Achieving value for money through procurement – Part 1: DFID’s approach to its supplier market

ICAI score

The Independent Commission for Aid Impact works to improve the quality of UK development assistance through robust, independent scrutiny. We provide assurance to the UK taxpayer by conducting independent reviews of the effectiveness and value for money of UK aid.

We operate independently of government, reporting to Parliament, and our mandate covers all UK official development assistance.

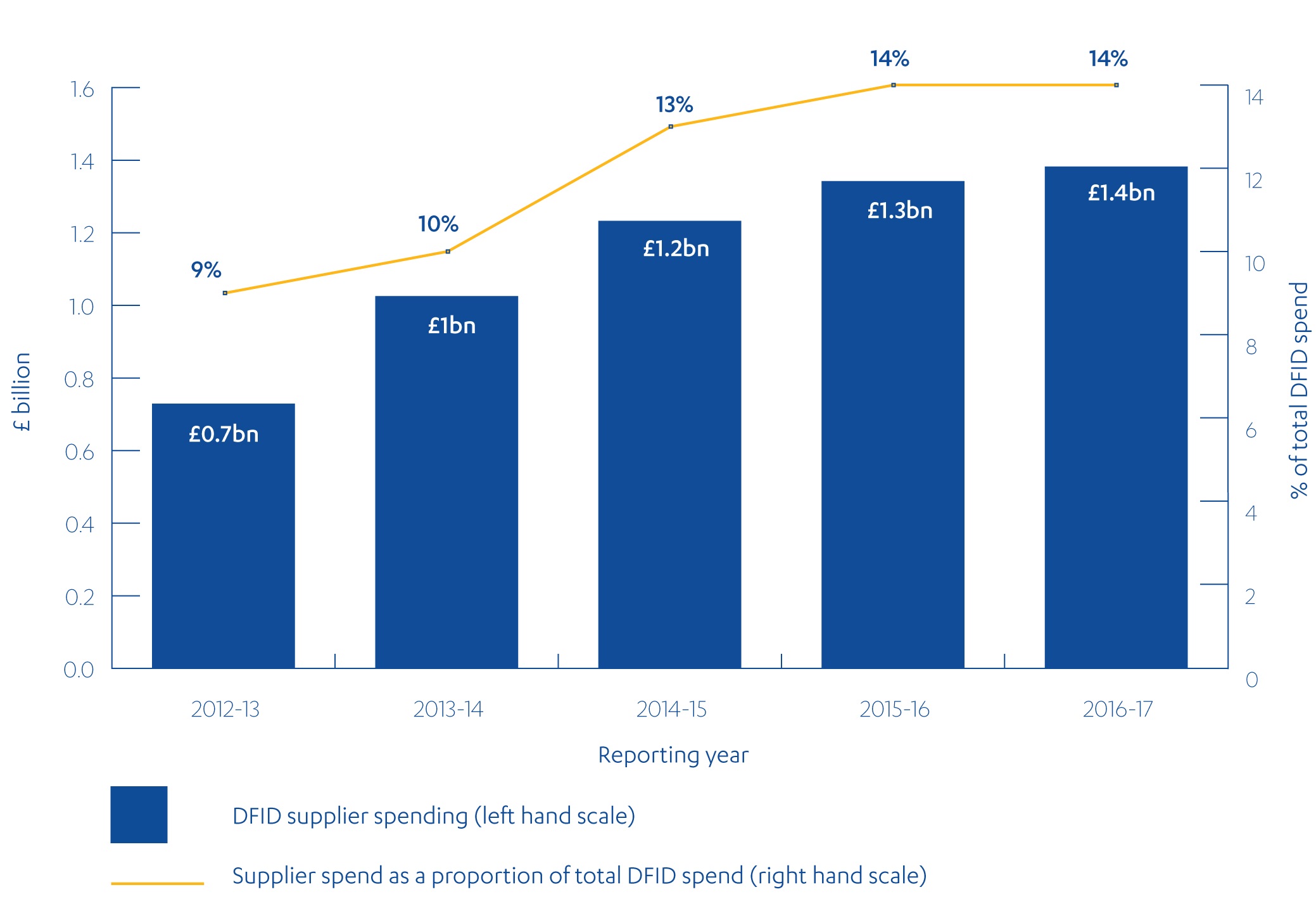

DFID’s spending through suppliers has doubled over the past five years, reaching £1.4 billion last year and making it an increasingly crucial component of securing value for money. In this review we examine how DFID is shaping its supplier market so as to improve value for money over time.

Since 2015 DFID has put in place a more ambitious approach to market shaping. It has introduced a range of measures to analyse its market and derive lessons. There has been a concerted effort to build up commercial capacity within the procurement department and beyond. It has identified issues within its procurement practices that might inhibit competition and launched a number of initiatives to address them. The International Development Secretary has committed to prevent “excessive profiteering”, and DFID is also acting to improve the transparency of supplier fee rates and costs and increase its scrutiny of supplier profits.

These initiatives are welcome and constitute an important part of our green-amber assessment overall, but it is still the case that many actions are too recent to have achieved their full potential impact on DFID’s supplier market.

DFID has exceeded the UK government target of delivering a third of its procurement through small and medium-sized enterprises by 2020, but its efforts to promote the participation of small and micro suppliers and suppliers in developing countries are still at an early stage. From the available data, DFID’s ‘global’ market is not overly concentrated, but there is limited competition in particular sectors and partner countries, holding back efforts to diversify its supplier base. There has been a modest increase in the number of bids per tender and the overall number of suppliers bidding for contracts, but more progress is needed on reducing potential barriers to competition. DFID’s Key Supplier Management Programme and framework contracts are both potentially useful initiatives, but lack clear objectives on market shaping and are yet to have a measurable impact. Both are now being reformed based on lessons learnt.

After a slow start on market shaping, there is now evidence of positive progress and a serious effort by DFID to get to grips with the challenges of achieving value for money through its engagement with its supplier base. We have therefore awarded DFID a green-amber score.

| Individual review scores | |

|---|---|

| Question 1 Relevance – Does DFID’s approach to shaping its supplier market support the objectives and priorities of the aid programme? |  |

| Question 2 Effectiveness and value for money – Do DFID’s efforts to shape its supplier market support value for money? |  |

| Question 3 Learning – Does DFID capture and use learning and knowledge from its interactions with suppliers to improve its use of suppliers and its market-shaping efforts over time? |  |

Executive summary

DFID’s spending through suppliers has doubled over the past five years, reaching £1.4 billion in 2016-17 or 14% of its budget. As this figure has increased, DFID’s procurement practices have become the subject of intense public interest. In 2017, the International Development Committee published two reports on DFID’s use of contractors. The International Development Secretary also commissioned an internal review of DFID’s work with suppliers, which was completed in October 2017.

As procurement is a key driver of value for money in UK aid, the Independent Commission for Aid Impact (ICAI) is undertaking two reviews on DFID’s practice. This first review assesses whether DFID influences and shapes its supplier market in order to improve value for money over time. The next review, to be published in 2018, will explore whether DFID has maximised value for money from suppliers through its tendering and contract management practices. The two reviews assess different aspects of progress made in addressing concerns raised in ICAI’s 2013 report on DFID’s use of suppliers.

In this review we explore whether DFID has an appropriate approach to market shaping, taking account of some of the more recent initiatives. In carrying out our review, we conducted financial and statistical analysis of DFID’s procurement data, assessed its rules and practices against UK government guidance, and collected feedback through interviews with DFID staff, suppliers and external observers.

This is a dynamic area of practice for DFID, as shown by the International Development Secretary’s announcement of further reform initiatives on 3 October 2017, which have emerged from DFID’s supplier review. Our assessment necessarily focuses on evidence from existing actions and initiatives, capturing the impact of DFID’s procurement practices on its supplier market over the past few years. We do not seek to evaluate the effectiveness of the further initiatives announced on 3 October, but of course recognise them as evidence of DFID’s intentions where relevant to our analysis and conclusions.

Does DFID’s approach to shaping its supplier market support the objectives and priorities of the aid programme?

DFID has been making a concerted effort to strengthen its procurement function since 2008, when a cross government commercial capability review pointed to a number of weaknesses. From 2015 onwards, its reform efforts began to include a substantial emphasis on market shaping – namely, understanding how DFID’s procurement influences the market and taking measures, where required, to stimulate competition and build market capacity, so as to achieve better value for money over time. While market shaping is recommended in UK government guidelines, it is a relatively recent focus for most departments.

Since then, DFID has been progressively developing a more comprehensive approach to market shaping. Its commercial vision commits the department to building its supply base and stimulating greater competition. It has identified a range of potential barriers to competition, including lack of visibility of future (‘pipeline’) procurement opportunities, the size and complexity of its contracts and a lengthy procurement process. In 2016 DFID adopted an unpublished Market Creation Plan, setting out action to address these barriers. The action includes:

- improved communication with suppliers

- measures to promote the participation of small and medium-size enterprises (SMEs) and suppliers from developing countries

- refinements to its Key Supplier Management Programme and framework contracts

- the development and implementation of a market segmentation tool.

DFID has worked to improve communication with suppliers, including through an annual supplier conference and 61 early market engagement events in 2016-17. A further strengthening of this work was announced last month, together with action to simplify processes and improve information sharing for small and micro suppliers.

DFID has also been developing market-shaping strategies in particular sectors and countries which present their own procurement challenges. These are supported by commercial delivery advisors attached to particular country offices or spending departments. For example, DFID Nigeria is working to broaden its supplier base through more effective communication of opportunities and measures to promote the participation of Nigerian firms as subcontractors, consortium partners or as suppliers of specialist services. While we welcome this initiative, of the 32 country and sector commercial strategies that we reviewed, only a small number contained specific steps for strengthening the supply chain. We also found that DFID is yet to settle on an approach to promoting the participation of local suppliers. Despite a stated objective to increase their participation, and a 2017 study of the barriers they face, we encountered a mixture of views among DFID stakeholders as to whether the participation of local suppliers should be treated as an objective in its own right.

DFID is in the process of increasing transparency over supplier costs and profits, and the International Development Secretary has made a commitment to prevent “excessive profiteering”. DFID has included open-book accounting in its contracts for some time, but capacity constraints have prevented it from exercising its rights. It has plans to move ahead in this area for priority contracts in 2017. DFID has also been introducing measures to improve transparency of costs, including through benchmarking of fee rates, and to increase its scrutiny of supplier profits. The International Development Secretary’s October announcement included new standard terms and conditions entitling it to monitor and intervene over suppliers’ profits. The impact of these measures on the market is difficult to predict and will need to be carefully monitored.

Overall, we welcome DFID’s increased ambition in this area. The outlines of a credible approach to market shaping are emerging, even though many of the individual activities still need to be tested and refined. We have therefore awarded DFID a green-amber score for its emerging approach, reflecting a significant increase in activity in this area and an overall positive direction of travel.

Does DFID’s shaping of its supplier market support value for money?

