ICAI follow-up review of 2019-20 reports

Letter from the chief commissioner

This is the second follow-up report where I have been the lead since I became chief commissioner in January 2019 and it has been a mixed experience this year. On the one hand, we have seen impressive improvements as a result of ICAI’s engagement with organisations delivering UK aid – we are featuring two positive ‘learning journeys’ this year, one with the UK government’s Development Finance Institution, CDC, and the other with the Department of Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy’s research programmes. On the other hand, we have seen that the turbulence created by COVID-19, and two associated processes of major cuts to programmes, together with the merger of the Foreign and Commonwealth Office with the Department for International Development, has set back progress we could see underway last year.

A cause for concern in this context has been a reduction in open engagement in the follow-up process. This year, we were unable to find out through the usual systems about the continuation of key programmes, and to access documentary evidence in many cases. It may be that this is a result of overload at an exceptionally busy time. Transparency is key to learning, so given the increased focus on ICAI’s role in enabling UK aid to learn, it is more important even than before.

Given inadequate progress in relation to all the three reviews being followed up this year, we will return next year in the hope of seeing a more encouraging picture.

Dr Tamsyn Barton, Chief Commissioner

Executive summary

This report presents the results of our follow-up exercise to assess progress made by aid-spending government departments and funds on addressing Independent Commission for Aid Impact (ICAI) recommendations. It covers seven ICAI reviews in all: we follow up on three reviews published in the last annual review cycle from July 2019 to June 2020, and we return again to four reviews published in previous cycles in order to address outstanding issues from last year’s follow-up exercise.

Table 1: Reviews covered in this follow-up

| Reviews from 2019-20 subject to follow-up | |

|---|---|

| How UK aid learns September 2019 | September 2019 |

| The UK’s Preventing Sexual Violence in Conflict Initiative | January 2020 |

| The changing nature of UK aid in Ghana | February 2020 |

| Previous reviews with outstanding issues that are being revisited | |

| Achieving value for money through procurement: DFID’s approach to value for moneythrough tendering and contract management (“Procurement 2”) | September 2018 |

| Assessing DFID’s results in improving Maternal Health | October 2018 |

| CDC’s investments in low-income and fragile states | March 2019 |

| The Newton Fund | June 2019 |

Scoring the government’s progress

Last year, we introduced a scoring element to the follow-up exercise. We provide a score for the reviews we follow up for the first time, but not for the outstanding issues from previous years (see Table 1 above). We score the response to ICAI’s recommendations as adequate or inadequate, illustrated by a tick or a cross. An inadequate score results from one or more of the following three factors:

- Too little has been done to address ICAI’s recommendations in core areas of concern (the response is inadequate in scope).

- Actions have been taken, but they do not cover the main concerns we had when we made the recommendations (the response is insufficiently relevant).

- Actions may be relevant, but implementation has been too slow (the response is insufficiently implemented) and we are not convinced by the reasons for the slowness.

We will return to issues where the government response has been inadequate, either as outstanding issues in the next follow-up or through future reviews.

Overview of the response to ICAI’s recommendations

The period covered by this follow-up review saw enormous change in the UK aid landscape. The COVID-19 pandemic caused the UK economy to contract, which led to a reduction of £712 million in UK aid spending. Implementation of aid programmes was disrupted by pandemic restrictions while £1.39 billion in UK aid was shifted towards the COVID-19 response during the course of 2020.

In the midst of this, the Department for International Development (DFID) and the Foreign and Commonwealth Office (FCO) were merged to form the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO), which led to a flurry of reorganisation and review of objectives.

Then, in November 2020, the decision was made to reduce UK official development assistance (ODA) spending from 0.7% to 0.5% of gross national income, leading to further large cuts in UK aid. The practical implications of these cuts, as well as of the outcomes of the Integrated Review of Security, Defence, Development and Foreign Policy (published on 16 March 2021), were still being worked through when the evidence gathering for this follow-up review came to an end in April 2021, with many organisational and budget allocation decisions still to be made. In this period of flux, interacting with the relevant government departments and teams has at times been challenging. Responses to ICAI requests were sometimes slow and information necessary to assess progress on its recommendations was sometimes not provided. It is to be hoped that this is a temporary situation, but overall there has been a reduction in transparency and openness in FCDO’s engagement with the ICAI follow- up compared to previous years. Concerns about transparency of UK ODA emerged in several, but not all, of this year’s follow-up exercises:

- How UK aid learns: Due to COVID-19 constraints, the cross-government working group on transparency in aid management was paused and it is not clear when it will be reconvened or whether FCDO will use the relaunched Aid Management Platform to keep the same standards of transparency, or potentially improve on them, extending them to all departments.

- The Ghana country portfolio and PSVI reviews: Very little documentary evidence was provided when requested by ICAI, making it difficult to verify findings.

- Maternal health: Long-awaited key strategic documents that would have provided clarity on UK aid’s objectives and plans for improving maternal health remain in draft form after long delays, and drafts have not been shared with ICAI. A redacted delivery framework for the draft Ending Preventable Deaths Action Plan was provided.

- Newton Fund: While the Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy (BEIS) was very open in supporting the ICAI follow-up, during the course of the follow-up exercise we heard that the deliberations and decisions on ODA funding cuts – which largely took place within FCDO, rather than BEIS – were made without consultation with stakeholders in the research community, and with little openness on how decisions were reached – leaving Newton Fund and other ODA research funding grantees in a prolonged situation of uncertainty about the future of their projects.

As can be seen from the above, the situation was not uniform. BEIS and CDC worked closely with ICAI and provided ample documentary evidence as well as access to interviews to back up and triangulate findings. In the case of CDC, the ICAI review team was able to review a very wide range of documents provided by CDC and to interview over 30 CDC staff members, who made themselves available in a timely way. For the How UK aid learns follow-up, there were widely differing responses from government departments to ICAI’s requests, ranging from a lack of engagement to an enthusiasm for sharing improvements, challenges and learning.

Learning journeys – tracing improvements in aid delivery through the ICAI review and

follow-up cycle

As the structure of the new FCDO and changes to the scaled-back UK aid programme take shape in 2021, there should be a renewed focus on transparency and accountability in UK aid. An open and constructive relationship with FCDO and other aid-spending departments lies at the base of ICAI’s oversight role and its ability to work with government to foster learning and improve the delivery of UK aid. We present two ‘learning journeys’ focused on CDC and BEIS, to show the strong results that accrued from working through the challenges identified in ICAI’s reviews, with ICAI as a critical friend along the way.

CDC’s investments in low-income and fragile states: The original ICAI review, published in March 2019, found that CDC had not done enough to maximise the development impact of its UK aid investments. ICAI’s first follow-up of its recommendations (published in July 2020) concluded that although CDC had made valuable progress in a number of areas – including setting clearer development impact goals, better monitoring of their delivery and improved learning – the pace and depth of change was not yet sufficient. CDC responded positively and rapidly to ICAI’s second follow-up exercise, which meant that there was an opportunity to design a thorough and extended follow-up process. After three years of close engagement between CDC and ICAI, this year’s follow-up review has been able to conclude that CDC’s investment decisions now address development impact throughout its investment cycle and consideration of impact is driving active management of investments to a much greater extent.

