UK aid’s contribution to tackling tax avoidance and evasion

ICAI Score

In recent years, the G20 and the OECD have led a series of reforms on international tax, designed to help in the fight against international tax avoidance and evasion. DFID set out to influence these reforms so that developing countries could benefit from them. It also provided capacity building to help with implementing new tax standards.

DFID has helped developing countries to participate in various international tax processes; however, their ability to influence the content of the new standards was limited, and the international tax reform agenda failed to address a number of important issues for DFID’s partner countries.

DFID’s capacity building programmes on international tax have achieved some early results. Despite some initial problems, its partnership with HMRC is potentially a good model for collaborating on capacity building. However, various stakeholders expressed doubts that technical assistance on highly specialised international tax issues would have much impact, given the more basic problems with national tax systems. There are also concerns that the benefits to DFID’s partner countries of implementing the new standards may have been oversold.

We found that DFID does not have a clear approach to promoting ‘policy coherence for development’ in the tax area. It has not assessed areas of potential tension between UK tax policies and the needs of developing countries, nor made explicit decisions as to which issues to raise in cross-government dialogue.

We have given DFID’s work on international tax an amber-red score for relevance, because it is not well grounded in the needs and priorities of DFID’s partner countries. We awarded a green-amber score for effectiveness, in recognition of good cross-government collaboration and some early results on capacity building. An amber-red score for learning reflects that DFID has not made sufficient use of research or learning from its in-country tax programmes to inform its approach. Overall, this presents an amber-red score.

Nonetheless, we recognise that influencing international systems on matters such as tax is an important new frontier for the UK aid programme. We set out some recommendations to support future DFID and UK government efforts in this area.

Executive Summary

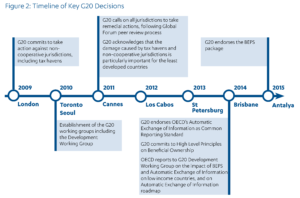

International tax evasion and avoidance is a global challenge, presenting significant costs for both developing and wealthy countries. In recent years, the G20 group of countries and the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) – with the support of the UK government – have led a series of reforms to the international tax system to tackle the problem.

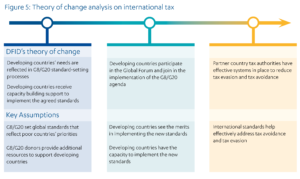

Working under the leadership of the Treasury, DFID sought to influence these international tax processes so that they could benefit developing countries, enabling them to mobilise more tax revenues for national development. While DFID did not set explicit objectives for its engagement with these processes, we identified two main objectives from its internal documents and our interviews with the tax team, against which to measure its performance:

i. To ensure that the needs of developing countries were considered in the G20 standard-setting processes.

ii. To ensure that developing countries received sufficient capacity building support to implement the agreed standards.

Box 1: The G20-led international tax reform agenda

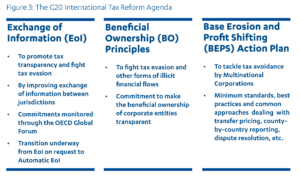

The G20 and the OECD have been promoting new international tax standards in three main areas:

1. Exchange of information on individual taxpayers between tax jurisdictions.

2. Disclosure of beneficial ownership (ie individuals who benefit from shell companies and trusts) to reduce secrecy in financial transactions and fight money laundering and tax evasion.

3. Measures on base erosion and profit shifting designed to limit the ability of multinational conglomerates to structure their affairs so as to avoid tax.

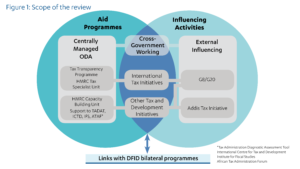

In this review, we assess DFID’s influencing work and capacity building on international tax, along with a number of other centrally managed programmes in the broader area of tax and development. DFID’s support for the G20-led tax processes has involved engagement by advisors in its central tax team and two main programmes: the Tax Transparency Programme (£7 million, 2014-17) and the HMRC Tax Expert Unit (£1.8 million, 2015-18). Its broader tax and development work includes support for the HMRC Capacity Building Unit (£22.9 million, 2014-24), which provides HMRC experts to support DFID bilateral tax programmes. These are included in the review to enable us to explore cross-government collaboration on capacity building.

This is a relatively small area of expenditure for DFID, with total commitments of £38.9 million over fourteen years, from 2010 to 2024. By comparison, DFID spent £32.6 million on in-country tax programmes in 2015 alone. However, international tax is one of the priority areas identified in the UK Aid Strategy for working ‘beyond aid’, by promoting changes to international systems that create more opportunities for developing countries1 . This is an important new frontier for the aid programme. It also offers a timely opportunity to assess how well DFID works with other government departments.

We have designated this a learning review because it examines a relatively new area of activity for DFID, where learning on how to achieve results is at an early stage.

DFID had only limited success in making international tax processes more inclusive

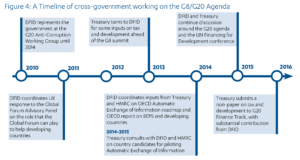

DFID used a number of channels to pursue its influencing goals on international tax. These include working closely with the Treasury to feed into G8/G72 and G20 processes, and representing the UK government in the G20 Development and Anti-Corruption Working Groups. Feedback from other participants indicates that DFID played a prominent and constructive role in these processes, building its profile as a leading donor on tax.

DFID’s efforts to make the international standard-setting processes more inclusive of developing countries were, nonetheless, only partially successful. DFID supported the participation of developing countries in various G20 and OECD processes, including the OECD Tax and Development Task Force and the Global Forum on Transparency and Exchange of Information. However, key stakeholders from both OECD and developing countries agree that developing countries gained little practical influence over the new standards. Consultations with developing countries occurred late in the process, when the priorities had already been agreed.

We were only able to find evidence of two measures introduced in response to developing country concerns.3 According to our survey and interviews, a number of issues of interest to DFID’s partner countries remain excluded.4

DFID leads the campaign for more donor support for capacity building although this is yet to produce significant results

One of DFID’s influencing objectives for the 2013 G8 summit at Lough Erne was to secure more donor funding for capacity building on international tax. Our review of the correspondence leading up to the summit showed that DFID secured references to capacity building in the G8 communiqué, but no commitment to increasing donor support. DFID itself remains the largest donor in the international tax arena.

DFID also supported the launch of the Addis Tax Initiative at the UN Financing for Development Conference in July 2015. This included a commitment by donor signatories to ‘collectively’ double their assistance (a formulation that provides flexibility to the responsibilities of individual donors). It is too early to say whether this commitment will be met. With DFID’s encouragement, the OECD body responsible for aid statistics is just beginning to monitor donor expenditure on tax.

The Addis Tax Initiative was developed by DFID and other donor countries with only limited consultation with developing countries and no explicit assessment of their needs. As a result, DFID and its donor partners had to lobby their partner countries at the Addis conference to sign up to the initiative. So far, only nine DFID priority countries have done so.5

DFID has provided some effective capacity building support, but it remains unclear whether partner countries will be able to implement the new standards

DFID supports implementation of the new tax standards through a number of centrally-managed programmes. These are beginning to deliver some early results. Various participating countries have adopted new regulations, signed international or bilateral agreements, developed action plans or established new specialist units within their tax administrations. Two of DFID’s partner countries, Kenya and Zambia, have successfully resolved some individual transfer pricing cases, albeit with the direct support of international experts.

