DFID’s transport and urban infrastructure investments

ICAI score

Good performance on strategic approach and supporting multilateral finance, but a mixed record in the delivery of bilateral programmes

DFID’s transport and urban infrastructure work supports its strategic priorities of promoting prosperity, tackling extreme poverty and strengthening resilience in developing countries. DFID has clearly identified its niche in the sector, including the provision of technical assistance and policy advice and its flexible use of grants to leverage other sources of funding. Its investments are selected and designed so as to support economic growth. However, it lacks a systematic approach to inclusion: while some programmes specifically target the poorest and most marginalised groups, its growth-focused bilateral programmes do not pay enough attention to enhancing benefits for the poorest, women or people with disabilities.

We find considerable variation in performance across DFID’s portfolio. Most programmes eventually delivered their outputs, but with frequent delays and implementation challenges and mixed performance at outcome level, often linked to unrealistic timetables and targets. DFID’s technical assistance has helped national counterparts achieve their objectives, but DFID could be doing more to tackle deep-seated governance challenges in the sector. DFID relies on its multilateral partners to implement appropriate social and environmental safeguards, including protecting beneficiaries from harm. While the department has worked actively at the global level to strengthen multilaterals’ safeguarding policies, it is not active enough in ensuring there is adequate implementation capacity in-country.

Value for money is managed appropriately across the portfolio, through economic appraisals and monitoring of costs. However, DFID’s short programme duration, compared to the time required to design and build major infrastructure, creates value for money risks.

DFID has been broadly successful at helping partner countries access and make better use of other sources of finance, including by funding project preparation costs. It is the major funder of the Private Infrastructure Development Group, which has stimulated private investment for infrastructure in developing countries. DFID’s research partnerships with the multilateral development banks have been strong and have helped raise standards and practices across the sector. DFID and other UK departments are increasingly engaging with China to improve its infrastructure funding practices, but DFID could be doing more to help partner countries understand the full costs of China’s transport and urban infrastructure finance.

| Individual question scores | |

|---|---|

| Question 1 Relevance: Does DFID have a coherent approach to promoting economic development and poverty reduction through transport and urban infrastructure development? |  |

| Question 2 Effectiveness: How effective are DFID’s bilateral transport and urban infrastructure programmes? |  |

| Question 3 Effectiveness: How well does DFID use bilateral aid to enhance the effectiveness and value for money of multilateral infrastructure finance? |  |

Executive summary

Transport and urban infrastructure are key ingredients for economic growth and poverty reduction. Rural roads and bridges give poor people access to vital public services and markets to sell their goods, while highways, railways and ports link economically deprived areas to national and regional trading opportunities and can help reduce the prices of goods for consumers. Cities in developing countries will gain almost two billion new residents in the next two decades, putting urban infrastructure – including public transport, waste management and energy supply – under enormous strain. Growing cities can be engines of economic growth, but without well-planned infrastructure they can generate poverty and deprivation. At present, experts agree that investment in transport and urban infrastructure in developing countries falls well below the level required to support economic growth and achieve the Sustainable Development Goals.

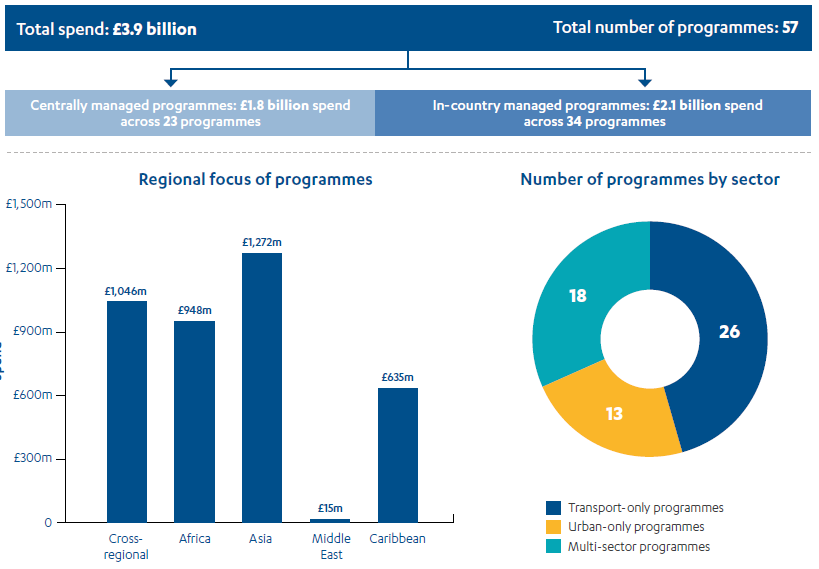

This review examines DFID’s bilateral programming on transport and urban infrastructure, which over 2015 and 2016 consisted of 57 programmes with combined budgets of £3.9 billion. Compared to the multilateral development banks, which between them provide over £15 billion in transport infrastructure loans each year, DFID is not a major funder of transport infrastructure and usually prefers to leave the funding of large capital projects to others. However, it does invest directly in infrastructure where other sources of finance are limited. It also helps its partner countries to strengthen their policies and institutions for infrastructure development and to access other infrastructure finance.

The review looks at whether DFID has a coherent overall approach to its transport and urban infrastructure work. It then assesses the effectiveness of DFID’s support for transport and urban infrastructure development in partner countries, and how well it uses bilateral programmes to enhance the effectiveness and value for money of other sources of infrastructure finance. We chose a sample of 13 projects (a third of DFID’s transport and urban infrastructure portfolio by value) for detailed review, visiting three countries – Uganda, Kenya and Pakistan – to interview stakeholders. The sample includes programmes that invest directly in infrastructure, support for policy and institutional development, research programmes and initiatives that help mobilise other sources of infrastructure finance.

Does DFID have a coherent approach to promoting economic development and poverty reduction through transport and urban infrastructure development?

DFID’s approach to infrastructure is set out in its 2015 infrastructure strategy. It invests in transport and urban infrastructure for a range of purposes in different contexts. We find that its portfolio supports three of the four strategic objectives in the UK aid strategy, namely:

- Promoting global prosperity, through efforts to fill strategic infrastructure gaps, promote regional transport infrastructure, build national capacity and mobilise more finance for infrastructure.

- Tackling extreme poverty and helping the world’s most vulnerable, including through building community-based infrastructure for remote communities and promoting road safety standards.

- Strengthening resilience and response to crisis, through reconstruction of infrastructure in conflict-affected areas and investments designed to increase resilience to climate change, especially in urban areas.

DFID has also identified urban infrastructure as a new priority, in recognition of the central role of cities and towns in economic growth and poverty reduction and the accelerating impacts of climate change. Though a challenging area of work, this addresses an important need.

We find that DFID has a clear approach to selecting transport and urban infrastructure investments that support economic growth. In Pakistan, it is investing in highways that link more deprived areas to wealthier provinces, as well as leveraging further investment for infrastructure, fuelling economic growth. In East Africa, DFID is investing in border crossings, port facilities and customs processes, in order to facilitate regional trade. In Uganda, where the government had prioritised transport but was paying too much for road construction, DFID employed an innovative approach to overcoming bottlenecks in the construction and finance sectors, to bring down costs. DFID also has a clear rationale for its emerging focus on urban infrastructure, linked to the potential of well-managed cities and towns to act as growth hubs.

We find the approach to poverty reduction and the inclusion of women and marginalised groups to be inconsistent. In our sample, there are a number of investments and research programmes that directly target the poor and marginalised groups. These include a programme designed to reduce the isolation of remote communities in western Nepal and a research project exploring how to bring down the global toll of road accident deaths, which disproportionally affects the poor. The portfolio also shows a clear geographical focus on the poorest states and areas within states. However, for those programmes focused specifically on economic growth, insufficient consideration is given to enhancing poverty reduction and meeting the needs of women, people with disabilities and other marginalised groups.

DFID has clearly identified its areas of comparative advantage, fitting alongside the multilateral development banks and other development partners. These include its strengths in policy dialogue, research and institutional reform, its relatively high risk appetite and its ability to provide flexible grant finance. We found that its infrastructure work generally matches the areas of focus identified in its infrastructure strategy. DFID

has also identified urban infrastructure as an area where it would like to build its portfolio. It has been using centrally managed programmes to provide country offices with additional technical capacity in this area. While useful, this is only a partial solution to boosting the department’s capacity to deliver complex urban infrastructure programmes. DFID country offices still need the capacity in-house to manage stakeholder relationships and oversee complex programmes.

