however, still emerging.

Alignment with the Paris Agreement and its long-term goals is generally understood to involve a requirement to go beyond a ‘do no harm’ and a mainstreaming of climate change approach. This means that the alignment of aid with the Paris Agreement should not only be about screening out activities that increase or lead to unnecessary emissions or higher risks of adverse impact of climate change. Aid must also seek to make a positive contribution to the urgent system-wide transformations that are needed to achieve low-emission, climate-resilient pathways to development. While not all activities supported by ODA need to include active climate objectives, as the OECD says, it is nonetheless critical that aid as a whole supports a system-wide transformation.

The UK will co-host the 26th Conference of the Parties (COP26) to the UNFCCC in November 2021 with Italy. COP26 will bring together countries and a range of stakeholders to take forward agreements on tackling climate change and its adverse impacts. Paris alignment of ODA is not a discrete topic that will feature in negotiations at COP26. However, the UK’s commitment to align its aid spending does relate to the Paris Agreement’s long-term collective goal to align all finance flows – of which ODA is one – with low-emission, climate-resilient development pathways. Providing insights into the degree to which the UK has implemented this commitment has the potential to support the ambition of mitigation and adaptation actions across all countries, developed and developing alike.

The four tools used to progress Paris alignment of UK aid

In the 2019 Green Finance Strategy the UK announced that it was using four tools to implement Paris alignment of aid at the programme level:

- Conducting a formative climate risk assessment to inform programme design and activities.

- Using an appropriate shadow carbon price in relevant bilateral programme appraisals.

- Ensuring programming is in line with the government’s fossil fuel policy, and prioritises alternatives to investment in fossil fuels.

- Ensuring programmes are aligned with and, where possible, elevate countries’ Nationally Determined Contributions (NDC) and adaptation plans.

Guidance for these four tools was elaborated in the 2020 FCDO Climate and Environment Smart Guide.

It was not until ‘rule 5’ was introduced as part of FCDO’s new Programme Operating Framework (PrOF) on 1 April 2021 that these four tools together became mandatory requirements of FCDO’s programming. The PrOF merged the two operating frameworks of the former Department for International Development (DFID) and Foreign and Commonwealth Office (FCO) to create a unified programme framework for FCDO. The PrOF covers all FCDO’s new programming, ODA and non-ODA, but is not applied retrospectively to existing programmes.

Findings

In this section we present the main findings from our rapid assessment of the relevance and coherence of the UK’s commitment to align its official development assistance (ODA) with the Paris Agreement.

The UK has made a strong and relevant commitment to Paris alignment of aid

The Paris Agreement does not specify a requirement for countries to align aid with its objectives. The UK commitment is an application to ODA of the third long-term goal of the Paris Agreement, which is to make all finance flows consistent with a pathway towards low greenhouse gas emissions and climate-resilient development. It also responds to the OECD’s call in 2019 for aid providers to align their efforts with ambitious climate action.

The commitment to ensure that UK aid is Paris-aligned recognises that climate change undermines development gains and poverty reduction. It is also part of the agenda of the UK’s 2021 Integrated Review of security, defence, development and foreign policy, which recognises that the adverse impacts of climate change have implications for UK diplomatic objectives (including trade and security).

The UK is the only country to make an explicit cross-government commitment to the Paris alignment of aid, but it is not alone among aid providers in pursuing alignment. In late 2017, for example, six multilateral development banks (MDBs) and the International Development Finance Club (IDFC) announced their intentions to align with the Paris Agreement. Among development cooperation agencies, the Agence Française de Développement (AFD) was one of the first institutions, in 2017, to announce its intention to make its activities ‘compatible’ with the Paris Agreement. Other countries have continued to advance tools and methods for ensuring ODA programming is consistent with climate objectives.

The UK commitment is widely welcomed but acknowledged to be challenging, due to the lack of UNFCCC definitions or guidance and a lack of tested best practice. The Paris Agreement seeks for all finance flows (public and private, international and domestic – of which ODA is only a small part) to be consistent with climate objectives. Some stakeholders have concerns that efforts to align aid flows could lead to a reduction in climate ODA and become a distraction from developed countries’ obligations to support and mobilise finance for climate change mitigation and adaptation in developing countries (as included under Article 9 of the Paris Agreement). The obligation to mobilise finance in developing countries to mitigate and adapt to climate change is often referred to as climate finance, and is distinct from the commitment of aligning aid flows with climate objectives (see Box 4).

The alignment of aid with the Paris Agreement is not reflected in the UK’s public-facing priorities for COP26 as it is not a discrete topic for negotiations at the summit.18 However, both government officials and external stakeholders suggested that progress on this commitment will be seen as a test of the UK’s credibility on the climate and environment agenda as the COP26 co-president (with Italy). A number of FCDO staff in the overseas network commented that Paris alignment was all the more important given risks that the credibility of the UK’s leadership at COP26 could be compromised by the decision to reduce the percentage of gross national income provided as ODA (from 0.7% to 0.5%) temporarily (although International Climate Finance was protected).

Box 4: International climate finance and making all finance flows consistent with climate goals

There is no globally agreed definition of climate finance. The UNFCCC Standing Committee on Finance has defined it as “the financial resources dedicated to adapting to and mitigation of climate change globally, including in the context of financial flows to developing countries”.

Although all countries must take action to tackle the climate crisis, their respective responsibilities for past emissions and capacity to act are not equal. It is therefore a settled principle of international climate action that developed countries have an obligation to help finance climate action in developing countries. That is the role of international climate finance – finance flows from developed to developing countries dedicated to climate change adaptation and mitigation.

In 2009, developed countries committed to “mobilising jointly US $100 billion a year by 2020 to address the needs of developing countries. This funding will come from a wide variety of sources, public and private, bilateral and multilateral, including alternative sources of finance”. In 2021, at COP26, formal deliberations will begin on a new international climate finance goal. The current $100 billion target will serve as the annual floor for international climate finance until 2025, when the new (as yet not agreed) goal will be adopted.