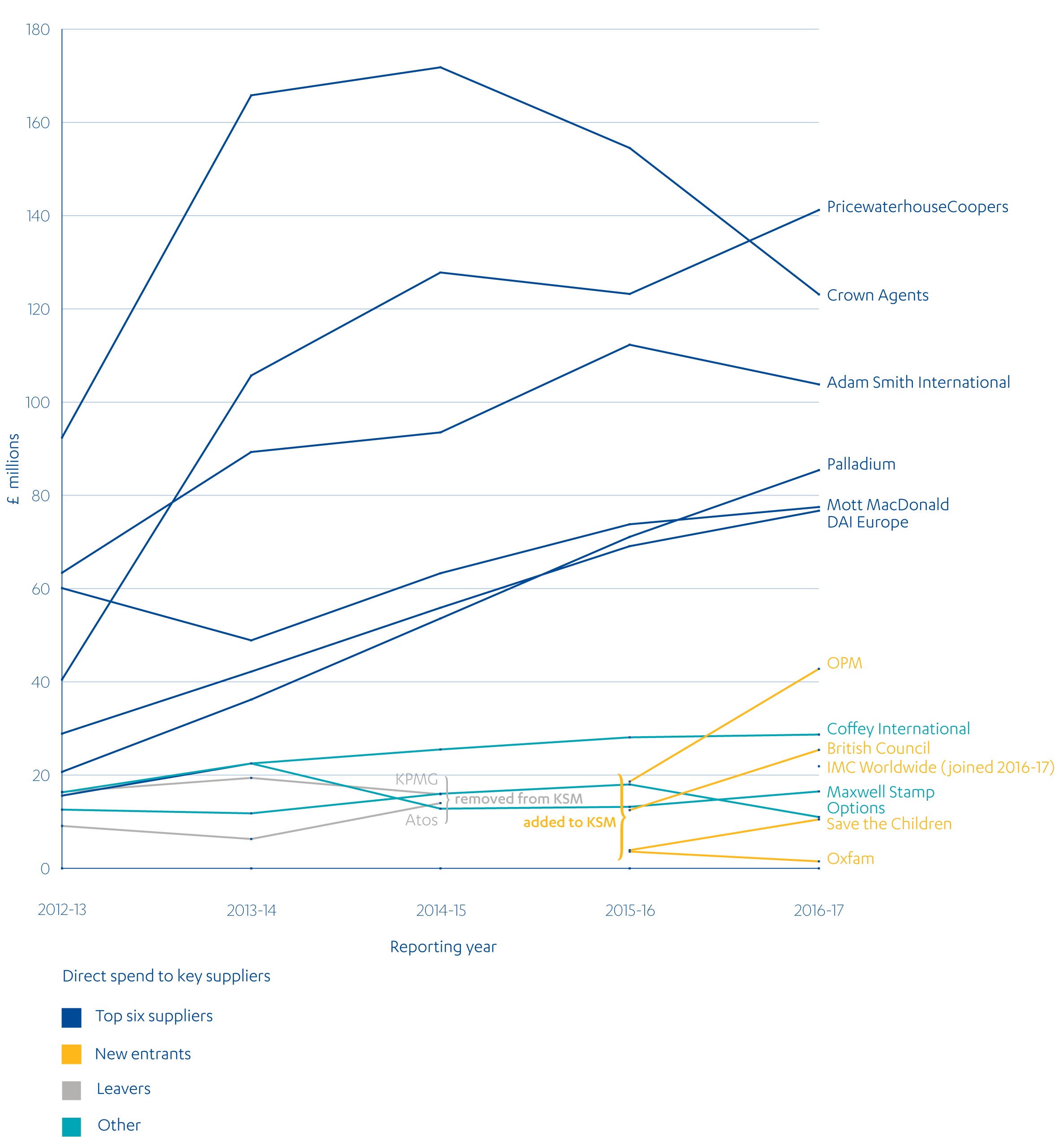

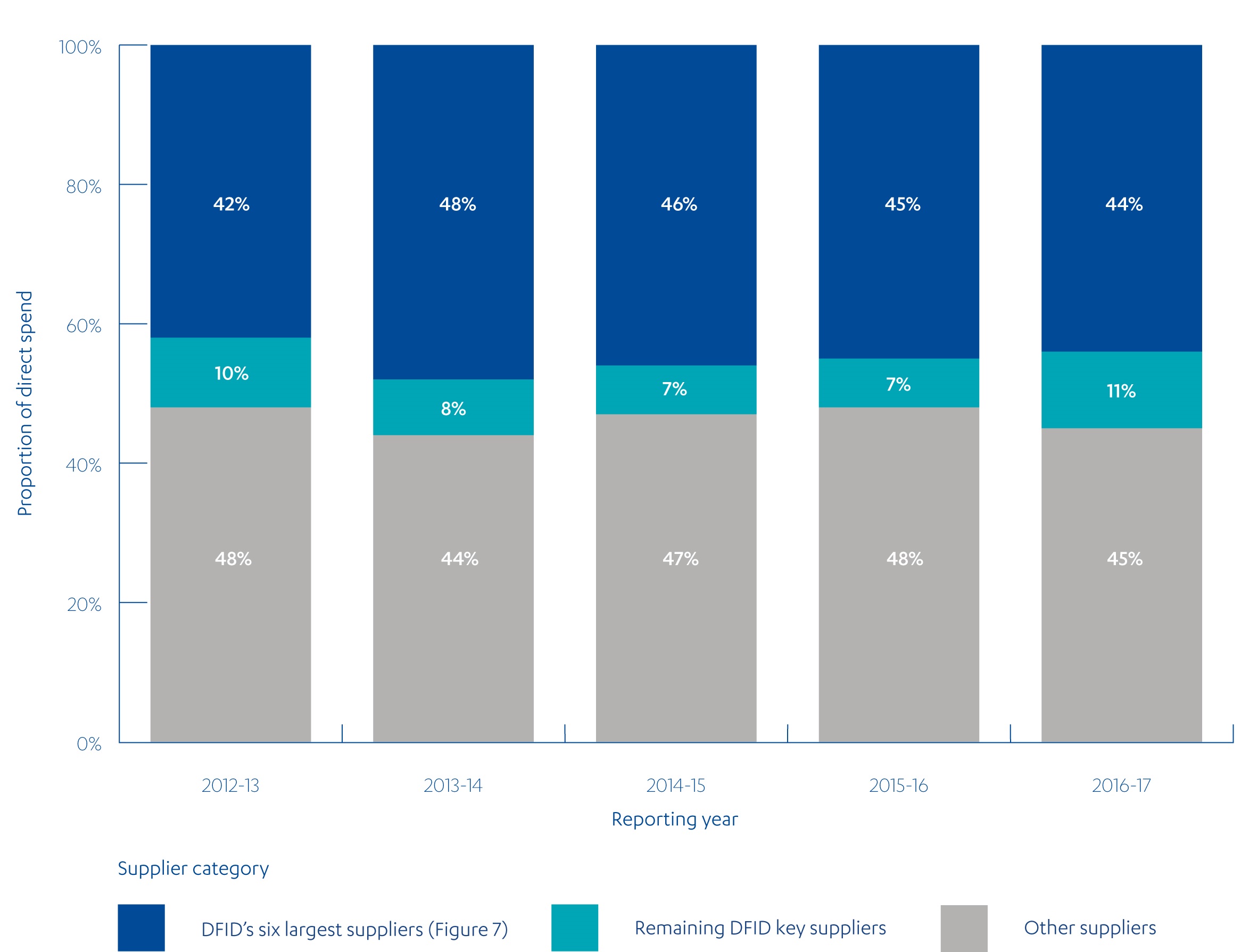

Over the past five years, DFID’s top six suppliers have accounted for 45% of total contract value. They in turn engage second and third tier suppliers – including from developing countries – as subcontractors for delivering programmes. While the data suggests that DFID’s global supplier market is not overly concentrated, it appears to face limited competition in certain sectors and countries. There has been a modest increase in the overall number of suppliers and in the number of bids per tender, reaching 2.9 in 2016-17, but still falling short of DFID’s target of four.

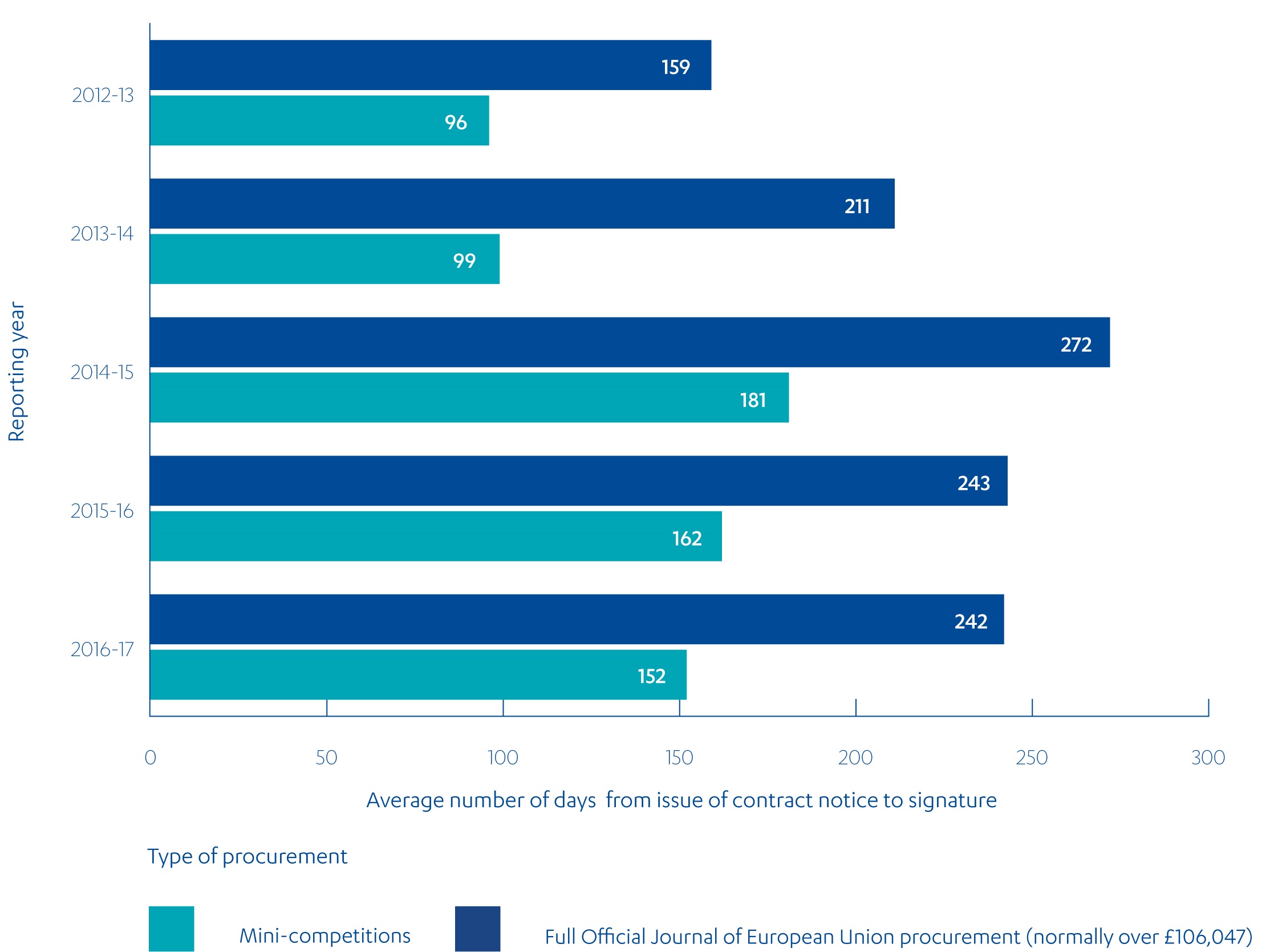

There are a range of features of DFID’s procurement that may make it more difficult for new entrants to challenge existing suppliers. DFID contracts are often large and complex, despite some decline in average size in recent years. In the view of suppliers we interviewed, the level of risk transfer associated with the contracts has also increased. DFID procurement can also be slow, due to its complexity, which can disadvantage smaller firms unable to manage the cost implications. A lack of sufficient notice from DFID of future pipeline opportunities was identified as a further barrier for new entrants. While some of these challenges are inherent in the nature of DFID’s procurement, the department acknowledges a number of areas where it needs to improve.

