ICAI Annual Report 2020-2021

Foreword

This Annual Report covers the second year of the Commission which was established in July 2019 – from April 2020 to March 2021. Normally, the second year sees a Commission reach ‘cruising altitude’ as new people and ways of working settle. But the turbulence of the previous year has, if anything, redoubled. While preparations for the UK’s exit from the EU took less of a toll on ICAI’s interlocutors in government than before, the global pandemic created new and far longer lasting challenges than foreseeable at the beginning of the year. Government staff working overseas returned in many cases to the UK, or worked from home, and ICAI commissioners, staff and consultants could not travel. We had to establish methods of doing our research remotely through the whole year – including ensuring that the voices of those affected by UK aid were integrated into the reviews. ICAI had to make allowances for the workload created by the pandemic on officials, which led to some delay and the challenges of organising hearings in Parliament reduced the options for use of ICAI’s reports for scrutiny.

Then in June 2020, the merger of the Department for International Development (DFID) – ICAI’s sponsor department – with the Foreign and Commonwealth Office (FCO) was announced, leading to uncertainty about the arrangements for Parliamentary scrutiny. In September, on the eve of the birth of the new department, the Foreign Secretary announced a review of ICAI. The review eventually gave strong backing to ICAI’s role in providing independent scrutiny, and we are still working with the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO) on the recommendations. All this meant that while ICAI continued with the work under way, there was considerable delay, with sign-off from the Committee of the new workplan not possible until January 2021. In effect, reaching cruising altitude was postponed.

But in the meantime, apart from continuing major themes of work like climate change in full reviews, such as the one on deforestation and biodiversity, ICAI used the uncertainty about the future to carry out some rapid timely pieces of work like the information note on Gavi, the Global Vaccine Alliance, and submissions to the Foreign Affairs Committee on the Integrated Review and Global Health Security. ICAI also built on the experience of the previous year in organising structured feedback to gain insights into impacts achieved through its work. It was reassuring to see, when we checked for the first time, our key performance indicator (KPI) on government action in response to our recommendations that about 80% of them saw an “adequate” response.

We have continued to face some challenges as the merger beds down, particularly with access to data for our reviews. At the time of writing, the FCDO has just taken an unprecedented step in suddenly reducing our annual budget, which, if implemented, will significantly disrupt our workplan. This is in the context of major cuts to the aid programme which are affecting the potential for learning from our reviews, as we saw in our follow-up review.

Nonetheless, the year of 2021-2022 is shaping up well. We have some very salient reviews with a rapid review on protecting aid from fraud, an information note which explains aid to China, and the alignment of the aid programme with the Paris climate change agreement among those published or forthcoming.

I’m very grateful to my fellow commissioners and secretariat, ICAI suppliers, and all the colleagues in HMG and Parliament who have worked constructively with us in a very difficult year.

Dr Tamsyn Barton,

ICAI Chief Commissioner

Highlights of 2020-2021

The focus of our reviews

The Independent Commission for Aid Impact’s (ICAI) programme of reviews is agreed each year with Parliament’s International Development Committee (IDC). We choose our topics by consulting with a wide range of stakeholders and by using four selection criteria: the amount of UK aid involved; relevance to the strategic priorities of UK aid; the level of risk; and the potential added value of an ICAI review. During the reporting period (April 2020 to March 2021), ICAI published eight reviews: three scored reviews; one rapid review; a companion report to a scored review; the annual follow-up review; and two information notes (see Table 1).

Table 1: ICAI 2020-2021 reviews and scores

| Review title | Review type | Publication date | Score |

|---|---|---|---|

| The UK’s work with Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance | Information note | June 2020 | Not scored |

| ICAI follow-up review of 2018-19 reports * | Follow-up | July 2020 | Not scored |

| The UK’s support to the African Development Bank Group | Full review | July 2020 | Green-amber |

| Assessing DFID’s results in nutrition | Results review | September 2020 | Green-amber |

| Sexual exploitation and abuse by international peacekeepers | Joint review | September 2020 | Not scored |

| The UK’s approach to tackling modern slavery through the aid programme | Full review | October 2020 | Amber-red |

| Management of the 0.7% ODA spending target | Rapid review | November 2020 | Not scored |

| UK aid spending during COVID-19: management of procurement through suppliers | Information note | December 2020 | Not scored |

*The follow-up review identified adequate progress being made for five reviews and inadequate progress on four reviews.

