UK humanitarian aid to Afghanistan

1. Introduction

1.1 In November 2022, the Independent Commission for Aid Impact (ICAI) published UK aid to Afghanistan, a review of UK official development assistance (ODA) spending in Afghanistan from 2014, when British troops ended their combat role in Helmand province, to the Taliban takeover in August 2021. The review included a non-evaluative annex on humanitarian aid since 2021, which was subsequently updated and published as an ICAI information note in May 2023.

1.2 This information note updates the 2023 publication. It provides a descriptive (non-evaluative) account of UK humanitarian aid to Afghanistan since the Taliban takeover in August 2021, focusing primarily on developments over the past year. It examines how the context and UK approach have changed since our last update. It concludes with the same ‘lines of enquiry’ – that is, areas that warrant further consideration by the government, ICAI or other bodies – identified in our May 2023 information note.

1.3 The information note draws on documentation from and interviews with the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO) and the partners it funds, and interviews with other humanitarian actors, including UN agencies and non-governmental organisations (NGOs) working in Afghanistan. Interviews were conducted both remotely and in person in Kabul and Doha. In May 2024, ICAI Commissioner Sir Hugh Bayley visited Afghanistan with the UK’s Doha-based Head of Mission to Afghanistan, where they met UN agencies and local and international NGOs supported by the UK.

2. Update on the situation in Afghanistan

2.1 Humanitarian needs in Afghanistan continue to be great in 2024, albeit somewhat less so than at the end of 2023. The country remains among the world’s most food-insecure: the Integrated Food Security Phase Classification (IPC) estimated that, in the period March to October 2024, 14.2 million people will experience high levels of acute food insecurity, including 2.9 million at emergency levels of food insecurity. Acute malnutrition is above emergency thresholds in 25 out of 34 provinces. Women-headed households and people with disabilities are particularly vulnerable.

2.2 Afghanistan is highly susceptible to climate change and extreme climate shocks. This year is the third in a row with drought-like conditions, with dry winters followed by erratic spring rains and floods. The country’s acute water crisis is worsening, with 67% of households struggling to access safe water in 2023, compared to 48% in 2021. Afghanistan’s mean annual temperature has risen by almost twice the global average since 1951, and climate-change models predict that future temperatures will continue to rise faster than the global average. Annual droughts are predicted to become the norm in many parts of the country by 2030.

2.3 Since ICAI’s last update in May 2023, frequent severe weather events, including heavy rainfall, flash floods and droughts, have damaged livestock, agricultural land, homes and critical infrastructure. Floods in May 2024 in the northeastern provinces of Badakhshan, Baghlan and Takhar led to more than 300 deaths and more than 1,600 injuries.

2.4 In Herat province, the damage from severe weather events was compounded in October 2023 by a series of earthquakes that killed more than 2,400 people. The quakes destroyed 21,500 homes and severely damaged another 17,000, impacting more than 154,000 people. Repairs to damaged infrastructure, including health facilities, are estimated to cost $217 million, with economic losses estimated at almost $80 million.

2.5 Access to health services has deteriorated, with limited availability of essential medicines, equipment and qualified personnel. Save the Children reports a sharp rise in children under the age of five dying from pneumonia in 2024.

2.6 More than six million of Afghanistan’s population is internally displaced. Numbers have increased in the past year, after Pakistan’s minister of interior in early October 2023 announced a plan to repatriate all undocumented foreigners. This primarily affected Afghans, many of whom had lived for years or decades – in many cases all their lives – in Pakistan. More than 562,000 Afghan refugees have since returned, straining the absorption capacity of the areas in which they settle. For example, Nurgal district in Kunar province is projected to experience a population increase of more than 50% in 2024. The majority of returnees are children or adult manual labourers from urban settings in Pakistan, which makes their economic integration into predominantly rural areas in Afghanistan challenging.

The economic situation

2.7 Afghanistan’s economy has contracted dramatically since the Taliban took control of the country in August 2021. The World Bank reports a 26% drop in real Gross Domestic Product (GDP) over the past two years, worsened by the October 2023 Herat earthquake. The annual deflation rate from February 2023 to February 2024 was -9.7%. Da Afghanistan Bank (DAB), the central bank of Afghanistan, has reported a significant decrease in money supply as a result of sanctions, frozen assets, banking disruptions, domestic payment-system problems and a shift to Islamic banking. By April 2024, the afghani had appreciated 22.8% against the US dollar since the fall of Kabul to the Taliban in August 2021. While this has helped reduce the costs of imported goods, it has increased the cost of Afghanistan’s exports on the international market, hampering economic growth and widening the country’s trade deficit.

2.8 Restrictions on the movement, employment and other rights of women and girls, including a ban on education above the primary level, have limited the participation of Afghan women in the workforce, causing further economic contraction. The employment rate for working-age women has halved to 6% over the past year.

2.9 According to the World Bank, the Taliban’s April 2022 ban on opium cultivation has led to a $1.3 billion loss in farmers’ incomes (from an estimated $1,360 million for the 2022 harvest sale to $110 million in 2023), equivalent to approximately 8% of GDP. The UN Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) estimates that opium production has contracted by 90% following the ban.

