The UK aid response to global health threats

ICAI score

A relevant and coherent strategy for responding to global health threats. There is good potential for programmes to be effective, particularly if better integrated with health systems strengthening, but the approach to building learning and sharing knowledge is weak.

The UK government responded rapidly to weaknesses in the international response system exposed by the Ebola crisis, developing a coherent and evidence-based framework for addressing global health threats and establishing a portfolio of relevant and often pioneering programmes and influencing activities.

The portfolio shows strong potential to be effective, particularly on influencing WHO reform, building surveillance systems in high-risk countries, developing new vaccines and supporting a timely response to contain new outbreaks. Cross-government mechanisms for sharing global health threats data and deciding how to respond also show signs of promise.

Building on this strong foundation, there is an opportunity for DFID, the Department of Health and other relevant bodies to do even better. There is a need to update the global health threats strategy and communicate it more widely. There should be better coordination across centrally managed programmes and with DFID country offices and there should be a greater emphasis on strengthening country health systems across all programming.

The government’s approach to generating and sharing evidence on what works is weak. Improvements are needed to secure what has been achieved to date and to support the effectiveness and value for money of future efforts to tackle global health threats.

| Individual question scores | |

|---|---|

| Question 1 Relevance: Does the UK have a coherent strategy for using aid to address global health threats? |  |

| Question 2 Effectiveness: Is the emerging aid portfolio a potentially effective response to global health threats? |  |

| Question 3 Learning: Is learning informing the continuing development of the UK aid response to global health threats? |  |

Executive Summary

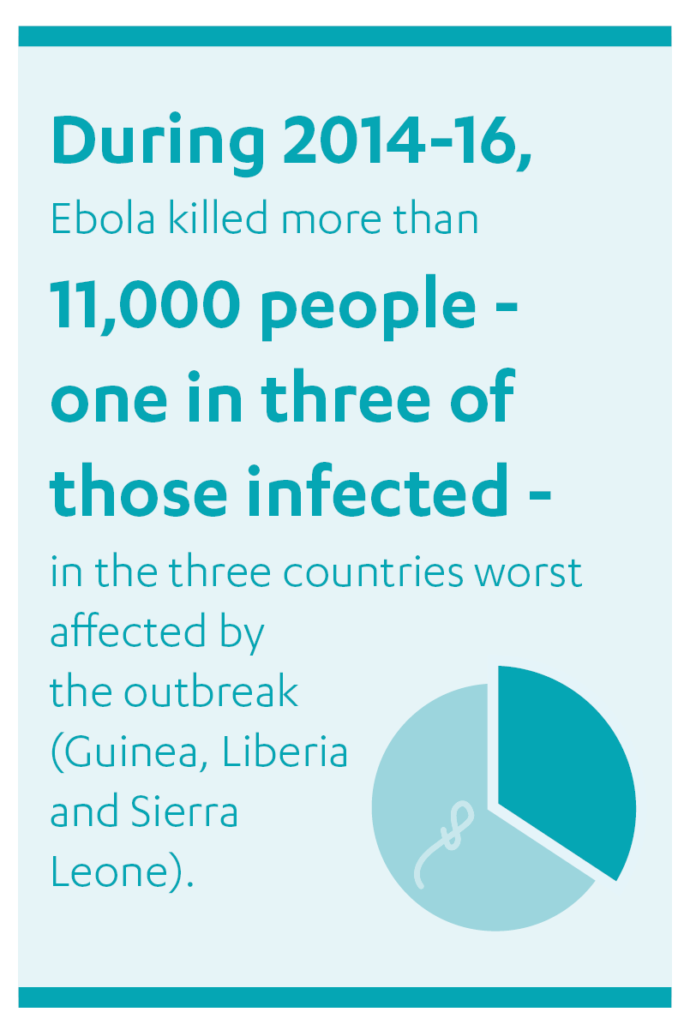

The Ebola crisis from 2014 to 2016, which killed more than 11,000 people, brought a new level of urgency to the issue of global health threats – infectious disease outbreaks and drug resistance with the potential to spread across borders. The Ebola outbreak led to a protracted humanitarian emergency and severe developmental setbacks in Guinea, Liberia and Sierra Leone, and spread panic and disruption to trade and travel far beyond West Africa. It exposed weaknesses in epidemic preparedness and response, and highlighted failings within the World Health Organization (WHO) and across the international health emergency response system. The crisis also demonstrated the fundamental challenge of responding effectively to global health threats in countries with weak national health systems.

While health has been a major focus of UK aid for many years, the response to and lessons from the Ebola crisis stimulated a rapid scaling up of activity and spending to address global health threats. An additional £477 million was allocated to the Department of Health in the spending period 2016-21 to support this activity, while the Department for International Development (DFID) has also scaled up its efforts. The government’s aim is to reduce the risk of future outbreaks, to support countries and the international community to better prepare for them, and to improve the international response when outbreaks occur.

In this learning review, we gauge how successful this rapid scaling up of aid activity has been. We look at how the UK government has developed a strategy and a portfolio of programmes on global health threats, building in particular on the lessons learnt from the Ebola outbreak. We assess how effectively it has implemented this strategy, and how it is using learning to inform future activity. Throughout the review, we consider how evidence, knowledge generation and learning have been translated into strategy, programming and global influencing. For the purpose of this review, we understand global health threats to include infectious disease epidemics that risk spreading across borders and emerging diseases with epidemic potential, as well as the threat posed by drug-resistant microbes. This is in line with the priorities of the 2015 UK aid strategy.

The scope of our review is broad, reflecting the range of activities developed by the government as part of the UK aid response to global health threats. Given the cross-government nature of this response, the review looks specifically at the effectiveness of collaboration between the different departments and agencies involved.

Relevance: Does the UK have a coherent strategy for using aid to address global health threats?

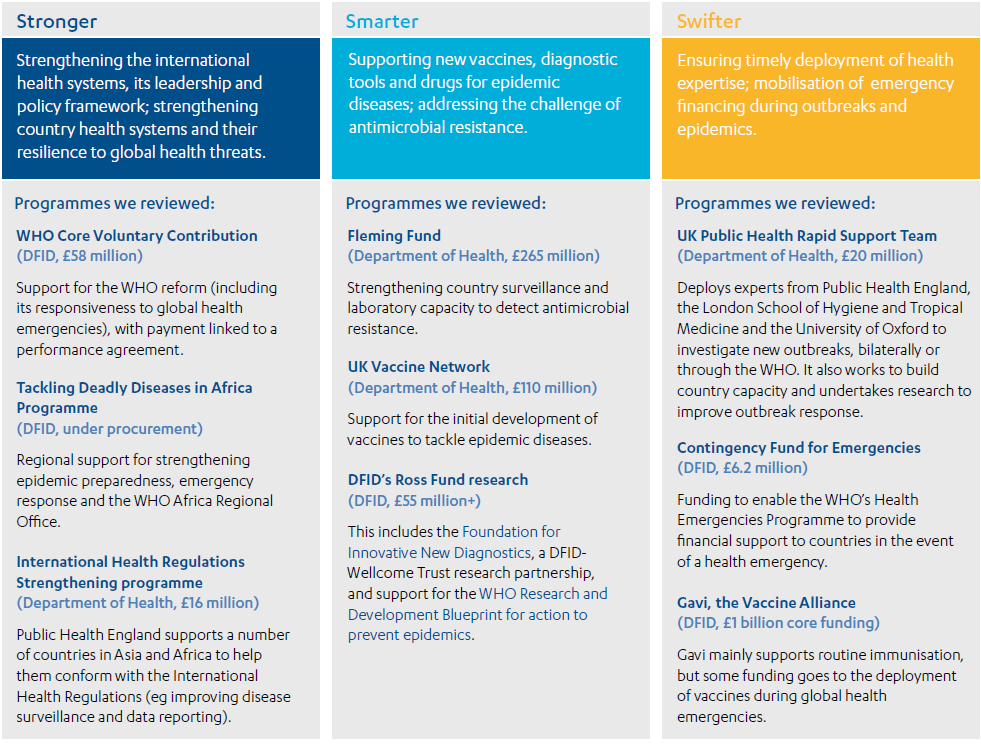

As the Ebola crisis unfolded, the UK government moved quickly to diagnose the challenges and failings in global health threats preparedness. The Department of Health and DFID drew on this evidence base and responded with a shared strategic framework, Stronger, Smarter, Swifter, underpinning a portfolio of programmes and interventions. The framework was focused on stronger health systems, smarter development of new vaccines, diagnostic tools and detection of drug resistance, and swifter response to outbreaks and epidemics. We found that the strategy provided a relevant and well-balanced framework for action, and each of the major global health threats programmes we reviewed was supported by a strong strategic rationale.

