The UK’s Preventing Sexual Violence in Conflict Initiative – Joint Review

Purpose, scope and rationale

Knowing the devastating impact of sexual violence in conflict (SVIC) and the complex nature of this issue, the UK government established the Preventing Sexual Violence in Conflict Initiative (PSVI) in 2012 to respond to the needs of survivors and galvanise support for an international campaign to reduce and prevent SVIC. The creation of the initiative was followed by the 2014 Global Summit on Sexual Violence in Conflict (Global Summit), which gathered a broad range of representatives from government, international organisations and experts from civil society.

As a cross-departmental initiative, the PSVI is led by the Foreign Office (FCO), with contributions from the Department for International Development (DFID), the Ministry of Defence (MOD) and the Home Office. The PSVI is one instrument used by the UK to address SVIC. Others include projects led by FCO embassies in countries and some relevant initiatives led by the MOD or DFID. The funding sources for these initiatives are complex and include various funds like the Conflict, Stability and Security Fund (CSSF) and the Rules Based International System fund.

The UK government addresses the issue of sexual exploitation and abuse (SEA) perpetrated by peacekeeping forces and civilian staff working in conflict zones through a different set of teams and policies. This is done mainly through advocacy and programming led by the Gender Equality Unit at the FCO and via support for UN efforts to root out abuses during UN peacekeeping operations. The UK government supports staff working on SEA at the UN Secretariat, such as the Special Coordinator on Improving the UN Response to Sexual Exploitation and Abuse, the Victims’ Rights Advocate, the Conduct and Discipline Section of the Department for Management Strategy, Policy and Compliance, and the UK Mission to the UN.

Scope of the joint review

The purpose of this joint review is twofold. First, we will explore how well the UK government has delivered on the promise of the PSVI initiative and what progress has been made towards its commitments to reduce stigma for survivors, increase justice and accountability, and increase preventative efforts since the 2014 Global Summit.

Second, this review also offers the opportunity to assess in parallel the ways in which the UK government has been active in addressing the challenge of violations committed by international peacekeepers, police and civilian staff.

This joint review will therefore limit its focus on sexual violence to particular sets of circumstances and characteristics. These are:

- Context: violations that take place in a conflict zone.

- Perpetrators: in Part 1 (our review of the PSVI), violations which are perpetrated by military forces, police, non-state armed combatants, or civilian staff of any of the aforementioned. In Part 2 (our review of SEA), violations which are perpetrated by international peacekeeping soldiers and civilian staff linked to peacekeeping operations.

- Goal: the motivations for the violations range from (i) opportunity-led, facilitated by the lawlessness and impunity prevalent in conflict zones, (ii) targeted at a community/person as a weapon of war, often with a political goal, or (iii) used as a unifying mechanism to connect units which are engaged in the pursuit of a common goal (political or otherwise).

- Survivors: violations that are targeted at female, male or otherwise gendered survivors, and include children.

The review will assess the relevance and effectiveness of the UK government’s response following the 2014 Global Summit. This includes reviewing the extent to which the response is evidence-based and whether lessons have been captured to inform future programming. The review will also examine how well DFID, the FCO and the MOD have collaborated across and within institutions, and the degree to which programming took into account the voices of survivors.

ICAI is conducting a joint review of the UK aid response to SVIC and SEA. Two related reports represent the final output of this review, the first focusing on SVIC perpetrated by military forces and combatants, and the second centred on SEA by UN and other international peacekeepers, police, and civilian staff of the aforementioned organisations.

Background

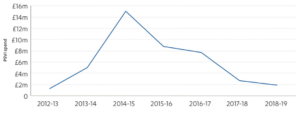

The PSVI was founded in 2012 by Lord William Hague and UNHCR Special Envoy Angelina Jolie. Total expenditure in 2012-13 reached £1.3 million, the majority of which was allocated towards supporting the UN Trust Fund for Victims and the UN Team of Experts (£500,000 each). During the 2013-14 fiscal year, PSVI expenditure increased to £5 million, which included continued support for the International Criminal Court’s Trust Fund for Victims and team of experts, but which was also used to fund programmes within the African Union (£800,000) and various country-specific prevention programmes, some of which engaged faith leaders, and survivor support programming, including judicial capacity building.