With investment needs in developing countries far larger than current international climate finance flows, an important role of international climate finance is to mobilise funding at scale from other sources. Beyond this, there is also a need to align and shift the rules governing global and national financial sectors, and the real economy (the flow of goods and services) to support climate action. This is embodied in the third long-term goal of the Paris Agreement. It commits to “making finance flows [not just climate finance] consistent with a pathway towards low greenhouse gas emissions and climate-resilient development”. This long-term goal is global in application, and it refers to developed and developing countries, and private and public finance flows and stocks.

Climate finance is a key thread through climate change negotiations. There is a lack of consensus on what counts towards developed countries’ commitment to mobilise $100 billion a year, but by most assessments they are not on track to meet the original 2009 goal. This has led to tension, with some developing countries viewing the channelling of resources and efforts to ensure that all finance flows and stocks are consistent with the Paris Agreement goals (such as supporting financial transparency or fiscal reform) as detracting attention from the shortfall in much needed international climate finance dedicated to enable them to address climate change.

FCDO tools for Paris alignment reflect emerging good practice among donors, but uncertainties remain as to how the UK approach will evolve

The four tools mandated and elaborated by FCDO’s PrOF rule 5 guidance for new aid programming reflect emerging international good practice among aid providers.

The climate risk assessment tool determines how the physical impacts of climate change could affect programming, thereby minimising negative impacts on development projects. It is a tool that FCDO has applied previously and which is commonly used by development finance agencies.

The shadow carbon pricing tool applies a price to an FCDO programme’s expected direct emissions and emission reductions. This helps identify the economic costs and benefits of the change in carbon emissions resulting from the programme. It is referred to as a shadow price as it is not applied in practice, but is used to inform programming. A number of development finance institutions apply shadow carbon pricing, including the World Bank. However, not all of them do, and there is variation in the scope of emissions included (ranging from only counting direct emissions to including indirect emissions such as consumption of purchased electricity, extraction of purchased materials and fuels, transport-related activities and waste disposal).

The fossil fuel policy requires that any investment involving fossil fuels that affects emissions will need to be in line with the Paris Agreement temperature goals and transition plans. Specifically, “the UK government will no longer support the extraction, production, transportation, refining and marketing of crude oil, natural gas or thermal coal overseas, with limited exemptions”. It is a stand-alone, cross-government policy, as well as appearing as a tool in the PrOF 5 rule guidance. As such, it applies across all UK departments and includes wider investment, export credit and trade promotion activities overseas. It not only determines the UK’s voting position on projects at the boards of MDBs, but applies to the investment policies of other government departments and other development finance institutions receiving UK government funding. This includes CDC Group, the UK’s development finance institution, which has adopted a new fossil fuel policy aligned to the UK government policy. It also includes the Private Infrastructure Development Group (PIDG), an infrastructure development and finance organisation funded by the UK, the Netherlands, Switzerland, Australia, Sweden, Germany and the International Finance Corporation of the World Bank Group.

Alignment with countries’ Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) and National Adaptation Plans (NAPs) is the fourth tool. With the adoption of the 2015 Paris Agreement, multilateral climate negotiations have shifted towards a country-driven approach rather than a top-down, target-setting one. Countries are required to define their own pathways to low-emission, climate-resilient economies. A country’s short-term goals – often considered to be 2030 – are articulated in their NDCs. Parties to the Paris Agreement are also invited to provide longer-term strategies (LTSs) stretching to 2050. The NAP is the newest process to identify medium- and long-term adaptation needs as well as developing and implementing strategies and programmes to address those needs.

The UK’s approach to Paris alignment of ODA continues to evolve. The September 2020 FCDO Climate and Environment Smart Guide suggests the four alignment tools described above are likely to represent “a minimum description”, with the possibility that additional tools may be introduced. Through interviews, we identified additional tools that the UK could be using as its approach to Paris alignment evolves and deepens, including:

- Applying a taxonomy at the level of individual activities, to categorise how different economic activities relate to adaptation and mitigation. A taxonomy can include positive and negative listings of Paris-aligned or misaligned activities. The fossil fuel policy is to some extent a negative list and similar policies could be developed in other climate-sensitive sectors to guide aid spending. The EU, for example, has developed a green taxonomy with technical annexes outlining screening criteria for particular sectors (such as agriculture and forestry) and their contribution to adaptation and mitigation. Eventually mandatory disclosure, using this taxonomy, will be required for certain products and offerings within the EU financial sector.

- More detailed metrics on emissions. These can include setting emission intensities or standards to particular technologies or sectors. The European Investment Bank (EIB), for example, couples shadow carbon pricing in economic assessments with an emissions performance standard which sets limits for the allowable emissions from a particular source of power generation in its lending criteria.

- Conditional assessments – in the guidance for the UK’s four tools, references are made to ‘credible’ plans to address climate change in a particular sector, as well as to an understanding of the risks of stranding assets (a change in conditions that reduces the value of infrastructure or other assets prematurely). The development of specific criteria to identify what constitutes a credible plan, or how a stranded asset can be defined, can be particularly useful in sectors where Paris alignment is highly dependent on policy context (such as agriculture and forestry). Conditional assessments can determine if programmes should be considered aligned or misaligned depending on specific attributes of the project or the country context. For example, electrified transportation can be considered aligned if the electricity sector is on track with decarbonisation.An example of conditional assessments is CDC’s additional guidance for deciding whether to make investment in gas infrastructure. The International Energy Agency is clear that supply and demand for natural gas must fall to meet Paris Agreement temperature change goals. However, gas is often seen as a transition fuel away from coal and oil, before countries can transfer their energy systems to renewable sources. To guide decision making, CDC has five asset-level indicators that consider the technology, the operating regime and the energy source being displaced by the project. Six system-level indicators consider the country’s wider energy transition pathway, and a final indicator for transition investment risk considers the project’s exposure to reputational and other risks to the value of the investment.

- The assessment of a country’s wider policy context for Paris alignment. This includes considering the alignment of aid beyond the NDCs, which generally only cover the period to 2030 and often contain high-level objectives rather than specific sectoral goals, to countries’ LTSs to 2050 and subsidiary strategies. It also includes looking at energy policies, transport sector policies and wider development and economic growth strategies, which France’s development agency (AFD) does.

