International Climate Finance: UK aid for low-carbon development

Score summary

UK International Climate Finance shows a convincing approach to promoting low-carbon development, with some good emerging results on influencing other financial flows and a significant investment in results management and learning. However, there is a need to update the overarching strategy, with greater clarity on low-income countries, and for a stronger public narrative to support demonstration and influencing.

The UK has made a strong commitment to joint international action on climate change. Over half of its £5.8 billion budget for climate finance is expected to be spent through core contributions to multilateral international climate finance and other multilateral channels between 2016- 17 and 2020-21. It makes strategic choices about which international funds and initiatives to support, helping to build a more coherent international climate finance architecture and to increase its influence over investment choices. Its support is aligned with developing country priorities. BEIS focuses its investments on countries with rapidly growing emissions, which tend to be middle-income countries. DFID has a convincing approach to supporting low-carbon development in the energy sector. However, it lacks a clear strategy for promoting low-carbon development in other sectors. DFID is progressively integrating low-carbon investment across its portfolio but has not approached the integration process in a systematic way, which may lead to a loss of focus and momentum. The overall strategy for UK International Climate Finance has not been updated since 2011, leaving key elements of the approach unclear and potentially opening up a strategic gap around support for low-income countries.

The UK has used its influence with multilateral climate funds well, backing its financial support with quality technical inputs. It has helped improve the quality of their work in a number of areas, including project quality, engagement with the private sector and building organisational capacity. In our sample of nine BEIS and DFID programmes, we saw a good range of results around capacity building, demonstration of new technologies and business models, and in mobilising private investment. There is emerging evidence that this is contributing to transformational change in partner countries. However, a falling away in visibility and external communications around UK International Climate Finance may be inhibiting the achievement of its demonstration and influencing objectives.

UK International Climate Finance has been a strong champion of a greater results focus in multilateral climate funds and has invested in a range of learning initiatives. It has developed a set of key performance indicators, enabling it to track aggregate results in a number of areas. The data from key performance indicators does not appear to be informing portfolio management and while there are learning components within many individual programmes, there has been no systematic process for capturing and sharing lessons across the portfolio. However, a central monitoring, evaluation and learning contract is now undertaking some portfolio-level thematic evaluations that are expected to inform future programming.

| Individual question scores | |

|---|---|

| Question 1 Relevance: Does the UK’s approach to low-carbon development reflect the needs of developing countries and its international commitments to climate finance? |  |

| Question 2 Effectiveness: How effective is UK International Climate Finance at promoting investment in low-carbon development? |  |

| Question 3 Learning: How well do UK investments in low-carbon development promote and reflect learning and evidence? |  |

Executive summary

Under the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), 184 signatory countries agreed to take urgent action to keep the global temperature rise well below 2°C above pre-industrial levels (the level above which catastrophic and potentially irreversible harm is predicted) and to pursue efforts to limit the increase to 1.5°C. As well as cutting their own carbon emissions, developed countries jointly committed to mobilising at least $100 billion per year from public and private sources by 2020 to help developing countries adapt to climate change and minimise their future emissions.

The UK is a major supporter of global action on climate change, having committed at least £5.8 billion in UK aid over the five-year period to 2021. The UK aims for an even split between mitigation (working to reduce emissions) and adaptation (helping developing countries adapt to the impact of climate change). The UK is also investing in projects to halt deforestation, which support both mitigation of and adaptation to climate change. These resources come from the budgets of the Department for International Development (DFID), The Department of Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy (BEIS) and the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (Defra), and are known collectively as UK International Climate Finance.

In this review, we assess the contribution of UK International Climate Finance since 2016 to promoting low-carbon development (mitigation) in developing countries – that is, helping them shift to patterns of development that minimise future emissions while still achieving their development goals. Helping to shift countries to patterns of low-carbon development cannot be funded from development aid alone. It calls for public and private investment on a vast scale and in many areas, from transitioning energy systems to the greening of rapidly growing cities. Our focus is therefore on how well the UK has contributed to mobilising other climate finance and scaling up private investment.

This performance review explores the coherence of the UK’s overall approach to low-carbon development, how successful it has been at influencing other contributors and whether it is learning and adapting. The review involved case studies of many aspects of the portfolio, with visits to the headquarters of two of the major UK-supported multi-donor initiatives. We did not, however, examine individual programmes overseas.

Relevance of the UK approach to low-carbon development

The UK has made a strong commitment to joint international action on climate change, directing two thirds of its climate finance through core contributions to multilateral international climate finance and other multilateral channels between 2016-17 and 2017-18. The scale of the investment adds weight to the UK’s advocacy for more climate funding from other OECD countries. It also enables the UK to influence how others’ climate finance is spent.

We find that the UK has made strategic choices about which multilateral initiatives to support, helping to build a more coherent climate finance architecture. It is now the third-largest contributor to the Green Climate Fund, which it regards as a key mechanism for funding implementation of the UNFCCC in developing countries. It also supports a range of other funds and initiatives, each with a distinct contribution to the rapidly evolving field of international climate action.

UK International Climate Finance shows awareness of the importance of promoting partner country leadership and ownership of climate action. In its contributions, the UK has prioritised several multilateral climate funds and multi-donor initiatives that support nationally led plans and priorities. There are well-designed processes to ensure that investments match national priorities. As many developing countries are still at an early stage in identifying their preferred approach to low-carbon development, the UK also provides technical assistance to help put in place national policies and strategies and to identify priority investments.

BEIS has chosen to focus its investments on countries with rapidly growing emissions, which tend to be middle-income countries. There is a clear rationale for this: middle-income countries contribute much more to global emissions than low-income countries, and emissions have an equal impact on the global poor, wherever produced. BEIS recognises, however, that middle-income countries have a greater capacity to finance the transition to low-carbon development than lower-income countries. Where BEIS funding is used by development partners in middle-income countries, this is mainly for concessional loans for project implementation. Grant support in these countries is largely limited to technical assistance. BEIS has a convincing strategy for working in countries or sectors at different levels of market maturity. Where markets are underdeveloped, the focus is on building capacity and trialling new technologies and business models. In more mature markets, the priority is to create the conditions for scaling up private investment – for example by helping to meet the costs of project design and using UK finance to reduce risks for private investors. Through its funding, BEIS also aims to create secondary benefits for UK firms.

DFID has a credible strategy for its investments in the energy sector, which accounts for the majority of its aid spending on low-carbon development. An energy policy framework from 2015 has ‘enhancing environmental sustainability’ as one of its objectives, including by helping developing countries with limited existing energy infrastructure ‘leapfrog’ to clean energy, reduce fossil fuel subsidies, promote off-grid energy solutions and invest in energy-efficient cities and buildings. To this end, it works with partner countries on policy, planning and regulatory reform and invests in the testing and scaling up of innovative technologies and business models. DFID has not developed strategies or guidance on low-carbon development in other sectors.

Since 2014, DFID has progressively shifted from large, dedicated climate programmes to integrating climate action across its portfolio. There is a good case for this: low-carbon development is a principle that cuts across all development assistance. However, we find that DFID has not approached the integration process in a convincing way. There is no explicit requirement for new programme designs to incorporate low-carbon development objectives and there is a lack of leadership, guidance and central support. This creates a real risk that DFID’s low-carbon development work will become fragmented and lose momentum. However, DFID does better than most donors at accounting for its climate expenditure, which is tracked through its management information system.

There is no up-to-date strategy for UK International Climate Finance as a whole. A strategy from 2011 has not been updated and its current status is unclear. There is only an unpublished ‘new narrative’ established in 2017 that articulates at a high level what UK International Climate Finance is seeking to achieve within a broader context of international climate finance commitments. Key aspects of the UK approach – including its sectoral and geographical priorities and the link between low-carbon development and poverty reduction – have not been articulated. This risks undermining the strategic coherence of the UK’s funding. In particular, the approach to low-carbon development in low-income countries, in support of the UK position in international climate negotiations, is not clear.

Overall, there are strong elements to the UK approach to low-carbon development, meriting a green-amber score. While BEIS has a clear strategy for promoting low-carbon development in countries with large or rapidly growing emissions and DFID has a clear strategy for the energy sector, DFID’s approach to integrating low-carbon development across its portfolio more generally is unconvincing. Care needs to be taken to ensure the portfolio remains coherent and aligned with the UK’s strategic objectives.

Effectiveness in promoting wider investment in low-carbon development

The UK has used its position as a major donor to multilateral climate funds and multi-donor initiatives to influence their investment criteria and management processes. It regularly reviews the performance of its investments, which informs its positions on governing boards and investment committees. Key stakeholders were in agreement that it backs its financial support with good quality technical inputs. Across our case studies, we saw examples of successful influence in a range of areas, including raising project quality, strengthening results orientation, improving engagement with the private sector and strengthening institutional capacity.

We reviewed a sample of nine BEIS and DFID programmes with objectives around supporting the mobilisation of private finance. We found a good range of achievements in the following areas:

- Capacity building, including helping partner countries to introduce policies and regulations that support low-carbon investment and building the capacity of local financial institutions to identify and make successful investments. For example, the UK worked with the Energy Regulatory Authority in Uganda to enable investors in small-scale renewable energy to sell power back into the grid at tariffs designed to encourage new investment.

- Demonstrating the technical and commercial viability of new technologies and business models, to encourage replication by others. For example, UK investment supported an innovative pay-as-you-go scheme for off-grid power in rural Nigeria.

- Mobilising private investment, including by providing capital to local financial institutions in many countries to invest in low-carbon initiatives and encouraging other international investors to do likewise.

