UK aid spending during COVID-19: management of procurement through suppliers

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has led to a major realignment of the UK aid programme for 2020. Between March and September 2020, to meet the urgent health and humanitarian challenges facing developing countries, the UK government allocated nearly £800 million in new aid. At the same time, the impact of COVID-19 on the UK economy resulted in a sharp fall in projected gross national income (GNI), triggering a dramatic reduction in the aid budget to avoid exceeding the 0.7% of GNI spending target. These in-year adjustments had major implications for UK suppliers and multilateral organisations, requiring changes to existing grants and contracts, and to the pipeline of planned procurement.

This is the second ICAI information note that relates to different aspects of the COVID-19 aid response. This information note explores how the UK government – primarily the former Department for International Development (DFID) and Foreign and Commonwealth Office (FCO), before their merger on 2 September 2020 – managed the procurement aspects of the response. We look at the period from 24 January 2020, when the Cabinet Office directed departments to begin preparations for a ‘reasonable worst-case scenario’ in response to the pandemic, until the merger.

ICAI information notes shed light on aspects of UK aid that are of public interest. They are not evaluative in nature, although they may point to issues that would merit further investigation. The information here is drawn from a review of UK government documents and interviews with officials from the new Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO). We also consulted with non-governmental organisations (NGOs) and firms that deliver UK aid programmes.

Box 1: Building on past ICAI reviews

This information note builds on a previous two-part ICAI review of DFID’s procurement, which looked at its management of the supplier market (published November 2017) and its approach to tendering and contract management (published September 2018). It also builds on ICAI’s April 2019 review of DFID’s partnerships with civil society organisations. Across these reviews, we recommended that DFID strengthen its commercial capacity, increase the transparency of its procurement pipeline, improve engagement and communication with suppliers, improve its management of risk and uncertainty, and adopt adaptive contract management techniques that balance accountability with flexibility and innovation. We have found it encouraging that DFID’s response to these past ICAI recommendations strengthened its capacity to respond to the uncertainties of 2020, although with scope for improvement.

The prioritisation process

The COVID-19 pandemic occurred against a background of considerable change in UK aid. The UK’s exit from the European Union, a newly elected government, an impending spending review and a planned Integrated Review of Security, Defence, Development and Foreign Policy all contributed to uncertainty on longer-term priorities. Within DFID, there were changes of both secretary of state and permanent secretary. On 16 June, the prime minister announced the merger of DFID and the FCO. It followed a period of change in DFID procurement, with the department responding to concerns about ethical and other risks within its supply chain and to recommendations made by its ‘supplier review’ and by ICAI (see Box 1). A reconfiguration of the supplier market was under way, with some major suppliers experiencing financial difficulties. COVID-19 itself also caused considerable challenges, with widespread disruption to aid programmes and both UK government and supplier personnel facing travel and other restrictions.

As the scale of the pandemic emerged, the government decided that the UK should focus its efforts to demonstrate leadership in the global response. Coordination was to be provided by an International Ministerial Implementation Group chaired by the foreign secretary. The government directed that the UK aid response should prioritise trusted global institutions, in order to encourage and enable an effective response from the international system. In February, a joint DFID/FCO International Task Force was established and daily COVID-19 updates were provided by a dedicated team of staff. In the second week of February, DFID’s permanent secretary requested weekly reporting on the vulnerability of a range of countries, including major DFID partner countries and FCO priority countries, to the pandemic. This formed a key part of briefings to ministers and the Cabinet Office that continued past September.

By the end of March, following an internal prioritisation process, DFID announced a package of COVID-19 response measures valued at £544 million. By 31 August, a total of £797 million in UK aid had been committed to the global response, mostly from DFID (£772 million). The majority was directed through multilateral partners, including the World Health Organisation, UNICEF, the UN High Commissioner for Refugees, the World Food Programme and the Red Cross. A substantial amount also went to support scientific research, with the largest single investment (£250 million) going to the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations (CEPI), for vaccine development.

Box 2: The Rapid Response Facility

One tool DFID used was the Rapid Response Facility (RRF), a mechanism designed to fund emergency programming in response to humanitarian crises. On 7 April, DFID asked NGOs to submit proposals for funding through the RRF. Seventy-four proposals were submitted by the 15 April deadline. DFID selected seven, with a combined funding total of £18 million. UK NGOs told us that they thought this was a small allocation relative to other channels. NGOs also said that they would have appreciated more transparency around the funding available.