However, some of the stakeholders we interviewed in our case study countries, including DFID advisors, expressed doubts that technical assistance on highly specialised international tax issues would have much impact, given more basic capacity constraints in national tax systems. There are also concerns that the DFID-supported OECD has taken an overly technical approach to capacity building, which fails to take sufficient account of the state of national tax systems.

DFID’s capacity building support on international tax was designed to be demand-led. Yet according to DFID’s own programme documents, demand from partner countries has been mixed. DFID and the OECD have responded by raising awareness of these issues in order to persuade African leaders of the benefits of implementing the new tax standards.

Despite these efforts, a number of stakeholders expressed their concern to us that these benefits may have been oversold. It is unclear whether measures such as exchange of information will prove effective, given more basic problems such as corruption in national tax administrations and the lack of effective sanctions and asset recovery mechanisms. Many developing countries grant overgenerous tax incentives to multinational corporations in order to attract investors. If multinational corporations have little tax liability in the first place, it is unlikely that measures to prevent profit shifting will generate significant additional revenue.

As a result, we are concerned that DFID’s influencing approach and its capacity building support on international tax have not been based on clear analyses of developing country needs, or on how international tax initiatives should be sequenced with broader reforms to domestic tax systems.

DFID has worked well with other UK government departments on influencing and has developed a promising model for collaboration on capacity building

DFID worked well with Treasury and HMRC to shape UK positions to take into G7/G8 and G20 processes. We saw evidence of DFID’s technical inputs being utilised by other departments, and that strong cross-government collaboration had contributed to effective UK advocacy.

In response to encouragement from the International Development Committee (IDC),6 DFID provided funding to HMRC to establish a Capacity Building Unit on tax. This is now funded from HMRC’s own aid budget, with estimated funding of £22.9 million over ten years. Through this unit, experts from HMRC are deployed to support DFID bilateral tax programmes for both short and long terms. While at an early stage, our case studies suggest that this is a promising model of collaboration. It enables DFID programmes to call on specialist expertise from HMRC, while ensuring that HMRC’s technical assistance is anchored in a broader strategy aligned to each country’s needs and priorities.

Beyond the Capacity Building Unit, we found that other departments do not look to DFID centrally for advice on how to provide effective capacity building. Nor is there much evidence of DFID trying to cultivate this role. DFID has now recognised that it needs to make a more active contribution on this issue.

There are value for money concerns with aspects of DFID’s capacity building support

In its international tax work, DFID has made efficient use of small investments of financial and human resources. It has combined its spending and influencing activities well, worked productively with other departments and used aid resources strategically to build up the capacity of its implementing partners.

However HMRC’s early use of funds was not good value for money. In the first year of the Capacity Building Unit, £1.17 million was spent on training HMRC tax experts for domestic roles in order to release existing staff for deployment abroad.7 HMRC has never achieved more than half of its planned deployment. This highlights a key value for money risk as departments take on new aid delivery roles. It will take time for them to establish the systems, capacity and programmes needed to spend aid effectively in new country contexts.

There are also value for money concerns about short-term technical assistance. In our survey and country case studies, national tax authority officials expressed doubts that short-term, one-off missions added much value. Some DFID in-country tax advisors also expressed views that revenue authorities in many developing countries lack the capacity to absorb highly specialised, short-term inputs. Given the commitment in the Aid Strategy to making more use of the technical skills available across the UK government for aid delivery, this is an important finding. While counterparts appreciate the opportunity to interact with their UK peers, there is still much to be learnt about how to use peer-to-peer assistance to best effect.

DFID does not have a clear approach to promoting policy coherence for development in tax

Under the Busan Partnership for Effective Development Cooperation,8 the UK is committed to pursuing ‘policy coherence for development’ – that is, promoting greater coherence across its public policies so as to increase opportunities for developing countries. Both the IDC9 and the OECD10 have encouraged DFID to do more in this area.

Our evidence suggests that DFID has not actively pursued policy coherence for development in the tax arena. A number of policy positions taken by the UK government, including a strong commitment to tax transparency, have been helpful to developing countries. However, the literature suggests that there are potential areas of tension between UK policies and developing country interests, including those concerning international tax competition and bilateral tax treaties. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the OECD have both advocated that developed countries undertake ‘spillover analysis’, to assess the indirect impacts of their tax policies on developing countries. The UK government has declined to do so, following the Treasury’s assessment that it would be impractical and time-consuming.

We take no view on the merits of UK policy position on ‘spillover analysis’ nor on tax more generally. We also recognise that, once a UK policy decision is made, it is binding on DFID. However, given that tax is highlighted in the Aid Strategy as a ‘beyond aid’ priority area, we would have expected to see evidence of DFID taking active steps to understand the impact of UK tax policies on developing countries and making informed judgments about raising areas of tension in cross-government dialogue. We found no evidence that this had been done.

DFID has made some useful investments in research, but has not drawn on evidence and learning effectively in its international tax work

There is a lack of solid evidence on how international tax issues affect developing countries, which hampers policy making. DFID has supported a research centre on tax and development at the University of Sussex by contributing £3.5 million (2010-16). Its research is well regarded; however in the absence of robust primary data from developing countries, its work on international tax remains largely theoretical.

We found little evidence of DFID’s tax team drawing on available research while setting its own priorities, in its dialogue across the UK government, or with external partners. Nor is there much evidence of DFID using the knowledge available within its country offices to inform its international influencing activities or central programmes on tax.

We also found that DFID did not establish explicit objectives for its influencing work on international tax, or any method of assessing its impact. In the absence of robust monitoring arrangements, we observed a tendency in some documents to overstate the results of its influencing efforts. If DFID hopes to achieve real impact though its ‘beyond aid’ engagements, it needs to adopt a more strategic approach to achieving and measuring results.

Conclusions and recommendations

DFID positioned itself well to take advantage of the opportunity presented by the G20 tax reform agenda to help developing countries benefit from the new international tax standards. It has made efficient use of limited advisory resources and combined influencing activities and aid programmes in complementary ways. It has demonstrated good cross-government collaboration and has achieved some positive early results with its capacity building, although there is reason to question the value for money of some of HMRC’s early work and of its one-off, short-term technical assistance. In light of these successes, we have given DFID a green-amber score for effectiveness.

However DFID’s influencing approach was not based on sufficient consultation with, or analysis of the needs of, its partner countries. While DFID supported developing country participation in certain international tax processes, their influence over the content of the new standards proved to be limited. DFID has also not pursued an active approach to promoting policy coherence on tax and development across the UK government. In light of these shortcomings, we have given DFID an amber-red score for relevance.

Finally, DFID has made some worthwhile investments in research in an attempt to address evidence gaps. Despite this, we found relatively little indication that DFID had used research or experience from its country programmes to support its influencing activities or to push the boundaries of policy dialogue on international tax. A lack of clear objectives, explicit strategy and monitoring arrangements for its influencing has also limited DFID’s ability to learn lessons and has led to over-optimistic assessments of its results. We have therefore given DFID an amber-red score for learning.

In light of the two amber-red scores for relevance and learning, and the green-amber score for effectiveness, we have given DFID an overall score of amber-red for its international tax work.

We have made a number of recommendations to improve future efforts in this area.

Recommendation 1: Learning on international tax issues

DFID should make better use of its in-country work on tax and anti-corruption to inform its influencing efforts and prioritise its programming on international tax.

