UK aid’s international climate finance commitments

Glossary

| Key term | Definition |

|---|---|

| Actual spend | The amount of money spent on a programme. |

| Bilateral aid | Bilateral aid represents flows from official (government) sources directly to the recipient country. This includes programmes delivered in recipient countries through non-governmental organisations. |

| Climate adaptation | Climate adaptation refers to changes to processes, practices and structures in order to adjust to the current or expected effects of climate change. |

| Climate mitigation | Climate mitigation refers to action taken to limit climate change by reducing emissions of greenhouse gases or removing those gases from the atmosphere. |

| Concept note | The concept note sets out a proposal for an individual programme, explaining how it fits with the strategic objectives in a business plan, what the proposed intervention is and why it is recommended for ministerial approval (or approval by officials for lower-value proposals). |

| International climate finance | International climate finance refers to public, private and alternative sources of financing that seek to support developing countries in undertaking mitigation and adaptation actions that will address climate change. |

| Multilateral aid | A multilateral organisation is an international organisation whose membership is made up of member governments which collectively govern the organisation and are its primary source of funds. Multilateral aid is delivered though international institutions such as the various agencies in the United Nations and the World Bank. |

| Multi-bi | A donor can contract a multilateral agency to deliver a programme or project on its behalf in a recipient country: the funds are typically counted as bilateral flows, and often referred to as multi-bi. |

| Pipeline | A concept note for the programme has been approved but not a full business case. The budget will be provisionally agreed through the concept note and finally approved through the full business case. |

| Programmed spend | The amount of money budgeted and expected to be spent on a programme in the future. |

Executive Summary

Climate change is one of the biggest contemporary international development challenges. The UK is a signatory to the Paris Agreement, a legally binding international treaty of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) that aims to limit global warming and strengthen countries’ ability to deal with the adverse impacts of climate change. The UK government has long championed increased support for climate action in developing countries. In 2009, at the 15th Conference of the Parties (COP15) in Copenhagen, the UK and other developed countries jointly committed to mobilising $100 billion annually by 2020, from both public and private sources, for climate action in developing countries. In 2015, this goal was reaffirmed and extended to 2025 as part of the Paris Agreement. The UK has committed to provide at least £11.6 billion in international climate finance (ICF) between 2021-22 and 2025-26, ensuring a balance between adaptation and mitigation and including at least £3 billion on protecting and restoring nature, including £1.5 billion on forests.

This rapid review assesses progress against the UK’s ICF commitments to support developing countries to adapt to climate change and mitigate its impact. The review covers current ICF spending across the UK’s official development assistance (ODA) programme and its forward looking plans to meet its ICF spending commitments. It assesses the adequacy, predictability and transparency of the UK’s ICF spending in achieving its stated climate and nature goals and in enabling and influencing global climate action. As ICF comes from the ODA budget, an assessment of the UK’s ICF commitments needs to be placed in the context of cumulative reductions and increased pressure on the expected ODA budget.

Findings

Is the UK on track to meet its international climate finance commitments?

The UK government says that it remains committed to delivering on its £11.6 billion pledge over a five-year period to 2025-26. In the context of reduced aid resources and consequent backloading of aid spending, meeting this commitment has become contingent upon several methodological changes made in 2023 to the way the UK accounts for its ICF spend. These methodological changes, combined with efforts to ensure all ICF-eligible spend is included, are allowing more aid spending to be counted as ICF.

The main changes to the UK’s ICF accounting were:

- Multilateral development banks (MDBs): Accounting for the climate-relevant share of future UK core contributions to MDBs (as opposed to specific funding to MDBs). This provides an additional £746 million according to ICF data.

- Humanitarian funding: Applying a fixed proportion of 30% ICF to humanitarian programmes operating in the 10% of countries most vulnerable to the effects of climate change. This is expected to provide an additional £497 million of ICF between 2021-22 and 2025-26 according to government data, and reduces to some extent the trade-off between humanitarian and ICF spending.

- British International Investment (BII) contributions: Calculating the BII ICF contribution ratio based on actual BII investments, rather than assigning a fixed percentage as ICF as was done previously. The BII adjustments potentially amount to a total of £266 million over the ICF3 period, according to government data.

- ‘Scrubbing’ of existing programming: ‘Scrubbing’ of the existing ODA portfolio to identify additional ICF-eligible programmes, although the exact programmes and time period covered are not clear. Based on an internal document, the government has identified an additional £215 million of existing aid programme funding as ICF as a result.

The changes made to the methods used for calculating ICF were necessary to enable the UK to meet the £11.6 billion pledge but essentially just ‘moved the goalposts’ for measuring additional climate finance to developing countries. The changes reclassified existing ODA as ICF. Crucially, they did not entail allocating additional financing to developing countries.

Concerns have been raised by both parliamentarians and civil society about the implications for fulfilling the climate commitments for recipient countries, including whether these funds are likely to be allocated in countries that need them most. Some stakeholders have even wondered if the ‘scrubbed’ programmes actually tackled climate change-related challenges, demonstrating the challenge of identifying the climate relevance and impact of traditional programming, such as social protection and public works interventions. According to the government, the majority of programmes continue to be assessed on a case-by-case basis against internationally agreed guidelines from the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development.

There is insufficient transparency about the new methods and additional ICF identified, notably adjustments made to the ICF accounting by BII and the ‘scrubbed’ programmes, making it difficult for external stakeholders to understand and replicate the government’s calculations. It continues to remain unclear to ICAI, even after conducting this review, which programmes were ‘scrubbed’ and on what basis.

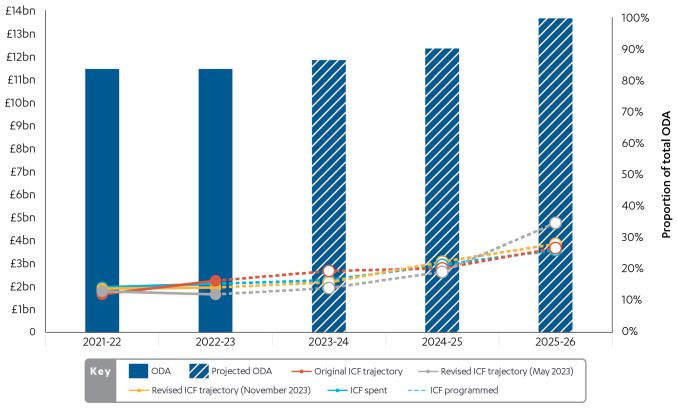

While there was always a projected increase in ICF commitments toward the end of the programming period, 55% of the committed spending is now planned for the two final years of the five-year period (as opposed to 53% in the original plans). Reaching the £11.6 billion target relies on the changes, as well as a mix of new and old (continued) programmes. The current plans are to spend between £3.4 billion and £3.8 billion of ICF in the final year (2025-26), which is after the next election and at least one spending review. In the context of successive budget reductions to ODA, serious concerns remain over whether the heavily backloaded spending plan can be delivered.

The ICF methodological changes have allowed more of the UK’s existing aid programmes to be counted as ICF, thus to some degree protecting aid budgets in areas such as humanitarian funding. Concerns were raised in the media in July 2023 about the impacts on the rest of the aid budget. However, contrary to the Guardian headline that 83% of the aid budget would have to be spent via ICF to meet the £11.6 billion target, it was in fact 35% in May 2023 and was further revised down to 28% as a result of the changes.

The sheer scale of the backloaded ICF target inevitably means that substantial trade-offs remain between ICF and non-ICF priorities, including humanitarian aid, so long as there continues to be an overall UK ODA ceiling of around 0.5% of gross national income (GNI). The ODA budget is not planned to return to 0.7% of GNI until at least after 2027-28, and under current policies a significant proportion may continue to be spent within the UK on the accommodation and support of asylum seekers and refugees, which amounted to 29% of all UK ODA in 2022.

How well is the UK supporting the achievement of the global international climate finance goals to which it has committed?

