When aid relationships change: DFID’s approach to managing exit and transition in its development partnerships

ICAI Score

We have examined DFID’s approach to ending its bilateral aid relationships with particular countries (“exit”) and transitioning to new development partnerships (“transition”).

We found that DFID’s objectives around exit were clear and its implementation of them broadly effective. DFID’s planning for exit in Vietnam in particular stands out as an example of strong practice. However, we also identified several areas of weakness, particularly around communications and relationship management. There were no structured processes for capturing and sharing lessons between countries which, in our estimation, weakened performance overall.

We found significant shortcomings in DFID’s approach to transition. One exception was Indonesia, where DFID’s decision to focus on climate change created a sound basis for a new development partnership. In China, India and South Africa, however, DFID was slow to translate its high-level transition objectives into detailed plans for its new partnerships. Weak or disrupted communication also generated uncertainty among national stakeholders as to DFID’s intentions and, in some cases, risked undermining the good work that DFID had been doing.

Finally, despite clear public statements on ending bilateral or financial aid to these countries, DFID has not communicated clearly the extent to which it is continuing other forms of aid as part of its evolving development partnerships.

While the exit process was effective in many respects, our concerns around the

management of the strategically important transition country cases have led us to award DFID an overall amber-red score.

Executive Summary

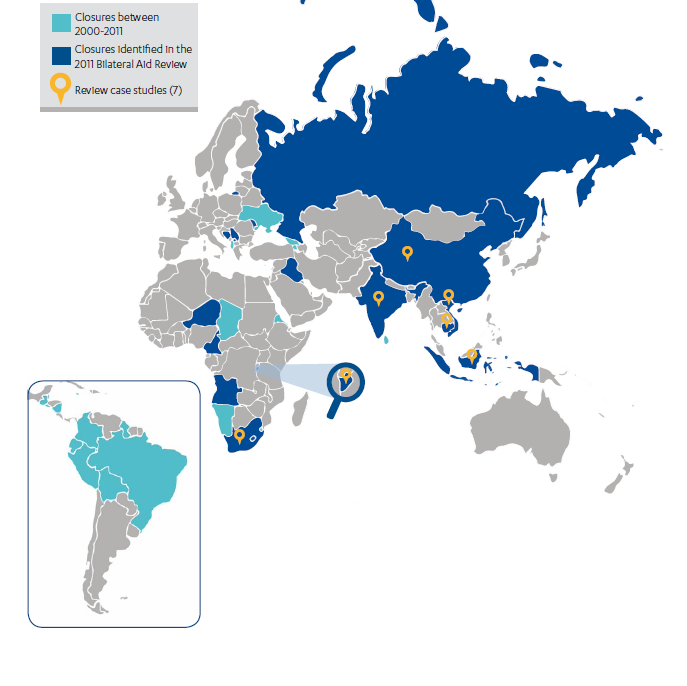

In recent years, the UK government decided to withdraw the bulk of DFID bilateral aid from several middle-income countries, such as China, India and South Africa, and to consolidate the aid programme into what is now 32 priority countries.1 This meant phasing out bilateral aid in 18 countries.2

The merits of this decision were the subject of widespread debate. Middle-income countries are no longer dependent on external assistance to finance their national development, and there was sharp criticism in parts of the UK media of providing aid to countries that were increasingly important economic powers in their own right. At the same time, China and India remain home to nearly half of the world’s poor, and continuing progress in middle-income countries is regarded as essential to achieving international development goals.

During the period 2011 to 2015, the UK government’s position was that the greatest impact and value for money for the UK bilateral aid programme could be achieved by focusing on a smaller group of low-income countries. It nonetheless identified that middle-income countries should remain important partners in addressing domestic and global development challenges.

During the period 2011 to 2015, the UK government’s position was that the greatest impact and value for money for the UK bilateral aid programme could be achieved by focusing on a smaller group of low-income countries. It nonetheless identified that middle-income countries should remain important partners in addressing domestic and global development challenges.

The topic of transition is of considerable strategic interest. Many of DFID’s partner countries have increasing access to other sources of development finance and are no longer dependent on financial aid. In addition, under the 2015 Aid Strategy and the Strategic Defence and Security Review, the government announced its intention to use the aid programme to address global challenges such as insecurity, migration and promotion of the conditions for global prosperity. As the International Development Committee has pointed out, to meet these challenges and achieve the Global Goals, DFID needs to look beyond aid to other forms of development cooperation.3 Its ability to manage the transition from traditional aid into new kinds of development partnerships will be an important aspect of the new development agenda.

This review explores how well DFID managed the process of exiting from bilateral aid and, in some cases, transitioning to new development partnerships. We are not reviewing the merits of the decision to consolidate the aid programme, which is a policy question and outside our scope. We explore whether the exit and transition processes met the UK’s strategic objectives and were implemented in such a way as to protect past development gains, where feasible, and to create a basis for future cooperation. This is a performance review, addressing relevance, effectiveness and value for money, with a strong interest in learning to inform future changes in aid relationships.

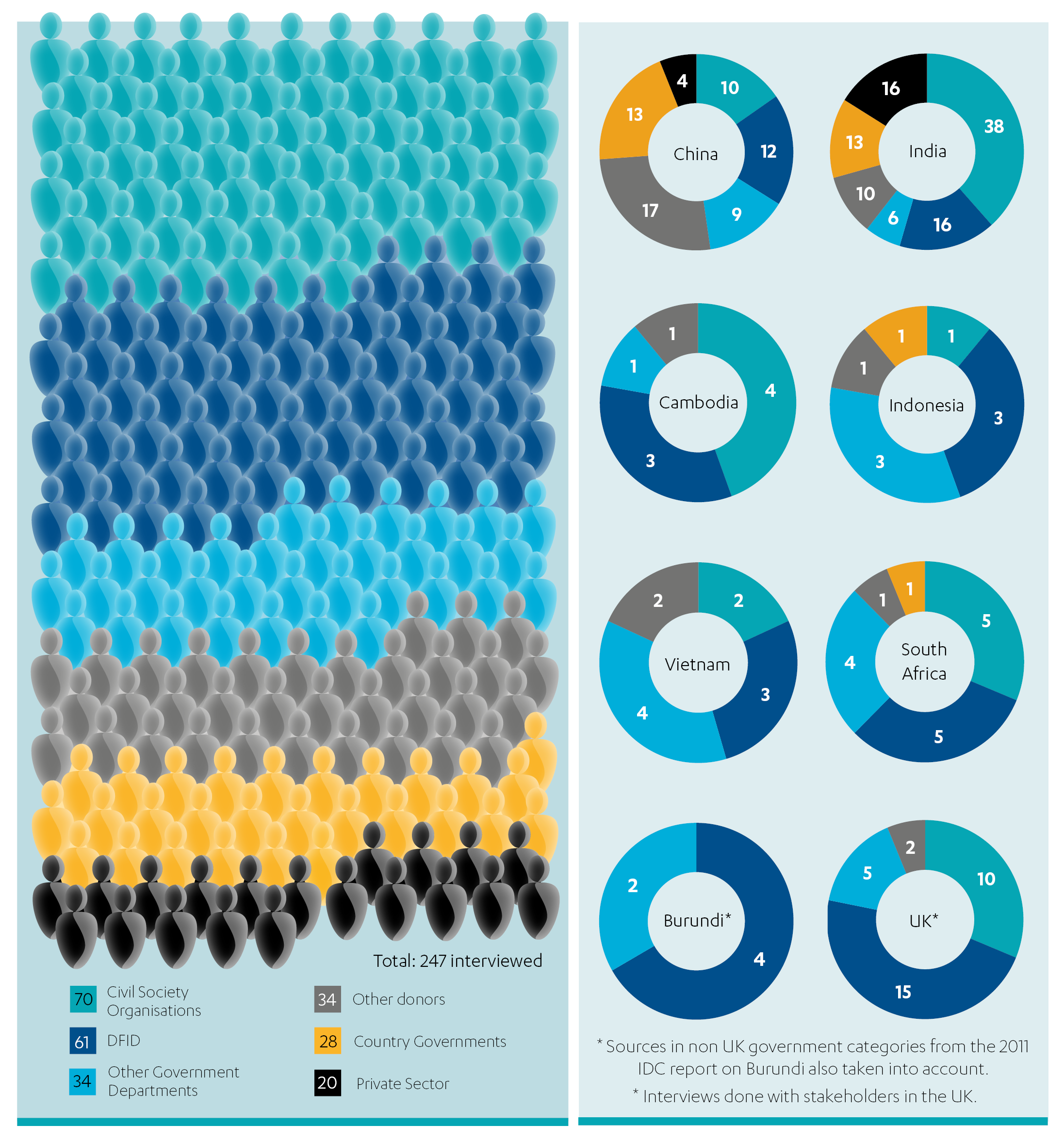

Our review was based on case studies of seven recent exits or ongoing transitions – Burundi, Cambodia, China, India, Indonesia, South Africa and Vietnam. In two cases, China and India, we conducted country visits. We also reviewed a range of DFID documentation and carried out more than 240 interviews with DFID, other UK government departments, partner country officials, other donors, the private sector and civil society.

Box 1: Exit and transition

DFID does not have standard processes for phasing out bilateral aid, and its terminology has changed over time. In this review, we use the term “exit” to mean the process of phasing out DFID bilateral assistance programmed at

In this review, we use the term “exit” to mean the process of phasing out DFID bilateral assistance programmes at country level. This does not necessarily mean a complete end to UK aid, which may continue through centrally managed programmes, multilateral channels or via other government departments. All of our seven case studies involve exit from bilateral or financial assistance4, in whole or in part.

We use the term “transition” to mean the establishment of a new development partnership. In the case of China and South Africa, DFID identified that, while it would no longer provide large-scale assistance on domestic development issues, they remained important partners in addressing regional and global development challenges, and could continue to receive some UK aid to tackle these issues. In India, DFID transitioned from a focus on service delivery to economic development. It has ended financial aid, but continues to provide development capital investment and technical assistance, focused both on domestic challenges and on helping India build its capacity as a donor country. In Indonesia, the new development partnership is focused on the country’s response to climate change.

How relevant was DFID’s approach to exit and transition?

DFID has no standard approach to managing exit or transition. Its guidance on the subject dates back to 20115 and is limited to procedural matters. To assess the relevance of DFID’s approach, we therefore considered each individual case against its own objectives.