In July 2021, it was clarified that FCDO would review the PrOF rule 5 supporting guidance, exemptions and implementation arrangements within a year. The fossil fuel policy is expected to be updated every two years. There is less clarity on how tools will be monitored and adjusted in light of best available science and emerging best practice.

The early climate risk assessment required for Paris alignment is only a first step towards identifying the risks presented by climate change

The FCDO guidance on climate risk assessment notes that the guidance is not designed to be comprehensive. Instead, it is intended to lay out a proportionate approach to climate risk assurance. It presents a four-step process for considering climate risks: in the concept note, when the business case is developed, in programme design, and during implementation, as deemed necessary.

The first two stages of climate risk assessment, concept note and business case, are to be undertaken by programme teams. Guidance suggests that these are ‘high-level’ and do ‘not require detailed consideration of climate information’. If significant climate risks arise, a full climate risk screening must be undertaken. Little guidance is given on how to undertake climate risk assessments at each level, but numerous links are provided in the guidance to further assessment tools. We understand that FCDO also intends to produce regional climate risk reports to support aid programming.

This multiple-step approach risks programmes progressing without climate risk management embedded in their design. It focuses on identifying risks rather than reducing their incidence. FCDO appears to be aware of this limitation, with a more strategic approach deemed necessary to ensure that adaptation and resilience is central to early design, rather than a bolt-on.

Determining a shadow carbon price is complicated and resource-intensive; an estimated 70% of programmes are currently exempt from having to do so

How best to set a shadow price for carbon has been the object of cross-government discussion. It requires that programme designs include an estimation of the programme’s emissions, as well as a baseline and a counterfactual emissions scenario (what would have happened in the absence of the programme). These require an understanding of emission estimation methods. The ultimate cost-benefit analysis is highly sensitive to the choices of discount rate (estimating in today’s value the cost of emissions in the future), as well as of the ultimate carbon price to use. Internal discussions have focused on which price to use and whether to use a blanket price for ease, or if it should differ by sector and country and over time. The UK uses the shadow carbon price set by the cross-government Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy (BEIS) carbon value series. Comparison between institutions of the carbon price applied is difficult due to differences in price progressions over time as well as in their scope of application.

The PrOF rule 5 guidance includes a number of exceptions to the application of carbon pricing in FCDO programme development, including for: business cases for less than £10 million, programmes operating solely in low-income countries, programmes operating solely in extremely fragile countries, and FCDO programmes delivered through multilateral organisations. Furthermore, only programmes in certain sectors will apply carbon pricing (water supply and sanitation, social services and infrastructure, economic infrastructure, production sector, environment protection, and development planning sectors). Together, these exceptions suggest that less than 30% of FCDO ODA requires any form of carbon pricing.

We were told by FCDO that the current methodological choices and exemptions for shadow carbon pricing are a function of the administrative burden relative to change in emissions. FDCO notes that it currently prioritises applying shadow carbon pricing to high-emission programmes and will reduce exemptions to cover more of UK aid over time. The vast number of exemptions sends a mixed signal about the UK’s commitment and coherence in applying shadow carbon pricing, particularly given its role as a grant donor (as opposed to a lender) and therefore its critical role in supporting a transition to a low-carbon future.

The development of a government-wide fossil fuel policy is widely welcomed, but there is insufficient guidance on how to determine exemptions to this rule

The process of creating a UK fossil fuel policy was initiated in December 2020 and went through a process of public consultation. The policy was not applied retrospectively given the significant operational, financial and reputational impacts on CDC and PIDG, and the value of UK ODA investment in each of these. Exemptions to the fossil fuel policy on a case-by-case basis can be considered in: humanitarian response, projects that assist decommissioning of existing fossil fuel assets, and stand-alone diesel generators and liquefied petroleum gas for cooking and heating “until the transition to renewable fuels is feasible”.

The UK’s fossil fuel policy has been widely welcomed by external stakeholders. However, we heard concerns from civil society about exemptions, particularly on supporting gas. While guidance suggests that conditions for supporting gas should include the country having a credible plan for reducing emissions in line with the Paris Agreement and no danger of the programme delaying or diminishing a transition to renewables or risk of stranding assets, FCDO programme officers do not have guidance or criteria for how to assess this.

Aligning aid with developing countries’ national climate planning processes is critical

The Green Finance Strategy (2019) speaks specifically to NDC alignment, and the PrOF rule 5 guidance and associated Climate and Environment Smart Guidance goes further and refers both to countries’ NDCs and to their NAPs.

Alignment with developing countries’ NDCs and NAPs is necessary for the UK to meet its Paris alignment commitment, but it is not sufficient, for the following reasons:

- Many countries’ NDCs are not Paris-aligned. The aggregate impact of the first round of NDCs was found not to limit warming to within 2°C above pre-industrial levels. The Paris Agreement includes a ‘ratchet mechanism’ for Parties to assess, review and improve their NDCs every five years to ensure progress in climate ambition over time. However, after the first update period, NDCs still collectively fell short of the 2°C target.

- NDCs do not necessarily consider the deep, long-term transitions needed across sectors to reach Paris alignment. Long-term strategies, extending to 2050, would be helpful to consider in this regard, particularly for funding that goes beyond a largely grant or concessional approach (such as MDBs’ infrastructure programmes with long lifespans). Not all countries have long-term strategies in place, however.

- Many countries lack resources and capacity to articulate detailed climate action plans. A country’s NDC and NAP may therefore omit a deep understanding of the sectoral transitions needed, as well as their costs and financing needs.

- The NDCs do not always include adaptation objectives. FCDO’s recent inclusion of NAPs in Paris alignment tools is therefore welcome, as NDCs have predominantly focused on mitigation. Not all countries have an NAP, however.

FCDO is aware of the limitations of the NDC alignment tool. In its communication with MDBs (see paragraph 4.71), the UK highlights the potential, when detailed country plans are not available, to use proxy measures to create scenarios aligned with the Paris Agreement’s objectives for particular sectors such as energy, transport and land use. There is currently no guidance on how to manage this within UK bilateral aid programming, although the UK is clear that its own Paris alignment of ODA “must reflect different country contexts and development pathways”. This points to a tension between aligning with country plans on the one hand, and with the goals of the Paris Agreement on the other, since country-determined pathways may not be compatible with the long-term mitigation and adaptation goals of the Paris Agreement or with its objective of achieving a 1.5°C future.