The UK is only one donor among many and its financial contribution to the annual $100 billion global climate finance target is relatively small. However, the UK’s early announcement of its £11.6 billion pledge, its leadership at COP26, its consistent support to UNFCCC negotiators and structures, and its considerable climate investments and programming over the last decade, combined with a domestic programme of climate legislation and emissions reductions, gave it a legitimate claim to climate leadership, with an influence disproportionate to its funding. The pledge gave the UK weight as a trusted and respected leader in discussions and negotiations on global ICF goals.

Although the UK remains committed to achieving the global ICF goals, we heard from external stakeholders that trust in UK climate leadership has decreased as a result of uncertainty about the UK meeting its £11.6 billion commitment, especially with recent changes to how this is measured, as well as its rolling back of domestic net zero policies. The September 2023 £1.62 billion ($2 billion) UK pledge to the Green Climate Fund (GCF), and the fact that the UK remains the second top cumulative pledger (after the US) to the GCF for the period 2015-27, did reinstate the credibility of the UK commitment among many people, according to the government.

Biennial reporting to the UNFCCC and annual ICF results reporting do not fully capture the UK’s ICF impact. While progress on individual projects can be assessed through DevTracker, it is not possible to link and trace this progress to the aggregate reported figures. Neither the aggregation of key performance indicators nor financial reporting capture all UK support provided. Financial data are not completely transparent and are not broken down by annual targets with related reporting on spending. External organisations have not been able to arrive at the same results as the government in calculating the financial implications of the recent changes to ICF accounting. While budget forecasting for the future is of course based on assumptions, civil society organisations have not been able to calculate the effect of the changes on previous spend, such as the BII investments, and did not consider the ‘scrubbing’ for the identification of additional ICF at all, as it was not previously mentioned. Estimating the core contributions to MDBs has also been challenging, as we did not know exactly which MDBs would be receiving which amount of core contributions. While the UK was rated as ‘good’ on the most recent aid transparency index, there is further to go in relation to its climate pledge.

The decline in the perceived leadership position of the UK risks diminishing its ability to drive international support for the global ICF goals by encouraging others to step up their contributions. This comes at a critical time: in 2024, as the scaling up of climate action is becoming ever more urgent, the international community is set to agree on the new global goal for ICF to replace the $100 billion target, known as the New Collective Quantified Goal.

The changes made to meet the £11.6 billion target are likely to have an adverse effect on the UK’s ability to achieve broader ICF objectives, including the promotion of access to climate finance for those hardest hit by the climate crisis, namely least developed countries (LDCs), fragile and conflict-affected states (FCAS) and small island developing states (SIDS). In addition, the UK’s commitments to trebling adaptation finance to £1.5 billion in 2025 and retaining a good balance between spending on adaptation and mitigation are at risk. The UK has recently dropped below the 40% threshold for spending on adaptation as a percentage of the overall total. This is an informal benchmark for membership of the Champions Group of donors, which aims to increase the total level of adaptation finance particularly for the least developed and most vulnerable countries. The Group was launched at the UN General Assembly in 2021 and was strongly supported by the UK during its presidency of COP26.

The share of UK ICF spending that goes towards core contributions to MDBs will be largely lent onward as concessional loans rather than grants. The proportion of climate finance delivered generally through MDBs using the grants modality for both climate adaptation and mitigation was also substantially less than through bilateral donors or multilateral climate funds. The grant portion of World Bank International Development Association financing also fell to 21% by June 2023. The greatest volume of actual World Bank and MDB climate finance is still therefore provided through concessional loan terms. Concessional loans are not the preferred modality of LDCs and SIDS.

So far, the UK has not championed women and girls through its ICF spending, and attention to gender appears to be decreasing over time. In 2021-22, 50% of ICF programming was unassessed or untargeted against the gender marker. This increased to over 60% of ICF programming marked as unassessed or untargeted for 2023-24, despite the prioritisation of women and girls in both the white paper and the UK’s international women and girls strategy.

Recommendation 1: Produce detailed plans to meet the £11.6 billion target

ICF-spending departments should produce a combined detailed internal plan, setting out how much of the remaining spend will be through which channels (multilateral, bilateral, development capital research and development), and how the balance between adaptation and mitigation financing will be reached.

Recommendation 2: Transparency

ICF spending departments should publish an annual report which enables people in the UK and around the world to track whether they are meeting their public commitments on climate finance.

Recommendation 3: Gender

All ICF-spending departments should integrate consideration of gender in their programmes, including by identifying gender-specific programming, using the gender marker where it is relevant, and providing disaggregated reporting.

Recommendation 4: Small island developing states and least developed countries

In line with the white paper commitment, ICF should track the delivery of climate finance to SIDS, FCAS and LDCs.

1. Introduction

1.1 We are at a defining moment in the battle to address climate change, with shifting weather patterns and rising sea levels impacting food production, livelihoods and lives across the globe on an unprecedented scale. Developing countries, which have historically contributed least to the factors that cause global warming, are most at risk from the effects of climate change such as sea level rise, increased temperatures and extreme weather events. For some developing countries such as small island developing states, these effects represent an existential threat.

1.2 The UK is a signatory to the Paris Agreement, an international treaty under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) that aims to limit global warming and strengthen countries’ ability to deal with the adverse impacts of climate change. The UK government has long championed increased funding for climate action in developing countries. In 2009, at the 15 Conference of the Parties (COP15) in Copenhagen, the UK and other developed countries jointly committed to mobilising $100 billion annually by 2020, from both public and private sources, for climate action in developing countries, a goal that was reaffirmed in the Paris Agreement and extended to 2025. This collective commitment was not met by the 2020 deadline. However, on the basis of preliminary and as yet unverified data, the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development believes that “the goal looks likely to have finally been met as of 2022”. At COP26 in Glasgow in 2021, developed countries were encouraged to at least double their collective provision of climate finance for adaptation to developing countries from the 2019 levels by 2025, since the balance between mitigation and adaptation finance had tipped too much towards the former.

1.3 UK international climate finance (ICF) is delivered through the UK’s official development assistance (ODA), and forms part of its contribution towards the annual $100 billion global climate finance commitment to help developing countries respond to the challenges of climate change. The UK has committed to spend £11.6 billion on ICF in the five-year period to 2025-26 in support of this global target.

1.4 ICF contributes to 12 of the UN Sustainable Development Goals, as outlined in Box 1.

Box 1: The UK’s international climate finance and the Sustainable Development Goals

The UN Sustainable Development Goals are a universal call to action to end poverty, protect the planet and ensure all people enjoy prosperity and peace. The UK’s ICF commitments support Goal 13 on climate action, Goal 9 on sustainable industry and infrastructure, Goal 11 on sustainable cities and communities, Goal 12 on responsible consumption and production, Goal 14 on life below water, Goal 6 on clean water and sanitation, Goal 15 on life on land, Goal 7 on affordable and clean energy, Goal 2 on ending hunger, Goal 3 on health and well-being, Goal 1 on ending poverty and Goal 8 on decent work and economic growth.

| Goal 13 relates to taking urgent action to combat climate change and its impacts, including building resilience and capacity to adapt to climate related hazards. Climate finance marked as adaptation falls under this. |

| Goal 9 relates to building resilient infrastructure and promoting sustainable industry. Climate finance for sustainable and resilient infrastructure is relevant to this goal. |

| Goal 11 is to make cities and communities inclusive, safe, resilient and sustainable. Climate finance for cities, infrastructure and transport, as well as resilience and social infrastructure, is relevant to this goal. |

| Goal 12 looks to ensure that consumption and production patterns are sustainable. Climate finance for projects related to industry, business, finance and trade, as well as sustainable infrastructure, is relevant to this goal. |

| Goal 14 is to conserve and sustainably use the oceans, seas, and marine resources for sustainable development. Climate finance for ocean biodiversity, conservation and fisheries is relevant to this goal. |

| Goal 6 aims to ensure the availability and sustainable management of water and sanitation. Climate finance for projects relating to infrastructure, as well as water conservation, is relevant to this goal. |

| Goal 15 covers the protection, restoration and sustainable management of land to reverse degradation and halt biodiversity loss. Climate finance for projects around forestry, land biodiversity and agriculture is relevant to this goal. |

| Goal 7 relates to ensuring access to affordable, reliable, sustainable and modern energy for all. Climate finance for sustainable energy-related projects is relevant to this goal. |

| Goal 2 looks to end hunger and achieve food security through the promotion of sustainable agriculture. Climate finance for sustainable agriculture projects is relevant to this goal. |

| Goal 3 relates to ensuring good health and well-being. Climate finance for projects relating to cities and sustainable transport, infrastructure and sustainable energy, as well as resilient social infrastructure, is relevant to this goal. |

| Goal 1 looks to end poverty. Climate finance contributing towards sustainable agriculture and rural development, as well as resilient infrastructure and industry, is relevant to this goal. |

| Goal 8 looks to promote sustainable economic growth and decent work. Climate finance for projects related to sustainable agriculture and industry is relevant to this goal. |

Purpose and scope

1.5 This rapid review assesses the UK’s progress on its commitments to provide finance to support developing countries to adapt to climate change and mitigate its impact since the start of the financial year 2021-22. The review covers current ICF spending across the UK’s ODA programmes and its forward-looking plans to meet its ICF spending commitments.