Between the Global Summit and 2019, the London PSVI team spent just over £34 million, with a peak in 2014- 15. For the fiscal year 2018-19, the PSVI London team spent less than £2 million, the majority of which went to the UN. There were only a handful of projects at country level, amounting to less than £300,000 in total. The figure below does not include spending at country office level on addressing SVIC, as data is limited at this stage in the review. Moreover, DFID’s integrated programme model, which runs most SVIC programming through violence against women and girls (VAWG) interventions means that disaggregation of PSVI spending is not always possible.

Figure 1: Preventing sexual violence in conflict initiative spend per year (centrally-managed)

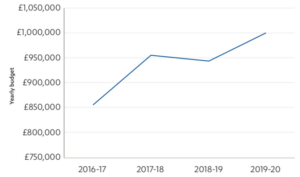

Figure 2: Annual government expenditure on sexual exploitation and abuse programming

Spending on activities to prevent and respond to SEA by peacekeepers and civilian staff seems to have been mostly after 2016, and mostly funded through the CSSF (which was established in 2015). Since 2016-17, the UK has spent £3.7 million on activities to prevent and address SEA, funded through the multilateral strand of the CSSF.

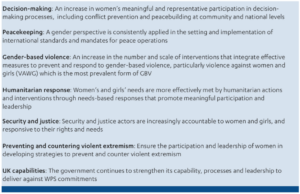

The UK government’s portfolio addressing SVIC and SEA ranges from judicial and accountability work to prevention and advocacy initiatives. These activities sit within the policy context of eight UN Security Council resolutions (UNSCRs) on women, peace and security. This includes UNSCR 1325, adopted unanimously in 2000, which outlines four pillars for this work: prevention, participation, protection, and relief and recovery. The 2018-22 UK National Action Plan on Women, Peace and Security represents the government’s highest-level strategy on gender and conflict, with seven strategic outcomes and nine priority countries – Afghanistan, Burma, the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), Iraq, Libya, Nigeria, Somalia, South Sudan and Syria. The third and fifth strategic outcomes (SO3 and SO5) are particularly central to this review. SO3 commits to an increase in interventions to prevent and respond to gender-based violence, while SO5 aims to ensure that the security and justice sectors are increasingly accountable to women and girls. Six of the nine priority countries set out in the National Action Plan can be found among the top ten locations for UK spending on PSVI activities (see box 1).

Box 1: Outcomes of the UK national action plan on women, peace and security

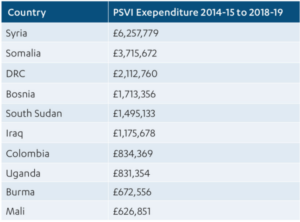

Figure 4: Preventing sexual violence in conflict initiative expenditure 2014-15 to 2018-19

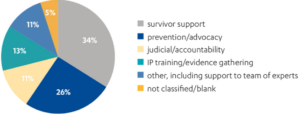

Figure 5: Preventing sexual violence in conflict initiative spend by sexual violence in conflict activity area

Review questions

This review is built around the criteria of relevance, effectiveness and learning.14 The review will also assess cross-government coordination mechanisms and the extent to which survivor needs, wants, and feedback were integrated into programme design and adaptation. The review will assess UK’s commitments and efforts to tackle sexual violence in conflict and sexual abuse and exploitation during peacekeeping missions according to the following criteria and questions:

Table 1: Sexual violence in conflict review questions

| Review criteria | Review questions |

|---|---|

| Relevance | • Does the portfolio demonstrate a credible approach to preventing sexual violence in conflict and meeting the needs of survivors, as well as meeting the objectives and pledges set out at the 2014 summit? • What evidence, if any, is there that survivor needs, wants and feedback were explicitly sought and integrated into programming? |

| Effectiveness | • How well have the programmes delivered on their objectives as well as the overall objectives of the PSVI? • To what extent have DFID, FCO, and MOD collaborated across and within institutions? |

| Learning | • How have responsible departments generated and applied evidence on what works on sexual violence in conflict? |

Table 2: Sexual exploitation and abuse review questions

| Review criteria | Review questions |

|---|---|

| Relevance | • Does the UK have a well considered approach to tackling sexual exploitation and abuse by international peacekeepers? • What evidence, if any, is there that survivor needs, wants and feedback were explicitly sought and integrated into programming? |

| Effectiveness | • How well have programmes aimed at tackling sexual exploitation and abuse by international peacekeepers delviered on their objectives? • To what extent have DFID, FCO, and MOD collaborated across and within institutions? |

| Learning | • How have responsible departments south to learn from, and apply learning to, programming on sexual exploitation and abuse by international peacekeepers? |

