Assessing DFID’s Results in Water, Sanitation and Hygiene

ICAI score

The Department for International Development (DFID) reported that it reached

62.9 million people with water, sanitation or hygiene (WASH) support between 2011 and 2015, exceeding its target of 60 million. This results claim is based on credible data calculated using appropriate methods and conservative assumptions. It amounts to a significant contribution to extending global WASH access. While there is some evidence of wider development impact, DFID does not routinely collect impact data. Better data would enable it to maximise impact, particularly for vulnerable groups. DFID does not have a systematic approach to achieving sustainability and does not monitor whether results are sustained beyond programme completion. We found encouraging evidence of learning in a range of areas. In the absence of consistent data, it was not possible to reach an overall conclusion on the value for money of the portfolio.

Executive Summary

Over the 2011 to 2015 period, the UK government set itself the goal of providing 60 million people with clean water, improved sanitation or hygiene promotion interventions (a type of development assistance known collectively as WASH). In 2015 it reported that it had exceeded this target, reaching 62.9 million people.

Improving access to WASH is both a development goal in its own right and a means of achieving other development benefits, particularly in health. WASH is also thought to contribute to school attendance, nutrition and gender equality. DFID spent around £180 million on WASH through bilateral programming in 2014.

We conducted an impact review of DFID’s WASH portfolio to identify whether its results claims were credible, and to explore whether programmes were doing all they could to maximise impact and value for money.

Is the results claim credible?

DFID claims to have provided 62.9 million people with access to WASH over the 2011 to 2015 period, exceeding its target by 2.9 million. We subjected this claim to a series of checks to determine its credibility.

We found that the total figure was calculated using appropriate methods and conservative assumptions. In the programmes we examined in detail, DFID and its implementers were able to produce the source data used to generate the results, including at individual project sites.

The results claim was based on population-based assumptions about WASH access that are widely used by agencies in the sector. This is not the same as reporting actual usage, data for which has been very costly to collect up until now. This limitation aside, the 62.9 million is a valid indication of the UK’s contribution to extending WASH access.

As the fifth largest funder (including the World Bank) in the WASH sector in 2014, and the largest donor for basic WASH services in low-income countries, DFID’s WASH results represent a substantial contribution to improving WASH access for poor and vulnerable communities in priority countries.

What has been the impact of DFID’s WASH support?

In isolation, the reach figure says nothing about the changes in human wellbeing associated with WASH access, ie the impact on people’s lives. We have some evidence of impact from individual programme evaluations.

These suggest that DFID WASH investments have led to improved health outcomes, particularly reductions in infant diarrhoea (a major cause of infant sickness and death in developing countries), parasitic worms and other infectious diseases. There have also been improvements in school attendance, and there is some evidence of reduced gender inequality from reductions in the time that women spend fetching water.

However, impact data is not being routinely collected. While such results may be occurring across the portfolio, we cannot reach conclusions as to where and to what extent. This in turn makes it difficult to conclude that DFID is doing all it can to maximise impact.

Collecting impact data, even on a sample basis, would enable DFID to adjust its programmes in real time, so as to maximise results. It would also make DFID better placed to target its investment towards the most vulnerable individuals within communities, such as women and girls, the elderly and people with disabilities. The ability to target investments towards the most vulnerable will become more important in the light of the Global Goals commitment to ‘leaving no one behind’.

How sustainable are DFID’s WASH results?

Sustainability is a particular challenge in the WASH sector. It has multiple dimensions, including technical, financial and institutional. Achieving lasting change in sanitation and hygiene practices calls for intensive engagement with beneficiary communities over an extended period.

We found that DFID does not approach the sustainability challenge in a systematic way. While many of its programmes include investments in building national systems, this is not being done consistently. The typical three to five years’ duration of DFID’s WASH programmes is often too short to put in place the conditions for sustainable impact. Furthermore, DFID does not monitor whether results are sustained beyond the life of its programmes. This is an area where DFID has fallen behind some other donors in the WASH sector. For example, the Dutch Development Agency and USAID now use sustainability checks for up to ten years after programme completion.

We therefore conclude that DFID’s systems are designed to maximise outputs, rather than sustainable impact. This situation has changed little since a National Audit Office (NAO) review in 2003.1

Is DFID achieving value for money?

Value for money in aid programmes means getting to the desired results, taking into account quality and sustainability, at the lowest cost. DFID does not apply a consistent approach for measuring value for money across its WASH portfolio, nor does it have credible benchmarks to help it to identify more or less efficient programmes. However, we saw specific examples where DFID had successfully improved value for money at the programme level.

As a result we are not able to draw conclusions about the overall value for money of the WASH portfolio. DFID recognises these challenges and is funding ongoing research on both value for money and sustainability.

The majority of DFID’s WASH results come from programmes implemented by Unicef which, as a multilateral partner, is not subject to competitive tendering. While acknowledging that engaging with multilateral partners is different to working directly with non-governmental organisations (NGOs) and commercial providers, we believe there may be benefits to subjecting these programmes to a market test.

Is DFID learning from experience?

We found good evidence of learning in a number of areas. At the central level, DFID is a significant investor in WASH research and in improving data quality. At the programme level, lessons are captured through annual reviews and we saw good examples of programmes being adapted in response to lessons learned.

We saw less evidence of lessons being shared effectively across the department. DFID lacks strong mechanisms for collating and synthesising lessons from its programmes and making them available to inform future investments. There could also be more shared learning between WASH and related areas such as health and education.

Scoring and recommendations

We conclude that the performance of DFID’s WASH portfolio warrants a Green-Amber rating. DFID has successfully achieved its WASH target and has made a substantial contribution to extending WASH access in low-income countries. However, it is not doing all it could to maximise impact or sustainability and the score reflects weaknesses in these areas.

We make four broad recommendations, each of which is supported by a number of issues of concern that we would like DFID to address. The lack of attention to sustainability is an area of particular concern, requiring remedial action from DFID.

Recommendation 1

DFID should improve the measurement and reporting of the development impact of its WASH programmes, particularly for vulnerable groups.

- DFID does not systematically monitor the impact of its programming on priority groups.

- DFID does not regularly collect data on the wider development impact of its WASH interventions.

- DFID does not have sufficient data to assess whether its WASH programming overall is having the desired development impact.

Recommendation 2

DFID should embed sustainability in its WASH programming and measure how well this is implemented.

- DFID is currently measuring and reporting initial, not sustained, access.

- DFID has no systematic evidence to demonstrate whether its WASH results are in fact being sustained after its funding ends.

- The attention given to institutional and financial dimensions of sustainability varies from programme to programme.

- The typical three to five year duration of DFID’s WASH programmes is often too short to ensure sustainability.

Recommendation 3

DFID should act quickly on the results of its value for money research to develop a suitable framework for measuring value and guiding programming choices.

- DFID is currently unable to compare the return on its investment across WASH programmes.

- DFID may need additional methods for assessing whether Unicef represents value for money compared to alternative delivery options, including NGOs and commercial providers.

- DFID’s move towards the use of results-based contracting in WASH is potentially a positive step, but needs to be done carefully in order to create the right incentives for suppliers to focus on sustainable results.

Recommendation 4

DFID should improve how learning on WASH (including from its research programmes) is shared throughout the organisation.

- DFID does not systematically capture and disseminate lessons from its own programmes generated by annual reports and programme completion reports.

- Lessons from DFID funded research on WASH need to be fully reflected in project design and monitoring documentation.

- DFID could invest more in knowledge exchange between WASH and related sectors such as health and education.

Introduction

Purpose and scope of the review

In the period from 2011 to 2015, DFID committed to provide 60 million people in developing countries with at least one water, sanitation or hygiene promotion intervention (a type of aid known collectively as WASH).2 This was one of a number of global targets that the UK government set itself, alongside targets in areas such as health, education and nutrition. In 2015, after investing almost £700 million over the previous 5 years on WASH programmes in 27 countries, DFID announced that it had exceeded this target, reaching 62.9 million people.3 How accurate is this claim, and how much impact has DFID’s WASH programming really had on its intended beneficiaries?