The Global Challenges Research Fund (GCRF) and the Newton Fund: BEIS went from spending £270 million in ODA funds in 2014 to just over £1 billion in 2020, mainly through two large development research funds reviewed by ICAI in September 2017 (GCRF) and June 2019 (the Newton Fund). ICAI found that many key aid management practices were inadequate and that the funds did not have sufficient strategies and mechanisms in place to maximise development impact and ensure good use of UK ODA. The original response from BEIS was to query ICAI’s understanding of the nature of research as much as the department’s own understanding of ODA management. However, over subsequent years, and as ICAI followed up both funds two years in a row, this initial reaction gave way to what became an impressive set of changes: the creation of a robust joint governance structure for the two funds, safeguards at both project and portfolio level to ensure ODA eligibility and attention to development impact, a strong monitoring, evaluation and learning (MEL) framework, and improved data collection and transparency on the delivery of the funds’ activities. ICAI may have helped stimulate the significant reforms to ODA management in BEIS, but momentum now comes from the inside. In the current funding environment, the future of both funds is in the balance, but BEIS’s achievements in improving ODA management should continue to increase the impact and value for money of any ODA-funded research it funds in future.

Outstanding issues

ICAI was not able to conclude that there had been adequate progress for the three reviews followed up this year. Table 2 (below) provides the headline findings and score for each of the three. Contextual constraints and challenges, combined with the FCDO merger, meant that much of the action taken in response to ICAI’s recommendations is at an early stage or has been lost over time. In the current situation of cuts and reprioritisation of UK ODA spending, there is a risk that gains will not be sustained. We will therefore come back to all three reviews next year as outstanding issues. In addition, we will return once more to one of the four outstanding issues, the maternal health review. The headline findings for the four outstanding issues are provided in Table 3.

Table 2: Overview of progress and scoring for individual reviews

| Our assessment of progress on ICAI recommendations | Score |

|---|---|

| How UK aid learns | |

| A reasonably good response to ICAI’s recommendations and underlying concerns, particularly in the early stages after publication. However, contextual challenges and the FCDO merger have led to progress stalling, particularly on strengthening transparency. There is potential for FCDO to take on a positive coordination and standard-setting role across government, and for transparency to be increased, but until the future of the Aid Management Platform is clear, and FCDO evaluation plans and the new UK aid strategy are in place, we will not know if this potential will be realised. We therefore score the response as inadequate and will return to this review next year. | Inadequate |

| The changing nature of UK aid in Ghana | |

| There has been reasonable progress on some of the issues raised by ICAI’s review. But overall, a combination of an initially vague response to some of ICAI’s recommendations, delays due to contextual challenges, and a reluctance to share documentation or briefings on ongoing strategic work by FCDO such as the Africa strategy and the delivery framework, means that it has not been possible to verify reported improvements. We have therefore scored the response to ICAI’s recommendations as inadequate and will return to this review next year. | Inadequate |

| The UK’s Preventing Sexual Violence in Conflict Initiative | |

| Important strategic work is under way which could amount to a strong response to ICAI’s recommendations and underlying concerns. However, since ICAI has not seen the planned PSVI strategy, key performance indicators or MEL framework, or received information on the budget for PSVI-related activities, we are not yet able to conclude that the government response has been adequate. We will therefore return to this review as an outstanding issue next year. | Inadequate |

Table 3: Overview of progress on outstanding issues from earlier reports

| Outstanding issues | Our assessment of progress since last year |

|---|---|

| CDC | |

| This second follow-up allowed a fuller assessment of CDC’s work to strengthen the potential for development impact of its investments in low-income and fragile contexts. | There have been important improvements to CDC’s approach to achieving development impact. CDC’s investment decisions now emphasise development impact much more effectively, CDC’s new monitoring and evaluation mechanisms are being applied and are feeding into learning, and CDC is now more focused on learning. CDC has made some progress with expanding its country presence, collaborating with FCDO’s overseas network and communicating the rationale behind its investment approach for the Growth Portfolio, but its response in these areas has been less strong. Overall, we are pleased to see that actions reported last year have been sustained and progress has been made. |

| Maternal Health | |

| ICAI decided last year to conduct a second followup if the Health Systems Strengthening (HSS) Position Paper and the Ending Preventable Deaths (EPD) Action Plan were still not published. | Overall, FCDO has continued to pursue a coherent set of activities related to maternal health. In the past year, the Sexual and Reproductive Health and Rights team took a strong lead on the agenda, developing guidance, organising learning activities, and engaging in relevant international forums where they pushed for UK priority areas. However, the HSS Position Paper and EPD Action Plan – key documents for the transparency and accountability of FCDO’s programming – remain unpublished. Meanwhile, flagship programmes are being significantly scaled back, and the future direction of maternal health programming is not clear. As a result, we will return to this review again during next year’s follow-up. |

| Procurement 2 | |

| The original ICAI review as well as last year’s followup noted that the lack of an effective contract management regime and proper training has had demonstrable negative effects on programming. | There have been significant improvements on instituting a robust contract management regime. FCDO has appointed a senior responsible officer for contract management at the appropriately senior level of the chief commercial officer, reporting to the director general, corporate. There is now a formal contract management regime, underpinned by appropriate guidance and support at senior level. The regime includes appropriate adaptive contract management techniques, to ensure that supplier accountability is balanced with the need for innovation and agility in pursuit of development results. Training efforts are on an upward trajectory, but will need to be further sustained over the coming years to ensure that FCDO achieves the significant uplift in expertise and capability it needs to improve contract management. |

| Newton Fund | |

| Last year’s follow-up found that BEIS had not interacted with the underlying concerns of ICAI’s review on the Newton Fund’s attention to development impact and a funding model that ties almost all UK ODA to UK institutions. | Operationally, the Newton Fund has been transformed. Its policies and practices differ significantly from when ICAI first conducted its performance review. The changes that have been made to improve the Fund’s approaches to ODA compliance and assurance, and the changes to how the Fund monitors, evaluates and learns, are very positive and indicative of a significant amount of work. That said, at the strategic level the fundamental design of the Newton Fund remains the same. For ICAI’s concerns around primary purpose and tied aid to be addressed in a possible future iteration of the Newton Fund, BEIS would need to revisit the model of the Fund, as has also been recommended by the International Development Committee. |

Introduction

The Independent Commission for Aid Impact (ICAI) provides robust, independent scrutiny of the UK’s official development assistance (ODA), to assist the government in improving the effectiveness and impact of its interventions and to assure taxpayers of the value for money of UK aid spending. Our main vehicle for this scrutiny is the publication of reviews on a broad range of topics of strategic importance in the UK’s aid programme. A vital part of these reviews is our annual follow-up process, where we return to the recommendations from the previous year’s reviews to see how well they have been addressed.

This report provides a record for the public and for Parliament’s International Development Committee (IDC) of how well the UK government has responded to ICAI recommendations. The follow-up process is also an opportunity for additional interaction between ICAI and responsible staff in aid-spending departments, offering feedback and learning opportunities for both parties. The follow-up process is central to our work to support learning and improvements in UK aid delivery and to ensure maximum impact from reviews.

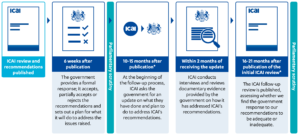

Figure 1: Timeline of ICAI’s annual follow-up process

*We conduct our follow-up assessment on an annual basis. After receiving an update on progress from government, evidence gathering starts in January, with publication in the summer.

