Annual report 2024-2025

Foreword from the Chief Commissioner

I am delighted to publish the 2024-25 Independent Commission for Aid Impact (ICAI) Annual report, the first of ICAI’s fourth Commission. ICAI 4 began in July 2024, with the appointment of my fellow commissioners, Liz Ditchburn and Harold Freeman. I formally took up my appointment as chief commissioner in January 2025.

The start of a new Commission is an opportunity to take stock. ICAI took full advantage of the disruption to the rhythm of scrutiny work caused by the general election to learn lessons and look ahead. Extensive consultations with stakeholders, including a public consultation exercise, were held. This meant that different perspectives could inform early thinking about what a new Commission should focus on, and how ICAI could work most effectively.

The fourth Commission’s first report, How UK aid is spent, was published in February 2025. It took stock of recent trends in official development assistance (ODA) globally, and mapped UK development budget allocations in the global landscape for development finance, highlighting stalled progress towards the Sustainable Development Goals in many areas. The report was intended as a baseline, from which we could track UK aid as the government built back towards 0.7%. Just as we published, the prime minister announced that, although still committed to 0.7% in the longer term, UK ODA would in fact reduce from 0.5% to 0.3% of gross national income in 2027. Scrutinising how the UK implements these reductions and reviewing the effectiveness of the UK’s approach to international development with much smaller budgets will be the defining context for much of the work of this Commission.

The reduction in UK budgets alongside reductions by other Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development donors, and most notably the US, has prompted a wider conversation about the future of development and what aid effectiveness means in a changed context. This brings challenges and opportunities for ICAI. Continued volatility presents a challenge because, by their nature, reviews are backward-looking. Review recommendations need to be forward-looking, so that learning from past practice is relevant to the decisions of a new government, itself delivering its priorities in an uncertain context. With this challenge in mind, we will refresh our approach to making recommendations, and to follow-up reports, which remain critically important to ensure that ICAI reviews contribute to improved impact.

That said, the alignment of the start of a new Commission with a new government also gives us an opportunity to plan our work strategically. Phase 4 reviews will sit under broader themes, which reflect issues that ICAI has long taken an interest in. These include climate change, human rights and democracy, the effectiveness of aid in conflict settings, partnership, and humanitarian crises. In addition, we want to gather evidence on themes that cut across all reviews, such as poverty and gender inequality. This approach builds on the well-established tradition of ICAI synthesis reports, which summarise key themes at the close of each Commission.

In the meantime, ICAI’s scrutiny work is well underway. We have published our work plan for future reviews, and reviews on energy transition and UK aid in response to the crisis in Sudan will be published later this year. Additional reviews, including revisiting the UK’s work on ending violence against women and girls, last considered in 2016, and a review of the management of the ODA spending target, are also getting started at the time of writing.

This annual report also covers the final months of ICAI’s third phase, which saw the publication of five reviews: UK aid for sustainable cities, The UK Department of Health and Social Care’s aid–funded global health research and innovation, UK humanitarian aid to Afghanistan 2023–24, UK humanitarian aid to Gaza and UK aid to Ukraine. I am pleased to say that government fully (83%) or partially (17%) accepted review recommendations. We will be following up on the actions government has taken as a result.

I am fortunate to have joined a committed ICAI team that is fully staffed and am grateful for all the work done this year by all of those involved in reviews, and especially the contributions of those communities most affected by the issues we have examined. Following the general election, the International Development Committee has been re-appointed. I look forward to working closely with Parliament and others engaged in the critical task of delivering UK aid, to ensure that ICAI recommendations translate into meaningful improvements in development assistance.

I want to thank previous commissioners for their work, and I am grateful to Harold Freeman and Liz Ditchburn for taking on the extra responsibilities of leading ICAI from July 2024 until January 2025. As the gap between levels of global poverty and the resources available to meet need grows, the role of independent scrutiny remains crucial. ICAI will remain focused on providing vital insights to increase impact and value for money, and I feel privileged to be working with you all on this shared endeavour.

1. Reviews published during 2024-25

The Independent Commission for Aid Impact’s (ICAI) programme of reviews is agreed each year with Parliament’s International Development Committee (IDC). We choose our topics by consulting with a wide range of stakeholders and by using a number of selection criteria including: the amount of UK aid involved; relevance to the strategic priorities of UK aid and coverage of a wide range of Sustainable Development Goals; the level of risk; the potential evaluability of the subject and added value of an ICAI review.

During the reporting period (April 2024 to March 2025), ICAI issued eight publications, including the 2023-24 annual report.