Over the past seven years, UK International Climate Finance has helped to mobilise £3.3 billion in new public investments and a further £910 million in private finance. There is emerging evidence that UK investments are contributing to transformational change – particularly by building the willingness and capacity of financial markets to take on low-carbon investments.

We are concerned, however, by feedback from a range of stakeholders that there has been a falling away in the frequency and quality of external communications around UK International Climate Finance. The UK is not providing a clear and developed public narrative on the ambition or the benefits of UK International Climate Finance. This is hindering broader stakeholder engagement (for example with the City of London) and public accountability, and may also undermine the UK’s influencing and demonstration objectives.

We award UK International Climate Finance a green-amber score for effectiveness in promoting low-carbon development. The UK is delivering a good pattern of results on influencing international climate finance and supporting the mobilisation of private investment for low-carbon development. Lack of a clear public narrative for International Climate Finance, however, may hinder broader engagement and uptake that could further its effectiveness.

Learning across UK International Climate Finance

The UK has been a consistent champion of results measurement in international climate finance, encouraging its multilateral partners to develop results frameworks and strengthen their monitoring and evaluation processes. It has used its position on governing boards to ensure that investments have a strong results focus and it has contributed to a range of joint learning initiatives on the effective use of climate finance. Key stakeholders told us that the UK is seen as a thought leader on the challenging area of defining and measuring transformational change, where it has supported learning partnerships between multilateral climate change funds and other actors with a view to deriving the best impact from limited public climate finance.

All UK International Climate Finance programmes report annually, as appropriate, against a set of shared key performance indicators (KPIs). This enables the production of aggregate results in a number of areas, such as the volume of emissions that have been reduced or avoided and the level of other finance mobilised. However the KPIs capture only a subset of the portfolio’s overall achievement. The emphasis so far has been on establishing a credible reporting mechanism. We found little evidence that the data has been used for portfolio management and learning.

All programmes include learning and evidence-collection components in their annual and project completion reviews. Our review found that some learning takes place across programmes, but annual reviews are mostly focused on KPIs and reporting against the logframe. There is no systematic process for capturing lessons from individual programmes and disseminating them across the portfolio.

UK International Climate Finance has invested in a central monitoring, evaluation and learning contract, known as Compass. The contract was paused and re-scoped in 2017 and now includes portfolio-level evaluations that are expected to make a good contribution to learning. However, the re-scoping process has resulted in significant delays, with the result that most of the learning will only become available in the final year of the four-year contract.

We award a green-amber score for learning. This is in recognition of the substantial investment in results measurement and knowledge generation, and the UK’s influencing of multilateral partners to strengthen results measurement. There are, however, important issues still to be resolved around how learning is used to inform portfolio and programme management.

Recommendations

We offer the following recommendations to support the continuing development of UK International Climate Finance.

Recommendation 1

UK International Climate Finance should refresh its strategy, including a clear approach to promoting low-carbon development and to integrating low-carbon development principles across the UK aid programme.

Recommendation 2

DFID should adopt a more structured and deliberate approach to integrating low-carbon development across its programming.

Recommendation 3

UK International Climate Finance should present a clear public narrative about the ambition and value of the UK’s climate investment to support its demonstration and influencing objectives, as well as to improve visibility and public accountability.

Introduction

The challenge posed by climate change is urgent. Since the 1950s, there have been unprecedented changes in the global climate. Concentrations of greenhouse gases have increased, the atmosphere and oceans have warmed, the volume of snow and ice has diminished and sea levels have risen. Each of the last three decades has been warmer than any since 1850. A 2018 report by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change warned that we are rapidly approaching the point where climate change will present a serious and potentially irreversible threat to human societies and the planet.

As one of 184 signatories to the Paris Agreement under the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), the UK has committed to taking action to stabilise greenhouse gases at a level that will keep global temperature rise well below 2°C above pre-industrial levels and to pursue efforts to limit the increase to 1.5°C.

Keeping global warming below that threshold will require rapid, far-reaching and unprecedented changes in all countries. It will require deep cuts in greenhouse gas emissions from all sectors, including through new technologies and business practices, and behavioural changes across society. Most of the projected growth in greenhouse gas emissions is expected to come from rapidly industrialising developing countries such as China and India. Minimising future emissions in developing countries is therefore central to tackling the global climate challenge.

Under the UNFCCC, developed countries have committed to mobilising at least $100 billion per year for climate action in developing countries from public and private sources by 2020. This is to help developing countries to adapt to the impact of climate change – such as changing rainfall patterns and the increasing incidence of severe weather – and to support mitigation action, to reduce their own emissions.

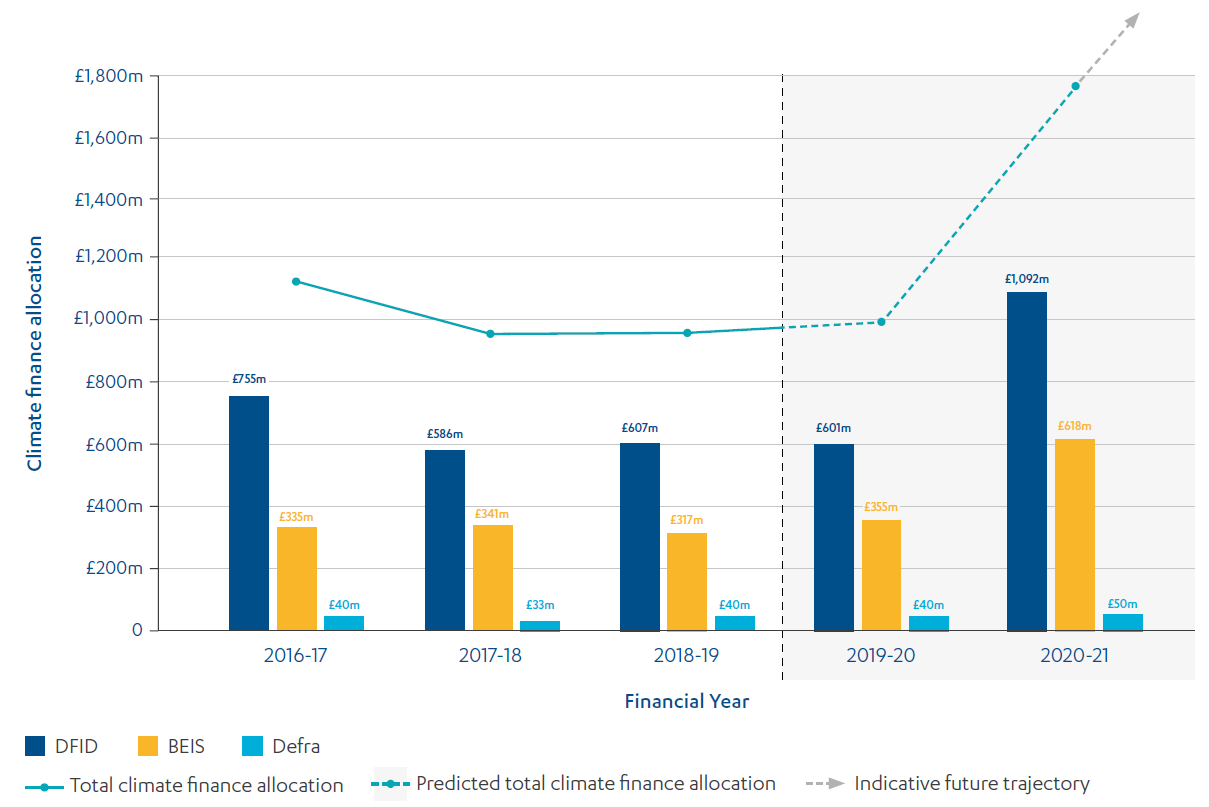

The UK has committed to providing at least £5.8 billion from the aid budget in climate finance for developing countries between 2016-17 and 2020-21 (see Figure 2). The UK supports both adaptation (to deal with the impact of climate change) and mitigation (to reduce the sources or enhance the sinks of greenhouse gases) in roughly equal proportion. Projects that reduce deforestation contribute towards both mitigation and adaptation: the UK, Germany and Norway have together committed $5 billion to forestry projects. The funds to support climate action in developing countries come from the budgets of the Department for International Development (DFID), the Department of Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy (BEIS) and the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (Defra). The portfolio of expenditure is known collectively as UK International Climate Finance.

This review assesses the contribution of UK International Climate Finance to promoting low-carbon development in developing countries. This part of the portfolio supports developing countries to shift to a development pathway that minimises emissions while still meeting their developmental goals. In helping to mitigate the future impacts of climate change on the world’s poor, low-carbon development is also central to supporting and maintaining reductions in global poverty and achieving the Sustainable Development Goals (see Box 1).

The cost of shifting to low-carbon development across the developing world is far greater than could ever be met through official development assistance alone. UK International Climate Finance is therefore intended to be catalytic in effect, unlocking other sources of finance – especially from the private sector – by demonstrating that low-carbon development solutions are both technically and economically viable.

Box 1: Low-carbon development and the Sustainable Development Goals

The Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), also known as the Global Goals, are a universal call to action to end poverty, protect the planet and ensure all people enjoy prosperity and peace. Goal 13 specifically addresses climate change:

![]()

Goal 13: Take urgent action to combat climate change and its impacts – including building resilience and capacity to adapt, integrating climate change measures into national development strategies and promoting global mechanisms for climate action under the UNFCCC.

