UK aid’s approach to youth employment in the Middle East and North Africa

Score summary

The Middle East and North Africa (MENA) is a region of considerable strategic importance to the UK. A number of UK strategy documents note that high youth unemployment across the region is a potential source of instability. While there is no overarching strategy for promoting youth employment in the region, there is a substantial amount of related programming, including support for economic development, education and training, and livelihoods for Syrian refugees and their host communities.

The main focus of the relevant portfolio in the region is on promoting economic stability and growth, through macroeconomic reforms and improving the business environment. We find this to be a relevant and credible approach, given the weak performance of national economies in creating jobs. However, there are some assumptions in programme design documents, particularly on the links between employment creation and fragility, that are not supported by the evidence. Better use of evidence and more direct engagement with young people would improve programme design.

There is a good level of coherence across the UK actors involved in this area, but we noted variation in the technical depth available across UK embassy teams, and the portfolio would benefit from more interdisciplinary working, particularly between economists and conflict specialists. We found that policy dialogue with national governments was limited, as was donor coordination. While the choice to work through multilateral partners such as the World Bank makes good sense, the UK, on occasion, acted purely as a funding partner, without contributing substantively to programme design or quality.

Evidence of effectiveness across the portfolio is also limited, due to a combination of programme design limitations and insufficient attention to monitoring and evaluation. Nevertheless, support to the private sector, for both entrepreneurs and small enterprises, has been successful, cash-for-work programmes have helped generate short-term jobs in crisis situations, and skills programmes have achieved their intended results, albeit in small numbers. However, the larger programmes, including those focused on ensuring that refugees have access to work permits, have not been so successful in creating jobs. Economic reform programmes were not accompanied by complementary interventions to ensure impact for target groups, and the portfolio would benefit from taking a more evidence-based and problem-solving approach. Evidence of wide variations in the cost-effectiveness of programmes suggests that this also needs closer attention. While women were commonly targeted by programmes, the results on inclusion were not well delivered, partly due to a bias towards male- dominated sectors of employment and insufficient attention to gender norms.

As a result, the portfolio has been less effective than planned in meeting job creation goals, including for women and vulnerable groups. We therefore find that the UK’s approach to youth employment in MENA merits an amber-red score.

Executive summary

Across the Middle East and North Africa (MENA), almost half the population of 448 million is under 25 years of age1 and five million young people enter the workforce each year. Youth employment is a major challenge across the region: around a quarter of young people are unemployed, compared with 14% globally. Young women are particularly affected. As well as being a brake on the region’s economies, youth unemployment is often considered to be a driver of fragility and social unrest in the region. This review considers how well UK aid has supported youth employment in MENA since 2015.

The UK does not have an explicit focus on youth unemployment in the region, but the challenge is mentioned across various strategy documents, including country strategies, and there is a wide range of relevant programming. Since youth unemployment has multiple causes on both the supply side (the skills of young people) and the demand side (the capacity of national economies to generate jobs), our review covered a range of intervention types, from support for broad economic reforms to skills development, labour market interventions and support for refugees’ rights to work. Altogether, we identified 115 programmes with objectives that are directly or indirectly related to youth employment. The programmes were managed by the Foreign and Commonwealth Office (FCO) and the Department for International Development (DFID), now merged into the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO).

The review explores the relevance, coherence and effectiveness of the UK’s work in this area. The methodology involved a literature review, desk reviews of a sample of 19 programmes, two country case studies (Jordan and Tunisia), engagement with stakeholders in Turkey, Egypt and Lebanon, and consultations with young people expected to benefit from UK programmes.

Youth unemployment is a complex challenge with no simple solutions. Our literature review (published separately) sets out the evidence of which types of interventions are likely to be effective in different contexts, and how the design and packaging of interventions can enhance results. We use this evidence as a yardstick to review the UK’s approach.

Relevance: Is the UK’s approach to promoting youth employment in MENA relevant to needs?

The UK government has not set any specific, region-wide objectives for UK aid on youth employment. However, a range of government strategies and analyses of the region link instability and fragility with underlying economic grievances, especially unemployment, and UK aid strategies in particular MENA countries, including Jordan, Egypt, Lebanon and the Occupied Palestinian Territories, highlight the importance of youth employment.

Across the region, the UK has promoted job creation by supporting reforms designed to improve the enabling environment for business and increase economic growth, as well as by supporting more direct job creation efforts. This is a relevant and credible approach, as the literature confirms that barriers to youth employment across the region are principally on the demand side, linked to a failure of national economies to generate quality jobs on the scale required. However, we also identified significant investment in skills training (the supply side), which is a poor match to the needs of the region and inconsistent with the literature on ‘what works’. The British Council, for example, supports a range of ‘employability skills programmes’ but does not monitor their effectiveness in helping young people gain employment.

There is substantial UK investment in support of Syrian refugees and their host communities in Jordan, Lebanon and Turkey, in order to meet humanitarian needs, reduce tensions and limit secondary displacement. This includes activities that support the employment of young people, including ‘cash-for-work’ programmes and advocacy for their rights to work through provision of work permits. We found that this area of programming was well tailored to the needs of young people in refugee and host communities.

While the UK’s approach was broadly relevant, some key employment needs of young people were not being addressed. We did not find any significant effort to tackle cultural barriers to youth employment, especially for women, which are prevalent across the region. An example is UK support for labour market participation in Jordan, via the World Bank, which backed legal reforms to enable part-time working and improve access to public transport and childcare. Jordan has one of the world’s lowest rates of female participation in the labour force. While these were relevant and useful measures, they had no significant impact on female labour force participation, partly because underlying social norms and cultural barriers were not tackled. This was acknowledged by the UK, but no relevant programming was introduced to address the gap.

The UK’s focus on formal employment risks missing the needs of many young people, women, refugees and other vulnerable groups who are active in the informal labour market. We also found gaps in the approach with regard to non-Syrian refugees (such as Iraqis), rural youth and people living with a disability (only two programmes in our sample had an explicit disability focus).

Around half of the programmes had consulted young people, but this is not standard practice and consultation feedback does not always shape programme design, despite the commitment made in DFID’s 2016 Youth Agenda to incorporate young people’s voices and concerns into all aspects of programming.

Some good analytical work is being undertaken, including through UK support to the World Bank. However, this analytical work does not always shape programme design or contribute to building up the evidence base. Fewer than half of the programmes we reviewed referred explicitly to underlying analysis or diagnostic work relating to young people or youth employment. The Arab Women’s Enterprise Fund was a positive exception, with a robust approach to generating and using evidence. Other programmes were based on theories of change that were not evidence-based. Examples included unrealistic assumptions about when Syrian refugees would return to Syria, the willingness of host governments to promote jobs for refugees and the likelihood of policy reforms leading to economic growth and job creation.

While half of the programmes in our sample cited reducing fragility as an objective, the evidence linking job creation for young people and improved political or social stability is weak, and the impact of the programmes on fragility is not being monitored or assessed. In particular, a link between youth unemployment and violent extremism is often assumed in donor programming, but is not supported by the evidence. Only two of the 19 programmes in our sample (in Lebanon and Yemen) had attempted to monitor changes in community attitudes; both found a positive impact on social cohesion.

Overall, despite these gaps and weaknesses, we find the UK’s approach to addressing the youth employment challenge in the region is relevant to the challenges found in particular countries, with some good examples of diagnostic work and consultation with young people. We therefore award a green-amber score for relevance.