Despite clear intentions, there has been mixed progress towards the objective of improving market diversity. DFID has met and exceeded the UK government target of delivering a third of its procurement through SMEs, defined as firms with under 250 employees and an annual turnover of less than €50 million. This is positive, but DFID also acknowledges a need to do more to foster a diverse eco-system of suppliers from micro to small and medium-sized enterprises, and to improve its engagement across the different categories.

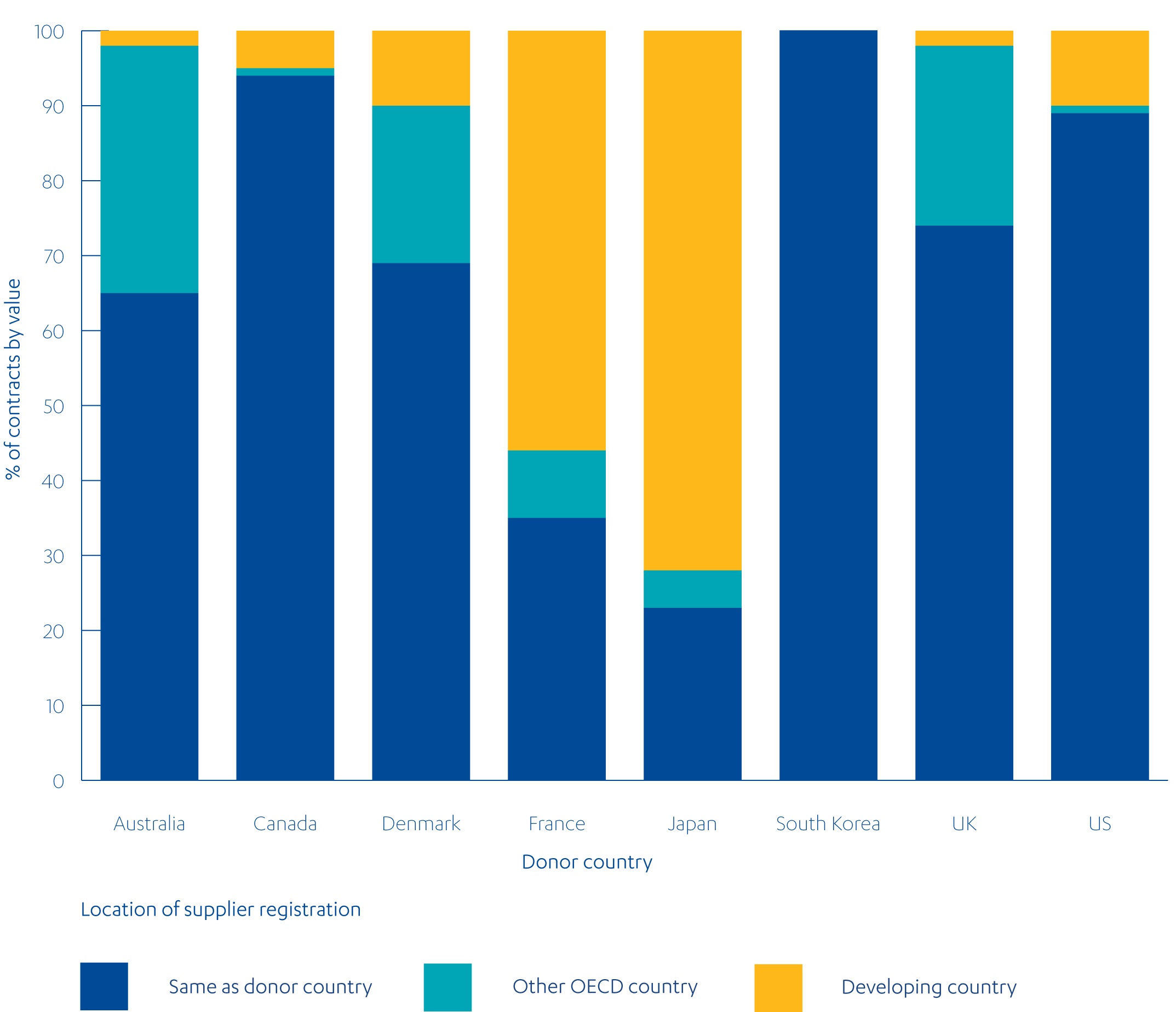

In 2016-17, 92% of DFID contracts by value went to UK-registered suppliers and only 3% to suppliers in developing countries as prime contractors. More local suppliers participate as subcontractors to international firms and some of DFID’s country commercial strategies include measures to help them, although these are at an early stage. DFID is now undertaking delivery chain mapping, but a figure for the value of local supplier participation as subcontractors is not currently captured in DFID’s management information. We found that a systematic approach to promoting the participation of local suppliers is not yet in place and information gaps continue to be a weakness in DFID’s market-shaping work.

DFID’s Key Supplier Management Programme is intended to strengthen its strategic relationships with its most important suppliers. The programme has been operating since 2013, involving structured communication and regular performance appraisals at the portfolio level. It was put on hold during 2017 pending the outcome of DFID’s supplier review, and in October 2017 DFID announced that it would be developed and extended. We agree that a Key Supplier Management Programme is valuable to communicate expectations, raise performance and strengthen DFID’s understanding of its major suppliers. However, we found that the objectives of the programme were not defined clearly enough and that monitoring is not strong enough to identify the programme’s contribution to improving value for money. There are also widespread concerns that additional engagement with DFID could offer key suppliers a competitive advantage. We therefore welcome DFID’s ongoing efforts to improve the programme and maximise its value-added while managing associated risks.

Framework agreements are a tool used across the UK government to simplify procurement in high-volume areas. Suppliers that qualify to be part of a framework can bid for contracts through simpler and quicker mini-competitions. DFID has been using frameworks since 2011, covering around half of its centrally awarded contracts. They have succeeded to some degree in reducing the time and costs involved for DFID, but have had a lower than expected impact on simplifying the process for suppliers. Second-tier suppliers report that the work is dominated by the major suppliers. At this point we find limited evidence that the frameworks have made a significant contribution to developing the supply base. However, DFID is now developing a new generation of frameworks that split contracts into small parcels of work (known as ‘lotting’) to encourage a wider range of suppliers. It is also introducing new systems for allocating work among participating firms and challenging efforts by prime suppliers to tie subcontractors to particular contracts through exclusivity clauses.

Overall, and based on an assessment of tangible achievements to date, we score the effectiveness of DFID’s market-shaping efforts as amber-red. This reflects the fact that the bulk of DFID’s market-shaping initiatives are still in process and not yet mature enough to have had a significant impact on the market. Given recent increases in staffing and the range of positive actions it is now implementing as part of the Market Creation Plan, we would expect to see performance improvements in this area in the near future.

Does DFID capture and use learning and knowledge from its interactions with suppliers to improve its use of suppliers and shape its supplier market over time?

Our 2013 review assessed DFID’s learning on procurement as amber-red. Since then, DFID has taken a range of actions to acquire and apply learning about shaping its supplier market. It has participated in a series of cross-government commercial capability reviews, and various recommendations have been implemented or are ongoing, including commercial reviews of country offices, appointing commercial advisors and introducing compulsory commercial training for all senior civil service staff and senior responsible owners.

At the beginning of 2017, the Secretary of State launched a comprehensive review of DFID’s work with suppliers, and DFID announced action following the review in October. While we cannot yet assess the impact of this action, the review shows the seriousness with which DFID is taking this issue and its awareness of the need for continuing improvement.

We have found evidence of learning in a range of areas. Both the Key Supplier Management Programme and the framework agreements are being analysed, through a process involving broad consultation, and improvements are in the pipeline. DFID has also improved its communications with suppliers on a number of levels.

While we are satisfied that a significant amount of learning has informed the current reform effort, the learning process is still held back by weaknesses in DFID’s management information systems. DFID currently holds information about suppliers on two parallel systems, which are separate from its main project management system. Integration between them is poor, which limits the depth of analysis that can be undertaken, and the system does not include information on supply chains or on contracts let through country offices. DFID has recently approved a business case for the development of a new management information system.

We have awarded DFID a green-amber for learning, in recognition of the substantial effort that has gone into the area and that the work is ongoing.

Conclusions and recommendations

Over the past two years, DFID has been developing a more comprehensive approach to its supplier market, with a view to securing additional value for the taxpayer beyond that offered by individual procurements. It has identified aspects of its procurement that might restrict competition and diversity, and has begun to develop initiatives to address them. Many of these remain at a relatively early stage of development and will need to be tested and refined, but we welcome the more ambitious approach and the learning that has gone into it.

Because of the timescales involved, we cannot yet give these efforts a positive score for effectiveness. We nonetheless assess that there are good prospects for improvement in the coming period, meriting a green-amber score overall.

The research and writing of our review has taken place in parallel to DFID’s own supplier review. We note that several of the actions announced by the International Development Secretary on 3 October affect DFID’s market-shaping activities and are relevant, in particular, to our first two recommendations below. Some of the announced initiatives resonate with our findings, but DFID’s supplier review had a different scope and emphasis, and did not cover all the issues we highlight.

Against this background, our recommendations are as follows:

Recommendation 1:

DFID should adopt a more systematic approach to its stated objective of promoting the participation of local suppliers, to the extent permitted within procurement regulations, including measures at the central, sector and country office levels to encourage the emergence of future prime contractors from developing countries. This might include identifying opportunities for local suppliers to compete directly for DFID contracts, increased supervision of the terms on which prime contractors engage local suppliers, and more inducement of DFID’s prime contractors to invest in building local capacity.