In 2020-2021, ICAI also produced three evidence notes. The first was to support the IDC’s inquiry into the effectiveness of UK aid.[1] It summarised the findings of previous ICAI reports, and examined areas such as the distribution of aid budgets across the government, the countries in which aid is spent, the learning processes used by aid-spending departments and the cross-government architecture overseeing aid spend. The second was to the Foreign Affairs Committee to support its inquiry into the government’s integrated review of foreign policy, defence, security and development.[2] ICAI’s evidence note drew on previous ICAI reviews, providing examples of where UK aid has enhanced the UK’s international leadership in tackling pressing global challenges, and identifying the key elements of successful global influence. The third was to support the Foreign Affairs Committee’s inquiry into the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office’s (FCDO) role in delivering the prime minister’s vision of a ‘new global approach to health security’. It drew on past ICAI reviews, summarising how UK aid supports global health security and identifying important issues for further consideration.

Key themes emerging from 2020-2021 reviews

A range of important themes has also emerged across our reviews.

Changing UK aid landscape

The UK aid landscape changed dramatically over the year. The Department for International Development (DFID) and the Foreign and Commonwealth Office (FCO) merged to become the FCDO, effective from September 2021. The COVID-19 pandemic caused major in-year changes to UK aid, driven by the need to mobilise resources for urgent pandemic response measures and the effects of a reduced UK gross national income on the aid budget. We extensively explored these issues and their implications for UK aid in our 2020-2021 reports.

In our review of the UK’s management of the 0.7% official development assistance (ODA) spending target in the pre-COVID period (to December 2019), we explored the complex mechanisms involved in reaching, but not exceeding, the annual aid target relating to inherent uncertainties in aid expenditure. We explored the coordination mechanisms set up to manage a shared target across multiple aid-spending departments, overseen by the former DFID and HM Treasury. We found that the system had effectively delivered the 0.7% aid target over the period from 2013 to 2019, principally through DFID’s role as ‘spender and saver of last resort’ and its ability to reschedule its core contributions to multilateral partners. Mostly, value for money risks associated with management of the target were appropriately managed. However, we questioned whether this system would be robust enough to handle major shocks, such as those that occurred in 2020. We therefore published a supplementary review of the management of the target in 2020 in May 2021. We will include this in the next annual report.

Our information note on the how aid-spending departments managed procurement challenges during the COVID-19 response in 2020 was the first of several assessments ICAI will undertake of different aspects of the UK’s aid response to the pandemic. We explored how the responsible departments had worked with implementing partners to minimise the effects of COVID-19 and related budget cuts on ongoing programmes, and to free up resources for the COVID-19 response.

We explored the process used to reprogramme nearly £800 million in central funding for the response to support humanitarian needs, medical research and vaccine supply relating to the pandemic. We found that the bulk of the resources during 2020 had come from the rescheduling of multilateral payments, and that the departments had worked flexibly with suppliers to mitigate the impact on bilateral programmes. However, we also found that limited transparency throughout this process had created significant uncertainty for suppliers.

The emergence of the COVID-19 pandemic has added to the significant challenges that aid-spending departments have faced due to changes in UK aid architecture over the past few years. We highlighted these effects in our report on the follow-up to reviews completed in 2018-2019. This report highlighted that changes in the government and in the leadership of departments (especially DFID), along with the temporary redeployments of staff to support Brexit preparations, had limited progress in implementing the recommendations from our 2018-2019 reviews. Considering this context, we found that the government’s response to ICAI’s recommendations was mostly positive, and that many improvements had been achieved, as teams and departments chose priorities carefully and worked, as the head of one DFID team described, “above and beyond”.

Learning from the handling of these aid-management challenges will be important in the coming period as aid-spending departments respond to the continuing effects of the pandemic and ongoing cuts to the aid budget. ICAI itself has not been immune to these changes in the UK aid landscape. It remains vital to achieving effective scrutiny that ICAI receives full cooperation from all government departments, that they are transparent in the information they provide for ICAI reviews and that ICAI’s work plan is fully funded. ICAI will continue to develop an increased focus on learning, especially in its annual follow-up review.

Leave No One Behind

The UN Sustainable Development Goals, agreed in 2015, include a commitment by the international community to ‘Leave No One Behind’ by addressing the needs of the poorest and most marginalised first. Following its endorsement of this agreement, DFID also introduced its own statement on the ‘leave no one behind’ principle.[3]

Our analysis of the UK aid programme in 2020-2021 reveals that significant efforts are being made to address this principle, but that challenges remain in ensuring consistent application across sectors and thematic areas.

Our results review of DFID’s work on nutrition found that DFID did not consistently reach the most marginalised within its target groups, including the chronically ill, and did not always fully understand their needs. However, the report identified some important examples of DFID’s good practice in targeting assistance at the poorest and most vulnerable people. DFID’s approach to this targeting has involved focusing on the most vulnerable countries, targeting the neediest regions within countries and through efforts to reach the most vulnerable households. As an example of effective targeting, the review identified Kenya, where DFID’s main nutrition programme – the Hunger Safety Net Programme – has targeted the four counties with the highest poverty levels and greatest vulnerability to drought and floods. The specific locations chosen for programme delivery were those where chronic food insecurity and rates of acute malnutrition exceeded emergency thresholds.