We find a number of gaps in DFID’s infrastructure strategy. It does not consider how DFID’s bilateral programmes fit alongside those of its development finance institution, CDC, or of other UK aid-spending departments. It does not assess the implications for developing countries of the growing importance of Chinese infrastructure finance, including its impact on quality standards and debt sustainability. We would also expect to see DFID’s investment choices in particular countries underpinned by more detailed analysis of the extent and causes of gaps in key infrastructure.

Overall, we award DFID a green-amber score for relevance, for the clear strategic alignment of its transport and urban infrastructure work to its strategy and to its partner countries’ infrastructure needs, and for some strong programme designs. However, its approach needs to improve in a number of areas, particularly on inclusion.

How effective are DFID’s transport and urban infrastructure programmes?

In this section, we look at the effectiveness of DFID’s investments in transport and urban infrastructure in its partner countries. We find considerable variation in performance across our sample, both within and between programmes. Most programmes eventually delivered their planned activities and investments (‘outputs’), but with frequent delays and implementation challenges. The programmes have had mixed success at achieving their intended results (‘outcomes’):

- The Rural Access Programme in Nepal has constructed 97.5km of new roads and maintained 2,200km of existing roads, improving all-weather access for 2.1 million people and creating employment for 8,100 people on road construction and maintenance. It delivered well on both output and outcome targets.

- A post-conflict reconstruction programme in Pakistan rebuilt 66 bridges that had been destroyed by flooding and conflict, used daily by 67,000 pedestrians and 36,000 vehicles. However, it was subject to delays caused by adverse weather and the low capacity of local authorities.

- The TradeMark East Africa programme invested in improvements at the port of Mombasa, Kenya, significantly reducing the time required to import and export goods through the port. However, the expected increase in trade volumes has not materialised. The programme has refocused its activities on bringing down the costs of trade.

- The multi-donor Afghanistan Infrastructure Trust Fund struggled to spend its funds effectively, due to a range of factors including the insecure environment, poor coordination with donors, contracting challenges and a limited pool of suppliers. DFID eventually had to recover £26 million in unused contributions.

This mixed pattern of results reflects the fact that transport and urban infrastructure programmes are complex to deliver and prone to a range of risks, often linked to dependency on other actors. The mixed picture also shows that DFID needs to manage delivery risks more actively, assign realistic timelines for complex projects and deploy staff with sufficient experience in the sector to intervene and resolve problems when they occur.

Developing sustainable transport and urban infrastructure often requires changes to national policies and institutions. DFID’s approach to technical assistance has been effective in helping counterpart agencies address practical challenges, but is less suitable for addressing deep-seated institutional problems. Within our sample, the CrossRoads programme in Uganda was the most ambitious attempt to tackle corruption and vested interests in the transport sector. It succeeded in introducing various innovations, including new policies, improved procurement, new vocational training programmes and a construction guarantee fund to encourage Ugandan banks to lend to local contractors. It achieved significant reductions in the cost of maintenance works and a 30% increase in national funding for road maintenance. This was a good example of politically informed technical assistance, even though changes to the wider external political environment have threatened the sustainability of some of its results. Beyond this programme, we find that DFID could be doing more to address governance challenges in transport and urban infrastructure.

In the infrastructure sector, ‘safeguarding’ refers to the protection of communities and the environment from inadvertent harm, for example through acquisition of land, road accidents, unsafe work practices or the disruption of ecologically sensitive habitats. This also includes protecting vulnerable people from sexual abuse and exploitation, which is a risk in infrastructure projects given the concentration of unaccompanied men at work sites. DFID’s practice is to rely on the safeguarding policies of its multilateral partners. It has worked with them in recent years at the central level to strengthen their policies. However, implementation at country level can be very challenging – as demonstrated by serious safeguarding lapses on a World Bank project in Uganda in 2015 (see Box 11). Although DFID was not funding this project, the case highlighted poor practices on safeguarding within the sector. We find that DFID is not active enough in ensuring that the multilateral development banks and their national counterparts have adequate systems and capacities in place to implement safeguard policies at country level.

Compulsory acquisition of land from citizens, with compensation, is a significant challenge for infrastructure projects, particularly in urban areas where land prices are high. It comes with human rights risks, including forced displacement of poor communities and infringement of women’s rights, and is a significant cause of delay for projects. DFID relies on national governments to resolve these issues but, as the World Bank found in Uganda, they often lack the capacity to do so. DFID’s transport and urban infrastructure work would benefit from boosting their capacity to provide specialist assistance in this area.

DFID has an active approach to managing value for money across the portfolio. It assesses the likely economic return on each programme in its business case. We found that these analyses were generally adequate, although they would be strengthened by a more standardised methodology which would improve their rigour and subsequent usefulness for performance monitoring. DFID also tracks value for money indicators over the life of each programme. However, there is a mismatch between the eight to ten years typically required to design and implement infrastructure programmes and the usual three-to-five-year length of DFID programmes. This creates unrealistic time pressures, with the risk that key processes such as community consultation are truncated, as occurred in one of our sample programmes. It also means that funds may not be disbursed or investments completed until after DFID’s programmes have closed, which reduces DFID’s ability to monitor value for money and learn lessons.

Overall, we find that the mixed pattern of results across the portfolio and inadequate monitoring of safeguarding practices merits an amber-red score for effectiveness.

How well does DFID use bilateral investments to enhance the effectiveness and value for money of multilateral and other infrastructure finance?

A key part of DFID’s transport infrastructure portfolio is helping partner countries access and make better use of other sources of infrastructure finance. It uses grant funding to help partner governments cover the costs of preparing projects and assembling complex financing details – particularly for regional infrastructure programmes in Africa. DFID is also the largest donor to the Private Infrastructure Development Group, a global initiative that works to overcome barriers to private investment in infrastructure in developing countries. The initiative has enjoyed considerable success, raising £23 for every £1 invested, with the largest share coming from the private sector.

DFID invests in research on transport infrastructure to promote knowledge on cross-cutting issues, such as road safety, and to influence standards and practices across the sector. It has a number of knowledge-based partnerships with the World Bank, linked to developing the capacity building of national governments to make greater use of research findings. We find that the work has been very successful. The Global Road Safety Facility, based at the World Bank, has developed new standards and approaches on road safety issues, influencing both the World Bank (which in 2015 made road safety a mandatory component of all road projects) and partner country governments. The Research for Community Access Partnership develops low-cost solutions for rural roads, and we found evidence of resulting uptake of new road standards by national governments in several DFID partner countries. It has also conducted research into the transport needs of women and people with disabilities.

China’s growing importance as a funder of infrastructure offers potential benefits to developing countries but also carries risks around debt sustainability and sometimes lower technical, social and environmental standards. The UK engages with China on infrastructure finance in various ways. It is a founding member of the new China-led Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank, through which it hopes to influence construction standards and safeguarding policies. It also engages with the Chinese government through the G20 on debt sustainability and environmental standards. In Uganda, we were told that a DFID programme (outside our sample) was working with the ministry of finance to help it understand the full economic cost of its infrastructure finance. However, there is scope for DFID to do more to help its partner countries become more sophisticated consumers of infrastructure finance.

Overall, we find that DFID merits a green-amber score for its influencing efforts with multilateral banks, its investments in project preparation and finance facilities and its high-quality research work.

Conclusions and recommendations

We offer a number of recommendations to help DFID strengthen its transport and urban infrastructure work.

Recommendation 1

In the continuing development of its infrastructure strategy and guidance, DFID should address the need for the following:

- a more rigorous approach to project selection and clear expectations around economic analysis, with a range of tools and approaches

- a strong focus on identifying and addressing governance and market failures that inhibit sustainable infrastructure development

- realistic timetables and how to manage investments lasting beyond a single programme cycle

- stronger programme supervision and risk management processes

- a more systematic approach to enhancing impact on poverty reduction and ensuring the inclusion of women, people with disabilities and marginalised groups, including monitoring intended and unintended impacts on target groups.

Recommendation 2

When funding infrastructure through multilateral partners, DFID should ensure that there are adequate safeguarding systems and the capacity to implement them in place at country level (including in national counterpart agencies), and verify that this remains the case throughout the life of the programme.