Currently, the UK does not apply positive selection tools or a portfolio-wide approach to supporting developing countries in their pursuit of Paris alignment

The four programme-level tools outlined in the PrOF rule 5 guidance focus on minimum requirements and ‘do no harm’. The fossil fuel policy and climate risk assessment tools work to avoid transitional and physical climate risks in ODA programming. Shadow carbon pricing makes the carbon cost of programme actions visible. Each of these tools is geared towards screening out high-emission or high-risk options, but none of them are designed to encourage a systemic shift towards low-emission, climate-resilient options. The NDC and NAP alignment tool in its current articulation focuses on avoiding going against country plans, but not on directing funding towards supporting those country plans.

There is no tool through which programmes can be positively selected (as opposed to screened out) to promote the goals of the Paris Agreement. The lack of positive selection tools contradicts the consensus that Paris alignment of finance flows must go beyond a ‘do no harm’ approach and support low-emission and climate-resilient development directly or indirectly, focusing on co-benefits and transformative outcomes. A ‘do no harm’ approach is not sufficient considering the speed at which climate change mitigation and adaptation actions must be accelerated to reduce severe adverse impacts of global temperature rise.

To move beyond a ‘do no harm’ approach would mean addressing Paris alignment not only in the context of individual programmes. The alignment approach would also need to be applied at portfolio (especially country portfolio) level and at the level of overarching strategies, in order to promote low-emission, climate-resilient development across all ODA activities. Actively shifting countries towards Paris alignment was put on the UK’s agenda when it became the first major economy to combine a legally binding 0.7% aid target with a commitment to align support for developing countries with the Paris Agreement, including ramping up medium-term targets at the country level. This requires a country portfolio approach that is (i) supported by an overall strategy setting the direction for all UK aid across all departments, reflecting good practice in guiding country engagement, and (ii) adapted and relevant to the particular challenges and needs of individual developing countries, thus ensuring ownership of the Paris alignment process by developing countries.

A portfolio- and strategic-level approach covering all UK ODA would help ensure that Paris alignment of ODA is not perceived solely as the responsibility of the FCDO Climate and Environment Directorate, but as a task for all aid-spending departments. There is, however, no timeline for the UK to get to this stage of portfolio and strategic approaches (see paragraph 4.47).

The UK government will need to work with developing countries to ensure that Paris alignment does not come to be considered mainly as green conditionality

There is a danger that the Paris alignment approach to date may be considered by developing countries as a conditionality on ODA. In interviews, some FCDO teams noted that some national partners had voiced discontent about the UK’s fossil fuel policy – particularly about finance for gas. Ruling out gas would be seen by some developing country partners as restricting their development options. Interviewees noted the need to be careful not to create a sour taste in the pursuit of Paris alignment, and that the UK needs to retain a development perspective in order to avoid being seen as hectoring developing country governments who might argue that the UK could do more at home.

The UK could do more to support developing country partners’ efforts to update or implement their NDCs and to integrate climate change into other national planning and budgeting processes and financial systems. The importance for donors of supporting the development of NDCs, then aligning behind them, is widely acknowledged. Articulating country-specific needs is critical to understanding the different transition pathways that countries will take. It would also help FCDO in determining where exemptions to its programme-level Paris alignment tools are appropriate and where they are not.

What exactly is needed to support Paris alignment will differ by country. It is likely to include a combination of technical assistance and support as partners endeavour to understand and undertake transformational sectoral shifts, including support to address the transaction costs of conducting these shifts (embedding a just transition for the workforce). Many developing countries have tied their climate ambition to the provision of international climate finance. Some countries’ NDCs have dual targets, with the most ambitious ones conditional on the receipt of climate finance mobilised by developed countries.

The UK government could pre-empt, through its public communications, the potential risk that efforts to achieve Paris alignment of ODA are conflated with the endeavour to provide international climate finance to developing countries

The alignment of ODA with the Paris Agreement is not the same as providing more international climate finance. The main purpose of climate finance is to serve as an essential catalyst to enable transition to low-carbon and climate-resilient development. Financing such transitions at scale will require aligning all ODA as well as all other financial flows with the Paris Agreement goals. Hence commitment to Paris alignment of ODA should not diminish or replace the commitment to provide climate finance, but rather build upon and amplify the impact of climate finance.

It would therefore be useful for the UK to distinguish pre-emptively between the roles and responsibilities – and ultimately the impacts – that are being sought through the Paris alignment of aid versus the provision of aid that is programmed as international climate finance, explaining their differences and interlinkages in public communications.

There are gaps in the Paris alignment of UK ODA and nuances in how FCDO applies its alignment tools. A significant proportion of UK aid is largely reliant on implementing organisations’ own efforts to achieve Paris alignment

The PrOF rule 5 guidance is the primary route through which FCDO staff in the UK and overseas understand and interpret the changes they need to make in day-to-day operations as a result of the commitment to align ODA with the Paris Agreement. Other aid-spending departments need to establish their own governance on aligning their ODA. FCDO has been actively sharing the PrOF rule guidance with other aid-spending departments, engaging in ‘teach-in’ sessions and encouraging other departments to make use of the guidance. We found, however, that other aid-spending departments did not have guidance on Paris alignment in place. An exception was BEIS, which is in the process of assessing how to align international support for clean energy transitions with related policies on Paris alignment and government international support for fossil fuels. BEIS has also been strongly engaged in the development of the PrOF rule 5 guidance, primarily in formulating the fossil fuel policy and shadow carbon pricing guidance.

Some departments did not consider their role in this commitment to be important due to their lower levels of ODA spending, or spending on activities considered to be at low risk of Paris misalignment. However, this may be changing. For instance, the Department of Health and Social Care recognised that while it was relatively new to ODA (only spending aid funds since 2015), it needed to start thinking about Paris alignment now, in time for the next round of programming.