Table 1: ICAI 2024-25 reviews and scores

| Review title | Review type | Publication date | Score |

|---|---|---|---|

| How UK aid is spent | Strategic overview | February 2025 | Not scored |

| UK aid for sustainable cities | Full review | July 2024 | Green/Amber |

| The UK Department of Health and Social Care’s aidfunded global health research and innovation | Full review | July 2024 | Green/Amber |

| UK humanitarian aid to Afghanistan 2023-24 | Information note | July 2024 | Not scored |

| UK humanitarian aid to Gaza | Information note | May 2024 | Not scored |

| ICAI follow-up review of 2022-23 reports | Follow-up | May 2024 | 57% of responses scored as adequate |

| UK aid to Ukraine | Rapid review | April 2024 | Not scored |

Themes of the year

Key themes emerging from 2024-25 reviews

This account highlights key cross-cutting issues emerging across our reports from April 2024 to March 2025, although in practice this covers the five reports published between April 2024 and July 2024, which constituted the end of the extension period to the third Commission. The first reviews of ICAI’s fourth Commission are due for publication at the end of 2025.

Three of the five reports published in 2024-25 focused on the UK’s response to humanitarian crises. The April 2024 UK aid to Ukraine rapid review, the May 2024 UK humanitarian aid to Gaza information note, and the July 2024 UK humanitarian aid to Afghanistan 2023–24 information note, which gave a detailed update on the 2023 ICAI information note on the same theme, all looked at how the UK navigated delivery of its humanitarian assistance in the context of multiple complex challenges. These challenges included facing barriers to humanitarian access, managing risks around potential aid diversion, ensuring the protection of aid workers, and upholding adherence to international humanitarian principles.

The UK committed resources and demonstrated a rapid and flexible approach in responding to humanitarian crises in Ukraine, Gaza and Afghanistan. Following the full-scale Russian invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, Ukraine became the largest recipient of UK bilateral aid, with (at the time of the ICAI report) around £228 million in bilateral aid in 2023-24, alongside £1.6 billion in the form of guarantees for World Bank lending. ICAI reported that the UK swiftly mobilised resources, contributing £26.5 million to the flagship Partnership Fund for a Resilient Ukraine, a £90 million multi-donor initiative, and facilitated World Bank and International Monetary Fund loans to support Ukraine’s resilience and public service delivery. In Ukraine, ICAI reported a specific focus on women and girls, marginalised groups, people with disabilities and elderly people, ensuring that their needs were addressed in the humanitarian response, with support for a range of specialist organisations both directly and indirectly. This has been complemented by engagement with government on national policy and the promotion of gender-sensitive and inclusive planning for reconstruction and recovery. Following Israel’s initial response to the 7 October Hamas terrorist attacks in 2023, the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO) immediately prioritised employing diplomacy in the hope of lessening restrictions on humanitarian access. The Occupied Palestinian Territories (OPTs) are a longstanding recipient of significant UK official development assistance (ODA), and in 2023-24 the UK allocated an additional £70 million for humanitarian support, with a further £16 million provided to the UN Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees (UNRWA) from the humanitarian programme. However, ICAI found that lack of humanitarian access significantly hindered efforts in Gaza over the reporting period, with the delivery of aid severely restricted by the Israel Defence Forces (IDF). In Afghanistan, ICAI reported that despite the challenging environment post-Taliban takeover and following dramatic fluctuations, UK aid had stabilised at around the level seen before the Taliban takeover. FCDO spent £113.5 million in Afghanistan in 2023-24, largely on urgent humanitarian needs, and the UK’s planned bilateral support for Afghanistan for 2024-25 was £151 million. In its strategy on Afghanistan, FCDO aimed to balance short- and long-term goals, responding to acute humanitarian needs while also helping to foster national resilience into the future. ICAI reported that support for women and girls remained a core FCDO objective in Afghanistan and that FCDO had developed an Afghanistan women and girls strategy for 2023-27, which aimed to protect Afghanistan’s most vulnerable women and girls, mitigate the worst effects of Taliban rule, and invest in the next generation of female leaders.