To gain a better understanding of this result, we carried out an impact review of DFID’s WASH portfolio. ICAI impact reviews focus on the results claimed by DFID (or other government departments as appropriate), as outlined in Box 1. WASH was a suitable topic for an impact review because it is a mature portfolio where DFID has made a global results claim and where there is a range of results data available.

ICAI impact reviews examine results claims made for UK aid to assess their credibility and their significance for the intended beneficiaries. We examine the quality of results data generated by aid programmes and whether the data is being used to improve results over time. We also assess value for money – that is, whether DFID or other spending departments are maximising the return on UK aid invested. ICAI impact reviews use the results data that is already available, triangulated with other sources. We do not carry out our own independent impact assessments.

Other types of ICAI review include performance reviews, which probe how efficiently and effectively UK aid is delivered, and learning reviews, which explore how knowledge is generated in novel areas and translated into credible programming.

While impact reviews are primarily retrospective in orientation, assessing results over a particular period, we note that DFID has committed itself to providing WASH access to a further 60 million people between 2015 and 2020. We therefore also take this opportunity to reflect on some of the challenges that DFID will face in the coming period.

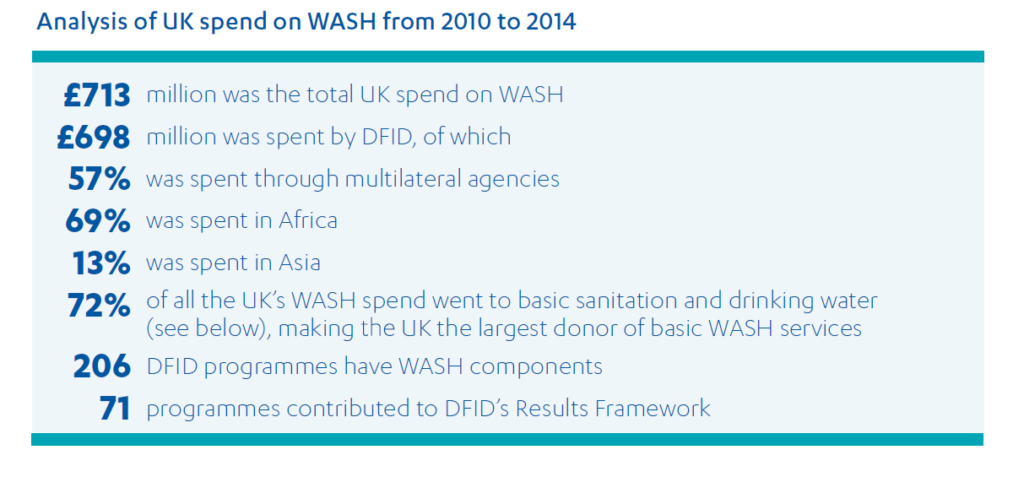

Our review examined the WASH results reported under DFID’s Results Framework 2011 to 2015. These were generated from 71 bilateral projects and from contributions to a number of multilateral organisations. We assessed the processes by which DFID captures results at the programme level and compiles these into a global result. We examined how DFID ensures that its results are sustainable – a particular challenge in WASH programmes – and how it assesses whether it is achieving value for money.

Our review questions:

| Review criteria and questions | Sub-questions |

|---|---|

| 1. Impact: what has been the impact of DFID’s WASH programming in the 2011 to 2015 Results Framework period? | • What level of results has been achieved through DFID’s WASH portfolio? • Have DFID’s WASH investments been targeted effectively to the poorest and most marginalised communities and individuals? • What has been the variation in impact across programmes, countries and delivery channels? What does this tell us about value for money and return on investment? |

| 2. Results measurement: are the aggregate WASH results reported under DFID’s Results Framework based on credible evidence? | • How credible are the processes that DFID uses to collate, review and validate evidence on results? • To what extent have WASH interventions been strengthened in response to lessons learned on delivering results? |

| 3. Sustainability: has the impact from DFID’s WASH programming proved sustainable? | • Have DFID’s WASH interventions been designed and implemented with a view to maximising the sustainability of results? • Are appropriate arrangements in place to monitor the sustainability of results after the end of the funding period? |

WASH is both a development goal in its own right and a means of achieving other goals

WASH was part of the international development agenda under the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) from 2000 to 2015, and remains part of the Global Goals, from 2015 to 2030. Improving WASH access is both a development goal in its own right, contributing directly to quality of life, and an important means of achieving other development outcomes. With poor access to WASH, people suffer from more health problems and worse nutrition. In many countries, poor households waste many hours a week collecting water, holding back their productive capacity and incomes. WASH is also important to gender equality. It is often women and girls who bear most of the burden of collecting water. During our field visits for this review, we met women who spent as many as five hours a day fetching water.

There is strong evidence linking WASH to health. Young children are the most prone to WASH-related diseases, particularly acute diarrhoea. Clean and treated water can save lives by reducing the incidence of respiratory and intestinal infections and other diseases. Beyond health, the other benefits of WASH are not as well studied. It is widely believed that WASH improves school attendance – for example, studies have shown that children infected with intestinal worms may miss twice as many school days as other children,4 and lack of sanitation facilities in schools is considered a barrier to girls’ attendance. Women and girls are vulnerable to gender-based violence while collecting water, although the full extent of this problem remains unknown.

Uneven progress on global WASH targets

The global MDGs target on clean water access was achieved in 2010, with an additional 2.6 billion people gaining access to improved drinking water since 1990. However, progress has been uneven across regions – Sub-Saharan Africa missed the drinking water target – while globally 663 million people are still without access, mostly in rural areas.5 Progress towards the sanitation target lags much further behind: against an MDG target of 77%, only 68% access was achieved, leaving 2.4 billion people worldwide living without improved sanitation and almost one billion people having to defecate in the open.

The MDGs set out to halve the proportion of the global population without access to WASH. The 2015 Global Goals are more ambitious still: “to achieve, by 2030, universal and equitable access to safe and affordable drinking water for all”.6 The updated definition of ‘access’ is also more challenging, including a requirement that clean water must be available within a 30-minute round trip. Applying such a criterion to DFID’s 2010-2015 WASH target is likely to have reduced the reported results, although by how much is not known. There are also specific goals on sanitation, hygiene and ending open defecation, as well as on the provision of WASH facilities in schools.

DFID has adopted ambitious targets for a growing WASH portfolio

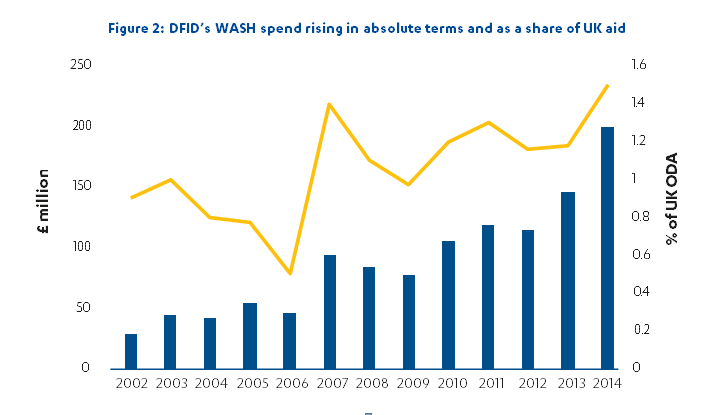

DFID has made a significant commitment to promoting global WASH goals. Its expenditure on WASH has increased rapidly since making new commitments in 2005, reaching £181 million in 2014, or around 1.6% of all UK aid. Internationally, DFID is the fifth largest funder (including the World Bank) in the WASH sector, but it is the leading donor by expenditure on basic WASH provision in low-income countries, where DFID has concentrated most of its investment.7

DFID has set itself ambitious results targets for WASH. Its initial commitment in 2010 to provide 15 million people with first-time access to WASH was doubled and then redoubled, to a target of reaching 60 million people over the 2011-2015 period. In 2015, DFID committed itself to reaching a further 60 million people with sustainable access to safe drinking water or sanitation by 2020.8

The portfolio includes a range of activities and delivery channels

There are 71 programmes contributing results to the 2011-15 target (see Box 3). Most are bilateral projects run out of a DFID country office. However, there are also several centrally managed programmes, often working in parallel with country-based programmes. The UK’s core contributions to multilateral agencies also add to the WASH results total, with the World Bank being the largest of these.