Recommendation 2:

DFID should develop clear plans for how it will progress its use of open-book accounting and improve fee rate transparency, and ensure that its plans are clearly communicated to the supplier market, to minimise the risk of unintended consequences.

Recommendation 3:

DFID should accelerate its efforts to improve communication of pipeline opportunities to the market. It should also assess what potential information advantages are gained by participants in its Key Supplier Management Programme, and ensure that this is counterbalanced by more effective communication with all potential suppliers. Internally, DFID should provide clearer guidance to staff as to what can and cannot be discussed during key supplier meetings.

Recommendation 4:

The next phase of DFID’s commercial reform plans should be accompanied by a stronger change management approach, with explicit objectives that are clearly communicated to staff. Its plans should be supported by robust monitoring and management information arrangements, to enable full transparency, regular progress reporting and mitigation of potential negative effects.

Introduction

Over the past five years, as the UK aid programme has grown, DFID’s spending through suppliers has roughly doubled in cash terms, reaching £1.4 billion in 2016-17 or 14% of its budget. Contracting out to suppliers is only one route by which DFID delivers aid. Others include contributions to multilateral organisations, grants to non-governmental organisations (NGOs) and financial assistance to governments in developing countries.

As spending through suppliers has increased, it has become a matter of considerable public interest, amid concerns about the level of profits made by some suppliers and their ethical standards. In 2017, the International Development Committee published two reports on DFID’s use of contractors and the International Development Secretary commissioned an internal review of DFID’s work with suppliers, which was completed in October 2017.

In light of the importance of the subject to the overall value for money of UK aid, the Independent Commission for Aid Impact (ICAI) is conducting two reviews of aspects of DFID’s procurement practices. This first review assesses how DFID influences and shapes its supplier market in order to secure the best value for money over time. The next review, to be published in 2018,will explore whether DFID has maximised value for money from suppliers through its tendering and contract management practices. They are both performance reviews, as they focus on a core DFID business process (see Box 1).

Box 1: What is an ICAI performance review?

ICAI performance reviews examine how efficiently and effectively UK aid is being spent on a particular area, and whether it is likely to make a difference to its intended beneficiaries. They also cover the business processes through which aid is managed in order to identify opportunities to increase effectiveness and value for money.

Other types of ICAI reviews include: impact reviews, which examine results claims made for UK aid to assess their credibility and their significance for the intended beneficiaries; learning reviews, which explore how knowledge is generated in novel areas and translated into credible programming; and rapid reviews, which are short, real-time reviews of emerging issues or areas of the UK aid spending that are of particular interest to the UK Parliament and public.

This review covers DFID’s engagement with actual and potential suppliers in order to shape its supply chains and achieve better value for money through its procurement. Market shaping is a common element of public procurement and is recommended in UK government guidelines. Our scope is limited to procurement for the delivery of aid programmes by DFID, not the procurement of goods and services for DFID’s own administrative purposes. The review is also limited to DFID’s performance; the behaviour and practices of DFID’s suppliers fall outside our scope. Our review questions are set out in Table 1. A glossary of key terms can be found in Annex A.

Table 1: Our review questions

| Review criteria | Review question |

|---|---|

| 1. Relevance: Does DFID’s approach to shaping its supplier market support the objectives and priorities of the aid programme? | • Does DFID have a clear and appropriate strategy and approach to influencing the shape and structure of its supplier market? • Does DFID have a credible strategy for assessing suppliers’ costs and whether they are making excessive profits? |

| 2. Effectiveness: Do DFID’s efforts to shape its supplier market support value for money? | • Is DFID’s monitoring and influencing of its supplier market supporting improvements in value for money over time? • Does DFID’s management of its key suppliers and frameworks improve value for money? • Does DFID pay adequate attention to the need for competition and diversity in its supplier market? |

| 3. Learning: Does DFID capture and use learning and knowledge from its interactions with suppliers to improve its use of suppliers and its market-shaping efforts over time? | • Does DFID have a suitable mechanism for learning around supplier market shaping? • Is there evidence of learning? |

The review builds on the International Development Committee’s recent report on DFID’s use of contractors. It also updates the relevant findings of a wider 2013 ICAI review, DFID’s Use of Contractors to Deliver Aid Programmes. Our assessment of DFID’s progress against the recommendations from that report is summarised in Annex B. That review assessed DFID’s overall use of contractors as green-amber. It concluded that contractors can offer an effective option for delivering aid, but that DFID lacked a clear strategy on how to deploy the right contractors, including major, niche and innovative new entrant organisations, to best effect. Four of the recommendations of that review were within the scope of our current review, and Annex B shows progress on all four.

ICAI is currently undertaking a review of DFID’s approach to value for money in programme and portfolio management. Programme management and procurement are two of the most important drivers of value for money for the UK aid programme. The reviews are therefore complementary, selected to provide a holistic assessment of DFID’s approach to value for money.

Methodology

There are six methodological components to our review.

- We conducted a review of DFID’s procurement policies and strategies, analysing the quality of analysis and reasoning behind DFID’s procurement approach to assess its relevance and effectiveness. This included assessing how DFID oversees its suppliers, ensuring that they meet its expectations, and promoting value for money and diversity in its supply chain. We conducted in-depth interviews with DFID and reviewed relevant documentation, including 32 commercial delivery plans provided to us by DFID showing how commercial strategy is planned to be implemented across a range of country offices and other spending departments.

- We conducted process benchmarking, assessing DFID’s procurement approach against UK government guidelines and best practices, and considering how well DFID learns from, and responds to, examples of best practice.

- We conducted a financial and statistical analysis of DFID contract data to identify patterns and trends. In addition to reviewing the outputs of DFID’s management information system, we performed our own analysis of DFID’s data.

- We conducted a survey of 57 suppliers who had either attended or been invited to attend DFID’s 2016 supplier conference, to ascertain their views of DFID’s approach to shaping its supplier market. We also conducted in-depth interviews with a sample of both current and former key suppliers and participants in framework agreements, and a number of other interested parties and commentators. In addition, we held two roundtables with members of British Expertise and Bond, the UK NGO network, to gather views from both private sector organisations and NGOs.

- We carried out in-depth analysis of DFID practice in the following areas:

- Key supplier management: how DFID manages its relationships with its most important suppliers.

- Framework agreements: DFID’s use of pre-qualification processes to simplify procurement in particular thematic areas.

- Supplier engagement: how DFID communicates with its suppliers and potential suppliers, in order to promote competition.

- Working across country contexts: we explored how DFID’s relationship with local suppliers varies in different country contexts, particularly fragile states. We conducted desk-based case studies of Nigeria, India and Sierra Leone, as well as of DFID’s central Children, Youth and Education team as one of the highest spending central departments. For each case study, we conducted interviews with relevant DFID staff in-country and in the UK, as well as reviewing procurement data and relevant documents.

- We conducted a literature review, looking at past International Development Committee, ICAI and National Audit Office recommendations relevant to our review, and identified examples of best practice from other UK government departments and bilateral donors.

We acknowledge that firms and individuals involved in the preparation of ICAI reviews are also suppliers in the UK aid market. We have taken steps to control against any resulting risk of bias. For example, we have appointed a reference panel of distinguished procurement experts to peer review the methodology and the report.

Procurement has been a dynamic area of practice for DFID in recent years, with a number of reform initiatives. During 2017 the department has conducted its own review of its work with suppliers, leading to the announcement by the International Development Secretary on 3 October of further reform initiatives. It may take some years for new initiatives to influence the shape of the supplier market. In this review, we take account of recent changes in DFID’s procurement policies and systems under our first review question on relevance. Our second question, on effectiveness, is necessarily backwards-looking at the results of DFID’s procurement practices over recent years, and does not attempt to predict the results of ongoing reforms. The review should therefore be read as a snapshot of a situation that will continue to evolve in the coming period.

Background

The challenging context for DFID procurement

Over the five years to 2016-17, DFID let 700 contracts worth £5.5 billion to around 170 unique suppliers. The amount of procurement has increased steadily over that period (see Figure 1), reaching £1.4 billion or 14% of DFID’s £10.2 billion budget in 2016-17. It remains much less than the proportion of aid spent through multilateral organisations, developing country governments and NGOs. It is also below the proportion of some other bilateral donors, such as the United States Agency for International Development (29%) or Australia’s Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (24%).

Suppliers are usually commercial entities, but can also be charities, universities, or other not-for-profit organisations. It is the legal nature of DFID’s agreement with the recipient that determines whether entities are considered to be suppliers, rather than the legal form of the recipient.