Recommendation 3

To improve its ability to manage complex infrastructure programmes, particularly urban programmes, DFID should give its centrally managed programmes a stronger role in supplementing its in-country infrastructure advisory capacity. This might include embedding experts into country offices during the design and inception phases of new programmes, and providing additional support as needed throughout the life of the programme on specialist issues such as land acquisition and safeguarding.

Recommendation 4

DFID should clarify how it will work with China and other new donors on infrastructure finance, and prioritise helping partner countries become more informed consumers of infrastructure finance.

Introduction

Transport and urban infrastructure are key ingredients for promoting economic growth and poverty reduction. In rural areas, local roads allow poor communities to access public services, such as health and education, and to bring their agricultural produce to market. Major transport infrastructure, including highways, railways and ports, helps to expand trade, make business more productive and reduce prices for consumers. Cities and towns in developing countries are growing rapidly, placing strains on existing infrastructure. Cities that are well served with infrastructure can become engines of inclusive growth, but if they are poorly planned they can exacerbate poverty and deprivation.

Globally, rates of investment in infrastructure fall well short of the level required to sustain quality of life and economic growth, especially given the impacts of climate change and rapid urbanisation. The World Bank estimates that an additional trillion dollars of annual investment is needed in developing countries to sustain existing economic growth rates. The Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) call for the development of resilient infrastructure, including improved road safety and better urban transport (see Box 1).

Box 1: Infrastructure and the Sustainable Development Goals

The Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), also known as the Global Goals, are a universal call to action to end poverty, protect the planet and ensure all people enjoy prosperity and peace. Transport and urban infrastructure will play a vital supporting role in achieving many of the SDGs.

Related to this review:

![]() SDG 1: end poverty in all its forms everywhere aims to tackle poverty through economic growth and universal access to basic services. Improvements in transport and urban infrastructure serving the poorest will be vital to achieving this. Goals 3 and 4, on health and education, also imply the improvement of transport infrastructure for the underserved.

SDG 1: end poverty in all its forms everywhere aims to tackle poverty through economic growth and universal access to basic services. Improvements in transport and urban infrastructure serving the poorest will be vital to achieving this. Goals 3 and 4, on health and education, also imply the improvement of transport infrastructure for the underserved.

![]()

SDG 9: build resilient infrastructure, promote inclusive and sustainable industrialisation and foster innovation calls for affordable and equitable access for all to infrastructure. This includes indicators assessing access to all-weather roads and the growth of passenger numbers for different modes of transport.

![]()

SDG 11: make cities and human settlements inclusive, safe, resilient and sustainable calls for inclusive and sustainable urbanisation. It seeks improvements in infrastructure planning in urban areas on issues such as

waste management, transport, climate change mitigation and adaptation and resource-efficiency.

![]()

SDG 12: ensure sustainable consumption and production patterns. Target 12.7 is about sustainable procurement practices and policies, a key element in efforts to improve transport and urban infrastructure.

![]()

SDG 13: take urgent action to combat climate change and its impacts. To support adaptation and mitigation, existing and future transport and urban infrastructure will have to be reconfigured.

![]()

SDG 17: strengthen the means of implementation and revitalise the global partnership for sustainable development. Partnerships between regional bodies, international organisations and multilateral development banks as well as public-private partnerships will become increasingly important as a way of delivering transport and urban infrastructure.

This is a review of DFID’s bilateral investments in transport and urban infrastructure, which over 2015 and 2016 consisted of 57 programmes with combined budgets of £3.9 billion. This will be the first external review of DFID’s infrastructure work since a report by the International Development Committee in 2011. It builds on our 2017 review of DFID’s approach to supporting inclusive growth in Africa.

DFID’s long-standing transport infrastructure work focuses mainly on land transport (road and rail), but with elements of water transport (inland and ports) and air transport. Its urban infrastructure portfolio is more recent, and includes public transport and motorised and pedestrian traffic, as well as energy, water and sanitation, and housing. Its programmes include investments in building infrastructure and work on policies (such as road safety), and institutions (such as for urban planning and road maintenance systems). Compared to the multilateral development banks – which together provide around £15 billion per year in transport infrastructure loans alone – and non-traditional partners such as China, DFID is a relatively modest funder of infrastructure. It therefore focuses much of its portfolio on mobilising or influencing other sources of infrastructure finance.

DFID also provides capital investment for infrastructure through its development finance institution, CDC, and there are infrastructure-related programmes within the cross-government Prosperity Fund. However, CDC and the Prosperity Fund are the subject of other ICAI reviews and are not covered here.

Because transport infrastructure is a well-established portfolio with substantial expenditure, we decided to conduct a performance review, looking at the quality of the design and delivery of projects and the results that are being achieved (see Box 2 for ICAI’s review types). We recognise, however, that urban infrastructure is a more recent area of work where DFID is still determining how best to engage. We therefore have fewer urban infrastructure projects in our sample and focus mainly on DFID’s plans for the coming years.

Box 2: What is an ICAI performance review?

ICAI performance reviews take a robust look at the effectiveness and value for money of aid programmes, with a strong focus on accountability. They also explore the adequacy of DFID’s systems, processes and capacity, exploring how these are linked to patterns of performance in different sectors and areas.

Other types of ICAI reviews include impact reviews, which examine results claims made for UK aid to assess their credibility and their significance for the intended beneficiaries, learning reviews, which explore how knowledge is generated in novel areas and translated into credible programming, and rapid reviews, which are short, real-time reviews examining an emerging issue or area of UK aid spending.

Our review questions (see Table 1) assess whether DFID has a coherent overall approach to its transport and urban infrastructure work, and the effectiveness of DFID bilateral programming in two areas: its investments in transport and urban infrastructure programmes in its partner countries and its efforts to influence multilateral and other infrastructure finance.

Table 1: Our review questions

| Review criteria and questions | Sub-questions |

|---|---|

| 1. Relevance: Does DFID have a coherent approach to promoting economic development and poverty reduction through transport and urban infrastructure development? | • How well does DFID’s transport and urban infrastructure work support the objectives of the UK aid strategy and its commitment to promoting economic growth? • How well are DFID’s transport and urban infrastructure activities aligned around a clear idea of its comparative advantage? • How inclusive is DFID’s approach to transport and urban infrastructure? |

| 2. Effectiveness: How effective are DFID’s bilateral transport and urban infrastructure programmes? | • How well does DFID maximise value for money through project selection and delivery? • How well have DFID’s transport and urban infrastructure projects achieved their intended outputs and outcomes? • How well does DFID help partner countries establish policies and institutions conducive to sustainable transport infrastructure development and management of cities? |

| 3. Effectiveness: How well does DFID use bilateral investments to enhance the effectiveness and value for money of multilateral and other infrastructure finance? | • How well have DFID programmes helped to improve infrastructure investments by the multilateral development banks? • How well have DFID programmes helped partner countries to access additional infrastructure finance? |

Methodology

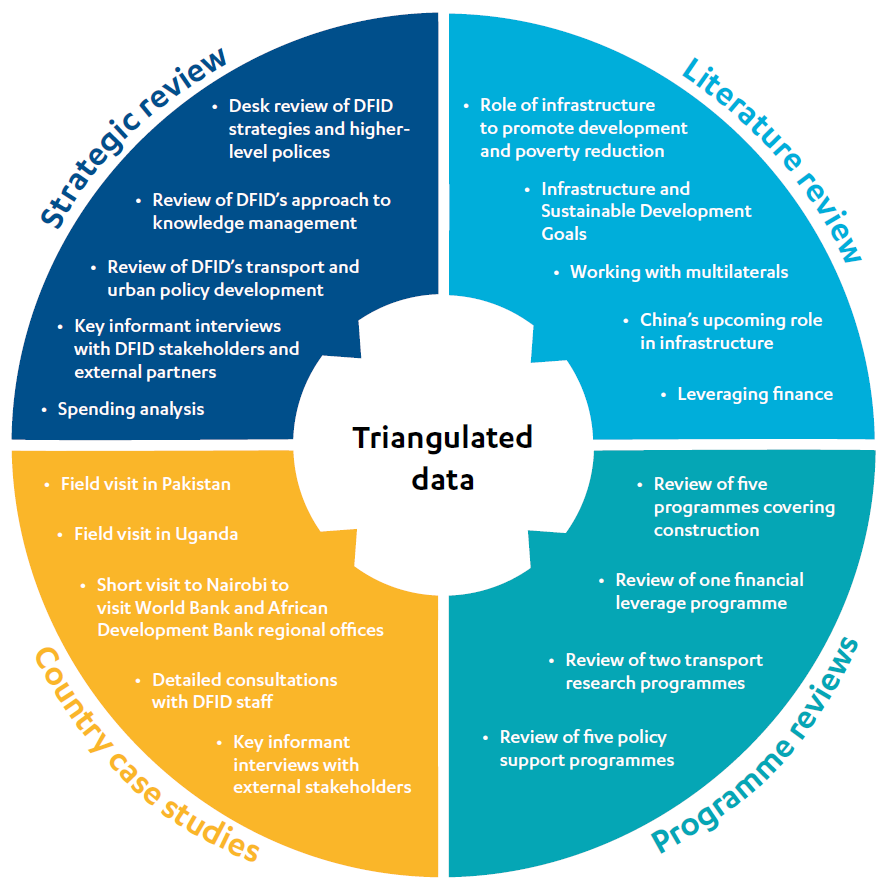

Our methodology for the review consisted of four main components, summarised in Figure 1.