Human rights, including the rights of women and girls

2.10 Nearly three years after the Taliban seized power, there are regular reports of human rights violations, including extrajudicial killings, torture, arbitrary arrests and detentions. Women and girls continue to be marginalised from almost all forms of public life, and their ability to work, including in the humanitarian sector, remains restricted. Since August 2021, more than 100 Taliban edicts have directly impacted on women’s and girls’ human rights. In April 2024, Taliban leader Hibatullah Akhundzada announced that the Taliban would enforce stoning and flogging as punishment for women accused of adultery.

2.11 UN agencies have warned that the exclusion of women and girls from most facets of life has reinforced existing gender inequalities, increased protection concerns and will have long-lasting impacts on the education sector. The Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights in Afghanistan describes a “phenomenon of an institutionalised system of discrimination, segregation, disrespect for human dignity and exclusion of women and girls”. Human-rights defenders, the UN Secretary-General, many UN member states and a range of international human-rights experts, have described the treatment of women and girls in Afghanistan as gender apartheid.

2.12 The 24 December 2022 edict from the Ministry of Economy prohibiting Afghan women from working with non-governmental organisations (NGOs) providing humanitarian assistance had a severe effect on delivery. While exemptions were eventually issued for the health and education sectors following representations from aid workers and the international community, the ban was extended in April 2023 to include UN female staff, which further affected humanitarian activities across the country. A year on, following several months of negotiations by donors and partners with the Taliban, some of the suspended humanitarian programmes have now resumed and even expanded operations. According to a survey conducted by UN Women across partner NGOs, INGOs and UN agencies in March 2024, ten months from the first ban on women aid workers, 45% of the organisations reported partially operating with women and men while only 27% were fully operating with women and men.

2.13 In the past year the Taliban has also introduced other measures to limit women’s roles, including issuing official letters to several NGOs requesting the removal of women from leadership positions and as signatories for bank accounts. Implementing partners have reported that documents signed by Afghan women, or projects mentioning that women are among people expected to benefit, have been rejected.

2.14 The 2024 World Press Freedom Index ranks Afghanistan as third worst in the world for press freedom. Afghanistan has lost more than 80% of its female media workforce. In April 2024, the Taliban suspended the broadcast of two privately run local TV channels over alleged violations of official regulations and ‘Islamic values’, notably that female hosts and guests were not following the official dress code. Some Taliban directives prohibit the broadcasting of female voices and radio and television channels from accepting phone calls from women and girls in certain provinces.

2.15 The Taliban appears to have adopted a somewhat less restrictive approach to women working in the private sector – although it ordered the closure of beauty salons employing tens of thousands of women. According to the Afghanistan Women’s Chamber of Commerce and Industries, some 120,000 women-led businesses are active in Afghanistan, mainly in the areas of carpet weaving, clothes manufacturing, jewellery, fruit processing and other areas in agriculture. We were told in Kabul that it is easier for women to register small businesses than NGOs, and that business support may be a useful way to support women in work and positions of leadership. The UN Development Programme (UNDP) says that women-run businesses “emerged as a lifeline” for women in Afghanistan, although challenges such as movement restrictions remain, with 73% of participants surveyed by UNDP being unable to travel even to local markets without a mahram (male chaperone).

2.16 A mental-health counselling service in the country told ICAI that teenage girls whose schools have been closed are its biggest client group and that suicide among girls is increasing. One female NGO employee said, “Things for women get worse day by day.” Another told us, “Women are losing what we gained in the last two decades.” There is, however, a level of popular resistance. As suggested in our previous information note, there are differing views inside the Taliban, with hardliners arguing for more restrictions on women and pragmatists willing to be flexible in the face of popular discontent. Most implementing partners say that they have negotiated ways to continue involving women in the delivery of humanitarian assistance. The country director of one international NGO said, “We have flipped their ban on women NGO workers to our advantage. The Taliban says women should look to women for support, so we meet that need.” In these circumstances, continuing international support for Afghan NGOs, especially those led by women, may be helping to preserve a voice for women.

The security situation

2.17 With the Taliban no longer involved in violent insurgency, all stakeholders agreed that the overall security situation had improved since the fall of Kabul in August 2021. Very few attacks directly targeting humanitarian organisations or staff have been reported since 2021. However, the Taliban itself faces a growing threat from insurgent groups, including Islamic State Khorasan Province (ISKP), which has also claimed responsibility for attacks in Russia and Iran. In recent months, there have been attacks on community health clinics, and humanitarian workers are at risk of collateral damage.

2.18 ISKP has also been responsible for an increasing number of attacks against Hazaras and the wider Shia community, giving rise to concerns that the Taliban is doing little to guarantee the safety of religious minorities. ISKP also claimed responsibility for an attack in May 2024 in Bamyan province that killed three Spanish tourists – the first to target foreign nationals since December 2022.