Figure 1: DFID’s supplier expenditure over the last five years

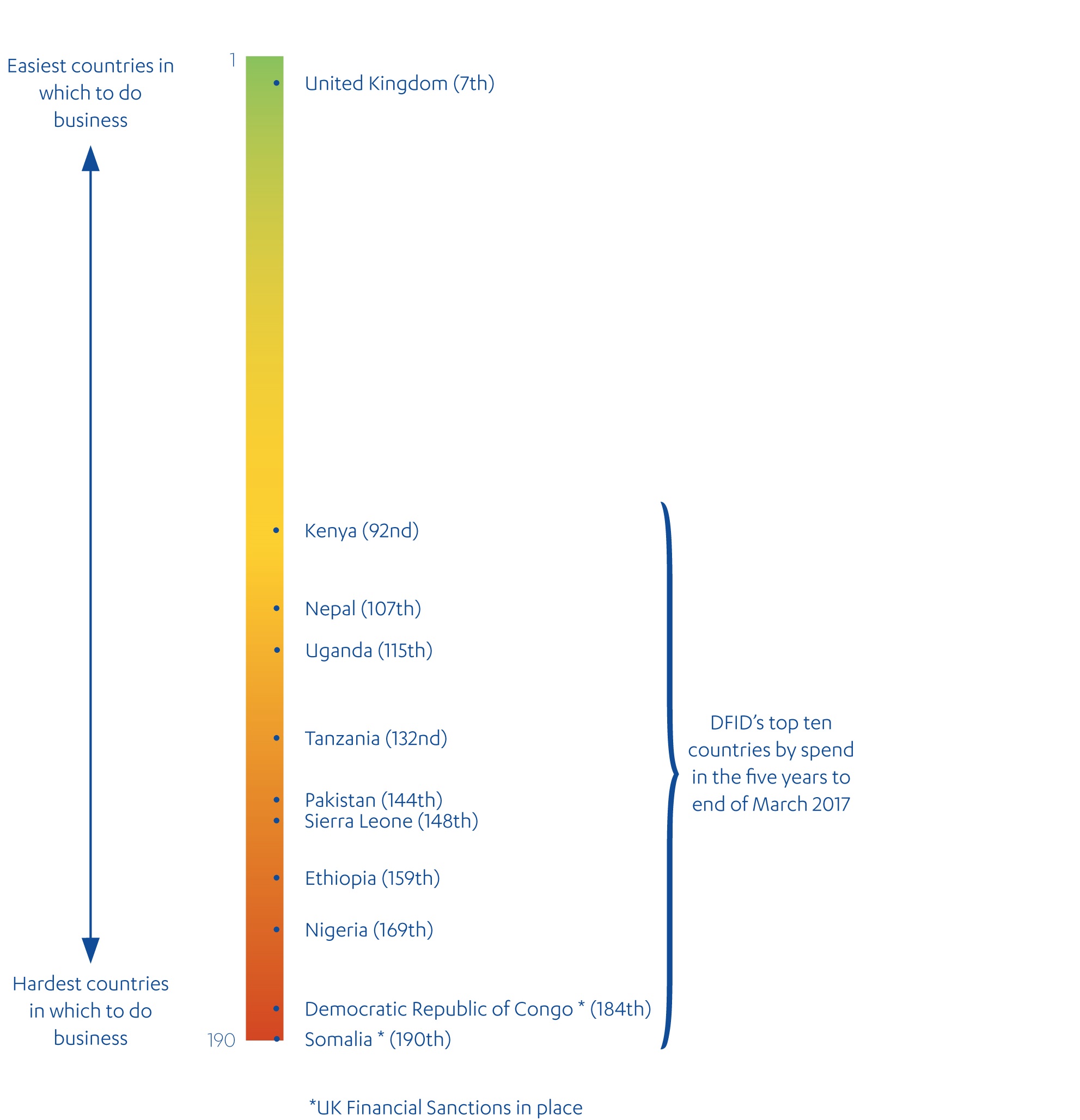

DFID’s procurement needs are complex and its markets diverse. It uses suppliers for a wide range of functions, such as the supply of goods (eg humanitarian or medical supplies), the management of grant mechanisms, construction projects and technical assistance to recipient governments. Its programming spans a wide range of country contexts and sector specialities, each offering different supplier markets and procurement challenges. DFID’s target countries are among the poorest in the world, with limited private sector capacity, and many are affected by conflict and insecurity. The risks involved in delivering complex aid programmes in difficult environments add substantially to DFID’s procurement challenges as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2: The position of DFID’s top ten countries by contractor spend, and the UK, in the World Bank’s Ease of Doing Business ranking

The procurement challenge has also been complicated in recent years by the rapid scaling up of the UK aid programme to meet the government’s 0.7% commitment. There has also been a high level of budget volatility, as DFID has responded to the domestic fiscal environment and shifting priorities of government.

Roles and responsibilities

The spending units in the delivery arms of DFID (country offices and central spending departments) through the senior responsible owner for each programme, and the central Procurement and Commercial Department, all have responsibilities for procurement at DFID (Box 2).

Box 2: Responsibility for procurement within DFID

Procurement and Commercial Department responsibilities:

- Ensuring DFID’s procurement complies with the law and UK government policy, and meets DFID’s procurement needs.

- Meeting cross-government targets, such as at least 33% of procurement value to be delivered through SMEs.

- Supporting senior responsible owners with day-to-day responsibility for procurement within country offices and other spending departments.

Senior responsible owner responsibilities:

- Developing the specification of DFID’s needs.

- Ensuring compliance with DFID Smart Rules on procurement.

- Managing smaller contracts directly, and working with the Procurement and Commercial Department on

- larger and more complex procurements.

DFID’s Smart Rules require that the senior responsible owner ensures that procurements with a value above the European Union (EU) threshold (£106,047) are commissioned for tender and awarded through the Procurement and Commercial Department, competed for in line with the EU Public Procurement Directives, and advertised in the Official Journal of the European Union (OJEU). Any exemptions (eg emergency procurement) must be agreed with the Procurement and Commercial Department.

The senior responsible owner must seek ministerial approval for all supplier contracts over £1 million. Cabinet Office approval is also required for contracts over £5 million. Procurements below the EU threshold should be undertaken by departmental procurement officers, or others accredited by the Procurement and Commercial Department, in line with the principles of the EU Public Procurement Directives of non-discrimination, equal treatment and transparency, under the direction of the senior responsible owner.

DFID’s procurement goals

Procurement is a dynamic area for DFID where the systems and processes have been evolving rapidly. An internal commercial capability review undertaken in 2015 found that DFID had undertaken “a significant commercial transformation programme” over the previous five years, strengthening commercial capability across the department and introducing a commercial leadership course for senior civil servants. However, it found a number of shortcomings in capacities and processes, which DFID has since been addressing.

As part of the reform programme, the Procurement and Commercial Department set a high-level vision and strategy to “support the ambitions of the department to become a world-class commercial organisation”. Its objectives are summarised in Box 3.

Box 3: Extract from DFID’s Procurement and Commercial Department ‘Vision’

First class commercial and procurement service within DFID

- Providing expert commercial advice to design and manage development programmes

- Robust assurance and governance: agile and flexible, with appropriate control, risk and contract management

- Service excellence, enabling the business to be ambitious and innovative in programme delivery

- Meeting the Government Commercial Standards as set out by Cabinet Office

Maximising and shaping markets

- Shaping both international and local markets alike

- Collaborates with other donors, multilateral organisations and across UK government to ensure opportunities are visible to the market, to include both local and UK SMEs

- Developing key markets that grow the supply base, build local sustainable capability and increase choices

- Creating greater assurance on market capability and capacity, increases competition and improved value for money

Our commercial influence and impact on the wider sector

- DFID understands the wider international development system and the impact of its commercial choices, not just on its own programmes, but on the work of others

- Developing ever-stronger links with the private sector and bring about economic growth

- Ensure policy decisions consider commercial effectiveness and drive sustainable commercial reform across the multilateral system

Increased scrutiny of DFID procurement

As aid spending has grown, the focus on DFID’s procurement practices, particularly its use of suppliers, has intensified. The 2013 ICAI report on DFID’s use of contractors, while positive about the use of contractors to deliver UK aid, pointed to the need for more sophisticated practices to manage the growing complexity of the portfolio.

In an April 2017 report on DFID’s use of suppliers, the International Development Committee, while noting progress, raised concerns that DFID did not have enough capacity to manage the full range of its commercial vision and lacked a sufficient understanding of how its procurement processes were shaping the supplier market. In particular, the Committee was concerned that certain procurement practices, including DFID’s use of framework contracts, were working against the department’s stated aim of expanding market access for smaller suppliers. The Committee also published a report that was highly critical of alleged unethical practices by one of DFID’s top suppliers, Adam Smith International. These and other concerns led to a forensic investigation by DFID, which, at the time of writing, was still underway.

In the face of this scrutiny from Parliament and the public, the International Development Secretary ordered the department to undertake a review of DFID’s work with suppliers. In January 2017, she wrote to the International Development Committee to explain the priorities of this review, saying:

“There should be no room for excessive profiteering or unethical practices. All of DFID’s suppliers and partners need to be fully open and transparent with UK taxpayers about where their money is going and how it is being spent to meet development outcomes. They need to uphold the highest standards and be held to account for those standards. DFID needs to reduce its reliance on a limited number of suppliers, and encourage healthy competition in what is often a challenging development sector.”

On 3 October 2017 the International Development Secretary announced a number of actions resulting from this review. Some of these relate to DFID’s market-shaping activity and are considered in the relevant parts of this report insofar as it is practical at this early stage.

Findings

This section sets out the findings of our review. We first assess relevance – whether DFID’s approach to shaping the supplier market is appropriate, given the objectives and priorities of the aid programme. We then turn to effectiveness – whether DFID’s market-shaping interventions are successful in driving better value for money. Finally, we assess DFID’s processes for capturing and using learning to improve its efforts to shape the supplier market over time.

Does DFID’s approach to shaping its supplier market support the objectives and priorities of the aid programme?

From 2015 DFID moved from conservative to more ambitious market-shaping goals

DFID has been making a concerted effort to strengthen its procurement function since 2008, when a commercial capability review by the Office of Government Commerce – the predecessor to the current Government Commercial Service and Government Commercial Function – raised concerns regarding its overall vision and approach, the quality of its management information, and its risk management processes. DFID responded to this assessment with a process of reform that has included a sustained effort to build commercial capacity and to strengthen procurement systems and processes. In our 2013 report, we found that the reform plan was not well prioritised and that there were a number of gaps. Since then, the reform strategy has continued to evolve.

Until 2015, market shaping was not a significant part of DFID’s procurement reforms. The department took a relatively conservative approach to market shaping, concentrating on core procurement processes, the management of key suppliers, and building capability within the department, rather than on measures to strengthen the supply base.

This caution was common at the time among Whitehall departments. In 2016, the Public Accounts Committee reported that commercial capability reviews of the major procuring departments had found that they were “overwhelmingly focused on the procurement process at the expense of crucial market shaping and contract management activities”.

Market shaping is clearly recognised in UK government guidance as both appropriate and consistent with regulations if it helps to promote better value for money over time. Arm’s-length competitive tendering, combined with effective market engagement, are key ingredients in delivering value for money in supply contracts in public procurement, but research and evaluation evidence acknowledges that market-shaping initiatives may be required in addition.

Office of Government Commerce guidance from 2009 encouraged departments to develop a better understanding of how their own purchasing power and procurement practices influenced markets and to take corrective action as required. The National Audit Office has produced a Good practice contract management framework that endorses ‘market making’ when appropriate to stimulate competition and build market capacity.

Since 2015 DFID began to increase its ambition on market shaping. A commercial vision, adopted in 2015-16, sets out DFID’s aspiration to “take responsibility for maximising market responses”. Market shaping was specified as one of three overall objectives (see Box 3), in order to expand the size and diversity of its supply base. The market-shaping objectives include:

- ensuring opportunities are more visible to the market, including to SMEs and local suppliers in partner countries

- developing key markets that grow the supply base, build sustainable local capability and increase procurement choices

- creating greater assurance on market capability, increasing competition and improving value for money.

Box 4: Building procurement capacity across DFID

DFID has supported its Commercial Reform Plan with a significant increase in the resources allocated to procurement. The number of approved posts in procurement increased from 41 in April 2011 to 95 in April 2016 and 123 in April 2017 (including 27 commercial delivery managers attached to spending departments), and the Procurement and Commercial Department forecasts a total of 136 by April 2018. As well as recruiting staff with specialist procurement skills, DFID has provided additional training for non-specialists, and all Senior Civil Servants have been given commercial awareness training. The increased capacity includes the establishment of a specialist Market Creation Team.

A comprehensive market-shaping approach has begun to emerge

Since the commercial vision was adopted, DFID has progressively articulated its approach to market shaping. In 2016, the Procurement and Commercial Department developed an unpublished Market Creation Plan, with detailed objectives around increasing the number of suppliers (including SMEs and suppliers from developing countries), improving the choice of delivery channels, and achieving greater visibility over costs and profits. The plan included a brief diagnosis of challenges that may discourage participation by new or small suppliers, although these barriers were not analysed in any depth. Challenges cited include:

- a lack of visibility over future procurement opportunities (‘pipeline’) to facilitate future planning by suppliers

- the size and complexity of DFID programmes

- the length of time involved in procurement

- working in fragile states, DFID’s fiduciary risk policies, and the use of payment-by-results contracting, which may increase supplier risks.