The UK leveraged diplomatic efforts to navigate complex political challenges, uphold international law and accountability in its humanitarian responses, and address significant barriers to humanitarian access impacting the delivery of aid – with mixed results. In addition to funding for both acute needs and long-term recovery in Ukraine, ICAI found that the UK had emphasised the importance of international law, rights and accountability, pledged £6.2 million to support the investigation of war crimes, and committed to building Ukraine’s capacity for survivor-centred justice for conflict-related sexual violence (CRSV). In Gaza, ICAI reported that lack of humanitarian access significantly hindered humanitarian efforts, with the delivery of aid severely restricted by the IDF. Protection of humanitarian workers was poor, as evidenced by reports that 244 aid workers had been killed in Israeli military operations between October 2023 and May 2024. Following Israel’s initial response to 7 October, FCDO immediately prioritised employing diplomacy in the hope of lessening restrictions on humanitarian access. As the conflict progressed into early 2024, this messaging became more public and more urgent, with former Foreign Secretary James Cleverly emphasising the UK’s focus on “securing a humanitarian pause, stopping the fighting right now, so we can see hostages released, more aid delivered, then turn this into a sustainable ceasefire without a return to fighting”.[1] Despite this, at the time of the report’s publication, international pressure had yet to bring about change. In Afghanistan, humanitarian access remained severely constrained due to “restrictions placed on female aid workers, bureaucratic impediments and threats against humanitarian personnel and assets”.[2] It was reported that FCDO aimed to use UK influence to mobilise international humanitarian support to Afghanistan and improve coherence at both the delivery and diplomatic levels, for example via pushing for the renewal of the UN Assistance Mission in Afghanistan’s mandate, hosting a forum of G7 Special Representatives to Afghanistan in London in January 2024 and co-founding the Afghanistan Coordination Group (ACG). When asked about international engagement with the Taliban, FCDO told ICAI that the UK’s global policy is to recognise states, not governments, but it supports pragmatic dialogue with the Taliban. At the time of the ICAI information note’s publication, the UK intended to re-establish a diplomatic presence in Kabul when the security and political situation allows.

The UK implemented various strategies to enhance risk management and mitigate challenges in delivering humanitarian aid, given the significant risks of aid diversion and potential fraud. ICAI highlighted the significant risk of fraud and corruption regarding the UK’s aid to Ukraine, demonstrating that “FCDO has set itself a high risk appetite in Ukraine, but is limited in its own ability to monitor fraud and corruption risks due to security constraints”.[3] ICAI recommended strengthening third-party monitoring to reduce this risk, as well as helping Ukraine’s independent anti-corruption bodies to identify and manage corruption risks associated with large-scale reconstruction. The diversion and possible misuse of aid was also highlighted as a significant risk in the Gaza response. ICAI reported that FCDO and its UN partners saw increasing the supply of humanitarian goods as the most effective approach to minimising this risk, as scarcity serves as the main driver of the war economy. In Afghanistan, ICAI again highlighted that the diversion of aid remained a risk, particularly due to the lack of in-country FCDO staff. FCDO had made attempts to improve risk management, including via better context analysis and scenario planning, and new risk management toolkits had also been developed. It was reported that FCDO aimed to use UK influence to mobilise international humanitarian support to Afghanistan and improve coherence at both the delivery and diplomatic levels (see the previous paragraph for examples).

In addition to the 2024 reports on UK humanitarian efforts in Ukraine, Gaza and Afghanistan, ICAI published two reviews in July 2024: UK aid for sustainable cities and The UK Department of Health and Social Care’s aid–funded global health research and innovation. These reports covered a range of elements around ‘localisation’ in UK development and humanitarian efforts, including the importance of locally led research, alignment with national and local government strategies, and the challenges of finding ways of managing risk without overburdening local partners, particularly in humanitarian contexts.

UK aid-funded research has struggled to fully integrate local stakeholder perspectives and voices, particularly in Africa and low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), and the UK needs to improve equitable partnerships and strategically build research capacity to ensure better outcomes and value for money in developing contexts. The July 2024 UK aid for sustainable cities review highlighted individual examples of thoughtful approaches to local stakeholder engagement, although the two country case studies found mixed performance in integrating local stakeholder perspectives. The UK was found to perform less well overall than other donors on integrating the work of local researchers into project design, particularly in Africa. For example, the priorities of the Centre for Sustainable, Healthy and Learning Cities and Neighbourhoods were set primarily by the UK Government, with little local input. By contrast, the FCDO-funded Africa Cities Research received praise for effective inclusion of not only researchers but civil society, local and national politicians, and municipal employees. In general, the UK’s urban programmes have performed well at aligning with national and local government priorities, but results on direct citizen engagement were mixed. Our July 2024 The UK Department of Health and Social Care’s aid-funded global health research and innovation review provided useful analysis of the UK’s efforts to localise its health research. The review found that DHSC’s guiding principle of ‘equitable partnerships’ for ODA-funded research has not been fully implemented. The National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) provides support and funding to enable LMIC researchers to participate in both research and dissemination. Nevertheless, the ICAI review found that DHSC had only recently opened most of their calls for proposals to non-UK institutions and, where they were eligible, few LMIC applicants were successful. LMIC voices have not been well integrated into learning activities. When scoping new areas of work, DHSC sought input from global experts but did not tend to engage with the research priorities of LMIC governments. Compounding this is the fact that DHSC had no in-country staff and very little contact with UK embassies and FCDO health advisers. The review recommended that DHSC fully embed the principle of ‘equitable partnerships’, as well as untying aid and taking a more strategic approach to research capacity building in LMICs, with the overall aim of ensuring that health research offers better outcomes, coherence and value for money in developing contexts.