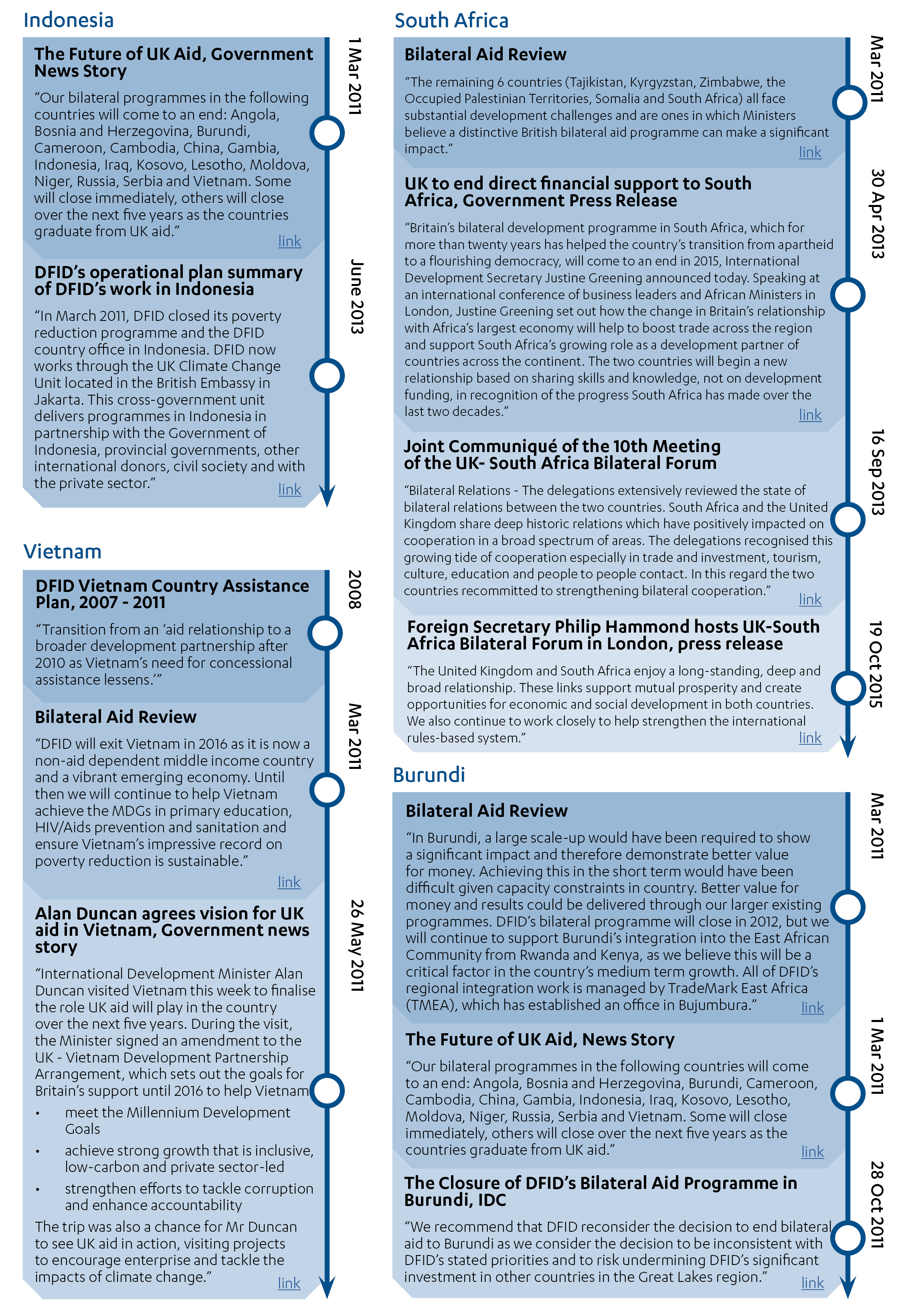

We found that, in the cases where DFID was solely interested in exit (Vietnam, Cambodia and Burundi), its objectives were clear and relevant to UK government policies at the time. The priority was to consolidate the aid programme by withdrawing from countries able to finance their own poverty reduction efforts or where other donors were better placed to help. To this end, DFID set down detailed exit plans governing matters such as staff reductions and the timing of programme closure.

However, in cases where DFID was transitioning to a new development partnership (China, India, South Africa and Indonesia), the picture was less positive. DFID’s detailed planning was limited to the narrower agenda of exit. In three of the four transition cases (China, India and South Africa), DFID did not articulate clearly what this new partnership might look like or how it would be developed. While its high-level objectives were shared with partner governments at a senior level, DFID did not communicate its intentions clearly to important national stakeholders. This resulted in misunderstanding and miscommunication, at some cost to its relationships. The lack of clarity in these transition processes may have reflected a wider uncertainty in DFID at the time as to its role in middle-income countries. Indonesia was the exception, as DFID and the Indonesian government readily agreed to focus the new partnership on climate change.

In all of the cases we examined, even where DFID’s in-country programmes were brought to an end, significant aid flows have continued through other channels. In China, DFID terminated all assistance on domestic development issues, but continues to spend £8-10 million per year from centrally managed programmes on helping China to become a more effective donor and investor in developing countries.

In India, DFID terminated “financial aid”, as announced, but continued with technical assistance and a substantial development capital investment portfolio (aid-funded loans and equity investments). There is also substantial UK aid flowing to India through other channels, and both India and China will be beneficiaries of substantial financial assistance from the new Prosperity Fund.6

While DFID’s public statements on the subject have been accurate, the earlier publicity given to exit from China and India potentially created an impression that all aid was being phased out. Against that background, the reasons for continuing and then scaling up assistance have not been clearly communicated to the UK public.

In most cases, DFID did not manage the exit process in such a way as to minimise the risk of development reversals and protect its past aid investments. There were some good examples. In Vietnam, for instance, DFID identified a set of development priorities to pursue during its final phase, while in India it retained a flexible technical assistance fund. However, we identified instances where small, targeted investments during the exit process could have helped to maximise the value of aid programmes that were being phased out. They could also have helped DFID retain a stronger voice in national policy dialogue on continuing development challenges, including with civil society and other development partners. National stakeholders in both China and India stressed to us that, even though DFID financial aid was no longer essential, they would appreciate DFID’s continuing policy advice and technical support.

DFID’s decisions to phase out bilateral aid can have important implications for its local civil society partners. Many have faced a sharp reduction in funding, at a time when other donors were also exiting, and also a loss of access to policy makers. In India, stakeholders from both government and civil society raised concerns that the space for civil society had narrowed as a result of DFID’s transition, potentially putting at risk many years of past UK investment. By contrast, in South Africa, DFID helped some civil society partners access centrally managed DFID funds to smooth over the transition period. In Indonesia, civil society partners remain important collaborators in DFID’s work on climate change.

Overall, we have awarded DFID’s approach to exit and transition an amber-red for relevance. DFID was necessarily and appropriately focused on implementing the government’s decision in 2011 to consolidate the aid programme through orderly exit. However, in countries where it set out to transition to a new development partnership, DFID did not articulate clearly, either for its own planning purposes or to national stakeholders, what that new partnership would consist of and how it might be developed. Across our cases we found instances where DFID’s communication around the continuation of aid funding could have been made clearer, both to the public at home and in the recipient country.

How effectively has DFID managed exit and transition and secured value for money?

DFID managed the core business of ending aid programmes and other operations in an orderly and effective manner. Vietnam stands out as an example of best practice. DFID Vietnam produced a strong exit plan, based on broad consultations. It worked systematically to identify other development partners and national authorities to take over leadership of critical development themes and initiatives. Its communications with the Vietnamese government were effective, and there was a strong focus on lesson learning. DFID’s management of exit in Cambodia and Burundi was also broadly effective.