The prioritisation of UK aid was done in two phases. The first was DFID’s response to a Cabinet Office direction issued to every government department to prioritise their work around COVID-19. On 24 March, DFID’s acting permanent secretary tasked all business units to prioritise their operations around a three-tier classification: Gold (‘drive’), Silver (‘manage’) and Bronze (‘pause’). They were told that the highest priority level should include the COVID-19 response, ongoing humanitarian operations and the preparation of certain high-profile international events. The ‘silver’ category included other manifesto commitments, key country priorities, work with the multilateral banks and the UK’s development finance institution, CDC, and essential business processes, such as safeguarding and preparing for the spending review. All other programming, policy or international influencing that did not contribute to the immediate social or economic welfare of people in COVID-19-affected countries fell into the ‘bronze’ category. Over the period from March to May, business units were asked to classify their operations accordingly and identify expenditure that could be cut or postponed. New contracting with suppliers was put on hold unless it received ministerial approval.

As the scale of the impact on the UK economy emerged, the prime minister asked the foreign secretary to lead a cross-government review of the aid budget, in order to avoid exceeding the 0.7% of GNI spending target. The legislation does not state that the target is also a ceiling, but it has been UK government practice to hit the target as precisely as possible. As a result of this exercise, aid-spending departments were directed to identify large cuts, with DFID initially undertaking to look for £3.5 billion in reductions by the end of 2020. A second DFID prioritisation process therefore began in early June. It was not a consultative exercise. An initial set of priorities was drawn up by ministers, with the highest priority given to COVID-19-related interventions (including through health interventions, humanitarian assistance, social protection and support for food production and supply), followed by other manifesto commitments (education, ending preventable deaths, climate response, economic development, and avoiding human rights and security crises).

DFID used Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) sector codes (a classification of aid by sector used for international aid statistics) to initially allocate programmes to ministerial priorities. This was quality-assured and programmes were ranked according to the priorities. For each one, officials made a recommendation as to whether to close the programme in whole or in part, pause or reprofile expenditure, postpone activities, continue as planned or scale up, where the programme was considered integral to the COVID-19 response. These recommendations were aggregated and considered in three ‘Star Chamber’ meetings in June and July, alongside recommendations from all aid-spending departments including the FCO, involving ministers from all aid-spending departments and HM Treasury. A cross-government package of £2.9 billion in-year cuts was signed off by the prime minister on 20 July. The full extent of the cuts required will not be known until the end of the year, and will be the subject of a supplementary ICAI review of how the 0.7% spending target was managed in 2020. This was late in the year to implement cuts on such a scale, and required DFID programme managers to work intensively with suppliers. The government has not made public the full rationale applied in its two aid prioritisation exercises.

Lines of enquiry:

- How were programme performance and value for money factored into the prioritisation?

- Did decisions on which programmes to cut take account of the needs and vulnerabilities of recipient

countries and populations? - How have interruptions to ongoing aid programmes impacted recipient communities and what should

FCDO do to minimise this?

The management of procurement

DFID recognised from the outset that the prioritisation process would have a major impact on suppliers. The cancellation or postponement of ongoing programmes and the pause on new procurement could cause financial difficulties, particularly for small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), which DFID had been working for some years to bring into its supply chain. While suppliers are not the intended beneficiaries of UK aid, it is good procurement policy – and UK government policy – for departments to look after their supplier market. A healthy pool of suppliers offers more capacity, competition and diversity, leading to better procurement outcomes and greater value for money.

From March 2020, DFID began monitoring the impacts of the prioritisation, and of COVID-19 more broadly, on its supply chain, and assessing possible mitigation measures. In this section, we explore those impacts and how well they were managed across DFID and FCO.

A lack of transparency and communication around the prioritisation increased the uncertainty facing suppliers

During the period from late May to August, government officials were instructed not to provide any information to suppliers, either about the prioritisation process or the implications for individual programmes. The existence of a prioritisation process was not a matter of public record until the chair of the International Development Committee, Sarah Champion MP, wrote to the DFID secretary of state on 5 June asking for details. The process was confirmed in a 25 June reply.

This lengthy period without communication was frustrating and caused uncertainty. We heard of cases where officials knew that particular programmes were unlikely to continue, but could not respond to requests for information until the entire package of cuts had been approved. We also heard of cases where officials in country had discussed plans with suppliers early in the summer, but had to wait for final confirmation for implementation months later. This added uncertainty to the disruption that suppliers were already facing to their operations as a result of pandemic-related travel restrictions. Many organisations expressed a view that it was the lack of transparency that hampered their ability to plan effectively. The delay in reaching final decisions made them harder to implement, and made the required cuts deeper and more abrupt. Early communication about the nature of the process and its potential implications would have given suppliers more ability to plan. Indeed, this would have been more consistent with the government’s Procurement Policy Note 04/20, issued in June, which stated that departments should “work in partnership with their suppliers, openly and pragmatically, during this transition”.