Our report on the follow-up to ICAI reviews published in 2018-2019 included an analysis of how effectively DFID has responded to concerns that its maternal health and infrastructure programmes had insufficiently targeted the poorest people. The report concluded that both programme areas had made progress under the ‘leave no one behind’ commitment. On DFID’s infrastructure programmes, it was reported that a new disability helpdesk had helped to better address challenges related to disability, and that the reorganisation of the DFID-funded Private Infrastructure Development Group had helped strengthen its emphasis on gender and safeguarding. On DFID’s maternal health programmes, the report noted that new centrally managed and country-level sexual health and family planning programmes had a stronger focus on the poorest women, with performance in achieving this targeting tracked through logframe indicators.

The information note on Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance, highlights some challenges that remain in prioritising reaching the poorest and most marginalised. It notes that Gavi has faced criticism over the years that it has not done enough to emphasise equity in its operations, and that coverage rates of its vaccines remain variable, particularly in countries with large birth cohorts. The information note highlights that, because of these concerns, the UK has made significant efforts to encourage Gavi to put more emphasis on supporting national immunisation systems that reach the poorest and most marginalised children. Gavi’s 2021-2025 strategy states that it will put “the last mile first” in its work, including investing at least £900 million in health system strengthening grants to help extend immunisation services to hard-to-reach communities. It remains to be seen whether the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic will compromise this commitment.

Gender issues

We have explored issues related to gender in several reviews. We have found that the UK aid programme can do more to analyse comprehensively and respond to gender issues, including ensuring that delivery partners give sufficient priority to the issue.

Our review on modern slavery found that the UK had played an important role in promoting global attention to this important but highly challenging area. The review found that vulnerability to modern slavery is highly gendered, with women and girls facing specific challenges relating to sexual exploitation and trafficking for domestic servitude. However, many of the UK’s aid programmes on modern slavery have not taken gender into account meaningfully. Though we found differences across the departments involved, many of the programmes of the Home Office and the former FCO have not collected gender-disaggregated data, which prevented meaningful gender analysis. We found former DFID programmes to have incorporated gender analysis into their design and monitoring arrangements more effectively.

Our review on the African Development Bank Group (AfDB) found that the bank has increased its focus on gender issues, which has helped to promote stronger alignment with UK development goals. Its efforts included adopting a gender strategy for 2014-2018, appointing a special envoy on gender between 2014 and 2016, producing country gender profiles and supporting significant new programmes focused on women’s economic empowerment. However, the review also highlighted how the AfDB has faced challenges in taking its gender strategy forward, with the budget for the strategy delayed by two years, insufficient engagement with staff to support its rollout and variable quality of gender-related analysis.

Although our review of DFID’s work on nutrition found that the department has worked intensively to target the poorest women through its programmes, it identified some weaknesses in the monitoring of gender impacts. The review found that, for almost a third of its nutrition results, beneficiaries’ gender was not reported due to weaknesses in the monitoring systems of partner governments and of DFID itself.

Fragile and conflict-affected states

The considerable development challenges facing fragile and conflict-affected states (FCAS) have attracted growing attention from the international development community in recent years. As a result, ICAI has continued to explore how effectively the UK aid programme has targeted these countries and contributed to addressing the challenges they face.

In our review of the work of AfDB, we noted its increasing emphasis on addressing issues related to conflict and fragility, supported by its Strategy for Addressing Fragility and Building Resilience 2014-2021, its Post-Conflict Country Facility and its analytical and diagnostic work (including applying a new Country Resilience and Fragility Assessment tool and in-depth country and regional fragility assessments). However, this review also concluded that AfDB is struggling to have an impact in FCAS, mainly due to the more challenging policy and institutional environment, challenges in recruiting the right mix of skilled staff for field offices in fragile states and a variable level of effort to pursue this agenda, including amongst the bank’s senior leadership.

Our review of DFID’s nutrition programming highlighted how the department’s Nutrition Position Paper identified the importance of targeting people in FCAS. The review also found that, guided by its position paper, DFID’s nutrition work has put emphasis on these states; 49% of the total results of its nutrition programmes reported in ‘high fragility’ countries and 37% were in ‘fragile countries’. As the paper noted, this focus is consistent with analysis, suggesting that malnutrition and wasting are much more prevalent in FCAS.