This strategic framework has provided a strong foundation for the government’s programming on global health threats since 2015. We nevertheless found room for improvement. The framework could provide greater clarity on the roles of different government departments, and on the cross-cutting importance of health systems strengthening. The strategy could also articulate a broader range of research priorities, beyond vaccine and product development. At country level, the degree to which DFID country offices have prioritised global health threats objectives has been mixed. Meanwhile, centrally managed global health security interventions (including those focused on antimicrobial resistance) would benefit from a more explicit cross-programme focus on health systems strengthening, since robust national health systems are critical to the task of detecting, responding to and containing global health threats.

Stronger, Smarter, Swifter was intended primarily for internal use and has not been published. With a number of donors and multilateral agencies entering or scaling up their activity in this area, we see an increasing need for the UK government to communicate and promote its strategy more clearly in order to help and encourage other donors and investors to align their activities and spending with the UK’s efforts.

Overall, we have awarded the UK government’s global health threats strategy a green-amber score for relevance. This recognises the considerable achievement in the wake of the Ebola crisis of developing a coherent framework for addressing global health threats, backed by strong evidence of need, as well as a relevant portfolio of programmes and influencing activities. However, there is a need to build greater linkages between the government’s global health threats work and strengthening national health systems. And also to clarify and improve cross-government ways of working, and to disseminate the strategy externally.

Effectiveness: Is the emerging aid portfolio a potentially effective response to global health threats?

The UK has a portfolio of potentially impactful programmes. Programmes managed centrally by both DFID and the Department of Health have made positive progress to date. DFID’s country health programmes are generally contributing to strengthening the disease surveillance mechanisms of country health systems and improving the resilience of health systems to future disease outbreaks.

Overall, the UK has shown international leadership on global health threats. It has been influential in encouraging the WHO to reform and securing global policy commitments on antimicrobial resistance. The Department of Health and DFID have collaborated effectively to promote improved international data gathering and assessment mechanisms during disease outbreaks.

There remain areas for improvement. The UK’s influencing strategy has had little success in encouraging other donors to invest in the WHO Health Emergencies Programme. At country level, global health security programmes could do more to support comprehensive health systems strengthening, working closely with partner governments to ensure that interventions to tackle specific diseases and health issues also contribute to the quality and robustness of national health systems. Other ODA-funded global health research has yet to be fully aligned with the global health threats agenda, missing opportunities to encourage joined-up medical and social science research responses.

There is a general need for improvements in cross-government collaboration and communication. At the strategic level, we found that oversight mechanisms could provide stronger leadership and coordination to all government departments with global health security programmes and expertise. At the programme level,

country offices and centrally managed programmes need better coordination, and country offices would benefit from increased capacity to coordinate UK aid-funded interventions and influencing activities.

Overall, we have awarded a green-amber score for effectiveness. This recognises that the global health security portfolio shows strong potential to be effective.

Learning: Is learning informing the continuing development of the UK aid response to global health threats?

Having been quick to capture lessons from the Ebola crisis and build these into its Stronger, Smarter, Swifter strategic framework, the UK government has not followed through with sufficiently robust evaluation and knowledge dissemination practices.

A variety of UK government and external stakeholders we talked to commented on the need to improve learning and knowledge sharing. With some exceptions, mechanisms to evaluate programmes and to share learning are inconsistent or underdeveloped. We found evidence of some good monitoring and learning practices within individual programmes, but not enough dissemination of lessons beyond the programmes generating them, or between government departments. In the country programmes we reviewed, we saw little evidence that lessons were shared more widely. We also found that there is currently no overarching evaluation and learning strategy to support the Stronger, Smarter, Swifter framework.

We have given the government an amber-red score on learning, noting that improvements are needed to build on the achievements to date and to support the effectiveness and value for money of future efforts to tackle global health threats.

Conclusions and recommendations

We have given the UK government an overall score of green-amber for its aid effort to tackle global health threats since the Ebola outbreak. The government has made good progress in developing a coherent framework for addressing the risks from infectious disease outbreaks and drug resistance, as well as rapidly establishing a relevant portfolio of programmes and influencing activities. Nevertheless, our review highlighted some gaps and a number of opportunities for improvements.

The following recommendations are intended to help the government, and the Department of Health and DFID in particular, to further improve its strategy and interventions.

Recommendation 1

The UK government should build on the success of the Stronger, Smarter, Swifter framework by developing a refreshed global health security strategy with a clearer focus on strengthening country health systems, a broader set of research priorities and clearly defined mechanisms for collaboration both across departments and with external actors. The strategy should be published and communicated widely.

Recommendation 2

The Department of Health and DFID should strengthen and formalise cross-government partnership and coordination mechanisms for global health threats, broadening their membership where relevant. This should include regular cross-government simulations to rehearse how the UK government might coordinate and respond internationally to a future global health threats crisis similar to Ebola, and engage with other actors such as the WHO.

Recommendation 3

The government should ensure that DFID has sufficient capacity in place to coordinate UK global health security programmes and influencing activities in priority countries, including around the objective of strengthening national health systems.

Recommendation 4

DFID and the Department of Health should work together to prioritise learning on global health threats across government, overseeing the development of a broad evaluation and learning framework, regular reviews of what works (and represents good value for money) across the portfolio, and a shared approach to the training and development of health advisors.

Introduction

Purpose

Global health threats are of increasing concern to the international community and to the UK government. Infectious disease outbreaks and drug resistance, with the potential to spread across borders, feature prominently in the UK aid strategy and the National Security Strategy and Strategic Defence and Security Review, both published in 2015.

Global health threats present a direct challenge to the overarching aims of the government’s aid strategy: to support international development while at the same time protecting the UK’s national interest. Certain diseases with epidemic potential, such as Ebola, influenza, severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) and Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS), are a threat not just to affected countries but also to the international community due to their high fatality rate, the risk that they will spread internationally and their potential to cause panic, disruption and disorder.

The 2014-16 Ebola crisis in West Africa saw borders closed and severe disruption to international trade and travel. The World Health Organization (WHO) declared the outbreak a Public Health Emergency of International Concern. By the time it lifted this designation in March 2016, Ebola had killed more than 11,000 people – one in every three people infected – in the three countries worst affected by the outbreak (Guinea, Liberia and Sierra Leone).

The emergency led to a protracted humanitarian crisis. It also had a severe developmental impact in these countries. It placed already weak health systems under extreme pressure, leading to an initial failure to contain the outbreak. GDP growth collapsed, while consumption, employment and school attendance rates fell. The World Bank estimates that the Ebola outbreak cost the economies of Guinea, Liberia and Sierra Leone, already among the world’s poorest, at least US$2.8 billion in lost growth.

Box 1: How this report relates to the Sustainable Development Goals

The Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), otherwise known as the Global Goals, are a universal call to

action to end poverty, protect the planet and ensure that all people enjoy peace and prosperity

Related to this review

![]()

Ensure healthy lives and promote well-being for all at all ages

SDG3 sets out to end the epidemics of AIDS, tuberculosis, malaria and other communicable diseases by 2030. Crucial to achieving this goal is to strengthen national health systems and provide quality treatment for everyone, including the poorest and most vulnerable in society. Better quality health systems also strengthen countries’ capacity for early detection and warning, and improve their ability to contain and manage outbreaks. Research and development of new vaccines, and the provision of these and good quality medicines at affordable prices, is also central to SDG3.

Combating global health threats is recognised as central to achieving the SDGs. As our description of the Ebola crisis in this review makes clear, health emergencies do not only have health impacts. They affect a range of SDGs, from health to education and jobs, economic growth and poverty alleviation.

While health has been a major focus of UK aid for many years, the response to and lessons learnt from the Ebola crisis prompted a rapid scaling up of activity to address a range of global health threats. An additional £477 million was allocated to the Department of Health to support this activity in the spending review period 2016-21. The Department for International Development (DFID) also scaled up its activity on global health threats,

developing new strategies and programmes, refocusing some of its existing spending and ramping up its global influencing and advocacy work.

The government’s objectives, summarised in the UK aid strategy, are to:

- reduce the risk of future outbreaks

- support countries and the international community to better prepare for outbreaks

- improve the international response when outbreaks occur.

Since this is a relatively new policy area, with a rapid scaling up of investments, we decided to conduct a learning review (see Box 2) of how the UK government developed its framework and portfolio of programmes on global health threats, how it has implemented this strategy and how it is using learning to inform future activity. Throughout the review, we consider how evidence, knowledge generation and learning have been translated into strategy, programming and global influencing activities.