Recommendation 2: Cross-government working

DFID should be more proactive in ensuring that other departments engaging in capacity building on tax and more generally, are able to draw on its experience of effective capacity building approaches and its knowledge of country contexts. This will require closer collaboration between departments, both at headquarters and in country.

Recommendation 3: A strategic approach to influencing

DFID should adopt a more systematic approach to influencing and cross-government working on international tax, with a stronger strategy and explicit objectives that are adequately resourced and properly monitored.

Recommendation 4: Policy coherence for development

DFID should take a more active approach to promoting policy coherence for development on international tax, for example by assessing the impact of UK tax policies and practices on developing countries and deciding whether to raise any points of tension in cross-government dialogue.

We have also proposed a number of ‘learning frontiers’ relevant to ‘beyond aid’ engagements by DFID and other government departments. These include capitalising on DFID’s expertise more generally and introducing a more active approach to policy coherence for development.

Introduction

Purpose of the review

In an increasingly globalised world, many wealthy individuals and multinational corporations have developed sophisticated cross-border strategies to avoid paying tax, using loopholes in the global financial system. The resulting loss of revenues affects both wealthy and poor countries. Tax havens and non-cooperative jurisdictions enable wealthy individuals to hide their wealth, evade tax and

launder money from illicit activities. There is heightened public interest in these issues following the recent leak of documents from the Panamanian law firm, Mossack Fonseca & Co. (see Box 2).

In its Aid Strategy, the UK government has committed itself to going ‘beyond aid’ in its pursuit of global poverty reduction11 – that is, not just funding development programmes, but also working to change UK and global policies and systems to create more opportunities for developing countries. One of its priority areas for working beyond aid is tax. In recent years, DFID has worked through the G20 group of countries and the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD)12 to help developing countries implement new international standards designed to combat tax avoidance and evasion.

Box 2: The Panama Papers and the challenge of tax havens

In 2015-16, 11.5 million documents were leaked from a Panamanian law firm, Mossack Fonseca & Co. – one of the largest offshore law firms in the world. The papers shed light on a range of practices to disguise or hide wealth from national tax authorities.

The Panama Papers have revealed a strong connection with the UK, as around half of the legal entities mentioned are registered in offshore financial centres in UK Overseas Territories and Crown Dependencies. These centres offer low or zero rates of corporation tax and, traditionally, a commitment to secrecy. The Crown Dependencies and Overseas Territories have signed up to international standards on exchange of information, including automatic exchange. They have so far resisted calls to create a public register of beneficial ownership for UK-registered firms.

In this review, we explore DFID’s contribution to the G20-led tax reform agenda, which began in 2009 and is still underway. With support from the OECD, the G20 has developed a number of global standards and processes to promote greater transparency and tackle abusive forms of tax avoidance.

These include:

• Exchange of information on taxpayers between national authorities (including automatic exchange of information).

• Disclosure of who ultimately benefits from companies, trusts and other legal entities.

• Measures to limit the ability of multinational companies to avoid taxes through the way they manage their trade and investment flows.

These initiatives are described in more detail in the background section. A glossary of technical terms is provided in Annex 2.

This review explores how well DFID has used its influence across the UK government and with international partners to help developing countries benefit from these standards. This is the first external review of DFID’s engagement with the G20. It is also the first ICAI review of DFID’s approach to ‘policy coherence for development’ – that is, its efforts to identify and address potential conflicts between the UK’s international development objectives and other UK policy agendas.13

This review also assesses how DFID has used its aid programmes to promote the participation of developing countries in international tax standards, and to support other tax and development initiatives. Through a number of centrally managed programmes, DFID provides funding to HM Revenue and Customs (HMRC), the OECD and other partners for capacity building support.

The collaboration with HMRC and Treasury aligns with a UK government commitment under the Aid Strategy14 to make better use of the complementary skills available across government in the delivery of UK aid.15

We have chosen to undertake a learning review because working beyond aid on international rules and standards is a relatively new activity for DFID. Particular emphasis is given to the way DFID has generated and applied evidence and learning to support its approach. As well as reviewing DFID’s performance to date, we draw attention to areas where DFID and other government departments could focus their learning in the future. We call these ‘learning frontiers’.

Box 3: What is an ICAI learning review?

ICAI learning reviews examine new or recent challenges for the UK aid programme. The focus is on knowledge generation and the translation of learning into credible programming. Learning reviews do not attempt to assess impact. They offer a critical assessment of progress to date and whether programmes have the potential to produce transformative results. Our learning reviews recognise that the generation and use of evidence are central to delivering development impact. Other types of ICAI reviews include performance reviews, which probe the efficiency and effectiveness of UK aid delivery, and impact reviews, which explore the results of UK aid.

Scope of the review

The review covers three main areas of the DFID Financial Accountability and Anti-Corruption Team’s work on international tax.

• First, we examine DFID’s efforts to influence and support the international tax reform agenda.

• Second, we review other elements of DFID’s ‘tax and development’ agenda, including its contribution to the HMRC Capacity Building Unit (£22.9 million, 2014-24)16 and the Addis Tax Initiative (see Box 8).

• Third, we explore the link between these centrally managed initiatives and DFID’s country-level programming on tax, looking at whether they are coordinated, reinforce each other and enhance learning. (We have not reviewed DFID’s country-level tax programmes directly).

The total financial commitment to the initiatives covered by this review is £38.9 million over a fourteen year period (2010-24).17 This is a small investment by DFID’s standards, compared to the £32.6 million it spent on in-country tax programmes in 2015.

Box 4: Programmes covered by this review

There are two centrally managed programmes that support international tax initiatives:

• Tax Transparency Programme (£7 million, 2014-17): This funds the OECD’s Tax and Development Programme, the Global Forum on Transparency and Exchange of Information for Tax Purposes (Global Forum) and the World Bank to provide a range of support for developing countries on international tax. It also facilitates the deployment of experienced tax audit experts as part of the Tax Inspectors Without Borders project. In 2015, the programme was extended by an additional £0.5 million to cover Base Erosion and Profit Shifting (BEPS) and the Global Forum’s Africa Initiative, which encourages African countries to commit to exchange of information.

• HMRC Tax Expert Unit (£1.8 million, 2015-18):18 This programme funds the HMRC to provide targeted capacity building support to developing countries on transfer pricing and exchange of information.

Other programmes that promote the broader tax and development agenda are:

• HMRC Capacity Building Unit (estimated £22.9 million, 2014-24): The HMRC Capacity Building Unit delivers short- and long-term technical assistance to tax authorities in DFID priority countries to help them develop and implement equitable and effective tax systems.

• Tax Administration Diagnostic Assessment Tool (TADAT) (£2 million, 2014-17): DFID is helping the International Monetary Fund (IMF) develop a tool for assessing the performance of tax administrations in developing countries against a standard set of indicators. The tool was launched in November 2015.

• International Centre for Tax and Development (ICTD) (£3.5 million, 2010-16): The ICTD is a five-year research programme to develop evidence on how to promote tax reform in developing countries. It includes some elements on international tax.

• Enhancing Tax Policy-Making (£1 million, 2015-17): This programme funds the Institute for Fiscal Studies (IFS) to provide capacity building and conduct independent analysis and modelling of the impacts of tax policy in developing countries.