2.19 All stakeholders interviewed highlighted the growing threat from ISKP and the Tehreek-e-Taliban Pakistan, an ideological offshoot of the Afghan Taliban, and their potential for wider destabilisation. The UN has warned that groups based in Afghanistan present a threat to the stability of the region and potentially beyond.

2.20 Despite an improved security context, the operating space for humanitarian actors in Afghanistan continues to be severely constrained. A year after the publication of ICAI’s previous information note, there have been slight improvements, but access to populations in need remains hampered by restrictions placed on female aid workers, bureaucratic impediments and threats against humanitarian personnel and assets.

2.21 According to the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs’ (OCHA) Access Monitoring and Reporting Framework, 156 access incidents were reported by humanitarian partners in April 2024. A smaller number of incidents (113) were reported in May, the latest data available. Most (60% in April and 57% in May) of the reported incidents involved ‘interference in the implementation of humanitarian activities’ by the Taliban, resulting in the temporary suspension of 107 projects in April and 69 in May. The documentation reviewed by ICAI also highlighted instances of female staff being stopped, questioned and detained for several hours.

3. The international response

The provision of humanitarian aid

3.1 Around 23.7 million people are projected to need humanitarian assistance in 2024, down from 28.3 million in 2023. This slight improvement mainly reflects the food-security situation, linked to improved cereal harvests and lower food prices. The share of people categorised as acutely food insecure fell from 40% in April 2023 to 32% in March 2024. For the post-harvest period (May to October 2024), 28% of the population is projected to fall into the acutely food-insecure category – compared to 35% during the same period last year.

3.2 Despite limited funding, in 2023 humanitarian partners in Afghanistan helped 32.1 million people with at least one type of assistance, such as food aid, health care, education and water, and sanitation and hygiene (WASH). The UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) launched a $96.3 million emergency appeal to support a multi-sector response plan after the Herat earthquake in October 2023, which subsequently became part of the 2023 Humanitarian Needs and Response Plan (HNRP). Several national and international non-governmental organisations (NGOs) also launched appeals to raise funds for their planned responses to the earthquake.

3.3 The 2024 HNRP, released in December 2023, appeals for $3.06 billion, with 23% of this funded at the time of writing. OCHA’s April 2024 funding gaps analysis shows a decline in the quality, coverage and timeliness of urgent and lifesaving food assistance, nutrition and basic health services, especially in remote and hard-to-reach areas. Multiple crisis responses, including to earthquakes, floods and largescale refugee return movements, have depleted resources, limiting the capacity to respond to future disasters. There has also been insufficient investment in critical-shelter services and infrastructure, alongside reduced protection services.

3.4 Several stakeholders interviewed by ICAI were concerned that Afghanistan had become a ‘forgotten crisis’, as donor fatigue and other competing crises (in Ukraine and Gaza in particular) have led to significant cuts to assistance programmes. In 2023, the World Food Programme (WFP) received 64% less in direct contributions than the previous year for its work in Afghanistan, leading to the reduction of emergency food assistance for ten million people and rations being reduced from 75% to 50% of the recommended calorific intake. One implementing partner said, “How do I explain to a widow why they have been cut from aid when I know she and her four kids rely on it?”

3.5 Despite tensions over access and coordination, organisation of the aid architecture has been strengthened since ICAI’s previous update. An International Organisation for Migration (IOM) consortium created in late 2023 to deal with refugee returns from Pakistan is one example of improved coordination. Several UN agencies interviewed reported a relatively high, and improving, level of coordination with the Taliban when responding to crises such as the Herat earthquake and returns from Pakistan.

3.6 The increase in coordination is driven by the need to coordinate responses to Taliban edicts and requirements. Stakeholders interviewed by ICAI noted that a considerable amount of time is spent negotiating access with the Taliban authorities at district, provincial and national levels, each of which can impose restrictions (including requiring permission for female staff to operate). WFP notes “a discernible increase in the [Taliban] de facto authorities’ level of governance and assertiveness, necessitating a corresponding rise in negotiating and coordination efforts.”

International engagement with Afghanistan

3.7 Commissioned in March 2023 by the UN Security Council, an independent assessment on Afghanistan was presented by the UN Secretary-General in November 2023. It found that “the status quo of international engagement is not working” and called for a political pathway to address the concerns of all sides – the Afghan people, the international community and the Taliban – that would lead to “a secure, stable, prosperous and inclusive Afghanistan” being fully re-integrated into the international system. The assessment recommended international dialogue with the Taliban, potentially opening the way to an eventual resumption of international development assistance. Specifically, it proposed:

- the continuation of the meetings of special envoys and special representatives initiated by the Secretary-General in May 2023 (called Doha I, II and III)

- a small international contact group to coordinate action and approaches among international stakeholders

- the appointment of a UN special envoy to enable engagement among international and Afghan stakeholders.

3.8 The Security Council took positive note of the findings in its Resolution 2721 in December 2023. Doha I and Doha II took place in May 2023 and February 2024 without participation of the Taliban, which opposes the appointment of a UN envoy. On 21 June 2024, the Taliban signalled their intention to attend Doha III talks, which a UK statement to the Security Council welcomed while also emphasising the urgent need for the Taliban to reverse policies restricting human rights, especially for women and girls. Doha III took place on 30 June and 1 July 2024, which the Taliban attended, but insisted that Afghan women and NGOs could not be present in meetings they participated in. If ultimately successful, the Doha process may help create a pathway for Afghanistan’s development as it could enable gradual access to multilateral economic aid and climate-adaptation finance.