In humanitarian contexts like Ukraine, Gaza and Afghanistan, managing risk without overburdening local partners was a significant challenge. ICAI’s work on Ukraine, Gaza and Afghanistan emphasised the challenges of working to support local partners in humanitarian contexts, despite a UK government commitment to do so. In Ukraine, international donors including the UK have struggled to partner with Ukrainian civil society organisations directly, with less than 1% of the $3.5 billion of international humanitarian finance raised allocated directly to national providers. In Gaza, the high risk of aid diversion and corruption has meant that FCDO has prioritised working with established agencies with existing capacity to deliver and monitor aid programmes, such as UNRWA, the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) and UNICEF. In Afghanistan, the UK had made inroads in localising aid. For example, FCDO provided funding towards a UN OCHA-led training programme to help national nongovernmental organisations apply for and manage international funding. Furthermore, the UK was making efforts to increase the share of funding from the Afghanistan Humanitarian Fund to national delivery partners to around 25%.

Finally, 2024-25 ICAI reviews highlight significant lessons for improving monitoring, evaluation and learning (MEL) approaches across UK aid programmes. Consistent data gathering, strategic performance indicators and coherent strategies contribute to understanding and aid effectiveness, value for money and impact. Proactive learning and adaptation, as seen in global health research, can lead to positive changes. Humanitarian contexts present unique challenges for MEL, requiring innovative solutions to collect meaningful data and apply learning.

UK aid efforts need to enhance MEL processes. While there are some signs of progress, overall, weak MEL often results in fragmented and inconsistent strategies at the portfolio level. ICAI reported that the UK aid for sustainable cities portfolio performed particularly poorly in MEL. Despite individual programmes generally including monitoring and evaluation plans, ICAI found that “the UK does not gather sufficient results data from its interventions, nor does it have any portfolio-wide strategic performance indicators to enable it to monitor and evaluate the progress and impact of its work on sustainable cities”.[4] There was inconsistent data gathering across programmes, and few independent evaluations are conducted. FCDO had also not conducted a value for money analysis of different delivery channels. This significantly hindered learning – to the extent that ICAI’s review itself was constrained due to a lack of data. This insufficient approach to learning, combined with the fact that work on sustainable cities has been fragmented across various teams both within FCDO and across government, led to an incoherent UK strategy on sustainable cities in developing contexts. By contrast, our The UK Department of Health and Social Care’s aid-funded global health research and innovation review praised DHSC for its proactive approach to learning, highlighting the department’s ability to continuously monitor outcomes and adapt its programmes accordingly. Over the period covered by the review (2018-25), the department’s record on learning had waxed and waned, but leaders have shown considerable efforts to make improvements where needed. As with the UK’s work on sustainable cities, there had been limited portfolio-level learning and few mechanisms for cross-portfolio learning between its Global Health Research (GHR) and Global Health Security (GHS) programmes. Formal monitoring and evaluation mechanisms are not yet used consistently across the GHR and GHS portfolios, and DHSC has been slow to complete and publish programme-level annual reviews. There were, however, positive signs of change, particularly within GHR, with reviews planned of the portfolio-level theory of change and of key areas such as Community Engagement and Involvement (CEI). Overall, DHSC demonstrated that where evaluations have been conducted, results are feeding into learning and improvement.

Conducting effective MEL during humanitarian crises is challenging due to severe operational constraints and high-risk environments. ICAI’s work on Ukraine, Gaza and Afghanistan highlights the difficulties of conducting MEL during humanitarian crises. In all three contexts, the UK’s focus is largely on monitoring and is aimed at ensuring that aid is delivered without interference. Severe constraints on aid workers operating in these contexts restricts the UK’s ability to collect meaningful data and apply learning, making it difficult to evaluate effectiveness and impact. In Gaza, ICAI challenged the UK to take action to ensure that adequate monitoring arrangements were put in place, including space for independent scrutiny. In Ukraine, because much of the aid has been delivered multilaterally, the UK relied on the monitoring and auditing arrangements of partners such as the World Bank and USAID. Travel restrictions hindered FCDO officials from conducting their own monitoring of UK ODA, which limited both understanding local contexts and actors and learning. However, the Ukraine programming demonstrated a good degree of learning from past conflicts in other contexts, particularly on stabilisation and on CRSV. In Afghanistan, FCDO did incorporate third-party monitoring into some of its programmes, which it used on a sample basis to ensure that UK aid is being delivered as intended. While some partners have flagged that the level of monitoring required by international donors is overly burdensome, FCDO maintains that its approach reflects the high risk level in the context.