Coherence: How coherent is UK aid’s approach to promoting youth employment?

There is a good level of coordination across the UK departments working in this area, with shared strategies and complementary programming. This close coordination predates the DFID-FCO merger and is likely to be further enhanced by the forthcoming cross-government MENA strategy 2021-2030 which, we are told, will include region-wide objectives on security, prosperity and resilience, with a focus on economic growth and job creation.

However, coherence has been undermined by a lack of cross-disciplinary working between specialists in economic development and conflict issues, and by marked differences in technical capacity between country offices with a strong contingent of former DFID staff and those without. Programming by some non-DFID funding sources, including the cross-government Conflict, Stability and Security Fund (CSSF) and British Council funds, showed evidence of poor coordination and knowledge management. One non-DFID programme (a combination of Prosperity Fund, CSSF and Global Britain financing), the UK Lebanon Tech Hub project, received over £3 million of funding, but FCDO was unable to provide complete documentation for it within the review period. In some instances, we found that institutional knowledge of the portfolio was inadequate and, in one case, that the responsible staff lacked the technical skills to exercise effective oversight.

UK engagement with donor coordination is surprisingly limited, given that coordinating and influencing partners is often an explicit objective from FCDO. We also found the UK’s approach to policy dialogue with national governments to lack clear objectives and well-considered approaches.

The UK does better in its engagement with multilateral partners, particularly the World Bank. This prioritisation makes sense, given the Bank’s influence in the region and its technical expertise on economic reform in general and youth employment specifically. The UK has used trust fund contributions strategically to influence much larger World Bank loans, and the flexible nature of this funding was valued by the Bank, especially in the context of the COVID-19 crisis. The UK has also been innovative in providing guarantees in support of World Bank loans, which enable the Bank to scale up its finance. However, we found that the UK was not always engaged in influencing programme design and implementation substantively, even where its influence on programme design was a stated driver of the value for money that it expected to achieve. Overall, the feedback from multilateral partners was that the UK preferred to focus narrowly on programme management, rather than enter into strategic partnerships. This is reflected in the high turnover of UK staff, poor institutional memory and lack of technical depth in some country teams.

Due to these important gaps, we have awarded an amber-red score for the coherence of the UK’s approach.

Effectiveness: How effective is the UK’s support to youth employment in MENA?

We found only limited evidence that the portfolio has delivered results, in terms of jobs for young people. Across the intervention types, we found relatively weak youth employment results for the large refugee-focused programmes, a lack of outcome-level results data on wider reform programmes, some successful interventions to support entrepreneurs and small and medium-sized enterprises (although at high unit costs), strong but inevitably short-term results from cash-for-work programmes and some small-scale successes from skills training. At portfolio level, the results are modest for the size of investment, and suggest that an effective approach to identifying and overcoming the barriers encountered by young people is lacking. However, there are positive exceptions, such as the Arab Women’s Enterprise Fund, which were more effective.

Monitoring, evaluation and learning systems were inadequate in a number of respects – not least a tendency for evaluations to be delayed or missed and for outcome indicators not to be monitored. The reliance on unrealistic assumptions noted above was exacerbated where the assumed effects were not routinely monitored. Underinvestment in learning meant that failures to achieve objectives were identified too late to inform course correction. While few programmes took a rigorous approach to measuring cost-effectiveness, the figures available suggest a very wide range in costs per job created. While such comparisons are only indicative, they suggest that the UK should pay more attention to cost-effectiveness questions to identify interventions demonstrating poor value for money. The UK could also be doing more to strengthen the evidence base in this area.

Programmes prioritise women more frequently than young people, but in most cases social inclusion goals stated in business cases are not translated very effectively into programme design and implementation. We found many examples where project annual reviews had repeatedly recommended action on gender, without follow-up. A focus on male-biased employment types and a failure to target cultural barriers to female inclusion are key reasons behind weak employment outcomes for women.

We also found that jobs created across the portfolio were either not sustained, or that sustainability was not monitored. This is, however, a common issue with active labour market programmes, rather than one that is specific to the UK’s portfolio.

Overall, we awarded an amber-red score for effectiveness, reflecting a limited set of employment results from the programmes we sampled and relatively poor results data, alongside failings in delivering on gender and social inclusion objectives.

Recommendations

While youth employment has not been a major priority for UK aid in MENA, a significant number of programmes include objectives around employing young people in the region. With the forthcoming UK government MENA strategy expected to emphasise economic growth and job creation, it is important to learn lessons from past programming. We offer a number of recommendations to help shape the new strategy and improve the impact of future growth and job creation programmes, and also to strengthen multilateral partnerships, which we expect also to be relevant in other sectors and regions.

Recommendation 1: Employment-related programmes should articulate clearly how they expect to contribute to job creation and economic development or address fragility, and ensure that these outcomes are monitored and evaluated.

Recommendation 2: When promoting employment through economic reform, FCDO should undertake complementary interventions to tackle the specific barriers to employment faced by target groups.

Recommendation 3: Employment-related programmes should be shaped by gender and social inclusion analysis, including of cultural barriers to the employment of women.

Recommendation 4: FCDO should routinely consult with the young people expected to benefit from its MENA programmes and use the feedback to shape programme design and implementation.

Recommendation 5: FCDO should strengthen its in-country partnerships with multilateral organisations by ensuring consistent strategic-level engagement.

Introduction

The Middle East and North Africa (MENA) is a region of considerable strategic interest to the UK. The March 2021 Integrated Review includes the objectives of promoting a more secure region, based on open, inclusive and resilient societies. With one of the youngest populations in the world, a key challenge that will need to be tackled is youth unemployment, which averages 23% among 15 to 24 year olds in the Arab states, compared with 14% globally. Youth unemployment limits economic growth in the region and, although the links between these issues are complex, is also commonly perceived to be a driver of fragility and a potential cause of social unrest, radicalisation and irregular migration.

We therefore undertook a review of how well UK aid promotes youth employment in MENA. While UK aid to the region does not focus explicitly on youth employment, it includes a range of related objectives on economic development, education, and support for refugees and host communities. We identified a total of 115 programmes in the region with objectives that related to youth employment either directly or indirectly. As a measurable outcome, youth employment offers a yardstick against which to assess the overall effectiveness of this support.

The review encompasses UK aid programmes in MENA active since 2015 that make a potential contribution to youth employment. The largest of these are humanitarian programmes supporting the more than five million Syrian refugees in Jordan, Lebanon and Turkey, which include livelihoods components. The programming covers Iraq, Jordan, Lebanon, the Occupied Palestinian Territories, Syria, Turkey, Yemen, Algeria, Egypt, Libya, Morocco and Tunisia. Most programmes were delivered by the Department for International Development (DFID) and the Foreign and Commonwealth Office (FCO), before they were merged into the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO) in September 2020.

The review explores whether this portfolio constitutes a credible and coherent approach to the complex issue of youth employment, and how effective it has been in generating employment for young men and women and in contributing to economic development and stability. Our review questions are set out in Table 1. 1.5 The findings chapter explores the review questions in three sections:

- Under ‘relevance’, the degree to which the portfolio is responsive to needs, its balance of economic development and fragility-related objectives, and how it has drawn on evidence and consultations with young people to inform programming.