An important aspect of the international response to the challenges faced by FCAS is the need to ensure that international peacekeeping forces treat local people appropriately and avoid sexual exploitation and abuse. Our review of the UK’s response to this challenge found that this persistent issue had been neglected for some time, but was now receiving greater attention from the UK, which has been central to efforts to drive reforms at the UN, and has also supported relevant training of African peacekeepers. However, we found that there is limited evidence available so far on how effective these activities have been, and that UK aid programmes have placed limited emphasis on the needs of survivors.

[2] Effectiveness of UK Aid: Enquiry, International Development Committee, 16 July 2020 (link).

[3] The FCDO and the Integrated Review, Foreign Affairs Committee, date unknown (link).

[4] Leaving no one behind: Our promise, DFID and FCDO, 6 March 2019, link.

ICAI functions and structure

This chapter sets out the structure and functions of the Independent Commission for Aid Impact (ICAI).

ICAI’s structure and functions

ICAI was established in May 2011 to scrutinise all UK official development assistance (ODA), irrespective of spending department. ICAI is an advisory non-departmental public body sponsored by the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO). It delivers its programme of work independently and reports to Parliament’s International Development Committee (IDC).

Our remit, re-confirmed by FCDO in December 2020 (see below for more detail), is to provide independent evaluation and scrutiny of the impact and value for money of UK ODA. To do this, ICAI:

- carries out a few well-prioritised, well-evidenced and credible thematic reviews on strategic issues faced by the UK government’s aid spending

- informs and supports Parliament in its role of holding the UK government to account

- ensures it makes its work available to the public.

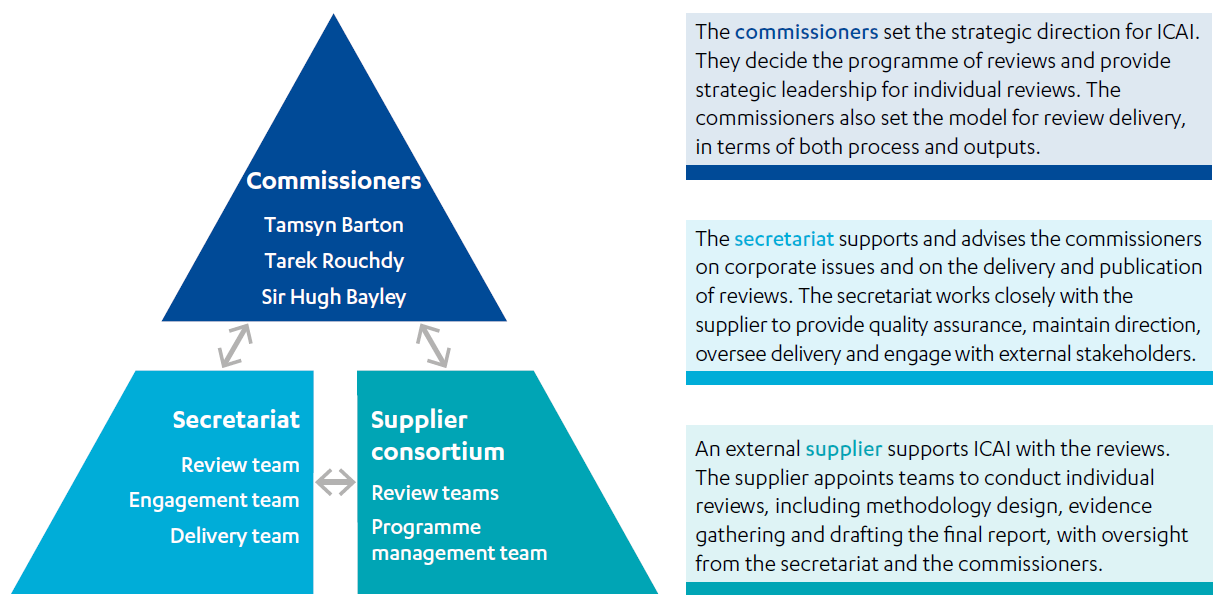

ICAI is led by a board of independent public appointees (the commissioners) who are supported by a secretariat and external suppliers. These three pillars – commissioners, secretariat and suppliers – work closely together to deliver reviews. Figure 1 summarises the roles and responsibilities of the three pillars.

The ICAI team

Dr Tamsyn Barton, ICAI’s chief commissioner, leads the board of commissioners. ICAI’s other commissioners are Sir Hugh Bayley and Tarek Rouchdy. The commissioners’ biographical details are on the ICAI website.

Ekpe Attah leads ICAI’s secretariat of ten civil servants. They are responsible for review management (working alongside the external supplier), supplier contract management, financial control and corporate governance, and communications and engagement. The secretariat’s base is Gwydyr House, Whitehall, but staff have been mainly working from home during the reporting period due to COVID restrictions.