The follow-up process is structured around the recommendations provided in each ICAI review (see Figure 1 above for an illustration of the process). Soon after the original ICAI review is published, the government provides a formal response (within six weeks). The response sets out whether the government accepts, partially accepts or rejects ICAI’s recommendations and provides a plan for addressing the issues raised. This is typically followed by a hearing, either in the ICAI sub-committee of the IDC or as part of the work of the main committee. The formal follow-up process starts around a year after the publication of the original review and results in the publication of the follow-up review. The exact time gap between review and follow-up depends on how early in ICAI’s annual review cycle the relevant report was published.

To start the follow-up exercise, ICAI asks aid-spending departments and bodies for an update on what they have done and plan to do. This is followed by an evidence gathering stage, where we investigate the extent to which the government has done what it promised and – considering any additional relevant actions – determine if this is an adequate response. The findings are reported and scored in the followup review. After publication, there is parliamentary scrutiny of the review’s findings.

Scoring the follow-up exercises

Each review we follow up for the first time is scored using a tick or a cross, depending on whether we find the overall progress adequate or inadequate. The score takes into consideration the wider context, including external constraints, in which government actions have taken place. It also considers the time the relevant government department or organisation has had to plan and implement changes.

An inadequate score results from one or more of the following three factors:

- Too little has been done to address ICAI’s recommendations in core areas of concern (the response is inadequate in scope).

- Actions have been taken, but they do not cover the main concerns we had when we made the recommendations (the response is insufficiently relevant).

- Actions may be relevant, but implementation has been too slow and we are not able to judge their effectiveness (the response is insufficiently implemented).

The third factor – the adequacy of implementation – is not a simple question of checking if plans have been put into practice yet. We take into consideration how ambitious and complicated the plans are, and how realistic their implementation timelines are. Some changes are ‘low-hanging fruit’ and can be achieved quickly, while others demand long-term dedicated attention and considerable resources. An inadequate score due to slow implementation will only be awarded if ICAI finds the reasons provided for lack of implementation insufficient.

This year’s follow-up review covers three ICAI reviews with a total of 14 recommendations. After briefly setting out our methodology, we discuss the contextual challenges of last year, and how these have affected how ICAI’s recommendations have been taken up. We look at the central role of transparency for learning and achieving improvements in aid delivery and provide case studies of learning journeys seen through the lens of the ICAI review and follow-up cycle. This is followed by an account of progress on the three reviews and four outstanding issues covered by this year’s follow-up review. We sum up with a brief conclusion and a list of the reviews and recommendations we plan to return to again next year.

Methodology

When we follow up on the findings and recommendations of our past reviews, we focus on four aspects of the government response:

- Whether the actions proposed in the government response are likely to address the recommendations

- Progress on implementing the actions set out in the government response, as well as other actions relevant to the recommendations

- The quality of the work undertaken and how likely it is to be effective in addressing the concerns raised in the review

- The reasons why any recommendations were only partially accepted (none of the recommendations were rejected).

We begin by asking the relevant government department or organisation to prepare a brief note, accompanied by documentary evidence, summarising the actions taken in response to our recommendations. We then check that account through interviews with responsible staff, both centrally and in country offices, and by examining relevant documentation, such as new strategic plans, annual reviews, etc. Where necessary or useful, we interview external stakeholders, including other UK government departments, multilateral partners and implementers. To ensure we maintain sight of broader developments, we also assess whether ICAI’s findings and analysis have been influential beyond the specific issues raised in the recommendations, as well as whether changes in the environment have affected the relevance and/or urgency of particular recommendations.

We conducted a more detailed follow-up review than usual of CDC’s investments in low-income and fragile countries. In consultation with CDC, we selected a sample of ten specific investments, combined with detailed interviews with a broad range of CDC staff. This allowed for both depth and breadth of analysis on how development impact is addressed throughout all the stages of CDC’s investment process.

The follow-up process for each review concludes with a formal meeting between a commissioner and the senior civil service counterpart in the responsible department. At the end of the follow-up process, we identify issues that warrant a further follow-up the following year. The decision takes into account the continuing strategic importance of the issue, the action taken to address it, and whether or not there will be other opportunities for ICAI to pursue the issue through its future review programme. 2.5 We also use the follow-up process to inform internal learning for ICAI about the impact of our reviews on UK aid and how we communicate our findings and recommendations to achieve maximum traction with the government.

Box 1: Limitations to our methodology

The follow-up review addresses the adequacy of the government response to ICAI’s recommendations. Its findings are based on checking and examining the government’s formal response, and its subsequent actions in relation to the recommendations from the review. The time and resources available for this evidence gathering exercise are limited, and not comparable to a full ICAI review.

Aid transparency in a time of crisis and transition

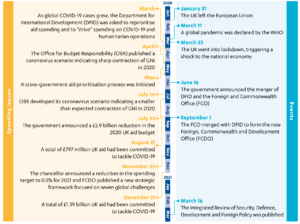

Figure 2: Timeline of a year of pandemic and disruption for UK aid

A difficult follow-up process in a difficult context

This follow-up review – the evidence gathering for which took place between January and April 2021 – mainly covers actions taken by the UK government to address ICAI recommendations during the calendar year 2020. This has been a period of enormous change in the UK aid landscape. The COVID-19 pandemic triggered a global humanitarian crisis. In response, the UK government recommitted a total of £1.39 billion in UK aid for the COVID-19 response. At the same time, lockdown measures and restrictions on travel around the world severely affected the delivery of aid programmes, as did an unprecedented in-year cut of £712 million in planned expenditure after a sharp drop in UK gross national income. The merger of the Department for International Development (DFID) and the Foreign and Commonwealth Office (FCO) to form the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO) in September 2020, the spending review, the Integrated Review of Security, Defence, Development and Foreign Policy (published on 16 March 2021) and the November 2020 decision to reduce UK ODA spending to 0.5% of GNI in 2021 have all contributed to deep uncertainty about longer-term aid-spending priorities.

It is in this setting of continued disruption and ongoing uncertainty that the follow-up of the government’s commitments to address ICAI’s recommendations has taken place. The practical implications of ongoing cuts in ODA spending were still being worked through when the evidence gathering for the follow-up review came to an end in April 2021, with many organisational and budget allocation decisions still to be made.

In this period of flux, interaction with the relevant government departments and teams has at times been challenging, and ICAI has found it more difficult to get access to relevant documentation and arrange interviews with the right people for the follow-up. ICAI is aware that spending cuts and reprioritisations, as well as the reorganisation of teams, redeployment of staff and uncertainty about ways of working caused by the formation of FCDO, have been factors in the problems experienced. Responses to ICAI requests were sometimes slow and information needed in order to assess progress on our recommendations was often not forthcoming. Of particular significance, draft strategies and working-level documents (in other words, those not published or signed off at ministerial level), which could have provided a sense of the direction of travel in areas affecting ICAI’s recommendations, were generally not shared. This contrasts with the more open response to the follow-up in previous years. Overall, there has been a reduction in transparency on the part of FCDO in this year’s engagement with the ICAI follow-up.