- Strategic review: We reviewed DFID’s strategies and guidance on transport and urban infrastructure against the department’s overarching goals and cross-cutting commitments, such as environmental protection and inclusion of women and marginalised groups. We reviewed whether DFID had clearly identified its comparative advantage in transport and urban infrastructure. We reviewed how DFID applied value for money principles to the portfolio and how well it has addressed gaps in knowledge and data.

- Literature review: From the wider literature, we collected evidence on the global infrastructure finance gap, changing patterns of global infrastructure finance (including from traditional donors, China and the private sector), and how bilateral donors work with and influence the multilateral development banks.

- Programme reviews: We selected 13 bilateral programmes for detailed review, using a purposive sampling approach to ensure coverage of the broad range of objectives and modalities that DFID employs. Their combined budget of £1.46 billion accounts for 37% of DFID’s transport and urban infrastructure programming during our review period. By expenditure, the sample is 35% transport, 5% urban infrastructure and 60% mixed or relating to the infrastructure sector as a whole. The programmes in our sample are listed in Annex 1.

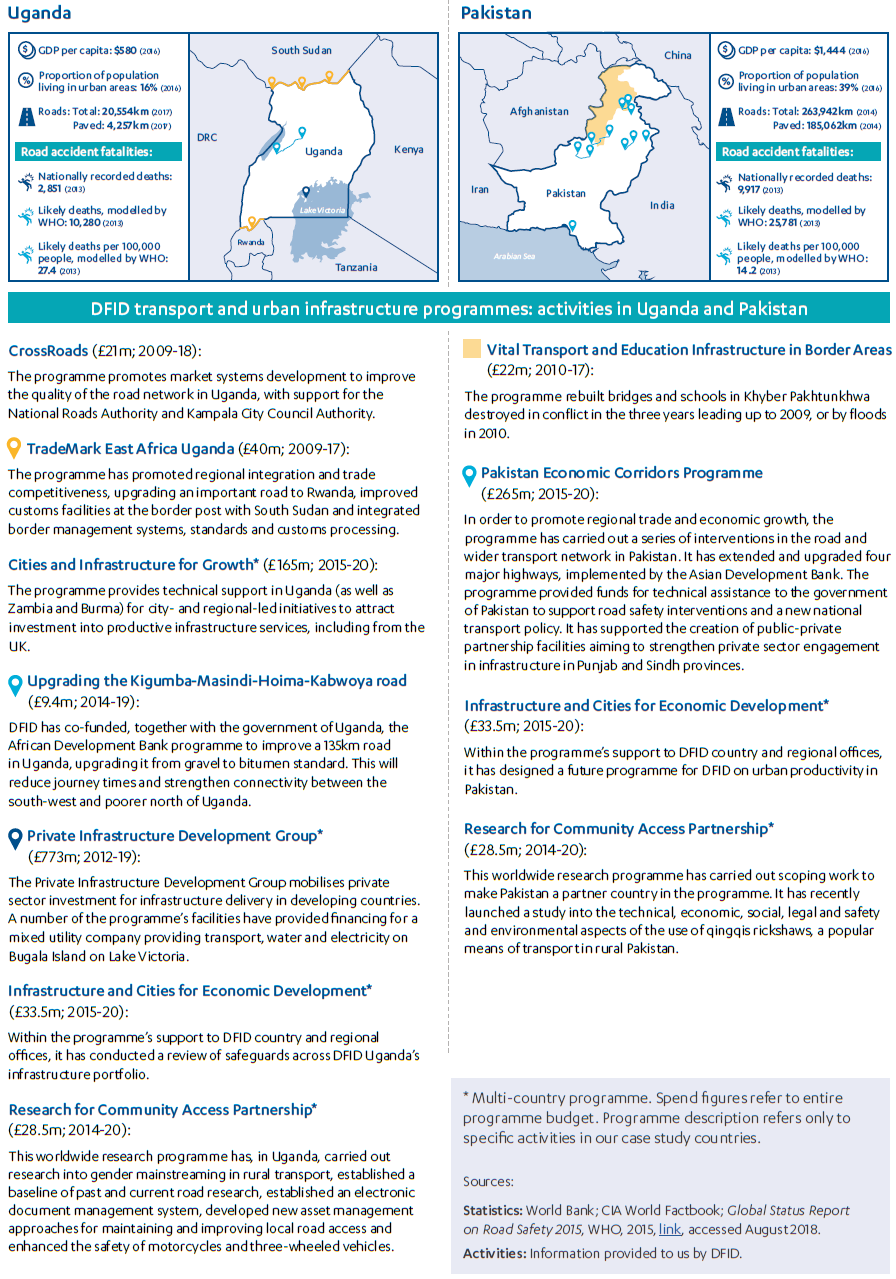

- Country case studies: We prepared more detailed case studies of DFID’s infrastructure portfolios in Uganda and Pakistan, including country visits. These countries were selected as they offered contrasting country contexts, significant expenditure within our scope and a mixture of centrally managed and in-country programmes, as well as multilateral partnerships (see Figure 4). We also undertook a brief visit to Nairobi, Kenya, to meet with officials from the regional World Bank and African Development Bank offices and other key stakeholders. The case studies enabled us to interview a range of external partners and national counterparts, to triangulate findings from the programme reviews and to explore the quality of DFID’s partnerships with the multilateral development banks.

Box 3: Limitations to our methodology

While our sample is reflective of the diversity of DFID’s transport and urban infrastructure work, it includes only a small number of examples from each category of programme. Our sample is therefore not necessarily representative of DFID’s entire transport and urban infrastructure portfolio. We nonetheless expect our findings to have broader relevance across DFID’s infrastructure work.

Our review of DFID’s work with multilateral development bank partners focuses on the use of bilateral programmes (principally centrally managed programmes) to influence their operations. It does not cover the full range of influencing activities, such as multilateral replenishments or DFID’s Multilateral Development Review process.

Figure 1: Components of the methodology

Background

Infrastructure and international development

DFID’s priority countries in sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia face critical infrastructure gaps, which hamper their ability to stimulate economic growth and reduce poverty. In 2014, the World Bank estimated that developing countries spent around $1 trillion (£760 billion) on infrastructure each year, but would need to at least double their rate of expenditure just to sustain existing economic growth rates, let alone meet the costs of responding to climate change. Africa currently has a road density (km of road per square km of territory) of 0.04, compared to 1.3 in India and 2.1 in Europe.

Transport infrastructure is key to economic growth. It is estimated that poor road, rail and port infrastructure adds 30% to 40% to the cost of goods traded in Africa. It is also key to ensuring that growth is inclusive. Over the past decade, Africa’s economic growth has been concentrated in capital cities and resource-rich areas. Improved transport infrastructure can help remote areas and landlocked countries to benefit from that growth. In South Asia, improved transport connections would help link deprived regions to regional trade opportunities. At the local level, all-weather roads help remote communities to access public services such as hospitals and schools and bring their goods to market.