The lower level of engagement in Paris alignment of departments other than FCDO mainly reflects their lower volumes of aid spending. The merged and restructured FCDO will likely spend around 80% of UK ODA in the financial year 2021-22. While Paris alignment guidance for departments with small ODA budgets may be light, there is nevertheless an obligation to ensure that Paris alignment is coordinated across all UK aid-spending departments in order to deliver on the UK commitment. Guidance could provide, for example, environmental criteria and codes of conduct for contractors or implementers. It could also cover ODA purchasing decisions, introducing the aim to reduce climate impacts and support climate resilience in all of the government’s purchases of goods, services and works (especially in catering, transport and construction). This is aligned with the UK Climate Change Committee’s 2021 cross-cutting recommendation to ensure that all departmental policy and procurement decisions are consistent with a net-zero emissions goal and reflect the most recent understanding of climate risks.

In the case of FCDO itself, PrOF rule 5 is designed to be applied to all FCDO programming. There is PrOF rule 5 guidance for bilateral programme development, while multilateral spending, including core contributions and trust funds, will need to comply with PrOF rule 5 but is treated differently. Within FCDO there is substantial reliance on multilateral institutions’ own processes. An annex in the PrOF rule 5 guidance directs Programme Responsible Officers to seek information on the approach of the partner institution, but the rule exempts programmes delivered through multilateral organisations from shadow carbon pricing. We were told that the business case – a document which scopes, plans and costs projects – acts as the gatekeeper for multilateral spending, in that the business cases for UK-funded multilateral programmes are required to show how the multilateral spending will comply with PrOF rule 5. The business case must show how the spend complies with the fossil fuel policy, that climate risks have been assessed and that the spending is aligned with NDCs and NAPs. This implies that UK aid spent through multilateral channels will be largely reliant on the multilaterals’ own processes (for example, shadow carbon pricing will only be used if the multilateral institution makes use of the tool).

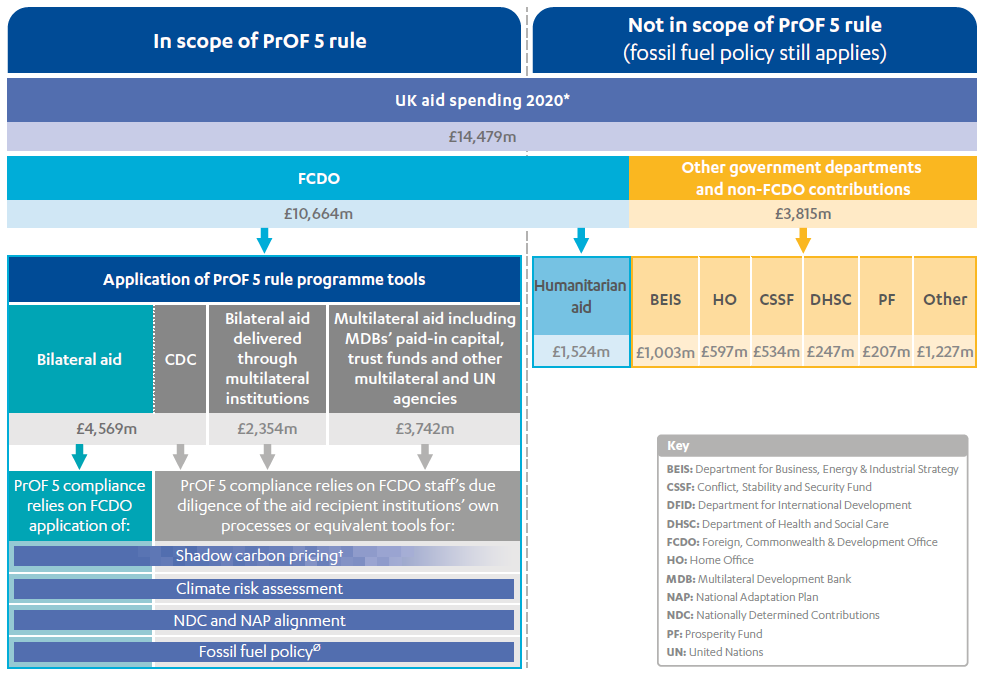

Figure 1 below uses ODA figures from 2019 to illustrate which types of spending would fall under the four Paris alignment tools. The exercise suggests that a large portion of ODA might not be covered by FCDO application of the tools, but is exempt, not applied, or reliant on the processes of the institution receiving UK aid.

Figure 1: Illustrative representation of the scope of FCDO’s PrOF rule 5 and how the current Paris alignment tools would have been applied to the UK’s 2020 ODA spending

The PrOF rule 5 came into force in April 2021. This figure hypothetically applies the rule and the four tools outlined in its guidance to UK aid spending in calendar year 2020 to demonstrate their scope and application. Source: Statistics on International Development: Final UK Aid Spend 2020, September 2021.

During the course of 2020, former DFID and FCO merged to form FCDO. The two departments spent £10,046 million and £618 million of UK aid, respectively.

Exemptions to the FCDO application of the shadow carbon pricing tool include: bilateral spend in lower-income countries, bilateral spend solely in extremely fragile states, bilateral spend under £10 million, bilateral spend in sectors that are not considered to produce high greenhouse gas emissions and multilateral

aid spending. Programmes delivered through multilateral organisations are exempt from shadow carbon pricing as per the PrOF 5 rule guidance annex, represented by the shading (see 4.37).

Exemptions to the application of the fossil fuel policy are made on a case-by-case basis (for instance, support for gas is conditional on a credible emission reduction and transition plan (see 4.20). In cases where FCDO is a board member or shareholder, application can also be expressed through voting rights for fossil fuel policy.

Box 5: CDC’s approach to Paris alignment of ODA

As a public limited company, CDC is owned by the UK government but managed as an arm’s-length development finance institution. Its day-to-day operations are overseen by, but independent of, government. FCDO investment of new capital to CDC was £780 million in 2021 (although there have been reports of a 42% cut). FCDO’s bilateral ODA spending through CDC is required to be compliant with all PrOF rules, including PrOF rule 5 on Paris alignment of UK aid.

