Sexual exploitation and abuse by international peacekeepers

Executive summary

This short report is a companion to ICAI’s January 2020 review of the UK’s Preventing Sexual Violence in Conflict Initiative (PSVI). It explores the UK’s efforts to tackle sexual exploitation and abuse (SEA) in international peacekeeping settings, including by soldiers, police and civilian personnel. SEA in peacekeeping is a form of conflict-related sexual violence, but it is treated as a separate issue by both the UN and the UK government. At the request of government, it was therefore decided to release the findings on this aspect of the review as a separate report. ICAI is also planning a wider review of safeguarding against sexual exploitation, abuse and harassment in the aid sector – beyond international peacekeeping contexts – in 2021.

During the period covered by this review (2014-19), the UK’s efforts to tackle SEA in international peacekeeping were supported by small-scale aid projects managed by the former Foreign and Commonwealth Office (FCO), mainly in the form of funding for UN reform initiatives and staff positions, and training programmes for international peacekeepers run by the Ministry of Defence (MOD). In view of the relatively limited scale of these investments and the difficulty of measuring the results of activities of this kind, the review is not scored.

SEA in peacekeeping is a serious and persistent problem, with devastating impact on survivors. Allegations of SEA have surfaced in many international peacekeeping missions around the world, including in Bosnia and Herzegovina, Cambodia, the Central African Republic, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Haiti, Kosovo, Mali, South Sudan, Sudan and Timor-Leste. In recent years, the UN has launched a number of reforms designed to prevent SEA, hold perpetrators accountable and protect survivors. However, UN internal reports have found serious shortcomings in the conduct of investigations, while continuing legal obstacles to prosecution contribute to a culture of impunity within international peacekeeping contingents.

Findings

The UK has been a leading voice in tackling SEA in international peacekeeping, both in the UN Security Council and through the UK aid programme. The UK government has worked with the UN secretary-general to change the mandates of peacekeeping missions and promote a voluntary compact on SEA, which has been signed by 103 countries. UK aid has supported training and awareness raising within the UN and funded the UN Office of the Victims’ Rights Advocate.

During the review period, the FCO’s efforts to support the UN in tackling SEA in peacekeeping missions focused primarily on improving the conduct of international peacekeeping personnel by strengthening policies and disciplinary processes, both in the UN and in troop-contributing countries. The FCO supported the establishment of Conduct and Discipline Teams within peacekeeping missions. An initiative funded through the Conflict, Stability and Security Fund has contributed to the introduction of a UN-wide ‘Clear Check’ system for tracking SEA allegations against UN staff. As a result, those dismissed for SEA violations are no longer able to take up new jobs within the UN system.

The MOD’s British Peace Support Team (BPST) in Nairobi trains over 10,000 African peacekeepers each year. The course includes modules on SEA and conflict-related sexual violence more broadly, and encourages participants to carry out awareness-raising initiatives within their units. Through UK efforts, all peacekeeping troops are now issued with ‘No Excuse’ cards setting out the standards expected of them. The FCO and the MOD have helped extend some of these measures to peacekeeping missions managed by the African Union and NATO.

Support for survivors has not been a strong feature of the UK government’s support to the UN’s work on SEA in international peacekeeping missions. The UK has chosen not to contribute to a Victims’ Assistance Fund established by the UN. We found one example of a UK aid project with UN peacekeepers working directly with SEA survivors and their communities. Operating in four countries, it has established reporting networks and hotlines, supported by outreach and awareness raising through social media.

We find these to be relevant and important initiatives. However, given limited progress so far in tackling SEA in peacekeeping contexts through disciplinary processes, we find that the approach has an insufficient focus on programming targeting the needs of survivors.

There is limited evidence available so far on how effective the UK’s support for tackling SEA in peacekeeping has been. UK aid has helped to raise awareness of the SEA challenge and to articulate the standards expected of international peacekeepers. There is evidence that training initiatives are raising awareness of SEA among international peacekeepers. However, the BPST is finding it challenging to assess whether this raised awareness leads to changes in behaviour once troops are deployed.

The UK has been a central driver of UN reforms to put in place SEA reporting and investigation mechanisms. However, there remain major legal and practical barriers to the effective investigation and prosecution of violations. Peacekeepers are immune from prosecution by the country where they are stationed. In the case of civilian staff, the UN can choose to waive this immunity, but does so only if it judges that a fair trial is possible. This is rarely the case in conflict zones. In the case of international peacekeeping troops, the troop-contributing country retains jurisdiction. Prosecutions remain infrequent, due to the difficulties of collecting and transferring evidence and the fact that the legal standards governing SEA vary across countries.

Given the climate of impunity, achieving changes in behaviour in peacekeeping missions is likely to be a long-term endeavour. Drawing on efforts to tackle conflict-related sexual violence more broadly, the focus needs to be on protecting vulnerable communities and individuals and on redress and support to survivors. With the merger of the FCO and the Department for International Development into a new Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office, there is an opportunity for the UK government to integrate better its work on SEA in peacekeeping into its broader aid efforts to tackle conflict-related sexual violence.

Recommendations

Recommendation 1

The UK government should aim for closer integration and sharing of learning between its efforts to tackle SEA in international peacekeeping and its wider work on conflict-related sexual violence.

Recommendation 2

The UK government should ensure that efforts to improve discipline among peacekeeping personnel are balanced with measures to promote the interests and welfare of survivors.

Introduction

“I had to make decisions because life was so difficult, so I chose to enter into these relations for survival.”