- Under ‘coherence’, how well the UK’s programmes and policy influencing efforts are coordinated across the responsible departments and with other partners, including host governments, donors and, critically for this theme, multilaterals.

- Under ‘effectiveness’, the results achieved by the portfolio, including how many jobs have been created, the value for money achieved, specific outcomes for women and vulnerable groups, and the degree to which results have been sustained.

While the UK does not have an explicit strategy or approach for promoting youth employment in the region, we are informed that the forthcoming cross-government MENA strategy 2021-2030 will include a renewed emphasis on economic growth and job creation. It is important for lessons from the UK’s experience so far, including those we present here, to inform future efforts.

Table 1: Our review questions

| Review criteria and question | Sub-questions |

|---|---|

| Relevance: Is the UK’s approach to promoting youth employment in MENA relevant to needs? | • Is UK aid’s approach to promoting youth employment responsive to the context? • To what degree does the UK government’s approach to youth employment aim to reduce drivers of fragility and conflict? • How well is the UK’s programming aligned with the needs and priorities of the young people expected to benefit? • To what extent are UK aid programmes based on good evidence and learning on ‘what works’, and contributing to further evidence? |

| Coherence: How coherent is UK aid’s approach to promoting youth employment? | • How well is the UK’s work on youth employment in the region coordinated across departments? Is the overall approach coherent? • How well has the UK worked with multilateral and other development partnersto promote youth employment in MENA? |

| Effectiveness: How effective is the UK’s support to youth employment in MENA? | • How well has UK aid contributed to youth employment in the MENA region, and to what degree have the UK’s efforts supported the goals of economic development and reducing fragility? • How well do UK aid programmes on youth employment deliver on gender and inclusion objectives in MENA? • Where UK aid has contributed to improving employment outcomes, how well have they been sustained or how likely are they to be sustained? |

Methodology

Our methodology comprised five core elements:

i) Strategic review: We mapped relevant policies, strategies and guidance on the UK’s approach to youth employment in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA), and consulted with key stakeholders, including UK government staff, academic experts, civil society (at UK, regional and country levels) and other development partners, on their relevance and coherence.

ii) Literature review: We reviewed the published literature on youth employment. We looked at evidence on ‘what works’ (and ‘what doesn’t work’) regarding youth employment interventions in the MENA region and explored the links between youth employment, conflict, extremism and migration. The literature review is published separately.

iii) Programme reviews: We chose a sample of 19 programmes and projects to assess in depth, including desk reviews of programme documents and key informant interviews. Annex 1 details the programmes selected.

iv) Country case studies: We prepared case studies of the UK portfolio in Jordan and Tunisia. These involved reviews of country-specific strategies and analysis, and week-long ‘virtual country case study visits’ to interview the responsible UK officials, programme partners, national counterparts, civil society and other donors. We also conducted ‘enhanced stakeholder engagement’ in Turkey, Egypt and Lebanon, where we interviewed a range of national stakeholders.

v) Youth voice: We consulted with a small sample of young people intended to benefit from UK support, through virtual interviews and focus groups, in Jordan, Tunisia and Yemen. We also reviewed the views and perspectives of young people in MENA, collected within UK aid programmes and from published sources, to capture a broader range of views across the region. These consultations offered a platform for young people to raise their concerns, while enabling us to triangulate and contextualise results reported by the programmes we reviewed. A summary of the feedback is included in Annex 2.

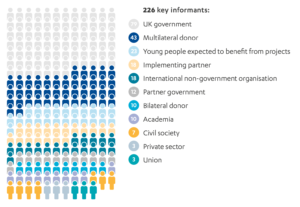

Overall, the review included 121 interviews with 226 key informants, including four focus group discussions and 12 interviews with young people from the region, and analysis of over 530 documents. Further details of our methodology, including our sampling approach, can be found in our approach paper.

Figure 1: Breakdown of key informants by category

Box 1: Limitations to the methodology

- Many of the programmes we reviewed contained multiple objectives, and youth employment outcomes were not always monitored or separately identified in programme reporting, leading to gaps in results data. Lack of data has made it difficult to draw firm conclusions on whether the results of UK aid programmes are sustainable or represent value for money.

- We have not conducted an audit of the portfolio and cannot guarantee that the programmes reviewed meet safeguarding requirements in their dealings with young or vulnerable people or UK government rules on the management of fiduciary risk.

- COVID-19 has impacted our review in two ways. First, the pandemic required us to conduct our stakeholder consultations and youth engagement remotely, which hampered our ability to collect a representative range of views. Second, it has significantly impacted the growth and jobs context of the MENA region, and therefore the likely impacts of programmes in recent years will have been significantly curtailed. We have considered the performance of programmes pre-pandemic to prevent bias in the results.

Background

Youth unemployment in a volatile region

Almost half of the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) population of 448 million is under 25 years of age and five million young people enter the workforce each year. Since 1991, the region has had the highest youth unemployment rate in the world, at around 23% of those aged 15 to 24, compared with 14% globally. The problem of unemployed and disaffected young people was highlighted during the ‘Arab Spring’ – a wave of popular unrest that swept the region from 2011. Ten years on, the economic grievances that are thought to have triggered that unrest remain unresolved. In Tunisia, where the first uprising began, the tenth anniversary of the Jasmine Revolution in January 2021 brought young people back onto the streets, protesting against inequality, spiralling unemployment and governance failures.

A high proportion of unemployed young people in the region are well educated, with university graduates making up nearly 30% of the total.16 As discussed in the literature review, there is a mismatch between the expectations of educated young people, who seek scarce public service or professional jobs, and the low-status and poorly paid work generally available in the private sector. A striking feature of labour markets across the region is the low rate of female participation. Women face a range of legal, institutional and cultural barriers to working. In Jordan, for example, the female labour force participation rate is just 14.6%, compared with 61.2% among men.19

The youth unemployment challenge has complicated causes. It is linked to a failure of national economies to generate quality jobs in sufficient numbers, due to factors such as the dominance of the public sector, weak business environments and a lack of access to finance. These are commonly described as ‘demand-side’ problems. There are also challenges on the ‘supply side’: educational systems leave many young people without the skills they need to compete for jobs. This means that the range of potential programming options is wide. Our approach paper outlines a typology of youth employment interventions on both the demand and the supply sides, which has guided our analysis.

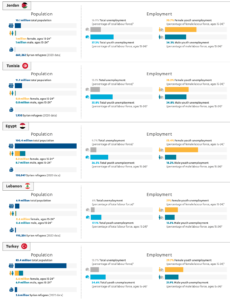

Figure 2: Population and youth unemployment dynamics in sampled countries (2019)

Box 2: Voices of young people on MENA labour markets

Our consultation with young people seeking to enter the labour market, including refugees, in Jordan, Tunisia and Yemen, identified six common concerns:

Education: The skills they receive from the education system do not match the needs of the job market. Connections, or ‘wasta’, in Arabic: Getting a job depends on who you know. This poses particular challenges for refugees.

Social norms and expectations: Young women face significant social barriers in gaining access to the labour market, and women are expected to take on a high burden of unpaid work in their households.

Lack of voice: Young people feel that they have no channel through which to raise their concerns with government, and that government is uninterested in their views.

Low trust in institutions: Young people are unwilling to engage with public institutions, citing corruption as a concern. This was particularly the case in Tunisia, where public trust has been undermined by frequent changes in government.