Box 2: What is an ICAI learning review?

ICAI learning reviews examine new or recent challenges for the UK aid programme. They focus on knowledge generation and the translation of learning into credible programming. Learning reviews do not attempt to assess impact. They offer a critical assessment of progress to date and whether programmes have the potential to produce transformative results. Our learning reviews recognise that the generation and use of evidence are central to delivering development impact.

Other types of ICAI reviews include impact reviews, which examine results claims made for UK aid to assess their credibility and their significance for the intended beneficiaries, performance reviews, which examine effectiveness and value for money, and rapid reviews, which represent short, real-time reviews of emerging issues or areas of UK aid spending of particular interest to the UK Parliament and the public.

Scope

The UK’s response to the growing risk of global health threats has been wide-ranging. Two departments, DFID and the Department of Health, have taken the lead, but other departments and agencies, including the Cabinet Office and Public Health England, have also had important roles. Our scope covers the totality of the UK aid response to global health threats, regardless of the spending department.

In line with the UK aid strategy, we understand global health threats to include infectious disease epidemics that risk spreading across borders and emerging diseases with epidemic potential, as well as the threat posed by drug-resistant microbes (often referred to as the challenge of antimicrobial resistance). Some definitions of global health threats include the accidental or deliberate release of diseases, chemical and nuclear hazards, and non-communicable diseases. However, these are outside the scope of our review.

Within this focus on epidemic threats and antimicrobial resistance, our review explores the UK’s support for emergency preparedness and response. This includes the government’s contribution to influencing and strengthening international systems for health surveillance and crisis response, such as the International Health Regulations (see Box 4). In addition, the review explores how new areas of emphasis in addressing global health threats are balanced with the longer-term process of strengthening the national health systems of developing countries.

The questions guiding our review are outlined in Table 1.

Table 1: Our review questions

| Review criteria and questions | Sub-questions |

|---|---|

| 1. Relevance: Does the UK have a coherent strategy for using aid to address global health threats? | • Are investments prioritised according to the emerging evidence and assessments of the health risks to partner countries and the UK? • Do UK aid investments follow a coherent strategy or approach? |

| 2. Effectiveness: Is the emerging aid portfolio a potentially effective response to global health threats? | • Is UK aid providing effective support for the strengthening of international systems of prevention and management of global health threats? • Is UK aid providing effective support for the building of national health systems preparedness for global health threats? • Is there effective joint working and coordination across the UK government? |

| 3. Learning: Is learning effectively informing the aid portfolio’s response to global health threats? | • Are there effective learning and dissemination mechanisms in place? |

Methodology

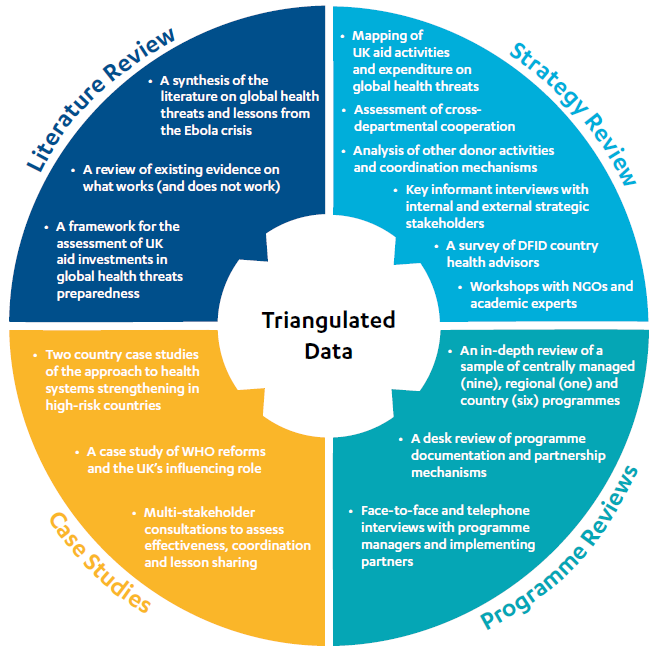

The diagram below outlines our approach to the review. The four main elements to our methodology were: a literature review, a strategy review, case studies and programme reviews.

Figure 1: Our methodology approach

Our literature review explored definitions of global health threats, views on the nature of these threats, perspectives on the international health system and its weaknesses, and the key lessons learnt from the Ebola crisis. It also considered evidence on effective practice in addressing global health threats. The literature review provided a reference point to assess the relevance, coherence and emerging effectiveness of UK aid investments.

In our strategy review, we mapped the response of the key departments involved with the UK government’s approach to addressing global health threats. This informed our assessment of: the relevance of the UK strategy; its added value; the visibility and coherence of the approach; its emerging effectiveness (including influencing and leveraging other actors’ contributions); the effectiveness of cross-government and external coordination; and the degree of ongoing learning and dissemination activity underway.

The strategy review drew on:

- desk studies of strategies, programmes and expenditure

- key informant interviews with UK government representatives and wider stakeholders, including from other bilateral donors, the WHO, philanthropic organisations (such as the Wellcome Trust and the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation) and pharmaceutical companies

- an email survey of DFID country health advisors

- two workshops, one with non-governmental organisations and one with academic experts.

We conducted programme reviews of a sample of nine interventions drawn from centrally managed programmes developed by DFID and the Department of Health, and six country-level programmes managed by DFID. The sample was drawn from the list in Annex 2 of all the programmes that we identified as relevant to global health threats.

To expand on insights generated by our programme reviews, we undertook two country case studies. We visited Burma and Sierra Leone to assess: the relevance of UK aid investments there; progress in their implementation; and lessons learnt from them. The country visits were complemented by a visit to the WHO headquarters in Geneva to examine efforts to support WHO reform and gather further perspectives on the UK aid response to global health threats. As part of these case studies, we spoke to a range of stakeholders including from the UK and partner governments, other donors and multilateral institutions.

Both our methodology and this report were independently peer reviewed.

Box 3: Limitations of our methodology

Our case studies and programme reviews were purposively selected to reflect a range of relevant contexts and programme types. The sample may not be fully representative, and caution should be applied to generalising all our findings to the UK government’s response to global health threats as a whole.

Given the review timescales, our literature review did not assess all relevant literature. Rather, we prioritised key sources based on an initial analysis of the likely significance and relevance of each source. As a result, some potentially relevant sources may not have been included.

As the scaled-up government response to global health threats in the wake of Ebola is relatively new, there was limited availability of independent evaluations and academic reviews of the government’s approach. Our review therefore relied on combining evidence from stakeholder perspectives and other sources with our own judgements of the available evidence, rather than drawing on fully evaluated and peer reviewed assessments of progress.

Background

Global health threats and the lessons from Ebola

The Ebola crisis brought the issue of global health threats into sharp relief. It exposed weaknesses in epidemic preparedness and response, and highlighted specific failings within the WHO and across the international health emergency response system. The crisis also demonstrated the fundamental challenge of responding effectively to global health threats in countries with weak national health systems, which are unable to comply with the detection and reporting standards of the International Health Regulations (see Box 4).

Box 4: The role of WHO and the International Health Regulations in epidemic preparedness and response

WHO

WHO, the UN’s health agency, is a key international actor in the field of global health threats. It provides technical guidance and support to governments and national health systems, shapes research agendas, sets international norms and standards, and monitors national and international action on global health priorities. It houses the Global Outbreak Alert and Response Network, established in 2000 to facilitate rapid outbreak responses by coordinating and deploying experts.

WHO is funded through a combination of assessed contributions (or membership fees) and voluntary donations. Its regional offices in Africa, the Americas, South East Asia, Europe, the Eastern Mediterranean and the Western Pacific support member states in generating health data, delivering health care, and managing health services at national and sub-national levels.

The World Health Assembly brings together the 194 WHO member states and is the WHO’s supreme decision-making body. The WHO executive board, with its 34 elected technically qualified individuals, advises on and facilitates World Health Assembly decisions.

The International Health Regulations

The International Health Regulations, developed under WHO auspices in 1969 and updated in 2005, are a legally binding agreement between 196 countries, committing them to build their own national capacities to detect, assess and report public health emergencies.

The regulations focus on the effectiveness of country disease surveillance and data reporting systems. WHO uses a voluntary joint external evaluation tool to monitor and evaluate how well countries conform to the regulations.

The experience of Sierra Leone, the country with the highest infection rates in the 2014-16 Ebola epidemic, illustrates how the outbreak developed, the resulting challenges and their impacts (Box 5).