Central African Republic: Rape by peacekeepers, Human Rights Watch, February 2016.

“When peacekeepers exploit the vulnerability of the people they have been sent to protect, it is a fundamental betrayal of trust. When the international community fails to care for the victims or to hold the perpetrators to account, that betrayal is compounded.”

Taking action on sexual exploitation and abuse by peacekeepers: Report of an independent review on sexual exploitation and abuse by international peacekeeping forces in the Central African Republic, Deschamps, M. et al., December 2015, p. i.

ICAI published its review of the UK’s Preventing Sexual Violence in Conflict Initiative (PSVI) in January 2020. This report on the UK’s efforts to address sexual exploitation and abuse (SEA) in international peacekeeping settings accompanies that review. Both are about conflict-related sexual violence, a devastating and far too common feature of armed conflicts. However, the UK government addresses SEA in peacekeeping through initiatives that are separate from the PSVI portfolio. At the request of government, it was therefore decided to release the findings on this aspect of the review as an accompanying report. ICAI is also planning a wider review of safeguarding against sexual exploitation, abuse and harassment in the aid sector – beyond international peacekeeping contexts – in its future review programme.

Although the UN has collected data on sexual abuse and violence since 2004, changes to definitions, classifications and methodology make it difficult to get a clear picture of prevalence rates and trends. However, recurrent scandals and investigations over the past three decades make it clear that SEA is a significant and persistent problem for UN peacekeeping missions. Allegations of sex trafficking, rape, exploitation or abuse, often involving minors, have been uncovered more or less everywhere there have been peacekeeping missions, including in Bosnia and Herzegovina, Cambodia, the Central African Republic (CAR), the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), Haiti, Kosovo, Mali, South Sudan, Sudan and Timor-Leste.

Repeated violations – too often followed by a lack of proper investigation and redress – undermine peacekeeping missions by compromising the trust of local populations. In 2005, in the wake of revelations of widespread sexual violence by UN peacekeepers in the DRC, the UN secretary-general undertook a comprehensive review of the issue. In a cover letter to the UN General Assembly, he stated that those revelations “have done great harm to the name of peacekeeping. Such abhorrent acts are a violation of the fundamental duty of care that all United Nations peacekeeping personnel owe to the local population that they are sent to serve”. The review was followed by a drive to put more robust measures in place to address SEA by international members of peacekeeping missions.

While there has been some progress, the UN acknowledges that survivors of SEA continue to face daunting physical, cultural and institutional barriers to obtaining justice, or even basic support for their recovery. The fact that peacekeeping missions are conducted in situations of conflict and humanitarian crisis, characterised by violence, displacement and lawlessness, increases survivors’ vulnerability and hampers their ability to report abuse. Furthermore, while the UN has recognised SEA in peacekeeping as a form of conflict-related sexual violence, not all troop-contributing countries have put in place effective legal mechanisms to address violations.

A culture of impunity continues to hamper efforts to address SEA. In 2015, an independent review of the UN’s response to SEA by peacekeepers in CAR noted serious flaws in how allegations were investigated and survivors treated. It concluded that, despite the various reports and reforms over the past decade, impunity continued to be the norm. Since 2015, there have been a further 129 SEA allegations against international peacekeeping troops and civilian personnel in CAR, of which 58 involved child victims. Thus, while more attention is given to the problem today than it was 20 years ago, the question of how best to tackle SEA by members of international peacekeeping missions remains a pressing one.

The scope of this review

The UK has been a prominent supporter of the UN’s efforts to address SEA in peacekeeping. This review, which covers the period between 2014 and 2019, assesses the relevance and effectiveness of UK aid to tackle SEA in international peacekeeping missions, most of which has gone towards funding UN staff positions and internal reforms.

This review covers SEA by international troops, police and civilian staff in international peacekeeping missions, including those managed by the UN, the African Union and NATO. It includes the UK’s training of international peacekeeping personnel. The review does not include SEA by humanitarian and nongovernmental organisation staff outside peacekeeping missions. We plan a separate review in 2021 on the topic of safeguarding in UK aid more broadly.

We have structured this report according to the three review questions listed in Table 1 below. It is a brief report, intended as a companion piece to the main report on PSVI. The review is not scored, due to the relatively low level of expenditure and the difficulty of attributing specific results to activities of this kind.

Table 1: Our review questions

| Review criteria | Review questions |

|---|---|

| Relevance | Does the UK have a well-considered approach to tackling sexual exploitation and abuse by international peacekeepers? |

| Effectiveness | How well have programmes aimed at tackling sexual exploitation and abuse by international peacekeepers delivered on their objectives? |

| Learning | How have responsible departments sought to learn from, and apply learning to, programming on sexual exploitation and abuse by international peacekeepers? |

Methodology

This review of sexual exploitation and abuse in peacekeeping contexts was conducted jointly with ICAI’s review of the Preventing Sexual Violence in Conflict Initiative, which was published in January 2020. The methodology for both reviews was set out in a single approach paper.

Across the two reviews, we conducted 114 interviews with key stakeholders, including survivors and survivor-led civil society organisations (CSOs), and assessed more than 400 documents covering work by the FCO and the Department for International Development (DFID), which in September 2020 merged to become the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO), as well as the Ministry of Defence (MOD). Five country case studies were conducted – Bosnia and Herzegovina, Myanmar, Colombia, the DRC and Somalia – with visits to Bosnia and Herzegovina and the DRC, in addition to interviews with key stakeholders for peacekeeping in Somalia. For the SEA component, we visited the African Union headquarters in Addis Ababa, the Department of Political and Peacebuilding Affairs at the UN Secretariat in New York and the British Peace Support Team (Africa) in Nairobi.