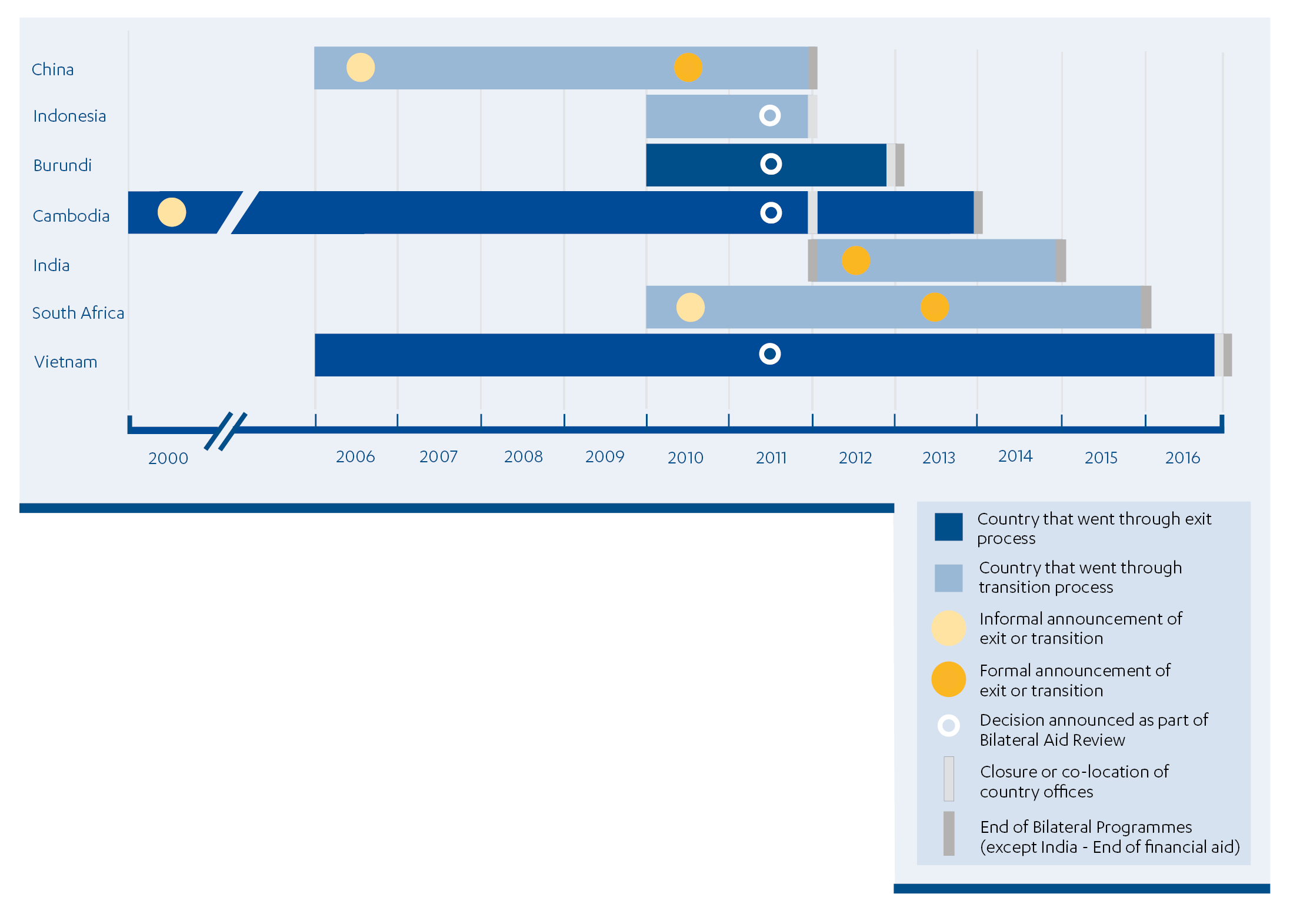

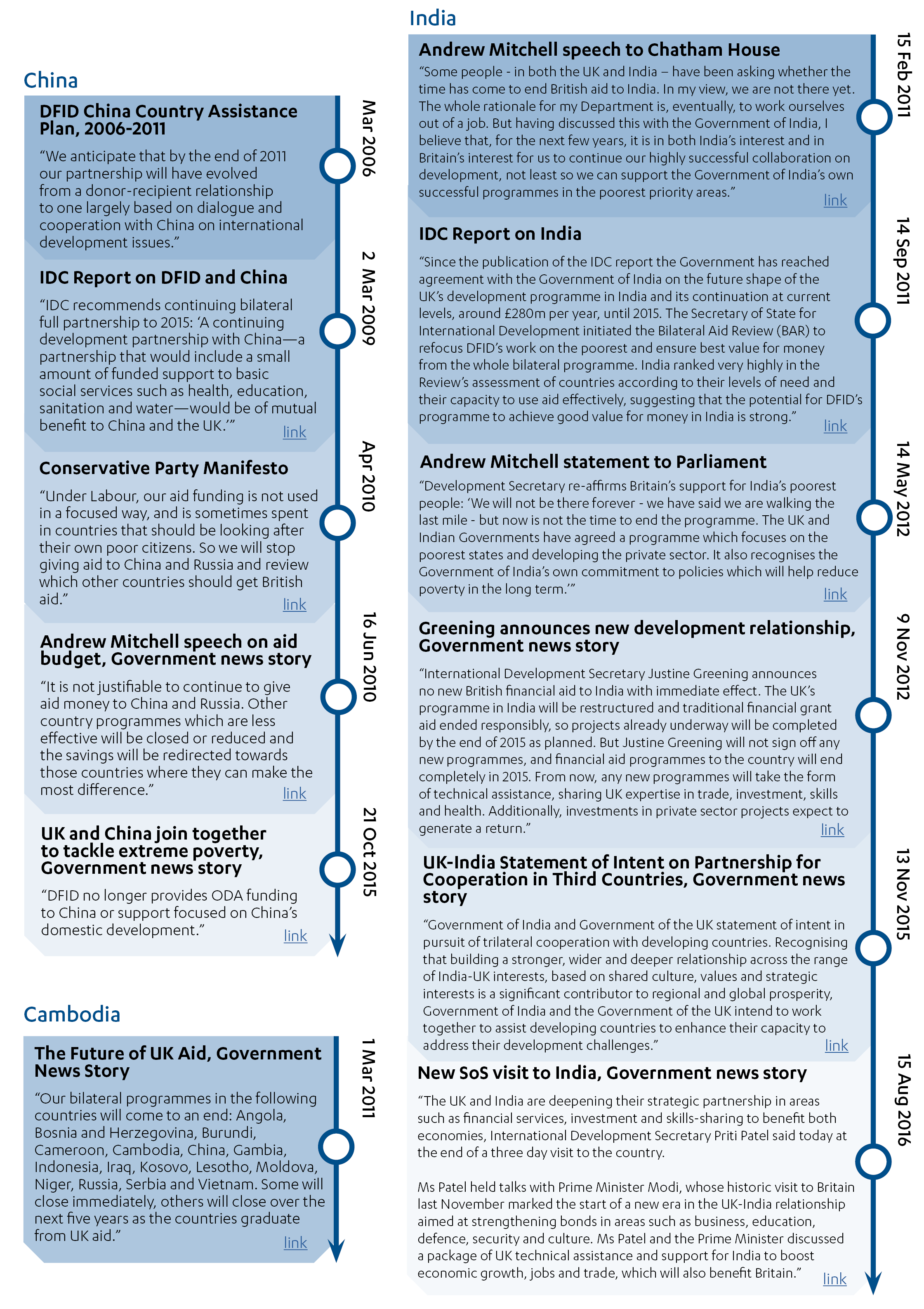

However, we also found significant management weaknesses in all seven cases. In both China and India, DFID cut short some programmes in order to meet deadlines, with consequences for its partnerships and the value of its previous investments. Both government stakeholders and DFID staff in several countries told us the transition timeline was too quick, with as little as nine months in China between formally announcing the end of bilateral aid and closing programmes (see the timeline in Figure 4).

DFID gave insufficient attention to ensuring that country teams had the necessary skills in place to support the exit and transition processes. Although staff reductions were usually handled appropriately and national staff were supported into new positions where possible, central DFID human resource policies left UK-based staff at risk of redundancy once their office closed, causing some to leave prematurely. In several cases, there was a loss of staff continuity, for example in India where the head of office was reassigned to manage the Ebola crisis in West Africa. In Indonesia, a lack of staff continuity held back the transition process for up to two years in the view of some stakeholders.

Both exit and transition were marked by serious communication errors, including poor sequencing of announcements and inadequate consultation. We note two instances, in India and South Africa, where joint communication plans with the partner countries were overtaken by events outside of DFID’s control.

Nonetheless, we found overall that DFID did not manage its communications and resulting risks to relationships through the critical phase of the transition consistently well.

We saw some evidence of DFID collaborating with other UK government departments in practical areas such as sharing offices. We also noted some examples of effective coordination at country level, notably in India and Indonesia where inter-departmental units were created to manage specific issues. However, we saw little evidence of DFID actively passing on knowledge or relationships to other departments, or of this being sought. The resulting gap became particularly apparent during the development of the new cross-government Prosperity Fund in 2015-16, as DFID initially lacked a common approach to working with the Fund. This is now evolving rapidly, and the Prosperity Fund is the subject of a forthcoming rapid review by ICAI in 2017.

The UK government’s decision to exit from a group of countries was in part motivated by a desire to achieve greater value for money in the aid programme. As this was a policy choice, we have not reviewed whether greater value for money was actually achieved through this consolidation. With regard to DFID’s management of exit and transition, we observed a positive approach to value for money in Burundi, where DFID identified that this could be improved by phasing out its country office and passing functions to a regional programme.

In Vietnam DFID’s planning for exit also demonstrated close attention to value for money – for example, the use of VFM audits to guide the closure of programmes. Elsewhere we did not see explicit consideration given to value for money, whether through specific assessments or in key management decisions about transition. The absence of evidence is not the same as finding evidence of poor value for money, but it does indicate that DFID’s approach to assessing value for money at operational level was not consistent across the cases.

We have therefore rated the effectiveness of DFID’s exit and transition as amber-red. While some of the core tasks of ending bilateral aid programmes were handled well, the process was deficient in a number of areas, including skills management, communications and relationship management.

Is DFID capturing and applying learning on transition?

Several of our DFID interviewees were sceptical that lessons could usefully be learnt around transition, due to the unique circumstances of each case. However, we found that in practice all seven cases raised a common set of challenges in areas such as consultation, planning, sequencing, staffing and communications.

DFID has not systematically captured lessons from its transition experience, either at country or at central level. Among our case studies, a number of country teams sought out lessons-learnt material from earlier transitions, but found very little. We also found little evidence of DFID learning from other donors. DFID Cambodia conducted a lesson-learning process, but the findings were not well used. As a result, any sharing of learning was informal in nature and limited in scope.

The lack of learning reflects the absence of a central point in DFID for coordinating, supporting or learning lessons on transition. DFID’s only specific guidance, which focuses on the practicalities of closing programmes and offices, dates from 2011,7 and has not been updated to reflect recent experience or the changed strategic context.

Due to the limited central support or guidance and the absence of structured learning processes, we have given DFID a red rating for learning, our lowest rating. DFID’s failure to learn from past experience is a significant factor in its underperformance on exit and transition.

Conclusions and recommendations

DFID’s approach to exit reflected the government’s objective of consolidating the aid programme by phasing out bilateral or financial aid from these seven countries. It prioritised achieving an orderly exit and delivered on this objective effectively. However, with the notable exception of Vietnam, poor planning led to weaknesses in a number of areas, including staffing, communications and relationship management. DFID’s failure to capture and share lessons centrally, despite a clear demand from country offices for support and guidance, contributed to these failings.

We identified significant shortcomings around the planning and implementation of transition. DFID failed to translate its high-level goals, including new partnerships on global development challenges, into specific

objectives to inform planning. Poor communication with partners around the nature and objectives of its new development partnerships left national stakeholders uncertain as to DFID’s intentions.

The decision to continue to use non-financial forms of aid in India and to continue with centrally managed programmes in China was not well communicated and, on the back of clear public signals around aid exit, opened up the possibility of misunderstanding by local stakeholders and the UK public. We have therefore awarded DFID’s approach to transition an amber-red score overall, indicating unsatisfactory achievement across a range of areas.

We have made four recommendations to DFID.

Recommendation 1

DFID should establish a central point of responsibility for exit and transition and redress the lack of central policy, guidance and lesson learning. In future cases, it should articulate clearer objectives at the strategic and operational levels and make more consistent use of implementation plans.

Recommendation 2

DFID and other UK government departments should work together to improve relationship management with bilateral government partners through transition. This should include joint risk management and more coordinated communications.

Recommendation 3

DFID should report and be accountable to UK taxpayers regarding commitments to end aid or change aid relationships in a transparent manner. It should state clearly which parts of aid spending will end and which will continue, and this information should be readily accessible to the public.

Recommendation 4

During exit and transition, DFID should assess the likely consequences for local civil society partners, including both financial and other impacts, and decide whether to support them through the transition process.

Introduction

This review examines how well DFID has managed the transition of its partnerships with developing countries following decisions to end bilateral aid. Since a 2011 decision to consolidate DFID aid into 28 priority countries,8 (later increased to 32), UK bilateral aid has been phased out in whole or in part in 18 countries.9 In some cases, this meant an end to the development partnership;10 in others, there has been a transition to new partnerships, including on economic development and global development challenges.

This review does not examine the government’s decision to end aid to any particular country; that is a policy issue and not within ICAI’s remit. Rather, we look at how DFID managed the transition process. Did its approach meet the UK government’s strategic objectives? Was it done in such a way as to protect development gains from past UK aid investments and maintain a constructive relationship with the countries in question?