ICAI was supported during 2020-2021 by an external supplier consortium led by the specialist international development consultancy, Agulhas Applied Knowledge, which also included Ecorys, ODI and INTRAC (DAI and HEART also provided services outside ICAI’s main external supplier contract).

Figure 1: High-level roles and responsibilities (accessible version)

The FCDO review of ICAI

In August 2020, the foreign secretary announced an FCDO review of ICAI, seeking to ensure its remit, focus and methods were effectively scrutinising the impact of UK aid spend, in line with the aims of the new department. The review, published in December 2020,[5] found that ICAI provides strong external scrutiny of UK ODA and offers excellent support to Parliament in holding the government to account, and should continue to ensure transparency and value for money in aid spending. We welcome the FCDO’s assurances that ICAI will continue to operate independently in setting and delivering its programme of work.

The review made several recommendations as to how ICAI can do more to help the government deliver the best possible impact for UK aid, which we are – with FCDO – working through to determine the best way of implementing them. They include an even greater focus on enabling FCDO to learn from ICAI reviews.

[5] Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office’s review of the Independent Commission for Aid Impact, FCDO and ICAI, 16 December 2020, link.

Corporate governance

The Independent Commission for Aid Impact’s (ICAI) commissioners, who lead the selection process for all reviews and lead the work on each review, were appointed after a recruitment process regulated by the Commissioner for Public Appointments. They hold quarterly board meetings, the agendas and minutes of which are published on ICAI’s website.

ICAI’s primary governance objective is to act in line with the mandate agreed with the (then) secretary of state for international development, set out in our Framework Agreement.[6] Following the creation of The Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO) and its review of ICAI (referred to in chapter 2) we are working to agree a new framework agreement with the department.

Risk management

The ICAI secretariat maintains a corporate risk register which identifies and monitors ICAI’s corporate risks. The commissioners reviewed this monthly over the past year because of the uncertainty caused by the pandemic and the potential implications for ICAI of the merger of the Foreign and Commonwealth Office (FCO) and the Department for International Development (DFID). ICAI’s risk register includes an assessment of gross and net risk, mitigating actions and assigned risk owners. It includes risks relating to the operating environment (in particular, currently, the impact of COVID-19) and more specific risks inherent to the production of ICAI reviews.

Annual audit

As set out in the Framework Agreement, ICAI is subject to an annual audit, undertaken by FCDO’s Internal Audit and Investigations Department. This is to provide assurance to ICAI and FCDO on the effectiveness of our systems and processes in place to manage risk and deliver objectives.

The 2020 audit examined how ICAI:

- achieves its strategic objectives through the delivery of reviews (ie how effectively our reviews support our theory of change)

- ensures the quality of its reviews through quality assurance processes and oversight of its supplier

- reports against its work plan, including the agreement and reporting of its key performance indicators (KPIs)

- embeds risk in its approach to delivery, performance and quality assurance to achieve its strategic objectives.

While identifying risks to ICAI’s ability to deliver our work programme, relating to the pandemic and the increased number of spending departments in official development assistance (ODA), the audit report assessed our controls to be designed and operating effectively to manage risk within appetite. In particular, the report noted ICAI had recently reviewed its KPIs and updated its theory of change (as described in our 2019-2020 annual report), as well as updating our methodology for selecting reviews to ensure that we do this in a consistent and transparent manner.

Conflict of interest

ICAI takes conflicts of interest, both actual and perceived, extremely seriously. Our independence is vital for us to achieve real impact.

We publish our conflict of interest and gifts and hospitality policies on our website, and update the commissioners’ conflict of interests register every six months. We maintain an internal register for secretariat staff and review potential conflicts of interest for all supplier team members before beginning work on reviews.

We manage any conflict of interest transparently and make decisions on a case-by-case basis. The specialist nature of our work, and the requirement for strong technical input, means that we need to weigh the risk of a possible or perceived conflict with the need to ensure high quality and knowledgeable teams conduct our reviews.

Whistleblowing

ICAI has limited capacity to investigate concerns raised by the public, and it is not part of our formal mandate. Our whistleblowing policy is on our website.

In line with the policy, if we receive allegations of misconduct, we offer to put the complainant in contact with the relevant department’s investigations team, if appropriate, or with the National Audit Office’s investigations function.

Safeguarding

ICAI complies with FCDO safeguarding and reporting standards. There have been no reports this year under our safeguarding policy.

[6] The Framework Agreement is the document that sets out the principles and ways of working for ICAI’s relationship with its sponsoring department.

Financial summary

This chapter sets out:

- the overall financial position of the Independent Commission for Aid Impact (ICAI)

- ICAI’s work cycle

- expenditure for the financial year period April 2020 to March 2021

- spending plans for the forthcoming year.