An important part of our methodology was to include the voice of survivors of conflict-related sexual violence. To ensure that we did so safely and ethically, research protocols were developed to guide our evidence collection, with strict adherence to established principles for working with vulnerable participants.

Box 1: Limitations to our methodology

The small size of this portfolio and the nature of the UK’s spending on SEA in international peacekeeping, which is almost entirely focused on funding UN reform and staff positions, meant that evidence and data on effectiveness and impact were limited. Because of the scarcity of results data, our conclusions draw primarily on interviews with UK government and UN staff and other key stakeholders, as well as the literature review.

Background

SEA is a form of conflict-related sexual violence, but with distinct features and challenges

In the context of international peacekeeping, the term ‘sexual exploitation and abuse’ covers a range of violations, including harassment and abuse of power for sexual purposes, sex trafficking and rape. While UN rules prohibit all forms of SEA, not all instances are criminal under the laws of troop-contributing countries or the countries where peacekeepers are stationed. For instance, the UN definition of SEA includes transactional sex, which in some states is legal or non-criminal.

This review adopts the UN definition of SEA, as follows:

- Sexual exploitation: any actual or attempted abuse of a position of vulnerability, differential power, or trust, for sexual purposes, including, but not limited to, profiting monetarily, socially or politically from the sexual exploitation of another.

- Sexual abuse: the actual or threatened physical intrusion of a sexual nature, whether by force or under unequal or coercive conditions.

It is the official position of the perpetrator – as a military, police or civilian member of an international peacekeeping mission – that distinguishes SEA from other forms of conflict-related sexual violence, rather than the conduct itself.

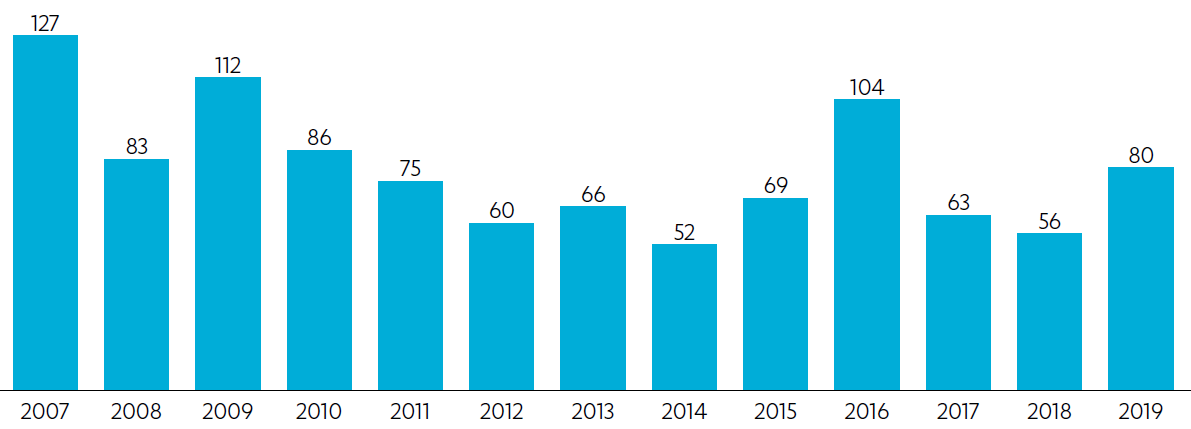

Figure 1: Annual number of SEA allegations reported to the UN between 2007 and 2019

Source: UN Department for Management Strategy, Policy and Compliance.