A lack of information was a core finding of ICAI’s December 2020 information note on procurement during the COVID-19 response, which concluded that “[a]id-spending government departments worked flexibly with suppliers to minimise the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on their work, but lack of transparency about the government’s new aid priorities hampered delivery”.10 Concern about reduced transparency in UK aid also came up in several of this year’s follow-up exercises:

- How UK aid learns: The follow-up of this review makes clear that transparency continues to be a concern, and potentially a growing one. Some technical improvements took place over the past year, notably the adoption across government of the Microsoft Teams platform. But a range of incompatible and inflexible legacy systems remain. Due to COVID-19 constraints, the cross-government working group on transparency in aid management was paused and it is not clear when it will be reconvened. We were told, however, that a Department of Health and Social Care (DHSC) ODA transparency working group meets every two months and is attended by colleagues from FCDO and the Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy (BEIS) to share best practice. It is uncertain whether FCDO will use the relaunched Aid Management Platform to keep the same standards of transparency, or potentially improve on them, extending them to all departments.

- Ghana country portfolio and PSVI reviews: Very little documentary evidence was provided when requested by ICAI, making it difficult to verify findings.

- Maternal health: Long-awaited key strategic documents that would have provided clarity on UK aid’s objectives and plans for improving maternal health remain in draft form and unpublished after long delays. A redacted delivery framework for the draft Ending Preventable Deaths Action Plan was shared with ICAI, but this is still awaiting ministerial approval.

- Newton Fund: While BEIS was very open in supporting the ICAI follow-up, during the course of the follow-up exercise we heard that the deliberations and decisions on ODA funding cuts – which mainly took place within FCDO, rather than BEIS – were made without consultation with stakeholders in the research community, and with little openness on how decisions were reached, leaving Newton Fund and other ODA research funding grantees in a prolonged situation of uncertainty about the future of their projects.

This was not a uniform picture. Both BEIS and CDC worked closely with ICAI to support a thorough follow-up and provided ample documentary evidence as well as access to interviews, to back up and triangulate findings. In the case of CDC, the ICAI review team was able to review a very wide range of documents provided by CDC and to interview over 30 CDC staff members, who made themselves available in a timely way. For the How UK aid learns follow-up, there was a wide range of responses from government departments to ICAI’s requests, from a lack of engagement to an enthusiasm for sharing improvements, challenges and learning.

Learning journeys

This year’s follow-up review provides us with an opportunity to present stories of notable changes in the effectiveness, efficiency and learning of UK aid programmes emerging from fruitful engagement between ICAI and the relevant departments. These stories are shared in order to illustrate examples of the longer-term impacts of ICAI’s work, and to identify some of the common factors, including transparency and openness, which have allowed these impacts to emerge.

The story of the CDC learning journey

The original review of CDC’s investments in low-income and fragile states was published in March 2019, and the government responded to its recommendations in May 2019. ICAI then undertook its first follow-up of progress around a year after the review was published, and this second follow-up is taking place just over two years later.

The original ICAI review was given an amber-red score primarily based on the conclusion that CDC had not done enough to maximise the development impact of its UK aid investments. Through the initial review, CDC and ICAI engaged in extensive dialogue about how development impact was being addressed in the organisation, and how improvements in this area and on a range of related issues could be made. The recommendations that emerged out of this review reflected a recognition that CDC was on a journey towards maximising its development impact, and ICAI aimed to support CDC in making progress towards this destination.

ICAI’s first follow-up of its review on CDC concluded that although CDC had made valuable progress in a number of areas – including setting clearer development impact goals, better monitoring of their delivery and improved learning – the pace and depth of change was not yet sufficient, and therefore ICAI would return to assess its progress through a further follow-up review. This was a difficult judgment for CDC to receive, but the organisation remained focused on taking its ongoing policy and practice reforms further.

CDC also responded positively and rapidly to ICAI’s second follow-up, which meant that there was an opportunity to design a thorough and extended process. This included reviewing and analysing a sample of ten investments and interviewing a broad range of CDC staff. As a result, this second followup allowed ICAI to test CDC’s efforts to embed a focus on development impact across its investment processes and to illustrate its progress as well as some ongoing challenges.

After three years of close engagement between ICAI and CDC, this year’s follow-up review has been able to conclude that CDC’s investment decisions now address development impact throughout the investment cycle and consideration of impact is driving active management of investments to a much greater extent than before the ICAI review.

The story of the Global Challenges Research Fund and Newton Fund learning journey

As part of the trend of the delivery of UK aid expanding to departments other than DFID, BEIS went from spending £270 million in ODA funds in 2014 to £851 million in 2018 and just over £1 billion in 2020. A significant part of this spending was through two large development research funds, the Global Challenges Research Fund (GCRF) and the Newton Fund. ICAI reviewed the GCRF in September 2017 and the Newton Fund in June 2019. In both cases, ICAI found that many key aid management practices, including those relating to oversight, transparency and value for money, were lacking and that the funds did not have suitable strategies and mechanisms in place to ensure that their spending was a good use of UK aid.

The original government response from BEIS to both reviews’ recommendations that the department should strengthen aid management in order to maximise the potential development impact of the funds was to query ICAI’s understanding of the nature of research as much as the department’s own understanding of ODA management. However, this initial reaction gave way to what became an impressive set of changes over the next few years. BEIS created a robust joint governance structure for the two funds, introduced safeguards at both project and portfolio level to ensure ODA eligibility and attention to development impact, instituted a strong monitoring, evaluation and learning (MEL) framework, and improved data collection and transparency on the delivery and results of the funds’ activities.

ICAI followed up both the GCRF and the Newton Fund two years in a row, having noted improvements in many aspects of its recommendations the first time, but opting to return to the recommendations in order to check on the momentum and sustainability of changes as well as highlighting outstanding areas where progress was not yet as visible. In its update on progress to ICAI in December 2020, BEIS wrote:

In past reviews of the Newton Fund, ICAI has rightly highlighted the need to better demonstrate the development impact delivered by the Fund. Specifically, ICAI has highlighted the need for BEIS to develop stronger value for money assessments, improve how impact is measured against key metrics, and build on MEL capacity to ensure these are robustly measured. As highlighted by the Foreign and Development Secretary as part of this year’s Spending Review, HM Government needs to take a more focused approach to development impact, and BEIS is confident it has addressed this.

ICAI may have helped spur the significant reforms to ODA management in BEIS through its Newton Fund and GCRF reviews, but a cultural shift in the department has ensured that the momentum for this work now comes from the inside. In the current funding environment, the future of both funds is in the balance. The speed of the cuts to the GCRF, including the closing down of ongoing research projects, carries value for money risks, even more so considering the investments at the fund level to ensure better value for money and greater focus on development impact as well as excellent research. But BEIS’s efforts to improve its ODA practices should have been worthwhile regardless of whether these particular funds are renewed. As BEIS noted in an interview for this follow-up review: the work to implement new policies and processes “doesn’t stop even if this is delivered somewhere else” – the learning should have been captured for similar funds in future.

Conclusion on transparency and learning

FCDO published a review of ICAI in December 2020. Many of the recommendations centred on strengthening ICAI’s role in fostering transparency and learning in order to achieve the shared objective of improving the delivery of UK aid. The review noted that ICAI’s “scrutiny process relies on the positive engagement of the department or body under review and a commitment to transparency and data sharing. The FCDO, and all other ODA-spending departments, needs to be a field-leader on aid transparency.”

The year 2020 was an extraordinary time in UK aid. As the structures of the new FCDO and changes to the scaled-back UK aid programme take shape in 2021, this should be accompanied by a renewed focus on transparency and accountability in UK aid. An open and constructive relationship with FCDO and other aid-spending departments needs to be the foundation of ICAI’s oversight role and its ability to work with government to foster learning and improve the delivery of UK aid. The two learning journeys described above, taken from two of the reviews followed up by ICAI this year, show the strong results that accrued when CDC and BEIS worked through the challenges identified in ICAI’s reviews, with ICAI as a critical friend along the way.