‘Waithood’: Young people, particularly university graduates, often wait for a long time after graduation – some suggested up to the age of 35 – before they are able to gain employment and become full members of society, partly due to waiting for preferred public sector roles. This period is marked by frustration and a sense of stagnation.

The region is also characterised by high levels of conflict and political instability, which have severely disrupted economic growth over the past decade. Lebanon today demonstrates the devastating social and economic effects of instability. The country has been rocked by anti-government protests since October 2019, linked to a serious economic crisis and the collapse of the currency. The COVID-19 pandemic left 75% of the population in need of financial assistance. The Beirut port explosion in August 2020 has exacerbated the economic crisis and fuelled popular anger against a divided and allegedly corrupt political elite.

Young refugees face additional challenges. Access to work permits is often restricted. In Jordan, and elsewhere in the region, Syrian refugees are only granted permits for work in a limited number of occupations, although many work informally.

Across the region, fragility has been exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic. In 2021, national health systems are under heavy strain. Lockdown measures have severely disrupted national and regional labour markets and caused sharp economic contraction. The Tunisian economy – already struggling before the pandemic – shrank by 8.2% in 2020. In Yemen, COVID-19 has added another layer of complexity to the already devastating conflict that has engulfed the country since 2014, causing the economy and basic services to collapse and leaving 80% of the population dependent on humanitarian aid. The delivery of international support to Yemen, including from the UK, has been disrupted by the pandemic and aid cuts, leading to worsening famine and loss of life.

The pandemic has deepened the underlying patterns of marginalisation of young men and women across the region. While national economies will begin to recover as vaccination programmes progress, many young people will face a further reduction in the economic opportunities available to them over the longer term. While manifesting in different ways across this diverse region, disaffection among young people is likely to be a pressing challenge for policymakers in the years ahead.

What works in promoting youth employment?

There is a substantial body of literature looking at the effectiveness of different types of interventions on youth employment. The evaluation evidence suggests that youth employment programmes can have a positive effect on both employment rates and earnings, but the effects are generally relatively small. Evidence on the effect of wider economic reforms on youth employment is inconclusive, as reform programmes do not generally measure their impact on employment, let alone youth employment, partly for technical reasons. It is also rare for youth employment programmes to continue to monitor their effects on target populations after completion, which means there is limited evidence on whether results are sustained over time.

The literature suggests that programmes are more effective when they target disadvantaged youth and women directly and when employers are involved in programme design, implementation and evaluation. Youth employment programmes also appear to be most effective when part of a package of interventions, working simultaneously on the barriers to job creation (demand side), upskilling young people (supply side) and improving the national policy environment. However, the literature is also clear that ‘what works’ is often context-specific. Some of the key lessons are summarised in Box 3.

Box 3: A complex picture of ‘what works’

The evidence on the effectiveness of youth employment programme categories is mixed, complex and context-specific. Although there is no ‘silver bullet’, and results will be context-specific in all cases, our literature review28 reaches the following high-level conclusions:

i) General reforms to the business climate are likely to benefit young people, but there is no systematic evidence of impact on youth employment.

ii) For refugees and migrants dependent on work permits, interventions to facilitate access and increase the duration of permits can improve employment outcomes.

iii) Subsidies to employers for hiring young workers can have a positive impact on target groups in the short term, particularly in middle-income countries, but they are expensive and tend not to result in overall net employment gains (that is, the young people who benefit displace older workers).

iv) Programmes promoting entrepreneurship, including through access to credit, have had a positive impact on youth employment in middle-income countries. They are more likely to create jobs where credit is combined with skills training and mentorship, when targeting small and medium-sized enterprises rather than micro-enterprises, when targeting existing rather than new businesses, and when the support is long-term in nature.

v) Information services and schemes matching jobseekers with potential employers appear to have only small effects on employment. Involving the private sector in the design and delivery of such programmes, and combining them with training and placement support, can improve outcomes.

vi) There is limited evidence that direct job creation schemes, such as public works programmes, promote short-term or sustainable youth employment outcomes. Displacement effects are high.

vii) Skills training may increase productivity but usually does not affect overall employment levels. To improve impact, the training needs to be high quality and relevant to the needs of the private sector. Accreditation of skills is important.

The Department for International Development (DFID) surveyed the available evidence to produce guidance on ‘best buys’, or the most cost-effective interventions, ranked by strength of evidence. Broadly, it concluded that measures to promote economic growth in general are also the best way of creating jobs. This aligns with findings from our literature review, our interviews with economists and other experts, and our analysis of the portfolio. It also identified two ‘bad buys’: wage subsidies (economic incentives to firms to employ more workers) and technical and vocational education and training (TVET) are both shown to offer poor returns on the investment. Cross-country studies suggest that TVET programmes in particular rarely generate employment results.

UK aid objectives and programming relating to youth employment

The UK government has not set any specific, region-wide objectives for UK aid in relation to promoting youth employment in MENA. However, a range of government strategies and analyses of the region link instability and fragility with underlying economic grievances, particularly unemployment. The 2015 National Security Strategy, a key strategy document during our review period, states that creating jobs and economic opportunity is one of the measures the UK will pursue to tackle conflict and instability around the world. UK aid strategies in individual MENA countries, including Jordan, Lebanon and the Occupied Palestinian Territories, highlight the importance of youth employment. In its 2016 Youth Agenda, DFID also made an overarching commitment to work with young people as agents for development and to include their voices and concerns in all aspects of its work. The Youth Agenda noted that the global economy would need to generate 600 million new jobs for young people between 2016 and 2030 – a significant challenge.

To identify relevant programming for review, we developed a typology of interventions that potentially contribute to youth employment, including through interventions in the labour market, direct job creation or measures aimed at improving the enabling environment (see Table 2). Using this typology, we identified 115 programmes in MENA with a total value of £2.4 billion that include activities relevant to youth employment. Among these, documentation for 60% of the programmes outlined a primary or secondary focus on either youth or employment, with the remainder having a less clear focus on the theme. 20% of the programmes identified focus explicitly on youth employment. While these programmes include a wide range of other objectives, we assessed them only in terms of their contribution to youth employment. The portfolio includes both demand-side activities, such as wage subsidies, support for entrepreneurship and improving information about job availability, and supplyside interventions, such as the certification of skills and the promotion of employability skills. We did not cover broader education.

Table 2: Share of the youth employment in MENA portfolio by intervention type

| Category of intervention | Examples of types of interventions | Percentage share of portfolio value |

|---|---|---|

| Programmes to reform the enabling environment | 59% | |

| Active labour market programmes | Programmes that incentivise employment | 26% |

| Interventions which support entrepreneurship | 25% | |

| Programmes to expand labour market information services | 6% | |

| Programmes that provide direct job creation | 27% | |

| Education and skills development programmes | Programmes which provide skills for employability and certification | 36% |

Findings

Relevance: Is the UK’s approach to promoting youth employment in MENA relevant to needs?

Although there is no UK youth employment strategy for MENA, growth and employment creation have been prioritised through UK programming

UK aid has no explicit strategy on youth unemployment, either globally or in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region. However, it does have a strong focus on economic development, which accounted for around 20% of all global bilateral aid in 2019. As identified by the Department for International Development’s (DFID) own ‘best buys’ analysis, creating jobs through economic development programming is directly relevant to young people. This is particularly true for MENA given the region’s age distribution which is skewed towards youth.