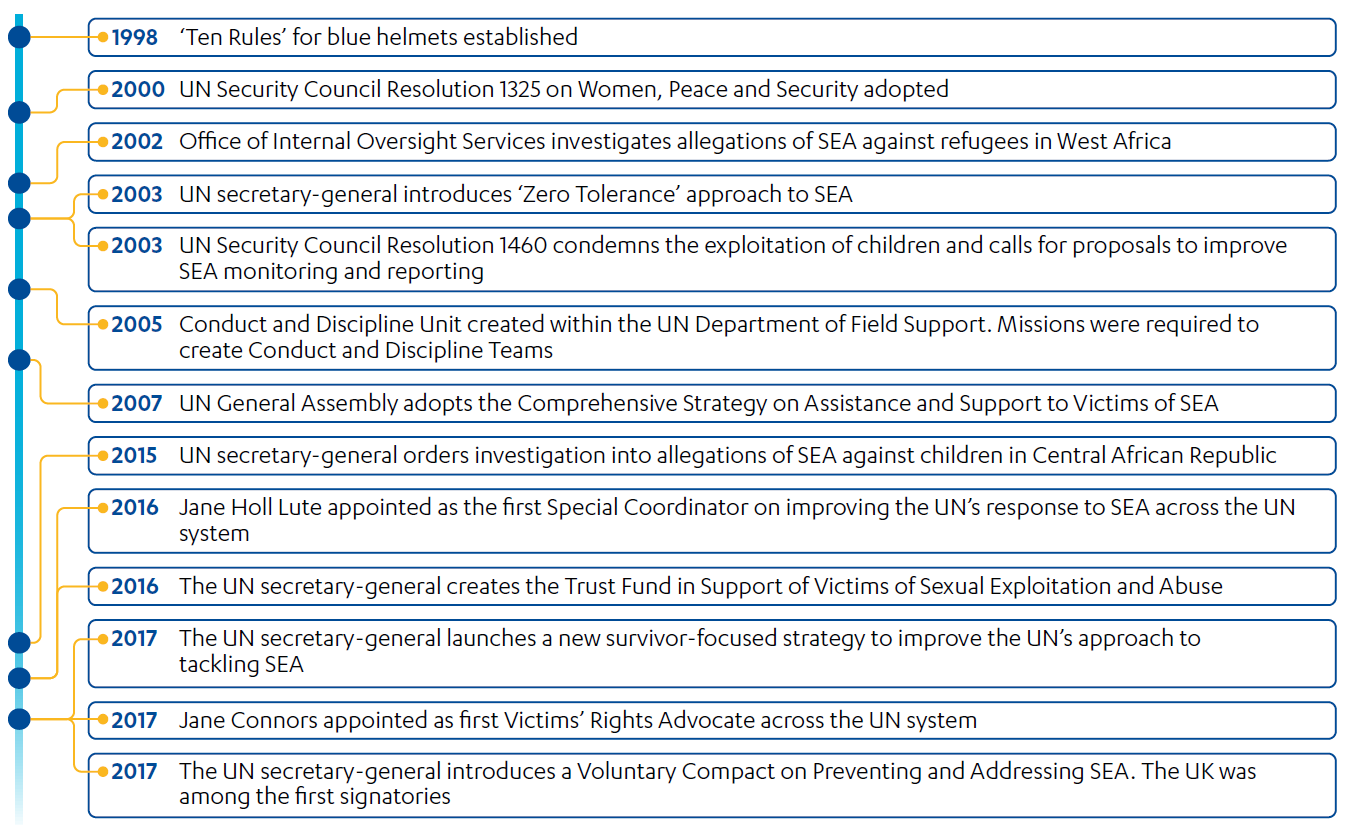

In recent years, the UN has established processes for preventing, reporting and investigating SEA allegations

The UN’s response to SEA has centred mainly on addressing the behaviour of uniformed peacekeeping forces. In 1998, the UN established ‘Ten Rules’, a list of guidelines for the conduct of ‘blue helmets’, or UN peacekeeping troops. In 2003, at the request of the UN Security Council, the secretary-general set out a zero-tolerance approach to SEA, listing types of sexually exploitative or abusive behaviour that are prohibited for UN personnel and are subject to administrative action or disciplinary measures, including dismissal. This was a response to an investigation by the Office of Internal Oversight Services, the UN body tasked with investigating SEA reports, into allegations of sexual violence against refugees in West Africa by UN staff.

In 2005 another UN report, A comprehensive strategy to eliminate future sexual exploitation and abuse in United Nations peacekeeping operations, led to the establishment of a Conduct and Discipline Unit within the UN’s Department of Field Support. Each active UN peacekeeping mission and special political mission must create a Conduct and Discipline Team. These are required to report any allegation of SEA to the central unit. If the alleged perpetrator is a civilian UN staff member, then the Office of Internal Oversight Services leads the investigation. However, under the international agreements governing UN peacekeeping forces, military forces remain under the exclusive jurisdiction of their own governments. Any allegations against soldiers are therefore referred to the troop-contributing country.

In December 2007, the UN General Assembly adopted a ‘comprehensive strategy’ on assistance and support to victims of SEA. Under the strategy, the UN began to pay more attention to the needs of survivors. It took steps to overcome the significant barriers survivors and witnesses encountered in reporting violations, and the lack of support for survivors seeking justice and trying to rebuild their lives.

Figure 2: Timeline for UN efforts to tackle SEA in peacekeeping missions

There are significant legal and institutional barriers to implementing these processes

While processes for receiving, investigating and acting on SEA complaints are now in place, the problem is far from resolved. In 2015, an independent panel established to investigate allegations of SEA against children by peacekeepers in the Central African Republic concluded that:

“The very same problems identified by the previous reports remain unaddressed and unabated: a culture of impunity in which some leaders turn a blind-eye to sexual crimes by troops; a bureaucratic culture in which many are not willing to take responsibility for addressing the violations or to show leadership in investigating and prosecuting the criminal conduct; a disproportionate concern with protecting the image of the UN and its agencies rather than helping the victims; and routine and systematic delay at every stage of decision-making, even as the failure to act means that crimes may be reoccurring and that the chances of bringing the perpetrators to justice decrease day by day. The end result is inaction, which only feeds the perception that there is little risk or consequence for those who choose to exploit the most vulnerable members of society.”

Taking action on sexual exploitation and abuse by peacekeepers: Report of an independent review on sexual exploitation and abuse by international peacekeeping forces in the Central African Republic, Deschamps, M. et al., December 2015, pp. 4-5.

One of the challenges is the legal immunity of members of UN peacekeeping missions. Different rules apply to civilian and military personnel. UN civilian staff in peacekeeping missions are immune from prosecution under the laws of the host country. The UN can waive this immunity if the allegations are unrelated to their official duties (as SEA allegations always would be) but does not do so unless it assesses that a fair and effective prosecution in the mission host country is likely. The UN rarely waives immunity in conflict and post-conflict zones.

It is not common for civilian peacekeeping personnel to be prosecuted in their home country either. Where the offence takes place in a conflict zone, there are substantial difficulties with collecting, processing, storing and transmitting evidence to the standards required by the justice system in the offender’s country of origin. Furthermore, national legal systems have varying standards with respect to the criminality of sexual violence, the legality of transactional sex and the age of consent.