We have been told that the head of the Private Sector Department’s development finance institutions team is the senior responsible officer accountable for CDC’s compliance with the PrOF rules. This happens through annual meetings, reporting frameworks and informal day-to-day contact between CDC and FCDO teams. There are therefore assurances of compliance through the approaches that CDC itself is taking towards Paris alignment. CDC employs a form of physical climate risk assessment and works to align investments with NDCs and other national planning processes. It also has a fossil fuel policy, with conditional alignment taking into account wider policy and regulatory commitments for gas, and it makes use of a carbon budget as a key portfolio-level tool. While it does not employ shadow carbon pricing, CDC believes that its application of a carbon budget and multi-criteria analysis serves a similar purpose of screening out high-emission options in a manner appropriate to its investment context.

CDC’s mandates differ from UK ODA programmed through other routes and so the approach to Paris alignment is not directly comparable. CDC’s approach to Paris alignment is set out in its July 2020 Climate Change Strategy, where it commits to “invest for a net-zero world” by 2050 and states that all portfolios and activities will align with the Paris Agreement. It is potentially a more ambitious approach than FCDO’s. It takes both a portfolio approach and a project approach, so that the portfolio approach does not allow for misaligned projects to be offset by aligned projects. CDC does not have a date by which it plans to be fully Paris-aligned, but it intends to have a portfolio with net-zero emissions by 2050.

In a time of crisis and transition, the UK government has been slow to begin implementation of its commitment to align aid with the Paris Agreement

In June 2019, former prime minister Theresa May delivered a speech promising to “put the UK at the forefront of climate action at the G20, by committing that all UK aid spend will support the transition to lower greenhouse gas emissions”. Specifically, she pledged a “commitment to align support for developing countries with the Paris Agreement”. The UK’s Green Finance Strategy, published in July 2019, further committed to “explore initiatives to accelerate alignment to the Paris Agreement”, and align “the UK’s official development assistance (ODA) spending with the Paris Agreement”.

After the onset of the COVID-19 crisis and subsequent aid reprioritisation in March 2020, the cut to the aid budget in July 2020 and the merger of the FCO and DFID at the beginning of September 2020, the FCDO Climate and Environment Smart Guide was completed later that month. The guide gave prominence to the “landmark commitment” to align ODA to the goals of the Paris Agreement, and outlined (but did not mandate) the basics of climate risk assessment and shadow carbon pricing.

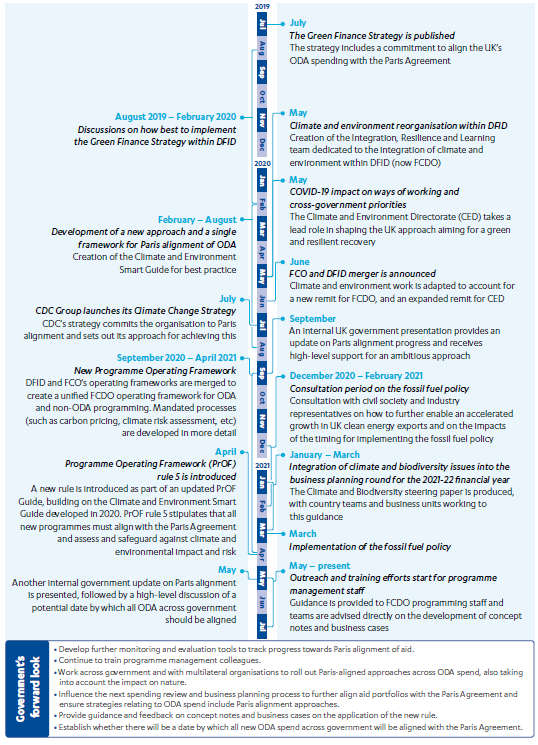

The Climate and Environment Smart Guide was superseded on 1 April 2021 by rule 5 of FCDO’s new Programme Operating Framework (PrOF). It therefore took 21 months from the announcement of the commitment to the mandatory application of PrOF rule 5 in the FCDO programme cycle. The cross-government fossil fuel policy, which senior staff noted took significant consultation to complete, came into effect in March 2021. A timeline of UK action on the commitment to Paris alignment can be found in Figure 2 below.

Figure 2: Timeline of actions operationalising the commitment to align UK aid with the Paris Agreement

Aid-spending departments outside FCDO are still in the process of putting plans and guidance in place for Paris alignment of ODA. It was explained to us in interviews that other aid-spending departments have their own accounting officers appointed by the Treasury (accountable to Parliament) and that this reporting system cannot be overridden by other departments, including by the foreign secretary’s oversight role of most UK aid.

An acceleration of action has been observed in recent months. This includes FCDO outreach to overseas FCDO staff and other government departments as well as discussions on setting a target date for the Paris alignment of UK aid in the Climate Change National Strategy Implementation Group (NSIG).

There is not yet a roadmap for how the UK government will develop its approach to aligning UK aid with the Paris Agreement

PrOF rule 5 sits at programme level and is applied in FCDO business cases developed from April 2021 onwards. FCDO acknowledges in its guidance that more work needs to be done to shift the focus on Paris alignment upwards to the portfolio level, and then the strategic level, so that climate action is pursued throughout programming, with the intention that:

- Programmes “must demonstrate their environmental impact to inform design and operational decision making to ensure no harm is done”.

- Portfolios “must balance a range of programmes in the pursuit of low-carbon development on aggregate, minimising activity with negative impacts whilst acknowledging that the pursuit of low-carbon, or zero-emission, development approaches must be balanced with broader international commitments to delivering the Sustainable Development Goals”.

- Overarching strategies “must set a direction that ensures consistency across portfolios, and ensure [government] has the right people and skills in place to support their delivery, as well as progressively raising ambition across all activity”.

The PrOF rule 5 guidance indicates that portfolio alignment is to be considered by the heads of department. In 2020, guidance was issued by FCDO’s climate and environment director to support country-level portfolio planning and provide teams with a more strategic set of parameters for the autumn 2021 Spending Review. Examples given of strategic parameters were ending the use of coal for electricity in Asia and making agriculture resilient in sub-Saharan Africa.