[1] Independent Commission for Aid Impact, ‘UK humanitarian aid to Gaza’, May 2024, page 10

[2] Independent Commission for Aid Impact, ‘UK humanitarian aid to Afghanistan 2023–24’, July 2024, page 5

[3] Independent Commission for Aid Impact, ‘UK aid to Ukraine’, April 2023, page 31

[4] Independent Commission for Aid Impact, ‘UK aid for sustainable cities’, July 2024, page 40

2. ICAI functions and structure

ICAI was established in May 2011 to scrutinise all UK official development assistance (ODA), irrespective of the spending department. ICAI is an advisory non-departmental public body sponsored by the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO). It delivers its programme of work independently and reports to Parliament’s International Development Committee (IDC).

Our remit is to provide independent evaluation and scrutiny of the impact and value for money of UK ODA. To do this, ICAI:

- carries out a small number of well-prioritised, well-evidenced and credible thematic reviews on strategic issues faced by the UK government’s aid spending

- informs and supports Parliament in its role of holding the UK government to account

- ensures that it makes its work available to the public.

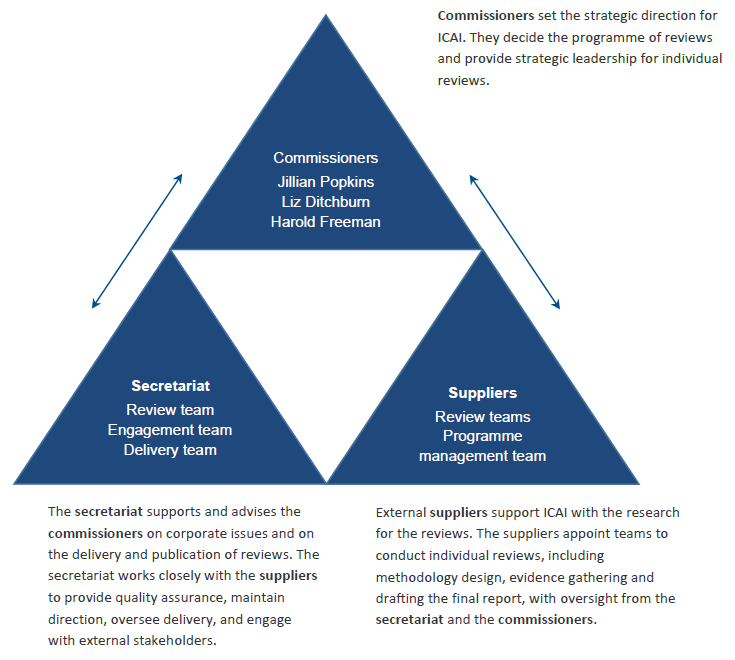

ICAI is led by a board of independent public appointees (the commissioners) who are supported by a Civil Service secretariat and external suppliers. These three component parts – commissioners, secretariat and suppliers – work closely together to deliver reviews. Figure 1 summarises the roles and responsibilities of the three parts of ICAI.

The ICAI team

Jillian Popkins, ICAI’s Chief Commissioner, leads the board of commissioners. ICAI’s other commissioners are Liz Ditchburn and Harold Freeman. The commissioners’ biographies are on the ICAI website.

Ekpe Attah leads ICAI’s secretariat of ten civil servants. They are responsible for review management (working alongside the external suppliers), supplier contract management, financial control and corporate governance, and communications and engagement. ICAI’s office is in Gwydyr House, Whitehall.

ICAI was supported in the research for its reports during 2024-25 by an external supplier consortium led by the specialist international development consultancy Agulhas Applied Knowledge. From July 2024, the consortium also included Ecorys UK, IOD PARC and ITAD.

Figure 1: High-level roles and responsibilities

3. Corporate governance

ICAI’s commissioners, who lead both the selection process for all reviews and the work on individual reviews, were appointed after an open recruitment process regulated by the Commissioner for Public Appointments. They hold quarterly board meetings, the agendas and minutes of which are published on ICAI’s website.