Overall financial position

ICAI has a budget of £15.077 million for the four-year period July 2019 to June 2023 (ICAI Phase 3). In the financial year April 2020 to March 2021, ICAI spent £3.122 million (£2.228 million on programme and £894,000 on administration and front-line delivery). This means that the total Phase 3 spend to the end of March 2021 was £5.643 million. Programme spend this year was lower than the original forecast because of the impact of the pandemic delaying reviews and the uncertainty about future parliamentary arrangements for signing off ICAI’s work programme following the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO) merger.

ICAI’s work cycle

ICAI’s pipeline achieves its mandate of delivering a few well-prioritised, well-evidenced and credible thematic reviews on strategic issues faced by the UK government’s aid spending. This means managing a rolling programme of reviews which can span financial reporting years. Consequently, costs payable to the supplier in any one financial year cover both products published in that year and initiation costs for reports due for publication the following year.

Expenditure from April 2020 to March 2021

Table 2 provides a breakdown of expenditure for the period 1 April 2020 to 31 March 2021.

Table 2: ICAI expenditure April 2020 to March 2021

| Area of spend | Actual expenditure April 2020 to March 2021 (£k) |

|---|---|

| Supplier costs | 2,189 |

| External engagement activities | 39 |

| Total programme spending | 2,228 |

| Commissioner honoraria | 212 |

| Commissioner expenses | 0 |

| Commissioner country visit travel, accommodation and subsistence* | -4 |

| FLD (front-line delivery) secretariat staff costs | 306 |

| FLD staff expenses | 1 |

| FLD staff training | 3 |

| Total FLD spending | 518 |

| Admin secretariat staff costs | 327 |

| Admin secretariat training | 1 |

| ICAI accommodation and office costs | 48 |

| Total administrative spending | 376 |

| TOTAL SPEND | 3,122 |

*ICAI actually spent around £3,000 on Commissioner training and travel in this financial year but adjustments arising from the previous year have resulted in a credit in this area of spend.

ICAI spends most of its budget on supplier costs. In 2020-2021, these supplier costs (programme spend) were £2.189 million. This included the cost of reviews and information notes, project management, communication of the review portfolio, preparatory work for future reviews, some costs associated with developing new methods for Phase 3, and consulting with stakeholders to evaluate ICAI’s impact to inform future work plans.

As explained above, some of this cost is for initiating work on reviews for publication after 1 April 2021 and into Year 3 of Phase 3 to maintain the pipeline of review production. Table 3 sets out the total supplier costs for each review actually published between April 2020 and March 2021. These costs are paid over several financial years and not solely in the year of publication.

Table 3: Total supplier cost for each review published April 2020 to March 2021

| Review | Cost |

|---|---|

| ICAI follow-up review of 2018-19 reports | £187,499 |

| The UK’s work with Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance | £29,446 |

| The UK’s support to the African Development Bank Group | £296,706.45 |

| Assessing DFID’s results in nutrition | £348,004 |

| Sexual exploitation and abuse by international peacekeepers* | £342,920 |

| The UK’s approach to tackling modern slavery through the aid programme** | £313,027 |

| Management of the 0.7% ODA*** spending target | £106,474 |

| UK aid spending during COVID-19: Management of procurement through suppliers | £37,646 |

| Total | £1,318,802 |

* This was an accompanying report to the ICAI review of the Preventing Sexual Violence in Conflict Initiative, published in January 2020. The figure shown is the supplier cost for both reviews. This cost was also declared in last year’s annual report.

** International Development Committee (IDC) hearing took place in April 2021.

*** Official development assistance

The variation in the costs of ICAI reviews is driven by:

- the breadth of the topic under review

- the methodological approach required to provide robust and credible scrutiny of the topic (including whether and how many country visits may be required and the extent of citizen engagement research, in this year both done remotely because of COVID restrictions. Remote research has so far not been significantly cheaper than in-person research).

We will continue to manage ICAI’s administration budget carefully to ensure that all expenditure contributes directly to meeting ICAI’s objectives.

Programme spend in the 2020-2021 financial year has been lower than expected because of the constraints resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic and the uncertainty about parliamentary arrangements for signing off the work programme. We have forecast a considerable increase in programme spend in 2021-2022, to £3.3 million.

Spending plans for 2021-2022

FCDO has informed ICAI, without prior consultation with ICAI or the IDC, that ICAI’s allocated programme budget for 2021-2022 is approximately 15% less, at £2.8 million, than ICAI requires to deliver the work programme it had previously agreed with the select committee. As an arm’s length body that needs to be operationally independent of the government, ICAI firmly believes decisions on how to profile its spend within its overall four-year budget ceiling are for ICAI commissioners to make. It is clear from published correspondence[7] that the IDC shares ICAI’s views. ICAI remains committed to progressing the work plan as originally intended, but if FCDO continues to restrict ICAI’s budget as indicated, this may limit ICAI’s ability to complete its full programme to the original timescales.