The topic of transition is of considerable importance to the future of UK development cooperation. Patterns of global development finance are changing rapidly. In developing countries, domestic revenues and private financial flows are growing faster than official development assistance (ODA).11 At the July 2015 International Conference on Financing for Development, it was recognised that, in the future, ODA will increasingly be used to leverage other sources of development finance, rather than fund development programmes directly.12 As the International Development Committee concluded, this means that DFID needs to look “beyond aid”13 to other ways of supporting international development – such as catalytic investments, knowledge partnerships and cooperation on global challenges like climate change and irregular migration.14 DFID’s approach to transitioning to new aid partnerships is a key element in how it positions itself to meet these new “beyond aid” challenges.

This is a performance review, with a focus on effectiveness and value for money through the implementation process (see Box 2). It also has important learning elements, not least because the literature in this area is limited. While our focus is DFID’s performance, we have also assessed how well DFID engages with other UK government departments. Our review questions are set out in Table 1.

Box 2: What is an ICAI performance review?

ICAI performance reviews are concerned with the efficiency and effectiveness of UK aid delivery, with a strong focus on accountability. They may also examine DFID’s business processes, to explore whether its systems, capacities and practices are robust. In this instance, the review also includes strong elements of learning, to inform future transitions.

Other types of ICAI review include impact reviews, which examine results claims made for UK aid to assess their credibility and their significance for the intended beneficiaries, and learning reviews, which explore how knowledge is generated in novel areas and translated into credible programming.

Table 1: Review questions

| Review criteria and questions | Sub-questions |

|---|---|

| 1. Relevance: Is DFID’s approach to transition relevant? | • Are the objectives clear and coherent? • Are DFID’s choices about the approach to transition consistent with the goals of protecting development gains and reducing the risks of development reversals? |

| 2. Effectiveness and value for money: How effectively is DFID transitioning to a post-bilateral aid relationship with partner countries? | • How well has DFID managed its partnerships with country governments and other key stakeholders through the transition process? • How well does DFID influence and work with other UK departments to ensure development considerations are embedded within wider UK government bilateral relationships? • How does DFID ensure that it is delivering value for money in the context of such transitions? |

| 3. Use of evidence and learning: How effectively is DFID capturing and applying learning to support its transition approaches? | • How effectively is DFID learning from current and previous transitions and applying this to its guidance, systems and practices? • To what extent is DFID capturing and sharing learning across the government to determine the most strategic whole-of-government transition approaches, including around value for money? |

Methodology

The review employed a range of qualitative methods, at the core of which were a series of case studies of individual transitions. Our methodology consisted of two main components.

i. We undertook a strategic review to assess the wider strategic context for DFID’s approach to transition. This included a review of the limited literature, examination of DFID documents on transition and key stakeholder interviews in the UK with DFID, other government departments and external stakeholders. This enabled us to map the different types of transition, their objectives and how these approaches have evolved over time.

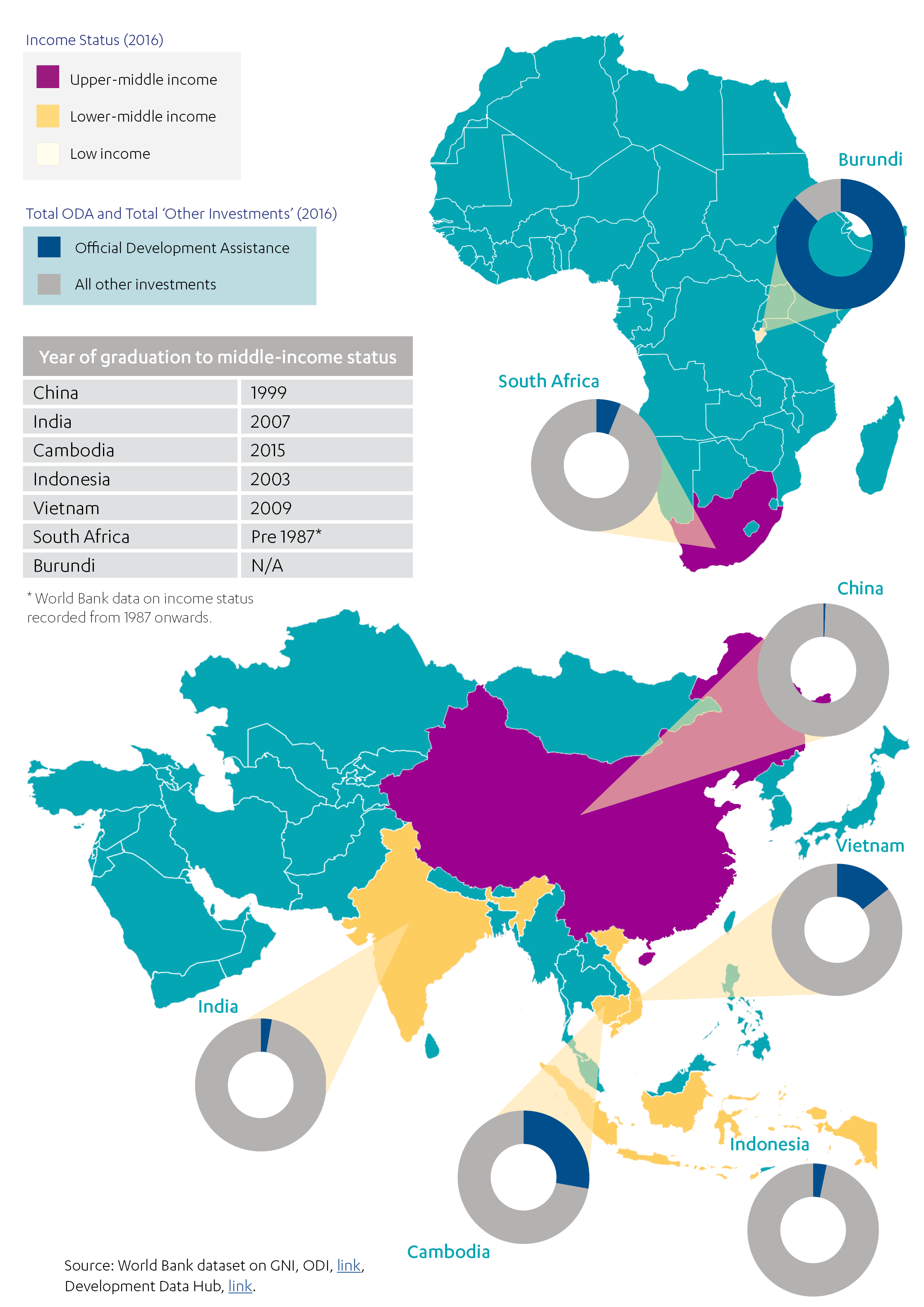

ii. We conducted seven case studies of recent or ongoing exits and transitions: Burundi, Cambodia, China, India, Indonesia, South Africa and Vietnam. In each case, we reviewed relevant documents and interviewed a range of DFID and other government staff involved in the process as well as country stakeholders. We explored the objectives for each exit or transition process and how they influenced the approach taken. The countries were selected to include a variety of transition contexts, to inform future transitions. We conducted in-depth country visits to China and India; the remaining case studies were desk-based. The evidence from each country was documented and then collated into an overarching assessment. The case study countries, their income status and the share of aid in total development finance are presented in Figure 1 (next page).

Altogether we interviewed 247 stakeholders across six main groups: DFID, other UK government departments, partner country officials, other development partners, civil society and the private sector. This is summarised in Annex 6. More detail on our methodology is included in Annex 5 and in

our Approach Paper.15

Box 3: Limitations of our methodology

There are a number of limitations to this methodology. First, as this is an evolving area of practice, many of our case studies are of ongoing or very recent transitions. This limits our ability to explore the consequences of transition in anything more than a provisional way.

Second, transition is not a form of development assistance, and there are no clearly stated objectives against which we can measure performance. There are also no counterfactuals available for comparison. In strict terms, the “evaluability” of the topic is therefore limited.

Third, the small sample size, the limited number of stakeholders who were in a position to comment on each case and the purposive selection of cases all introduce a risk of bias. We mitigated this by including seven country case studies. Our key stakeholders were assigned to groups (eg DFID, other UK

government departments, partner country officials, civil society). Findings from interviews were flagged as coming from particular stakeholder groups. Feedback from each group was collated and triangulated with other groups and the limited literature.

Fourth, five of the country case studies were desk-based only with limited stakeholder interviews due to resource constraints. This means that the evidence collected in these countries was not as comprehensive as it was for China and India.

Finally, the sampling has been done to respond to the review questions overall, rather than to draw conclusions about the performance of any given country. This means that the lessons from the review are more broadly applicable although the extent to which our findings can be generalised to other transition contexts is not without limits.

Figure 1: Our case study countries

Background

The consolidation of UK aid

The global footprint of UK aid has changed rapidly in recent years. In 2008-09, 140 countries received some form of UK bilateral aid,16 with 87 receiving support from DFID alone (although not necessarily through a country office). By 2015, DFID’s aid was concentrated in just 32 priority countries.17

This consolidation of UK aid was a policy of the Coalition government elected in 2010. It formed part of a drive to increase the impact, effectiveness and value for money of UK aid. The 2011 Bilateral Aid Review provided the technical analysis to support the selection of priority countries.18

It used three main criteria for determining the level of priority:

• development need

• likely effectiveness of UK aid

• level of strategic priority for the UK government.