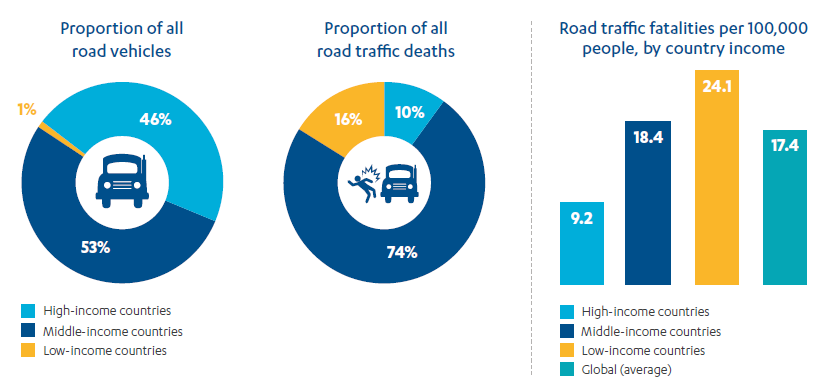

Poorly planned and managed transport infrastructure has negative effects on poor communities in developing countries. The poor are more likely to travel on foot or by bicycle, and are therefore more at risk from increased vehicle numbers and speeds. World Health Organization figures show that 90% of global accident fatalities are in low- and middle-income countries, despite having only 54% of the world’s vehicles (see Figure 2). Low-income countries have 24.1 road traffic fatalities per 100,000 people, compared to 9.2 in high-income countries, and the toll of people sustaining serious injuries from road accidents is also far higher. The solutions to this challenge are complex and include improving land-use planning so as to limit the concentration of housing and small business alongside major roads, designing roads with pavements and pedestrian crossings, improving vehicle safety standards and enforcing speed limits.

Figure 2: Road traffic deaths by country income in 2013

Rapid urbanisation across the developing world adds urgency to the challenge. For the first time in history, more than half of the world’s population live in cities and urban populations in developing countries continue to grow by an estimated 70 million people per year. Cities account for around 80% of global economic activity and are an engine of economic growth and poverty reduction. However, rapid urbanisation places huge strains on infrastructure and, if poorly planned, can generate new social and environmental problems, including the growth of slums.

Transport and urban infrastructure are vulnerable to the impacts of climate change, including increased flooding. The World Bank estimates that the cost of adapting existing and planned infrastructure to reduce greenhouse gases and withstand an increasingly volatile climate adds another £155 billion a year to global infrastructure financing needs.

It is estimated that developing countries need to spend 5% to 6% of gross domestic product on developing and maintaining infrastructure, but in practice most fall well short of that benchmark. Official development assistance (ODA) is not large enough to fill the gap. For that reason, many donors are focusing on using their aid to mobilise other sources of infrastructure finance, especially private finance. This is more challenging for road transport than other infrastructure sectors, as most roads do not generate a revenue stream. To create a financial return for investors (as distinct from a broader economic return for society), governments need to set up toll roads through public-private partnerships, but these are challenging in low-income countries where tolls may be inappropriate for equity reasons and where the risks for investors may be too high. Most of the existing examples can therefore be found in relatively advanced middle-income countries, such as Brazil, India and Turkey.

In recent years, China has emerged as a major financier of infrastructure projects across Asia and Africa, including through its Belt and Road Initiative, a highly ambitious trillion-dollar programme of global infrastructure investments. Its investments are often tied to the use of Chinese construction firms and may come without the same level of quality standards and environmental and social safeguards imposed by the multilateral development banks. While China and other new donors such as India and Brazil are important new sources of infrastructure loans, their finance is not necessarily cheaper. For DFID and other development partners, influencing infrastructure practices and standards among new donors and ensuring that partner indebtedness does not rise unsustainably have emerged as important objectives.

Alongside the high costs, building infrastructure in developing countries involves resolving a range of institutional challenges. Supportive policies and regulations need to be developed, and managerial and technical skills enhanced. Investment decisions are often taken for short-term political reasons, rather than for their contribution to national development, and infrastructure projects are prone to corruption. Acquiring land for infrastructure development is challenging in contexts where land rights are unclear, and can raise human rights issues that need to be sensitively managed. Developing urban infrastructure poses particularly complex political and institutional challenges, owing to the number of national and local authorities involved. For road infrastructure, matching donor-funded capital investment with adequate maintenance expenditure by national authorities is an additional challenge. Without maintenance, infrastructure degrades quickly, undermining the value of the investment.

DFID’s infrastructure work

In 2012, following encouragement by the International Development Committee, DFID developed a strategy for its infrastructure work, setting out its priorities. This was followed by a more refined policy in January 2015 (the infrastructure strategy). DFID also produced an internal policy framework on urbanisation, which was never published but is reportedly in use internally.

In 2015, DFID country offices undertook an inclusive growth diagnostic exercise, to analyse constraints on and opportunities for inclusive growth and opportunities for DFID influence. Of the 22 country teams that participated, 18 identified inadequate transport infrastructure as an important constraint on growth. This led to a strong focus in DFID’s January 2017 Economic Development Strategy on developing infrastructure to support trade and on encouraging private finance to close financing gaps and support sustainable cities.

These strategies recognise that DFID invests in infrastructure for a variety of reasons in different contexts, including to promote economic growth, reduce extreme poverty, support post-conflict recovery and build resilience in the face of climate change. DFID also funds infrastructure development in the UK’s ODA-eligible overseas territories (see Box 4). The infrastructure strategy analyses DFID’s comparative advantage alongside other development actors, particularly the multilateral development banks. It notes that some types of infrastructure (such as local community infrastructure) are more suitable for funding through grants rather than loans. It also notes DFID’s strengths in supporting policy and institutional development, in research and in developing innovative approaches to infrastructure finance to attract private investors.

Box 4: Infrastructure development in UK overseas territories

DFID has responsibility within the UK government for infrastructure development in the three ODA-eligible UK overseas territories – St Helena (including Tristan da Cunha), Montserrat and the Pitcairn Islands – working where appropriate with the Foreign Office. Under a 2012 white paper, the UK government is committed to supporting economic development and trade, including by supporting investments that will reduce aid dependency. Montserrat has received approximately £400 million in DFID support since its volcanic eruption in 1995. The most substantial investment in recent years has been the £285 million St Helena airport. As this was the subject of a National Audit Office report, it is not covered in our review.

Urban infrastructure is an area where DFID would like to develop its capacity. DFID has been investing in urban infrastructure in India for many years, but its programming in other countries is more recent. DFID has developed a number of centrally managed programmes that support country offices in developing urban infrastructure programmes.

Figure 3: DFID bilateral spending on transport and urban infrastructure programmes active in 2015 or 2016

Figure 4: Country profiles and DFID activities in Uganda and Pakistan

Findings

This section sets out the findings from our review. It begins by assessing the relevance of DFID’s approach to transport and urban infrastructure development. It then explores the performance of DFID programmes, focusing first on those that aim to deliver development results directly in partner countries, and then on programmes with objectives around leveraging and influencing other infrastructure finance.

Relevance: Does DFID have a coherent approach to promoting economic development and poverty reduction through transport and urban infrastructure development?

DFID’s transport and urban infrastructure work supports a number of its strategic objectives

We find that DFID’s transport and urban infrastructure portfolio aligns clearly, though to differing degrees, with three of the four strategic objectives in the UK aid strategy. It aligns most clearly with the objectives of promoting global prosperity and strengthening resilience and response to crisis (see Box 5). A focus on poverty reduction is also visible in some programmes and in the portfolio’s geographic focus on poorer countries and regions. However, for reasons discussed below, we find the links to extreme poverty and vulnerability are not as well developed.

Box 5: Alignment of programmes in our sample with the objectives in the UK aid strategy

Objective: Promoting global prosperity

The portfolio includes investments in strategic transport infrastructure projects, regional infrastructure, building national capacity and mobilising infrastructure finance. Examples from our sample include:

- Strengthening Regional Economic Integration (£58 million; 2013-18) funded improvements at the port of Mombasa, Kenya, as well as regional trade agreements to boost regional trade in East Africa.

- The Pakistan Economic Corridors Programme (£265 million; 2015-20) is a partnership with the Asian Development Bank to upgrade Pakistan’s national highway infrastructure, including its trade links with China and the region.

- The CrossRoads programme (£21 million; 2009-18) in Uganda focused on improving the national road network and the efficacy of national spending on roads, in order to boost trade and growth.

- The Private Infrastructure Development Group (Phase 2: £773 million; 2012-19)29 operates a series of facilities to help mobilise private investment for infrastructure, particularly in fragile contexts.