[7] Correspondence, International Development Committee, link.

ICAI’s performance

This chapter sets out performance during the year against the Independent Commission for Aid Impact’s (ICAI) key performance indicators (KPIs) for 2020-2021.

Table 4: Performance summary 2020-2021

| Key performance indicator | Outcome |

|---|---|

| Proportion of ICAI recommendations accepted or partially accepted by the government | 100% of recommendations accepted or partially accepted |

| Proportion of ICAI recommendations actioned by the government* | 79% actioned |

| Change in government practice due to ICAI reviews | Independently verified through assessment of ICAI’s impact (see below) |

| International Development Committee (IDC) satisfaction with ICAI | Parliamentary stakeholders, including IDC, regard ICAI as key to supporting Parliament’s scrutiny role |

| ICAI communications and engagement activity | ICAI developed new communication tools, spoke at seven external events, seven pre-publication focus groups and four learning events |

| Media and social media coverage | ICAI’s social media channels continue to grow |

| Budgetry control | ICAI operated within agreed budget |

* The proportion of ICAI recommendations from 2018-19 reviews actioned by the government, assessed during last year’s annual follow-up process. The proportion of recommendations actioned by the government from 2019-20 reviews will be included in next year’s annual report (for the period 2021-2022).

Independent assessment of ICAI’s impact

In 2019, ICAI commissioned an unpublished report to examine our impact, which involved interviews with parliamentary, government and non-government stakeholders. We refreshed this report in summer 2020.

The updated report found that ICAI contributes to improvements through providing new information and evidence for soliciting support for particular activities, adding momentum to changes underway, adding legitimacy and leverage with new approaches, creating new relationships and bringing new ways of thinking. Longer term or less tangible impacts, such as contributing to sector debates, are also widely seen as important.

As illustrated in more detail below in the section on working with the IDC, the report also found that parliamentary representatives, parliamentary officials, and current or former elected representatives see the relationship between ICAI and the IDC as working well. They see ICAI is providing important evidence for Parliament, which it can use to hold the government to account. Furthermore, the report found parliamentary stakeholders felt coordination with ICAI had increased and improved over the last year.

Government responses to ICAI reviews

The government has six weeks to publish a response to an ICAI review. By the end of March 2021, we had received responses from the government for all five of our reviews published in 2020-2021. The government does not formally respond to information notes. To date, the government has accepted or partially accepted all ICAI’s recommendations.

Finances

ICAI continues to deliver within budget. In 2020-2021, ICAI spent less than anticipated because of delays to the work plan caused by a combination of the pandemic and the disruption of the Foreign and Commonwealth Office (FCO) and the Department for International Development (DFID) merger. ICAI is planning a full and ambitious programme of work in 2021-2022. We will continue to scrutinise closely all areas of expenditure to ensure operational efficiency.

Working with the International Development Committee

ICAI’s work with the International Development Committee (IDC) plays a vital role in delivering real improvements to how UK aid is spent, through robust and effective scrutiny of our reviews and other evidence.

Commissioners took part in seven evidence sessions with the committee during the reporting period, though remotely due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

In June 2020, Tamsyn Barton gave evidence to the committee’s Humanitarian Crises Monitoring inquiry, drawing on ICAI’s recent information note about the UK’s work with Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance. In July 2020, she appeared before the ICAI subcommittee, chaired by Theo Clarke MP, to discuss the country portfolio review of UK aid to Ghana. In September 2020, both Tamsyn Barton and ICAI’s head of secretariat, Ekpe Attah, appeared before the full committee, chaired by Sarah Champion MP, to give evidence on last year’s annual report and accounts. This committee also took evidence in November from Tamsyn Barton on ICAI’s reviews looking at the Preventing Sexual Violence in Conflict Initiative and sexual exploitation and abuse, as part of the committee’s wider inquiry into this issue.

In November 2020, ICAI Commissioner Sir Hugh Bayley gave evidence to the subcommittee on ICAI’s information note mapping out how the UK tackles anti-corruption and illicit financial flows. Tamsyn Barton did a further two hearings – in December 2020 on the UK’s support for the African Development Bank Group (AfDB), and in February 2021 on ICAI’s review of the results claimed by the UK for its nutrition programmes.

During this period, the committee also took evidence in written format for a further two ICAI reviews – full written evidence submissions from ICAI and the government on ICAI’s review of the Newton Fund, and correspondence with the government in relation to ICAI’s review of How UK Aid Learns. The relevant materials are available on the IDC’s website.

