UK humanitarian aid to Gaza

1. Introduction

1.1 On 7 October 2023, Hamas-led military groups launched an attack on Israel from the Gaza Strip, killing more than 1,100 people and taking 253 hostages. In response, Israel launched a military campaign with the stated objectives of destroying Hamas and bringing the hostages home. The campaign has created a humanitarian catastrophe for Gaza’s 2.3 million residents. Over 35,000 people have lost their lives, and over three-quarters of the population have been displaced, with famine conditions already present in the north.

1.2 The UK has contributed to an international humanitarian response to the Gaza crisis, committing an additional £74.5 million in funding since October 2023. Restrictions on access to Gaza, further exacerbated by the ongoing incursion into Rafah by the Israel Defence Forces (IDF), have made it extremely challenging to deliver humanitarian relief to those in need.

1.3 Given high levels of concern among the British public about the crisis, this information note provides an account of how the UK government has responded, its efforts at the diplomatic level to improve humanitarian access, and its management of the risks associated with delivering aid in the midst of an ongoing conflict. Independent Commission for Aid Impact (ICAI) information notes are purely factual and do not reach evaluative judgements. This note complements a report published by the International Development Committee (IDC) on 1 March 2024. The UK government responded to the report on the 8 May 2024, partially agreeing or agreeing with all the recommendations. While this note does not offer recommendations, it concludes with a set of lines of enquiry that ICAI, or other scrutiny bodies, may take up in the future.

1.4 In preparing this information note, we have reviewed documents provided by the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO), and conducted interviews with UK officials and a range of other humanitarian actors involved in the response, including other donors, UN agencies and nongovernmental organisations (NGOs). We did not have any meetings with Israeli, Jordanian, or Egyptian actors. We reached out to the Israeli authorities but did not receive a response. The acutely difficult security conditions in Gaza hinder data collection, and the situation continues to evolve rapidly. In light of this, the data and figures in this report are drawn from the most authoritative and up-to-date sources as of 13 May 2024.

Figure 1: Gaza Pre-7 October 2023 key statistics and indicators

2. The humanitarian crisis in Gaza

Worsening humanitarian conditions

2.1 Seven months into the conflict, Gaza faces a humanitarian catastrophe. The territory was already experiencing high levels of humanitarian need, as a result of a long-running land, sea and air blockade. Since October 2023, it has faced what UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (UN OCHA) describes as ‘siege’ conditions. The IDF incursion into Rafah on 5 May, long regarded as a worst-case scenario, has precipitated another wave of displacement for Gazans who had been forced into the southern areas of the Strip.

2.2 The majority of land crossings into Gaza are closed. Electricity and most water connections have been cut off. Military operations have damaged more than 62% of housing and displaced over 1.7 million people. Unable to leave Gaza, most civilians are now living in desperately overcrowded shelters or tents. UN OCHA and other key actors in Gaza have explicitly stated that the areas to which civilians have been directed “lack infrastructure and basic services”. They are already overcrowded and unsuitable, and unable to absorb a new influx.

2.3 Even prior to the Rafah incursion, the destruction of hospitals and health care facilities, and casualties among health workers, had brought the health system to the brink of collapse, leaving tens of thousands of injured people without access to adequate medical treatment. The closure of the Rafah crossing on 7 May 2024 has halted the crossing of medical supplies, fuel, health care personnel, and the medical evacuation of patients in need. As of 13 May, the Health Cluster warned that without the immediate supply of fuel, “five hospitals and five field hospitals will only be able to sustain operations for less than 48 hours”. Experts are concerned about the ability of the remaining health care system to absorb additional casualties.

2.4 The supplies of food reaching Gaza, whether through commercial trade or humanitarian assistance, are wholly inadequate. Under the Integrated Food Security Phase Classification (IPC) used by the international humanitarian system, the entire population of Gaza is facing ‘catastrophic’ levels of food insecurity and northern Gaza is on the brink of famine. Over 50,000 children are estimated to be acutely malnourished. Referencing the IPC scale, the UN Secretary-General stated that this “entirely man-made disaster” has led to “the highest number of people facing catastrophic hunger ever recorded by the Integrated Food Security Classification system”. Box 1 provides a snapshot of current humanitarian conditions, as of 13 May 2024. Figures on the number of casualties are provided by the Gazan health ministry and do not distinguish between civilians and combatants. Many international observers have said they believe that the ministry’s overall toll is likely to be an understatement because of the numbers missing.

2.5 Humanitarian experts suggested that Gaza also faces escalating crises with mental health and gender based violence (GBV). There has been a total collapse of the pre-existing GBV referral pathway. There are no currently operational safe spaces for survivors of GBV. The United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) estimates that almost all of the 1.2 million children are in need of mental health and psychosocial support (MHPSS) in the Gaza Strip – twice as many children compared with pre-war estimates. It is likely that the available data understate the scale of the challenge in these areas.