Among bilateral programmes, various delivery channels are used, including multilateral agencies, contractors, NGOs, partner governments and multi-donor trust funds. According to DFID, 60% of its total WASH results are delivered by Unicef, primarily funded out of the bilateral programme.

Over the period 2011-2015, the UK government set a series of targets and commitments for the UK aid programme – including a commitment to provide 60 million people with WASH access. Progress towards these targets was captured through DFID’s Results Framework – a matrix of indicators, each with an associated methodology for collecting and aggregating results across a portfolio of programmes. A central objective of this review is to test the credibility of the Results Framework results in WASH.

The Results Framework was a significant innovation for DFID, giving the department the capacity to report on its results at a global level for the first time. It was seen as an important tool for communicating to the public in simple terms what the aid programme was delivering. However, it could only capture results that could reliably be counted and added up across different programmes and country contexts. For that reason, the results reported were mostly outputs (eg estimated number of people with access to the water points constructed) rather than impacts (eg reduction in deaths from diarrhoea). Changes that were hard to calculate (including whether they can be clearly attributed to DFID), such as improvements in national institutions, were not included. For this reason, the Results Framework offers only a partial picture of DFID’s WASH results over the period.

DFID’s WASH programmes are predominantly focused on rural populations in low-income countries, particularly in Sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia. The majority of these projects use ‘Community-Led Total Sanitation’, which was first developed in Bangladesh in 1999 under a DFID funded programme. It has since been widely adopted around the world as an approach to eliminating open defecation. DFID also provides support to partner governments to strengthen national systems for WASH provision.

Methodology

For this review we:

- Conducted a literature review, drawing mainly on existing reviews and syntheses.

- Mapped DFID’s WASH activities and expenditure over the period by country, delivery channel, objectives and activities.

- Assessed the methods used to collect results data and measure value for money.

- Examined research funded by DFID and how lessons are captured and shared across the portfolio.

- Conducted desk reviews of 25% of the 71 programmes that contributed results to DFID’s Results Framework, examining programme documentation and conducting telephone interviews with DFID staff and implementers. Our sample (which included 4 centrally managed programmes, 13 country- based programmes and 1 multilateral partnership) was selected so as to cover half of the results reported and a range of programme types and delivery channels. A proportion of the sample was selected randomly

- Undertook detailed case studies of DFID’s WASH programming in two countries: Mozambique and Zimbabwe. In two-week visits to each country, we interviewed stakeholders and visited a sample of project sites, where we checked local results data and assessed whether the institutional, technical and financial conditions were in place to achieve sustainable results. Mozambique and Zimbabwe were selected as case studies because of their high density of WASH programming.

- Consulted 30 external stakeholders and experts from the UK and abroad.

More details of our methodology are included in Annex 1. The full methodology is available in our Approach Paper.9

There are a number of limitations to our methodology. We assessed the credibility of DFID’s results claims against the underlying data and checked it against feedback from stakeholders. However, we did not carry out an independent impact assessment from new data. There are limits to the conclusions we can draw as to the impact of the portfolio because most of DFID’s own results data is at output level. We were unable to compare cost-effectiveness across different delivery channels as we had intended, because of a lack of comparable data and benchmarks on value for money across DFID WASH programmes. Finally, we acknowledge that our case studies may not be fully representative of the WASH portfolio. They did, however, generate useful additional insights to complement other data sources.

Is the results claim credible?

In its Annual Report for 2014-15, DFID stated that it had provided 62.9 million people with access to WASH over the 2011 to 2015 period, exceeding its target by 2.9 million.10 This is the number of people that DFID claims have gained access to clean water, toilets or handwashing facilities, or who have been reached through programmes to encourage better hygiene practices.

DFID’s commitment on WASH is a ‘reach target’ – that is, it refers to the number of beneficiaries reached through DFID programmes. Primarily it measures outputs rather than impacts, ie the scale of results, rather than the difference made to the lives of beneficiaries. Nonetheless it provides the UK public with a useful measure of the UK’s contribution to an important international development target, included in both the MDGs and the Global Goals.

The figure is derived by collecting output figures from across WASH programmes, including centrally managed programmes and those run by country offices. DFID has provided detailed guidelines on how to interpret the indicator and how to calculate beneficiary numbers. The figures provided by implementers are checked by results advisers in DFID and then compiled centrally.

We subjected DFID’s results claim to a series of checks to determine its credibility. In our two case study countries, we verified that DFID and project staff were able to produce the source data that had been used to generate the results, including at a sample of individual project sites. In all but one instance (a centrally managed project, which did not feature in the country results),11 we were able to trace the totals back to the supporting evidence.

Across all the projects we examined, both in our country case studies and in our 18 desk reviews, we found that DFID had monitored its implementing partners on at least an annual basis in order to collect results data. In some cases, we found evidence of DFID challenging the data presented by its implementers and calling for further evidence. In Mozambique, in three of the eight WASH projects, the results had been independently verified.

Beneficiary numbers are usually derived from assumed access rates, rather than by counting individual beneficiaries. When DFID funds the construction of a WASH facility, it assumes that a certain number of people living in the vicinity will have gained access. These assumptions are usually derived from national planning guidelines which are used by all the national authorities and donors working in the sector. They are necessarily approximate, as actual use of water points may vary substantially from one location to the next and according to season. For instance, programmes in Mozambique assume 300 people per water point, though government officials reported single water points serving as many as 2,900 people. Nonetheless, assumed access rates are widely accepted in the sector as a reasonable proxy for beneficiary numbers.

There are a number of conservative assumptions built into DFID’s calculations. DFID’s guidance specifies that individual beneficiaries may be counted only once, even if they have received multiple types of assistance 12 DFID is wary of the risk of double counting individuals who may have received WASH support through different channels. In some countries, it therefore omits entire programmes from DFID’s Results Framework.

The total figure is an approximate one, as DFID itself acknowledges. It represents the results that DFID can confidently claim, based on population-based assumptions and available information, rather than being a complete account of its programming. Within these limitations, we can confirm that the result claim is credible, that DFID has exceeded the target the UK government set itself, and that the claim provides a valid indication of DFID’s contribution to global WASH access results.

DFID’s WASH portfolio has delivered impact, but the extent of this is not measured

WASH access is a measure of output rather than impact – it tells us how many people gained access from DFID funded interventions, rather than what difference the investment made. The literature tells us that WASH investments are able to generate a range of other development benefits in the right conditions. Health benefits, particularly for infants, are the most clearly documented. There is also some evidence for improvements in education, nutrition, livelihoods and empowerment of women.