In the case of allegations against military peacekeepers, the troop-contributing country has the right to assert its jurisdiction and commence an investigation. Should it fail to do so within ten days, the UN has the authority to step in and investigate. In practice, however, allegations that are not investigated by the troop-contributing country rarely end up being investigated.

The UK’s response: supporting UN efforts to improve how it addresses SEA in international peacekeeping

During our review period from 2014 to 2019, the UK focused its efforts to tackle SEA in international peacekeeping missions in two areas. Most of the aid spending went towards supporting reform within the UN, led by the FCO. This included funding for UN staff posts and specific reform initiatives, including strengthening leadership on SEA, investigation capacity and the promotion of survivors’ rights (see Table 2). The UK also works to build the capacity of troop-contributing countries to combat SEA through training and mentorship provided by the British Peace Support Team (BPST). The BPST’s training is delivered by the Ministry of Defence (MOD) and funded by the Conflict, Stability and Security Fund (CSSF) Africa Peace and Security programme.

Within the FCO (and now the FCDO), the Gender Equality Unit leads on tackling SEA in international peacekeeping, with a staff member dedicated to the issue, working in partnership with the Preventing Sexual Violence in Conflict Initiative (PSVI) team and the UN Peacekeeping Joint Unit. UK programming on SEA in international peacekeeping is managed from the FCDO in London and at the UK mission to the UN in New York, with the CSSF as the main funder. Coordination takes place through a UK government UN Peacekeeping Joint Unit, whose remit covers all aspects of peacekeeping. From 2014 to 2019, the UK dedicated £3.8 million to SEA, much of which was through the CSSF’s ‘Championing Our Values’ programme, managed by the UK Mission to the UN.

The MOD leads on programmes to train peacekeeping troops, including through the BPST (Africa), which it supplements with informal mentorship at the highest ranks of partner militaries. All SEA-related activity delivered by the BPST (Africa) is funded by the CSSF. The total reported CSSF funding for the BPST was £1.4 million. We do not have disaggregated figures for the amount spent by the MOD on SEA-related activities, but the department, as noted in our PSVI review, includes issues of conflict-related sexual violence and human security, including SEA, in its training modules for international peacekeepers.

During the review period, DFID’s Safeguarding Unit focused on tackling SEA and sexual harassment across the aid sector, but not with a specific focus on SEA in international peacekeeping missions. Programming on violence against women and girls and gender inequality was led by other parts of DFID. While some of this work was relevant, DFID did not provide a breakdown of its programming which would enable identification of interventions focused specifically on SEA in international peacekeeping. The gap in the data makes it difficult to determine the significance afforded to conflict-related sexual violence in general, or SEA in particular, within DFID’s broader programming on gender-based violence and safeguarding in the 2014-19 period.

In 2019 the then international development secretary, Rory Stewart, indicated that DFID planned to spend around £40 million between 2018 and 2023 on tackling SEA and sexual harassment in the aid sector. We were informed by DFID that while much of this sum has been allocated, it has not yet been spent and most of the programming has not yet started. DFID also confirmed that the vast majority of this spending will focus on safeguarding in the aid sector broadly speaking, and will not be specific to SEA in international peacekeeping. The only directly relevant future project is the projected funding of a partnership between the UN Office of Internal Oversight Services and the University of Reading to create a database of SEA allegations to support the UN’s investigations processes.

We will come back to this broader programming in our future review of the UK’s response to the safeguarding crisis in the aid sector. Table 2 below only includes spending we could verify as directly focused on SEA in international peacekeeping.

Table 2: UK aid spent directly on SEA in peacekeeping, 2014-19

| Implementer | FY14-15 | FY15-16 | FY16-17 | FY17-18 | FY18-19 | FY19-20 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UN Special Coordinator SEA – core support | - | - | £200,000 | £200,000 | - | - |

| Victims’ Rights Advocate (role created in August 2017) | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | £158,000 | £200,000 |

| Office of Internal Oversight Services – investigation training | - | - | £140,000 | - | £330,000 | - |

| UN Conduct and Discipline Service – core support | - | - | £515,000 | £500,000 | £415,000 | £500,000 |

| UN Department of Field Service/ Department of Peace Operations – SEA communications | - | - | - | £255,000 | - | £300,000 |

| NATO | - | - | - | - | - | £100,000 |

| Total each year | 0 | 0 | £855,000 | £955,000 | £903,000 | £1,100,000 |

| Total | £3,813,000 |

Findings

Relevance: Does the UK have a well-considered approach to tackling sexual exploitation and abuse by international peacekeepers?

The UK is a leading voice on SEA at the UN and is encouraging other donors to follow

Since 2014, the UK has been a leading voice on sexual exploitation and abuse (SEA), alongside a few key partner governments such as Australia, Canada and the United States. From its position on the UN Security Council, the UK has consistently advocated for reform to address SEA. In 2016, it helped to sponsor UN Security Council Resolution 2272, which made the reporting of SEA allegations mandatory. The resolution called on member states to repatriate peacekeeping units implicated in persistent and widespread sexual offences and reminded them of their responsibility to investigate allegations thoroughly and expeditiously.

The UK has also used its role on the Security Council to ensure that the mandates for new peacekeeping missions contain provisions on protecting women and children from SEA and include measures for ensuring accountability for any violations that occur. The UN Peacekeeping Joint Unit – a taskforce of UK government representatives based in London and New York – lobbies other UN member states to support such measures and to increase their own advocacy on SEA issues.