Findings from individual follow-ups

This section presents the results of our follow-up assessments of the government’s responses to ICAI’s recommendations. Each review we have followed up on is presented individually, with a focus on the most significant results and gaps in the government response.

We begin with the follow-up of our reviews on How UK aid learns, The changing nature of UK aid in Ghana, and The UK’s Preventing Sexual Violence in Conflict Initiative. These three are followed up for the first time since their publication and the result of the assessment is scored.

We then present an extended review of one of the outstanding issues from last year’s follow-up exercise: the March 2019 review of CDC. In consultation with CDC, ICAI decided to conduct a more in-depth review during this second follow-up. Finally, we turn to the remaining three outstanding issues, on maternal health, DFID/FCDO procurement, and the Newton Fund. None of the outstanding issues are scored, but a decision is made on whether or not to return to the review again next year.

How UK aid learns

A reasonably good response to ICAI’s recommendations and underlying concerns, particularly in the early stages after publication. However, contextual challenges and the FCDO merger have led to progress stalling, particularly on strengthening transparency. There is potential for FCDO to take on a positive coordination and standard-setting role across government, and for transparency to be increased, but until the future of the Aid Management Platform is clear, and FCDO evaluation plans and the new UK aid strategy are in place, we will not know if this potential will be realised. We therefore score the response as inadequate and will return to this review next year.

The How UK aid learns rapid review was published in April 2019, covering all UK aid-spending departments. As an increasing amount of the UK aid budget (around a quarter of all ODA in 2019) was spent by departments other than DFID, the review focused on how these had developed their capabilities to manage and use ODA effectively and transparently. The rapid review was unscored, but noted that although departments with new aid budgets had increased their understanding of how to use aid effectively, more needed to be done to integrate learning into international development spending across government to ensure value for money. ICAI made four recommendations.

Both the initial review and the subsequent follow-up have been complicated exercises, involving assessing the performance of numerous individual departments, the role played by DFID (in the original review) and FCDO (by the time the follow-up took place) in supporting those departments, and cross-government learning efforts to ensure collaboration and coherence. Due to ICAI having limited resources available for the follow-up exercise, we sampled a selection of departments and units, covering a selection of high-level, mid-level and low-level ODA spenders, and a mix of departments with larger ODA portfolios and those with the ambition of scaling up their capacity for ODA spending. We did not follow up on departments with small, transactional ODA spend. The selected departments included – in addition to FCDO – BEIS, the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (Defra), DHSC, HM Treasury, the Joint Funds Unit (JFU) and the Conflict, Stability and Security Fund (CSSF), and the Office for National Statistics. ICAI also requested interviews and documentation from the Home Office but did not receive a response.

| Subject of recommendation | Government response |

|---|---|

| DFID should be properly mandated and resourced to support learning on good development practice across aid-spending departments. | Partially accepted |

| As part of any spending review process, HM Treasury should require departments bidding for aid resources to provide evidence of their investment in learning systems and processes. Accepted | Accepted |

| The Senior Officials Group should mandate a review and, if necessary, a rationalisation of major MEL contracts, and ensure that they are resourced at an appropriate level. | Partially accepted |

| Where aid-spending departments develop knowledge management platforms and information systems to support learning on development aid, they should ensure that these systems are accessible to other departments and, where possible, to the public, to support transparency and sharing of learning. | Partially accepted |

Recommendation 1

The original review noted that DFID had a crucial role to play in ODA learning as a repository of expertise on aid management and that the support it provided to other departments was useful and appreciated. ICAI recommended that DFID should be properly mandated and resourced to support learning on good development practice across all aid-spending departments. As a result of ICAI’s review, DFID was allocated funds by HM Treasury in 2020-21 for this purpose.13 There was no specific commission provided to DFID at the time the funds were given that set out its role in relation to other departments.

Since the original review, the context for this recommendation has changed dramatically. With the merger of DFID and the FCO in September 2020, and the contraction of UK aid spending, a higher proportion of the spending of UK ODA is under the authority of FCDO, with reduced allocations to other government departments. This makes some of the risks highlighted in the ICAI review less salient, but significant ODA spending will continue to take place outside the new FCDO. The merger also places FCDO in a strong position to become the unifying point of a one-government approach to aid delivery, at both central and in-country level. As such, the need for FCDO to be commissioned and resourced to oversee and support MEL across government ODA-funded programmes is as important as ever.

After a disrupted year, progress on this recommendation has been limited. While FCDO has continued to take a hands-on approach, and we saw some positive changes to FCDO’s support for learning and capacity building, the department’s role in respect of the other departments has not yet been clearly set out (and this year, no funds were allocated for this task). Last year’s spending review was a one-year review only, although we were told that this will form the basis for longer-term strategic planning in subsequent years. There are plans for a new UK aid strategy, as well as a new FCDO evaluation strategy. ICAI was told there is an expectation that more FCDO oversight and a stronger one-government approach will feature in the new aid delivery structures. We would like to return to this recommendation once this new structure is in place.

Recommendation 2

ICAI recommended that as part of any spending review process, HM Treasury should require departments bidding for aid resources to provide evidence of their investment in learning systems and processes. This was the only recommendation that was accepted in full by the government, and efforts to address it began before the ICAI review was published. While the 2020 spending review ended up only being a one-year review, there was nevertheless a range of efforts to improve MEL arrangements, driven in particular by new, stricter requirements by HM Treasury. Specific questions were included in all ODA bids to HM Treasury, asking departments to provide evidence of their investment in learning systems and MEL capabilities. HM Treasury also provided specific guidance on how to complete this section of the bid document.

Improvements, from our sample, to meet HM Treasury’s requirements, included:

- JFU and CSSF: The JFU facilitated a peer exchange of monitoring and evaluation (M&E) advisers and MEL champions, bringing staff across the CSSF network together to share ideas, good practice and learning on key thematic policy areas. CSSF also has a new blended learning course focused on developing skills in tools and practices that programme managers need to use MEL and programme management to foster best practice in aid delivery.

- Defra expanded its ODA MEL capacity as part of its climate finance portfolio and is working with FCDO and BEIS on cross-government MEL.

- DHSC is aligning its annual reviews with FCDO practice and hired a new full-time MEL adviser for its global health security work. It plans to publish annual reviews on DevTracker and through platforms presenting data according to International Aid Transparency Initiative standards.

In all, the actions to address the concerns underlying this recommendation have been relevant, effective and have shown clear progress.

Recommendation 3

The original ICAI review found that reliance on outsourced MEL services could be a part of the solution for departments to overcome their capacity constraints on aid management, but that a proliferation of outsourced MEL contracts created risks of overlap and duplication. Finding a lack of a clear rationale for the shape or size of MEL contracts, ICAI recommended that the Senior Officials Group should mandate a review and, if necessary, a rationalisation of major MEL contracts, and ensure that they were resourced at an appropriate level.

In response to this recommendation, a cross-government working group was established, with a draft discussion paper developed by DFID. A few working group discussions were held, including one after the announcement of the FCDO merger to discuss a cross-government MEL approach to ODA. However, with the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic, followed by the merger, the spending review and the ODA reductions, the process stalled.