More specifically, youth employment has been prioritised consistently in some country and subregional strategies, including in Jordan, Egypt and North Africa, between 2016 and 2021. In North Africa, programming in recent years has been overseen by a combined DFID and Foreign and Commonwealth Office (FCO) Joint Unit. Its business plan highlights the importance of economic development to stability in the region and includes among its priorities the creation of jobs, particularly for women, youth and other marginalised groups. In Jordan, economic resilience is one of the main focus areas of the UK’s work, with a main goal of job creation through structural reform and inclusive economic growth. Jobs for youth is a priority outcome emphasised under the most recent business plan for the DFID portfolio. In Egypt, the UK’s smaller programme has a high degree of focus on job creation, including the inclusion of youth and women. In Tunisia and Turkey, where youth employment is not prioritised specifically, the programmes emphasise economic growth and private sector development, both of which are relevant to the youth employment challenge. Even in Lebanon, where the UK, like other donors, is focused on crisis response, this has included the creation of jobs and support for small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs).

Consistent with these priorities, we found a large portfolio of programmes in the region with objectives or activities relevant to youth employment. A combined £2.4 billion has been invested in 115 programmes which include activities related to youth employment in the region since 2015. Most of these tackle multiple objectives and the share of expenditure related to youth employment is not recorded separately in the aid statistics. The portfolio includes both economic development and education programming as well as projects supporting direct job creation, entrepreneurship support and employability skills training. We examined a sample of 19 programmes with specific employment objectives in their design documents. Of these, three listed youth employment as their primary objective and another five had youth employment, or employment in general, as a secondary objective. We find that, despite not having an overarching strategy, the employment-related programmes and accompanying partnerships and policy dialogues demonstrate that the UK has prioritised employment creation in the region.

Within the portfolio, job creation initiatives are more relevant than skills development

The core challenge of youth employment in MENA is a lack of jobs. For the most part, the case for demand-side interventions, which seek to expand employment opportunities, is stronger than that for supply-side interventions, which seek to improve the skills and capacities of young people so they can compete for jobs. Although there are skills gaps across the region, the general level of education is relatively high.

The literature suggests that integrated efforts are most effective in promoting youth employment and tackling the demand and supply of labour, as well as linking to policy advocacy. However, across the 19 programmes we reviewed, only two took an integrated approach that combined policy advocacy with supply- and demand-side interventions. These two stronger examples were the regional Arab Women’s Enterprise Fund (AWEF, DFID, £10.3 million, 2015-2020) and the Palestinian Market Development programme (PMDP, DFID, £14.0 million, 2013-2018).

The priority is achieving alignment between supply and demand and, in the MENA context, it is the job creation side that needs support. In some countries, particularly Jordan and Egypt, we found the UK’s efforts to be directly relevant to this challenge, seeking to address underlying or structural constraints to job creation. In both cases, the UK is supporting World Bank efforts to improve the enabling environment for business, which should contribute to a more vibrant private sector and more jobs.

We also found that the portfolio includes a substantial number of purely supply-side or training initiatives (a third of the portfolio by value – see Table 2) that are a relatively poor match to the needs of the region and the literature on ‘what works’. This point is recognised in DFID’s ‘best buys’ analysis, which highlights technical and vocational education and training (TVET) as a ‘poor buy’. For example, the British Council supports English language training across the region and we examined their programme in Tunisia (British Council Tunisia Programme, £5.7 million, 2018-2021). The British Council describes this as support for young people’s employability and lists job creation as an intended outcome. However, it does not monitor job creation and the evidence linking this kind of intervention to employment outcomes is weak. In Tunisia, the young people we spoke to found the UK’s focus on English language training to be relevant and useful, but of limited direct help in obtaining jobs.

Teaching English is always a good thing…but it doesn’t feel like a huge priority when it comes to employment. It’s as if we’re talking about getting a Ferrari when you don’t have a roof. Interviewee, CSO Tunisia

Stakeholders we interviewed, including other donors and civil society organisations (CSOs), suggested several reasons for the continued focus on standalone training programmes. Skills training programmes are easier to design and implement. They are also easier to ‘sell’ to national governments across the region, compared with programmes that tackle complex structural reforms or provide direct financing to marginalised groups. This contributes to a tendency for the UK and its partners to understand youth unemployment as a problem of ‘skills mismatch’, for which the default solution is training.

UK programmes in Jordan and Turkey are relevant to the employment needs of Syrian refugees and host populations

The UK made major investments between 2015 and 2020 through the aid programme in supporting Syrian refugees and host communities in the region, to alleviate humanitarian need, minimise tensions and limit secondary displacement. Much of this programming also tackled the employment and livelihoods needs of young people and women.

In Jordan, UK programmes have tackled constraints to the access of refugees, and women in general, to the labour market. The UK was an important voice in the negotiation of the Jordan Compact, an agreement between the government of Jordan and international development partners to grant Syrian refugees access to the labour market in exchange for substantial international support and improved access to the European market for Jordanian exports. Through the Jordan Compact Economic Opportunities Programme (JCEOP, DFID/FCDO, £217 million, 2016-2023) supporting the World Bank in particular, the UK has bolstered efforts to provide work permits for Syrian refugees. By providing a guarantee for the World Bank (DFID/FCDO, £0, with a contingent liability of £164 million between 2019 and 2054)40 and supportive technical assistance through the Jordan Investment and Economic Reform Advisory Programme (JIERAP, DFID/FCDO, £14.5 million, 2019-2023), the UK has helped to promote labour market reforms that improve women’s access to jobs – a major concern in Jordan with one of the lowest rates of women’s participation in the world.

In Turkey, the EU’s Facility for Refugees in Turkey (FRIT) programme to which the UK contributes (Phase 1, FRIT1, DFID, £288 million, 2016-2019 and Phase 2, FRIT2, DFID/FCDO, £141.3 million, 2019-2023) sought to manage tensions through delivery of services, including humanitarian, education, health, municipal infrastructure, social and economic support, targeting both refugees and host communities. In Lebanon, there is currently limited political space to work with government on economic reforms. Instead, UK programmes focus on easier targets, including direct short-term employment creation through Phases 2 and 3 of the Lebanon Municipal Services Programme (MSP, DFID, Phase 2, £15.3 million, 2017-2018 and Phase 3, DFID/FCDO and CSSF, £31.5 million, 2019-2021) and job placements through the Lebanon Enterprise Employment Programme (LEEP, DFID, £16 million, 2017-2020).

Some of the key employment needs of young people are not addressed

We did not find significant effort across the portfolio to tackle cultural barriers to youth employment, which are prevalent across the region (see Box 2). Although the issue is noted in the UK’s analytical work and design documents, this has not translated into programming. An example of the resulting gap is the UK support for labour market participation in Jordan, via the World Bank (the combined guarantee and JIERAP programme). The UK supported the government of Jordan in enacting legal reforms to enable part-time working and to improve access to public transport and childcare – all relevant and useful measures. However, there was no significant impact on female labour force participation, partly because underlying social norms and cultural barriers were not tackled. This was acknowledged by the UK, but no relevant programming was introduced to address the gap.