The Market Creation Plan combined ongoing and scheduled activities and proposals for activities for which approval would be sought at a later date. Ongoing initiatives included:

- simplifying the pre-qualification process to make it quicker and less costly

- improving pipeline planning

- increasing early market engagement

- improving market analysis

- establishing the Key Supplier Management Programme

- creating more opportunities for SMEs

- commercial training of senior civil servants and senior responsible owners

- improving communication with suppliers, including on issues such as fair and reasonable profits, treatment of subcontractors, and ethical standards.

Planned activities included:

- increasing the division of contracts into smaller lots to increase access for smaller suppliers

- measures to improve market intelligence and supply chain visibility

- stronger ethical and transparency standards for suppliers

- the introduction of open-book contracting (see Box 6) to provide greater visibility of suppliers’ costs and help mitigate the impact of potential supplier dominance.

Since 2016 DFID has been working to implement the Market Creation Plan; Annex C includes the full list of activities and summarises their status in September 2017.

DFID’s activity has included work to improve communications with suppliers, to publicise future work, and to gain input from suppliers. Since 2013, DFID has held a conference each year open to all suppliers, with an agenda focused on generic issues relevant to suppliers. The 2016 conference, for example, included sessions on DFID’s expectations of suppliers and its market creation work. In addition, DFID has established a system of early market engagement events for potential suppliers, each focused on a forthcoming DFID project or programme of work, using remote access facilities to enable participation from both UK-based and in-country suppliers. In 2016-17, DFID held 61 such events, with 2,167 registered attendees from 1,198 organisations.

The Market Creation Plan and the increase in communications with suppliers show a clear ambition by DFID to identify the barriers that limit or discourage suppliers from competing for DFID business. It identifies a broad range of concrete actions to address these barriers by both procurement and programme staff. While some of the activities have been completed, many are still ongoing, and the third and final phase of the plan has yet to be finalised. The depth of analysis behind the initiatives is lacking in some areas, due in large part to weaknesses in DFID’s management information systems that we explore below. Some of the key initiatives require further design work, and will need to be tested in practice and refined before DFID can be confident it has found the appropriate approach. Nonetheless, the establishment of a five-person Market Creation Team with expertise from the private and public sector, and with the development of the plan, has provided welcome impetus and structure to DFID’s market-shaping work, and a solid framework for moving forward.

DFID’s supplier review is giving further impetus to a number of the activities set out in the Market Creation Plan. For example, pipeline planning and visibility were identified in both our supplier consultations and in DFID’s own documents as key constraints on supplier participation. Knowledge about the pipeline is helpful for suppliers so they can plan for preparing bids and resourcing projects, and decide where best to invest their efforts. Improving this knowledge is a challenging area to address in the short term because of weaknesses in DFID’s information systems (see para. 4.100). DFID reports that it had begun implementing an improved pipeline from August 2017 and will implement it across the department from October 2017.

DFID has been developing market-shaping strategies in particular sectors and countries

DFID’s procurement challenges differ substantially across its market segments and many of the solutions will need to be identified at this level. To support this, DFID has developed a network of commercial delivery managers attached to spending departments – both in country offices and in UK-based departments responsible for centrally managed programmes. These managers work with programme teams to develop and implement programmes including those involving commercial suppliers. That work includes elements of market shaping, for example supporting offices in engaging with international and local supplier markets or shaping the local supply market and developing its capacity to support DFID programmes.

With this additional resource, DFID has been developing commercial strategies for particular sectors and countries. For example, it now has a commercial strategy in health, which until recently was DFID’s largest sector by expenditure at £1 billion or 13% of UK bilateral aid. Health spending uses a variety of channels, including multilateral organisations, governments, NGOs and projects delivered by suppliers. The strategy offers a market and supply chain analysis, so as to identify opportunities for improving value for money and collaboration between DFID and its different types of delivery partners. It identifies a number of opportunities for action, including: market shaping to support product innovation and reduce global pricing; encouraging greater supply chain integration and exploring changes in delivery routes; improved management information; and developing local markets for service delivery and supply chain support. DFID has already achieved some success in this area (Box 5) but we understand that implementation of these initiatives remains at an early stage.

Box 5: GAVI, the vaccine alliance – market shaping at the global level

Development commodities, such as vaccines, bed nets or humanitarian supplies, represent only a minor share of DFID’s procurement. However, some of its multilateral partners are major purchasers, and their procurement activities have a significant impact on global markets and the prices at which developing countries can access such commodities.

For example, GAVI, the vaccine alliance, was formed in 2000 as a public-private partnership to improve access to immunisation in developing countries. Prior to GAVI, international development agencies purchased vaccines in an unplanned way to meet the needs of individual countries. GAVI has successfully pooled demand for vaccines across developing countries through a collective procurement mechanism. This lowers prices for developing countries, while providing greater certainty for manufacturers, encouraging them to produce more vaccines. For example, annual global production of the pentavalent vaccine (designed to protect children against five childhood diseases) has increased from 20 million to 400 million doses. This has resulted in a more diversified market, with more manufacturers based in developing countries. GAVI is able to purchase the vaccine for as little as US$1.15 per dose, compared to over US$30 in the US market. DFID was instrumental in the founding of GAVI and remains engaged in its market-shaping activities.

DFID provided us with 32 commercial delivery plans which are now in place for country offices, including two of our three country case studies (India and Nigeria), and other spending departments. Some include useful analysis of the local supplier market, acknowledging market barrier for local suppliers and the risk in various countries of an over-reliance on a small pool of suppliers, particularly for specialist functions, and proposing a range of measures to address these. A few of the plans, such as Afghanistan, India, and Nigeria, contain a clear strategy for shaping the market and strengthening the supply chain at country level.

For example, the Nigeria plan notes that, while programmes are generally performing well, too few suppliers are winning tenders and there is a growing risk of sole suppliers for niche programmes. It commits the country office to broadening the supplier base through more effective communication of opportunities and by identifying ways to promote the participation of Nigerian firms as subcontractors, consortium partners, or as suppliers of specialist services. Our next review will include more detailed country case studies.

Partly because they predate the Market Creation Plan, the majority of country-level commercial delivery plans do not contain a fully-fledged market shaping strategy. To guide its actions, DFID has begun using a market segmentation tool. The purpose of the tool is to provide a systematic basis for classifying markets and programmes by reference to the value of DFID spend, the importance for DFID’s strategic aims, risk and complexity. DFID plans to use the classifications to guide its approach to managing each market and programme, analyse conditions in particular segments of the market and identify corrective actions.

DFID is yet to settle on a clear approach to promoting the participation of local suppliers

During our interviews with DFID staff, we heard mixed views on the importance of participation by local suppliers in its priority countries. Some thought that developing the capacity of local private sector suppliers represents a development outcome in its own right. Others believed that DFID’s obligation is to ensure the highest quality programme delivery, irrespective of the nationality of the supplier. There were concerns that measures to promote local suppliers – such as letting smaller contracts – would increase DFID’s administrative costs and thereby detract from value for money in other ways.

DFID’s strategy documents nonetheless identify local participation as an objective. Local suppliers already perform an important role as subcontractors to the prime contractors appointed by DFID, and can offer advantages over international suppliers such as lower costs and better local knowledge and understanding. DFID recognises that there may be scope for it to do more, and that increasing local suppliers’ capacity may be one way of improving access to valuable local knowledge and increasing competition for contracts in the future. Some of DFID’s country commercial strategies include measures to help local suppliers, but these are at an early stage of development.

As part of its effort to understand the barriers to local firms from partner countries, DFID commissioned a study investigating access to market, which was completed in April 2017 (see para 4.59 for our own analysis of the data). The report suggested that greater use of local suppliers would provide “better insights into specific local contexts” and better long-term development outcomes. However, it also found that local firms generally lacked the capability to win DFID contracts directly and that active work would be needed to enable them to compete.

Given the government procurement regulations and DFID’s obligation to maximise value for money in each of its programmes, DFID cannot set an overall target on the participation of local suppliers, particularly as prime contractors. However, through its processes DFID can encourage prime contractors to use local suppliers. Individual business cases can identify whether there is a development benefit to using suppliers, which is then specified in tender documents and taken into account in the procurement process. For example, DFID Sierra Leone described to us how one of its projects included a requirement on the part of the prime contractor to provide apprenticeships for local people. Furthermore, DFID can take measures to reduce barriers to entry, and encourage its prime contractors to engage local suppliers on terms that enable them to develop their capacity over time.

We therefore take the view that DFID could develop a more systematic approach in this area. This would help to address the concern rightly raised in the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) peer review process that the UK aid market remains dominated by UK firms (a point we address further on). As more of DFID’s partner countries approach middle-income status and the prospect of graduating from development aid, the scope to build local supply capacity is likely to grow. DFID’s partner countries will increasingly fund national development initiatives from their own resources and will need a more mature private sector (including both first and second-tier suppliers) to support them. We therefore welcome the proposal in the as-yet unapproved third phase of DFID’s Market Creation Plan to run country office pilots to stimulate and develop local suppliers.

DFID is building its capability to assess suppliers’ costs and whether they are making excessive profits

One of the concerns expressed by some commentators is that DFID’s larger suppliers may be making excessive profits, at the expense of UK taxpayers and the intended beneficiaries of UK aid. The International Development Secretary has stated that “there should be no room for excessive profiteering or unethical practices”, and that suppliers needed “to be fully open and transparent with UK taxpayers about where their money is going and how it is being spent”.

Information on suppliers’ costs and profits is particularly important where there are limits on the power of competition to secure value for money in procurement. In theory, ensuring fair and open competition within a competitive procurement process should ensure fair profits, under certain conditions. However, in practice, these conditions do not always hold true, particularly in the international development field. Most of DFID’s procurement is for the delivery of complex, multi-component programmes over a period of years, rather than for the purchase of goods or services with an established market price. This can lead to an imbalance of information between DFID and its suppliers – particularly larger suppliers with a track record of delivering DFID programmes, who gain experience in winning DFID contracts. Such firms have advantages over new entrants and the potential to use their market power to increase their profits.

The challenge does not end with the tendering process. DFID needs to ensure that the package of services delivered by the supplier matches that offered in the tender. As the Public Accounts Committee has pointed out, performance monitoring through the life of the contract is as important as the tender in securing value for money. The commercial terms of the contract may also need to be varied over the life of the programme, owing to changes in conditions or to DFID’s objectives. Without the benefit of competition, the asymmetry of knowledge between DFID and its suppliers is even more pronounced after the contract has been signed and the supplier is in place.

We stress that these challenges are inherent to procurement in the development field, and, indeed, to many other areas of public procurement, rather than a result of any flaws in DFID’s procurement system. However, these challenges may be exacerbated by certain DFID practices, such as conducting larger projects or asking suppliers to bear more risk, which the evidence suggests tend to advantage established suppliers.