ICAI acts in accordance with the mandate agreed with the foreign secretary, set out in our Framework Agreement with the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO). ICAI’s remit is to provide independent evaluation and scrutiny of the impact and value for money of all UK government ODA. This involves:

- carrying out a small number of well-prioritised, well-evidenced and credible, thematic reviews on the UK government’s strategic objectives for aid spending

- informing and supporting Parliament in its role of holding the UK government to account

- ensuring that our work is made available to the public.

A copy of the Framework Agreement, which will be revisited in 2025-26 to reflect the transition to Phase 4 of ICAI, can be found on our website.

Transition to ICAI Phase 4

Our sponsoring department, FCDO, is responsible for appointing successive boards of ICAI commissioners and overseeing the procurement of our external supplier(s).

The appointments of Liz Ditchburn and Harold Freeman as new commissioners took effect on 1 July 2024. The appointment of Jillian Popkins as Chief Commissioner was announced on 18 December 2024, taking effect on 27 January 2025.

The tender process for the Phase 4 external supplier concluded in June 2024 with the signing of the supplier contract for the phase. The external supplier consortium for Phase 4 of ICAI will be led by Agulhas Applied Knowledge.

Risk management

The ICAI secretariat maintains a risk register which identifies and monitors ICAI’s corporate risks. It is reviewed regularly by commissioners at every Board meeting. ICAI’s risk register includes an assessment of gross and net risk, mitigating actions and assigned risk owners. It includes both risks relating to the operating environment and risks inherent to the production of ICAI reviews.

Conflict of interest

ICAI takes conflicts of interest, both actual and perceived, extremely seriously. Our independence is vital for us to achieve real impact.

We publish our conflict of interest and gifts and hospitality policies on our website and update the commissioners’ conflict of interests register every six months. We review potential conflicts of interest for all supplier team members before beginning work on reviews.

We manage any potential conflicts of interest on a case-by-case basis. The specialist nature of our work, and the requirement for strong technical input, means that we need to weigh the risk of a possible or perceived conflict with the need to ensure that high-quality and knowledgeable teams conduct our reviews.

Whistleblowing

ICAI has limited capacity to investigate concerns raised by the public and this is not part of our mandate. Our whistleblowing policy is on our website.

In line with the policy, if we receive allegations of misconduct, we offer to put the complainant in contact with the relevant department’s investigations team, if appropriate, or with the National Audit Office’s investigation function.

Safeguarding

ICAI complies with FCDO safeguarding and reporting standards. There have been no reports this year under our safeguarding policy.

Complaint handling

ICAI’s complaints handling process is published on our website. This process is designed to be both proportionate to our role and size, and distinct from our established procedures for reporting fraud and safeguarding concerns.

We received no complaints during the reporting period.

Information rights

ICAI received no subject access requests under the Data Protection Act or General Data Protection Regulation during the reporting period.

We received nine requests for information under the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA). In September 2024 reflecting best practice around information rights and transparency, ICAI initiated a publicly available log of responses to FOIA requests that we consider to be of wider public interest. We aim to update this at least every six months.

4. Financial summary

This chapter sets out:

- the overall financial position of ICAI

- expenditure for the financial year period April 2024 to March 2025

- the supplier cost of each ICAI review published in the financial year April 2024 to March 2025

Overall financial position

In the financial year April 2024 to March 2025, ICAI spent £2.234 million. This was within the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO) total approved budget for ICAI. The breakdown was £1.136 million on administration and £1.098 million on programme costs. The programme outturn in 202425 represented a significant underspend – by historic standards – against the original budget of £2.8 million. This was due to considerable delays in commencing Phase 4 reviews caused by the July 2024 general election and the subsequent reappointment of the International Development Committee (IDC). These events also contributed to the fact that the Phase 4 Chief Commissioner only took up post in January 2025.

Discharging ICAI’s remit means managing a rolling programme of reviews which often span financial reporting years. Consequently, costs payable to suppliers in any one financial year cover both reviews published in that year and initiation costs for those due for publication the following year.

Expenditure from April 2024 to March 2025

Total spend in the year for both programme and administration came to £2,234,007. The tables below provide a breakdown for programme and administration.