Climate change action and low-carbon development are also embedded in other goals:

![]()

Goal 7: Affordable and Clean Energy – More use of renewables in the pursuit of universal

energy access.

![]()

Goal 9: Industry, Innovation and Infrastructure – A sustainable approach to global infrastructure development, including avoiding infrastructure investments that lock countries into high-emission pathways.

![]()

Goal 11: Sustainable Cities and Communities – Ensuring climate change mitigation and adaption in urban development.

![]()

Goal 14: Life Below Water – Conserving and making sustainable use of the oceans, including preventing ocean acidification by reducing greenhouse gases.

![]()

Goal 15: Life on Land – Sustainable management of forests, which is key to global plans to reduce emissions.

The growing impact of climate change threatens to impede our ability to achieve – or even to cause a reversal of progress on – other SDGs, including on poverty, hunger, health, clean water and responsible consumption and production.

The last time ICAI undertook a review of UK climate finance for developing countries was in 2014. At that time, UK aid for climate action was channelled through a cross-government fund, the UK’s International Climate Fund. The review covered all three founding objectives of this fund: climate change adaptation (helping developing countries deal with the impact of climate change), low-carbon development (mitigation of future climate change) and forestry (sustainable management of forest resources). In this review, we have decided to focus on low-carbon development, excluding forestry, to allow for a deeper exploration of the UK’s contribution to mobilising the global finance needed to help developing countries achieve a low-emission development trajectory.

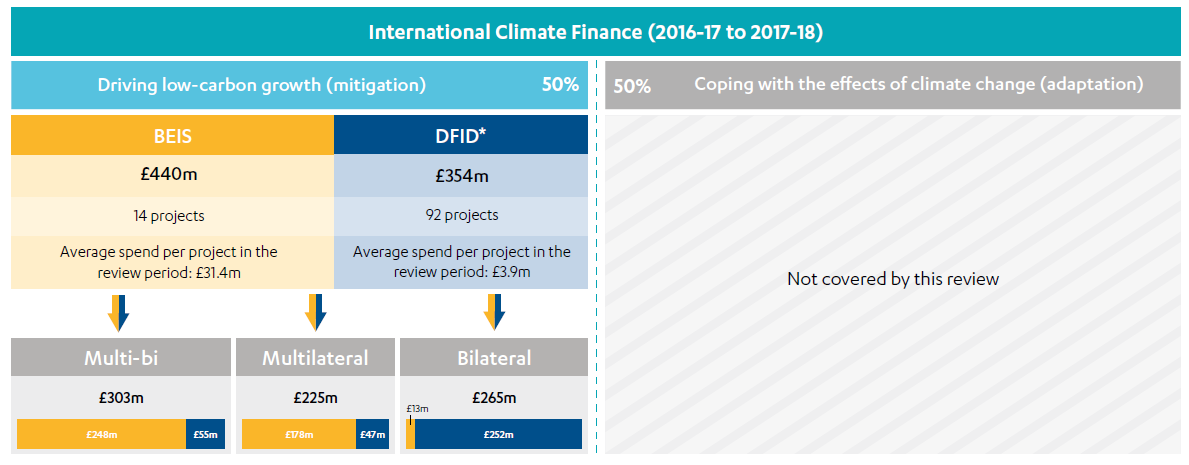

Excluding forestry, just under £800 million has been spent on low-carbon development from 2016-17 to 2017-18, shared between BEIS (approximately 55%) and DFID (45%). The funds are used for bilateral climate projects and contributions to multilateral climate funds and international initiatives (see Figure 4).

Given the scale and maturity of the UK’s international climate investments, we opted to conduct a performance review (see Box 2). We cover the period from 2016-17, the start of the current phase of UK International Climate Finance, to 2017-18. We assess whether the portfolio demonstrates a convincing approach to promoting low-carbon development, and whether the responsible departments are effective in their efforts to mobilise and improve climate spending by other contributors, including the private sector. Our review questions are set out in Table 1.

Table 1: Our review questions

| Review criteria and questions | Sub-questions |

|---|---|

| 1. Relevance: Does the UK’s approach to low-carbon development reflect the needs of developing countries and its international commitments to climate finance? | • How credible and coherent is the UK’s approach to helping developing countries adopt low-carbon development? • How credible and coherent is the UK’s approach to strengthening the international climate finance architecture to support low-carbon development? |

| 2. Effectiveness: How effective is UK International Climate Finance at promoting investment in low-carbon development? | • How effective is UK International Climate Finance in its efforts to demonstrate that low-carbon development is feasible and desirable? • How effective is the UK in its efforts to improve the international climate finance architecture? |

| 3. Learning: How well do UK investments in low-carbon development promote and reflect learning and evidence? | • How well has the UK contributed to generating and sharing research and evidence on low-carbon development? • How adaptive and/or innovative is UK International Climate Finance in response to results and learning? |

Box 2: What is an ICAI performance review?

ICAI performance reviews take a rigorous look at the efficiency and effectiveness of UK aid delivery, with a strong focus on accountability. They also examine core business processes and explore whether systems, capacities and practices are robust enough to deliver effective assistance with good value for money.

Other types of ICAI reviews include impact reviews, which examine results claims made for UK aid to assess their credibility and their significance for the intended beneficiaries, learning reviews, which explore how knowledge is generated on new or recent challenges for the UK aid programme and translated into credible programming, and rapid reviews, which are short, real-time reviews examining an emerging issue or area of UK aid spending.

Methodology

Our methodology was designed to assess how well the portfolio and related influencing activities by the UK government are unlocking climate finance flows for low-carbon development. We therefore focused on the UK’s interactions with the international climate finance architecture and on its use of programmes to support the mobilisation of other financial flows. We did not carry out any field assessments of the implementation of individual low-carbon development projects.

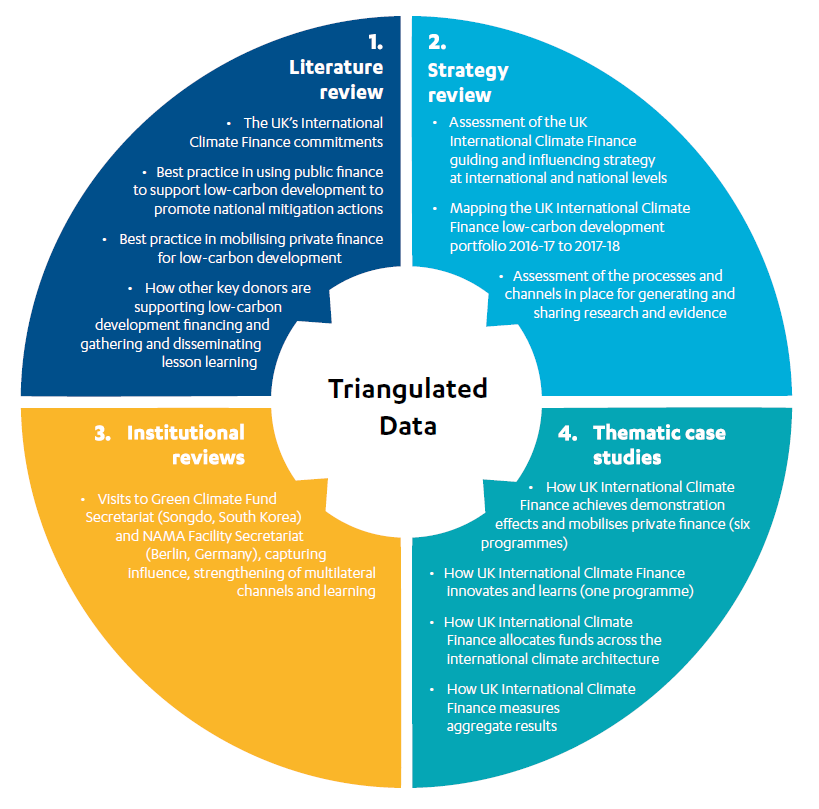

Our methodology included four components (see Figure 1, see also Box 3 for limitations):

- Literature review: We reviewed the academic and ‘grey’ literature to identify emerging good practices in the provision of climate finance for low-carbon development and to collect views on how to strengthen the international climate finance architecture.

- Strategy review: We reviewed the policies, strategies and guidance that govern UK International Climate Finance and conducted interviews with key stakeholders, both inside the UK government and externally, to explore whether the UK has a credible approach to promoting low-carbon development.

- Institutional reviews: To assess how well the UK uses its climate finance and related influence to shape the international climate architecture, we prepared case studies of its relationship with two strategically important institutions with a strong low-carbon development focus: the Green Climate Fund and the NAMA Facility. The UK has contributed a total of £223 million in funding for low-carbon development to these institutions during our review period. We visited their headquarters in South Korea and Germany, reviewed UK government and external documents and interviewed stakeholders, including international officials and other funders.

- Thematic case studies: We undertook thematic case studies of four aspects of UK International Climate Finance work:

- How the UK allocates funds across the international climate finance architecture – the complex network of multilateral funds and initiatives through which the bulk of global climate finance is spent.

- How UK International Climate Finance achieves demonstration effects and mobilises private finance. This included desk reviews of a sample of nine programmes with objectives around supporting the mobilisation of private finance.

- How the responsible departments measure results at the portfolio level.

- Innovation and learning in UK International Climate Finance.

Figure 1: Components of the methodology

Box 3: Limitations to the methodology

In this review, we have attempted to assess the contribution of UK climate programmes to mobilising and shaping other sources of climate finance. This is inherently difficult to measure and attribute to UK funding, much of which is spent via multilateral funds and multi-donor institutions with complex funding sources and delivery channels.