At the 2017 UN General Assembly, the UK prime minister joined the UN secretary-general’s ‘circle of leadership’ on SEA – a network of global leaders who actively support the agenda. The UK then helped to promote the secretary-general’s Voluntary Compact on Sexual Exploitation and Abuse, which as of 24 September 2019 included 103 member state signatories.

At the Safeguarding Summit hosted by the UK government in London on 18 October 2018, DFID announced that it would provide up to £50,000 to help the Victims’ Rights Advocate, established by the UN in 2017, to develop a statement of victims’ rights. This is due to be published in 2020.

At the same summit, Lord Ahmad, the prime minister’s Special Representative on Preventing Sexual Violence in Conflict, announced that the FCO would dedicate £100,000 in 2018-19 to mapping local capacities to assist and support SEA survivors (both in peacekeeping and in other contexts) in Bangladesh, CAR, Colombia, the DRC, Greece, Haiti, Lebanon and South Sudan. In January 2019, Lord Ahmad announced that an additional £200,000 would be spent in 2019-20 to expand the project to five more countries. The project is led by the UN Office of the Victims’ Rights Advocate and funded through the Conflict, Stability and Security Fund (CSSF).

The UK Mission to the UN has hosted roundtables and training sessions with key stakeholders in New York and Geneva to build their capacity to respond to SEA. In May 2019, the mission hosted a training session on SEA with UN Secretariat staff and leaders of Conduct and Discipline Teams. That same month, the UK hosted the UN Chief Executives Board for Coordination and used the opportunity to raise the importance of responding to SEA.

The FCO supported its advocacy work with targeted investments to improve conduct and discipline in peacekeeping operations

Like the UN itself, the FCO addressed SEA primarily as a conduct and discipline issue. It sought to strengthen policies and disciplinary processes both at UN headquarters and within troop-contributing countries.

During the review period, the FCO supported the UN’s Conduct and Discipline Unit, located at UN headquarters in New York, and Conduct and Discipline Teams within each peacekeeping mission. This included support for salaries, training programmes and the development of ‘No Excuse’ cards setting out the standards expected of peacekeepers and how to report incidents of SEA. These cards are given to international peacekeeping troops to carry at all times.

The FCO-led and mostly CSSF-funded support helped the UN to implement system-wide changes to ensure that offenders cannot simply move to new UN positions. Since 2018, the UN has an interagency misconduct tracking system, Clear Check, which prevents personnel dismissed for substantiated SEA allegations, or who resigned during a pending investigation, from being re-employed within the UN system. The UN has also developed a Victim Assistance Tracking system to gather UN system-wide information on support and assistance provided to victims.

The MOD’s human security training, which includes elements on how to identify, report and prevent SEA, is offered to a selection of troop-contributing countries and representatives from the African Union (AU) and NATO. The FCO also seconded two advisers to develop NATO’s SEA policy, with £100,000 in official development assistance funding from the CSSF.

The UN has recognised the need to support survivors, but this has not featured strongly in the UK’s support to the UN

From 2007 onwards, recognising the challenges survivors and witnesses face when trying to report and seek justice for SEA violations, the UN called on member states to increase their support for survivors. The UK has begun to do so through some one-off grassroots initiatives, but their scope has been limited. We found only two projects dedicated to supporting survivors of SEA in international peacekeeping:

- A small prevention project working with vulnerable communities in CAR and the DRC, later expanded to other locations, focusing on grassroots initiatives such as reporting mechanisms and communications (see Box 2 below).

- A conflict and capacity mapping effort in 13 countries, to identify the response mechanisms and support services available to survivors.

In addition, UK funding has indirectly contributed to support for survivors through providing funding to the Victims’ Rights Advocate to develop a Victims’ Rights Statement, and to the UN Office of Internal Oversight Services to develop and deliver training for national investigators on effective and sensitive child forensic interviewing techniques.

In March 2016, the UN established a Victims’ Assistance Fund to provide economic support to survivors. It provides some redress for the lasting economic hardship that survivors can suffer, for example through the birth of additional children or stigma and ostracism from their communities. So far, however, the UK is not among the 21 countries that have contributed to this fund.

Given the persistence and urgency of the SEA challenge and the difficulties of improving discipline among UN peacekeeping troops, the UK approach does not appear to have a sufficient level of programming targeted at country-level support for and engagement with survivors. This is not in line with clear evidence from the literature on the need to take a survivor-focused approach that simultaneously works both to increase perpetrator accountability and to provide support for survivors and local communities.

Conclusions on relevance

The UK has played a prominent role in strengthening the UN’s capacity to prevent and respond to SEA in international peacekeeping. The main focus of UK aid spending in this area has been to support policy reform and disciplinary procedures within the UN, principally through the funding of staff positions. Having these disciplinary procedures in place – and trained staff to implement them – is relevant, necessary and important. Without these efforts, there would be no way for survivors to report abuse, and no information about the scale of the problem and whether it is being tackled effectively.

The MOD’s support for training and awareness raising among international peacekeeping troops is also highly relevant, potentially contributing to improving international peacekeepers’ knowledge and understanding of required standards for behaviour and procedures for how to respond to SEA when they encounter it.

There does not seem to be sufficient focus on support for survivors in the UK approach, given the structural challenges involved in changing the cultures and behaviours of peacekeeping missions.

Effectiveness: How well have these initiatives delivered on their objectives?

