The changing nature of UK aid in Ghana

Score summary

UK aid in Ghana is aligned with both governments’ strategic objectives to transition their development partnership beyond aid. UK aid offers relevant and mostly effective responses to Ghana’s development needs, but results may not be sustainable once the UK shifts from direct financing of services to technical assistance and other forms of support.

After two decades of economic growth, Ghana has gone from relative poverty to become one of West Africa’s wealthiest countries, but considerable development challenges remain. As Ghana’s economy transforms, its long-standing partnership with the UK is also changing, away from traditional bilateral aid to a broad-based development partnership aimed at mutual benefit.

The priorities guiding UK aid in Ghana in the 2011–2019 review period are aligned with both the UK aid strategy and Ghana’s Beyond Aid strategy. These include: 1) strengthening governance, 2) promoting prosperity through economic growth, and 3) improving human development outcomes by strengthening social sectors. Over the review period, DFID’s governance portfolio shifted focus to anti-corruption, tax policy and administration, and oil and gas revenue management – all central to Ghana’s ability to finance its own development. Towards the end of the period, key UK government departments were working together in a cross-departmental approach to support Ghana’s economic development. Social sector programming targeted Ghana’s poorest and most vulnerable, and focused on regions lagging behind, in line with UK aid’s commitment to gender equality and leaving no one behind. However, as the UK reduced bilateral aid, decisions on where to phase out direct financial support weren’t always based on sound analyses of how it would affect service delivery for the poorest.

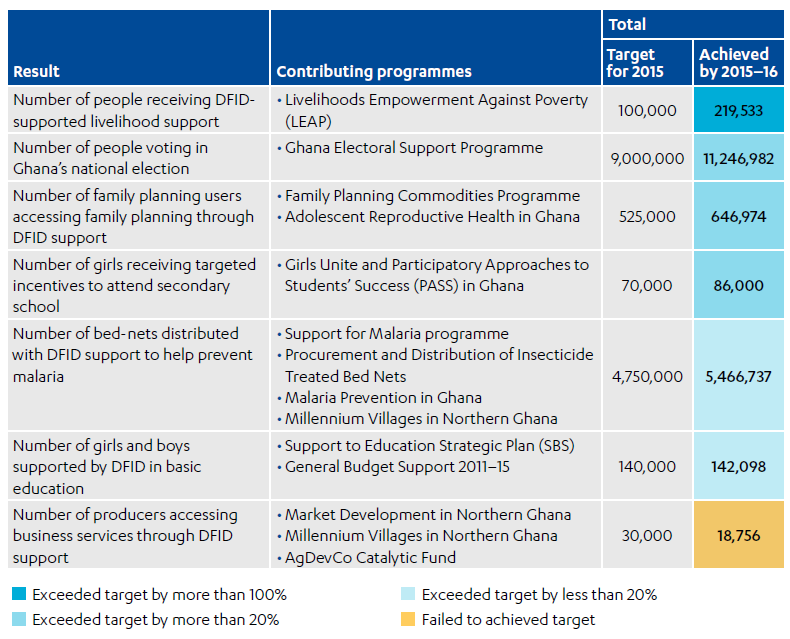

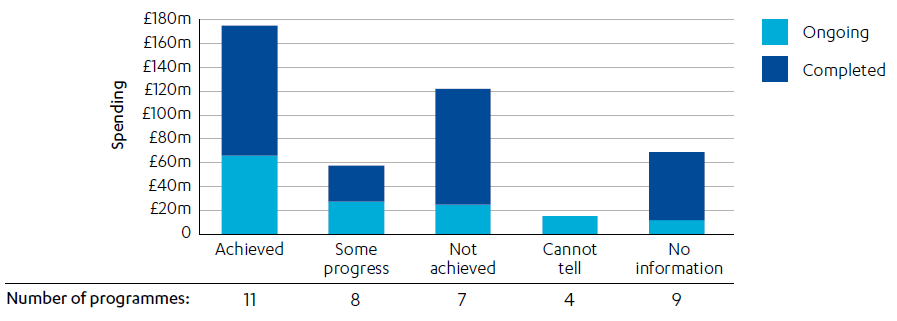

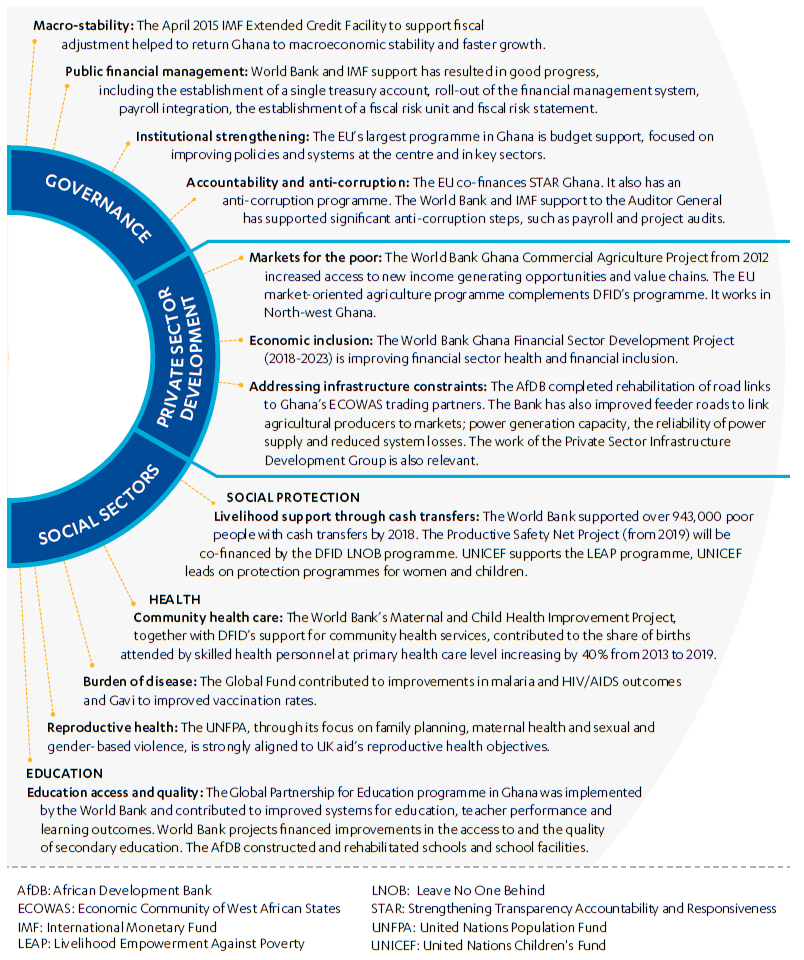

DFID mostly met or exceeded the output targets set in programme documents and in the results framework for the 2011–2015 Operational Plan. However, this results framework covered less than half the spending during that period, while no results framework was stipulated in the Business Plan for 2016–17 to 2019–20. By conducting our own contribution analysis, we found, positively, that UK aid funding has often made important contributions to Ghana’s development results, particularly through its social sector programming. As part of transitioning the partnership beyond aid, UK aid to Ghana is increasingly channelled through multilateral partners such as the World Bank, IMF, African Development Bank and UN agencies. UK-funded multilateral programmes contribute to UK aid objectives, but the UK does not sufficiently maximise its influence over programming choices.

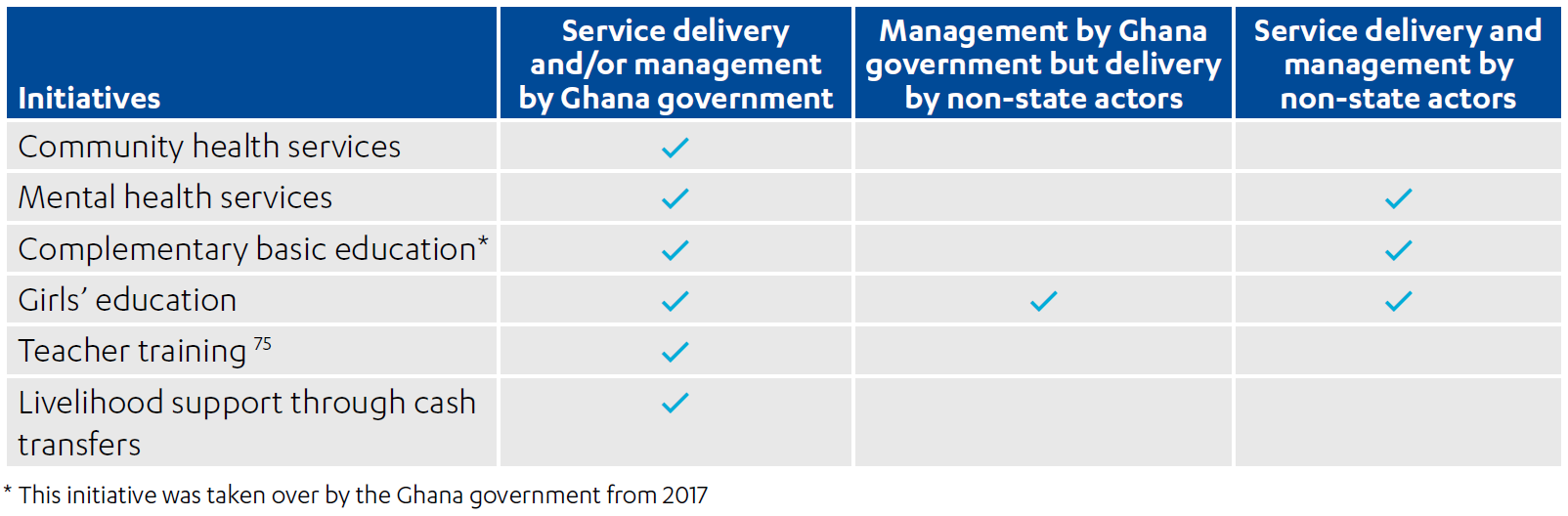

UK aid in Ghana has a mixed record in contributing to strong and sustainable institutions that do not rely on donor support for their continued functioning. Programming in the governance sector – especially on anti-corruption and tax revenue – builds on best practice for achieving sustained outcomes. Meanwhile, health and education service delivery projects run a considerable risk that development gains will be lost as DFID reduces direct financing of services through bilateral channels. In order to reach a larger number of beneficiaries directly with services, DFID developed delivery capacity outside of the state in some of its key social programmes. This delivered effective short-term results but at the cost of developing core state capacity for the sustainable delivery of services to Ghana’s citizens.

| Individual question scores | |

|---|---|

| Question 1 Relevance: How well has the UK aid portfolio responded to Ghana’s development needs and UK strategic objectives? |  |

| Question 2 Effectiveness: How effective has UK aid been in achieving its strategic objectives in Ghana? |  |

| Question 3 Sustainability: How likely are the results of UK aid to be sustained in the future? |  |

Executive summary

After more than two decades of continuous economic growth, Ghana has gone from relative poverty to become one of West Africa’s wealthiest countries, achieving the status of lower-middle-income country in 2011. As Ghana’s economy transforms, the country’s development partnership with the UK is also changing, from a traditional donor-recipient relationship to a development partnership of mutual benefit to both countries.

This country portfolio review assesses how UK aid in Ghana has been reoriented since 2011 to reflect and support this transition. The aim of UK aid is to help Ghana overcome its still considerable economic and governance challenges, reduce its reliance on traditional aid, and drive its own development, while protecting past development gains. A key priority is that Ghana’s economic growth is inclusive – in other words that it improves jobs and livelihoods, health care and education for all Ghanaians, including the poorest and most vulnerable of the country’s citizens and regions. This includes supporting Ghana in strengthening the competence and transparency of its institutions, and helping Ghanaian civil society keep the authorities accountable to its citizens.

Background

During its period of sustained growth, Ghana has made significant strides in improving conditions for its citizens. Ghana was the first African country to meet the Millennium Development Goal (MDG) target of halving extreme poverty by 2015, and the country also made strong improvements on a range of other MDGs. It is a stable democracy, with a vibrant civil society, an independent press, and regular free and fair elections. Since democracy was restored in 1992, elections have led to a peaceful change in government three times.

In 2007, Ghana discovered oil, with commercial production starting in 2011. With new recent discoveries, oil production is now expected, by 2025, to almost double its 2018 level to about 500,000 barrels a day. How well Ghana spends the considerable windfall from its oil and gas revenues to support inclusive, sustainable growth will be critical to the country’s future development progress.

Despite the many improvements, huge challenges remain. Indeed, in recent years economic growth has been modest and progress on poverty reduction has nearly come to a standstill. There are clear risks that some of Ghana’s development gains may be reversed in the face of macroeconomic instability, over-reliance on the export of a few commodities (cacao, gold and, recently, oil), high and growing public debt and increased inequality. Citizens report in Afrobarometer polls and in our own consultations that corruption has got worse.