Box 1: Gaza post 7 October 2023 key statistics and indicators

Fatalities

- Gaza: Over 35,091 fatalities with more than 7,700 children, and 1,924 elderly.

- Israel: 1,100 fatalities, including 71 foreigners, from the 7 October attacks and dozens of hostages killed in Gaza.

Displacement

- Over 1.7 million internally displaced persons (IDPs), 75% of Gazans. Most have been displaced multiple times, an estimated 450,000 as a result of the incursion into Rafah.

- On average 1 square metre of average space per person in IDP shelters.

Food

- 1 million people facing catastrophic levels of food insecurity (IPC Phase 5).

- > 50,000 children are estimated to be acutely malnourished.

Health sector

- 12 hospitals partially functioning, 24 hospitals out of service.

- 71% of primary health care facilities not functional (63 out of 89).

Civil infrastructure

- 83% of groundwater wells are not operating.

- >62% of residential property partially or fully destroyed. The destruction of infrastructure has resulted in an estimated 37 million tonnes of rubble.

Barriers to humanitarian access

2.6 There continue to be major restrictions on the ability of international humanitarian agencies to provide relief to the population in Gaza. As of 13 May, following the IDF incursion into Rafah on 6 May, the Rafah crossing remained closed and the Kerem Shalom crossing is handling severely limited quantities. A total of 59 trucks had reportedly crossed into Gaza in the period between 5 and 13 May, 49 of these through the Erez crossing in the north. Prior to 7 October, there were three functioning land crossings for the movement of goods, people and fuel in addition to four closed crossings, allowing for 500 trucks per day.

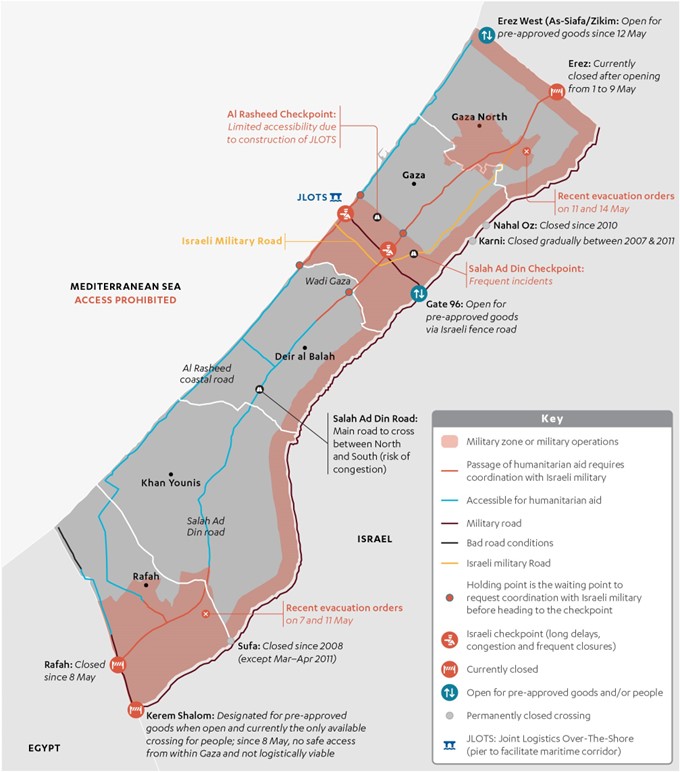

Figure 2: Map of Gaza and humanitarian access constraints

2.7 Prior to 5 May, there had been marginal, if inadequate, improvements in the quantity of aid crossing into Gaza. Following the killing of seven staff from the NGO World Central Kitchen on 1 April and under mounting international pressure, the Israeli government announced that it would open the port of Ashdod to humanitarian supplies and allow more aid into Gaza, particularly into the northern governorates where famine is imminent. FCDO officials informed us that up until the first week of May there had been some limited inconsistent progress, but this was still insufficient. Since the Rafah incursion, access conditions have further deteriorated.

2.8 Following the October attack, the delivery of supplies through land crossings has been tightly controlled by the Israel Defence Forces (IDF). Part of the restriction in access is due to convoys being subject to exhaustive inspections in order to prevent the delivery of ‘dual use’ items that might benefit Hamas. Trucks are frequently delayed or turned back, as reported by the IDC in March 2024. Stakeholders reported to ICAI an example of stone fruit being turned away as dual use. According to humanitarian agencies interviewed by ICAI, the IDF have also prevented the transport of critical equipment needed for humanitarian operations, including armoured vehicles, generators and fuel. It has also refused to allow humanitarian actors to establish or access a communications network, either radio, mobile or satellite.