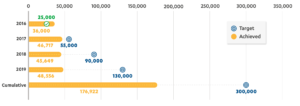

Another example was the UK’s support for work permits for Syrian refugees, through JCEOP. This programme combined UK support for several multilateral programmes, including World Bank programming targeting 300,000 work permits. The measure was less successful than anticipated, in terms of number of permits issued and jobs created, because of a combination of three factors: concern among refugees that they would lose UN benefits if they obtained work permits, restrictions imposed by the Jordanian government on refugees taking up certain occupations, and overambitious assumptions about the rate of overall economic growth. These factors are identified in UK programme documents, but no action was taken to adapt the programme to address them. Instead, the programme was extended and scaled up, from an initial £110 million (2016-2018) to £217 million (through to 2023). These work permit targets have not yet been reached as of the latest figures (see Figure 3).

Figure 3: Number of work permits targeted and achieved in Jordan

In both these cases, UK programming included relevant objectives, but lacked a systematic analysis of needs and how to address them.

Box 4: Meeting the needs of refugees

Although there is no universal refugee experience, our research pointed to common challenges around creating employment opportunities for refugees in the MENA region.

Refugees need the right to work: Syrian refugees in Lebanon and Jordan face difficulties in obtaining work permits, and are only permitted to work in particular sectors. There are political sensitivities in both countries related to extending their right to work. In Lebanon, the International Labour Organisation (ILO) reports that the main constraint to employment of refugees is the shortage of jobs “with decent working conditions in sectors that Palestinian refugees are legally allowed to work in.”

Without work permits, refugees face risky employment conditions: In the absence of work permits, refugees in Jordan are forced into precarious self-employment, exploitative working conditions and dependence on UN humanitarian aid. In Jordan, the refugees we consulted who were working informally faced a precarious existence, were vulnerable to arrest and often worked at night to avoid being detected by the authorities.

UK programmes focus on formal employment and risk missing the priority needs of young people, women, refugees and other vulnerable groups, who are typically active in the informal labour market. The need to engage with the informal sector was strongly expressed in our consultations with young people and other stakeholders in Egypt, Jordan and Turkey. In Turkey, for example, an estimated two million refugees currently work in the informal sector.

Finally, we found gaps in UK programming relating to specific vulnerable groups of young people, including non-Syrian refugees (such as Iraqis), rural youth and people living with a disability. We found only two programmes in our sample with an explicit disability focus: the Jordan Municipal Services and Social Resilience Project (MSSRP, DFID/FCDO, £17 million, 2016-2021) and the FRIT emergency social safety net component, which provided financial support to refugees based on disability criteria, although this is not employment-related.

There are good examples of programmes consulting with young people, but this is not systematic and does not always influence programme design

DFID’s 2016 Youth Agenda highlights young people’s role as both agents of and advocates for sustainable development. This innovative policy committed the UK to consulting young people directly and incorporating their voices and concerns into all aspects of its programming. This is a particularly important principle in the MENA region: CSOs and academics emphasised to us that young people lack a meaningful voice in public life, leading to a lack of trust in government, disillusionment with the democratic process and increased desire to migrate.

Just over half (ten out of 19) of the programmes we sampled had undertaken some form of youth consultation. Some country offices had also conducted needs assessments around youth employment, including in Jordan and Turkey, but these did not involve direct consultation with young people.

Donors like to talk about their priorities – in 2012 democracy, decentralisation, after that ISIS, peacebuilding, after that women’s empowerment. There are donors that respect priorities in the region and do their homework, and approach us and consult with youth groups in order to include it in their work. Female Algerian researcher, CSO

A positive example came from the Delivering the London Jordan Conference (DFID/FCDO, £2.4 million, 2018-2021), an international conference co-hosted by the UK and Jordanian governments to promote investment, jobs and growth in Jordan. In preparation, the UK worked with local civil society to consult with a diverse group of 186 young people to identify their priority needs and concerns related to employment. A report was written as background for the conference and ten young people were invited to attend the event. However, the organisation that facilitated these consultations told us that the UK did not follow up with the young people consulted after the conference, and that they did not receive the conference outcomes or any follow-up actions. It is clear therefore that despite the early engagement with young people, the UK did not close the loop on this engagement.

Other positive examples include MSSRP in Jordan, which supported the establishment of standing consultation mechanisms between local municipalities and citizens, including young people and refugees, and involved young people in monitoring. While there were some limitations to the quality of dialogue that was achieved, the programme did introduce a number of innovations in response to community feedback. In Lebanon, a similar initiative, MSP, included a participatory planning process and annual perception surveys, both of which involved young people and women. In Tunisia, we found a positive example of using focus groups to consult young people within the UK’s support to the Innajim project (part of the Tunisia CSSF Country Programme, FCO/FCDO, £47.6 million, 2015-2021). In Turkey, an updated needs assessment commissioned during the FRIT programme helped to reprioritise spending in accordance with refugee needs. Finally, the Social Fund for Development (SFD, DFID, £108.4 million, 2010-2018) in Yemen included a strong commitment to community consultation, in both prioritising needs and monitoring results, with a mechanism for receiving community complaints.

While there are good examples of consultation with young people, these were not systematic across the portfolio, and programming was not sufficiently consultative of young people overall. Only three of the ten programmes that consulted young people had done so during their design phase, for example to inform programme design. In Egypt, we found that there had been no consultation or other research into youth needs, despite relevant programming. It was particularly notable that some of the larger refugee support programmes in the region (such as FRIT and JCEOP) had not consulted widely with refugee groups during their design phase, especially as a lack of detailed understanding of refugee needs appears to have hampered their effectiveness. Young people who had benefited from UK-financed skills programmes told us that they were not consulted about changes to the approach or content of those programmes. As a result, they felt that the programmes were not adequately focused on their own priorities.

I think the problem is… not being clear about what students really need. Male Syrian participant in JCEOP training component

By contrast, some other donors were reported to have a more systematic approach to consultation with young people. The World Bank has a digital youth platform to allow young people in the region to interact with them and with local authorities. This feedback informs its country partnership frameworks. The Netherlands has a youth ambassador in Jordan to consult young people. UNICEF is working on establishing a formal mechanism for systematic and long-term engagement between donors and young people.

Some good analytical work is being undertaken, but it is not always used to inform programme design or build up the evidence base

Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO) country teams frequently conduct analytical or diagnostic work, including on youth employment issues, highlighting the importance of the issue in driving instability in the region, for example. FCDO also invests in research conducted by multilateral partners, including an £11 million contribution to the World Bank’s Jobs Umbrella multi-donor trust fund which carries out ‘job diagnostic’ studies around the world, including in Jordan, Turkey and Lebanon. The UK also helps to fund a World Bank centre of excellence on youth employment (Solutions for Youth Employment, S4YE). These programmes not only diagnose the youth employment challenges in each country but also help explore ‘what works’ in terms of solutions (see Box 3).

While there is good research available, the use of evidence underpinning programme design is variable. Only eight of the 19 programmes we reviewed referred explicitly to underlying analysis or diagnostic work relating to young people or youth employment, of which four were in Jordan. In Egypt, for example, although strong analytical work had been undertaken, we found no clear evidence that it had been used to inform strategy or programming. In Lebanon, although the annual perception survey and impact analysis financed by FCDO were of good quality, we did not find evidence that they were being used to inform the programme. In Turkey, there was a sophisticated monitoring and evaluation system for the FRIT programme, but it did not include sharing learning across implementing partners. The regional Arab Partnership Fund (APF, DFID, £110 million, 2011-2015) did not include substantive analysis of the youth unemployment challenge.