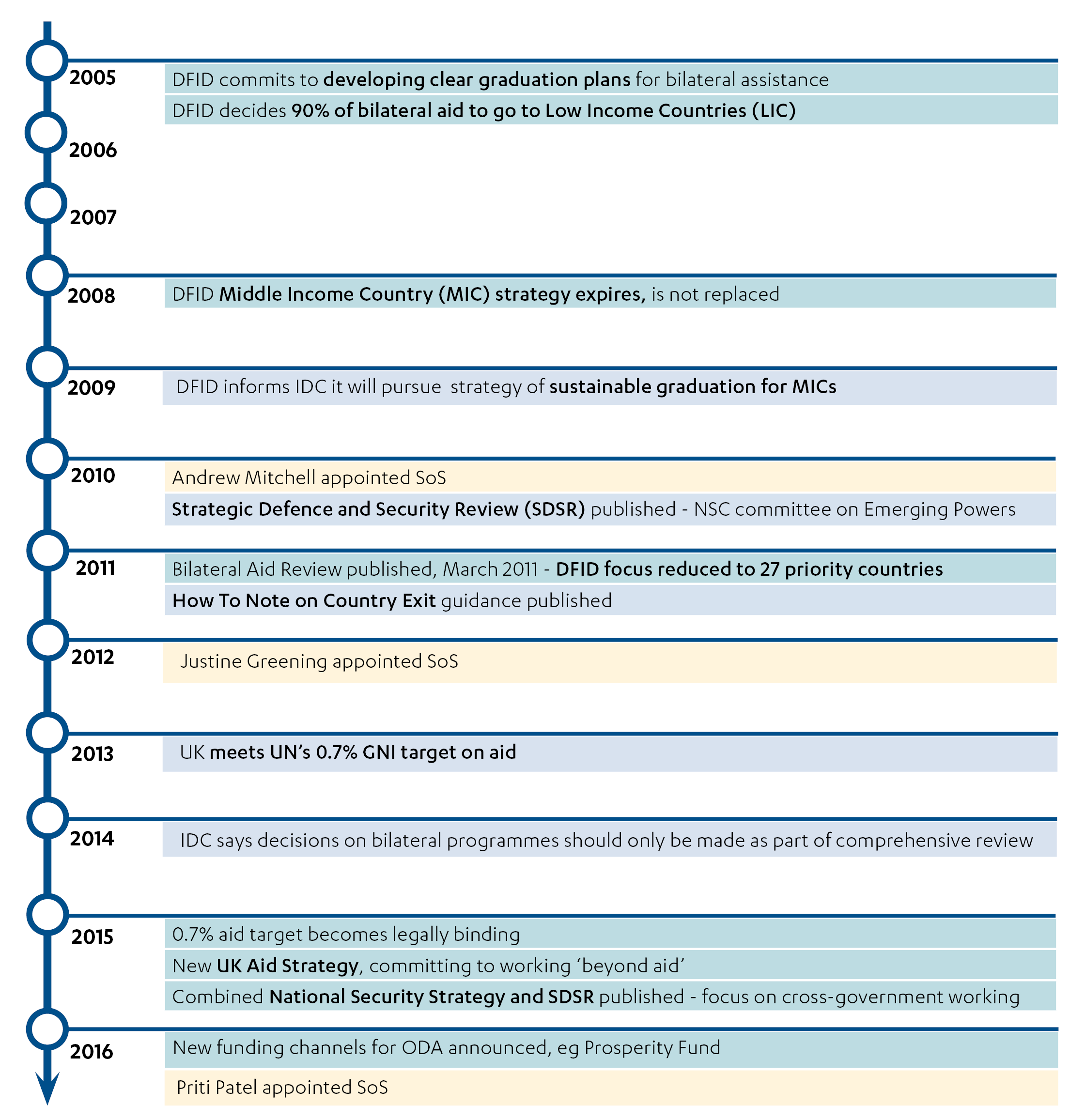

Those countries not identified as priorities were scheduled for exit from bilateral aid, in whole or in part. In addition, three exit decisions were made outside the Bilateral Aid Review process. Ending aid to China was a 2010 Manifesto commitment. Transition from financial aid in India19 and in-country bilateral aid in South Africa were decided later, in 2012 and 2013 respectively.20 In total, 18 DFID bilateral country programmes have been identified for exit over the past five years (see the timeline in Annex 4).21

Types of transition

DFID does not have a standard process for phasing out bilateral aid to particular countries. It has used different terms for the process over time, reflecting shifting objectives and the particular circumstances of each case.

At times, DFID has used the word “exit” to refer to the phasing out of bilateral aid. This has sometimes occurred because the country has reached middle-income status (a nominal threshold of USD 1,025 in gross national income per capita, used by the multilateral development banks as one criterion for

assessing when to end concessional finance). In other cases, it has followed a shift in UK government priorities or a determination that other donors were better placed to assist.

The terms “graduation” and “regionalisation” were used for a period during the 2000s. Graduation referred to the achievement of middle-income status, while regionalisation referred to the consolidation of small country programmes into regional programmes, which occurred in the Caribbean and Central Asia.

More recently, the term “transition” has been used to refer to the phasing out of bilateral or financial aid in favour of new forms of development cooperation. This applies especially to emerging powers22 such as China, India and South Africa.23 While traditional development programmes are phased out, in

whole or in part, the UK seeks to build development partnerships with new objectives. For China and South Africa, the focus is now on working jointly on regional and global development challenges. In Indonesia, the partnership centres on Indonesia’s response to climate change, while in India – which remains one of the largest recipients of UK aid despite the end of financial aid – the objectives include promoting economic development through development capital investments and supporting India’s growing role as a donor country. The transition process may last several years, while aid programmes are phased out and new relationships built. During the process, DFID’s relationships with their key stakeholders may pass to other departments. In some cases, DFID closes its country office altogether; in others, it maintains a presence alongside other departments.

In this review, following the most recent DFID usage, we use two terms: “exit” refers to the phasing out of existing aid relationships and programmes, while “transition” refers to the move towards a new kind of development partnership. All of our case study countries involved elements of exit. In four instances – China, India, Indonesia and South Africa – exit was accompanied by transition to a new kind of relationship. This reflected their greater strategic interest for the UK.24 Our findings on exit therefore cover all seven case study countries, while those on transition come only from four. Table 2 sets out the dimensions of transition in each of the case study countries.

Table 2 : Experience of transition in our case study countries

| Country | Exit - from bilateral aid | Transition to a different post-exit aid relationship? | Office closed? |

|---|---|---|---|

| Burundi | Yes | No | Yes |

| Cambodia | Yes | No | Yes (prior to end of programmes, with final projects managed from Vietnam) |

| China | Yes | Yes – working with China in its role as an international development partner on areas of shared interests, no work on Chinese domestic issues | No – stand-alone DFID China exists, but with fewer staff post transition |

| India | Yes – but only financial aid ended; other bilateral programming continues | Yes – promoting inclusive growth in India through new forms of cooperation, such as development capital investments, continuing technical assistance and working with India on its emerging role as an international donor | No – co-located with the FCO and fewer staff post transition |

| Indonesia | Yes | Yes – focused on climate change | No – co-located with the FCO |

| South Africa | Yes | Yes – working with the country on regional issues | No – co-located with the FCO and smaller post transition |

| Vietnam | Yes | No | Yes |

Box 4: Transition in the literature

The UK is not the only bilateral donor to consolidate its aid programme in recent years; Denmark, Germany, Ireland, the Netherlands and the United States have all done so too. Despite this shared experience, there is little publicly available literature on the subject (our bibliography in Annex 8 lists

several of the key sources). A 2008 Swedish evaluation found that “systemic and good monitoring of exit processes is extremely rare”.25 There has been no comparative study of transition decision-making, planning or implementation.26

The limited literature available highlights a number of risks. Exit decisions are often driven by policy changes or budget constraints in the donor country, leading the development agency to act unilaterally and without due regard to protecting the ongoing relationship. While developing countries may actively

seek new relationships based on trade, investment or technology transfer, donor countries are not always responsive. Decisions on exit sometimes give too much weight to per capita income and not enough to deficits in institutional capacity, giving rise to a risk that past development gains may not be sustained.

The literature also points to weaknesses in the way development agencies plan for and manage exit and transition. They have often gone into the process without clear plans, objectives and realistic timelines.27 Transition to a new development partnership calls for a different set of skills than those required for

winding up aid programmes. Minimal attention has been given to institutional learning.28

In our review of the literature, we identified the following success factors for an effective transition.

• Allow enough time and avoid setting a standard timeframe – every context is different.

• Transparent and timely communication with early warning, keeping recipient countries informed of the process and allowing joint preparation for exits.

• High-level communication of exit decisions to partner countries, and in partnership with the Embassy.

• A transparent and participatory process that involves key stakeholders on the recipient and donor sides, with enough time for joint planning and negotiation.

• Decentralisation of the exit management process allows country teams flexibility in how the process is handled.

• Fulfilment of ongoing commitments is important and is linked to basic principles of partnership.

• Donor flexibility to adapt the budget, which implies going beyond a natural phase-out approach to identify needs for adjustments in current agreements to ensure sustainability.

• Focus on catalytic funding using limited remaining resources to ensure good quality finance to middle-income countries.

• Identify institutional capacity of partner country ability to cope with exit.

• Retain experienced staff (international and local) for the exit process, to ensure continuity in interpersonal relations with key partner institutions.

• Coordinate well across the donor government.

Source: Literature Review of Transition and Exit. A summary bibliography is provided in Annex 8.

Is DFID’s approach to transition relevant?

Is DFID’s approach to transition relevant?

In this section, we explore whether DFID’s approach to transition has been consistent with the UK government’s objectives. We assess whether it has given due consideration to the remaining development challenges in its partner countries, as well as the views of its stakeholders. We consider whether the approach to transition was clear to key actors within DFID and in the affected countries, and to the UK public. DFID’s primary focus was on exit from bilateral aid, reflecting UK government priorities

DFID has no central policy or strategy guiding the objectives of exit and transition and how they should be pursued. It has an internal guidance note, but this is limited to the practicalities of closing programmes.29 There have been a number of papers since 2013 from DFID’s Chief Economist’s Office considering how the aid programme could help its partner countries transition towards self-financed poverty reduction. These are think pieces, rather than official guidance, and relate to the countries’ own transition to middle-income status, rather than transition of the development partnership.30 The lack of a strategy means there is no benchmark against which to measure the practice of transition, other than DFID’s objectives in each case.

Across the case study countries, DFID’s primary objective was achieving an efficient exit from existing bilateral aid programmes. This was articulated in detailed plans concerning the practical challenges of exit, such as closing individual programmes, reducing staffing, closing or relocating country offices and reducing overheads.

The focus on exit was relevant and appropriate to UK government priorities at the time, following the government’s policy decision to consolidate the aid programme into a smaller number of priority countries. In the context of a UK government austerity drive, the consolidation of the aid programme

signalled the government’s determination to achieve greater value for money from an expanding aid programme. It also took place at a time of strong media criticism of aid to countries such as India and China, which were growing economic powers despite being home to a significant proportion of the global poor.