• African Tax Administration Forum (ATAF) (£0.7 million, 2010-14): DFID supported the establishment and operation of this forum, which provides a platform for cooperation and peerto- peer learning to improve the performance of tax administrations across Africa.

Table 1: Our Review Questions

| Review criteria and questions | Sub-questions |

|---|---|

| 1. Relevance: How relevant is DFID’s approach to addressing the global issues of cross-border tax avoidance and tax evasion? | • To what extent is DFID’s approach to addressing the global issues of cross-border tax avoidance and tax evasion well-articulated and aligned with DFID’s strategic objectives? • How relevant is DFID’s approach to addressing the global issues of cross-border tax avoidance and tax evasion in relation to the needs and challenges of developing countries? • To what extent is DFID’s level of support commensurate with DFID’s and/or government’s stated ambitions? |

| 2. Effectiveness: How effectively has DFID contributed to addressing the global issues of cross-border tax avoidance and tax evasion in a way that benefits developing countries? | • How effectively has DFID combined its financial and non-financial instruments to influence and follow up on international commitments on international tax for the benefits of developing countries? • How effectively has DFID promoted crossgovernment working and policy coherence for development on international tax? |

| 3. Use of evidence and learning: To what extent is DFID generating and applying evidence and learning to support its approach to addressing the global issues of cross-border tax avoidance and tax evasion? | • How effectively is DFID using learning within DFID and across government to determine the most strategic interventions? • How effectively is DFID using available evidence and addressing gaps in the evidence to support its approach to international tax? |

Methodology

The methodology for this review involved four main elements:

i. An assessment of DFID’s centrally managed programmes and non-spending activities in relation to international tax. This included assessing DFID’s engagement with international processes, its work with other UK government departments, and the effectiveness and value for money of DFID’s programmes and activities. Our evidence comes mainly from stakeholder interviews and documents from DFID and other UK government departments.

ii. Four country case studies (Ghana, Ethiopia, Tanzania and Pakistan),18 which examine DFID’s programmes and activities from the perspective of particular countries. The case studies were prepared by reviewing documents and conducting telephone interviews with stakeholders, including national tax authorities, but did not involve country visits.

iii. A survey of DFID lead advisors on tax in country offices. 18 responses were received, which was a satisfactory 62% response rate.

iv. An extensive literature review and two roundtables with UK-based non-governmental organisations (NGOs) and private-sector representatives, to explore (i) the scale and impact of tax evasion and avoidance in developing countries; (ii) the main achievements and limitations of the international response and the UK’s position on international tax; and (iii) progress by signatory countries (including the UK) on international commitments. We also produced an annotated bibliography of analysis by southern organisations, to help capture developing country perspectives.

One of the challenges for this review was that DFID does not have explicit objectives for all of its international tax work. We conducted our own analysis of DFID’s objectives from documents and interviews, and used these to measure effectiveness.

Box 5: Limitations of our methodology

• The review covered activities by other government departments, such as Treasury, that are not aid-financed. We had only limited access to their personnel and internal documents.

• In the absence of country visits, opportunities to obtain direct feedback from developing countries were limited. Telephone interviews were conducted with national officials and donor representatives in the four case-study countries. In some cases, tax revenue authorities assisted DFID tax advisors in completing the survey. We also sought out relevant literature by southern organisations and conducted telephone interviews with the African Tax Administration Forum.

• Some of the centrally managed programmes are still at an early stage, making it too early to review their effectiveness.

• Cross-government working and international influencing involve many actors, often making it difficult to attribute results to DFID or even to the UK.

Background

The G20 international tax reform agenda

The G20 is tackling tax evasion and avoidance by promoting transparency and cooperation

Since the 2008 global financial crisis, the G20 group of countries has emerged as the leading international forum on the global economy. In a series of declarations from 2009 onwards, the G20 has pledged to increase transparency and improve international cooperation in order to combat tax avoidance and evasion. Commitments were also made during the 2013 G8 summit in Lough Erne.

The G20 international tax agenda comprises three main initiatives: exchange of information, beneficial ownership, and base erosion and profit shifting (BEPS) (Figure 3). With the OECD Global Forum taking the lead, it has established standards for sharing information on tax payers between national tax authorities – initially on request and then from 2014 through an automated system. There is a peer review mechanism for monitoring countries’ compliance with these standards.

From 2013, the G8 countries agreed to begin sharing information on beneficial ownership – that is, on the individuals who ultimately stand to benefit from shell companies, trusts and other legal entities. This was part of a campaign against corruption and money laundering, as well as against global tax evasion. The G20 followed suit in 2014. This information will be shared between competent authorities under the new exchange of information standards.

The third initiative is a package of measures to fight international tax avoidance. Some multinational companies avoid tax by shifting profits between related legal entities in different jurisdictions – for example, through manipulating ‘transfer pricing’ of transactions between subsidiaries.19 The agreed mechanism for tackling this issue is the BEPS package of measures, endorsed by the G20 in Antalya in 2015. The package includes minimum standards, common approaches and best practices.

Developing countries have been invited into G20 international tax processes

The G20’s tax agenda was designed to address the needs and priorities of G20 countries. In an increasingly globalised world, these initiatives need to be global in reach to be fully effective. The G20 and its partner organisations have therefore encouraged developing countries to adopt the new international standards. In their communiqués, they have invited them to join the OECD’s Global Forum, and pledged capacity building support to help them implement the agreed standards.

Today 134 countries, including nine DFID priority countries, are members of the Global Forum.20 In early 2016, the OECD also invited developing countries to participate in its Committee on Fiscal Affairs, which oversees the BEPS initiative.

The UK position

The UK has played a leading role in the G20 tax agenda

Working closely with Germany, France and the US, the UK government has played a significant role in promoting tax transparency, particularly during the UK presidency of the G8 in 2013. The UK was the first country formally to commit to implementing country-by-country reporting. In 2015, it adopted legislation establishing a public register of beneficial ownership (excluding trusts), which goes beyond the agreed international standards. An Anti-Corruption Summit in London in May 2016 provided an opportunity for other countries to make commitments to publicising beneficial ownership.

Treasury is the lead department on the UK’s international tax policy, with support from DFID and other departments. To support this work, DFID has scaled up its centrally managed programmes on tax and development, from less than £5 million in 2012 to just below £40 million today (see Box 4).

Findings: How well has DFID contributed to the development of international tax standards in a way that benefits developing countries?

Tax policy is one of a number of areas where DFID has undertaken to work ‘beyond aid’ to defeat poverty and promote global prosperity.21 DFID recognised that developing countries would need technical assistance from donors to implement the new international tax standards. It also saw an opportunity to influence the standards so as to enhance the benefits to developing countries. These objectives were later reflected in the UK Aid Strategy, in the form of commitments to tackling tax evasion and avoidance and allowing developing countries full access to automatic exchange of information.22

DFID did not set out explicit influencing objectives for its work on international tax. Through our interviews with DFID staff and our review of DFID documentation and correspondence in the lead-up to key events, we identified two underlying objectives:

i. To ensure that the needs of developing countries were considered in the standard-setting processes.

ii. To ensure that they received sufficient capacity building support to implement the agreed standards.

We assessed DFID’s progress against both objectives.