The measures to build a portfolio and strategic approach to Paris alignment have been described as interlocking. The approach will need to accommodate and be compatible with various other commitments in multiple strategies and roadmaps that guide ODA spending, including emerging targets to ensure that ODA is nature-aligned, in the sense that it does no harm to nature. We have been told that developing the approach may involve a number of other strategies and plans, including:

- The new International Development Strategy, led by FCDO, which will set out the UK approach to international development for the next decade, ensuring that UK aid is closely aligned with the objectives of the Integrated Review. The call for evidence lists climate change and biodiversity as one of seven key priorities for UK ODA.

- An updated International Climate Finance (ICF) Strategy, first developed in 2011 for what was then the International Climate Fund.

- FCDO’s Sustainability Action Plan for 2021-2025, which will set out FCDO’s targets and actions to make operations more sustainable.

No target date for Paris alignment of UK aid has been agreed yet. Nor is there a roadmap with explicit prioritisation of spending departments and ODA channels, alignment milestones and minimum standards. This absence is in stark contrast to the UK’s demand that MDBs set a date to be Paris-aligned. However, this demand does reflect that UK ODA cannot be aligned until the MDBs are aligned (see paragraph 4.71 on UK demands on MDBs).

Staff capacity and capability appears insufficient to deliver Paris alignment of UK aid

FCDO has calibrated its alignment efforts to the resources it has available and recognises the need to continue to train and equip staff with the skills necessary to achieve its ambition to align all aid with the Paris Agreement. As such, it is useful to consider the capacity of staff (their available resources, predominantly in the form of time) as well as their capability (the skills and knowledge needed) to implement the UK commitment.

A number of FCDO teams are involved in the Paris alignment of UK aid, including:

- Climate and Environment Directorate: integration, resilience and learning team; international evidence, engagement and strategy team; Green Growth team; environment and biodiversity team.

- International Financial Institutions Department: climate and environment team.

- Private Sector Department – engagement with the private sector.

- International Energy Unit – leading on fossil fuel policy.

- UK Delegation to the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development’s Development Assistance Committee (OECD-DAC) – UK as part of a bilateral DAC donor group.

- UK board members and their alternates in the major multilateral institutions, including the World Bank, the Asian Development Bank (ADB), the African Development Bank (AfDB), the Inter-American Development Bank (IADB), and climate funds including the Climate Investment Funds, Green Climate Fund, and Global Environment Facility.

No evidence was provided on the number of hours or resources devoted specifically to Paris alignment. We were told, however, that FCDO capacity is already overstretched at the central level. This will have implications for ongoing efforts to develop and operationalise the portfolio- and strategy-level approaches to Paris alignment, since the currently active teams do not have capacity beyond fielding questions on how to implement the current programme-level commitments in the design and development of new aid programmes.

In the case of the FCDO overseas network in developing countries, there are both capability and capacity gaps in teams’ ability to deliver on PrOF rule 5. FCDO is less likely to have capability gaps in countries where it already has a strong engagement in climate change than in countries where there has been less focus on climate action. Clear examples are FCDO staff in Bangladesh and Colombia, who welcomed the Paris alignment commitment and PrOF rule 5 as being in line with priority objectives in the country.

Overseas teams flagged that they were reliant on specialist climate and environment advisers, who may or may not be based in country, and that this resource was already constrained before the programmed increase in climate spending and introduction of PrOF rule 5. Most staff in the overseas network were positive about the Paris alignment commitment, but since only a few have developed business cases since April 2021, most have not yet gone through the process of applying the alignment tools (while they may previously have developed projects that constitute climate finance).

Climate risk assessment and shadow carbon pricing are complex in both their methodology and application, and there appears to be insufficient capability in the overseas network to deliver these PrOF rule 5 tools widely. Even where detailed climate risk assessment is conducted as a part of the programme delivery itself, sufficient capacity and capability are crucial at the design stage to ensure that suitable terms of reference for the programme are drafted and work can be realistically assessed for appropriateness and coherence.

There is central support available which overseas teams can use. At present, the level of demand is unclear, which means it is uncertain if this draw-down capacity will be adequate when PrOF rule 5 is rolled out for new programmes. Support can be sought from:

- Climate and environment advisers – around 60 ODA-funded advisory posts at the Climate and Environment Directorate. FCDO is aware that it will need more climate and biodiversity analytical capability across the department if it is to deliver the government’s ambitions on climate and biodiversity.

- The Climate Mainstreaming Facility – predominantly for climate risk assessments. The facility provides technical assistance for up to 15 days based on requests. It has funding until the end of the 2021-22 financial year and could reduce pressure on overseas teams. However, use of the facility requires tendering and therefore sufficient pre-existing understanding of climate risk assessment to write terms of reference. Then, once a team receives the facility’s assessment report, a level of expertise is required to use the results of the assessment.

- Economic advisers – advice from economic advisers could be sought on carbon pricing, but we are not sure that many economic advisers already have relevant expertise and training to support with carbon pricing assessments.

Alongside ODA-funded staff in the overseas network, FCDO also has a cadre of climate, energy and environment attachés (462 people, equivalent to 190 full-time roles)70 delivering on COP26 and UK climate and biodiversity objectives overseas. These attachés are paid from a non-ODA funding allocation within FCDO. While these attachés have not necessarily engaged with ODA programming, we were told that their understanding of climate change issues and engagement with developing countries would probably mean that they had skills which could be used to ensure Paris alignment of UK aid.

There are doubts about the capability of other aid-spending departments to deliver on the Paris alignment commitment. FCDO is in the process of carrying out ‘teach-in sessions’ for PrOF rule 5 that include other government departments. We have not confirmed the exact number of these sessions, but this outreach and training effort has yet to reach senior management in other government departments. The target is for Paris alignment to be a ‘whole of ODA issue’, applied across all aid programming, rather than a ringfenced ‘climate issue’. This requires knowledge and skills transfer both to specialist cadres (such as economists or infrastructure advisers) and to generalists.