2.9 Since October 2023, the Egyptian Red Crescent Society has been the only organisation able to transport aid into Gaza by truck from Egypt. All supplies to Gaza are sent via its Al Arish depot, which has limited capacity, and which is in a military-controlled zone where international organisations are not permitted to operate. Lengthy import and customs clearance procedures on the Egyptian border have also hindered aid delivery at scale.

Box 2: Governance arrangements in Gaza

Hamas (an acronym for ‘Islamic Resistance Movement’ in Arabic) is a Palestinian Islamic fundamentalist social, political and military resistance movement, formed in 1987. In 2006, Hamas won a majority of seats in the Palestinian legislative election and formed a short-lived national unity government with its rival, Fatah, which collapsed following the outbreak of conflict between the two groups. Hamas was ousted from any role in the Palestinian Authority in the West Bank, but seized control of the Gaza Strip and has remained the de facto governing authority.

Hamas does not recognise Israel’s right to exist, and is designated by the UK and many of its allies as a terrorist organisation (although some apply this designation only to its military wing). Its government in Gaza is not recognised by most Western countries and does not receive official development assistance, although it reportedly receives financial assistance from Iran and other regional allies.

Israel is not involved in the governance of Gaza, but controls access to the territory by land and sea. It has maintained a blockade on Gaza since 2007, tightly controlling the movement of goods and people, as well as access to services such as water and electricity. The blockade has been widely criticised by the UN and international humanitarian rights agencies for its impact on the civilian population. Many experts take the view that Israel has responsibility under international law for conditions in Gaza as the occupying military power, but this is denied by Israel.

Most basic services in Gaza are provided by the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East (UNRWA), established in 1950 with a mandate to support Palestinian refugees across the region. Before the latest conflict, UNRWA provided the majority of health and education services, social support (food and cash-based assistance) and humanitarian assistance within the territory. As the only UN agency with an established infrastructure, it is widely considered to be indispensable to the current humanitarian response. UNRWA states that it engages with Hamas only on operational matters, to arrange the delivery of humanitarian aid and ensure the safety of its staff.

2.10 The international humanitarian agencies interviewed by ICAI stated that they faced major restrictions on their ability to move around and operate within Gaza, over and above those related to border crossings. These include the Israeli Coordination of Government Activities in the Territories (COGAT) permissions for aid convoy movements within Gaza, as well as deconfliction, the destruction of roads and other infrastructure, fuel shortages and growing civil disorder. Aid convoys have been attacked by crowds and robbed by criminal gangs.

Box 3: ‘Deconfliction’ of humanitarian and military operations

‘Deconfliction’ is the practice of sharing information between humanitarian and military actors, including on planned humanitarian operations, to minimise the risk of humanitarian actors being inadvertently caught up in military activity. The COGAT, an entity within the IDF, operates such a system. However, it has repeatedly failed, with 244 aid workers killed in Israeli military operations since October 2023. This makes Gaza by far the most deadly conflict for humanitarian workers in the past two decades, leading to fears of long-term consequences for the protection afforded to humanitarian workers under international humanitarian law.

2.11 The conflict in Gaza, the restrictions on the delivery of assistance, and the reactions of key donor countries are seen as having the potential to destroy trust in the international humanitarian system and the internationally accepted frameworks which underpin it. Humanitarian experts cite the severe limitations on relief goods, the repeated military strikes on aid convoys, “the adversarial tone and critical public statements by the Israeli government vis-à-vis the aid response” and the “acquiescence (albeit over concerns and objections) of the US and other major powers”.

The international response

2.12 On 12 October 2023, the UN launched a humanitarian ‘Flash Appeal’ for $294 million for humanitarian operations in Gaza and the West Bank, including East Jerusalem, in the face of growing violence. On 6 November, the appeal was updated with a new financial requirement of $1.2 billion to cover 2.7 million people for the first quarter of 2024. It was updated again on 17 April 2024 to $2.8 billion to meet the needs of three million people, covering the nine-month period from April to December 2024.

2.13 This represents only part of the $4.1 billion that the UN and partners estimate is required to support the basic needs of 3.3 million people. The appeal reflects the UN’s assessment of the level of operations within the territory which will be possible within the current operating context. If access constraints are removed, there will be a need for humanitarian and recovery operations at a much larger scale. The response so far has been generous: as of 2 April 2024, the appeal is 90% funded, at $1.1 billion, from 111 donor entities.

2.14 The humanitarian officials interviewed by ICAI were in agreement that access, rather than funding, is the primary constraint on humanitarian operations. There have been repeated calls from the highest international levels, including from UN Secretary-General António Guterres and the G7, for an immediate ceasefire, and for humanitarian “pauses” and “corridors,” to allow the delivery of aid at the scale needed. The UN’s overriding objective is now to “flood Gaza with food”, to avert famine and reduce the risks associated with delivering aid to an increasingly desperate population.