The UK has promoted some high-profile reforms to UN peacekeeping and helped to lay down the standards expected of peacekeepers

The UK’s funding and diplomatic support has directly contributed to a number of high-profile reforms within the UN. Funding for positions like the Special Coordinator on Improving the UN Response to SEA and the Office of the Victims’ Rights Advocate has helped to focus international attention on SEA. The UK has been instrumental in developing cross-UN human resource policies and mechanisms for addressing SEA, which have also been shared with NATO and the AU. The Clear Check system referred to in paragraph 4.9 above is another useful reform. The Clear Check database is currently being rolled out, with most UN entities committing to use the system.

These efforts have helped to establish a normative framework around SEA, outlining the standards expected of peacekeeping troops, police and civilian staff. While these initiatives have been mainly at headquarters level, stakeholders we interviewed in the DRC noted that they had also resulted in greater focus on SEA within MONUSCO, the international peacekeeping mission in the DRC. Through the work of a UK-funded gender adviser seconded from the MOD, MONUSCO has developed theories of change for both conflict-related sexual violence and SEA. The adviser informed us that there are signs of greater awareness of SEA among peacekeeping personnel. However, there is no monitoring system or data available that allows us to evaluate the extent to which this awareness has led to changes in behaviour. As we have seen, reports commissioned or written by the UN in recent years suggest that the culture of impunity continues to be widespread.

While efforts to train peacekeepers on SEA show promise, the results from these training activities are yet to be demonstrated

The UN is limited in its legal authority to take action against peacekeeping soldiers. Some countries, such as the United States, have put diplomatic pressure on troop-contributing countries to discipline their forces. The UK has taken the different approach of working directly with peacekeeping troops through the training and mentoring efforts of the British Peace Support Team (BPST) based

in Nairobi.

The BPST trains over 10,000 African peacekeeping personnel each year. Using a training-of-trainers format, its courses cover both conflict-related sexual violence and SEA. Its pre-deployment training for soldiers in AU and UN operations aims to instil behavioural norms to prevent SEA and an understanding of the effect that SEA has on local communities. Following completion, participants are added to WhatsApp forums moderated by BPST staff and encouraged to host training sessions with mission colleagues and local communities.

The BPST told us of examples of the training-of-trainers process at work. For instance, in Kenya, a female participant now leads a prevention project that engages elders in awareness raising about child abuse. Thanks to pressure from the UK government, all peacekeeping soldiers, regardless of whether they have been trained through the BPST, receive ‘No Excuse’ pocket cards with rules for behaviour and information on how to prevent and report SEA. The UK government is working to expand the training to more troop-contributing countries, including NATO members.

BPST leadership also builds mentoring relationships with high-ranking officers from partner countries. These relationships represent potential valuable pathways to impact, although they are limited in scope by their one-to-one nature.

The BPST has recently developed a monitoring and evaluation toolkit, ‘TASER’, with the objective of measuring the impact of the training courses on participants’ knowledge and awareness of SEA. This is a useful initiative, but limited in scope. It does not yet have a systematic way of tracking the behaviour of peacekeeping troops once they have left training. Currently, the BPST does not track trends in the reporting of SEA allegations once troops are deployed. While we recognise the measurement difficulties involved, without collecting evidence of long-term changes in institutional and cultural practices within peacekeeping contingents, it is impossible to gauge the impact of the training.

UK aid funds few local-level projects aimed at empowering and supporting survivors of SEA in international peacekeeping in their communities

We found one example of the UK funding a programme on SEA in international peacekeeping that directly focuses on survivors and their communities: a community engagement project run by the UN Department of Peace Operations’ Communications Office. The first phase of this programme, Redress for Victims of SEA, was piloted in peacekeeping settings in CAR and the DRC, before being expanded to Haiti and South Sudan. It has identified community leaders to work with and has established community-based complaints networks and hotlines, supported by outreach and awareness raising through social media. In April 2019, the project was renewed under the name Taking Action to End SEA, and expanded to include capacity building for UN leadership at headquarters and in missions (see Box 2 for more detail on its activities).The project has recorded increases in SEA reports and requests for information from its target communities following awareness-raising campaigns, which is encouraging.

Box 2: Community engagement activities in CAR, the DRC, Haiti and South Sudan

Redress for Victims (April 2017 to October 2018) and Taking Action against SEA (October 2019, ongoing) are two phases of a community engagement project implemented by the Department of Peace Operations’ Communications Office and funded by the CSSF. The objectives are to engage ‘at-risk’ communities directly adjacent to each mission in response and prevention activities, and to improve how missions communicate externally and coordinate internally on SEA. The project is active in CAR, the DRC, Haiti and South Sudan.

The project has established community-based complaints mechanisms that have provided over 20,000 people in 50 high-risk communities with improved access to reporting mechanisms. The Victims’ Assistance Fund supplemented the work with a livelihood programme for survivors in the DRC.

The two projects employed a variety of prevention activities, including SMS campaigns and radio programmes, an ‘SEA Stand-down Day’ in South Sudan, and partnership with local civil society organisations in Haiti. More than seven radio spots in local languages were run on local stations in Haiti, the DRC and CAR. In the days following these communications campaigns, the Conduct and Discipline Teams in each mission saw a spike in calls to the hotline asking for more information or to file a complaint.