1.6 The review seeks to provide a consolidated and publicly available account of actual and projected ICF commitments and disbursements in the period from 2021-22 to 2025-26, to show how well the government is on target to deliver against its commitment to provide £11.6 billion in ICF funding during this five-year period. The review considers the impact of ICF commitments on other parts of UK aid programming, examining the relative trends in climate finance vis-à-vis other UK aid spending. It also assesses the adequacy, predictability and transparency of the UK’s ICF spending in achieving its stated climate and nature goals and in enabling and influencing global climate action. The review makes use of a range of unpublished documentation to add value to what is already in the public domain.

Table 1: Our review questions

| Review questions |

|---|

| 1. Is the UK on track to meet its international climate finance commitments? |

| 2. How well is the UK supporting the achievement of the global international climate finance goals to which it has committed? |

1.7 The rapid review covers all ODA disbursements marked as ICF since 2021-22, the starting year for the current ICF strategy (also known as ICF3). It does not evaluate the implementation of specific ICF-funded programmes. The review is not scored.

2. Methodology

2.1 Our methodology for this rapid review included the following three components:

- Strategy review: a desk-based review of key strategic documents on UK international climate finance (ICF) objectives, priorities, commitments and disbursements. This included a review of relevant advice and briefings submitted to ministers and senior officials on the UK’s priorities and progress against commitments.

- Financial analysis: a review of ICF commitments and disbursements. Financial data were assessed against different dimensions including type of support (adaptation versus mitigation, or both), thematic priority, geography, type of modality (multilateral versus bilateral, grants versus concessional loans), type of partner and type of instrument. This also included a review of the ICF portfolio by department, and of past and future commitments and disbursements to key multilateral partner organisations.

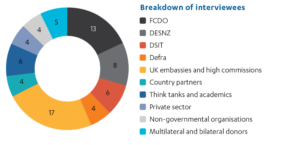

- Stakeholder consultation: interviews with a range of stakeholders (see breakdown in Figure 1) including current and former UK government officials in the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO), the Department for Energy Security and Net Zero (DESNZ), the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (Defra), and the Department for Science, Innovation and Technology (DSIT), as well as bilateral and multilateral partner organisations, developing country partners, and independent experts from think tanks, civil society organisations and the private sector. We spoke with 74 people over the course of the review.

Figure 1: Breakdown of stakeholder interviews conducted

2.2 The report has been independently peer-reviewed. The methodology and sampling process are detailed further in our approach paper. The limitations to the methodology are listed in Box 2.

Box 2: Limitations to the methodology

Scope: Our review scope was kept narrow due to the shorter than usual timeframe (less than five months) to conduct this rapid review. The review takes a high-level look at commitments and disbursements made by four UK government departments during the ICF3 period (2021-22 to 2025-26) and does not evaluate the implementation of any programmes.

Methodological tools: The review does not include an annotated bibliography given its focus on very recent and often unpublished documents. The review builds on previous scrutiny of UK aid to tackle climate change and draws on the latest UK biennial reporting to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change.

Availability of stakeholders: Due to the evidence gathering period coinciding with COP28 and its pre-sessional meetings in November and December 2023, several stakeholders, particularly among bilateral donors and country partners, were not available for consultation.

3. Background

3.1 The UK has long been a major supporter of global action on climate change, noting that access to “more, better, and faster finance” for developing countries, many of which are likely to be the hardest hit by the adverse effects of climate change, is needed “to secure more ambitious and urgent action to promote a clean, green, inclusive, and resilient future”.

3.2 The UK is a signatory to the Paris Agreement, and as such has committed to reporting how much funding it provides to developing countries to address climate change. In its 2020 biennial communication to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), the UK stated that it was “providing certainty to developing countries on the volume of our climate finance”. The UK also set out the ways in which it would work in international partnerships to catalyse wider climate action through its official development assistance (ODA) programme, by mobilising private finance and through working with multilaterals. In its 8th National Communication to the UNFCCC in 2022, the UK restated these ambitions and reconfirmed its commitment to the collective international goal of mobilising $100 billion of climate finance a year through public and private sources to help developing countries fund their adaptation and mitigation actions to tackle climate change. While article 4, paragraph 3, of the UNFCCC called for developed countries to provide “new and additional” resources to developing countries, defining and measuring the extent to which climate finance is new and provided in addition to other development assistance is complicated.

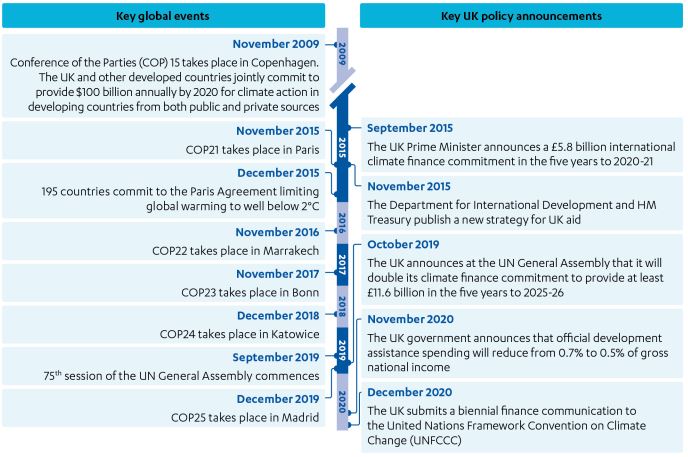

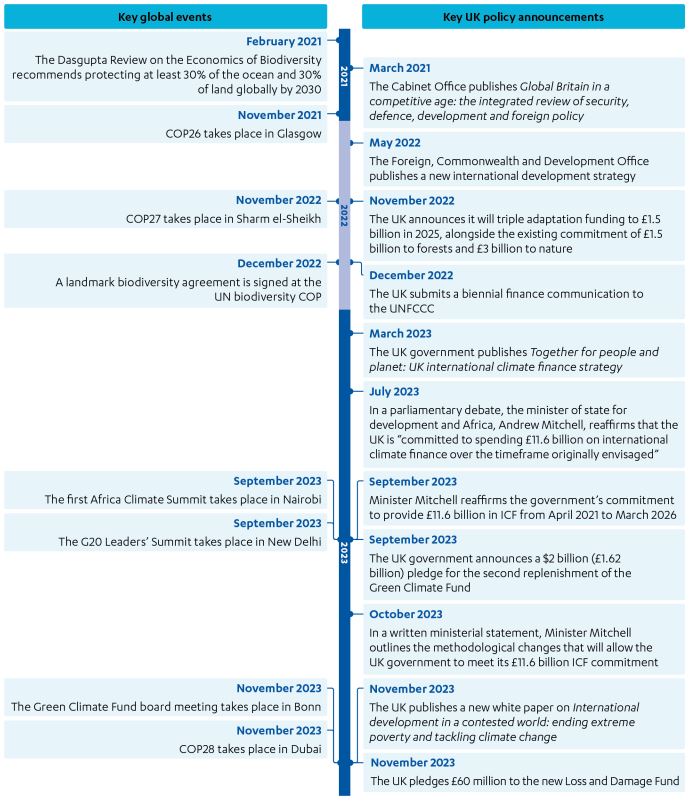

Figure 2: Timeline of the UK’s international climate finance announcements

The UK’s international climate finance commitments

3.3 The UK committed to spending at least £5.8 billion in international climate finance (ICF) in the five years to 2020-21, in support of the annual $100 billion global target. It has met this commitment. In 2019, the UK doubled its ICF commitment for the subsequent five-year period, announcing that it would provide at least £11.6 billion in climate finance between 2021-22 and 2025-26. Reaffirming this commitment at COP27 in November 2022, the UK prime minister announced that within its overall ICF contributions, the UK would triple adaptation funding to £1.5 billion in 2025. This is in addition to its existing commitment to spend at least £3 billion on protecting and restoring nature, including £1.5 billion on forests. The UK’s ICF strategy, released in March 2023, confirmed the commitment, stating that the