2.15 There is also growing international pressure on Israel to ensure respect for international humanitarian law. On 26 January 2024, the International Court of Justice issued provisional measures in a case brought by South Africa, ordering Israel to cooperate with the UN to ensure “the unhindered provision at scale” of humanitarian assistance. The UN Security Council has passed three binding resolutions since 7 October. Resolution 2712, passed on 15 November, called for the immediate release of all hostages and for “urgent and extended humanitarian corridors and pauses” in Gaza. Resolution 2720 on 22 December demanded an increase in aid. On 25 March 2024, Resolution 2728 demanded an immediate ceasefire for the month of Ramadan, the immediate and unconditional release of hostages and an urgent increase in the flow of aid into Gaza.

2.16 A number of countries, including the US, Spain, Canada, Belgium, Italy and the Netherlands have either paused arms licenses or shipments to Israel, amid concerns that they might be used in violation of international humanitarian law. At the time of writing, the government has declined to publish their assessment of whether international humanitarian law has been breached but they have said that they have found no reason to cease arms sales to Israel.

3. The UK's humanitarian response

3.1 The Occupied Palestinian Territories (OPTs), comprising Gaza and the West Bank, are a longstanding recipient of UK development and humanitarian assistance. FCDO had allocated £27 million in bilateral support for the financial year 2023-24, of which £19 million was provided to UNRWA for essential service provision. The UK responded to the escalating conflict by allocating an additional £70 million for humanitarian support, with a further £16 million provided to UNRWA from the humanitarian programme. An additional £4.5 million for United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) activities for women and girls programming in Gaza was announced on 25 February.

3.2 In November 2023, the UK revised its humanitarian strategy (it has been revised twice since, with a further revision in train). The strategy initially focused on diplomacy, advocacy and flexible funding. Priorities were securing multiple humanitarian pauses, increasing humanitarian land access to Gaza, enabling the wider international response and restoring critical services. Most support has taken the form of flexible funding to established partners with an operational presence within Gaza (see Table 1 below). Given the speed and scale of population displacement and destruction of housing, in-kind donations of shelter and core relief items, with appropriate logistical support, were also prioritised. The response has been supported by a significant increase in FCDO advisory support, both in the UK and in the region.

3.3 According to government statements, the UK’s diplomatic objectives in response to the crisis include preventing further escalations of conflict, securing the release of hostages and supporting Israel’s right to self-defence, consistent with international law. They also include increasing the supply of humanitarian aid and improving humanitarian access in Gaza. Given the challenges involved in delivering humanitarian aid to Gaza, we start with the UK’s diplomatic engagement on humanitarian access.

Diplomatic engagement

3.4 FCDO recognised at an early stage that diplomatic efforts aimed at easing restrictions on humanitarian access needed to be its first humanitarian priority, working jointly with UN and bilateral partners. It has engaged bilaterally and in multilateral forums to encourage Israel to ease restrictions on humanitarian access. Over the longer term, its goals include a sustainable, permanent ceasefire, with a commitment to preventing further destruction, conflict and loss of life.

3.5 UK advocacy goals have evolved over the course of the conflict. Initially, in October and November 2023, the UK called for “humanitarian pauses”. Since late December, it has been advocating for “sustainable ceasefire and further humanitarian pauses”.

3.6 The UK has conducted its diplomacy at the most senior levels. The prime minister, foreign secretary, defence secretary and deputy foreign minister have all engaged directly with counterparts in Israel, the OPTs, and the region. There have been extensive discussions among G7 leaders, regional partners, and like-minded states to coordinate efforts to secure humanitarian access into Gaza. The foreign secretary appointed a humanitarian representative to the OPTs, Mark Bryson-Richardson, in December 2023. His role is to coordinate with regional countries, bilateral partners, the EU, and UN and Red Cross bodies. The US, the EU, Germany and the Netherlands have also appointed similar humanitarian representatives.

3.7 The UK has complemented its bilateral diplomacy with advocacy in the UN Security Council. As a permanent member of the Council, it has both supported and abstained from a number of proposed resolutions. On 9 December and 20 February, the UK abstained from proposed resolutions calling for a humanitarian ceasefire. However, it voted in favour of expanded humanitarian access on 22 December. Following a number of vetoes by other permanent members, on 25 March 2024 the Council finally adopted a resolution (with 14 affirmative votes and a US abstention) demanding an immediate ceasefire for the month of Ramadan, the immediate and unconditional release of hostages and an urgent increase in the flow of aid into Gaza.