A changing context means that it would no longer be good value for money to review existing ODA MEL contracts, since more than 80% of the contracts identified in ICAI’s original review have already ended or are due to end in 2021. The priority is therefore to develop a common approach to MEL contracting for FCDO. ICAI was informed that FCDO is currently adapting DFID’s centralised evaluation system and creating a mixed system of centralised and decentralised elements, and a new strategy is awaited. It is important that the early work and progress in response to ICAI’s recommendation is not abandoned, but that the thread is picked up again as FCDO emerges from this lengthy period of uncertainty and flux. The merger of DFID and the FCO poses an opportunity to establish common standards for ODA MEL across government, under the guidance of FCDO.

Recommendation 4

ICAI recommended that when departments develop technical knowledge management platforms and information systems to support learning on development aid, they should ensure that these systems are accessible to other departments and, where possible, to the public, in order to support transparency and sharing of learning. The original report found that many departments were a long way from meeting UK government commitments to transparency of UK aid and incompatible systems between departments were obstacles to learning and collaboration, at both central and in-country level. The progress update provided to ICAI in January 2021 confirmed that the Aid Learning Platform14 (former DFID capability offer) would migrate to the Global Learning Platform from 1 April 2021, although this is not yet operational with the same functionality across all ODA spending departments.

Transparency continues to be a concern, and our follow-up exercise has noted a slowing down of the implementation of transparency improvements. Technically, some improvements have taken place, notably the adoption across government of the Microsoft Teams platform. This has helped improve communication and information sharing within and between departments, which in turn supports cross-government learning. But there remains a range of incompatible and inflexible legacy systems, and the cross-government working group on transparency has been paused. We were told that a DHSC ODA transparency working group meets every two months and is joined by colleagues from FCDO and BEIS to share best practice, particularly in the context of the COVID-19 response. ICAI will therefore return to this topic in next year’s follow-up review, in order to assess whether systems are put in place with FCDO at their centre to ensure that information on aid management and learning flows between departments. In addition to assessing progress on FCDO’s Aid Management Platform,15 and the extent to which this platform can be used or linked into by other aid-spending departments, it will also be important to see how well transparency objectives are reflected in the new UK aid strategy.

Conclusion

Only one of the four ICAI recommendations was fully accepted by the government (Recommendation 2). In the follow-up, it has become clear that the actual responses to the recommendations that were only partially accepted do not reflect this nominal partial rejection. Aid-spending departments, HM Treasury and FCDO have taken the recommendations seriously, and progress has been made across all of them. However, progress stalled across all recommendations in the challenging context of the pandemic, contraction of the aid budget and the FCDO merger. In the case of commitments to aid transparency, we have seen signs of a deterioration during the merger process. ICAI has therefore scored the response to its recommendations as inadequate and will come back to this review as an outstanding issue next year.

The changing nature of UK aid in Ghana

There has been reasonable progress on some of the issues raised by ICAI’s review. But overall, a combination of an initially vague response to some of ICAI’s recommendations, delays due to contextual challenges, and a reluctance to share documentation or briefings on ongoing strategic work by FCDO such as the Africa strategy and the delivery framework, means that it has not been possible to verify reported improvements. We have therefore scored the response to ICAI’s recommendations as inadequate and will return to this review next year.

The changing nature of UK aid in Ghana, published in February 2020, was ICAI’s first country portfolio review, focused on the transitioning of the UK’s development partnerships with Ghana as the latter aimed to move ‘beyond aid’ after achieving the status of lower-middle-income country in 2011. The review was scored green-amber. It concluded that UK aid had been mostly effective at helping some of the poorest and most vulnerable in Ghana but was risking the sustainability of its results if it scaled back its social sector programming too quickly. ICAI made six recommendations, several of which were focused on the UK’s approach to transitioning development partnerships in general, building on the Ghana experience.

| Subject of recommendation | Government response |

|---|---|

| In transition contexts, DFID should ensure that the pace of ending the bilateral financing of service delivery in areas of continuing social need must be grounded in a realistic assessment of whether the gap left will be filled. | Partially accepted |

| DFID should require portfolio-level development outcome objectives and results frameworks for its country programmes. | Accepted |

| DFID Ghana should learn from its own successes and failures when designing and delivering its systems strengthening support and technical assistance. | Accepted |

| In transition contexts, DFID country offices, in coordination with the multilateral policy leads, should increasingly work to influence the department’s country multilateral partners on issues of strategic importance. | Accepted |

| In order to strengthen the relevance of its aid programming and accountability to the people expected to benefit, DFID should include information on citizen needs and preferences, especially for the most vulnerable, as a systematic requirement for portfolio nd programme design and management. | Partially accepted |

| The government should provide clear guidance on how UK aid resources should be used in implementing mutual prosperity to minimise risks and maximise opportunities for development. | Partially accepted |

Recommendation 1

The original review found that, as the UK transitioned away from bilateral aid in Ghana, decisions on where to reduce funding were not underpinned by robust analysis of the implications of the cuts for financing, service delivery and development results. Programming in the social services sector absorbed 84% of DFID Ghana’s reduction in bilateral spending during the review period, at a time when poverty was increasing and regional inequality worsening. As a result, development gains achieved through these programmes were at risk of being reversed. ICAI therefore recommended that, in transition contexts, DFID should ensure that the pace of ending the bilateral financing of service delivery in areas of continuing social need must be grounded in a realistic assessment of whether the gap left will be filled.

The government partially accepted this recommendation, pointing to the UK policy of not financing service delivery in transition contexts where governments can self-finance, and to the government of Ghana’s aspiration to move beyond aid. While agreeing with ICAI that cuts should be made thoughtfully, the government made no commitment on what such a thoughtful approach would entail. It did not engage with ICAI’s finding that Ghana’s tax collection capacity and its fiscal pressures were such that the government of Ghana was not yet in a position to take over the full funding of basic social services delivery for the poorest and most vulnerable. We were told that the new Africa strategy, which is under development, would deal with this issue as part of the funding prioritisation that will have to be made in a ‘0.5% world’ of reduced overall aid spending, but we have not seen a draft of this strategy, nor the country plan for Ghana.

In practice, due to the economic crisis caused by the COVID-19 pandemic in Ghana, the UK returned to direct bilateral financing of service delivery in 2020. This shift was appropriate, to protect gains in the health and education sectors. However, the underlying concerns that led to ICAI’s recommendation remain to be considered in transition contexts and will doubtless arise as the UK implements spending reductions. FCDO bilateral aid to African countries is expected to be £891 million in 2021.16 This is down from £2.2 billion in 2020.

Recommendation 2

ICAI recommended that DFID should require portfolio-level development outcome objectives and results frameworks for its country programmes, since longer-term development outcome objectives were often lacking, and DFID was instead relying on the narrower metric of quantifiable outputs that could be directly attributable to DFID programming. The review found that, in the absence of medium-to-long-term outcome objectives, programming was encouraged to deliver short-term results without enough attention to how programmes would contribute to sustainable, scaled-up impact in Ghana.

The government accepted the recommendation and DFID was already progressing well on developing a portfolio results framework for the Ghana office at the time of publication of the original ICAI review. However, it is not clear that progress has continued under FCDO. The new FCDO director general for delivery has been tasked with developing new delivery frameworks, to be rolled out during 2021. ICAI has not had sight of the draft delivery framework or the draft Ghana country plan, so while it seems that the plans were previously on the right trajectory, in the current scenario of drastic cuts and uncertainty we are not able to confirm that this recommendation has received an adequate response.