Of our seven case studies, five had reached middle-income country status at the time of the transition decision. Cambodia was still a low-income country, but achieved middle-income status in 2015. Burundi remains a low-income country. However, the Burundi programme was small, and DFID judged that, without a substantial increase in the size of the programme, other donors were better placed to assist. DFID therefore decided to focus its remaining support on Burundi’s integration into the East African Community, delivered through a regional programme (TradeMark East Africa) without a DFID country office.31

The UK government’s decision to de-prioritise certain middle-income countries matched the approach taken by other bilateral donors. Denmark, Ireland, the Netherlands, Norway and the United States all consolidated their aid programmes over the same period. In China, most bilateral donors exited at much the same time. The UK’s approach also mirrored the practice of the multilateral development banks, for whom the achievement of middle-income status by a borrower country is one of the milestones for a transition away from concessional finance.32

Across our case study countries, while DFID’s rationale for exit was clear, it did not articulate detailed objectives in each case or a clear set of principles to govern its approach. The sole exception to this was DFID Vietnam, which set out its plans for “responsible exit”, including making sure that the leadership of development themes and initiatives was passed to others (see Box 11). In other countries and at the central level, DFID left unclear what responsibilities it owed to its partner countries during the exit process in terms of protecting past development gains. We note that, according to the limited literature, it is rare for bilateral donors to give much consideration to the development needs of the partner country during exit.33

Box 5: A possible theory of change for exit

In 2014, DFID introduced the Country Poverty Reduction Diagnostic as the main analytical tool underpinning its country strategies. The Diagnostic states that the end goal of UK aid is to help its partner countries achieve a successful transition to “a self-financed and secure exit from poverty”. In a 2014 internal working paper, DFID’s Chief Economist’s Office suggested that this goal could provide an overarching theory of change for DFID’s transitions. The implication is that, when preparing for transitions out of traditional bilateral aid, DFID might prioritise objectives such as maximising the country’s access to other sources of development finance and building its capacity to continue the poverty reduction agenda.

However, this thinking in 2014 was not reflected in DFID’s planning for exit, which began three years previously. Interviews with staff centrally and across the country cases confirmed that DFID continues to lack an overarching theory of change or clear set of guiding principles for the implementation of exit or

transition.

DFID’s objectives for transition have been poorly articulated

Four of the sample countries – China, India, Indonesia and South Africa – are emerging powers and members of the G20. In these countries, DFID identified that, following exit from bilateral aid, it needed a continuing partnership in order to meet its global development objectives. The objectives were different in each case, depending on the UK’s strategic interest.

• China, as a growing economic power with extensive trade with developing countries, was seen as an important partner in the global fight against poverty. DFID opted to focus on influencing China’s global role, but not to provide any further aid for China’s own development challenges.

• Similarly, in South Africa, DFID documents note its importance as a partner in promoting growth and poverty reduction initially in southern Africa and subsequently across the continent.

• In Indonesia, DFID and the government agreed that their new aid relationship should focus on climate change – an area of mutual interest (see Box 8).

• In India, there was a shift in the objectives and modalities of development cooperation away from financial aid for public services and towards new forms of development cooperation to promote economic development. DFID is also working with India on its global development role.

Box 6: China and India are increasingly important bilateral donors

China and India continue to play a critical role in the fight against global poverty for a number of reasons. They continue to be home to the majority of the world’s poor. The Global Goals cannot be achieved without continuing progress in China and India. Their trade with other developing countries is an important driver of economic growth, particularly in Africa. China and India spent almost USD5 billion in ODA in 2014. For the UK, influencing how these countries act on the global stage is an important element in the fight against global poverty. The UK is also promoting economic growth in both countries through the Prosperity Fund and, in the case of India, through continuing DFID bilateral support.

While these high-level transition objectives were set out in public documents, in three of the cases – China, India and South Africa – we found a lack of clarity in DFID’s planning on how to achieve them. There were detailed plans for phasing out bilateral or financial aid, but a notable lack of specificity on what the new development partnerships should look like or how they would be developed. As a result, stakeholders in all three countries – from government, civil society and other development partners – expressed uncertainty as to the nature of the transition and the objectives of the development partnership.

China’s positions on global development issues and its support for developing countries are shaped by its own values and interests, which may well be different to the UK’s. We would have expected to find more analysis of where common ground might be found, as the basis for a new partnership on global development issues, and where there might be scope for successful advocacy to influence Chinese government practices in developing countries. We would also have expected planning around what new in-country partnerships were needed and how best to use aid funds to support them.

In fact, DFID’s exit strategy (entitled a Change Management Plan) addressed practical issues around the phasing out of bilateral programming, without articulating strategic objectives for the transition. DFID told us this reflected broader uncertainty in DFID China at that time about its longer-term work in China. DFID’s 2016 Business Plan and its predecessor plans34 noted the importance of working with China at the international level, but without spelling out how and on which priorities.

Box 7: DFID’s objectives for transition in China lacked focus

While DFID first signalled its intentions to end aid to China in its 2006 Country Strategy, the formal decision to exit resulted from a Conservative Manifesto commitment from the 2010 election. In 2011, DFID China agreed a Memorandum of Understanding with the Chinese government on working with China on international issues and in third countries. This document set out some broad objectives around “working together on shared objectives for global development issues”. In 2012, an internal strategy for DFID China was developed, which refers to 13 ongoing projects and five planned ones, in the areas of health, agriculture, disaster management, water, forests, trade, extractives, conflict and security, and energy. DFID’s changed priorities were not widely shared beyond senior counterparts in government. A new Memorandum of Understanding was agreed in 2015 refocusing the partnership around the Global Goals and reducing the number of sectors for potential engagement.

In 2016, DFID prepared a new business plan for working in China. This again articulates the vision of working with China on global development issues, but with limited detail as to what this will mean in practice. It sets out three strategic objectives:

i. To maximise the development impact of China’s aid and investments in developing countries.

ii. To positively influence China’s engagement in the international development system and its contribution to global public goods (for example, climate change mitigation).

iii. To ensure China’s development experience informs and contributes to global development best practice, primarily through effective knowledge and experience sharing. This paper goes on to propose a range of outcomes that DFID will target in specific sectors. However, the scope is very broad for such a small office, covering health, mining, infrastructure, corporate responsibility, timber, energy, gender, green finance and aid effectiveness.

Source: DFID internal documents and interviews

In the case of South Africa, the UK government’s policy stance changed over time. Under the 2011 Bilateral Aid Review, South Africa was still considered a priority country. Even though it scored relatively low on measures of aid effectiveness, the review noted that “Ministers believe a distinctive British bilateral aid programme can make a significant impact.35 Two years later, however, the position had changed. In 2013 written evidence to the International Development Committee, DFID assessed that “while challenges remain in South Africa, there was less justification for a continued UK bilateral aid programme in South Africa as the primary means to address these issues. Other mechanisms, including partnerships with the FCO and other UK departments, the provision of small amounts of targeted technical assistance, and continuing to work for an effective response from multilateral agencies, would offer more appropriate ways to engage in future.”36 While DFID has a £3 million technical assistance fund in South Africa, it has not yet stated publicly how it will work with South Africa to promote the Global Goals in Africa.

In the case of India, following the decision to end financial aid, the purpose of UK development cooperation was left unclear to wider stakeholders through a critical part of the transition period. DFID ended financial aid to support service delivery and poverty reduction in the poorest states, but continued with technical assistance and scaled up its development capital investment, to promote economic development (India is the only country where the DFID office directly manages a capital investment portfolio). The changing objectives of UK development cooperation were not clearly expressed to national stakeholders, beyond high-level government contacts. In our interviews, government officials, other donors and civil society representatives were consistently puzzled about DFID’s transition objectives and concerned about missed partnership opportunities.

Box 8: DFID’s decision to transition to a climate-change focus in Indonesia

Prior to transition, DFID Indonesia was a small country office with around 14 staff, with programmes delivered largely through multi-donor platforms and multilateral partners. The programme included a strong focus on governance and climate change. DFID was also beginning to work with the FCO on

counter-extremism, following bombings in Bali and Jakarta. It was also working with DFID centrally on global issues, in recognition that Indonesia was among the middle-income countries with an increasingly important regional and global role.

When it began planning for transition in 2008, DFID debated whether to continue a focus on domestic development challenges or to focus solely on global public goods. While Indonesia was no longer aid dependent, its implementation capacity for development initiatives remained relatively weak. Unlike China and India, Indonesia is not yet a global player on most development issues, except for climate change and avian flu.

A decision was taken to focus the partnership on domestic climate change issues, which are of global significance. A cross-government unit was established, made up of DFID, FCO and later the Department of Energy and Climate Change.37 A number of past DFID programmes, including a forestry programme and work with civil society on accountability, were repurposed to support the new agenda. As discussed below, a lack of continuity in staffing over the transition period hampered the transition process. Overall, though, of our four case study countries that involved transition, Indonesia has been both the clearest in its objectives and the best executed.

Source: DFID key stakeholder interviews and internal documents

Lack of clarity on transition reflects a wider uncertainty as to DFID’s role in middle-income countries

The lack of detailed objectives for transition reflected a wider uncertainty within DFID at the time about its role in middle-income countries. In an earlier period (2005-08), DFID had had an explicit strategy for middle-income countries, focusing on their importance to the achievement of the Millennium Development Goals.38 However, with the decision to concentrate DFID aid mostly in low-income countries, this strategy was allowed to lapse.

The goal of establishing new kinds of development partnership with middle-income countries was articulated in a February 2011 speech by the then International Development Secretary, Andrew Mitchell.39 He called for partnerships based on mutual respect and added value, to tackle global challenges and reduce global poverty.

In response, DFID established an Emerging Powers Team at its headquarters. It also launched the centrally managed Global Development Partnership Programme (up to £50 million per year from 2011 to 2015) as a platform for promoting new global development partnerships, concentrating on the four major emerging powers: Brazil, China, India and South Africa. The programme provided a pool of resources that DFID offices in the four countries could bid for and use to develop working relationships with government, civil society and the private sector. The primary focus was on policy influence. The objectives of the programme were not shared with the four countries.

“There are few, if any, big development challenges that we can hope to tackle without the help of new partners. Polio will never be eradicated without Nigeria’s support. Food security will remain an aspiration without India’s buy-in. We’ll never solve climate change without China. “

The Rt Hon Andrew Mitchell, International Development Secretary, February 2011.

This emerging powers policy agenda appears to have been at odds with the 2011 Bilateral Aid Review and the drive to consolidate aid away from middle-income countries. DFID never prioritised its work with emerging powers to the extent necessary to achieve Andrew Mitchell’s vision. While the Emerging Powers Team provided a small secretariat for the Global Development Partnership Programme, its work was not linked to the development of any further strategy for DFID’s partnerships with middle-income countries. It had no responsibility for guiding or coordinating the transition processes underway in individual countries.

We are informed that the Global Development Partnership Programme was never permitted to utilise all of its funds. It was disbanded in 2016 and responsibility for supporting activities with emerging powers passed to regional divisions, with a reduced funding envelope of up to £20 million per year.