Box 5: The Ebola crisis in Sierra Leone

WHO confirmed the first Ebola cases in Sierra Leone in May 2014, with 15 cases confirmed by June.8 The government closed its borders with Guinea and Liberia, along with a number of schools. Soon after, Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) reported that the outbreak was out of control. On 31 July, the Sierra Leone government declared a state of emergency. On 8 August, WHO declared the Ebola outbreak to be a Public Health Emergency of International Concern.

The outbreak peaked in October 2014, with cases reported in every district of Sierra Leone. By the time the WHO lifted the Public Health Emergency in March 2016, Ebola had killed 3,956 people in the country, just under one in three of those infected. Many survivors require ongoing, often intensive support to deal with the physical, social and psychological effects of their infection.

The outbreak quickly overwhelmed the health systems’ ability to respond. The UN’s Special Envoy on Ebola, David Nabarro, described how:

Ebola Treatment Units (ETUs) were full and indeed you were often in an ETU and seeing people arrive and being turned away because there was no place to be treated. Mortuaries were full, overflowing with bodies…There was a sense, not just of despair, but of abandonment.

Bringing the outbreak under control required concerted action by governments, charities, donors and multilateral organisations. The UK, the United States and France played pivotal roles in the response. Strong support for WHO from agencies and donors such as UNICEF and DFID was acknowledged to have made “an immediate large-scale difference”.

Interventions that helped bring the crisis under control were multifaceted and included:

- funding to build new treatment centres and deliver equipment

- improving the speed of quarantine procedures and access to treatment centres

- working with affected communities to develop new isolation processes

- improving the equipment and safety training available to health workers and burial teams

- accelerating the availability of medicines

- logistical support from, among others, the UK military

- improving community engagement and education

- ensuring the availability of food and supplies to affected communities and households.

While Ebola focused the world’s attention on the threat of epidemics, concern about global health threats had been high among policy makers for some time. Infectious diseases are major killers: in 2015, lower respiratory infections accounted for 3.2 million deaths worldwide. Tuberculosis (TB) caused an estimated 1.4 million deaths, while HIV-AIDS killed 1.1 million and malaria killed 429,000.

Drug resistance heightens the threat of such diseases by reducing the effectiveness of available treatments. Globally, 480,000 people develop multi-drug-resistant TB each year, and drug resistance complicates the fight against AIDS and malaria. The government-commissioned Review on Antimicrobial Resistance (known as the O’Neill review) gives a conservative estimate of 700,000 deaths per year caused by drug resistance globally, a figure that could rise to 10 million a year by 2050.

The economic costs of global health threats are also clear. Six major zoonotic disease outbreaks (infectious diseases beginning in animals and spreading to humans) in the period between 1997 and 2009 were estimated to have cost the world more than US$80 billion. Modelling commissioned as part of the O’Neill review suggests that, between now and 2050, the world can expect to lose between US$60 and US$100 trillion in economic output if drug resistance is not addressed.

Global health threats: the UK aid response

The 2015 UK aid strategy, published during the Ebola crisis, recognised that global health threats are a key challenge to British interests and international development, and included “strengthening resilience and response to crises” as a key objective. The rapidly scaled-up cross-government response global health threats was to a large extent based on the lessons from the Ebola outbreak (see Box 6).

Box 6: Lessons and insights from the Ebola crisis

The many reports investigating what went wrong during the Ebola crisis generally agree on the main weaknesses in the national and international outbreak response:

- Weaknesses in the international public health systems: International agencies and DFID relied on WHO surveillance systems, but the outbreak was declared after it was already out of control. Overall, international organisations had limited capacity to respond quickly.

- Weaknesses in national health systems: Weak national health systems in Sierra Leone, Liberia and Guinea lacked the capacity to recognise and contain outbreaks. These countries initially played down reports of Ebola due to fear of economic consequences.

- Poor communication: Community engagement was weak and public information campaigns sometimes counterproductive, discouraging people from seeking medical help.

- Lack of research readiness: Since Ebola had not been identified as a priority disease, the global health research community was not research-ready from the outset. It nevertheless geared up clinical trials for vaccines, treatments and diagnostics swiftly.

- Slow mobilisation of funding: Large-scale funding for the Ebola crisis was mobilised once developed countries felt under direct threat. Much smaller earlier investments in prevention could have averted the crisis.

- Lack of expert readiness: The speed and scale of the international response necessitated the mobilisation of staff who did not necessarily have the required expertise.

- Poor early coordination: Because it was labelled a health crisis, not a humanitarian emergency, coordination structures were ad hoc, and non-health aspects of the crisis response were poorly coordinated, particularly in the early stages.

The Department of Health and DFID are the two main departments charged with delivering the UK’s aid agenda on global health threats. Public Health England, an executive agency of the Department of Health, is also central to the UK aid effort because of its internationally recognised public health expertise. The Cabinet Office plays a coordinating role during new outbreaks and health crises.

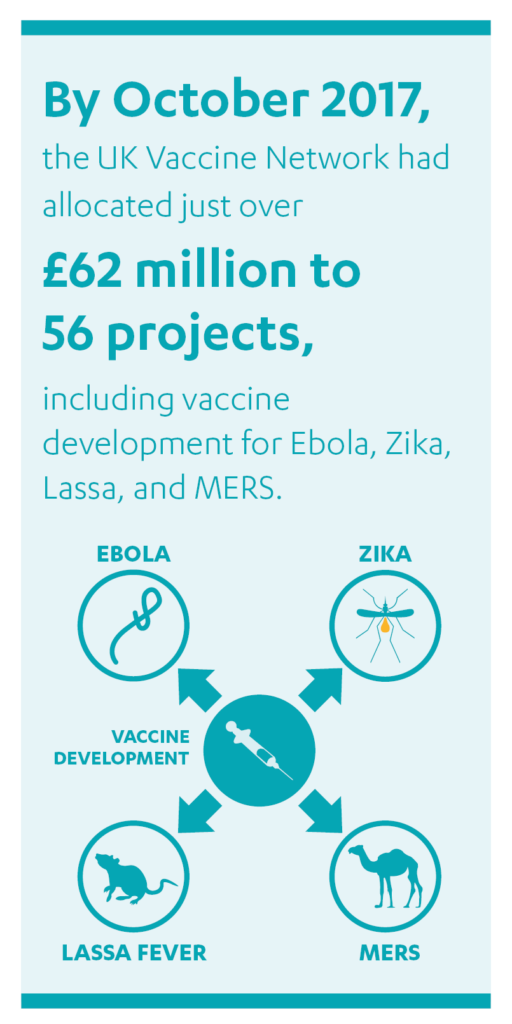

A new strategic framework for addressing global health threats, Stronger, Smarter, Swifter, was developed jointly by the Department of Health and DFID in 2015. Several centrally managed programmes align with this strategic framework (see Annex 2), with a total investment value so far of £631 million in the current spending review period (2016-21). Of this, £103.9 million is being invested in Stronger programmes, £500.9 million in Smarter, and £26.2 million in Swifter. Another £1 billion of core funding has been allocated to Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance (2016-20), although not all of this is spent on global health threats activities. Further relevant programmes are expected to come onstream from DFID in 2018.

Figure 2 lists the centrally managed programmes we selected for in-depth investigation, and outlines how they fit into the Stronger, Smarter, Swifter framework.

Figure 2: The centrally managed programmes we reviewed and how they fit into the Stronger, Smarter, Swifter strategic framework

Of the £631 million, £477 million can be clearly identified as additional spending on global health threats, corresponding with the Department for Health’s 2016 ODA allocation for its global health security programme. DFID was already making relevant investments prior to the Ebola crisis (for example in drug-resistant malaria in South East Asia), but has scaled up its work on epidemic threats and WHO reform. This includes over £50 million allocated to regional programmes in Africa and £6.2 million to strengthen the WHO’s response to health emergencies, with further investments in the pipeline.

Much of DFID’s country-level health work also furthers the global health threats agenda, even if not always as a primary goal. For instance, health systems strengthening programmes are crucial for the detection, treatment and containment of epidemic outbreaks. The lack of disaggregated spending data means we are unable to say how much country-level health spending goes specifically to activities tackling global health threats. Nevertheless, this expenditure, together with the scaled up centrally managed programmes addressing global health threats, accounts for a significant proportion of the total UK ODA budget for expenditure in the health sector of £9 billion over the period 2016-21.