We have some evidence from programme evaluations that DFID WASH programmes are generating wider development impact. For example, in Bangladesh, DFID spent £48.5 million on the Sanitation, Hygiene and Water Supply Project between 2007 and 2013. This targeted the poorest regions with the provision of arsenic-safe water, improved sanitation facilities and hygiene messages. The project claimed to have reached a total of 21.4 million people with hygiene promotion activities. It provided around 1.8 million people with access to clean water and over a million children with clean water and latrines in their schools. It also worked with the government to support policy development and build institutional capacity. A programme evaluation found the project had led to increases in school enrolment and reductions in drop-out rates, particularly for girls. Improvement in sanitation facilities had led to a reduction in water-borne diseases: the diarrhoea rate for children under five fell from 11% to 5.1% in the target area, alongside reductions in parasitic worms, malaria and skin infections.13

The DFID funded Sanitation, Hygiene and Water in Nigeria project (phase 1) invested £30 million between 2010 and 2013. By project completion 1.43 million people were identified as living in communities certified to be open defecation free. An impact study found significant reductions in the incidence of infant diarrhoea and resulting increases in school attendance in these communities. It also found that women were spending less time fetching water and taking care of sick children, although it was not able to quantify the time saved.14

In Ethiopia, DFID contributed £66 million to the government’s Water Supply and Sanitation Programme (WSSP), which constructed 9,800 rural water supply schemes supporting 4.21 million people (of which 1.9 million were attributed to DFID’s funding). Again, DFID’s evaluation data reports wider impacts in the form of a reduction in the burden of disease and increased school attendance.

Examples such as these indicate that wider development impacts are being achieved through DFID’s WASH programming. However, from the evidence available, we cannot reach conclusions as to where and to what extent these impacts are occurring. Impact data is not routinely available at the programme level. Nor is it aggregated at either the international or the country level. Around half of the programmes in our sample planned to conduct an external evaluation of some type, but many are not set up to generate the evidence that would allow impact to be measured.

During our site visits, we found that impact data was not being collected, even when it was readily available. Local authorities in both Mozambique and Zimbabwe keep detailed health statistics and school attendance data in the areas where DFID is investing in WASH. Examples of these were shown to us by local officials and project staff, but they told us this data was not collected or used by DFID. The increasing availability of such information is a result, among other things, of investments by DFID and other donors in strengthening health and education systems. By monitoring this data, even at sample sites, DFID could assess whether its intended results were achieved and whether the intended impacts were likely to be achieved. Monitoring local health statistics would not on its own demonstrate that any improvements were directly attributable to DFID’s WASH investments. However, if the health figures were not improving as expected, it would indicate a need for further investigation, perhaps leading to adjustment of programme activities.

Monitoring impact data would also enable DFID to explore what additional elements could be built into its WASH programmes to ensure wider impact. For example, there is growing recognition of the importance the WASH sector plays in tackling issues of gender and vulnerability to violence. A DFID research programme, ‘Sanitation and Hygiene Applied Research for Equity’ (SHARE), has produced a toolkit on how to design WASH facilities so as to reduce vulnerability to violence.15 As these practices are taken up in DFID programmes, we would expect them to be accompanied by monitoring arrangements to determine their effectiveness. Tracking impact data would also help DFID to identify opportunities for its WASH interventions to complement programming in health and education, given that they share some of the same objectives.

It is clear that the thorough and systematic approach that DFID uses to capture reach data in order to report against DFID’s Results Framework is not being matched at the impact level. Research undertaken for this review confirms the existence of evidence indicating positive links between DFID interventions and improved outcomes at beneficiary level. The lack of attention given to collecting data on these wider impacts is an important gap, indicating strongly that DFID could do more to maximise development impact, both across geographies and over time.

DFID targets the poorest areas, but not necessarily the most vulnerable individuals

Most of DFID’s WASH expenditure is in low-income countries facing significant human development challenges. Within these countries, DFID concentrates its investments in the poorest areas. It works with partner governments and takes account of national poverty statistics in deciding which areas to prioritise. The accuracy of this targeting is limited to some extent by the quality of national statistics. While it is usually possible to identify the regions and districts most in need, data down to the level of individual communities is often unavailable.

Research carried out by the World Bank highlights the importance of targeting development resources to specific groups, in order to reduce poverty.16 However, the selection of target groups needs to be done with care, and there are costs associated with accurate targeting, given the high information needs.

DFID proposes to change how it measures its WASH results, in line with a new international definition. In the future, someone will be counted as having ‘access’ to basic water only if their round trip to the water point takes less than 30 minutes.

There are sound reasons for this change – including evidence that the health benefits fall away if the journey to fetch water takes more than 30 minutes. Yet there is also a tension between this more ambitious target and the ‘leaving no one behind’ commitment. In remote areas with sparse populations, the cost of provision at this higher standard is likely to rise dramatically and may become prohibitive. DFID is yet to decide how to

reconcile this conflict.

Across our sample, more than three quarters of programme design documents emphasised the importance of serving women and marginalised groups, such as the elderly or those living with disabilities. However, because its monitoring systems are focused on collecting reach data, using assumed access rates, DFID is not systematically monitoring whether these groups are actually being reached by its WASH programmes. For example, the number of women and girls reached is often calculated on the basis of general population statistics, rather than actual data on use. We found that some of DFID’s implementing partners collect detailed information on marginalised groups, but this is not usually passed on to DFID. As a result, DFID is not currently in a position to say whether its provision of water points or sanitation facilities benefit marginalised people within the communities they serve. DFID does not currently identify systematically what additional programming elements might be required to ensure equitable access.

In the context of the Global Goals and the commitment to ‘leaving no one behind’,17 this is an important gap. DFID has ongoing research exploring the theme of equity in WASH provision, which should help with the design of programmes that take into account the needs of vulnerable groups. Meeting the Global Goals commitment will require DFID to work with national governments and its implementing organisations to obtain more detailed baseline data and to monitor the impact of its programmes on different groups.

Meeting the Global Goals commitment to ‘leaving no one behind’ will call for more programming targeted to the needs of specific marginalised or vulnerable groups. One of those is infants, who are more affected by poor WASH access than others. Ninety percent of those who die from diarrhoeal disease are aged five or under.

In Zimbabwe, DFID is funding ground-breaking research into child stunting. It has been observed that about 40% of cases of child stunting in rural Africa can be attributed to either poor nutrition (33%) or poor sanitation (7%). The Sanitation, Hygiene, Infant Nutrition Efficacy Project (SHINE) Project is conducting a clinical trial to test the hypothesis that continual ingestion of chicken faeces by infants damages the gut and compromises the immune system, contributing to stunting. It will publish its results in 2018. If the link is proven, it will highlight the importance of targeted hygiene interventions, such as providing play pens for infants while their mothers are occupied in the fields.

Targeting the urban poor is a growing challenge in many rapidly urbanising countries. While the bulk of DFID’s WASH investment goes to rural areas, programmes are increasingly exploring the challenges of working in urban slums, where the costs of sanitation are particularly high. Of our 18 desk studies, 12 included some urban programming. For instance, the ‘Water Supply and Sanitation Programme’ (WSSP) in Ethiopia has invested in water schemes in 61 towns, reportedly reaching 900,000 people. DFID is funding ‘Water and Sanitation for the Urban Poor’ (a not-for-profit company), which is helping to develop more cost-effective models for providing WASH in urban settings. DFID has also supported the creation of Cities Alliance, led by UN-Habitat, which includes a focus on upgrading slums around the world.

WSP is a World Bank Trust Fund programme working in 25 countries, including Mozambique. Donors contributed a total of $234 million (£164 million) between 2011-15, around a third of which was from DFID. Mozambique’s capital, Maputo, where around 80% of the estimated 1.7 million population live in peri-urban settlements (‘barrios’), has a particular challenge with urban sanitation. Just 9% of homes are connected to the sewerage system. While just over a third of people have a septic tank, over half of all Maputo’s faecal sewage is simply buried in back yards, which causes contamination of the water system. WSP has been helping enable cost-effective collection and disposal of sewage by small contractors, as shown here. It has done this by providing investment and equipment, building skills and helping the government to create appropriate regulations.

How sustainable are DFID’s WASH results?