For the mobilisation of public finance through the international climate finance architecture, we explored evidence of whether the UK had been effective in its objectives around strengthening the architecture as a whole and the operations of individual multilateral climate funds and initiatives. Regarding the mobilisation of private finance, we examined a sample of bilateral and multi-donor projects with mobilisation objectives. However, these were desk reviews, drawing mainly on results data generated by the programmes themselves, triangulated to the extent possible through key informant interviews. Our focus is on results at the portfolio level; we have had limited scope to explore results within particular sectors or thematic areas.

Background

What is low-carbon development?

For the UK and other international climate funders, promoting low-carbon development means helping developing countries to shift to a development trajectory that minimises greenhouse gas emissions while still bringing about economic growth and poverty reduction.12 This might include, for example, promoting renewable energy infrastructure while at the same time moving towards universal access to energy, or introducing sustainable land management in agriculture that also helps to promote better rural livelihoods.

Promoting low-carbon development in developing countries is essential to global progress on mitigating climate change. The most rapid economic growth and industrial development in the 21st century is likely to occur in developing countries, especially large middle-income countries. Climate finance is used to help developing countries move their economies onto a lower-carbon trajectory – for example by avoiding new investments in carbon-intensive technologies such as coal-powered energy generation in favour of lower-carbon solutions. Low-carbon development can also be an effective way of promoting sustainable economic growth and pro-poor development, even though the upfront investment costs of adopting new technologies may be higher.

The objective of promoting low-carbon development cuts right across the development process, with implications for every sector (see, for example, Box 4 for the energy sector). It is up to each country to determine its ambition, strategies and priorities for climate change action. These are then submitted to the UNFCCC in the form of nationally determined contributions (NDCs). NDCs typically address areas such as:

- moving to clean energy, including large-scale renewable energy connected to electricity grids, off-grid power and storage solutions

- green buildings

- climate-smart urban transport and logistics

- climate-smart agriculture

- climate-smart urban water infrastructure

- climate-smart urban waste management.

NDCs should be updated every five years, rising in ambition over time.

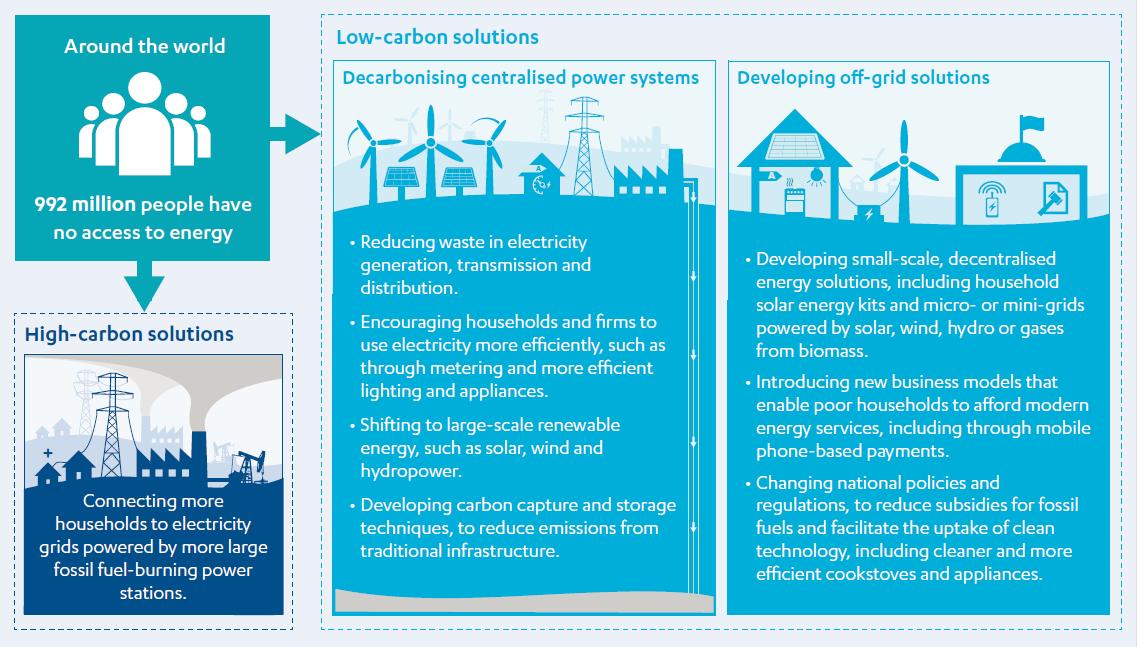

Box 4: Promoting low-carbon development in the energy sector

Around two-thirds of the world’s greenhouse gas emissions are from the energy sector and much of the UK’s international climate finance goes into the promotion of lower-carbon energy solutions. Around the world, 992 million people have no access to electricity, while 2.7 billion lack access to clean energy for cooking. Expanding access to affordable, reliable and sustainable energy is one of the Sustainable Development Goals and fundamental to achieving many of the other Goals, including poverty reduction and eliminating hunger (boosting food production), education (lighting for schools and home study), health (refrigerating vaccines) and gender equality (providing access to renewable energy reduces the time that women and girls spend collecting firewood).

The conventional approach to expanding energy access – connecting more households to electricity grids powered by more large fossil fuel-burning power stations – risks locking developing countries into unnecessarily high greenhouse gas emissions for decades to come. The typical coal-fired power station being built today has a 40- to 50-year lifespan.

For the energy sector, low-carbon development means both addressing the vast energy deficit in developing countries and meeting the need for more energy for economic growth through renewable energy solutions, which are often now the lowest-cost solutions. This involves many different elements, including:

Present global investment levels in renewable energy are below the estimated investment needs to address the deficit and achieve climate change goals. While international donors can and do provide direct funding for clean energy solutions, their aim is to demonstrate in partner countries, to private companies and financial institutions, that clean energy is both technically and commercially viable. The intention is that this will mobilise investment on a scale that can provide affordable energy for the poor while preventing the need for further large-scale investment in high-carbon infrastructure.

What is climate finance?

Although all countries must take action to tackle harmful climate change, their respective responsibility for past emissions of greenhouse gases and their capability for action are not equal. It is a settled principle of international climate action that developed countries, which have been responsible for the bulk of emissions to date, have an obligation to help finance climate action in developing countries. This is the role of international climate finance.

In Copenhagen in 2009, developed countries jointly committed to providing $100 billion annually by 2020, from both public and private sources, for climate action in developing countries. This commitment applies until 2025, before which a new higher target will be agreed. There is no agreed formula, however, as to how much funding each country should provide, or how much should come from public rather than private sources (in other words from aid funds), and it remains up to each national government to establish their contribution.

While there is no single agreed definition of climate finance, the parties to the UNFCCC are said to be converging towards the following definition: “Climate finance aims at reducing emissions, and enhancing sinks, of [greenhouse gases] and aims at reducing vulnerability, and maintaining and increasing the resilience, of human and ecological systems to negative climate change impacts.

2018 Biennial Assessment and Overview of Climate Finance Flows Report, UNFCCC, 2018

Developing countries have different initial conditions, needs and priorities for climate finance. Low-income countries often lack the enabling conditions for low-carbon investment, such as supportive government policies and legal frameworks. A key role for climate finance is helping to put in place those enabling conditions, usually through technical assistance and grant finance. Where more developed capital markets exist, including in many middle-income countries, climate finance is used to create the conditions for investment at scale, often in areas where there is a limited track record of successful private investment.

Most developing countries are not yet in a position to predict the costs involved in shifting to low-carbon development. However, their investment needs are likely to far exceed the international climate finance available from the aid budgets of developed countries. The role of aid is therefore to help mobilise funding at scale from other sources, including from the private sector, rather than to fund investments directly. This includes demonstrating the technical and commercial viability of clean technologies and approaches and helping clear away obstacles to private investment – such as unfavourable national policies and regulations, a lack of investment-ready projects, the tendency of commercial financiers to overestimate the risks involved and the often high costs of doing business in developing countries. Grants or low-interest loans from donors can be blended with private finance in ways that reduce the risks for private investors.

Estimates of the amount of climate finance needed to promote low-carbon development in developing countries are based on global models rather than country-specific estimates, and are therefore approximate. In 2017, the World Bank estimated that the 21 most rapidly developing countries would collectively require $23 trillion in climate investments between 2016 and 2030.