3.9 The international community’s response to the Taliban remains fragmented. No country formally recognises the Taliban as the legitimate government of Afghanistan, but China, Russia and Iran have established embassies in Kabul, are pursuing trade and appear to be encouraging the regime to distance itself from Western countries. Other regional neighbours, including Pakistan and the Central Asian republics, despite concerns over regional security, are exploring ways of expanding trade with Afghanistan. Among donor members of the Development Assistance Committee of the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD-DAC), only Japan and the European Union retain a physical presence in Kabul. Turkey (an observer to the OECD-DAC) also has a presence.

3.10 Western donors have condemned the Taliban’s human-rights record but to little effect.46 Opinions remain divided on what level of engagement with the Taliban is appropriate. While the UN and donors were united in condemning the Taliban’s restrictions on female humanitarian workers, two of the stakeholders we interviewed expressed disappointment at what they saw as a failed opportunity to impose ‘red lines’ on the Taliban. However, the UK and other donors took the view that international humanitarian operations could not be suspended during a humanitarian crisis.

3.11 International NGOs working in Afghanistan have strongly encouraged international donors to re-establish a presence in Afghanistan, to gain a better understanding of realities on the ground and to engage with the Taliban to protect the operating space for humanitarian actors. The UK and a number of donors are reportedly considering doing so, recognising that the Taliban is likely to remain in control for some time. There is also growing awareness that the lack of engagement from the donor community is creating a vacuum that other regional powers could attempt to fill.

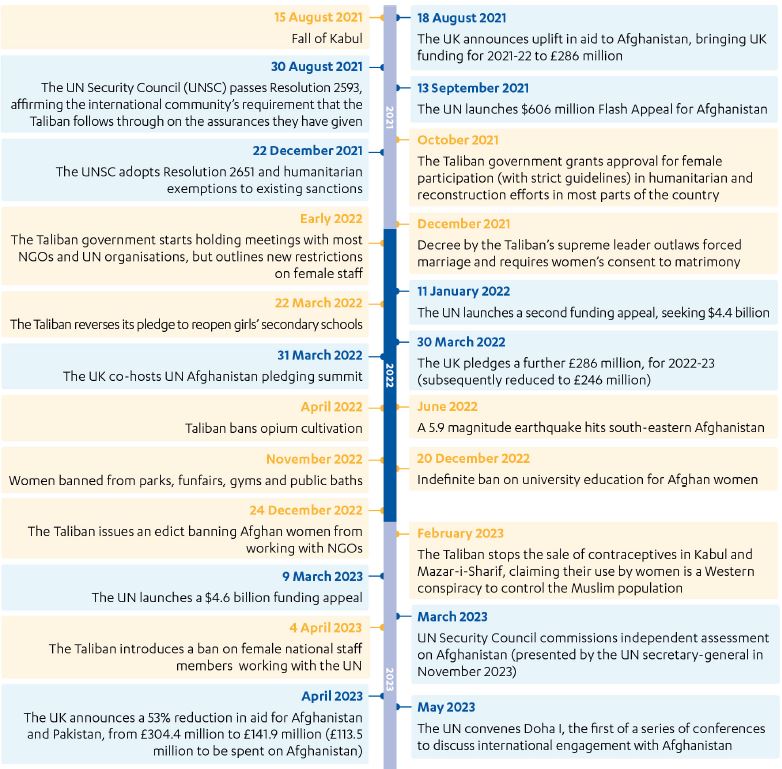

Figure 1: Timeline of key dates since August 2021

4. UK aid to Afghanistan

Objectives

4.1 The UK’s goals in Afghanistan are set out in a cross-government Afghanistan Country Plan. They include protecting the UK from harm, providing emergency humanitarian assistance, building resilience, promoting stability, encouraging an inclusive political settlement and human rights, and delivering a strong resettlement scheme in the UK. The National Security Council (NSC) has identified a number of threats to UK interests originating from Afghanistan, including terrorism, narcotics and irregular migration to the UK.

4.2 The UK’s objectives for work funded by official development assistance (ODA) in Afghanistan are guided by the November 2023 International Development White Paper, the UK Strategy for International Development and the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office’s (FCDO) Humanitarian Strategic Framework, which states that UK humanitarian programmes will prioritise aid to those in greatest need, deliver protection services, and support better prevention and preparedness. The UK’s goals are pursued through aid programmes, diplomatic engagement, policy and strategy development and other tools.

Expenditure

4.3 Like other international donors, the UK suspended development assistance for Afghanistan in August 2021 following the Taliban takeover. However, total UK aid to Afghanistan increased, as the UK joined in a major international humanitarian response. The UK announced a doubling of support to £286 million for each of the 2021-22 and 2022-23 financial years. The 2022-23 allocation was subsequently reduced to £246 million, resulting in activities being halted or rephased in programmes for polio inoculation and mine clearance.