“UK is delivering on our pledge to double our ICF to £11.6 billion between 2021-22 and 2025-26, including at least £3 billion on development solutions that protect and restore nature”. In 2023, the Minister of State for Development and Africa, Andrew Mitchell, reiterated this commitment in public statements and it was further confirmed in a written ministerial statement on 17 October 2023.

3.4 As ICF comes from the ODA budget, an assessment of ICF commitments needs to be placed in the context of the 2020 decision to reduce the UK’s annual ODA target from 0.7% to 0.5% of gross national income, as well as the soaring costs of supporting asylum seekers and refugees within the UK in recent years, with almost a third of all UK ODA (£3.7 billion of a total of £12.8 billion) spent in the category ‘in-donor refugee costs’ in 2022. The budget reductions and diversion of aid to refugees and asylum seekers in the UK caused major disruption to the UK aid programme. The UK’s bilateral humanitarian budget is now considerably smaller than its ODA spending on refugee costs in the UK, and this has undermined its commitment to playing a leading role in the international response to global crises. This was seen in the limited UK response both to devastating floods in Pakistan in August 2022 and to the worsening drought in the Horn of Africa.

The UK’s ICF strategic priorities

3.5 The UK’s 2023 ICF strategy confirms that, in addition to contributing to the overall global climate finance target, the UK’s ICF should contribute to the UK government’s four climate and nature goals, covering the themes of:

- clean energy

- nature for climate and people

- adaptation and resilience

- sustainable cities, infrastructure and transport.

3.6 Clean energy remains the most prominent thematic priority for the UK and is a consistent area of funding. This theme is also embedded within each of the other thematic priorities (adaptation and resilience, sustainable cities, infrastructure and transport, and nature for climate and people). Clean energy is represented prominently across all reviewed strategy documents, both in this current period (ICF3) and in the previous ICF2 period covering the five years between 2015-16 and 2020-21. Following the commitment of an additional £3 billion towards nature in 2021, this now includes coastal communities and the marine environment. Sustainable cities, infrastructure and transport remains the least visible of the four themes in strategy documents, and funding for this priority is smaller compared to the others.

4. Findings

Is the UK on track to meet its international climate finance commitments?

The UK government says that it remains committed to delivering on its £11.6 billion pledge, but in the context of reduced aid resources, this has become more challenging

4.1 The UK’s commitment to international climate finance (ICF) is longstanding. During the two previous five-year periods (ICF1 and ICF2) up to 2021, the UK was successful in disbursing its full commitments. It spent its full ICF1 allocation of £3.8 billion between 2011-12 and 2015-16 and its full ICF2 allocation of £5.8 billion between 2016-17 and 2020-21. We found that the UK government also remains committed to meeting its ICF3 pledge of £11.6 billion in the five years from 2021-22 to 2025-26. This commitment was reflected across strategic documentation and in all interviews with government stakeholders conducted for this review. £3 billion of this is to be invested in climate change solutions that protect, restore and sustainably manage nature, of which £1.5 billion would be allocated to forests. The prime minister also announced the tripling of adaptation finance from £500 million in 2019 to £1.5 billion in 2025, as part of the broader commitment of £11.6 billion.

4.2 However, evidence gathered for this review raises doubts as to whether these commitments, notably the adaptation finance commitment, can be achieved (see paragraphs 4.46 to 4.48).

4.3 The UK took a strong leadership position on ICF, including financial pledges, in November 2021, at the 26th Conference of the Parties (COP26) hosted in Glasgow by the UK in partnership with Italy. Some interviewees noted that in the run-up to, and following, COP26, the UK made more visible verbal and financial contributions.

4.4 The UK’s £11.6 billion commitment became more challenging to fulfil after 2020, when the UK announced plans to reduce its official development assistance (ODA) spending from 0.7% to around 0.5% of gross national income (GNI), followed by several rounds of reductions in ODA programming. In 2022, a surge in ODA-funded costs to support refugees and asylum seekers in the UK reduced the amount of ODA available for other priorities by 29% that year. The UK government has committed to returning to spending 0.7% of GNI on ODA when the fiscal situation allows. However, according to the Office for Budget Responsibility forecasts, this is not expected until 2027-28.

4.5 Some ICF programming stalled as a result of the reduction in available ODA, leading, for example, to delays in the implementation of the Just Rural Transition programme and new programmes like the Green Recovery Challenge Fund. However, our document review, financial analysis and interviews all confirm that climate finance spending has been relatively protected from budget reductions compared to other aid sectors. Absolute spending figures across government on ICF have continued to increase year on year and are projected to continue rising – even more steeply towards the end of the ICF3 period (see Figure 5).

4.6 The projected ICF commitments include multilateral, multi-bi and bilateral spend, development capital and research and development commitments. The bilateral share is almost half of the overall commitment (48%). The multilateral share is 30%. An additional share of approximately 22% of bilateral funds is also channelled through multilateral organisations.

4.7 Most recently the UK has made new pledges within the overall framework of the £11.6 billion target, including a substantial £1.62 billion ($2 billion) pledge for the second replenishment of the Green Climate Fund in September 2023 and up to a £60 million ($70 million) contribution for loss and damage, including up to £40 million for the new Loss and Damage Fund at COP28. A number of smaller announcements were made around COP28, although some were traced to previous pledges and others were expected to be implemented beyond the current ICF3 period.

In October 2023 a written ministerial statement provided some reassurance following several months of concern over the UK’s ability and willingness to meet its £11.6 billion ICF commitment

4.8 In mid-2023, leaked internal documentation noted that the UK’s ICF target was off track. The documents discussed the severe risk of reneging on either the overall amount of finance committed, or on meeting the timeline, and highlighted the reputational risk attached to extending the timeline to the end of the 2026 calendar year instead of the 2025-26 fiscal year. External experts also voiced concern that the UK would not meet its target.

4.9 The leaked information was picked up by numerous media outlets in the summer of 2023, with news headlines reporting on the potential failure to meet the £11.6 billion target. Despite the government immediately refuting the claims, there were several months of externally perceived uncertainty between the leaked documents and a formal written ministerial statement (WMS) in October 2023 by the Minister of State for Development and Africa, Andrew Mitchell, reaffirming the overall £11.6 billion target, including an annual breakdown of the estimated allocations that would be made to meet this commitment.

The changes made to the methods used for calculating ICF and efforts to ensure all ICF-eligible spend is included were necessary to enable the UK to meet the £11.6 billion commitment, but moved the goalposts in measuring additional climate finance to developing countries

4.10 To meet the UK’s climate finance commitment, the government opted to adjust its accounting methodology, essentially moving the goalposts for achieving the £11.6 billion. According to data provided to ICAI by the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO), the total reclassified ICF due to these changes is large: £1.724 billion, almost 15% of the total £11.6 billion commitment. The adjustments also included reviewing the ODA portfolio for any existing climate-relevant expenditure that had not yet been tagged as ICF. The changes did not result in additional financing to developing countries, but rather the reclassification of existing ODA as ICF. Overall, the changes did reduce the trade-off between ICF and non-ICF ODA spending, notably in the case of the adjustments to humanitarian funding.