DFID used a range of influencing channels and aid investments to pursue its objectives

DFID used a number of channels to influence the international tax agenda. Its central team worked closely with the Treasury to feed into the 2013 G8 summit and the G20 Finance Track. It represented the UK in the G20 Development and Anti-Corruption Working Groups, taking part in the discussions and sharing briefings on UK positions (see Box 6). It also took advantage of the preparations leading up to the 2015 UN Financing for Development conference to promote the Addis Tax Initiative, alongside other donor countries and the host country, Ethiopia.

Box 6: DFID’s role in the G20 Anti-Corruption Working Group

The G20 Anti-Corruption Working Group leads the development of international standards on beneficial ownership. It coordinates G20 countries as they ‘lead by example’ in introducing new measures to fight corruption. There is limited scope for developing country participation.

DFID represented the UK government in the Working Group from 2010 until 2015, when it was replaced by the cross-government Anti-Corruption Unit. As the UK representative, DFID’s role was to coordinate inputs from UK government departments, rather than to promote its own development agenda. Informant interviews and documents indicate that the UK played an important role in the process, leading to the adoption of the High Level Principles on Beneficial Ownership in 2015.

Through these efforts, DFID has been highly visible in discussions on the G20 tax agenda. The donor representatives we interviewed were in agreement that DFID played a prominent role. They also gave positive feedback on DFID’s role as co-chair of the Domestic Resource Mobilisation pillar of the G20 Development Working Group. Some linked the quality of DFID’s technical inputs to the specialist knowledge of its tax advisors in London, others to its substantial portfolio of bilateral tax programmes.

Its efforts to make the G20 processes inclusive had only limited success

DFID set out to influence the international tax processes so that the needs of developing countries were considered in the new standards. According to one internal document, its aim was to make the new standards ‘truly inclusive’.

Working with the OECD and other donor countries, DFID supported the participation of developing countries in various G20 processes, initially in the OECD Tax and Development Task Force23 and the Global Forum, then later in various diagnostic exercises.24 When the G20 agreed to a more structured dialogue with developing countries on the BEPS package, DFID responded with additional funding to enable the OECD Tax and Development Programme to support their participation.

One of the barriers to inclusive dialogue on international tax is that few low income countries have the resources or expertise to participate substantively in what are often highly technical discussions. DFID’s investment in the African Tax Administration Forum has helped to overcome this barrier, even if that was not its initial purpose. Set up in 2009 as a platform for cooperation among African tax authorities, it has proved to be a useful structure for representing African interests in international processes.

With financial support from DFID and other donors, the Forum has co-hosted regional events on international tax with the OECD. Various African countries, including three of our case study countries, have used the Forum to represent them in international dialogue.

Despite these efforts, the key stakeholders we interviewed from both OECD and developing countries agree that developing countries gained little practical influence over the international tax standards. In 2014, the OECD’s Development Working Group acknowledged that a number of issues important to developing countries – such as wasteful tax incentives, the lack of comparable data on transfer pricing and tax avoidance through the indirect transfer of assets – had not been addressed in the BEPS package.25 Fourteen developing countries were subsequently invited to participate in the OECD’s Committee on Fiscal Affairs and a series of regional consultations were undertaken. However, this occurred late in the process, when the list of priority actions on BEPS had already been agreed. We were only able to find evidence of two measures introduced into the BEPS package as a direct response to developing country concerns.26

Similarly, the standards on automatic exchange of information were developed without consulting developing countries. Commentators have pointed out that they are both technically demanding and resource-intensive for developing countries to implement. The G20 Development Working Group recognises that implementing the automated system will be challenging for some tax administrations and may need to be a long-term objective.27

To help developing countries adopt the new standards, the Global Forum has recommended piloting automatic exchange of information in selected countries; DFID, with support from the Treasury and HMRC, is leading the pilot in Ghana. With funding from DFID and other donors, the OECD is also working with other international organisations and regional tax bodies to develop guidance (‘toolkits’) on areas of interest to developing countries which were not included in the final package of BEPS measures.28

In all, DFID’s objective of influencing the G20 tax standards to reflect the needs of developing countries was not achieved. The BEPS measures do not address a number of issues of concern to developing countries, and the automatic exchange of information standards remain largely beyond the capacity of many tax authorities to implement.

DFID has not supported the wider international tax reform agenda

Despite recent efforts to broaden participation, the G20 and the OECD are not well positioned to represent the needs and priorities of developing countries. Most of the stakeholders we interviewed – including NGOs, regional organisations, multilateral agencies and developing country governments – were in agreement that the OECD and G20 countries still largely set the international tax reform agenda.

Many developing countries and development NGOs have therefore called for more fundamental reforms to the structure of the international tax system, to make it fairer for developing countries. They have also called for changes to the international architecture where these issues are debated, to make it more representative. DFID has not so far supported this wider reform agenda.

At the 2015 UN Financing for Development conference in Addis Ababa, the G77 (which represents 126 countries) called for the UN Tax Committee to be upgraded from its current status as a ‘group of experts’ to an intergovernmental body with balanced geographical representation. Their objective was to create a new, more legitimate counterpart to the OECD, as a forum for debating more fundamental tax reforms. The proposal was rejected by the UK and other OECD countries, who argued that it would be duplicative and ineffective.29

DFID informed us that it has chosen to work with the G20 and the OECD in order to make use of their technical capacity and the political momentum behind the existing international tax processes. While the UK is a long-standing member on the UN Tax Committee and fronts an HMRC representative at meetings, it does not believe that the committee would be an effective standard-setting forum. We accept that this is a reasonable assessment of the current situation, and that DFID is bound by UK government policy positions.

In all, attempts to make the G20 tax reform agenda truly inclusive have not been successful; a number of other donors we spoke to recognised the need for a more representative international tax architecture and several were providing funding to the UN Tax Committee to help it become a more effective body.

Box 7: International tax fairness

For many years, developing countries and NGOs have called for reforms to international tax rules to promote a fairer international tax system, which would allow developing countries a greater share of tax on the activities of multinational companies operating in their territories. The G20-led tax reform agenda does not question the balance of taxing rights between ‘source’ (the country in which multinationals operate) and ‘residence’ (the country where they are headquartered) under the current international tax arrangements, which the literature suggests favours developed countries.

DFID’s push for more capacity building support through the G8/G20 had limited success

One of DFID influencing objectives for the 2013 G8 summit was to secure more international funding for capacity building on tax. DFID achieved the inclusion of references to capacity building in the G8 communiqué, including support on international tax and a long-term commitment to sharing tax expertise, together with a paragraph on “tax and development”.30

Our review of internal correspondence between DFID and the Treasury in the lead up to the summit, reinforced by interviews with officials, confirms that DFID helped to achieved these outcomes, working through the UK Presidency.

However, the commitments were limited in their ambitions. In the communiqué, G8 countries agreed to continue, rather than increase, their capacity building support. This fell short of DFID’s objective. As a result, DFID remains today the largest donor for both the OECD Tax and Development Programme and the Global Forum technical assistance programme.31

DFID’s support to the Addis Tax Initiative shows a top-down approach to developing country participation

In the face of reluctance from some donors to make specific funding commitments on international tax, DFID switched its efforts to other channels. Working with like-minded donors, it supported the Addis Tax Initiative, which was launched at the UN Financing for Development Conference in July 2015, to encourage the mobilisation and effective use of domestic revenues for national development.32

DFID initiated early discussions on the Initiative in various forums, including the OECD Tax and Development Taskforce and the G20 Development Working Group. It succeeded in securing a reference to international tax, but its attempts to negotiate a commitment to doubling donor support for domestic resource mobilisation ended in compromise, with donor signatories committing to ‘collectively’ doubling their assistance, allowing greater flexibility on individual contributions.