4.4 Having spent 95% of its revised budget by late November 2022, the UK was left with limited funds for the remainder of 2022-23. As a result, funding intended to be spent through the World Bank-administered Afghanistan Reconstruction Trust Fund (ARTF) was rephased to 2023-24, which enabled the remaining financial allocation to be spent on humanitarian programming.

4.5 UK aid for Afghanistan has now fallen back to the level seen before the Taliban takeover. In March 2023, the Development Minister Andrew Mitchell announced a combined ODA budget for Afghanistan and Pakistan for the financial year 2023-24 of £141.9 million, less than the previous year’s budget. FCDO spent £113.5 million in Afghanistan in 2023-24, largely on urgent humanitarian needs. The UK’s planned bilateral support for Afghanistan for 2024-25 is £151 million.

Choice of partners

Table 1: Bilateral allocation by implementing partner for the financial years 2021-22, 2022-23, 2023-24 and provisional figures for 2024-25

| Financial year allocations for 2021-22 | Financial year allocations for 2022-23 | Financial year allocations for 2023-24 | Financial year allocations for 2024-25 25 (provisional allocations subject to ministerial review) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| UN Development Programme / Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs – Afghanistan Humanitarian Fund | £91 million | £50 million | £5 million | £6.1 million |

| World Food Programme | £93 million | £95 million | £38.7 million | £40 million |

| United Nations Children's Fund | £27 million | £28 million | ||

| International Committee of the Red Cross | £23 million | £16 million | £16 million | |

| International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies | £7 million | £4 million | £1 million | £3 million |

| Disasters Emergency Committee | £10 million | |||

| UN Refugee Agency | £8 million | |||

| International Organisation for Migration | £7 million | £12.2 million | £11.5 million | £10 million |

| Norwegian Refugee Council | £4.1 million | £7.9 million | £0.2 million | |

| UN Population Fund | £2.2 million | £8.1 million | £6.2 million | £5.6 million |

| International Rescue Committee UK | £2 million | £9.2 million | £0.8 million | |

| Global Mine Action Programme | £10 million | £2.5 million | £3 million | |

| Supporting Afghanistan’s Basic Services NGOs | £12.2 million | £14.8 million | £0.5 million | |

| Humanitarian & Supporting Humanitarian Assistance NGOs | £0.9 million | £10.8 million | ||

| Humanitarian & Food Security & Livelihoods NGOs | £2.6 million | £19 million | ||

| World Bank’s International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (IBRD) (Afghan Reconstruction Trust Fund) | £8.8 million | £18.3 million | ||

| Planned programming to support basic services and household livelihoods – under design | £29.5 million | |||

| Other (monitoring, learning etc) | £1.7 million | £3.4 million | £4.5 million | £5.2 million |

| Total | £286 million | £246 million | £113.5 million | £151 million |

4.6 The UK government and its implementing partners in Afghanistan recognise the need to channel more support through Afghan national NGOs and civil society organisations. ‘Localising’ aid flows helps keep Afghan civil society, and especially women-led organisations, functioning, despite the Taliban’s many restrictions on their operations. For example, in partnership with the Agency Coordinating Body for Afghan Relief and Development (ACBAR) and supported by FCDO funding, the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) has been running training programmes and workshops to help national NGOs apply for and manage international funding. As managers of the Afghanistan Humanitarian Fund (AHF), they have taken measures aimed at increasing the share of funding allocated to national delivery partners to around 25%.

4.7 In the financial year 2023-24, FCDO reduced its funding for AHF and the World Food Programme (WFP) and allocated funding to NGO consortia that include national NGOs and delivery partners. The Supporting Afghanistan’s Basic Services (SABS) programme supports the delivery of essential services, particularly health and education, along with some livelihoods support, with a particular focus on women and girls. We were told that gender inclusion would be mainstreamed across the work of all partners, in the context of an overall aim for at least 50% of the UK’s support in Afghanistan to be reaching women and girls.

4.8 The July 2023 UK-Afghanistan development partnership summary specified that 70% of UK aid to Afghanistan in 2023-24 would focus on humanitarian response, while 30% would support basic human needs, helping to build resilience and reduce humanitarian need.52 FCDO has developed two flagship humanitarian programmes to replace the Afghanistan Multiyear Humanitarian Programme (MYHRP), which closed in 2023: the Supporting Humanitarian Assistance and Protection in Afghanistan programme (SHAPE) and the Afghanistan Food Security and Livelihoods Programme (FSL). While programmes continue to be delivered primarily by international partners, FCDO has sought to increase the role of national NGOs in delivery. The UK plans to expand bilateral support to health, education and livelihoods for the Afghan population, going beyond the SABS programme, which has worked to deliver immediately required essential services.

The UK’s role and influence

4.9 FCDO’s documents note the importance of ‘humanitarian diplomacy’ – that is, using UK influence to help strengthen the international humanitarian response. UN partners in Afghanistan described the communication and support they received from FCDO as positive. They noted that they met with London-based FCDO officials monthly, and that FCDO was an active user of the data and information shared with it.