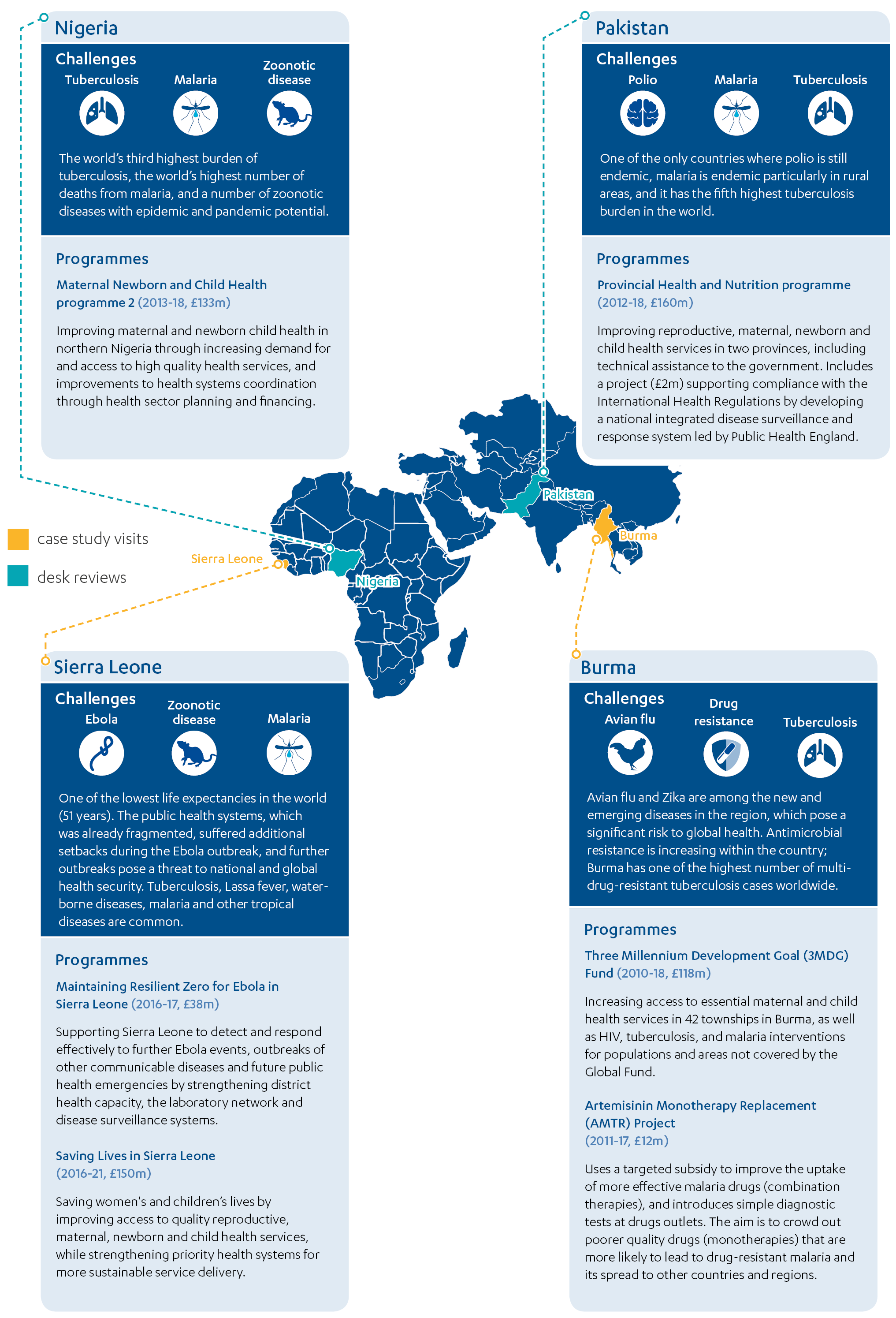

DFID has identified nine countries with global health threats activities within its country programmes. We selected six programmes from four of these priority countries for more in-depth review (see Figure 3). We made case study visits to Burma and Sierra Leone to review four of the programmes and conducted desk studies of the two programmes in Nigeria and Pakistan.

Figure 3: DFID country programmes assessed by the review

The UK’s strategy includes a range of international influencing objectives, recognising that its success relies on encouraging other countries, donors and non-governmental organisations to commit to and invest in global health threats preparedness (see Box 7).

Box 7: International influencing objectives within Stronger, Smarter, Swifter

Stronger

- international policy leadership on health systems strengthening

- WHO reform and improved global coordination

- promote the International Health Regulations

- secure commitments to health data sharing.

Smarter

- promote the antimicrobial resistance global action plan

- co-create and secure a UN General Assembly resolution on antimicrobial resistance.

Swifter

- strengthen WHO’s Global Outbreak Alert and Response Network (Box 4)

- secure financial contributions to the WHO Contingency Fund for Emergencies

- influence the design of the World Bank’s Pandemic Emergency Financing Facility.

Governance and coordination mechanisms

The governance of the UK’s Stronger, Smarter, Swifter agenda is spread across a number of government departments and bodies. At the top sits a global health oversight group, convened in 2016, with representatives from DFID and the Department of Health. It oversees global health policy and programming of mutual interest between government departments, including the cross-government response to global health threats. However, formal accountability for global health security programming lies with individual departments.

The global health security programme board is the formal governance mechanism overseeing the work carried out under each project within the global health security programme in the Department of Health. Some of the programmes have their own project boards (including some with DFID representation), which feed into the programme board.

A joint DFID-Department of Health global health research working group began meeting in 2017 to coordinate ODA-funded research on global health. A high-level steering group oversees implementation of the UK’s antimicrobial resistance strategy. A new Strategic Coherence of Official Development Assistance-funded Research Board (SCOR) was announced in September 2017, tasked with coordinating development priorities across all ODA-funded research.

DFID and the Department of Health (with Public Health England) have responsibility for the majority of programming and influencing work, but since global health threats is a cross-government priority, other departments and agencies also play a role:

- The Cabinet Office coordinated the government response to the Ebola crisis and the subsequent lesson-learning process that informed Stronger, Smarter, Swifter. The Cabinet Office’s Civil Contingencies Secretariat is responsible for emergency planning, which supports the government’s COBRA emergency response committee. In 2017, the secretariat established the International Health Risks Network, with cross-departmental representation, to help determine the UK’s response to new international disease outbreaks.

- The Government Office for Science produces the International Forward Look bulletin, which collates cross-government intelligence on international threats and disasters, including health threats, and shares these with the International Health Risks Network.

- The Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy oversees the Newton Fund and the Global Challenges Research Fund (GCRF), through which much ODA funding for research on global health threats is channelled.

- The Foreign and Commonwealth Office contributes to the government’s international influencing work, including with the G7, G20 and WHO.

- The Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (particularly its Veterinary Medicines Directorate) provides advice on zoonoses and antimicrobial resistance, from the perspective of how human, animal and environmental health interact (‘One Health’). The department also supports the UK’s international influencing activity on drug resistance.

Findings

Relevance: Does the UK have a coherent strategy for using aid to address global health threats?

In this section, we assess the relevance of the government’s approach to global health threats preparedness. We look at whether an appropriate and balanced strategy and programme portfolio were developed, based on learning and experience from the Ebola crisis and other evidence. We include consideration of whether DFID’s existing health programming has been sufficiently adapted to meet the imperative to tackle global health threats. Finally, we look at how well aligned the UK’s approach is with other donors and multilateral organisations active in this field.

In response to the Ebola crisis, the UK moved quickly to develop a coherent strategy for addressing global health threats

The inadequacy of the international response to the Ebola outbreak was a key driver behind the UK’s decision to scale up its investment in global health threats preparedness. From 2014 onwards, there was an effective cross-government effort to marshal the learning from the Ebola crisis, alongside evidence of the growing threat of drug resistance. This was rapidly translated into a set of policy proposals to reduce the impact of global health threats and crises, covering WHO reform, improved surveillance and access to medicines, tackling antimicrobial resistance, and a rapid response team.

By mid-2015, the UK had produced a coherent framework for action, Stronger, Smarter, Swifter. We found that the framework represents a relevant and balanced strategy for addressing the system weaknesses exposed by the Ebola crisis, as well as the ongoing challenge of drug resistance. It is also consistent with the high-level commitments of the 2015 UK aid strategy and the 2015 National Security Strategy and Strategic Defence and Security Review to strengthening the international response to health crises (including strengthening multilateral institutions, investing in science and technology and rapid response). The October 2017 Humanitarian Reform Policy also emphasises the importance of strengthening country health systems as part of health crisis prevention and response.

A number of success factors that supported the rapid development of the strategy for tackling global health threats were identified by the government and external stakeholders consulted for this review. These include:

- strong political leadership, including from the Cabinet Office minister and from the Prime Minister’s office

- the real-time nature of the review of the Ebola crisis, bringing added urgency

- the leveraging of external expertise

- rapid access to quality technical inputs at departmental level.