Methodology

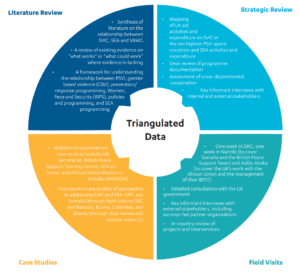

The methodology for the review will involve four main components, each used to inform and triangulate findings in the others. The methodology includes a field component, but given the security constraints inherent to a review of conflict-related programming, the review will make extensive use of DFID and FCO programme data and remote data gathering. The review will draw on expert and stakeholder opinion, including that of survivors, and a robust literature review.

Component 1 – Literature review: A review of literature on the context and evolution of SVIC and SEA by peacekeepers to support the assessment of the relevance and effectiveness of UK aid in this area. A detailed review of evidence from the literature to determine what works, or what could work where evidence is lacking. The literature will situate the rest of the review within the global context of SVIC and SEA programming, and enable the identification of possible explanations for claimed results. Furthermore, it will enable assessment of the relevance and adequacy of the UK government’s investments in research, reporting, data collection and learning. The review will cover published and unpublished academic and official literature and commentary, including appraisals by DFID and other development actors of what works and lessons learned for programming.

Component 2 – Strategic review: To assess the relevance of UK aid investments, we will first review the response of participating departments (DFID, the FCO and the MOD) to the commitments made during the 2014 Global Summit and outlined in the National Action Plan. This will involve a desk-based mapping exercise of relevant strategies, priorities and programmes led by London- and country-based teams, as well as an analysis of expenditure, for the ten countries with the highest spend on PSVI (see sampling strategy below). This will include the identification and rapid analysis of SVIC and SEA projects as well as of programmes with primary objectives in other areas (such as livelihoods or food security), but with potential indirect impact on SVIC and SEA. The rapid analysis of projects will focus on a limited range of indicators, such as spend or the existence of a theory of change, to build a high-level overview of the portfolio. We will cover centrally managed programmes, research and influencing work, as well as relevant programming in priority countries, funded through bilateral and multilateral channels. This strategic review will be based on a desk review of key strategic, funding and programme documents at London level and for the ten countries with the highest PSVI spend. It will be complemented by key informant interviews in London. The strategic review will explore coherence and collaboration across the UK government, including mapping coordination processes.

Figure 6: Our methodology approach

Component 3 – Case Studies: Five country case studies and one case study of multilateral organisations will be conducted, which will encompass document review and in-person interviews with SEA staff in New York, Addis Ababa and Nairobi. The purpose will be to explore in greater depth the relevance and efficacy of the UK government’s efforts (and associated funding) to address SVIC and SEA. These case studies also offer the opportunity to gather external perspectives on the added value of UK aid tackling SVIC and SEA in communities where these interventions should have the greatest impact. Given the scattered nature of interventions and their limited size and scope, country-level rather than programme-level analysis is preferred. Each case study is intended to assess (1) the diversity of interventions, (2) the link between commitments, pledges, actual expenditure and objectives in London and in post, (3) the extent to which there is a shared theory of change, (4) the relevance and effectiveness of programmes for specific contexts and survivor needs, (5) the generation and application of learning, and (6) the effectiveness of cross-department coordination. Case studies will involve at least a review of key country and programme documents and remote interviews with gender and conflict experts in post and senior responsible officers for programmes. In three country cases – DRC, Somalia, and Bosnia – we will complement the desk research with in-person interviews and consultations in these countries or neighbouring countries. This will be done through field visits to DRC and East Africa (see below) and with the support of a local researcher in Bosnia.

Component 4 – Field visits: A one-week field visit to DRC will be followed by a one-week field visit to Nairobi and Addis Ababa. This will enable assessment of a breadth and depth of SVIC and SEA programming. DRC represents an ideal location as both SVIC and SEA programming can be reviewed. The country visit will enable the review team to triangulate and deepen the analysis in the strategic review and case studies through key informant interviews with DFID and FCO staff and consultations with national officials, implementing partners and, when possible, survivor-led organisations. The regional trip to Nairobi and Addis Ababa will allow the review team to cover two aspects of the review:

- Through key informant interviews with FCO and DFID staff working on Somalia in Nairobi, as well as their key partners working on SVIC, and, if possible, consultations with survivor-led organisations, the team will deepen their analysis for the Somalia case study.