Overall, however, UN statistics show mixed results so far for efforts to help survivors report cases of sexual exploitation or abuse perpetrated by members of international peacekeeping missions. SEA allegations recorded by field operations across all missions decreased from 104 in 2016 to 63 in 2017 and 56 in 2018, followed by an increase to 80 in 2019. We would have expected that the work of the Victims’ Rights Advocate and related initiatives would result, if successful, in a rise in SEA reports, at least until such time as efforts to reduce the incidence of SEA took effect. This increase is not apparent from the data, suggesting that more needs to be done in giving survivors the confidence to come forward. It is likely, however, that those survivors who do come forward are now receiving a better level of support from the UN.

Conclusions on effectiveness

The impact of the efforts to support the international peacekeeping community in tackling SEA is difficult to judge. The UK has certainly been instrumental in some important reforms, including the introduction of a tracking system for allegations against individual UN staff. It has helped to raise awareness among UN agencies and troop-contributing countries of the importance of addressing SEA. However, there remain significant institutional, legal and cultural obstacles to effective prosecution of SEA violations, and the UN’s own reporting suggests that effective investigation and prosecution of allegations remain the exception. There is no evidence as yet of a reduction in the overall incidence of SEA.

The UK’s efforts to train peacekeeping troops appear useful and important, helping to shift the knowledge and understanding of peacekeepers before they are deployed. However, considering the level of training taking place, it is striking that more efforts were not made until very recently to track the results of the training.

Learning: How have responsible departments sought to learn from, and apply learning to, programming on sexual exploitation and abuse by international peacekeepers?

So far, there has been little production and sharing of learning on SEA

Most of the UK’s aid investment to tackle SEA in international peacekeeping funds staff positions and internal UN reform, without a structured approach to monitoring and learning. Only a few scattered initiatives have been undertaken to build a body of knowledge and evidence upon which to base SEA programming. Examples include the UK-funded mapping exercise led by the Office of the Victims’ Rights Advocate in 2018, renewed through 2020, and the MOD’s TASER initiative, which monitors the effectiveness of training by the BPST in Nairobi.

The Redress for Victims and Taking Action projects included some evidence gathering and learning, including annual reports and some output monitoring. However, data on the results of UK funding and UN reforms – including on trends in SEA prevalence and reporting rates – remains limited. Finally, MONUSCO’s most recent force gender adviser is producing a review of evidence on the utility and challenges of female, as opposed to mixed, engagement teams, which is potentially valuable.

In our Preventing Sexual Violence in Conflict Initiative (PSVI) review, we expressed concern at the lack of a structured approach to learning and filling evidence gaps on ‘what works’. The same lack is apparent in relation to SEA in peacekeeping. We also noted the importance of making survivor well-being the guiding principle of interventions. While this and other lessons from PSVI are clearly relevant to SEA, we find that the lack of a strong institutional link between SEA, PSVI and related UK aid programming on conflict-related sexual violence is inhibiting the sharing of learning.

Conclusions on learning

The UK government could certainly do more to contribute to systematic learning efforts on how best to overcome the entrenched cultural and bureaucratic barriers to preventing SEA in international peacekeeping and achieving justice for survivors. It could also link its learning activities on SEA to PSVI and other efforts to tackle conflict-related sexual violence, in order to build an integrated body of evidence available across UK departments.

Conclusion and recommendations

Conclusion

The UK is a leading voice on addressing SEA in international peacekeeping and has played an important role in raising awareness of the issue. While the UK aid programming on SEA in international peacekeeping has been limited in scope, it has helped to articulate the standards expected of peacekeepers and to strengthen UN systems for responding to SEA complaints. The MOD’s training activities through the British Peace Support Team are helping to raise awareness of SEA among peacekeeping troops and may contribute to changes in their behaviour.

While these are relevant and useful initiatives, there is limited evidence at this point that they have reduced the overall incidence of SEA in peacekeeping missions. Given the long-term nature of that challenge, the UK approach appears to have an insufficient focus on working directly with survivors and vulnerable communities.

The UK government has opted to treat SEA in peacekeeping separately from the Preventing Sexual Violence in Conflict Initiative (PSVI), mirroring the approach taken by the UN itself. However, the lack of a stronger institutional link between the two results in missed opportunities to join up two closely related areas of work – particularly in the important area of support to survivors – and to share learning on ‘what works’. With the merger of the FCO and DFID into a new Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office, there is an opportunity for the UK government to integrate better its work on SEA in peacekeeping into its broader aid efforts to tackle conflict-related sexual violence.

Recommendations

Recommendation 1

The UK government should aim for closer integration and sharing of learning between its efforts to tackle SEA in international peacekeeping and its wider work on conflict-related sexual violence.

Problem statements:

- Like the UN itself, the FCO addressed SEA in a relatively narrow manner, primarily as a conduct and discipline issue.

- FCO activities to tackle SEA were mainly conducted separately to the department’s PSVI programme, with different institutional homes for the two.

- The FCO’s activities to tackle SEA were not informed by DFID’s large portfolio of programmes on violence against women and girls, including conflict-related sexual violence.

- The lack of a strong institutional link between SEA, PSVI and related UK aid programming on conflict-related sexual violence across government departments has inhibited the sharing of learning and has been an obstacle to achieving synergies between UK aid efforts in these closely related issue areas.

Recommendation 2

The UK government should ensure that efforts to improve discipline among peacekeeping personnel are balanced with measures to promote the interests and welfare of survivors.

Problem statements:

- UK aid did not adjust its SEA focus to go beyond conduct and discipline when the UN did, to focus on the challenges survivors and witnesses face when trying to report and seek justice for SEA violations.

- We only found two programmes funded by UK aid that had a direct survivor focus.