The framework’s focus on enhancing prevention and detection of, and response to, global health threats reflects the priority areas for intervention identified by external experts consulted for this review as well as the wider scientific literature (see Box 8).

Box 8: Evidence supporting the Stronger, Smarter, Swifter framework

Stronger

- The framework’s priorities to strengthen WHO capacity and leadership, and to reinvigorate commitment to the International Health Regulations on disease surveillance and reporting (see Box 4), are widely cited in the literature as necessary for improving the international response to global health threats.

- The focus on strengthening national health systems is supported by evidence on the need for disease-specific interventions to be complemented with broader health systems strengthening in order to better prepare countries for outbreaks and increase their resilience.

Smarter

- The Smarter theme of activity reflects an identified need for more effective vaccines, diagnostics and medicines for epidemic diseases, which can be brought onstream more rapidly during a crisis.

- The theme’s focus on international advocacy efforts is backed up by strong evidence (including the O’Neill review). Global commitments are necessary to combat antimicrobial resistance and establish new systems of surveillance in developing countries, due to the global scale and reach of the problem of resistance to antibiotics.

Swifter

- Swifter commitments to deploying public health and epidemiological expertise are supported by a strong consensus within the literature on the need for more effective rapid response mechanisms.

- The framework’s objective to leverage increased financial resources more rapidly during an outbreak reflects a clear recommendation from Ebola lesson-learning exercises.

We share the concern of some government stakeholders who questioned whether the framework gives sufficient attention to the specific challenges of addressing outbreaks in fragile or conflict affected settings, where the risk of epidemics is increased. DFID suggested that there is greater scope for learning from its humanitarian response operations, to inform both the overall strategy and the delivery of particular programmes such as the deployment of the UK Public Health Rapid Support Team.

The UK aid strategy pledges to make better use of the diverse expertise available across government. In the case of Stronger, Smarter, Swifter, responsibilities were allocated between the two main delivery departments, DFID and the Department of Health. This was largely based on existing departmental strengths, while also demonstrating the capability of these departments to adapt their activities in response to the lessons learnt from Ebola. For example, under Smarter, the Department of Health expanded its existing focus on vaccine development and drug resistance, while DFID built on its strengths in developing diagnostic tools and country implementation research. However, DFID also adapted its research to focus more on epidemic diseases, provide flexible research funding (to help respond to new emergencies) and include social science perspectives.

While there is a rational division of responsibilities between these two main departments, it is less clear whether and how other government departments are expected to contribute. For instance, the framework does not mention a range of relevant cross-government ODA-funded research programmes, such as the £1.5 billion Global Challenges Research Fund (GCRF) and the £735 million Newton Fund, both of which are managed by the Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy and include research on infectious diseases, health systems strengthening and antimicrobial resistance (see Annex 3).

The lack of links to other relevant cross-government research efforts constitutes a gap in the Stronger, Smarter, Swifter strategy, identified by both government experts and the review team. The framework’s research priorities are narrowly focused on the development of new products (for example vaccines for epidemic diseases). The framework neglects the need identified during the Ebola crisis for better social science-based research, for example aimed at understanding the social and cultural aspects of how epidemics spread, or how to strengthen health systems in such contexts.

DFID and the Department of Health developed a relevant and proportionate set of centrally managed programmes to strengthen the response to global health threats

Over the course of 2016, the Department of Health and DFID put together a portfolio of new and adapted centrally managed programmes, which we found to closely reflect the priorities of Stronger, Smarter, Swifter (see Figure 2 and Annex 2).

Each intervention within the portfolio responds to a distinct objective within the framework, while contributing to a set of coherent and mutually supportive approaches overall. For example, large scale investments in new vaccines are part of the Smarter response to diseases with epidemic potential. But these investments also support the fight against drug resistance, given the role that immunisation plays in lowering the incidence of initial infection and hence the need for treatment with antibiotics. Programmes funded under Stronger demonstrate a complementary, multi-level response to the framework’s commitments to strengthening the disease preparedness of health systems. These include:

- influencing WHO reforms at the global level (through the UK’s Core Voluntary Contribution and performance agreement)

- driving regional WHO reform (through the Tackling Deadly Diseases in Africa Programme)

- country systems work (through the International Health Regulations strengthening programme and relevant DFID bilateral health programmes).

The Department of Health and DFID have drawn on relevant evidence to support the case for individual programmes within the portfolio. Within programme business cases, there is further reference to the lessons learnt from Ebola and the scientific literature, as well as expert partner inputs and project-specific research. For example:

- DFID undertook a survey of health advisors to better understand the WHO’s performance at the country level.

- For the Tackling Deadly Diseases in Africa Programme, DFID drew on the WHO Joint External Evaluation assessments of how well countries adhered to the International Health Regulations to determine where to focus its support.

- In Sierra Leone, the need to strengthen the health workforce was evidenced through a survey that identified the number of active health workers relative to the total payroll.

While there is a significant threat posed by new epidemic outbreaks and drug resistance, there is also a disease burden from more long-standing health problems such as HIV/AIDS, tuberculosis and malaria. Importantly, we found that the portfolio of new and refocused global health threats programmes has not resulted in reductions in UK spending on other global health priorities. The government has maintained its significant expenditure on tackling more established diseases since the Ebola crisis, for example through its contributions to the Global Fund and Gavi. We therefore agree with the government and external stakeholders interviewed that the current focus and level of expenditure on global health threats is broadly appropriate.

At the time of this review, the Department of Health (with DFID’s input) was also in the process of developing logic models and theories of change for the framework. These should be helpful for internal coordination and communicating the framework to external stakeholders.

The role of country health systems strengthening needs more emphasis across the Stronger, Smarter, Swifter framework and in centrally managed programmes

A number of the expert stakeholders we consulted, as well as some DFID representatives, were concerned that the new focus on epidemic threats should not come at the expense of health systems strengthening in partner countries (a key lesson from the Ebola crisis). We therefore looked at the prominence given to health systems strengthening within the framework as a whole, within centrally managed programmes and in DFID’s bilateral health programmes.

Positively, the framework includes a number of references to building country health systems within the Stronger theme of activity. However, the framework views health systems strengthening from the narrow perspective of meeting the International Health Regulations and improving disease surveillance, rather than taking a broader approach drawing on the WHO’s ‘six building blocks of an effective health system’. Moreover, the framework does not articulate in enough depth how the strengthening of health systems is valuable across all of the themes of Stronger, Smarter, Swifter. Health experts we consulted stressed that it is important to integrate disease preparedness activities (such as on antimicrobial resistance) within longer-term approaches to building sustainable health systems, wherever possible.

It follows that we found varying emphasis on sustainable health systems strengthening across the portfolio of centrally managed programmes. System strengthening is a key focus of the International Health Regulations Strengthening and Tackling Deadly Diseases in Africa programmes. By contrast, the business case for the Fleming Fund does not articulate its potential contribution to the strategic objective of health systems strengthening, although aspects are referred to in relation to programme delivery. In Burma, we found that the alignment between the Fleming Fund and broader efforts to strengthen the country’s health systems could have been stronger.

We found that Gavi’s health systems strengthening grants are channelled in many recipient countries through intermediary bodies, including UNICEF, and then to civil society organisations, rather than through government health systems. This reflects pressure to ensure accountability for donor funding, but may also miss a potential opportunity to strengthen national health systems.

DFID’s country-level health programmes are evolving in line with global health security priorities, although there is much more to do

In DFID’s plans and programmes at the country level, we found more of a mixed picture on the extent to which global health security priorities had been integrated. Only six out of 17 DFID operational plans developed between 2014 and 2016 referred to tackling global health threats, and only nine out of 24 DFID countries with health programmes had integrated global health threats activities into them. More positively, ten operational plans demonstrated an increased level of prioritisation of health systems strengthening over the period.

We selected four countries for in-depth review among the nine that had programmes with relevant global health threats activities: Burma, Ethiopia, Nigeria and Sierra Leone. In these countries, we found varying degrees of success in integrating objectives and activities related to global health threats, from specific activities such as enhancing surveillance systems and emergency response capabilities through to sustainable health systems strengthening.

Perhaps not surprisingly, given the Ebola experience there, bilateral programmes in Sierra Leone were most relevant to health threat preparedness (see Box 9). Based on our programme reviews and the survey of DFID health advisors, the Provincial Health and Nutrition Programme in Pakistan (2012-18) appears to be a more typical example of how global health threats priorities have been incorporated within bilateral health programmes. The programme includes a stand-alone project, delivered by Public Health England, on strengthening disease surveillance and compliance with the International Health Regulations. Outside of this specific project, we found a general lack of linkages between country-level programmes and the Stronger, Smarter, Swifter framework.