This spending is not reported as bilateral aid to those countries. The Emerging Powers Team has now been merged with the Bilateral Partners Team into a new Development Partners Team within DFID’s International Relations Division, and has no further spending responsibilities. There is currently no central function within DFID for coordinating engagement with middle-income countries or supporting country offices through transition processes.40

In China and India, DFID’s position on post-transition funding was not clearly communicated to the UK public

In all of the case study countries, even where DFID in-country programmes were brought to an end, significant UK aid flows have continued through other channels. These include DFID centrally managed programmes, multilateral aid and aid from other UK government departments. There are various reasons to continue aid funding, including maximising the value of past aid investments (see next section) and working on regional and global issues. However, in the case of China and India, where the UK government made strong public statements around ending aid, in whole or in part, the exact nature of the commitments was not clearly communicated to the UK public.

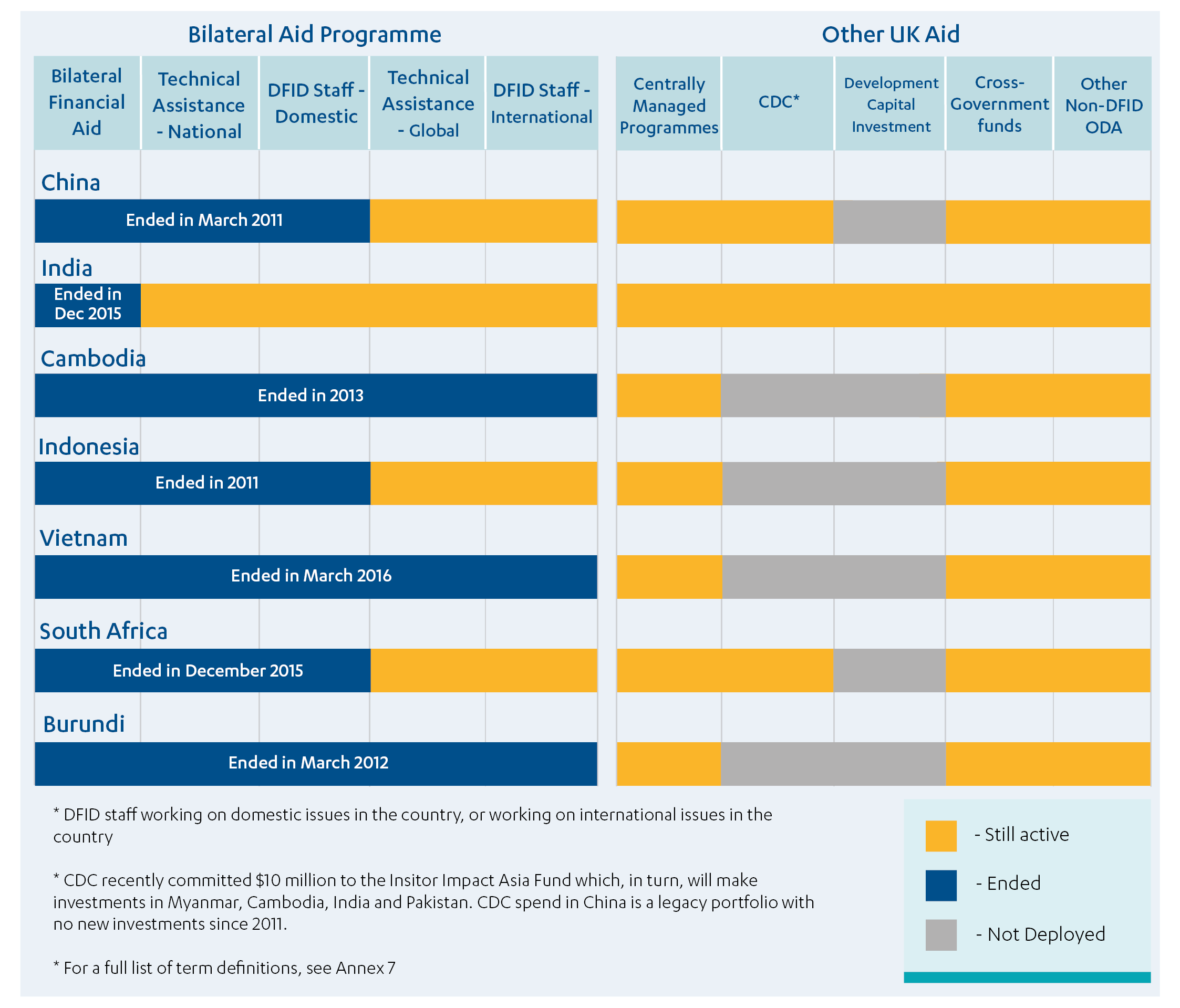

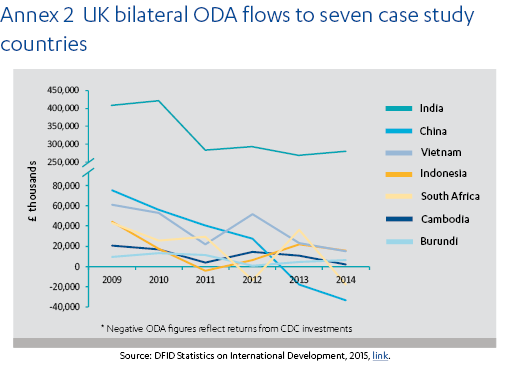

DFID’s funding decisions across the case study countries are summarised in Figure 2, alongside its public commitments in respect of exit from each country (Figure 3).In China, bilateral aid for national development ended, as scheduled, on 31 March 2011. However, DFID has continued to spend £8-10 million per year in China from centrally managed programmes, to support the new partnership on global development issues. Recently, following a change in UK policy, other departments have increased their aid expenditure on Chinese development, most notably through the Prosperity Fund.41

In a press release on 21 October 2015, DFID stated: “DFID no longer provides ODA funding to China or support focused on China’s domestic development.” 42On its project portal, Development Tracker, bilateral aid to China is listed as zero.43 DFID’s official aid statistics also suggest that there is no continuing DFID funding to China, because the published figures on aid per country do not include funds spent by centrally managed programmes.44 While it is true that DFID no longer spends aid on Chinese “domestic development” issues, its continued spending in China is not transparent.

In India, DFID was clear as to its intentions to phase out financial aid, while continuing other forms of assistance. It retained a technical assistance fund of £30 million for 2016-17 so that it could continue to provide advice and technical expertise on national development issues. It plans to spend £40 million in development capital investment45 in 2016-17, which is delivered in the form of loans or equity investments to Indian firms and financial institutions, with a focus on the eight poorest states. The UK’s development finance institution CDC has assets of £756 million in India, which is 26% of its global portfolio.46 India is also a significant recipient of UK multilateral aid through the World Bank, including through the establishment of a new transitional window for concessional lending, for which India qualified as the first, and so far only, recipient.47 India will also be a beneficiary of a substantial Prosperity Fund portfolio.

As shown on the graph in Annex 2, total UK bilateral aid to India fell sharply from a peak of £421 million in 2010 to £283 million in 2011, and then remained at approximately that level for the next four years.

While we do not question the policy decision to continue bilateral support for India, DFID’s public statements emphasised the decision to discontinue financial aid, potentially creating the impression that all aid was being phased out. This lack of clarity was noted by the International Development Committee, which commented that DFID was “diffident about admitting” its continued spending in middle-income countries.48

“We recommend that the UK be confident about its decision to continue its ‘beyond aid’ engagement in middle-income countries. The UK may no longer have a traditional aid relationship with these countries, but it is spending ODA in Brazil, India and China – and is rather diffident about admitting this. We believe the Government should stand up for this course of action, rather than giving its critics opportunities by obfuscating about its perfectly legitimate activities in these countries.”

International Development Committee, January 2015.

Figure 2: Types of aid deployed in seven case study countries

Figure 3: The range of announcements on exit and transition

In most instances, DFID did not prioritise protecting past development gains

One of our review questions was to assess whether DFID took due care, in planning for exit, to protect past development gains and avoid development reversals. There are specific challenges associated with the attainment of middle-income country status and the move to self-financed development. The phasing out of donor funding for basic services and other development programmes also entails a risk of development reversals. We looked to see whether, as it moved towards exit, DFID prioritised building the capacity in partner countries to take forward key development initiatives. We also assessed whether it used its aid funds strategically during the exit process to protect the value of its past investments.

In most cases, we found that this was not a significant part of DFID’s exit planning. As we note below, with a few exceptions, DFID did attempt to exit responsibly by handing over its activities to governments or other development partners, whenever feasible. However, there was little explicit analysis of the risk of development reversals or refocusing of the remaining expenditure to maximise sustainable impact.

Vietnam stands out as an example of good practice, where DFID explicitly analysed the development risks associated with its exit and put in place measures to manage them. It identified areas that it believed were critical to Vietnam’s continuing development (such as anti-corruption, dialogue between government and the private sector and civil society development) and concentrated part of its remaining funding in those areas. In its exit plan, it set itself the goal of exiting responsibly by ensuring that priority issues under DFID leadership were taken forward by others, and made this goal central to its exit planning (see Box 11).

One of the concerns raised most consistently by national stakeholders in China and India was that DFID exited too quickly from the policy arena in its former priority areas. They suggested that small but strategic investments in policy dialogue and technical assistance over the exit period could have yielded important benefits to the partner country, while helping to preserve DFID’s relationships and influence. In China, stakeholders suggested that a continuing DFID voice on national development policy would not only have been welcomed by the Chinese government, but would also have positioned DFID better to engage with China on its global development role, which is strongly influenced by its domestic experience.

In India, DFID has established a technical assistance fund of £101 million for the period 2016-17 to 2019-20. However, the programme was only confirmed late in the transition process, which hampered DFID’s planning and caused a loss of continuity in some activities. The fund is mainly focused on the new economic development agenda; technical assistance for other areas is only allocated £7 million and ends after 2016-17. In South Africa, DFID also maintained a short-term technical assistance fund of £3 million but this will not be ready for implementation until 2017.

We note from the limited literature available that it is rare in any case for donors to prioritise partner country needs during exit.49 Donors often find that their influence with the partner country diminishes rapidly once their intention to exit has been announced. Furthermore, once donors are focused on the exit process, their scope to take on new activities is limited.

The timeline of exit is another constraining factor. Figure 4 shows the timing across the seven case study countries. Vietnam, where the planning was most advanced, had a relatively long exit process of six years. By contrast, South Africa had only two years from the timing of the formal announcement, while in China the formal notice period was only nine months. National stakeholders in most cases expressed the view that exit had taken place too quickly.

Figure 4: Timeline of DFID’s exit and transition decisions

DFID has not consistently addressed the impact of its transitions on civil society

Across the case study countries, DFID has invested many years of support into the development of local civil society organisations that deliver services, represent marginalised groups and engage governments with policy-related advocacy. Alongside its financial support, DFID has helped civil society organisations to gain a seat at the policy table. In India, DFID went one step further, helping to mediate between government and civil society – a role that was appreciated by both sides, according to stakeholders.