Box 8: Addis Tax Initiative

The Addis Tax Initiative was launched at the UN Financing for Development Conference in July 2015 by a group of donor countries, including the UK, the US, Germany and the Netherlands, and partner countries. Since its launch, more than 30 countries, regional and international organisations, including at least 16 bilateral donors and seven least developed countries, have joined.33 Donor signatories agreed collectively to double their funding for capacity building on domestic resource mobilisation, to offer extra support on international tax issues, and to ensure policy coherence in the tax arena. It is too early to say whether the spending commitment will be met. In consultation with DFID, the OECD Development Assistance Committee, which oversees global aid statistics, approved a new ‘sector code’ on tax in March 2016, which will facilitate monitoring of the commitment.

While the Addis Tax Initiative is described as a partnership, the preparations leading to its launch were donor-led and top-down in nature, rather than consultative or based on an analysis of developing country needs. Progress in getting DFID partner countries to sign up to the Initiative has been slow. To date, only nine DFID priority countries have done so, even though our survey suggests that there is appetite from developing countries for more donor support for domestic resource mobilisation.

Findings: Has DFID helped developing countries implement international tax standards?

DFID’s capacity building support is helping partner countries adopt international tax standards and practices

DFID supports implementation of the international tax standards and practices through two centrally managed programmes: i) the HMRC Tax Expert Unit and ii) the Tax Transparency Programme, which are starting to deliver some early results.

The Tax Transparency Programme funds the OECD and the World Bank to support developing countries in adopting and implementing international tax standards and practices, both on transfer pricing and exchange of information. The OECD has also reviewed tax incentive regimes in selected countries.34 While the programme is still at an early stage, there have been a number of achievements up to mid-2016:

• 11 new countries have joined the Global Forum, which oversees the exchange of information standards.

• 14 countries have adopted national regulations on exchange of information and, in doing so, have passed Phase 1 of the Global Forum peer review process.35

• Uganda, Kenya, Jamaica and Senegal have joined the Convention on Mutual Administrative Assistance in Tax Matters, while other countries have signed bilateral exchange of information agreements.

• 14 countries have begun implementing action plans for legislative changes and administrative improvements for transfer pricing and related controls. Ethiopia adopted transfer pricing legislation in October 2015.

• Five countries (including one DFID priority country, Ghana) and one region (the Southern African Development Community) have received reviews of their tax incentives for investment by the OECD.

• In some cases, new specialist units have been established within national tax administrations.36

Box 9: Tax Inspectors Without Borders

Tax Inspectors Without Borders is a component of the DFID-funded Tax Transparency Programme. Run by the OECD Tax and Development Secretariat, it facilitates the deployment of experienced tax auditors on a demand-led basis to developing countries. Foreign experts work directly with local tax officials on particular tax-payer audits, helping to build audit capacity through a ‘learning by doing’ approach. Launched as a pilot in 2013, the initiative got off to a slow start because of the limited number of tax experts that were available and a lack of demand. Where experts were deployed (including two from the UK, to Rwanda and Lesotho), progress proved slow due to lack of preparedness, inadequate legislation and communication difficulties. Not all the partner country stakeholders we talked to were convinced by this peer-to-peer model, which depends heavily on the capacities of the individual experts. The OECD recently entered into partnership with the UN Development Programme to scale up the initiative, launching the expanded programme at Addis Ababa in 2015.

It remains unclear whether low-capacity countries will be able to implement the standards effectively

Despite these early results, some of the partner country stakeholders we interviewed expressed doubts that technical assistance in these highly specialised areas was likely to be effective in low-capacity environments. Aspects of the new standards are technically demanding and resource intensive to implement, and it is not yet clear whether DFID’s partner countries will be able to apply them effectively.

Among countries that have passed the necessary legislation on exchange of information, only a small number have begun requesting information from international partners. In Ghana, which has received capacity building support from the Global Forum since 2011, the tax revenue authority informed us that its staff remain unsure of when it is appropriate to make an information request. With automatic exchange, tax administrations in least developed countries may lack sufficient in-house capacity to make use of the high volumes of information that they would obtain.

Sustainability is also an issue. In the area of transfer pricing, nearly 200 individual cases were resolved in four countries (Kenya, Colombia, Vietnam and Zambia) in the first two years of the Tax Transparency Programme, leading to the recovery of approximately £85 million in revenue. The success of these cases shows the benefits of having the necessary legal framework in place. However, these cases were resolved with direct assistance from international tax experts. Even in countries that have received assistance for several years, there is little evidence that the tax authorities have the in-house capacity to carry out such audits without external support.

In our interviews, a small number of donor and developing country representatives criticised the OECD for having a narrow and overly technical approach to capacity building, without taking sufficient account of the underlying capacity constraints.

The new Tax Administration Diagnostic Assessment Tool may help with this sequencing challenge. Launched in late 2015, this tool offers a method of assessing the capacity of national tax administrations against a common set of indicators. DFID has contributed £2 million towards its development and for assessments in DFID partner countries. Such standardised diagnostic tools already exist in other areas of public financial management. They can help to build a common understanding among donors and partner countries on capacity building needs and priorities.

The benefits to developing countries of adopting international standards may have been oversold

The bulk of DFID’s capacity building support through the OECD has gone towards promoting the implementation of the international tax standards and principles in developing countries. This support was designed to be demand-led. The majority of tax authority stakeholders we interviewed from DFID’s partner countries confirmed that they need capacity building support to implement them.

Yet in practice, demand from DFID’s priority countries for OECD assistance has been mixed. According to programme documentation, DFID partner countries have taken up the offer of support on transfer pricing. However requests for assistance on exchange of information have instead come mainly from more advanced countries, such as Jamaica and Colombia, which are not priority countries for DFID.

In their monitoring reports, DFID and the OECD concluded that this reflected a lack of awareness of the benefits of the new standards in fighting tax avoidance and evasion on the part of developing countries. To address this, DFID provided the OECD with a further £0.5 million to launch the ‘Africa Initiative’, to promote the benefits of information exchange and build political support from African leaders for its implementation. A similar process of awareness-raising was also used for BEPS.37

Some awareness-raising among developing countries may have been justified in order to identify latent demand for the new standards. Yet a wide range of international and developing country stakeholders expressed concern to us that the benefits to developing countries of adopting international standards may have been oversold.

While hailed by G20 countries and the OECD as a major success, some UK-based NGOs and privatesector representatives expressed concerns to us that the BEPS measures will not have the expected results. These concerns are echoed in the literature. Many of the BEPS actions are non-binding. They focus only on tax avoidance, leaving most tax planning structures intact, and still permit aggressive tax competition to take place between jurisdictions.

Exchange of information between national authorities may not be enough to prevent wealthy individuals from developing countries using tax havens for tax avoidance and evasion. In our interviews with DFID officials and in internal documentation, DFID also recognised that in countries where the space to scrutinise public officials is small, making beneficiary ownership information public is important to support social accountability. Observers also point to the problem of corruption in national tax administrations and the lack of effective sanctions or asset recovery mechanisms as likely to undermine the value of the new international tax standards to developing countries.