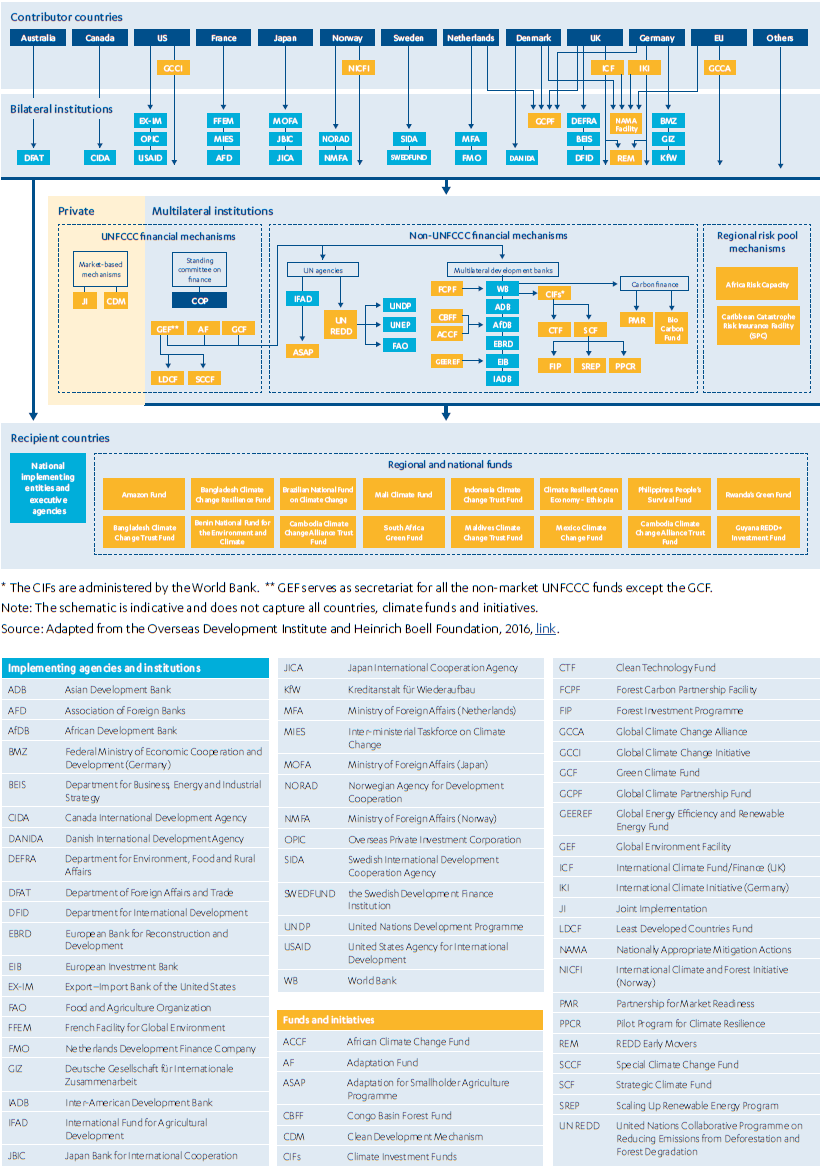

A complex institutional structure has emerged to channel climate finance from donors to developing countries. We refer to this as the climate finance architecture (see Annex 3). It includes:

- multilateral climate funds (see Box 5) and other intermediaries

- bilateral funds and multi-donor programmes

- lending by multilateral development banks from their regular resources

- funds managed by the private sector and private finance, which in some cases are mobilised by public finance.

Box 5: Multilateral climate funds

Multilateral climate funds pool contributor finance and spend around specific climate objectives, operating through multilateral, regional or national organisations. A complex architecture of multilateral funds has been built up over the years to channel climate finance to developing countries. Some were established to support implementation of the objectives of the UNFCCC, while others have been established outside its auspices. The multilateral climate funds referred to in this review are:

- Global Environment Facility: Established in 1991 in preparation for the 1992 Rio Summit to tackle the most pressing environmental challenges around the world, including in developing countries. Part of the UNFCCC framework, it has attracted nearly $18 billion in grants and mobilised another $93 billion in co-financing for over 4,500 projects since its inception. Its activities include the protection of sensitive land and marine ecosystems, initiatives to promote sustainable forestry and land use, emissions reduction and adaptation to climate change.

- Clean Technology Fund: This $5.4 billion fund, one of the Climate Investment Funds, established in 2008 outside the UNFCCC framework, provides large-scale funding for the demonstration, deployment and transfer of low-carbon technologies with the potential for significant long-term emissions savings.

- Scaling Up Renewable Energy Programme: This $720 million programme under the Climate Investment Funds, established in 2008 outside the UNFCCC framework, was designed to demonstrate the economic, social and environmental viability of low-carbon development pathways in the energy sector in low-income countries.

- Green Climate Fund: Established in 2010 by the parties to the UNFCCC to help developing countries respond to the challenges of climate change, including both adaptation and mitigation. It has a specific mandate to assist developing countries that are particularly vulnerable to climate change, including Least Developed Countries (LDCs), Small Island Developing States (SIDS) and African states. Before the adoption of the 2015 Paris Agreement, the Green Climate Fund was given a central role in supporting implementation of the agreement and its objective of keeping global temperature rise below 2°C above pre-industrial levels. It began mobilising resources in 2014 when it gathered $10.3 billion in pledges and is increasingly approving funding for projects and programmes as fund guidance and policies are put in place.

In 2017, multilateral climate funds collectively approved close to $2 billion for 152 projects in 70 countries. Their finance is highly concessional, provided in the form of grants, low-interest loans and more recently guarantees and equity. Channelling climate finance through multilateral funds balances out the preferences of individual donor countries, allows for fairer and more transparent allocation and gives developing countries greater ownership and control of the resulting climate action. The diversity of instruments, each with different objectives, allocation criteria and ways of working, also provides developing countries with more options for accessing funding.

However, the climate finance architecture is undoubtedly complex. New funds have been created at particular points during international climate negotiations without old initiatives being retired. This has led to overlapping mandates and activities.

The UK’s low-carbon development portfolio

UK International Climate Finance is the term for the UK’s contribution towards the $100 billion a year global climate finance commitment to helping developing countries respond to the challenges and opportunities of climate change. It consists of the UK’s contributions to multilateral climate funds and multi-donor programmes, together with bilateral programmes to support adaptation and mitigation.

The government is committed to spending at least £5.8 billion between 2016 and 2021 on climate finance – a 50% increase over the previous five-year period – as its contribution to the global target of mobilising at least $100 billion a year by 2020, from both public and private sources. The scale of the commitment reflects the UK’s goal of being a global leader on climate finance33 and is intended to increase the UK’s influence within the international climate architecture. The funding is split equally between climate change adaptation and mitigation and comes from the budgets of DFID, BEIS and Defra (see Figure 2).

Figure 2: UK International Climate Finance allocation by department, 2016-17 to 2020-21

The increasing levels of spending on climate finance reflect the UK’s commitment to playing its part in the global climate finance commitment for developed countries to mobilise at least $100 billion a year by 2020 for developing countries, and also reflects the global commitment to set a higher goal before 2025.