Table 2: ICAI programme spend April 2024 to March 2025

| Area of spend | Phase 3 April 24 to June 24 | Phase 4 July 24 to March 25 | Total expenditure April 2024 to March 2025 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Supplier costs | £312,171 | £734,545 | £1,046,716 |

| External engagement activities | £6,320 | £45,047 | £51,367 |

| Total programme spend | £318,491 | £779,592 | £1,098,083 |

Table 3: ICAI administration spend April 2024 to March 2025

| Area of spend | Total expenditure April 2024 to March 2025 |

|---|---|

| Secretariat pay costs | £812,170 |

| Commissioners’ pay and honoraria costs | £184,923 |

| 2024-25 office rent costs | £92,280 |

| 2023-24 office rent costs* | £6,340 |

| Travel costs | £9,789 |

| Office costs including training and office equipment | £30,422 |

| Total administration spend | £1,135,924 |

* A proportion of the 2023/24 rent costs were paid in 2024/25 due to delays in the management of ICAI’s offices being transferred to the Government Property Agency from the Wales Office.

In 2024-25, supplier costs (programme spend) were £1.098 million. This included the cost of reviews and information notes, project management and communication activities.

As explained above, some of this cost is for work on reviews for publication after March 2025 to maintain the pipeline of review production. Table 4 sets out the supplier costs to date directly attributed to each review published between April 2024 and March 2025. This includes costs paid to all suppliers involved in the production of the review. These costs are paid over several financial years and not solely in the year of publication.

Table 4: Total supplier cost for each review published April 2024 to March 2025

| Review | Supplier cost |

|---|---|

| How UK aid is spent | £191,857 |

| UK aid for sustainable cities | £344,483 |

| The UK Department of Health and Social Care’s aidfunded global health research and innovation | £352,504 |

| UK humanitarian aid to Afghanistan 2023-24 | £44,128 |

| UK humanitarian aid to Gaza | £61,077 |

| ICAI follow-up review of 2022-23 reports | £187,238 |

| UK aid to Ukraine | £175,925 |

The variation in the costs of ICAI reviews is driven by the breadth of the topic under review and the methodological approach required to provide robust and credible scrutiny of the topic (including whether and how many country case studies and visits may be required and the extent of citizen engagement research to discover the views of people affected by UK aid).

5. ICAI’s performance

This chapter sets out performance during the year against ICAI’s key performance indicators for 2024-25.

Table 5: Performance summary 2024-25

| Key performance indicator | Outcome |

|---|---|

| Proportion of ICAI recommendations accepted or partially accepted by the government | Out of 24 recommendations, 83% were accepted and 17% partially accepted by the government |

| Based on follow-up reviews, the proportion of ICAI recommendations actioned by the government and changes in HMG practice due to ICAI reviews | The data set for this indicator is incomplete for 2024-25, due to the delays in commencing Phase 4 reviews (set out in the financial summary section above) |

| International Development Committee (IDC) satisfaction with ICAI | Parliamentary stakeholders, including IDC, regard ICAI as key to supporting Parliament’s scrutiny role |

| ICAI communications and engagement activity | ICAI continues to promote its reviews effectively to stakeholders and the public, reaching different audiences through different channels |

| Media and social media coverage | ICAI continues to achieve accurate media coverage and its social media channels continue to grow |

| Budgetary control | ICAI operated within budget |

Government responses to ICAI reviews

The government has six weeks to publish a response to an ICAI review. By the end of March 2025, we had received responses from the government for five of our reviews published during 2024-25. The government does not formally respond to information notes. In government responses received by ICAI in 2024-25, the government accepted 20 of ICAI’s recommendations and partially accepted four. No recommendations were rejected.

Working with the International Development Committee

ICAI’s work with the International Development Committee (IDC) plays a vital role in delivering real improvements to how UK aid is spent, through hearings in relation to our work or contributions to IDC inquiry evidence sessions.

There was no sitting IDC between the dissolution of Parliament in May 2024 ahead of the general election, and October 2024 when the new membership was appointed. Jillian Popkins appeared before the IDC in December 2024 for a pre-appointment hearing and was endorsed as ICAI Chief Commissioner. We also provided private briefings to the IDC on third Commission reviews published before the dissolution of Parliament.

ICAI continues to work with the IDC to consider how we can best support scrutiny by MPs and Peers of government aid spending. We also continue to engage other Parliamentary Committees and All-Party Parliamentary Groups as appropriate, to brief them on the findings of relevant ICAI reviews. We proactively share our work with the Parliamentary Libraries to help inform their briefings.

External engagement

ICAI’s remit includes ensuring that our work is accessible to the public. ICAI has continued to prioritise strategic engagement with all its key audiences – the government, Parliament, the development sector, and the public – to promote interest in and the impact of its reviews. Positive and proactive engagement has taken place for each ICAI publication, with development sector stakeholders regularly consulted at all stages in the review cycle, through evidence-gathering roundtables and workshops, briefings and events. However, external engagement was constrained towards the end of the third Commission due to restrictions on communications ahead of the 2024 general election.