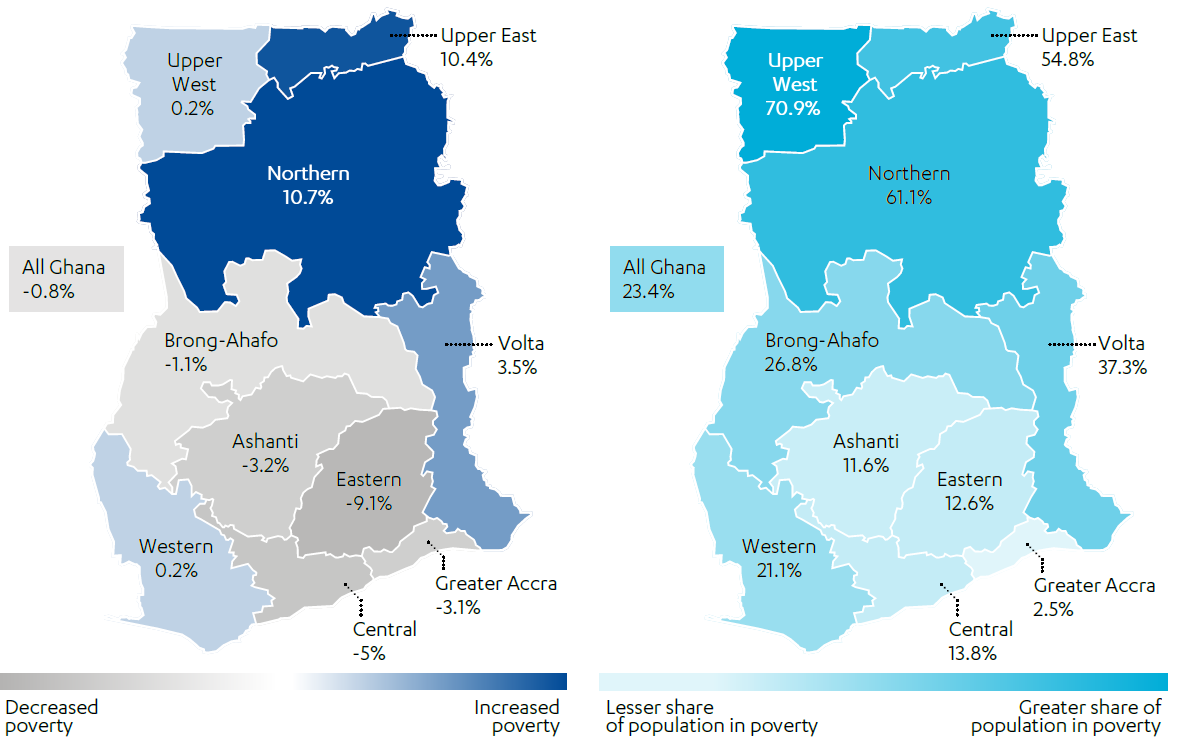

The rural Northern and North East regions of Ghana have been falling behind the rest of the country, with both poverty and extreme poverty on the rise since 2013. There is also considerable and deepening inequality in service delivery, with much worse access to quality education and health care in the Northern region than the rest of the country. Nationwide, access to basic public services is worse for women and girls, and for disabled people.

Ghana’s government has made it clear that it wants its development partnerships to move beyond aid. The UK, which committed £2.8 billion in bilateral aid to Ghana between 1998 and 2017, has responded positively to Ghana’s ambition and the two countries have been working together to build new forms of cooperation. The UK aid approach in Ghana has also been influenced by the UK’s desire to move away from financing service delivery costs as expressed by its political leadership, and more recently the 2018 ‘Fusion Doctrine’, which sees aid as part of a range of economic, political and security levers to build mutually beneficial relationships with emerging markets and middle-income countries.

As part of the transition, and as a result of shifting more resources to poorer and more fragile countries, UK bilateral aid to Ghana has dropped, with bilateral aid programming from the Department for International Development’s Ghana office (DFID Ghana) in social sectors such as education and health seeing the greatest reductions in the country budget. The increase in the UK’s contributions to multilateral development assistance through, for example, the World Bank and UN agencies has only gone some way to make up for this reduction. There has also been increasing focus on the use of a combination of trade, investment and aid to support private sector development, job creation and inclusive growth. As a result of this shift, there is now a broader range of UK government actors involved, including the Foreign and Commonwealth Office (FCO), the National Crime Agency (NCA) and HM Revenue and Customs (HMRC), though the UK’s development partnership with Ghana is still dominated by DFID.

Relevance: How well has the UK aid portfolio responded to Ghana’s development needs and the UK’s strategic objectives?

The strategic priorities guiding the UK’s Ghana aid portfolio in the 2011–2019 period are aligned both with the 2015 UK aid strategy and with the Beyond Aid strategy of the Ghanaian government. During this period, DFID shifted its governance portfolio in Ghana from budget support and expenditure management to three new areas where it believed it could make a bigger difference: 1) anti-corruption, 2) tax policy and administration, and 3) oil and gas revenue management. All three areas are highly relevant to building Ghana’s self-reliance and addressing key barriers to inclusive growth.

In the social sectors, such as health and education, a large proportion of DFID’s programming targeted the needs and priorities of Ghana’s poorest and most vulnerable people as well as regions of the country lagging behind. As such, the strategy is strongly aligned with UK aid’s commitment to gender equality and leaving no one behind. More than 92% of bilateral UK aid expenditure in the social sectors in Ghana was targeted in full or in large part at groups who are (at risk of being) left behind.

We found, however, that as the UK looked to reduce its bilateral aid spending as part of transitioning its partnership with Ghana beyond aid, crucial decisions on reducing aid in the social sectors were made without a sound analysis of how this would affect service delivery for the poorest and most vulnerable. We found no convincing evidence that the decisions on where to stop and where to continue the financing of service delivery were based on analyses of needs, the sustainability of the services delivered, or capacities built. We also found that citizen consultation is not a systematic part of programme design, monitoring or evaluation.

The UK’s ability to deliver a transformative impact in Ghana’s development improved over the review period. DFID is well positioned and respected as a strategic partner for Ghanaian government agencies, and coordination between different UK government actors has improved. At the end of the period, key UK government departments were working together in a broad, cross-departmental approach to support Ghana’s economic development. This was a coherent response to the government of Ghana’s beyond aid priorities. At the same time, the closer cooperation between UK trade, investment and aid instruments helped DFID manage the risk to development objectives and ensure the proper use of official development assistance, although we note that this depended heavily on country leadership giving priority to development objectives as well as capacity in the DFID Ghana office.

While we were not convinced by DFID’s justifications for reducing aid to finance service delivery in the social sectors, or by the lack of systematic approach to citizen consultation, we have awarded a green-amber score for relevance, in recognition that the UK aid portfolio has responded well in most respects to Ghana’s development needs over the review period and is well aligned to broader UK aid objectives and commitments.

Effectiveness: How effective has UK aid been in achieving its strategic objectives in Ghana?

DFID mostly met or exceeded the output targets set in programme documents and in the results framework for the 2011–2015 Operational Plan. However, this results framework covered less than half the spending during that period, while no results framework was stipulated in the business plan for 2016–17 to 2019–20. Clear portfolio outcome measurements on longer-term achieved benefits are thus not in place. In DFID’s plans, strategic objectives were largely stated in terms of what UK aid was going to do, rather than what outcomes it wanted to achieve through those actions. The DFID plans did not include results frameworks to monitor progress on such target outcomes. This meant there was little guidance to country office staff as programmes were developed, monitored and adjusted, or when there was pressure to add new intervention areas.

However, based on our own contribution analysis of the evidence available, we found – positively – that UK aid programmes often contributed to Ghana’s development progress, although with varying levels of effectiveness. Out of the ten UK aid objectives for Ghana (in the areas of anti-corruption, human development and leaving no one behind, and private sector development and inclusive growth), we found strong contributions from UK bilateral aid for four objectives, and an essential contribution in two areas. Without the DFID programme, little would have been done on mental health care and complementary basic education. As a result of the UK aid intervention, more than 100,000 patients accessed mental health services in 2018 and about 200,000 children from hard-to-reach communities entered or re-entered formal schooling. UK aid’s contributions to Ghana’s development results were particularly strong in social sector programming focused on the poorest and most vulnerable.

Our contribution analysis also highlighted how factors outside DFID’s control negatively affected results, particularly the worsening macroeconomic conditions, which stalled and reversed poverty gains and made the government of Ghana less able to finance complementary actions. In some cases, such as the objective to strengthen access to social safety nets for the most vulnerable, the overall development result for Ghana was that more people were extremely poor in Ghana in 2017 than in 2013, but without the safety nets provided by UK support, many struggling households would have been even worse off than they were.

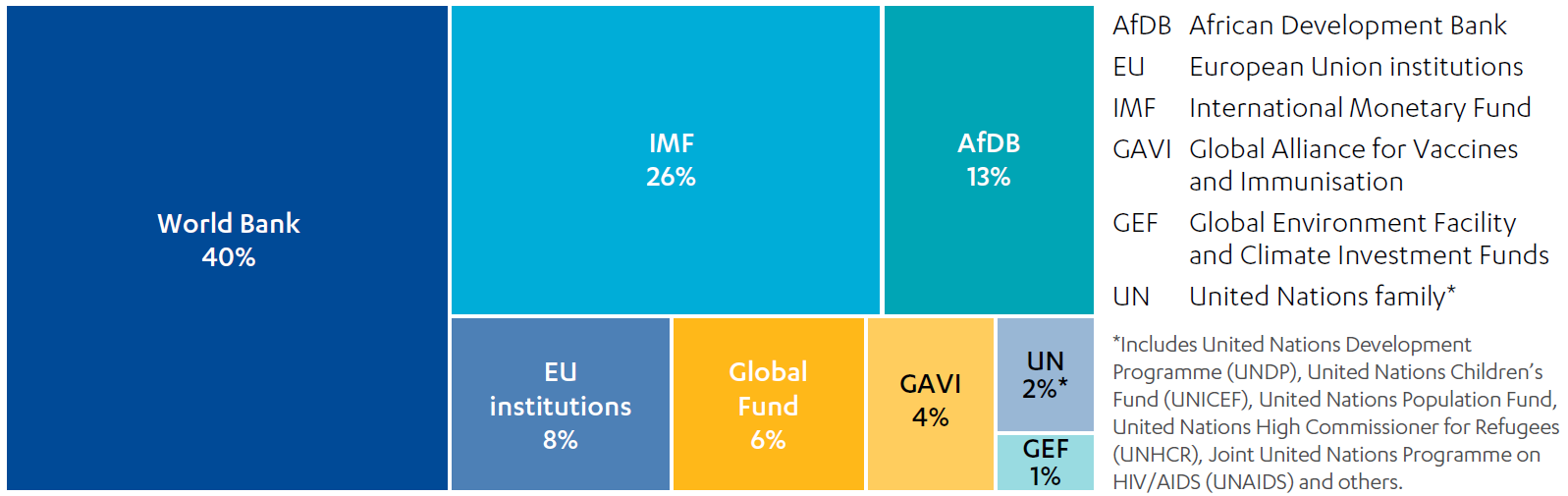

DFID’s relative programme success compared to other donors has been helped by strong partnerships, its technical capacity and the choices it made on delivery. DFID Ghana has a good relationship with the government of Ghana as well as with other donors, and is a respected and appreciated partner. As the UK has reduced its bilateral aid spending in Ghana, it has been able to rely on multilateral partners, such as the World Bank, IMF, African Development Bank and UN agencies, to contribute to progress against UK aid objectives. While we note many advantages of providing aid through multilateral channels in a transition context such as Ghana’s, we found that DFID has not worked strategically with partners to influence multilateral partner programming. Given the increasing proportion of UK aid funding to Ghana going through multilateral channels, this is an area where it needs to improve.

While UK aid has not been able to harness all its resources, including through multilaterals, to maximise the achievement of its objectives, and while there is a dearth of outcome data for UK bilateral aid programming, we found credible evidence that the UK aid portfolio in Ghana is contributing to important results. We have therefore given a green-amber score for effectiveness.

Sustainability: How likely are the results of UK aid to be sustained in the future?