- The Regional Infrastructure Programme for Africa (£79 million; 2012-16) was designed to overcome constraints on regional infrastructure development and mobilise multilateral infrastructure finance.

Objective: Strengthening resilience and response to crisis

The portfolio includes reconstruction in conflict-affected areas and investments designed to increase resilience to climate change. Examples from our sample include:

- Vital Transport and Education Infrastructure in Border Areas (£22 million; 2010-17) rebuilt bridges and schools in a conflict-affected area of Pakistan close to the Afghanistan border.

- The Afghanistan Infrastructure Trust Fund (Phase 2; £15.5 million; 2014-18) was support provided to a multi-donor fund that supports large-scale infrastructure projects in transport, energy and water resources.

- Building Urban Resilience to Climate Change in Tanzania (£29.6 million; 2015-20) is working to support national and local governments in Tanzania to assess and manage climate-related risks in urban areas.

Objective: Tackling extreme poverty and helping the world’s most vulnerable

The portfolio includes community-based infrastructure projects for remote communities and promoting global road safety standards. Examples from our sample include:

- The Rural Access Programme (Phase 3; £72.5 million; 2013-21) is improving road access for isolated rural communities in western Nepal.

- Research for Community Access Partnership (£28.5 million; 2014-20) explores cost-effective ways of improving transport connections for remote rural communities.

- The Global Road Safety Facility (£9.8 million; 2013-21) is a research programme addressing the growing incidence of road traffic accidents, which disproportionally affect the poor in developing countries.

DFID’s transport and urban infrastructure investments do not constitute an integrated portfolio with a common set of objectives. Rather, DFID invests for a variety of purposes in different contexts. We nonetheless found the strategic rationale for each of the programmes in our sample to be clear and convincing.

The proposed new focus on urban infrastructure also meets a clear strategic need. The continuing rapid pace of urbanisation and the expected impacts of climate change will make this an increasingly urgent challenge that is not receiving the level of aid investment that it needs. Building its expertise in this area offers DFID an opportunity to advance goals around economic transformation, poverty reduction and climate resilience. DFID’s Sustainable Cities for Growth Policy Framework from 2015 sets out the strategic case, noting that cities are engines of economic growth, accounting for half of all economic activity. It includes a focus on rural-urban links, given that urban growth can help to raise rural incomes through increased demand for agricultural produce. It also includes a focus on smaller cities and towns, where there is more scope to develop infrastructure sustainably than in overcrowded capitals.

DFID’s infrastructure investments are selected and designed to contribute to economic growth

In recent years, DFID has scaled up its investment in economic development. Infrastructure is clearly identified in DFID’s 2017 Economic Development Strategy as a potentially transformative investment. Within our sample, we found that programmes have clear strategies for promoting growth, with designs that are well suited to each country context.

For example, the Pakistan Economic Corridors Programme is the largest capital investment in our sample, working in partnership with the Asian Development Bank. The programme is financing transport corridor construction costs of £210 million for the rehabilitation of two national highways and construction of two new motorways identified as important for growth. The roads are intended to promote trade and economic integration within Pakistan by linking the poorest regions in the west (including conflict-affected Balochistan on the border with Afghanistan) with the wealthier provinces of Sindh and Punjab, to the south and east respectively. They also contribute to regional economic integration, helping to give Afghanistan and other landlocked Central Asian states access to Pakistan’s ports at Gwadar and Karachi. Alongside road construction, the programme includes a £40 million component to promote private investment in regional transport projects and a £12 million technical assistance facility that supports the development of national transport policy, including a new road safety action plan to try to bring down the country’s 30,000 annual road accident fatalities. By partnering with the Asian Development Bank and combining grant funding with technical assistance, DFID was able to influence the design of a much larger project, with a total value of over £780 million, including by increasing its focus on deprived areas.

The CrossRoads programme in Uganda was also focused on economic growth, but took an alternative approach in a very different national context. Uganda is a landlocked country that has identified transport connections as critical to its development. When the programme was designed, the Ugandan government had committed an unusually high 19% of its budget (around £415 million) to road development. DFID identified that the Ugandan government was paying too much for road construction, while corruption and vested interests were leading to wasteful projects. CrossRoads was therefore designed to address market and governance failures in the construction and finance sectors, spanning both government and the private sector. For example, it included the development of a construction guarantee fund to encourage Ugandan banks to lend to local road contractors, enabling them to bid for government contracts. This was an innovative approach to a complex problem.

The portfolio also has a strong focus on regional economic integration, which is an important aspect of promoting inclusive growth. TradeMark East Africa (supported by two programmes in our sample, in Uganda and Kenya) is a large and complex programme operating across seven countries. It invests in border posts and streamlined customs processes, to facilitate cross-border trade, as well as in regional trade infrastructure, such as upgrading the port at Mombasa, Kenya. The programme supports the goal of East African countries to establish a single market economic space, with free movement of goods and services within the region. By expanding regional trade and economic integration, they hope to encourage producers to become more efficient and ultimately be able to compete with exporters and in global markets.

DFID’s support for works at the Mombasa port was based on the assumption (or ‘theory of change’) that a reduction in the time required to import or export goods through the port would increase trade volumes (this was the conventional wisdom, as speed of processing is important for trade in goods with limited shelf lives). However, monitoring and evaluation revealed that trade volumes through the port did not increase as a result of faster processing times. The follow-up phase now focuses on bringing down the costs of trading through the port. We find it positive that the programme has been able to test key assumptions underlying its design and adjust in response to lessons learned.

Overall, for the programmes in our sample with an economic development focus, we found that the rationale for the investment was clear and that the programmes were well designed to achieve their objectives.

While some of DFID’s transport and urban infrastructure work has a pro-poor focus, its larger economic growth-focused programmes lack a systematic approach to including the poorest and most vulnerable groups

DFID’s infrastructure strategy acknowledges that, although the link between improved infrastructure and long-term poverty reduction is widely recognised, the mechanisms through which it occurs are context-specific and not well understood. Some investments (such as rural roads) directly target the poorest, while others (such as major highways) contribute to poverty reduction indirectly, by addressing constraints on inclusive growth. The strategy states that, in either case, DFID should try to maximise the benefits for the poor by early consultation with communities and by setting out a clear theory of change linking the proposed investment to poverty reduction. For projects that are primarily growth-focused, the strategy also encourages DFID staff to consider whether ‘additional measures’ to enhance poverty reduction and gender impacts could be introduced without compromising the primary objective.

The link between improved economic infrastructure and long-term opportunities for poverty reduction through inclusive growth is widely recognised… but the precise mechanisms through which this occurs are not well understood.

Sustainable infrastructure for shared prosperity and poverty reduction: A policy framework, DFID, January 2015, p. 27

In practice, we find that the portfolio rates well for its geographic focus on deprived areas. At the international level, through its influencing work with the multilateral development banks and through programmes such as the Private Infrastructure Development Group (PIDG), DFID has made a concerted effort to direct resources towards low-income countries and fragile states, where the infrastructure gaps are widest. Its regional and national investments in transport infrastructure are directed so as to reduce regional economic disparities, while programmes in Pakistan, Nepal and other countries have a strong focus on the most deprived areas. In its new urbanisation work in Kenya, we found that DFID was thinking through how to improve transport links between towns and rural areas to promote a virtuous circle of urban growth and rural poverty reduction.

Within our sample, there are also a number of investment projects that target the poorest and most marginalised groups. The strongest example is the Rural Access Programme in Nepal, which targets deprived districts in western Nepal. These isolated areas were also a base for the insurgency in Nepal’s decade-long civil war, which ended in 2006. The programme aims to provide communities with greater access to public services and economic opportunities, helping to integrate them into Nepal’s economy and society. It provides additional income by employing individuals from poor households for road construction and maintenance, including women, Dalits (members of the lowest caste) and ethnic minorities. The programme also invests in other economic infrastructure, including pedestrian bridges for mountain trails, local markets and irrigation systems, and supports local communities in developing small enterprises. We find this to be a strong example of integrating transport infrastructure into area-based development, with a strong pro-poor focus.

DFID’s research programmes (discussed in the next section) also have a strong focus on issues that matter for the poor. For example, the Research for Community Access Partnership explores costeffective ways of reducing the isolation of remote communities. It has conducted research into how vulnerable groups, including women, children, the elderly and people with disabilities and illnesses, use transport and what solutions are available to improve their access.