In September 2024 we launched a public consultation to hear views from stakeholders on which areas of the UK aid programme should be the highest priority for review. We also asked for thoughts about how we carry out and communicate about our work, so that we can maximise our effectiveness and ensure Parliament and others can hold the government to account. The consultation, which was open between 4 September and 16 October 2024, received 234 responses from a diverse range of stakeholders, including government officials, civil society organisations, private sector representatives, academics and members of the public.

We published a summary of the responses on our website in December 2024 and announced that we would be starting reviews on two themes which came through strongly in the consultation – UK aid to Sudan, and how UK development funding is supporting the global transition to renewable energy.

Events

ICAI endeavours to run a full programme of events to maximise the impact of its work and increase understanding and learning around its findings. We participated in or arranged more than 15 events over the past year.

In April 2024, we partnered with British Expertise International (BEI) for an event on our review of UK aid’s international climate finance commitments, our final public event of the third Commission before the pre-election period.

After the general election and the appointment of Liz Ditchburn and Harold Freeman, the new commissioners took early opportunities to engage with stakeholders and promote ICAI’s recent work. In September 2024, Liz Ditchburn contributed oral evidence to an inquiry by the Scottish Parliament Cross Party Group on International Development into transparency in international development. In November 2024, Harold Freeman spoke at the UPEN International Policy Engagement Summit on Global Health, hosted by Aston University, about ICAI’s July 2024 The UK Department of Health and Social Care’s aid-funded global health research and innovation report.

In February 2025, we held the first major event of the new Commission, partnering with Chatham House to discuss our How UK aid is spent report, outlining the current trends and themes in UK development assistance amid a challenging global and domestic context.

Commissioners also took part in staff learning events for the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO) during the past year, with Tarek Rouchdy discussing ICAI’s review of tackling fraud in UK aid with officials in June 2024. In November 2024, Liz Ditchburn took part in a government evaluation conference in Edinburgh.

In addition, we arranged pre-publication stakeholder briefings for our reports on topics including Ukraine, Gaza, Afghanistan, global health research and sustainable cities.

We are grateful to all our panellists and partner organisations for helping to make our events a success.

Media and digital

ICAI’s reviews generated media coverage throughout the year, and the media continues to play an important role in supporting scrutiny, impact and accountability.

In April 2024, our follow-up report on aid funding for refugees in the UK was widely covered across print and broadcast media, such as the BBC, the Financial Times, the Guardian, the Sun, Sky News and Civil Service World. The lead commissioner was also interviewed on LBC and GB News. Also in April 2024, our follow-up report on UK aid to India was covered by the i, the Sun, the Daily Express, the Telegraph and the Independent, among others.

In May 2024, our UK humanitarian aid to Gaza information note also received strong media pick-up. The lead commissioner was interviewed by LBC and Channel 4 News, while other outlets covering the story included Al Jazeera, Politico, the Independent and Civil Service World.

Publication of the final three reports of ICAI’s third Commission was delayed by the May 2024 announcement of the general election. After the election, in July 2024, we published these remaining products: the UK aid for sustainable cities and The UK Department of Health and Social Care’s aid-funded global health research and innovation reviews, and the UK humanitarian aid to Afghanistan 2023-24 information note. These received coverage in outlets including the Guardian, the BMJ, the Herald, edie and Research Professional News.

In September 2024, we launched a public consultation to gather feedback from stakeholders on our work. This announcement was covered by Devex, the global development media platform, and featured in its daily Newswire.

In February 2025, we published the first report of ICAI’s fourth phase, How UK aid is spent, launched with an event at Chatham House. This was covered by media such as Sky News, the BMJ and the New

Internationalist. The Chief Commissioner was also interviewed on BBC Radio 5 live about the report and the government’s recently announced aid budget reductions.

We continued to use social media to promote our work and connect with our audiences. ICAI’s following on X (formerly Twitter) remained stable at around 7,000. Our LinkedIn following grew to 2,300, an increase of more than 50% on the previous year.

More than 47,000 people visited our website in the past year. Our most viewed web page was our UK aid to India review, first published in 2023 but followed up in 2024, with more than 8,000 views. The second most viewed was our UK aid to Ukraine review, published in April 2024, with around 6,000 views.

ICAI’s work plan April 2025 to March 2026

ICAI’s work plan for 2025-26 is published on our website. During the next year, we will be publishing reviews on UK aid for energy transition, UK aid to Sudan, management of the official development assistance spending target, and ending violence against women and girls.