4.11 There are three key changes to the UK’s ICF accounting methods, as well as the identification of additional ICF-eligible programming, each of which is elaborated in greater detail in the ensuing paragraphs. The changes are:

- Multilateral development banks (MDBs): Accounting for the climate-relevant share of future UK core contributions to MDBs. This is expected to provide an additional £746 million of ICF between 2021-22 and 2025-26 according to ICF data.

- Humanitarian funding: Applying a fixed proportion of 30% ICF to humanitarian programmes operating in the 10% of countries most vulnerable to the effects of climate change, using the Notre Dame Global Adaptation Initiative (ND-GAIN) Index, applied both retrospectively and for future humanitarian spending during the ICF3 period. This is expected to provide an additional £497 million of ICF between 2021-22 and 2025-26 according to government data, and reduces the trade-off between humanitarian and ICF spending.

- British International Investment (BII) contributions: Calculating the BII ICF contribution ratio based on actual BII investments, rather than assigning a fixed percentage to ICF as was done previously. This only includes the ODA-eligible core capital contributions from the government to the climate-related projects of BII, not their onward investment (which remains unchanged). The BII adjustments potentially amount to a total of £266 million ICF scored on core capital contributions over the entire ICF3 period, according to government data.

- ‘Scrubbing’ of existing programming: In addition to the changes above, a ‘scrubbing’ exercise of the existing ODA portfolio was undertaken to retrospectively identify additional ICF-eligible programmes, although the exact programmes and time period covered are not clear. Based on an internal document, the government has identified an additional £215 million of ICF in existing aid programmes as a result.

4.12 The inclusion of core contributions to MDBs was a policy change in the UK approach to calculating climate finance. The related financial adjustment will contribute substantially (£746 million) to the fulfilment of the UK £11.6 billion ICF pledge. However, it has not resulted in new resources being committed to the MDBs or developing countries. In fact, contributions to multilaterals were reduced or delayed as a part of the ODA ‘pause’ in 2022. The actual spending of the core MDB contribution will also be delayed, as these allocations are “carried out using promissory notes, which are typically deposited two or more years before they are encashed; however they are counted towards aid expenditure in the year in which they are deposited” the accounting adjustment was justified by the important and growing role that MDBs are playing in climate finance and the fact that other donors also include the climate-related share of their core contributions to MDBs as climate finance.

4.13 The adjustment to the ICF share of humanitarian programming was based on the ranking of the most climate-vulnerable countries according to the ND-GAIN index, which measures the climate vulnerability of countries based on a number of variables. We were told by FCDO officials that the UK concluded that 30% was the correct proportion based on a review of specific programme cases, two of which were included in our request for information. Some other bilateral donors, including France, Germany, the Netherlands and Norway, are assigning a fixed percentage of their climate finance, most commonly 40%, to all ODA programme spending considered to have significant climate change objectives as ICF. In comparison, the UK is taking a more conservative approach.

4.14 BII applies the MDBs’ joint methodology for calculating its ICF contribution in relation to both adaptation and mitigation, according to interviews. BII reports its climate-related financial commitments to the UK government. The government used to take a fixed percentage (30%) as the climate-related share for its own ICF calculations. This has now shifted to the actual proportion of ICF in UK capital in-flows, applied both retrospectively and to future investments. For example, over the full ICF 3 period this actual proportion is forecast to fluctuate between 27% and 46% of core investments (except for the Indo-Pacific investments of £250 million which are ring-fenced and count as 100% ICF). Calculating the BII ICF contribution in line with actual BII investments more accurately reflects what core capital contributions are enabling BII to deliver on climate finance.

4.15 This methodological change results in a more accurate ICF score being assigned to UK core capital contributions to BII, but does not affect the level of outward climate investments made by BII. BII is not a grant-making organisation, but only provides loans, equity investments or guarantees. While the importance of investing and crowding in private capital into the riskiest markets in countries with the highest development needs is recognised, it is not always the most appropriate, realistic, or preferred form of climate finance in the poorest and most fragile contexts. The recent International Development Committee report criticised BII for its poor alignment with UK development objectives and geographic focus on middle income rather than the poorest countries.

4.16 Government interviewees considered the ‘scrubbing’ of the existing aid portfolio as necessary to identify climate-relevant components that had been missed. However, concerns have been raised about the implications for the climate finance actually going to recipient countries. In interviews with ICAI, members of civil society have described the adjustments to the methodology as ‘accounting tricks’, reducing the credibility of the UK’s commitment. While ‘scrubbing’ may be considered necessary by government for the identification of climate-relevant components of the current ODA portfolio, it does not increase the total amount of financing arriving in developing countries. There are also implications also for ICF key performance indicator (KPI) reporting (see paragraph 4.40).

There is insufficient transparency about the adjustments, including the identification of existing expenditure as ICF, for external observers to understand the government’s calculations

4.17 The October 2023 WMS highlighted the substantial policy change relating to the inclusion of core contributions to the MDBs. However, the statement did not mention the accounting for ICF contributions to BII. Neither did it mention including a set proportion of humanitarian spending as ICF, nor the ‘scrubbing’ of the development portfolio to identify additional, already existing ICF-eligible expenditure. The reason given for this was that these were not considered to be policy changes, but administrative adjustments. Two of the three additional adjustments were described by Minister Mitchell in a newspaper article in the Guardian, but not in sufficient detail and the ‘scrubbing’ was not mentioned. The use of different estimation methods (such as different beneficiary MDBs) and the lack of transparency about the adjustments, notably the changes to the ICF accounting by BII, have led to a range of differing estimates made by different stakeholders, as Table 2 below shows.

Table 2: The variations in interpretation of reclassified and additional ICF financing identified through the ICF3 period

| ICF accounting method change | UK government | Carbon Brief | Save the Children | Conservation International |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MDBs | £746m | £200m per year = £600m | £920m | £600m |

| Humanitarian | £497m | £449.1m | £542m | £450m |

| BII | £266m | Will be applied in future only | £159m + £92m = £251m | Between £400m - £800m with a central estimate of £600m |

| 'Scrubbing'* | £215m | Not available | Not available | Not available |

| Retrospective allocation** | Not available | Not available | Not available | £464m |

| Total | £1,724m | £1,049m | £1,713m | £2,114m |

*’Scrubbing’ identifies additional, already existing ICF eligible expenditure

**Conservation International calculated the potential retrospective allocation using various publicly available sources. Conservation International was the only organisation to calculate possible retrospective increases during the ICF3 period.

As ICF is backloaded, achieving the spending targets now relies on the methodological changes, continuing existing programmes and developing new programmes

4.18 The backloading of ICF spending within the five-year ICF3 spending period is so substantial that interviewees have raised concerns that it may prove impossible to deliver. After the 2021 spending review, departments tried to increase ICF spending gradually year on year. Increasing the spend each year has been challenging due to several rounds of ODA reductions since 2020, a pause in FCDO ODA spending from June to November 2022 caused by the unexpected and dramatic rise in ODA spent on in-donor refugee costs that year, and increasing demands on the ODA budget from a rise in conflicts and humanitarian crises across the world. These pressures on the ODA budget, particularly FCDO’s budget, meant that ICF spending became further backloaded. 55% percent of the entire ICF3 spending target is now due to be met through spending in the last two years (as opposed to 53% in the original plans). The year-on-year increase in the last ICF financial year, 2025-26, is particularly striking at 32%. FCDO’s planned ICF spend in 2025-26 is about 2.6 billion, which would be 27% of the department’s entire ODA share of about £9.7 billion that year. However, the upcoming spending review will determine the final proportion of FCDO’s overall spend ODA allocation.

4.19 The proportion of programmes under development remains substantial. In Figure 3, the red boxes indicate programmes under development (including both programmes with an approved concept note and planned budgets that are not yet at concept note stage). One internal planning document states that “between 89% – 92% of the £11.6 billion is already planned (although the proportion that is approved is lower at 68%)”. However, our assessment of the financial data indicates that only 57% of the target spend for the three final years of ICF3 is approved, with about £3.3 billion worth of programmes under development. 86% of the programmes in the ICF portfolio are either under implementation or approved. Many of these have future budget lines assigned to them, indicating intent to scale up or perhaps restart paused projects. However, there is still a lot of money to channel through existing or new programmes in a short space of time (that is, the 14% of the portfolio that is unapproved). According to the government, there is “no expectation that the 14% will go through new programmes”. Other internal documentation also refers to the unlikelihood of being able to stand up enough new programming in the remaining timeline.