3.8 As the conflict has progressed, the UK’s messaging has become both more public and more urgent. In recent weeks, the foreign secretary has expressed “enormous frustration” at UK aid for Gaza being “routinely” and “arbitrarily” held up pending Israeli permissions. He said: “words must turn into action. Because the alternative – mass starvation – is an abominable prospect to contemplate”. On 9 May, the foreign secretary also stated the UK’s focus “on securing a humanitarian pause, stopping the fighting right now, so we can see hostages released, more aid delivered, then turn this into a sustainable ceasefire without a return to fighting.” Among the stakeholders we interviewed, some suggested that the UK could have taken a harder diplomatic line at an earlier stage by characterising restrictions on humanitarian access as a violation of international humanitarian law. However, others took the view that there was little the UK could do in the circumstances beyond adding its voice to agreed international positions. All agreed that international pressure was yet to bring about any substantial change in levels of humanitarian access.

Humanitarian support

3.9 The UK’s additional £70 million for the OPTs has funded contributions to a range of humanitarian partners, including UNRWA, UNICEF, the World Food Programme (WFP), the World Health Organisation (WHO), the UN Office for Project Services (UNOPS), and UN OCHA. Partners were selected on the basis that they had operational capacity within Gaza, the ability to absorb additional funding, and robust risk management mechanisms.

Table 1: Summary of the £70 million allocation of UK humanitarian support

| Partner | £70m allocation (as of March 2024) |

|---|---|

| United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East (UNRWA) | £16.00m |

| United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF) | £11.33m |

| United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (UN OCHA) (Core) | £1.35m |

| United Nations office for Project Services (UNOPS) | £0.90m |

| World Food Programme (WPF) | £8.25m |

| World Health Organisation | £1.50m |

| British Red Cross (BRC), Palestinian Red Crescent Society (PRCS) and Egyptian Red Crescent Society (ERCS) | £2.75m |

| UK-Med - Emergency Medical Team | £2.75m |

| Core Relief Items (CRIs) | £4.80m |

| HSOT/Standby Partnerships (SBPs) | £1.01m |

| Ministry of Defence (MOD) logistical support/movement of CRIs including Lyme Bay | £0.53 |

| Jordan Hashemite Charity Organisation (JHCO) | £1.00m |

| Cross-government enabling support - UK Department of Health and Social Care (DHSC) | £0.02m |

| Qatar Fund for Development (provision of tents) | £0.11m |

| Other | £5.01m |

| Total | £70m |

3.10 The UK has also contributed to two multi-donor funds managed by UN OCHA, the Central Emergency Response Fund (CERF) and the Humanitarian Fund for the OPTs. These allocate funding to a range of partners, including UN agencies, international NGOs (including Save the Children and Medical Aid for Palestinians) and national organisations.

3.11 FCDO mobilised additional advisory expertise to support its response through its Humanitarian and Stabilisation Operations Team, a contractor-managed facility that provides the department with access to specialist expertise to respond to sudden-onset disasters and crises. It also funded secondments of experts to UN humanitarian partners through its Standby Partnerships mechanism. Among other things, these secondments helped UN OCHA to scale up its humanitarian coordination and information management.

3.12 The UK provided in-kind support – principally non-food items such as tents, blankets, and hygiene kits. While FCDO maintains central stocks of basic humanitarian supplies, specialist procurement was undertaken for the Gaza response to ensure that core relief items aligned with priorities and materials allowed into Gaza. Early deliveries of these items (Table 2) were carried out by the Royal Air Force (RAF) and the Royal Fleet Auxiliary (RFA) to Egypt for onward movement into Gaza by the Egyptian Red Crescent Society. Four RAF airlifts were used, the first being time-sensitive and including equipment such as forklifts, belt conveyors and lighting towers, to expand handling capacity. Commercial alternatives would have been feasible for the three additional flights.

3.13 The UK’s primary focus has been on securing land access for humanitarian aid, which all stakeholders agree is the most viable option for delivery at scale. For example, the UK supported WFP to establish a new humanitarian land corridor from Jordan, facilitating crossing into northern Gaza. Routes directly into the north have yet to be fully opened. Over 1,000 tonnes of food aid have been delivered via this corridor. The quantity of aid crossing into Gaza has shown a marginal improvement (see paragraph 2.9), but the total amount of food aid reaching northern Gaza remains wholly inadequate.

3.14 More controversially, the UK has carried out airdrops of humanitarian supplies into Gaza. In February, it organised an airdrop jointly with Jordan, including four tonnes of medicines, fuel and food for Tal AlHawa Hospital in northern Gaza. In March, the RAF supported a Jordanian-led international operation, which also included the US, Egypt, France, the Netherlands, Belgium, the United Arab Emirates (UAE), Spain and Singapore. As of 9 May 2024, the UK has participated in 12 airdrops, with the RAF involved in 11, delivering an average of 10 tonnes of food supplies per airdrop. The official development assistance eligible cost of the airdrops was estimated between a range of £230,000 and £315,000 for one aircraft.