Nonetheless, both DFID and the FCO made efforts to step up oversight of and engagement with suppliers. DFID posted various notices on its supplier platform, although this is primarily for information about commercial contracts and is not used by all NGOs. DFID also created dedicated email accounts for supplier enquiries. Both departments held open meetings with suppliers in April, and regular forums were held with representative bodies such as British Expertise International, Humentum and Bond. Separate meetings were at times held with SME suppliers. DFID instituted a supplier survey, initially weekly, and developed a ‘heatmap’ for monitoring impact on supplier operations by country, to complement operational information collected by programme managers. Specialist staff within DFID’s Compliance and Risk team carried out financial monitoring of at-risk private supply partners, while the FCO procurement team used external monitoring services such as Company Watch and Dun & Bradstreet.

However, while a range of communication channels were established, suppliers told us that the flow of information was primarily one-way, from suppliers into government. Both private and NGO suppliers noted that the weekly survey set up by DFID was time-consuming and extractive, and that they were not informed of how the information collected was used. Similarly, we heard a consistent set of views that the responses to questions raised by suppliers were inadequate, although there was a general understanding that officials themselves simply did not have the answer in many cases as they were waiting for decisions from those in authority.

The majority of cuts did not affect suppliers

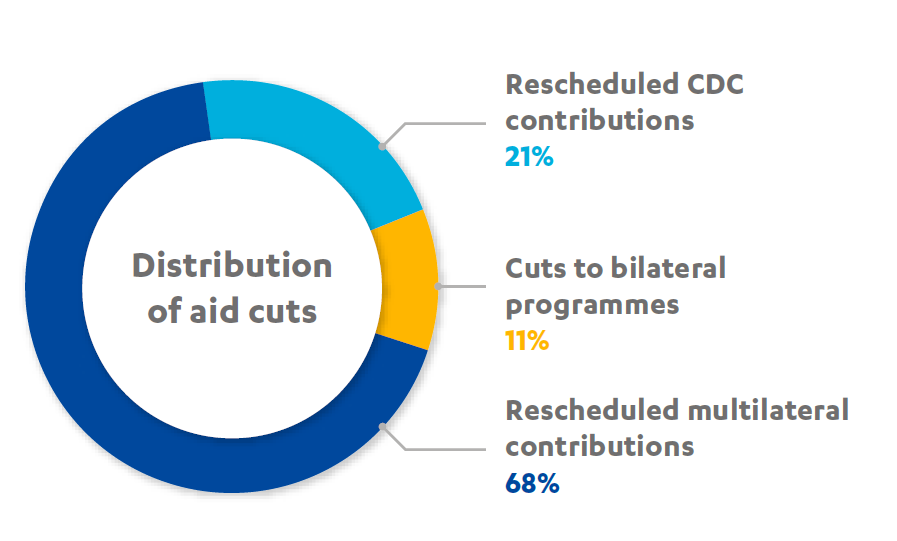

Our evidence shows that the government took the decision that the majority of the cuts should not fall on aid programmes delivered by suppliers. Most of the cuts involved rescheduling multilateral contributions and postponing planned capital contributions to CDC. Private sector and NGO suppliers were therefore affected by only 11% of the cuts (see Figure 1), even though they delivered 22% of DFID’s budget as of January 2020.

Figure 1: Distribution of aid cuts by category

Box 3: Procurement of personal protective equipment (PPE)

At the onset of the pandemic the UK, like other countries, faced shortages in PPE and key medical equipment such as ventilators. Across the UK, government approval for the purchase of such equipment was centralised under the Department of Health and Social Care (DHSC). A small stock of PPE (worth £55,000) was procured in the early stages of the response, with DHSC approval, to support humanitarian operations. PPE supplies were sent to British Overseas Territories to respond to COVID-19 and to prepare for hurricane season, using funding from the Conflict, Stability and Security Fund (which is 20% funded by official development assistance (ODA)). As shortages within the UK became more acute, for a time DFID staff were instructed not to procure COVID-19-related medical supplies directly, to avoid any competition or a perception of competition with the UK’s own needs. Instead partner countries were advised to work with the World Health Organisation and other agencies to secure supplies. This aligned with a common position taken by all the OECD donors, other than the US, to channel large-scale purchase of medical equipment and supplies for developing countries through the multilateral system.