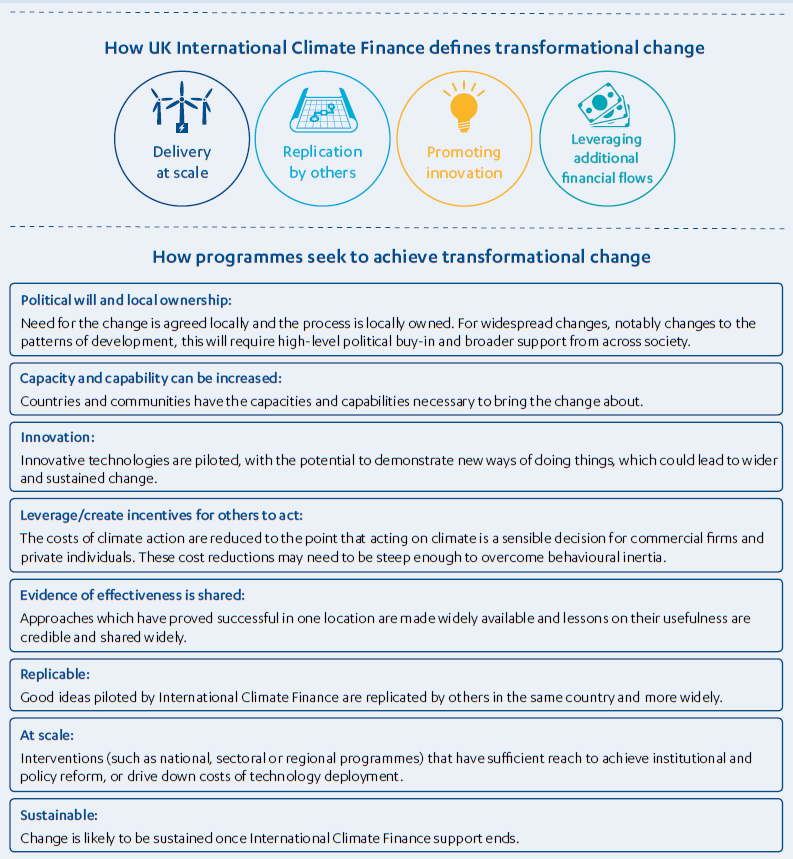

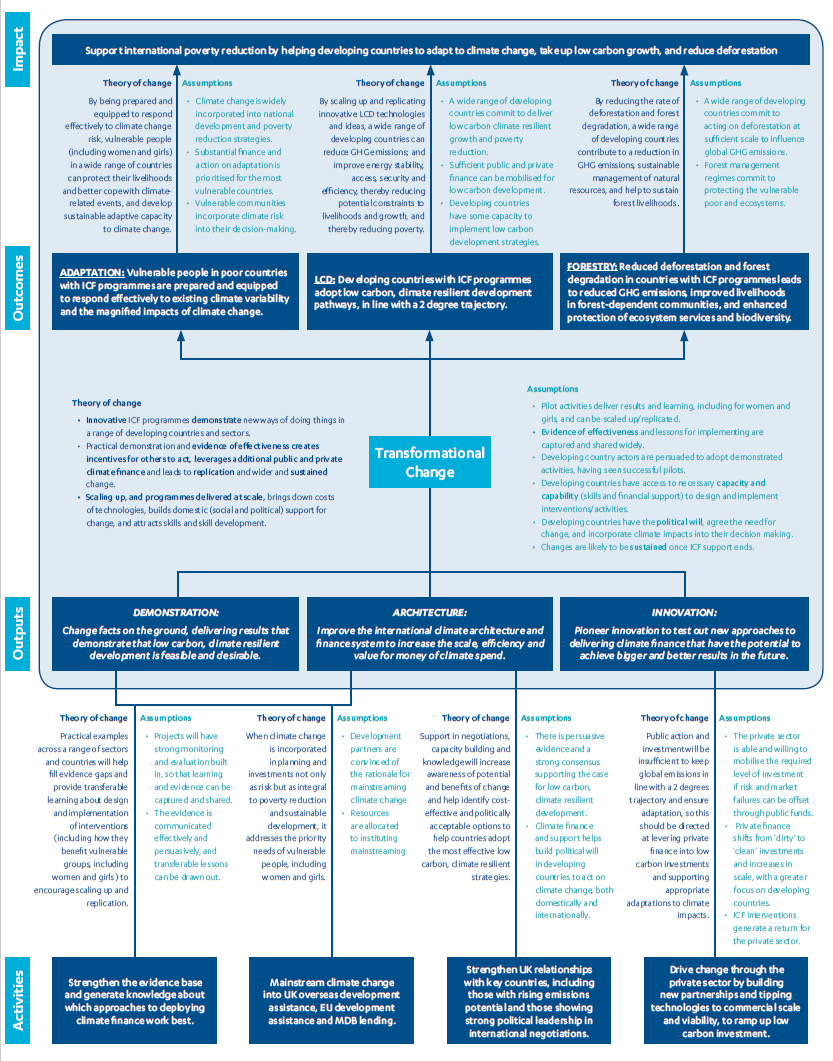

According to its theory of change (reproduced in Annex 2), UK International Climate Finance delivers results by:

- Demonstration: Changing national policies and commercial markets through projects that demonstrate that low-carbon, climate-resilient development is feasible and desirable.

- Architecture: Improving the international climate architecture and finance system to increase the scale, efficiency and value for money of international climate finance.

- Innovation: Pioneering new approaches to delivering climate finance that have the potential to achieve bigger and better results in the future.

In the period from 2011 to 2016, the UK’s climate finance was disbursed through a cross-government fund, the International Climate Fund. During this period, the three spending departments worked under joint ministerial oversight with a joint board and a secretariat chaired by DFID. Since April 2016, the responsibility for managing spending targets and programmes has been devolved to the three departments, although the portfolio continues to be branded internationally as ‘UK International Climate Finance’. It retains a cross-government strategy board, which approves the strategy and oversees coherence with UK government policy, and a management board, which monitors expenditure, delivery and risk. There is no official public explanation for the change in central oversight and management arrangements. We were informed that this was to streamline approval processes and to allow the board to focus more on strategy, although some stakeholders have informed us that it reflected a preference for a lower public profile within the UK for climate finance. Figure 3 shows how UK climate finance has evolved over time.

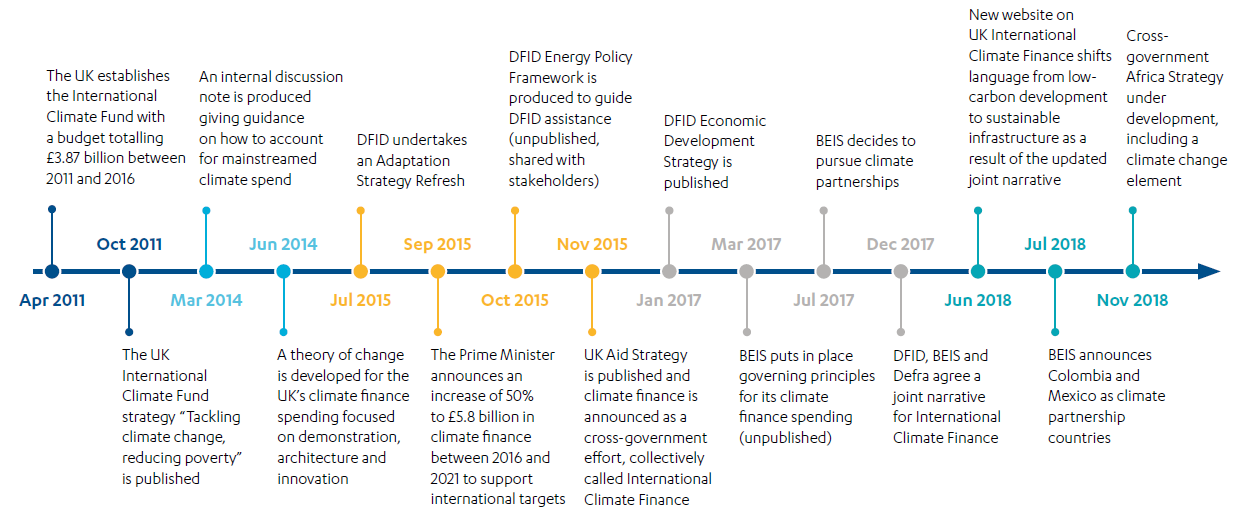

Figure 3: A timeline of the provision of international climate finance by the UK

We calculate that the UK spent just under £800 million on low-carbon development (excluding forestry) in the two years 2016-17 and 2017-18 (see Figure 4). BEIS spent 55% of this, or £440 million. In this review period, the BEIS low-carbon development portfolio consists of 14 programmes, including two contributions to multilateral climate funds (the Clean Technology Fund and the Green Climate Fund) and 12 bilateral programmes. Of the bilateral programmes, all but three are multi-bi programmes (that is, programmes delivered by a multilateral delivery partner but where BEIS has a role in specifying the purpose of the funding and in some cases the recipient). These are managed by a dedicated climate finance team of approximately 46 people in London, as well as staff in some UK embassies. The BEIS low-carbon development portfolio is focused on helping developing countries with large and growing industrial sectors to take large-scale action to reduce emissions.

DFID has progressively moved from a portfolio of dedicated climate programmes to mainstreaming climate action across its portfolio (it calls this approach ‘integration’). Where low-carbon development is integrated into DFID programmes, the amount attributed to UK International Climate Finance only reflects the share of the programme budget relevant to this objective and not always the full project spending. While DFID still has a number of dedicated climate programmes, including three multilateral contributions and some substantial programmes in the area of renewable energy (that are 100% funded by UK International Climate Finance), for many programmes UK International Climate Finance often comprises only a minor share of the expenditure. (For example, a major health programme might include a small component equipping rural health clinics with solar energy.) DFID’s £354 million expenditure on low-carbon development (excluding forestry) over the past two years is therefore spread across 92 DFID programmes in multiple sectors. There is a dedicated eight-member international team within DFID’s Climate and Environment Department, working primarily on DFID’s engagement with the international climate finance architecture and key multilaterals such as the World Bank and regional development banks. Other teams in the Climate and Environment Department work on other aspects of climate policy. The responsibility for integrating climate finance across the DFID portfolio is shared across the regional departments and country offices.

Figure 4: The International Climate Finance portfolio, 2016-17 to 2017-18†

†Excludes funding spent on forestry.

*DFID’s spending on low-carbon development is integrated across its programmes. The figures given here reflect only the share of programme budgets that DFID has identified as pertaining to low-carbon development.

Our sample includes six BEIS and three DFID programmes with objectives related to demonstrating the viability of low-carbon initiatives and helping to mobilise private finance. This represents all the BEIS programmes with demonstration and mobilisation objectives, but only a selection of those managed by DFID. These are summarised in Table 2.

Table 2: Our sample of climate programmes designed to mobilise private finance for low-carbon development

| Programme name | Department | Timing | Expenditure before 2016-17 | Expenditure during review period (2016-17 to 2017-18) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BEIS | Renewable Energy Performance Platform | 2015-2020 | £2.8m | £45.2m |

| Supports early-stage development of small- and medium-scale renewable energy projects in sub-Saharan Africa, through technical assistance and results-based financing. | ||||

| BEIS | Sustainable Infrastructure Programme Latin America | 2017-2022 | £52m | |

| Aims to accelerate sustainable infrastructure development in Latin America by catalysing private sector investment for the implementation of NDCs. | ||||

| BEIS | UK Climate Investments | 2015-2019 | £3.2m | £11.8m |

| A joint venture with Macquarie Infrastructure and Real Assets (formerly the UK Green Investment Bank) which makes commercial equity investments into renewable and energy efficiency projects in India and subSaharan Africa. | ||||

| BEIS | Global Climate Partnership Fund | 2016-2024 | £30m | £6m |

| A public-private partnership that lends mainly to local financial institutions for on-lending to low-carbon projects, but can also lend directly. BEIS has also committed funding to run the fund’s Technical Assistance Facility. | ||||

| BEIS* | Climate Public Private Partnership (CP3) - Asia Climate Partners | 2014-2026 | £5m | £4.7m |

| A private equity fund, investing via financial institutions and directly into projects promoting clean energy, resource efficiency and environmental management in Asia. | ||||

| BEIS | Global Innovation Lab/CMCI (The Lab) | 2014-2021 | £0.3m | £0.4m |

| The Lab is a forum for public and private stakeholders to come together and generate innovative proposals to attract private investments in energy efficiency, renewable energy and sustainable transport. | ||||

| DFID | On- and Off-Grid Small-Scale Renewable Energy in Uganda (GET FiT) | 2013-2024 | £11.2m | £6.5m |

| The programme aims to mobilise private investment into renewable energy generation capacity in Uganda by overcoming constraints on private sector investment. It supports the development and completion of small-scale private sector renewable energy projects that feed into the national grid. | ||||

| DFID | Renewable Energy and Adaptation Climate Technologies | 2010-2021 | £4m | £2.1m |

| Supports for-profit companies in their early stages, sharing the risks as they start out and develop into sustainable businesses. It also provides demand-driven technical assistance to priority countries in Africa. | ||||

| DFID | Climate Public Private Partnership (CP3) Seed Capital Assistance Facility | 2014-2022 | £4m | £4.6m |

| Provides support to private equity and venture capital funds and project development companies to help them source deals. It also supports first-time fund managers, to increase the number of actors in early-stage climate investment. | ||||

*While CP3 and GET FiT Uganda are ongoing joint programmes between DFID and BEIS, the actual expenditure figures in the period of our review have been attributed to BEIS and DFID respectively.