3.15 Stakeholders were in agreement that airdrops were a last resort undertaken only in the face of the most desperate need. Airdrops pose significant danger to civilians, as confirmed by several reports of people killed by falling aid packages. They are also expensive and relatively untargeted, with supplies likely to be collected by the fittest individuals, to the detriment of vulnerable people, including women, children, the elderly and people with disabilities. Airdrops were seen as sending an important signal of support to the population of Gaza. However, they cannot be undertaken at anywhere near the scale required to relieve the growing famine.

3.16 The UK is also working with several partners, including the US, the European Commission, the UAE and Cyprus, to establish a maritime corridor for shipping aid to Gaza via Cyprus. The logistical challenges are substantial. Gaza has no deep-water port and the fishing harbour in Gaza City is too damaged to support offloading of humanitarian supplies. The US government has announced that it will assemble a pier, and the UK has pledged £9.7 million in aid-funded equipment and logistical expertise in support. Maritime delivery does not overcome the challenges of internal distribution in Gaza once materials are offloaded. Some stakeholders see it as an unhelpful distraction from the core priority of securing land access, while others have stated even stronger concerns that it might enable the closure of land crossings.

UK support by sector

3.17 Health sector: The IDF have targeted health facilities across Gaza, alleging that these are used by Hamas for military purposes. An interim damage assessment undertaken jointly by the EU, the World Bank and the UN found that, at the end of January 2024, 84% of health facilities had been destroyed, including Al Shifa, the largest hospital in northern Gaza. According to WHO, only 11 out of 36 Gaza hospitals continue to function, and then only partially, while 26 out of 89 other primary health care facilities continue to operate, with support from UNRWA and NGOs. There are 20 emergency medical teams (EMTs) south of Wadi Gaza. However, only one EMT has had access to the hospital in north Gaza, Kamal Adwan Hospital, due to the security situation. Five field hospitals have been established by external actors, of which four are functional and one is partially functional.

3.18 According to reports by the UN Health Cluster, the collapse of the health system, overcrowding in specific areas in Gaza and the drop in vaccination rates have led to outbreaks of communicable diseases, including acute respiratory illness, diarrhoea, scabies, lice and skin rashes. WHO estimates that 9,000 people need to be evacuated from Gaza for medical reasons, including 3,000 with chronic health conditions. Following the incursion into Rafah, the Health Cluster has warned that the capacity of the medical system to deal with non-emergency chronic health has all but collapsed. More than 1,000 children have lost one or more of their limbs, and UNICEF reports that thousands have acquired disabilities such as speech impairment or hearing loss. These conditions are exacerbated by poor air quality and inadequate water and hygiene. UNFPA reports “immense challenges with accessing adequate medical care”, a “surge in obstetric emergencies” and “higher rates of miscarriage, stillbirths, prematurity, [and] congenital abnormalities”. UNICEF has said that all children in Gaza require mental health support. Multiple health actors warn of severe long-term consequences from poor nutrition and inadequate health care for conflict victims, and of growing mental health and psychological consequences.

Table 2: UK humanitarian support for the health sector

| Partner | Total funds (as of March 2024) | Activities partially supported by UK funding and/or core relief items (CRIs) | Delivery modality of CRIs | Route taken for CRIs |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| UNRWA | £16m | - Medical supplies (with Cyprus) - 3.6 million patient consultations at health centres and points - MHPSS services with teams of psychiatrists in shelters and health centres - Psychosocial first aid, individual and group counselling, fatigue management sessions and recreational activities | RFA ship Lyme Bay to Egypt from Cyprus, to be delivered via land route | via Cyprus and Egypt |

| UK-MED | £2.75m | - Field hospital - Surgical and intensive care unit interventions in southern Gaza (25% of procedures on children) | Land route (was delayed by 6 weeks at border) | via Egypt |

| UNFPA | £4.25m | - Up to 100 community midwives - 20,000 menstrual hygiene kits and 45,000 clean delivery kits | Land route | via Egypt |

| Jordan Hashemite Charity Organisation | £1m | - 4 tonnes of medical supplies and essential medicines (including treatment for chronic diseases) - Food and fuel for field hospitals in northern Gaza and Khan Younis - Seed funding for mobile amputee units | Airdrop via Jordanian Air Force, and by truck convoy into Gaza | via Jordan |

| WHO | £1.5m | - Coordination of the whole EMT response - Provision of emergency assistive products, as well as critical medicines | ||

| Egyptian Red Crescent (British Red Cross) | - 74 tonnes of aid items including wound care packs | RAF flights to be delivered via land route | via Egypt | |

| UNICEF | £11.55m | - Psychosocial support services for children and caregivers - Supporting the Protection from Sexual Exploitation and Abuse (PSEA) Network hotline for MHPSS services |

3.19 Food and nutrition: The most recent food security assessment from March 2024 cites growing evidence of famine conditions in both the North Gaza and Gaza Governorates, with 1.1 million at risk of famine by July 2024. Access for food deliveries to the north remains severely restricted. WHO reports that, in northern Gaza, between 12% and 16% of children (aged 6 to 59 months) are suffering from acute malnutrition, and 3% from severe acute malnutrition. Interviewees spoke of the lasting effects of chronic malnutrition on child development.