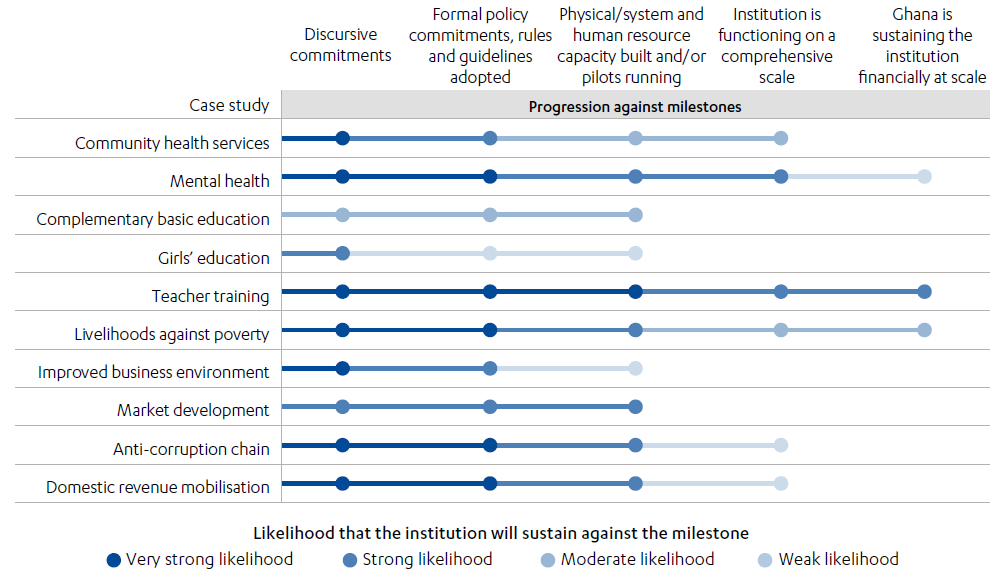

Achieving sustainable results is the greatest challenge for external aid programmes. DFID has a mixed record in contributing to creating strong and sustainable Ghanaian state, civil society and market institutions that do not rely on donor support for their continued functioning. We judged institutional strengthening to be credible for the long term when we found convincing evidence that there is strong domestic policy commitment, the institution is generally functioning well, and financing is sustainable and not donor-driven. Out of ten case studies, we found only one intervention, on teacher training degrees, that contributed to a strong institution with sustained financing at scale beyond UK aid contributions. DFID’s results in the areas of mental health and livelihoods were also promising to become sustainable at this level. In the remaining seven cases DFID had built some elements of institutional capacity, and has made progress towards these elements being sustainable in three of these cases, but we did not find that the institutions were strong enough to continue functioning at improved levels in the long term.

In the social sectors where DFID assisted many of the poorest and most vulnerable Ghanaians over the review period, it is not clear that the key results that DFID delivered will be sustained as the department winds down its direct bilateral financial support, especially considering that the government of Ghana is still emerging from its macro-fiscal crisis and continues to have a highly constrained financial and delivery capacity. We also found that DFID’s approach to output results is not conducive to sustainable outcomes or institution building: in order to reach a larger number of the most vulnerable directly with services, DFID developed delivery capacity outside of the state in some of its key social programmes. This delivered good results but was at the cost of developing core state systems and institutions for the sustainable delivery of services to Ghana’s citizens.

Recent bilateral aid programming in the governance sector – especially on anti-corruption and increasing tax revenue – is built on best practice for achieving sustained outcomes, including on working with political awareness, finding traction with units or individuals with a shared commitment to solving specific problems or better governance, and working adaptively by learning lessons on what works along the way. This approach is more likely to bear fruit than top-down system-wide technocratic reforms, and we already see signs that the institutional strengthening model used in the governance sector shows early promise.

However, this emerging model has not been applied across the portfolio, and we also found many examples of poorly thought-through institutional strengthening interventions that created unsustainable structures, or were overly focused on changing rules, procedures and guidelines and delivering training without also ensuring that practices change.

DFID made important contributions to Ghana’s macroeconomic management capability and stabilisation after the 2014 macroeconomic crisis, through dialogue with the government of Ghana, technical assistance to the Bank of Ghana, and supporting the work by the IMF on macro-fiscal stabilisation and by the IMF and the World Bank on public finance management. As the UK’s bilateral aid spending continues to reduce, this type of support will be crucial to help ensure that Ghana sustains its development gains.

Since we conclude that there is a clear risk that key results delivered by UK aid between 2011 and 2019 will not be sustained, we have given an amber-red score for the sustainability of the UK aid portfolio in Ghana.

Recommendations

We offer the following recommendations:

Recommendation 1

In transition contexts, DFID should ensure that the pace of ending the bilateral financing of service delivery in areas of continuing social need must be grounded in a realistic assessment of whether the gap left will be filled.

Recommendation 2

DFID should require portfolio-level development outcome objectives and results frameworks for its country programmes.

Recommendation 3

DFID Ghana should learn from its own successes and failures when designing and delivering its systems strengthening support and technical assistance.

Recommendation 4

In transition contexts, DFID country offices, in coordination with the multilateral policy leads, should increasingly work to influence the department’s country multilateral partners on issues of strategic importance.

Recommendation 5

In order to strengthen the relevance of its aid programming and accountability to the people expected to benefit, DFID should include information on citizen needs and preferences, especially for the most vulnerable, as a systematic requirement for portfolio and programme design and management.

Recommendation 6

The government should provide clear guidance on how UK aid resources should be used in implementing mutual prosperity objectives to minimise risks and maximise opportunities for development.

Introduction

After more than two decades of continuous economic growth, Ghana achieved the status of lower-middle-income country in 2011. As Ghana’s economy transforms, the country’s long-standing development partnership with the UK is also changing. The UK has invested about £2.8 billion in bilateral aid in Ghana over the past two decades. Since 2011, the UK’s aid portfolio has been reoriented towards helping Ghana overcome its economic and governance challenges and mobilising the resources to finance its own development. At the same time, the UK has continued to finance education, health and social protection programmes in Ghana, but with less funding.

This review assesses the relevance, effectiveness and sustainability of all UK official development assistance (ODA) flows to Ghana relative to the UK’s following objectives:

- Transforming Ghana’s economy: contributing to inclusive growth in Ghana so that the benefits from a growing economy are shared widely among the population.

- Leaving no one behind: tackling extreme poverty and vulnerability in Ghana, including through addressing gender disparities.

- Strengthening Ghanaian institutions: supporting Ghana in developing competent and sustainable institutions.

- Transitioning the UK/Ghana partnership: managing transition away from a traditional aid relationship in a manner that safeguards past development gains.

Our review covers almost all UK ODA to Ghana from 2011 to 2019. It includes almost all bilateral aid from all UK government departments as well as the UK’s imputed share of multilateral aid to Ghana.

Box 1: Defining UK aid to Ghana

The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development’s Development Assistance Committee (OECD DAC) defines ODA as all technical cooperation and concessional official resource flows to aid-recipient countries and multilateral institutions to promote economic development and welfare.

Direct ODA from the UK government to Ghana is bilateral aid. This can be either exclusively for Ghana (in-country programmes), or part of UK government regional or international aid programmes with activities in Ghana (centrally managed programmes).

In some cases, the UK asks multilateral agencies to implement its bilateral programmes in Ghana. This is called multi-bi spending. Multilateral agencies also implement their own programmes in Ghana, which are in most cases partly financed by the UK through its contribution to the agencies’ budgets at the global level. This is the UK’s multilateral aid spending.

The review is built around the evaluation criteria of relevance, effectiveness and sustainability. It addresses the following questions and sub-questions:

Table 1: Our review questions

| Review criteria | Review questions |

|---|---|

| Relevance: How well has the UK aid portfolio responded to Ghana’s development needs and UK strategic objectives? | How well do the objectives of UK aid align with Ghana’s development needs and priorities? • How well positioned is UK aid to deliver transformative impact and help Ghana mobilise sources of development finance? • How coherent is UK aid spending in Ghana across departments, aid instruments and delivery channels with reference to UK strategic objectives? |

| Effectiveness: How effective has UK aid been in achieving its strategic objectives in Ghana? | • How well has the UK bilateral aid programme delivered its intended outcomes? • How well has UK multilateral aid supported UK aid objectives in Ghana? • How well has the UK maintained and developed partnerships with government, civil society and other development actors? |

| Sustainability: How likely are the results of UK aid to be sustained in the future? | • How successfully is the UK supporting the development of sustainable Ghanaian institutions? • How well is the UK helping to protect past development gains against setbacks and reversals? |

Box 2: How this report relates to the Sustainable Development Goals

The Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), otherwise known as the Global Goals, are a universal call to action to end poverty, protect the planet and ensure that all people enjoy peace and prosperity.

Related to this review: Since this is a review of an entire country portfolio, rather than a particular development challenge, a broad range of SDGs are relevant to UK aid delivery in Ghana. Most important for the UK’s priorities in support of Ghana’s development are the following SDGs:

![]() Goal 1: End poverty in all its forms everywhere – the UK aid portfolio included programmes aimed at alleviating poverty and ensuring that poor people can access services and markets.

Goal 1: End poverty in all its forms everywhere – the UK aid portfolio included programmes aimed at alleviating poverty and ensuring that poor people can access services and markets.

![]() Goal 3: Ensure healthy lives and promote well-being for all at all ages – in Ghana, UK aid support in the health sector included programmes targeting malaria, primary, reproductive and mental health care.

Goal 3: Ensure healthy lives and promote well-being for all at all ages – in Ghana, UK aid support in the health sector included programmes targeting malaria, primary, reproductive and mental health care.

![]() Goal 4: Ensure inclusive and equitable quality education and promote lifelong learning opportunities for all – in Ghana, UK aid support in the education sector included programmes aimed at eliminating gender disparities in secondary education, improving access for out-of-school children, and improving the quality of schooling through pre-service teacher training.

Goal 4: Ensure inclusive and equitable quality education and promote lifelong learning opportunities for all – in Ghana, UK aid support in the education sector included programmes aimed at eliminating gender disparities in secondary education, improving access for out-of-school children, and improving the quality of schooling through pre-service teacher training.

![]() Goal 5: Achieving gender equality and empower all women and girls – several UK aid programmes in Ghana mainstreamed gender equality by targeting women and girls.

Goal 5: Achieving gender equality and empower all women and girls – several UK aid programmes in Ghana mainstreamed gender equality by targeting women and girls.

![]() Goal 8: Promote sustained, inclusive and sustainable economic growth, full and productive employment and decent work for all – in Ghana, UK aid programmes provided business environment and industrial policy support.

Goal 8: Promote sustained, inclusive and sustainable economic growth, full and productive employment and decent work for all – in Ghana, UK aid programmes provided business environment and industrial policy support.

![]()

Goal 9: Build resilient infrastructure, promote inclusive and sustainable industrialisation and foster innovation – in Ghana, UK aid supported the integration of small-scale farmers and small enterprises in the Northern region into value chains and markets.

![]()

Goal 10: Reduce inequality within and among countries – in Ghana, where there is large and growing inequality between the country’s regions, UK aid has channelled significant aid to the regions in the north of Ghana, which have higher and deeper poverty than in the central and southern regions.

![]() Goal 17: Strengthen the means of implementation and revitalise the global partnership for sustainable development – in Ghana, UK aid has supported significant institutional strengthening and capacity building programmes. Recently, UK aid has supported a cross-UK government effort to support Ghana’s development through improved trade.

Goal 17: Strengthen the means of implementation and revitalise the global partnership for sustainable development – in Ghana, UK aid has supported significant institutional strengthening and capacity building programmes. Recently, UK aid has supported a cross-UK government effort to support Ghana’s development through improved trade.

Methodology

Our review assessed the contribution of UK aid-financed interventions to the UK government’s aid objectives in Ghana. We organised our work into three themes in alignment with the main UK aid objectives: 1) governance and anti-corruption, 2) human development, and 3) inclusive growth and private sector development. We assessed secondary evidence on the performance of UK aid flows in Ghana and supplemented this with primary evidence for validation and gap-filling. This was done through the following methodological elements:

Strategy review: We analysed strategies and policies at the global, regional, country and thematic/sector level from relevant UK government departments, predominantly the Department for International Development (DFID).

Literature review: We reviewed selected literature on key issues in the Ghana and UK aid context. This included literature on Ghana’s political economy and socio-economic development, common challenges in oil and gas revenue governance and management in sub-Saharan Africa, and aid partnerships in transition contexts. The literature review is available on the ICAI website.

Programming review of UK aid: We mapped bilateral and multilateral UK aid flows and results, did a rapid desk review of all bilateral and key multilateral programmes in the UK aid sectors, and undertook ten in-depth case studies of programme areas supported by UK aid, focusing on the bilateral channels but also taking into account the multilateral channel (see Table 2 below for a list of the ten case studies).

Stakeholder consultation: We consulted Ghana government informants across a range of central government and regional government offices, Ghana civil society organisations, media representatives, academics, professional associations and bodies, businesses and business representatives. We also consulted UK government officials in London and Ghana, members of a civil society organisation representing the African diaspora focusing on Africa’s development, and UK development nongovernmental organisations (NGOs) with activities in Ghana.

Citizen consultation: We consulted citizens of Ghana who should have either directly or generally benefited from UK aid. Consultations reached over 800 citizens through a variety of forums (see Figure 1) in eight districts of two regions where UK aid delivered programmes. These forums included town hall meetings, focus group discussions and informal conversations with individual citizens using public services that UK aid supported, interviews with small business owners and market traders, and with young women who had been supported by UK aid to continue their schooling.

Figure 1: Citizen consultation methods

Full details of the methodology and sampling approach are provided in the Approach Paper for the review.