- The review team also intends to assess activities related to SVIC and SEA through consultations with and via an in-person review of the African Union peacekeeping efforts, British Peace Support Training Centre and African Union Mission to Somalia. These consultations will inform the multilateral organisations case study, which will also include interviews with staff at the UN Secretariat in New York.

Sampling approach

Two components required sampling and selection for this review: the strategic review and the case studies. As such, the following sampling approach was used:

- First, all ten countries with the highest PSVI spend: Syria, Somalia, DRC, Bosnia, South Sudan, Iraq, Colombia, Mali, Uganda and Burma were selected for the strategic-level sample. This sample covers 84% (approximately £20 million) of the total country-level PSVI expenditure over the period of review (£23.9 million from 2014 onwards). This high-level sample will allow examination of alignment with UK priorities and overall theory of change, evolution of spend and spread of activities.

- Second, we assess the relevance, effectiveness and learning of UK aid on SVIC and SEA at country level, through in-depth case studies. These case studies were selected from the sample of ten countries with the highest spend on SVIC. The review team then applied a series of additional selection criteria: a) relevance of the country in the global picture of SVIC and SEA, b) breadth and diversity of SVIC and SEA programming, c) evidence of existing programming in post, d) diversity of conflict contexts. We excluded countries that were recently reviewed by ICAI to avoid overburdening the UK efforts in these crisis contexts (Syria and South Sudan). Based on these criteria, the case study sample includes DRC, Somalia, Bosnia, Colombia and Burma. With this sampling, we will cover over a third of country-level PSVI funding from 2014 to present (38%) and all strands of PSVI interventions (accountability and justice, survivor support and prevention).

- We finally identified criteria for selecting which countries to visit, in particular the ability to cover both components of our review (SVIC and SEA) in country, to review different peacekeeping forces (UN Department of Peacekeeping, African Union, AMISOM, UN Organisation Stabilisation Mission in the DRC), and to review some of the MOD-led work in country (Kenya and Ethiopia).

Limitations of the methodology

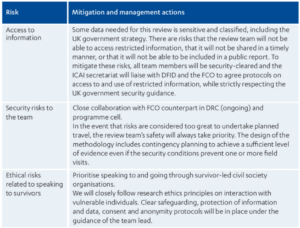

We anticipate the following methodological challenges:

- Lack of comprehensive data on PSVI funding: Beyond the PSVI funding managed by the PSVI team in London, FCO posts fund their own PSVI-related programmes across the FCO networks. There is no reporting mechanism to the London PSVI team on these post-led projects, which will make the mapping of the entire portfolio of interventions challenging. We also anticipate that, in some cases, it might be difficult to find information for interventions implemented during the first years of our period of review, given the high turnover of staff in post. We have therefore added a mapping component to our methodology, focusing on the ten countries with the highest PSVI spend, to collect as much data and information as possible from post directly.

- Varying categorisations: DFID contributes to the delivery of PSVI through related programmes, for example through its work to tackle violence against women and girls (VAWG) in conflict and humanitarian settings. DFID’s portfolio is not organised or categorised around the concept of SVIC but focuses on wider VAWG programmes. Accurately mapping DFID’s contribution will therefore be challenging. The review team is liaising with the DFID VAWG team to best identify and assess DFID’s contribution to PSVI.

- Differences in the existing evidence base: The literature review highlighted important differences in the existing evidence base on what works across the three strands of PSVI interventions, with much less evidence available on what works in SVIC prevention and stigma reduction as opposed to greater evidence on what works in the field of justice and accountability for survivors. The review team will need to take into account these differences when examining the projects and use different ‘standards’.

Risk managment

Quality assurance

The review will be carried out under the guidance of ICAI lead commissioner Tamsyn Barton, with support from the ICAI secretariat. The review will be subject to quality assurance by the service provider consortium. Both the methodology and the final report will be peer-reviewed by Dr Joana Cook, senior research fellow at the International Centre for the Study of Radicalisation. Dr Cook is an academic expert on violent extremism and sexual violence in Yemen and the wider Middle East and North Africa region. She has published extensively on women, peace and security and sexual violence, especially in relation to violent extremism.

Timing and deliverables

Subject to measures needed to mitigate the risks outlined above, the study will be executed within nine months starting from March 2019.