3.20 In this context, the UK has supported key partners through flexible funding to support food security measures. As a last resort, the UK has also supported airdrops of food supplies and is working on alternative delivery modalities with partners.

| Partner | Total funds (as of March 2024) | Activities partially supported by UK funding and/or core relief items (CRIs) | Delivery of modality of CRIs | Route taken for CRIs |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| UNRWA | £16m | - Provided over 1.8 million people (85% of the population) with flour 87 - Provided nearly 600,000 people with emergency food parcels - Provides storage and distribution for other agencies’ food commodities | RFA ship Lyme Bay to Egypt from Cyprus, to be delivered via land route | via Cyprus and Egypt |

| UNICEF | £11.33 | - UNICEF trained UNRWA staff in shelters on monitoring for malnourishment through mid- and upper-arm circumference (MUAC) screenings, targeting children aged 6 to 59 months | ||

| WFP | £8.25 | - Provided 750 tonnes of food aid | Land route | via Jordan and Kerem Shalon |

| Royal Jordanian Airforce | £1m | - 10 airdrops carried out as of 30 April, with each dropping approximately 7 tonnes of food to the northern coastline of Gaza | Airdrop by RAF within Jordanian-led international aid mission | via Jordan |

3.21 Shelter and water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH): Almost the entire population of Gaza has been displaced, often multiple times. UNRWA reported on 7 April that up to 1.7 million IDPs were residing in or around 154 UNRWA shelters. (Multiple waves of displacement mean that some double counting is possible.) The majority of the population has fled to the south of Gaza, predominantly Rafah.

3.22 Water access in Gaza remains critically low, at only 48,000 cubic metres per day, compared to 255,000 cubic metres before 7 October. Water consumption has fallen to under 15 litres per person per day, below the recommended requirement for survival, whereas before 7 October this was around 84.6 litres per person per day on average in Gaza. Only one out of three water pipelines from Israel is operational, at just 47% of its full capacity, and desalination capacity has also been sharply reduced. Extensive damage to water wells, a lack of water testing and treatment facilities, and limited water trucking capacity exacerbate the situation. Lack of water compounds the dire humanitarian conditions, and has particular impacts on menstruating women and girls.

3.23 Infrastructure and systems for solid waste management have also been largely destroyed, with significant implications for disease. The Gaza Health Cluster reports that there is one latrine per 850 people in Gaza, compared to a minimum standard of 15, again with severe implications for public health and for safety. In response, the UK is prioritising the supply of core relief items into Gaza, including tents, blankets and water filters. Through its funding for UNICEF, it also provides emergency support for water supply and sanitation.

Table 4: UK humanitarian support for shelter and WASH

| Partner | Total funds (as of March 2024) | CRIs (if procured and donated) | Delivery modality of CRIs | Route taken for CRIs |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Egyptian Red Crescent (British Red Cross) | - 74 tonnes of aid items including water filters and solar-powered lights, tents, blankets and mattresses | RAF flights, to be delivered via land route | via Egypt | |

| Qatar Fund for Development | - 29 tonnes of tents | Qatari flight, to be delivered via land route | via Qatar and Egypt | |

| UNICEF | £11.55m | - Providing fuel for public and private water wells and desalination plants to produce clean water - Provided 5.9 km of water pipes to support repair and maintenance - Distributed hygiene kits - Fuel to operate one wastewater treatment plant in Rafah - Supported on solid waste and environmental hygiene in 22 non-UNRWA shelters | ||

| UNFPA | £4.25m | - 20,000 menstrual hygiene kits and 45,000 clean delivery kits | Land route | via Egypt |

| Palladium | £3m | - 6,000 family tents and 241 community tents | From Jordan, to be delivered via land route | flights from Pakistan and UAE to Jordan |

3.24 Gender-based violence and child protection: GBV, including physical and sexual violence, remains a daily threat to women and girls. With so many displaced and living in overcrowded conditions, lack of privacy increases vulnerability to GBV, harassment and abuse.95 Stakeholders raised concerns about the rise in children without surviving relatives and child-headed households.

3.25 The UK has supported the protection of women, children and vulnerable groups through UNRWA and UNICEF, and through UN Women via UN OCHA’s CERF. UNRWA supports victims of GBV and provides mental health and psychosocial support to children and young people, as well as education on risks around unexploded ordnance. The UN Women project supports gender-responsive and inclusive community feedback mechanisms. UNICEF focuses on child protection through the distribution of core relief items, psychosocial support and care for unaccompanied children.