Sustainability is a particular challenge in the WASH sector

Sustainability is a critical factor in achieving WASH impact. To deliver the expected development benefits, WASH access needs to become a permanent part of people’s lives.

Sustainability in WASH has several dimensions. Water facilities need to be technically sustainable, in relation to local conditions and with regard to ongoing maintenance requirements. They need to be anchored in sustainable institutional arrangements, often involving a mixture of government institutions and local community structures, to make sure they are properly managed. They need to be financially sustainable, with a process for generating revenues from government or households to meet the costs of operations and maintenance over the long term. Environmental sustainability also needs to be considered; there needs to be sufficient water resources to maintain water supplies and for pollution risks from sanitation to be managed.

Sustainability in sanitation and hygiene also calls for changes in behaviour. The literature is clear that a sustained change in hygiene practices calls for intensive engagement by the implementer with beneficiary communities over an extended period, with regular reinforcement.18 In Mozambique, staff on one of the projects told us that communities that have declared themselves ‘open defecation free’ often relapse, because the benefits of sanitation and hygiene are not well understood.

For these reasons, sustainability is a major challenge for DFID and other donors in the WASH sector. A 2003 NAO review of DFID’s WASH projects found “a lack of available evidence to assess the extent to which DFID’s projects are achieving a lasting beneficial impact. Half of the available assessments concluded that it was too early to judge the likelihood of sustainability and, of the remainder, two thirds of reports raised doubts and risks as to whether a sustainable impact would be achieved.”19

Thirteen years on, we find that the situation has not improved substantially. While DFID programme documents underline the importance of sustainability, the methods used to monitor and report on results of interventions do not incentivise DFID staff or implementing partners to focus on this.

WaterAid now requires all its WASH programmes to verify the continued function and use of WASH facilities at set points (one, three, five and ten years) after their construction. It uses simple ‘red flag’ indicators to show when there is a problem that requires further investigation. According to the NGO, “it is unlikely that sustainability will be achieved if it is not monitored.”

DFID does not approach the sustainability challenge in a systematic way

The WASH experts that we consulted agreed that long-term sustainability requires a ‘systems development approach’ – building national capacity to develop, finance and manage WASH infrastructure and programmes. This should be an area of comparative advantage for DFID, given its long experience of system building in other sectors, such as health and education.

We found that while many DFID WASH programmes include investments in national systems, this is not being done consistently across the portfolio. One area where DFID is very active is in strengthening national information systems for WASH, which features in the majority of the DFID programmes we reviewed. These information systems provide partner countries with the means to measure WASH access and identify gaps or slippage in hygiene and sanitation practices – an important element of sustainability.

DFID’s engagement with national governance is less systematic. For example, many DFID programmes assume that national governments will take on responsibility for WASH facilities or activities once DFID’s financing comes to an end. This depends on political will, financial resources and institutional capacity, usually at both national and local levels. There is no consistent approach for making sure that these conditions are in place. In reality, the prospects of successful transfer vary substantially from one country to another. In Nepal and Ethiopia for example, DFID’s own analysis says that progress is likely to continue beyond the life of DFID’s programmes. In Zambia, by contrast, low government budget allocations to WASH and the slow release of funds were identified by DFID as posing a major risk to sustainability, although DFID informs us this situation is now improving.

Local governance arrangements are also key to sustainability, but tend to lapse if not supported for a sufficient period. In the programmes we reviewed, local institutions were not supported for long enough to ensure they were sustainable. For example, programmes in Nepal and Vietnam depend upon local governments providing continuing support to community groups. Their willingness and capacity to do so is unclear. Some experts believe that voluntary community arrangements need to develop into more formal management structures, such as public-private partnerships, in order to be sustainable. However, these are not yet a feature of DFID’s programming.

There are also other threats to sustainability that are not being addressed. A key risk in many countries is water security. Economic development generates increased pressure on scarce water resources, including from industry and commercial agriculture. National governance arrangements are needed to secure the rights of the poor to water, in the face of competition from more powerful economic constituencies. Most DFID WASH countries have not yet begun to address these longer term sustainability challenges.

We note that DFID is conducting research on how to achieve sustainability in WASH. This includes trialling some innovative new approaches to providing sustainable sanitation services in urban areas jointly with the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation.

The reporting of DFID’s overall results claim is inconsistent and misleading on sustainability

The indicators for the WASH target in DFID’s Results Framework refer to the number of people who gain ‘sustainable access’ to clean water and improved sanitation.20 In practice, however, DFID does not attempt to measure the sustainability of results at this level. Its internal guidance states that this “would require monitoring well beyond the timespan of the [Results Framework]. It is therefore not possible to require that all interventions are verified as sustainable”.21 As a result, the 62.9 million result reported by DFID actually measures initial, rather than sustainable, access.

There is some logic to this position. As DFID’s Results Framework is designed to capture and report results achieved within a five year timeframe, it cannot also verify that the results have been sustained for five or ten years. Yet it means that the incentives generated by DFID’s Results Framework are to maximise initial WASH access, rather than sustainable impact.

DFID’s 2015 Annual Report omits the word ‘sustainable’ from the results claim. However,22 the summary posted on its public website refers to ‘sustainable access’ for water and sanitation, which in our view is inaccurate.23 DFID is not, in fact, measuring sustainability.

DFID does not create incentives for its suppliers to focus on sustainability

DFID does not have effective systems for monitoring the sustainability of its WASH results. Most WASH programmes are too short in duration (three to five years) for sustainability to be established and verified within the life of the programme. Yet in none of the programmes we reviewed did DFID require its implementers to continue monitoring beyond programme completion. In a few instances, we noted that DFID’s partners (such as WaterAid and Unicef) were carrying out extended monitoring for their own purposes, but the results were not being passed on to DFID.

Sustainability checks are increasingly being adopted as good practice in the WASH sector. This is an area where DFID has fallen behind some other donors. For example, the Dutch Development Agency and USAID now use sustainability checks for up to ten years after programme completion and these checks can be linked to incentive payments or penalties. While the effectiveness of this approach is yet to be proved, experts in the sector that we consulted were convinced that sustainability checks are key to encouraging both implementers and partner governments to increase their focus on sustainability.

Across the department, DFID is increasing its use of payment-by-results contracting, where part of the payment is withheld until there are verified results.24 This is intended to create stronger performance incentives for suppliers. Most of the stakeholders we spoke to were broadly positive about the potential for payment-by-results contracting in the WASH sector. Some, however, raised concerns that it may not always provide the right incentives for suppliers to focus on sustainable results.

The centrally managed ‘WASH Payment by Results Programme’ (2013-2018) is DFID’s most substantial trial with payment-by-results contracting in WASH. We saw how it is investing £1.8 million in Mozambique on sanitation and hygiene. The programme includes a two year ‘sustainability phase’ when the implementer is required to focus on consolidating its results, rather than expanding its programming. To support payment-by-results contracting, an independent firm is engaged to verify the results, which it does rigorously using geolocated survey data.

The inclusion of the sustainability phase within a five year programme has the effect of compressing delivery into three years, which stakeholders considered too short for behaviour-change interventions. Respondents recognised the value of independent monitoring, but noted it could be costly and time-consuming, taking resources away from implementation. It also means that DFID uses a parallel monitoring mechanism, rather than relying on the government’s WASH information systems, which might undermine long-term sustainability. Furthermore, monitoring is still limited to the five year life of the programme, which is too soon to determine sustainability in sanitation and hygiene.

The DFID funded Protracted Relief Programme in Zimbabwe ran from 2008 to 2012, providing a range of support to 1.7 million people. Among other things, it built latrines, provided water taps in schools and established ‘School Health Clubs’ to promote handwashing. Three years after the completion of the programme, we visited five of the schools. While the latrines were still in use, the water supply had failed or was intermittent in each. In one case the taps were broken and unused. Importantly, the School Health Clubs had ceased to operate and there was no evidence of handwashing. A 2013 programme evaluation concluded that governance structures at the community level were key to achieving sustainable change in hygiene practices.