In the run-up to COP26, the UK has built up significant climate change capacity, including in its COP26 Cabinet Office unit. However, this is a time-limited team that will not continue over the year-long duration of the presidency. While this additional climate change capacity has been highly focused on COP26 preparations, it could be an important resource if harnessed to further Paris alignment.

Lines of accountability for progress on the Paris alignment commitment are unclear

Officials were unable to clarify the line of reporting on Paris alignment or who is ultimately responsible for meeting this commitment. The foreign secretary appears to be the minister responsible for ensuring the cross-government Paris alignment of UK aid. Since the last Spending Review, the department now has, in some respects, oversight of most UK ODA. However, FCDO is not able to seek compliance from other government departments with its PrOF rule 5, since this would cut across accounting officers’ responsibilities (see paragraph 4.42).

How responsibility for the commitment is carried across government and through the various FCDO committees and boards is acknowledged by officials in FCDO to be a work in progress. There are several internal FCDO boards and committees. At the highest level, there is a cross-government Cabinet Committee on Climate Change, supported by a cross-government senior officials’ group (National Strategy Implementation Group (NSIG)) that oversees decision-making on both international and domestic climate change mitigation and adaptation.

Monitoring and reporting mechanisms for Paris alignment are unclear, and there are no learning processes in place

It remains unclear to FCDO staff how the UK commitment to align aid with the Paris Agreement is to be assessed and reported. It does not appear that Paris alignment is included in the 2021-22 Outcome Delivery Plan – a new approach to measure progress towards priority outcomes in the Spending Review across government. In interviews, we heard conflicting views on whether or not the UK was planning to introduce a key performance indicator (KPI) on Paris alignment. Creating the metrics for such a KPI would not be easy. A multidimensional KPI would be required to account for the fact that Paris alignment does not look the same in all countries. Investing in measurement and metrics for Paris alignment of aid is urgent, as it will be harder to retrofit as the Paris alignment processes evolve.

Few donors have provided, or plan to provide, such measurements or metrics. The desire to avoid Paris alignment becoming a tick-box exercise is understandable, but the absence of robust reporting hinders the ability of the government to track progress over time, identify weaknesses in its approach, or build on good practice. The lack of transparency about measurements and metrics for Paris alignment is also problematic from the point of view of public accountability. The UK is in a position to invest more in exploring and developing an approach for monitoring progress on Paris alignment given the level of attention it usually pays to the monitoring and evaluation of its ODA spending.

Compliance at the country level with PrOF rule 5 is proposed to occur through the annual ‘Director’s Statement of Assurance’, the same system used for compliance with gender and safeguarding policies. Aggregate responses from posts are received by the central control and assurance team (which sits in the Finance, Commercial and Delivery Division in the Corporate Directorate). Directors will then have to provide assurance that PrOF 5 has been applied. This places responsibility on the heads of mission to self-certify their programmes as Paris-aligned. This self-certification may be subject to audit, as with any aspect of ODA programming. However, it is an internal assurance process and results are not externally published, which precludes accountability through public scrutiny.

As an arm’s-length body, CDC does not report officially to FCDO on Paris alignment (see Box 5). CDC has some transaction-level processes for ensuring compliance with its own Paris alignment commitment (for example confirmation in Investment Committee papers that investments are Paris-aligned). From an FCDO perspective, portfolio oversight occurs through assurance meetings with committees and through CDC board engagement. A new reporting framework is underway to reflect the new investment policy that guides the CDC 2022-2026 strategy. This may include relevant elements to Paris alignment, but it remains up to the FCDO programme responsible officer to report on the PrOF rule, rather than CDC.

The line of reporting for multilateral ODA is understandably different, due to the pooling of funds and the complexity in attributing spending to individual country contributions. Paris alignment of UK multilateral aid therefore relies on these institutions’ own efforts. The UK can exert pressure on the institutions through its role as shareholder or board member.

It is only when the MDBs that the UK contributes to are Paris-aligned that all UK ODA will be Paris-aligned. It is acknowledged that full Paris alignment may be an elusive target in the short term. The cross-government fossil fuel policy is currently the only one of the four Paris alignment tools that is directly applied to MDBs’ activities by FCDO staff through voting rights (indirectly, FCDO staff are required to ensure that MDBs have processes which are in line with PrOF rule 5 – see paragraph 4.37). The UK tracks its MDB voting decisions applying the fossil fuel policy and has abstained on some votes since this commitment was introduced. The UK voting record on MDB boards is not made public, however, and it is not clear how it might ultimately feed into any reporting or public accountability for the commitment.

The UK is also reliant on institutions’ own processes for Paris alignment for ODA spending through multilateral trust funds. The same is the case for bilateral ODA programmed through multilateral partners where the UK government specifies the purpose of the funding and in some cases the recipient (known as multi-bi assistance). We were told that compliance with the tools of Paris alignment would need to be identified through due diligence for each multilateral partner. We have not seen any examples of business cases for spending through multilateral channels since PrOF rule 5 has been mandated, however. It therefore remains unclear how Paris alignment of aid spent through multilaterals will be assessed in practice. Figure 1 provides an indication of the scale and proportion of this type of ODA flow compared to bilateral ODA.

The risk of Paris misalignment is lower for some of these multilateral institutions, particularly those working towards climate change goals. Checks nevertheless need to be put in place. We found no evidence of UK engagement in, for example, actively pursuing Paris alignment of the activities of the Food and Agriculture Organisation of the UN, GAVI the vaccine alliance, the Global Fund for Tackling AIDS, TB and Malaria and the International Fund for Agricultural Development.

Public information is lacking on the UK’s progress towards Paris alignment of ODA. Civil society organisations have no information on the UK processes or the guidance for each tool (except for the publicly available cross-government fossil fuel policy). No external stakeholders interviewed had been consulted in processes leading up to the Green Finance Strategy or the subsequent design of the Paris alignment guidance in FCDO.

A public narrative on the UK’s progress towards its commitment was planned in advance of COP26 but is likely to be delayed. The delay may, in part, be due to sensitivities of some stakeholder groups who consider Paris alignment of aid to be a distraction from the setting and meeting of climate finance commitments in developing countries (see paragraph 4.5).