Table 2: List of case studies

| Case study (programme focus area) | Examples of UK aid bilateral interventions and multilateral involvement |

|---|---|

| Governance and anti-corruption | |

| Addressing corruption | Strengthening Transparency, Accountability and Responsiveness in Ghana (STAR I and II) (Phase I_ 2010–16, Phase II_ 2015–2021), Strengthening Actions Against Corruption in Ghana (STAAC) (2017–2021), International Action on Corruption (I-ACT) (2017–2021)UK departments and funds_ DFID, National Crime AgencyMultilateral_ EU |

| Improved domestic revenue performance through strengthened domestic revenue mobilisation institutions | Interventions: Revenue Reform Programme (2015–19), Ghana Oil and Gas for Inclusive Growth (2014–19), Supporting Tax Transparency in Developing Countries (2013–18) (centrally managed programme) UK departments and funds: DFID, HM Revenue and Customs Multilaterals: World Bank, IMF |

| Human development and leaving no one behind | |

| Improved access to mental health care | Interventions: Health Sector Support Programme (HSSP) (2013–19), Leave No One Behind Programme (LNOB) (pipeline) and STAR, Time for Change, Maternal Mental Health (2015–2021) UK departments and funds: DFID, Department of Health and Social Care, Foreign and Commonwealth Office (FCO) |

| Improved access to primary health care through better community health services | Interventions: HSSP (2013–19), Sustainable Energy for Women and Children (CMP) (2015–19), DELIVER (closed in 2016), Partnership Beyond Aid Programme (pipeline) UK department and fund: DFID Multilaterals: World Bank, Global Fund, Gavi |

| Increasing girls’ access to schooling | Interventions: Girls – Participatory Approaches to Student Success (GPASS) in Ghana (2011–2021), Girls’ Education Challenge Fund (2016–2025, centrally managed programme) UK department and fund: DFID Multilaterals: World Bank/Global Partnership for Education, UNICEF |

| Transforming teacher education and learning | Interventions: The Transforming Teacher Education and Learning (T-TEL) component of the Girls – Participatory Approaches to Student Success programme (2015–18) UK department and fund: DFID |

| Reducing the share of children who are out of school | Interventions: Complementary Basic Education (2012–18), Education Beyond Aid (EBA) (2018–2022) UK department and fund: DFID Multilaterals: USAID, UNICEF |

| Strengthened access to social safety nets for the most vulnerable | Interventions: Livelihood Empowerment Against Poverty (LEAP) (2012–17), Leave No One Behind Programme (LNOB) (pipeline) UK department and fund: DFID Multilaterals: World Bank, UN family |

| Private sector development and inclusive growth | |

| Improving the business environment | Interventions: UK-Ghana Partnership for Jobs and Economic Transformation (JET) (2018–2024), Business Enabling Environment Programme – Private Sector-Led Growth (BEEP) (2015–2020), Africa Division funding to the African Agriculture Development Company (AgDevCo) (2013–2023), core support to the Private Infrastructure Development Group (PIDG). The Economic Development Investment and Trade (EDIT) initiative is also relevant here, although it is broader than UK aid UK departments and funds: DFID, FCO, CDC Multilaterals: World Bank, PIDG |

| Improving market access for the poor in the Northern region | Interventions: Market Development in Northern Ghana (MADE) (2013–2020), Africa Division funding to the African Agriculture Development Company (AgDevCo) UK departments and funds: DFID, CDC Multilaterals: World Bank, EU |

Box 3: Limitations to the methodology

Our programme assessments were based primarily on monitoring and evaluating information generated by the programmes themselves. We sought to reduce the consequent risk of bias by validating the information through our stakeholder interviews and review of independent documentation for the sampled case studies but did not try to do so for all programmes. This limits our capacity to reach independent conclusions about programme effectiveness if the programme data is inaccurate.

UK aid programmes represent one set of many interventions within complex and changing Ghana and UK contexts. As a qualitative assessment, the review has used contribution analysis to tease out how UK aid has affected its target development outcomes across programmes. The rigour of this analysis is affected by limitations on the evidence collected, including in respect of completeness and reliability.

Our sample of case studies and districts for sub-national fieldwork was necessarily limited and designed to cover a substantial range of programme areas, approaches and contexts. While the findings from the case studies rely on multiple sources of evidence and patterns across case studies, they are subject to selection bias, which is a limit on the broader applicability of findings.

Background

Country context

Ghana is a stable democracy. Since the return to democracy in 1992, its citizens have voted out the incumbent government three times in contested but peaceful and free elections. Ghana has a vibrant civil society and scores above average on international governance assessments of middle-income countries. Ghana is currently ranked sixth out of 54 African states on the Ibrahim Index of African Governance. In 2017, Ghana ranked second of all African countries on the Reporters without Borders media freedom index.

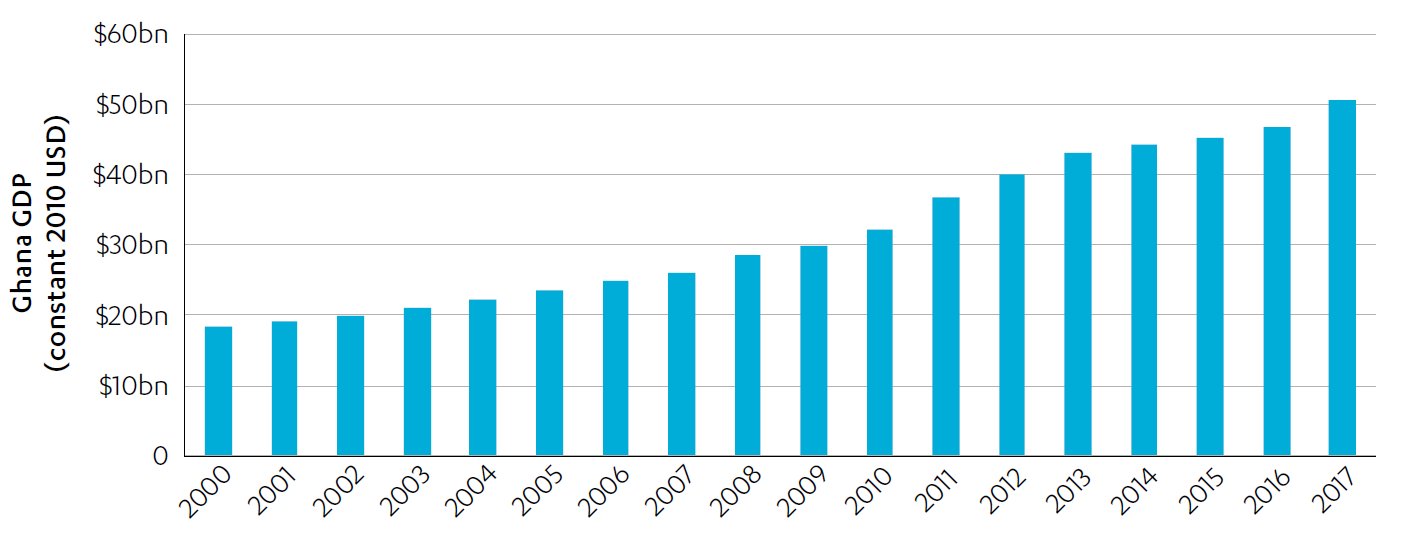

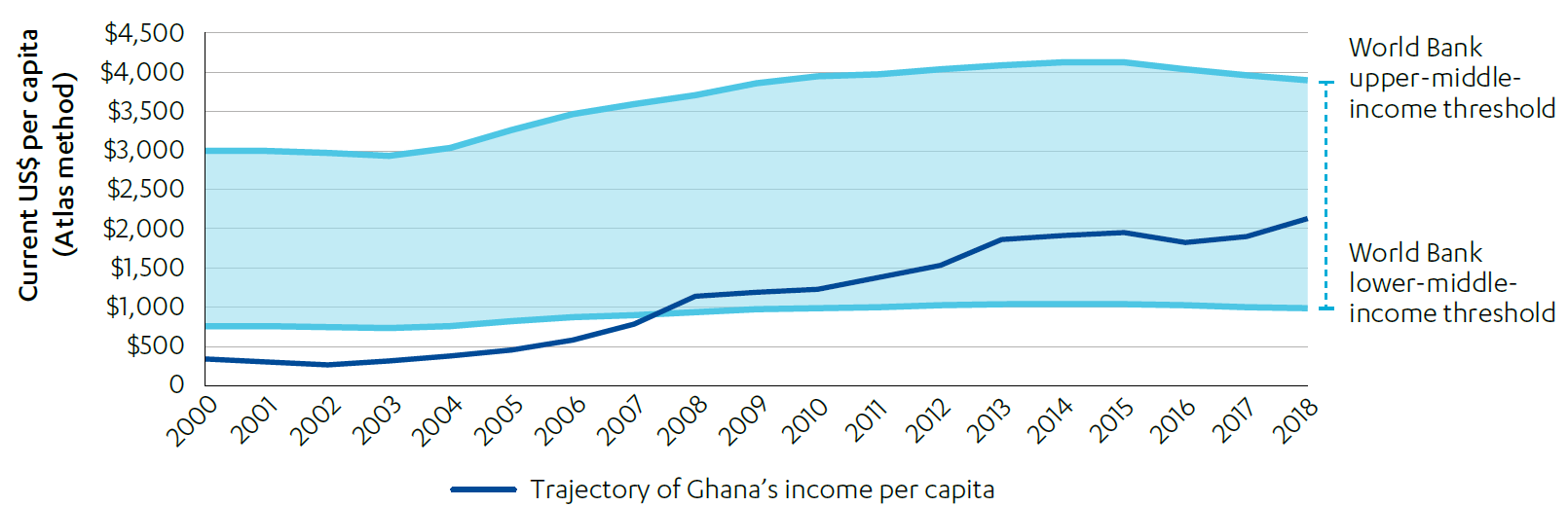

Ghana is a country in economic and social transition. After more than two decades of continuous economic growth (Figure 2), Ghana has gone from relative poverty to become one of West Africa’s wealthiest countries. It was the first sub-Saharan African country to meet the Millennium Development Goal to halve extreme poverty. By 2015, it also halved the number of hungry people and the proportion of people without access to safe drinking water. It achieved universal primary education and gender parity in primary education, reduced HIV prevalence, and increased access to information and communications technology.

Figure 2: Ghana Gross Domestic Product (GDP) 2000 to 2017

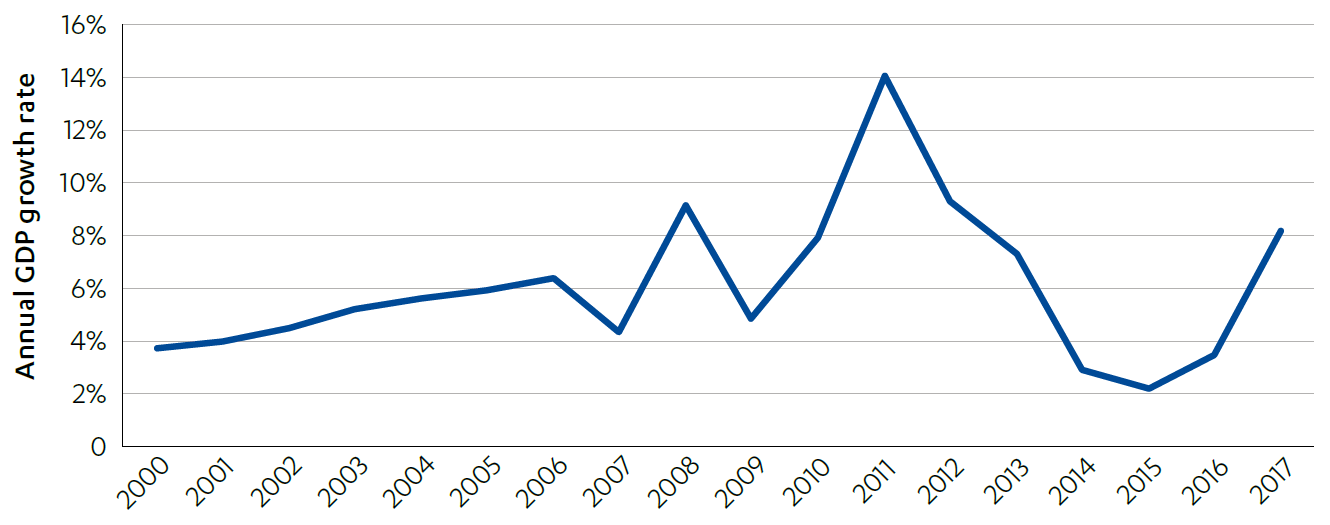

While the GDP growth rate has fluctuated after 2006, Ghana has experienced continuous growth since 2000 (Figure 3). Between 2000 and 2010, the economy almost doubled in size in real terms. In 2010, a technical adjustment to Ghana’s economic statistics resulted in an overnight promotion to one of the top ten economies in Africa by size. The World Bank officially classified it as a lower-middle-income country on 1 July 2011. On the adjusted data, Ghana arguably already achieved this status a few years earlier (Figure 4).