Besides its work on reviews and information notes, ICAI also generated three pieces of ad hoc evidence to support ongoing select committee inquiries. We provided the Foreign Affairs Committee with written evidence on global health security in January 2021 and on the global influence of UK aid in July 2020 as part of the committee’s scrutiny of the Integrated Review, and produced a further submission for the IDC on the effectiveness of UK aid in May 2020.

ICAI continues to work with Parliament to consider how it can continue to support its scrutiny of government aid spend.

External engagement

Despite the ongoing limitations caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, ICAI has continued to prioritise strategic engagement with its key audiences – the government, Parliament, the aid sector and the public – to drive maximum uptake and impact for its reviews. Positive and proactive engagement has continued to increase, with aid sector stakeholders regularly consulted as appropriate at all stages in the review cycle – from design and scoping through to post-publication – while a new regular newsletter has helped to bring ICAI’s work to more audiences.

ICAI has also continued to improve how it communicates externally. Besides the existing video interviews with commissioners, ICAI introduced animated video summaries for social media to make its reviews more accessible to a wider audience. Completed in spring 2021, the ICAI website underwent a comprehensive restructure and improvement to ensure accessibility for all.

Events

ICAI endeavours to run a full programme of external events to maximise the impact of its work and increase understanding and learning around its findings. Although the COVID-19 pandemic meant events had to switch to a remote format, ICAI worked successfully with partners to organise external events during the past year, covering seven different review topics. It also arranged a variety of evidence-gathering focus groups, pre-publication briefings and external speaking opportunities.

In September 2020, ICAI teamed up with the ODI to host a high-profile event on the AfDB review. Panellists from ODI, the University of Nairobi and King’s College London joined Tamsyn Barton for a wide-ranging discussion about the UK’s support for the bank, with attendees from around the world. A similarly successful partnership event with a global appeal was held in November with the British Foreign Policy Group. The event focused on the UK’s work to tackle sexual violence in conflict, exploitation and abuse, with a panel including Baroness Arminka Helic, Dr Maria Al Abdeh of Women Now for Development and the Sunday Times’s Christina Lamb.

On a smaller scale, but no less important, ICAI worked with British Expertise International to host learning events on the anti-corruption information note, the modern slavery review, and the results review of UK aid’s nutrition programmes. We thank the panellists from the government, academia and the aid sector for helping to make the events such a success. A further event organised with the All Party Parliamentary Group for Africa and the Royal African Society, discussing a range of recent reviews, helped to raise ICAI’s profile among parliamentarians.

Commissioners and ICAI’s specialist reviewers also took part in six external speaking engagements and workshops, including three in relation to the modern slavery review. Nine evidence-gathering focus groups and pre-publication briefings with stakeholders covered topics such as ICAI’s information note on COVID-19 procurement, and its rapid review of how the government managed the 0.7% aid-spending target between 2013 and 2019.

Media and digital

ICAI’s reviews generated media coverage throughout the year, and the media continues to be an important channel in supporting scrutiny, impact and accountability.

In October 2020, ICAI’s review of the UK’s approach to tackling modern slavery through the aid programme resulted in 14 pieces of coverage, including in the Telegraph, the Times, Daily Mail, Reuters and the Business Standard in Bangladesh, with a combined reach of over a billion. Also generating coverage across sector and national press, ICAI’s December information note shedding light on how the government prioritised the aid programme in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, and its November rapid review of the government’s management of the aid-spending target. Meanwhile, the news in June 2020 about the government’s decision to merge DFID with FCO resulted in extensive media, parliamentary and sector speculation about the implications for ICAI. Confirmation over the August Bank Holiday weekend from the foreign secretary that ICAI would continue to scrutinise UK aid sparked high levels of online and media engagement.

ICAI’s social media channels continue to grow, with a year-on-year increase in Twitter followers of 8% from the previous year to nearly 6,700, and a 50% increase in our LinkedIn audience (from 421 to 632) after we began using the channel to communicate externally early last year. ICAI’s website also saw growth, with 3,740 unique review downloads and views, a 23% increase on the previous, shorter annual report year.

ICAI’s work plan April 2021 to March 2022

We update our work plan for April 2021 to March 2022 throughout the year, which is available on our website. Although the COVID-19 pandemic is having a considerable impact on how we work, ICAI will continue to scrutinise UK aid programmes during this period, in line with our mandate and at a time when, given fiscal constraints, monitoring public spending is as important as ever. However, we keep our work plan under constant review, working with Parliament, the departments we scrutinise, and other stakeholders as necessary. We have also adapted our research methods to allow for remote working approaches, following official advice at all times. The safety of all those involved in ICAI reviews is our highest priority.