Past procurement reforms had left DFID better placed to respond to the disruption

In the years before the pandemic, DFID’s Procurement and Commercial Department had implemented a significant programme of commercial reforms, prompted by the internal October 2017 supplier review and ICAI’s two procurement reviews. By 2020, the department had more specialist commercial posts at its disposal and a deeper understanding of its supplier market. In early 2018, it had launched a Strategic Relationship Management programme with major suppliers, and introduced a number of new tools to manage risks in the supply chain, including increased oversight of compliance with its supplier code of conduct and monitoring the financial health of suppliers. This meant that, when the pandemic hit, DFID already had a risk-based and adaptive commercial strategy that emphasised effective relationships with key suppliers and ensured a better understanding of their financial health.

While the FCO did not have an equivalently resourced procurement and commercial function, it had also taken steps to build its capacity, recruiting commercial specialists. Measures had also been introduced across the UK government just before the pandemic to strengthen business continuity planning. Both departments had relatively strong IT systems and distributed work practices in place that enabled them to continue their operations with relatively few interruptions, despite the withdrawal of in-country staff.

Overall, there is good evidence that improvements in DFID and FCO capacity in recent years left both departments much better placed to manage the disruption of the pandemic. However, it was also apparent that the departments’ approach to oversight of their supply chain varied depending on whether funds were provided through contracts or as grants (the latter going to NGOs, the former to both private and NGO providers). Some functions, such as undertaking financial due diligence of individual NGO suppliers, had been outsourced to private companies overseeing the delivery of particular grant mechanisms. NGOs and DFID staff told us that the measures taken to increase the number and skills of staff and the tools available for managing private sector suppliers had not been matched by a strengthening of DFID’s resources for managing relationships with its NGO partners.

Lines of enquiry:

Drawing on lessons from how DFID improved its oversight and relationship management with commercial suppliers, how could FCDO strengthen its engagement with NGOs and other not-for-profit suppliers?

The departments adjusted their risk management in response to the pandemic

As the disruptive effects of the pandemic became apparent, both DFID and the FCO recognised a need to adjust their approach to risk management. There were changes to procurement and contract management processes. Government guidance issued on 13 March authorised accelerated procurement in response to the pandemic, allowing for direct awards of contracts in urgent cases and shortening the timescales for competitive procurement. It also gave procuring authorities the right to extend or modify existing contracts, although in practice this flexibility already existed in most aid-related contracts.

The departments also recognised the need for increased tolerance of risks to the successful delivery of programmes, given the disruption to aid delivery occurring in the field. However, the priority given to monitoring risks relating to safeguarding (protection of recipient communities from sexual exploitation and abuse) or fraud and corruption was not relaxed. In fact, scrutiny in these areas was increased: the Cabinet Office recognised that fraud risk would increase in times of emergency and issued guidance to departments on how to strengthen risk management. Both DFID and the FCO responded by enhancing their internal risk registers.

The National Audit Office has published a review of the processes used across government for COVID-19 procurement. It highlighted examples of lack of competition and poor documentation in procurement by several domestic departments, particularly in relation to direct awards of contracts. We did not see similar problems with aid-funded procurement. While the COVID-19 response has required large increases in domestic spending, aid-spending has decreased significantly this year. We noted one aid-funded contract awarded directly, which is described below in Box 4.

Box 4: Direct award to Unilever for the Hygiene & Behaviour Change Coalition

In March, ministers approved a direct award of £50 million to Unilever, to be matched by the private sector with a similar sum, for a programme focusing on hygiene, handwashing and behaviour change. Under Unilever leadership, academic institutions such as the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine and NGO partners (principally those participating in the COVID-19 Hygiene Hub) were funded to develop communication and behaviour change programmes and distribute over 20 million hygiene products. Although the UK government’s funds were provided as a direct award to Unilever, the coalition appears to have allocated some of these funds competitively to delivery partners.

Decentralised decisions were supported by central teams

The prioritisation process called for rapid adjustments to contracts and grants across multiple locations. Both DFID and the FCO demonstrated a good level of flexibility in determining the best approach in each case. This flexibility was enabled by two factors. First, DFID had a decentralised contract management process, with programme management teams making day-to-day decisions, under the responsibility of a senior responsible owner (SRO). Second, both departments put in place central teams and processes to coordinate the response, support SROs and ensure consistency. DFID issued new guidance, lightened administrative requirements and instituted accelerated processing of contract amendments. DFID’s Better Delivery Department supported programme teams with applying the new guidance. The Procurement and Commercial Department within DFID established a COVID-19 response group, which met daily to monitor the supply chain and liaised closely with the DFID corporate COVID-19 team. DFID’s Procurement Steering Board also met daily, to approve key procurement decisions and contract variations. The process was less elaborate in the FCO, as the number of contracts was smaller, but followed a similar pattern. Cross-departmental coordination of ODA procurement was strengthened, with regular meetings of procurement specialists from all aid-spending departments to share information on the health of the supply chain and of individual suppliers.