Figure 3: Ghana Gross Domestic Product (GDP) annual growth rate 2000 to 2017

Ghana’s oil discovery in 2007 is credited with fuelling the country’s growth spurt in 2011–12. At peak production, oil from known reserves currently exploited could contribute just over 9% of GDP and about 30% of the government’s revenue. The government of Ghana recently announced the discovery of a further one billion barrels of reserves, expecting production to almost double by 2025. The windfall from the oil and gas sector could therefore make a substantial contribution to Ghana’s socio-economic transformation, if managed well.

Figure 4: Change in Ghana’s gross national income per capita 2000 to 2018

Ghana’s economy, however, has not diversified. Exports are centred on commodities (cacao, gold and, recently, oil). Structural change has occurred, in so far as services replaced agriculture as the largest sector employing the most people. But the structural changes as yet do not equal a transformational shift. This makes the economy vulnerable to domestic and external price and exchange rate shocks.

Macroeconomic instability continues to pose a high risk to Ghana’s continued growth and development. From 2012 Ghana’s macroeconomic conditions started deteriorating, brought about by a large public sector wage bill, costly energy subsidies, severe power shortages and worsening terms of trade. Frequent overspending (more pronounced in election years), low tax effort and public financial management weaknesses have undermined the public finances, ratcheted up public debt and largely consumed the fiscal buffer that had resulted from the 2006 Multilateral Debt Relief Initiative.

By 2014, large fiscal and current account deficits, high and expensive public debt, high inflation and a sharp depreciation of the currency were throttling the economy, and growth slowed rapidly. In April 2015, a three-year IMF Extended Credit Facility of about $916 million was approved, assisting economic recovery, but economic growth between 2014 and 2017 was considerably slower than before 2013.

As a result, poverty reduction ground almost to a halt. About 400,000 more people were poor in 2016–17 than in 2013–14, and 200,000 more were extremely poor. In total, 6.8 million people are poor in Ghana. Among them about 2.4 million people, the extreme poor, are unable to afford the daily energy requirement to sustain themselves. Most of the poor and extremely poor live in the rural north and north-east of Ghana. Here poverty and extreme poverty worsened significantly between 2013–14 and 2016–17, as shown in Figure 5 below. The depth of poverty – how far people live below the poverty line on average – also increased in these regions.

Figure 5: Regional change in and distribution of poverty in Ghana

In the northern regions of Ghana poverty worsened between 2012–13 and 2016–17. These regions had the highest proportion of the population living in poverty in 2016–17.

Access to quality services is highly unequal between regions. In the Northern region, one fifth of children aged 13 to 15 have never had formal education – four times the national average. Fewer than half of the women and children in the region accessed adequate basic maternal and child health services in 2016, and the region has only four community health care centres for every 1,000 square kilometres, compared to a national average of 23.

Gender disparities persist. While girls’ enrolment in primary and junior high school education was on a par with or better than boys’ enrolment by 2011, this was due to shifts in the wealthier south and not true for the poorest girls or girls in northern Ghana. Despite gender parity in senior high school enrolment, significantly fewer female students than male students qualified for tertiary or higher education in all regions, and especially in the north. Women have lower labour market participation and higher unemployment levels than men.

People with disabilities are also disproportionately excluded. Far fewer children with disabilities are registered in the education system than the reported prevalence rate, and their attendance rate is significantly lower. In 2015, about one in ten people who were not in the labour force said it was because they were disabled, a much higher proportion than people with disabilities in the population overall.

Ghana’s public sector institutions are weak and ineffective, despite large donor-funded reform programmes during the past three decades. Major weaknesses in the delivery of public services include limited government capacity to formulate and implement policies, poor support from central agencies and weak coordination between sector institutions. A key factor explaining the weakness of Ghana’s institutions is the highly competitive partisan political environment. Each time political power changes hands, a large turnover in the bureaucracy follows. This partisan approach to the hiring and firing of high-level civil servants is made worse by a lack of meritocratic principles in the public service sector and widespread corruption. Furthermore, elections are fought on short-term but expensive promises of infrastructure projects, utility price reductions and abolishing fees. In this environment, policy discontinuity is the norm, undermining reform initiatives with a time horizon longer than the election cycle.

Corruption in Ghana worsened between 2008 and 2017, as measured by the Worldwide Governance Indicators. Citizens also perceive corruption to be worsening, and more reported having to pay bribes now than they did a few years ago. Most fear retaliation if they report corruption.

Ghana’s changing relationship with aid

Since taking office in 2017, Ghana’s president, Nana Akufo-Addo, has been vocal about moving the country ‘beyond aid’. The government released its Ghana Beyond Aid Charter and Strategy in April 2019. The Charter is not ‘anti-aid’. In the words of the Chair of the Ghana Beyond Aid Committee, the aim is to “set our development priorities right so that our creative energies and resources, including aid, can all be deployed to fast track our economic transition from an under-developed country to a confident and self-reliant nation”. As yet, the strategy is aspirational, with limited policy and programmatic detail.

“We can, and should, build … a Ghana where everyone has access to education, training, and productive employment; a Ghana where no one goes hungry and everyone has access to the necessities of life including good health care, water, sanitation, and decent housing in line with the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Indeed, we can, and should, build a Ghana that is prosperous enough to stand on its own two feet; a Ghana that is beyond dependence on the charity of others to cater for the needs of its people, but instead engages with other countries competitively through trade and investments and through political cooperation for enhanced regional and global peace and security.”

President Nana Akufo-Addo

Foreword to the Ghana Beyond Aid Charter and Strategy Document, Government of Ghana, April 2019. p.5

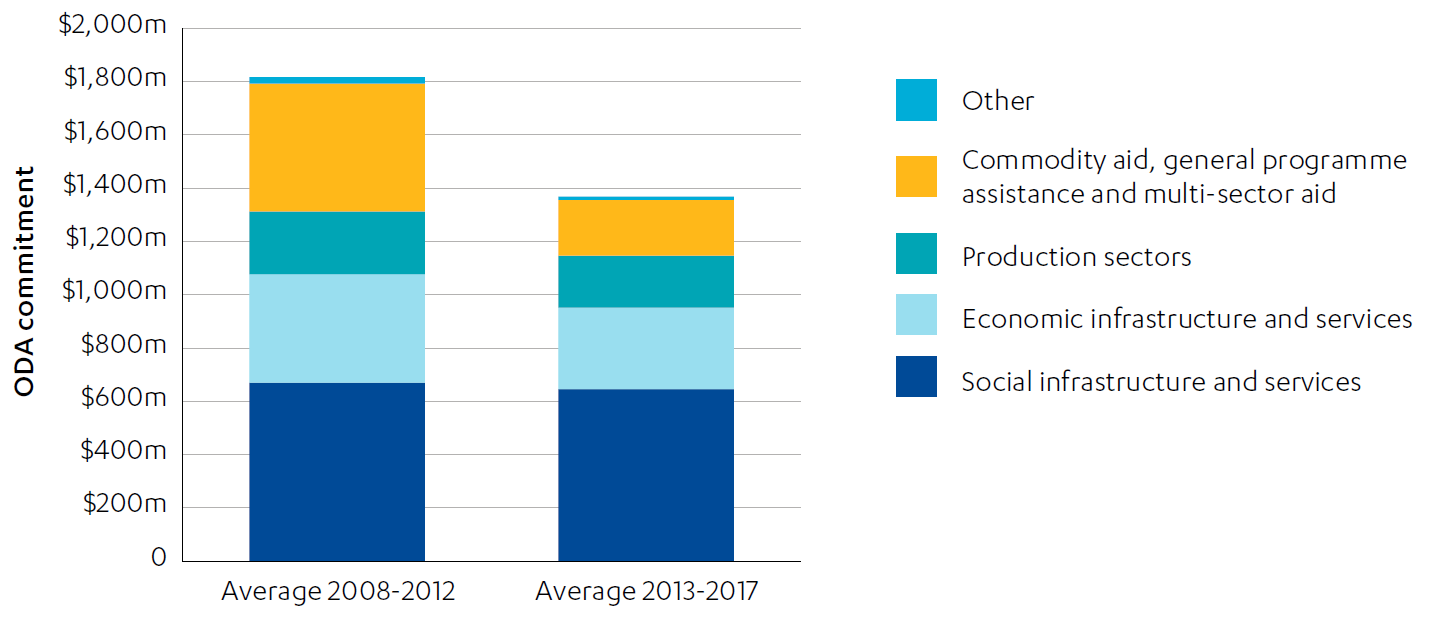

Many donors, including DFID, reduced their ODA portfolios after Ghana graduated to lower-middle-income status in 2011. In the five years between 2013 and 2017, official development partners committed a quarter less ODA than the previous five-year average (see Figure 6), making development assistance less prominent in Ghana’s economy.

Figure 6: Annual average Overseas Development Assistance (ODA) commitments to Ghana

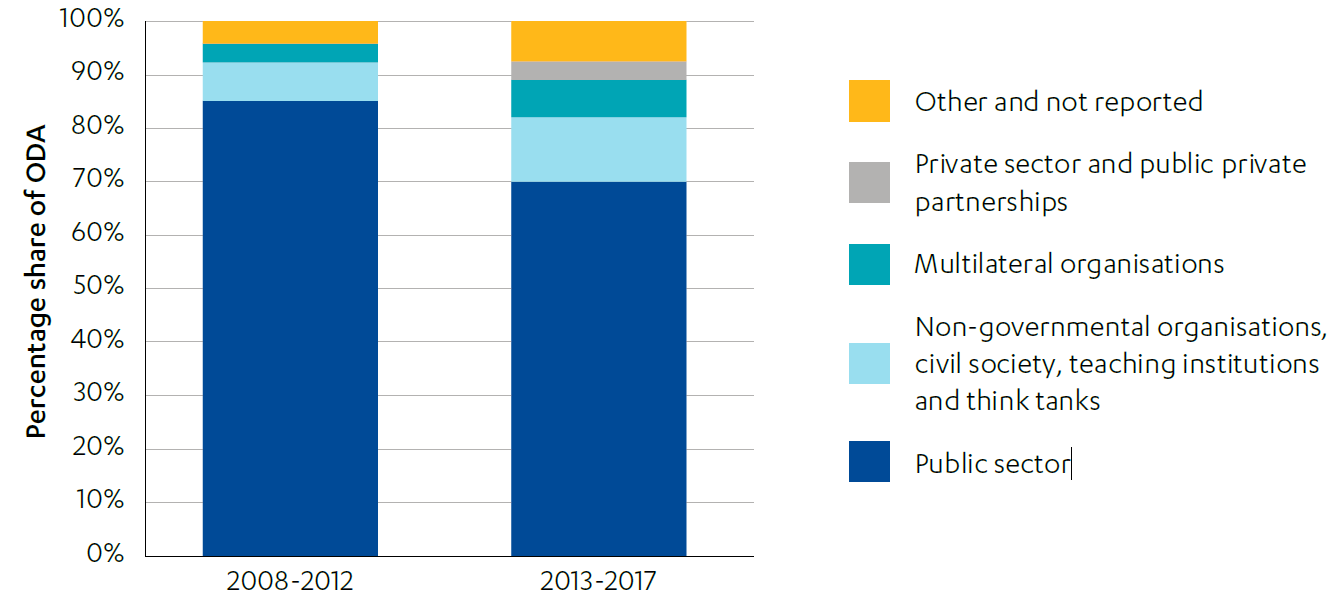

The profile of aid has changed. Support is now more project-based, while multi-sector and programmatic aid – particularly budget support – has shrunk significantly. More aid flows through non-government channels, such as multilateral organisations, private sector organisations and NGOs, civil society, educational institutions and think tanks (see Figure 7).

Figure 7: Share of Overseas Development Assistance (ODA) by channel to Ghana

The way aid cooperation is managed has changed. The formal multi-donor partnership structures that characterised aid delivery at the height of commitment to the Paris Declaration on Aid Effectiveness have largely disappeared in Ghana, as in other countries. The shift was triggered by the disbanding of the multi-donor budget support platform in 2014. Sector working groups still exist, but many fell into disuse or became donor coordination groups.

UK aid in Ghana

The UK committed £2.8 billion in bilateral aid to Ghana between 1998 and 2017, almost 70% of it spent in the first decade. Of the £2.8 billion, 43% was for debt relief or general budget support. Of the remainder, about three quarters went to the social sectors – mainly education in the first decade, then shifting to health in the second decade. By 2011, UK aid had moved out of the transport and water and sanitation sectors and significantly cut support for agriculture, while increasing spending on civil society and private sector development.

UK aid objectives and strategies in Ghana since 2011

In 2011, at the start of the review period, DFID saw Ghana’s growing inequality, gender disparities, poor social and health outcomes, governance challenges and structural economic constraints as the central barriers to the country’s transition.