Box 9: Health programme alignment with Stronger, Smarter, Swifter in Sierra Leone

The DFID bilateral programme Resilient Zero (2016-17) aimed to prevent further Ebola transmission and to enhance preparedness against future outbreaks. This was to be achieved through developing stronger surveillance of diseases (working with WHO), smarter detection (through new laboratories and diagnostic tests supported and implemented by Public Health England) and a swifter response (through funding a fleet of vehicles and a deployable isolation treatment facility, working with the UK military).

The longer-term Saving Lives programme (2016-21) has a dual focus on reducing maternal and child mortality and strengthening resilience to infectious disease outbreaks. While primarily targeting maternal health, the programme also pursues a health systems strengthening approach, which largely reflects the WHO building blocks. DFID Sierra Leone and consortium partners are working with the government of Sierra Leone to:

- strengthen the health workforce, including community health workers

- improve health information and data sharing (including building on the surveillance and districtlevel

- capacity developed by Resilient Zero)

- improve access to medicines

- support national health strategy and planning.

Among the DFID country health programmes we reviewed, we observed few examples that were focused on tackling drug resistance directly. The exception was in Burma, where we saw programmes aimed at detecting and treating drug-resistant malaria and multi-drug-resistant tuberculosis, in response to evidence of the emerging prevalence of certain types of drug resistance across East Asia.

In many countries, the private sector (ranging from small informal drugs outlets to private sector hospitals) plays a large and growing role in health care delivery. However, in our sample of country programmes, we found strategies for private sector engagement at country level to be weak. The exception was Burma, where programmes engaged with private sector drug manufacturers, distributors and vendors to help phase out less effective anti-malarial therapies and to introduce simple diagnostic tests as part of the efforts to tackle drug resistance.

In our interviews, DFID advisors showed a good understanding of the link between disease preparedness and building more resilient health systems. But in the bilateral country programmes on global health threats that we reviewed, we found that health systems strengthening was an implicit rather than explicit objective. DFID country office staff told us that there is a need for guidance on how to maximise synergies between global health security programmes and health systems strengthening. Some government stakeholders and other donor representatives articulated a need to move from specific disease-focused approaches towards direct financial support for building government health systems and health services.

DFID was finalising a ‘UK position paper on strengthening health systems’ at the time of this review. The draft reviewed by the ICAI team included helpful explanations of the links between global health security and health systems strengthening (including the WHO’s building blocks). Publishing this will provide useful guidance for integrating aspects of health systems strengthening within both centrally managed and country-level programming.

The UK’s strategy adds value to international efforts by filling gaps and ensuring complementarity

UK programmes and influencing activities complement the efforts of other donors and international organisations by supporting the International Health Regulations, the WHO Research and Development Blueprint (which identifies priority infectious diseases to guide research and development activity) and the WHO Global Action Plan on Antimicrobial Resistance.

While a number of donors (including the US, Germany and Japan) are supportive of WHO reform, the UK is perceived as a leader in this area. Its linking of performance targets to its voluntary contributions is ground-breaking, with the WHO acknowledging that this is helping to focus reform efforts internally. Public Health England’s work supporting the International Health Regulations, and the UK Public Health Rapid Support Team, are embedded within the WHO’s systems, thereby helping to strengthen these systems and avoid duplication. At the country level, we found that DFID was often playing a coordinating role, building on its long-standing country presence and established forums involving partner governments and other donors. In Sierra Leone and Nigeria, DFID was supporting country health plans and facilitating strategic alignment across bilateral donors, UN agencies,nongovernmental organisations and these governments around strengthening country health systems.

The UK government’s investments in vaccines are complementing rather than competing with the private and philanthropic sectors. The UK Vaccine Network avoids duplication by targeting vaccines for uncommon diseases, where there is less private sector investment. The programme also has direct representation from the private sector among its membership. Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance, has placed greater emphasis in recent years on mobilising financial and other contributions from the private sector.

The UK is also adding value to the international effort by filling gaps in funding. For instance, the WHO Africa Regional Office told us that the UK is the only bilateral donor supporting them directly, despite general recognition that the WHO regional level needs strengthening. The UK-supported Contingency Fund for Emergencies fills another gap: while other emergency funds are coming onstream to support more severe and widespread disease outbreaks, this is the only international funding mechanism aimed at immediate response (within the first three months) to smaller-scale disease outbreaks. In support of this, we found evidence of early mapping of donor activities during the programme design phase of DFID and Department of Health programmes.

The UK faces an increasingly difficult challenge to keep pace with an evolving international landscape

The UK was an early mover in responding to global health threats, with a high risk appetite. Ensuring that the UK’s strategy and programmes continue to align with other donors and the private sector is an increasing challenge. There are new initiatives and increased activity from the World Bank, the African Union and the Asian Development Bank. Bilateral donors such as China and Japan and philanthropic organisations such as the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation are also increasingly engaged. This presents an opportunity for the UK, but also a coordination challenge.

Increased cooperation and coordination between the UK’s approaches and those of other donors could reduce overlap and enhance overall impact. This could include collaboration on country health systems strengthening work, for example with Germany and the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, or with the World Bank on investments in surveillance systems and financing emergency response.

Closer cooperation between the UK Vaccine Network and the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations would also be beneficial. The Coalition was established approximately 18 months after the UK Vaccine Network. The two initiatives have a common goal, and focus on supporting overlapping sections of the vaccines pipeline, particularly the mid-stage development of vaccines for epidemic diseases.

We found that existing mechanisms for coordination with external donors and the philanthropic and private sectors around global health threats preparedness are underdeveloped, beyond high-level meetings such as the G7, G20 and World Health Assembly. UK support for new structures such as the WHO’s Global Coordination Mechanism for Research and Development (linked to the WHO Research and Development Blueprint) and the Global Antimicrobial Resistance Research and Development Hub (see 4.62) represent a step in the right direction for achieving Smarter objectives. However, strong coordination mechanisms are lacking in other critical areas such as health systems strengthening (Stronger) and financing emergency response (Swifter).

Compounding this, the UK government has never published the Stronger, Smarter, Swifter strategic framework, nor provided comprehensive information on its portfolio of global health threats interventions or how responsibilities for these are divided between different departments externally.

Increased communication and openness would have helped partners to better align their spending with the UK government’s priorities and to avoid overlap. The Department of Health and DFID acknowledged that the development of a revised, more outward-facing strategy is required to ensure its ongoing relevance and coherence, particularly with external initiatives.

Conclusions on relevance

The UK moved quickly to diagnose the challenges relating to global health threats, based on evidence from the Ebola crisis and the emerging risk of drug resistance. The Department of Health and DFID responded with a relevant and well-balanced Stronger, Smarter, Swifter strategic framework underpinning a portfolio of interventions. Each major programme is supported by evidence of a strong strategic rationale.

The importance of social science-based research and health systems strengthening could be more clearly laid out within the framework. DFID country health programmes are evolving in line with the framework, but there is a need for global health security interventions in general to adopt a more explicit cross-programme focus on health systems strengthening. Links with DFID’s humanitarian policies could be strengthened, including approaches to responding to new outbreaks in fragile or conflict-affected settings.

Changes in the wider environment since the framework was developed highlight the need for a strategy review and refresh. With a number of actors entering or scaling up their activity in this area, it has become increasingly clear that the UK government needs to communicate and promote its strategy more clearly to other relevant actors and strengthen coordination mechanisms. Not doing so limits the government’s influencing capability and reduces the potential for other donors to align their activities and spending to the UK effort.

Overall, we have awarded the UK government’s global health threats agenda a green-amber for relevance. This recognises the considerable achievement in the wake of the Ebola crisis of developing a coherent framework for addressing global health threats, as well as a relevant portfolio of centrally managed programmes and influencing activities. However, there is a need to update its strategy in line with recent external developments, to clarify and strengthen the links between global health security and health systems strengthening, and to disseminate its strategy externally.

Effectiveness: Is the emerging aid portfolio a potentially effective response to global health threats?

In this section, we examine the effectiveness of the UK aid portfolio on global health threats. We take a separate look at each of the three themes of the portfolio, investigating in turn the performance and potential of programmes in our sample under Stronger, Smarter and Swifter. Given the early stage of delivery, with programmes largely covering the period 2016-21, this is based on an assessment of the potential effectiveness of programming and influencing work, as indicated by their plans and initial progress. We also review the extent to which wider ODA-funded research is being leveraged to support global health threats preparedness. Finally, we look at the effectiveness of the government’s coordination efforts.