Overall, we found the transmission processes from research to programming were not very strong. One FCDO official told us that country-level analytical work is often undertaken by consultants and then “sits on the shelf without having meaningfully informed programming”.

Again, there were positive exceptions. AWEF took a robust approach to evidence. The programme was designed to generate credible evidence of the challenges facing women-led businesses in MENA, and the evidence cited in programme design documents on ‘what works’ in market-led economic empowerment for women was consistent with the findings of our literature review.

Poor use of evidence translated into some unconvincing causal assumptions in programme theories of change, which contradicted the literature, the results of consultations or monitoring data from past programming. One example of weak use of evidence was the UK Lebanon Tech Hub (UKLTH, FCO, £3.2 million, 2015-2018), which we were told was implemented at the behest of a former UK ambassador with an interest in technology and growth rather than being based on evidence or a needs assessment, and in an increasingly crowded tech incubator landscape in the country. Remarkably, FCDO was not able to provide any documentation relating to this programme during our research, so we were unable to triangulate the dates or financial spend. Subsequently, partial documentation was provided. Also in Lebanon, LEEP at first included unrealistic political assumptions, including on when Syrian refugees would return to Syria, the Lebanese government’s appetite to be seen to support refugee jobs, and on the wider geopolitical context (we saw the same issue in Turkey and Jordan). Finally, we found unrealistic economic assumptions, including those of the Jordan Compact and associated programming, which assumed that expanding access to the European market for Jordanian firms would create large numbers of additional jobs and enable the expansion of work permits for refugees. In practice, few Jordanian firms were able to expand their exports.

There is a focus on reducing instability, but this is based on limited evidence

UK aid documents commonly link youth employment-related interventions in MENA to the reduction of instability. Country-level analytical work in Egypt, Jordan, Turkey and Tunisia identifies youth unemployment as a driver of instability. In Egypt, for example, the UK theory of change links ‘idle youth’ to criminality. Within our sample of 19 programmes, seven described youth unemployment as a driver of conflict and fragility, while ten included the reduction of fragility as an objective. We found that design documents frequently contain untested assumptions linking unemployment and political disaffection.

The literature suggests that youth unemployment and instability are correlated, but that the causal links between them are weak, indirect and dependent on context. We found that programmes were slightly more nuanced than this, commonly referring to youth unemployment’s impact in damaging social cohesion (through competition for jobs) which, in turn, was expected to negatively impact stability. There is more support in the literature for this narrative, although the evidence base remains thin. There is little evidence linking youth unemployment specifically to violent extremism, although it has been seen to lead to migration and domestic violence. The mismatch between the expectations of educated young people in the MENA region and the opportunities available to them is also considered a source of frustration, but we found no evidence that this contributes to political instability. Academic experts working on the issue told us that links to fragility are often assumed by donor programmes, and expected to be seen in programme documentation to justify approval, but are not supported by the available evidence.

Another thing is lack of trust between young people and politicians and policymakers – we were given lots of promises but promises are not met – so that’s why we see a lot of protests here in Tunisia now. Female participant in Tunisia Young Mediterranean Voices project

In interviews, FCDO staff acknowledged the lack of evidence and some suggested further research on the topic. FCDO officials told us that internal incentives meant programmes were justified on multiple grounds to secure approval and the resulting language on stability could be “lazy”.

Given the thin evidence base on unemployment and instability links, we would have expected to see programmes with stability objectives monitoring for any causal effect, but this was not the case. For example, one Conflict, Stability and Security Fund (CSSF) programme in Egypt has a theory of change linking employment to increased household income and decreased crime, but these results do not feature in its logframe and are not monitored.

We did find two positive exceptions. The Lebanon MSP, implemented by the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), conducted annual perception studies on changes in community tensions, trust in government and intent to migrate. We understand from the UNDP that this FCDO funded research influenced the iteration of the overall Lebanon Host Communities Support Programme (LHSP, to which MSP contributes) and the UNDP’s wider programming effort. The results were also shared with other donors, such as KfW (a German state-owned investment and development bank), thereby reaching a broader audience. The Yemen Social Protection Programme (YeSP) included a study of the programme’s impact on social cohesion. This found a significant increase in participants’ trust in local government and leaders, as well as increased awareness of marginalised groups and improvements in cooperation between communities.

Conclusions on relevance

The UK government recognises that youth unemployment is a major challenge in the MENA region. Although there is no overall strategy governing the UK’s work on youth employment, the subject is frequently mentioned in strategy documents and analysis, and a range of relevant programmes have been implemented to further this goal in this area. The focus on the demand side ( job creation) is suited to challenges facing the region. However, the UK also prioritises skills training programmes, even though these are known to be largely ineffective, and has under-prioritised efforts to challenge cultural barriers to employment. Evidence to support the commonly assumed link between youth employment and stability is not convincing, and the relationship is not being monitored directly by programmes that rely on it.

We found some good examples of the UK consulting with young people through its programming, but this is not systematic. There was mixed performance regarding the use of diagnostic work and evidence on ‘what works’, resulting in some unconvincing programme choices.

Overall, despite these weaknesses, we find the UK’s approach includes relevant programming addressing some of the main youth employment challenges in the region, with some direct consultation of young people and some good diagnostic work. We therefore award a green-amber score for relevance.

Coherence: How coherent is UK aid’s approach to promoting youth employment?

There is strong coordination across the UK government

There is good coherence among the UK departments active in this topic and region, as a result of two main mechanisms: shared country-level national security strategies and co-located UK government teams in embassies across the region. All relevant parts of the UK government are represented, including the British Council and the UK’s development finance institution, CDC, which recently established a regional base in Egypt.

In Jordan, the single embassy team had been working together well for some time before the DFIDFCO merger. A range of UK government ministries and agencies are involved in supporting the aid programme, including some less common development actors such as the UK Government Digital Service. They work together in support of a shared country development strategy that prioritises economic reform and support for the Jordan Compact through multilaterals. This helps to achieve a good level of complementarity across programmes.

In Turkey, the UK has a clear idea of the division of labour across the departments and aid programmes. The FRIT programme supports refugees and host communities, the Prosperity Fund promotes job creation and CSSF provides flexible resources to pilot initiatives on migration management and social cohesion which, if successful, can be scaled up by larger programmes such as FRIT.

The UK has invested in a joined-up approach to the North Africa region through the North Africa Joint Unit. This has increased the sharing of evidence among UK actors in the region and in London. We found that the appointment of a regional private sector advisor, based in Rabat, had improved coordination across UK agencies. The Egypt team benefited from this regional approach, being the only country in our sample to draw on London-based FCDO research results.

In Tunisia, we found coherence across UK agencies to be somewhat weaker. Similarly, in Lebanon, we noted a greater separation of identities, systems and knowledge between DFID and FCO, rather than a single UK government identity.

FCDO told us that the cross-government MENA strategy 2021-2030, expected to be completed in mid-2021, would provide a framework for greater coherence across country teams. It will assist with prioritisation in the context of the 2021 Integrated Review, focusing on shared security, mutual prosperity and enduring resilience, with a particular emphasis on economic growth and job creation. We were not given the opportunity to review drafts and cannot therefore say whether this will provide greater coherence.

Programmes are not always well integrated and multidisciplinary approaches are lacking.