Recommendation 3

ICAI’s original review found that DFID had not consistently applied the lessons from successful technical assistance programmes. With bilateral aid scaled down and the number of in-country staff reduced, the quality of technical assistance programming will become increasingly important. ICAI therefore recommended that DFID Ghana should learn from its own successes and failures when designing and delivering its systems strengthening support and technical assistance.

The response to this recommendation seems to have been good, based on the written update from FCDO and information from interviews, although this was not accompanied by documentary evidence. The British High Commission in Accra has assessed the lessons learnt from its technical assistance programmes and is applying the lessons to new programming through more deliberate strategic work. This involves working more politically – ensuring that systems strengthening programmes are backed by political and diplomatic engagement, a task that has become easier with the merger of DFID and the FCO. A consistent and coherent effort has been made to ensure that technical assistance for institutional strengthening across sectors is catalytic, using diplomacy together with bilateral development funding, working through centrally managed programmes, involving the rest of the UK government and working with other development partners, including multilaterals.

Recommendation 4

Recommendation 4 went beyond the case of Ghana to request that, in transition contexts, DFID country offices, in coordination with the multilateral policy leads, should increasingly work to influence the department’s country multilateral partners on issues of strategic importance. This was so that the UK government could promote its objectives, and the sustainability of past development gains, through closer engagement with the multilaterals it funds, especially as its own bilateral aid programming reduced.

DFID accepted the recommendation, and its actions to address it through a ‘whole of ODA’ approach have been taken further by the merged FCDO. The multilateral team has provided ‘country scripts’ with guidance notes and support for the whole FCDO network (not just the previous 38 DFID country offices), and scripts have been piloted for Ghana, Mali, Nigeria, Southern Africa, Morocco, Vietnam, Latin America and the Caribbean, and the Pacific. The British High Commission in Accra was the first post to pilot this effort and country scripts are currently being revised as part of the new delivery framework. The High Commission is now engaging in a much more deliberate and active manner with multilaterals, including on the response to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Recommendation 5

The original ICAI review found that there were no DFID requirements to solicit citizens’ perspectives on health, education and livelihoods as part of its country diagnostics or in the decision making on how fast and where to cut bilateral aid spending in Ghana. It recommended that, in order to strengthen the relevance of its aid programming and accountability to the people expected to benefit, DFID should include information on citizen needs and preferences, especially for the most vulnerable, as a systematic requirement for portfolio and programme design and management.

The government partially accepted this recommendation. In its response to the review, DFID noted that it puts people at the centre of its work “at the programme level, where it is sensible and feasible to do so, rather than the portfolio level”, although did not explain why the latter would not be feasible.

The actions taken by DFID included strengthening its SMART rules guidance to set out the expectations that “beneficiary engagement” should take place throughout a programme’s life cycle. The latest update provided to ICAI indicated that the work is continuing after the merger, and that “beneficiary engagement” will be part of the new FCDO delivery frameworks. However, we are not able to verify this yet. The FCDO team in Ghana noted that it had carried out fewer citizen engagement activities due to COVID-19.

Recommendation 6

At the time of the Ghana review, the shift towards mutual prosperity objectives in UK aid required a careful effort on the part of DFID country teams engaged with diplomatic and trade counterparts to ensure that the increased focus on secondary benefits to the UK from aid and development programmes did not override development benefits for the partner country. The review found that the ability of country offices to manage this risk was too reliant on leadership continuing to give priority to development objectives, and the capacity of DFID country teams to engage with their UK government counterparts on risks. ICAI therefore recommended that the UK government should provide clear guidance on how UK aid resources should be used in implementing mutual prosperity objectives to minimise risks and maximise opportunities for development.

The government only partially accepted this recommendation, and its formal response (both after the original review and in its update for the follow-up exercise) has been vague. The follow-up written response noted the ‘double lock’ for the foreign secretary and chief secretary on discretionary ODA allocations to other government departments and the integration of the Prosperity Fund in FCDO’s baseline engagement. It also noted that the merger would help with greater coherence, including for mutual prosperity, but did not say exactly how risks to development funds will be managed. ICAI was informed that the new Africa strategy, which is under development, would address the concerns underlying this recommendation. Without seeing the Africa strategy, ICAI is not yet able to confirm this.

Conclusion

A lack of documentary evidence has made it difficult to assess progress on ICAI’s recommendations. This is partly due to the disruption over the period since ICAI’s initial review was published, which has led to delays as new organisational structures have been created and new strategic paths are being laid down for the new FCDO. But there has also been a reluctance to share drafts and provide briefings on work in progress. Apart from Recommendation 4, where we have seen a clear shift towards a stronger focus on influencing UK aid’s multilateral partners at country level on issues of strategic importance, we have not seen sufficient evidence to conclude that the response to ICAI’s recommendations has been adequate. Having not seen the new Africa strategy or the Ghana country plan, with its planned key performance indicators, and without knowing the extent to the cuts in UK aid to Ghana, ICAI will return to this review next year as an outstanding issue.

The UK’s Preventing Sexual Violence in Conflict Initiative

Important strategic work is under way which could amount to a strong response to ICAI’s recommendations and underlying concerns. However, since ICAI has not seen the planned PSVI strategy, key performance indicators or MEL framework, or received information on the budget for PSVI-related activities, we are not yet able to conclude that the government response has been adequate. We will therefore return to this review as an outstanding issue next year.

The ICAI review of the Preventing Sexual Violence in Conflict Initiative (PSVI) was published in January 2020. It concluded that the initiative was an important body of work on a neglected topic, but that it fell short of the government’s stated ambitions. Lacking an overall strategy, as well as a robust MEL approach and adequate mechanisms for meaningful survivor inclusion, the PSVI was given an amber-red score.

| Subject of recommendation | Government response |

|---|---|

| The UK government should ensure that the important issue of preventing sexual violence in conflict is given an institutional home which enables both full oversight and direction, while also maximising the particular strengths and contributions of each participating department. | Partially accepted |

| The UK government should ensure that its programming activities on preventing sexual violence in conflict are embedded within a structure which supports effective design, monitoring and evaluation, and enables long-term impact. | Accepted |

| The UK government should ensure that its work on preventing conflict-related sexual violence is founded on survivor-led design, which has clear protocols in place founded in ‘do no harm’ principles. | Accepted |

| The UK government should build a systematic learning process into its programming to support the generation of evidence of 'what works' in addressing conflict-related sexual violence and ensure effective dissemination and uptake across its portfolio of activities. | Accepted |

Recommendation 1

The original review found that there was no strategic vision, specific objectives, or theory of change driving the PSVI. The initiative was set up as an FCO-led cross-departmental effort, with the FCO, DFID and the Ministry of Defence (MOD) as the main contributing departments. However, while there was a small PSVI team in the FCO, this team did not have sufficient oversight – or even knowledge – of relevant government activities and programmes. The review found that even compiling a list of programmes and budgets falling under the category of conflict-related sexual violence (CRSV) was difficult, and only estimates could be made. Each department and in-country team was left to interpret the Initiative in line with their own strategic priorities rather than through a unified cross-departmental strategy and concrete objectives. ICAI therefore recommended that the UK government should ensure that the important issue of preventing sexual violence in conflict is given an institutional home which enables both full oversight and direction, while also maximising the particular strengths and contributions of each participating department.