Many developing countries also grant multinational corporations overgenerous tax incentives that are harmful to their economies. One report even goes so far as refer to tax incentives as “tax evasion with an official stamp”.38 If multinational corporations have little tax liability in the first place, then implementing the BEPS measures is unlikely to raise significant additional revenue.

Implementing new tax standards could draw resources away from more important priorities

While studies suggest that international tax avoidance and evasion have a substantial impact on developing countries, the revenue gains from addressing domestic tax issues are likely to be much higher. Our survey and our case studies confirm that many developing countries consider strengthening their domestic tax systems as a higher priority.

There is therefore a risk that implementing new tax standards could draw limited national capacity away from more important domestic tax priorities. Most of DFID’s spending on tax and development goes towards reforming national tax systems. However, DFID and its implementers appear to have given little consideration to the question of how to sequence the introduction of international tax standards with more basic reforms of national tax systems.

The G20 Development Working Group recognises that capacity building on international tax needs to be better coordinated, sequenced with more basic reforms, and better matched to the individual needs and conditions of countries, if it is to achieve sustainable results.39

Box 10: Tax and revenue loss in developing countries

Two important studies, by the IMF and the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD), confirm that developing countries face significant harm from international tax avoidance.40

The estimated revenue losses from tax avoidance by multinationals accounts for a higher share of GDP in developing countries than in OECD countries, owing to their greater reliance on corporation tax. UNCTAD estimates that multinational corporations shift over £300 billion away from developing countries each year. While the figures are controversial, the G20 itself has acknowledged that the damage caused by tax havens and non-cooperative jurisdictions is particularly important for least

developed countries.

Notwithstanding this evidence, the likely gains from domestic tax reforms are thought to be significantly higher. Our survey responses and our country case studies also indicate that many developing countries do not see the fight against international tax avoidance and evasion as a priority:

• In many countries, domestic tax avoidance and evasion accounts for much larger revenue losses. The policy focus is on widening the tax base and strengthening basic tax administrative capacity.

• In countries with growing foreign direct investment, such as Tanzania, Mozambique and Ethiopia, taxation of multinationals is likely to become more of a priority. The main policy concern here is around the use of incentives such as tax holidays and other concessions for investors. Competition for investment between developing countries can lead to a harmful ‘race to the bottom’. The extractive industries, such as mining, are particularly susceptible to this.

• In poorer countries, such as Somalia and the Democratic Republic of the Congo, customs abuse and smuggling are identified as much more significant, in terms of revenue losses, than tax avoidance by multinationals or tax evasion by wealthy individuals.

Findings: Has DFID promoted cross-government coordination on international tax?

DFID has worked well with the Treasury and HMRC to influence the G7/G8 and G20 agenda

DFID worked closely with Treasury (as lead department) and HMRC to shape UK positions ahead of the G8 summit in 2013 and around the G20 tax agenda. The Treasury drew on a range of DFID inputs, including a concept note on the G8 and developing countries, in its tax and development work. We saw evidence that strong cross-government working had contributed to effective UK advocacy at the G8 summit in 2013.

The relationship between the three departments is now well established, with a mixture of formal and informal interactions between the responsible teams.41 DFID is regularly consulted by Treasury on discussions in the G20 Finance Track. Recently, the two departments worked together on a UK proposal on tax and development, which helped to secure support of the principles of the Addis Tax Initiative in the G20 Finance Ministers’ communiqué.42

The HMRC Capacity Building Unit is potentially a good model for collaboration on technical assistance at the country level

The International Development Committee has highlighted DFID’s good work in the tax area and recommended that more should be done, including in partnership with HMRC.43 To that end, in 2014 DFID provided funding to enable HMRC to establish a Capacity Building Unit. HMRC now finances the Unit from its own aid budget, with estimated funding of £22.9 million over ten years to 2024. The Unit provides technical assistance on domestic tax. It complements a three-person HMRC Tax Expert Unit, which works on international tax issues.

Through the Capacity Building Unit, technical experts from HMRC are deployed to DFID priority countries in both short- and long-term advisory roles. These deployments are made in response to requests from DFID country offices, to complement DFID tax programmes. After a slow start, longterm advisors are now in place in Ghana, Tanzania and Ethiopia, where they are fully integrated into DFID bilateral programmes and able to call on additional specialised inputs from HMRC through short-term missions.44 Long-term advisors also support Pakistan (working from both London and Pakistan) and the African Tax Administration Forum. Other countries have received support solely through short-term missions.45

Our country case studies show that this form of collaboration has the potential to work well. Embedding HMRC advisors in DFID programmes ensures that HMRC’s technical expertise is used within a long-term capacity development strategy aligned to each partner country’s needs and priorities.

While it is too early to assess results, tax revenue authorities in Tanzania, Ghana, Ethiopia and Pakistan have expressed their appreciation for the opportunity to work with UK peers and have welcomed the combination of long- and short-term assistance.46 In Ethiopia, where HMRC has been engaged since 2006, support to the Revenue and Customs Authority has reportedly performed well.

However, there have also been challenges with this partnership. HMRC has sometimes had difficulty finding appropriately qualified staff to respond to partner country needs. Scoping and establishing relationships have taken longer than expected. Adapting to DFID’s decentralised structure has also been challenging for HMRC. When the Capacity Building Unit was launched, DFID bilateral tax programmes were at different stages of development and varied in their appetite for its support. These limits on both supply and demand have meant that progress has been slow. Our survey also indicated that both national tax authorities and DFID advisors in partner countries were less convinced that one-off short missions from HMRC experts add much value, in the absence of a wider engagement.

Centrally, DFID is beginning to provide more active support to other government departments on tax and development

During our interviews, other UK government departments indicated that they valued the knowledge on country context available in DFID country offices. Yet we found limited evidence that other departments looked to DFID centrally for its expertise on complex programming, governance and capacity building, or that DFID had attempted to cultivate this role.

In recent months, the DFID tax team has recognised the need to strengthen its support to other government departments and country offices. Under the Chinese G20 Presidency, development issues are being mainstreamed into the Finance Track, which means that the tax and development work is being led by the Treasury (DFID maintains the domestic resource mobilisation co-facilitator role in the Development Working Group). In response, the DFID tax team has stepped up its advisory role, making a significant contribution to the Treasury’s tax and development submission to the G20 in 2016.

With the HMRC Capacity Building Unit, DFID’s tax team initially focused on facilitating partnerships with DFID country programmes. Once these had been established, the expectation was that DFID’s central team would provide guidance on strategic issues, impact monitoring and pipeline management.47 DFID was slow to take up this role. In 2015, Treasury initiated a strategic framework for capacity building for the HMRC Capacity Building Unit, while HMRC decided to use its own monitoring and evaluation system.48 DFID has now recognised that it has an important contribution to make on those issues, and has stepped up the level of its support to Treasury and HMRC.

Findings: Has DFID promoted UK policy coherence on international tax?

DFID does not have a considered approach to policy coherence for development in tax

Alongside other donors, the UK has committed itself to pursuing ‘policy coherence for development’ by promoting greater coherence across its public policies, to increase the opportunities for developing countries49. In its 2015 Beyond Aid report,50 the International Development Committee recommended that DFID make policy coherence for development a higher priority.

The Addis Tax Initiative also contains a broad commitment on policy coherence, although this was the result of advocacy by other donors. It states: “All participants will ensure that relevant domestic tax policies reflect the joint objective of supporting improvements in domestic resource mobilisation in partner countries and applying principles of transparency, efficiency, effectiveness and fairness.”51

Box 11: What is policy coherence for development?