There were also concerns in Mozambique about the value of focusing a centrally managed programme exclusively on sanitation and hygiene. The local communities we spoke to were clear that sustainable changes in sanitation and hygiene could not be achieved without improved access to water. Recognising this problem, DFID Mozambique will now direct water investments from a new bilateral programme to the same districts. This example indicates how a lack of context-sensitive programming may also pose a threat to sustainability.

It appears that DFID has fallen behind some other donors in this key area of sustainability monitoring. For example, the Dutch Development Agency and USAID now use sustainability checks for up to ten years after programme completion. This mirrors one of the main conclusions of DFID’s 2012 WASH Portfolio Review.25 It is also consistent with the findings of an NAO review in 2003, that DFID’s systems are designed to maximise its delivery of outputs, rather than sustainable impacts.26

DFID lacks convincing methods for ensuring value for money across the WASH portfolio

Value for money is a key consideration across the UK aid programme. For DFID, it means “maximising the impact of each pound spent to improve poor people’s lives”.27 This does not necessarily mean choosing the cheapest option. It means getting to the desired results, taking into account quality and sustainability, at the lowest cost. This includes assessing delivery options at the design stage, controlling costs through the delivery process and measuring results, so that programmes can increase their impact over time. At the portfolio level, it includes monitoring variations in costs and results across countries and programmes, so that lessons can be learnt and corrective action taken.

DFID does not apply a consistent approach for measuring value for money across its WASH portfolio. It assesses delivery options during the design of each project, and it monitors whether implementers are delivering their planned outputs according to the budget. However, it is not currently using convincing methods for comparing input costs or lifetime investment costs including maintenance between programmes. One internal guidance note proposes using Disability Adjusted Life Years (used in the public health field to measure changes in the burden of disease) to measure cost- effectiveness.28 Yet most WASH programmes do not collect this data.

There is no doubt that WASH is a challenging area for value for money assessment. Other development agencies also struggle to do this. Costs vary dramatically, both within and between countries, due to factors such as the state of the local economy, population density and geographical conditions. For example, in Zimbabwe we saw how the cost of a borehole varied from £3,500 in urban Bulawayo to £27,500 in rural Gokwe. Distinguishing natural variation from differences in programme efficiency is not straightforward.

To address this challenge, DFID has commissioned a two year research programme into value for money in WASH. The first results, reported in August 201529, confirmed our own findings that data on value for money across DFID’s portfolio is limited, variable in quality and difficult to compare. The study has proposed techniques and indicators for value for money assessment that should benefit both DFID and other development partners.

DFID has commissioned research into value for money across six countries: Bangladesh, Ethiopia, Mozambique, Nigeria, Pakistan and Zambia. It sought to assess both ‘cost efficiency’ (the cost of providing access to a water point or sanitation facility per assumed beneficiary) and ‘cost effectiveness’ (the cost per actual beneficiary) across DFID programmes. It found that this data was not available for many programmes (mirroring our finding that DFID does not measure ‘actual beneficiaries’ for most of its programmes). Where the data was available, there were large variations across both indicators between countries, resulting in very different rates of return on the investments. The drivers of cost difference were found to be complex and multifaceted, including economic, social, demographic and hydro-geographical factors.

| Bangladesh | Ethiopia | Mozambique | Nigeria | Pakistan | Zambia | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Water cost-efficiency | $21 | $27 | $79 | $31 | $4-6* | - |

| Water cost-effectiveness | $27-32 | - | $132 | - | - | - |

| Sanitation cost-efficiency | $4.5 | - | $14 | $10.6 | - | $3.4** |

| Sanitation cost-effectiveness | $6.9 | - | - | - | - | $4.1 |

* These are humanitarian relief programmes, where per capita costs are usually much lower.

**Cost per person who gained access to a sanitation facility and also received hygiene promotion messages. Costs are expressed in US dollars and refer to programme costs only; gaps indicate where data is unavailable.

The recent trend towards payment-by-results contracting may help to drive improvements in the efficiency in WASH programming. However, as new DFID guidance acknowledges,30 care must be taken to choose a model that creates the right incentives for suppliers to maximise results. DFID is currently experimenting with payment-by-results on a centrally managed programme, to generate lessons on what works in the WASH sector.

We have seen how value for money assessments are made for individual projects and programmes. However, the absence of value for money measures across the portfolio makes it impossible for either DFID or ourselves to draw conclusions about the overall value that DFID is achieving in its WASH portfolio as a whole.

Competitive tendering is not standard across the portfolio

In the absence of value for money metrics across the portfolio, basic procedures such as competitive tendering can play an important role in ensuring greater economy. In both our case study countries however, we found that the major WASH programmes – a Unicef programme in Zimbabwe31 and a programme managed by the Dutch NGO, SNV, in Mozambique32 – had not been competitively tendered. In fact, none of the programmes delivered by Unicef, which account for around 60% of DFID’s overall results for WASH, had been subject to competitive tendering. ICAI recognises that working with multilateral partners is invariably seen as different from working with NGOs and commercial providers. However, ICAI has previously noted the potential value for money benefit of subjecting programme delivery contracts with multilaterals to a market test.

Learning in the WASH portfolio

We explored whether DFID’s WASH portfolio is becoming better at delivering impact by generating and applying lessons from research and experience. We found good evidence of learning in a range of areas.

At the central level, DFID is a significant investor in research and innovation on WASH. It has helped to strengthen the international architecture for WASH through the ‘Sanitation and Water for All initiative’, while building an evidence base to support policy and planning. DFID has supported improvements in data quality – for example, through the ‘Global Analysis and Assessment of Sanitation and Drinking Water’, which reports on developing countries policies and expenditure on WASH. DFID is also a major funder of the WHO/Unicef Joint Monitoring Programme for Water Supply and Sanitation, which generated the data for MDGs reporting.

DFID’s research programmes on WASH include the SHINE programme in Zimbabwe, the ‘Sanitation and Hygiene Applied Research for Equity’ (SHARE) programme (which among other things looks at gender- related violence), and research by the World Health Organization on resilience and adaptation to climate change.33 There is research underway on improving value for money and sustainability in WASH.

Much of this research is accessible online on the DFID funded R4D website.34 The external stakeholders we spoke to all acknowledged the value of DFID’s investment in knowledge generation. We saw less evidence of DFID making use of lessons from other agencies.

At the programme level, there are ‘lessons learned’ sections in each annual review and programme completion report. These provide opportunities for programme managers to assess what is or is not working and make corrections. In addition, more than half of the programmes we reviewed had been subject to, or were planning, an external evaluation.

We encountered several good examples of learning and adaptation within programmes and country portfolios. For example, in Mozambique, DFID found that budget support was having limited impact on WASH results, owing to weaknesses in government policies and systems. It therefore shifted to programmes that were focused on more specific objectives and locations, while at the same time helping to improve the government’s management of the sector. Conversely, in Ethiopia, DFID changed its programme to include support for sector governance and human resource development, so as to increase sustainability. In the face of a changing climate, it also increased its investment in national water resources, while supporting civil society organisations to engage on equity issues and the needs of women and girls. In Zimbabwe, after initial problems with the Unicef-led Rural Wash Programme, DFID put in place an improvement plan. This led to more effective implementation, more focused results management, strengthened oversight, more effective engagement between the key stakeholders and a step change

in results.

There is less evidence of lessons being shared effectively between country offices and with central departments. DFID did not hold an annual advisor retreat in 2015 (saying instead it held a ‘virtual retreat’) and its internal WASH ‘theme site’ has fallen into disuse. There is no structured process for compiling and sharing lessons from annual reports and project completion reports.35 There is also limited knowledge exchange between WASH advisors and those working in related fields, such as health, education, rural development and women’s empowerment. DFID has considerable experience of building sustainable institutions in sectors such as health and education, and could draw on this experience for its WASH portfolio.