Figure 3: Actual spend and programmed amounts for the ICF3 period across all aid spending departments

4.20 The challenge is recognised by government stakeholders. According to internal FCDO guidance, for FCDO to increase spending speed, all spending teams will need to protect existing ICF programmes and plan for a scale-up of existing ICF programmes and new ICF programmes in 2024-25 and 2025-26, especially adaptation programmes.

4.21 This guidance may clash with other priorities for ODA spending in the coming years. The period since the ODA budget reductions which started in 2020 has seen a range of urgent ODA needs apart from climate funding, such as Covid-19, Afghanistan, Ukraine, Sudan, and now Gaza, as well as debt relief. Given growing insecurity and conflict around the world, new emergencies are expected to arise in the remainder of the ICF3 period to 2025-26. Finding the ODA to scale up ICF spending is also made difficult by the pressures on the aid budget caused by ‘in-donor refugee costs’, in particular due to the Home Office’s failure to manage the costs of asylum accommodation effectively. In 2022, in-donor refugee costs became by far the largest ODA spending category (29% of all UK ODA that year).

4.22 Adding uncertainty, the final period of ICF3 will come after the next general election, which may result in new political priorities and administrative delays following new appointments. A new spending review may alter the planned spending trajectory. The prioritisation of programme development and delivery is also subject to the political will of current and future governments, with implications for the spending trajectory.

In addition to the changes to accounting, backloading requires the government to quickly ramp up new ICF multilateral commitments as well as bilateral programming

4.23 While the accounting adjustments allow a significant increase in ICF funding without extra programming or commitments, it is not enough to reach the £11.6 billion target. The UK government will also need to accelerate existing and new ICF commitments. This may be done through multilateral channels such as increasing core contributions to MDBs and international climate funds, increasing development capital, such as capital contributions to BII, increasing research and development, scaling up other existing programmes, or launching new, large-scale bilateral ICF programmes in the next 12 to 18 months.

4.24 ICAI’s financial analysis shows that directing ICF through multilateral channels will allow the rapid recording of increased ICF commitments. In a policy shift from the 2022 aid strategy, the proportion of ICF channelled through both multilateral and so-called ‘multi-bi’ commitments grew over the period of ICF3 (see Figure 4).

Figure 4: The provisional split between multilateral and bilateral spending across ICF3

4.25 Using multilateral channels to increase ICF flows allows the government to circumvent its human resource capacity challenges to some extent. However, although core multilateral contributions provided the largest share of additional funds towards meeting the £11.6 billion target, there is still a need for a substantial share of bilateral programming (as shown in Figure 4 above). Indeed, the bilateral spend forecast for 2025-26 is double what was spent in 2022-23, which will increase the pressure on government capacity to extend old programmes and launch any new ones.

4.26 While human resources dedicated to ICF have increased, the government will nevertheless struggle to deliver a heavily backloaded programme of bilateral ICF spending. Overall resources for climate change programming increased following the merger between the former Department for International Development (DFID) and the former Foreign and Commonwealth Office (FCO) into FCDO, from one deputy director and about 40 to 60 staff in the Environment and Climate Department at DFID, to two directors (Senior Civil Service 2), seven deputy directors and 157 staff positions in the Directorate in FCDO. However, these are not full-time equivalent positions and some remain vacant. Taking account of part-time working, the full-time equivalent staff number falls by 4.8 and there is currently a 12% vacancy rate. In 2021, ahead of COP26, the government made an effort to estimate the fulltime equivalent of the overseas network of climate, energy and environment attachés, numbering it at 462 UK diplomatic staff and country-based staff (190 full-time equivalents).

4.27 The ability to scale up existing bilateral ICF programming is also restricted by procurement timelines and the unwillingness of some government staff to start new programmes unless there is a strict ring-fence around ICF funding. Based on the interviews undertaken for this review, the experience of the drastic reductions in 2021 ODA spending, and the adverse impact this had on frontline programming, with many programmes paused or terminated, has left some staff in-country concerned about developing programmes without sufficient funding guarantees. Overall, there appears to be significant uncertainty about the degree to which the remaining two years of ICF3 bilateral spending are programmed.

While the objectives of international development and climate finance are closely intertwined, some trade-offs between ICF and non-ICF ODA priorities remain inevitable

4.28 In the 2022 international development strategy the government committed to align all new bilateral UK ODA with the Paris Agreement in 2023, and to build on the 2021 commitment to ensure all new UK bilateral aid spending does no harm to nature by taking steps to ensure UK bilateral ODA becomes ‘nature-positive’, in line with the international goal to halt and reverse biodiversity loss by 2030, and the post-2020 Global Biodiversity Framework. At the same time, the government recognises that considering ICF as ‘new and additional’ funding is difficult to defend in the face of reductions in available ODA. The need to significantly scale up ICF with reduced headroom will mean that other areas such as education, health, and humanitarian response will inevitably receive less funding.

4.29 Keenly aware of the implication for non-ICF bilateral ODA, the government has reduced the proportion of ‘new spending’ going to ICF in the total ODA budget through the changes described in paragraphs 4.10 to 4.16 above that allow a larger proportion of UK ODA to be labelled as ICF without increasing the actual committed spend to ICF. For example, the government now applies a fixed proportion of 30% ICF to humanitarian programmes operating in the 10% of countries most vulnerable to the effects of climate change. This partially protects some elements of the non-ICF ODA budget and lessens the trade-off between ICF or humanitarian spend as some ODA is both.

4.30 Figure 5 below shows that the projected ICF proportion of total ODA in 2025-26 was originally 35% in May 2023 (see grey line) but was revised down to 28% in November 2023 (see yellow line) following the changes.

Figure 5: ICF as a proportion of ODA according to projections made in May 2023, then revised in November 2023

Source: HMG data and Autumn budget and spending review 2021, HM Treasury, October 2021, link

Note: The ICF spend is derived from HMG data. Total ODA projections up to fiscal year 2024-25 are those cited in the 2021 Spending Review while the total ODA projected for 2025-26 is derived from internal HMG data. Quarterly GNI projections are available through the Office for Budget Responsibility (link), however, given the difficulties estimating projected GNI (see Management of the 0.7% ODA spending target, link), we use the figures already published in the 2021 Spending Review. Total ODA figures for calendar years past are published annually in the SID data, however not by fiscal year.

4.31 However, even this new projection remains a huge increase from the baseline of 14.5% in 2021-22. The government, parliamentarians, civil society organisations and external experts all highlighted the risk that sufficient resources might not be available towards the end of the ICF3 period to meet other ODA needs, particularly if there are new, unforeseen crises.

How well is the UK supporting the achievement of the global international climate finance goals to which it has committed?

The UK has long held an international climate leadership position

4.32 While the UK is only one bilateral donor among many and its financial contribution to the annual $100 billion global goal is relatively small, it had established a global leadership position on ICF. This position was supported by the early announcement of the substantial £11.6 billion pledge in 2019. The UK’s leadership at COP26 in 2021, its consistent support to United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) negotiators and structures, and its considerable climate investments and programming over the last decade, combined with a domestic programme of climate legislation and emissions reductions, gave the UK a legitimate claim to climate leadership, with an influence disproportionate to its funding. This gave the UK weight as a trusted and respected leader in discussions and negotiations on global ICF goals, a role that was unequivocally recognised by all the 74 stakeholders we interviewed.