“The next few years will be crucial for Ghana, offering an opportunity to transform the country’s development, firmly establishing its middle-income status and delivering significantly better health, education and wealth creation outcomes. To achieve this Ghana will need to tackle a set of challenges: over six million people live below the national poverty line; progress against a number of the Millennium Development Goals is disappointing; there are major regional inequalities, with the North of the country suffering significantly higher levels of poverty than elsewhere; women and girls perform worse across all the main social indicators; educational attainment is poor; oil is potentially a blessing, but it could also prove to be a curse; businesses are often too small, unproductive and lacking in innovation; domestic revenue collection is low; macroeconomic stability remains at risk; and Ghana needs to continue to build on its strong electoral track record, especially now that oil has raised the stakes.”

Operational Plan 2011–2015, DFID Ghana, 2012, updated annually.

Two plans frame the DFID response to these challenges in our review period: the 2011–2015 DFID Operational Plan and the DFID Business Plan 2016–17 to 2019–20. DFID’s objectives for Ghana over the period can be summarised as follows:

- Strengthen democratic governance and the ability of Ghanaians to make demands of their government and hold it to account, strengthen domestic revenue mobilisation and the management of natural resource revenues, and help Ghana tackle corruption.

- Promoting prosperity: improve the national investment climate and business environment, diversify the economy and develop domestic markets, and support entrepreneurship in the Northern region.

- Improving human development outcomes and helping the most vulnerable so that no one is left behind: improve selected human development outcomes for Ghanaians in education and health, and improve and expand the safety net for the very poorest, most vulnerable and marginalised groups.

In 2016, a cross-cutting objective was added to strengthen the resilience of poor communities to better withstand the impact of climate change, economic shocks and pandemic disease.

UK aid’s interventions in Ghana were shaped by global UK aid objectives and policy. The 2011 Bilateral Aid Review, followed by the 2016 Bilateral Development Review and an internal DFID poverty allocation model resulted in Ghana becoming less of a priority for support, as DFID moved its focus to poorer and fragile states. Over the period, successive DFID secretaries of state expressed the desire to move away from aid financing the service delivery costs where countries can “step up and take responsibility for investing in their own people”. The 2015 UK aid strategy made UK national interest a co-determinant of UK aid spending and committed the government to increase the share of the UK aid budget spent by departments other than DFID. These departments have tended to focus on countries that are richer than Ghana. In 2018 the Fusion Doctrine, part of the National Security Capability Review, held that all policy levers, including aid, should be available to secure the UK government’s economic, security and influence goals, while the cross-government Africa Strategy emphasised mutually beneficial partnerships driving a strong focus on inclusive growth, trade and investment in Ghana. The UK’s strategic approach to Africa and the Fusion Doctrine are continuations of the policy directions for UK aid already put forward in the 2016 Bilateral Development Review.

With this shift, UK government departments other than DFID began to spend ODA in Ghana. Since 2015, the Foreign and Commonwealth Office (FCO), HM Revenue and Customs (HMRC), the National Crime Agency (NCA) and the Department of Health and Social Care (DHSC) have all launched ODA programmes in the country. A formal cross-government strategy for UK aid in Ghana did not, however, exist until 2018, when the UK-Ghana Prosperity Strategy was developed. This set objectives for an integrated UK offer on economic partnership across diplomatic, trade, investment and development engagement and financing instruments, including UK aid. It did not cover all UK aid flows to Ghana.

DFID has told us that its approach to the partnership with Ghana was shaped by the transition context and these global UK aid funding and policy shifts. As the bilateral country office spend for Ghana reduced, the intent was that the bilateral focus should shift away from directly financing the cost of service delivery to systems strengthening – especially strengthening Ghana’s ability to generate and mobilise its own resources. In this context, the emphasis increased on centrally managed programmes and the multilateral share, as Ghana moved to self-financing its development. At the same time, the desire was to maintain support for the most vulnerable, in keeping with the leave no one behind objective of the country plans.

Changing profile of UK aid to Ghana 2011–2019

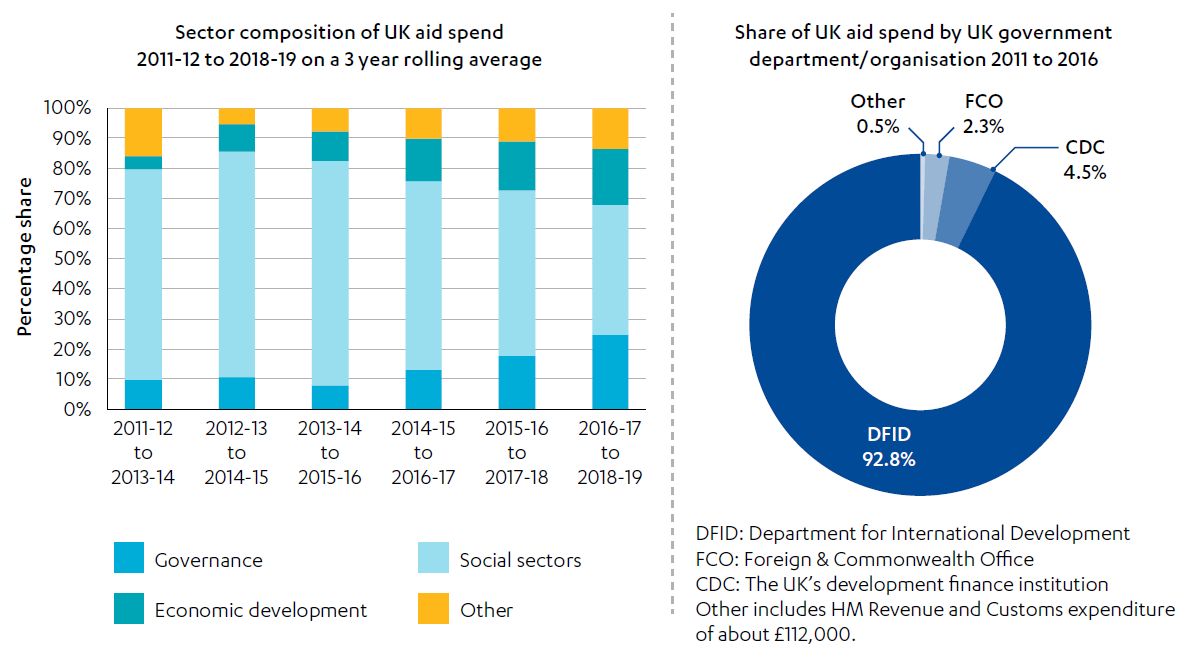

UK bilateral aid to Ghana reduced between 2011 and 2019. Over the five years to 2017, bilateral UK aid was on average half of what had been provided over the previous five-year period. There have also been changes in the composition of aid. Bilateral aid through DFID Ghana shifted from budget support to bilateral projects, with increasing investment in livelihoods and economic development and slowing investment in health and education (see Figure 8 below).

Figure 8: Composition of UK aid spend in Ghana

The UK’s main aid contribution to Ghana towards the end of the period was through multilateral channels, estimated at 66% of the total in 2017 compared to 45% in 2011. There was a 47% growth in UK multilateral aid spending between 2011 and 2017 (resulting in overall growth despite a reduction in bilateral aid), mainly due to the large IMF credit facility extended to Ghana in 2015. If the IMF credit facility is not taken into account, UK multilateral aid in Ghana would have been less than half of its total aid spending between 2011 and 2017.