Findings

Does the UK’s approach to low-carbon development reflect the needs of developing countries and its international commitments to climate finance?

This section presents our findings on the relevance of the objectives and approach of UK International Climate Finance to low-carbon development. It first considers the UK’s approach to strengthening the international climate finance architecture for low-carbon development, before turning to its overall strategy and approach for helping developing countries adopt low-carbon pathways.

The UK uses its multilateral climate finance strategically to strengthen the climate finance architecture

The global political context for climate action is complex. Developed countries vary in their willingness to contribute to the international climate finance target and there are continuing international debates on how to deploy this finance to best effect. The international climate finance architecture continues to evolve rapidly as global financial flows are scaled up.

The UK has made a strong commitment to joint international action on climate change. In our review period, it has directed two thirds of its climate finance for low-carbon development through multilateral and multi-donor channels – a higher proportion than other large contributors who channel greater shares through bilateral channels. This both reflects and supports the UK’s goal of being a global leader on international climate finance. It places the UK in a stronger position in international climate negotiations to advocate for more financial support from developed countries for climate action. It also enables the UK to be an influential voice within the governing mechanisms of multilateral climate funds, where the processes for allocating funds are agreed.

There are also aid-effectiveness arguments in favour of using multilateral channels. Globally, it is efficient for contributions from multiple countries to be combined into multilateral funds with common objectives and processes, rather than spent through parallel bilateral projects. Multilateral development institutions also specialise in managing large-scale development loans, which are the predominant form of climate finance for middle-income countries. Unlike some bilateral contributors, such as Germany and Japan, the UK does not have a large vehicle for providing development loans although the development finance institution CDC Group plc (CDC) is an increasingly important channel for climate finance).

We also find that the UK has made strategic choices about which multilateral initiatives to support, in order to ensure coherence, continuity and coverage in the climate finance architecture.

- The UK is the fourth-largest contributor to the Global Environment Facility’s focal area on climate change. The Global Environment Facility is the oldest multilateral climate fund and part of the UNFCCC Financial Mechanism (see Box 5 above). It was designed to work through existing international institutions, such as the World Bank, the UN Environment Programme (UNEP) and the UN Development Programme (UNDP), and provides relatively small-scale project finance across 135 eligible countries. The UK’s pledges to this fund demonstrate its long-standing commitment to helping developing countries mitigate and adapt to climate change, but also to global coverage, allowing the climate finance architecture to support all developing countries. However, the Global Environment Facility does not have the same scope as newer funds to work in partnership with developing country entities and institutions or to manage large-scale financial support.

- The UK is the third-largest contributor to the Green Climate Fund based on the original pledges to the fund’s initial resource mobilisation. This is the newest addition to the Financial Mechanism of the UNFCCC, and enjoys strong support from both developed and developing countries. It is expected to become the largest multilateral climate fund over time, thereby helping to rationalise the climate finance architecture. The UK expects it to lead a shift towards supporting country-driven approaches to climate-resilient and low-carbon development. In January 2019, the UK became co-chair of the Green Climate Fund board and will need to work with board members and fund stakeholders towards a successful first replenishment of the fund – the process by which the international community is invited to scale up its investment capital – launched in late 2018 and expected to be completed by October 2019. The UK regards the continuing success of the fund as critical to progressing the climate change negotiations under the UNFCCC process.

- The UK is also a major contributor to a number of other more mature climate funds that it regards as strategic. These include the Clean Technology Fund and the Scaling Up Renewable Energy Program, which are designed to build an understanding of how climate finance can be deployed at scale to bring about transformation in clean technology and energy access in selected developing countries. These funds may be phased out as the Green Climate Fund reaches its intended scale, but at present they continue to operate alongside the Green Climate Fund. The UK’s contributions to these funds ensure continuity of support in this area. The two funds channel their expenditure through the World Bank and regional development banks. The UK contribution therefore also provides an opportunity to influence how the multilateral development banks spend their climate finance.

The UK has also taken steps to fill gaps in the climate finance architecture. For example, it worked with Germany to establish the NAMA Facility. Under the UNFCCC, developing countries were asked to propose specific mitigation initiatives, known as Nationally Appropriate Mitigation Actions (or NAMAs). None of the existing multilateral mechanisms were in a position to fund these. The UK considered it important to do so, to promote developing country ownership and leadership of low-carbon development. The NAMA Facility was therefore created, both as a financing mechanism and as a political signal that developed countries were willing to support county-led initiatives.

Beyond exercising its influence as a contributor to climate funds, we also saw evidence of effective influencing of other international actors on low-carbon development – especially the multilateral development banks. This includes advocacy for scaling up low-carbon investments and phasing out high-carbon ones. It has used the Cartagena Dialogue (a working group of countries dedicated to promoting low-carbon development), the G20 and the G7 to build high-level support for climate action. However, we found no explicit influencing strategy at the level of UK International Climate Finance nor objectives against which to assess the UK’s approach.

UK International Climate Finance has been explicit in aligning with the needs of developing countries, but country plans remain at an early stage

Good development practice suggests that developing country ownership and leadership will be essential for effective action on low-carbon development.40 However, many developing countries remain at an early stage in articulating their national strategies and identifying priority investment needs.

We find that the UK’s international climate programmes have generally displayed a well-balanced approach to helping partner countries articulate low-carbon development objectives and then providing finance to support their implementation. A number of programmes support the development of country plans, including:

- The NDC Partnership, a coalition to enhance cooperation between countries for the implementation of their climate change ambitions and Sustainable Development Goals.

- Additional support for the secretariat of the NAMA Facility to integrate nationally determined contributions (NDCs) into the facility’s objectives (as these were introduced after the facility was designed).

Across the programmes we reviewed, there were well-designed processes in place to ensure that investments are consistent with partner governments’ stated ambitions. We found that the need for alignment was clearly addressed in the business cases of bilateral programmes, as required by DFID’s Smart Rules and guidance. In some instances, there were further requirements for delivery partners to align with country needs for low-carbon development. For example:

- The Sustainable Infrastructure Programme Latin America, a new BEIS programme delivered through the Inter-American Development Bank, is required to use partner countries’ emissions plans as a starting point to identify investments.

- The multilateral climate funds that the UK supports have screening processes in place to ensure alignment. For example, the Green Climate Fund will only approve projects that have the support of a national point of contact to ensure consistency with national climate and development plans and preferences.

The UK also provides technical assistance to improve the quality of national climate strategies. For example, UK technical assistance is helping to build capacity in local financial institutions to support low-carbon investments and to develop pipelines of investable projects, including through demonstration projects and support for project preparation.42 There is also support to national governments and other bodies to identify low-carbon development needs, draft strategies, make the required legislative and institutional changes and implement projects:

- The Renewable Energy Performance Platform accounts for £45.2 million in low-carbon development spending over the review period. It supports early-stage project development in sub-Saharan Africa by providing technical assistance and results-based finance for the development and construction of small and medium-sized renewable energy projects.

- The Global Climate Partnership Fund accounts for £6 million over the review period. The programme is a public-private partnership which provides loan finance for low-carbon development projects, both directly and through local financial institutions. BEIS had previously invested £30 million in the Global Climate Partnership Fund to this end in 2013. The funding covered by our review period has been provided by BEIS for a technical assistance facility which supports fund investors in project design and technical appraisal of potential initiatives and helps them better assess investment risks.

BEIS is in the process of developing climate partnerships with a number of countries that have high ambitions for transitioning to low-carbon development and the capacity to achieve results at scale. These will help to align the UK’s various climate initiatives (including new programmes planned under the Prosperity Fund) into a strategic framework agreed with the partner country. (DFID has country strategies for its development assistance as a whole, but not specifically for climate change or low-carbon development.) The partnerships will include:

- Agreement to deepen bilateral cooperation on climate action.

- Technical assistance through the UK Partnering for Accelerated Climate Transitions (PACT) programme to support the development and implementation of NDCs, drawing on UK skills and expertise, with particular focus on deforestation, clean energy, green finance and climate legislation and governance.

- Where appropriate, investment capital to support sustainable infrastructure.

- Colombia and Mexico have been identified as the first candidates for climate partnerships, with others in the pipeline. In Colombia and Mexico, the initial focus will be on helping the governments define their plans and policies for implementing their NDCs. According to BEIS documents, the climate partnerships are intended to raise the visibility of UK climate finance and create mutually beneficial partnerships, including by opening up opportunities in sectors where UK companies have a comparative advantage. These partnerships have the potential to support the alignment of UK climate finance with developing countries’ national priorities, but are currently too new to assess.

- In China, the UK PACT programme will focus on green finance, building the capacity of China’s financial sector to support low-carbon initiatives both domestically and internationally. China is a front-runner among developing countries in establishing a green financial system, and the programme will help unlock further financial flows in China while developing learning for global application, building on the existing UK-China relationship on green finance.