4.10 FCDO is working to improve the coherence of international efforts, both at the aid-delivery and diplomatic levels. The UK supported UN Security Council Resolution 2721, actively supports the Doha process and was instrumental in the renewal of the UN Assistance Mission in Afghanistan’s mandate and sanction policies. It also hosted a forum of G7 Special Representatives to Afghanistan in London in January 2024. It is a founding member of the Afghanistan Coordination Group (ACG) and active in its thematic working groups, including an informal group on capacity development. The UK is also one of three donors with observer status on the UN humanitarian country team in Afghanistan. The UK has also worked at the diplomatic level to unlock funding for basic services and livelihoods support for the Afghan people. Since August 2021, more than $2 billion has been made available from the Asian Development Bank and the World Bank’s ARTF for health, education, livelihoods and food security, with a focus on the needs of women. In February 2024, the UK worked with others to secure endorsement of the World Bank’s approach to supporting basic services, particularly those benefiting women, which is delivered through the ARTF and complements bilateral funding from donors.

Risk management

4.11 During the process of carrying out the follow-up to our 2022 country portfolio review of UK aid to Afghanistan, FCDO described to us the changes it has made in its approach to managing risk. These include improved context analysis and use of scenario planning, which are now better embedded into strategic planning and operational management. New risk management toolkits have been developed as part of a wider push across government to strengthen strategic management.

4.12 FCDO’s Afghanistan Policy and Programme Department (APPD) has sought to address weaknesses in risk management through creation in March 2023 of an access and interference humanitarian adviser role, contracted via the FCDO-funded Humanitarian and Stabilisation Operations Team (HSOT). The adviser provides security and contextual analysis to improve risk management, contingency planning and preparedness, and helps to convene and coordinate NGO and UN partners. Strengthening these partnerships has enabled FCDO to continue monitoring risks and contextual changes, in the absence of a direct presence in Afghanistan.

4.13 FCDO documents report that these efforts have helped improve information sharing, particularly on humanitarian access, contributing to more joined-up delivery of humanitarian programmes. In interviews, other partners were appreciative of the expertise provided by the access and interference humanitarian adviser, and noted resulting improvements in the quality of dialogue among partners.

4.14 The UK continues to operate without a permanent base in Afghanistan. Since October 2023, FCDO officials have visited regularly, engaging in dialogue with a range of national and international actors. Reportedly, these visits have helped FCDO gain important insights into the challenges facing Afghan citizens.

4.15 The first visit with a specific focus on aid programming took place in May 2024, and there are plans for regular visits by UK aid officials. Visiting regularly, or establishing a more permanent presence within the country, could improve the oversight and management of UK aid.

Monitoring

4.16 FCDO incorporates third-party monitoring arrangements in some of its programmes. These monitoring arrangements are managed separately from programme delivery and are used to verify on a sample basis whether UK aid is reaching the intended recipients and achieving its targeted results. FCDO also established an Assurance and Learning Programme in 2022 to strengthen oversight across the Afghanistan bilateral portfolio.

4.17 Like other donors, FCDO is particularly concerned about monitoring the risks of aid diversion or denial of humanitarian access by the Taliban. Some implementing partners in Afghanistan expressed concern to us about the level of monitoring imposed by donors. One senior official who has been in Afghanistan since before the fall of Kabul said, “I have never seen a place where aid is as highly monitored as Afghanistan.” ICAI was told that FCDO believes that rigorous monitoring is needed in view of the high levels of UK aid, the lack of in-country presence and the high levels of risk involved in working in Afghanistan.

Box 1: Examples of UK aid-funded activities in Afghanistan

In our visit to Kabul, ICAI was able to view some examples of activities funded by UK ODA. In partnership with local NGOs, WFP provides cash and food assistance to vulnerable households, with priority given to women-headed households and individuals with disabilities.

ICAI visited a Midwifery Helpline, where a team of Afghan midwives and gynaecologists provide 24/7 telephone advice to midwives in remote areas on how to deal with complications in pregnancies and deliveries. They deal with 85 to 90 requests for advice a day. At present, 620 Afghan women die in pregnancy or childbirth for every 100,000 live births – the worst maternal mortality ratio in Asia.

The UK is supporting nutrition clinics. These support malnourished children and pregnant and breastfeeding women with food supplements, as well as providing education on nutrition and health. The number of under-5 children admitted into nutrition programmes in Kabul Province has risen rapidly, from around 10,000 in 2021 to more than 130,000 in 2023.

The UK also supports a range of livelihoods activities. ICAI visited a gem-cutting centre that trains individuals to cut and polish semiprecious stones, and to design and market jewellery. Trainees also receive literacy and business management training.

Results

4.18 FCDO reports suggest that UK aid has contributed to a range of outcomes through its direct support and through the multilateral programmes it funds.

Box 2: A selection of reported results of programmes funded by UK aid

Afghanistan Multiyear Humanitarian Programme (MYHRP, closed in 2023)

- The AHF helped provide emergency support for health, water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH), protection, shelter, food, livelihoods and education to 6.8 million people (3.4 million women and girls) between April 2022 and March 2023.