Issues and recommendations

While we conclude that DFID’s claim of reaching 62.9 million is a valid indication of the UK’s contribution to extending WASH access, we identify a number of concerns that need to be resolved in the short to medium term. In this section, we make broad recommendations and highlight issues of concern that need to be addressed. We expect the DFID management response to this report to outline how the department will go about addressing each of these areas of concern and the time period over which it will make a full response.

Results

Recommendation 1

DFID should improve the measurement and reporting of the development impact of its WASH programmes, particularly for vulnerable groups.

Issues of concern

DFID does not systematically monitor the impact of its programming on priority groups who suffer disproportionately from poor WASH access (including children, women and girls, the aged and people with disabilities). Monitoring methods that capture actual usage rather than assumed access would provide more accurate results.

DFID does not regularly collect data on the wider development impact of its WASH interventions, such as on health outcomes or girls’ school attendance, even where this information is readily available. Monitoring of emerging impact, even on a limited sample basis, would help DFID assess whether its programmes need to be adjusted in order to maximise impact.

Although DFID undertakes evaluations for individual projects, DFID does not have sufficient data to assess whether its WASH programming overall is having the desired wider impacts on development.

Sustainability

Recommendation 2

DFID should embed sustainability in its WASH programming and measure how well this is implemented.

Issues of concern

DFID’s Results Framework claims to report the number of people who have achieved sustainable access to clean water and improved sanitation and hygiene. In practice, however, DFID is currently measuring and reporting initial, not sustained, access.

DFID does not gather evidence systematically to demonstrate whether its WASH results are being sustained after its funding ends.

In the absence of a systematic approach to achieving sustainability in WASH programming, attention given to the institutional and financial dimensions of sustainability varies from programme to programme.

The typical three to five year duration of DFID’s WASH programmes is often too short to ensure sustainability.

Value for money

Recommendation 3

DFID should act quickly on the results of its value for money research to develop a suitable framework for measuring value and guiding programming choices.

Issues of concern

While we recognise that research into value for money is underway, DFID is not yet using a convincing methodology or consistent data to enable it to compare the return on its investment across WASH programmes to help identify inefficient programmes.

The WASH programmes implemented by Unicef (which make up 60% of WASH results) are not subject to competitive tender. In the absence of competitive tendering, DFID may need additional methods for assessing whether Unicef represents value for money compared to alternative delivery options, including NGOs and commercial providers.

DFID’s move towards the use of payment-by-results in WASH is potentially a positive step, but needs to be undertaken carefully in order to create the right incentives for suppliers to focus on sustainable results. There are tensions to be managed between the need for independent verification of results in a results-based contract and the goal of strengthening national monitoring systems.

Learning

Recommendation 4

DFID should improve how learning on WASH (including from its research programmes) is shared throughout the organisation.

Issues of concern

Issues of concern

DFID does not systematically capture and disseminate lessons from its own programmes generated by annual reports and programme completion reports. There is no regular reporting on achievements and lessons learned across the portfolio.

Lessons from DFID funded research on WASH are not being fully reflected in project design and monitoring documentation.

DFID could invest more in knowledge exchange between WASH and related sectors, such as health and education, to improve how the wider results of WASH interventions are measured. This would also help in identifying how WASH programmes and programmes in other sectors can reinforce each other.

Annex 1 Methodology

Our approach consisted of a number of elements. We assembled and analysed available information on impact from across DFID’s WASH portfolio and DFID’s results claims. No new impact data was generated. Instead the focus was on examining data which was already available and subjecting it to various tests of credibility.

- We undertook a literature review, drawing mainly on existing reviews and syntheses.

- We undertook a high-level portfolio review where we mapped DFID’s WASH activities and expenditure over the period, capturing information such as where spending took place, types of projects, their objectives and key activities and delivery partners.

- We looked at DFID’s methods for collecting results data and measuring value for money. We also reviewed DFID’s research information and how lessons are captured and shared across the portfolio.

- We conducted desk reviews of 25% of the 71 programmes that contributed to DFID’s Results Framework by examining programme documentation and conducting telephone interviews. Our sample (which included 4 centrally managed programmes, 13 country-based programmes and 1 multilateral partnership) was purposely selected so as to cover half of the results reported and a range of programme types and delivery channels. It also included a random selection (8 of the 18 projects). We used an analytical framework based on learning from the literature review. This allowed comparisons to be made against common assessment criteria for each of the sample programmes.

- We prepared detailed case studies of DFID’s WASH programming in two countries: Mozambique and Zimbabwe. We gathered evidence in three areas: how DFID seeks to maximise impact; how it measures impact; and how it ensures sustainability. In two-week visits to each country, we interviewed stakeholders, including implementers, government counterparts and other donors, and visited a sample of implementation sites. We assessed the range and quality of results data reported at the programme level and compared it with plans and targets. During the site visits, we paid particular attention to whether the institutional, technical and financial conditions were in place to achieve sustainable results. Mozambique and Zimbabwe were selected because of their high density of WASH programming. We selected a minimum of two sites per programme to visit. These were geographically disbursed and chosen to demonstrate the range of project interventions undertaken (eg urban, rural). We prioritised project sites where interventions had been fully operational for at least two years. We are aware that results from these two countries are not representative of the portfolio as a whole. However, they yielded useful insights to complement other data sources.

- We consulted 30 external stakeholders and experts both in the UK and abroad. Both our methodology and this report were independently peer reviewed, and the methodology can be read in full on the ICAI website.36

Limitations to the methodology

There were a number of limitations to our methodology. We were able to assess the credibility of DFID’s results claims against the underlying data, feedback from stakeholders and other information sources. However, we did not conduct an independent impact assessment, which would have involved monitoring over an extended period. Where there were gaps in DFID’s impact data, we were not able to reach our own conclusions on the results achieved.

There were also limits to our ability to conclude on value for money. In the face of wide variations in WASH delivery costs between and within countries, we found that DFID does not collect data on standard value for money indicators that would have enabled direct comparison. However, we have drawn attention to areas where DFID could do more to maximise value for money.

Annex 2 Detail of scoring

Question 1: Impact

What has been the impact of DFID’s WASH programming in the 2011-2015 Results Framework period?

DFID repor ted that it had helped 62.9 million people improve their access to water, sanitation and/or hygiene between 2011 and 2015. We found that this results claim was calculated using appropriate methods and conservative assumptions. While this figure is based on assumed rather than actual use, the figure is a credible indicator of the UK’s total contribution to extending global WASH access. There is evidence that DFID’s WASH programmes have generated a range of wider development impacts, including reductions in water-borne diseases and increases in school attendance. However, as impact data is not routinely collected, we cannot assess where and to what extent these wider results are being achieved. DFID’s WASH investments target some of the poorest and most marginalised communities within its partner countries (particularly in rural areas and urban slums). However, DFID lacks mechanisms for targeting its WASH support towards the m ost vulnerable individuals within communities. This is an important gap in the light of the Global Goals commitment to ‘leaving no one behind’. DFID is not yet using credible methods for comparing efficiency and cost- effectiveness across WASH programmes. This makes it impossible to reach overall conclusions about the value for money of the portfolio. DFID recognises this challenge and is in the process of improving its approach to value for money through independent research. The programmes delivered by Unicef, which DFID told us accounted for around 60% of the total results on WASH, were not subject to competitive tendering. Agreements with multilateral organisations such as Unicef make it hard for DFID to put these out to formal competition.

ted that it had helped 62.9 million people improve their access to water, sanitation and/or hygiene between 2011 and 2015. We found that this results claim was calculated using appropriate methods and conservative assumptions. While this figure is based on assumed rather than actual use, the figure is a credible indicator of the UK’s total contribution to extending global WASH access. There is evidence that DFID’s WASH programmes have generated a range of wider development impacts, including reductions in water-borne diseases and increases in school attendance. However, as impact data is not routinely collected, we cannot assess where and to what extent these wider results are being achieved. DFID’s WASH investments target some of the poorest and most marginalised communities within its partner countries (particularly in rural areas and urban slums). However, DFID lacks mechanisms for targeting its WASH support towards the m ost vulnerable individuals within communities. This is an important gap in the light of the Global Goals commitment to ‘leaving no one behind’. DFID is not yet using credible methods for comparing efficiency and cost- effectiveness across WASH programmes. This makes it impossible to reach overall conclusions about the value for money of the portfolio. DFID recognises this challenge and is in the process of improving its approach to value for money through independent research. The programmes delivered by Unicef, which DFID told us accounted for around 60% of the total results on WASH, were not subject to competitive tendering. Agreements with multilateral organisations such as Unicef make it hard for DFID to put these out to formal competition.