There is no single solution to this challenge and DFID is currently exploring a range of possible initiatives. One is a range of measures to increase competition. The Key Supplier Management Programme is another part of the solution. It enables DFID to manage its major suppliers at the portfolio level, as well as within individual programmes, so as to improve communications, set clear expectations and, in principle, develop a shared sense of mission.

DFID is also moving in the direction of increasing transparency over suppliers’ costs and profits. Transparency is an important tool for purchasing authorities to help manage their supply chain. It can be promoted through a range of techniques known under the general term of ‘open book’. Public sector bodies use open-book accounting with the aim of gaining a better understanding of the specific costs and profits of their major contracts. If implemented well, open-book techniques are among the tools that can build mutual understanding and trust between government and suppliers, and lead to increased value for money. It is also in the public interest to have greater transparency over the level of profit that government suppliers are able to achieve. When combined with other information, this provides an assurance that the system of public procurement is working properly. Open book has been recommended by the Public Accounts Committee and advice on its use has been issued by the Crown Commercial Service.

Box 6: Open-book techniques in procurement

Open book refers to a set of measures in public procurement intended to increase purchaser understanding of supplier costs and profits. It removes one source of information imbalance between the parties, and can lead to improved procurement outcomes and better contract management.

Open-book accounting, according to the National Audit Office, is “a particular type of supply-chain assurance where suppliers share information about the costs and profits of a specific contract with their client.”

Open-book contract management goes a step further to include not just sharing of information but joint

working to manage costs and improve value for money.

In the past, DFID had no reliable means of assessing what level of profit its suppliers were achieving. It lacked detailed information on the costs of inputs. Its suppliers used a range of business models, making it difficult to compare margins across contracts or suppliers. The fee rates charged by suppliers for technical assistance programmes encompassed margins for working capital, intellectual property and level of risk, as well as profit, making them difficult to compare.

Since 2016, DFID has begun introducing open-book accounting rights into its contracts to increase its understanding of supplier costs and margins. This imposes contractual requirements on suppliers to share detailed financial information enabling external scrutiny. It provides a basis for assessing whether suppliers have delivered on their commitments, whether the pricing assumptions underlying the original tender have proved accurate, and whether there are opportunities to improve efficiency. A letter from the International Development Secretary in December 2016 informed suppliers that DFID would be increasing its scrutiny of supplier spending and strengthening checks of fees and expenses, alongside other areas such as tax status and conflicts of interest. While DFID’s contractual rights to ask for information on supplier costs and profits has existed for at least ten years, we find that DFID has only recently acquired the necessary compliance capacity to take forward open-book accounting on a systematic basis.

DFID’s standard terms and conditions also require suppliers to declare forecast profit margins at the end of the inception phase of each programme. Measurement and comparisons of costs and profit is notoriously challenging. DFID has required suppliers to provide basic fee rate information for many years. Since November 2016, however, DFID has required bidders to provide more detailed information on fee rates (including profit margins) and other project expenses using a standard template to enable more effective analysis. Using this information, DFID has compiled a database of suppliers’ fee rates and used this to begin benchmarking suppliers’ costs. Early signs are that rates are being kept in check, although further action in this area is expected.

A more in-depth open-book technique is open-book contract management. This goes beyond open-book accounting into collaborative working with suppliers to control costs, improve processes and create value throughout the lifecycle of the contract. The Crown Commercial Service issued guidance on its use in May 2016. The guidance advised that open-book contract management should only be applied fully for more complex contracts, and instructed departments to assess where best to use it and to begin mobilising resources to implement it by July 2016.

At the time of our review, DFID was looking to pilot a more extensive open-book contract management approach. DFID told us that it still had to define its exact objectives for open-book contract management and was consulting with other departments to determine its approach.

DFID also explored the use of what it terms ‘a supplier profit clause’ in contracts as part of its supplier review. The clause will give DFID the right to trigger discussions with the supplier, should the supplier’s profit margin rise during programme delivery above a pre-determined level. DFID has announced that it is applying this provision to all new tenders from 1 September 2017, to all contract extensions as they arise, and over the coming months to existing high-value strategic contracts.

While these measures seek to advance the Secretary of State’s objective of controlling “excessive profiteering”, the effects on the shape and structure of DFID’s supplier market are difficult to predict at this stage. They may have the effect of reducing the level of competition for DFID contracts – in the UK and beyond. Alternatively, by engaging directly on profits, they may reduce the incentives on suppliers to limit costs – a well-known problem with ‘cost-plus’ contracting methods. It will therefore be important, as DFID proceeds with this approach, to consider how the measures are likely to work as a whole, to communicate clearly with suppliers on what use it intends to make of the profit clause, and to monitor closely the impact on suppliers’ perceptions and behaviour.

Box 7: Do other donors or UK departments try to control supplier profits?

Our analysis of the practices of other donor organisations found that there is no standard approach

towards controlling supplier costs and profits.

- Our analysis of the practices of other donor organisations found that there is no standard approach towards controlling supplier costs and profits.

The United States Agency for International Development (USAID) uses ‘cost-plus’ contracts in which contractors are reimbursed for the costs of delivery, and then receive an additional fee that is negotiated at the beginning of the contract. USAID provides guidance to its staff on how to analyse the costs and profit margins in supplier bids, to assess if the projected price is fair and based on reasonable assumptions, and whether or not the proposed cost reflects reasonable economy and efficiency. - Australia’s Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (DFAT) prescribes fee rates for consultants through its Aid Adviser Remuneration Framework. All consultants engaged either directly or indirectly under Australian government contracts are paid in line with this framework. Guidance states that DFAT staff should also check advisers’ past performance before determining the remuneration offer. We note that DFAT is currently undertaking a review of the framework.

- Rather than prescribe a specific contracting method, the UN procurement manual states that consideration should be given to whether the supplier will be paid a fixed fee or ‘cost-plus’. The manual notes that ‘firm fixed price’ contracting is more commonly used: “It places on one hand maximum risk of increased costs on the Vendor and on the other hand maximum incentive on the Vendor to control costs and develop innovative solution for the UN. However, […] there is greater risk that the Vendor may ‘cut corners’ in order to maximize its profit.” On the other hand, “[Cost-plus …] minimizes the Vendor’s incentive to ‘cut corners’, but provides little incentive for the Vendor to minimize costs.”

In UK government practice, the clearest example of a government body controlling profits is the Single Source Regulations Office (SSRO), a non-departmental public body sponsored by the Ministry of Defence (MOD) to monitor the UK government’s procurement of ‘single source’, or non-competitive, military goods, works and services. The SSRO sets a baseline profit rate for contracts placed under Single Source Contract Regulations. In March 2017, it was announced that the baseline profit rate for 2017-18 for contracts placed under these regulations would be 7.46% compared with 8.95% for the previous year. However, contractors generally enjoy a profit rate well in excess of 10% after all adjustments have been made. As stated in the report relating to the establishment of the single source framework, “in exchange for a fair profit for industry, the new framework will provide the MOD with far greater transparency, helping us to investigate whether suppliers are being as efficient as possible.”

Conclusions on relevance

While market shaping was not the main priority when DFID began its procurement reforms, we are encouraged to see that DFID has now set itself more ambitious goals. It has recognised the importance of promoting greater competition and diversity in its markets, and is exploring – and beginning to implement – measures to bring this about. DFID has begun to develop commercial strategies for particular countries and sectors, and a market segmentation tool, to analyse conditions in particular segments of the market and identify corrective actions. Its Market Creation Plan, Key Supplier Management Programme and use of framework contracts are also potentially useful tools for shaping the market that are consistent with UK government guidance.

However, some key aspects of DFID’s approach to market shaping are still emerging, including in relation to DFID’s 2017 supplier review. DFID’s plans include some complex new initiatives that may affect the market in unpredictable ways. These initiatives will inevitably require fine tuning as they are implemented and used in practice, and it will be important for DFID to monitor impacts closely and make corrections where necessary.

Overall, we are pleased to see that DFID has increased its level of ambition and put in place a range of positive measures on market creation, although we also find that its approach is still at a relatively early stage of maturity and will need to be tested and refined over time. With the information currently available, we have scored DFID a green-amber score for the relevance of its approach, reflecting a significant increase in activity in this area and an overall positive direction of travel.

Do DFID’s efforts to shape its supplier market support value for money?

This section assesses whether DFID’s procurement practices support its goals of improving competition and diversity, and whether its market-shaping activities to date are having a positive effect. As a starting point, we note that any measures taken by DFID in this area will take some years to affect the shape of the market.

Most of DFID’s market-shaping initiatives have been in development since 2015, making it too early to judge their impact. Some elements, however, such as framework contracts and key supplier management, date back further, although we acknowledge that they are in the process of reform or refinement leading up to and following DFID’s 2017 supplier review.

DFID’s market is not overly concentrated generally, but it faces challenges in particular sectors and countries

To assess DFID’s success in achieving competition and diversity in its market, we looked at several areas:

- The number of bids received by DFID when putting contracts out to tender.

- The level of market concentration (that is, whether or not the number of suppliers suggests a lack of competition).

- Barriers that might discourage new entrants to the market.

- The level of participation by SMEs and suppliers in developing countries.

In February 2017, DFID informed the International Development Committee that comprehensive data on the number of bids received for each tender was only available from 2015-16. During this year, the average number of bids per contract was 2.5, which DFID considered “not sufficient”. For 2016-17, DFID’s management information shows a higher figure of 2.9 for 2016-17, which is an improvement over just one year, but still short of the target of four.

A high level of concentration in a market – that is, dominance by a few large firms – may suggest that competition is weak, and may in itself discourage new entrants. The picture is more complex than that, however. Spending through larger suppliers may represent good value for money if they are able to achieve economies of scale and reach more beneficiaries per pound spent. Conversely, a lack of concentration at the aggregate level does not in itself guarantee that competition is strong. For example, there may still be strong incumbency advantages that make it difficult for new firms in the market to challenge existing suppliers.

DFID’s management information system collects a range of data about DFID’s suppliers, including their country of registration and whether they are part of the Key Supplier Management Programme. The data relates mainly to prime contractors; DFID collates little information about participation further down its supply chains (ie as subcontractors). Due to various errors and anomalies, the data that we have seen is not strong enough to allow detailed analysis of the market. We can, however, identify certain overall trends in the aggregate data reported by DFID.