Figure 9: Multilateral share of UK imputed spend 2011–2017

UK aid programmes in Ghana

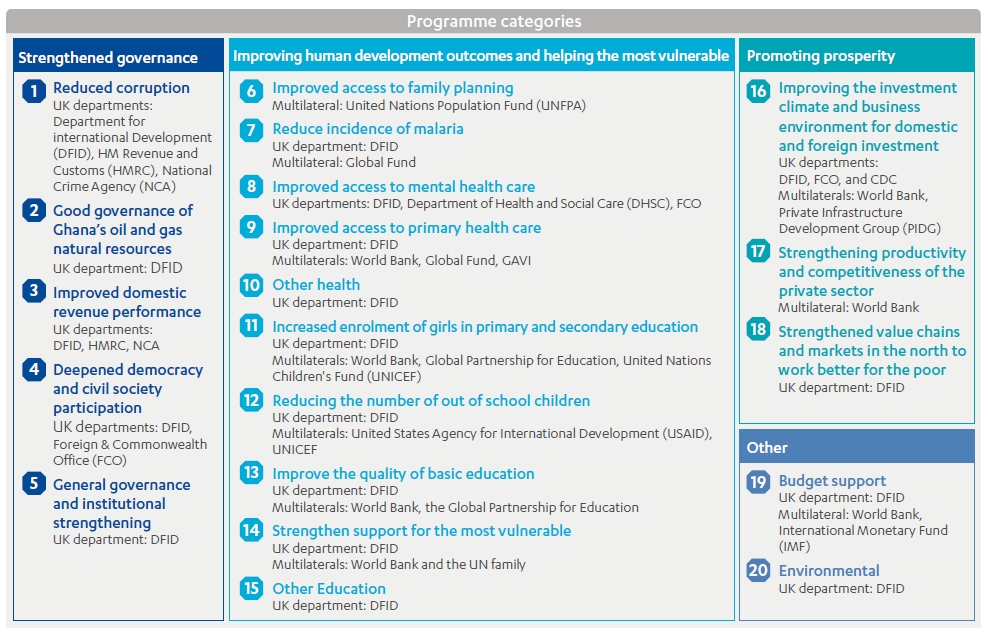

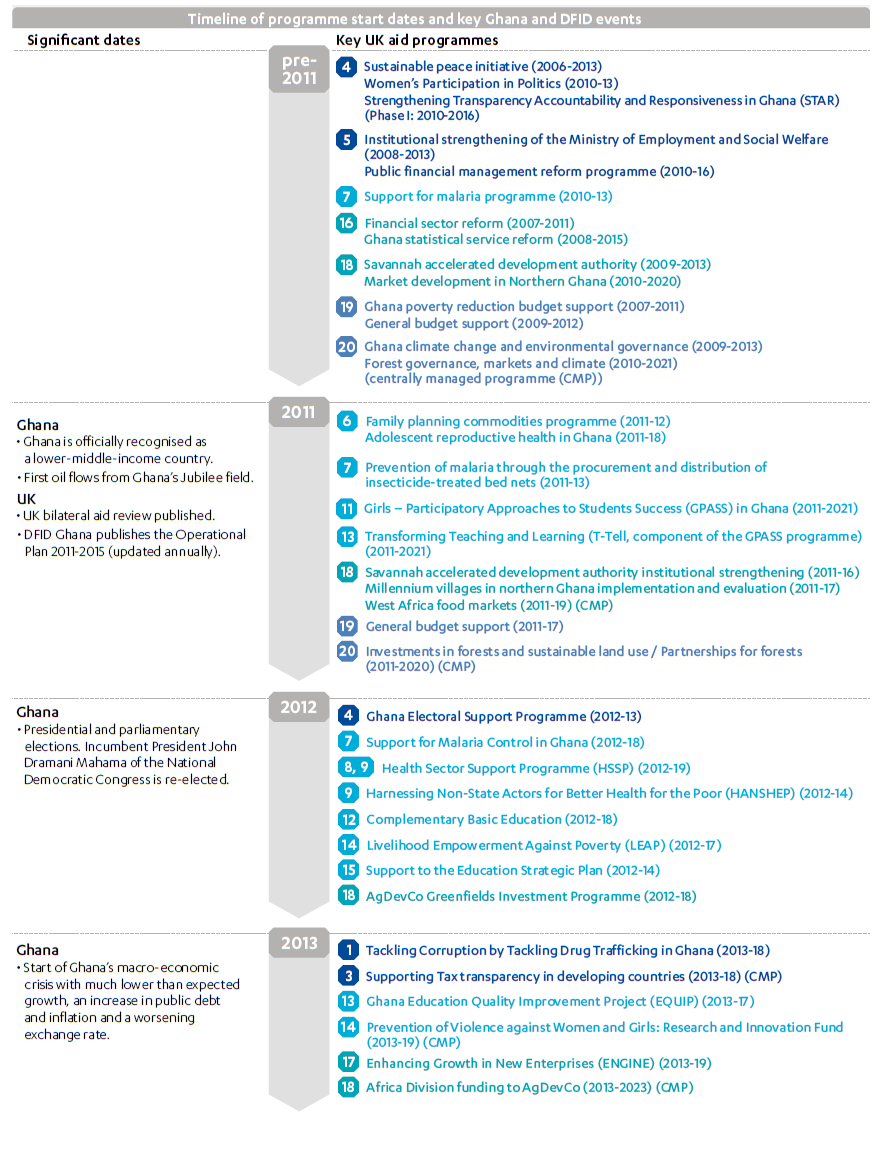

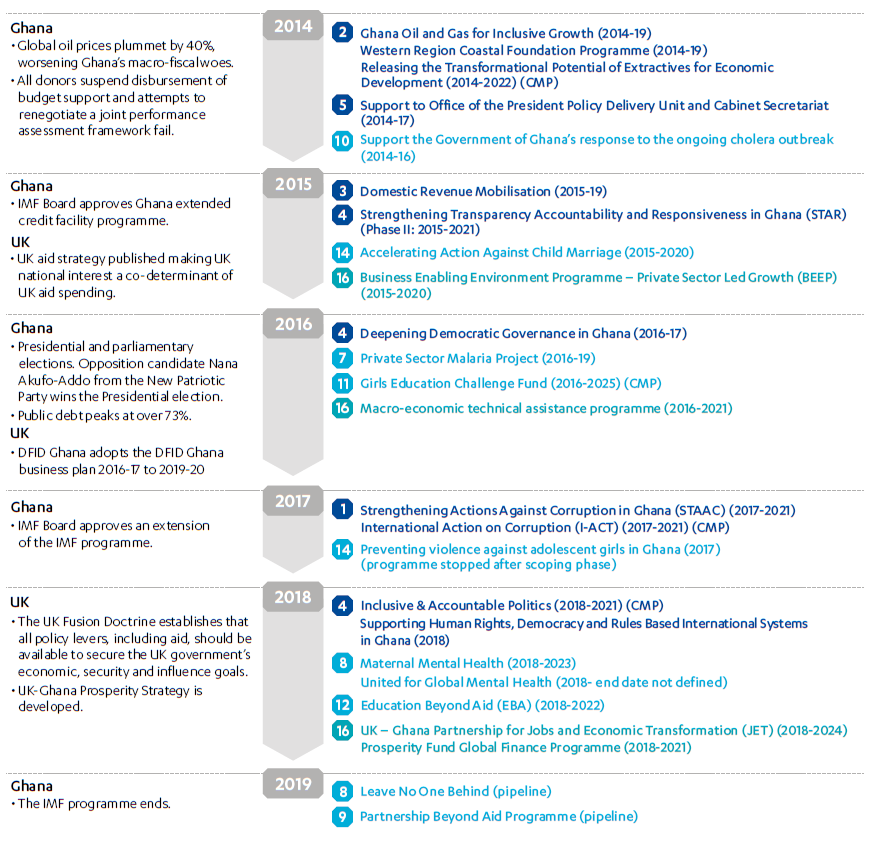

Between 2011 and 2019, UK aid funded more than 60 individual programmes and projects in Ghana. Some were initiated before the 2011 plan. Others had only just begun or were still in the pipeline during our review period. Figure 10 below sets out the key bilateral programmes of UK aid that were active in the period (by objective and programming area). A timeline juxtaposing programme start dates with key Ghana and DFID events follows.

Figure 10: UK aid to Ghana: programming areas, objectives and timeline

Findings

This section presents the findings of our review, covering the relevance, effectiveness and sustainability of UK aid to Ghana. Under relevance we explore how the UK aid portfolio relates to Ghana’s development challenges and the priorities of the UK government. In the effectiveness section we assess how well programmes in the UK aid portfolio have contributed to the achievement of UK aid objectives in Ghana, and the effectiveness of UK aid partnerships. Finally, under sustainability, we look at whether UK aid has been successful in strengthening sustainable Ghanaian institutions and protecting past development gains against setbacks and reversals.

Relevance: How well has the UK aid portfolio responded to Ghana’s development needs and the UK’s strategic objectives?

Addressing Ghana’s governance challenges

The UK aid portfolio included strategic choices that responded well to Ghana’s governance challenges and its need to self-finance its development

After conducting diagnostic work on governance in 2014, DFID shifted its governance portfolio in Ghana from supporting budget and expenditure management to three new issues where it believed it could make a bigger difference: 1) anti-corruption, 2) tax policy and administration, and 3) oil and gas revenue management.

Tackling corruption

Our literature review, programme review, and interviews with representatives of the Ghanaian government, other donors and Ghanaian civil society organisations (CSOs) and think tanks, suggest that the strategic shift towards anti-corruption was a justified decision. Corruption is a key impediment to Ghana’s development and is embedded in its political economy. “Fighting corruption and economic crimes” is a major priority in the government of Ghana’s Coordinated Programmes for 2010–2016 and 2017–2024. Our consultations with citizens also highlighted the scourge of corruption, echoing Afrobarometer surveys showing more respondents reporting personal experiences of corruption over time, and fewer believing that public service providers of different kinds were not corrupt.

DFID’s anti-corruption programme is an agile, thoughtful response to Ghana’s corruption challenge. By 2014, when the anti-corruption programme started, Ghana had established a legal framework and institutions to address corruption and financial crimes. However, no major cases had been successfully prosecuted. One reason was that the technical capacities of Ghana’s anti-corruption institutions were too weak to take on what DFID’s diagnostic work described as “an operating environment with minimal accountability” where “political and social barriers” blocked effective action.

“As a result of corruption people are suffering. Roads are not well constructed because of corruption.”

Karaga transect walk

“The police and other civil and public servants also engage in petty corruption when they take advantage of the system by insisting on some payments that end up in their pockets.”

Youth Focus Group Discussion, Mion

In response, DFID’s Strengthening Actions Against Corruption (STAAC) programme embedded interventions in continuous political economy analysis, so that it could respond nimbly and seize opportunities for progress when and where these opened up. The programme targeted the entire anti-corruption chain (detection, investigation, prosecution and remedial action). This had the potential to address not only the weak capacity in individual institutions, but also weak links between them, creating pressure between institutions for cases to progress. The programme was designed to work simultaneously with government on technical state capacities and with civil society and the media to create pressure on the state to address corruption. It also supported Ghana’s participation in global anti-corruption networks and initiatives.

“A businessman pays a lot of bribes or unapproved fees.”

Mion town hall meeting

Mobilising domestic resources

DFID’s support to boost domestic tax collection and manage oil and gas revenues is relevant to Ghana’s Beyond Aid strategy, which lists higher public resource mobilisation as one of ten priority reforms. DFID’s diagnostic work identified that the oil and gas sector can address two of the binding constraints on growth (cost of energy, access to finance and macroeconomic stability) through its impact on government finances, foreign exchange earnings and energy generation. Based on this diagnostic, DFID designed its Ghana Oil and Gas for Inclusive Growth programme to provide technical support to the government of Ghana, while also working with civil society to strengthen its ability to hold the government to account on how the oil and gas windfall is spent.

The importance of channelling some of this windfall into interventions – such as accelerated investment in economic infrastructure – that can put Ghana on a new growth path is widely appreciated and has been highlighted by Ghana’s government, both in strategy documents and by its leadership.

Strengthening civil society

Our literature review, roundtable discussions and key informant interviews with Ghanaian stakeholders in the state, business and civil society sectors all confirmed that the continued activism of civil society in Ghana is necessary to break political economy constraints on the country’s growth and development. Roundtable discussions confirmed that Ghanaian CSOs see the UK as a long-standing, trusted partner.

The design of DFID CSO programming responds well to issues raised in the 2013 ICAI review of DFID’s empowerment and accountability programming in Ghana and Malawi. These were:

- Coherence in CSO engagement with the state: DFID’s CSO support programme (STAR Ghana II), its oil and gas programme and its anti-corruption programme (STAAC) all seek to avoid fragmentation by convening CSOs on common platforms to engage the state on key issues (see Box 4).

- Funding: STAR Ghana II set up the STAR Ghana Foundation, which is an effort to address CSO funding challenges in the context of declining donor funding to Ghana. While it remains to be seen whether the Foundation will be able to raise and channel significant funding to civil society in Ghana, the effort to establish a sustainable model is relevant to the country’s transformation.

- Capacity shortfalls: STAR Ghana I and II both recognised that funding civil society action should be combined with building the capacity of organisations to manage themselves better.

Box 4: Supporting civil society to engage the state

DFID’s oil and gas programme supports the African Centre for Energy Policy, an Accra-based CSO. Through its engagement with the parliamentary committees and advocacy in the public domain, the Centre ensured that oil contract transparency was written into the legal framework to manage oil exploration and production. In 2017, reports by the Centre and the Public Interest and Accountability Committee showed that many projects funded by oil revenue through the annual budget did not exist. These reports prompted new measures to monitor the projects.

STAR Ghana provided grants to CSOs to increase the influence of civil society and parliament in the governance of public goods and service delivery. In its second phase it took on more of a convening role, helping to facilitate collective civil society action on topical issues at national and local levels. At national level, the programme contributed to more collaboration between parliamentary committees and civil society, and to government being more open to civil society engagement. These shifts were hailed as significant, even if their impact on service delivery was still limited.

Responding to the needs of the most vulnerable in Ghana

DFID’s social sector programming reflects the concerns of the poor and targets population groups at risk of being left behind

Health and education are important concerns for the poor in Ghana

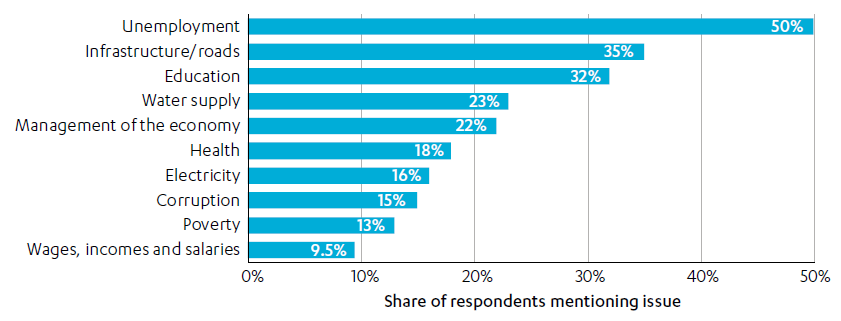

In two surveys conducted in our review period, Ghanaian respondents placed health and education, together with employment and jobs, among the top ten most important problems facing Ghana (see Figure 11 below). In the 2015 My World Survey, respondents from rural areas (where over 90% of Ghana’s poor live) selected health care most often out of 18 possible development priorities, and education third most often. In the 2017 Afrobarometer survey, over 30% of respondents (from across the country) mentioned education when asked what the most important problems facing the country were, while 18% raised health.

Figure 11: Citizens’ concerns and priorities

Most important problems in country identified by citizens*

Citizens’ development priorities**

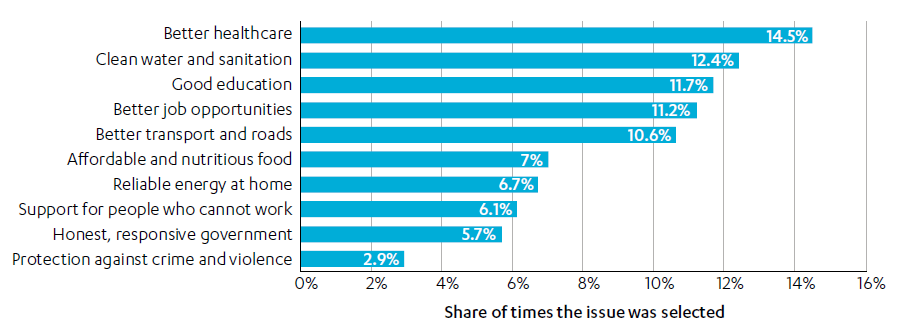

In our own consultations, citizens – especially the poor and those from remote districts – also identified education and health services as important concerns. Figure 12 lists the main development themes raised by the participants in our own citizen consultations.

Figure 12: Top issues raised by citizens in our review consultation

Citizens especially raised the quality of health and education services, drawing our attention to issues such as the lack of drugs at health facilities and furniture in schools, and the poor quality of teaching.

“The teachers in most of the public schools are not good. They can’t even speak English with the children because when the children come home and you speak English with them, they respond in the local dialect. Therefore, the children tend to be poor academically and despite spending years in school they come home with very poor results that can’t be of any help.”

Nzema East town hall meeting

“Members of this community are registered on health insurance… however, now when they go to the clinic there are no drugs.”

West Mamprusi focus group discussion

“There are no school buildings for the community.”

“A new school is being constructed. There are no teacher quarters.”

“There used to be a community health compound in my community but now it has been closed down due to low patronage. There were no drugs there and the little drugs they had had all expired.”

Participants in radio phone-in

UK aid’s support to community health care services, health commodities, health financing, education access for girls and out-of-school children, and teacher pre-service training reflects a focus on addressing some of the priorities identified by citizens, such as access to health and education services, markets and jobs, and better dialogue between citizens and authorities.