Under the Stronger theme, UK interventions are helping to improve the responsiveness of the international system to global health threats

The main priority under Stronger is at the international level: encouraging WHO reform. The UK has used an appropriate combination of influence with the WHO and with other stakeholders, funding linked to performance targets and the development of a supportive relationship with the WHO to encourage improvements. Critically, the WHO’s leadership is supportive of the reforms agreed with the UK, and sees them as aligned with the organisation’s own ambitions.

We found that the UK has been successful in convening support for WHO reform from other major donors, including the US, Germany and Norway. This has been facilitated by the UK holding direct discussions, including through the donor group Friends of the WHO Health Emergencies Programme in Geneva. Other bilateral donors spoke positively of the UK’s leadership role and its influence. One donor representative noted that “the UK is clearly listened to by the WHO” and added that the UK’s performance agreement had helped focus the WHO conversation about reform.

The UK’s efforts have been influential in encouraging improvements in management and accountability within the WHO, as well as in increasing the organisation’s responsiveness to disease outbreaks. DFID’s first annual assessment (completed in mid-2017) of the UK’s £58 million Core Voluntary Contribution confirmed that the WHO was meeting all of its critical performance indicators and in several areas was exceeding expectations, including in risk management, financial management, transparency and working in partnerships (for example with Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance). Positive progress was also evidenced by the WHO’s response to the Zika virus (Box 10).

Box 10: Improvements since Ebola: an effective response to the Zika outbreak

On 1 February 2016, WHO convened an expert emergency committee to assess the Zika virus outbreak in the Americas and the threat it posed. The same day, it declared a Public Health Emergency of International Concern. A comprehensive strategic response plan followed two weeks later. The Contingency Fund for Emergencies was triggered and funds disbursed within 24 hours of the declaration, in accordance with the UK’s performance agreement target. A full incident management structure was set up at the WHO headquarters and all regional offices, and training and public awareness activities were carried out. The Zika appeal response was slow initially, with contributions from other donors only coming through six weeks into the outbreak. The WHO’s Contingency Fund filled the gap, allowing donors time to judge the potential impact of the outbreak and consider how to respond.

The UK government acknowledged that the WHO still needs to make significant progress, but that it is “pointing in the right direction”. The factors behind the UK’s success in influencing WHO reform include a coherent shared vision and an effective joint approach between the Department of Health and DFID to help maximise influence on WHO reform, an annual UK-WHO strategic dialogue, and the leadership of the UK’s Chief Medical Officer.

The UK government’s influencing activities extend to the regional and national levels. The Tackling Deadly Diseases in Africa Programme includes an action framework between the UK and the WHO Africa Regional Office. The framework details how the two will work together to improve health security and universal health coverage in Africa, and create a responsive and results-driven WHO secretariat. DFID’s prominent role has also helped influence the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation to provide support to the WHO Africa Regional Office.

We also found evidence of limits to the UK’s influence. Only modest progress was made on leveraging additional funding to support the WHO’s Health Emergencies Programme (see 4.78). Strengthening the accountability of WHO regional and country offices (outside of the WHO Africa Regional Office), and addressing their capacity constraints, have proved challenging.

Positively, the UK has reacted to these limitations by attaching new performance indicators to the Core Voluntary Contribution for 2017-18. These include improving the quality of the WHO’s country representatives and making progress on replenishing the Contingency Fund for Emergencies.

DFID recognised that ultimately it is up to the WHO to demonstrate through continued improvements why donors should support the organisation. However, DFID and other bilateral donors also acknowledged that they could do more to reach out beyond the like-minded member states that they currently work with in Geneva, in order to help influence a broader set of donors to commit funding to WHO reform. We also found that some DFID country offices could interact more with the WHO, in order to help encourage quick wins and improve the WHO’s accountability at this level.

UK support for implementation of the International Health Regulations is likely to have a positive impact

Another priority under the Stronger theme is the £16 million International Health Regulations Strengthening programme, led by Public Health England. We judge that this programme is likely to make an effective contribution towards its target countries meeting health regulation requirements. The programme is underpinned by a strong evidence base, the prior experience of Public Health England in supporting country compliance with the regulations and positive engagement with country governments. There is also evidence of a strong partnership between the programme and the Tackling Deadly Diseases in Africa Programme. This should help to ensure a mutually supportive approach to strengthening health systems in the region.

At the time of our review, Public Health England had completed scoping missions to appraise the requirements of each target country, and received positive responses to its implementation plans from partner governments. This should also help ensure that the programme has a stronger and more sustainable impact on country health systems. Box 11 summarises the results of the Nigerian scoping mission.

Box 11: Public Health England’s scoping mission to Nigeria

Nigeria, Africa’s most populous country with more than 190 million inhabitants, is one of five countries that took part in the scoping phase of Public Health England’s International Health Regulations Strengthening programme. Nigeria has some of the world’s highest levels of tuberculosis and malaria, and a number of zoonotic diseases with epidemic potential. West Africa has a long tradition of regional migration, and communities straddle international borders. A stronger, more resilient Nigerian health system, better able to contain epidemics, would therefore have positive effects beyond its borders.

Public Health England’s scoping mission to Nigeria led the agency to conclude that there is strong political will, in-country leadership and donor interest in place, suggesting that the country is well placed to achieve rapid and significant improvements in its health systems. Based on this conclusion, Public Health England will support the Nigerian government in undergoing a full health systems evaluation (WHO’s Joint External Evaluation) and will help develop and implement an action plan to address weaknesses exposed by this evaluation.

Despite this positive progress, we observed room for improvement in coordinating the work of Public Health England, DFID’s bilateral health programming and the Fleming Fund, to help countries meet the International Health Regulations. DFID suggested that the WHO’s Joint External Evaluation process and country action plans (once complete) should help to improve coordination by providing a common set of priorities to work towards.

DFID’s country programmes with a focus on global health threats are helping to strengthen the capacity of national health systems, although more could be done

The Stronger theme includes an objective for countries to develop “resilient, responsive and accountable health systems, including surveillance”, and to make progress towards meeting International Health Regulation obligations. Alongside support from the Fleming Fund, the UK government’s contribution is delivered primarily through bilateral health systems strengthening efforts.

We concluded that each of the DFID country programmes we reviewed (in Burma, Nigeria, Pakistan and Sierra Leone – see Figure 3) is beginning to make an effective contribution to global health threats preparedness. We base our conclusion on the appropriateness of programme designs, the strong overall performance of DFID’s health programmes, and emerging evidence of positive contributions towards the development of well-functioning health systems. We also saw evidence that DFID is influential in its relationships at country level, with other bilateral donors, with multilateral partners and with country governments.

The work of DFID’s £38 million Resilient Zero programme in Sierra Leone to help build an effective surveillance and response system, in partnership with the WHO, Public Health England and others, provides an illustrative example of an effective contribution to global health threats preparedness (see Box 12).

Box 12: Case study – building effective surveillance in Sierra Leone

As part of Resilient Zero, the UK contributed £7.7 million to the WHO Sierra Leone office to improve systems for the detection of diseases with epidemic potential. This helped revitalise an integrated disease surveillance and response system and supported training for community health workers to conduct community-based surveillance. Resilient Zero supported continuity by building on the operational support that DFID had provided during the Ebola outbreak, for example to district health management teams.

Through this support, Sierra Leone has built up what one external stakeholder called an “extremely well-functioning detection system”. All health facilities provide weekly reports on 26 different diseases, and these are aggregated into a national report, which is discussed in weekly meetings with the government and health partners. The Joint External Evaluation of Sierra Leone’s progress towards compliance with the International Health Regulations judged Sierra Leone to have “robust” systems in place.

Reporting rates across districts are now in excess of 90%. Numerous alerts have been reported over the last two years, covering diseases from measles and monkey pox to Ebola. This surveillance structure proved useful following the August 2017 mudslide in Freetown by supporting a coordinated and responsive approach to suspected cholera cases (including deployment of the UK Public Health Rapid Support Team).

While, as previously noted, health systems strengthening was not an explicit objective of the country programmes reviewed, all programmes included at least some activities that have made a positive contribution towards the WHO’s building blocks of a well-functioning health system. For example, the £150 million Saving Lives programme in Sierra Leone and the £118 million Three Millennium Development Goal (3MDG) Fund programme in Burma were covering most or all of the building blocks of an effective health systems. Specific examples of the contributions of DFID’s bilateral programmes to building responsive and resilient health systems are included in Annex 4.