BEIS has a clear strategy for promoting low-carbon development in countries with large or rapidly growing emissions

BEIS has developed a set of unpublished ‘governing principles’ for its climate programming. These state that the programmes will focus on:

- Large-scale mitigation, particularly in countries with large or rapidly growing emissions.

- Transformational change and private finance mobilisation.

- Increasing UK visibility in relation to climate action, in line with recent government priorities, and identifying opportunities for secondary commercial benefits for the UK.

BEIS will continue to prioritise large-scale mitigation and private sector projects in countries with large or rapidly growing emissions. This complements DFID’s focus on adaptation and building climate resilience in the poorest countries.

BEIS ICF Governing Principles: Strategy and operating model for international climate finance, 2017, unpublished

BEIS programmes focus on countries with large or rapidly growing emissions, which tend to be large middle-income countries. This reflects the much greater current and projected contribution of middle-income countries to global emissions, compared with low-income countries, and the fact that emissions have global impact wherever produced. The intention is that UK climate finance be applied in a catalytic manner in these countries, to unlock much larger investments by national authorities and the private sector. Internal documents indicate that BEIS and DFID are aware that it is important to avoid using UK climate finance to substitute for investments that the country itself or the market should undertake. The policy is therefore to limit grant funding in middle-income countries to technical assistance, while providing loans via delivery partners for investment.

There is a focus on using UK resources to mobilise private finance through demonstration projects. The strategy covers different levels of market maturity, as follows:

- In countries or sectors where capital markets are relatively underdeveloped, the approach focuses on demonstrating that investments in low-carbon development can be economically advantageous to developing countries and also offer a financial return to investors. The measures can include providing support to develop bankable project concepts, building capacity in partner countries to overcome regulatory and institutional barriers, trialling new technologies or business models and influencing the multilateral development banks to be more climate-smart in their support. The main focus is on the energy sector, but BEIS also supports other sectors, such as green buildings and cities.

- In areas where financial markets are more mature, the strategy is to create conditions for scaling up private finance. This includes providing financial support to governments, developers and lenders for the design, preparation and implementation of new investment projects, to demonstrate to the market that risks are manageable and profits achievable on low-carbon investments. BEIS also supports local financial institutions, to broaden the range of financial instruments available in developing country markets, while promoting the ‘greening’ of global capital markets by working in international forums to shift incentives in favour of investment in low-carbon development.

We have seen evidence of this differentiated approach being taken forward into BEIS programming. For example, at the smaller end of the market the Global Climate Partnership Fund (£36 million; 2013-2024) helps local finance institutions, such as commercial banks, to provide loans to small- and medium-sized enterprises and households for small-scale renewable and energy efficiency projects in developing countries. The Renewable Energy Performance Platform (£48 million; 2015-2020) bundles together small- and medium-scale renewable energy projects in sub-Saharan Africa, so as to unlock capital from larger financial institutions such as multilateral banks. At the other end of the spectrum, BEIS and DFID are anchor investors in the IFC Catalyst Fund (£61.4 million UK contribution), a private equity fund-of- funds for climate-friendly investments in emerging markets that is designed to attract large-scale institutional investors such as pension funds and sovereign wealth funds.

BEIS’s objective of increasing the visibility of the UK’s climate finance and creating opportunities for secondary commercial benefits for UK firms is an increasingly common feature of the UK aid programme, which we have explored in previous reviews. According to senior stakeholders, there are concerns that delivering UK international climate finance mainly through multilateral channels has limited the visibility of UK climate finance through a lack of UK branding. The move towards country partnerships is intended to provide more opportunity to showcase UK climate finance, as well as to identify sectors where UK firms are likely to be competitive.

Overall, we find that BEIS has a well-considered strategy for its low-carbon development investments, with a clear and well-justified set of priorities and approaches. Given the UK’s position in international climate negotiations and its commitment to climate action at a global level, BEIS’s predominant focus on middle-income countries is defensible only as part of a wider strategy across UK International Climate Finance as a whole that also addresses the needs of low-income countries on low-carbon development.

DFID has a clear strategy for promoting low-carbon development in the energy sector but not in its wider portfolio

DFID’s largest and longest-running programmes on low-carbon development are in the energy sector. DFID developed an Energy Policy Framework in 2015. It lists ‘enhancing environmental sustainability’ as one of three objectives for the sector, alongside supporting economic development and ensuring equitable energy access. It states that DFID will help developing countries ‘leapfrog’ to clean and renewable energies, tackle inefficient fossil fuel subsidies and other barriers to the uptake of clean energy, develop markets for off-grid solutions and invest in sustainable cities with energy-efficient building designs and transport systems.

The commitments include working with partner countries on policy, planning and regulatory reform – for example by creating a clear legal framework for investments in off-grid energy markets. To that end, DFID’s Energy Africa initiative is developing ‘compacts’ with 14 African countries which identify measures to improve the business environment for off-grid solar power (such as by removing tariffs on imported equipment).

The Energy Africa initiative also contains a section on leveraging private finance into the energy sector. This goal is common to many initiatives and is being pursued through a number of routes. The Private Infrastructure Development Group, which ICAI assessed as part of the review of DFID’s transport and urban infrastructure investments, supports renewable energy projects through forms of funding designed to reduce the risks for other investors. The largest development capital investments into clean energy by DFID are made through the UK’s development finance institution, CDC. CDC has established an off-grid solar debt initiative with up to $150 million in funds for lending to companies. In 2017, it also established a Resource Efficiency Facility to provide project preparation grants and low-cost loans to CDC investee companies to encourage them to invest in projects that reduce their emissions. DFID’s contribution to CDC was its largest commitment to low-carbon development (£86 million) in our review period. CDC is the subject of a separate ICAI review.

In the review period, DFID’s bilateral investments in low-carbon development have predominantly been in the renewable energy sector. By way of illustration, assistance includes the following:

- The Solar Nigeria Programme (£66 million; 2014-2020) is installing solar power in 200 schools and eight health centres in Lagos state, while seeking to expand the commercial market for solar power products in northern Nigeria. This support is complementary to DFID health and education programmes in Nigeria.

- The Transforming Energy Access programme (£65 million; 2016-2022) supports the early-stage testing and scale-up of innovative technologies and business models to deliver affordable and clean energy to poor households and enterprises, primarily in Africa. The programme includes research, capacity building and impact investment. It involves a partnership with the Shell Foundation, which provides co-financing as well as leading on one of the six programme components on accelerating enterprise-led innovation in technology business models.

• The Sustainable Energy for Women and Girls programme (£17.8 million; 2015-2019) promotes market-based energy solutions across Africa that particularly benefit women and girls, including promoting clean cookstoves (and research to generate behavioural insights around their uptake), electrification of health facilities with a focus on maternal and neo-natal health, and promoting the embedding of gender into Sustainable Energy For All, a multilateral initiative established in 2011 to promote implementation of Sustainable Development Goal 7 on universal energy access.

Overall, we find that DFID has a credible approach to mainstreaming low-carbon development in the energy sector. It has a clearly articulated strategy through the Energy Policy Framework that is reflected in its programming. While this has been shared with stakeholders, the Framework has not been published externally.

We have found no equivalent approach in other sectors important for low-carbon development. DFID’s 2015 infrastructure strategy makes only passing references to low-carbon development objectives, despite this being a key sector for low-carbon development given the long lifespan of infrastructure investments. There are no references to low-carbon development in DFID’s ambitious targets for water, sanitation and hygiene, or in its conceptual framework on agriculture.

DFID’s emerging portfolio on cities and urban development, which we covered in another review, offers additional opportunities to promote low-carbon development. The programming remains at an early stage, however, and the examples we reviewed were focused on promoting resilience to climate change, rather than low-carbon development. We are informed that a new government-wide strategic approach to Africa will include the promotion of low-carbon and climate-resilient investments in Africa.

DFID’s approach to integrating climate finance has fallen short of its ambitions

Since 2014, DFID’s approach to climate finance has progressively shifted from a set of dedicated programmes to integrating climate action across its portfolio. There is a good case to be made for this: low-carbon development is a principle that should be integrated across all development assistance, rather than a separate sector or type of activity.

However, we have significant concerns about the way that DFID has approached integration. DFID has not articulated its objectives for, or approach to, low-carbon development beyond the energy sector, nor has it articulated the principles that should govern integrated programming. The 2011 joint strategy UK ICF Tackling climate change, reducing poverty55 defined the purpose and priorities of UK international climate finance, but has not been updated. DFID’s 2015 Adaptation Strategy Refresh set out its approach to making its investments resilient to the expected impacts of climate change (adaptation), but DFID has no equivalent strategy that articulates an overall approach to integrating low-carbon development objectives into its programming. According to senior stakeholders, the approach has been left to emerge in a bottom-up and organic way, with country offices taking the lead. A 2018 evaluation of the integration of International Climate Finance in DFID programmes found variable performance across country offices as a result.

We are concerned about this lack of leadership and support. The process of moving from dedicated climate change programmes to mainstreaming climate action across the portfolio is a complex one. From ICAI reviews of other mainstreaming initiatives, including disaster risk reduction and disability, we found that a concerted effort was needed to put in place the right systems, capacities and incentives to integrate cross-cutting objectives.

There is a perception among the interviewees for this portfolio evaluation that the priority DFID places on climate change has reduced over the past two years, which has reduced the motivation to include climate change action in programmes.

Portfolio Evaluation I – Integration of ICF. HMG Compass, Final Report, 2018, unpublished