Although we found the cross government approach to be coherent on the whole, we did find weaker operational coherence and coordination between advisors specialising in conflict and economics. We saw examples in both Jordan and Lebanon of a lack of coordination between CSSF conflict-related programming and the DFID/FCDO economic portfolio. FCDO officials told us that this tendency to ‘silo’ specialisms was common across the board, and that practical coordination often relied on individual personalities rather than being structurally incentivised in the organisation. In Jordan, while the four programmes in the economic portfolio were linked by common objectives, they did not join up with the CSSF MSSRP programme. Given that all the programmes contain employment-related objectives, this was a missed opportunity for synergy and shared learning.

As a cross-government fund blending official development assistance (ODA) and non-ODA resources, CSSF is intended to promote joint working across government. In practice, we found that this objective was not being met: The 2015-16 CSSF annual review in Tunisia, for example, found that sub-projects were not well coordinated. Despite efforts since then to consolidate the portfolio, it continues to encompass many small initiatives without a clear overall narrative. Officials told us that, while there are no barriers to communicating and coordinating across the different parts of FCDO and related funds, there are also no real enablers or incentives to do so.

Institutional knowledge of the portfolio was thin in places

In some of the programmes we reviewed, all active within the last five years, we found limited institutional memory of the interventions, their impact, the stakeholders involved and the results achieved. Often this was a result of staff turnover and inadequate handover, but also of inadequate programme documentation. This was notably the case in Lebanon, in Yemen and in relation to the regional APF. In Lebanon, UK officials were unaware of a youth employment component previously funded by MSP and implemented by UNDP LHSP. During the research phase, the UK government did not provide ICAI with any documents related to the UKLTH, despite multiple requests. Some programme documentation was subsequently provided to ICAI relating to the 2016-2017 financial year, but not the 2017-2018 financial year. The team also provided one business case document for a small research component of the UKLTH funded by CSSF. In relation to the APF, UK officials were less aware of the programme’s history than their national counterparts, and in Yemen’s Social Fund for Development, officials lacked detailed knowledge of the programme’s component parts and were unaware of its active youth employment components. We were also told across several programmes that, with the turnover of FCDO advisory personnel, new staff tended to steer projects towards their own technical focus and institutional memory was lost.

In one country, FCDO officials told us that they lacked technical expertise on their areas of programming because there were no former DFID staff in the team. They therefore relied heavily on partners not only to implement their programmes, but also to design them. For example, FCDO had asked the World Bank to prepare the UK’s own programme documentation for a trust fund contribution, suggesting a lack of adequate oversight.

The use of different information management systems for DFID- and FCO-funded work created variations in how well programme information was maintained, with DFID performing considerably better on knowledge management. The non-DFID programmes, including CSSF, have insufficient documentary requirements, making it difficult to reconstruct their purpose and achievements. The UKLTH project was designed in 2014 and apparently received around £3.2 million in UK funding in 2016. The programme ended in 2018. We were not able to verify the UK funding level or source or ascertain the programme’s results because the programme documentation was not properly archived and the department could not therefore provide relevant documentation during our fieldwork.

The UK has not always been active in donor coordination, contributing to duplication and inefficiency

Across our 19 sampled programmes, 14 were co-funded with other donors, including eight with the European Union, six with the Netherlands and four with the World Bank. Coordination with other donors, however, was not strong. In Jordan, UK officials told us that coordination was the UK’s main example of how it added value to the development process, but the UK was not present in the country’s government-donor platforms where youth employment issues were discussed. The UK jointly chaired the Jordan Task Force, which aimed to fill gaps on coordination, but other donors told us this had not been effective either in ensuring all partners were consulted or in replacing the existing donor coordination platforms.

In Tunisia, there is a crowded donor landscape with limited cross-sectoral coordination. The UK does not participate in existing donor groups on employability, macroeconomics or gender. We were informed that, after the UK’s exit from the EU, it had withdrawn from EU-led coordination mechanisms in Turkey.

The UK is an effective broker of donor coordination when it invests the time and energy required. We found one strong example in the Occupied Palestinian Territories, where the project evaluation noted the UK’s strong role in coordinating donor efforts to promote economic reforms.

Poor donor coordination comes with costs. We were informed that there is a degree of competition among donors in the employment field in Jordan, Tunisia and Lebanon, resulting in duplicative programmes, particularly in skills development and in support for entrepreneurs. This enables young people to move between donor programmes as a livelihood strategy. CSOs told us that certain CSOs and regions are over-served and others ignored because of poor coordination.

The UK lacks a strong approach to policy dialogue with national governments

We found limited evidence of clear UK objectives or approaches to policy dialogue and influence in the five countries we visited. In Jordan, where much of the programming is funded through the World Bank, government counterparts told us that their relationship was with the Bank and that they had little interaction with the UK. World Bank staff told us that they had hoped the UK would play a more active role in policy dialogue, given its involvement in individual programmes and in the Development Policy Loan guarantee. Similarly, in Tunisia, there was limited engagement with either government or civil society. While FCDO officials reported that they had successfully influenced government education policy, this was not apparent either to government or to other stakeholders.

In Lebanon, where policy dialogue with central government is limited by practicalities, the UK has adapted to working with local government and other partners. LEEP had aimed to work closely with the Lebanese government to provide financial incentives for SMEs to create jobs for Lebanese workers and temporary employment for Syrian refugees. However, FCDO and the Lebanese Ministry of Foreign Affairs could not agree on when refugees can return to Syria as the UK still considers Syria unsafe for returning refugees. These negotiations took some time and caused the start of the programme to be delayed. In Egypt, in a politically sensitive context, the UK made good use of the World Bank as an intermediary with government.

Delivering through multilateral partners, especially the World Bank, is an appropriate strategy in a technically complex area

Of the 19 programmes we reviewed, 13 were either fully (ten) or partially (three) delivered by a multilateral partner. The World Bank is the UK’s most frequent choice in our sample, reflecting the overall portfolio, followed by the EU and the UN, with one North African programme implemented by the African Development Bank (AfDB).

The World Bank is a recognised leader on youth employment, both in MENA and globally. The current replenishment of the World Bank’s International Development Association concessional resources for poor countries (IDA19) includes ‘Jobs and Economic Transformation’ as a special theme and the Bank has well-established expertise on job creation and economic growth. We found strong technical, analytical and diagnostic work across the World Bank teams on youth employment in all our country visits.

In our sample, UK-funded programmes delivered by the World Bank ranged from large-scale support for the Bank’s ‘development policy lending’, in other words, financial support linked to an agreed programme of reforms backed by direct UK finance or via UK guarantees to underwrite lending in Jordan and Egypt, to much smaller contributions to trust funds in Tunisia, Jordan and other countries.

The trust fund contributions, though small, can have a significant impact by influencing much larger World Bank lending programmes. We saw them used in this way in Jordan, Egypt, Lebanon and Tunisia, and in Tunisia the UK also contributed to an AfDB trust fund. These contributions are highly valued, by both the multilateral partners and the national governments. They have helped to finance analytical work and technical assistance which has been instrumental in informing national reforms. Trust funds also offer a flexible instrument for urgent needs. For example, the JIERAP mechanism in Jordan was significantly and rapidly scaled up by £25 million in response to COVID-19 to finance welfare payments for vulnerable households affected by the pandemic.