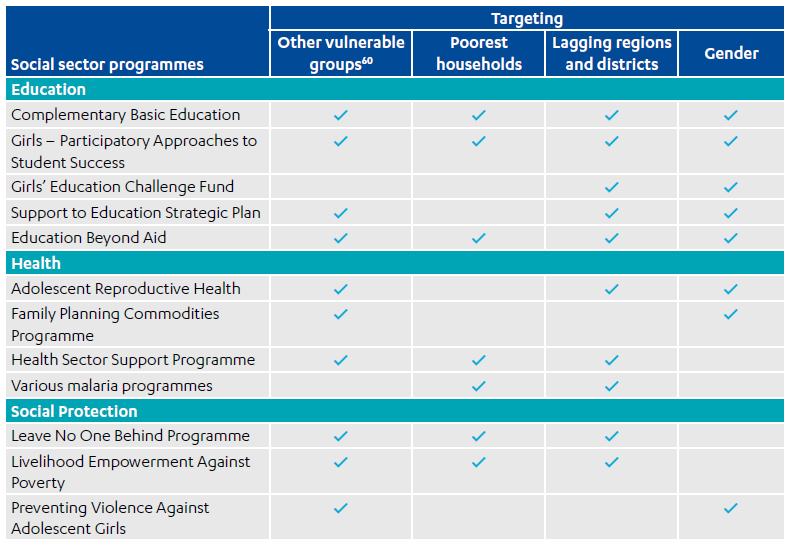

UK aid choices in Ghana show commitment to the principle of leaving no one behind

In recent years, poverty reduction in Ghana has stagnated, inequality has grown and regional disparities have widened (see Figure 5), showing a growing risk that some communities will be left behind as the country transforms, which in turn will threaten the transformation itself. Our analysis of programming in the health, education and social protection sectors shows a consistent commitment to the principle of leaving no one behind. DFID’s support to service delivery between 2011 and 2019 was targeted at vulnerable groups, the poorest households and lagging regions. Altogether 92% of bilateral UK aid expenditure in the social sectors in Ghana was targeted in full or through substantial components at groups who are (at risk of being) left behind (see Table 3).

DFID’s 2011-2015 Operational Plan made an explicit commitment to “two cross-cutting priorities: girls and women, and poverty reduction and growth in the North”. The social sector programmes were strongly aligned with these commitments. In addition, some programmes in the economic sector – the DFID market development programme and AgDevCo’s programmes in the north – were also implemented in a lagging region and aimed at the poor and vulnerable.

Table 3: Targeting of social programmes at the poor and vulnerable

However, crucial decisions on reducing aid in the social sectors were made without a sound analysis of the implications for service delivery

The average annual value of DFID Ghana’s aid to the social sector declined by 42% from the period 2011–12 to 2013–14 to the period 2016–17 to 2018–19 (see Figure 8 above). The decline in DFID Ghana’s aid was driven by a series of top-down portfolio and bottom-up programming decisions aligned to the DFID Business Plan 2016–17 to 2019–20. Reducing aid for service delivery – the financing of the direct cost of services themselves – represents a significant proportion of the reduction.

DFID Ghana noted that lower social sector spending from its country budget had been offset by increases in spending through centrally managed programmes. We were unable to ascertain the degree to which this occurred, as comparable time-series data for centrally managed programmes over the same period is not available. However, while increased spending through centrally managed programmes contributes to the overall volume of UK bilateral aid to Ghana, and may be complementary to DFID Ghana programmes, these programmes do not in and of themselves counter the implications of phasing out DFID Ghana programmes which financed service delivery.

The Business Plan was explicit that DFID Ghana’s financing of service delivery in the social sectors would be significantly reduced. This was on the basis that Ghana should be in a position to finance service delivery out of its own resources in the context of DFID’s approach to transition in Ghana. Through our interviews we heard that DFID Ghana’s country budget was reduced in response to the following factors: 1) pressing UK aid priorities elsewhere including a shift in UK aid policy towards poorer and fragile states, 2) Ghana’s lower-middle-income country status, and 3) the government of Ghana’s beyond aid vision. Ghana’s macroeconomic crisis was viewed as a temporary setback and the expectation was that the country would return quickly to rapid growth. Overall, the view was that Ghana was a country in transition, and therefore the UK-Ghana partnership was transitioning too. Downgrading the DFID Ghana office and reducing its staff in the 2016–17 period are also illustrative of this dynamic.

DFID’s Business Plan 2016–17 to 2019–20 stated that the reduced support for direct service delivery would be accompanied by “a corresponding increase in our strategic support to the systems and policies that underpin human development outcomes”. The plan noted that reducing direct service delivery would free up DFID Ghana’s human resources for policy advocacy and better coordination of centrally managed programmes.

We conducted six case studies of social sector programmes in Ghana. Of the six, five provided aid for service delivery. These programmes were affected differently by the decision to reduce this form of aid. However, we found no convincing evidence that the decisions on where aid for service delivery should be stopped and where it should continue were based on analysis of needs, sustainability of the services delivered, or capacities built. Initial programme planning documents made no reference to Ghana’s macro-fiscal crisis at the time when aid to service delivery was stopped, and did not provide an analysis of the Ghanaian government’s financial capacity to sustain services over the short-to-medium term.

Instead, we found that the programme documents were inconsistent in their focus on leaving no one behind when justifying whether to stop or continue financing services in specific projects:

- In two cases – support for mental health services and support for the livelihoods social safety net programme – aid was expected to continue in a next programming phase, through a new Leave No One Behind programme. The business case argues for continuing this support due to the importance of leaving no one behind in the Ghana Beyond Aid context, which, it was felt, places an overly strong emphasis on economic growth.

- Yet, in another programme document, DFID justifies phasing out financial support for complementary basic education (supporting out-of-school children to access schooling), by arguing that ending this funding would ‘support’ Ghana’s self-reliance in leaving no one behind and taking responsibility for investing in its own people in the Beyond Aid context.

- In the decisions to end bilateral financing of community health services and girls’ scholarships in northern Ghana, no mention is made of DFID’s leave no one behind objectives one way or another. Instead, the concept note for the follow-up technical assistance programme for the social sectors uses the changing UK development offer and Ghana Beyond Aid as the rationale for opting for technical assistance rather than the financing of services.

Citizen consultation is not a systematic part of programme design, monitoring or evaluation

Participation by, inclusion of and accountability to citizens in development processes are widely recognised principles of good development practice. Implementing these principles requires that the priorities, needs and experiences of the citizens should be part of programme design, monitoring and evaluation, especially when UK programmes deliver direct services to citizens. This is not just about broad programming choices and their alignment with what citizens prioritise, but about a careful approach to gain knowledge on what people need and want, and how they react to interventions.

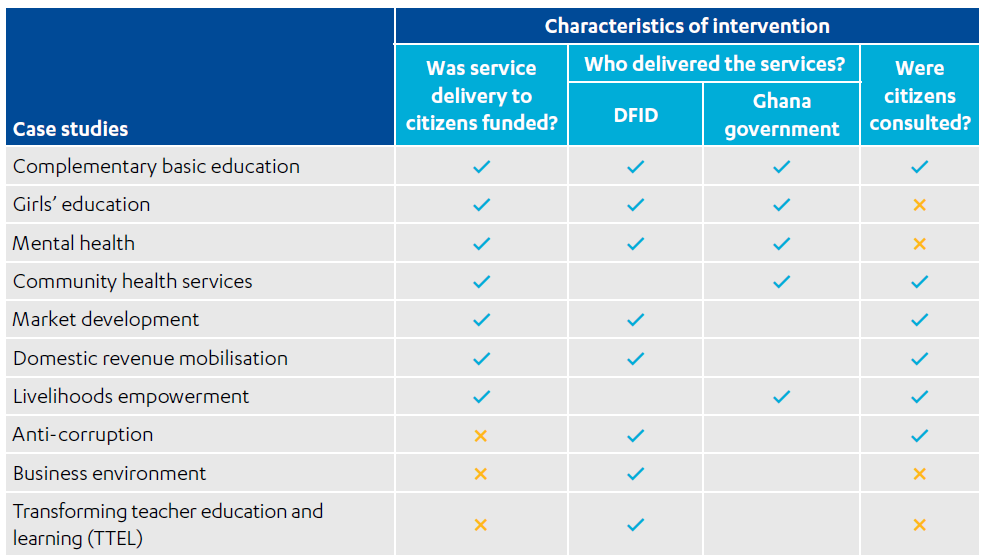

Only some UK aid programmes in Ghana used extensive and structured citizen consultation as part of programme design or implementation. For example, as Table 4 below shows, only four out of seven programmes among our ten case studies that had direct engagement components conducted citizen consultations. In the two cases where the government of Ghana was solely responsible for delivering the programme, consultation was built into programme design.

Table 4: Consultation with citizens

Consultation components can also be useful when programmes only affect citizens indirectly, for example when they have an impact on policies that affect citizens or when citizen experiences are relevant to programming choice. This was the case in the anti-corruption programme in Table 4, which surveyed citizen experiences on petty corruption despite the programme interventions not including direct citizen services.

Our interviews and programme documentation review indicate that an assessment of whether consultation is needed in programme design and implementation, and the design of such consultation methods, was not a systematic part of the operating requirements for UK aid in Ghana. Rather, it depended on the interests and beliefs of the senior responsible officer or service provider whether it was done.

Positioning the UK to support Ghana’s economic development

UK aid support for private sector development reflects the importance of economic diversification, inclusive growth and job creation for Ghana

Our literature and strategy reviews show that the transformation of Ghana’s economy from relying on the export of raw materials to being based on manufacturing and high-value services that deliver quality jobs is a central priority for the country’s government. Creating jobs is also a priority for Ghana’s citizens. In 2017, well over 40% of respondents to the Afrobarometer survey mentioned jobs when asked about the three most important problems facing the economy. The lack of jobs and livelihoods, especially for young people, were also raised in our own consultations with citizens. In the Northern region, West Mamprusi community members expressed concern that many young people were not working. Although agriculture was the main occupation in the community, young people did not want to work in that sector.

Secondary and interview evidence identifies several barriers to inclusive growth: the business environment and the cost of doing business (especially the cost of energy and finance), firm capability and capacity, human capital, macroeconomic instability and vulnerability to shocks. In response, DFID’s private sector development portfolio includes interventions to improve the business environment, working with Ghana’s Ministry of Trade and Industry, metropolitan areas and the commercial courts. It has also supported the Ministry of Trade and Industry on industrial policy, and built capacity in small and medium enterprises.

In the last few years, DFID has significantly increased its market development activities in neglected parts of the country, through Market Development in Northern Ghana (MADE) and AgDevCo’s investments in emerging agriculture firms in northern Ghana to create value chains for poor producers. This reflects our literature review findings and interview evidence, as well as DFID’s diagnostic that a growing urban-rural and regional economic divide is a barrier to inclusive development.

Central programming to support regional food markets, and a forthcoming programme evolved from MADE to develop the agriculture sector in the north, are aligned to DFID’s diagnostic finding and our literature review findings that the agricultural sector presents a key entry point for economic transformation and provides opportunities for regional trade.

The UK’s broad cross-departmental approach to Ghana’s economic development was a coherent and coordinated response to the government of Ghana’s beyond aid priorities

The government of Ghana has clearly expressed that it wants its partnerships to transition over time from aid to trade and strategic economic cooperation. It has asked that development partners help raise additional funds for development through market-based transactions and leveraging private capital.

Since 2018 the UK government, through the Economic Development Investment and Trade (EDIT) working group and the UK-Ghana Prosperity Strategy, has coordinated a broad range of instruments from different UK departments and bilateral and multilateral funds to support Ghana. The ambition is for shared learning, leveraging interventions and presenting a coherent narrative about the UK offering to Ghana. Key participating departments and funds are DFID, the FCO, the Department for International Trade, CDC (the UK’s development finance institution), the Private Infrastructure Development Group and UK Export Finance (UKEF).

The ambition of the EDIT working group is to coordinate all UK official flows better in the interests of the mutual prosperity of Ghana and the UK. This carries risks for UK development assistance (see the next finding) but may also allow the UK to use its assets more effectively in leveraging private capital for development. The initiative supports the UK-Ghana Business Council, which brings the two governments together to reduce barriers to trade and investment and create jobs. In 2018, UK aid funded a UK-Ghana investment summit, attached to the first meeting of the business council. The council and summit were frequently mentioned to us by Ghanaian government ministers as a prime example of how the UK is a leading development partner in forging a new relationship with Ghana.

Box 5: UK aid-supported efforts to leverage private capital

The Private Infrastructure Development Group (a multi-donor initiative) has three operational projects in Ghana and commitments to support a further ten. Its development model is to make it more viable for private investors to participate in infrastructure deals, by using ODA as seed funding to crowd in private capital.

CDC made 52 direct or intermediated investments in Ghana over the review period. CDC is the UK’s development finance institution and primary vehicle through which DFID invests development capital, by supporting businesses in Africa and South Asia that have potential for creating jobs and driving development impacts. In Ghana, CDC’s investments were largely in energy and agriculture, not necessarily based on the objectives of the UK’s aid strategy in Ghana. More recently, there has been more of an effort to coordinate between CDC and other UK interventions. CDC attends the UK-Ghana Business Council, but does not yet have a presence in Ghana.