For the programmes in our sample that were focused on promoting growth, we found few examples of additional activities or design features to enhance poverty reduction or inclusion. For example, while PIDG spends a significant share of its resources in low-income countries and fragile states, we did not see any evidence that its investment projects were otherwise being selected or designed so as to be pro-poor. It uses a formula to estimate the distribution of benefits in gender terms, which is not the same as designing interventions to enhance inclusivity and gender equality. The Kalangala project in Uganda (see Box 6) illustrates the dilemmas involved in balancing financial returns and poverty reduction impact in low-income contexts. The latest DFID logframe for PIDG includes references to gender and poverty. However, there are no specific additional measures highlighted in the programme’s design around the selection or design of PIDG interventions to target women or the poor, so it is unclear how the programme will increase its focus on these groups. PIDG is now working with Infrastructure and Cities for Economic Development (ICED) to develop a ‘Gender Ambition Framework’ to provide guidance for PIDG facilities on how to improve gender and inclusion outcomes, although earlier guidance on achieving gender impact does not appear to have been translated into design measures or targets in the current logframe.

Box 6: Kalangala – Investing in rural communities on Lake Victoria

One project supported by the Private Sector Development Group (PIDG) invested in infrastructure in the town of Kalangala, on a Ugandan island in Lake Victoria. According to PIDG, it is the first time that commercial funding had been attracted into a greenfield, multi-sector infrastructure project in sub-Saharan Africa where the beneficiaries were poor rural communities. DFID offers it as an example of a poverty-focused investment project.

According to the company managing the investment, the outputs have included two new ferries with 5,200 crossings per year, the upgrading of a 67km dirt road, 2,600 electricity connections and more regular power supply and 645 water connections. The reported benefits have included increased local incomes, improved school pass rates, a reduction in waterborne diseases and the attraction of more skilled labour to the island, including health workers. These are important development benefits for the relatively isolated and poor local community. However, there has not yet been an independent impact assessment of the programme to confirm these results, though we were told that one is planned.

The Kalangala project benefited from support from PIDG’s Viability Gap Funding window, which is supposed to fund the gap between the revenues needed to make projects commercially viable and the user fees that poor customers are able to pay. Despite this, we were told by key stakeholders that the electricity tariff ($0.18/KwH) remains unreachable for poor households and that consumption of electricity therefore remains low. Furthermore, some of the intended beneficiaries have chosen to sell their land (including to hoteliers) and move to more remote islands without infrastructure connections. While these families will have gained financially from increased land values, the experience shows the difficulties involved in using private investment to provide infrastructure to poor communities.

According to DFID guidance, an ‘economic corridor’ approach combines investment in transport infrastructure with other initiatives to promote the social and economic development of communities along the route. The Pakistan Economic Corridor Programme is constructing community facilitation centres in order to better integrate rural market hubs with national markets, while also improving access to social facilities. This is being done in consultation with local communities as well as provincial authorities to increase the local economic impact of the roads currently being constructed with finance from the programme. The Asian Development Bank is also supporting federal and provincial governments with their plans to support the wider economic benefits of transport corridors.

We saw few examples in our sampled growth-focused programmes of activities or design features that specifically targeted women or marginalised groups in their original design. For example, TradeMark East Africa was criticised in an evaluation for failing to have a gender strategy or gender-specific objectives to guide its work on border crossings. In particular, it was not doing enough to support female small traders, who are vulnerable to abuse and harassment when trading across borders. Since then, DFID has worked with the programme to improve its focus on gender issues. It has produced a gender mainstreaming strategy and included more gender-specific activities, such as the design of border posts to meet the needs of women and children, gender awareness training for border post staff and outreach and training programmes for female traders and farmers.

Disability is not yet well integrated into DFID’s transport infrastructure programmes. DFID records on its management information system whether programmes are primarily about disability (‘principal’), include a significant element on disability (‘significant’) or are not active on the issue (‘not targeted’).

Across the 13 programmes in our sample, none has disability as the principal activity, and only four are rated as having a significant focus on disability (see Table 2). These include:

- the rebuilding of school facilities in conflict-affected areas of Pakistan to include access for disabled students

- various research items on disability issues in transport

- the Infrastructure and Cities for Economic Development programme’s technical support facility’s guidance note on disability inclusion in infrastructure and cities investments.

Table 2: Integration of disability into our programme sample Programme Disability

| Programme | Disability marker | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Significant | Not-targeted | Completed before marking exercise | |

| Afghanistan Infrastructure Trust Fund | X | ||

| Creating Sustainable Opportunities for Spending on Roads | X | ||

| Global Road Safety Facility | X | ||

| Infrastructure and Cities for Economic Development | X | ||

| Pakistan Economic Corridors Programme | X | ||

| Private Infrastructure Development Group | X | ||

| Rural Access Programme Phase 3 | X | ||

| Research for Community Access Partnership | X | ||

| Regional Infrastructure Programme for Africa | X | ||

| TradeMark East Africa – Kenya | X | ||

| Building Urban Resilience to Climate Change in Tanzania | X | ||

| TradeMark East Africa – Uganda | X | ||

| Infrastructure in Border Areas | X | ||

Currently, [disability inclusion] is not consistently addressed across DFID’s infrastructure programming and policy dialogue. It is not always clear to DFID staff or partners what [disability inclusion] means in relation to infrastructure and growth, and the actions they might take to achieve it. This is coupled with a perception that addressing disability in infrastructure programming is prohibitively expensive and often unaffordable within project or programme budgets.

ICED Briefing: Disability inclusion through infrastructure and cities investments, ICED programme, March 2018, p. 2

Overall, we found that the programmes in our sample were pro-poor in their geographic focus or where they were specifically designed to target poor communities. However, the portfolio does not follow a systematic approach to inclusion in accordance with the commitment in the infrastructure strategy. This is consistent with the findings of our review of DFID’s work on inclusive growth in Africa, which recommended a more explicit approach to inclusion in programme design and results frameworks and more monitoring of how programme benefits are distributed across different groups.

DFID has identified its comparative advantage alongside other actors but its strategy needs further articulation

The infrastructure strategy identifies six areas of comparative advantage for DFID:

- flexible, politically astute technical assistance

- mobilising private finance

- community-focused infrastructure

- regional integration

- influencing key international actors

- building the evidence base.

These reflect several strengths of DFID’s infrastructure work, including its experience with policy influence and institutional development, its relatively high appetite for working on complex and politically sensitive issues with a significant risk of failure, its close relationships with the multilateral banks (especially the World Bank) and its strong research portfolio. Small-scale community infrastructure and border infrastructure are two areas that partner countries may be unwilling or unable to finance through loans and which pose complex institutional challenges.

We find that DFID’s portfolio corresponds broadly to these six areas and that DFID does indeed have a useful contribution to make in each, alongside other development partners. Many of its programmes are designed to be catalytic, by addressing market or governance failures that limit infrastructure development and by helping partner countries access and make better use of other sources of infrastructure finance. However, we came across one example of a significant DFID investment in infrastructure construction that was difficult to reconcile with its comparative advantage (see Box 7).

Box 7: The case for mixing DFID grant funds with an Asian Development Bank loan in Pakistan

The Pakistan Economic Corridors Programme includes a £210 million DFID grant contribution for building highways, alongside a £362 million Asian Development Bank loan. This is accompanied by additional DFID funding for public-private partnerships and technical assistance. The DFID contribution placed DFID in a position to influence the design of the Bank’s project in useful ways – including by increasing the proportion of funds going to the economically deprived province of Balochistan. However, the investment is difficult to reconcile with DFID’s stated areas of comparative advantage on infrastructure, which does not include filling funding gaps for major infrastructure development. It is also unclear that funding on such a large scale from DFID was needed to influence programme design. While this does not mean that the programme will be unsuccessful, it does suggest that DFID does not always concentrate on its areas of comparative advantage.

Urban infrastructure is identified in the infrastructure strategy as an area where DFID would like to develop a comparative advantage. Urban projects can be particularly complex, owing to the number of stakeholders involved, including different levels of government (national, regional and municipal) and functional agencies (such as urban planners, utility companies, and environmental protection agencies). As noted by a DFID review of a large urban programme outside our sample, delivering quality urban infrastructure requires engagement with multiple counterparts and entry points through the infrastructure financing and delivery cycle, strong technical resources, sufficient time to consult properly with urban communities and a willingness to learn and adapt.