There is no doubt that this was a very demanding period: staff from both former departments told us that they faced major challenges around ensuring consistency of approach, staying up to date with a rapidly evolving picture and keeping up with the pace of action required. Suppliers and NGOs provided some examples of inconsistencies around the application of the new guidance between different country offices and teams (particularly SROs’ understanding of their delegated authority and how much information they could share with suppliers). This was in contrast to the DFID and FCO view that there was uniformity of application across both organisations. We nonetheless found that both departments were generally able to approve contract variations within a few days, which contributed significantly to a flexible response to the pandemic.

While the supplier relief scheme was not utilised, the departments found ways to help suppliers manage disruption to their programmes

In March, the Cabinet Office announced the establishment of a supplier relief scheme, whereby suppliers at risk of financial distress could request an advance of up to 25% of contract value. The guidance anticipated that the majority of UK government suppliers would qualify as ‘at risk’. To qualify, suppliers had to use ‘open book’ accounting, to ensure financial transparency, and could not simultaneously claim other government support for the same event, such as payments to staff furloughed under the Coronavirus Job Relief Scheme. DFID and the FCO announced they had adopted supplier relief programmes on 1 May, following Cabinet Office and HM Treasury clarification that the support could also be extended to non-UK suppliers. For DFID, the detailed eligibility criteria included: level of dependence on UK government contracts, potential impact on the aid programme of the supplier’s failure, its financial stability and cash flow, the strategic importance of its programmes, and potential risks to the recipients of UK aid.

In practice, no supplier relief was ever granted. DFID received 14 approaches for supplier relief that led to six formal applications, including from some on its list of 41 strategic suppliers, and the FCO also received several applications. This was far fewer than anticipated. Some suppliers told us they had made use of the furlough scheme and/or other government support instead.

Rather than granting financial relief, the departments found they were able to accommodate supplier needs by adjusting commitments in their contracts relating to activities, outputs, timescales or ways of working (known as ‘performance relief’). This approach was valued by suppliers. Some NGOs commented that ‘no cost’ extensions of their delivery timescales provided immediate relief but meant that they may incur unrecoverable additional costs in the future. Suppliers were also able to claim back sunk costs for discontinued activities. The suppliers we interviewed appreciated the move to monthly invoicing and the opportunity to convert output-based payments (payment by results) into input-based payments, which helped with cash flow.

Results

We were presented with evidence that improvements made to procurement and commercial capacity in the UK aid programme in recent years left the responsible departments better placed to minimise the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on their supply chain. The departments recalibrated their risk management processes and worked flexibly with suppliers to minimise disruption. However, their efforts were hampered by a slow process for approving the aid cuts and an inability to share information with suppliers during the prioritisation process.

It is too early to assess the long-term development impact of UK government decisions on the prioritisation of the 2020 aid programme. The government decided in August that the bulk of the cuts (89%) should take the form of deferred payments to multilateral organisations and CDC. These institutions are better placed to minimise disruption to their operations from delayed payments than UK aid programmes delivered by suppliers. However, this decision may have longer-term implications, including potentially a reduced budget for other activities in 2021.

Of the £253 million in cuts from bilateral aid projects, some were achieved by delaying payments, reflecting the fact that delivery schedules had already been disrupted by the pandemic. However, it is inevitable that cuts on such a scale at short notice may have had long-term development impacts, which will only become clear over time.

From a procurement perspective, contrary to expectations at the onset of the pandemic, none of the private or NGO suppliers on the UK aid programme have yet been forced to cease operations, which is a substantial achievement. While some suppliers are likely to face continuing financial difficulties in the coming 12 months, the emergency measures implemented by DFID and the FCO, together with the suppliers’ own actions and, in the case of NGOs, private fundraising, have reduced major disruption to the supplier market.

Lines of enquiry:

While this information note was not intended to reach evaluative judgments, it has identified a range of issues that would merit future scrutiny, whether by the International Development Committee, the National Audit Office or ICAI itself. With disruptions to the aid programme likely to continue into 2021, these are also important areas where FCDO can draw lessons.

- How were programme performance and value for money factored into the prioritisation?

- Did decisions on which programmes to cut take account of the needs and vulnerabilities of recipient countries and populations?

- How have interruptions to ongoing aid programmes impacted recipient communities and what should FCDO do to minimise this?

- Drawing on lessons from DFID’s oversight and relationship management with commercial suppliers, how could FCDO strengthen its engagement with NGOs and other not-for-profit suppliers?