The government only partially accepted this recommendation, as a result, it seems, of focusing on only one part of it (arguing that there was indeed a dedicated PSVI team in the FCO) rather than on the recommendation in full (that this team did not have the human and financial resources, processes and authority to provide direction and oversight to the cross-government work on CRSV). The government did, however, agree with the need for improved oversight and strategic direction.

After the publication of the ICAI review, the PSVI team’s time has mainly been spent on, first, the COVID-19 response, with the whole team redirected to support this, and then the preparation and execution of the merger. The new FCDO has reorganised the different gender teams and programmes from DFID and the FCO. PSVI will fall under the Office of Conflict, Stabilisation and Mediation, within a broader Gender and Conflict team. Meanwhile the Violence Against Women and Girls (VAWG) team will fall under a separate Directorate of Education, Gender and Equality. In order to strengthen ties between work on VAWG and Gender and Conflict (as well as other gender teams), we were told that there will be a Gender Equality Hub covering all FCDO gender policy teams (including PSVI), which will be hosted in the Education, Gender and Equality directorate.

A three-year strategy specifically for PSVI is under development. This will have a Theory of Change (ToC), key performance indicators and MEL arrangements. 4.38 The dust has not yet settled on this new organisation of FCDO’s gender work. How activities relevant to CRSV will in practice fit within this broader organisational structure on gender is not yet clear, including the extent to which FCDO’s VAWG programming and PSVI will be drawn into the same network and structure. Without seeing a draft of the new PSVI strategy, ICAI is not yet able to conclude whether the changes will lead to improved oversight and coordination of programming. Finally, how the MOD’s PSVI relevant efforts will link into this FCDO structure is not clear.

Recommendation 2

The ICAI review found that the PSVI did not have sufficiently robust and appropriate systems for design, monitoring and evaluation. There were no ToCs – either for PSVI as a whole or for individual projects. PSVI projects were mainly monitored at output level, making effectiveness of programming difficult to assess. The one-year FCO funding cycle was ill-suited to interventions to address CRSV. Furthermore, frequent delays in the disbursement of funds, combined with the 80% rule, often reduced 12-month programmes to nine months or less. As a result of these findings, ICAI recommended that the UK government should ensure that its programming activities on preventing sexual violence in conflict are embedded within a structure that supports effective design, monitoring and evaluation, and enables long-term impact.

As of 1 April 2021, a new Programme Operating Framework (PrOF), with MEL provisions throughout the programme delivery cycle, will guide programming across the entire FCDO portfolio, including PSVI. However, the PSVI team told us that one-year funding cycles will continue to be the norm for the PSVI portfolio, which is problematic for CRSV programming. The new PrOF, together with the development of a three-year PSVI strategy with key performance indicators (KPIs) and MEL arrangements, promises to be a strong response to ICAI’s concerns, although without sight of the draft PSVI strategy it is too early to draw conclusions.

Recommendation 3

The original ICAI review found that survivors were not systematically included in PSVI’s work, and there were no processes in place to ensure consultation of survivors during project design, implementation or monitoring. There was no requirement to provide evidence to underpin the intervention and justify its design – in the form of a conflict analysis, survivor consultations or a ‘do no harm’ appraisal – nor an ethical protocol for survivor engagement. The one-year funding cycle was found to be an impediment to the meaningful participation of survivors and to heighten the risk of inadvertently doing harm. In order to avoid this, ICAI recommended that the UK government should ensure that its work on preventing conflict-related sexual violence is founded on survivor-led design, which has clear protocols in place founded in ‘do no harm’ principles.

Although it accepted the recommendation, FCDO noted that “PSVI has always been committed to ensuring a survivor-centred approach to tackling CRSV. Survivors are an integral part of PSVI policy and programming development and we uphold the Do No Harm principle, based on departmental guidance.” In its December 2020 update on progress, FCDO added that it continues to collaborate closely with PSVI Survivor Champions and had progressed two survivor-focused initiatives on the global stage during 2020:

- The UK has been a strong backer of the Murad Code, a global code of conduct to ensure that work with survivors of CRSV to investigate, document, and record their experiences is safer, more ethical and more effective.19 Importantly, the Murad Code is accompanied by a ‘Commentary to the Code’ consisting of resources, tools and guides, as well as shared learning and best practice. It is also guided by a Survivors’ Charter “prepared by survivors to express their wishes on how documenters should engage with them”.

- The second initiative is the Declaration of Humanity, launched by Minister of State Lord Ahmad in November 2020, alongside faith and belief leaders during the Annual Freedom of Religion or Belief Ministerial Conference in Poland. The Declaration, the first of its kind, calls for the prevention of sexual violence in conflict and denounces the stigma too often faced by survivors.

FCDO continues to be a central diplomatic actor in the work to keep a global focus on CRSV through high-level, high-visibility initiatives. This is an important role. However, as described in the original ICAI review, there is not an accompanying emphasis on programming for survivors. The PSVI team currently consists of four people. The PSVI budget remained very small in 2020, while the budget for 2021 is not yet confirmed. Some interviewees noted an increase in survivor focus and engagement in programming, but we were not able to verify this as ICAI did not get updates on programme activities beyond brief descriptions of projects and their aims. The one-year project cycle continues to be a hindrance to meaningful survivor engagement in programme design and delivery.

Recommendation 4

ICAI recommended that the UK government should build a systematic learning process into its programming to support the generation of evidence of ‘what works’ in addressing conflict-related sexual violence and ensure effective dissemination and uptake across its portfolio of activities, after finding that the PSVI had no learning strategy or learning systems in place. This meant that it did not have mechanisms to identify evidence gaps, invest in generating learning to fill these gaps, and apply learning to the design and delivery of new projects.

There have not been many concrete actions directly relevant to PSVI to address this recommendation. Throughout 2020, the VAWG evidence team supported evidence gathering around gender-based violence in emergencies, which was impactful, internationally recognised, and contributed to work globally in this area. But evidence was not generated on forms of sexual violence that are specific to conflict settings. This gap likely stems from the differences found in ICAI’s review between the priorities of DFID and the FCO, with the VAWG team focused mainly on gender-based violence more broadly – and particularly intimate partner violence – and less on the specific challenges of CRSV. It is not possible at this point to judge whether this gap between CRSV and VAWG will continue within the merged FCDO and it remains unclear where the centre for CRSV-related learning will sit.

Conclusion

There still seems to be a gap between the public expression by the UK government that PSVI is a priority20 and the level of funding and efforts expended on CRSV programming – particularly on funding operational programming, which is set to remain modest (although we do not yet know how CRSV programming will be affected by the large cuts to UK aid in 2021). The follow-up of ICAI’s recommendations for PSVI took place in the midst of major reorganisation and continued uncertainty about programming and funding decisions. The role of the MOD in any future PSVI efforts is unclear. The planned FCDO strategies, with ToCs, KPIs and MEL arrangements for Gender and Conflict, as well as for PSVI, have the potential to address many of ICAI’s concerns, but until these have been published, organisational restructuring has settled and funding decisions have been made, it is too early to conclude that the government’s response has been adequate. We will therefore return to this review as an outstanding issue next year.

Since we will also conduct the first follow-up of ICAI’s review of Sexual Exploitation and Abuse by International Peacekeepers21 next year, we will use that opportunity to engage with the MOD on its aid funded activities across the spectrum of tackling CRSV.

Second follow-up to ICAI’s review of CDC’s investments in low-income and fragile states

Progress summary