Given the scale of DFID’s earlier work with national civil society, we would have expected DFID to help effective former partners secure alternative funding, so that the value of its past investments was not lost. However, most of the stakeholders were of the view that DFID had not gone far enough in assessing and mitigating the costs and risks to civil society caused by its departure.

With the transition of DFID and other donors, civil society organisations faced a double loss: of funding and access (see Box 9). In many of our case study countries (China, India, South Africa, Vietnam and Cambodia), we heard from stakeholders not only in civil society, but also in government and other

development agencies, that DFID’s former civil society partners had been required to scale back their activities on DFID’s departure. They informed us that there had also been an overall closing of the space for civil society to engage on national development issues.

There were positive exceptions. In South Africa, DFID helped regional civil society organisations to access new sources of funding, including from DFID centrally managed programmes. In Indonesia, a successful DFID programme working with civil society on voice and accountability was adapted as a result of transition into a partnership on land use and forestry governance. In this way, DFID was able to maintain a long-term commitment to working with civil society.50

“A key role is played by civil society. Even in those countries that have long been very open, like India and Mexico, we are seeing moves to limit the scope for civil society action. This makes it all the more important to support groups that campaign to safeguard and provide public goods, fight for human rights and push to create more space for independent social and political action.”

German aid agency, 2015.

Box 9: The consequences of transition for civil society

DFID made a concerted effort to support civil society partners through its transition in South Africa and has continued to fund them in Indonesia. However, there were widespread concerns across all the case study countries, and from civil society in the UK, about the impact on civil society. These

concerns focused on three main areas.

1. Loss of funding: Most of DFID’s funding for local civil society in our case study countries came to an end with DFID’s exit. International NGOs such as Oxfam and Action Aid also raised with us their concern that exit from in-country aid to South Africa and India has occurred too quickly, leaving DFID’s civil society partners too little time to find alternative sources of funding.

2. Loss of access: Civil society partners note that DFID’s departure also means the loss of its brokering role between governments and civil society. In the past, DFID was active in convening meetings and hosting public events, helping to impress on partner countries that civil society was a legitimate and important interlocutor. According to stakeholders in civil society, other donors and, in India, government, DFID transition has led to a loss of voice and a closing of the policy space, especially on sensitive issues such as violence against women or ethnic minorities.

3. Loss of protection: In the case of India, DFID support has provided its civil society partners with a measure of protection against attempts to limit their activities. Civil society told us that this protection has been reduced during the transition process. These losses are not an inevitable result of transition. In Indonesia, DFID was able to adapt its civil society partnerships from the period of bilateral aid to the new objective of tackling climate change. Looking further back, when DFID closed two offices in Latin America in the 2000s, it put in place a three-year Latin America Programme Partnership Arrangement to support civil society partners through the transition period. The then Secretary of State, Douglas Alexander, said that “Civil society organisations are at the front line of tackling social exclusion and inequality responsible for the

persistent poverty in Latin America.”51

Source: Stakeholder interviews and written evidence from civil society organisations

Conclusion on relevance

Overall, we have awarded DFID’s approach to exit and transition an amber-red score for relevance. While its focus on exit accorded with UK government priorities, key aspects of its approach to exit were not clearly set out, including its choices of funding instruments during and after exit and what measures could be taken to maximise the value from past development investments. As regards transition, DFID did not clearly articulate what its new development partnerships would consist of. A significant result of this was that DFID failed to communicate its intentions clearly to its partner countries and stakeholders, leading to a lack of clarity in an area of considerable public interest.

How well did DFID manage the exit and transition processes?

Our second review question looks at the effectiveness of DFID’s implementation of the transition to a new development partnership. As exit and transition raise different considerations, we deal with each in turn.

DFID managed the practical challenges of exit effectively

The core business of exit across all seven case study countries was the orderly closing down of aid programmes. DFID implemented this task in a measured and resolute manner. While DFID’s departure was never welcomed by the partner countries, it was done in such a way as to preserve good relations

in five of the cases (the exceptions, India and South Africa, are discussed below).

In each of our case studies, we examined whether DFID had met its objectives around programming, funding, staffing, estates, communications and relationships. For the three cases of exit (Burundi, Cambodia and Vietnam), DFID developed strategies setting out its objectives in these areas. In Vietnam, these objectives were met. According to DFID, both senior and local staff, there was no significant negative reaction to the announcement, and senior Vietnamese officials attended events celebrating the end of a successful aid relationship. Staff morale was maintained and local staff were supported into new jobs. The programmes received good performance scores right up until their closure. Furthermore, DFID commissioned an evaluation of the record of UK aid in Vietnam to ensure that lessons were captured. There was some evidence of regression against past development gains, particularly in the area of HIV/AIDS, where DFID was unable to find other development partners to take over its funding. However, it was clear that DFID actively tried to manage such risks.

In Cambodia, following the closure of its country office, DFID arranged for its remaining programmes to be managed from Vietnam, enabling them to reach a successful conclusion. In Burundi, DFID articulated the twin objectives of “responsible exit” and value for money. There was an effective transfer of responsibilities for certain issues from the bilateral country programme to a regional programme, and the country office was closed to reduce overheads.

DFID honoured existing funding commitments in exiting from aid, with two exceptions

In most of the cases we examined, DFID honoured its existing funding commitments, bringing its programming to an end at the scheduled time with adequate notice to stakeholders. However, this was not the case in a few instances in China and India.

In China, funds not disbursed on 31 March 2011 (the scheduled end date for bilateral aid) were cut. This affected several programmes, including two that were jointly financed with the World Bank on water and sanitation and support through civil society for marginalised groups. The Ministry of Education requested a no-cost time extension in order to maximise learning from its programme. This was denied. DFID was unique among the exiting donors in China in not honouring its commitments. Both the Chinese government and the World Bank expressed their concerns about this decision.

In India, while most programmes were ended responsibly, three programmes of support for academic institutions and civil society organisations were adversely affected in order to meet the overall deadline. In one instance, this meant that a planned evaluation was cancelled at the last minute. DFID did make efforts to find other donors to take forward activities that had been affected, with some

success. However, stakeholders from government and other development partners informed us that the episode had nonetheless harmed DFID’s reputation and relationships.

In most instances, DFID made reasonable efforts to hand over its work to other donors. In Cambodia and Vietnam, DFID successfully identified alternative donors to take forward aspects of its work, although this was complicated by the fact that other donors, such as the Netherlands and Sweden in the case of Vietnam, were exiting over a similar period. In Burundi, as well as working with other donors to secure continuity of funding in key areas, DFID continued its support through the TradeMark East Africa programme.

Staff reductions were efficiently managed, but the right skills were not always available

Staff numbers were reduced in all seven cases, although only three of the country offices (Burundi, Vietnam and Cambodia) were closed completely. In most instances, redundancy of staff appointed in country was handled efficiently, with clear communications and support in identifying new positions.

However, in Cambodia, we heard from former staff that DFID’s central human resource policy meant that UK-based staff 52 were left at risk of redundancy as the office closed. This caused several to leave prematurely, which disrupted the transition process. An independent, DFID-commissioned review of the process commented: “Several of the UK-based staff did not feel valued by DFID… Where UK based staff are expected to commit to remain in post to deliver responsible exit, DFID should consider rewarding this commitment rather than punish them.”53

A key study notes that effective transition requires specialised staff with different competencies.54 DFID’s performance in ensuring that these skills were in place was mixed. In three of the countries (Vietnam, Cambodia and India), DFID created the post of transition manager, but in only one case (Cambodia) did this involve deploying a person with specific skills. In some instances, DFID’s central human resource department assigned a “business partner” to support country offices through the transition. DFID Southern Africa reportedly found this support to be very useful, while DFID Cambodia would have appreciated such support.

In China, the current head of office following the end of bilateral aid had strong previous experience of transition (from Vietnam), but we were told that this was fortuitous rather than planned. In South Africa, where the office was retained to become a central hub for African regional programming, the composition of staff was changed to reflect the new requirements.

In India, the substantive head of office post was vacant for ten months at a critical time in the transition process, due to the reposting of the previous head to manage the Ebola crisis in West Africa. While this step may have been appropriate from DFID’s global perspective, it contributed to a perception among national stakeholders and other donor partners that the relationship with India had been downgraded. National stakeholders strongly emphasised the role that personal relationships play in preserving the “special relationship” between India and the UK. We found no evidence that DFID had identified or attempted to manage this risk.

In Indonesia, all staff except one were changed during the transition. Despite handover briefings, there was a loss of institutional knowledge and relationships with government counterparts. According to key stakeholders, this meant that 18-24 months were lost while new staff established their networks and developed the new programme.

The evidence from our case studies therefore suggests that DFID needs to give more consideration to continuity and to active management of specialised competencies to manage transition and communicate well with partners.

The exit process was marked by communication errors

In five of the seven case study countries, we found that the exit process was marred by significant communication failures, including poor sequencing, inadequate levels of consultation and disruption to agreed communication plans. Only in Vietnam and Indonesia was communication well managed and

appreciated by government.

In South Africa, DFID had agreed with government counterparts on a joint announcement about the closure of the UK aid programme. This was disrupted when the UK made a unilateral announcement, in April 2013. This caused a negative public reaction from the South African government, which accused

the UK of unilaterally “redefining our relationship”.55

The South Africa communications error followed a similar one in India, where an agreed communication plan between the two governments was set aside when the UK government responded unilaterally to critical reporting in the British press of its aid to India.56 This in turn triggered a negative public response from the Indian government.

Beyond this incident, DFID’s new purpose and future directions in India remain unclear to many of the government counterparts, other development partners and civil society members whom we consulted. In our key stakeholder interviews, senior government officials raised explicit concerns about this lack of clarity. According to DFID, efforts have been underway to address this, including senior engagement around Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s UK visit in late 2015, the Royal visit to India in 2016 and the appointment of a new UK High Commissioner. Recently, the new International Development Secretary visited India to signal that “the UK and India are deepening their strategic partnership in areas such as financial services, investment and skills-sharing to benefit both economies”.57

Box 10: Consultation errors in Cambodia

UK bilateral aid to Cambodia was brought to a close in 2013, at the scheduled end of a ten-year Development Partnership Agreement. Despite this, national

stakeholders expressed the view that DFID had not been clear enough about its intentions. This concern was compounded by a consultation exercise held in

2009, after DFID had decided to exit, in which national stakeholders clearly expressed their preference that UK aid continue. This exercise raised expectations that could not be met.