Question 2: Results Measurement

Are the aggregate WASH results reported under the DFID’s Results Framework based on credible evidence?

DFID’s reported results for WASH at the departmental level are based on credible data. The projects that we examined were subject to regular review and scrutiny, and we saw credible processes for collating, reviewing and validating outputs from WASH programmes.

However, results reported at the departmental level do not measure sustainable access, even though sustainability is included in DFID’s WASH target. In practice they report only initial access. We found that DFID does not routinely collect information on the health and education results of WASH programmes, even when this data is readily available. Collecting impact data, even on a sample basis, would enable DFID to adjust its programmes in real time, so as to maximise results. It would also make DFID better placed to target its investment towards the most vulnerable individuals within communities. We found programme monitoring to be strong, and we saw good evidence of DFID adapting its programmes and country portfolios as a result of lessons learned. However, there is less evidence that lessons are being effectively shared between country offices, or with related sectors such as health and education.

Question 3: Sustainability

Has the impact from DFID’s WASH programming proved sustainable?

Sustaina bility is a particular challenge in the WASH sector. We found that DFID does not have a coherent strategy for addressing sustainability. While many programmes include investments in building national systems, this is not done systematically.

bility is a particular challenge in the WASH sector. We found that DFID does not have a coherent strategy for addressing sustainability. While many programmes include investments in building national systems, this is not done systematically.

WASH programmes are generally too short in duration to enable the conditions for sustainability to be built. In addition, DFID does not require its implementers to monitor whether results have been sustained beyond the life of the programme. In this respect, DFID has fallen behind some other donors.

We conclude that the systems used by DFID to measure results incentivise a focus on extending initial WASH access, rather than achieving sustainable results.

Annex 3 Bibliography

A New Global Partnership: eradicate poverty and transform economies through sustainable development, Report of the High-Level Panel of Eminent Persons on the Post-2015 Development Agenda, United Nations, 2013, link.

Arsenic exposure from drinking water, and all-cause and chronic-disease mortalities in Bangladesh (HEALS): a prospective cohort study. Argos, M., Kalra, T., & et al. (2010). The Lancet, 252-258.

Faecal contamination of drinking water in developing countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Bain, R., Cronk, R., Wright, J., Yanh, H., & Bartram, J. (2014). PLoS Medicine, 11.

Hygiene, Sanitation and Water: Forgotten Foundations of Health. Bartram, J., & Cairncross, S. (2010, November 9). PLoS Medicine, 7(11), 1-9. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1000367.

What impact does the provision of separate toilets for girls at school have on their primary and secondary school enrolment, attendance and completion? A systematic review of the evidence. Birdthistle, I., Dickson, K., Freeman, M., & Javidi, L. (2011). London: DFID.

Global, regional and national causes of child mortality in 2008: a systematic analysis. Black, R., Cousens, R., Johnson, H., Lawn, J., Rudan, I., Bassani, D., Mathers, C. (2010). The Lancet, 1969-87.

Domestic water and sanitation as water security: monitoring, concepts and strategy. Bradley, D., & Bartram, J. (2013). Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A, 371.

Applying a life-cycle costs approach to water; costs and service levels in small town areas in Andhra Pradesh (India), Burkina Faso, Ghana and Mozambique, WASH Cost Working Paper 8. Burr, P., & Fonseca, C. (2013).The Hague: IRC International Water and Sanitation Centre.

Water Supply, Sanitation, and Hygiene Promotion. Cairncross, S., & Valdmanis, V. (2006). In D. Jamison, J. Breman, A. Measham, G. Alleyne, M. Claeson, D. Evans, P. Musgrove, Disease Control Priorities in Developing Countries. 2nd edition. (pp. 771-792). Washington, D.C.: World Bank.

Hygiene, sanitation and water: what needs to be done? Cairncross, S., Bartram, J., Cumming, O., & Brocklehurst, C. (2010). PLoS Medicine.

The real water crisis: inequality in a fast changing world. Calow, R., & Mason, N. (2014). London: ODI.

Ground Water Security and Drought in Africa: Linking Availability, Access and Demand. Calow, R., MacDonald, A., Nicol, A., & Robins, N. (2010). Ground Water, 48(2), 246-256.

Beyond ‘functionality’ of handpump-supplied rural water services in developing countries. Carter, R., & Ross, I. (2015 – forthcoming).Water Alternatives.

Multi-country analysis of the effects of diarrhoea on childhood stunting. Checkley, W., Buckley, G., Gilman, R., Assis, A., Guerrant, R., & Morris, S. (2008). International Journal of Epidemiology, 37, 816-30.

Rural water supply & sanitation: time for a change. Churchill, A., de Ferranti, D., Roche, R., Tager, C., Walters, A., & et al. (1987). Washington DC: World Bank.

Reducing child mortality in India in the new millennium. Claeson, M., Boss, R., Mawji, T., & Pathmanathan, I. (2000). Bulletin of the World Health Organisation, pp. 1192-9.

Targeting of Transfers in Developing Countries: Review of Lessons and Experience, Coady,D., Grosh, M. & Hoddinott,J.,(2004) World Bank.

WASH Cost End-of-Project Evaluation. Cross, P., Frade, J., James, A., & Trémolet, S. (2013). The Hague: IRC International Water and Sanitation Centre.

Planned, motivated and habitual hygiene behaviour: an eleven country review. Curtis, V., Danquah, L., & Aunger, R. (2009). Health Education Research, 24(4), 655-673.

Hygiene: new hopes, new horizons. Curtis, V., Schmidt, W., Luby, S., Florez, R., Toure, O., & Biran, A. (2011). Lancet Infectious Diseases, 11(4), 312-21.

DFID’s Approach to Value for Money (VfM), DFID (2011) p. 2, link.

Water, Sanitation and Hygiene Portfolio Review, DFID (2012) p. 8, link.

Water, Sanitation and Hygiene Evidence Paper, DFID (2013), link.

DFID Annual Report and Accounts 2014-15, DFID (2015) July, link.

Number of unique people reached with one or more water, sanitation or hygiene promotion intervention, undated, DFID link.

Value for Money (VfM) guidance for WASH programmes: DFID’s Approach to Value for Money, DFID, undated.

DFID’s Approach to Value for Money (VfM). (2011). London: DFID.

Water, Sanitation and Hygiene Portfolio Review. (2012). London: DFID.

Assessing hygiene cost- effectiveness: a methodology. WASH Cost Working Paper 7. Dubé, A., Burr, P., Potter, A., & van de Reep, M. The Hague: IRC International Water and Sanitation Centre. (2012).

Fluoride in natural waters. Edmunds, M., & Smedley, P. (2005). In B. a. Alloway (Ed.), Essentials of Medical Geology. Academic Press.