- FCDO funding also helped WFP provide 4.2 million people, including 2 million women and girls, with food aid or cash assistance between April 2022 and March 2023 and between June 2023 and August 2023.

Supporting Afghanistan’s Basic Services (SABS)

FCDO’s share of the funding (September 2022 to June 2023) helped provide:

- education for 125,000 children

- support for 3,300 teachers (including 1,200 women) with training or stipends

- cash for work for 15,000 people.

Afghanistan Reconstruction Trust Fund (ARTF)

- Health Emergency Response (HER): 7.5 million people received essential health, nutrition and population services, of whom 5.6 million were female; 1.17 million children were fully vaccinated and 723,823 births were attended at health facilities. (June 2022 to August 2023)

- Emergency Education Response Afghanistan (EERA): 199,678 children were given access to learning opportunities, of whom 73% were girls. (September 2022 to October 2023)

- Emergency Food Security Project (EFSP): 412,873 farmers were reached with agricultural assets or services, of whom 112,603 were female. (April 2022 to November 2023)

- Community Resilience and Livelihoods (CRL): 776,102 households received livelihoods support. (April 2022 to January 2024)

Global Mine Action Programme (GMAP)

- 4 million square meters of land safely were cleared of mines and unexploded ordinance and released to communities. (April to December 2023).

- 117,237 people received explosive ordnance risk education (EORE) sessions. (April to December 2023).

Support for women and girls

4.19 Support for women and girls is a core FCDO objective in Afghanistan. Under its International women and girls strategy 2023-2030,59 FCDO commits to ensuring that at least 80% of its bilateral aid programmes have a focus on women and girls by 2030, with a particular focus on girls’ education, social, political and economic empowerment, and ending violence against women and girls. The Taliban ban on secondary and post-school education for girls will have long-term consequences for Afghanistan as well as for the girls directly affected. A female doctor in Kabul told ICAI, “After ten years there will be a catastrophe because no women will have been trained as midwives or gynaecologists.” In response to Taliban edicts restricting the rights of women and girls, FCDO developed an Afghanistan women and girls strategy for 2023-2027, which aims to protect Afghanistan’s most vulnerable women and girls, mitigate the worst effects of Taliban rule, and invest in the next generation of female leaders.

4.20 In 2022, the UK foreign secretary committed that women and girls would comprise at least 50% of the people reached through UK-funded programming in Afghanistan, across the portfolio. Reports from partners suggest that this target was achieved in 2021-22 and 2022-23. To support this commitment, FCDO has asked all its partners to disaggregate their results data by gender and where possible also by province, age and disability status. However, there is as yet no consistent methodology for doing so, resulting in some data gaps and inconsistencies. Table 2 below summarises some of FCDO’s reported results data for women.

4.21 FCDO supports Afghan women’s organisations, working through a range of partners to meet the critical needs for Afghan women and girls, including through programmes to tackle exploitation and abuse, provide reproductive health care services and emergency food provision. The UK will prioritise humanitarian support for women and girls under its humanitarian programming, with a focus on genderbased violence and child protection. Its programmes are designed to give women and girls a meaningful role in decision-making throughout the programme cycle.

4.22 At the diplomatic level, FCDO works with Muslim-majority countries and regional partners to engage the Taliban on the rights of women and girls. It also supports international commitments on equal access to aid for Afghan women, such as the non-paper developed by the ACG in April 2023 and the unpublished Guiding principles and donors’ expectations, following the ban on female NGO workers in Afghanistan developed by the UN Inter-Agency Standing Committee in February 2023.

Table 2: Reported results for women and girls to which UK aid has contributed

| UK aid | Reported results |

|---|---|

| Humanitarian assistance | • 3.4 million women and girls were reached through the AHF with emergency support for health, water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH); protection; shelter; food; livelihoods and education. (April 2022 to March 2023) • 1 million women and girls were reached by UNICEF with health, gender, WASH, nutrition and child protection support. (June 2022 to March 2023) • 2 million women and girls were reached by the WFP with food aid or cash assistance. (April 2022 to March 2023 and June 2023 to August 2023) |

| Health | • Through the ARTF Health Emergency Response (HER) project, FCDO has contributed to supporting 5.6 million women and girls with essential health, nutrition and population services. (June 2022 to August 2023) • Through the SABS programme, 76,000 women and children were reached with quality, lifesaving maternal or child health; and 140,000 women and children received vaccinations. |

| Education | • Through the ARTF Emergency Education Response Afghanistan (EERA) project, FCDO has contributed to supporting 145,765 girls to access learning opportunities. (September 2022 to October 2023) • Through the SABS programme, 1,200 female teachers were supported with training or stipends. |

| Livelihoods | • Through the SABS programme, 160,000 women were given livelihoods support, and 7,300 women gained improved access to finance through community saving groups. |

The humanitarian-development nexus

4.23 There is debate among international donors about when it would be appropriate to shift from humanitarian support to longer-term development assistance for Afghanistan. Some donors favour retaining a narrow focus on life-saving assistance, limited to alleviating hunger, responding to natural disasters and meeting essential needs such as shelter, water and sanitation, and basic health care. They do not want, inadvertently, to strengthen the Taliban’s position by allowing them to take credit for aid-funded improvements in the lives and livelihoods of the Afghan people. FCDO does not fund the Taliban or deliver services through the government ministries and agencies they control. However, the department provides a broad range of humanitarian assistance, including some support to Afghan citizens to re-establish their livelihoods. For example, cash and food assistance is provided to destitute individuals in return for work on community infrastructure projects or participation in training.