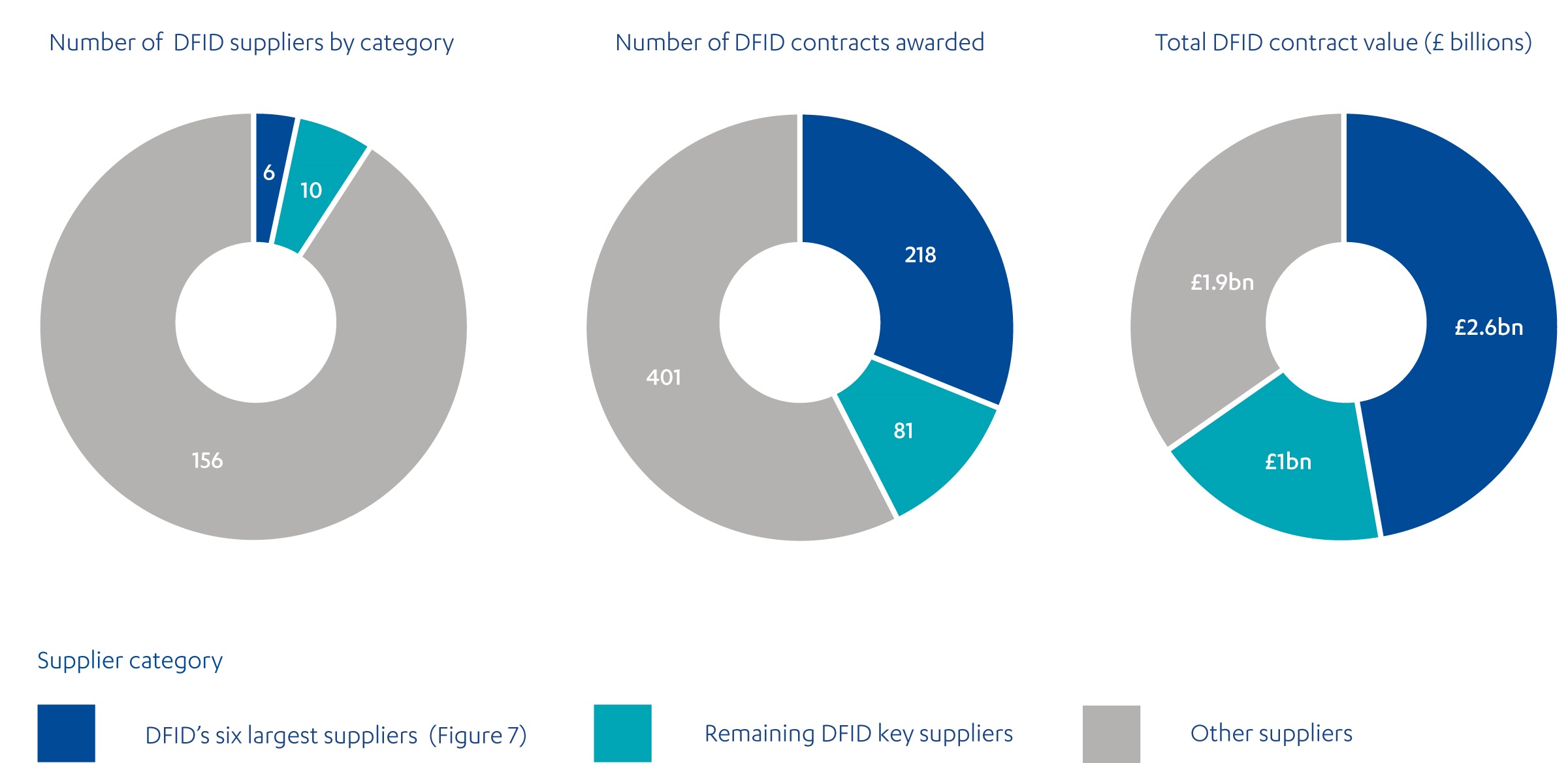

As shown in Figure 1 in para. 3.2, between 2012-13 and 2016-17, DFID’s expenditure through suppliers has nearly doubled. Over this period, DFID awarded 700 contracts with a total value of £5.5 billion to around 170 suppliers. Within this group, six suppliers accounted for 45% of DFID’s total contract value, with an average contract size of just over £12 million (see Figure 3).

Figure 3: Analysis of suppliers by category from 2012-13 to 2016-17

To assess whether these figures suggest undue concentration, we drew on the guidelines for market investigations published by the UK competition regulator. The guidelines note that robust findings on whether or not features in a market are harming competition require detailed understanding of how the market operates. Factors to be considered include not just market share, but also other factors such as the legal and regulatory framework and the outcomes that are achieved, in terms of prices, profits, quality, and innovation.

For assessing market share, the Competition and Markets Authority uses a measure of market concentration known as the Herfindahl-Hirschman Index, or HHI. The lower the score, the less concentrated the market, with a score of 1,000 or above considered as indicating a concentrated market and a score above 2,000 indicating a highly concentrated market. Based on DFID contract award data, we estimate the HHI of DFID’s supplier market as a whole to be under 500, which confirms that at the aggregate level the market is not overly concentrated.

The picture is likely to be considerably more complex when we consider that DFID’s market is segmented across different countries and different goods and services. Analysis by DFID’s Procurement and Commercial Department has found that, in contrast to the aggregate, the supplier market is highly concentrated within some sectors and individual countries where conditions for smaller and local firms are challenging. DFID sees this as evidence that further work is needed to open up markets and increase competition in the countries where it is working.

Some aspects of DFID’s procurement practice may discourage new entrants

Another important area to assess is whether aspects of DFID’s procurement practice might inadvertently discourage or create barriers for new entrants. For example, the choices that DFID makes about the size and complexity of its contracts and the level of risk that suppliers are asked to bear (particularly in conflict-affected environments) are likely to influence who is willing and able to bid.

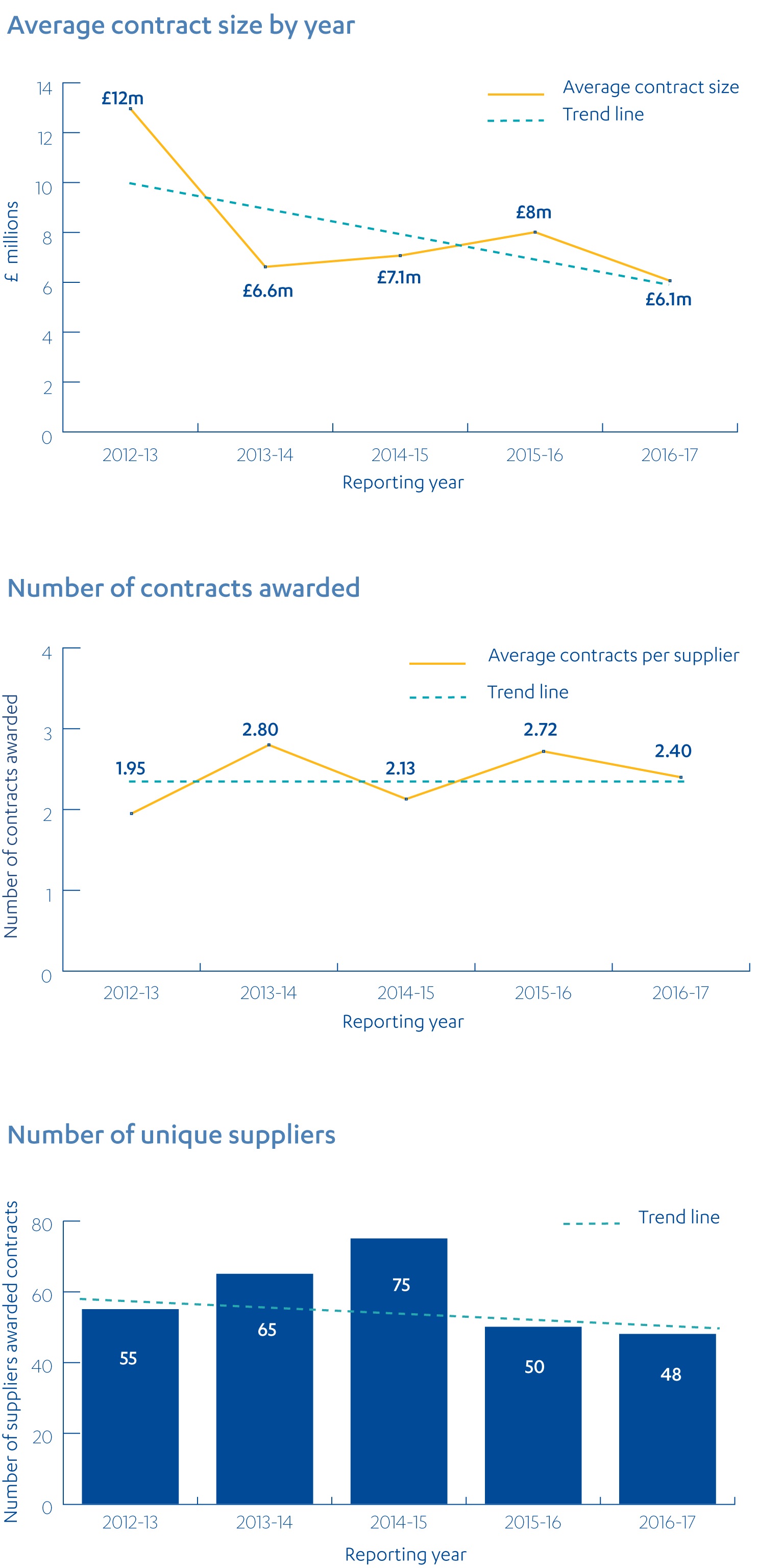

One of the concerns expressed to us by stakeholders was that the unit size of DFID contracts had increased as the UK aid budget scaled up towards the 0.7% commitment, and that this, in turn, had advantaged larger suppliers. However, the aggregate figures do not show this (see Figure 4). Based on the current value of contracts awarded in each year (ie taking into account both the initial award value and subsequent variations), the average size of contracts in fact declined between 2012-13 and 2016-17. The average number of contracts going to new suppliers also increased up to 2014-15, followed by a decline. DFID explained that this is due, in part, to the removal of self-employed consultants from the supplier database. DFID informed us that its total number of suppliers increased by 36% from 2011 to 2015. DFID has also introduced some lotting of contracts as part of its SME Action Plan (see below).

Figure 4: Trends in contracting from 2012-13 to 2016-17

In addition to the size of contract, the level of risk associated with DFID contracts is perceived by stakeholders to have increased, due to a number of factors: the increased proportion of the aid budget spent in insecure environments; tighter rules on fiduciary risk management; and increased use of various versions of payment-by-results contracting. Our analysis suggests that increased expenditure in fragile states is unlikely to be a significant factor on its own, as DFID’s preferred delivery channels in conflict situations tend to be multilaterals and NGOs. Its use of private sector suppliers in fragile states is still quite limited (see Box 8). The effects of risk transfer to suppliers are more difficult to assess, but we acknowledge the widespread view across all categories of supplier that the level of risk transfer in DFID contracts has increased over time.

Box 8: DFID makes limited use of suppliers in fragile states

DFID is committed to spending at least half of its budget in fragile and conflict-affected states. This commitment has led to a concern in some quarters that the resulting higher-risk profile for DFID programmes would favour larger suppliers, driving more concentration of the market.

This turns out not to be the case. In the most insecure environment, DFID makes only limited use of suppliers, preferring to deliver through multilateral partners and NGOs. For example, in Yemen, the total country budget for 2017-18 is £50 million, with the only current contract for the independent monitoring of the Yemen programme (£2.8 million over five years) by the British Council. In Syria, DFID holds four contracts with a total value of £13.8 million, against a total budget for 2017-18 of £135 million. In Sudan, there are no supplier contracts.