Policy coherence for development is a global commitment to promoting greater coherence of all public policies (not just development policies) to enable countries to make full use of development opportunities.54 Donor countries are encouraged to examine the interdependence between their development assistance and their international policy engagement (eg on trade, security and immigration), so that they do not act at cross purposes. The OECD defines policy coherence for development as:

“…an approach and a tool for integrating the economic, social, environmental and governance dimensions of sustainable development at all stages of domestic and international policy making. Its main objectives are to:

• Address the negative spillovers of domestic policies on long-term development prospects.

• Increase governments’ capacities to identify trade-offs and reconcile domestic policy objectives with internationally agreed objectives.

• Foster synergies across economic, social and environmental policy areas to support sustainable development.”

Based on our interviews with DFID and other government departments, consultation with civil society organisations and a review of internal documentation, we find that DFID has not actively pursued policy coherence for development in the international tax arena. DFID and Treasury officials make the argument that, in light of the UK’s strong commitment to tax transparency, UK domestic policy and the international development agenda are already aligned.

However, the literature suggests that there are areas of tension between UK policies and developing county interests in the broader tax arena, around issues such as international tax competition and bilateral tax treaties. In our review of internal documents and email correspondence, we found no evidence that DFID either raised or considered raising these issues in its discussions with other departments. As the UK government representative on the G20 Development Working Group, DFID rejected calls from the IMF and the OECD to assess the ‘spillover impacts’ of UK tax policies on developing countries , reflecting the Treasury’s view that this would be impractical and

time-consuming.

Box 12: The ‘spillover effects’ of UK tax policies

The IMF and OECD have advocated that developed countries undertake ‘spillover analysis’, to assess the indirect impacts of their tax policies on developing countries. The IMF argues that such spillovers cause substantial loss of revenue and welfare for developing countries and should be minimised.52

Bilateral tax treaties between developed and developing countries have come under particular scrutiny, given the inequality in bargaining power. The IMF has suggested that developing countries ‘would be well advised to sign treaties only with considerable caution.’ NGOs and developing country officials have criticised the UK’s wide and growing network of bilateral tax treaties with developing countries, claiming that they deprive them of vital revenue.53 Some civil society and tax authority stakeholders in our country case studies shared similar concerns.

We take no view on the merits of UK policy positions on ‘spillover analysis’ nor of international tax more generally, which are beyond our mandate. We also recognise that, once a UK policy decision is taken, it is binding on DFID. However, given that tax is highlighted in the Aid Strategy as a ‘beyond aid’ priority area, we would have expected to see evidence of DFID taking active steps to understand how UK tax policies impact on developing countries, and on this basis, making informed judgments about whether to discuss possible areas of tension in cross-government dialogue. In the absence of any evidence of a structured decision-making process of this sort, we conclude that DFID is not actively pursuing policy

coherence in the area of international tax.

This finding echoes the conclusions of the OECD’s 2014 peer review, which found that the UK government lacked “a comprehensive approach to ensuring its development efforts are not undermined by other government policies”.54 Some other donors have been bolder in adopting a more coherent approach to international tax.55

Findings: Has DFID generated and applied evidence and learning?

Both the international tax reform agenda and working cross-government to influence international standards are relatively new areas for DFID. We assess the extent to which it has drawn on evidence and learning to improve its work.

DFID has invested in research, but data gaps remain a significant obstacle to effective international tax policy-making

DFID recognised at an early stage that a lack of solid evidence on the significance of international tax issues for developing countries was an obstacle to effective policy-making. Poor quality data had contributed to a divergence of opinion on how to proceed.

In 2009, DFID commissioned the Oxford University Centre for Business Taxation to assess the quality of evidence on the scale and effects of tax avoidance and evasion in developing countries.56 Its report concluded that most existing estimates were not based on reliable methods and data.57 Our literature review indicates that little progress has been made on filling the data gaps since then.

DFID supported the launch of the International Centre for Tax and Development (ICTD) at the University of Sussex with a £3.5 million contribution (2010-16). Feedback from donor representatives and academics indicates that ICTD’s research is well regarded. Alongside other work, DFID had intended that ICTD would generate new evidence on international tax. However, the absence of reliable data from low- and middle-income countries has limited ICTD’s ability to generate new findings. Donor, academic and developing country representatives agree that limited progress can be made until more primary data is generated from developing countries. ICTD has begun addressing this gap by creating a new cross-country tax dataset and experimenting with collaboration between researchers and tax authorities.

DFID has not used research to push the boundaries of debate internationally or internally

An internal document from 2009 notes DFID’s intention to invest in research as a way of bringing stakeholders together around a common understanding of tax and development. While DFID has invested in some research and evidence collection, our review of internal documentation shows that it has relied mainly on diagnostic work produced by the OECD and other international organisations to inform its influencing approach. These diagnoses have focused primarily on the G20 tax reform agenda.

Within the growing body of international tax literature produced by international organisations, NGOs and academics, there is lively debate on the adequacy of the G20 tax initiatives and the potential for alternative models of international taxation.58 In our documentary analysis we found little evidence that DFID had actively engaged with these debates in setting its own priorities or in dialogue with other UK government departments or external partners.

DFID has not drawn sufficiently on its in-country knowledge to inform its approach to international tax

One of DFID’s areas of comparative advantage is its strong in-country network. Our survey revealed a good level of interaction between DFID country offices and national tax authorities. Yet we saw little evidence of DFID’s central team drawing on its country contacts and knowledge to inform the design and delivery of its international tax influencing activities and central programmes. Only three of the 18 country offices who responded to our survey had worked with the central policy teams on G20 issues. These were Kenya and Ghana – the two pilot countries under the Global Forum – and South Africa, a G20 country that already participates in the international tax standard-setting processes.

DFID’s Financial Accountability and Anti-Corruption Team argued that, at that stage, country offices had little knowledge of the G20 agenda and therefore could not have inputted into the UK position. However, we found no evidence of DFID drawing on knowledge from its bilateral programmes to assess whether the proposed G20 solutions would be relevant to its partner countries’ needs and priorities. This lack of consultation may have also contributed to DFID’s overestimating the demand for capacity building support from its priority countries.

Lack of monitoring of influencing work creates a risk of over-estimating achievements

DFID did not set itself an explicit set of influencing objectives for its international tax work. Nor did it establish any method of assessing its impact. In the absence of clear objectives or monitoring arrangements, we have observed in some DFID interviews and internal documents a tendency for DFID to be over-optimistic in the results it claims to have achieved through its efforts.59

Engaging with international standard-setting is an important part of the ‘beyond aid’ agenda. The formulation of objectives and the measurement of results need to be approached with the same level of rigour that DFID would apply to a more traditional aid programme. We note that since the start of our review, the DFID team has begun developing an evidence-based position paper and a theory of change on how they intend to use financial and non-financial instruments to meet UK government commitments on tax and development by 2020.

Findings: Has DFID’s approach to international tax been good value for money?

DFID has made good use of limited advisory resources and helped build the capacity of its international partners

In the international tax area, DFID has made efficient use of a small investment of resources (£38.9 million committed over fourteen years). With inputs from just three advisors, it was able to participate actively in a wide range of international forums and processes, albeit in pursuit of relatively narrow objectives.