DFID is using centrally managed programmes to bring in additional technical support on urban infrastructure. The Infrastructure and Cities for Economic Development programme includes a facility to advise country offices on developing their urban portfolios (see Box 8). While this is potentially a good strategy for giving country offices more access to technical expertise, it still leaves them short of experienced staff to manage complex programmes and build relationships and engage in policy dialogue with multiple national counterparts.

Box 8: The Infrastructure and Cities for Economic Development (ICED) Facility

The ICED Facility is a £10.1 million component of the £33.5 million Infrastructure and Cities for Economic Development programme (2015-20). So far, it has provided technical support on request, supporting the development of seven business cases and preparing around 38 scoping studies. The DFID ICED team identified a risk that individual requests might not support the overarching strategic direction of team/country priorities, and proposed a “strategic pivot”. This included a new engagement strategy focusing on priority countries and central teams, as well as identifying wider opportunities for investing in economic development and prosperity.

While DFID’s comparative advantage is clearly identified, we find the infrastructure strategy has gaps in other areas. It does not consider the role of bilateral programmes alongside a scaled-up CDC or the expanding aid portfolios of other UK departments and funds, including the Prosperity Fund and the Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy, which invests in low-carbon development. It notes that China is now the largest external provider of concessional infrastructure finance, but does not work through the implications for partner countries – such as on infrastructure quality standards, environmental impact and debt sustainability. It would also be appropriate for the strategy to include a more systematic treatment of the policies and institutions that partner countries need for sustainable infrastructure development.

We would also expect to see DFID’s infrastructure work in particular countries underpinned by stronger analysis. The infrastructure strategy stated that the 2015 inclusive growth diagnostic exercise would identify priority areas for supporting economic transformation. While most participating country offices identified infrastructure deficits as a constraint on inclusive growth, there was not much depth of analysis on the extent, nature or causes of the gaps (see Box 9).

Box 9: Infrastructure in DFID’s Inclusive Growth Diagnostics

At the country level, DFID’s Inclusive Growth Diagnostics set out a rationale for its infrastructure investments, although in very general terms. For example, in Uganda the diagnostic identified poor infrastructure, especially transport, as a constraint on growth and poverty reduction and noted risks around rapid, unplanned urbanisation. DFID Uganda is drawing on a centrally managed programme, Cities and Infrastructure for Growth, to identify solutions to the infrastructure needs of Greater Kampala.

In Pakistan, the diagnostic also noted high rates of unplanned urban development and identified urban governance as a gap in DFID’s knowledge. It described “limited regional connectivity” as a constraint on regional trade and growth and noted a problem with unequal distribution of infrastructure. DFID’s transport infrastructure investments in Pakistan include a major investment in regional trade links and a programme to extend transport infrastructure to economically deprived areas. The road links it supports fit into a national road planning framework developed with Asian Development Bank support.

However, beyond identifying infrastructure deficits as a constraint on growth, there is little depth of analysis in the main diagnostic reports, which contain no data on or detailed description of infrastructure gaps. There is also no analysis of the governance and market failures that give rise to those gaps, as recommended in the 2015 infrastructure strategy – although the diagnostics are high-level summary documents covering all key DFID sectors. DFID plans to conduct a new round of country diagnostic work in 2018-19.

Conclusions on relevance

Overall, we find that DFID has clear goals for its transport and urban infrastructure projects that are well aligned to its objectives on economic growth, post-conflict recovery and resilience to climate change. The programmes in our sample had been selected to address constraints on growth, including by linking deprived areas and communities to economic opportunities and addressing the governance and market failures that hold back infrastructure development.

We find that the infrastructure portfolio is pro-poor in its geographic focus on economically deprived and conflict-affected areas. DFID also has a number of transport and urban infrastructure programmes that target marginalised groups, both through direct investments and through research and advocacy. However, its growth-focused programmes were not designed with features to enhance the benefits for the poor, and lacked a systematic approach to including women, people with disabilities and marginalised groups.

DFID shows a good understanding of its comparative advantage alongside other development partners and most of its programmes are designed to achieve catalytic effects. However, its strategy could be better articulated, given a rapidly changing global context for infrastructure finance, and its programming could be based on a stronger analysis of infrastructure gaps in each country.

On balance, we find that the approach merits a green-amber score for relevance, but that it will need to continue evolving in the coming period.

Effectiveness: How effective are DFID’s bilateral transport and urban infrastructure programmes?

In this section, we explore the effectiveness of programmes that invest directly in transport and urban infrastructure or in building the capacity of country partners to develop infrastructure. The next section assesses the effectiveness of DFID’s programmes that work by influencing the multilateral development banks or the sector as a whole. We take DFID’s own programme scores and assessments as our starting point, triangulated as much as possible through key stakeholder interviews and reviews of other documents.

Programme performance has been mixed, with some strong results offset by frequent delays

Our analysis of the effectiveness of DFID’s programmes suggests considerable variation in performance. Most eventually delivered their planned investments or activities (‘outputs’), but with frequent implementation challenges along the way (see Table 3). There is considerable variation as to whether programmes achieved their desired results (‘outcomes’), with shortfalls due to some poorly formulated results targets as well as delivery problems.

The Rural Access Programme in Nepal has performed well at both output and outcome level, achieving all of its current targets. It has constructed 97.5km of new roads and maintained 2,200km, improving all-weather access for 2.1 million people. The strong emphasis on road maintenance contributes to sustainability and value for money. A mid-term review found that roads maintained by the programme were used more regularly by local communities, with evidence of increased usage of health posts along the route. The programme uses workers from poor communities as maintenance crews, creating employment for 8,100 people. Another mid-term review found that participating households spent more money on their children’s education and health, had better access to credit and spent more on acquiring productive assets, such as tools and livestock. While most of the programme has performed well, planned financial assistance to a regional government to support roadworks has not been disbursed owing to fiduciary risks connected to that government’s restructuring.

Table 3: Programme output scores by year

| Programme | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Afghanistan Infrastructure Trust Fund | A | A | A | B | B | ||

| Creating Sustainable Opportunities for Spending on Roads | B | B | A | A | |||

| Global Road Safety Facility | A | A | B | A | A+ | ||

| Infrastructure and Cities for Economic Development | A | A | A | ||||

| Pakistan Economic Corridors Programme | A | A | A | A | |||

| Private Infrastructure Development Group | A | B | A | A | A | ||

| Rural Access Programme Phase 3 | B | A | A | A | |||

| Research for Community Access Partnership | A | C | A | A | |||

| Regional Infrastructure Programme for Africa | A | A | A | B | A | ||

| TradeMark East Africa – Kenya | A | A | A | A | A | ||

| Building Urban Resilience to Climate Change in Tanzania | C | A | |||||

| TradeMark East Africa – Uganda | A | A | A+ | A+ | A+ | A+ | |

| Infrastructure in Border Areas | A | A | A | A | A | B |

Source: DFID programme annual reports and project completion reviews.

Notes: DFID uses a scoring system from ‘C’ (“outputs substantially did not meet expectation”) to ‘A++’ (“outputs substantially exceeded expectation”). A score of ‘A’ or above means that output targets were achieved. Reviewing and Scoring Projects, DFID Smart Guide, June 2014, unpublished.

This road is very important and profitable to small eateries and hotels located along the roadside. In the past before this road was constructed, we had to walk to Mangalsen to purchase household goods which was a two hour walk. We could only carry limited quantity of goods but now it has become very easy for us to bring household goods from Mangalsen to our village.

Beneficiary quoted in feedback report for the Rural Access Programme in Nepal, June 2017, p. 35

Other programmes have also encountered difficulties in working with national counterparts. The Vital Transport and Education Infrastructure programme has reconstructed 66 bridges and 40 schools in conflict-affected areas of Pakistan, achieving almost all its output targets. This was an emergency initiative designed at speed and some of its initial assumptions proved unrealistic, including around the capacity of local authorities to participate. Delivery was also affected by adverse weather, including a major flood. These factors led to a redesign a year into the programme. At the time of our visit, outstanding work, such as installing access ramps, was needed from the provincial government at four bridge sites. Nonetheless, 65 of the 66 bridges were functional and open for traffic, providing daily passage to 67,000 pedestrians (42% of whom were children) and 36,000 vehicles, and surveys of local communities have found a good level of satisfaction with the works and the process.