UK international climate leadership has been adversely impacted over the past year, including by changes in the UK’s domestic net zero commitments

4.33 Announcements by the prime minister in 2023 affecting the UK’s domestic net zero commitments, such as support for new oil and gas exploration and delaying the phasing out of petrol and diesel cars and gas boilers, have contributed to the decline in the UK’s global leadership position, according to external stakeholders interviewed for this review. The interim chair of the independent climate watchdog, the Committee on Climate Change (CCC), Professor Piers Forster, noted after the prime minister’s speech on net zero on 20 September 2023:

“Our position as a global leader on climate has come under renewed scrutiny following the prime minister’s speech”

4.34 The UK government cross-references its domestic and international work on climate in its public communications, using domestic net zero climate policies and achievements to bolster its international credibility on climate action and its commitment to ICF to bolster its domestic net zero credentials. This can be seen, for instance, in the references to ICF in the UK’s 2022 8th National Communication to the UNFCCC on the country’s action to address climate change, and in the March 2023 ICF strategy which in turn refers to the UK’s domestic legislation and strategy for net zero, and the UK’s Nationally Determined Contribution – meaning its own domestic plans to cut carbon emissions. However, when domestic ambitions are reduced, this cross-referencing approach can contribute to lowering the UK’s international reputation.

4.35 Lord Stern made a statement in the House of Lords, saying:

“The government’s backsliding on climate action is a deeply damaging mistake, damaging for the UK, the world and the future of us all, founded on a whole series of muddled and incorrect arguments… I have been asked by many investors and policymakers in the United States, India, China, Africa, Europe and beyond what the UK thinks it is doing. Our hard-won leadership and respect, established through our climate legislation, emissions reductions, and our successful COP26, are being eroded or thrown away”

4.36 Media reporting further reflects that the decline in trust extends beyond concern about meeting the £11.6 billion target to cover perceptions of UK commitment and leadership on climate change and environmental issues more broadly. The government has sought to address these perceptions, for example in the prime minister’s national statement at COP28 which stated that “the UK is totally committed to net zero, the Paris Agreement and keeping 1.5 alive”. The statement described the UK’s domestic approach as “a new pragmatic approach”.

Reporting on the £11.6 billion target is not fully transparent

4.37 The UK’s commitment to aid transparency is a matter of public record, most recently reiterated in the November 2023 international development white paper, which states that the UK “will model transparency in how we shape and deliver our development offer”. ICAI reviewed UK aid’s transparency in October 2022 and, finding a recent decline, recommended that FCDO achieve a standard of ‘very good’ on the Aid Transparency Index by 2024 (up from ‘good’ in 2022). This was accepted by FCDO.

4.38 The UK reports climate finance spending data across platforms including DevTracker (listed by project or programme, and disaggregated by gender, age and disability where possible). The UK has published an annual report on the ICF KPIs since 2016 via gov.uk, and it provided a summary of 11 of the KPIs from 2011 to 2022 in July 2023. UK ICF rules require that programmes counted as ICF must report on progress on at least one of the climate finance KPIs. It is not clear how or whether ICF KPIs will be adjusted as a result of the ‘scrubbing’ exercise in 2023-24. There has never been an external review of the ICF KPIs, which are scored internally by the departments responsible for the spending. The KPI reporting does not fully capture what UK climate finance is achieving, nor does it specifically address its large multilateral commitments.

4.39 A section on ICF in the UK’s 8th National Communication provides a high-level overview and programme examples. The UK also reports on ICF through its biennial finance communication to the UNFCCC, most recently in December 2022.

4.40 However, these sources do not add up to an overall picture on what the UK is doing to meet the ICF objectives or how programming links to evolving strategy. The new March 2023 ICF strategy refers to wider international climate and environment policy goals and has four themes, sometimes referred to as pillars. The pillars include high-level objectives, but the strategy does not articulate how the ICF KPIs are aligned with these high-level goals. The only reference to the KPIs in the ICF strategy is a list of 11 KPIs on the last page of the document. None of these KPIs appear to directly address the fourth pillar on sustainable cities, infrastructure and transport. The strategy has 15 mentions of “marine” and 12 mentions of “ocean”, but none of the KPIs relate specifically to the marine environment.

4.41 In the absence of fully transparent information in the public domain, a recent Carbon Brief analysis of the WMS by Minister Mitchell in October 2023 relied on a combination of DevTracker data and a previous freedom of information request in order to assess what spending had been ‘found’ and retrospectively added to the UK’s ICF in previous years as a result of the changes in what is now being counted as ICF. As explained above in paragraph 4.17 and Table 2, this review also considered assessments conducted by Save the Children and Conservation International UK. None arrived at the same estimates for the financial implications of the changes, although the estimates of adjustments to the calculation of the climate-relevant share of humanitarian programming were relatively close, within 10% of the calculated average of climate-relevant expenditure assigned after the adjustment. Although FCDO officials told us that media reporting at this time was not accurate, the absence of information to correct this lends further weight to the need for more transparent information.

Stakeholders expressed concern that the recent reputational decline could affect the UK’s ability to encourage others to commit to more ambitious climate finance targets, notably the New Collective Quantified Goal

4.42 Many interviewees for this review expressed concerns about the UK’s reputational decline in line with those highlighted above in paragraphs 4.32 to 4.40. Interviewees were worried about the impact this might have on the UK’s ability to influence or lead discussions on more ambitious climate finance targets, notably the New Collective Quantified Goal. This is the new global climate finance goal, with a floor of $100 billion, that needs to be agreed this year.

Stakeholders observed that the accounting changes mean that the UK is no longer considered ‘first among equals’ in the donor community, or a champion of higher standards for UNFCCC reporting

4.43 Defining the UNFCCC standard of ‘new and additional’ ICF is difficult, and there is no formal agreed protocol on reporting it internationally. The UK had been acknowledged as a leader in strengthening UNFCCC reporting standards, by adhering to clearer and more limited definitions of climate finance that made it easier to assess if funding was indeed ‘new and additional’, as is expected of ICF. However, the recent changes in the UK’s ICF accounting, including imputing a share of both multilateral and humanitarian spending, mean that it can no longer be ‘first among equals’ among donors. This was recognised by most government officials we interviewed.

4.44 The accounting changes have brought the UK into line with the practice of other bilateral donors that have been using these approaches. With these changes, the UK is taking a different approach to the accounting and reporting of ICF. The mainstreaming of climate considerations into development programming, while necessary, will also contribute to making it harder to identify climate finance and to know whether the funding is indeed ‘new and additional’.

The shift towards MDBs is not in line with the UK’s 2022 aid strategy and because it reduces the proportion of grant funding channelled onward to developing countries, it is less suitable for supporting countries that are most vulnerable, least developed, conflict-affected, or small island developing states

4.45 The UK has recently shifted back to using MDBs as a more significant delivery channel for climate finance, although bilateral funding will remain important (see Figure 4). While using these channels enables substantial leverage of additional finance, notably from the World Bank International Development Association (IDA), with a proportion of 1:4 between donor grant investments and IDA concessional finance lent onward, this is not in line with the 2022 aid strategy, where the UK government said it would substantially rebalance its aid funding from multilateral channels.

4.46 It also contradicts the UK’s commitment to the UNFCCC to deliver high-quality aid to developing countries in the form of grants. While spending through MDBs will require less FCDO staff time, it also has downsides. The UK will count its contributions to MDBs as grants but the MDBs will mainly pass these onward to countries as concessional loans. The proportion of climate finance delivered generally through MDBs using the grants modality for both climate adaptation and mitigation was also substantially less than through bilateral donors or multilateral climate funds, with MDB grants accounting for 15% for adaptation and less than 5% of their mitigation efforts. Using the World Bank IDA as a case in point, according to the World Bank web page, while “more than half of active IDA countries already receive all, or half, of their IDA resources on grant terms”, the grant portion of the actual volume of financing was between 11% to 24% between IDA 17 and IDA 18, falling to 21% by June 2023, based on other World Bank documentation. Therefore the greatest volume of actual World Bank financing, as well as that of other MDBs, is generally still provided through concessional loan terms. Documents and interviewees confirmed that multilateral, concessional loans are not the preferred modality of low-income countries (LDCs) and small island developing states (SIDS). This was recognised in the UK’s December 2022 reporting to the UNFCCC, which stated on page 8 that:

“Grants represent a favourable option for SIDS, LDCs and fragile states, as countries within these three groups often present economic and socio-political conditions that do not favour alternative forms of finance (such as loans) due to limited absorptive and repayment capacity”

The ratio of UK adaptation support compared to mitigation has declined over time and the channelling and programming of adaptation support remains a challenge

4.47 The UK is committed to tripling its adaptation finance to £1.5 billion in 2025: “the UK recognises that the current provision of adaptation finance remains insufficient to respond to worsening climate change impacts”. At COP26 in Glasgow, the UK, alongside Fiji, convened the Taskforce for Access to Climate Finance. The primary aim of the taskforce is to improve access to climate finance for climate-vulnerable developing countries. The UK is also a member of the Champions Group, which aims to increase the total level of adaptation finance particularly for LDCs and SIDS. The Group was launched at the UN General Assembly in 2021 and was strongly supported by the UK during its presidency of COP26.