4. Risk management

4.1 FCDO acknowledges that its humanitarian response in Gaza is being delivered in an extremely challenging and volatile environment, and one which is also politically sensitive. It notes the need to apply a rigorous approach to risk management, while stressing that risk management processes are not intended to prevent the delivery of life-saving assistance. Risks include potential harm to both aid workers and Gaza citizens, and the theft or diversion of humanitarian aid supplies, including by Hamas.

4.2 FCDO sets its risk management appetite for each country where it operates, covering a range of risk categories. This determines the level of risk that can be taken by programme management teams, and which risks need to be escalated to higher management levels for approval. Conditions in Gaza, coupled with very limited capacity for oversight and monitoring, mean that FCDO has no alternative other than to tolerate a high level of risk. It is therefore in the process of formally increasing its risk appetite.

4.3 However, the residual risks still need to be carefully managed. FCDO’s risk-management process begins with ensuring that its implementing partners have adequate risk management policies and processes in place, that meet UK standards. When scaling up an emergency humanitarian response, the need to conduct due diligence assessments of multiple new partners places a substantial burden on FCDO staff. To help manage the process, FCDO has prioritised working with partners with proven capacity to monitor and manage risk while delivering in emergency contexts. In the case of UNRWA, UN OCHA and UNICEF, due diligence assessments had already been undertaken for existing funding agreements. New assessments have been undertaken for a number of new partners since October.

4.4 There are significant risks around the diversion of humanitarian aid in Gaza, given the breakdown in public security. People in Gaza have reported that “diversion and corruption has interfered with the ethical distribution of aid”. Media reports state that a “shadowy war economy” has emerged, and that criminal gangs “regularly rob unprotected aid convoys, selling what they steal to desperate Gazans”. There has also been ‘self-distribution’ of supplies from humanitarian convoys by crowds, which FCDO and experts suggest is likely to be spontaneous rather than organised. Until a planned third party monitoring system is in place, FCDO is dependent on reporting of aid reaching affected populations by partners, and some level of aid diversion is a risk that FCDO has to tolerate in order to reach people in need. FCDO and its UN partners judge that increasing the supply of humanitarian goods into Gaza is the best way of limiting diversion in the short term, as the extreme scarcity of food and other supplies increases their value on the black market. At the time of writing, there were reports of attacks on convoys and relief goods destroyed en route to Gaza by Israeli protesters. The foreign secretary called the attacks “appalling” and he will be raising “concerns with the Israeli government”.

4.5 There is a further risk that humanitarian supplies end up benefiting Hamas, which is a proscribed organisation under UK counter-terrorism legislation. The legislation prohibits certain payments to or dealings with proscribed organisations. However, a ‘general licence’ is in place for Israel and the OPTs that exempts humanitarian assistance. The UK has established a Tri-Sector Group that brings together representatives from government, financial institutions and civil society organisations to ensure that humanitarian assistance is able to continue without violating counter-terrorism and sanctions legislation.

4.6 The Israeli government has called into question the independence of UNRWA, alleging that several UNRWA employees participated in the 7 October 2023 attacks and that UNRWA as a whole has deep institutional ties with Hamas. On 27 January 2024, the UK announced a suspension of funding for 2024.

4.7 The Colonna report was published on 22 April and is limited to UNRWA’s mechanisms and procedures in respect to neutrality, not to any role of UNRWA staff in the October attacks, which is the focus of the pending OIOS report. The report broadly found UNRWA’s procedures to be “sound”, but presented some concerns, including “instances of staff publicly expressing political views, host-country textbooks with problematic content being used in some UNRWA schools, and politicised staff unions making threats against UNRWA management and causing operational disruptions”, along with a set of recommendations which have been accepted in full by the UN Secretary-General. The report also restated the essential role played by UNRWA in providing basic services and humanitarian support to the Palestinian population (see Box 1).

5. Suggested further lines of enquiry

5.1 We conclude by suggesting a number of issues that would merit further investigation, by ICAI itself, the IDC or other scrutiny bodies.

- International humanitarian law: What are the circumstances in which the UK would state publicly its assessment as to whether Israel has violated international humanitarian law, and what would be the consequences of such an assessment?

- Support for UNRWA: Given the critical role of UNRWA, what are the UK’s plans in relation to further funding?

- Humanitarian access: What is the UK’s strategy for restoring adequate supplies of food and essential goods into Gaza and ensuring sustainable humanitarian access? Should the UK continue to support the development of a maritime corridor?

- Human costs: What preparations is the UK making to respond to the long-term harms suffered by the population of Gaza, including war-related physical and mental injuries and the effects of gender-based violence?

- Monitoring and transparency: What action is the UK taking to ensure that adequate monitoring arrangements are put in place for its Gaza operations, and that there is space for journalism and other independent scrutiny?

- Reconstruction of Gaza: What advance planning is FCDO undertaking, with international partners, for the recovery and reconstruction of Gaza?