4.24 FCDO’s approach seeks to strike a balance between responding to immediate humanitarian needs and building longer-term self-reliance, to reduce future humanitarian need. FCDO has also promoted more joined-up planning between humanitarian and development actors and engaged with the World Bank and other partners to ensure that funds to support the delivery of essential services are made available. This is consistent with the ‘humanitarian, development and peace nexus’ principle, which promotes pursuing the three objectives in parallel.

5. Lines of enquiry

5.1 We concluded our previous information note on UK aid to Afghanistan with some issues and questions, described as lines of enquiry, which we believed required further scrutiny or attention by the UK Parliament’s International Development Committee, ICAI or other bodies including the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO). One year on, these lines of enquiry retain their salience. We set them out again below, together with a brief description of some of the steps FCDO has told ICAI it has taken to address them over the past year. These updates are not comprehensive but reflect information ICAI received through our document review and interviews, as part of this nonevaluative information note.

1. How should the UK and other donors maximise the impact of humanitarian assistance while minimising the benefits which accrue to the Taliban authorities?

Updates:

- FCDO’s London-based humanitarian team made a first visit to Kabul in May 2024 and plans further visits to Kabul and, if the security situation permits, other Afghan provinces.

- FCDO uses its meetings with implementing partners and visits to Afghanistan to check that aid is not being misused.

- FCDO recognises that implementing partners need to meet Taliban officials to discuss issues such as humanitarian access and to prevent the diversion of aid from intended recipients.

- The FCDO is implementing an Assurance and Learning Programme to strengthen oversight of UK funded programming by providing third-party monitoring.

2. How can the UK move beyond a crisis response towards other modes of development assistance that build durable local capacities and reduce dependence on humanitarian aid?

Updates:

- Since August 2021, the UK government and other donors have worked together to make more than $2 billion available from the Asian Development Bank and the World Bank’s Afghanistan Resilience Trust Fund (ARTF) for health, education, livelihoods and food security.

- FCDO allocates 70% of its Afghanistan budget to humanitarian assistance, with the balance spent on a wider range of programming. FCDO has increasingly sought to take a longer-term approach to its programming and supported initiatives to sustain and strengthen national capacity.

3. What strategy should the UK and other donors adopt to preserve, as far as possible, the rights and opportunities which women and girls won before 2021?

Updates:

- FCDO informs us that it works with international partners to put consistent pressure on the Taliban on human-rights issues, including the rights of women and girls.

- The UK government has condemned the ban on Afghan women working for the UN and NGOs and continues to call for its immediate reversal.

- The UK government has committed to ensuring that 50% of those reached by UK assistance will be women and girls.

- FCDO is allocating a greater proportion of its aid through implementing partners to national NGOs, including women-led NGOs.

4. How should the UK respond to the risk that other donors may disengage from Afghanistan as a result of growing insecurity and the Taliban edicts?

Updates:

- FCDO told ICAI that the UK government shares information on humanitarian access with other donors and uses official donor events to encourage others to sustain funding.

- In February 2024, the UK worked to unlock further funding for basic services through the World Bank.

- The UK government has supported the UN’s independent assessment of Afghanistan and the Doha process to follow up on UN Security Council Resolution 2721, with the goal of maintaining focus and engagement from the international community and involving the Taliban in a political process which could lead ultimately to a normalisation of relationships.

5. Should the UK consider making the case within the international community for wider engagement with the Taliban, without implying that this may lead to recognition or normalisation of relations?

Updates:

- FCDO told ICAI that the UK government’s global policy is to recognise states, not governments.

- The UK supports careful and pragmatic dialogue with the Taliban, including pressing them on issues such as aid access, human rights and counter-terrorism, both bilaterally and with others.

- The Taliban attended the Doha III talks on 30 June and 1 July, which a previous UK statement to the Security Council had welcomed while also emphasising the urgent need for the Taliban to reverse policies restricting human rights, especially for women and girls.

6. What are the potential advantages and disadvantages of the UK re-establishing a physical presence within Afghanistan, when security conditions allow, to exercise more effective oversight of UK aid?

Updates:

- The FCDO’s Doha-based Mission for Afghanistan is now visiting Kabul regularly and examining the feasibility of visiting other provinces.

- Japan, Turkey and the EU have established representation in Afghanistan, and other donors are considering doing the same.

- FCDO informs us that the UK intends to establish a diplomatic presence in Kabul when the security and political situation in the country allows. It is coordinating this effort with like-minded states.