4.48 However, in recent years the UK has not sustained the balance between mitigation and adaptation. The proportion of adaptation financing decreased from the 47% reported between 2016 and 2020, to below 40% in 2023, which is below the informal benchmark prescribed for membership of the Champions Group. If the UK is to adhere to its adaptation commitments, any remaining unprogrammed bilateral FCDO ICF will need to go predominantly towards adaptation finance. Otherwise, the UK’s position in the Taskforce or Champions Group could be subject to doubt, and in turn may reduce influence on other donors.

4.49 While it is acknowledged that public finance will not be enough to meet the adaptation and resilience needs of climate change, using private finance to fill the gap remains challenging. Choosing BII and MDBs to channel finance will make support to adaptation and meeting the needs of the poorest more challenging given the emphasis on investing in bankable projects which is linked to their traditional tendency to support mitigation more than adaptation. Efforts related to attracting private finance to climate adaptation are growing. For example, BII’s support to the Adaptation and Resilience Investors Collaborative is positively influencing other donors, and BII’s Catalyst Strategies and Climate Innovation Facility mean that it now has more tools to look at earlier-stage climate-focused businesses and deliver adaptation finance. Although there are some successful cases where private finance is being used for adaptation, multiple barriers persist.

The government’s adjusted approach to ICF does not pay sufficient attention to the countries most in need

4.50 The public statements by the UK government on the importance of prioritising LDCs and SIDS are clear. For example, the November 2023 white paper states that, under the UK’s commitment to climate and nature finance, “we will focus on LDCs, SIDS and countries with the highest humanitarian need”. The final category also encompasses fragile and conflict-affected states (FCAS). The white paper also states that “the UK will aim to spend at least 50% of all bilateral ODA in the LDCs. This focus will inform all our ODA spending”. However, documents and government stakeholders were clear that there is no geographic prioritisation for ICF funding as such, nor is ICF financial data disaggregated by LDC/FCAS/SIDS categories or by country income levels. While it may be challenging to attribute UK spend to specific countries, as programming often spreads across multiple countries, this makes the prioritisation and monitoring of that prioritisation even more important. As explained in paragraphs 4.45 and 4.46, the shift to channelling ICF through MDBs may mean that more finance is passed on to LDCs and SIDS as concessional loans rather than grants, which is not the preferred modality for these countries.

The government’s International Development Strategy and white paper identify women and girls as high priority, but the UK has not championed gender issues or gender-sensitive approaches through ICF

4.51 Women and girls already face inequalities and discrimination because of their gender, and this is compounded when disasters strike. Climate change-related crises can increase, among other things, the risk of violence against women and girls, the likelihood of dropping out of school and the risk of child marriage. Extreme weather events due to climate change disproportionately affect women and girls and their ability to perform their everyday tasks such as collecting firewood and water. Men may migrate to urban areas in search of employment, but women are left behind to look after the land and household.

4.52 The November 2023 white paper has 48 references to women and girls and describes how “the UK’s work on women and girls is paramount”. However, based on the financial analysis conducted for this review, we found insufficient attention to the mainstreaming of gender in ICF and noticed that attention to gender appears to be decreasing over time. Currently 48% of ICF programmes do not apply the gender marker, despite the prioritisation of women and girls in both the white paper and the UK’s international women and girls strategy. The latter states:

“In practice, all new ICF programmes should be designed to score at least a 1 against the Gender Marker, unless this is not possible due to the nature of the programme”

5. Conclusions and recommendations

5.1 Tackling climate change in developing countries through international climate finance (ICF) has long remained a major priority of the UK, and the government has repeatedly reiterated that it remains committed to delivering on its £11.6 billion pledge. However, meeting this commitment is now contingent upon several changes made in 2023 to the way the UK accounts for its ICF spend, allowing more aid spending to be counted as ICF. Essentially this just ‘moved the goalposts’ for measuring additional climate finance to developing countries. The changes reclassified existing ODA as ICF. Crucially, they did not entail allocating additional financing to developing countries. Furthermore, ICF is likely to provide less assistance to the countries most in need after these changes, as the UK will count its contributions to MDBs as grants which MDBs will mainly pass onward to LDCs and SIDS as concessional loans. Evidence from documents and our interviews showed that concessional loans are not the preferred modality for these countries. There is also insufficient transparency about the new accounting, making it difficult to hold government to account for its climate finance commitments.

5.2 While there was always a projected increase in ICF commitments toward the end of the programming period, 55% of the committed spending is now planned for the two final years of the five-year period (as opposed to 53% in the original plans). Serious concerns remain over whether the backloaded ICF spending plan can still be delivered. Reaching the £11.6 billion target relies on the changes, as well as a mix of new and old (continued) programmes.

5.3 Overall, the accounting changes did reduce the trade-off between ICF and non-ICF ODA spending, notably in the case of humanitarian aid. The changes have allowed more of the UK’s existing aid programmes to be counted as ICF, thus to some degree protecting aid budgets in areas such as humanitarian funding. Contrary to media reports in July 2023 that 83% of the aid budget would have to be spent via ICF to meet the £11.6 billion target, it was actually only 35% in May 2023 and was further revised down to 28% through the accounting changes. However, the scale of the backloaded ICF target inevitably means that substantial trade-offs remain between ICF and non-ICF priorities, including humanitarian aid, so long as the overall ODA budget remains limited.

5.4 The UK has long held a leadership role internationally on climate but this has been adversely impacted over the past year, due to concerns about the UK’s ability and willingness to meet the target, the changes to the way the £11.6 billion target is calculated, and the changes in domestic net zero commitments. Stakeholders expressed concern that a reputational decline could affect the UK’s ability to leverage and encourage others to commit to more ambitious climate finance targets, notably the New Collective Quantified Goal. The UK is no longer considered ‘first among equals’ in the donor community, and its own accounting changes means it is no longer a champion of higher standards for United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) reporting.

5.5 The shift towards relying on multilateral development banks as an important funding channel for ICF is not in line with the UK’s 2022 aid strategy and is less suitable for supporting countries that are most vulnerable, least developed, conflict-affected, or small island developing states. The ratio of UK adaptation support compared to mitigation has decreased over time and the programming of adaptation support remains a challenge. The government’s adjusted approach to ICF does not pay sufficient attention to the developing countries most in need because it represents a shift towards the channelling of concessional loans rather than grants to developing countries. Monitoring systems are also not yet in place to ensure that ICF is directed to least developed, conflict-affected and small island states. The government’s International Development Strategy and white paper identify women and girls as high priority, but the UK has not championed gender issues or gender sensitive approaches through ICF.

Recommendations

Recommendation 1: Produce detailed plans to meet the £11.6 billion target

ICF-spending departments should produce a combined detailed internal plan, setting out how much of the remaining spend will be through which channels (multilateral, bilateral, development capital research and development), and how the balance between adaptation and mitigation financing will be reached.

Problem statements

- The UK’s commitment to meeting the £11.6 billion target was seriously in doubt during the first three quarters of 2023.

- There is substantial backloading of ICF spending to 2024-25 and 2025-26.

- Some staff that have experienced ODA budget reductions are concerned about developing programmes without sufficient funding guarantees.

- There has been particularly slow progress on adaptation finance.

Recommendation 2: Transparency

ICF spending departments should publish an annual report which enables people in the UK and around the world to track whether they are meeting their public commitments on climate finance.

Problem statements